Abstract

Prior research has examined the high healthcare needs and vulnerabilities faced by survivors of commercial sexual exploitation (CSE), yet their perspectives are frequently absent. We sought to understand the narratives and views of individuals impacted by CSE on their bodies, health, and motivations to seek healthcare treatment. Twenty-one girls and young women ages 15 to 19 with self-identified histories of CSE participated in the study. All participants had current or prior involvement in the juvenile justice and/or child welfare systems. Data collection included brief questionnaires, followed by semi-structured individual interviews. The interviews took place between March and July 2017 and were analyzed using iterative and inductive techniques, utilizing the shared decision-making model as a guide. “Fierce Autonomy” emerged as a core theme, depicting how past traumas and absence of control led the girls and young women to exercise agency and reclaim autonomy over decisions affecting their health.

Introduction

Qualitative health research that centers on first-person accounts and personal narratives can play a meaningful role in improving health-related treatment and outcomes (Bantjes, 2019; Greenhalgh et al., 2016; Morse, 2016), especially for youth impacted by commercial sexual exploitation (CSE; Barnert, Kelly, Godoy, Abrams, & Bath, 2019; Ijadi-Maghsoodi, Bath, Cook, Textor, & Barnert, 2018). Sex trafficking, referred to as CSE, is defined as using force, fraud, or coercion to induce sex acts in exchange for items of value. Notably, for young people less than 18 years of age, any commercial exchange of sex acts is considered CSE, regardless of force, fraud, or coercion (Trafficking Victims Protection Act of 2000, 2000). CSE is a grave form of exploitation, and when youth less than 18 are the victims it legally constitutes child abuse and statutory rape (IOM & NRC, 2013).

Predisposing factors to CSE include child maltreatment, an unstable home environment, lack of familial supervision, substance use, homelessness, running away, and identification as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or queer (LGBTQ). These risk factors are also associated with juvenile justice and child welfare systems involvement, which further compound youths’ susceptibility to CSE (Bounds et al., 2015; Fedina, Williamson, & Perdue, 2016; Greenbaum & Crawford-Jakubiak, 2015; Varma et al., 2015; WestCoast Children’s Clinic, 2012). Risk factors are frequently co-occurring and, taken together, increase vulnerability and mental, physical, and reproductive healthcare needs.

The continuum of harmful experiences endured in childhood and throughout the course of exploitation often results in complex trauma that leads to multifarious healthcare needs. Prior studies have confirmed survivors’ significant health-related risks and needs, and documented frequency of utilizing and barriers to accessing healthcare services (Barnert, Kelly, Ports, Godoy, Abrams, & Bath, 2019; Ijadi-Maghsoodi et al., 2018; Lederer & Wetzel, 2014; Ravi, Pfeiffer, Rosner, & Shea, 2017a; Varma et al., 2015). Though healthcare treatment may be available to youth and young adults impacted by CSE, a multitude of structural, environmental, and internal barriers to utilization and engagement (i.e. “buy-in”) into treatment remain (Barnert, Kelly, Godoy, Abrams, & Bath, 2019). As such, the lack of timely care may lead to sequelae such as suicidality, worsening mental and physical health issues, and destructive substance use (Cook et al., 2018; Greenbaum & Crawford-Jakubiak, 2015; Ijadi-Maghsoodi et al., 2018; Powell, Asbill, Loius, & Stoklosa, 2018; Ravi et al., 2017a, 2017b).

Despite knowledge on frequency of healthcare usage, extant literature is notably lacking in describing how youth impacted by CSE perceive their own healthcare needs, as influenced by past experiences of trauma and violence, their decisions to seek care, and the role of personal agency in their decision-making process. Due to their involvement in the child welfare and juvenile justice systems, youth impacted by CSE are often disenfranchised from decision-making, which can hamper their “buy-in” or engagement in care. Thus, understanding the perceptions and preferences of youth impacted by CSE, a marginalized and vulnerable population, is essential in developing effective health-related outreach strategies that can effectively engage youth in care.

In this study, we sought to move the perspectives of survivors from margin to center (Hooks, 1984), and reposition them as experts in understanding how their access, utilization, and engagement in healthcare can be understood and improved. Through these perspectives, we build upon the shared decision-making (SDM) framework (Charles, Gafni, & Whelan, 1997) to formulate a conceptual model illustrating how girls and young women impacted by CSE understand their own healthcare needs and, in light of their spectrum of victimization, how they make decisions around caring for their own bodies. This sample included cisgender females ages 15 through 19. Given this age range, we employ the term “girls and young women” to describe the focal group. This article addresses the following research questions:

How do girls and young women with histories of CSE view their own health and wellness?

How do their life histories and past traumas influence their understanding of their healthcare needs?

How do girls and young women experiencing CSE decide to seek healthcare?

Literature Review

Vulnerabilities to Exploitation Exacerbate Health-Related Needs

Though any child or young person can fall prey to exploitation, there are a host of interacting factors (i.e. individual, familial, community, and societal) that make certain populations more vulnerable. Prominent antecedents to CSE include histories of child maltreatment, complex trauma involving multiple perpetrators, and severe and/or chronic trauma (Greenbaum, Yun, & Todres, 2018). The WestCoast Children’s Clinic (2012) found that more than 75% of youth with histories of CSE in their sample (N=113) had experienced child abuse or neglect, with 70% experiencing multiple incidents of maltreatment. Childhood trauma included severe or repeated incidents of neglect (56%), sexual abuse (53%), emotional abuse (53%), and physical abuse (52%; WestCoast Children’s Clinic, 2012). Individuals impacted by complex trauma may suffer from symptoms such as anxiety, depression, dissociation, self-hatred, and problematic substance use (Courtois, 2004). These factors can contribute to risky behaviors and lead to re-victimization, directly affecting mental and physical health in adolescence and young adulthood (Courtois, 2004; IOM & NRC, 2013; Lalor & McElvaney 2010). Child maltreatment and trauma may lead to instability in the home and adverse health experiences and outcomes, all of which increase vulnerability to CSE.

