Abstract

The cellular and molecular mechanisms that drive neurodegeneration remain poorly defined. Recent clinical trial failures, difficult diagnosis, uncertain etiology, and lack of curative therapies prompted us to re-examine other hypotheses of neurodegenerative pathogenesis. Recent reports establish that mitochondrial and calcium dysregulation occur early in many neurodegenerative diseases (NDDs), including Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson’s disease, Huntington's disease, and others. However, causal molecular evidence of mitochondrial and metabolic contributions to pathogenesis remains insufficient. Here we summarize the data supporting the hypothesis that mitochondrial and metabolic dysfunction result from diverse etiologies of neuropathology. We provide a current and comprehensive review of the literature and interpret that defective mitochondrial metabolism is upstream and primary to protein aggregation and other dogmatic hypotheses of NDDs. Finally, we identify gaps in knowledge and propose therapeutic modulation of mCa2+ exchange and mitochondrial function to alleviate metabolic impairments and treat NDDs.

Keywords: Mitochondria, Metabolism, Calcium, Neurodegeneration, Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson's disease, Huntington's disease

Introduction

The brain consumes 20% of the body’s ATP at rest, although it accounts for only 2% of body mass [1]. The high-energy requirements of the brain support neurotransmission, action potential firing, synapse development, maintenance of brain cells, neuronal plasticity, and cellular activities required for learning and memory [2, 3]. In neurons, most of the energy is consumed for synaptic transmission. Action potential signaling represents the second-largest metabolic need, and it is estimated that ~ 400–800 million ATP molecules are used to reestablish the electrochemical gradient (Na+ out, K+ in, at the plasma membrane) after production of the single action potential [4]. The energetic demand of neurons results in a substantial dependence on mitochondria for ATP production through oxidative phosphorylation (OxPhos) [4]. Any dysfunction in mitochondria can lessen the energetic capacity of OxPhos and may elicit a metabolic switch from OxPhos to glycolysis (Warburg-like effect) as a compensatory attempt to maintain cellular ATP in the context of neurodegenerative stress [5, 6]. However, a long-term OxPhos-to-glycolysis shift can result in a bioenergetic crisis and make neurons more vulnerable to oxidative stress and neuronal cell death [7, 8].

Neurodegenerative diseases (NDDs) are characterized by numerous cellular features, including the loss of neurons, neuronal dysfunction in specific brain regions, aggregation of distinct protein(s), impaired protein clearance, mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, axonal transport defects and cell death. The myriad of cellular pathologies suggest that there are common/central molecular mechanisms driving NDDs [9, 10]. In addition to ATP production, the mitochondrion is an epicenter of many metabolic pathways and important cellular functions, including the fine-tuning of intracellular calcium (iCa2+) signaling, regulation of cell death, lipid synthesis, ROS signaling, and cellular quality control [11]. Disruption in mitochondrial function and metabolism appears to underlie several NDDs such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease (PD), Huntington’s disease (HD), and others [12, 13]. At present, most therapies for NDDs provide only symptomatic relief, and there remain no drugs to inhibit neurodegeneration [14–16]. Mitochondrial alterations/impaired brain energetics are thought to present in the asymptomatic stage of disease prior to the onset of clinical symptoms [14, 17, 18]. This supports the notion that mitochondrial metabolic defects may be drivers or even initiators of the neurodegenerative process. In addition, several therapeutics that improve mitochondrial function have been reported to be efficacious in NDD models [19–21].

Mitochondrial calcium (mCa2+) is a critical regulator of mitochondrial function. In the matrix, mCa2+ tightly regulates TCA cycle activity and augments metabolic output. However, an excess of mCa2+ can impair mitochondrial respiration, enhance reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and activate cell death [22]. Here, we hypothesize that dysfunction in mCa2+ is an early common cellular event that impairs mitochondrial metabolism and drives and exacerbates neuropathology. Defining the molecular basis of mitochondrial function and metabolism in NDDs will help define novel cellular events and pathways and their temporal occurrence in NDD progression to identify new therapeutic targets for various neurological conditions. Here, we review recent advancements in our understanding of the essential role of mitochondrial metabolism and discuss how impaired mCa2+ signaling may be causal and central in neurodegeneration.

Evidence for impaired mitochondrial metabolism in NDDs

Strategies to combat NDDs have generally been unsuccessful and are focused on reducing symptoms and disease modification. Both clinical and experimental studies suggest that impaired energy metabolism correlates with various neurological deficits, highlighting new therapeutic opportunities [14]. Here we outline various mitochondrial metabolic defects that are strongly linked to the progression of neurodegeneration.

Alzheimer’s disease (AD)

AD is the most common form of dementia and is characterized by irreversible memory loss due to neuronal dysfunction, dysconnectivity, and cell death. Familial AD (FAD) is caused by pathogenic mutations in amyloid precursor protein (APP) or presenilin (PS1 and PS2) that lead to overproduction, improper cleavage, and the accumulation of amyloid-beta (Aβ). Prognostic disease phenotypes are associated with the formation of Aβ plaques, neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs, consisting of the microtubule protein tau), synaptic failure, reduced synthesis of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine, and chronic inflammation [9]. Most therapeutic strategies have been focused on Aβ metabolism and clearance due to extensive preclinical and clinical data in support of a causal role in AD progression [23, 24]. According to the “amyloid cascade hypothesis,” Aβ aggregation can initiate a series of events, including tau pathology, oxidative stress, inflammation, neuronal calcium (Ca2+) dysregulation, and metabolic alterations, which culminate in neuronal cell loss and AD pathogenesis [25]. However, this hypothesis does not fully explain the etiology of sporadic forms of AD (SAD) that account for 90–95% of AD-associated dementia.

An alternative hypothesis is that the microtubule-associated protein tau becomes hyperphosphorylated, resulting in axonal transport defects of organelles (including mitochondria), synaptic dysfunction, and cell death [26]. In cortical brain tissue from AD patients and mouse models, tau is reported to interact with mitochondrial transporters and complexes, resulting in mitochondrial dysfunction and AD pathology [27, 28]. However, there appears to be a limited correlation between the severity of cognitive decline and amyloid or tau plaque formation [29, 30], suggesting Aβ/tau metabolism and processing may not be the cause, or at least the singular cause, of disease. Consistent with previous studies, RNA-sequencing data from AD patients also suggest that Aβ and tau accumulation may not be mediators of the disease [31, 32]. Also, clinical trials of therapies targeting Aβ/tau production, metabolism, and clearance have universally shown little efficacy making it likely that other proximal mechanisms of AD pathogenesis exist [33, 34].

Mitochondrial dysfunction appears to be a primary occurrence in AD that precedes Aβ deposition, synaptic degeneration, and NFTs formation. In support of this concept, cytoplasmic hybrid cells (cybrids) generated from platelet mitochondria of SAD patients were reported to have a deficiency in complex I and complex IV of the electron transport chain (ETC), reduced mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm), altered mitochondrial morphology, increased Aβ generation and tau oligomerization (reviewed in [35]). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) showed smaller mitochondria with altered cristae structure and a decrease in mitochondrial content both in AD mice and patients [36–38]. Furthermore, fibroblasts derived from SAD patients also showed impaired mitochondrial dynamics, bioenergetics, and Ca2+ dysregulation [17, 39]. This change in mitochondria morphology in AD may be due to a shift in the mitochondrial fission/fusion balance and a decrease in biogenesis [40].

Importantly, experimental evidence suggests that bioenergetic alterations in AD precede the formation of Aβ plaques [41]. Data supporting metabolic deficits in AD were first published in the early 1980s from 2-[18F] fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET) studies, which showed reduced glucose metabolism in the parietal, temporal and frontal cortex of AD patients [42–44]. Postmortem brain tissue isolated from AD patients displays reduced mitochondrial metabolic enzyme activity for pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) [45, 46], alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase (α-KGDH) [46], isocitrate dehydrogenase (ICDH) [47], and complex IV or cytochrome-c-oxidase (COX) [48–50]. In addition, succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) and malate dehydrogenase (MDH) activity are increased in AD patient's brains [51]. Microarray data [52] and bioinformatics analysis of four transcriptome datasets [53] suggests a significant downregulation in nuclear-encoded OxPhos genes in the hippocampus of AD patients. More recent data confirm impaired ATP synthase activity due to loss of the oligomycin sensitive conferring protein subunit in the brain of FAD and SAD patients [54].

