Abstract

Objective.

Sjögren’s syndrome (SS) and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) are related by clinical and serologic manifestations as well as genetic risks. Both diseases are more commonly found in women than in men, at a ratio of ~10 to 1. Common X chromosome aneuploidies, 47,XXY and 47,XXX, are enriched among men and women, respectively, in either disease, suggesting a dose effect on the X chromosome.

Methods.

We examined cohorts of SS and SLE patients by constructing intensity plots of X chromosome single-nucleotide polymorphism alleles, along with determining the karyotype of selected patients.

Results.

Among ~2,500 women with SLE, we found 3 patients with a triple mosaic, consisting of 45,X/46,XX/47,XXX. Among ~2,100 women with SS, 1 patient had 45,X/46,XX/47,XXX, with a triplication of the distal p arm of the X chromosome in the 47,XXX cells. Neither the triple mosaic nor the partial triplication was found among the controls. In another SS cohort, we found a mother/daughter pair with partial triplication of this same region of the X chromosome. The triple mosaic occurs in ~1 in 25,000–50,000 live female births, while partial triplications are even rarer.

Conclusion.

Very rare X chromosome abnormalities are present among patients with either SS or SLE and may inform the location of a gene(s) that mediates an X dose effect, as well as critical cell types in which such an effect is operative.

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and Sjögren’s syndrome (SS) are related by common autoimmune serology, clinical manifestations, and genetics, as well as a strong bias for the female sex. The sex bias for SLE is ~10 to 1 (1,2), while among those with SS, women are overrepresented by 10–15-fold (3).

Aneuploidy of the X chromosome is common in humans. Klinefelter’s syndrome (male 47,XXY) occurs in ~1 in 500 live male births, but 80% of these men remain undiagnosed (4). Moreover, 47,XXX is found in ~1 in 1,000 live female births, with only ~1% identified (5,6). We have found excess 47,XXY among men with either SLE (7,8) or SS (9), as well as excess 47,XXX among women with these diseases (10). On this basis, we have proposed an X chromosome dose effect for the sex bias of SLE and SS. Such a bias might be mediated by specific genes that escape X inactivation, by global escape of X inactivation in specific cell types (11), by interference with immune tolerance via increased production of X chromosome gene products (12), or by an effect on the immune system through the mosaicism of random X inactivation (13).

We previously described a man with 46,XX who was identified among 316 men with SLE (14). This X chromosome abnormality occurs in as few as 1 in 25,000–50,000 live-born boys. We undertook the present study to examine women with either SLE or SS for rare X chromosome aneuploidies.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients.

We studied a large cohort of SLE patients, ~60% of whom were of European heritage and ~40% of African heritage, who were gathered for genetic and other studies, as described in detail elsewhere (15). In addition, we studied a large cohort of patients with primary SS, all of whom did not meet the criteria for other autoimmune rheumatic diseases (16,17); those with secondary SS were excluded. Patients met the respective research classification criteria for each of the diseases (18,19). Women who were demonstrated not to have SLE or SS served as controls. As previously described (10), controls were screened for autoimmune rheumatic diseases, and none was identified.

X chromosome analyses.

The study subjects were screened for X chromosome abnormalities by examining intensity plots of X chromosome single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) alleles, as we have previously described (8,10). In these displays (so-called b plots), the fluorescent intensity of the b allele is divided by the intensity of the a and b alleles, which gives values of 1.0 for homozygous b SNPs, 0.5 for heterozygous ab SNPs, and 0.0 for homozygous a SNPs. However, a person with 3 X chromosomes will have b plot results of 0.33 for aab SNP alleles and 0.67 for abb alleles. Subjects with abnormal b plot results were then studied by examining the karyotype of peripheral blood mononuclear cells or by florescence in situ hybridization, as previously described (8). Some subjects were studied directly with karyotyping according to standard methods in a Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments-approved laboratory.

Statistical analysis.

We calculated binomial 95% confidence intervals for ratios. To calculate the prevalence of SLE among individuals with X triple mosaic, we used Bayes’ theorem as previously described (8). The following formula was used:

where P(B/A) is the prevalence of SLE among those with the triple mosaic, P(A/B) is the prevalence of the triple mosaic among SLE patients, P(B) is the prevalence of SLE in the population, and P(A) is the prevalence of the X triple mosaic in the population.

