Abstract

Background and Purpose:

Hypertension is a leading risk factor for cerebrovascular disease and loss of brain health. While the brain renin-angiotensin system (RAS) contributes to hypertension, its potential impact on the local vasculature is unclear. We tested the hypothesis that activation of the brain RAS would alter the local vasculature using a modified deoxycorticosterone acetate (DOCA) model.

Methods:

C57BL/6 mice treated with DOCA (50 mg SQ)(or shams) were given tap H2O and H2O with 0.9% NaCl for 1–3 weeks.

Results:

In isolated cerebral arteries and parenchymal arterioles from DOCA treated male mice, endothelium- and nitric oxide (NO)-dependent dilation was progressively impaired, while mesenteric arteries were unaffected. In contrast, cerebral endothelial function was not significantly affected in female mice treated with DOCA. In males, mRNA expression of renal Ren1 was markedly reduced while RAS components (e.g., AGT, ACE) were increased in both brain and cerebral arteries with central RAS activation. In NZ44 reporter mice expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP) driven by the angiotensin II type 1A receptor (Agtr1a) promoter, DOCA increased GFP expression ~3-fold in cerebral arteries. Impaired endothelial responses were restored to normal by losartan, an AT1R antagonist. Lastly, DOCA treatment produced inward remodeling of parenchymal arterioles.

Conclusions:

These findings suggest activation of the central and cerebrovascular RAS impairs endothelial (NO-dependent) signaling in brain through expression and activation of AT1R and sex-dependent effects. The central RAS may be a key contributor to vascular dysfunction in brain in a preclinical (low-renin) model of hypertension. Because the brain RAS is also activated during aging and other diseases, a common mechanism may promote loss of endothelial and brain health despite diverse etiology.

Keywords: cerebral artery, parenchymal arterioles, small vessel disease, AT1 receptor, sex-dependent, endothelium, nitric oxide

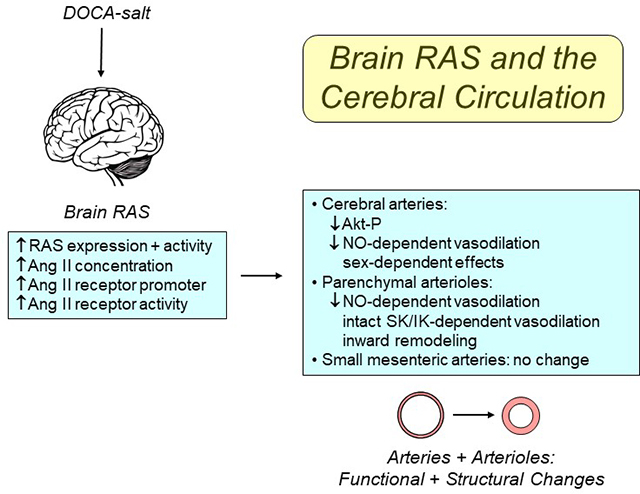

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Chronic hypertension is a global pandemic, the leading modifiable cause of vascular disease and premature death worldwide.1, 2 Hypertension has major effects on cerebrovascular biology, and as a consequence, brain health. Effects of hypertension include endothelial dysfunction, vascular remodeling and hypoperfusion.3, 4 Hypertension is a major risk factor for strokes and cognitive deficits.2, 5 While current therapies are effective in treating a subset of hypertensive individuals, a significant percentage are less than fully controlled or exhibit resistant hypertension.6–8 For reasons that are not clear, hypertension is a stronger risk factor for stroke than for myocardial infarction, and a much greater risk factor for stroke than diabetes, tobacco use, hyperlipidemia, or low physical activity.2, 9 Thus, a greater understanding of factors that contribute to cerebrovascular disease during hypertension is essential in order to improve therapy and brain health.

The renin-angiotensin system (RAS) is a major contributor to increased arterial pressure during hypertension. In addition to the classic RAS, where key components are circulating in blood, distinct tissue-specific RAS’s are present within organs where they can exert local effects with activation.6, 7 The brain RAS is one example, contributing to regulation of sympathetic nerves, salt- and fluid-intake, and arterial pressure.6, 7 Pharmacological targeting the RAS in hypertensive individuals may occur at the level of the classic and/or the tissue RAS.6, 7

In humans with essential hypertension, levels of circulating renin are reduced in about one-third of subjects.10 The fraction of individuals with reduced renin is increased further in subgroups including Blacks, the elderly, and resistant hypertension.8, 10 There are few models of low-renin hypertension, one being the DOCA-salt model.11 This model exhibits activation of the brain RAS, but suppression of the peripheral RAS.11, 12 While DOCA-salt models have been used to study peripheral blood vessels, very few studies have examined effects within the cerebral circulation.

In the present study, we used a DOCA-salt model to test the hypothesis that stimulation of the brain RAS would alter local vascular phenomics, while examining mechanisms involved. We found that activation of the brain RAS produced time- and sex-dependent impairment of endothelial function in cerebral arteries and parenchymal arterioles, with changes in vascular structure in parenchymal arterioles. DOCA-salt increased expression of RAS components in brain and the cerebral vasculature. Mechanistically, the dysfunction was dependent on local activation of angiotensin type 1 receptors (AT1R). Together, our findings suggest the cerebral vasculature is particularly susceptible to dysfunction during DOCA-salt (low-renin) hypertension, likely due to increased brain and/or cerebrovascular RAS activity.

Materials and Methods

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Experimental animals.

Animal protocols were approved by the University of Iowa Animal Care and Use Committee. We used male and female C57BL/6J mice and male transgenic mice expressing an artificial chromosome containing enhanced GFP under the control of the Agtr1a promoter maintained on the C57BL/6 background (designated NZ44 from GENSAT).13 All mice were fed standard chow and water ad libitum. Details regarding experimental procedures (blood pressure in the model,11, 14 measurements of vascular function,14–21 PCR,11, 14, 18 Western blotting15) and data analysis are presented in the online-only Data Supplement.

Results

Activation of the central RAS with suppression of the peripheral RAS.