Diminished PDH function, as noted in AD, limits the shuttling of pyruvate into the TCA cycle, causing pyruvate accumulation and favoring anaerobic metabolism. Anaerobic metabolism leads to the production of lactic acid and further reduces acetyl-CoA availability, which subsequently decreases OxPhos. These observations suggest a metabolic shift from OxPhos to glycolysis may occur with AD progression. This shift is perhaps a compensatory response to enhance energy production through glycolysis, which is noteworthy in the context of mitochondrial dysfunction [5, 6]. Interestingly, PDH, α-KGDH, and ICDH activity are all reported to be calcium-controlled, suggesting a clear link between mCa2+ levels and AD pathogenesis, which will be discussed in the upcoming section. A recent study also indicates that reduced mitochondrial pyruvate uptake in FAD-PS2-expressing cells may elicit impairments in bioenergetics and mitochondrial ATP synthesis [13]. The mechanism for defective mitochondrial pyruvate flux is associated with the hyper-activation of glycogen-synthase-kinase-3β (GSK3β), which decreases hexokinase 1 association with mitochondria and destabilizes the mitochondrial pyruvate carrier complexes [13]. Similarly, α-KGDH is sensitive to oxidative stress, and its reduced activity in PS1 mutant (M146L) fibroblasts suggests a possible mechanism for ROS-dependent metabolic deficiencies [18, 55]. Oxidative stress, as seen in AD brains [56], is reported to increase the expression of SDHA (one of the four nuclear-encoded subunits of complex II, SDH) [57, 58], and the activity of MDH [59]. In summation, alterations in key metabolic enzymes may compromise the neurons’ ability to generate ATP via OxPhos and be an early driver of cellular stress in AD.

Beyond energetic compromise, diminished acetyl-CoA supply caused either by a reduction in glucose metabolism or by reduced PDH activity impairs the synthesis of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine (ACh). ACh is generated from choline and acetyl-CoA by choline acetyltransferase. After synthesis, ACh is transported via an ATP-consuming process and stored in synaptic vesicles [60]. The loss of ACh synthesis in AD results in defective cholinergic neurotransmission [61, 62]. This provides another tangible link between energetic compromise and neuronal dysfunction in AD.

Several of the mitochondrial dehydrogenases mentioned above (PDH, α-KGDH, and ICDH) are known to be regulated by the Ca2+ concentration within the mitochondrial matrix [63–65]. The reactions catalyzed by the Ca2+-regulated mitochondrial dehydrogenases are rate-limiting steps in the TCA cycle, and therefore free-Ca2+ content in the mitochondrial matrix is a major regulator of metabolic output. PDH activity increases upon dephosphorylation of its E1α subunit, which is mediated by the Ca2+-sensitive phosphatase (PDP1) [64]. In neurons, Ca2+ influx through voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels is required for the fusion of synaptic vesicles with the plasma membrane and release of neurotransmitters at the synaptic cleft [66, 67]. Neuronal communication through synaptic transmission is an energy-demanding process, and mitochondria have a critical role in this process by providing ATP (via OxPhos) and by buffering synaptic Ca2+/iCa2+ to modulate neurotransmitter release [68]. The efficient regulation and buffering of iCa2+ is critical to prevent neuronal excitotoxicity. Mitochondria and the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) both are significant modulators of iCa2+ signaling and the role of ER in neuronal iCa2+ buffering is well known [69, 70]. However, our understanding of mCa2+ buffering in neurons is limited and evolving. Ca2+ enters the mitochondrial matrix through the mitochondrial calcium uniporter channel (mtCU) [71, 72] and is extruded via the mitochondrial Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (NCLX) [73, 74]. Any dysfunction in mCa2+ exchange or matrix buffering capacity can lead to impairments in mitochondrial Ca2+ homeostasis resulting in mCa2+ overload, oxidative stress, metabolic dysfunction, and cell death that can cause or precede AD-pathology [75–78]. We and others have reported that mitochondrial and metabolic dysfunction is a primary contributor to AD pathogenesis, with dysfunction observable before the appearance of Aβ aggregates and NFTs [18, 77, 79, 80]. We found alterations in the expression of mCa2+ handling genes in samples isolated from the brains of SAD patients post-mortem and in the triple transgenic mouse model of AD (3xTg-AD) prior to observable AD pathology [77]. Our observations suggest mCa2+ overload caused by an age-dependent remodeling of mCa2+ exchange machinery contributes to the progression of AD by promoting metabolic and mitochondrial dysfunction. We also found a decrease in OxPhos capacity in APPswe cell lines (K670N, M671L Swedish mutation), providing further evidence of impaired mitochondrial metabolism in AD [77]. Importantly, the genetic rescue of neuronal mCa2+ efflux capacity by expression of NCLX in 3xTg-AD mice was sufficient to block age-dependent AD-like pathology [77]. Employing quantitative comparative proteomics strategies in AD mice, other groups have reported significant alterations in the mitochondrial proteome, including the citric acid cycle, OxPhos, pyruvate metabolism, glycolysis, oxidative stress, ion transport, apoptosis, and mitochondrial protein synthesis well before the onset of the AD phenotype [79–81]. Further evidence of mCa2+ dysregulation is from metabolomics in an Aβ-transgenic C. elegans model (GRU102), wherein the authors showed a reduction in TCA cycle flux before the appearance of significant Aβ deposition, with the greatest reduction observed in α-KGDH activity. Knockdown of α-KGDH in control worms elicited reductions in both basal and maximal respiration like that observed in the AD worm model [18]. These observations suggest that reduced α-KGDH activity alone is sufficient to recapitulate the metabolic deficits observed in AD and is in line with a study by Yao et al. [46] wherein 3-month old 3xTg-AD mice were found to have reduced mitochondrial respiration and PDH activity, coupled with increased ROS generation [46]. Altogether, these data indicate that mCa2+ dysregulation is likely an early event in AD.

Mitochondria are highly dynamic, and exhibit cell type-specific metabolism in the brain [37, 82]. Axonal mitochondria appear small and sparse whereas dendritic mitochondria are elongated and more densely packed [82]. To ensure appropriate energy supply, especially in distal regions of the axons, mitochondria must be properly positioned. Indeed, mitochondria undergo bi-directional axonal transport including anterograde transport (from cell body to axon) and retrograde transport (from axon to cell body) [83, 84]. Axonal transport is mediated by ATP‐hydrolyzing motor proteins (kinesin‐I for anterograde and dynein for retrograde) to move cargo along microtubule tracks [85] and defects in transport seem to present before evident AD hallmarks [86, 87]. Defects in anterograde transport result in an insufficient supply of ATP at the synapse, resulting in synaptic starvation and dysfunction, an early pathological feature of AD [36]. Similarly, defective retrograde transport can lead to the accumulation of damaged mitochondria, which can compromise mitochondrial quality control mechanisms, which is also noted to occur in AD [88]. Recently, data from the APP-PS1 mouse model showed a reduction in neuronal mitochondria density around amyloid plaques, suggesting impaired mitochondrial transport and/or quality control in AD [37]. Further, several studies indicate that axonal transport of AD-associated proteins becomes defective early in disease progression, resulting in the accumulation of toxic cargo which can elicit protein aggregation, axonal swellings, and neuronal dysfunction [36, 87]. The mechanisms regulating axonal transport are not completely understood but some studies suggest that it is mediated by the interaction of kinesin motor protein with the mitochondrial adaptor proteins, Miro and Milton (known as trafficking kinesin protein (TRAK) family) [89]. Miro is a GTPase with two Ca2+ binding EF-hand domains and is localized to the outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM) and has an essential role in Ca2+-dependent regulation of mitochondrial transport. Intriguingly, Miro1 may also serve as a cytoplasmic Ca2+ sensor and may increase mCa2+ uptake via interaction with MCU’s N-terminal domain [90, 91]. An increase in mCa2+ has been shown to inhibit mitochondrial axonal transport and blocking mCa2+ influx into mitochondria by direct MCU inhibition enhances mitochondrial trafficking in axons [90].

While multiple molecular mechanisms likely contribute to AD pathogenesis, the data suggest that neuronal mCa2+ overload is a primary mediator of AD progression, causing impaired mitochondrial metabolism and ATP production, mitochondrial transport, and increased mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) opening (Fig. 1). This in turn results in loss of synaptic function, amyloid deposition, tau pathology, and cell death.

Fig. 1.

Hypothetical mechanisms of mCa2+ overload-induced cellular dysfunction in AD progression. Loss of NCLX and remodeling of the mtCU causes mCa2+ overload that leads to mPTP opening, loss of ATP, and interrupted axonal transport, resulting in AD progression

Parkinson’s disease (PD)

PD is the second most common NDD afflicing ~ 1% of the population above 60 years of age [92]. It is clinically characterized by both motor dysfunction such as tremor (involuntary shaking), bradykinesia (slowness of movements), rigidity (resistance to movement), and akinesia, as well as non-motor disturbances such as depression, anxiety, fatigue, and dementia. These symptoms are caused by a diminishment of the neurotransmitter dopamine due to degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in the pars compacta of the substantia nigra in the midbrain and the deposition of intraneuronal proteinaceous inclusions known as Lewy bodies that are mainly composed of α-synuclein [93]. Most PD cases are sporadic with no known singular cause. Familial PD is associated with mutations in many genes including: SNCA (α-synuclein) [94], PRKN (parkin) [95], PARK7 (DJ-1) [96], LRRK2 (leucine-rich repeat kinase 2) [97], and PINK1 (phosphatase and tensin homologue (PTEN)-induced kinase 1) [98]. Studies suggest that homozygous mutations in Parkin are the most common cause of juvenile PD, but their role in idiopathic PD is unclear. Mutations in Parkin are not reliably associated with Lewy body pathology. Post-mortem examination of patients with Parkin mutations shows a clinical phenotype of dopaminergic neuronal loss and gliosis but lacking Lewy body pathology. However, this remains controversial as a few case reports demonstrate the presence of Lewy pathology in patients with Parkin mutations. Further studies are needed to define if parkin and Lewy body pathology are in linear pathways (reviewed in [99]).