RESULTS

Among 2,426 women with SLE, we found 3 with the rare triple mosaic of 45,X/46,XX/47,XXX based on the b plots; these results were confirmed by G-band karyotyping of 50 cells (Table 1). These SLE patients had approximately the same ratio of cells with the abnormal X chromosome number: only 3% of cells were either 45,X or 47,XXX, while a large majority (~94%) carried 46,XX. In examination of their clinical records, there was no diagnosis or clinical evidence of Turner’s syndrome, abnormal sexual development, or infertility. Binomial 95% confidence intervals for the ratio 3 in 2,426 (0.0012 [1 in 809]) were 0.0003–0.0036 (1 in 3,333 to 1 in 278), which therefore did not include the estimated birth rate of 1 in 25,000 for 45,X/46,XX/ 47,XXX (5,20,21). Thus, we concluded that there is a statistically significant increase in the prevalence of the X chromosome triple mosaic among SLE patients.

Table 1.

Presence of an X chromosome triple mosaic in the SLE and SS patient cohorts and controls*

| Total no. assessed | No. with X triple mosaic |

Binomial 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | |||

| SLE cohort | 2,426 | 3 | 1 in 278 to 1 in 3,333† |

| SS cohort | 2,138 | 1 | 1 in 385 to 1 in 100,000 |

| Combined cohorts | 4,564 | 4 | 1 in 1,111 to 1 in 5,000† |

| Controls | 2,712 | 0 | NA |

Women who did not have systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) or Sjögren’s syndrome (SS) served as controls. The estimated birth rate for the triple mosaic (45,X/46,XX/47,XXX) is 1 in 25,000–50,000 live female births. NA = not applicable.

Neither part of the 95% confidence interval (95% CI) crosses the known birth rate of 45,X/46,XX/47,XXX, and thus, demonstrates a statistically significant result.

We used Bayes’ theorem to calculate the prevalence of SLE among women carrying the X triple mosaic. For this calculation, we assumed a prevalence of 1 in 1,000 for SLE, along with a prevalence of 1 in 25,000 for the X triple mosaic. The calculation predicted that 1 in 32 individuals with 45,X/46,XX/ 47,XXX will have SLE.

