Abstract

The volumes of a cell [cell volume (CV)] and its organelles are adjusted by osmoregulatory processes. During pinocytosis, extracellular fluid volume equivalent to its CV is incorporated within an hour and membrane area equivalent to the cell’s surface within 30 min. Since neither fluid uptake nor membrane consumption leads to swelling or shrinkage, cells must be equipped with potent volume regulatory mechanisms. Normally, cells respond to outwardly or inwardly directed osmotic gradients by a volume decrease and increase, respectively, i.e., they shrink or swell but then try to recover their CV. However, when a cell death (CD) pathway is triggered, CV persistently decreases in isotonic conditions in apoptosis and it increases in necrosis. One type of CD associated with cell swelling is due to a dysfunctional pinocytosis. Methuosis, a non-apoptotic CD phenotype, occurs when cells accumulate too much fluid by macropinocytosis. In contrast to functional pinocytosis, in methuosis, macropinosomes neither recycle nor fuse with lysosomes but with each other to form giant vacuoles, which finally cause rupture of the plasma membrane (PM). Understanding methuosis longs for the understanding of the ionic mechanisms of cell volume regulation (CVR) and vesicular volume regulation (VVR). In nascent macropinosomes, ion channels and transporters are derived from the PM. Along trafficking from the PM to the perinuclear area, the equipment of channels and transporters of the vesicle membrane changes by retrieval, addition, and recycling from and back to the PM, causing profound changes in vesicular ion concentrations, acidification, and—most importantly—shrinkage of the macropinosome, which is indispensable for its proper targeting and cargo processing. In this review, we discuss ion and water transport mechanisms with respect to CVR and VVR and with special emphasis on pinocytosis and methuosis. We describe various aspects of the complex mutual interplay between extracellular and intracellular ions and ion gradients, the PM and vesicular membrane, phosphoinositides, monomeric G proteins and their targets, as well as the submembranous cytoskeleton. Our aim is to highlight important cellular mechanisms, components, and processes that may lead to methuotic CD upon their derangement.

Keywords: pinocytosis, macropinocytosis, endocytosis, intracellular vesicle, ion transport, cell volume regulation, cell death, methuosis

Introduction

Individual cells have the same need entire organisms have: They have to drink. At the cellular level, water drinking is known as pinocytosis and the fluid-containing organelle is the pinosome. Fluid uptake, intracellular distribution, and processing require precise spatial and temporal coordination of membrane and cytoskeletal proteins. Macropinocytosis is an actin-driven process, where a cup-like structure emerges from the cell surface, which engulfs extracellular fluid and forms a vesicle (Swanson and Watts, 1995; Swanson, 2008; Kerr and Teasdale, 2009; Lim and Gleeson, 2011; Hinze and Boucrot, 2018; Doodnauth et al., 2019; King and Kay, 2019; Swanson and King, 2019). The vesicle membrane contains ion channels and transporters that are used for the flux of water, osmolytes, and nutrients, and it is decorated by distinct phospholipids and proteins that are required for intracellular sorting and transport of the organelle (Bohdanowicz and Grinstein, 2013; Levin et al., 2015; Freeman and Grinstein, 2018; Williamson and Donaldson, 2019; Stow et al., 2020) (Table 1). Macropinocytosis serves seemingly unrelated cellular functions, such as nutrition acquisition to satisfy cellular energy demands (Recouvreux and Commisso, 2017; Palm, 2019; Lin et al., 2020), immune surveillance leading to antigen presentation to lymphocytes (Lanzavecchia, 1996; Von Delwig et al., 2006; Liu and Roche, 2015; Canton, 2018), intracellular replication of pathogenic bacteria (Bloomfield and Kay, 2016; Di Russo Case et al., 2016), and CD by drinking too much fluid, i.e., methuosis (Maltese and Overmeyer, 2014, 2015). Careful examination of these functions showed similarities in the initial steps of fluid uptake and differences in the final processing steps, such as fusion or not fusion with lysosomes.

TABLE 1.

Some characteristics and ion concentrations of macropinocytosis and the endolysosomal pathway.

| Appearance | PIPs | Decoration | Ψm (mV) | pH | Na+ (mM) | K+ (mM) | Cl– (mM) | HCO3– (mM) | Ca2+ (mM) | ||

| ECF NP |  |

Irregular | PI(4,5)P2 | Rab5, Rab20 | ∼−30 to −70 | 7.4 | 120–150 | 4–5 | 110–120 | 24–27 | 2 |

| ICF | 6.9 | 12 | 140 | 20–80 | 8–15 | 0.1–2 | |||||

| EE |  |

Spherical | PI3P, PI(3,4)P2 | Rab4, Rab5, Rab20 | 10–20 | 6.0–6.2 | 20–30 | 0.003–2 | |||

| LE |  |

Tubulated | PI3P, PI(3,5)P2 | Rab7, Rab9, Rab20 | 5.0–5.5 | 20 | 40–70 | 2.5 | |||

| MVB |  |

Intraluminal vesicles | PI3P + PI(3,5)P2 | Rab7, Rab9, Rab20 | 5.5 | 40 | 0.009 | ||||

| LE/LY Hybrid |  |

PI3P | Rab,7, LAMP1 | ||||||||

| LY |  |

Spherical | PI(3)P + PI(3,5)P2 | LAMP1 | ∼−40 to +20 | 4.3–5.5 | 20–145 | 2–60 | >80 | 0.4–0.7 |

ECF, extracellular fluid; ICF, intracellular fluid; NP nascent pinosome; EE, early endosome; LE, late endosome; MVB, multivesicular body; LY, lysosome. For details, see text. References: (Sonawane and Verkman, 2003; Dong et al., 2010; Morgan et al., 2011; Scott and Gruenberg, 2011; Welliver and Swanson, 2012; Bohdanowicz and Grinstein, 2013; Ishida et al., 2013; Stauber and Jentsch, 2013; Chang et al., 2014; Egami et al., 2014; Levin et al., 2015; Saha et al., 2015; Xu and Ren, 2015; Xiong and Zhu, 2016; Chakraborty et al., 2017; Kim et al., 2018; Sterea et al., 2018; King and Kay, 2019; Li P. et al., 2019; Adjemian et al., 2020; Jin et al., 2020; Trivedi et al., 2020; Chadwick et al., 2021b; Riess et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2021).

The prototypic experiments examining pinocytosis were done on macrophages and malignant cells by Lewis in the 1930s (Lewis, 1936, 1937). Then, Lewis was among the few researchers using time-lapse microscopy to study the dynamics of living cells. Lewis introduced the term “pinocytosis” to describe the fact that ruffle formation is associated with vesicle formation and uptake of extracellular fluid (Lewis, 1936, 1937). In line with Lewis’s statement “Pinocytosis is easily seen in motion pictures” (Lewis, 1937), we use video microscopy to visualize the dynamics of pinocytosis (Figure 1 and Supplementary Videos 1, 2). In the words of Lewis, Supplementary Video 1 shows that vesicles “taken in vary greatly in size,” “several fuse… to form larger ones,” “move centrally,” and “finally reach… the neighborhood of… the nucleus” (Lewis, 1937). Lewis also suggested that proteins in the vesicles are “split by the digestive enzymes into simpler products which can be utilized or can diffuse out of the cell.” He also related the “disappearance” of the vesicles “with the completion of the digestion of their contents” as the vesicles “slowly shrink in size and disappear, leaving a small granule…” (Lewis, 1937). Lewis’s experiments also showed that the cells do not increase in volume, although “they may take in several times their volume of fluid” and he “assumed that the fluid diffuses out of the cells when the globules disappear” (Lewis, 1937). These experiments demonstrate that volume regulatory processes at the cellular and organelle levels are of paramount importance to maintain CV while cells incorporate large volumes of extracellular fluid and digest macromolecules present in the fluid. The fact that the fluid taken up by macropinocytosis outweighs its elimination by recycling vesicles (Swanson, 1989; Choy et al., 2018) highlights that VVR and CVR are inevitably linked to each other. This becomes evident from the massive cell swelling seen upon inhibition of water channels in pinocytosing cells (De Baey and Lanzavecchia, 2000). Furthermore, considering that the total volume of the endolysosomal compartment can make up a substantial part of the total CV (Choy et al., 2018) makes evident that the exchange of osmotically active solutes between the endolysosomal compartment and the cytosol will strictly affect the volumes of either part.

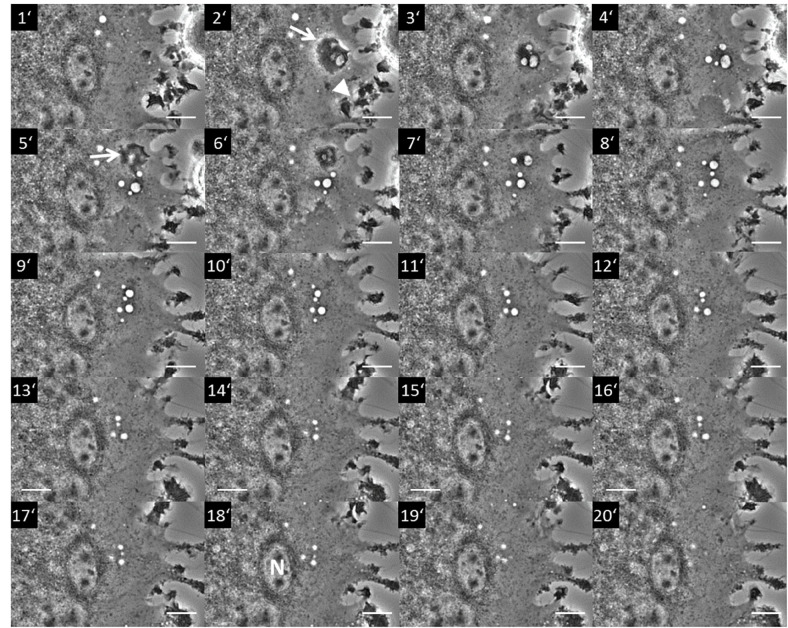

FIGURE 1.

