Abstract

Objectives

Understanding the role of functional capacity on longevity is important as the population in the United States ages. The purpose of this study was to determine the burden of instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) and activities of daily living (ADL) disabilities for a nationally-representative sample of middle-aged and older adults in the United States.

Design

Longitudinal-Panel.

Setting

Core interviews were often performed in person or over the telephone.

Participants

A sub-sample of 31,055 participants aged at least 50 years from the 1998–2014 waves of the Health and Retirement Study who reported having a functional disability were included.

Measurements

Ability to perform IADLs and ADLs were self-reported at each wave. The National Death Index was used to ascertain date of death. The number of years of life that were lost (YLLs) and years lived with a disability (YLDs) were summed for the calculation of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs). Sampling weights were used in the analyses to make the DALYs nationally-representative. The results for YLLs, YLDs, and DALYs are reported in thousands.

Results

Of the participants included, 14,990 had an IADL disability and 13,136 had an ADL disability. Men and women with an IADL disability had 236,037 and 233,772 DALYs, respectively; whereas, there were 178,594 DALYs for males and 253,630 DALYs for females with an ADL disability. Collectively, there were 469,809 years of healthy life lost from IADL impairments, and 432,224 years of healthy life lost from ADL limitations.

Conclusions

These findings should be used to inform healthcare providers and guide interventions aiming to preserve the functional capacity of aging adults. Prioritizing health-related resources for mitigating the burden of functional disabilities may help aging adults increase their quality of life and life expectancy over time.

Key words: Geriatrics, morbidity, mortality, rehabilitation

Introduction

Declines in functional capacity occur with advancing age (1), thereby placing middle-aged and older adults with functional disabilities at greater risk for poor health outcomes and early mortality (2, 3). Measures of function such as instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) are used to assess autonomous living abilities, while activities of daily living (ADLs) are used to examine self-care capabilities (4). Given that many working-aged and older adults are living with one or more functional disabilities (5), understanding how longitudinal declines in functional capacity impact the health of the growing aging population in the United States is important for guiding health-related resources and informing strategies aiming to preserve function during aging.

Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) are used globally for quantifying the burden of a given health outcome (6, 7). Both non-fatal health loss and premature death are examined to determine the burden of a health outcome (8). Calculating DALYs for IADLs and ADLs will allow for a better understanding of how functional capacity factors into health and premature death during aging (1). Accordingly, the purpose of this study was to determine the burden of IADL and ADL disabilities for middle-aged and older adults in the United States.

Methods

Participants

Data from 37,495 participants in the 1998–2014 waves of the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) were utilized for the analyses. Cleaned and standardized RAND HRS data were joined with individual HRS data files. The HRS seeks to understand the health and economic implications occurring in aging adults that can threaten or promote health and wealth at individual- and population-levels (9). Since 1998, the HRS has provided data for a nationally-representative sample of individuals aged 50 years and older, with interviews occurring biennially (9). A multi-stage probability design is employed by the HRS, including geographical stratification and oversampling of specific demographic groups. Sample weights are provided to account for the multi-stage area probability design. Additional details for the HRS are given elsewhere (10).

Written informed consent was provided by participants in the HRS and protocols were approved by the University of Michigan Behavioral Sciences Committee Institutional Review Board. There were no direct identifiers in these data, thereby ensuring participant anonymity.

Measures

Age and sex were reported by participants. Exclusions occurred for missing sex (n=7), no participation in the 1998- 2014 waves (n=4,002), and unknown age (n=2,431). At each wave, participants self-reported their ability to perform six IADLs: use a map, prepare hot meals, take medications, manage money, use a telephone, and shop for groceries. Individuals indicating difficulty or an inability to perform any IADL were considered as having an IADL disability. Participants told survey interviewers about their ability to perform six ADLs at each wave: walk across a room, shower or bathe, eat, get in or out of bed, use the toilet, and dress themselves. Those reporting difficulty or an inability to perform any ADL were regarded as having an ADL disability. The National Death Index was used to verify date of death. Exit interviews were also conducted with a surviving spouse, child, or other informant to gather information concerning medical expenses, family relations, outlook of assets after death, and other circumstances that may have occurred toward the end of life for participants who died (9).

Statistical Analysis

Procedures from the World Health Organization were used for calculating DALYs (11). Participants were first stratified by sex because of differences in life expectancy, and then by age category (50–59 years, 60–69 years, 70–79 years, ≥80 years). The age at which an IADL or ADL disability was first reported determined the age categories for those included.

Years lived with a disability (YLDs) was calculated by taking the product of the number of incident cases for either an IADL or ADL disability, corresponding disability weight, and mean duration of years lived with the functional limitation until death, or truncation. The disability weights used were 0.810 for IADL impairments and 0.920 for ADL limitations (8). For those living or lost to follow-up (truncation), the mean duration of years lived with either an IADL or ADL disability was determined by using their estimated life expectancy at age of truncation (12). Total YLDs were determined by summing the YLDs for each sex, across age categories.