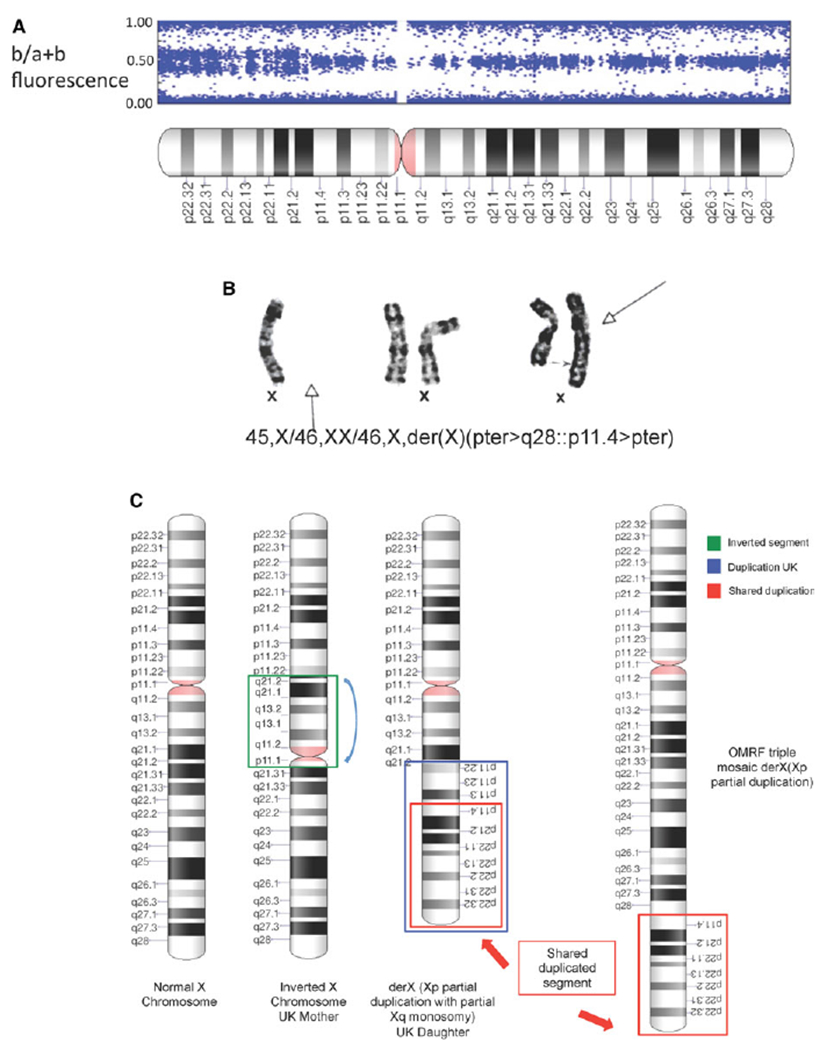

Among 2,138 women with SS, we did not find a subject with the X chromosome triple mosaic described above. Instead, when examining X chromosome b plots, we noted a single subject with a partial triplication of the X chromosome p arm. That is, distal Xp showed 4 intensity bands (at 0.0, 0.3, 0.6, and 1.0), indicating 3 copies of this portion of the X chromosome, but other areas of the X chromosome showed only 3 bands (at 0.0, 0.5, and 1.0). The latter is the pattern for 2 X chromosomes (Figure 1A). We obtained a blood sample from this subject and performed karyotyping, which showed a triple X chromosome mosaic, with 2 of 20 cells examined (10%) carrying 45,X and 13 of 20 cells (65%) carrying 46,XX, while 5 of 20 cells (25%) had a triplication of the distal portion of the p arm of the X chromosome (Figure 1B). This additional, triplicated portion of X consisted of a nonreciprocal translocation onto 1 of the X chromosomes: 47,XX+Xp. By karyotype, this abnormality was designated 45,X/46,XX/ 46,X,der(X)(pter>q28::p11.4>pter) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A, B plot of the X chromosome of a Sjögren’s syndrome (SS) patient. The distal aspect of the p arm demonstrates a 4-band pattern consistent with 3 copies of this portion of the X chromosome. The centromeric half of Xp and Xq demonstrates a 3-band pattern consistent with 2 copies of these portions of the X chromosome. The plot was constructed by dividing the fluorescent intensity of the b allele by the intensity of the a plus b alleles. B, Karyotype of the X chromosome of all 3 cell types found in the same SS patient. One normal X chromosome was found in 10% of cells (left), 2 normal X chromosomes were found in 65% of cells (middle), and 1 normal X chromosome along with an X chromosome with a nonreciprocal translocation of distal Xp was found in 25% of cells (right). Arrows indicate the missing X chromosome (solid arrow at far left), the junction of the normal X chromosome with triplicated Xp region (broken arrow at far right), and the abnormal X chromosome with the additional Xp segment (solid arrow at far right). Cytogenetic designation is given for this patient’s X chromosome complement. C, Diagram of the X chromosome abnormalities found in this study. A normal X chromosome, X chromosomes from a mother and daughter with SS from the UK, and an X triple mosaic defect in the X chromosome from an SS patient at the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation (OMRF) are shown.

We identified another SS patient with a rare X chromosome abnormality in a UK cohort of SS patients. The patient was studied by karyotyping when she was a child because of the presence of epilepsy, oligomenorrhea, and thyroid dysfunction. That study showed 1 normal X chromosome and 1 isochrome Xp, that is, an X chromosome with 2 p arms (Figure 1C). Her mother had an inverted segment of Xq (Figure 1C). Both the mother and daughter have SS. This entire UK cohort of 940 SS patients has not been systematically studied for X chromosome abnormalities, as ~700 are included among the 2,138 studied above. So, while the identification of this partial triplication of Xp must be considered anecdotal, the triplicated region overlaps with the one found among the systematically studied patients (Figure 1C). Thus, this incidentally found X chromosome abnormality supports the idea that a gene or genes within distal Xp mediate the X chromosome dose effect.

We found no control subject (n = 2,712) with the X chromosome triple mosaic or any variant thereof (Table 1).

