Summary

Viral variants of concern may emerge with dangerous resistance to the immunity generated by the current vaccines to prevent coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19). Moreover, if some variants of concern have increased transmissibility or virulence, the importance of efficient public health measures and vaccination programs will increase. The global response must be both timely and science based.

In addition to continuing to track the emergence of new variants of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), there are four major priorities for the global response to variants of concern (Table 1). These priorities, which involve scientific approaches for evaluating existing vaccines and developing modified and new vaccines, are to determine whether existing vaccines are losing efficacy against variants, to decide whether modified or new vaccines are warranted to restore efficacy against variants, to reduce the likelihood that variants of concern will emerge, and to coordinate international research and the response to new variants, both in general and in relation to vaccines, through the World Health Organization (WHO).

Table 1. Vaccine-Related Priorities to Control Viral Variants.*.

| Evaluate existing vaccines for efficacy against variants |

| Randomize vaccine schedules (e.g., agents and timing) during deployment and study postexposure prophylaxis |

| Perform observational studies to estimate variant-specific vaccine effectiveness |

| Expand worldwide capacity for sequencing of virus isolates |

| Obtain sequences of clinical isolates from postlicensure studies, clinical trials, and vaccinees with serious breakthrough infections |

| If current vaccines are inadequate, assess the effectiveness of new vaccines or modified vaccines against variants |

| Evaluate new vaccines, ideally in randomized, placebo-controlled trials with clinical end points |

| Develop and evaluate modified vaccines to achieve adequate efficacy against variants of concern |

| Reduce the risk that additional variants of concern will emerge |

| Promote public health measures (e.g., masking, social distancing, and vaccination) to reduce viral transmission |

| Avoid the use of treatments with uncertain benefit that could drive the evolution of variants |

| Consider targeted vaccination strategies to reduce community transmission |

| Coordinate the worldwide response |

| Identify and characterize viral variants of concern |

| Select antigens for modified or new vaccines |

| Share research results, including methods to link genetic sequence data with the antigenic characteristics of circulating SARS-CoV-2 |

| Decide whether the variant data warrant modification of existing vaccines |

| Promote convergence of regulatory assessments |

| Establish a global data repository |

An existing vaccine is one that has been shown to be effective in clinical trials, a modified vaccine one in which a new antigen is delivered through an existing vaccine, and a new vaccine a completely new vaccine. SARS-CoV-2 denotes severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

Efforts to track viral mutations and variants are ongoing. The aim is to detect new changes quickly and to assess their possible effects. Many research groups are sequencing virus isolates and sharing these sequences on public databases such as GISAID (Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data).1 This collaboration helps scientists track the ways in which the virus is evolving. In order to help monitor and respond to the evolving pandemic, it is important that all countries increase the collection of virus isolates for sequencing and sharing. A SARS-CoV-2 risk-monitoring and evaluation framework is being developed and continually improved by the WHO to identify and assess variants of concern. This framework, which involves enhanced surveillance, research on variants of interest and variants of concern, and evaluation of the effect of variants on diagnostic tests, therapeutic agents, and vaccines, will assist in global decision making regarding changes in vaccines that may be necessary.

Variants of concern with increased transmissibility are contributing to the reversal of the decreases in Covid-19 case counts that occurred in many countries earlier this year.2 The B.1.1.7 (or alpha) variant of concern increases viral transmissibility3 and is emerging as an increasingly common variant. The P.1 (or gamma) variant may cause severe disease even in persons who have been previously infected, although definitive information is lacking.4 The B.1.351 (or beta) variant is less easily neutralized by convalescent plasma obtained from patients infected with previous variants and by serum obtained from vaccinees than the prototype virus on which vaccine antigens are based,5 and preliminary evidence (based on data from post hoc subgroups in placebo-controlled vaccine trials) suggests reduced efficacy of some vaccines against mild or moderate disease caused by this variant.6-8 Additional variants that are responsible for many deaths, such as B.1.617.2 (or delta),9 continue to emerge. So far, there is no good evidence that currently identified variants of concern evade the most important vaccine effect — that of prevention of severe disease. Table 2 describes key properties of and mutations in five selected variants. The fact that a few key amino acids in the spike protein have changed independently in variants identified in various parts of the world indicates that these are convergent changes and suggests that vaccines that incorporate these selected residues could cover several variants.