Years of life lost (YLLs) were calculated by multiplying the number of deaths that occurred for those with an IADL or ADL disability by the average life expectancy at age of death in years. Life expectancy at each age and sex was determined from the Period Life Table (13). Total YLLs were also determined by summing the YLLs for each sex, across age categories.

For each sex, YLDs and YLLs were summed across age categories for determining DALYs for each functional outcome. Thereafter, the DALYs for males and females were summed for calculating overall DALYs. Sampling weights were used in the analyses to make the DALYs nationally-representative. The YLLs, YLDs, and DALYs are presented in thousands. Analyses were executed with SAS 9.4 software (SAS Institute; Cary, NC).

Results

Of the 31,055 participants, 14,990 (48.2%) had an IADL disability and 13,136 (42.2%) had an ADL disability. Table 1 presents the non-weighted and weighted descriptive characteristics of the participants.

Table 1.

Non-Weighted and Weighted Descriptive Characteristics of the Participants

| Has IADL Disability | Weighted Has IADL Disability | Has ADL Disability | Weighted Has ADL Disability | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n=14,990) | (n=50,452,594) | (n=13,136) | (n=43,806,648) | |

| Age at Entry (years) | 67.1±11.3 | 65.0±0.1 | 67.1±11.4 | 65.0±0.1 |

| Female (n (%)) | 7,974 (53.1%) | 25,336,944 (50.2%) | 7,974 (60.6%) | 25,600,917 (58.4%) |

| Age at Death (years) | 81.6±10.2 | 80.6±0.2 | 81.6±10.2 | 80.6±0.2 |

| Died During Study (n (%)) | 7,381 (49.2%) | 21,793,335 (43.2%) | 6,513 (49.5%) | 19,150,479 (43.7%) |

Note: ADL=Activities of Daily Living; IADL=Instrumental Activities of Daily Living; Results are reported as mean±standard deviation or mean±standard error

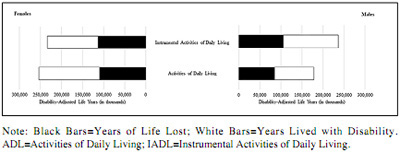

The weighted YLDs and YLLs for IADL and ADL limitations are depicted in Figure 1. Males with an IADL disability had 130,504 YLDs and 105,532 YLLs, totaling for 236,037 DALYs; whereas, women with an IADL disability had 120,278 YLDs and 113,493 YLLs, totaling for 233,772 DALYs. Combined, there were 469,809 years of healthy life lost from IADL impairments.

Figure 1.

The Burden of IADL and ADL Disabilities by Sex

Men with an ADL disability had 93,822 YLDs and 84,772 YLLs, totaling 178,594 DALYs; however, women with an ADL disability had 144,074 YLDs and 109,555 YLLs, totaling 253,630 DALYS. Combined, there were 432,224 years of healthy life lost from ADL limitations. Detailed information for the burden of IADL and ADL disabilities are presented in Appendix 1.

Discussion

The results of this investigation indicate that millions of healthy years of life were lost as a result of IADL and ADL disabilities for middle-aged and older adults in the United States. Interestingly, the burden of an IADL disability was higher in men than women; whereas, the burden of an ADL disability was greater in women than men. Our findings should be used to inform healthcare providers working with individuals that are at risk for, or already have a functional disability. Likewise, monitoring DALYs will help to guide targeted interventions aiming to help aging adults preserve function.

Tasks included in IADL assessments represent higher-level cognitive function, and impairments in IADLs often precede disabilities in ADLs (4). Given that males experience declines in cognitive functioning before females (14), this may explain why our results indicate the burden of an IADL impairment was especially high in males. Similarly, our findings revealed that the burden of an ADL disability was higher in females than the burden of an IADL impairment. Females experience greater deficits in their self-care functioning than males during aging (1). Although females have a greater life expectancy than males, females tend to have a poor health status as they age and are living longer with functional limitations (15).

Healthcare providers that treat middle-aged and older adult patients should continually monitor functional capacity during aging. Deficiencies in IADLs and ADLs may accelerate the disabling process, leading to other poor health outcomes, institutionalization, and premature mortality (2, 3, 16). Healthcare entities should continually monitor DALYs for the efficiency and allocation of resources. Interventions that target physical activity participation, nutritional counseling, depression, pain, cognition, and other healthy behaviors should be encouraged to preserve functional capacity in middle-aged and older adults (17). Practicing such behaviors, especially earlier in life, may decrease the number of healthy years of life that are lost from IADL and ADL disabilities.

Some study limitations should be noted. Multimorbidity was not controlled for in our disability weights because we used an incidence-driven DALY calculation. Participants may have died or were lost to follow-up before a functional disability was reported, thereby creating underestimations for our results; however, those who recovered from a functional disability may have contributed to overestimates. It is possible that some participants may have had a functional limitation earlier in life before entering the HRS because persons have to be aged at least 50 years to be included. Statistical tests of inference were not performed on DALY estimates because DALYs are typically presented as a stand-alone result.