Drug therapy for PD is limited and is primarily focused on enhancing dopamine levels via administration of l-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (L-DOPA or Levodopa), which is metabolized to dopamine after crossing the blood–brain barrier [100, 101]. However, this therapy is only effective in the early stages of disease, and provides symptomatic relief with many adverse side effects, and is insufficient to block the progression of PD [15, 102], suggest a crucial need for new, effective therapies [103, 104]. Although the exact mechanisms of PD pathogenesis are not clear, many possible molecular events have been proposed to contribute to this process.

Mitochondrial dysfunction and impaired cellular bioenergetics have emerged as likely mechanisms driving PD pathogenesis in several studies [105, 106]. Dopaminergic neurons consume ~ 20-times more energy as compared to other neurons because of their anatomical structure (extensive long and branched axons), greater number of transmitter release sites, and their pacemaking activity [107]. The high-energetic demand of dopaminergic neurons makes them more susceptible to mitochondrial dysfunction and eventually to cell death in comparison to other neuronal cells [108, 109]. Defects in mitochondrial respiration are supported by findings of reduced glucose utilization in PD patients [110], as well as reduced pyruvate oxidation in fibroblasts derived from PD patients [111], which suggest reduced acetyl-CoA entry into the TCA cycle. The first study showing that defects in mitochondrial respiration may be causal in PD came in the early 1980s. In this study, experimental inhibition of complex I (NADH-ubiquinone reductase) of the ETC was sufficient to cause parkinsonism [112, 113]. This is consistently supported by observations of a profound reduction in ETC activity, mostly complex I, in the substantia nigra, platelets, and skeletal muscle of PD patients [114]. Furthermore, inhibitors of complex I, such as MPP+ (1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium), 6-hydroxydopamine, rotenone and annonacin all elicit PD-like phenotypes, suggesting that mitochondrial dysfunction is sufficient to promote neuronal dysfunction in PD [115–117]. Complex I is a key entry point for electrons into the respiratory chain and is responsible for ~ 40% of mitochondrial ATP production [118, 119]. In addition to complex I, a reduction in complex II and III activity and the mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) transcription factor, TFAM, has also been reported in PD patients [120–122]. Reduced ETC capacity in PD may cause a significant reduction in ATP [123] resulting in a cellular energy crisis that can impact various processes including: (1) ATP-dependent proton pumps that drive vesicular accumulation of dopamine [124, 125]; (2) axonal transport of cargo [126]; (3) mitochondrial dynamics (fusion, fission, turnover, biogenesis and transport) [127, 128]; and (4) ATP-dependent protein degradation systems (e.g. ubiquitin–proteasome and autophagy) [129, 130]. In addition, complex I and III deficiency in PD is linked with increased production of free radicals that further impair mitochondria function, drive protein aggregation and culminate in cell death [131–133]. Dopamine is very unstable and sequestered inside synaptic vesicles via the ATP-dependent vesicular monoamine transporter. If not sequestered, it is metabolized by monoamine oxidase to the toxic dopamine metabolite 3,4 dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde, which contributes to oxidative stress, mPTP opening, and dopaminergic neuronal cell death [134]. Over the past decades, many PD-associated genetic mutations have been found to elicit changes in mitochondrial function and metabolism, supporting the notion that mitochondrial dysfunction is implicated in neuronal cell loss associated with familial PD and vice versa [98]. Mutant α-synuclein localizes to the inner mitochondrial membrane [135] and inhibits complex I activity, and promotes oxidative stress [136]. The interaction of α-synuclein with mitochondria can result in cytochrome c release, increased mCa2+ levels, changes in mitochondrial morphology, and a decline in mitochondrial respiration. α-synuclein-mitochondrial interplay may also inhibit autophagic clearance and increase its aggregation propensity (reviewed in [137]).

A recent study suggested that mitochondrial impairments occur with Lewy body formation [138]. Furthermore, loss of function mutations in DJ-1 caused impairments in OxPhos, and complex I assembly resulting in decreased ATP production, oxidative stress, and increased glycolysis [139, 140]. These findings raise the possibility that mitochondrial dysfunction is causal in maladaptive protein aggregation. Furthermore, Parkin, as an E3 ubiquitin ligase, is directly involved in the proteasomal degradation of protein aggregates. It localizes to mitochondria and prevents cytochrome c release, mitochondrial swelling, and the accumulation of α-synuclein, which may protect dopaminergic neurons from mitochondrial and neuronal dysfunction [141–143].

Parkin and PINK1 are required for mitochondrial quality control [144, 145]; thus, loss of Parkin/PINK1 function is hypothesized to cause the accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria that impair neuronal function. Previous work revealed that PINK1 deficient neurons display reduced NCLX-dependent mCa2+ efflux resulting in matrix Ca2+ overload and subsequent mPTP opening, mitochondrial oxidative stress, lower Δψm, and diminished OxPhos [146]. Furthermore, fibroblasts derived from patients with PINK1 mutations also exhibited impaired mitochondrial metabolism, low Δψm, and low respiration, which was linked to reduced substrate availability [147]. In addition, the activation of NCLX via protein kinase A (PKA)-dependent phosphorylation of serine 258, a putative NCLX regulatory site, increases mCa2+ efflux and protects PINK-1 deficient neurons from mitochondrial dysfunction and cell death [148]. This paradigm fits with previous reports where mCa2+ overload caused by increased mCa2+ uptake (via ERK1/2-dependent upregulation of MCU) caused dendritic degeneration in a late-onset familial PD model (mutation in Leucine-Rich Repeat Kinase 2) [149], and a report of MCU overexpression eliciting excitotoxic cell death [78]. Along the same line, inhibition of MCU is protective in zebrafish models of PD [150, 151]. These findings suggest mCa2+ overload is a contributor to PD progression.

In summary, increasing evidence supports the centrality of impaired mitochondrial function and metabolism in both sporadic and familial PD, resulting in oxidative stress, ETC dysfunction, defective mitochondrial quality control, protein aggregation, progressive cellular dysfunction, and neurodegeneration.

Huntington's disease (HD)

HD is an autosomal-dominant neurodegenerative disease resulting from an expansion of cytosine–adenine–guanine (CAG) repeats (> 35 bp) within the coding sequence of the huntingtin gene (HTT). Mutant huntingtin protein (mHtt) is prone to proteolytic cleavage, misfolding, and aggregation. Clinically, HD is characterized by progressive motor, cognitive, and behavioral dysfunction largely due to the loss of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABAergic) medium spiny neurons in the striatum [152]. The energy impairment hypothesis of HD was first proposed in the early 1980s from clinical observations, which revealed deficits in brain glucose utilization and weight loss in HD patients [153, 154]. Consistently, compelling evidence from PET studies suggests decreased glucose utilization in HD brains [155, 156], suggesting a defect in metabolism. In addition, compared to a control population, pre-symptomatic HD children, with no manifest symptoms, revealed a lower body mass index suggesting energy dysregulation and impairments in anabolic growth [157].

In HD patients, many key enzymes of the TCA cycle and ETC display reduced expression, including PDH, SDH, complex II, III, and IV [158]. In addition, HD patients increase lactate production in the pre-symptomatic phase of HD, indicating a possible reduction in oxidative mitochondrial metabolism and metabolic shift from OxPhos to glycolysis [159–162]. Irreversible inhibition of SDH by chronic administration of 3-nitropropionic acid in both rodents and non-human primates elicited regional lesions in the striatum accompanied by HD-like pathology [163–165]. These results suggest that defects in key TCA cycle enzymes are sufficient to drive HD-pathology. Furthermore, treatment of an HD mouse model with coenzyme Q and creatine for energy supplementation resulted in increased longevity and improved motor function [166, 167], suggesting that improving mitochondrial function and cellular bioenergetics is a viable therapeutic approach to treat HD.

Various other changes in mitochondrial function have been reported in HD. Recently, an examination of HD patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) and differentiated neural stem cells revealed altered mitochondria morphology (round and fragmented structure), lower mitochondrial respiration, decreased ATP levels and complex III activity, activation of apoptosis, and increased glycolysis [168]. Proteomic analysis in undifferentiated human HD embryonic stem cells found a decrease in key proteins involved in the ETC before observable differences in huntingtin protein [169]. These studies suggest that mitochondrial function is impaired early in HD pathogenesis. Also, mitochondrial dysfunction is linked with glutamate-mediated excitotoxicity in HD, and this is linked to defects in mCa2+ homeostasis. Studies indicate early abnormalities in mCa2+ that contribute to HD pathology [170]. For example, mitochondria from HD patients have an increased probability of mPTP opening, mitochondrial swelling, oxidative stress, and mCa2+ overload [170, 171]. As in other NDDs, impaired axonal transport is also reported in HD [172] and may be caused by mitochondrial dysfunction and impaired ATP production. Overall, these findings support a prominent role for mitochondrial and metabolic defects in HD pathogenesis.