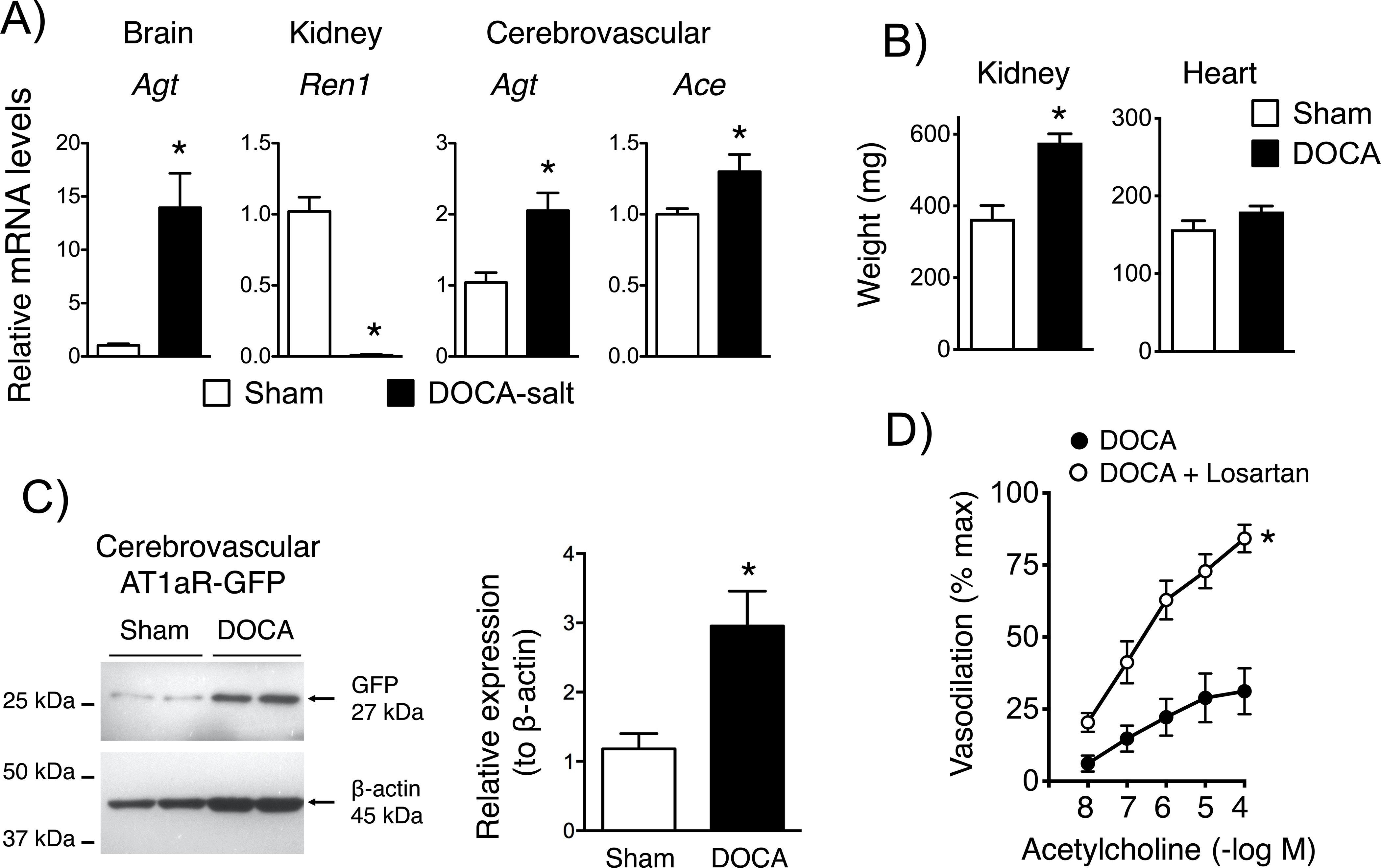

Consistent with previous studies,11 mRNA expression of angiotensinogen (Agt) in cerebral cortex was significantly elevated compared with shams following DOCA-salt treatment (Figure 1). In contrast, DOCA-salt markedly suppressed renal renin (Ren1) (Figure 1). Kidney weight was significantly increased by DOCA-salt (P<0.05), while heart weight tended to increase (P=0.08) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Brain cortical angiotensinogen (Agt), renal renin (Ren1), and cerebrovascular Agt and angiotensin converting enzyme (Ace) mRNA expression in sham and DOCA-salt treated mice in (A)(n=5). Kidney and heart weight in (B)(n=7 and 10). In (C), protein expression of GFP in cerebral arteries from sham and DOCA-salt treated mice is presented (left), with quantification by densitometry (right). GFP was normalized to β-actin expression (n=6). Dilation of basilar arteries from DOCA-salt treated mice to acetylcholine in the absence and presence of losartan (D)(n=5). For all panels, *P<0.05 vs. sham. The analysis in (D) was based on two-way ANOVA with Bonferonni post hoc tests. Values were significantly different at 10−7 M and above, with a P value <0.0001 at the highest concentration.

Impaired endothelium-dependent dilation in cerebral arteries.

