Abstract

Background

Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) is an inflammatory disease with severe outcomes. Hepatocyte death, including apoptosis, necrosis, and pyroptosis, has been implicated in pathophysiology of NASH. Pyroptosis is mediated by inflammasome activation pathways including caspase-1–mediated canonical signaling pathway and caspase-11–mediated noncanonical signaling pathway. Until now, the precise role of caspase-11 in NASH remains unknown. In the present study, the potential roles of caspase-11 in NASH were explored.

Methods

We established methionine- and choline-deficient diet (MCD)–induced NASH mice model using wild-type caspase-11–deficient mice. The expression of caspase-11, liver injury, fibrosis, inflammation, and activation of gasdermin D and interleukin-1β were evaluated.

Results

Upregulated caspase-11 was detected in liver of mice with NASH. MCD-treated caspase-11–deficient mice had significantly decreased liver injury, fibrosis, and inflammation. The activation of gasdermin D and interleukin-1β was inhibited in caspase-11–deficient mice after MCD treatment. Overexpression of caspase-11 promoted steatohepatitis.

Conclusions

Caspase-11–mediated hepatocytic pyroptosis promotes the progression of NASH.

Key Words: Caspase-11, Pyroptosis, Liver, Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis

Abbreviations used in this paper: α-SMA, α smooth muscle actin; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; GSDMD, gasdermin D; GSDMD-N, N-terminal fragment of gasdermin D; IL, interleukin; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; MCD, methionine- and choline-deficient diet; mRNA, messenger RNA; NAFLD, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; NASH, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis; NF-κB, nuclear factor κB; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; TGF-β, transforming growth factor β; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor α

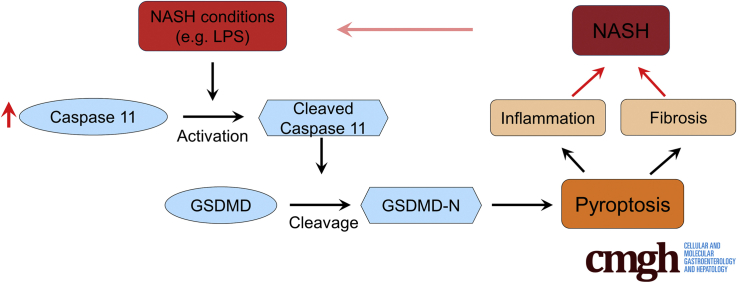

Graphical abstract

Summary.

Methionine- and choline-deficient diet–induced nonalcoholic steatohepatitis mice models using wild-type caspase-11–deficient mice were established. Caspase-11–mediated hepatocytic pyroptosis promotes the progression of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis.

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is chronic liver disease affecting around 25% population world widely.1 The spectrum of NAFLD includes isolated steatosis and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). NASH is the inflammatory form of NAFLD and is characterized based on histologic evidence not only of fat accumulation (steatosis) in hepatocytes, but also of liver-cell damage and infiltration of inflammatory cells.2 Compared with isolated steatosis, NASH could lead to progressive liver fibrosis and cirrhosis and finally result in liver-related illness and death.3,4 Despite its importance, NASH is under recognized in clinical practice, and there is no NASH-specific therapy approved. Therefore, understanding the mechanisms of NASH pathophysiology is critical to identify effective approach to treat NASH.

In patients and in experimental models of NASH, increased cell death is found in fatty liver. Both apoptosis and necrosis are key drivers of NASH. Recent study reveals that the crucial role of pyroptosis in NASH.5 Pyroptosis is a kind of inflammatory cell death induced by the activation of inflammasome.6 Inflammasome activates the caspase-1 and results in pore formation in cell plasma membrane, cell swelling, and massive release of proinflammatory cellular components.7 Gasdermin D (GSDMD) is a downstream effector of inflammasome that plays a specific role in pyroptosis. Active caspase-1 cleaves the GSDMD into N and C fragments. The cleaved N-terminal fragment of GSDMD (GSDMD-N) oligomerizes and forms pores on the cell membrane, which facilitates the IL-1β release.8 Increased GSDMD-N is detected in liver tissue of NASH patients and GSDMD-N is positively correlated with fibrosis. In a methionine- and choline-deficient diet (MCD)–induced steatohepatitis model, Gsdmd–/– mice have lower steatosis, indicating the essential role of GSDMD in NASH.9 Besides the caspase-1–induced canonical inflammatory pathway, the caspase-11–induced noncanonical pathway has been suggested to cleave GSDMD and regulate pyroptosis.10 Caspase-11 has been implicated in several diseases such as acute kidney injury.11 However, the precise roles of caspase-11 in NASH are not well studied. In present study, we established MCD-induced NASH mice model and evaluated the effects of caspase-11 on NASH.

Results

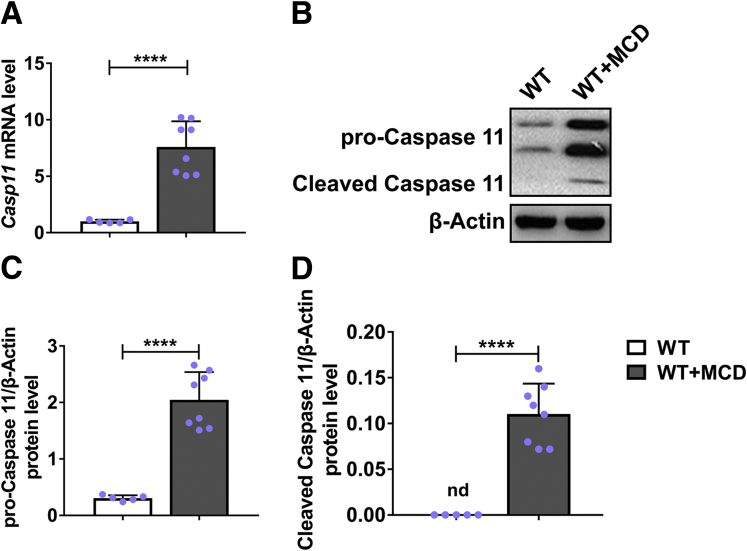

Caspase-11 Was Upregulated and Activated in Liver of Mice With Hepatic Steatosis

To explore the effects of caspase-11 in hepatic steatosis, first we detected the expression of caspase-11 in the liver of mice with hepatic steatosis. As shown in Figure 1A, significantly increased messenger RNA (mRNA) of caspase-11 was detected in liver of mice with MCD-induced hepatic steatosis when compared with liver of normal mice. Correspondingly, the protein levels of both pro-caspase-11 (Figure 1B and C) and cleaved caspase-11 (Figure 1B and D) were significantly upregulated in liver of mice with MCD-induced hepatic steatosis. These results suggested a positive correlation between caspase-11 and hepatic steatosis.