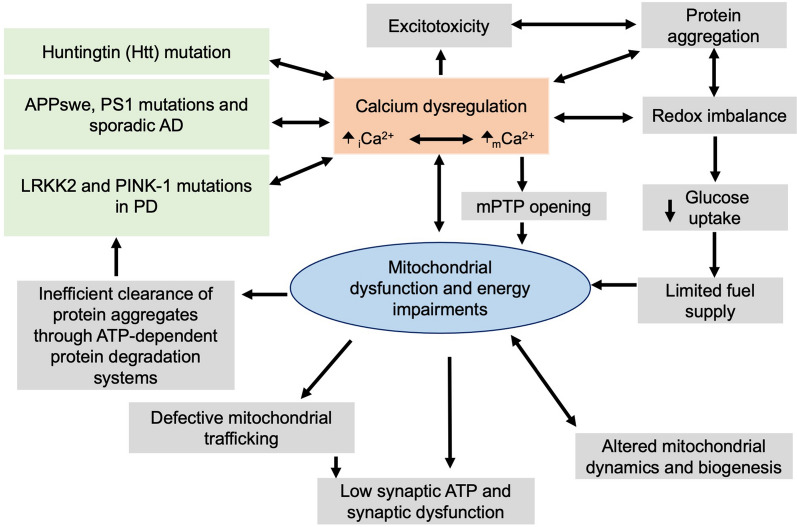

Altogether, numerous studies support that mitochondrial dysfunction and energy impairments occur before overt pathological symptoms and appear to be central in driving the progression of various NDDs. We hypothesize that metabolic and mitochondrial dysfunction is a result of iCa2+ dysfunction and remodeling of the mCa2+ exchange machinery, which, although initially meant to be compensatory, causes a series of events that culminate in neurodegeneration (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Mitochondrial and metabolic dysfunction in neurodegeneration. Mitochondrial dysfunction and energy impairments are central events in neurodegeneration

Molecular mechanisms of altered metabolism in NDDs

Above we outlined experimental evidence linking impaired energy metabolism to the initiation or progression of NDDs. This has led to the hypothesis that defects in mitochondrial energy production initiate a cascade of events that causes the neuronal cell death observed in NDDs [173]. However, additional work has raised the possibility that primary defects in other cellular processes may secondarily impair mitochondrial bioenergetics and contribute to NDD pathogenesis [10, 174]. Potential mechanisms that may alter metabolism in NDDs (Fig. 3), and the significance of such altered metabolism for NDDs etiology, are discussed below.

Fig. 3.

Calcium-centric view of impaired mitochondrial metabolism in NDDs. (1–2) An increase in intracellular calcium by different Ca2+ transport systems in the plasma membrane and the endoplasmic reticulum promotes its entry into the mitochondrial matrix via the mtCU. (3) mCa2+ enhances the activity of key TCA enzymes, leading to elevated OxPhos and ATP generation. On the other side, insufficient or excessive mCa2+ content can impair mitochondrial metabolism in NDDs. The ER plays a crucial role in regulating cellular energetics via the regulated release of Ca2+ near sites of ER-mitochondrial contact to support ATP production. (4) The changes in mitochondrial dynamics alter respiratory complex assembly and affect the coupling between respiration and ATP synthesis. (5–8) The production of ROS and activation of AMPK signaling by Ca2+ and insulin signaling also constitute the diverse array of signaling pathways that elicit transcription regulation of energy metabolism genes

Calcium signaling

Calcium signaling is required for neuronal function and regulates a range of processes, including neuronal excitability, neurotransmitter release, mitochondrial metabolism, and cell death. Tight control over iCa2+ flux is therefore essential for coordinated activity and neuronal homeostasis. As discussed above, altered Ca2+ homeostasis has been reported in NDDs and may contribute to neuronal dysfunction and death (reviewed in [175]). This section discusses the impact of altered Ca2+ handling in various subcellular compartments and its impact on metabolism.

Intracellular calcium

Perturbation of global iCa2+ homeostasis alters Ca2+ content in compartments, including the ER and mitochondria. Both organelles are implicated in the pathophysiology of NDDs, thus altered iCa2+ levels may contribute to NDD progression. Indeed, iCa2+ overload is a widely accepted feature of NDDs and is a likely cause of dysfunction and death of the neuronal populations affected by these diseases [176].

Elevated iCa2+ content is a common feature of AD and is especially pronounced in neurons containing NFTs [177]. Elevated iCa2+ in AD can exert detrimental effects by altering Ca2+-dependent signaling. Two examples of Ca2+-dependent proteins in neurons are the phosphatase calcineurin and Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII). Altered calcineurin and CaMKII signaling have been linked to memory impairment, synaptic loss, and neurodegeneration, all features of AD progression [178]. Such findings have inspired the “Ca2+ hypothesis of AD,” which proposes that cellular Ca2+ dysregulation is a central driver of disease progression [179, 180].

While Ca2+ dysregulation likely precedes neurodegeneration, several reports describe mechanisms by which Aβ directly elevates iCa2+ content, suggesting a vicious positive feedback loop that reinforces Ca2+ overload. First, Aβ can promote ROS production and subsequent oxidation of membrane lipids that can disrupt cellular ion transport [181]. Second, Aβ peptides may form Ca2+-permeable pores in the plasma membrane, allowing for direct influx of Ca2+ into the neuron [182]. This idea is supported by the observation that neurites with more Aβ have greater levels of iCa2+ [183]. Aβ is also proposed to stimulate Ca2+ uptake through L-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channels [184], but this notion is still debated [185]. Finally, Aβ may hyperactivate the NMDA receptor, leading to cellular Ca2+ overload [186]. Dysregulated Ca2+ handling is also implicated in the pathophysiology of PD [187]. Neurons with α-synuclein mutations have increased plasma membrane ion permeability, possibly due to the formation of pores by mutant α-synuclein [188]. Pharmacologic inhibition of Cav1.3 L-type Ca2+ channels is protective in animal models of PD [189], suggesting that increased ion channel activity contributes to excess iCa2+ entry. Store-operated calcium entry is also impaired in PD and leads to the depletion of ER Ca2+ content [175]. Likewise, neuronal Ca2+ dysregulation is a common feature of HD [190]. mHtt can stimulate NMDA receptors in medium spiny striatal neurons, potentially leading to excess iCa2+ [176]. Also, mHtt binds to and potentiates IP3 receptor signaling, enhancing Ca2+ release from the ER [191]. These combined effects all tend to deplete the ER of Ca2+ and can ultimately enhance store-operated Ca2+ entry [192], setting up a continuous cycle that promotes increased iCa2+ load.

ER calcium

Alterations in iCa2 handling in NDDs can cause secondary changes in ER Ca2+ load. The ER plays a critical role in regulating cellular energetics via the regulated release of Ca2+ near sites of ER-mitochondrial contact. In brief, these discrete sites of ER-mitochondrial apposition (examined further below under “MAMs” or mitochondrial associated membranes) create a microdomain where Ca2+ concentration can rise to levels as much as 20 × greater than in the bulk cytosol [193, 194]. This localized, high Ca2+ concentration is required for the activation of the mCa2+ uptake machinery (gating of the mtCU) and efficient ER-to-mitochondria Ca2+ transfer [195]. Inter-organelle Ca2+ transport is especially important in regulating iCa2+ homeostasis in neurons and is implicated not only in energetic homeostasis but also vesicle trafficking and neurotransmitter release [196, 197]. Thus, any structural disruption in ER-mitochondrial contact sites in NDDs and subsequent perturbation in ER-mitochondrial Ca2+ transfer has the potential to exacerbate iCa2+ stress and accelerate disease progression. Moreover, altered ER Ca2+ content and ER Ca2+ release will affect mCa2+ content. As discussed in the next section, either insufficient or excessive mCa2+ content can impair mitochondrial metabolism and signaling, thus underlying the significance of altered ER Ca2+ handling for cellular bioenergetics in NDDs.

Mitochondrial calcium

Given the central role of mCa2+ in regulating cellular metabolism and survival, it is not surprising that altered mCa2+ handling is reported in cellular NDD models. NDDs are universally associated with mCa2+ overload, which can impair cellular metabolism by inducing oxidative stress, which itself can impair OxPhos; and by inducing mPTP, which compromises ATP production by collapsing Δψm [198, 199].

In AD, mCa2+ overload can result from excessive ER-to-mitochondrial Ca2+ transfer induced by Aβ oligomers [200]. There are also reports that Aβ accumulates in mitochondria and interacts with the matrix mPTP regulator cyclophilin D, thus increasing permeability transition [201, 202] and impairing mitochondrial energetics in a Ca2+-independent manner. More recent results from our laboratory indicate that mCa2+ efflux is compromised in AD, due to downregulation of NCLX, which further promotes mCa2+ overload [77].