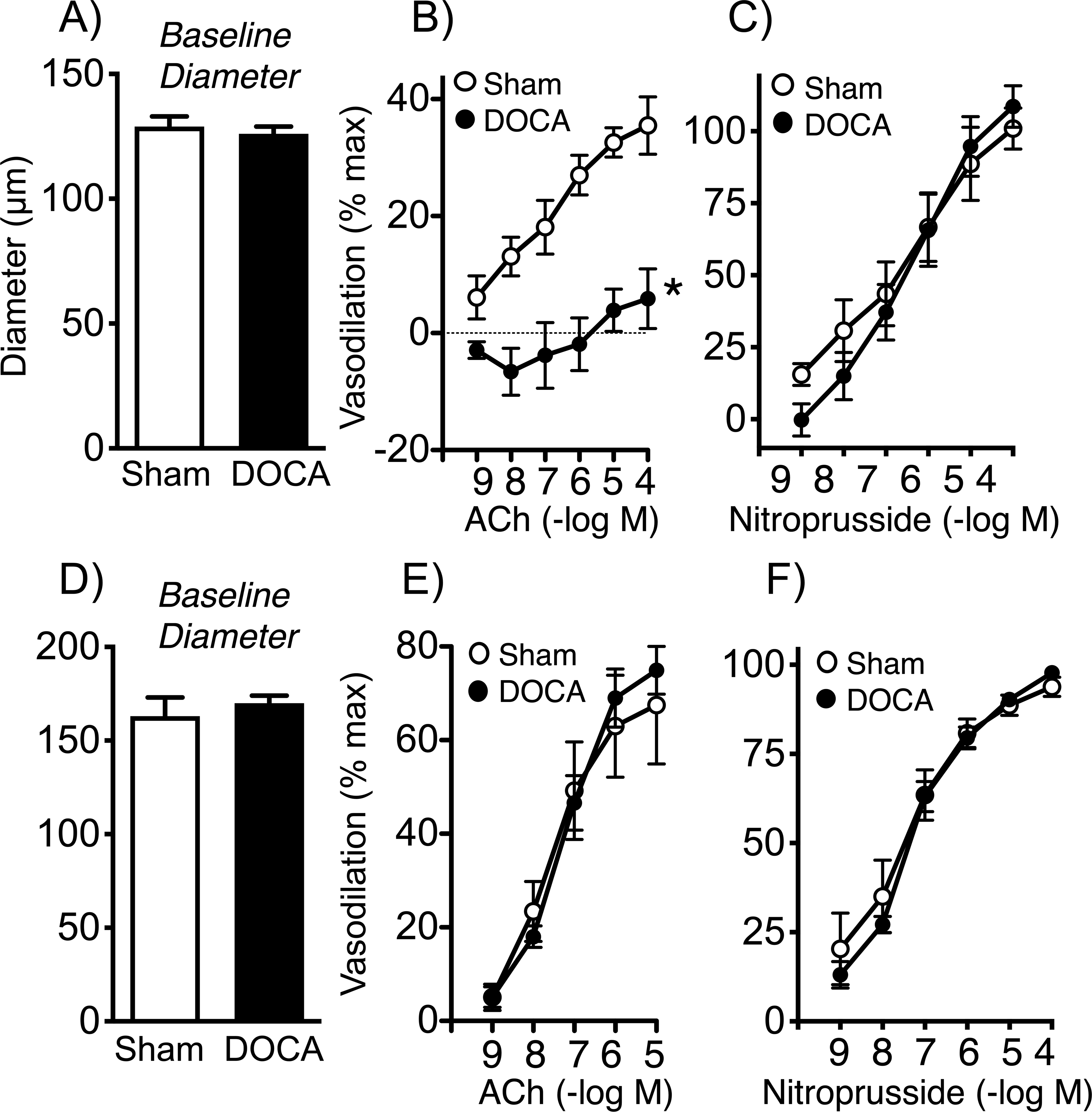

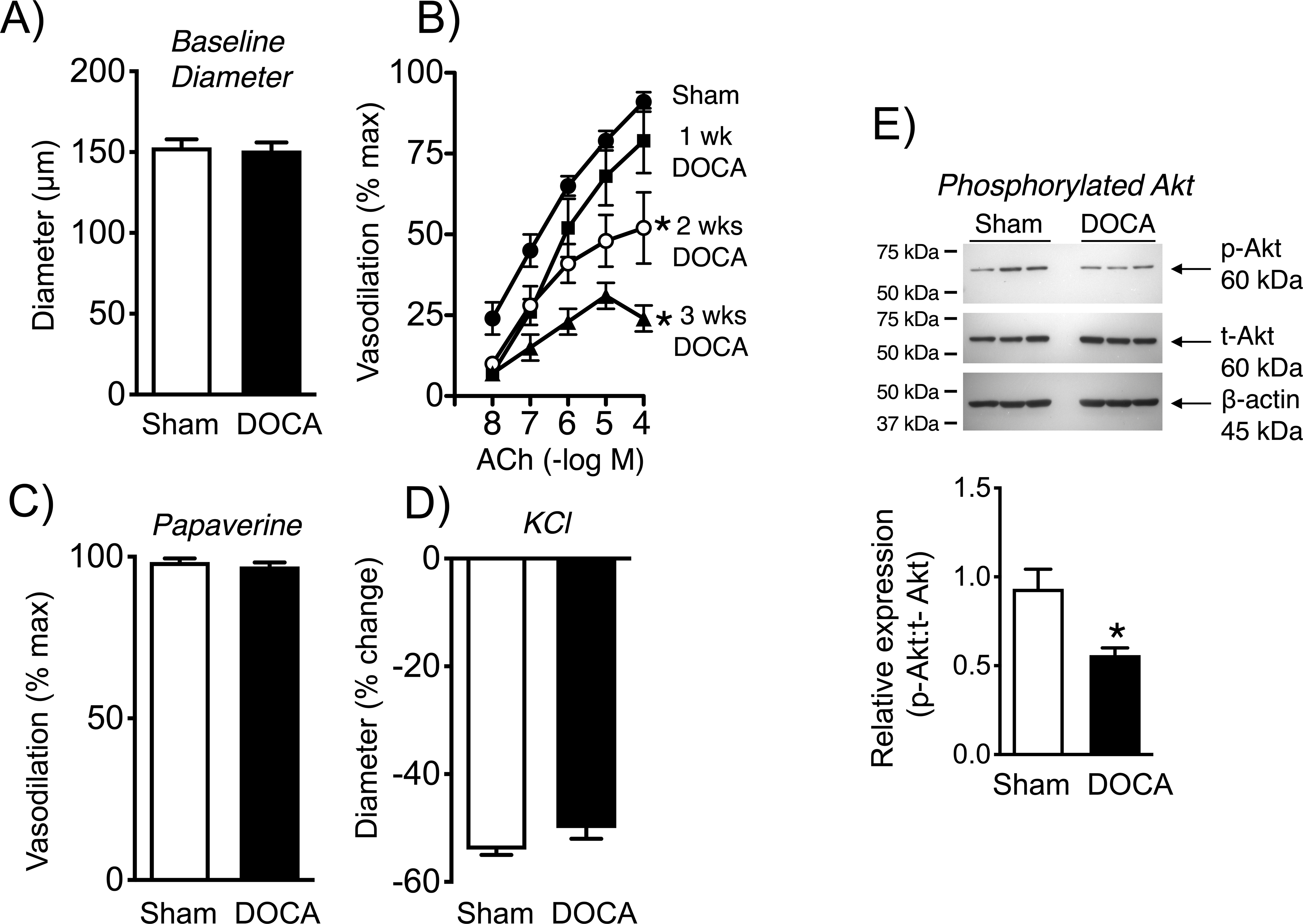

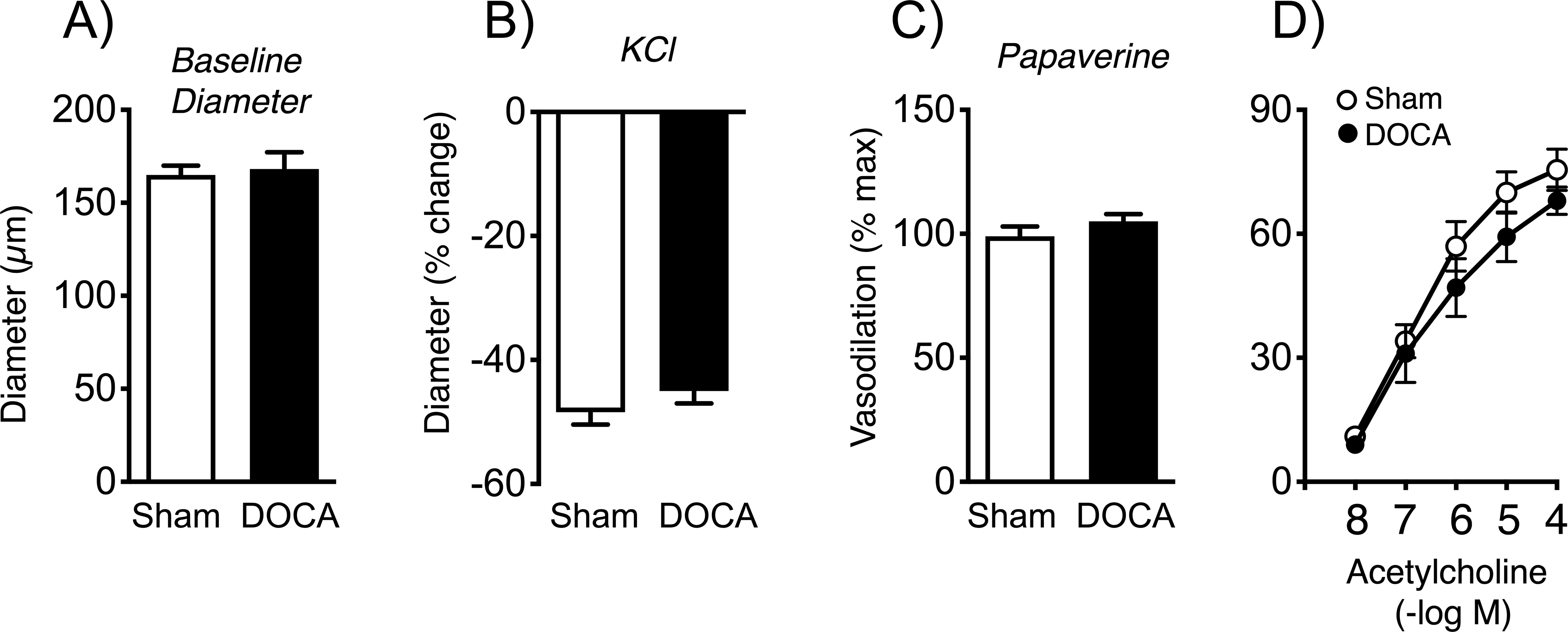

Baseline diameters of the MCA and basilar arteries in male mice were similar following sham or DOCA-salt treatment (Figures 2, 3). Following treatment with DOCA-salt for three weeks, endothelium-dependent dilation to the neurotransmitter acetylcholine was markedly impaired compared to controls (Figures 2, 3). In the MCA, effects of acetylcholine were essentially eliminated, while maximal responses in the basilar artery were reduced by ~74% (Figures 2, 3). Endothelium-independent vasodilation to nitroprusside and papaverine was similar in the two groups, indicating effects of DOCA-salt were endothelium-dependent (Figures 2, 3, Figure IA in the Data Supplement). DOCA-salt did not significantly affect constriction of arteries to KCl (Figure 3, Figure IB in the Data Supplement). With the characterization, we examined temporal changes. In the basilar artery, DOCA-salt caused a time-dependent reduction in responses to acetylcholine (Figure 3), with no significant differences in responses to KCl or papaverine (data not shown). Maximal effects of acetylcholine were reduced by 43 and 74% at 2 and 3 weeks of DOCA-salt treatment, respectively (Figure 2). These data demonstrate that DOCA-salt impairs endothelial function, with similar effects in the basilar artery and the MCA.

