Abstract

Objectives:

To examine the concordance of coronary computed tomographic angiography (CCTA) assessment of coronary anatomy and invasive coronary angiography (ICA) as the reference standard in patients enrolled in the International Study of Comparative Health Effectiveness with Medical and Invasive Approaches (ISCHEMIA).

Background:

Performance of CCTA compared with ICA has not been assessed in patients with a very high burden of stress-induced ischemia and a high likelihood of anatomically significant CAD. A blinded CCTA was performed after enrollment to exclude patients with left main (LM) disease or no obstructive coronary artery disease (CAD) prior to randomization to an initial conservative or invasive strategy, the latter guided by ICA and optimal revascularization.

Methods:

Rates of concordance were calculated on a per-patient basis in patients randomized to the invasive strategy. Anatomical significance was defined as ≥ 50% diameter stenosis (DS) for both modalities. Sensitivity analyses using a threshold of ≥ 70% DS for CCTA or considering only CCTA images of good to excellent quality were performed.

Results:

In 1728 patients identified by CCTA as having no LM ≥ 50% and at least single vessel CAD, ICA confirmed 97.1% without LM ≥ 50%, 92.2% with at least single vessel CAD and no LM ≥ 50%, and only 4.9% without anatomically significant CAD. Results using a ≥ 70% DS threshold or only CCTA of good to excellent quality showed similar overall performance.

Conclusions:

CCTA prior to randomization in ISCHEMIA demonstrated high concordance with subsequent ICA for identification of patients with angiographically significant disease without LM.

Keywords: ischemia, cardiac computed tomographic angiography, invasive coronary angiography, cardiac catheterization, left main coronary artery disease

Introduction

The ISCHEMIA trial assessed whether patients with moderate or severe ischemia on functional testing would have improved outcome if treated with an initial invasive strategy that included optimal medical therapy (OMT) compared with OMT alone with cardiac catheterization reserved for failure of medical therapy (1,2). The protocol included a pre-randomization, blinded coronary computed tomographic angiogram (CCTA) in the majority of participants to address 3 issues. First, it was a pragmatic way to address safety and commensurately to facilitate physician willingness to randomize patients by excluding those with important left main (LM) disease. Secondly, CCTA helped avoid randomization of patients with no significant obstructive coronary artery disease (CAD) who would not benefit from revascularization and who would dilute statistical power of the trial. Finally, it overcame concerns that randomization at the time of invasive coronary angiography (ICA) might dissuade physicians from randomizing patients in the catheterization laboratory with knowledge of the presence of high anatomical burden of disease (2,3). The use of CCTA to address these issues was based upon the strong relationship between CCTA and ICA and the rapidly emerging role of CCTA as a tool to improve angiography suite utilization (4–13). The primary aim of this analysis was to identify the per-patient concordance between CCTA and ICA for identification of obstructive CAD and absence of LM disease. We also explored discordance for absence of significant LM and concordance for burden of disease as reflected by one-, two- or three-vessel disease, location of disease per major vessel and for assessment of proximal disease in the left anterior descending (LAD).

Methods

The study population consisted of the participants randomized to the invasive group who had a core-laboratory-interpreted, pre-randomization CCTA and a core-laboratory-interpreted baseline ICA within 6 months of CCTA. Exclusion criteria for this analysis were: 1) prior coronary artery bypass grafting, 2) non-interpretable CCTA or ICA, 3) ≥ 50% diameter stenosis (DS) LM on CCTA, 4) absence of ≥ 50% DS on CCTA for participants enrolled after a stress imaging test, 5) absence of ≥ 70% DS on CCTA for participants enrolled after a non-imaging exercise tolerance test, 6) greater than 6 months between pre-randomization CCTA and ICA, and 7) a post-randomization revascularization procedure prior to the date of the baseline diagnostic angiogram (See Figure 1, Supplementary Materials). A total of 1757 participants were available for analyses representing 67.9% of the total number randomized to the invasive arm (n = 2588) and 91.9% of the scans received by the core CCTA laboratory for participants randomized to the invasive strategy (n = 1913). There were 1728 patients with complete information to make overall patient level assessment for the primary per patient analysis and the remaining (n = 29) were suitable only for inclusion in various vessel and segment level analyses. There were 1296 patients with complete information for analysis of agreement between CCTA and ICA for the number of vessels diseased; a case was considered not evaluable for the number of vessels diseased if certain designated segments could not be interpreted for the presence of ≥ 50% DS, for example, the mid RCA, due to cardiac motion or other artifact.

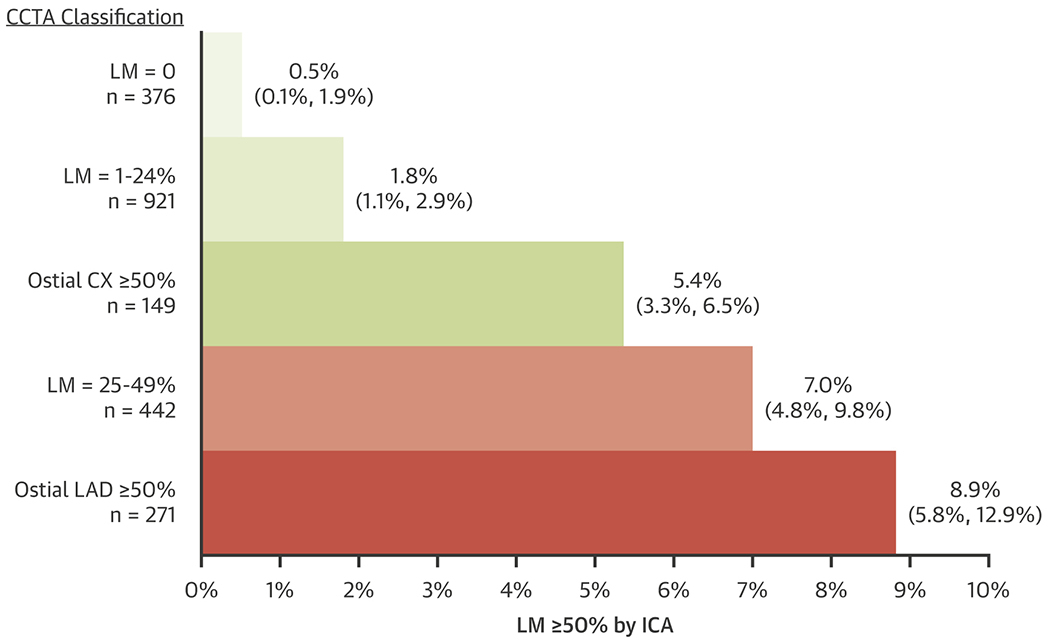

Figure 1: ICA detection of LM ≥ 50% DS as a function of CCTA Classification.