Macropinocytosis occurring in a section of a multinucleated giant cell from a rat non-parenchymal hepatic cell line putatively representing immortalized monocytes (Kupffer cells). The image series shows a section of a giant cell where pinocytosis occurs. The process starts with the formation of a membrane ruffle at minute 2 (2′; arrow) from which an array of vesicles (pinosomes) originates (3′–4′). Further ruffling can be seen at the cell periphery (2′; arrowhead). A second ruffle is forming at minute 5 (5′; arrow) from which additional pinosomes derive (5′–7′). The whole pinosome array subsequently moves toward the center area of the giant cell (8′–18′) locating to the vicinity of a nucleus (N in 18′). Terminally, the vesicles start to disappear in the perinuclear (pericentral) cytosol (20′). Scale bar = 10 μm. The whole live cell imaging sequence can be seen in Supplementary Video 1.

Given the importance of CVR, a central question is: What determines the size of a vesicle? That is, which transporters and ion channels in the PM and vesicle membrane are activated, incorporated, and terminated at which spatial and temporal check points? How does the macropinosomal solute composition and the vesicular membrane properties change after having gulped a lot of extracellular fluid during maturation along the endolysosomal pathway, and what are the determinants of this change? And finally: How are these cellular and subcellular volume regulatory mechanisms altered in methuosis?

To understand subcellular volume regulation, findings related to CVR provide clues to identify factors maintaining the set points of the vesicle.

As ion channels and transporters in the PM are central in CVR, they also contribute to VVR (Freeman and Grinstein, 2018; Freeman et al., 2020; Chadwick et al., 2021b). Thus, Lewis’s statement in the 1930s that “The factors involved in the diffusion of the fluid out of the cell are as mysterious as most of the other processes which take place” (Lewis, 1937) is now transforming to hypotheses trying to explain CVR and VVR in macropinocytosis at the molecular level and by facts generated by electrophysiological, molecular–biological, and imaging studies. Notably, Freeman and Grinstein (2018); Freeman et al. (2020), and Chadwick et al. (2021b) demonstrated that contributions from ion transporters are essential for normal shrinkage in macropinosome maturation.

This review focuses on the complex mutual interplay between extracellular and intracellular ions and ion gradients, the PM and vesicular membrane, phosphoinositides, monomeric G proteins and their targets, as well as the submembranous cytoskeleton in pinocytosis, with special emphasis on its connection to CVR and VVR. It aims at highlighting important cellular mechanisms and components that govern these processes and that may lead to methuotic cell death upon their derangement.

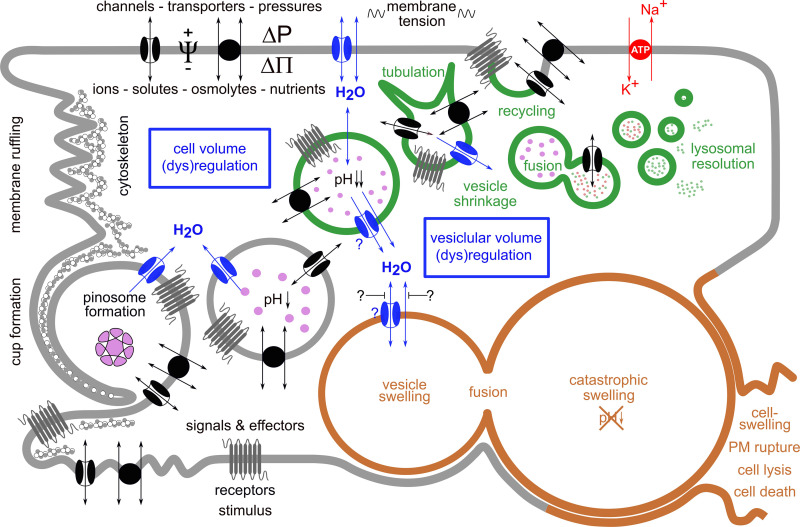

Figure 2 schematically shows key steps of vesicle/vacuole formation and processing during normal macropinocytosis and in methuosis.

FIGURE 2.

Simplified scheme of key processes in vesicle/vacuole formation and processing during normal macropinocytosis and in methuosis. Macropinocytosis is an actin-driven process that is triggered by various stimuli. It starts with ruffling of the plasma membrane (PM) and formation of a pinocytotic cup, which engulfs extracellular fluid and forms a pinosome by membrane fusion at the tip of a lamellipodium-like structure. Its membrane contains ion channels and transporters, receptors, among other various PM constituents, e.g., phospholipids. The nascent pinosome unselectively engulfs extracellular fluid, along with its ions, nutrients, and metabolites and eventually also toxins or drugs. It may also enclose particulate matter-like exosomes, micro- or nanoparticles, or pathogens such as bacteria and viruses (pink enclosed structure). Under normal conditions (green vesicles), pinosomes move centripetally, become more and more acidic, shrink along their route, and become tubulated, a process necessary for proper sorting and recycling of the vesicles and their cargo. This requires also its decoration with distinct phospholipids and proteins (not shown). Reusable membrane proteins may become inserted again into the PM when vesicles fuse with it. This also recycles incorporated membrane back to the PM and relieves its tension. Vesicles designated for delivery of their contents to lysosomes—for further processing, digestion, or destruction—fuse with them and finally resolve. The resulting products may be further used, e.g., for the cell’s nutrition. To ensure these processes, cell volume regulation and vesicular volume regulation must work hand in hand. This becomes evident from the fact that during pinocytosis, an extracellular fluid volume and membrane area equivalent to the cell’s volume and to the cell’s surface are incorporated within 1 h and 30 min, respectively. The volume regulatory mechanisms involve movement of ions and osmolytes across the PM by means of specific ion channels and transporters. The driving forces for these fluxes are determined by the electrochemical gradients. Water flux is driven mainly by the osmotic (ΔΠ) but eventually also by the hydrostatic (ΔP) pressure differences. The water permeability of the PM is greatly enhanced by water channels (aquaporins, blue). All of these movements are primarily driven by the activity of the Na+/K+-ATPase (red transporter in the PM), an ion pump that moves Na+ ions out of and K+ ions into the cell, while hydrolyzing ATP as energy source. This process sets up the required ionic and osmotic gradients and determines the electrical potential difference Ψ across the PM. The mechanisms for vesicular volume regulation follow the same rules and are in principle identical to those in cell volume regulation, while utilizing their individual set of transporters and channels. In methuosis, a lethal process of aberrant pinocytosis where cells “drink themselves to death,” these processes are severely disturbed (brown vesicles). Fluid uptake by macropinocytosis is enhanced, and instead of shrinking, the vesicles swell, do not acidify, remain non-functional, and do not fuse with lysosomes, but instead they with each other. This leads to the formation of giant vacuoles, catastrophic cell swelling, and consequently to rupture of the PM, cell lysis, and death.

Macropinocytosis

Macropinocytosis is a form of clathrin-independent endocytosis. Ruffling of cholesterol-rich membrane microdomains leads to the unselective incorporation of large volumes of extracellular fluid in macropinosomes with a diameter of 0.2 up to 5.0 μm (Levin et al., 2015; Donaldson, 2019). Macropinocytosis may occur constitutively or be induced by growth factors, chemokines, microbial products, viruses (Freeman et al., 2014; Marques et al., 2017; Canton, 2018; Doodnauth et al., 2019; Tejeda-Munoz et al., 2019), crosslinking of cell surface molecules (Imamura et al., 2011), knockdown of genes (Choi et al., 2017; Fomin et al., 2018; Fomin, 2019; Su et al., 2021), and constitutive expression (Kasahara et al., 2007) or mutations of signal transduction molecules (Yoo et al., 2020). Some cells, like innate immune cells and Ras-transformed cancer cells, are able to perform both forms of macropinocytosis (Amyere et al., 2000; Stow et al., 2020). Importantly, this process ensures that cells incorporate everything animals ingest and digest, including nutrients as well as toxic substances and metabolites released by neighboring cells, exosomes, microparticles, and pathogens, such as bacteria and viruses (Suda et al., 2007; Mercer and Helenius, 2009, 2012; Mercer et al., 2010; Commisso et al., 2013; Bloomfield and Kay, 2016; Jiang et al., 2017; Commisso, 2019). Furthermore, macropinocytosis is involved in cell migration (Wen et al., 2016; Swanson and King, 2019).

Remarkably, within 1 h, a volume equivalent of the entire cytoplasm is incorporated by macropinocytosis, and within 30 min, macropinosome formation requires the entire cellular PM surface (Steinman et al., 1976; Cullen and Steinberg, 2018; Freeman and Grinstein, 2018). Against the compelling background of conserved CV and cell surface, sorting mechanisms distinguishing between recycling and digestion routes are of eminent importance. Membrane recycling is not only of importance for maintaining the cell surface but also for supplying the PM with receptors and transporters, such as neonatal Fc-receptor (Toh et al., 2019), bone morphogenetic protein receptor (Kim et al., 2019), PDGF β-receptor (Schmees et al., 2012), EGF receptor (Chiasson-Mackenzie et al., 2018; Freeman et al., 2020), and other plasmalemmal components such as integrins (Buckley et al., 2016; Freeman et al., 2020) as well as small GTPases, which fuel macropinocytosis (Cullen and Steinberg, 2018). Furthermore, as the intercellular volume is usually small, changes in extracellular ion composition may greatly affect ion gradients, which drive nutrient transporters, e.g., Na+-dependent glucose or amino acid uptake (Ganapathy et al., 2008; Wright et al., 2011; Broer, 2014). This exceptional well-balanced system is keeping CV and cell surface during macropinocytic flow reasonably constant, but puts the cell at risk to damage either when CVR fails or when it accumulates metabolic waste products as seen in lysosomal storage diseases (Platt et al., 2012, 2018; Rappaport et al., 2016). Excessive fluid uptake in in vitro conditions leading to a distinct form of CD has been recently recognized and named methuosis (Maltese and Overmeyer, 2014, 2015).

