Abstract

Loneliness is a mechanism through which marital quality relates to older adults’ mental health. Links between marital quality, loneliness, and depressive symptoms, however, are often examined independent of older adults’ functional health. The current study therefore examines whether associations between marital quality, loneliness, and depressive symptoms are contextually dependent on individuals’ own (or their spouse’s) functional limitations, as well as on gender. Data came from couples (N = 1084) who participated in the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), a nationally representative dataset of older adults (age 50+). We utilized data from the 2014 leave-behind psychosocial questionnaire to measure spousal support/strain and loneliness, and interview data from 2014 to measure baseline depressive symptoms and demographic covariates (e.g., race and education). Depressive symptoms in 2016 served as the focal outcome variable. Findings from a series of path models estimated in MPLUS indicated that loneliness is a mechanism through which spousal support predicts older adults’ depressive symptoms. Such linkages, however, were dependent on individuals’ own functional limitations and gender. For functionally limited males in particular, spousal support was shown to reduce depressive symptoms insofar as it was associated with lower levels of loneliness; otherwise, it was associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms. Such findings reinforce the importance of taking a contextualized approach when examining associations between support and emotional well-being later in life.

Older adults suffering from depressive symptoms face a decreased quality of life and an increased risk of health problems and mortality (Blazer, 2003). There is a strong social component to older adults’ experience of depressive symptoms. The marital relationship in particular has been deemed an important relationship (Antonucci, Lansford, & Akiyama, 2001). Controlling for initial depressive symptoms, continuously married individuals have been shown to be significantly less depressed than their counterparts who were either continuously divorced/separated or continuously unmarried, as well as those who became divorced/separated (Kim & McKenry, 2002). Spouses, however, can act as sources of both support and strain, and both uniquely influence older adults’ depressive symptoms (Antonucci et al., 2001; Rook, 2015). The purpose of the current study is to examine links between marital quality (i.e., spousal support and strain) and depressive symptoms within a nationally representative sample of community-dwelling older adults and their cohabiting intimate partners. Furthermore, in an effort to examine links between marital quality and depressive symptoms that better reflect normative later-life circumstances, we also take into account several theoretically-guided contextual factors that may impede older adults’ ability to prioritize emotional well-being: threats to social belonging (loneliness), individuals’ own (or their spouse’s) chronic health stressors (specifically difficulty completing activities of daily living), and gender.

Theoretical Framework

Older adults typically rely on close social ties as they navigate the multitude of stressors that come with growing older (e.g., declining physical health; Cornwell, Laumann, & Schumm, 2008). In particular, married adults often turn to their spouse both to share positive events and to seek support in times of stress (Antonucci et al., 2001). Over time, these benefits accumulate to promote mental health and well-being. At the same time, many spouses have also accumulated years of strain (e.g., criticism), which can independently—and adversely—affect older adults’ depressive symptoms (Antonucci et al., 2001; Rook, 2015). Such findings align with the Marital Discord Model of Depression, which suggests that marital discord, including both higher levels of strain and lower levels of support from spouses, predicts the onset or maintenance of depressive symptoms (Beach, Sandeen, & O’Leary, 1990).

In general, however, older adults’ marriages are characterized by relatively low levels of marital discord (Smith & Baron, 2016). Compared to their younger counterparts, older adults may be less emotionally reactive to marital discord when it does occur, perhaps as a result of better emotion-regulation abilities (Piazza, Charles, & Almeida, 2007). Marital discord may also be lower among married older adults because marriages characterized by low levels of support and/or high levels of strain might have dissolved prior to late adulthood. Furthermore, when it does occur, adverse effects of marital discord on depressive symptoms may be dampened later in life. On the other hand, older adults are often tasked with managing a host of unavoidable circumstances that may impede their ability to maximize their emotional well-being. In fact, the Strength and Vulnerability Integration (SAVI) Model (Charles, 2010) points to threats to social belonging (such as loneliness) and chronic health stressors as two such unavoidable circumstances, both of which increase in prevalence with age. In the sections that follow, we discuss the role that loneliness and health stressors (i.e., functional limitations) each may play in the associations between spousal support/strain and depressive symptoms.

Loneliness as a Mechanism

Loneliness, or perceived social isolation, is a major risk factor for depressive symptoms among older adults (Cacioppo, Hawkley, & Thisted, 2010). Although it is not surprising that bereaved adults who relied on their spouse for a sense of belonging are especially lonely later in life (Charles, 2010), even married older adults experience loneliness if their marriages are of low quality. Older adults who report receiving lower levels of support from their spouse report higher levels of loneliness, even after accounting for support received from other people (de Jong Gierveld, Broese van Groenou, Hoogendoorn, & Smit, 2009). Furthermore, whereas support from one’s spouse is associated with lower levels of loneliness, strain from one’s spouse is associated with higher levels (Chen & Feeley, 2014). Loneliness therefore serves as a plausible mechanism through which marital discord predicts older adults’ depressive symptoms.

Several studies have found that loneliness mediates associations between markers of relationship quality and well-being among community-dwelling older adults. Utilizing data from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), Chen and Feeley (2014) found that loneliness explains cross-sectional associations between spousal support and life satisfaction, as well as spousal strain and life satisfaction. Similarly, Park et al. (2013) found that, among older Korean Americans, loneliness mediates cross-sectional associations between markers of social engagement and depressive symptoms. Finally, utilizing prospective data, Santini et al. (2016) found that loneliness mediates longitudinal associations between social support/strain from various sources (e.g., spouses and adult children) and depressive symptoms among older men and women in Ireland. Together, these findings highlight the potential for loneliness that stems from poor relationship quality (rather than a simple lack of social relationships) to undermine older adults’ mental health and well-being.

Functional Limitations as a Moderator

Studies that have examined loneliness as a mechanism of links between older adults’ marital quality and well-being (e.g., Chen & Feeley, 2014; Santini et al., 2016) have done so independent of—or controlling for—health stressors, which is the second circumstance outlined in the SAVI model that may pose a threat to older adults’ emotional well-being (Charles, 2010). In fact, there is a robust association between functional limitations (having difficulty completing activities of daily living) and depressive symptoms among community-dwelling older adults (Penninx et al., 1998a). Loneliness may help explain this relationship, as functionally limited men and women over the age of 65 report higher levels of loneliness than those with fewer limitations (Korporaal, Broese van Groenou, & van Tilburg, 2008). Moreover, older adults are lonelier when their spouses are more functionally limited, independent of their own functional limitations. For example, older adults providing care for a spouse report higher levels of both loneliness and depressive symptoms compared to their non-caregiving counterparts (see Lavela & Ather, 2010 for a review). Together, these findings suggest that older adults who are more functionally limited themselves, or who are married to and perhaps caring for a functionally limited spouse, may experience heightened feelings of both loneliness and depressive symptoms.

Functionally limited older adults may also be more vulnerable to the stress of marital discord (Robles, Slatcher, Trombello, & McGinn, 2014). Although older adults may generally be less emotionally reactive to stress, impaired physical health may diminish this developmental advantage (Charles, 2010). In fact, older adults reporting multiple chronic health conditions exhibit emotional reactions to daily stress (i.e., increases in negative affect) that are just as strong as those of their younger counterparts (Piazza et al., 2007). Ties between marital discord and depressive symptoms may therefore be stronger among more functionally limited older adults.

Because functionally limited older adults are also less likely to engage in social activities (in part due to decreased mobility), support—or strain—from their spouses may play a particularly salient role in either lessening—or exacerbating—their loneliness (Warner, Adams, & Anderson, 2018). Older adults in poorer physical health also have fewer social resources, including fewer close friends, which may amplify the central role of support—or strain—from spouses (Burholt & Scharf, 2013). Furthermore, older adults coping with more functional limitations report both more loneliness (Warner & Kelley-Moore, 2012) and depressed affect (Bookwala & Franks, 2005), particularly when they are in less supportive marriages.