In addition, unstable homes, lack of familial support, and gaps in supervision are catalysts to both systems involvement (i.e. in the juvenile or child welfare system) and exploitation, exacerbating a myriad of health issues. Adverse health effects are not mutually exclusive—and comorbidity, defined as the presence of two or more diagnoses, may further exacerbate vulnerabilities and health needs among youth impacted by CSE (Kelly et al., 2017; Lalor & McElvaney, 2010; National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2012; Rafferty, 2008; Stoklosa, MacGibbon, & Stoklosa, 2017). Mechanisms for these negative health effects are multi-faceted and can begin prior to and sustained throughout the exploitation.

Health Outcomes of Exploitation

Exploiters, including sex purchasers, often employ a range of harmful tactics affecting youths’ physical, mental, and emotional health. Youth experiencing CSE are known to endure repeated threats of harm, maltreatment (e.g. deprivation of basic needs, isolation), physical and sexual violence (e.g. gang rape, stabbing, burning), and harmful practices (e.g. branding) that can lead to extreme injury and death (Bounds et al., 2015; Greenbaum & Crawford-Jakubiak, 2015; Muftic & Finn, 2013; Ravi et al., 2017a). Victims of CSE are regularly subjected to multiple forms of violence. Lederer & Wetzel (2014) found that approximately 92% of survivors surveyed (N=106) were subjected to at least one form of violence, including forced sex (81.6%), punching (73.8%), beatings (68.9%), and forced unprotected sex (68%). As a result, survivors of CSE are prone to a sequelae of health issues that result from the exploitation, and likely have high rates of underlying unmet health needs attributed to their social vulnerabilities and histories of violent victimization. Survivors also reported at least one physical health issue (99%), including general health issues (86%) and violence-related, physical injuries (69%) while exploited (Lederer & Wetzel, 2014). Despite these grave risks and health needs, little is known about how survivors conceptualize their health-related needs, or when and how agency is exercised in treatment decisions.

Restructuring Youths’ Agency in Healthcare Decision-making

Healthcare decision-making in relation to youth impacted by CSE is limited and under-researched. Available literature focused on youth (Bay-Cheng & Fava, 2014; Coyne, 2008; Coyne, Amory, Kiernan, & Gibson, 2014) and their service providers (Crickard, O’Brien, Rapp, & Holmes, 2010; Sapiro, Johnson, Postmus, & Simmel, 2016) offers limited but critical insight into how youths’ agency is perceived in healthcare settings and in service provision, and exerted in decision-making. Review about adolescent agency found that youth are often marginalized in the healthcare consultation and decision-making process. Even when there is expressed desire to actively participate, youth are often not supported by parents or healthcare professionals (Coyne, 2008). Furthermore, service providers tend to hold divergent beliefs about the degree of agency youth impacted by CSE should hold over decisions that affect their lives. As such, service providers may find it difficult to reconcile that victimization does not preclude a youth’s ability to exercise agency in decision-making (Bay-Cheng & Fava, 2014). Service providers’ divergent beliefs and disparate treatment ultimately influences the level of autonomy afforded to youth and the providers’ approach to care (Sapiro et al., 2016). The continuum of autonomy, agency, and power is nuanced and complex, especially as it relates to healthcare decision-making for youth. There are, however, continuing efforts to restructure the patient-provider power dynamic through a shared decision-making (SDM) framework that includes youth impacted by CSE.

The SDM model increases patients’ agency and autonomy in the decision-making process by repositioning the patients’ voices to the fore and upholding their preferences as the primary driver for care planning (Charles, Gafni, & Whelan, 1997). The American Academy of Pediatrics has affirmed that children and their parents should play an active role in making decisions affecting youths’ health and uphold “the experience, perspective and power of children” (Katz & Webb, 2016). Though opportunities are often limited, research has documented youths’ desire for choice in healthcare decisions, consistent with SDM (Coyne et al., 2014). Extant literature also emphasizes utilizing SDM techniques as a mechanism for increasing active participation among youth (Crickard et al., 2010), including youth with histories of CSE (Barnert et al., 2019; Sahl & Knoepke, 2018). Further, patients with greater autonomy and perceived competence about their health are more likely to follow healthcare recommendations and exhibit increased satisfaction (Arevian et al., 2018; Bejarando et al., 2015; Brand & Stiggelbout, 2013). Yet, when and how autonomy is exerted by youth impacted by CSE while making healthcare decisions is largely unknown. The SDM model was used as a guide to understanding an alternative approach to engaging individuals in healthcare decisions regarding their treatment.

Method

Design and Ethics

In this article, we examine qualitative interview data that sought to understand girls and young women with histories of CSE perspective on their bodies, health, and drivers to seek and engage in care. We present salient qualitative findings analyzed through iterative and inductive techniques. The research was conducted in a large southwestern county of the United States, in partnership with a juvenile specialty court, two foster care group home agencies, and a local service provider serving youth impacted by CSE. All study procedures, including consent, confidentiality, and instrumentation, were approved by our university’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) and the county superior court, juvenile division.

Recruitment and Sampling

The goal was to identify and invite a purposive sample of youth and young adults between the ages of 13 and 22 who self-identified as commercially sexually exploited. Potential participants were invited to take part in the study through the community partner entities. The research team first provided the community partners with the study information, requesting they gauge interest among potential participants. Next, researchers met individually with potential participants (n=25) in a private room and provided information packets describing the study. After confirming interest, the researchers then conducted a three-question eligibility screening to confirm potential participants met inclusion criteria, specifically: 1) 13 years old or older; 2) 22 years old or younger; and 3) had exchanged sex for anything of value. Of the initial 25 girls and young women interested in participating, 21 passed the eligibility screen. Four young women were excluded because they did not identify as having a history of CSE.

A total of 21 girls and young women participated in individual, qualitative interviews during the study period (March – July 2017). The final sample of 21 cisgender girls and young women were between ages 15 and 19 and predominately identified as African-American or of Hispanic descent (see Table 1). To uphold the safety and confidentiality of the girls and young women who participated in the study, all names have been changed to pseudonyms and participants are not identifiable. Transgender individuals and cisgender young men were not purposefully excluded from the study, but rather were not present at these agencies when the research team invited participants. Although not part of the eligibility criteria, the 21 girls and young women who participated in the study were all involved in the child welfare and/or juvenile justice system during or prior to the study period. This was likely due to inviting youth from the specialty court and group homes, as well as the high levels of system-involvement in the overall population.

Table 1.