Ruffle and Cup Formation

Ruffle and cup formation is an actin-driven process, which is closely related to the formation of phagocytic cups and pseudopods (Lim and Gleeson, 2011; Freeman and Grinstein, 2014; Buckley and King, 2017; Williamson and Donaldson, 2019). Actin cytoskeleton rearrangement depends on phospholipids, lipid kinases and phosphatases, small GTPases, actin-modulating proteins, ion channels, and proton (H+) pumps (Welliver and Swanson, 2012). Among the numerous small GTPases, the Ras and Rho family member, Rac1, is critical in the formation of ruffles and macropinocytic cups (Egami et al., 2014; Donaldson, 2019). For small GTPases, the switch from an inactive guanosine diphosphate (GDP)-bound form to an active guanosine triphosphate (GTP)-bound form is facilitated by GEFs, which promote GDP dissociation. The inactivation of the small GTPases is mediated by GTPase-activating proteins (GAPs), which enhance GTP hydrolysis (Cherfils and Zeghouf, 2013). Critically, the activation of the GTPase cycle—activation, inactivation, removal from the membrane—is transient. Oscillations of Ca2+i may drive parallel oscillatory association and dissociation of the Ras-GAP, Rasal (Ras-GTPase–activating-like protein), to and from the PM. Only when bound to the PM, Rasal is active and can inactivate Ras. Thus, Ras is repetitively activated and inactivated (Walker et al., 2004). In macropinocytosis, Ras activity is terminated by RasGAP, which is recruited to the cup as it closes (Veltman et al., 2016; Buckley et al., 2020). When GTPases are persistently activated, e.g., when RasGAPs are inactive like in neurofibromatosis (Bloomfield et al., 2015; Ghoshal et al., 2019) or when Ras is constitutively active like in oncogenic H-Ras mutants, macropinosome formation and maturation deviate from the normal physiological pathway. The Ras-related G protein Rap1 is a negative regulator of Ras (Zwartkruis and Bos, 1999; Nussinov et al., 2020). Rap1 is found in early and late endocytic vesicles and lysosomes (Pizon et al., 1994), and its overexpression negatively regulates macropinocytosis (Seastone et al., 1999). In Dictyostelium discoideum, hyperosmotic stress activates Rap1 and decreases endocytic activity due to cellular acidification (Pintsch et al., 2001), and it promotes the formation of giant vacuoles of pinocytotic origin (Yuan and Chia, 2001).

Notably, in human intestinal cells, hypotonicity increases the activity of the H-Ras–Raf1–Erk signaling pathway (Van Der Wijk et al., 1998). The clustering of Ras proteins in distinct microdomains at the PM (lipid rafts) influences Ras structure, orientation, and Ras-isoform accessibility and thus the activation states of its effectors. Accordingly, GTP-bound H-Ras may remain in a locked state and as such not able to associate with its downstream effectors (Jang et al., 2016; Nussinov et al., 2018). Activation occurs once the lipid-anchored GTPases Ras1 and H-Ras are shifted out of the lipid rafts. This happens upon thinning of the PM in combination with changes of its curvature induced by cell swelling (Cohen, 2018).

Active Rac and Ras are located at the cup wall. Rac1 activation is associated with ruffle formation, and Rac1 inactivation precedes cup closure (Buckley and King, 2017). In Dictyostelium discoideum, the multidomain protein, RGBARG (RCC1, RhoGEF, BAR, and RasGAP-containing protein), orchestrates Ras and Rac activity in a small membrane patch, where RGBARG is localized at the protruding rim region (Buckley et al., 2020). Oncogenic H-Ras promotes the translocation of the vacuolar H+-ATPase (v-ATPase) from intracellular vesicles to the PM. The accumulation of v-ATPase is necessary for the cholesterol-dependent association of Rac1 with the PM, which is a prerequisite for the stimulation of membrane ruffling and macropinocytosis. Knockdown of the v-ATPase or its inhibition suppresses macropinocytosis, while addition of cholesterol to these cells restores both Rac1 membrane localization and macropinocytosis (Ramirez et al., 2019). In addition, Ras binds and activates phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases (PI3Ks), which have a Ras-binding domain (Gupta et al., 2007; Castellano and Downward, 2011; Castellano et al., 2013). Activation of PI3Ks phosphorylates phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate [PI(4,5)P2] to phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate [PI(3,4,5)P3] and promotes its enrichment in the PM (Rupper et al., 2001; Nussinov et al., 2020). In EGF-stimulated A431 cells, PI(4,5)P2 increases in the ruffles-forming macropinocytic cups, reaches its maximum just before macropinosome closure, and then rapidly falls as the cup closes. In contrast, PI(3,4,5)P3 increases locally at the site of macropinosome formation and peaks at the time of closure (Araki et al., 2007). The extension of PI(3,4,5)P3 patches, which can reach a diameter of several micrometers, reflects the balanced activity of PI3Ks and the lipid phosphatase, phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN), which dephosphorylates PI(3,4,5)P3 back to PI(4,5)P2. The kinetics of PI(4,5)P2 and PI(3,4,5)P3 are mechanistically linked to actin-remodeling during macropinocytosis (Araki et al., 1996, 2007; Worby and Dixon, 2014; Swanson and Yoshida, 2019; Nussinov et al., 2020) and to the regulation of many ion channels and transporters relevant to pinocytosis as well as CVR (Araki et al., 1996; Lang et al., 1998; Ritter et al., 2001; Furst et al., 2002; Jakab et al., 2002; Okada, 2004; Lang, 2007; Suh and Hille, 2008; Hoffmann et al., 2009; Abu Jawdeh et al., 2011; Lang and Hoffmann, 2012; Balla, 2013; Hansen, 2015; Hille et al., 2015; Kunzelmann, 2015; Jentsch, 2016; Pasantes-Morales, 2016; De Los Heros et al., 2018; Delpire and Gagnon, 2018; Konig et al., 2019; Okada et al., 2019; Centeio et al., 2020; Larsen and Hoffmann, 2020; Model et al., 2020). For cup closure, the progressive dephosphorylation of PI(3,4,5)P3 seems to be important. Among its dephosphorylation products, PI(3)P has been shown to directly activate the Ca2+-activated K+-channel, KCa3.1, at ruffles, which is necessary for closure (Maekawa et al., 2014). The significance of Ras activation, which peaks shortly after cup closure (Welliver and Swanson, 2012; Egami et al., 2014), as well as of the antagonistic behavior of PI3Ks and PTEN in the initiation and termination of cup formation is nicely documented by the observations that injection of Ras in cells induces ruffle formation, that inhibitors of PI3K inhibit cup closure in macrophages, and that deletion of PTEN in prostate cancer cells enhances macropinocytosis (Bohdanowicz and Grinstein, 2013; Levin et al., 2015; Kim et al., 2018; King and Kay, 2019).

Phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate enrichment promotes the translocation of the serine/threonine protein kinase Akt/PKB via binding to the pleckstrin homology (PH) domain and kinase activation by target of rapamycin complex 2 (TORC2) and 3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase-1 (PDK1) (Yoshida et al., 2018; Kay et al., 2019). Among the downstream targets of Akt is the tuberous sclerosis complex 2 (TSC2), which is—together with TSC1—located on the lysosomal membrane, from which it subsequently dissociates to act as a GAP for the Ras-related small GTPase, Rheb, which in turn activates mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1). In Dictyostelium discoideum downstream of PI(3,4,5)P3, the homologs of mammalian Akt, PkbA, and of the related glucocorticoid-regulated kinase (SGK), PkbR1, as well as their activating protein kinases, TORC2 and PdkA, increase the size of the macropinocytic patch and macropinosome (Kay et al., 2019; Williams et al., 2019). Combined inhibition of mTORC1/mTORC2 induces massive catastrophic macropinocytosis, i.e., methuosis, in cancer cells (Srivastava et al., 2019). Akt and TORC2 target SGK1, which regulates a plentitude of cell functions, including ion channels and transporters (Lang et al., 2018) and endomembrane trafficking (Zhu et al., 2015). SGK transcription is stimulated by cell shrinkage via p38-kinase and inhibited by cell swelling due to transcriptional stop (Waldegger et al., 1997, 2000; Lang et al., 2006, 2018). Furthermore, the isoform Akt3 controls actin-dependent macropinocytosis in macrophages by suppressing the expression of with no lysine kinase 2 (WNK2) and the activity of SGK1, while increased activity of SGK1 leads to stimulation of Cdc42-mediated macropinocytosis of lipoprotein (Ding et al., 2017). However, in macrophages stimulated by macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF), the Akt pathway is induced by this growth factor but not required for macropinosome formation (Yoshida et al., 2015).

In myoblasts, an acute decrease of PM tension leads to phospholipase D2 activation, production of phosphatidic acid, F-actin and development of PI(4,5)P2-enriched membrane ruffling, and macropinocytosis without an increase in PI(3,4,5)P3 (Loh et al., 2019).

In parallel to the lipid and protein phosphorylation cascades, the cortical actin filaments are reorganized. This is controlled by PI3K and PLC, Rac, Cdc42, Arf6, Rab5, and Pak (Swanson, 2008). In the cup region, polymerized actin is seen as a ring-like structure (Hinze and Boucrot, 2018). Active Ras and PIP(3,4,5)P3 coincidentally form patches in macropinosomes, which are surrounded by a ring of the Scar/WAVE complex, an activator of the Arp2/3 complex. Arp2/3 drives actin polymerization by filament branching, leading to the formation of dendritic F-actin, which populates the wall of the cup and forms rings of protrusive actin under the PM and the circular ruffles (Swanson, 2008; Saarikangas et al., 2010; Pollard, 2016; Buckley and King, 2017; Hinze and Boucrot, 2018; Kay et al., 2019; Williamson and Donaldson, 2019). PI(3,4,5)P3 also recruits myosin proteins to macropinocytic cups (Chen et al., 2012). The synthesis of PI(3,4,5)P3 from PI(4,5)P2 occurs simultaneously with the recruitment of Rab5 to the PM in COS-7 cells expressing oncogenic H-RasG12V (Porat-Shliom et al., 2008). Rab5 promotes macropinosome sealing and scission downstream of ruffling. To this end, Rab5-containing vesicles are recruited to circular ruffles of the PM, which requires soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive-factor attachment receptor (SNARE)-dependent endomembrane fusion. This is paralleled by the disappearance of PI(4,5)P2 and accompanies macropinosome closure. The removal of PI(4,5)P2 is dependent on Rab5 through its recruitment of the inositol 5-phosphatase Inpp5b/OCRL and via APPL1, an adaptor protein that regulates vesicle trafficking and endosomal signaling (Maxson et al., 2021). Rab5 and RN-tre, which is a Rab5-specific GAP as well as a Rab5 effector, are also recruited to the PM. RN-tre interacts with actin as well as actinin-4, which contributes to actin bundling (Lanzetti et al., 2004). The Rab5 cycle is active on nascent macropinosomes and stabilizes the macropinosomes. Rab5 activity is increased on macropinosome tubules (Feliciano et al., 2011). In BHK-21 cells, H-RasG12V has been shown to separately activate Rab5 and Rac1 via distinct Ras signal transduction pathways. While Rab5 activation stimulates pinocytosis, Rac1 stimulation causes membrane ruffling but does not contribute to the stimulation of pinocytosis (Li et al., 1997).