Signs of mCa2+ overload are observed in cellular models of PD induced by expression of mutant α-synuclein. These include loss of Δψm, cristae structure, and ATP content, features that are exacerbated by simultaneous expression of mutant PINK1 and rescued by pharmacologic blockade of mCa2+ uptake [203]. α-synuclein can accumulate within mitochondria and increases mCa2+ content, leading to increased ROS production [204]. However, conflicting reports [205] suggest that the effects of α-synuclein on mCa2+ homeostasis may be more nuanced. In some cases, α-synuclein may be beneficial by promoting ER-mitochondrial contacts to enhance ER-to-mitochondrial Ca2+ transfer and support mitochondrial bioenergetics [206]. Altered mCa2+ handling has been suggested in HD, but existing reports have yielded disparate conclusions on this point. The reader is referred to a recent review by Cali et al. [198] for a more detailed discussion.

Mitochondrial-associated membranes

Mitochondrial-associated membranes (MAMs) are regions where the ER is in close proximation with the outer mitochondrial membrane to allow crosstalk between these organelles. MAMs are particularly important for the exchange of Ca2+ and phospholipids, both of which impact ER/mitochondrial function and thus have profound effects on cellular metabolism and overall homeostasis (reviewed in [207]). MAMs are required for the synthesis of lipids such as phosphatidylcholine [208], with the mitochondrion serving as the site of phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) generation, an intermediate in phosphatidylcholine production. In turn, PE is crucial for overall mitochondrial morphology and function [209]. MAMs are also enriched for proteins involved in mitochondrial fission and fusion [210, 211], and so can influence mitochondrial dynamics, morphology, and biogenesis. Likewise, MAMs are important sites for the regulation of mitophagy and the clearance of defective mitochondria [212].

MAMs are often found at synapses, where they may modulate synaptic activity [213]. Efficient ER-to-mitochondria Ca2+ transfer is necessary for ATP production and may be especially important for meeting the high energetic demands of synaptic transmission [214] and/or serve as an important mechanism to buffer synaptic Ca2+. The ER and mitochondrial membranes are held in apposition at MAMs via a network of tether proteins [215, 216], some of which have been implicated in NDDs.

ER-mitochondrial tethers include the ER-mitochondria encounter structure (ERMES), which was identified in yeast [217]. Mammalian counterparts to the ERMES complex are still being validated, but may include the IP3 receptor, phosphofurin acidic cluster sorting protein-2 (PACS-2), B-cell receptor associated protein 31 (Bap31), PDZD8 in the ER, the mitochondrial fission protein Fis1, and the outer mitochondrial membrane protein VDAC [218]. PDZD8 is required for ER-mitochondria tethering, and loss of PDZD8 is sufficient to impact ER-mitochondrial Ca2+ dynamics in mammalian neurons [219]. Mitofusin 2 has also been proposed as a MAM tether [220], but this idea remains controversial [221, 222]. Additional proposed tethers include the oxysterol binding-related proteins ORP5 and ORP8, which can interact with mitochondrial protein tyrosine phosphatase interacting protein 51 (PTPIP51) [223]. The OMM protein synaptojanin 2 binding protein (SYNJ2BP) and the ER protein ribosome-binding protein 1 (RRBP1) are proposed to mediate specific interactions between the rough ER and mitochondria [224]. Finally, a tethering complex that may have particular importance in NDDs is comprised of the ER vesicle-associated membrane proteins-associated protein B (VAPB) and mitochondrial PTPIP51 [225, 226].

Altered ER-mitochondrial contacts in NDDs may contribute to disease pathology [227, 228]. Loss of MAM tethers can disrupt ER-mitochondrial Ca2+ transfer and so impair mitochondrial metabolism, leading to cellular energy depletion and the activation of autophagy [229, 230]. MAM disruption in NDDs could also lead to energetic compromise by impairing the synthesis of phospholipids important for mitochondrial membranes, such as cardiolipin [208, 231, 232]. This species is enriched in the mitochondrial inner membrane and is critical for proper ETC and ATP synthase function [233–236]. Finally, ER-mitochondrial associations regulate a number of processes that are commonly disrupted in NDDs such as Ca2+ handling, inflammation, axonal transport, and mitochondrial function [237]. These observations support the hypothesis that altered ER-mitochondrial communication is a common mechanism underlying NDDs.

The AD-related proteins APP and γ-secretase are all enriched at MAMs [238]. Observations of altered lipid metabolism and Ca2+ handling in both FAD and SAD suggest that these proteins may be associated with MAM dysfunction [228, 239]. Altered iCa2+ handling in AD could result from enhanced ER-mitochondrial Ca2+ transfer. The finding that ER Ca2+ concentration is increased in AD supports this view. Finally, altered lipid homeostasis resulting from dysfunctional ER/mitochondrial tethering may also impair mitochondrial energetics in AD. The MAMs of AD brain tissue and cells exhibit increased sphingomyelin hydrolysis by sphingomyelinase, which leads to increased ceramide content [240]. Increased ceramide content in AD appears sufficient to impair mitochondrial respiration [241, 242], as pharmacologic reduction of ceramide levels in AD models can rescue mitochondrial respiration [240]. Specific mechanisms by which elevated ceramide content in mitochondrial membranes may impair respiratory function and cellular bioenergetics have been detailed elsewhere [173].

Furthermore, altered ER-mitochondrial contacts and signaling are reported in PD, leading some to propose that disrupted MAMs are a significant contributor to PD pathogenesis [228, 237]. Proteins that are implicated in familial PD such as α-synuclein, PINK1, and Parkin all alter ER-mitochondrial signaling [243–245]. However, the specific consequences of these alterations on PD pathology are still the subject of active investigation [207].

The protein α-synuclein localizes to MAMs [245] and is thought to influence Ca2+ signaling [205, 206] and lipid metabolism [246], ultimately leading to defective ER and mitochondrial function [206]. Whereas wild-type α-synuclein promotes ER-mitochondrial contacts [206], the association of familial PD mutant α-synuclein with MAMs is disrupted. This change may represent one mechanism for compromised MAM structure and function in PD [246]. However, conflicting data suggest that overexpression of either wild-type or mutant α-synuclein can disrupt ER-mitochondrial contacts by binding to VAPB on the ER membrane and interfering with VAPB-PTPIP51 interactions [245]. Disruption of this tether complex can impair mitochondrial energetics because it compromises Ca2+ exchange between the two organelles [245]. Similar mechanisms may explain how DJ-1 mutations contribute to early-onset PD [247]. DJ-1 is normally localized to MAMs where it promotes ER-mitochondrial association and facilitates mCa2+ uptake [248]. Mutant DJ-1, as seen in PD, may disrupt MAM structure, ER-mitochondrial contacts, mCa2+ uptake, and mitochondrial bioenergetics [249]. In addition, mutations in Parkin and PINK1 may initiate PD pathogenesis via effects at MAMs. PINK and Parkin are recruited to sites of contact between ER and defective mitochondria to coordinate their autophagic clearance [244, 250]. Thus, defective PINK or Parkin may disrupt mitochondrial quality control mechanisms that rely on MAM interactions. Over time, this could impair cellular metabolism and contribute to PD pathology due to the accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria.

Mitochondrial structural defects

Mitochondrial structure is determined by a precise balance between mitochondrial fusion and fission and membrane dynamics that are mediated by several proteins including mitofusin 1 (MFN1), mitofusin 2 (MFN2), optic atrophy 1 (OPA1), dynamin-related protein 1 (DRP1), mitochondrial fission factor (MFF), and fission 1 protein [251]. During fasting or starvation mitochondria tend to fuse [252] due to inhibition of Drp1 by PKA and AMPK [253, 254]. These changes in mitochondrial structure alter respiratory complex assembly and affect the coupling between respiration and ATP synthesis [252], thereby increasing ATP production efficiency when fuel is scarce.

Defective mitochondrial fission and fusion have been implicated in NDDs [251], and abnormal mitochondrial structure and morphology are reported in AD, PD, and HD [255]. Increased mitochondrial fragmentation is often observed in these conditions. At first consideration, this finding might indicate that neurons in NDDs are well-supplied with metabolic fuels and are fully capable of breaking them down to meet cellular demands for ATP. However, increased mitochondrial fragmentation may instead reflect or even contribute to metabolic dysfunction in NDDs. Cells adapt to prolonged starvation or chronic defects in metabolism with increased mitophagy, which requires mitochondrial fragmentation [256]. Therefore, excess mitochondrial fragmentation may reflect increased stimuli for mitophagy in NDDs (i.e., impaired fuel utilization and/or mitochondrial dysfunction). This is perhaps coupled with impairments in the mitophagic machinery and the consequent accumulation of fragmented organelles. According to the model in which mitochondrial fusion enhances ATP production, a shift in mitochondrial dynamics that favors fission could limit mitochondrial bioenergetics and exacerbate metabolic stress in NDDs.