DISCUSSION

Similar to many other autoimmune diseases, SLE and SS have a marked sex bias, with ~10 times more women affected than men. A number of hypotheses have been proposed, and some of these tested, to explain the marked sex bias in these diseases. An obvious difference is sex hormones, which might include not only estrogen, androgen, and progesterone, but also prolactin (22). Several estrogenic effects, including differentiation of T helper cells, induction of interferon, and survival of B cells, may predispose to autoimmune disease (23), as well as the recently described effects on the autoimmune regulator gene AIRE (24). A counterargument to the hormone hypothesis is that sex hormones are within normal limits at the time of SLE diagnosis (25,26) and are not different between men with SLE and men with other chronic, nonautoimmune disease (27). However, men with untreated hypogonadism are reported to be at high risk of SLE (28). There is no evidence of acquired X monosomy among women with SLE (29,30), as there is among those with autoimmune thyroid disease (31) or primary biliary cirrhosis (32).

Failure to inactivate an X chromosome in activated CD4+ T cells is found in SLE patients (33–35) and lupus-prone mice (36) with failure to methylate, and thus silence, X-linked immune genes (37). A recent study showed a global difference in X chromosome inactivation in resting lymphocytes, which was associated with biallelic expression of genes from the lymphocytes of SLE patients (11). Other investigators have proposed that an overall effect of X reactivation might perturb immune tolerance (12). Each of these proposed mechanisms might underlie a gene-dose effect on the X chromosome, which might involve 1 or more immune-related proteins encoded on the X chromosome.

We have found very rare X chromosome abnormalities among patients with either SLE or SS. Based on karyotypes of consecutive live births (5,20,38), the 45,X/46,X/47,XXX triple mosaic is found in ~1 in 25,000 live-born girls, but was present in ~1 in 800 women with SLE. We did not find and did not expect to find the rare triple mosaic among our controls, which number only just above 2,000 persons. But, past studies of >25,000 live female births (5,20,21,38) serve as an external validation of the incidence and prevalence of the 45,X/46,XX/47,XXX mosaic. Meanwhile, the 45,X/46,XX/47,XX+Xp found in 1 of our SS patients is nearly unprecedented (39).

Finding these X chromosome rarities has several implications. For example, only a small percentage of cells from these patients carried the additional X chromosome or portion of the X chromosome. The data reported by Wang et al (11) are consistent with this finding, as the unusual maintenance of X chromosome inactivation in lymphocytes leads to biallelic expression of X-linked genes in only a few cells. In addition, similar to those in whom 100% of cells carried 47,XXX (10), the 4 patients we described have no evidence of abnormal sex hormones or sexual development. Likewise, hormone imbalance due to Turner’s syndrome, which is likely underrepresented among SLE patients (7), is not expected with the low proportion of 45,X cells in our patients. Thus, estrogen, progesterone, or androgen differences cannot be invoked as an explanation of the apparent association of the X triple mosaic with SLE and SS.

Despite the associations we found, an increased prevalence of these rare X chromosome aneuploidies does not prove causality. Nonetheless, given the rarity of these X chromosome abnormalities, association by chance alone seems unlikely to us. The mechanism by which additional X chromosomes or distal Xp fragments increase the risk of these diseases remains to be determined but will provide evidence of causality. Perhaps the findings reported herein give important clues that can be used to direct and narrow the candidate genes affecting the X chromosome dose effect. The distal p arm of the X chromosome contains multiple genes that escape X inactivation (11). Thus, the finding of a partial trisomy of this portion of the X chromosome in these patients suggests, but does not prove, that the gene or genes that mediate this effect are found in this region. There are a number of past examples in which identification of an abnormality on karyotype in an affected individual led to much more rapid identification of the genetic cause of a particular disease. These include Duchenne’s and Becker’s muscular dystrophies, Angelman’s syndrome, and fragile X syndrome. Perhaps relevant to the findings herein, however, was the identification of a chromosome X-21 balanced translocation in a girl with Duchenne’s muscular dystrophy. This finding gave the location of the gene on the X chromosome long before identification was possible through reverse genetics studies (40).

In summary, we suspect that these SLE and SS with X chromosome abnormalities greatly inform the common situation of the marked sex bias between 46,XX women and 46,XY men. Future studies using the localization provided by the very rare patients described herein may be able to concentrate on genes within this shared triplicated region of Xp as the mediators of the X chromosome dose effect for sex bias in SLE and SS.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by the NIH (National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases grants AR-053483 and AR-053734, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases grant AI-082714, and National Institute of General Medical Sciences grant GM-104938), the US Department of Veterans Affairs (Merit Review Award), and the Lupus Research Institute.