Having a functionally limited spouse may also moderate links between marital quality, loneliness, and depressive symptoms later in life. Because spouses typically assume at least some level of caregiving responsibilities for functionally limited older adults, they may be less likely to participate in social activities themselves, and perhaps become more socially isolated from other family members and friends. Marital quality may also look different within a caregiving context. For instance, wives of husbands with more functional limitations report less spousal support and more spousal strain (Wong & Hsieh, 2017). Thus, impaired spousal health can change marital and social roles in ways that may affect older adults’ emotional well-being. On the one hand, spousal functional limitations might cause couples to become closer in a “small social world in which the importance and meaning of the marital bond is reevaluated” (de Jong Gierveld & Broese van Groenou, 2016, p. 62). On the other hand, spousal functional limitations might “hamper the quality of the marital relationship because of a lack of emotional closeness and intimacy, decreased shared activities, and problematic behavior of the disabled spouse” (p. 62). Although depicted as an important contextual factor within which links between marital quality, loneliness, and depressive symptoms likely unfold later in life, little research has evaluated the moderating role of spousal functional limitations on such associations.

Gender Differences

The aforementioned research suggests that older adults who are in poorer physical health—and perhaps even those with a spouse in poorer health—may have fewer social resources outside of marriage, thus rendering marital quality a more salient predictor of well-being (Warner et al., 2018). Because males and females differ in how many social resources they have outside of marriage (McLaughlin, Vagenas, Pachana, Begum, & Dobson, 2010), it may be that spousal support and strain play the most salient role for functionally limited males, as opposed to healthy males and females and functionally limited females. More specifically, McLaughlin et al. found that, even after controlling for marital status and physical health, older women have significantly larger social networks than do older men. However, it is important to note that older women are also more likely to be depressed than are older men (Barry, Allore, Guo, Bruce, & Gill, 2008), perhaps in part due to the potential burden of these social ties (Shaw, Krause, Liang, & Bennett, 2007). Recent research also provides empirical support for the longstanding notion that men gain more from romantic relationships because they rely more exclusively on their partners for support, as opposed to women who also rely on other social ties. More specifically, Stronge, Overall, and Sibley (2019) found that the indirect effect of having a romantic partner on well-being through perceived social support was stronger for males as compared to females. Thus, for men, perceived social support is more centrally tied to—or dependent on—being in a relationship.

There are also gender differences in the indirect effects of social relationships on well-being through loneliness more specifically. For example, Park et al. (2013) found that loneliness that stemmed from living alone was a stronger predictor of men’s depressive symptoms, whereas loneliness that stemmed from a lack of social engagement with friends and relatives was a stronger predictor of women’s depressive symptoms. Similarly, Santini et al. (2016) found that indirect effects of poor relationship quality (i.e., lower spousal support and higher spousal strain) on depressive symptoms through loneliness were significantly stronger for males than females, thus “confirming that men are intrinsically reliant on their spouses for intimacy and support” (p. 66). Thus, compared to men, social engagement outside of marriage seems more important for women in reducing loneliness and, in turn, depressive symptoms, such that the indirect effects of marital quality on depressive symptoms via loneliness may be weaker for women.

On the other hand, caregiving responsibilities associated with having a functionally-limited spouse may remove women from the social networks that they depend on, implying that having a functionally-limited spouse may change the aforementioned dynamic. Not only are women more likely to become caregivers than are men, but such responsibilities are more central to women’s identities (Yee & Schulz, 2000). Spousal strain in the form of criticism may be a more salient predictor of distress among female spousal caregivers if it undermines feelings of self-efficacy and accomplishment regarding caregiving, both of which are protective against women’s (but not men’s) depressive symptoms (Hagedoorn, Sanderman, Buunk, & Wobbes, 2002). Therefore, in the current study, we examined whether gender differences emerged when considering the moderating role of own and spousal functional limitations.

Research Aims and Hypotheses

Below, we outline four specific hypotheses as well as four exploratory research questions. In accordance with existing studies of older adults (e.g., Chen & Feeley, 2014; Park et al., 2013; & Santini et al., 2016), we first hypothesized that loneliness would be a mechanism through which lower spousal support and higher spousal strain would each be associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms later in life (H1). We further hypothesized that such indirect associations would be stronger for males than females given that males have smaller social networks (McLaughlin et al., 2010), and that their loneliness is more strongly tied to spousal support and strain (Santini et al., 2016; H2).

We then considered the moderating role of individuals’ own functional limitations. Because functionally limited older adults likely have fewer social resources and may be less able to engage in social activities (Warner et al., 2018), we expected their well-being to be more sensitive to the effects of marital discord (Robles et al., 2014). We hypothesized that direct associations between lower support/higher strain and depressive symptoms would be stronger for more functionally limited older adults (H3). In the same vein, we expected ties between lower support/higher strain and higher loneliness to be stronger for more functionally limited older adults, which would in turn result in higher levels of depressive symptoms (i.e., first-stage moderated mediation; H4). We then explored whether there were any gender differences in the degree to which these associations were moderated by individuals’ functional limitations (RQ1).

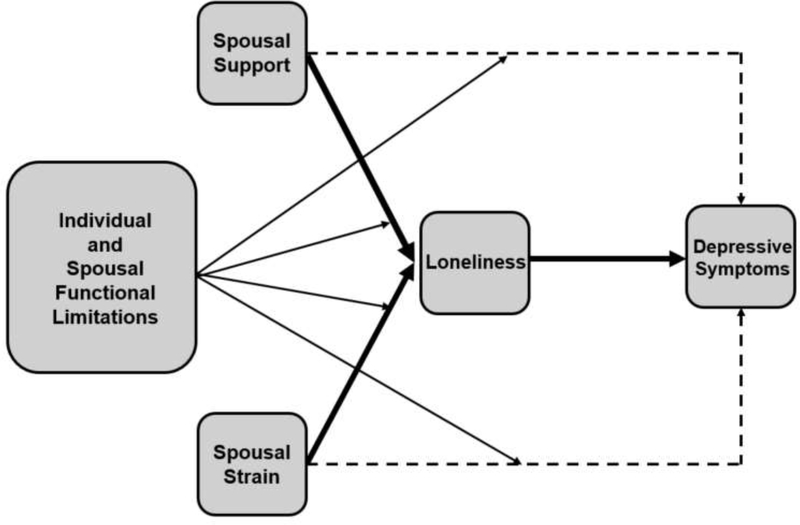

Our final aim was to explore the moderating role of spouses’ (as opposed to individuals’ own) functional limitations. We considered the degree to which spouses’ functional limitations moderated direct associations between spousal support/strain and depressive symptoms (RQ2), as well as indirect associations through loneliness (RQ3). We then explored whether there were any gender differences in the degree to which these associations were moderated by spouses’ functional limitations (RQ4). Our conceptual model is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Conceptual Model.

Note. In light of hypotheses and research questions pertaining to gender differences, this model was also estimated within a multiple group framework to examine differences in path coefficients for males versus females. Dashed lines represent direct associations between spousal support/strain and depressive symptoms. Thick solid lines represent indirect associations through loneliness.

Method

Data came from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS). The HRS is a nationally representative dataset of older adults (age 50+) that oversamples residents of Florida, Blacks, and Hispanics (Bugliari et al., 2016). In order for an HRS respondent (i.e., coversheet respondent) to be included in the present study, they had to complete the psychosocial leave-behind questionnaire (LBQ) in 2014 because measures of loneliness and marital quality were included only in the LBQ. HRS respondents also had to be continuously married or partnered (with no prior marriages) since 2012 so that changes in depressive symptoms captured in the current study were not due to changes in marital/relationship status due to divorce, widowhood, or a new partnership. Finally, because we examined the moderating role of spouses’ functional limitations, HRS respondents were only included if their spouse/partner had also participated. These criteria resulted in an analytical sample size of 1084 HRS respondents and their spouses/partners. On average, these HRS respondents were 66.47 years old and had an average of 13.09 years of education (see Table 1).

Table 1:

Summary of Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations between Variables

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age (years) | - | ||||||||||

| 2. White | −.20** | - | |||||||||

| 3. Education (years) | −.06 | −.16** | - | ||||||||

| 4. Female | −.12** | −.01 | −.06* | - | |||||||

| 5. Baseline depressive symptoms | −.04 | .13** | −.26** | .08* | - | ||||||

| 6. Own functional limitations | .14** | .08* | −.22** | −.05 | .34** | - | |||||

| 7. Spousal functional limitations | .09** | .03 | −.20** | .02 | .13** | .05 | - | ||||

| 8. Spousal strain | −.10** | .12** | −.07* | .03 | .21** | .07* | .04 | - | |||

| 9. Spousal support | .06* | −.09** | −.09 | −.13** | −.20** | −.05 | −.12** | −.54** | - | ||

| 10. Loneliness | −.03 | .07* | −.14** | −.05 | .33** | .16** | .10** | .37** | −.40** | - | |

| 11. Depressive symptomsa | −.03 | .19** | −.24** | .05 | .64** | .33** | .10** | .17** | −.17** | .33** | - |

| M/% | 66.47 | 83.3% | 13.09 | 57.0% | .94 | .23 | .23 | 1.90 | 3.53 | 1.45 | .94 |

| SD | 9.82 | - | 3.12 | - | 1.51 | 0.75 | 0.73 | 0.65 | 0.61 | 0.41 | 1.56 |

Note.