Figure 1.

Caspase-11 was upregulated and activated in liver during MCD-induced hepatic steatosis. Wild-type (WT) mice were treated with MCD for 8 weeks to induce NASH. Caspase-11 expression was determined by (A) reverse-transcription quantitative PCR and (B–D) Western blot, respectively. n = 5 for control group, n = 8 for MCD group. ∗∗∗∗P < .0001.

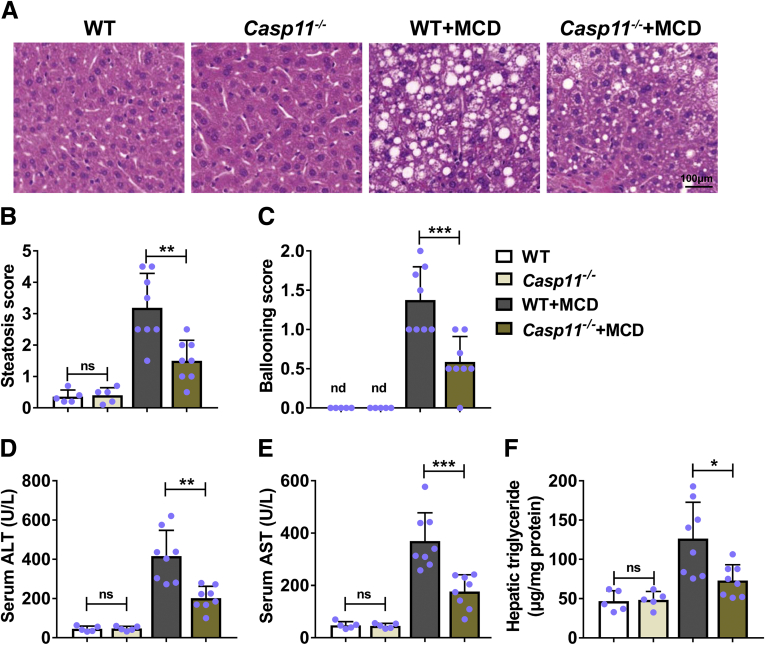

Deficiency of Caspase-11–Attenuated MCD-Induced Hepatic Steatosis in Mice

To evaluate the potential effects of caspase-11 on hepatic steatosis, we induced hepatic steatosis in caspase-11–deficient mice and monitored phenotypes. Normal wild-type and caspase-11–deficient mice had normal histologic appearance of liver. In contrast, wild-type mice treated with MCD had obvious steatosis and ballooning in liver. Compared with MCD-treated wild-type mice, MCD-treated caspase-11–deficient mice had obviously less steatosis and ballooning (Figure 2A). Correspondingly, MCD-treated caspase-11–deficient mice had significantly decreased liver steatosis score (Figure 2B) and ballooning score (Figure 2C) when compared with MCD-treated wild-type mice. We further found that compared with MCD-treated wild-type mice, MCD-treated caspase-11–deficient mice had significantly decreased level of serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) (Figure 2D), serum aspartate aminotransferase (AST) (Figure 2E), and hepatic triglycerides (Figure 2F), 3 biomarkers of liver disease. Our results demonstrated that caspase-11–deficient mice had less liver disease after MCD treatment, indicating that caspase-11 deficiency attenuated MCD-induced hepatic steatosis in mice.

Figure 2.

Deficiency of caspase-11–attenuated MCD-induced hepatic steatosis in mice. Casp11+/+ (WT) or Casp 11–/– mice were treated with MCD for 8 weeks to induce NASH. Paraffin-embedded liver sections were stained with (A) hematoxylin and eosin, and (B) hepatic steatosis and (C) ballooning scores were calculated. (D) Serum ALT level, (E) serum AST level, and (F) liver triglycerides were detected. n = 5 for 2 control groups, n = 8 for 2 MCD groups. ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001.

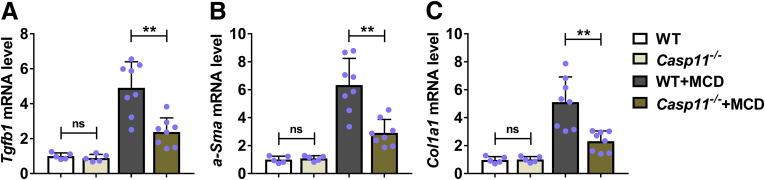

Deficiency of Caspase-11–Attenuated Hepatic Fibrosis in Mice With NASH

We continued to evaluate the effects of caspase-11 deficiency in MCD-induced hepatic fibrosis by measuring the expression of fibrosis-related factors including transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) (encoded by Tgfb1), α smooth muscle actin (encoded by α-Sma) and alpha-1 type I collagen (encoded by Col1a1). Under normal condition, wild-type and caspase-11–deficient mice had similar expression of Tgfb (Figure 3A), α-Sma (Figure 3B), and Col1a1 (Figure 3C). MCD-treated wild-type mice had significantly upregulated expression of Tgfb, α-Sma, and Col1a1. In contrast, MCD-treated caspase-11–deficient mice had significantly decreased mRNA levels of Tgfb (Figure 3A), α-Sma (Figure 3B), and Col1a1 (Figure 3C). These results demonstrated that caspase-11 deficiency resulted in reduced hepatic fibrosis in MCD-treated mice.

Figure 3.

Deficiency of caspase-11–attenuated MCD-induced hepatic fibrosis in mice.Casp11+/+ (WT) or Casp 11–/– mice were treated with MCD for 8 weeks to induce NASH. The mRNA level of (A) Tgfb1, (B) α-Sma, and (C) Col1a1 was determined by reverse-transcription quantitative PCR. n = 5 for 2 control groups, n = 8 for 2 MCD groups. ∗∗P < .01.