The CCTA classification of LM (0%, 1 – 24% and 25 – 49% DS) or the classification of ostial CX or ostial LAD is shown on the left with the number of individual reports. The length of the horizontal bars represents the percentage of cases (with 95% exact binomial confidence intervals) having LM ≥ 50% DS by ICA for each of the CCTA classifications. CCTA = cardiac computed tomographic angiography, CX = circumflex, DS = diameter stenosis, ICA = invasive coronary angiography, LAD = left anterior descending, LM = left main. Note that 18 CCTAs were not interpretable for the presence of LM ≥ 50% DS, leaving a sample size of 1739.

The primary analysis was based upon use of the ≥ 50% DS threshold in all suitable patients and applied to both ICA and CCTA. Secondary analyses (shown in the Supplementary Materials) used 1) only those participants enrolled after use of stress imaging to assess ischemic burden, and the ≥ 50% DS threshold (n = 1260, excluding those enrolled only after non-imaging exercise tolerance testing because randomization of such patients was based upon a ≥ 70% DS threshold on CCTA), 2) ≥ 70% DS threshold applied to all patients for both CCTA and ICA, and 3) a ≥ 70% DS threshold applied to CCTA compared with a ≥ 50% threshold applied to ICA. Finally, sensitivity analyses of the primary and secondary aims were performed using only good or excellent quality CCTA. CCTA image quality was recorded based on assessment of overall image noise, presence of motion artifacts, poor contrast, misregistration, adequacy of field of view, calcium affecting ease of segmental analysis or difficult to assess stents, among other factors. Each scan was also graded as either excellent, good, fair or poor. All CCTA segmental assessments were determined by consensus of at least two independent readers, and cases of LM disease were also reviewed and finalized by a third reader. Readers assessed 17 segments (14) with additional identification of whether lesions were in the ostium of the LAD or the circumflex (CX). The lesions were graded categorically as 0%, 1-24%, 25-49%, 50 – 69% and 70% or greater. Quantitative coronary angiography was performed as previously described (15). All patients provided informed consent for participation in the ISCHEMIA trial. The protocol was approved by the institutional review board at New York University Grossman School of Medicine (the clinical coordinating center) and by the institutional review board and ethics committee at each participating site (see the Supplementary Appendix).

Statistical analysis focused on estimating the probability that patients who were classified as having significant CAD and no significant LM on CCTA would be classified the same by ICA. We also examined the frequency of CCTA and ICA agreeing on the number of diseased vessels and the presence or absence of stenosis in specific vessels. The study’s main concordance measures were the percent of participants with CCTA-defined CAD ≥50% and no LM≥50% whose ICA result was concordant in the sense of having ICA-defined CAD ≥50% and no ICA LM≥50%, the percent who were discordant due to ICA CAD<50%, and the percent who were discordant due to ICA LM ≥50%. Rates of discordance due to ICA LM≥50% were estimated overall and across subgroups based on CCTA-defined number of diseased vessels and degree of stenosis in specific vessels. All concordance measures in this study were conditional on having CCTA-defined CAD≥ 50% and no LM≥ 50%. Patients who failed screening due to CCTA-defined LM ≥50% or no CAD ≥50% did not receive a study ICA in ISCHEMIA and were therefore excluded. Traditional accuracy measures treating ICA as the reference standard could not be calculated due to missing ICA results for the patients who failed screening. The exclusion of such patients prevented us from estimating sensitivity and specificity but did not invalidate estimation of concordance probabilities as defined above for patients meeting ISCHEMIA’s inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Results

The median (25th and 75th percentile) time between CCTA and ICA was 29 (18, 46) days with a mean and standard deviation of 35.7 ± 27.1 days.