Measured in 2016, all other variables measured in 2014

p < 0.05

p < 0.01.

Measures

Spousal support.

Spousal support was measured in 2014 by the following three items (Walen & Lachman, 2000): (1) How much can you rely on your spouse for help if you have a serious problem, (2) How much does your spouse understand the way you feel about things, and (3) How much can you open up to your spouse if you need to talk about your worries? Response options ranged from 1 (a lot) to 4 (not at all). Items were reverse coded so that higher scores indicated higher levels of perceived spousal support and were then combined into a single mean scale (M = 3.53, SD = .61; see Table 1). Scale reliability was high (α = .81).

Spousal strain.

Spousal strain was measured in 2014 by the following four items (Walen & Lachman, 2000): (1) How often does your spouse/partner put too many demands on you, (2) How often does your spouse/partner criticize you, (3) How often does your spouse/partner let you down, and (4) How often does your spouse/partner get on your nerves? Response options ranged from 1 (a lot) to 4 (not at all). Items were reverse coded so that higher scores indicated higher levels of perceived spousal strain and were then combined into a single mean scale (M = 1.90, SD = .65; see Table 1). Scale reliability was high (Cronbach’s α = .80).

Loneliness.

Loneliness was measured in 2014 by a series of 11 items from the UCLA Loneliness Scale (version 3; Russell, 1996). Participants were asked how often they feel left out, isolated from others, alone, and that they lack companionship, as well as how often they feel that they are in tune with others, are part of a group, have people they can talk to, have people they can turn to, have people who understand them, have people they feel close to, and have a lot in common with friends. The response options for all items included 1 (often), 2 (some of the time) and 3 (hardly ever or never). Positively worded items were reverse coded such that higher scores indicated higher levels of loneliness. Because the UCLA Loneliness Scale was designed as a unidimensional measure of loneliness, all items were combined into a single mean scale (M = 1.45, SD = .41; see Table 1). The 11 items included in this mean scale have been shown to load onto a single unidimensional loneliness factor with statistically significant (p < .05) factor loadings ranging from .40 to .79 (absolute values; Russell, 1996). Scale reliability was high (Cronbach’s α = .88).

Depressive symptoms.

In both 2014 and 2016, levels of depressive symptoms were measured by a series of 8 items from the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CESD: Radloff, 1977). Respondents indicated whether, in the past week, they felt depressed, alone, sad, that everything they did was an effort, that they could not get going, that their sleep was restless, and whether they felt happy and enjoyed life. Because we sought to evaluate the degree to which loneliness mediated associations between marital quality and depressive symptoms, we did not include the item “felt alone” in our measure of depressive symptoms as to not artificially inflate the association between loneliness and depressive symptoms. Responses were dichotomized such that participants indicated whether they felt this way all or most of the time (value of 1) or not (value of 0). Positively worded indicators were reverse coded and then all eight items were combined into a single sum score such that higher scores represented higher levels of depressive symptoms in both 2014 (M = .94, SD = 1.51; see Table 1) and 2016 (M = .94, SD = 1.56; see Table 1). Scale reliability was acceptable for respondents in 2014 and 2016, respectively (Cronbach’s α = .77 and α = .71).

Functional limitations.

Functional limitations were assessed in 2014 by the Wallace and Herzog (1995) measure assessing activities of daily living. Both HRS respondents and their spouses indicated whether they had difficulty with any of the following five tasks: dressing, bathing, eating, walking across the room, and getting in and out of bed (1 = yes and 0 = no). These items were then summed together to create a 0 to 5 scale. In the current sample, 12.3% of HRS respondents had at least one functional limitation. Among those who needed help with their functional limitations (54%), most (74%) named their spouse as their primary helper. A similar pattern emerged when considering spouses’ functional limitations. In the current sample, 12.8% of spouses had at least one functional limitation. Among those spouses who needed help with their functional limitations (53.6%), most (81.6%) named the HRS respondent as their primary helper.

Covariates.

Covariates included respondents’ age, gender, race (white versus non-white), and years of education as of 2014. We also included their depressive symptoms in 2014, which enabled us to predict change in depressive symptoms across 2 years. When examining the moderating role of HRS respondents’ own functional limitations, we included their spouses’ functional limitations as a covariate. Similarly, when examining the moderating role of spousal functional limitations, we included respondents’ own functional limitations as a covariate.

Analytic Strategy

To test our hypotheses and address our research questions, we estimated a series of path models utilizing Mplus Version 8.1. We evaluated global model fit using the chi-square (χ2) test, the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA). Because the chi-square (χ2) test is overly sensitive to large sample sizes, we interpreted it in conjunction with other global model fit indices. Endogenous variables (i.e., loneliness and depressive symptoms) were regressed on all covariates. All demographic covariates (e.g., gender, education) were allowed to covary with one another, as were the focal predictors (e.g., spousal support, own functional limitations). Modification indices suggested that global model fit would improve if we added additional covariances between (1) age and own functional limitations and (2) spousal support and gender. Because existing literature indicates that age and functional limitations are associated (Covinsky, Lindquist, Dunlap, & Yelin, 2009), and spousal support and gender are associated (Neff & Karney, 2005), we added these covariances to our model. This approach enabled us to have enough degrees of freedom to estimate global model fit, which was necessary to statistically test for gender differences. Further, findings from a fully saturated model (wherein all exogenous variables were allowed to covary) yielded estimates that were extremely similar to those reported in the current study. All models were estimated with full information maximum likelihood estimation to handle missing data. Missing data ranged from 0% - 2%, depending on the variable. We included spousal support and strain in the same model in order to examine their unique role, net of the other, as predictors of loneliness and depressive symptoms. Because spousal support, spousal strain, loneliness, and 2016 depressive symptoms were skewed (skewness values = −1.63, .73, .82, and 2.10, respectively), we estimated all paths in our models (both direct and indirect) with bootstrapping (10,000 replications). Although large sample sizes are more robust to violations of normality, we opted to bootstrap all model estimates, which are presented with a corresponding 95% confidence interval (Ng & Lim, 2016; Russell & Dean, 2000).

We first estimated a model that included direct effects from spousal support and strain to depressive symptoms, as well as indirect effects through loneliness (testing H1). To test H2, we estimated a multiple group model (males vs. females) to assess whether there were gender differences in these indirect effects. Utilizing the MODEL CONSTRAINT command in MPLUS, we calculated the difference of the indirect effect of support on depressive symptoms through loneliness for men versus women and determined whether this difference was significantly different from zero (Muthén & Muthén, 2017). We followed the same procedure to test for gender differences in the indirect effect of strain on depressive symptoms through loneliness.

To examine the moderating role of individuals’ functional limitations, we then included interaction terms between (1) spousal support and HRS respondents’ functional limitations and (2) spousal strain and HRS respondents’ functional limitations as predictors of both their depressive symptoms (H3) and loneliness (H4). We probed significant interactions using the Johnson-Neyman technique (Preacher, Curran, & Bauer, 2006). If interactions between spousal support (or strain) and functional limitations predicting loneliness were statistically significant, we then tested for first-stage moderated mediation (Hayes, 2015). Thus, to determine whether indirect effects of spousal support (or strain) on depressive symptoms through loneliness significantly differed for HRS respondents with different levels of functional limitations, we specified models that computed the magnitude of the difference of the indirect effect across different levels of functional limitations, as well as corresponding bootstrapped standard errors and 95% confidence intervals (Preacher, Rucker, & Hayes, 2007).

To address RQ1, we examined whether there were any gender differences in moderation by individuals’ own functional limitations. We utilized likelihood ratio chi-square (χ2) difference testing to compare nested models to determine if constraining the interaction between spousal support and own functional limitations predicting depressive symptoms to be equal for men and women significantly worsened global model fit. If this constraint significantly worsened fit, we concluded that the degree to which individuals’ own limitations moderated the relationship between spousal support and depressive symptoms differed for men versus women. We repeated this process when testing for the interaction between spousal support and functional limitations predicting loneliness, and when testing the parallel set of interactions involving spousal strain.