Figure 2.

Baseline diameter (A) and dilation of middle cerebral arteries from sham and DOCA-salt treated mice to acetylcholine (B) and nitroprusside (C). The analysis in (B) was based on two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s post hoc tests. Values were significantly different at 10−8 M and above, with a P value <0.0001 at the highest concentration. Baseline diameter (2D) and dilation of mesenteric arteries from sham and DOCA-salt treated mice to acetylcholine (E) and nitroprusside (F) were similar. For all panels, n=5 or 6. *P<0.05 vs. sham.

Figure 3.

Baseline diameter (A)(n=9 and 21) and dilation of basilar arteries over time from sham and DOCA-salt treated mice to acetylcholine (B)(n=9 shams, n=4, 3, and 8 at 1, 2, and 3 weeks of DOCA treatment, respectively) and papaverine (C)(n=9 and 8), with constriction to KCl in (D)(n=9). In panel A, data for baseline diameter in the DOCA group was not normally distributed, so a Mann-Whitney test was performed. That test indicated no difference between groups (P = 0.7641). The analysis in (B) was based on two-way ANOVA with Bonferonni post hoc tests. Values were significant at 2 and 3 wks, with P values of 0.0049 and <0.0001 at 2 and 3 wks, respectively. In panel C, data for papaverine in the DOCA group was not normally distributed, so a Mann-Whitney test was performed. That analysis indicated no difference between groups (P = 0.6877). Protein expression of phosphorylated Akt in cerebral arteries from sham and DOCA-salt treated mice (E). Phosphorylated Akt was expressed relative to total Akt levels with quantification by densitometry (n=6). β-actin is shown as a loading control. There is a blank lane (loading buffer only) between sham and DOCA samples. *P<0.05 vs. sham.

Baseline diameter of small mesenteric arteries were not affected by DOCA-salt (Figure 2). In contrast to profound impairment in cerebral arteries, dilation of small mesenteric arteries to acetylcholine were comparable in both groups of mice (Figure 2). In mesenteric arteries, dilation to nitroprusside, constriction to KCl, and dilation to papaverine were not significantly affected by DOCA-salt (Figure 2, Figures IC and ID in the Data Supplement). These findings suggest effects of DOCA-salt on endothelial function in the current model may be brain specific.

Akt phosphorylation.

Endothelial NO synthase (eNOS) plays a prominent role in vascular biology.4, 22 In cerebral arteries, dilation to acetylcholine is mediated by production of NO by eNOS.4, 22 Phosphorylation of Akt (p-Akt, a serine/threonine protein kinase) is an upstream driver of eNOS activity.23 Western blotting using pooled arteries from individual mice (MCA, basilar arteries, circle of Willis) revealed that DOCA-salt reduced p-Akt by approximately one-half (Figure 3).

Sex-dependent effects.

Baseline diameter and responses to KCl or papaverine were not significantly affected by DOCA-salt in female mice (Figure 4). In contrast to the effects of DOCA-salt in male mice (Figures 2, 3), vasodilation to acetylcholine in female mice was not significantly affected after three weeks of treatment (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Baseline diameter (A), constriction to KCl (B), and dilation of basilar arteries from sham and DOCA-salt treated mice to papaverine (C) and acetylcholine (D) in females. In panel C, data for papaverine was not normally distributed, so a Mann-Whitney test was performed. That analysis indicated no difference between groups (P = 0.2879). For all panels, n=6 in each group.

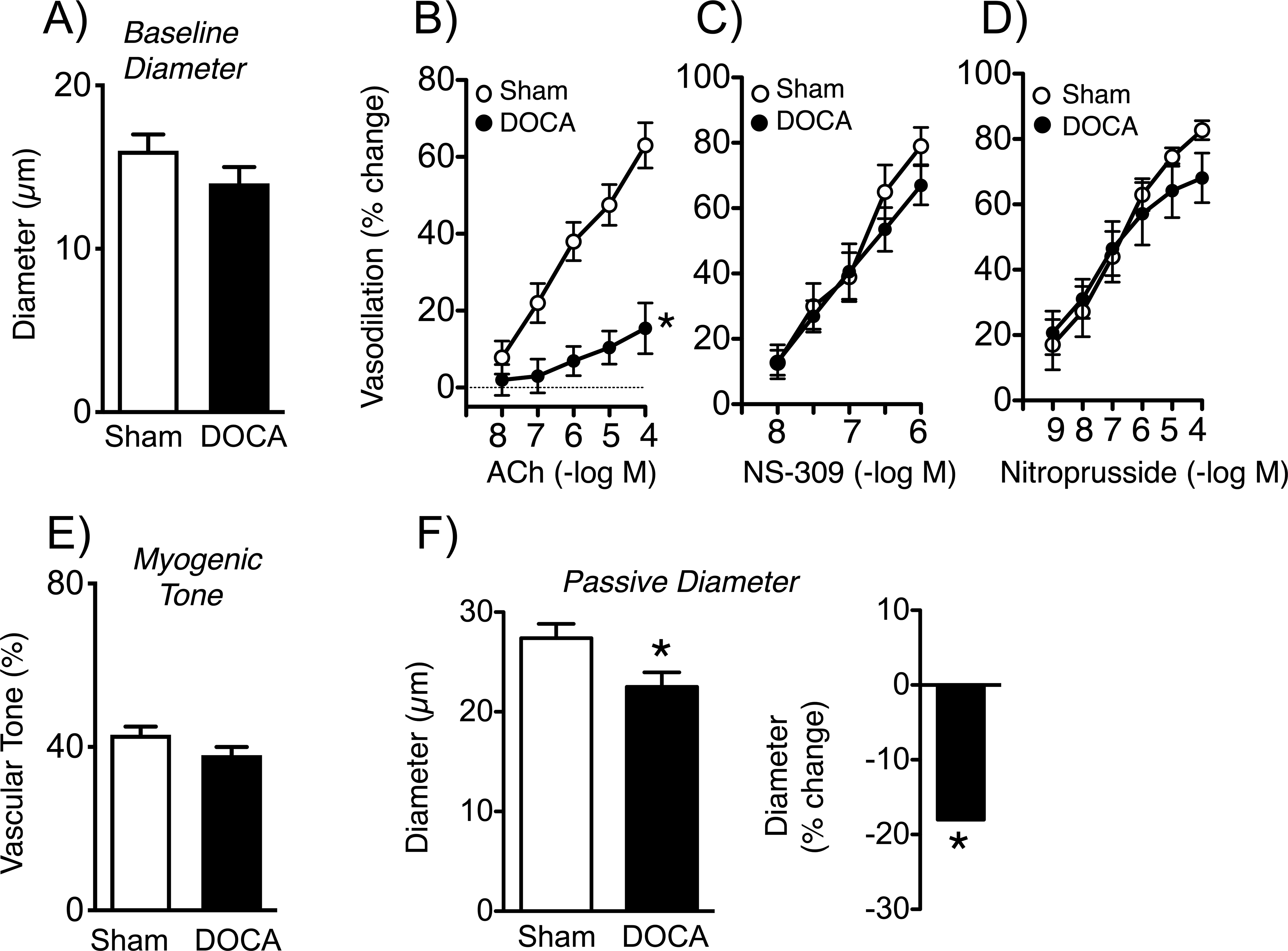

Selective signaling impairment in parenchymal arterioles.