Intracellular Trafficking of Macropinosomes

In Dictyostelium, the nascent vesicles lose their actin coat within 1 min after pinching off and internalization (Lee and Knecht, 2002). In rat basophilic leukemia (RBL) cells, “pinosomes… ignite a burst of actin polymerization when they are pinched off from the plasma membrane” and “then move into the cytosol at the tips of short-lived actin ‘comet tails,’” which fade within 2 min after their appearance. These brief bursts of actin polymerization are thought to help move the vesicles into the cytosol (Merrifield et al., 1999). They also require recruitment of annexin-2 to nascent macropinosome membranes as an essential prerequisite for actin polymerization-dependent vesicle locomotion (Merrifield et al., 2001).

Organelle shrinkage concentrates the to-be-digested material and recycles membrane back to the PM. Macropinosomes show two routes of structural adaptations to maximize the organelle surface area and to minimize its volume: tubulation and shrinkage (Freeman and Grinstein, 2018; King and Kay, 2019; Chadwick et al., 2021b). Macropinosomes retrieve v-ATPase from fusion with other vesicles and mature toward acidic organelles that contain hydrolytic enzymes, such as proteases, nucleases, and lipases, which are required for the degeneration of macromolecules, as well as transporters facilitating the efflux of cholesterol, cystine (the disulfide form of cysteine, which is generated during protein degradation), amino acids, cobalamin, and inorganic ions (Neuhaus et al., 2002; Buckley and King, 2017; Trivedi et al., 2020).

Mobilization and maturation of macropinosomes depend on the decoration of the vesicle membrane with distinct small GTPases (Egami et al., 2014; Egami, 2016). Transient activation of ADP-ribosylation factor 6 (Arf6), a member of the Ras superfamily, by the exchange factor, EFA6, promotes PM protrusion, formation of macropinosomes, and recycling of the vesicle membrane back to the PM (Brown et al., 2001). Arf6 colocalizes and activates phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate 5-kinase (PIP 5-kinase), which phosphorylates phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate PI(4)P to PI(4,5)P2 (Egami et al., 2014). Subsequently, PI(4,5)P2 and Cdc42-GTP coordinate the activation of Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome protein (WASP), which promotes the actin-nucleating and actin filament-branching activity of Arp2/3 (Higgs and Pollard, 2000). The recruitment of Arf6 and its exchange factor, ARF nucleotide binding-site opener (ARNO), from cytosol to endosomal membranes relies on v-ATPase-dependent intra-endosomal acidification, thus regulating the protein-degradative pathway (Hurtado-Lorenzo et al., 2006). Persistent activation of Arf6, as seen in the GTP hydrolysis-resistant mutant Arf6Q67L or by overexpression of the PIP 5-kinase, results in the accumulation of macropinosomes. Interestingly, PI(4,5)P2-enriched macropinosomes in apposition to each other fuse with one another and give rise to large vacuoles. Furthermore, entrapped PM proteins in these vacuoles are not recycled (Brown et al., 2001). The GTPase septin is involved in endosome fusion. Whereas septin downregulation decreases macropinosome fusion events as well as lysosomal delivery, septin overexpression increases delivery to lysosomes (Dolat and Spiliotis, 2016).

Early macropinosomes harbor Rab5 (Feliciano et al., 2011; Maxson et al., 2021), which in turn recruits the class III PI3K Vps34, which catalyzes the reaction from PI to PI(3)P (Christoforidis et al., 1999; Kerr and Teasdale, 2009). In macropinosomes routed toward lysosomes, Rab5 is replaced by Rab7 (Racoosin and Swanson, 1993; Kerr et al., 2006; Langemeyer et al., 2018; Morishita et al., 2019). In an analogy to an electrical safety-breaker, Del Conte-Zerial et al. (2008) compare the replacement of Rab5 by Rab7 as a “cut-out switch.” This model predicts that Rab5 drives Rab7 activation above a distinct threshold. Above the threshold, Rab7 shows a self-sustained activity and suppresses Rab5 activity via a negative feedback. In this model, crossing the Rab7 activation threshold excludes reactivation of Rab5 and activation of a different trafficking pathway. Thus, the Rab5 to Rab7 switch ensures a unidirectional route of cargo-loaded macropinosomes toward lysosomes. Using Förster/fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) imaging, Morishita et al. (2019) describe that active Rab5 facilitates Rab7 activation until Rab7 sustains its own activity and inactivates Rab5. Furthermore, recruitment of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis 2 (ALS2) to the macropinosome coincides with Rab5 activation, and ALS2 detachment is associated with Rab5 inactivation (Morishita et al., 2019). In earlier studies using Texas red-labeled dextran macropinosomes, Racoosin and Swanson showed that Rab7-positive macropinosomes fuse with tubular lysosomes (Racoosin and Swanson, 1993). The fate of waste-containing vesicles is not known.

Dysfunction or inhibition of Vps34 or PIKfyve, which phosphorylates PI(3)P to PI(3,5)P2, leads to the formation of massive and progressively exacerbating cytoplasmic vacuolization due to loss of PI(3,5)P2. This requires active v-ATPase activity and a functional Rab5a cycle. Interestingly, the formation of the enlarged vacuoles does not require their acidification (Compton et al., 2016; Saveanu and Lotersztajn, 2016), pointing to an osmotic function of the v-ATPase. In melanoma cells, oncogenic class I PI3K elicits a hyperactive influx of macropinosomes, which is counteracted by Rab7A (Alonso-Curbelo et al., 2015). Furthermore, by stimulating RIN1, which is a Rab5 GEF, activation of H-Ras or H-RasG12V also mediates homotypic fusion of early endosomes, thus leading to endosome enlargement (Roberts et al., 2000; Tall et al., 2001).

Microtubules are associated with peripheral actin/myosin-enriched lamellae, and they are the scaffold for the unidirectional transport of macropinosomes. Critically, inhibitors of microtubule assembly, and the dynein inhibitor ciliobrevin D, decrease fluid uptake, indicating that the microtubules are involved in an early step of macropinocytosis (Williamson and Donaldson, 2019).

Cell Volume Regulation

In general, cells respond to alterations of the osmotic equilibrium with a change of their volume due to water movement into or out of the cell. While an increase in intracellular or a decrease in extracellular osmolarity leads to cell swelling, a decrease in intracellular or an increase in extracellular osmolarity leads to cell shrinkage. Physiologically, such changes arise when cells invade anisotonic extracellular environments, e.g., the renal medulla, or following changes in intracellular osmolyte concentrations, such as during uptake or release of ions or nutrients, but also from metabolic changes, such as formation or degradation of macromolecules, e.g., proteins or glycogen. Likewise, perturbations of the double Donnan equilibrium, established by the so-called pump–leak balance (Okada, 2004; Kay, 2017; Kay and Blaustein, 2019), such as changes in intracellular pH (pHi) or inhibition of the Na+/K+-ATPase by cardiac glycosides or low temperature (Russo et al., 2015), will lead to alterations of CV (for review, see Lang et al., 1998; Ritter et al., 2001; Furst et al., 2002; Jakab et al., 2002; Okada, 2004, 2020; Lang, 2007; Hoffmann et al., 2009; Kunzelmann, 2015; Jentsch, 2016; Pasantes-Morales, 2016; De Los Heros et al., 2018; Delpire and Gagnon, 2018; Okada et al., 2019; Centeio et al., 2020; Larsen and Hoffmann, 2020; Model et al., 2020).

The kinetics and degree of the actual volume changes critically depend on the water permeability of the PM, which is intrinsically low but greatly enhanced by aquaporins (AQPs) (Day et al., 2014; Kitchen et al., 2015) and also by the efficiency as well as the time of onset of CVR mechanisms. If the regulatory mechanisms [i.e., regulatory volume decrease (RVD) and regulatory volume increase (RVI); see below] have high transport efficiency and/or will start to work quickly, the degree of swelling or shrinkage will deviate from a perfect osmometer-like behavior.

When the actual CV deviates from the given set point, regulatory mechanisms are spurred, aiming at readjusting the original volume. Thus, upon swelling, cells initiate a process termed RVD (cells shrink back toward their original volume), while cell shrinkage is counteracted by RVI (cells swell back toward their original volume). The mechanisms driving the regulatory water fluxes during RVD and RVI are complex and involve rapid release or uptake of ions, amino acids, sugars, or alcohols across the cell membrane but also metabolic changes such as the formation or degradation of macromolecules to pack or unpack abundant osmotically active solutes.

Acute CVR relies on distinct sets of ion channels and transporters. The Na+/K+-ATPase actively pumps K+ into and Na+ out of the cell. K+ permeating through K+ channels generates a negative PM potential ΨPM and thus creates the driving force for the cellular exit of anions such as Cl– and HCO3–. Canonically, during RVD, volume-sensitive K+ and anion channels, KCl cotransport, or parallel activation of K+/H+ exchange and Cl–/HCO3– exchange is activated, while during RVI, Na+/H+ exchangers (NHEs) and Na+/K+/2Cl– cotransporters (NKCCs) in parallel to Cl–/HCO3– exchange or Na+ channels are activated to release or take up ions and osmotically obliged water through AQPs. Thus, RVD is mainly accomplished via cellular exit of K+, Cl–, and HCO3–, whereas RVI is achieved by uptake of Na+ and Cl–. Frequently, RVD mechanisms are inhibited during RVI and vice versa.

Furthermore, shrunken cells can accumulate organic osmolytes such as amino acids, myoinositol, betaine, and taurine either by synthesis or by Na+-coupled uptake of sorbitol, glycerophosphorylcholine, and monomeric amino acids. These osmolytes are then released upon cell swelling. Though inhibition of the Na+/K+-ATPase leads to cell swelling at least in some cells (Alvarez-Leefmans et al., 1992), interestingly, in certain cell types, CVR can also be performed by formation and exocytosis of vesicles even when the Na+/K+-ATPase is inhibited (Russo et al., 2015).