Demographics of Interviewed Girls and Young Women (N=21)

| Characteristics | n |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| 15 | 3 |

| 16 | 5 |

| 17 | 7 |

| 18 | 4 |

| 19 | 1 |

| Not reported | 1 |

| Hispanic or Latina | |

| Yes | 7 |

| No | 14 |

| Race | |

| American Indian | 2 |

| Asian | 1 |

| African American | 14 |

| White | 4 |

| Other | 2 |

| Unknown | 3 |

Procedures

Preceding data collection, participants completed the informed consent process. The same assent/consent form was used for youth who were younger and older than 18. During the consent process research team members reviewed the assent/consent form, responded to emergent inquiries, and asked youth to sign on their own behalf. Since we recruited participants through two residential group homes and a specialty court program, most participants were residing in out-of-home care placements and were under the jurisdiction of the juvenile court system. Due to the frequency of involvement in the child welfare system and difficulty locating parents in a timely manner (as youth in the child welfare system risk frequent re-locate in housing) and, at times, strained communication with their families, the IRB and juvenile court waived parental consent for those under 18 years of age. The girls and young women were provided with light refreshments during the interview and a $25 gift card at interview completion. Those who consented to participate completed a brief closed-ended questionnaire and then researchers conducted one-on-one interviews. Interview length ranged from 30 to 60 minutes. With participant permission, all interviews were digitally-recorded on portable recording devices.

Instrumentation

The semi-structured interview guide was developed and piloted through an iterative team process. The semi-structured interview guide had three distinct sections, capturing the participants’: 1) views on health; 2) healthcare access; and 3) recommendations for improving access to care. First, the girls and young women were asked to describe their views on safety and health. Familial histories, backgrounds in systems of care, and experiences while exploited were explored, as they related to the participants’ ability or inability to access healthcare services. Researchers used additional probes and conversational strategies to clarify youths’ perspectives and understanding of healthcare seeking behaviors and attitudes. Interviews were conducted until thematic saturation was achieved, meaning there was consensus among the research team that no new ideas, patterns, or themes were identified as interviews continued (Morse, 1995).

Researchers conducting interviews had research and/or direct service experience and training to provide trauma-informed care to vulnerable populations and respond to emergent adverse events. Additionally, the researchers reflected the sex, gender, and/or ethnic and racial composition of participants; as such, the interviewers were cisgender females primarily from ethnic minority backgrounds.

Data Analysis

Interviews were transcribed verbatim using a third-party transcription service and were checked for accuracy. All personal identifiers were removed. Research team members had several large group meetings to derive analytic categories from the data and develop an initial codebook of themes. The codebook was refined using iterative thematic analysis as guided by Charmaz’s (2014) work in constructivist grounded theory. Once the team reached consensus about the codebook, a two-member team coded each interview transcript independently using a collaborative platform, Dedoose software (Version 8.1.14, Manhattan Beach, CA). Points of overlap or contention with codes were raised to the team and subsequently refined. Findings were discussed in weekly research team meetings, during which codes were organized into categories.

Using a constructivist grounded theoretical framework, the research team members interpreted the meaning of the data with an understanding that the data are constructions of experience (Charmaz, 2006). Using the SDM as an overarching framework, to explore participants’ perspectives and preferences, the research team members purposely included raw data in theoretical memos and continued throughout the analysis to ensure the voices and narratives of the girls and young women were at the fore (Charmaz 1995, 2000).

The codebook included 15 major themes and 55 subthemes (see Table 2) that inductively captured the girls and young womens’ experiences and perceptions of healthcare needs prior to, during, and after exploitation. The data were organized into themes that conveyed interactions in a variety of healthcare settings. The emergent themes were influenced by their perceptions of past experiences and current beliefs and views as it pertains to their own bodies and health needs. Using an inductive approach, the conceptual model emerged from the health-related stories shared by the girls and young women from their perspectives. Fierce autonomy emerged as the overarching theme across codes and larger categories, as it was interwoven into the girls and young womens’ views and perceptions of healthcare categories, concerns, and recommendations. To that end, fierce autonomy was the “core experience” (Charmaz, 2006) through the analysis process (see below).

Table 2.

Codebook

| 1. Barriers to care |

| a. External |

| b. Internal |

| 2. Beliefs and Attitudes |

| a. General |

| b. General health |

| c. Reproductive health |

| d. Safety |

| e. Substance use |

| 3. Clinical Setting |

| a. Emergency room |

| b. Home |

| c. Juvenile hall |

| d. Placement |

| e. Planned Parenthood |

| 4. Coping Mechanism |

| a. Self-medication |

| b. Other |

| 5. Facilitators to Care |

| a. External |

| b. Internal |

| 6. Health Category |

| a. Physical health |

| b. Substance use |

| c. Mental health |

| d. Reproductive health |

| 7. Health Concerns |

| a. Abortion |

| b. Headaches |

| c. Menstruation |

| d. Miscarriage |

| e. Parenting |

| f. Pregnancy |

| g. Vaginal symptoms |

| 8. Health Services Received |

| a. Physical health treatment |

| b. Mental health treatment |

| c. Reproductive health treatment |

| d. Substance use treatment |

| 9. Mental Health |

| a. Body image |

| b. Definition |

| c. Self-esteem |

| 10. Mental/Emotional State |

| a. “Messed up” |

| b. Crying |

| c. Depressed |

| d. Somatic symptoms |

| e. Stress |

| 11. Recommendations |

| a. Mental health |

| b. Physical health |

| c. Reproductive health |

| d. Substance use |

| e. Other |

| 12. Risk-Taking Behaviors |

| a. Substance use |

| b. Unprotected sex |

| 13. The Life: In the Life |

| a. Experiences (In the life) |

| b. Triggers (In the life) |

| 14. The Life: Out the Life |

| a. Motivations (Out of the life) |

| b. Success (Out of the life) |

| 15. Trauma |

| a. Childhood sexual abuse |

| b. Physical violence |

| c. Sexual violence |

| d. Suicide attempt |

| e. Witnessed violence |

The research team’s experience in direct service with justice-involved youth, including survivors of CSE, and an understanding of CSE literature, advanced the conceptual model that tied together the participants’ perceptions of past events. To assess confirmability and dependability of the analysis, results were debriefed with experts in the judicial system and healthcare system who were outside of the study team and regularly interact with the focal group. Findings are presented in a literary style in order to sufficiently convey the girls and young women’s narratives (Charmaz, 2000).