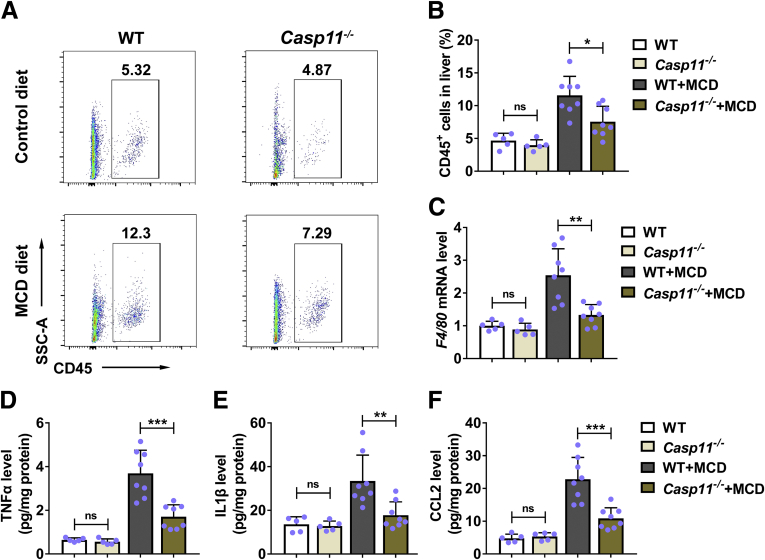

Deficiency of Caspase-11–Inhibited MCD-Induced Inflammation in Liver

Next, we evaluated the effects of caspase-11 deficiency on MCD-induced inflammation. First, we compared the leukocyte infiltration in liver between wild-type and caspase-11–deficient mice. Under normal condition, wild-type mice and caspase-11–deficient mice had similar percentage of CD45+ cells in liver (Figure 4A and B). MCD treatment resulted in increased percentage of CD45+ cells in liver of wild-type mice. In contrast, MCD treatment only slightly increased the percentage of CD45+ cells in liver of caspase-11–deficient mice. When compared with MCD-treated wild-type mice, MCD-treated caspase-11–deficient mice had significantly decreased percentage of CD45+ cells in liver (Figure 4A and B), indicating that deficiency of caspase-11 resulted in less leukocyte infiltration in liver after MCD treatment. Correspondingly, we found MCD treatment promoted the expression of F4/80 in liver, while caspase-11 deficiency suppressed MCD-induced upregulation of F4/80 (Figure 4C). We further identified that MCD treatment induced the expression of tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) (Figure 4D), interleukin (IL)-1β (Figure 4E), and CCL2 (Figure 4F) in liver of wild-type mice. In contrast, MCD-treated caspase-11–deficient mice had significantly decreased protein levels of TNF-α (Figure 4D), IL-1β (Figure 4E), and CCL2 (Figure 4F) in liver when compared with MCD-treated wild-type mice. These results demonstrated that MCD-treated caspase-11–deficient mice had less leukocytes infiltration and inflammatory cytokine production in liver, suggesting caspase-11 deficiency suppressed MCD-induced inflammation in liver.

Figure 4.

Deletion of caspase-11–inhibited MCD-induced inflammation in liver.Casp11+/+ (WT) or Casp 11–/– mice were treated with MCD for 8 weeks to induce NASH. (A, B) The infiltration of immune cells (CD45+) in liver was determined by fluorescence-activated cell sorting, and (C) the mRNA level of F4/80 was determined by reverse-transcription quantitative PCR. And the protein level of (D) TNF-α, (E) IL-1β, and (F) CCL2 was detected by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. n = 5 for 2 control groups, n = 8 for 2 MCD groups. ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. ns, no significance.