Because parenchymal arterioles are a preferential target of small vessel disease, we studied effects of brain RAS activation on this segment of the microcirculation. In arterioles with myogenic tone, baseline diameters were not significantly altered by DOCA-salt (Figure 5). Dilation of parenchymal arterioles to acetylcholine is dependent on NO production in mice and humans.17, 24 Similar to cerebral arteries, DOCA-salt substantially reduced vasodilation to acetylcholine, with maximal effects decreasing by ~76% (Figure 5). In contrast, effects of NS-309, an activator of small- and intermediate-conductance K+ channels (SK/IK) in endothelial cells, generating endothelium-dependent hyperpolarization,17 were not significantly affected by DOCA-salt (Figure 5). Vasodilation to nitroprusside was also not affected (Figure 5). Maximal vasodilation to papaverine was similar in the two groups (98±1 and 97±1%, n=12 and 8 in sham and DOCA-salt groups, respectively). These data suggest that microvascular effects of DOCA-salt on endothelial cells are pathway specific. Lastly, the degree of myogenic tone developed was similar in arterioles from DOCA-salt and sham treated mice (Figure 5). Thus, changes in endothelial function in parenchymal arterioles were selective, not due to differences in myogenic tone, and were similar in magnitude to cerebral arteries where preconstriction was produced pharmacologically (Figures 2, 3).

Figure 5.

Baseline diameter (A) (n=18 and 15) and vasodilation of parenchymal arterioles from sham and DOCA-salt treated mice to acetylcholine (B)(n=6), NS-309 (C) (n= 6 and 5), and nitroprusside (D) (n=5 and 4). Myogenic tone (n=18 and 15) is shown in (E). Passive diameter of parenchymal arterioles (F, left panel; n=18 and 15) and the percent reduction in diameter in DOCA-salt mice (F, right panel). In panel A, data for baseline diameter in the DOCA group was not normally distributed, so a Mann-Whitney test was performed. That analysis showed no difference between groups (P = 0.1685). *P<0.05 vs. sham.

Structure of parenchymal arterioles.

Changes in vascular structure occur commonly during hypertension.3, 22 In the present study, inner diameter of maximally dilated parenchymal arterioles was significantly reduced by treatment with DOCA-salt (Figure 5). The average group difference in passive diameter was almost 20% (Figure 5).

Expression of RAS components and role of the AT1R in vascular dysfunction.

While the present and previous data suggest the brain RAS is activated by DOCA-salt,11 very little is known about potential effects of DOCA-salt on a RAS within the cerebral vasculature itself. Thus, we determined if vascular RAS expression was altered following DOCA-salt treatment. Expression of mRNA for Agt and Ace were increased in cerebral arteries by DOCA-salt (Figure 1). Because Western blotting to quantify AT1R protein is difficult due to lack of antibody specificity, we used an alternative, more novel approach - NZ44 reporter mice expressing GFP driven by the Agtr1a promoter.13 In NZ44 mice, DOCA-salt increased GFP expression in cerebral arteries ~3-fold compared to shams (Figure 1), consistent with increased transcription. Because there was some variation in the level of the housekeeping protein in this subset of data, we performed a second statistical analysis (Figure II in the Data Supplement). That analysis also indicated a significant difference in the expression of GFP relative to ß-actin in the DOCA-salt group (p=0.0152) (Figure II in the Data Supplement).

As a functional correlate, acute treatment with losartan (1 μmol/L, an AT1R antagonist) restored endothelium-dependent dilation to normal levels in cerebral arteries from male DOCA-salt treated mice (compare Figure 1 with Figure 3). These findings support the concept that DOCA-salt activates components of a RAS within the brain vasculature itself, and impairs endothelial function via effects on the AT1R.

Discussion

There are several major new findings in the present study. First, activation of the brain RAS with DOCA-salt in male mice impairs endothelium-dependent vasodilation (with reduced activity of Akt) in several segments of the cerebral vasculature (two different cerebral arteries, parenchymal arterioles) without altering responses in small mesenteric arteries. The impairment of cerebrovascular endothelial function increased over time. Second, effects on endothelial function were sex-dependent, no significant changes were observed in female mice. Third, endothelial dysfunction following DOCA-salt involved NO-dependent responses, but not vasodilation mediated by endothelial SK/IK channels. Fourth, in addition to the brain RAS, DOCA-salt increased expression of components of a RAS within the cerebral vasculature itself, with endothelial dysfunction dependent on activation of local AT1R. Fifth, inner diameter of maximally dilated parenchymal arterioles was reduced by DOCA-salt, suggesting inward remodeling was present. Collectively, the findings suggest the cerebral vasculature is particularly susceptible to dysfunction during DOCA-salt hypertension. Our experiments provide initial insight into previously unrecognized phenomics and mechanisms in a preclinical model of brain RAS activation and low-renin hypertension.

Relevance of the model for human hypertension.

In the recent Global Burden of Disease analysis, hypertension was the greatest risk factor for overall disease burden and health loss worldwide, including stroke and cerebrovascular disease.1, 2 The brain is particularly susceptible to hypertension. For example, based on epidemiology and other evidence, hypertension is a greater risk factor for stroke than other modifiable risk factors including diabetes, tobacco use, hyperlipidemia, or low physical activity (among others).2, 9

Multiple lines of evidence indicate that the RAS is a major contributor to the pathogenesis of essential hypertension – by far the most common form of hypertension.6, 25 Although circulating levels of angiotensin II (Ang II) remain poorly defined,26 hypertensive patients can be categorized as having low, normal, or high levels of plasma renin activity.10 Plasma renin is reduced in about one-third of individuals with essential hypertension.10 Hypertension with low plasma renin is even more prevalent in specific subgroups including the elderly, Blacks, and resistant hypertension.10, 27 For example, about 60% of individuals with resistant hypertension have low circulating renin and increased salt sensitivity.27 Considering the demographics, modeling these groups is of particular interest,28 as mechanistic differences may contribute to the concomitant higher incidence of cerebrovascular disease and loss of brain health.28

The DOCA-salt model is one of only a few models of low-renin hypertension. DOCA-salt increases brain angiotensinergic signaling and Ang II levels in CSF, with neurohumoral activation and volume expansion.11, 12 Mice treated with DOCA-salt phenocopy features seen in transgenic mice expressing human renin in a neuron-specific manner.29 Although a DOCA model of hypertension was described in the 1940’s,30 relatively little effort has been made to use such models to study the biology of the cerebral circulation. Lastly, we used a version with distinct advantages (see below). We confirmed key features in the present study, elevated brain RAS activity (increased brain Agt mRNA), with suppressed peripheral RAS activity (decreased renal Ren1 mRNA).11

Genetic mechanisms contribute to essential hypertension.31 Because we did not study genetic mechanisms during our initial characterization of large and small vessels in the current model, the data do not exclude or implicate such influences. That low-renin hypertension is common in select groups is consistent with genetic influences. We anticipate a fruitful direction for future studies of vascular disease in brain will be to treat specific genetic models with DOCA-salt.