Several mechanisms are proposed to explain the accumulation of fragmented mitochondria in NDDs. In AD, some reports indicate that net mtDNA content and ETC protein expression are increased [257, 258], suggestive of a net increase in cellular mitochondrial content. This could occur with an increase in mitochondrial biogenesis and/or a decrease in clearance of defective, fragmented mitochondria. For example, APP mutant transgenic mice show upregulation of ETC genes, and Aβ has been shown to increase cellular mtDNA content [258, 259]. On the other hand, other studies report reduced mtDNA content and ETC gene expression in AD brains [260–262]. These disagreements likely reflect differences in the stage of disease examined in these reports. We observed a slight, but non-significant age-dependent decrease in mitochondrial content in AD-mice compared to control mice [77]. Finally, experiments in animal models of AD reveal increased S-nitrosylation of Drp1, which causes hyperactivation of Drp1 and excessive mitochondrial fragmentation [263]. Similar effects of hyperactivated Drp1 have been found in postmortem brain samples from AD patients [263].

The accumulation of fragmented mitochondria in PD could result either from primary mutations in PD-associated genes such as PINK and Parkin [264] or from the pathogenic milieu associated with disease progression. PINK and Parkin cooperate to identify defective mitochondria and target them for degradation via mitophagy [265]. Therefore, impaired clearance and eventual accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria may be a primary consequence of PD mutations. PINK1 also controls structural plasticity of mitochondrial crista junctions via phosphorylation of the inner mitochondrial membrane protein MIC60/mitofilin [266]. Mutation in PINK1 could impact the PINK1-Mic60 interaction and prevent the recruitment of Parkin to damaged mitochondria in PD. Further, excessive reactive nitrogen species (RNS) production in PD may contribute to the accumulation of fragmented mitochondria by modifying the activity of proteins involved in mitochondrial fission/fusion and mitophagy. For example, S-nitrosylation of Parkin decreases it E3 ubiquitin ligase activity [267], leading to stabilization of its target, Drp1, which promotes mitochondrial fission [268]. Similarly, S-nitrosylation of PINK1 can impair mitophagy [269] and thereby allow fragmented mitochondria to accumulate.

The mechanisms behind altered mitochondrial structure in HD have received less attention. Studies in a transgenic mouse model expressing mutant human HTT suggest a direct transcriptional repression of PGC1α, which could impair mitochondrial biogenesis [270]. Like in AD, increased S-nitrosylation and activation of Drp1 is observed in mouse models of HD [271], and causes excessive mitochondrial fragmentation similar to that seen in HD brains [272]. Recent work suggests that mutant HTT impairs mitophagy in neurons [273], which would also favor the accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria in HD.

Oxidative stress

Impaired metabolism in NDDs is linked to the production of RNS and ROS. Multiple hallmarks of NDDs including mitochondrial dysfunction, misfolded proteins, and inflammation are known consequences of elevated RNS/ROS production [274]. The relationship between mitochondrial dysfunction, aberrant ROS signaling, and neurodegeneration has been reviewed elsewhere [275]. Elevated RNS production in NDDs is thought to occur as a result of elevated iCa2+ concentration, which increases nitric oxide (NO) production by neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) and endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS). Excess NO in turn promotes mitochondrial dysfunction, which can exacerbate bioenergetic compromise and accelerate neurodegeneration [276]. This may occur through reversible S-nitrosylation of cysteine residues on proteins important for mitochondrial homeostasis such as Parkin and Drp1, as well as proteins such as Protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) that help to ensure proper protein folding (reviewed in [276]). Nitric oxide can also react with superoxide to form peroxynitrite, which irreversibly modifies tyrosine residues via tyrosine nitration [277].

Nitric oxide inhibits numerous proteins involved in metabolism, providing a mechanistic link between elevated iCa2+ levels and altered metabolism in NDDs. NO attenuates glycolysis and fatty acid oxidation via inhibitory S-nitrosylation of key enzymes in these pathways such as GAPDH [274, 276]. Such effects would impede metabolism by limiting carbon input into the TCA cycle. Furthermore, S-nitrosylation of the TCA cycle enzymes citrate synthase, aconitase, isocitrate dehydrogenase, alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase, succinyl-CoA synthetase, succinate dehydrogenase, and malate dehydrogenase has been observed [278, 279] and is often inhibitory [280, 281]. In particular, isocitrate dehydrogenase is a rate-limiting step within the TCA cycle [282], and inhibitory S-nitrosylation of this enzyme could limit TCA cycle flux and overall mitochondrial metabolism. Downstream of the TCA cycle, S-nitrosylation can inhibit ETC complexes I [283–285], IV [286], and V (ATP synthase) [287]. Tyrosine nitration also inhibits all ETC complexes [288, 289]. Thus, excessive RNS production in NDDs can impair mitochondrial metabolism by direct action on multiple targets and pathways.

Much remains to be determined regarding the specific role of mitochondrial RNS stress in the progression of NDDs. Some recent studies support a link between increased NO production and altered mitochondrial activity. Induced pluripotent stem cells expressing the A53T mutation in α-synuclein, which causes familial PD, exhibit decreased mitochondrial respiration that is attributed to aberrant S-nitrosylation of the transcription factor MEF2C, which leads to impaired PGC1α expression [290]. A similar effect of abnormal MEF2 S-nitrosylation is associated with neurodegeneration in AD [291]. Any initial impairment of mitochondrial respiratory activity can trigger excess ROS and RNS production, leading to further oxidative or nitrosative stress [112, 292, 293] that feeds back to impair mitochondrial metabolism. Fitting with this notion, increased ROS production by the ETC is indeed observed in neurodegeneration [274, 294]. While increased ROS production in NDDs may be a direct consequence of increased mCa2+ concentration, it is tempting to speculate that increased cellular NO production may also contribute to this effect by initiating ETC dysfunction.

Finally, it is worth noting that data also exist supporting a neuro-protective role for nitric oxide in some NDDs. As reviewed by Calabrese et al., within the context of normal physiology, NO can exert neuro-protective effects via several mechanisms including stimulation of pro-survival Akt and cyclic-AMP-responsive-element binding protein (CREB) signaling pathways, S-nitrosylation of the NMDA receptor to limit cellular Ca2+ uptake and excitotoxicity, inhibitory S-nitrosylation of caspases, and the upregulation of heme oxygenase 1 to stimulate cellular antioxidant production [295].

Transcriptional regulation

Several observations indicate that changes in transcriptional programs contribute to altered metabolism in NDDs. The expression of key energy and metabolism genes, such as components of the ETC, are reduced at both the mRNA and protein level in autopsied AD brains [262]. Furthermore, transcriptional repression of PGC-1α, a transcription coactivator with a central role in mitochondrial biogenesis, is observed in mouse models of HD [270]. These examples illustrate a general phenomenon, common to NDDs, of decreased transcription of genes involved in mitochondrial and oxidative metabolism [296]. Much work remains to determine the mechanisms responsible, but some evidence supports the notion that restoration of transcription is beneficial in NDDs. Specifically, activation of transcription factors including CREB, NF-κB, and NRF2 are protective in murine models of these diseases (reviewed in [174, 297]). It is interesting to note that exercise and aerobic activity can activate some of these neuroprotective transcription factors [174]. Thus, an interesting question is whether impaired locomotion and reduced physical activity in some NDDs diminish the activation of beneficial transcriptional programs, and so drive further transcriptional and metabolic defects.

One example of how metabolic gene transcription may become disrupted in NDDs is by impairment of Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)-γ co-activator 1α (PGC-1α). As reviewed elsewhere [298], PGC-1α is activated by AMPK during times of metabolic stress, and in concert with the transcription factor NRF-1 increases the expression of nuclear genes involved in mitochondrial biogenesis [299, 300]. PGC-1α also upregulates mitophagic genes [301, 302] and thus can impact mitochondrial quality control, turnover, and net mitochondrial content. NDDs are generally associated with reduced expression of PGC-1α, which likely represents a common mechanism for metabolic impairment in these diseases.

Reduced expression of PGC-1α is observed in Alzheimer’s patients and in the TG2576 mouse model of AD (transgenic expression of the APP Swedish mutation) [303]. Mutant forms of presenilin associated with familial AD are associated with reduced PGC-1α expression [304], while in vitro restoration of PGC-1α in AD cell lines improves overall function [303, 305]. This suggests that diminished PGC-1α function, and perhaps subsequent mitochondrial impairment, contributes to AD pathogenesis. Similar evidence for reduced PGC-1α activity is reported in Parkinson’s disease. PD patients exhibit reduced expression of PGC-1α target genes, such as components of the ETC [306]. In cell and animal models, loss of PGC-1α increases susceptibility to PD [307, 308], while overexpression of PGC-1α protects against neuronal death [306, 309]. Recent work indicates that the protein PARIS (ZFN746 gene), which is normally ubiquitinated by Parkin, can repress PGC-1α expression [310]. Thus, loss of Parkin in PD may elicit the accumulation of PARIS and downregulation of PGC-1α. In support of this notion, stereotactic injection of recombinant PARIS into the substantia nigra of mice causes neuronal death, but this is prevented by simultaneous injection of exogenous recombinant PGC-1α [310]. Together, these data support the idea that downregulation of PGC-1α is secondary to causative NDD gene mutations, but reduces mitochondria content and disrupts quality control, thereby furthering neuronal dysfunction and disease progression.