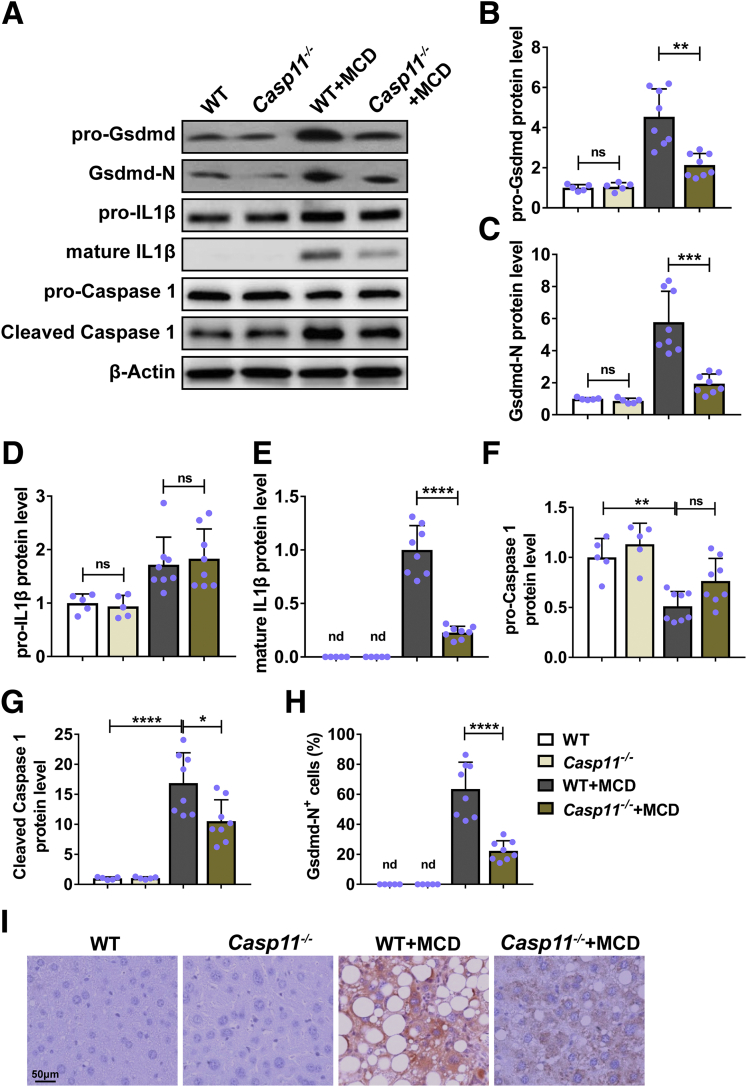

Deficiency of Caspase-11–Inhibited Hepatocytic Pyroptosis in Mice With NASH

Next, we evaluated the effects of caspase-11 deficiency on activation of pyroptosis after MCD treatment in mice. We measured the activation of Gsdmd and IL-1β, 2 key factors in pyroptosis.12 We detected similar protein levels of pro-Gsdmd (Figure 5A and B), Gsdmd-N (Figure 5A and C), and pro-IL-1β (Figure 5A and D) in liver of nontreated wild-type and caspase-11–deficient mice. In addition, we failed to detect the mature IL-1β protein by Western blot in liver of both wild-type and caspase-11–deficient mice (Figure 5A and E). MCD treatment induced the expression of pro-Gsdmd (Figure 5A and B), Gsdmd-N (Figure 5A and C), pro-IL-1β (Figure 5A and D), and matures IL-β (Figure 5A and E) in liver of wild-type mice, indicating MCD induced the activation of Gsdmd and IL-1β. In contrast, MCD-treated caspase-11–deficient mice had significantly decreased protein level of pro-Gsdmd (Figure 5A and B), Gsdmd-N (Figure 5A and C), pro-IL-1β (Figure 5A and D), and mature IL-β (Figure 5A and E) in liver when compared with MCD-treated wild-type. Wild-type mice and caspase-11–deficient mice had similar protein level of pro-caspase-1 (Figure 5A and F) and cleaved caspase-1 (Figure 5A and G) in liver. MCD treatment significantly decreased the protein level of pro-caspase 1 (Figure 5A and F) while increased the protein level of active caspase-1 (Figure 5A and G) in both wild-type mice and caspase-11–deficient mice. In addition, the active caspase 1 level in caspase 11–deficient mice was significantly lower than that in wild-type mice, indicating there was less caspase 1 activation in liver of MCD-treated caspase-11–deficient mice. Consistently, we detected less Gsdmd-N expression in hepatocytes of MCD-treated caspase-11–deficient mice (Figure 5H and I). Collectively. these results demonstrated that caspase-11 deficiency attenuated the MCD-induced activation of Gsdmd and IL-1β.

Figure 5.

Deletion of caspase-11–inhibited MCD-induced hepatocytic pyroptosis in mice.Casp11+/+ (WT) or Casp 11–/– mice were treated with MCD for 8 weeks to induce NASH. The protein level of (A, B) pro-Gsdmd, (A, C) Gsdmd-N, (A, D) pro-IL-1β, (A, E) mature IL-1β (p17), (A, F) pro-caspase 1, and (A, G) cleaved caspase 1 was detected by Western blot. (H, I) The pyroptosis in liver was evaluated by immunohistochemistry on Gsdmd-N and (H) the percentage of Gsdmd-N+ cells were quantified. n = 5 for 2 control groups, n = 8 for 2 MCD groups. ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. ns, no significance.

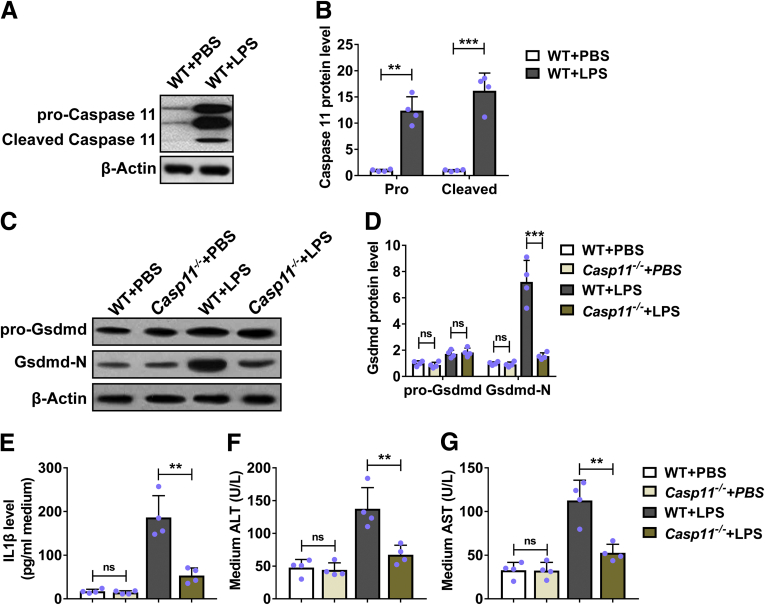

Deficiency of Caspase-11–Inhibited Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Hepatocytic Pyroptosis and Damage In Vitro

We continued to evaluate the effects of caspase-11 deficiency on hepatocytic pyroptosis in vitro. We treated primary hepatocytes from wild-type mice with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and found that LPS induced the expression of both pro-caspase-11 and elevated caspase-11 (Figure 6A and B), indicating that LPS induced the activation of caspase-11 in primary hepatocytes. We further treated primary hepatocytes from both wild-type and caspase-11–deficient mice and monitored the expression and activation of Gsdmd. As shown in Figure 6C and D, LPS treatment did not induced the expression of pro-Gsdmd in wild-type and caspase-11–deficient primary hepatocytes. We detected obviously increased Gsdmd-N in LPS-treated primary hepatocytes from wild-type mice. In contrast, LPS treatment did not affect the Gsdmd-N level in primary hepatocytes from caspase-11–deficient mice and the Gsdmd-N level was significantly lower than that in primary hepatocytes from wild-type mice. These results indicated that LPS did not induce Gsdmd activation in caspase-11–deficient hepatocytes. Furthermore, LPS induced the expression of IL-1β (Figure 6E), ALT (Figure 6F), and AST (Figure 6G) in wild-type primary hepatocytes. In contrast, LPS-induced production of IL-1β (Figure 6E), ALT (Figure 6F), and AST (Figure 6G) was significantly decreased in caspase-11–deficient primary hepatocytes. Collectively, these results demonstrated that deficiency of caspase-11–inhibited LPS-induced activation of caspase-11 and GSDMD in vitro.

Figure 6.

Deficiency of caspase-11–inhibited LPS-induced hepatocytic pyroptosis and damage in vitro. (A, B) Primary hepatocytes from WT mice were cultured and treated with 1 μg/mL LPS for 6 hours. The protein level of pro-caspase-11 and cleaved caspase-11 was determined by Western blot. n = 4. (C–G) Primary hepatocytes from Casp11+/+ (WT) or Casp 11–/– mice were cultured and exposed to 1 μg/mL LPS for 6 hours. (C, D) The protein level of pro-Gsdmd and Gsdmd-N was detected by Western blot, and (E) the protein level of IL-1β in medium was detected by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. The level of (F) ALT and (G) AST in medium was detected. n = 4. PBS, phosphate-buffered saline. ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001. ns, no significance.