We replicated this entire set of procedures to examine the moderating role of spousal (as opposed to own) functional limitations. We included interaction terms between (1) spousal support and spouses’ functional limitations and (2) spousal strain and spouses’ functional limitations as predictors of both HRS respondents’ depressive symptoms (RQ2) and loneliness (RQ3). If interactions between spousal support (or strain) and spouses’ functional limitations predicting loneliness were statistically significant, we then tested for first-stage moderated mediation. Finally, we explored any potential gender differences in the degree to which spouses’ functional limitations moderated associations between spousal support/strain, loneliness and depressive symptoms utilizing likelihood ratio chi-square (χ2) testing as described above (RQ4).

Results

Indirect Associations through Loneliness

Full sample model.

We estimated a model that examined direct associations between spousal support/strain and subsequent depressive symptoms, as well as indirect associations through loneliness. This model had good global model fit [χ2(18) = 66.50, p < .001; CFI = .94; RMSEA = .05 (90% CI = .04 – .06)] and accounted for 28% (R2 = .28) and 47% (R2 = .47) of variance in loneliness and depressive symptoms, respectively (see Table 2). After accounting for baseline depressive symptoms, own and spousal functional limitations, and demographic covariates, there was a significant indirect association between spousal support and depressive symptoms through loneliness (b = −.06, p = .011, 95% CI = −.11 – −.02), supporting H1. The direct association between spousal support and depressive symptoms was not significant. Also in support of H1, there was a significant indirect association between spousal strain and depressive symptoms through loneliness (b = .04, p = .016, 95% CI = .01 – .07). The direct association between spousal strain and depressive symptoms was not significant (see Table 2).

Table 2:

Models for Spousal Support and Strain as the Focal Predictors on the Full Sample of Couples (N = 1084 Couples)

| Main Effects | Moderation by Own Limitations | Moderation by Spousal Limitations | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | b | SE b | 95% CI | b | SE b | 95% CI | b | SE b | 95% CI |

| Loneliness ← | |||||||||

| Age (years) | −.01 | .01 | −.03 – .01 | −.01 | .01 | −.03 – .02 | −.01 | .01 | −.03 – .01 |

| White | −.03 | .03 | −.09 – .03 | −.03 | .03 | −.09 – .03 | −.03 | .03 | −.09 – .03 |

| Education (years) | .01 | .07 | −.20 – .02 | .01 | .06 | −.19 – .02 | .01 | .07 | −.21 – .02 |

| Female | −.09*** | −.02 | −.13 – −.05 | −.09*** | −.02 | −.13 – −.05 | −.09*** | −.02 | −.15 – −.05 |

| Baseline Depressive Symptoms | .07*** | .01 | .05 – .09 | .07*** | .01 | .05 – .09 | .07*** | .01 | .05 – .09 |

| Own Functional Limitations | .02 | .02 | −.01 – .05 | .02 | .02 | −.01 – .05 | .02 | .02 | −.01 – .05 |

| Spousal Functional Limitations | .02 | .02 | −.02 – .05 | .02 | .02 | −.02 – .05 | .03 | .02 | −.01 – .06 |

| Spousal Support | −.17*** | .03 | −.22 – −.12 | −.17*** | .03 | −.22 – −.12 | −.18*** | .03 | −.23 – −.13 |

| Spousal Strain | .11*** | .02 | .07 – .15 | .11*** | .02 | .07 – .15 | .11*** | .02 | .07 – .15 |

| Spousal Support x Own Functional Limitations | .01 | .02 | −.03 – .04 | ||||||

| Spousal Strain x Own Functional Limitations | .01 | .02 | −.03 – .03 | ||||||

| Spousal Support x Spouse Functional Limitations | .02 | .02 | −.02 – .04 | ||||||

| Spousal Strain x Spouse Functional Limitations | −.004 | .02 | −.04 – .03 | ||||||

| Depressive Symptoms ← | |||||||||

| Age (years) | .04 | .05 | −.06 – .13 | .03 | .05 | −.06 – .12 | .04 | .05 | −.05 – .13 |

| White | .39** | .13 | .12 – .64 | .40** | .13 | .13 – .65 | .38** | .13 | .11 – .63 |

| Education (years) | −.003 | .71 | −2.26 – .17 | −.004 | .67 | −2.16 – .28 | −.004 | .73 | −2.30 – .09 |

| Female | .05 | .08 | −.10 – .20 | .06 | .08 | −.10 – .21 | .05 | .08 | −.11 – .19 |

| Baseline Depressive Symptoms | .58*** | .05 | .48 – .67 | .58*** | .05 | .49 – .68 | .58*** | .05 | .48 – .67 |

| Loneliness | .35** | .13 | .10 – .59 | .37** | .13 | .12 – .61 | .35** | .13 | .10 – .59 |

| Own Functional Limitations | .31*** | .09 | .13 – .49 | .30** | .10 | .12 – .49 | .31*** | .09 | .13 – .49 |

| Spousal Functional Limitations | .01 | .07 | −.13 – .14 | .01 | .07 | −.13 – .14 | .04 | .08 | −.12 – .18 |

| Spousal Support | −.04 | .10 | −.24 – .16 | .05 | .11 | −.16 – .26 | −.02 | .10 | −.23 – .18 |

| Spousal Strain | .003 | .08 | −.16 – .16 | −.02 | .09 | −.20 – .14 | .01 | .08 | −.17 – .16 |

| Spousal Support x Own Functional Limitations | .25* | .11 | .04 – .48 | ||||||

| Spousal Strain x Own Functional Limitations | −.01 | .10 | −.22 – .16 | ||||||

| Spousal Support x Spouse Functional Limitations | .10 | .08 | −.06 – .26 | ||||||

| Spousal Strain x Spouse Functional Limitations | .03 | .09 | −.18 – .17 | ||||||

Note.

p < 0.01

p < .001.

Gender model.

We then estimated this model within a multiple group framework to examine potential gender differences in these indirect associations. This multiple group model had good global model fit [χ2(28) = 75.33, p < .001; CFI = .95; RMSEA = .06 (90% CI = .04 – .07)]. For males, this model accounted for 31% (R2 = .31) and 53% (R2 = .53) of variance in loneliness and depressive symptoms, respectively. For females, this model accounted for 27% (R2 = .27) and 55% (R2 = .55) of variance in loneliness and depressive symptoms, respectively.

For spousal support, there was a significant indirect association through loneliness for males (b = −.06, p = .044, 95% CI = −.13 – −.004) and a trend-level indirect association for females (b = −.06, p = .082, 95% CI = −.13 – .003). Contrary to H2, however, the magnitude of the difference in the indirect effect for support between males and females was not significant (b = −.01, p = .870, 95% CI = −.10 – .09). For spousal strain, there was a trend-level indirect association through loneliness for males (b = .04, p = .058, 95% CI = .003 – .09) and a non-significant indirect association for females (b = .03, p = .121, 95% CI = −.001 – .07). Contrary to H2, however, the magnitude of the difference in the indirect effect for strain between males and females was not significant (b = .01, p = .742, 95% CI = −.05 – .07). Model estimates for direct associations for males and females are detailed in Tables 3 and 4, respectively.