Cell volume also greatly affects macromolecular crowding, i.e., the concentration of macromolecules (mainly proteins and nucleic acids) within the cell and hence their biological activities, which in turn has widespread consequences for cellular functions, including CVR itself (Model et al., 2020). Macromolecular crowding also induces liquid–liquid phase separation as part of the cellular osmosensing system (Ishihara et al., 2021; Watanabe et al., 2021).

As mentioned above, in myoblasts, an acute decrease of PM tension induces macropinocytosis. This was established by hypotonic swelling (stretching the PM and inducing RVD) of the cells followed by returning to isosmotic conditions (inducing cell shrinkage and PM relaxation) (Loh et al., 2019).

Both PIPs and IPs are involved in CVR. As shown in Figure 3, PI(4,5)P2 is metabolized to Ins(1,4,5)P3 and further to the various inositol (poly)phosphates (Hatch and York, 2010). Prominently, Ins(1,4,5)P3 binds to its receptor on internal Ca2+ stores like the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and triggers the release of Ca2+ into the cytosol (Berridge, 2009). Given the plentitude of cellular functions governed by Ca2+i and the numerous components of CVR dependent on it, Ins(1,4,5)P3 is crucial to it. Notably, the levels of IPs are altered in Ras-transformed cells (Fleischman et al., 1986; Maly et al., 1995; Ritter et al., 1997a). Besides, other inositol (poly)phosphates are activated or inhibited by anisotonicity and/or changes in CV (Fleischman et al., 1986; Lang et al., 1998; Jakab et al., 2002; Pesesse et al., 2004; Hoffmann et al., 2009; Wundenberg and Mayr, 2012; Lee et al., 2020).

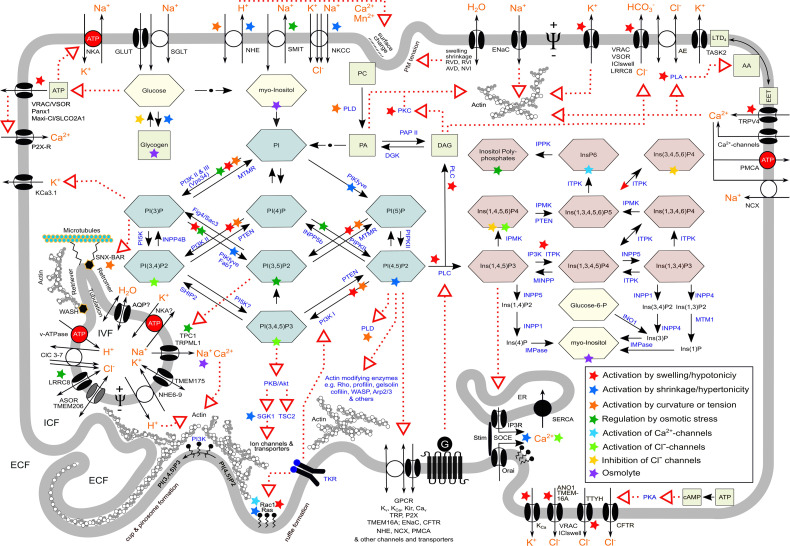

FIGURE 3.

Synopsis of various aspects in macropinocytosis and ion transport in cell volume regulation and vesicular volume regulation, which are also relevant in methuosis. Red dotted arrows indicate action/s on target/s; black arrows indicate metabolic conversion; green combs, phosphoinositides; red combs, inositolphosphates; yellow combs, sugars; green squares, important metabolites; orange letters, ion(s); blue letters, enzymes; ECF, extracellular fluid; ICF, intracellular fluid; IVF, intravesicular fluid; G, heterotrimeric G protein; TKR, tyrosine kinase receptor; NKA, Na+/K+-ATPase; SOCE, store-operated Ca2+ entry; Ψ, transmembrane electrical potential difference. For the meaning of colored asterisks, see insert in the right lower part. For details, nomenclature, and further abbreviations, see text and list of abbreviations.

In programmed CD, cell shrinkage is characteristic (though not universal) of apoptosis and in its initial phase accomplished by RVD-like cellular exit of ions, termed apoptotic volume decrease (AVD). In contrast, cell swelling is characteristic of necrosis and ischemic cell death/onkosis (derived from the Greek word óγκoς, i.e., tumor/swelling Von Recklinghausen, 1910; Majno and Joris, 1995; Weerasinghe and Buja, 2012), termed necrotic volume increase (NVI) (Okada et al., 2001; Orlov and Hamet, 2004; Lang and Hoffmann, 2012, 2013a,b; Orlov et al., 2013; Bortner and Cidlowski, 2014, 2020; Model, 2014; Okada, 2020), and related modes of CD such as secondary necrosis, pyroptosis, or ferroptosis (Zong and Thompson, 2006; D’Arcy, 2019; Nirmala and Lopus, 2020; Riegman et al., 2020). In methousis, not only is cell shrinkage absent but cells actually are swollen (Overmeyer et al., 2008), such as seen in cells expressing an activated form of the H-RasG12V oncoprotein (see below) (Maltese and Overmeyer, 2014; Alonso-Curbelo et al., 2015). This may be related to altered ion transport in cells expressing the H-Ras oncogene.

The set point of a given cell for regulation of its volume is not a fixed constant but may change intrinsically to adjust the CV to altered functional needs. For instance, proliferating cells have to gain volume prior to mitosis, and hence, the set point for volume regulation varies in a cell cycle-dependent manner (Lang et al., 1992a, 2007; Doroshenko et al., 2001; Chen et al., 2002; Klausen et al., 2007; Pedersen et al., 2013). Expression of H-RasG12V in NIH 3T3 fibroblasts leads to an upshift of the set point for CVR, i.e., the cells swell (Lang et al., 1992a). This is related to alterations of cellular metabolism, ion transport, and structural remodeling. Such cells proliferate independently of growth factors and have altered PI metabolism (Fleischman et al., 1986; Maly et al., 1995), stimulated Ca2+ influx (Maly et al., 1995; Ritter et al., 1997b), and increased intracellular pH (pHi) due to activation of NHE (Maly et al., 1989; Ritter et al., 1997b) and Na+, K+, 2C1– cotransport (NKCC1) (Lang et al., 1992a). Furthermore, mitogens, like serum or bradykinin, cause pulsatile release of Ca2+ from internal stores and activation of a store-operated calcium entry (SOCE), which leads to oscillations of ΨPM via Ca2+-activated K+ channels, NHE activation, and actin depolymerization (Lang et al., 1992b; Dartsch et al., 1994b, 1995; Ritter et al., 1997b). In NIH 3T3 fibroblasts that do not express the H-Ras oncogene, bradykinin causes a single transient hyperpolarization, is without effect on actin stress fibers, and leads to cell shrinkage, unless actin is depolymerized (Lang et al., 1992b) (for review, see Ritter and Woll, 1996). The H-Ras-induced ΨPM oscillations are stimulated by hypertonic cell shrinkage (Ritter et al., 1993) presumably via fostering physical apposition and hence interaction of STIM and Orai, which accomplish SOCE (Lang et al., 2018). In line with that, SOCE has been shown to be inhibited by cell swelling (Liu et al., 2010). Furthermore, SOCE is stimulated by hypertonicity via NFAT5 (TonEBP) (Sahu et al., 2017) and SGK1 (Lang et al., 2018). Oncogenic K-RasG13D has been shown to suppress SOCE by altered expression of STIM1 in colorectal cancer cells (Huang and Rane, 1993; Pierro et al., 2018). Interestingly, fibroblastic L cells also display spontaneous oscillations of the cell membrane potential driven by oscillations of Ca2+i and concomitant K+ channel activation. These oscillations are modulated by low- and high-density lipoproteins in parallel with Ca2+-dependent stimulation of their pinocytosis (Tsuchiya et al., 1981; Rane, 1991; Huang and Rane, 1993). Oncogenic H-Ras also activates volume-regulated anion channels (VRACs) (Schneider et al., 2008). An inverse relationship between CV and cell number has been described for T24H-Ras (H-RasG12V) bearing Rat1 and M1 fibroblasts (Kunzschughart et al., 1995).

Water, Ions, and Their Channels and Transporters in Pinocytosis

Extracellular Ionic Composition, Osmolarity, and Extracellular pH

The ionic composition of the extracellular fluid affects pinocytosis by modulating the surface charge of the cell membrane and the cell membrane potential. Electrostatic interactions with the [normally negative (Cevc, 1990)] outer surface charge of a cell and/or the presence of positive charges in macromolecules play an important role in the induction of pinocytosis. In Amoeba proteus, monovalent cations induce pinocytosis in the order Cs+>K+>Na+>Li+, while divalent cations are less effective. Critically, Ca2+ and Mn2+ reduce the sensitivity of monovalent cations but are themselves without effects on pinocytosis (Stockem, 1966; Josefsson, 1968; Josefsson et al., 1975). Furthermore, the initial binding of pinocytosis inducers to the outer cell surface promotes displacement of surface-associated Ca2+ ions and induces changes in various membrane parameters, such as increased membrane conductance and decreased ΨPM along with an increase in plasmalemma hydration. Although pinocytosis in the amoeba can be induced by a great number of different solutes, all of them characteristically possess net positive charges that interact with negative surface charges. Hence, increasing extracellular Na+ displaces most of the exchangeable surface-associated Ca2+ and, therefore, induces pinocytosis. In the yolk sac, cationic macromolecules lead to pinocytosis (Lloyd, 1990). In human corneal epithelial cells, fibroblasts, and human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs), the uptake of an antibody–drug conjugate by macropinocytosis is facilitated by the presence of positive charges or hydrophobic residues on the surface of the macromolecule (Zhao et al., 2018). In contrast, in mammalian macrophages, anionic molecules are better inducers of pinocytosis than neutral or cationic ones (Cohn and Parks, 1967). The uptake of positively charged nanoparticles in colon carcinoma Caco-2 cells is reduced by inhibition of macropinocytosis with 5-(N-ethyl-N-isopropyl)-amiloride (EIPA) and by cholesterol depletion of the PM, whereas these inhibitors have no effect on negatively charged systems (Bannunah et al., 2014). Modulation of the charge for intracellular delivery carriers aims at increasing the efficiency of macropinocytosis of cellular entry for therapeutic nucleic acids to tumor cells (Desai et al., 2019).