Results

Overview of Findings and Conceptual Model

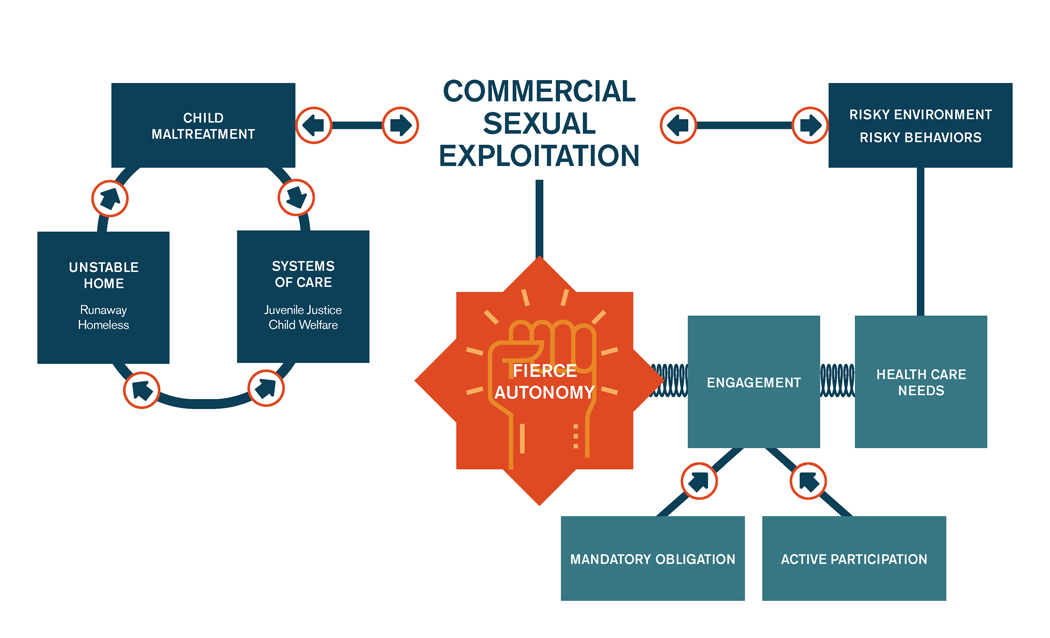

As shown in Figure 1, the inductive “Fierce Autonomy” conceptual model depicts the processes and life circumstances that lead girls and young women with histories of CSE to seek and exercise agency over their bodies and their health. The left-hand side of the model recognizes antecedents to exploitation, an interconnected pattern of adverse experiences in childhood, including child maltreatment, involvement in institutional systems, and unstable housing. These unstable childhood and adolescent experiences were precursors to CSE. In the middle of the model, one can see that the exploitation, coupled with precarious environments and risky behaviors, resulted in high healthcare needs and vulnerabilities. Healthcare needs, influenced by preceding factors (i.e. adverse experiences in childhood, CSE, and risky environments and behaviors) led the girls and young women to engage in healthcare services, when accessible and deemed necessary.

Figure 1.

Fierce autonomy: A conceptual model.

The model also depicts a tension existing between the girls’ and young women’s high health needs and their desire for autonomy; this tension is mediated by their engagement in care and illustrated by the springs. Although healthcare treatment was often framed and experienced as a mandated obligation through the juvenile justice and child welfare systems, the girls and young women also described active participation in healthcare services they sought out independently or with the assistance of family, friends, or group home staff. Both mandated obligation and active participation are shown as drivers that lead to engagement in care, and were conveyed in the themes “facilitator to care” and “health concerns.” Regardless of how services were initiated, the girls and young women expressed a strong desire to be the driver of decisions regarding their healthcare treatment. Past childhood experiences and the exploitation itself fostered a determination to claim agency over decisions pertaining to their health and wellness, all leading to the overarching theme of fierce autonomy, depicted in the center of the model.

Fierce Autonomy

The overarching theme of fierce autonomy reflects the culmination of past experiences that influenced the girls and young women as decision-makers and active drivers of determining when to seek healthcare services. The conceptual model conveys how experiences prior to and during the exploitation shaped their understanding of health, wellness, and urgency of healthcare treatment need. These young women’s lack of agency regarding decision-making in their past was often due to a combination of exploiter control, unstable family backgrounds, or involvement in systems of care. For example, Helen felt frustrated that service providers did not “acknowledge” her input on court-ordered services, but regained a sense of control by disengaging in mandated treatment. The girls and young women shared both extreme and routine violence-related traumatic events that affected their well-being and resulted in high healthcare needs. These healthcare needs were intermittently addressed, at times this was due to a lack of control over their bodies, but in other instances they exercised agency by engaging or disengaging in care.

Past Experiences: Child Maltreatment, Unstable Homes, and Systems of Care

Foundational to the conceptual model are the effects of experiences prior to and during CSE. The girls and young women recalled histories of child maltreatment, unstable homes, and involvement in the child welfare and juvenile justice systems. Adverse experiences in childhood and adolescence often diminished the girls and young women’s autonomy in determining access to healthcare services. These histories, for better or worse, shaped their views on health and wellness, and served as the driver to control the decisions affecting their health and bodies.

The girls and young women reflected on how experiences of childhood maltreatment, particularly physical and sexual abuse, directly led to instability in their homes, involvement in the child welfare system, and impacted their inability to make decisions over their bodies. For example, Arya, a 15-year old African-American girl, experienced molestation as a child, but explained that it was the physical abuse inflicted by her father that catalyzed her entry into foster care. Fifteen-year old Amee attributed her self-described promiscuity to childhood molestation. Danielle, a 16-year old Latina, recalled medical treatment related to rape prior to entering foster care. Danise, a 17-year old African-American young woman, discussed childhood molestation and rape that affected her and others in foster care throughout their life. Childhood abuse influenced decisions over their bodies, including sexual risk-taking behaviors, and contributed to housing instability and entry into the child welfare system.