Table 3:

Models for Spousal Support and Strain as the Focal Predictors for Couples with Male Target Respondents (N = 464 Couples)

| Main Effects | Moderation by Own Limitations | Moderation by Spousal Limitations | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | b | SE b | 95% CI | b | SE b | 95% CI | b | SE b | 95% CI |

| Loneliness ← | |||||||||

| Age (years) | .01 | .02 | −.03 – .04 | .01 | .02 | −.02 – .04 | .01 | .02 | −.03 – .04 |

| White | −.03 | .04 | −.12 – .05 | −.03 | .04 | −.12 – .05 | −.03 | .04 | −.12 – .05 |

| Education (years) | .01 | .25 | −.78 – .02 | .01 | .29 | −.86 – .02 | .01 | .25 | −.78 – .02 |

| Baseline Depressive Symptoms | .07*** | .02 | .04 – .10 | .07*** | .02 | .04 – .10 | .07*** | .02 | .04 – .10 |

| Own Functional Limitations | .05* | .02 | .01 – .09 | .06** | .02 | .01 – .10 | .05** | .02 | .01 – .09 |

| Spousal Functional Limitations | .04 | .03 | −.01 – .08 | .04 | .02 | −.01 – .08 | .05 | .03 | −.003 – .10 |

| Spousal Support | −.19*** | .04 | −.27 – −.11 | −.20*** | .04 | −.28 – −.12 | −.20*** | .04 | −.27 – −.11 |

| Spousal Strain | .13*** | .03 | .07 – .19 | .13*** | .03 | .07 – .19 | .12*** | .03 | .06 – .18 |

| Spousal Support x Own Functional Limitations | −.05* | .03 | −.11 – −.01 | ||||||

| Spousal Strain x Own Functional Limitations | −.03 | .03 | −.09 – .02 | ||||||

| Spousal Support x Spouse Functional Limitations | .02 | .02 | −.02 – .07 | ||||||

| Spousal Strain x Spouse Functional Limitations | −.01 | .03 | −.06 – .05 | ||||||

| Depressive Symptoms ← | |||||||||

| Age (years) | .08 | .06 | −.04 – .19 | .05 | .06 | −.05 – .16 | .09 | .06 | −.02 – .20 |

| White | .17 | .18 | −.19 – .51 | .22 | .18 | −.14 – .58 | .20 | .18 | −.17 – .55 |

| Education (years) | .002 | .96 | −3.01 – .02 | .001 | .82 | −2.58 – .22 | .002 | .94 | −2.93 – .02 |

| Baseline Depressive Symptoms | .65*** | .07 | .50 – .78 | .66*** | .07 | .52 – .81 | .64*** | .07 | .50 – .77 |

| Loneliness | .34* | .15 | .02 – .61 | .40* | .16 | .08 – .68 | .34* | .15 | .02 – .61 |

| Own Functional Limitations | .28* | .12 | .03 – .51 | .22 | .16 | −.02 – .43 | .29* | .13 | .03 – .52 |

| Spousal Functional Limitations | −.07 | .07 | −.23 – .06 | −.08 | .07 | −.23 – .05 | −.08 | .08 | −.26 – .04 |

| Spousal Support | .19 | .12 | −.05 – .40 | .30* | .13 | .03 – .53 | .18 | .12 | −.06 – .39 |

| Spousal Strain | .05 | .09 | −.13 – .23 | .02 | .10 | −.20 – .18 | .07 | .10 | −.13 – .25 |

| Spousal Support x Own Functional Limitations | .38* | .15 | .07 – .65 | ||||||

| Spousal Strain x Own Functional Limitations | .05 | .14 | −.32 – .20 | ||||||

| Spousal Support x Spouse Functional Limitations | .04 | .08 | −.14 – .16 | ||||||

| Spousal Strain x Spouse Functional Limitations | .13 | .09 | −.09 – .27 | ||||||

Note.

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < .001.

Table 4:

Models for Spousal Support and Strain as the Focal Predictors for Couples with Female Target Respondents (N = 620 Couples)

| Main Effects | Moderation by Own Limitations | Moderation by Spousal Limitations | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | b | SE b | 95% CI | b | SE b | 95% CI | b | SE b | 95% CI |

| Loneliness ← | |||||||||

| Age (years) | −.02 | .02 | −.05 – .01 | −.01 | .02 | −.05 – .02 | −.02 | .02 | −.05 – .01 |

| White | −.02 | .04 | −.11 – .06 | −.02 | .04 | −.10 – .06 | −.03 | .04 | −.11 – .05 |

| Education (years) | .01 | .11 | −.38 – .12 | .01 | .11 | −.34 – .15 | .01 | .12 | −.40 – .10 |

| Baseline Depressive Symptoms | .07*** | .01 | .05 – .10 | .08*** | .01 | .05 – .10 | .08*** | .01 | .05 – .10 |

| Own Functional Limitations | −.01 | .02 | −.05 – .03 | −.01 | .02 | −.05 – .04 | −.01 | .02 | −.05 – .03 |

| Spousal Functional Limitations | .002 | .02 | −.04 – .05 | .004 | .02 | −.04 – .05 | .01 | .02 | −.04 – .06 |

| Spousal Support | −.17*** | .03 | −.23 – −.10 | −.16*** | .03 | −.23 – −.10 | −.17*** | .03 | −.24 – −.11 |

| Spousal Strain | .09** | .03 | .04 – .15 | .10** | .03 | .04 – .15 | .09** | .03 | .04 – .15 |

| Spousal Support x Own Functional Limitations | .04 | .02 | −.001 – .09 | ||||||

| Spousal Strain x Own Functional Limitations | .03 | .02 | −.01 – .06 | ||||||

| Spousal Support x Spouse Functional Limitations | .02 | .03 | −.05 – .05 | ||||||

| Depressive Symptoms ← | |||||||||

| Age (years) | −.02 | .07 | −.16 – .12 | −.02 | .07 | −.15 – .13 | −.01 | .07 | −.14 – .12 |

| White | .49* | .19 | .11 – .86 | .49* | .19 | .10 – .84 | .45* | .19 | .07 – .82 |

| Education (years) | −.75 | 1.25 | −3.23 – 1.63 | −.75 | 1.25 | −3.30 – 1.57 | −.94 | −.76 | −3.490 – 1.34 |

| Baseline Depressive Symptoms | .54*** | .06 | .41 – .66 | .54*** | .07 | .41 – .66 | .54*** | .07 | .41 – .66 |

| Loneliness | .34 | .19 | −.02 – .72 | .36 | .19 | −.01 – .73 | .36 | .18 | .001 – .72 |

| Own Functional Limitations | .32* | .13 | .09 – .59 | .38* | .20 | .05 – .83 | .31* | .12 | .09 – .58 |

| Spousal Functional Limitations | .14 | .28 | −.12 – .38 | .13 | .12 | −.12 – .37 | .16 | .13 | −.13 – .38 |

| Spousal Support | −.19 | .16 | −.05 – .10 | −.15 | .18 | −.49 – .20 | −.19 | .18 | −.50 – .22 |

| Spousal Strain | −.06 | .12 | −.30 – .18 | −.09 | .14 | −.37 – .19 | −.08 | .13 | −.32 – .19 |

| Spousal Support x Own Functional Limitations | .07 | .20 | −.23 – .57 | ||||||

| Spousal Strain x Own Functional Limitations | −.11 | .17 | −.43 – .25 | ||||||

| Spousal Support x Spouse Functional Limitations | .05 | .27 | −.23 – .71 | ||||||

| Spousal Strain x Spouse Functional Limitations | −.15 | .18 | −.47 – .24 | ||||||

Note.

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < .001.

Moderating Role of Individuals’ Own Functional Limitations

Full sample model.

Next, we examined the moderating role of HRS respondents’ own functional limitations by adding interactions between spousal support and own functional limitations as predictors of both loneliness and depressive symptoms, as well as interactions between spousal strain and own functional limitations as predictors of both loneliness and depressive symptoms (thus resulting in the addition of 4 interaction terms). This model had good global model fit [χ2(26) = 69.17, p < .001; CFI = .95; RMSEA = .04 (90% CI = .03 – .05)] and accounted for 28% (R2 = .28) and 47% (R2 = .47) of variance in loneliness and depressive symptoms, respectively.

In support of H3, there was a significant interaction between spousal support and own functional limitations predicting depressive symptoms (b = .25, p = .025, 95% CI = .04 – .48; see Table 2). The association between spousal support and depressive symptoms was positive at the level of a trend for individuals with high (+1SD) functional limitations (b = .31, p = .096, 95% CI = −.05 – .67) and not significant for individuals with low (−1SD) functional limitations (b = −.20, p = .107, 95% CI = −.45 – .03). Contrary to H3, the direct association between spousal strain and depressive symptoms was not moderated by individuals’ own limitations (see Table 2).

To test H4, we examined the extent to which associations between spousal support/strain and loneliness (as opposed to depressive symptoms) were moderated by one’s own functional limitations. This hypothesis was not supported. An individual’s functional limitations did not moderate the association between spousal support and loneliness, nor the association between spousal strain and loneliness. We therefore did not go on to test for first-stage moderated mediation.

Gender model.