Huntington’s disease is more closely linked to defects in PGC-1α signaling than other NDDs. Deletion of PGC-1α in mice causes neurodegeneration and recapitulates symptoms of HD [311, 312], and induction of PGC-1α can rescue HD symptoms in mice[313]. Predictably, HD patients and mouse models display reduced PGC-1α expression and reduced expression of mitochondrial genes [314]. These features can be explained by binding of mutant huntingtin protein to the PGC-1α promotor, which represses PGC-1α transcription [270]. Deletion of PGC-1α in HD mouse models exacerbates neurodegeneration, whereas striatal overexpression of PGC-1α is sufficient to protect against neuronal atrophy [270]. Overall, PGC-1α likely plays a central role in the progression of NDDs, and so is an attractive therapeutic target.

Insulin signaling

Multiple studies support an association between altered insulin signaling and NDDs. Altered glucose metabolism is common in both AD and PD [174, 315], and both of these diseases are linked to type 2 diabetes [316–318]. Indeed, many of the same risk factors for developing obesity or diabetes (lack of physical activity, excess calorie consumption, etc.) predispose to the development of NDDs, especially AD and PD [319]. Variants in insulin signaling pathway genes, such as AKT [320] and GSK3β [321], increase the risk for PD. Thus, it is possible that diminished insulin responsiveness and impaired glucose utilization contribute to impaired neuronal metabolism in some NDD patients. This represents further evidence that a decline in metabolic health may initiate NDD development.

The glucose transporters GLUT1 (insulin-insensitive) and GLUT3 (insulin-sensitive) are decreased in AD brains [322, 323]. These changes may limit brain glucose uptake and contribute to cognitive impairments in AD [324]. A report that reducing GLUT1 expression in AD mouse models worsens amyloid burden, neurodegeneration, and cognitive function [325] supports this idea. Additionally, insulin deficiency favors phosphorylation of tau and the development of neurofibrillary pathology [326], reinforcing the notion that disrupted insulin signaling promotes AD progression.

In agreement, impaired glucose metabolism is a well-documented feature of PD brains [174], and lower levels of pyruvate oxidation are observed in PD fibroblasts [111]. These effects are recapitulated in animal models of PD [327–329] and may reflect impaired insulin signaling. Activation of AKT, a classical downstream target of insulin signaling, is reduced in the substantia nigra of PD brains and in in vitro cellular models of PD [330–333]. Genetic mutations in proteins linked to PD, including DJ-1 and PINK1, are also associated with diminished AKT signaling [334] and provide further evidence for altered insulin responsiveness in this disease. To the extent that altered insulin/AKT signaling limits carbon (i.e., glucose) metabolism within neurons, it would limit fuel input to the TCA cycle and decrease mitochondrial ATP production [335]. Limited mitochondrial energetics may be just one consequence of diminished glucose uptake or utilization in PD. Dopaminergic neurons do not tolerate glucose starvation [336], and glucose deprivation in vitro is sufficient to cause α-synuclein aggregation and death of dopaminergic neurons [337]. These data support the idea that impaired glucose utilization is an early driver of PD pathology, and may lead not only to impaired mitochondrial metabolism, but also to amyloidosis and neuronal death.

Altered glucose metabolism is an early feature of HD, even though the expression of glucose transporters is normal in initial stages of the disease [153, 338, 339]. This defect is explained by diminished localization of the glucose transporters at the neuronal plasma membrane [340]. Interestingly, defects in metabolism are observed prior to striatal atrophy, and reduced glucose metabolism strongly correlates with HD progression [341–343]. The finding that increasing expression of GLUT3 or enzymes involved in glucose metabolism can protect against the progression of HD [344, 345] strengthens this view.

AMPK

AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) is a master cellular energy sensor and has a critical role in maintaining metabolic homeostasis. AMPK is activated in response to changes indicative of energetic stress (e.g. increased AMP/ATP ratio, hypoxia, a drop in cellular pH, increased iCa2+ concentration, etc.) and via phosphorylation by the kinases LKB1, CaMKKβ, and TAK-1 (reviewed in [346, 347]). AMPK exerts multiple effects to stimulate ATP production, such as stimulating glucose uptake, glycolysis, and glucose and fatty acid oxidation, while at the same time limiting cellular ATP consumption by inhibiting fatty acid and cholesterol production [298, 347]. AMPK also promotes long-term increases in mitochondrial energy production by phosphorylating PGC-1α and the fork-head box O (FOXO) transcription factor to stimulate mitochondrial biogenesis [299, 300, 309, 348–351].

AMPK is activated by ROS, which as previously detailed are elevated in many NDDs [352, 353]. Since AMPK activation can exacerbate ROS production, this may set up a positive feedback loop leading to further oxidative stress and metabolic impairment [354]. Thus, AMPK has the potential to exert both positive and detrimental effects in NDDs. Data supporting both positive and negative aspects of AMPK activation exist for most NDDs, and the net positive versus detrimental outcomes of AMPK activation likely varies between different disorders.

Elevated AMPK activity has been reported in the brains of the APPswe/PS1dE9 and APPswe,ind, mouse models of AD [355, 356]. Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain how this occurs. First, any existing mitochondrial dysfunction due to Aβ accumulation [201, 357, 358], or decreased mitochondrial biogenesis and increased fragmentation [359], could cause energetic stress and AMPK activation. Second, Aβ causes excessive iCa2+ flux due to activation of the NMDA receptor, which can activate the AMPK-kinase, CaMKKβ [355, 360]. Third, elevated ROS production [201] and elevated iCa2+ [361] downstream of mitochondrial dysfunction can increase AMPK activity in AD. Finally, increased NADPH oxidase activity is observed in AD brains and is proposed to activate AMPK [362].

Although AMPK activation may initially be an adaptive response to alleviate energetic stress in AD, most data indicate that abnormal AMPK activation eventually turns detrimental. For example, AMPK can increase Aβ expression, and Aβ can further activate AMPK, which can suppress long-term potentiation and impair memory [298]. Similarly, AMPK activation increases the phosphorylation of tau [363] and reduces the binding of tau to microtubules [360, 363], potentially accelerating tauopathy. These effects help explain why pharmacologic inhibition of AMPK with compound C or genetic ablation of AMPKα2 subunits is beneficial in the APPswe/PS1dE9 mouse model of AD [364]. Further data in support of a detrimental role of AMPK in AD comes from studies showing that treatment of AD mice with the AMPK activator metformin results in transcriptional upregulation of β-secretase, leading to increased Aβ formation and worsened memory [365, 366]. These studies suggest that AMPK activity furthers metabolic impairment and AD progression by contributing to, or propagating, the pathogenic milieu. It is worth noting that some beneficial effects of AMPK activation have also been observed in AD models. In Drosophila, Aβ suppresses AMPK signaling [367], suggesting that insufficient rather than excessive AMPK activity may contribute to AD progression. Consistent with this notion, activation of AMPK by AICAR in rat cortical neurons decreases Aβ content, and knockout of the AMPKα2 subunit increases Aβ production [368]. AMPK activation in response to leptin signaling reduces tau phosphorylation [369, 370], and compounds that activate AMPK, such as resveratrol and metformin, stimulate Aβ metabolism, reduce mitochondrial dysfunction, and improve AD pathology [371–373]. The conflicting data regarding the beneficial versus detrimental roles of AMPK in AD may reflect disparities among the various models and cell types studied with respect to differential expression of AMPK subunit isoforms and their regulation, relative activity, and specific cellular targets, or may be due to temporal differences in disease progression.

AMPK likely also has divergent effects on energetics and neurodegeneration in PD depending on the model or stage of the disease [374]. AMPK is activated in mice treated with MPP+, a common in vivo model for PD, as well as in SH-SY5Y cells (human neuroblastoma cell line) treated with MPP+ in vitro [375]. The available data suggest that AMPK activation is beneficial and promotes cell survival [375, 376]. For example, pharmacologic inhibition of AMPK increases neuronal cell death in response to MPP+ treatment, whereas AMPK overexpression promotes cell survival [375]. In line with these findings, AMPK cooperates with Parkin to maintain mitochondrial quality control and promote neuronal survival [374]. However, the possibility of detrimental effects of AMPK activation to cellular energetics and survival in PD cannot be fully excluded. For instance, AMPK activation in response to cellular ATP depletion is implicated in the degeneration of dopaminergic neurons [377]. Thus, more work is needed to elucidate the precise role of AMPK activation in PD and clarify whether it promotes or impairs metabolic function and overall cellular viability.