The girls’ and young women’s reluctance to disclose healthcare needs to parents and providers, especially as it related to reproductive health, related to a perception that caregivers’ reactions would lead to instability in the home. Danielle explained, “I was scared to tell my dad I’m pregnant.” Similarly, Jessica, a 15-year old Latina, was apprehensive to discuss healthcare needs with her caregiver, because she feared getting thrown out of the home. She explained, “I started getting symptoms of STIs and I was just sitting there and I was scared to tell my mom anything because I felt like she’d be like, ‘Get out’.” Jessica ultimately received treatment for chlamydia, but further clarified her hesitation stating, “…and my mom was like, ‘Why didn’t you tell me?’ I was like, ‘Because you scared me’.” In both examples, the young women expressed that they were unable to rely on their caregivers for reproductive healthcare access due to fear of repercussions. These stories convey how fear of instability in the home or being thrown out impacted immediate access to healthcare services and reinforced the feeling a lack of control over their bodies and health.

Moreover, unstable housing and foster care involvement often resulted in risky behaviors, which created additional and emergent healthcare needs. For example, 15-year old Helen shared, “I used to be in social services, and when I was taken away from home, I would get kicked out of group homes. I wouldn’t have nowhere to go.” On one occasion, Helen discussed using methamphetamine while on the streets, and then suffered from injuries related to being hit by a moving vehicle. The lack of housing stability and family support contributed to Helen entering into CSE and engaging in heavy substance use. As depicted in the model, Helen’s story conveys the progression from an unstable childhood to CSE, leading to risky behaviors and environments and immediate healthcare needs.

Entering into state monitored systems of care further reinforced a lack of agency or autonomy over healthcare decisions. Kyanna, a 19-year old African-American young woman, recalled accessing medical treatment while in the child welfare and juvenile justice systems, yet feeling that choice and agency were withheld. In one instance, Kyanna requested, but did not receive, medical attention immediately following a medically induced abortion, leaving her to feel “unimaginable pain.” Additionally, the general lack of structure in group homes appeared to negatively influence the dynamic between staff and residents, including access to healthcare services. Kyanna explained, “… They will take you to the doctor but because girls always complain like, ‘Oh, I am sick, I am sick,’ every other day, literally, they just blow it off.” Furthermore, her history in systems of care (i.e. juvenile justice and child welfare) affected her need to gain agency within seemingly uncontrollable settings. Kyanna communicated, “I learned while I was in there [group home], being in control even when I wasn’t in control.” The young woman explained that youth in juvenile halls and group homes are treated like “cattle” rather than individuals with unique needs. Kyanna concluded, “I can’t be treated like the next person. I have my needs and they [other youth] have their needs.” Kyanna’s story was illustrative of how the ill effects of past experiences and systems involvement drove these girls and young women to seek autonomy over their own bodies.

Lack of Control during CSE

The girls and young women in the study described scenarios that required medical attention, but treatment was often denied due to another person’s influence or control, such as an exploiter—most often men who were identified as a “boyfriend”—or others depended on for financial means. Yet, when services were accessed, they expressed frustration if they perceived the service providers lacked concern or understanding of their needs.

Emergent physical health issues were identified as being directly related to the exploitation. Rachel, a 16-year old African-American young woman, disclosed getting hurt “a lot,” which typically required medical attention. However, she did not access treatment and expressed feeling “scared and worried.” In one instance, she described immense pain where she verbalized wanting and needing to visit the emergency room. Yet, she concluded that the person she was living with believed she did not need medical attention, therefore, she did not receive treatment. As such, some of the girls and young women employed home remedies or simply endured the pain in lieu of treatment. For example, Jessica described her exploiter as “aggressive” which caused her to “get hurt.” Jessica was in need of medical attention because of a vaginal tear that bled for days, but had been restricted from leaving the car by her exploiter. Eventually, the exploiter allowed Jessica to shower, which did not help, and finally purchased Neosporin as a remedy. The denial of medical treatment highlights the lack of control of over their bodies and health, causing them to settle for less effective alternatives that may be within their control.

In instances where the girls and young women sought services, but felt their needs were unmet or minimized by professionals in healthcare settings, they were compelled to forego services. Kyanna, for example, felt law enforcement lacked sensitivity after a physical assault where perpetrators stole her money and belongings. The incident occurred while she returned to CSE. Kyanna explained, “Nobody was helping. I was like the joke or something. I just felt like a joke and people were not taking this serious. I don’t know, it is just awful.” During the emergency room visit, she felt bothered by the long wait time and felt others viewed her as “crazy” because of a visible head wound and blood-soaked clothes. While discussing the healthcare treatment received, Kyanna clearly stated that she did not expect the nurse would have compassion for her situation. Ultimately, the young woman decided to arrange for transportation and leave the facility, rather than receive treatment. The disengagement in care allowed Kyanna to regain a sense of control and agency in a traumatizing situation, and resulted in her not receiving needed treatment for her violence-related injuries.

Violence and Trauma

Survivors of CSE often have deeply embedded histories of sexual and physical violence and trauma, resulting in unresolved medical needs. The girls and young women recalled abusive relationships, violent acts, and neglect of basic health needs that left them traumatized and in need of health treatment. Amee, introduced earlier, and Carmen, a 16-year old Latina, both discussed experiencing violent rapes perpetuated by sex purchasers and, consequently, accessing medical treatment. Yet, they disclosed that other incidents of sexual and physical violence did not result in medical attention. Rather than seek treatment for violence-related injuries, Carmen concluded, “I just cried really. There’s nothing you could really do like in certain situations.” Similarly, Gracie, an 18-year old Latina, explained, “So it was a lot of violence that could have been stopped.” However, due to an active warrant and fear of contact with law enforcement, rather than seek treatment, Gracie concluded, “All I could do was run.” In some instances of violence, the girls and young women exerted agency by accessing medical care, but access depended on the circumstances. The girls or young women expressed a powerlessness to control their healthcare decisions in some violence-related injuries associated with the exploitation, resulting in unmet healthcare needs.

Several other participants alluded to or explicitly described routine physical and emotional violence perpetrated by their exploiters and “boyfriends,” these circumstances rarely afforded any sense of autonomy to seek healthcare. Gracie portrayed ongoing violence that required her to “bandage [herself] up.” When asked if she received any assistance, Gracie simply stated, “On my own.” Anastasha, an 18-year old African-American young woman, earnestly concluded, “Honestly, I can handle pain.” These scenarios illustrate how the girls and young women were forced to circumvent healthcare services and become self-reliant to ensure self-preservation.