Diets high in salt are a risk factor for stroke,1, 2 increasing the relevance of DOCA-salt model. Salt sensitivity of arterial pressure is present in a large percentage of hypertensive patients, with an even higher percentage in older individuals and in Blacks.32 In the current model, total fluid and sodium intake are increased substantially by DOCA treatment.11

Although the first description of the model did not,30 most studies using DOCA include a nephrectomy to increase severity of the model, often providing only salt H2O to drink.12 We used no nephrectomy, and provided the choice of tap H2O or H2O with 0.9% NaCl to drink.11, 14 There are advantages to this design. The increase in arterial pressure is less severe, arguably relevant to a greater percentage of hypertensive humans, particularly with recent lowering of treatment guidelines. This variation of the model may be more selective in that it appears to only (or predominantly) affect cerebral blood vessels. With a nephrectomy, animals become more hypertensive and abnormalities are present in peripheral blood vessels.33, 34 Thus, our modified model facilitates studying effects of the brain RAS on the local vasculature, while having relevance for a substantial portion of individuals with essential hypertension. Despite these strengths, no preclinical model exhibits all features of essential hypertension in humans.

Although hypertension is more common in older humans, we did not combine hypertension with aging as we tested our main hypothesis. The vast majority of studies of hypertension have not used this combination. Because aging alone has effects on endothelial function in cerebral vessels17, 21, 35 and may activate brain RAS,36 we felt to study the vascular impact of the brain RAS, it was logical to initially use adult mice. Studies of hypertension with aging would require a different design since both groups would exhibit substantial phenotypes at baseline. Still, this is a potentially important direction for future studies. In this context, it is noteworthy that even early onset hypertension is a risk factor for cognitive decline later in life.37 Thus, defining mechanisms of cerebrovascular disease at both earlier (adult) and later stages of life is arguable important in understanding the overall impact of hypertension on brain health.

Functional changes in the vasculature.

Cerebrovascular changes, including endothelial dysfunction, occur in other models of hypertension.3, 22 Data on endothelial function in cerebral vessels from hypertensive humans are rare. Consistent with the current study, vertebral arteries from hypertensive humans (the sex of the subjects was not provided) exhibit impaired dilation to acetylcholine.38 Regarding preclinical models, DOCA treatment (without nephrectomy, but with salt in the drinking H2O) impaired neurovascular coupling and vascular responses to acetylcholine in mice.39 In another study, dilation was impaired in the MCA (to adenosine diphosphate) and parenchymal arterioles (to acetylcholine) from nephrectomized rats (given DOCA and salt in drinking H2O).40 Neither of these studies examined underlying mechanisms.

Dilation of cerebral arteries, pial arterioles, and parenchymal arterioles to acetylcholine is mediated by eNOS-derived NO in varied species, from mice to humans.4, 17, 22, 24 In mice treated with DOCA-salt, endothelium-dependent vasodilation (NO-dependent) was impaired in cerebral arteries and parenchymal arterioles, whereas mesenteric arteries were unaffected. In addition, effects of DOCA-salt were sex-dependent with no changes in cerebral arteries from females. As suggested by experts in the area, sex differences in this initial study were observed using adult male and female mice with intact gonads.41 Females were studied randomly, with no consideration for potential differences in the estrous cycle. Follow-up studies could examine effects of sex hormones or sex chromosomes in these sex-dependent phenotypes. Previous studies that examine effects of DOCA-salt on cerebral vessels did not include females.39, 40

Considering DOCA-salt activates the brain RAS, we tested whether RAS played a causal role in endothelial changes, focusing on the AT1R, as a mediator of potential endothelial effects. Our mRNA and NZ44 reporter mice data support the concept that DOCA-salt increases expression of Agtr1a and other RAS components within the brain vasculature itself. Consistent with these findings, inhibition of AT1R with losartan in the organ bath reversed endothelial dysfunction in cerebral arteries from mice treated with DOCA-salt. In contrast, losartan did not restore endothelial function in aorta following DOCA-salt treatment.34 Thus, key mechanistic differences may contribute to endothelial dysfunction following DOCA-salt in the cerebral circulation. In relation to sex-dependent effects, it is interesting that cerebral arteries from men contract to a greater degree than arteries from women in response to exogenous Ang II.42

Collectively, these data suggest DOCA-salt impaired eNOS-mediated dilation in multiple segments of the vascular tree in brain. The functional data was supported by reductions in vascular levels of p-Akt. Similar reductions in endothelium-dependent vasodilation to acetylcholine and p-Akt occur in arteries from humans with essential hypertension.43 In contrast, vasodilation of parenchymal arterioles to NS-309 results from activation of endothelial SK/IK channels and endothelium-dependent hyperpolarization.17, 44 This response was intact after DOCA-salt, suggesting despite central RAS activation, at least one vasodilator pathway remains functional and could potentially serve as a therapeutic target in small vessel disease, a state where endothelial dysfunction and reductions in cerebral blood flow (hypoperfusion) occur.3, 45

The brain RAS might affect other vasodilator mechanisms. Effects on neuronal NOS in perivascular nerves or intrinsic nerves in the parenchyma is one possibility. Agonists used in the current study (acetylcholine, NS-309) produce endothelium-dependent vasodilation.44, 46 Inhibition of neuronal NOS does not attenuate vascular effects of acetylcholine,47 consistent with an eNOS-mediated mechanism. Thus, it seems unlikely that neuronal NOS contributed to vasodilation to these stimuli. Having said that, DOCA-salt treatment impaired neurovascular coupling,39 a response where neuronal NOS has been implicated to play a significant role.48

Structural changes in the microvasculature.

Changes in cerebral microvascular structure occur commonly during hypertension,3, 4 affect vasodilator reserve, microvascular pressure, and can be a predictor of clinical events.3, 49 In the current study, inner diameter of maximally dilated parenchymal arterioles was reduced by DOCA-salt, an effect that was similar to that seen in small pial arterioles in genetic or pharmacological models of Ang II-dependent hypertension, although the degree of hypertension is less in the current model.3, 11, 14, 50 In contrast, diameter of small mesenteric arteries was not reduced in the model.14 In nephrectomized rats treated with DOCA-salt, no significant change in passive lumen diameter of parenchymal arterioles was reported.40 This lack of remodeling was surprising since the level of hypertension produced was substantial.40 In another study from the same group, Ang II-induced hypertension reduced lumen diameter of parenchymal arterioles and the posterior cerebral artery.51

We assume vascular changes after DOCA-salt are not primarily due to the modest elevation in arterial pressure in the model.11, 14 First, inhibitory effects on acetylcholine-induced vasodilation in the DOCA-salt model are greater that in a model treated with a dose of Ang II that produced a larger increase in arterial pressure.19 Second, other lines of evidence have shown that effects due to activation of the central RAS can occur independent of changes in arterial pressure.11 Third, if vascular changes were simply due to increased blood pressure, one would expect similar changes in other organs. However, vascular function in mesenteric arteries after DOCA-salt was not different from controls. Still, we cannot exclude the possibility that increased blood pressure had some direct effects on the cerebral vasculature. If such effects were present, data from the mesenteric artery provide strong evidence that cerebral vessels would be much more sensitive to moderate increases in blood pressure, a new and interesting finding on its own.