A). Per Patient Analysis

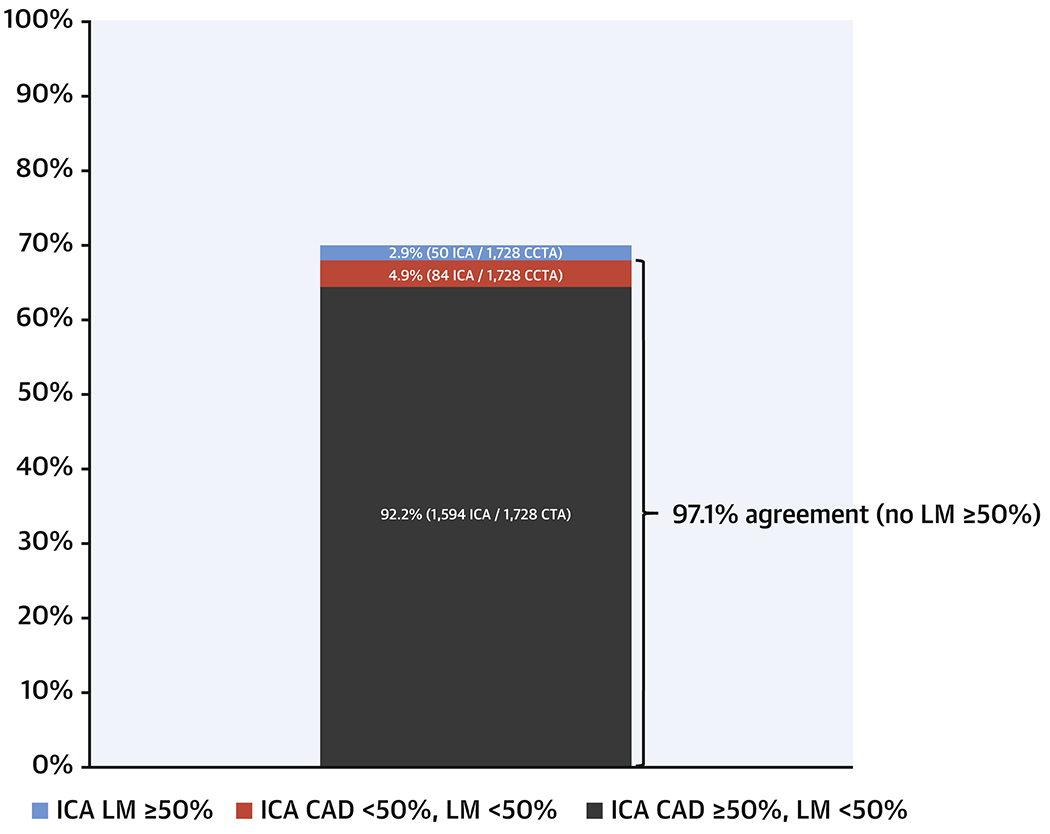

ICA and CCTA were concordant for the identification of at least single vessel CAD and absence of LM ≥ 50% in 92.2% of cases (95% Confidence Interval [CI]: 90.9%, 93.5%). In 4.9% (95% CI: 3.9%, 6.0%) of cases, ICA did not confirm presence of CAD ≥ 50% DS. And in 2.9% (95% CI: 2.2, 3.8%) of cases, CCTA missed ICA identified LM ≥ 50% DS (Central Illustration). Thus, ICA and CCTA were concordant in 97.1% (1678/1728) for the absence of significant LM ≥ 50%.

Central Illustration: Overall percent agreement between ICA and CCTA.

There was 97.1% concordance for the absence of LM disease and 92.2% concordance for the designation of at least single vessel coronary disease without LM. There were 50 cases of the 1728 patients in total (2.9%) who had ICA evidence of LM ≥ 50% DS despite a CCTA report of < 50% DS. CCTA = cardiac computed tomographic angiography, ICA = invasive coronary angiography, LM = left main. The 1728 denominator comes from 1757 patients eligible for the overall study minus 21 patients with non-evaluable CCTAs and 8 with missing ICA information for ≥ 50% CAD.

B). Assessment of LM Disease Discordance

When CCTA identified LM = 0% DS (376 patients), it was rare (2 patients, 0.5%) for ICA to report LM ≥ 50% DS. Of 921 patients with a CCTA finding of 1 – 24% DS, 1.8% (17 patients) had LM ≥ 50% DS on ICA. Of 442 patients with a CCTA report of LM 25 – 49% DS, 7% (31 patients) had LM ≥ 50% on ICA. The average %DS of the significant LM stenosis detected by ICA was 62 ± 3% (mean ± standard deviation), 62 ± 14% and 64 ± 10%, respectively for these 3 CCTA categories of LM assessment (0, 1-24%, 25-49%). When CCTA identified ≥ 50% DS in the ostial CX (149 patients) or ostial LAD (271 patients), but < 50% DS in the LM, there were 5.4% (8 patients) and 8.9% (24 patients) with ICA showing ≥ 50% DS in the LM, respectively (Figure 1). Examples of discrepancies in 3 patients are shown in Figure 2.