Current View of Body, Control, the Self

The girls and young women valued self-reliance and their ability to determine when medical treatment was necessary. They articulated their current views on their bodies, control, and the self as it related to healthcare decisions, and often willingly sought healthcare services that contributed to their overall health and wellness. Additionally, the girls and young women were able to articulate their understanding of health. Danise explained health as, “Taking care of yourself, going to your doctor’s appointments, getting checked up. Just caring about yourself and your body.” Their commitment to their health was evidenced by their ability to find healthcare information, schedule appointments, and self-transport or arrange transportation when treatment was deemed necessary.

The girls and young women impacted by CSE regarded reproductive healthcare of primary importance and reproductive health concerns were often treated with urgency. For example, Carmen described feeling “uncomfortable” and “weird” due to unprotected sex. Viewing the situation as an emergency, for fear of pregnancy and STIs, she refused to wait approximately four days for a doctor’s appointment scheduled by her mother. Taking control of her healthcare decisions, Carmen scheduled an appointment, organized transportation, and accessed treatment at Planned Parenthood within a shorter timeframe. Drea, a 17-year old multi-racial young woman, described accessing contraception through Planned Parenthood without parental consent. She explained, “I think my brother drive me and I went in by myself…. And I went in and got it all by myself and that was the first time I felt grown.” Drea further expressed feeling “mature” without her mother accompanying her. Similarly, in an effort to increase autonomy and control, Danielle affirmed the value of access to reproductive healthcare without parental consent. These sentiments echo the girls and young women’s desire to gain agency over urgent reproductive healthcare decisions without involving caregivers and within a timely manner.

Making decisions about healthcare treatment did not always equate to self-reliance and independence. In one scenario, Anastasha, insisted that her mother be present during an emergency surgery. Fearful of the procedure, Anastasha stated, “Because I told them, I was like, I don’t want to do this unless my mom is here.” The same fierce autonomy that influenced the girls and young women to exercise agency and drive their healthcare, also created a dynamic in which they could choose to increase or decrease their engagement in services.

Discussion

This research contributes to the growing body of literature about survivors’ healthcare decisions and agency. The current state of the literature presents a picture of a high risk, vulnerable group with relatively high rates of healthcare access. Yet, less is known about how youths’ sense of agency in healthcare decision-making may affect their utilization of and engagement in care. From this study, our conceptual model expands the current state of knowledge by highlighting a drive for autonomy over their body and health-related issues, as influenced by their unique backgrounds, including histories of commercial sexual exploitation, the lack of control over their own bodies and decisions, and high needs for healthcare. Further, we underscore that histories of victimization and trauma do not preclude youths’ desire to exercise agency and control. These findings have implications for theory, practice, and future research as outlined below.

Implications for theory.

The concept of fierce autonomy supports and advances the SDM theoretical framework by incorporating the lived experiences and perspectives of youth impacted by CSE. Preliminary studies on SDM in pediatrics have shown increased engagement in care (Bejarando et al., 2015), increased satisfaction among youth, caregivers, and providers, and improved in health outcomes (Brand & Stiggelbout, 2013). By elucidating the overlap between past trauma and a desire for choice in healthcare decisions among youth impacted by CSE, these findings enhance how practitioners and policymakers conceptualize youths’ understanding of their health and wellness and their role in healthcare decision-making. The influence of health-related knowledge may be less impactful than lived experience on how girls and young women affected by CSE understand and make decisions about their health.

Implications for practice.

Our findings can assist providers in understanding how girls and young women impacted by CSE view their health and wellness and, ultimately, strive to maintain some level of control over their own bodies. Fierce autonomy illustrates ways girls and young women with histories of CSE expressed a strong desire to make their own decisions as a way to possess agency. Dissemination of this conceptual model among healthcare professionals, trainees, and other service providers will enhance the understanding of the unique health needs of this population and their desire for services provided with dignity that account for their choice, preferences, and perceptions.

Healthcare professionals can utilize this knowledge by allowing survivors to exercise agency and autonomy as partners in decision-making about health and reproductive care. Further, seeking assent/consent during healthcare treatment can “foster the moral growth and development of autonomy in young patients,” while respecting a youth’s refusal for care presents opportunities to provide appropriate education (Katz & Webb, 2016). Attending to youths’ preferences and individual needs regarding control over their bodies and healthcare decisions can improve the therapeutic relationship by fostering trust and agency (Knight, Kokanović, Ridge, Brophy, Hill, Johnston-Ataata, & Herrman, 2018).

This conceptual model is intended to educate students and professionals and may be useful as part of medical education curricula and healthcare protocols, especially for girls and young women experiencing CSE who present in emergency and reproductive healthcare settings. By reshaping the power structure and offering more control for youth seeking services, this model may serve as an initial and critical shift toward addressing pervasive unmet expectations and healthcare discrimination among diverse groups (Kattari & Hasche, 2016; Meyer, Mocarski, Holt, Hope, King, & Woodruff, 2020). In addition, greater collaboration across sectors and disciplines, as well as partnering with survivors and survivor serving programs can ensure girls and young women impacted by CSE are connected to services that meet their complex needs holistically, especially medical needs.

Implications for future research.

There is emerging, yet limited qualitative health research focused on the perspectives of girls and young women with histories of CSE. Rigorous and empirically-based research is needed to understand the nuances and complexities of those affected by CSE. Future research would benefit from eliciting feedback on what youth seek control over and how they believe this control can be obtained in healthcare settings (Knight et al., 2018). Exploration of how service providers’ biases and judgements affect their ability to provide survivor-centered care, the effect of service providers’ judgement and bias on treatment receipt, and the effect this has on survivors would offer a more holistic understanding of healthcare receipt among this population. We relied on community partners serving this population, so that we could engage survivors and elicit their perceptions on health-related topics. Our findings further the research base on healthcare access, past trauma, agency, and the SDM framework, by including the perspectives of survivors and conveying their perception of when to exercise agency and autonomy in care. By centering their voices, researchers can advance survivors’ narratives and perspectives on desired services. Furthering research to identify other domains in which CSE survivors employ fierce autonomy in decision-making, including behavioral health, contraception use, and substance use, is necessary.

Future research on subpopulations of youth or adults with histories of CSE, such as boys and the LGBTQ community, is needed to advance our understanding of how diverse populations view their health and wellness, engage in healthcare services, and exercise agency and autonomy over their bodies and healthcare.