Conclusions

Millions of healthy years of life were lost from IADL and ADL limitations for middle-aged and older adults in the United States. The burden of IADL impairments were greatest in men; whereas, the burden of ADL limitations were greatest in women. Our findings should be used to inform healthcare providers working with middle-aged and older adult patients that are at risk for or already have a functional limitation. Engaging in healthy behaviors may improve function for those with an existing functional disability, while adhering to healthy behaviors earlier in life may lower the burden of IADL and ADL disabilities over time.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Funding Sources

This study was supported in part by a grant (P2CHD065702) from the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (National Center for Medical Rehabilitation Research), the National Institute for Neurological Disorders and Stroke, and the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering.

Ethical standard

This research complies with the current laws of the United States.»

Electronic Supplementary Material

Supplementary material is available for this article at https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-018-1133-2 and is accessible for authorized users.

Appendix 1. Results of the Disability-Adjusted Life Years for Functional Disabilities by Sex.

References

- 1.Millan-Calenti JC, Tubío J, Pita-Fernández S, et al. Prevalence of functional disability in activities of daily living (ADL), instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) and associated factors, as predictors of morbidity and mortality. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2010;50:306–310. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2009.04.017. 10.1016/j.archger.2009.04.017 PubMed PMID: 19520442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Majer IM, Nusselder WJ, Mackenbach JP, Klijs B v, Baal PH. Mortality risk associated with disability: a population-based record linkage study. Am J Public Health. 2011;101:e9–e15. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300361. 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300361 PubMed PMID: 22021307, PMCID 3222426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dunlay SM, Manemann SM, Chamberlain AM, et al. Activities of daily living and outcomes in heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2015;8:261–267. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.114.001542. 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.114.001542 PubMed PMID: 25717059, PMCID 4366326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liang Y, Welmer A-K, Möller J, Qiu C. Trends in disability of instrumental activities of daily living among older Chinese adults, 1997-2006: population based study. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e016996. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016996. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016996 PubMed PMID: 28851795, PMCID 5724119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stevens AC. Adults with one or more functional disabilities—United States, 2011–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:1021–1025. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6538a1. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6538a1 PubMed PMID: 27684532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mokdad AH, Ballestros K, Echko M, et al. The state of US health, 1990-2016: burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors among US states. JAMA. 2018;319:1444–1472. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.0158. 10.1001/jama.2018.0158 PubMed PMID: 29634829, PMCID 5933332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Global Burden of Disease Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet. 2017;390:1211–1259. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32154-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grosse SD, Lollar DJ, Campbell VA, Chamie M. Disability and disability-adjusted life years: not the same. Public Health Rep. 2009;124:197–202. doi: 10.1177/003335490912400206. 10.1177/003335490912400206 PubMed PMID: 19320360, PMCID 2646475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sonnega A, Faul JD, Ofstedal MB, Langa KM, Phillips JW, Weir DR. Cohort profile: the health and retirement study (HRS) Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43:576–585. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyu067. 10.1093/ije/dyu067 PubMed PMID: 24671021, PMCID 3997380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Health and Retirement Study. HRS Data Book. https://hrs.isr.umich.edu/about/databook. Accessed 22 August 2018.

- 11.World Health Organization. Metrics: Disability-Adjusted Life Year (DALY). http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/metrics_daly/en/. Accessed 22 August 2018.

- 12.Struijk EA, May AM, Beulens JW, et al. Development of methodology for disabilityadjusted life years (DALYs) calculation based on real-life data. PLoS One. 2013;8:e74294. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074294. 10.1371/journal.pone.0074294 PubMed PMID: 24073206, PMCID 3779209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.United States Social Security Administration. Period Life Table, 2014. https://www.ssa.gov/oact/STATS/table4c6_2014.html. Accessed 22 August 2018.

- 14.Petersen RC, Roberts RO, Knopman DS, et al. Prevalence of mild cognitive impairment is higher in men The Mayo Clinic Study of Aging. Neurology. 2010;75:889–897. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181f11d85. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181f11d85 PubMed PMID: 20820000, PMCID 2938972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hubbard RE. Sex differences in frailty. Interdiscip Top Gerontol Geriatr. 2015;41:41–53. doi: 10.1159/000381161. 10.1159/000381161 PubMed PMID: 26301978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fong JH, Mitchell OS, Koh BS. Disaggregating activities of daily living limitations for predicting nursing home admission. Health Serv Res. 2015;50:560–578. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12235. 10.1111/1475-6773.12235 PubMed PMID: 25256014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mlinac ME, Feng MC. Assessment of activities of daily living, self-care, and independence. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2016;31:506–516. doi: 10.1093/arclin/acw049. 10.1093/arclin/acw049 PubMed PMID: 27475282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 1. Results of the Disability-Adjusted Life Years for Functional Disabilities by Sex.