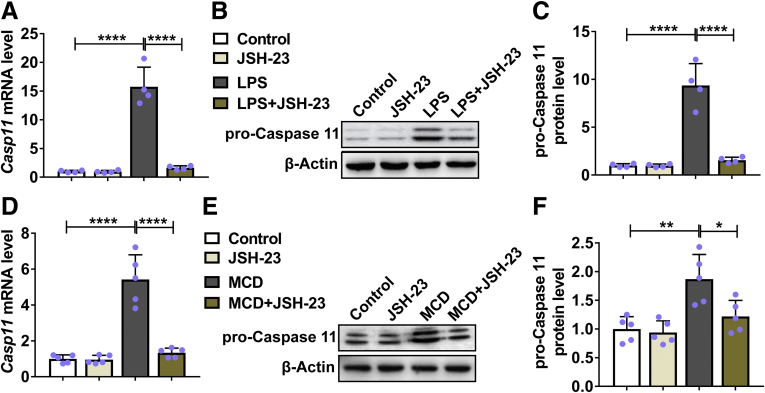

Inhibition of Nuclear Factor κB Suppressed LPS and MCD-Induced Expression of Caspase-11

Nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) has been shown to play essential roles in caspase-11 expression and development of NASH.13,14 To test whether NF-κB was involved in LPS and MCD-induced caspase-11 expression in our study, we administrated JSH-23, an NF-κB inhibitor, to LPS-treated primary hepatocytes and MCD-treated mice. As shown in Figure 7A, LPS treatment promoted the mRNA expression of caspase-11 while the LPS-induced upregulation of caspase-11 was inhibited by JSH-23. Correspondingly, we detected significantly increased protein level of pro-caspase-11 in LPS-treated primary hepatocytes while the protein level of pro-caspase-11 was significantly decreased in JSH-23/LPS-treated primary hepatocytes (Figure 7B and C). Similarly, MCD treatment induced both mRNA (Figure 7D) and protein (Figure 7E and F) expression of caspase-11 in liver of wild-type mice. In contrast, JSH-23 treatment prevented MCD-induced expression of caspase-11.

Figure 7.

Caspase-11 was upregulated by NF-κB signaling both in vitro and in vivo. (A–C) Primary hepatocytes from WT mice were cultured and treated with 1 μg/mL LPS and 20 μM NF-κB inhibitor JSH-23 for 6 hours. The (A) mRNA and (B, C) protein level of caspase-11 were determined by RT-qPCR and Western blot, respectively. n = 4. (D–F) WT mice were fed with MCD or regular diet for 4 weeks with the treatment of 3 mg/kg/d JSH-23 or vehicle by gavage. The (D) mRNA and (E, F) protein level of caspase-11 were determined by reverse-transcription quantitative PCR and Western blot, respectively. n = 8. ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001.

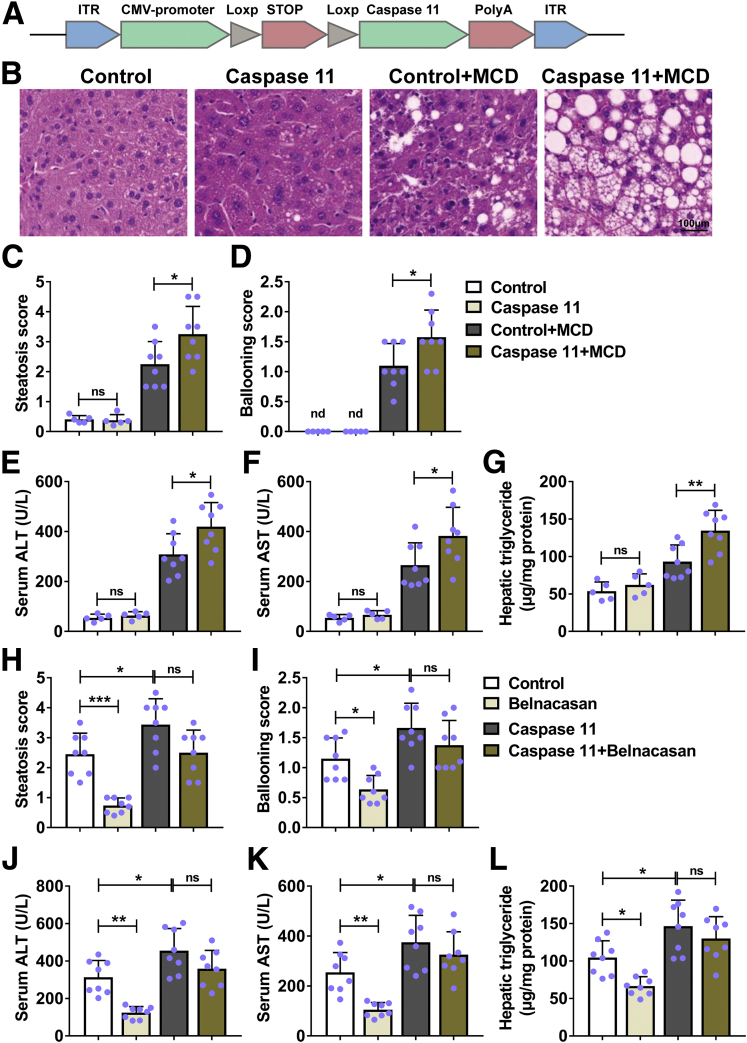

Overexpression of Caspase-11 Exacerbated MCD-Induced Hepatic Steatosis in Mice

Because deficiency of caspase-11–attenuated MCD-induced hepatic steatosis, we continued to detect the effects of caspase-11 overexpression in liver on MCD-induced hepatic steatosis. We made the AAV9-caspase-11 to overexpress caspase-11 only in liver cells of Alb-Cre mice (Figure 8A). Under normal condition, control and caspase-11–overexpressing mice had normal histologic appearance of liver. MCD treatment induced obvious lipid accumulation (vacuoles) in liver both control and caspase-11–overexpressing mice. Furthermore, the vacuoles in liver of caspase-11–overexpressing mice were bigger and more numerous than those in liver of control mice (Figure 8B). Correspondingly, MCD-treated caspase-11–overexpressing mice had significantly higher steatosis score (Figure 8C) and ballooning score (Figure 8D) when compared with MCD-treated control mice. Similarly, we detected significantly increased serum ALT (Figure 8E), serum AST (Figure 8F), and hepatic triglycerides (Figure 8G) in MCD-treated caspase-11–overexpressing mice when compared with MCD-treated control mice. These results demonstrated that overexpression of caspase-11 in liver exacerbated MCD-induced hepatic steatosis in mice. Previous studies demonstrated that caspase-1 was essential for inflammasome activation and pyroptosis in NASH.15,16 To further determine whether the overexpressed caspase-11 is sufficient to exacerbate MCD-induced NASH, we administrated the caspase-1 inhibitor belnacasan to mice. The belnacasan treatment significantly decreased the steatosis score in MCD-treated control mice (Figure 8H). In contrast, belnacasan treatment did not affect the steatosis score in MCD-treated caspase-11–overexpressing mice. Similarly, the belnacasan treatment significantly decreased the ballooning score (Figure 8I), serum ALT (Figure 8J), serum AST (Figure 8K), and hepatic triglycerides (Figure 8L) in MCD-treated control mice, while it did not obviously affect these indexes in MCD-treated caspase-11–overexpressing mice. Taken together, these data demonstrated that overexpression of caspase-11 was sufficient to promote the severity of MCD-induced steatohepatitis in mice.