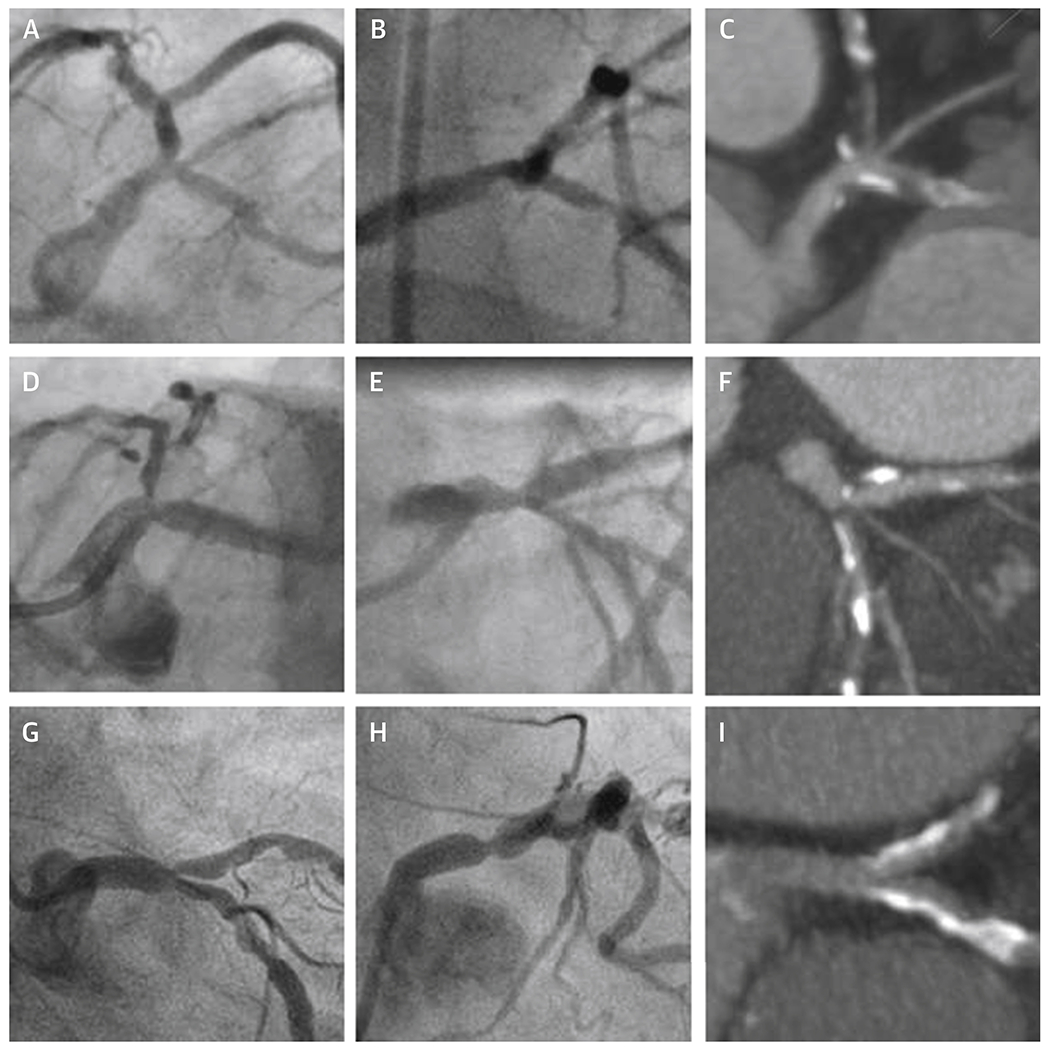

Figure 2: Left Main ICA and CCTA Discordance.

Each row represents one of three patients with ICA detection of LM ≥ 50% and CCTA report of LM < 50% DS. Panels A, B, D, E, G, and H are two ICA frames showing a potential stenosis in the LM ≥ 50% for each patient. A single, corresponding CCTA reconstruction for each patient is shown at the end of each row in panels C, F, and I. CCTA = cardiac computed tomographic angiography, CX = circumflex, DS = diameter stenosis, ICA = invasive coronary angiography, LAD = left anterior descending, LM = left main.

C). Assessment of Number of Diseased Vessel

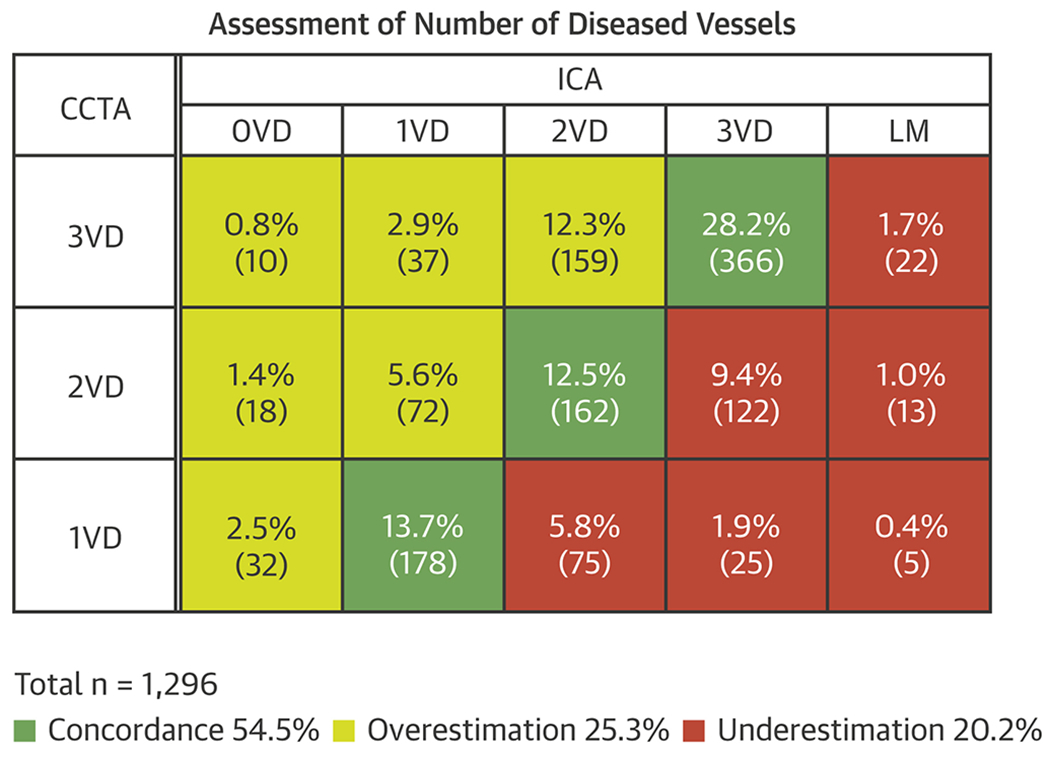

The agreement between CCTA and ICA for the designation of presence of single, double or triple vessel disease without LM was 54.5% (Figure 3). Overestimation of disease by CCTA occurred in 25.3% of cases and underestimation, including underestimation of LM disease, in 20.2% of cases.

Figure 3: Concordance matrix between CCTA and ICA for detection of single, double, or triple vessel disease.

Shading in green identifies concordance between the two imaging methods. Shading in red identifies underestimation and, in yellow, overestimation. Designation of LM < 50% by CCTA but ≥ 50% by ICA was considered an underestimation by CCTA. The n per cell is provided and expressed as a percent of the total n = 1296. The overall concordance was 54.5% (95% confidence interval: 51.7% - 57.2%). CCTA = cardiac computed tomographic angiography, ICA = invasive coronary angiography, LM = left main. Note that in 426 CCTAs and 35 ICAs, certain designated segments could not be interpreted for the presence of ≥ 50% DS leaving a sample size of 1296 for which the number of diseased vessels is known.