Dr. Weisman has received consulting fees from UCB, Ionis, and Ampel (less than $10,000 each) and has served as an expert witness on behalf of Thorpe & Howell. Dr. Bykerk has received consulting fees, speaking fees, and/or honoraria from Bristol-Myers Squibb, UCB, Pfizer, Regeneron, and Sanofi/Genzyme (less than $10,000 each). Dr. Omdal has received consulting fees, speaking fees, and/or honoraria from GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Abbott, and UCB (less than $10,000 each). Dr. Scofield has received consulting fees from UCB and Boston Pharmaceuticals (less than $10,000 each).

REFERENCES

- 1.Borchers AT, Naguwa SM, Shoenfeld Y, Gershwin ME. The geoepidemiology of systemic lupus erythematosus. Autoimmun Rev 2010;9:A277–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rees F, Doherty M, Grainge M, Davenport G, Lanyon P, Zhang W. The incidence and prevalence of systemic lupus erythematosus in the UK, 1999–2012. Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:136–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Qin B, Wang J, Yang Z, Yang M, Ma N, Huang F, et al. Epidemiology of primary Sjögren’s syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:1983–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bojesen A, Juul S, Gravholt CH. Prenatal and postnatal prevalence of Klinefelter syndrome: a national registry study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003;88:622–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nielsen J, Wohlert M. Chromosome abnormalities found among 34,910 newborn children: results from a 13-year incidence study in Arhus. Denmark. Hum Genet 1991;87:81–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Otter M, Schrander-Stumpel C, Curfs LM. Triple X syndrome: a review of the literature. Eur J Hum Genet 2010;18:265–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cooney CM, Bruner GR, Aberle T, Namjou-Khales B, Myers LK, Feo L, et al. 46,X,del(X)(q13) Turner’s syndrome women with systemic lupus erythematosus in a pedigree multiplex for SLE. Genes Immun 2009;10:478–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scofield RH, Bruner GR, Namjou B, Kimberly RP, Ramsey-Goldman R, Petri M, et al. Klinefelter’s syndrome (47,XXY) in male systemic lupus erythematosus patients: support for the notion of a gene-dose effect from the X chromosome. Arthritis Rheum 2008;58:2511–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harris VM, Sharma R, Cavett J, Kurien BT, Liu K, Koelsch KA, et al. Klinefelter’s syndrome (47,XXY) is in excess among men with Sjögren’s syndrome. Clin Immunol 2016;168:25–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu K, Kurien BT, Zimmerman SL, Kaufman KM, Taft DH, Kottyan LC, et al. X chromosome dose and sex bias in autoimmune diseases: increased prevalence of 47,XXX in systemic lupus erythematosus and Sjögren’s syndrome. Arthritis Rheumatol 2016;68:1290–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang J, Syrett CM, Kramer MC, Basu A, Atchison ML, Anguera MC. Unusual maintenance of X chromosome inactivation predisposes female lymphocytes for increased expression from the inactive X. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016;113:E2029–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Forsdyke DR. X chromosome reactivation perturbs intracellular self/not-self discrimination. Immunol Cell Biol 2009;87:525–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Migeon BR. Females are mosaics: X inactivation and sec differences in disease. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dillon SP, Kurien BT, Li S, Bruner GR, Kaufman KM, Harley JB, et al. Sex chromosome aneuploidies among men with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Autoimmun 2012;38:J129–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rasmussen A, Sevier S, Kelly JA, Glenn SB, Aberle T, Cooney CM, et al. The lupus family registry and repository. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2011;50:47–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rasmussen A, Ice JA, Li H, Grundahl K, Kelly JA, Radfar L, et al. Comparison of the American-European Consensus Group Sjögren’s syndrome classification criteria to newly proposed American College of Rheumatology criteria in a large, carefully characterised sicca cohort. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;73:31–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lessard CJ, Li H, Adrianto I, Ice JA, Rasmussen A, Grundahl KM, et al. Variants at multiple loci implicated in both innate and adaptive immune responses are associated with Sjöogren’s syndrome. Nat Genet 2013;45:1284–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tan EM, Cohen AS, Fries JF, Masi AT, McShane DJ, Rothfield NF, et al. The 1982 revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 1982;25:1271–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vitali C, Bombardieri S, Jonsson R, Moutsopoulos HM, Alexander EL, Carsons SE, et al. , and the European Study Group on Classification Criteria for Sjögren’s Syndrome. Classification criteria for Sjögren’s syndrome: a revised version of the European criteria proposed by the American-European Consensus Group. Ann Rheum Dis 2002;61:554–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hamerton JL, Canning N, Ray M, Smith S. A cytogenetic survey of 14,069 newborn infants. Part I. Incidence of chromosome abnormalities. Clin Genet 1975;8:223–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grant WW, Hamerton JL. A cytogenetic survey of 14,069 new born infants. Part II. Preliminary clinical findings on children with sex chromosome anomalies. Clin Genet 1976;10:285–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peeva E, Venkatesh J, Michael D, Diamond B. Prolactin as a modulator of B cell function: implications for SLE. Biomed Pharmacother 58:310–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hughes GC, Choubey D. Modulation of autoimmune rheumatic diseases by oestrogen and progesterone. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2014;10:740–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dragin N, Bismuth J, Cizeron-Clairac G, Biferi MG, Berthault C, Serraf A, et al. Estrogen-mediated downregulation of AIRE influences sexual dimorphism in autoimmune diseases. J Clin Invest 2016;126:1525–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mok CC, Lau CS. Profile of sex hormones in male patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 2000;9:252–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chang DM, Chang CC, Kuo SY, Chu SJ, Chang ML. Hormonal profiles and immunological studies of male lupus in Taiwan. Clin Rheumatol 1999;18:158–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mackworth-Young CG, Parke AL, Morley KD, Fotherby K, Hughes GR. Sex hormones in male patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: a comparison with other disease groups. Eur J Rheumatol Inflamm 1983;6:228–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jimenez-Balderas FJ, Tapia-Serrano R, Fonseca ME, Arellano J, Beltrán A, Yáñez P, et al. High frequency of association of rheumatic/autoimmune diseases and untreated male hypogonadism with severe testicular dysfunction. Arthritis Res 2001;3:362–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Invernizzi P The X chromosome in female-predominant autoimmune diseases. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2007;1110:57–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Invernizzi P, Miozzo M, Oertelt-Prigione S, Meroni PL, Persani L, Selmi C, et al. X monosomy in female systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2007;1110:84–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Invernizzi P, Miozzo M, Selmi C, Persani L, Battezzati PM, Zuin M, et al. X chromosome monosomy: a common mechanism for autoimmune diseases. J Immunol 2005;175:575–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Invernizzi P, Miozzo M, Battezzati PM, Bianchi I, Grati FR, Simoni G, et al. Frequency of monosomy X in women with primary biliary cirrhosis. Lancet 2004;363:533–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lu Q, Wu A, Tesmer L, Ray D, Yousif N, Richardson B. Demethylation of CD40LG on the inactive X in T cells from women with lupus. J Immunol 2007;179:6352–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhao M, Liu S, Luo S, Wu H, Tang M, Cheng W, et al. DNA methylation and mRNA and microRNA expression of SLE CD4+ Tcells correlate with disease phenotype. J Autoimmun 2014;54:127–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hewagama A, Gorelik G, Patel D, Liyanarachchi P, McCune WJ, Somers E, et al. Overexpression of X-linked genes in T cells from women with lupus. J Autoimmun 2013;41:60–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Richardson B, Sawalha AH, Ray D, Yung R. Murine models of lupus induced by hypomethylated T cells (DNA hypomethylation and lupus...). Methods Mol Biol 2012;900:169–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sawalha AH, Wang L, Nadig A, Somers EC, McCune WJ, Cohort Michigan Lupus, et al. Sex-specific differences in the relationship between genetic susceptibility, T cell DNA demethylation and lupus flare severity. J Autoimmun 2012;38:J216–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goad WB, Robinson A, Puck TT. Incidence of aneuploidy in a human population. Am J Hum Genet 1976;28:62–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rigola MA, Carrera M, Ribas I, de la Iglesia C, Mendez B, Egozcue J, et al. Identification of two de novo partial trisomies by comparative genomic hybridization. Clin Genet 2001;59:106–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Verellen-Dumoulin C, Freund M, de Meyer R, Laterre C, Frédéric J, Thompson MW, et al. Expression of an X-linked muscular dystrophy in a female due to translocation involving Xp21 and non-random inactivation of the normal X chromosome. Hum Genet 1984;67:115–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]