To address RQ1, we then estimated this model within a multiple group framework to examine potential gender differences in the extent to which individuals’ own functional limitations moderated these associations. This multiple group model had good global model fit [χ2(40) = 85.64, p < .001; CFI = .95; RMSEA = .05 (90% CI = .03 – .06)]. For males, this model accounted for 32% (R2 = .32) and 56% (R2 = .56) of variance in loneliness and depressive symptoms, respectively. For females, this model accounted for 27% (R2 = .27) and 64% (R2 = .55) of variance in loneliness and depressive symptoms, respectively.

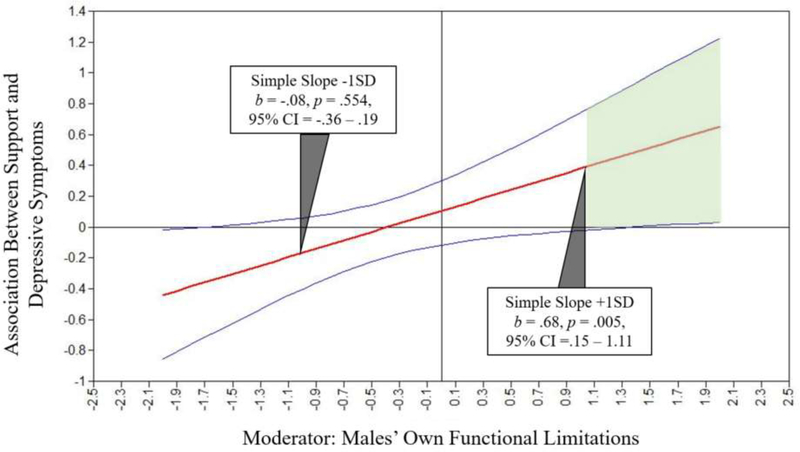

Results indicated that gender qualified the previously detected interaction between spousal support and own functional limitations predicting depressive symptoms, such that the interaction was statistically significant for males (b = .38, p = .011, 95% CI = .07 – .65; see Table 3) and not females (b = .07, p = .743, 95% CI = −.23 – .57; see Table 4). A likelihood ratio chi-square (χ2) difference test indicated that constraining this interaction to be equal for males and females significantly worsened global model fit [χ2 (1) = 3.99, p = .046]. Thus, one’s own functional limitations moderated the association between spousal support and depressive symptoms for males only. The nature of the interaction for males (see Figure 2) mirrored the nature of the interaction detected in the full sample. The direct association between spousal support and depressive symptoms was significant and positive for males with high functional limitations only. Thus, spousal support appeared to be detrimental for functionally limited males’ well-being. The interaction between strain and individuals’ functional limitations predicting depressive symptoms was not statistically significant for males or females (see Tables 3 and 4).

Figure 2. The Association between Support and Depressive Symptoms across Standard Deviation Units of Males’ Own Functional Limitations.

Note. Shaded green area represents region of statistical significance (p < .05) because the confidence bands do not include zero.

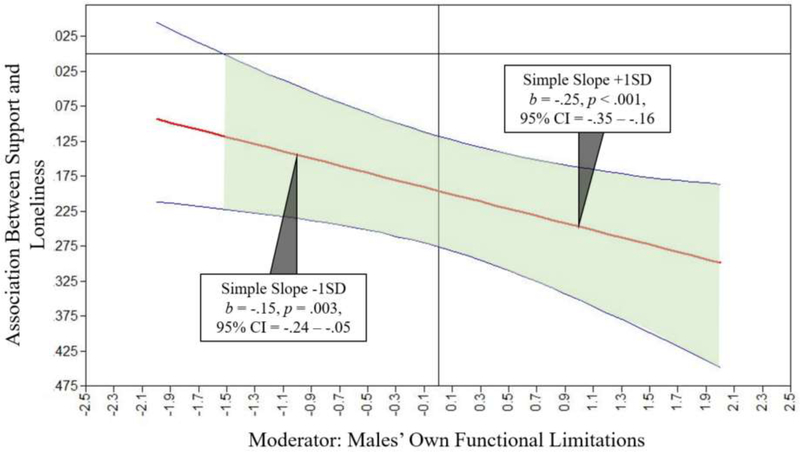

We also examined whether there were gender differences in the extent to which associations between spousal support/strain and loneliness (as opposed to depressive symptoms) were moderated by one’s own functional limitations. We found that there was a statistically significant interaction between spousal support and own functional limitations predicting loneliness for males (b = −.05, p = .047, 95% CI = −.11 – −.01; see Table 3) but not females (b = .04, p = .110, 95% CI = −.001 – .09; see Table 4). A likelihood ratio chi-square (χ2) difference test indicated that constraining this interaction to be equal for males and females significantly worsened global model fit [χ2 (1) = 9.49, p = .002]. Thus, one’s own functional limitations moderated the association between spousal support and loneliness for males only. As illustrated in Figure 3, the negative association detected between spousal support and loneliness was statistically significant across almost all levels of males’ own functional limitations. However, the negative association was stronger (i.e., more negative) at higher levels of functional limitations. Thus, the protective effect of spousal support on loneliness was amplified when older males were coping with more functional limitations. In light of this interaction, we went on to test for first-stage moderated mediation for males. There was trend-level moderated mediation for males (index of moderated mediation = .01, p = .082, 95% CI = 0.001 – 0.025). Thus, the indirect association between support and depressive symptoms through loneliness was marginally stronger among older males who were more functionally limited.

Figure 3. The Association between Support and Loneliness across Standard Deviation Units of Males’ Own Functional Limitations.

Note. Shaded green area represents region of statistical significance (p < .05) because the confidence bands do not include zero.

Lastly, the interaction between spousal strain and individuals’ own functional limitations predicting loneliness was not statistically significant either for males or for females (see Tables 3 and 4). We therefore did not go on to test for first-stage moderated mediation.

Moderating Role of Spousal Functional Limitations

Full sample model.

In light of RQ2 and RQ3, we then explored the moderating role of spousal (as opposed to own) functional limitations. To do so, we added interactions between spousal support and spousal functional limitations as predictors of both loneliness and depressive symptoms, as well as interactions between spousal strain and spousal functional limitations as predictors of both loneliness and depressive symptoms (thus resulting in the addition of 4 interaction terms). This model had good global model fit [χ2(26) = 83.91, p < .001; CFI = .93; RMSEA = .05 (90% CI = .04 – .06)] and accounted for 29% (R2 = .29) and 47% (R2 = .47) of variance in loneliness and depressive symptoms, respectively. As indicated in Table 2, spousal functional limitations did not moderate direct associations between spousal support (or spousal strain) and depressive symptoms (RQ2). Spousal functional limitations also did not moderate associations between spousal support (or spousal strain) and loneliness; we therefore did not go on to test for first-stage moderated mediation (RQ3).

Gender model.

To address RQ4, we estimated this model within a multiple group framework to examine gender differences in the extent to which spousal functional limitations moderated these associations. This multiple group model had good global model fit [χ2(40) = 95.73, p < .001; CFI = .94; RMSEA = .05 (90% CI = .04 – .06)]. For males, this model accounted for 32% (R2 = .32) and 53% (R2 = .53) of variance in loneliness and depressive symptoms, respectively. For females, this model accounted for 27% (R2 = .27) and 60% (R2 = .60) of variance in loneliness and depressive symptoms, respectively. As indicated in Tables 3 and 4, however, spousal functional limitations did not significantly moderate any associations of interest for either males or females.

Summary of Findings

In sum, we found that loneliness was a mechanism through which both spousal support and spousal strain were each associated with depressive symptoms, but that these indirect associations did not significantly differ between males and females. We found that individuals’ own functional limitations moderated the association between spousal support (but not strain) and depressive symptoms for males only. The direct association between support and depressive symptoms (represented by the dashed line from spousal support to depressive symptoms in Figure 1) was only significant for males with higher levels of functional limitations, but in a positive direction. More specifically, spousal support was associated with greater depressive symptoms for functionally limited men. Similarly, males’ own functional limitations moderated the association between spousal support (but not strain) and loneliness (represented by the thick solid line from spousal support to loneliness in Figure 1). In this case, spousal support was associated with lower levels of loneliness at higher levels of functional limitations. Furthermore, the indirect association between support and depressive symptoms through loneliness was marginally stronger among older males who were more functionally limited. These findings imply that when spousal support reduces loneliness it can also reduce the depressive symptoms of functionally limited males; in contrast, spousal support that does not reduce functionally limited males’ loneliness may actually increase their depressive symptoms. Thus, for functionally limited males, support reduces depressive symptoms insofar as it reduces loneliness, but otherwise increases depressive symptoms.