Anisotonicity modulates endocytosis in a diversity of cell types. In rat Kupffer cells, hypoosmotic and hyperosmotic conditions have been shown to stimulate and inhibit, respectively, phagocytosis (Warskulat et al., 1996), and in microglial BV-2 cells, preconditioning with hypotonic or hypertonic medium attenuates microsphere uptake (Harl et al., 2013). Hypertonic medium has been shown to disrupt the interaction of caveolae with endosomes. Increased phosphorylation due to phosphatase inhibition induces removal of caveolae from the PM. In the presence of hypertonic medium, this is followed by their redistribution to the center of the cell close to the microtubule-organizing center (Parton et al., 1994).

Only a few studies have addressed the action of anisotonicity on pinocytosis. In Dictyostelium, hyperosmotic conditions lead to a decrease in endocytic activity that can be attributed to cellular acidification (Pintsch et al., 2001), and it can foster the formation of giant vacuoles of pinocytotic origin, which appear to have a function in cellular osmoregulation (see above) (Yuan and Chia, 2001). In murine bone marrow-derived macrophages, hypotonic cell swelling stimulates phagocytosis and pinocytosis, both of which appear to require ClC-3 chloride channels. In this study, the ion channels have on the one hand been suggested to act as volume-activated anion channels in the PM and, on the other hand, shown to support acidification the endosomal compartment (Yan et al., 2014). Hypertonicity inhibits pinocytosis in rat hepatocytes (Synnes et al., 1999). In mouse L929 fibroblasts, cellular uptake of horseradish peroxidase is inhibited in hypertonic sucrose medium, which is reversed to stimulated uptake in the presence 10% PEG 1000 in the medium (Okada and Rechsteiner, 1982; Hughey et al., 2007). Similarly, in murine embryonic fibroblasts, cellular uptake of native proteins via macropinocytosis in hypertonic conditions is stimulated by alkali metal ions (Na+, Rb+, K+, Li+) but not by hypertonicity created by addition of sugars or sugar alcohols. This finding points to the contribution of surface charge in macropinocytosis. Also, hypotonic stress has been demonstrated to greatly enhance receptor-independent retroviral transduction efficiency in NIH 3T3 fibroblasts via stimulated intensive endocytosis (Lee and Peng, 2009).

An interesting concept explaining how extracellular pH elicits such effects is that protonation of the cell surface produces local charge asymmetries across the cell membrane, which induce inward bendings of the lipid bilayer, thus favoring vesicle formation and uptake of macromolecules (Ben-Dov and Korenstein, 2012).

In dendritic cells and bone marrow-derived macrophages, extracellular acidosis improves uptake and presentation of antigens by stimulation of macropinocytosis (Vermeulen et al., 2004; Martínez et al., 2007). This effect is related to acid-sensing ion channels (ASICs) and can be inhibited by their blocker amiloride (Kong et al., 2013). As macropinocytosis depends on phospholipase C (Amyere et al., 2002; Yoshida et al., 2015), its activation by proton-sensing G protein-coupled receptors such as ovarian cancer G protein-coupled receptor 1 (OGR1/GPR68), G protein-coupled receptor 4 (GPR4), T-cell death-associated gene 8 (TDAG8/GPR65), and GPR132/G2A (Seuwen et al., 2006; Alexander et al., 2017; Insel et al., 2020) may also explain the observed stimulatory effect of extracellular acidosis on pinocytosis. Notably, in HEK293 cells expressing mutated wild-type OGR1 or mutated OGR1L74P, receptor internalization, Ca2+i mobilization, and morphological changes observed upon activation of OGR1 by H+ or Ni2+ are severely compromised. This missense mutation of the H+ ion-sensing receptor has been found to cause familial amelogenesis imperfecta (Sato et al., 2020). Experiments with HEK293 cells transfected with active OGR1 receptor or a mutant lacking five histidine residues (H5Phe-OGR1) unraveled that receptor activation by H+ stimulates NHE- and v-ATPase activity only in OGR1- but not in H5Phe-OGR1-transfected cells. Furthermore, the known OGR1 inhibitors Zn2+ and Cu2+ reduce the stimulatory effect (Mohebbi et al., 2012). Given the importance of NHE1 and the v-ATPase for pinocytosis, it is tempting to speculate that OGR1 is a regulator thereof.

By contrast, in pancreatic acinar cells, low extracellular pH selectively impairs apical endocytosis. This is seen in mice lacking cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR), which normally couples endocytosis at the apical PM to HCO3– secretion into the ductal lumen by normally rendering it alkaline. The acidic luminal fluid and impaired endocytosis due to lack of CFTR can be restored by alkalizing it in vitro (Freedman et al., 2001).

Ion Fluxes Drive Gel–Sol Transitions of the Cortical Actin Rim

Reorganization of the submembranous cytoskeleton is an essential step in pinocytosis. The cortical actin network is a major determinant of cell stiffness, and a correlation between stiffness of the actin network and the activity of endocytosis has been demonstrated (Planade et al., 2019). Extracellular K+ and Na+ antagonistically modulate the gel-to-sol transition of the cortical actin cytoskeleton beneath the PM (for review, see Oberleithner et al., 2009; Callies et al., 2011; Oberleithner and De Wardener, 2011; Warnock et al., 2014). Elevations of extracellular Na+ and K+ concentration stiffen and soften, respectively, the submembranous actin cytoskeleton of endothelial cells within minutes (Oberleithner et al., 2009). The Na+-dependent stiffening is mediated by an aldosterone-induced upregulation and activation of epithelial Na+ channels (ENaCs) and, presumably, by downregulation of the endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) activity. Conversely, inhibition of ENaCs upregulates nitric oxide [NO; formerly termed endothelium-derived relaxing factor (EDRF)] production. Depolarizing ΨPM by increasing extracellular K+ concentration, by blocking K+ channels with Ba2+, and by decreasing extracellular Cl– concentration decreases the mechanical stiffness of endothelial cells (Callies et al., 2011). Thus, modulation of the sol–gel transition of the actin cytoskeleton is thought to be due to the G-actin-dependent activation of eNOS (Fels et al., 2010).

It has to be mentioned that hypotonic swelling of endothelial cells was shown to cause stiffening of the PM due to an increase in cellular hydrostatic pressure rather than to disruption of the submembranous actin network. In this study, a change in membrane tension was not observed upon osmotic swelling, and depolymerization of F-actin did not abrogate swelling-induced stiffening of the PM (Ayee et al., 2018).

Cell Volume, Nitric Oxide, and the Cytoskeleton May Act Together in Regulating Endocytosis

In endothelial cells, a reciprocal regulatory relationship between eNOS and caveolin-1 (Cav-1) has been found, whereby Cav-1 and eNOS regulate the function of each other. On the one hand, Cav-1 stabilizes eNOS expression and regulates its activity, and eNOS-derived NO promotes caveolae-mediated endocytosis of albumin and insulin; on the other hand, a sustained NO production and persistent S-nitrosylation of Cav-1 lead to its ubiquitination and degradation (Chen et al., 2018).

Besides eNOS, also an association of inducible NO synthase (iNOS) with the submembranous actin cytoskeleton and intracytoplasmic vesicles in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)- and interferon gamma (INFγ)-stimulated macrophages and other cells was shown (Webb et al., 2001; Su et al., 2005).

Nitric oxide is a regulator of endocytosis, phagocytosis, and vesicle trafficking (Weinberg, 1998; Chen et al., 2018). For example, NO downregulates endocytosis in rat liver endothelial cells (Martinez et al., 1996) but promotes caveolae-mediated endocytosis as mentioned above (Chen et al., 2018). Macrophages stimulated by the thymic peptide thyαl display enhanced NO levels as well as increased pinocytosis (Shrivastava et al., 2004), as do amphotericin B-stimulated microglial cells (Kawabe et al., 2017). Conversely, mouse peritoneal macrophages stimulated with activin A display both reduced NO and pinocytosis (Zhou et al., 2009). Also, macropinocytosis of drugs may promote enhancement of iNOS expression, as exemplified for the chemotherapeutic nab-paclitaxel, which synergizes to this end with INFγ (Cullis et al., 2017).

Recently, it has been shown that NO regulates endocytic vesicle budding by S-nitrosylation of dynamin—a GTPase that regulates vesicle budding from the PM—and increases its enzymatic activity in response to NO (Wang et al., 2006). Dynamin is bound by NOS trafficking inducer (NOSTRIN), an eNOS-interacting adaptor protein, which forms a complex with Cav-1 and eNOS, and colocalizes with WASP and actin to promote its polymerization. It thus regulates caveolar endocytosis and eNOS internalization (Schilling et al., 2006; Su, 2014).

Nitric oxide/EDRF is also released in response to changes in extracellular osmolarity, which also greatly affect the cortical actin organization. This is also relevant in apoptosis, where NO metabolism, actin organization, and CV-regulatory ion transport are linked together (Bortner, 2005).

Nitric oxide release in response to hypertonicity occurs in vessels and endothelial cells (Steenbergen and Bohlen, 1993; Vacca et al., 1996; Zani and Bohlen, 2005). Hypertonicity downregulates eNOS in human aortic endothelial cells (HAECs), an effect that is mediated by activation of AQP1 and NHE-1, and which involves PKCβ-mediated intracellular signaling (Madonna et al., 2010). In insulin-treated HAECs, hypertonicity, established by high glucose or mannitol, downregulates the PI3K/Akt/mTOR/eNOS pathway and impairs their ability to respond to insulin. This may contribute to insulin resistance. The mechanism involves AQP1 and the transcription factor Ton/EBP (NFAT5) for osmosensing, and the effect can be reversed by silencing the transcription of these proteins (Madonna et al., 2020).

Hypotonic swelling has been shown to promote the release of NO and reactive nitrogen oxide species in various cells (Kimura et al., 2000; Haussinger and Schliess, 2005; Takeda-Nakazawa et al., 2007; Kruczek et al., 2009; Gonano et al., 2014) and to augment LPS-triggered iNOS expression in RAW 264.7 macrophages (Warskulat et al., 1998). Recently, it has been shown that in HUVECs, VRAC/SWELL1/LRRC8A mediates endothelial cell alignment via stretch-dependent Akt-eNOS signaling and formation of a signaling complex made up by Grb2, Cav-1, and eNOS (Alghanem et al., 2021).