Implications for brain function.

Through effects on local vascular resistance, endothelial cells influence basal blood flow, mediate responses to signaling and therapeutic molecules, and are essential for neurovascular coupling.52 In addition, these cells exert pleiotropic effects on glia, neurons, synapses, and molecules including tau.52 As a consequence, endothelial cells have emerged as key determinants of cognition and brain health.4, 52 Because hypertension is a leading risk factor for cerebrovascular disease and loss of brain health,1, 2 defining mechanisms that underlie changes in large and small vessel biology is potentially important with significant implications. The current study provides insight into previously unrecognized phenomics and mechanisms in a preclinical model of central RAS activation and low-renin hypertension.

Why are effects of hypertension on the cerebral circulation so prominent? Although the central RAS is important in relation to control of blood pressure, its impact on the local brain vasculature has never been defined. Considering the current findings, we hypothesize that the cerebral vasculature gets multiple ‘hits’ with central RAS activation. One hit would be effects of chronically increased intravascular pressure. Even moderate hypertension may have physiological effects (i.e., suppressed renal Ren1 expression) in the current model. Cerebral vessels receive a second hit due to local effects of central and/or cerebrovascular RAS activation. We suggest this combination of systemic and local mechanisms results in greater phenotypic changes in the cerebral circulation. In this sense, the current model may be more representative of hypertension in a substantial percentage of humans with essential hypertension. Lastly, activation of the brain RAS and the AT1R occur in conditions beyond hypertension, each known to affect the cerebral vasculature. For example, there is evidence for activation of the brain RAS during aging, diabetes, preeclampsia, and Alzheimer’s disease.21, 36, 53–55 Thus, central RAS activation may represent a common underlying mechanism that promotes loss of endothelial and ultimately brain health with diverse etiology.

Supplementary Material

Sources of Funding

During the conduction of this study and preparation of this manuscript, the authors were supported by the National Institutes of Health (NS-096465, NS-108409, HL-134850, HL-084207), the Department of Veterans Affairs (BX001399), the Fondation Leducq (Transatlantic Network of Excellence) and the American Heart Association (18EIA33890055).