D). Assessment of Location of Disease

a. Per Vessel Analysis

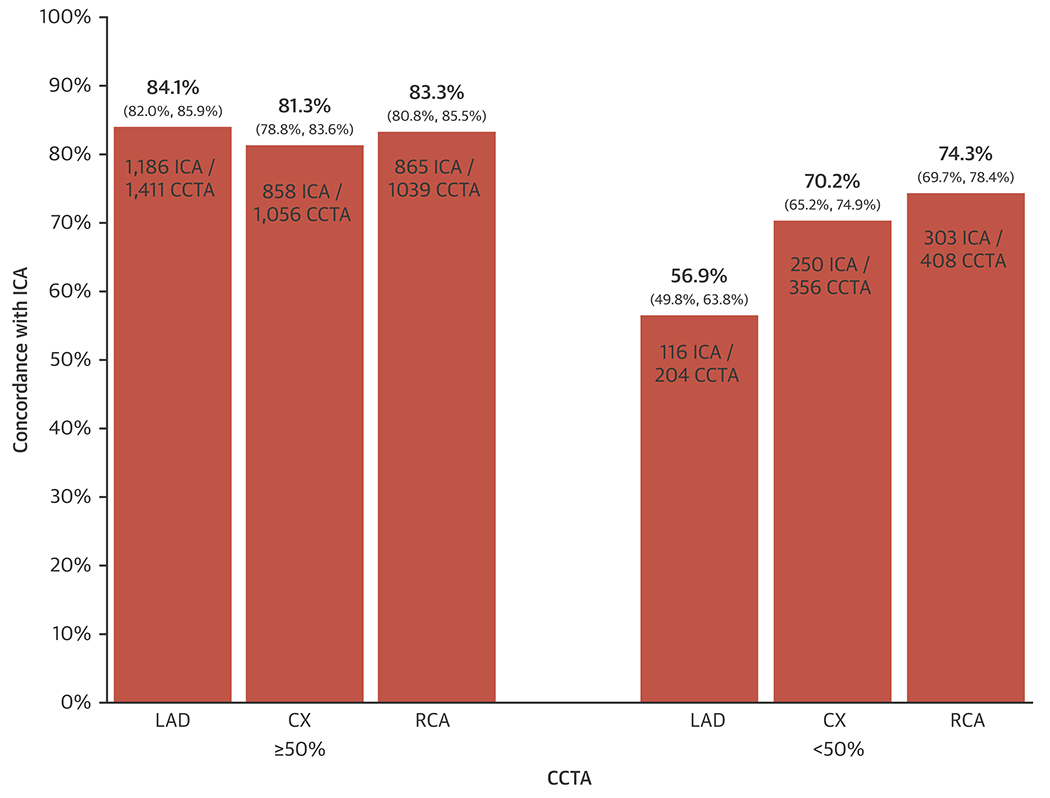

Figure 4 demonstrates concordance between ICA and CCTA for the presence of ≥ 50% DS in the LAD, CX and right coronary artery (RCA) (including their major branches, see “Definitions” in Supplementary Materials) of 84.1%, 81.3% and 83.3% of patients respectively. Conversely, concordance for < 50% DS was 56.9%, 70.2%, and 74.3%, respectively.

Figure 4: Concordance between CCTA and ICA for location of significant CAD in major vessels.

The x-axis shows CCTA reports of disease ≥ 50% and < 50% DS in the LAD, the CX or the RCA. The y-axis shows the percent concordance with ICA as derived from the numbers shown within the bars (numerator = cases that agree with ICA, denominator = number of cases with the CCTA result shown). 95% confidence intervals are provided in brackets. CAD = coronary artery disease, CCTA = cardiac computed tomographic angiography, CX = circumflex, DS = diameter stenosis, ICA = invasive coronary angiography, LAD = left anterior descending, RCA = right coronary artery.

b. Assessment of LAD Segments

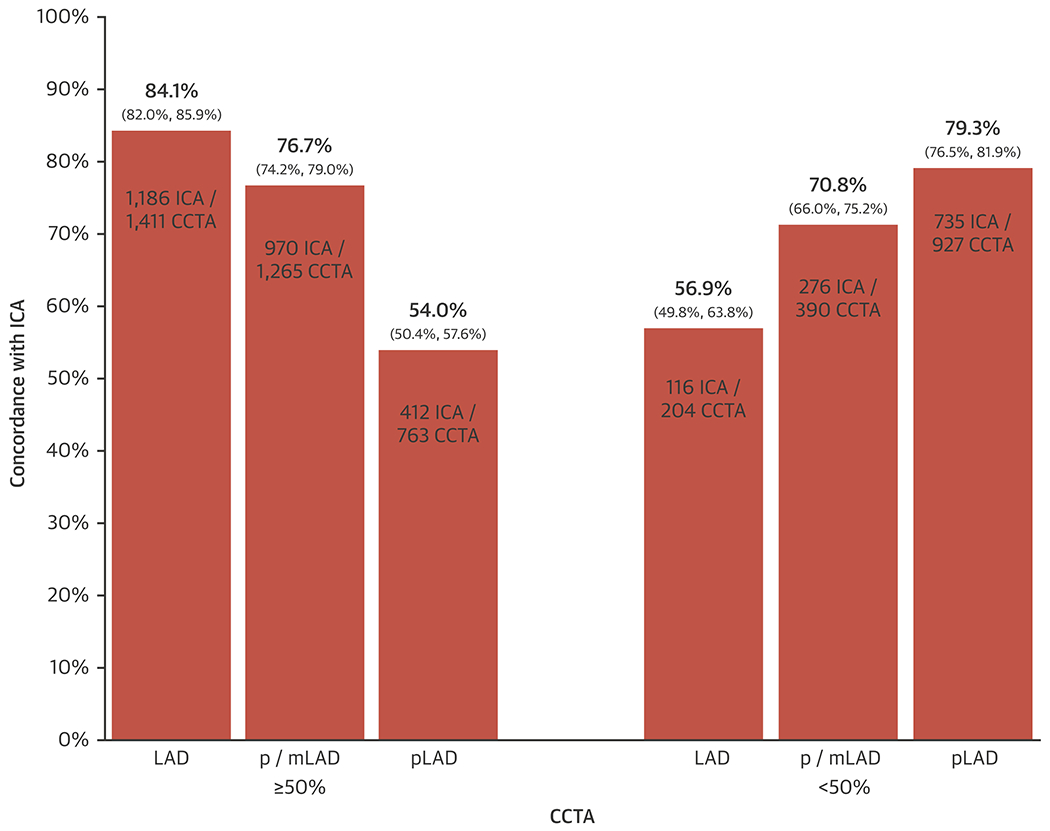

Because of the importance attached to LAD disease, and due to variable visual cues for segmentation between ICA and CCTA (e.g. septals are infrequently used to define proximal LAD on CCTA whereas this is more feasible with ICA), we analyzed concordance between CCTA and ICA for the LAD as a whole, for an “extended” proximal LAD or mid LAD segment and for the isolated proximal LAD (Figure 6). This shows an expected decrease in concordance for presence of significant stenosis as one progresses from considering the entire LAD vessel (84.1%), the proximal or mid LAD (76.7%) and only the proximal LAD itself (54.0%). Conversely, exclusion of significant disease improved progressively from LAD vessel overall (56.9%) to the proximal or mid LAD (70.8%) and the proximal LAD itself (79.3%).