Discussion

Findings from the current study suggest that loneliness is a mechanism through which marital discord—particularly lower levels of spousal support—is associated with depressive symptoms later in life. Notably, findings pertaining to spousal strain were less consistent and more sensitive to sample size, which was likely a byproduct of there being low levels of spousal strain reported in the current sample. Consistent with the SAVI Model (Charles, 2010), however, links between spousal support, loneliness, and depressive symptoms were contextually dependent on individuals’ own (but not their spouse’s) functional limitations and gender.

For males, there was a significant indirect association between spousal support and depressive symptoms through loneliness such that higher levels of support reduced loneliness and, in turn, depressive symptoms. This indirect association, however, was marginally moderated by males’ functional limitations. By probing statistically significant interactions between spousal support and males’ functional limitations as predictors of their loneliness and depressive symptoms, we found that associations were stronger for males who were more functionally limited. Functionally limited males may have even fewer social resources than males who are not functionally limited, which may further amplify the central role of spousal support (Burholt & Scharf, 2013).

More specifically, we found that spousal support was directly associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms for functionally limited males. This finding was contrary to our hypothesis that spousal support would be particularly protective against depressive symptoms among highly limited older adults. We expected marriages characterized by higher levels of understanding and warmth would be beneficial for older adults who were in poorer physical health (Carr, Cornman, & Freedman, 2017). However, spousal support may be directly associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms because males who are coping with more limitations (including those imposed by depressive symptoms) may need more support. It may also be that spousal support threatens functionally limited males’ self-esteem or self-efficacy (Penninx et al., 1998b). The literature on invisible support is centered on the premise that, in the context of stress, awareness of support receipt from a partner comes with an emotional cost, such as increased depressive symptoms (Bolger, Zuckerman, & Kessler, 2000). This finding, however, should be interpreted cautiously due to the small percentage of HRS respondents coping with high levels of functional limitations in the current sample. It will be important to re-examine the moderating role of functional limitations as this cohort of HRS respondents gets older, and as functional limitations increase.

Although statistically significant across almost all levels of males’ functional limitations, the association between spousal support and males’ loneliness was stronger at higher levels of limitations. This finding was consistent with our hypothesis and existing research indicating that functionally limited older adults in supportive (as opposed to unsupportive) marriages are better protected against loneliness (Warner & Adams, 2012; Warner & Kelley-Moore, 2012). Spousal support therefore appears to be most advantageous for reducing loneliness among functionally limited males, who perhaps are the most reliant on their spouses (as opposed to other social network members) for support. Trend-level findings further indicated that the indirect association of spousal support on depressive symptoms through decreased loneliness was similarly stronger for functionally limited males. Together, these findings highlight how functionally limited males may be particularly vulnerable to effects of marital discord when it takes the form of low levels of spousal support (Robles et al., 2014).

For females, we detected only a trend-level indirect association of spousal support on depressive symptoms through loneliness. This is perhaps unsurprising given that married older women are more likely to rely on a diverse array of social ties for emotional support, including friends and relatives, whereas married older men rely predominantly on their spouse (Gurung, Taylor, & Seeman, 2003). Research further indicates that support from friends and children may be more effective at combatting older women’s depressive symptoms via reductions in loneliness (Park et al., 2013; Santini et al., 2016). Accordingly, our models consistently accounted for less variance in females’ loneliness (27%) as compared to males’ loneliness (31–32%).

Neither direct nor indirect associations between spousal support and females’ depressive symptoms were moderated by own or spousal functional limitations. Although the vast majority of spouses in our sample who were coping with functional limitations named the HRS respondent as their primary helper, mean levels of spousal functional limitations were low. It will therefore be important to re-examine the moderating role of spousal functional limitations as this cohort gets older and presumably spousal functional limitations increase. In a caregiving context, the need for support outside the marital relationship may become even more important for females, as relationships with friends and neighbors play a unique role in predicting resiliency among spousal caregivers (Donnellan, Bennett, & Soulsby, 2017).

Limitations and Future Research Directions

Several limitations pave the way for future research. First, we examined loneliness as a unidimensional construct, precluding an examination of a possible distinction between emotional loneliness and social loneliness. Whereas emotional loneliness is tied to the absence of an intimate relationship (e.g., spouse), social loneliness is tied to the absence of a broader social network comprised of various social ties, such as children and friends (De Jong Gierveld et al., 2009). These dimensions of loneliness appear differentially associated with depression, as emotional—but not social—loneliness has been identified as a significant correlate of depression among older adults (Peerenboom, Collard, Naarding, & Comijs, 2015). Future research should consider the extent to which emotional and social loneliness each mediate associations between marital quality and depressive symptoms, as well as how such associations may vary by gender and across different levels of individual and spousal functional limitations.

Second, spousal support/strain and loneliness were measured at the same wave, thus limiting our ability to make claims about directionality. We chose this approach in light of our theoretical rationale, and because HRS participants were only administered the leave-behind psychosocial questionnaire (which included measures of spousal support/strain and loneliness) every four years. We posited that associations between marital quality and loneliness likely unfold on a shorter timescale (i.e., across months). Future research may also want to re-examine these associations using measures of marital quality and loneliness that are more likely to vary on a daily, or even momentary, timescale (e.g., daily exchanges of support, partner responsiveness), which would better afford the opportunity to tease apart directionality.

Third, although our analyses were dyadic in that they considered the moderating role of spousal health, associations between marital quality, loneliness, and depressive symptoms were focused on individuals. Recent research suggests that there are dyadic associations between marital quality and loneliness such that one spouse’s perception of support predicts the other’s loneliness and vice versa (Hsieh & Hawkley, 2018; Moorman, 2016; & Stokes, 2017). Future studies ought to include such dyadic effects when examining the moderating roles of own and spousal functional limitations on associations between marital quality and loneliness.

Finally, our analytic sample was limited in that all couples were heterosexual, in their first marriages, and relatively functionally healthy. Thus, future studies ought to re-examine these associations within more diverse samples of couples, particularly those who are currently navigating a stressful health transition (e.g., rehabilitation period after a major surgery) during which spousal support may be particularly beneficial, and spousal strain may be particularly detrimental, to older adults’ psychological well-being.

Conclusion

Spousal support is protective against older adults’ depressive symptoms via reductions in loneliness. Consistent with the SAVI Model (Charles, 2010), however, findings from the current study reinforce the importance of taking a contextualized approach when examining associations between support and emotional well-being later in life. In doing so, we found that associations between support and both loneliness and depressive symptoms differed across levels of functional limitations and gender. For functionally limited males in particular, we found that when spousal support reduced loneliness, it also reduced depressive symptoms; however, when spousal support did not reduce loneliness, such support was actually harmful for functionally limited males’ well-being. Together, these findings suggest that interventions aimed at bolstering functionally limited males’ later-life well-being should target the promotion of supportive spousal interactions, and perhaps those that are specifically aimed at reducing loneliness.

Acknowledgments:

This research was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health under grants AG049676 and AG064360.