While osmotic shrinkage in general is associated with an increase in actin polymerization, cell swelling leads to its depolymerization, though both with exceptions (Hoffmann et al., 2009).

Hypertonic shrinkage fosters the translocation of the actin-binding protein cortactin to the cortical actin net, where it interacts with the Arp2/3 complex, WASP, dynamin, and myosin light-chain kinase (for review, see Pedersen et al., 2001; Hoffmann et al., 2009). Cortactin stabilizes microfilament assembly at the cell periphery, is recruited to PM ruffles, and participates in macropinocytosis (Mettlen et al., 2006). In human-induced pluripotent stem cells, hyperosmolarity, created by high glucose or mannitol, upregulates AQP1 and induces cytoskeletal remodeling with increased ratios of F-actin to G-actin, effects that could be by reversed siRNA-mediated inhibition of AQP1 expression (Madonna et al., 2014).

Cell swelling can lead to reorganization of intermediate filaments (Dartsch et al., 1994a; Li J. et al., 2019). In Cos-7 fibroblast-like cells, hypotonicity causes a rapid calcium/calpain-dependent cleavage of the intermediate filament vimentin, whereby hypotonicity leads to the generation of IP3 by hydrolysis of PI(4,5)P2 and Ca2+ release from the ER (Pan et al., 2019). Vimentin in turn is involved in the regulation of vesicular trafficking (Margiotta and Bucci, 2016) and was also shown to be modulated by NO (Sripathi et al., 2012).

Na+/H+ Exchangers and Pinosome Formation

A distinctive hallmark to distinguish clathrin-dependent endocytosis from clathrin-independent macropinocytosis is the sensitivity of the latter to inhibitors of NHEs such as amiloride, EIPA, or HOE-694 (West et al., 1989; Koivusalo et al., 2010; Canton, 2018; Lin et al., 2020). Besides NHEs, amiloride also directly inhibits ion channels of the epithelial sodium channel/degenerin family, such as ENaC and ASIC1 (Kellenberger and Schild, 2002; Qadri et al., 2010) and growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase activity (Davis and Czech, 1985). Moreover, amiloride is a weak permeant base that can accumulate in acidic vesicles, thus, eventually dissipating the H+-gradient driving cation exchange, and thereby inhibiting pinocytosis (Dubinsky and Frizzell, 1983; Bakker-Grunwald et al., 1986). Of note, EIPA does not inhibit a newly described form of CD, which is induced by fenretinide, which is similar to methuosis characterized by hyperstimulated macropinocytosis and massive vacuolization (Brack et al., 2020).

Na+/H+ exchangers, which are members of the solute carrier (SLC) 9 family, are electroneutral transporters that exchange Na+ for H+ across membranes (Pedersen and Counillon, 2019). The NHE1 isoform is expressed almost ubiquitously and regulates cellular and organelle pH, motility, phagocytosis, proliferation, as well as cell survival and CD (Orlowski and Grinstein, 2011; Pedersen and Counillon, 2019). Cell shrinkage is a strong stimulator of NHE1 activity and serves for RVI (see above) (Ritter et al., 2001; Baumgartner et al., 2004; Orlowski and Grinstein, 2011; Pedersen and Counillon, 2019). NHE1 is activated by a drop in pHi, a broad diversity of PM receptors, such as tyrosine kinase receptors, G-protein-coupled receptors or integrin receptors, and it is regulated by second messengers, asymmetric membrane tensions, and phosphoinositides, such as PI(4,5)P2 (Orlowski and Grinstein, 2011; Pang et al., 2012; Pedersen and Counillon, 2019). In proximal tubular cells, NHE1 is activated by PI(4,5)P2 and inhibited by PI(3,4,5)P3 (Abu Jawdeh et al., 2011; Pang et al., 2012). NHE1-borne changes in pHi may also be confined to distinct subcellular domains or compartments. Such subcellular compartments are the lammelipodia formed during cell spreading and migration, pseudopodia in phagocytosis, ruffles and the cup wall formation in macropinocytosis. In all of these processes, NHE1 is also involved in cytoskeletal rearrangement (Schwab and Stock, 2014; Pedersen and Counillon, 2019). NHE1 is connected to actin via ezrin/radixin/moesin (ERM) family of actin-binding proteins. Migrating cells undergo cell polarity-dependent subcellular volume changes. Repetitive cycles of protrusion at the leading edge (lamellipodium) are followed by retraction of the cell’s rear, i.e., the trailing edge. Waves of local water movement across the PM locally increase and decrease CV during the protrusion and retraction of the lamellipodium, respectively. Hence, cell migration requires an alternating cycle of subcellular RVI at the leading edge and RVD at the trailing edge of the cell. Most of the ion transporters known to participate in CVR are also involved in the regulation of cell migration. As part of the RVI transporters, NHE1 is confined to the lamellipodium, where it also serves for local extracellular acidification (Lang et al., 1998; Schneider et al., 2000; Loitto et al., 2002, 2009; Jakab and Ritter, 2006; Hoffmann et al., 2009; Schwab et al., 2012; Stock et al., 2013). This is also given in breast cancer cell invadopodia, where NHE1 is allosterically regulated by NaV1.5 Na+ channels (Brisson et al., 2012, 2013). In T47D human breast cancer cells, NHE1 colocalizes with Akt and ERK in prolactin-induced ruffles (Pedraz-Cuesta et al., 2016).

Although inhibition of macropinocytosis by NHE inhibitors is a fingerprint feature of macropinocytosis, the molecular mechanisms how NHEs contribute to macropinocytosis are barely known. Interestingly, activation of the small GTPases, Rac1/Cdc42, and consequently actin polymerization and, thus, ruffle formation are sensitive to submembranous pH (pHsm). Submembranous acidification due to inhibition of NHE1 by amiloride prevents Rac1/Cdc42 activation and suppresses actin polymerization (Koivusalo et al., 2010). Moreover, NHE1 inhibition favors the accumulation of cytosolic H+, which neutralizes the negative charges on the inner leaflet of the PM. Thus the interaction of the negatively charged headgroups of phosphoinositides and the polybasic motifs in Rac and Cdc42 as well as the SCAR/WAVE complex and WASP is hampered. This also explains the inhibitory effect of NHE1 blockers on macropinocytosis (Marques et al., 2017). Therefore, amiloride might not directly inhibit macropinocytosis but cause submembranous accumulation of metabolically generated H+ in thin lamellipodium-like membrane extensions by inhibition of H+ efflux. Given the small volume of these structures, only a few H+ will change pHsm and, consequently, the state of actin polymerization. However, in HeLa cells, oncogenic Ras-induced macropinocytosis does not require a decrease in pHsm (Ramirez et al., 2019).

Notably, in mice bearing xenograft tumors derived from oncogenic K-Ras bearing MIA PaCa-2 cells, intratumoral macropinocytosis and tumor growth are suppressed by treatment of the animals with EIPA, which is, however, effective only in tumors with high but not low macropinocytic activity (Commisso et al., 2013; Recouvreux and Commisso, 2017).

The ionophoric NHE monensin induces vesicular swelling and the formation of giant multivesicular bodies (MVBs) (Stein and Sussman, 1986; Savina et al., 2003) and release of exosomes, which can be inhibited by the NHE inhibitor dimethyl amiloride (DMA) (Chalmin et al., 2010; Pironti et al., 2015). Moreover, deletion of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae NHE, Nhx1, disrupts the fusogenicity of the MVB in a manner dependent on pH and monovalent cation gradients (Karim and Brett, 2018).

The Ion Composition in Macropinosomes and Endolysosomal Vesicles

After pinching off, the nascent macropinosome has entrapped extracellular fluid that equals the extracellular fluid in the intimate vicinity of its formation site. Traveling along the endolysosomal pathway, its ionic composition is modified to render the vesicular volume, shape, and fluid suitable for processing its cargo, as shown in Table 1 (Scott and Gruenberg, 2011; Freeman and Grinstein, 2018; Chadwick et al., 2021b).

Water Permeability, Aquaporins, and Osmolarity

The permeabilities of the PM and vesicular membranes for water play crucial roles in pinocytosis. The importance of PM AQPs for macropinocytosis is seen in dendritic cells where they are needed as essential elements of a CV control mechanism necessary to concentrate the macrosolutes and present antigens (De Baey and Lanzavecchia, 2000; Hara-Chikuma et al., 2011; Kitchen et al., 2015).

Macropinosomes shrink along their cellular route by moving ions and osmotically obliged water out of its lumen into the cytosol (Freeman and Grinstein, 2018; Chadwick et al., 2021b). Despite the dramatic decrease in pinosome volume, the water permeation pathway is not characterized yet. Studies on osmotic water permeability (Pf) indicate that Pf values higher than 0.01 cm/s indicate water flux through channels (Verkman et al., 1996), Pf values in the range from 0.003 to 0.005 cm/s designate membranes lacking water channels, and Pf values between 0.0001 and 0.005 cm/s characterize pure phospholipid bilayers (Fettiplace and Haydon, 1980; Echevarria and Verkman, 1992; Olbrich et al., 2000). These values could be used to evaluate the presence or absence of water channels in endosomes.

Clathrin-coated vesicles from bovine brain that lack water channels have a low Pf of ∼0.001 cm/s and retain this value after stripping off the coat. Vesicles prepared from bovine renal cortex and inner medulla revealed two populations: one containing water channels with high (0.02 cm/s) and one lacking them with low values compared to brain-derived vesicles (Verkman et al., 1989). Vasopressin-induced endosomes of rat kidney papilla and toad bladder endocytic vesicles have Pf values of 0.03 and >0.1 cm/s, respectively, whereas isolated toad bladder granules have a Pf value as low as 0.0005 cm/s (Verkman and Masur, 1988; Verkman et al., 1988; Shi and Verkman, 1989; Verkman, 1989).