E). Sensitivity Analyses

Other secondary and sensitivity analyses for the main, per patient results are provided in the Supplementary Materials and showed similar results. In particular, use of a ≥ 70% DS threshold applied to CCTA and a ≥ 50% DS threshold applied to ICA did not improve per patient performance. Additionally, a focus on the subset (n = 830/1757, 47%) with CCTA quality rated as good or excellent did not change performance (Supplementary Tables 5 and 6).

Discussion

In this cohort with a very high a priori likelihood of obstructive CAD, CCTA was highly concordant with ICA in patients randomized to the invasive arm of the ISCHEMIA trial (97.1% for excluding LM ≥ 50% and 92.2% for identifying patients with at least 1 vessel CAD and no LM). Concordance for burden of disease based on numbers of diseased vessels (1, 2 or 3 and without LM) was modest (54.5%). Overestimation of disease burden by CCTA occurred in 1 in 4 and underestimation in 1 in 5 cases as compared with ICA. Thus, CCTA successfully ensured that randomization of patients with non-invasive evidence of moderate to severe ischemia would be limited as much as possible to those without LM disease and avoided as much as possible those patients without significant CAD. It also enabled avoidance of the pitfalls of study enrolment at the time of ICA when biases might have compromised randomization to OMT of patients with a higher burden of disease and disease in locations such as the ostial or proximal LAD.

The analysis of LM in this report is limited by necessity, first to only those patients felt to be eligible for randomization after excluding LM through use of CCTA and secondly, to those randomized to the invasive strategy. It has already been reported that of the 5757 patients undergoing a study CCTA, 434 were not eligible for randomization based upon a CCTA core laboratory report of LM ≥ 50% (7.5% of subjects) (16). But ICA core laboratory corroboration is not available in those patients. It is conceivable that the percentage of patients having ICA confirmed LM disease might be less than 7.5%, based on the potential for overestimation by CCTA and the imperative for CCTA readers to maximize patient safety, possibly leading to “overcalling” of LM disease. But of those who proceeded to ICA, detailed analysis of the small number of discordant cases allowed us to identify some CCTA findings associated with a higher likelihood of finding LM ≥ 50% DS on ICA, most notably CCTA reporting of ostial LAD or CX DS ≥ 50% and/or LM 25-49% DS. One may argue that ICA, a 2-dimensional imaging modality may not be an appropriate gold standard for determining the precise difference between a distal LM stenosis and an ostial LAD or ostial CX stenosis compared to CCTA (17). The sample images in Figure 2 may be taken to support this hypothesis. Regardless, exclusion of LM by CCTA in 97.1% of cases proceeding to ICA was excellent.

Although concordance between CCTA and ICA for identifying severe disease in specific major vessels (LAD vs CX vs RCA) was high (81.3 to 84.1%), excluding disease in each specific vessel was only modest (56.9% to 74.3%) (Figure 4). Such analyses are affected by the binary categorization based upon the 50% threshold. We did not see material differences with secondary analyses using only good/excellent scans or using a higher stenosis threshold (≥ 70%).

Our findings are in line with the findings of the recent SYNTAX II trial where participants underwent CCTA and ICA with SYNTAX scores calculated from both modalities (18). The SYNTAX scores from CCTA overestimated the disease burden compared to the invasive gold standard. Thus, CCTA is a good tool to help enrich the population referred for ICA compared to stress testing alone but should not be considered adequate for precise planning of any specific revascularization strategy without ICA corroboration. Others have also highlighted these types of discrepancies (19–22).

Elements of this study may limit the application to routine clinical CCTA or to more broad populations, particularly those with much lower a priori likelihood of CAD. The analyses were based upon core-laboratory assessment and were all determined by consensus (23). This element of quality control does not occur in routine practice. The analyses are based solely on those patients eligible by CCTA and subsequently undergoing core laboratory analysis of ICA. We do not have ICA comparisons for those patients deemed by CCTA to have either no significant CAD or LM ≥ 50% DS, thereby precluding valid calculations of sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values. The highly selected cohort had a very high probability of significant underlying CAD based on selection by prior evidence of moderate or severe stress-induced ischemia and a history of angina in 89%. This feature, however, is also a unique strength of the analyses because the majority of prior studies comparing the performance of CCTA with ICA have been undertaken in populations with a much lower risk and extent of underlying CAD, accounting for the well-known, high negative predictive value of CCTA (4–10). It is worth emphasizing that calcium remains an impediment to the facile reading of CCTA scans and calcium sufficient to potentially impair segmental analysis was present in 31% of scans (Supplementary Table 5) (24,25). Accordingly, only 75% of CCTA studies could be included in the analysis of number of vessels diseased, because key segments were not evaluable for ≥ 50% DS in the remaining 25% due to calcification, motion or other artifacts. Stents (noted in 17% of patients in this study) provide similar challenges to CCTA reading. All reading of calcified or stented segments was performed using the principle of “best effort,” utilization of appropriate views, reconstructions, filters, windows and levels by the individual readers and then re-affirmed by the consensus process. Although exact concordance for segments within major vessels was suboptimal, this segmentation problem is recognized from studies attempting to correlate lesion-specific fractional flow reserve measured invasively with values derived from CCTA (26). Finally, CCTA-derived fractional flow reserve was not calculated so correlation with fractional flow reserve performed in some patients at the time of ICA was not possible.