Researchers can also collaborate with diverse youth to develop intervention strategies and training material for service providers that respond to youths’ perceived health care needs and preferences (MacDonald, Gagnon, Mitchell, Di Meglio, Rennick, & Cox, 2011). Research focusing on the integration of this conceptual model into both medical education and practice protocols could measure the impact on services rendered and utilization of or engagement in care. Lastly, research that depicts barriers and facilitators to upholding fierce autonomy and pertinent associations with SDM can further available knowledge on youths’ agency and autonomy in healthcare treatment.

Limitations

As this sample consisted only of cisgender girls and young women, these findings are not necessarily transferable (Lincoln & Guba, 1985) to survivors who are not cisgender females of this age range. Our sample of girls and young women were also connected to services through their involvement in the child welfare and/or juvenile justice systems; their experiences may or may not differ from girls and young women with histories of CSE not involved in systems of care. Additionally, our eligibility screener may have excluded girls and young women who did not identify with their history of exploitation. Thus, the sample may have only included those comfortable with identifying and discussing their CSE, which may relate to their professed autonomy and agency. Lastly, our age range (15–19) and analyses did not differentiate between the level of autonomy exercised by the younger and older individuals in the sample. Understanding these nuances may further assist in developing age-specific care.

Conclusion

The girls and young women in our study articulated how past experiences of maltreatment, CSE, and a lack of control have influenced their understanding of when engagement in healthcare was necessary. Their stories exemplified a strong desire to exercise a fierce autonomy over their own bodies and healthcare decisions. The concept of fierce autonomy coupled with understanding how trauma is often steeped in shame, isolation, feelings of helplessness, marginalization, and avoidance may further inform approaches to engage individuals impacted by CSE in care. Future research can expand on this conceptual model by focusing on agency and autonomy in healthcare decision-making for subpopulations affected by CSE, measuring the degree to which agency impacts treatment engagement and receipt, and capturing the perspectives of healthcare providers. Service providers can foster the youths’ need to exercise agency over their healthcare decisions, by allowing girls and young women with histories of exploitation to be active drivers and to feel a sense of shared responsibility in decisions affecting their bodies and health.

The “fierce autonomy” conceptual model expands on the SDM framework by conveying how girls and young women impacted by CSE exercised choice and power over healthcare treatment. The narratives and experiences of these youth highlight the need to address service gaps in healthcare settings that perpetuate suboptimal care and lead to negative health outcomes among vulnerable populations (Nicholas et al., 2016). Providing survivors with choices about their healthcare treatment, encouraging them to exercise agency, and integrating their preferences could shift to a paradigm that places their perspective at the center of treatment and values their agency in health-related decisions. As a result, youth impacted by CSE may regain a sense of autonomy and be more actively engaged in care, and ultimately have better health-related outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

We thank the participating girls and young women as well as our partner agencies, including Judge Catherine Pratt, Lori Gray, Lori Harris, Sharonda Bradford, and the Los Angeles County STAR Court, Amber Davies, Sara Elander, and Jasmine Edwards of Saving Innocence, and Michelle Guymon and Violet Dawson of the Los Angeles County Department of Probation Child Trafficking Unit.

Funding: This work was supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) of the National Institutes of Health under the AACAP NIDA K12 program (2016–2020; Grant #K12DA000357) and NIDA K23 (#DA045747-01); Seed Grant from the Children’s Discovery and Innovation Institute (2015–2016); Anthony and Jeanne Pritzker Family Foundation; California Community Foundation; Los Angeles County Department of Probation; Judicial Council of California; and UCLA Clinical and Translational Science Institute (#UL1TR000124).