Only a few studies have investigated Pf of pinosomes and lysosomes. In J774 macrophages, the Pf of the PM is in the range of ∼0.004–0.009 cm/s (Fischbarg et al., 1989; Ye et al., 1989; Echevarria and Verkman, 1992). The water permeability of the macropinosome membrane of J774.A1 cells increases non-linearly from ∼0.001 cm/s 3 min after formation to ∼0.005 cm/s after 25 min of formation (Chaurra-Arboleda, 2009). The lysosomal Pf of CHO-K1 cells is in the same range (Chaurra et al., 2011). In J774.A1 cells, Pf shows pH dependency. It decreases from ∼0.007 to 0.0009 cm/s following lysosomal alkalinization with NH4Cl (pHlys 6.5–6.8) and to 0.0001 cm/s after inhibition of the v-ATPase (pHlys ∼7.0). These values are similar to those in early macropinosomes, which have a pH of ∼6.7 (Chaurra-Arboleda, 2009). Taken together, the low Pf values of J774 macrophages indicate the absence of AQPs in the endolysosomal compartment.

Despite these specific observations, the role of AQPs in the endolysosomal compartment is poorly investigated, while their importance in volume regulation of secretory vesicles is well documented (Cho and Jena, 2006; Sugiya et al., 2008; Jena, 2020). In toad urinary bladder endosomes, AQP-TB has been shown to be present (Siner et al., 1996), and incorporation of PM-derived AQP2 into endosomes is well known for AVP-stimulated renal collecting duct principal cells (Shi and Verkman, 1989; Verkman, 2005). In astrocytes, AQP4-laden vesicles may fuse with the PM upon cell swelling (Potokar et al., 2013; Vardjan et al., 2015). AQP6 was shown to be present in intracellular vesicles of acid-secreting intercalated cells of the renal collecting duct where it colocalizes with the H+-ATPase and serves also as an anion channel (Yasui et al., 1999; King et al., 2004). Lack of AQP11 causes defective endosomal pH regulation, as seen in mice devoid of AQP11. This is accompanied by the appearance of huge vacuoles in the renal proximal tubules and polycystic kidneys (Ishibashi et al., 2009).

An example for the function of organellar AQPs in VVR and CVR is evident in Trypanosoma cruzi, as briefly described below.

Alternatively to AQPs, water permeation through transporters and ion channels has been described for glucose transporters (Loike et al., 1993; Fischbarg and Vera, 1995), NKCC1, KCC, SGLT1, and CFTR (Hamann et al., 2010; Zeuthen, 2010; Zeuthen and Macaulay, 2012; Huang et al., 2017). Eventually, these transporters or ion channels could be used in pinosomes for water efflux as well.

By whatever way, as upon hypertonic cell shrinkage also vesicles rapidly shrink, it can be deduced that the intrinsic water permeability is sufficiently high to allow for timely vesicular volume changes during resolution of macropinosomes (Freeman and Grinstein, 2018). Using fluorescence enhancement of Lucifer yellow dextran by deuterated water, Li et al. (2020) have recently demonstrated that lysosomes rapidly swell in response to a hypoosmotic challenge, indicating that there is substantial water influx into the lumen of lysosomes soon after water penetration across the PM, again indicating that the intrinsic water permeability of these organelles is high.

Vesicular pH Regulation and Ions in Pinosome Maturation

The pH of the ingested fluid of nascent pinosomes resembles that of the extracellular fluid, which is under physiological conditions (7.4). During trafficking, vesicular pH (pHves) gradually decreases to the value prevailing in lysosomes, i.e., 4.5–5.0. pHves regulates enzyme activities and enables oxidation reactions, the release of internalized receptors from their ligands and their recycling back to the PM, movement and assembly of organellar surface coat proteins, vesicle maturation, as well as membrane fusion processes (Demaurex, 2002; Ohgaki et al., 2011).

Vacuolar ATPase

The acidification is primarily achieved by insertion of the v-ATPase. The v-ATPase is an evolutionarily highly conserved primary active H+ transporter. As already outlined, it can be found both in the PM and in various intracellular organelles. Structurally, it comprises a multiprotein complex that forms two distinct domains, i.e., the pore-forming transmembrane VO domain and the cytosolic V1 domain. The latter hydrolyzes ATP to drive H+ movement. This creates the electrochemical H+ gradient across the membrane, thereby driving secondary active transport processes, which act together for proper adjustment of pHves and vesicular ion and osmolyte composition. In particular, parallel to H+ pumping, ion channels and transporters move Cl–, H+, and other cations to establish an electrical shut aiming for electroneutrality of the net charge transfer. Otherwise, the acidification would be limited by the transmembrane potential Ψves, which is set up by the v-ATPase itself (Demaurex, 2002; Steinberg et al., 2010; Koivusalo et al., 2011; Xiong and Zhu, 2016; Freeman and Grinstein, 2018; Jentsch and Pusch, 2018; Sterea et al., 2018; Li P. et al., 2019; Freeman et al., 2020; Chadwick et al., 2021a). pHves is stabilized by the buffering capacity of the vesicle content (∼60 mM/pH at pH 4.5–5) (Weisz, 2003; Steinberg et al., 2010).

In addition, the v-ATPase also serves as a protein interaction hub. For the proper sorting and targeting of the vesicles, small GTPases are recruited to their membranes in an acidification-dependent manner. The v-ATPase itself is able to associate with some of them and with other regulatory proteins. Thus, the v-ATPase seems not only to serve for creating the acidic pHves but also to sense it and to transmit this information to its cytoplasmic domain, thus enabling trafficking molecules to bind and perform their targeting functions. The v-ATPase is also involved in signaling pathways for the regulation of macropinocytosis, as outlined throughout this review. Its dysfunction may play critical roles in various diseases including diabetes, cancer, neurodegeneration, osteopetrosis, skin disorders, or renal tubular acidosis and other pathologies. Furthermore, it is also essential for viral entry into cells (for reviews on v-ATPase, see Nishi and Forgac, 2002; Platt et al., 2012; Maxson and Grinstein, 2014; Rappaport et al., 2016; Kissing et al., 2018; Futai et al., 2019; Collins and Forgac, 2020; Song Q. et al., 2020; Vasanthakumar and Rubinstein, 2020; Chadwick et al., 2021a, b; Eaton et al., 2021).

Cl– Ions

Within 1 min after internalization, the luminal Cl– concentration in endosomes/macropinosomes drops from ∼120–150 mM to ∼20 mM (Sonawane et al., 2002). This decrease is insensitive to Cl– channel inhibition and can be attributed to Cl– expulsion by an interior negative Donnan potential (Ohshima and Ohki, 1985; Sonawane and Verkman, 2003; Hryciw et al., 2012). During maturation, the vesicular Cl– concentration increases again up to ∼130 mM in lysosomes (Saha et al., 2015). The Cl– accumulation of late endosomes can be suppressed by inhibition of the v-ATPase and restored by the K+ ionophore valinomycin. Also, replacement of Cl– by gluconate and Cl– channel inhibition slow endosomal acidification. Thus, Cl– is an important counter ion accompanying endosomal acidification (Sonawane and Verkman, 2003) (for review, see Faundez and Hartzell, 2004; Stauber and Jentsch, 2013). The accumulation of lysosomal Cl– appears to be important for the adjustment of the lysosomal volume and the activity of proteases. Reduced lysosomal Cl– concentrations may lead to lysosomal storage diseases, e.g., Gaucher’s disease (OMIM entries 230800, 230900, 231000) or Nieman–Pick’s disease (OMIN entries 257200, 607616, 257220, 607625) (Cigić and Pain, 1999; Platt et al., 2012, 2018; Stauber and Jentsch, 2013; Rappaport et al., 2016; Chakraborty et al., 2017; Astaburuaga et al., 2019).

The Cl– channels and transporters expressed in intracellular organelles include the ClC family members ClC-3 through 7, chloride intracellular channels (CLICs), CFTR, AQP6, transmembrane proteins (TMEM)16C–G/anoctamin (ANO) 3–7, bestrophin-1, Golgi pH regulator (GPHR) (reviewed in Stauber et al., 2012; Stauber and Jentsch, 2013), Tweety homolog 1 (Ttyh1) proteins (Wiernasz et al., 2014), LRRC8 (Li et al., 2020), and TMEM206 (Osei-Owusu et al., 2021).

The ClC-3 to 7 transporters are confined to distinct endolysosomal compartments with partially overlapping appearance (Jentsch and Pusch, 2018). They are electrogenic outwardly rectifying 2Cl–/H+ exchangers working in parallel with the v-ATPase. As per exchange cycle, two Cl– enter and one H+ leaves the vesicle, three negative charges accumulate in the vesicle. To maintain electroneutrality, three H+ are pumped in, one of which leaves the vesicle again via the 2Cl–/H+ exchanger, thus leading to a net uptake of two H+ (Guzman et al., 2013; Jentsch and Pusch, 2018). This proposed mechanism allows a more efficient H+ and Cl– accumulation, as it generates a more inside-negative Ψves than an ohmic Cl– conductance could do. Yet, this mechanism may be restricted to ClC-5 (Zifarelli, 2015). However, Ψves is generally thought to be negative (i.e., positive in the lumen) due to the rheogenic v-ATPase. The reason for this discrepancy is still elusive (Weinert et al., 2010) (reviewed in Jentsch, 2007; Stauber et al., 2012; Stauber and Jentsch, 2013; Jentsch and Pusch, 2018). Dysfunctional ClC exchangers may lead to a broad variety of symptoms and disorders including neurodegeneration and other neuropathies, proteinuria and kidney stones, osteopetrosis, albinism, and lysosomal storage diseases (Jentsch and Pusch, 2018; Nicoli et al., 2019; Schwappach, 2020; Bose et al., 2021). Overexpression of ClC-3 or gain-of-function mutations of ClC-6 or ClC-7/Ostm1 leads to swelling of late endosomes and lysosomes (Li et al., 2002; Nicoli et al., 2019; Polovitskaya et al., 2020). In B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma cells, the PIKFyfe inhibitor apilimod leads to CD by formation of giant vacuoles and disruption of endolysosomal function, an effect that requires functional ClC-7/Ostm1 transporters (Gayle et al., 2017). In Hela and NIH3T3 cells, a short natural ClC3 splice variant (Clc3s) has been shown to lead to the formation of large vacuoles (Wu et al., 2016), and in Chinese hamster ovary CHO-K1 or human hepatoma Huh-7 cells, the volume of such vesicles is governed by their Cl– concentration (Li et al., 2002).

Endothelial cells lacking CLIC4 display defective endothelial cell tubulogenesis and impaired acidification of large intracellular vesicles, while lysosomes are unaffected (Ulmasov et al., 2009).