The utility of CCTA in this research protocol of high-risk patients may have important implications for clinical practice and for expanding appropriate use criteria for CCTA in patients with moderate or severe ischemia, despite the limitations noted above (27). It has been shown in the CONSERVE trial that use of CCTA in patients with a lower probability of CAD compared to the ISCHEMIA trial helps to avoid unnecessary ICA, diminish ICA costs and improve overall utilization (28). After stress testing and prior to randomization, 21% of subjects undergoing CCTA were excluded because of the absence of significant CAD (16). Thus, the total experience of using CCTA in this trial and the unique, high-risk cohort suggests that an expanded role for CCTA prior to ICA may be warranted even when the ischemic burden is moderate or severe (11).

In conclusion, we demonstrated that in patients first shown to have moderate or severe ischemia on stress testing, CCTA was an effective method to identify patients with significant CAD and without LM disease as determined by ICA.

Supplementary Material

Figure 5: Assessment of LAD segments.

The x-axis shows CCTA reports of disease ≥ 50% and < 50% DS in the entire LAD vessel, in an extended segment consisting of both the proximal (p) and mid (m) LAD, and solely in the pLAD. The y-axis shows the concordance with ICA in percent as derived from the numbers shown within the bars (numerator = cases that agree with ICA, denominator = number of cases with the CCTA result shown). 95% confidence intervals are provided in brackets. CCTA = cardiac computed tomographic angiography, DS = diameter stenosis, ICA = invasive coronary angiography, LAD = left anterior descending, m = mid; p = proximal.

Clinical Perspectives:

Cardiac computed tomographic angiography was utilized in a novel fashion to determine coronary anatomy eligibility for a randomized trial that compared a conservative strategy with an invasive strategy for the management of patients with chronic coronary artery disease. Patients had a very high, a priori likelihood of underlying coronary disease by virtue of moderate or severe ischemia documented by stress testing. Subsequent evaluation by cardiac computed tomographic angiography prior to invasive angiography served well to ensure presence of angiographically significant CAD, and to exclude left main disease and non-obstructive disease.

Competency in Patient Care:

This analysis demonstrates that patients suspected of coronary artery disease with stress tests showing moderate or severe ischemia can be effectively stratified further using cardiac computed tomography to assess left main stenosis and to ensure that when intervention may be warranted, procession to invasive angiography is reserved for patients with verified anatomical burden of disease.

Translational Outlook:

The results of this study potentially expand the appropriate use of computed tomographic angiography prior to referral to invasive angiography when there is evidence of moderate or severe ischemia. This sequence more precisely identifies patients who truly have anatomically significant underlying coronary atheroma when intervention is being considered.

Acknowledgments

Funding: NIH grants U01HL105907, U01HL105462, U01HL105561

Disclosure Statements

Dr. G. B. John Mancini reports grant from National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute during the conduct of the study.

Dr. Jonathan Leipsic reports Consultant and Stock Options HeartFlow and CIRCLE CVI; Research Grant GE Healthcare outside the submitted work.

Dr. Matthew Budoff reports grant support from General Electric outside the submitted work.

Dr. Cameron Hague reports grants from National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute during the conduct of the study.

Dr. James Min reports grants from National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, during the conduct of the study; other from CLEERLY INC., grants and other from GE HEALTHCARE, other from ARINETA, outside the submitted work.

Susanna Stevens reports grants from National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute during the conduct of the study.

Dr. Harmony Reynolds reports grants from National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute during the conduct of the study; non-financial support from Abbott Vascular, non-financial support from Siemens, non-financial support from BioTelemetry, outside the submitted work

Dr. Sean O’Brien reports grants from National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, during the conduct of the study.

Dr. Leslee Shaw reports grants from National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute during the conduct of the study.

Dr. Cholenahally Manjunath reports grants from National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute during the conduct of the study.

Dr. Kreton Mavromatis reports grants from National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute during the conduct of the study.

Dr. Marcin Demkow reports grants from National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute during the conduct of the study.

Dr. Jose Luis Lopez-Sendon reports grants from National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute during the conduct of the study.

Dr. Alexander Chernyavskiy reports grants from National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute during the conduct of the study.

Dr. Gilbert Gosselin reports grants from National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute during the conduct of the study.

Dr. Herwig Schuelenz reports grants from National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute during the conduct of the study.

Dr. Gerard Devlin reports grants from National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute during the conduct of the study.

Dr. Anoop Chauhan reports grants from National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute during the conduct of the study.

Dr. Sripal Bangalore reports grants from National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute and Advisory board- Abbott Vascular, Pfizer, Amgen, Biotronik, Meril and Reata.Abbott Vascular.

Dr. Judith Hochman reports being Principal Investigator for the International Study of Comparative Health Effectiveness with Medical and Invasive Approaches (ISCHEMIA) trial for which, in addition to support by a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grant, devices and medications were provided by Abbott Vascular, Medtronic, Inc, St Jude Medical Inc, Volcano Corporation, Arbor Pharmaceuticals LLC, AstraZeneca, Merck Sharp and Dohme Corp, Omron Healthcare Inc, and financial donations from Arbor Pharmaceuticals LLC and AstraZeneca outside the submitted work.

Dr. David Maron reports grants from National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute during the conduct of the study.