Figure 8.

Overexpression of caspase-11 was sufficient to increase the severity of MCD-induced steatohepatitis in mice. (A) Representative scheme of the structure of the AAV9-Caspase-11 vector. (B–G) Alb-Cre mice were intravenously injected with control or caspase-11–overexpressing AAV9 and fed with MCD for 4 weeks to induce NASH or fed with regular diet as control. Paraffin-embedded liver sections were stained with (B) hematoxylin and eosin, and (C) hepatic steatosis and (D) ballooning scores were calculated. (E) Serum ALT level, (F) serum AST level, and (G) liver triglycerides were detected. n = 5 for 2 control groups, n = 8 for 2 MCD groups. (H–L) Alb-Cre mice were intravenously injected with control or caspase-11–overexpressing AAV9 and fed with MCD with the treatment of 100 mg/kg/d caspase-1 inhibitor belnacasan or vehicle by gavage for 4 weeks. Paraffin-embedded liver sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and (H) hepatic steatosis and (I) ballooning scores were calculated. (J) Serum ALT level, (K) serum AST level, and (L) liver triglycerides were detected. n = 8 for 4 groups. ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001. ns, no significance.

Discussion

Owing to its high prevalence, NASH is a major health problem worldwide. Pyroptosis has been implicated in NASH and is suggested as potential therapeutic target for NASH treatment.17 Pyroptosis can be induced by caspase-1–mediated canonical inflammatory pathway and caspase-11–mediated noncanonical pathway. Until now, the role of caspase-11 in NASH is not elucidated. In present study, by using MCD-induced NASH mice model, we demonstrated that upregulated caspase-11 was associated with NASH. Caspase-11–deficient mice had significantly decreased liver injury and inflammation, and downregulated activation of GSDMD and IL-1β. In contrast, mice with overexpressed caspase-11 in liver had significantly increased liver damage. Therefore, our study revealed the crucial role of caspase-11 in NASH, which suggested that targeting caspase-11 could be a therapeutic approach to treat NASH.

Increasing evidences have suggested inflammasome and pyroptosis are important drivers of NASH. Inflammasome is multiple protein complex which is composed of a sensor (eg, NLRP3), an adaptor (ASC), and a protease (pro-caspase-1).18 Once the inflammasome assembles, it activates caspase-1, which further induces the cleavage or activation of IL-1β and IL-18. Activated caspase-1 cleaves the GSDMD to GSDMD-N, which forms membrane pores on host cell membrane, regulates nonconventional secretion of IL-1β, and leads to pyroptosis.19 Besides the caspase-1–mediated conventional pathway, caspase-11 has been shown to cleave GSDMD and induce pyroptosis for noncanonical inflammasome signaling.20 Caspase-11 directly binds to LPS and triggers GSDMD cleavage and pyroptosis, and promotes the assembly of the NLRP3 inflammasome, leading to caspase-1 activation. In present study, we detected significantly increased pro-caspase-11 and active caspase-11 in liver of MCD-induced NASH mice, suggesting the potentials roles of caspase-11 in NASH. Upregulated activation of caspase-11 could result in upregulated pyroptosis,21 which was correlated to obvious liver pathology observed in liver of MCD-treated mice. Interestingly, we observed significantly decreased liver pathology in MCD-treated caspase-11–deficient mice, indicating the positive role of caspase-11 in promoting NASH. This correlation was further confirmed in caspase-11–overexpressing mice. We found that mice with overexpressed caspase-11 in liver had more severe liver damage after MCD treatment when compared with wild-type mice. In MCD-treated caspase-11–deficient mice, we also observed significantly decreased activation of GSDMD. The decreased activation of GSDMD contributed to the attenuation of liver damage in NASH mice, which is consistent to previous finding that GSDMD–deficient mice were protected from MCD-induced steatosis and inflammation.9

The presence of fibrosis is another important factor in NASH. In MCD-induced NASH mice, obviously upregulation of fibrosis-related factors was observed. The contribution of caspase-11 to fibrosis has been described previously. Using unilateral ureteral obstruction mice model, Miao et al22 found that caspase-11 inhibition significantly blunted the expression of TGF-β, fibronectin, and collagen 1 in obstructed kidney. They further demonstrated that caspase-11 promoted renal fibrosis by activating caspase-1 and IL-1β maturation. In the present study, the deficiency of caspase-11 resulted in decreased expression of fibrosis-related factors including TGF-β, α-SMA, and alpha-1 type I collagen. Our study further implicated the involvement of caspase-11 in fibrosis.

LPS directly bind to and activate caspase-11. Upregulated serum LPS and localization of hepatocyte LPS was observed. Compared with normal mice, increased LPS serum levels and LPS hepatocyte localization were detected in mice with NASH.23 These observations elucidated the possible original source for caspase-11 activation. In canonical inflammatory pathway, caspase-1 could directly cleave pro-IL-1β and produce the activated IL-1β. In contrast, caspase-11 itself does not cleave pro-IL-1β. Caspase-11 needs to induce NLRP3 activation through an unknown mechanism to activate caspase-1, and then induce the activation of IL-1β.24 Blockages of NLRP3 and caspase-1 have been shown to attenuate development of NASH and liver fibrosis.15,16 In present study, we found that in caspase-11–deficient mice the MCD-induced caspase-1 activation was also decreased. This finding confirmed that caspase-11 contributes to caspase-1 activation. However, we did not detect the activation of NLRP3 inflammasome in present study. It should be very useful to detect the activation of NLRP3 in caspase-11–deficient mice with NASH.

Conclusion

Caspase-11–deficient mice had significantly decreased liver injury, fibrosis, and inflammation after MCD treatment. Caspase-11 deficiency ameliorated hepatocytic pyroptosis in NASH.

Materials and Methods

Mice Treatment

Six-week-old C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Beijing, China). Age-matched Casp11–/– mice (stock#024698) and Alb1-cre mice (stock#016832) were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Shanghai, China). To induce NASH, mice were fed with an MCD (Trophic Animal Feed High-Tech, Nantong, China) for 8 weeks. Control mice were fed with a control diet. There were 5 mice in the control group and 8 mice in the MCD group. Eight weeks after treatment, live animals were harvested for analysis. In certain experiments, 4 weeks after MCD treatment, mice were administrated with NF-κB inhibitor JSH-23 (Selleckchem, Dallas, TX) 3 mg/kg/d by oral gavage for 4 weeks.