The brains of HD patients and HD mouse models exhibit excessive AMPK activation [354, 378, 379]. Both mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress are reported in HD [380], and these defects may both contribute to AMPK activation, or vice-versa be consequences of excessive AMPK activity. mHtt protein likely initiates metabolic stress leading to downstream AMPK activation. mHtt can aggregate on mitochondrial membranes and disrupt mCa2+ flux, causing Ca2+-dependent oxidative stress [381, 382]. mHtt aggregates also decrease Complex II and Complex III activity [170, 383, 384] and impair mitochondrial trafficking [385]. All these effects can disrupt cellular energy balance and trigger AMPK activation. The existing literature suggests that AMPK activation is detrimental in HD, culminating in neuronal apoptosis [354, 379]. This effect may be related to the suppression of the survival gene Bcl-2 [379]. Whether excess AMPK activity is also toxic due to metabolic perturbations remains to be determined.

Neuroinflammation

Previous studies have indicated that optimal brain function requires coordinated signaling between neurons and glial cells, and disturbances in paracellular communication can contribute to NDDs development. In addition, the inflammatory hypothesis suggests that the activation of microglia is a driving force for neuroinflammation and mitochondrial dysfunction in NDDs. In turn, mitochondrial dysfunction can promote inflammation (reviewed in [386, 387]).

Microglia are specialized brain macrophages with a primary function in host defense including the removal of cellular debris, metabolic waste, pathogens, and neurotoxins [388]. Microglia are dynamic cells that can change their shape and undergo phenotypic transformation (activation) in response to infection or injury. In the resting homeostatic state, microglia exhibit a ramified structure with branching processes for surveillance of the local environment [389]. After activation, microglia become highly mobile, assuming an amoeboid form with short thickened processes, and phagocytose cell debris, secrete proinflammatory mediators, such as cytokines, and generate ROS to potentiate acute inflammation [389]. While thought to serve a protective role during acute inflammation, persistent microglia activation contributes to chronic neuroinflammation and redox imbalance associated with NDDs, resulting in mitochondrial dysfunction [390, 391]. This elicits a positive feedback loop where mitochondrial-generated superoxide potentiates microglial activation, initiating further ROS production. As previously discussed ROS can promote posttranslational modifications of TCA cycle enzymes and induce mtDNA mutations, which in turn can compromise energetics and trigger mitochondrial dysfunction [392].

Fuel sources are thought to be altered in NDDs, resulting in cell-specific metabolic shifts to maintain ATP production [393]. The minimal experimental data available suggests that similar metabolic pathway switching occurs during microglial activation. Transcriptomic studies suggest that microglia express all the required genes for OxPhos and glycolysis [394]. Limited data suggest that microglia undergo reprogramming during activation to favor glycolysis over OxPhos [395–397]. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) activation of transformed mouse microglial cells (BV-2 cells) decreased OxPhos and lowered ATP production with a concomitant increase in lactate production [397]. These observations are bolstered by the finding of increased lactate production and glucose uptake (high expression of GLUT1 and GLUT4) in activated microglia, favoring aerobic glycolysis and an increase in pentose phosphate pathway flux [396].

Multiple inflammatory mediators resulting from chronic neuroinflammation can affect mitochondrial energy metabolism and mitochondrial dynamics, thereby contributing to NDDs (reviewed in [387]). However, the direct molecular mechanisms are still not precise in neuronal and glial cells by which these inflammatory factors impact mitochondrial metabolism. Few reports in non-neuronal cells suggest that inflammatory mediators, TNF and IL-1β, reduce the activity of TCA cycle enzymes including PDH and α-KGDH, with a concurrent reduction in Complex I and II activity [398]. α-KGDH activity is reported to be reduced by an inflammation-derived oxidant, myeloperoxidase, that is upregulated in microglia in AD brain tissue [399]. This suggests that inflammatory factors can impact mitochondrial metabolism in glial cells in AD. In addition, TNF has been reported to reduce the expression of PGC-1α in non-neuronal cells [400]. However, the direct interplay between neuroinflammation and mitochondrial metabolism in different NDDs remains poorly understood and thus warrants further investigation.

Peroxisomal lipid metabolism

Metabolic dysregulation associated with peroxisome dysfunction may contribute to the development of NDDs. Peroxisomes are highly dynamic and important metabolic organelles that can directly communicate with mitochondria and contribute to cellular lipid metabolism, e.g., the oxidation of very-long-chain fatty acids (VLCFAs), synthesis of phospholipids, such as plasmalogen/ether lipids (myelin sheath lipids) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), and the regulation of redox and inflammatory signaling. Furthermore, the brain is a lipid-rich organ, and myelin sheaths are rich in plasmalogens/ether lipids synthesized in peroxisomes. Therefore, slight alterations in peroxisomal lipid metabolism may represent significant mechanisms contributing to changes in neuronal function (reviewed in [401]).

In AD, alternations in lipid homeostasis/peroxisome function include significantly decreased levels of plasmalogens and DHA and increased levels of VLCFA. The severity of these alternations correlates with the progression of disease [402, 403] and has been shown to change cell membrane properties and increase intracellular cholesterol levels. These changes increase β-secretase and γ-secretase activities, resulting in enhanced Aβ generation, tau hyperphosphorylation, synaptic dysfunction, and neuroinflammation [404, 405]. In addition, peroxisomal β-oxidation inhibition increased Aβ generation in rat brains (reviewed in [405]). Similarly, severe alterations in lipid composition (reductions in DHA and plasmalogens) of frontal cortex lipid rafts from PD patients have been reported [406]. Reductions in ether lipids decreased Ca2+-dependent neurotransmitter release and the respiratory capacity of synaptic mitochondria [407]. Therefore, it is possible that the decrease of ether lipids in mitochondrial membranes might disrupt OxPhos complexes and thus ATP generation sufficiently to compromise neurotransmission. However, overall the role of peroxisomal lipid metabolism in NDDs is poorly described. Further studies are required to determine whether peroxisomal lipid dysfunction directly contributes to disease etiology or is a secondary phenomenon. We refer the reader to another recent review for a detailed overview of the peroxisomal lipid metabolism in NDDs and its metabolic cooperation with mitochondria [405, 408].

Modulation of mitochondrial function as a possible therapeutic target for neurodegeneration

As discussed earlier, dysregulation in mCa2+ homeostasis might be an upstream event causing mitochondrial dysfunction in NDDs. For this reason, various combinations of modulators aimed at targeting or correcting defects in mCa2+ exchange or restoring mitochondrial function/energy metabolism may serve as therapies to prevent the development of NDDs. Possible therapeutic strategies, summarized in Table 1, include reducing mCa2+ uptake, enhancing mCa2+ efflux, and preserving mitochondrial architecture/functions (such as the assembly of respiratory chain complexes and the ATP synthase), bioenergetics, axonal transport of mitochondria, and mitochondrial proteostasis. However, it is still unclear whether increasing mCa2+ efflux or reducing mitochondrial mCa2+ uptake will be superior for neuroprotection. Both are sufficient to limit mCa2+ overload and correct mCa2+ dysregulation. Still, a few points need careful consideration, such as if modulators of mitochondrial mCa2+ homeostasis will negatively impact Ca2+-dependent physiological functions, such as TCA cycle flux and mitochondrial dynamics. It should also be noted that different NDDs might have disease-specific regulation of mtCU channel activity, which requires more detailed experimentation. Beyond this, cellular heterogeneity in mitochondrial function should also be considered; for example, axonal and synaptic mitochondria are reported to be involved in Ca2+ buffering and presynaptic transmission, whereas the soma is the primary site for mitochondrial quality control. Therefore, a proper understanding and regulation of the mtCU, or a combination of modulators that aim to increase mCa2+ buffer capacity and still maintain energetics may be necessary to maintain efficient synaptic transmission and effectively treat NDDs.

Table 1.

Potential mitochondrial targets for neurodegenerative therapy

| Possible mitochondrial targets | Function | Effect | Possible outcome | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mtCU-dependent mCa2+ influx | MCU inhibitor | MCU encodes the channel-forming portion of the mtCU complex, and loss of MCU completely ablates all channel function [71, 72] | Reduce mCa2+ uptake | Modulation of mtCU dependent mCa2+ uptake mechanisms can reduce pathogenic mCa2+ overload, maintain mitochondrial Ca2+ homeostasis and preserve structure and function |

| MCUB activator | MCUB, a paralog of MCU, exerts a dominant-negative effect and negatively regulates the mtCU by replacing MCU subunits [411] | |||

| MICU1 modulator | MICU1 prominently regulates the Ca2+ threshold of the mitochondrial calcium uniporter complex (mtCU) [412, 413] and modulates mitochondrial ultrastructure and cristae organization independent of mtCU [414] | |||

| MICU3 modulator | MICU3, a brain-specific regulator of mCa2+ uptake, act as an activator at low iCa2+ levels [415] | |||

| EMRE inhibitor | EMRE, an essential mtCU regulator and loss of EMRE will reduce overall mtCU formation [416] | |||

| mCa2+ efflux | NCLX activator | A mitochondrial Na+/Ca2+ exchanger acts as a primary route of Ca2+ efflux (3-Na+ in/1-Ca2+ out) (NCLX) [73, 74] | Enhance mCa2+ efflux | Enhancing mCa2+ efflux can reduce pathogenic mCa2+ overload and its associated mitochondrial dysfunction |