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The Authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Bantjes J, & Swartz L. (2019). “What can we learn from first-person narratives?” The case of nonfatal suicidal behavior. Qualitative Health Research, 29(10), 1497–1507. DOI: 10.1177/1049732319832869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnert ES, Kelly MA, Ports K, Godoy S, Abrams L, & Bath E. (2019). Understanding commercially sexually exploited adolescent females’ access, utilization, and engagement in healthcare: “Work around what I need.” Women’s Health Issues, 29(4):315–324. DOI: 10.1016/j.whi.2019.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnert E, Kelly M, Godoy S, Abrams L, & Bath E. (2019). Behavioral health treatment “Buy-in” among adolescent females with histories of commercial sexual exploitation. Child Abuse & Neglect, 100(2020), 104042. DOI: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bay-Cheng LY, & Fava NM (2014). What puts “at-risk girls” at risk? Sexual vulnerability and social inequality in the lives of girls in the child welfare system. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 11(2), 116–125. DOI: 10.1007/s13178-013-0142-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bounds D, Julion WA, & Delaney KR (2015). CSE of children and state child welfare systems. Policy, Politics, & Nursing Practice, 1–10. DOI: 10.1177/1527154415583124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand PLP, & Stiggelbout AM (2013). Effective follow-up consultations: the importance of patient-centered communication and shared decision making. Paediatric Respiratory Reviews, 14(4), 224–228. DOI: 10.1016/j.prrv.2013.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. (1997). Shared decision-making in the medical encounter: What does it mean? (or it takes at least 2 to tango). Social Science & Medicine, 44(5), 681–692. DOI: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00221-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. (1995). Grounded theory. In Smith J, Harré R, & Langenhove L. (Eds.), Rethinking methods in psychology (pp. 27–65). London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. (2000). Grounded theory: Objectivist and constructivist methods. In Denzin N. & Lincoln Y. (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (2nd ed., pp. 509–535). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Cook MC, Barnert E, Ijadi-Maghsoodi R, Ports K, & Bath E. (2018). Exploring mental health and substance use treatment needs of commercially sexually exploited youth participating in a specialty juvenile court. Behavioral Medicine, 44(3), 242–249. DOI: 10.1080/08964289.2018.1432552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtois C. (2004). Complex trauma, complex reactions: Assessment and treatment. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 41(4), 412–425. DOI: 10.1037/0033-3204.41.4.412 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne I. (2008). Children’s participation in consultations and decision-making at health service level: A review of the literature. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 45(11), 1682–1689. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2008.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne I, Amory A, Kiernan G. & Gibson F. (2014). Children’s participation in shared decision-making: Children, adolescents, parents and healthcare professionals’ perspectives and experiences. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 18(3), 273–280. DOI: 10.1016/j.ejon.2014.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crickard EL, O’Brien MS, Rapp CA, & Holmes CL (2010). Developing a framework to support shared decision making for youth mental health medication treatment. Community Mental Health Journal, 46, 474–481. DOI: 10.1007/s10597-010-9327-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedina L, Williamson C, & Perdue T. (2016). Risk factors for domestic child sex trafficking in the United States. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 34(13), 2653–2673. DOI: 10.1177/0886260516662306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenbaum J, & Crawford-Jakubiak JE (2015). Child sex trafficking and commercial sexual exploitation: Health care needs of victims. American Academy of Pediatrics, 135(3), 566–574. DOI: 10.1542/peds.2014-4138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenbaum JV, Yun K, & Todres J. (2018). Child trafficking: Issues for policy and practice. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics, 46, 159–163. DOI: 10.1177/2F1073110518766029 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh T, Annandale E, Ashcroft R, Barlow J, Black N, Bleakley A, . . . Ziebland S. (2016). An open letter to the BMJ editors on qualitative research. British Medical Journal, 352, Article i563. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.i563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooks B. (1984). Feminist theory from margin to center. Boston, MA: South End Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ijadi-Maghsoodi R, Bath E, Cook M, Textor L, & Barnert E. (2018). Commercially sexually exploited youths’ health care experiences, barriers, and recommendations: A qualitative analysis. Child Abuse & Neglect, 76(2018), 334–341. DOI: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.11.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine (IOM), & National Resource Council (NRC). (2013). Confronting commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors in the United States. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kattari SK, & Hasche L. (2016). Differences across age groups in transgender and gender non-conforming people’s experiences of health care discrimination, harassment, and victimization. Journal of Aging and Health, 28(2), 285–306. DOI: 10.1177/0898264315590228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz AL, & Webb SA (2016). Informed consent in decision-making in pediatric practice. Pediatrics, 138(2), e20161485. DOI: 10.1542/peds.2016-1485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly MA, Barnert E, Godoy S, Thompson L, Cook M, Ports K, Ijadi-Maghsoodi R, Goboian S, & Bath E. (2017). Understanding the mental health and substance use disorder treatment needs for commercially sexually exploited girls: A partnership with the STAR court. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 56(10),177. DOI: 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.09.083 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Knight F, Kokanović R, Ridge D, Brophy L, Hill N, Johnston-Ataata K, & Herrman H. (2018). Supported decision-making: The expectations held by people with experience of mental illness. Qualitative Health Research, 28(6), 1002–1015. DOI: 10.1177/1049732318762371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lederer LJ, & Wetzel CA (2014). The health consequences of sex trafficking and their implications for identifying victims in healthcare facilities. Annals of Health Law, 23(1), 61–91. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln YS, & Guba EG (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald JM, Gagnon AJ, Mitchell C, Di Meglio G, Rennick JE, & Cox J. (2011). Include them and they will tell you: Learnings from a participatory process with youth. Qualitative Health Research, 21(8), 1127–1135. DOI: 10.1177/1049732311405799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer HM, Mocarski R, Holt NR, Hope DA, King RE, & Woodruff N. (2020). Unmet expectations in health care settings: Experiences of transgender and gender diverse adults in the Central Great Plains. Qualitative Health Research, 30(3), 409–422. DOI: 10.1177/1049732319860265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse J. (1995). The significance of saturation [Editorial]. Qualitative Health Research, 5, 147–149. DOI: 10.1177/104973239500500201 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morse JM (2016). Qualitative health research: Creating a new discipline. New York: Routledge. DOI: 10.4324/9781315421650 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muftic LR, & Finn MA (2013). Health outcomes among women trafficked for sex in the United States: A closer look. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 28(9), 1859–1885. DOI: 10.1177/0886260512469102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. (2012). Comorbidity. Retrieved2 from: https://www.drugabuse.gov/related-topics/comorbidity

- Nicholas DB, Newton AS, Calhoun A, Dong K, deJong-Berg MA, Hamilton F, … Shankar J. (2016). The experiences and perceptions of street-involved youth regarding emergency department services. Qualitative Health Research, 26(6), 851–862. DOI: 10.1177/1049732315577605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell C, Asbill M, Loius E, & Stoklosa H. (2018). Identifying gaps in human trafficking mental health service provision. Journal of Human Trafficking, 4(3), 256–269. [Google Scholar]

- Rafferty Y. (2008). The impact of trafficking on children: Psychological and social policy perspectives. Child Development Perspectives, 2(1), 13–18. DOI: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2008.00035 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ravi A, Pfeiffer MR, Rosner Z, & Shea JA (2017a). Identifying health experiences of domestically sex-trafficked women in the USA: A Qualitative Study in Rikers Island Jail. Journal of Urban Health-Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 94(3), 408–416. DOI: 10.1007/s11524-016-0128-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravi A, Pfeiffer MR, Rosner Z, & Shea JA (2017b). Trafficking and trauma insight and advice for the healthcare system from sex-trafficked women incarcerated on Rikers Island. Medical Care, 55(12). DOI: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahl S. & Knoepke C. (2018) Using shared decision making to empower sexually exploited youth. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 57(11), 809–812. DOI: 10.1016/j.jaac.2018.07.873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapiro B. Johnson L, Postmus JL, Simmel C. (2016). Supporting youth involved in domestic minor sex trafficking: Divergent perspectives on youth agency. Child Abuse & Neglect, 58(2016), 99–110. DOI: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.06.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoklosa H, MacGibbon M, & Stoklosa J. (2017) Human trafficking, mental illness, and addiction: Avoiding diagnostic overshadowing. AMA Journal of Ethics, 19(1): 23–34. DOI: 10.1001/journalofethics.2017.19.1.ecas3-1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trafficking Victims Protection Act of 2000, H.R. 3224, United States Congress, P-L 106–386 Division A 103(8)2000. Retrieved from: https://www.state.gov/j/tip/laws/61124.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Varma S, Gillespie S, McCracken C, & Greenbaum J. (2015). Characteristics of child CSE and sex trafficking victims presenting for medical care in the United States. Child Abuse & Neglect 44(0), 98–2015. DOI: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WestCoast Children’s Clinic. (2012). Research to action: Sexually exploited minors (SEM) needs and strengths. Oakland, CA: WestCoast Children’s Clinic. Retrieved from: http://www.westcoastcc.org/WCC_SEM_Needs-and-Sts_FINAL.pdf [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.