Abbreviations List:

- CAD

coronary artery disease

- CCTA

cardiac computed tomographic angiography

- CX

circumflex

- DS

diameter stenosis

- ICA

invasive coronary angiography

- LAD

left anterior descending

- LM

left main

- RCA

right coronary artery

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Maron DJ, Hochman JS, Reynolds HR et al. Initial Invasive or Conservative Strategy for Stable Coronary Disease. N Engl J Med 2020;382:1395–1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maron DJ, Hochman JS, O’Brien SM et al. International Study of Comparative Health Effectiveness with Medical and Invasive Approaches (ISCHEMIA) trial: Rationale and design. Am Heart J 2018;201:124–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maron DJ, Stone GW, Berman DS et al. Is cardiac catheterization necessary before initial management of patients with stable ischemic heart disease? Results from a Web-based survey of cardiologists. Am Heart J 2011;162:1034–1043.e13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Budoff MJ, Dowe D, Jollis JG et al. Diagnostic performance of 64-multidetector row coronary computed tomographic angiography for evaluation of coronary artery stenosis in individuals without known coronary artery disease: results from the prospective multicenter ACCURACY (Assessment by Coronary Computed Tomographic Angiography of Individuals Undergoing Invasive Coronary Angiography) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;52:1724–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meijboom WB, Meijs MFL, Schuijf JD et al. Diagnostic Accuracy of 64-Slice Computed Tomography Coronary Angiography: A Prospective, Multicenter, Multivendor Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;52:2135–2144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller JM, Rochitte CE, Dewey M et al. Diagnostic performance of coronary angiography by 64-row CT. N Engl J Med 2008;359:2324–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Graaf FR, Schuijf JD, van Velzen JE et al. Diagnostic accuracy of 320-row multidetector computed tomography coronary angiography in the non-invasive evaluation of significant coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J 2010;31:1908–1915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abdulla J, Abildstrom SZ, Gotzsche O, Christensen E, Kober L, Torp-Pedersen C. 64-multislice detector computed tomography coronary angiography as potential alternative to conventional coronary angiography: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Heart J 2007;28:3042–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ollendorf DA, Kuba M, Pearson SD. The diagnostic performance of multi-slice coronary computed tomographic angiography: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med 2011;26:307–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paech DC, Weston AR. A systematic review of the clinical effectiveness of 64-slice or higher computed tomography angiography as an alternative to invasive coronary angiography in the investigation of suspected coronary artery disease. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2011;11:32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taylor AJ, Cerqueira M, Hodgson JM et al. ACCF/SCCT/ACR/AHA/ASE/ASNC/NASCI/SCAI/SCMR 2010 appropriate use criteria for cardiac computed tomography. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force, the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, the American College of Radiology, the American Heart Association, the American Society of Echocardiography, the American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, the North American Society for Cardiovascular Imaging, the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;56:1864–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Chest pain of recent onset: assessment and diagnosis of recent onset chest pain or discomfort of suspected cardiac origin (update). CG95. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moss AJ, Williams MC, Newby DE, Nicol ED. The Updated NICE Guidelines: Cardiac CT as the First-Line Test for Coronary Artery Disease. Curr Cardiovasc Imaging Rep 2017;10:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leipsic J, Abbara S, Achenbach S et al. SCCT guidelines for the interpretation and reporting of coronary CT angiography: a report of the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography Guidelines Committee. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 2014;8:342–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chuang ML, Almonacid A, Popma JJ. Qualitative and quantitative coronary angiography. In: Topol EJ, Teirstein PS, editors. Textbook of Interventional Cardiology. 8th Edition ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2020:999–1017. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hochman JS, Reynolds HR, Bangalore S et al. Baseline Characteristics and Risk Profiles of Participants in the ISCHEMIA Randomized Clinical TrialBaseline Characteristics of Participants in the ISCHEMIA StudyBaseline Characteristics of Participants in the ISCHEMIA Study. JAMA Cardiology 2019;4:273–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kočka V, Theriault-Lauzier P, Xiong T-Y et al. Optimal Fluoroscopic Projections of Coronary Ostia and Bifurcations Defined by Computed Tomography Coronary Angiography. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2020. Online ahead of print [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Collet C, Miyazaki Y, Ryan N et al. Fractional Flow Reserve Derived From Computed Tomographic Angiography in Patients With Multivessel CAD. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;71:2756–2769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arbab-Zadeh A, Miller JM, Rochitte CE et al. Diagnostic Accuracy of Computed Tomography Coronary Angiography According to Pre-Test Probability of Coronary Artery Disease and Severity of Coronary Arterial Calcification: The CORE-64 (Coronary Artery Evaluation Using 64-Row Multidetector Computed Tomography Angiography) International Multicenter Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;59:379–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kerl JM, Schoepf UJ, Bauer RW et al. 64-slice multidetector-row computed tomography in the diagnosis of coronary artery disease: interobserver agreement among radiologists with varied levels of experience on a per-patient and per-segment basis. J Thorac Imaging 2012;27:29–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Song YB, Arbab-Zadeh A, Matheson MB et al. Contemporary Discrepancies of Stenosis Assessment by Computed Tomography and Invasive Coronary Angiography. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2019;12:e007720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Knaapen PMDP. Computed Tomography to Replace Invasive Coronary Angiography?: Close, but Not Close Enough. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2019;12:e008710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.LaBounty TM, Leipsic J, Srichai MB et al. What is the optimal number of readers needed to achieve high diagnostic accuracy in coronary computed tomographic angiography? A comparison of alternate reader combinations. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 2010;4:384–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qi L, Tang LJ, Xu Y et al. The Diagnostic Performance of Coronary CT Angiography for the Assessment of Coronary Stenosis in Calcified Plaque. PLoS One 2016;11:e0154852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muzzarelli S, Suerder D, Murzilli R et al. Predictors of disagreement between prospectively ECG-triggered dual-source coronary computed tomography angiography and conventional coronary angiography. Eur J Radiol 2016;85:1138–1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Min JK, Leipsic J, Pencina MJ et al. Diagnostic Accuracy of Fractional Flow Reserve From Anatomic CT Angiography. JAMA 2012;308:1237–1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meinel FG, Schoepf UJ, Townsend JC et al. Diagnostic yield and accuracy of coronary CT angiography after abnormal nuclear myocardial perfusion imaging. Sci Rep 2018;8:9228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chang HJ, Lin FY, Gebow D et al. Selective Referral Using CCTA Versus Direct Referral for Individuals Referred to Invasive Coronary Angiography for Suspected CAD: A Randomized, Controlled, Open-Label Trial. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2019;12:1303–1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.