References

- Antonucci TC, Lansford JE, & Akiyama H (2001). Impact of positive and negative aspects of marital relationships and friendships on well-being of older adults. Applied Developmental Science, 5, 68–75. doi: 10.1207/S1532480XADS0502_2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barry LC, Allore HG, Guo Z, Bruce ML, & Gill TM (2008). Higher burden of depression among older women: The effect of onset, persistence, and mortality over time. Archives of General Psychiatry, 65, 172–178. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2007.17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beach SRH, Sandeen EE, & O’Leary KD (1990). Depression in marriage: A model for etiology and treatment. New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Blazer DG (2003). Depression in late life: Review and commentary. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 58, M249–M265. doi: 10.1093/gerona/58.3.M249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N, Zuckerman A, & Kessler RC (2000). Invisible support and adjustment to stress. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79, 953–961. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.79.6.953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bookwala J, & Franks MM (2005). Moderating role of marital quality in older adults’ depressed affect: Beyond the main-effects model. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 60, P338–P341. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.6.P338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bugliari D, Campbell N, Chan C, Hayden O, Hurd M, Main R, … Moldoff M (2016). RAND HRS data documentation, version P. RAND Center for the Study of Aging. [Google Scholar]

- Burholt V, & Scharf T (2013). Poor health and loneliness in later life: The role of depressive symptoms, social resources, and rural environments. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 69, 311–324. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbt121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC, & Thisted RA (2010). Perceived social isolation makes me sad: 5-year cross-lagged analyses of loneliness and depressive symptomatology in the Chicago Health, Aging, and Social Relations Study. Psychology and Aging, 25, 453–463. doi: 10.1037/a0017216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr D, Cornman JC, & Freedman VA (2017). Disability and activity-related emotion in later life: Are effects buffered by intimate relationship support and strain? Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 58, 387–403. doi: 10.1177/0022146517713551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles ST (2010). Strength and vulnerability integration: A model of emotional well-being across adulthood. Psychological Bulletin, 136, 1068–1091. doi: 10.1037/a0021232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, & Feeley TH (2014). Social support, social strain, loneliness, and well-being among older adults: An analysis of the Health and Retirement Study. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 31, 141–161. doi: 10.1177/0265407513488728 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cornwell B, Laumann EO, & Schumm LP (2008). The social connectedness of older adults: A national profile. American Sociological Review, 73, 185–203. doi: 10.1177/000312240807300201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covinsky KE, Lindquist K, Dunlop DD, & Yelin E (2009). Pain, functional limitations, and aging. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 57, 1556–1561. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02388.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong Gierveld J & Broese van Groenou M (2016). Older couple relationships and loneliness. In Bookwala J (Ed.), Couple relationships in the middle and later years: Their nature, complexity, and role in health and illness (57–76). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- de Jong Gierveld J, Broese van Groenou M, Hoogendoorn AW, & Smit JH (2009). Quality of marriages in later life and emotional and social loneliness. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 64, 497–506. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbn043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnellan WJ, Bennett KM, & Soulsby LK (2017). Family close but friends closer: Exploring social support and resilience in older spousal dementia carers. Aging & Mental Health, 21, 1222–1228. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2016.1209734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurung RA, Taylor SE, & Seeman TE (2003). Accounting for changes in social support among married older adults: Insights from the MacArthur Studies of Successful Aging. Psychology and Aging, 18, 487–496. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.18.3.487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagedoorn M, Sanderman R, Buunk BP, & Wobbes T (2002). Failing in spousal caregiving: The ‘identity-relevant stress’ hypothesis to explain sex differences in caregiver distress. British Journal of Health Psychology, 7, 481–494. doi: 10.1348/135910702320645435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF (2015). An index and test of linear moderated mediation. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 50, 1–22. doi: 10.1080/00273171.2014.962683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh N, & Hawkley L (2018). Loneliness in the older adult marriage: Associations with dyadic aversion, indifference, and ambivalence. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 35, 1319–1339. doi: 10.1177/0265407517712480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HK, & McKenry PC (2002). The relationship between marriage and psychological well-being: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Family Issues, 23, 885–911. doi: 10.1177/019251302237296 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Korporaal M, Broese van Groenou MI, & van Tilburg TG (2008). Effects of own and spousal disability on loneliness among older adults. Journal of Aging and Health, 20, 306–325. doi: 10.1177/0898264308315431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavela SL, & Ather N (2010). Psychological health in older adult spousal caregivers of older adults. Chronic Illness, 6, 67–80. doi: 10.1177/1742395309356943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin D, Vagenas D, Pachana NA, Begum N, & Dobson A (2010). Gender differences in social network size and satisfaction in adults in their 70s. Journal of Health Psychology, 15, 671–679. doi: 10.1177/1359105310368177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moorman SM (2016). Dyadic perspectives on marital quality and loneliness in later life. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 33, 600–618. doi: 10.1177/0265407515584504 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK & Muthén BO (1998–2017). Mplus User’s Guide, Eighth Edition. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Neff LA, & Karney BR (2005). Gender differences in social support: A question of skill or responsiveness? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88, 79–90. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.1.79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng M, & Lin J (2016). Testing for mediation effects under non-normality and heteroscedasticity: A comparison of classic and modern methods. International Journal of Quantitative Research in Education, 3, 24–40. doi: 10.1504/IJQRE.2016.073643 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park NS, Jang Y, Lee BS, Haley WE, & Chiriboga DA (2013). The mediating role of loneliness in the relation between social engagement and depressive symptoms among older Korean Americans: Do men and women differ? Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 68, 193–201. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbs062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peerenboom L, Collard RM, Naarding P, & Comijs HC (2015). The association between depression and emotional and social loneliness in older persons and the influence of social support, cognitive functioning and personality: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 182, 26–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.04.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penninx BW, Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Simonsick EM, Deeg DJ, & Wallace RB (1998a). Depressive symptoms and physical decline in community-dwelling older persons. JAMA, 279, 1720–1726. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.21.1720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penninx BW, Van Tilburg T, Boeke AJP, Deeg DJ, Kriegsman DM, & Van Eijk JTM (1998b). Effects of social support and personal coping resources on depressive symptoms: Different for various chronic diseases? Health Psychology, 17, 551–558. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.17.6.551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza JR, Charles ST, & Almeida DM (2007). Living with chronic health conditions: Age differences in affective well-being. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 62, P313–P321. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.6.P313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Curran PJ, & Bauer DJ (2006). Computational tools for probing interactions in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. Journal of educational and behavioral statistics, 31, 437–448. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Rucker DD, & Hayes AF (2007). Addressing Moderated Mediation Hypotheses: Theory, Methods, and Prescriptions. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 42(1), 185–227. doi: 10.1080/00273170701341316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied psychological measurement, 1, 385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Robles TF, Slatcher RB, Trombello JM, & McGinn MM (2014). Marital quality and health: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 140, 140–187. doi: 10.1037/a0031859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rook KS (2015). Social networks in later life: Weighing positive and negative effects on health and well-being. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 24, 45–51. doi: 10.1177/0963721414551364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell CJ, & Dean MA (2000). To log or not to log: Bootstrap as an alternative to the parametric estimation of moderation effects in the presence of skewed dependent variables. Organizational Research Methods, 3, 166–185. doi: 10.1177/109442810032002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Russell DW (1996). UCLA Loneliness Scale (Version 3): Reliability, validity, and factor structure. Journal of personality assessment, 66, 20–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santini ZI, Fiori KL, Feeney J, Tyrovolas S, Haro JM, & Koyanagi A (2016). Social relationships, loneliness, and mental health among older men and women in Ireland: A prospective community-based study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 204, 59–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.06.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw BA, Krause N, Liang J, & Bennett J (2007). Tracking changes in social relations throughout late life. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 62, S90–S99. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.2.S90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TW, & Baron CE (2016). Marital discord in the later years. In Bookwala J (Ed.), Couple relationships in the middle and later years: Their nature, complexity, and role in health and illness (37–56). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Stokes JE (2017). Marital quality and loneliness in later life: A dyadic analysis of older married couples in Ireland. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 34, 114–135. doi: 10.1177/0265407515626309 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stronge S, Overall NC, & Sibley CG (2019). Gender differences in the associations between relationship status, social support, and wellbeing. Journal of Family Psychology, 33, 819–829. doi: 10.1037/fam0000540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walen HR, & Lachman ME (2000). Social support and strain from partner, family, and friends: Costs and benefits for men and women in adulthood. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 17, 5–30. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace RB, & Herzog AR (1995). Overview of the health measures in the Health and Retirement Study. Journal of Human Resources, S84–S107. [Google Scholar]

- Warner DF, & Adams SA (2012). Widening the social context of disablement among married older adults: Considering the role of nonmarital relationships for loneliness. Social Science Research, 41, 1529–1545. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2012.05.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner DF, Adams SA, & Anderson RK (2018). The good, the bad, and the indifferent: Physical disability, social role configurations, and changes in loneliness among married and unmarried older adults. Journal of Aging and Health. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1177/0898264318781129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner DF, & Kelley-Moore J (2012). The social context of disablement among older adults: Does marital quality matter for loneliness? Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 53, 50–66. doi: 10.1177/0022146512439540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong JS, & Hsieh N (2017). Functional status, cognition, and social relationships in dyadic perspective. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 74, 703–714. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbx024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yee JL, & Schulz R (2000). Gender differences in psychiatric morbidity among family caregivers: A review and analysis. The Gerontologist, 40, 147–164. doi: 10.1093/geront/40.2.147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]