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- Ang II

angiotensin II

- AT1R

angiotensin II type 1 receptor

- DOCA

deoxycorticosterone acetate

- eNOS

endothelial nitric oxide synthase

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- MCA

middle cerebral artery

- NO

nitric oxide

- RAS

renin-angiotensin system

Footnotes

Disclosures

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

References

- 1.Mills KT, Stefanescu A, He J. The global epidemiology of hypertension. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2020;16:223–237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yusuf S, Joseph P, Rangarajan S, Islam S, Mente A, Hystad P, Brauer M, Kutty VR, Gupta R, Wielgosz A, et al. Modifiable risk factors, cardiovascular disease, and mortality in 155 722 individuals from 21 high-income, middle-income, and low-income countries (PURE): A prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:795–808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Silva TM, Faraci FM. Microvascular dysfunction and cognitive impairment. Cell Molec Neurobiol. 2016;36:241–258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hu X, De Silva TM, Chen J, Faraci FM. Cerebral vascular disease and neurovascular injury in ischemic stroke. Circ Res. 2017;120:449–471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gottesman RF, Schneider AL, Albert M, Alonso A, Bandeen-Roche K, Coker L, Coresh J, Knopman D, Power MC, Rawlings A, et al. Midlife hypertension and 20-year cognitive change: The atherosclerosis risk in communities neurocognitive study. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71:1218–1227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karnik SS, Unal H, Kemp JR, Tirupula KC, Eguchi S, Vanderheyden PM, Thomas WG. Angiotensin receptors: Interpreters of pathophysiological angiotensinergic stimuli. Pharmacol Rev. 2015;67:754–819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nakagawa P, Gomez J, Grobe JL, Sigmund CD. The renin-angiotensin system in the central nervous system and its role in blood pressure regulation. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2020;22:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Williams B, MacDonald TM, Morant SV, Webb DJ, Sever P, McInnes GT, Ford I, Cruickshank JK, Caulfield MJ, Paadmanabhan S, et al. Endocrine and haemodynamic changes in resistant hypertension, and blood pressure responses to spironolactone or amiloride: The Pathway-2 mechanisms substudies. Lancet Diabetes Endo. 2018;6:464–475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Endres M, Heuschmann PU, Laufs U, Hakim AM. Primary prevention of stroke: Blood pressure, lipids, and heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:545–552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alderman MH, Madhavan S, Ooi WL, Cohen H, Sealey JE, Laragh JH. Association of the renin-sodium profile with the risk of myocardial infarction in patients with hypertension. New Engl J Med. 1991;324:1098–1104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grobe JL, Buehrer BA, Hilzendeger AM, Liu X, Davis DR, Xu D, Sigmund CD. Angiotensinergic signaling in the brain mediates metabolic effects of deoxycorticosterone (DOCA)-salt in C57 mice. Hypertension. 2011;57:600–607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Basting T, Lazartigues E. DOCA-salt hypertension: An update. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2017;19:32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gonzalez AD, Wang G, Waters EM, Gonzales KL, Speth RC, Van Kempen TA, Marques-Lopes J, Young CN, Butler SD, Davisson RL, et al. Distribution of angiotensin type 1a receptor-containing cells in the brains of bacterial artificial chromosome transgenic mice. Neurosci. 2012;226:489–509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ketsawatsomkron P, Keen HL, Davis DR, Lu KT, Stump M, De Silva TM, Hilzendeger AM, Grobe JL, Faraci FM, Sigmund CD. Protective role for tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-4, a novel peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ target gene, in smooth muscle in deoxycorticosterone acetate-salt hypertension. Hypertension. 2016;67:214–222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Silva TM, Ketsawatsomkron P, Pelham C, Sigmund CD, Faraci FM. Genetic interference with peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ in smooth muscle enhances myogenic tone in the cerebrovasculature via a Rho kinase-dependent mechanism. Hypertension. 2015;65:345–351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Silva TM, Kinzenbaw DA, Modrick ML, Reinhardt LD, Faraci FM. Heterogeneous impact of ROCK2 on carotid and cerebrovascular function. Hypertension. 2016;68:809–817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Silva TM, Modrick ML, Dabertrand F, Faraci FM. Changes in cerebral arteries and parenchymal arterioles with aging: Role of Rho kinase 2 and impact of genetic background. Hypertension. 2018;71:921–927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Silva TM, Modrick ML, Ketsawatsomkron P, Lynch C, Chu Y, Pelham CJ, Sigmund CD, Faraci FM. Role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ in vascular muscle in the cerebral circulation. Hypertension. 2014;64:1088–1093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson AW, Kinzenbaw DA, Modrick ML, Faraci FM. Small-molecule inhibitors of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 protect against angiotensin II-induced vascular dysfunction and hypertension. Hypertension. 2013;61:437–442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miura H, Wachtel RE, Liu Y, Loberiza FR Jr., Saito T, Miura M, Gutterman DD. Flow-induced dilation of human coronary arterioles: Important role of Ca2+-activated K+ channels. Circulation. 2001;103:1992–1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Modrick ML, Didion SP, Sigmund CD, Faraci FM. Role of oxidative stress and AT1 receptors in cerebral vascular dysfunction with aging. Am J Physiol. 2009;296:H1914–1919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Faraci FM. Protecting against vascular disease in brain. Am J Physiol 2011;300:H1566–1582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fulton D, Gratton JP, McCabe TJ, Fontana J, Fujio Y, Walsh K, Franke TF, Papapetropoulos A, Sessa WC. Regulation of endothelium-derived nitric oxide production by the protein kinase Akt. Nature. 1999;399:597–601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elhusseiny A, Hamel E. Muscarinic-but not nicotinic-acetylcholine receptors mediate a nitric oxide-dependent dilation in brain cortical arterioles: A possible role for the M5 receptor subtype. J Cerebral Blood Flow Metabol. 2000;20:298–305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hall JE, Granger JP, do Carmo JM, da Silva AA, Dubinion J, George E, Hamza S, Speed J, Hall ME. Hypertension: Physiology and pathophysiology. Compr Physiol. 2012;2:2393–2442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reckelhoff JF, Romero JC. Role of oxidative stress in angiotensin-induced hypertension. Am J Physiol. 2003;284:R893–912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carey RM, Calhoun DA, Bakris GL, Brook RD, Daugherty SL, Dennison-Himmelfarb CR, Egan BM, Flack JM, Gidding SS, Judd E, et al. Resistant hypertension: Detection, evaluation, and management: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Hypertension. 2018;72:e53–e90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maraboto C, Ferdinand KC. Update on hypertension in African-Americans. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2020;63:33–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grobe JL, Grobe CL, Beltz TG, Westphal SG, Morgan DA, Xu D, de Lange WJ, Li H, Sakai K, Thedens DR, et al. The brain renin-angiotensin system controls divergent efferent mechanisms to regulate fluid and energy balance. Cell Metabol. 2010;12:431–442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Selye H, Hall CE, Rowley EM. Malignant hypertension produced by treatment with desoxycorticosterone acetate and sodium chloride. Can Med Assoc J. 1943;49:88–92 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Padmanabhan S, Dominiczak AF. Genomics of hypertension: The road to precision medicine. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2020;18:235–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oh YS, Appel LJ, Galis ZS, Hafler DA, He J, Hernandez AL, Joe B, Karumanchi SA, Maric-Bilkan C, Mattson D, et al. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute working group report on salt in human health and sickness building on the current scientific evidence. Hypertension. 2016;68:281–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ko EA, Amiri F, Pandey NR, Javeshghani D, Leibovitz E, Touyz RM, Schiffrin EL. Resistance artery remodeling in deoxycorticosterone acetate-salt hypertension is dependent on vascular inflammation: Evidence from m-CSF-deficient mice. Am J Physiol. 2007;292:H1789–1795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Somers MJ, Mavromatis K, Galis ZS, Harrison DG. Vascular superoxide production and vasomotor function in hypertension induced by deoxycorticosterone acetate-salt. Circulation. 2000;101:1722–1728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mayhan WG, Arrick DM, Sharpe GM, Sun H. Age-related alterations in reactivity of cerebral arterioles: Role of oxidative stress. Microcirc. 2008;15:225–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fan LM, Geng L, Cahill-Smith S, Liu F, Douglas G, McKenzie CA, et al. Nox2 contributes to age-related oxidative damage to neurons and the cerebral vasculature. J Clin Invest. 2019;129:3374–3386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suvila K, Lima JAC, Yano Y, Tan ZS, Cheng S, Niiranen TJ. Early-but not late-onset hypertension is related to midlife cognitive function. Hypertension. 2021;77:972–979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Charpie JR, Schreur KD, Papadopoulos SM, Webb RC. Acetylcholine induces contraction in vertebral arteries from treated hypertensive patients. Clin Exp Hypertens. 1996;18:87–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Faraco G, Park L, Zhou P, Luo W, Paul SM, Anrather J, Iadecola C. Hypertension enhances Aß-induced neurovascular dysfunction, promotes ß-secretase activity, and leads to amyloidogenic processing of APP. J Cerebral Blood Flow Metabol. 2016;36:241–252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Matin N, Pires PW, Garver H, Jackson WF, Dorrance AM. DOCA-salt hypertension impairs artery function in rat middle cerebral artery and parenchymal arterioles. Microcirc. 2016;23:571–579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mauvais-Jarvis F, Arnold AP, Reue K. A guide for the design of pre-clinical studies on sex differences in metabolism. Cell Metabol. 2017;25:1216–1230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ahnstedt H, Cao L, Krause DN, Warfvinge K, Saveland H, Nilsson OG, Edvinsson L. Male-female differences in upregulation of vasoconstrictor responses in human cerebral arteries. PloS One. 2013;8:e62698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xiao L, Dong JH, Teng X, Jin S, Xue HM, Liu SY, et al. Hydrogen sulfide improves endothelial dysfunction in hypertension by activating peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor delta/endothelial nitric oxide synthase signaling. J Hypertens. 2018;36:651–665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Villalba N, Sonkusare SK, Longden TA, Tran TL, Sackheim AM, Nelson MT, Wellman GC, Freeman K. Traumatic brain injury disrupts cerebrovascular tone through endothelial inducible nitric oxide synthase expression and nitric oxide gain of function. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3:e001474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Poggesi A, Pasi M, Pescini F, Pantoni L, Inzitari D. Circulating biologic markers of endothelial dysfunction in cerebral small vessel disease. J Cerebral Blood Flow Metabol. 2016;36:72–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Faraci FM, Heistad DD. Regulation of the cerebral circulation: Role of endothelium and potassium channels. Physiol Rev. 1998;78:53–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang F, Xu S, Iadecola C. Role of nitric oxide and acetylcholine in neocortical hyperemia elicited by basal forebrain stimulation: Evidence for an involvement of endothelial nitric oxide. Neurosci. 1995;69:1195–1204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Iadecola C The neurovascular unit coming of age: A journey through neurovascular coupling in health and disease. Neuron. 2017;96:17–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mulvany MJ. Small artery remodelling in hypertension. Basic Clin Pharm Toxicol. 2012;110:49–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Baumbach GL, Sigmund CD, Faraci FM. Cerebral arteriolar structure in mice overexpressing human renin and angiotensinogen. Hypertension. 2003;41:50–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Diaz-Otero JM, Fisher C, Downs K, Moss ME, Jaffe IZ, Jackson WF, Dorrance AM. Endothelial mineralocorticoid receptor mediates parenchymal arteriole and posterior cerebral artery remodeling during angiotensin II-induced hypertension. Hypertension. 2017;70:1113–1121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.De Silva TM, Faraci FM. Contributions of aging to cerebral small vessel disease. Annu Rev Physiol. 2020;82:275–295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Arrick DM, Sharpe GM, Sun H, Mayhan WG. Losartan improves impaired nitric oxide synthase-dependent dilatation of cerebral arterioles in type 1 diabetic rats. Brain Res. 2008;1209:128–135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ciampa E, Li Y, Dillon S, Lecarpentier E, Sorabella L, Libermann TA, Karumanchi SA, Hess PE. Cerebrospinal fluid protein changes in preeclampsia. Hypertension. 2018;72:219–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Papadopoulos P, Tong XK, Imboden H, Hamel E. Losartan improves cerebrovascular function in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease with combined overproduction of amyloid-ß and transforming growth factor-ß1. J Cerebral Blood Flow Metabol. 2017;37:1959–1970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.