To induce overexpression of caspase-11 in Alb1-cre mice, Alb-Cre mice were intravenously injected with control or full-length caspase-11–overexpressing AAV9 (Shanghai Liangtai Biotech, Shanghai, China) at a dose of 1012 vg/200 μL/mouse through the tail vein, and then fed with MCD for 4 weeks to induce NASH. In certain experiments, mice were also treated with belnacasan 100 mg/kg/d by oral gavage for 4 weeks.

All animal studies were approved by the ethics commitment of Wuxi No. 2 People’s Hospital, Affiliated Wuxi Clinical College of Nantong University.

Isolation and Treatment of Primary Hepatocytes

Primary hepatocytes were isolated from mice by collagenase perfusion as described previously.25,26 The hepatocytes were seeded in plates coated with collagen (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and cultured in Williams’ E medium containing 1% bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO). Cells were treated with 1 μg/mL LPS (E. coli O111:B4; Invitrogen, San Diego, CA) alone or treated with 1 μg/mL LPS together with 20 μM NF-κB inhibitor JSH-23 for 6 hours. The cell culture supernatant and cells were harvested for analysis.

Western Blot

The total proteins were extracted using RIPA lysis buffer (Abcam, Beijing, China). Protein concentrations were measured using BCA Protein Assay Kit (Abcam); 20 μg proteins were run on sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gel and then transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. After blocking, membranes were incubated with primary antibodies for overnight at 4°C. Next day, membranes were washed and blotted with horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibodies. Immunoreactive bands were detected using ECL Substrate Kit (Abcam). Primary antibodies used in present study were listed as follows: anti-caspase-11 (#14340; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), Anti-GSDMD (#ab209845; Abcam), anti-GSDMD-N (SAB1307178; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), anti-Pro-IL-1β (#12242; Cell Signaling Technology), anti-cleaved IL-1β (#52718; Cell Signaling Technology), and anti-β-actin (Proteintech, Wuhan, China). The band intensity was quantitated and analyzed by ImageJ (Version 1.8.0_172, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).

Immunohistochemistry

Liver tissues were harvested, fixed, and then embedded with paraffin. The blocks were cut into sections for staining. Briefly, sections were deparaffinized and antigen were retrieved. After blocking, the slides were incubated with anti-GSDMD-N (Sigma-Aldrich) for overnight at 4°C. Then biotinylated secondary antibody was incubated. Finally, the slides were incubated with streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase and DAB substrate.

Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction

Total RNAs from liver tissues were extracted by TRIZOL reagent (Thermo Fisher) and then reverse transcribed using PrimeScript RT Reagent Kit (Takara, Beijing, China). Real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) cycles were programmed on a QuantStudio 3 Real-Time system (Thermo Fisher) and SYBR green PCR Master Mix (Thermo Fisher) was used. Primers used in reverse-transcription PCR included: caspase-11 forward: 5′-ACAAACACCCTGACA AACCAC-3′, reverse: 5′-CACTGCGTTCAGCATTGTTAAA-3′; TGF-β forward: 5′-CTCCC GTGGCTTCTAGTGC-3′, reverse: 5′-GCCTTAGTTTGGACAGGATCTG-3′; α-SMA forward: 5′- GTCCCAGACATCAGGGAGTAA-3′, reverse: 5′-TCGGATACTTCAGCGTCAGGA-3′; Col1a1: forward: 5′- GCTCCTCTTAGGGGCCACT -3′, reverse: 5′- CCACGTCTCACCATT GGGG -3′; F4/80 forward: 5′-TGACTCACCTTGTGGTCCTAA-3′, reverse: 5′- CTTCCCAG AATCCAGTCTTTCC -3′; GAPDH forward: 5′-AGGTCGGTGTGAACGGATTTG -3′, reverse: 5′- TGTAGACCATGTAGTTGAGGTCA -3′.

Histopathology

Liver tissues were harvested and fixed. The sections were subjected to hematoxylin and eosin staining. The steatosis and ballooning were assessed blindly by an experienced liver pathologist as described previously.16,27

AST/ALT Analysis

Serum AST and serum ALT levels were measured using Aspartate Aminotransferase Activity Assay Kit (Abcam) and Alanine Transaminase Activity Assay Kit (Abcam) following manufacturer’s protocols.

Hepatic Triglycerides Measurement

Liver triglycerides level was measured using Triglyceride Assay Kit (Abcam) following manufacturer’s protocols.

Flow Cytometry

The single-cell suspension of liver was prepared using Liver Dissociation Kit (Miltenyi Biotec, Shanghai, China). Cells were stained with anti-CD45 and analyzed on BD Calibur flow cytometer (Beckton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Data was analyzed using FlowJo (Version 10.7, FlowJo, Ashland, OR).

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

The levels of IL-1β, TNF-α, and CCL2 were measured by commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits following manufacture’s protocols (Abcam).

Statistics Analysis

Data was presented as mean ± SD and analyzed using 2-tailed t test or 1-way analysis of variance with a Tukey’s post hoc test in GraphPad Prism 7 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). When the P value was <.05, the difference was termed as significant.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest The authors disclose no conflicts.

Funding The study was supported by the Gastroenterology of Key Disciplines from Wuxi (ZDXK002), the Academician Workstation of No. 2 People’s Hospital of Wuxi City (CYR1705), the Wuxi Medical Key Talent Project (ZDRC029), the Wuxi Sci-Tech Development Fund (CSE31N1603), the Wuxi Municipal Commission of Health and Family Planning Project (MS201720 and MS201814), the Scientific Research Surface Project of Wuxi Health Commission (202028), and the Top Talent Support Program for young and middle-aged people of Wuxi Health Committee (HB2020025 and BJ2020027).

Contributor Information

Gaojue Wu, Email: wugaojue@163.com.

Hong Tang, Email: th3166@njmu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Cotter T.G., Rinella M. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease 2020: the state of the disease. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:1851–1864. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.01.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diehl A.M., Day C. Cause, pathogenesis, and treatment of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:2063–2072. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1503519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams C.D., Stengel J., Asike M.I., Torres D.M., Shaw J., Contreras M., Landt C.L., Harrison S.A. Prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis among a largely middle-aged population utilizing ultrasound and liver biopsy: a prospective study. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:124–131. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Angulo P., Kleiner D.E., Dam-Larsen S., Adams L.A., Bjornsson E.S., Charatcharoenwitthaya P., Mills P.R., Keach J.C., Lafferty H.D., Stahler A., Haflidadottir S., Bendtsen F. Liver fibrosis, but no other histologic features, is associated with long-term outcomes of patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:389–397.e10. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.04.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wree A., Mehal W.Z., Feldstein A.E. Targeting cell death and sterile inflammation loop for the treatment of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Semin Liver Dis. 2016;36:27–36. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1571272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nirmala J.G., Lopus M. Cell death mechanisms in eukaryotes. Cell Biol Toxicol. 2020;36:145–164. doi: 10.1007/s10565-019-09496-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fink S.L., Cookson B.T. Pillars article: Caspase-1-dependent pore formation during pyroptosis leads to osmotic lysis of infected host macrophages. Cell Microbiol. 2006. 8: 1812-1825. J Immunol. 2019;202:1913–1926. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shi J., Zhao Y., Wang K., Shi X., Wang Y., Huang H., Zhuang Y., Cai T., Wang F., Shao F. Cleavage of GSDMD by inflammatory caspases determines pyroptotic cell death. Nature. 2015;526:660–665. doi: 10.1038/nature15514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu B., Jiang M., Chu Y., Wang W., Chen D., Li X., Zhang Z., Zhang D., Fan D., Nie Y., Shao F., Wu K., Liang J. Gasdermin D plays a key role as a pyroptosis executor of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in humans and mice. J Hepatol. 2018;68:773–782. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crowley S.M., Vallance B.A., Knodler L.A. Noncanonical inflammasomes: Antimicrobial defense that does not play by the rules. Cell Microbiol. 2017;19:12730. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang Z., Shao X., Jiang N., Mou S., Gu L., Li S., Lin Q., He Y., Zhang M., Zhou W., Ni Z. Caspase-11-mediated tubular epithelial pyroptosis underlies contrast-induced acute kidney injury. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9:983. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-1023-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang X., Feng Y., Xiong G., Whyte S., Duan J., Yang Y., Wang K., Yang S., Geng Y., Ou Y., Chen D. Caspase-11, a specific sensor for intracellular lipopolysaccharide recognition, mediates the non-canonical inflammatory pathway of pyroptosis. Cell Biosci. 2019;9:31. doi: 10.1186/s13578-019-0292-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schauvliege R., Vanrobaeys J., Schotte P., Beyaert R. Caspase-11 gene expression in response to lipopolysaccharide and interferon-gamma requires nuclear factor-kappa B and signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) 1. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:41624–41630. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207852200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dela Pena A., Leclercq I., Field J., George J., Jones B., Farrell G. NF-kappaB activation, rather than TNF, mediates hepatic inflammation in a murine dietary model of steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:1663–1674. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morrison M.C., Mulder P., Salic K., Verheij J., Liang W., van Duyvenvoorde W., Menke A., Kooistra T., Kleemann R., Wielinga P.Y. Intervention with a caspase-1 inhibitor reduces obesity-associated hyperinsulinemia, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis and hepatic fibrosis in LDLR–/–.Leiden mice. Int J Obes (Lond) 2016;40:1416–1423. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2016.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mridha A.R., Wree A., Robertson A.A.B., Yeh M.M., Johnson C.D., Van Rooyen D.M., Haczeyni F., Teoh N.C., Savard C., Ioannou G.N., Masters S.L., Schroder K., Cooper M.A., Feldstein A.E., Farrell G.C. NLRP3 inflammasome blockade reduces liver inflammation and fibrosis in experimental NASH in mice. J Hepatol. 2017;66:1037–1046. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beier J.I., Banales J.M. Pyroptosis: An inflammatory link between NAFLD and NASH with potential therapeutic implications. J Hepatol. 2018;68:643–645. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martinon F., Burns K., Tschopp J. The inflammasome: a molecular platform triggering activation of inflammatory caspases and processing of proIL-beta. Mol Cell. 2002;10:417–426. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00599-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu X., Zhang Z., Ruan J., Pan Y., Magupalli V.G., Wu H., Lieberman J. Inflammasome-activated gasdermin D causes pyroptosis by forming membrane pores. Nature. 2016;535:153–158. doi: 10.1038/nature18629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kayagaki N., Stowe I.B., Lee B.L., O'Rourke K., Anderson K., Warming S., Cuellar T., Haley B., Roose-Girma M., Phung Q.T., Liu P.S., Lill J.R., Li H., Wu J., Kummerfeld S., Zhang J., Lee W.P., Snipas S.J., Salvesen G.S., Morris L.X., Fitzgerald L., Zhang Y., Bertram E.M., Goodnow C.C., Dixit V.M. Caspase-11 cleaves gasdermin D for non-canonical inflammasome signalling. Nature. 2015;526:666–671. doi: 10.1038/nature15541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cheng K.T., Xiong S., Ye Z., Hong Z., Di A., Tsang K.M., Gao X., An S., Mittal M., Vogel S.M., Miao E.A., Rehman J., Malik A.B. Caspase-11-mediated endothelial pyroptosis underlies endotoxemia-induced lung injury. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:4124–4135. doi: 10.1172/JCI94495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miao N.J., Xie H.Y., Xu D., Yin J.Y., Wang Y.Z., Wang B., Yin F., Zhou Z.L., Cheng Q., Chen P.P., Zhou L., Xue H., Zhang W., Wang X.X., Liu J., Lu L.M. Caspase-11 promotes renal fibrosis by stimulating IL-1beta maturation via activating caspase-1. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2019;40:790–800. doi: 10.1038/s41401-018-0177-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carpino G., Del Ben M., Pastori D., Carnevale R., Baratta F., Overi D., Francis H., Cardinale V., Onori P., Safarikia S., Cammisotto V., Alvaro D., Svegliati-Baroni G., Angelico F., Gaudio E., Violi F. Increased liver localization of lipopolysaccharides in human and experimental NAFLD. Hepatology. 2020;72:470–485. doi: 10.1002/hep.31056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kayagaki N., Warming S., Lamkanfi M., Vande Walle L., Louie S., Dong J., Newton K., Qu Y., Liu J., Heldens S., Zhang J., Lee W.P., Roose-Girma M., Dixit V.M. Non-canonical inflammasome activation targets caspase-11. Nature. 2011;479:117–121. doi: 10.1038/nature10558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van Rooyen D.M., Larter C.Z., Haigh W.G., Yeh M.M., Ioannou G., Kuver R., Lee S.P., Teoh N.C., Farrell G.C. Hepatic free cholesterol accumulates in obese, diabetic mice and causes nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1393–1403. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.06.040. 1403.e1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clayton D.F., Darnell J.E., Jr. Changes in liver-specific compared to common gene transcription during primary culture of mouse hepatocytes. Mol Cell Biol. 1983;3:1552–1561. doi: 10.1128/mcb.3.9.1552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aly F.Z., Kleiner D.E. Update on fatty liver disease and steatohepatitis. Adv Anat Pathol. 2011;18:294–300. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0b013e318220f59b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]