Table 2. Key Spike Protein Mutations in Five SARS-CoV-2 Variants.

| Variant | Phenotypic Change | Amino Acid Position in Prototype Virus and Proposed Effect of Changing It* | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Δ69–70 Increase transmission |

K417 Decrease neutralization |

L452 Decrease neutralization |

E484 Decrease neutralization |

N501 Increase transmission |

D614 Increase transmission |

P681 Increase transmission |

||

| B.1.1.7 (or alpha) | Increase transmission | 69–70 deleted | K (later change) | Y | G | H | ||

| B.1.351 (or beta) | Increase transmission and virulence | N | K | Y | G | |||

| B.1.1.28.1 (or gamma or P.1) | Increase transmission and virulence, decrease neutralization | N/T | K | Y | G | |||

| B.1.617.2 (or delta) | Increase transmission, decrease neutralization | R | R | R | ||||

| B.1.617.1 (or kappa) | Increase transmission, decrease virulence | R | Q | G | R | |||

Single letter codes of amino acid changes at specified positions for the listed variants are shown.

Evaluating Existing Vaccines for Efficacy against Variants

Although animal models and in vitro studies can provide important information, clinical data will continue to be needed to determine whether existing vaccines are losing efficacy against variants. While existing vaccines are being deployed, clinical data can be sought not only from carefully planned observational studies, but also from randomized trials of vaccines versus placebo, of one vaccine versus another, or of different vaccination regimens (e.g., different doses, numbers of doses, and intervals between doses).

In areas where the vaccine supply or delivery capacity is limited, instead of letting operational decisions determine the order in which people are vaccinated, making first vaccine doses available to some of the target population on a randomized basis could provide useful information about efficacy against major variants. This is especially true if the numbers of participants who undergo randomization are large enough to allow assessment of “hard” end points such as hospitalization or severe disease.

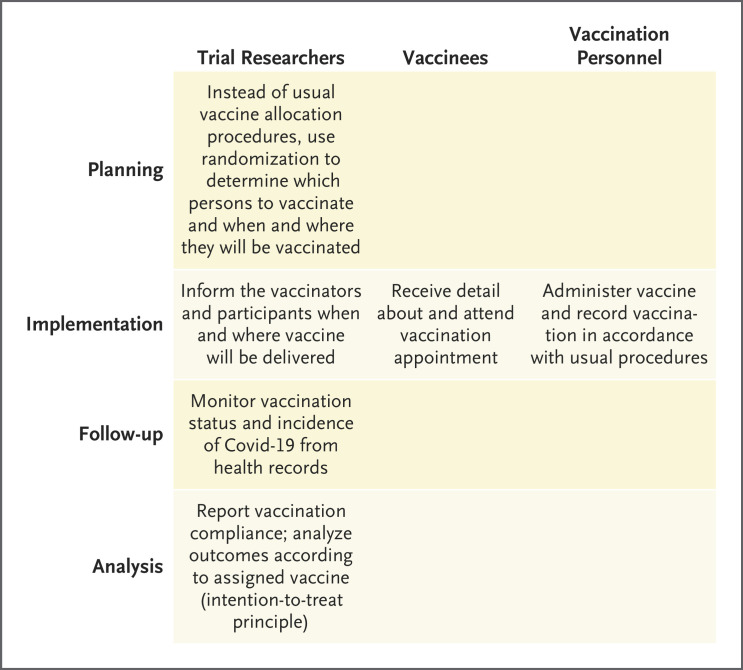

If large-scale randomization were used during vaccine deployment to compare the effects of early second doses with those of delayed second doses, any differences in efficacy could be reliably assessed not only overall but perhaps with respect to certain common variants. In some populations, random assignment of the vaccination date or location might be built into public health programs, and persons who become eligible for vaccination (according to vaccine priority groupings) could be randomly assigned to receive appointments to be vaccinated with a longer or a shorter gap between doses or to receive one vaccine or another. This strategy might allow many hundreds of thousands of persons to undergo randomization with little cost to the vaccination program and with little or no disturbance of the existing vaccination capacity (Figure 1). At the opposite extreme of trial size, if any vaccines were known to have the potential to prevent Covid-19 even when administered after an exposure to SARS-CoV-2, relatively small, randomized studies of postexposure prophylaxis could provide important insights about vaccine efficacy (or relative efficacy) against different strains.

Figure 1. Roles of Researchers, Vaccinees, and Vaccinators in Simplified Randomized Trials Conducted during Vaccine Deployment.

In trials to assess vaccine efficacy, work performed by trial researchers is considerably more simplified than work in a standard trial, with no extra effort required from vaccinees or vaccination personnel. Covid-19 denotes coronavirus disease 2019.

Nonrandomized observational studies that attempt to estimate vaccine effectiveness are all prone to some bias. Nevertheless, in areas where several variants are cocirculating and some but not all of the population has been vaccinated, carefully designed observational studies of the distribution of viral genotypes among cases in vaccinated and unvaccinated persons could yield fairly reliable estimates of relative vaccine efficacy against various variants. Such studies should account for potential confounding if the level of vaccination is correlated with the relative prevalence of variants across sites . Observational studies could also detect loss of protection against variants of concern in previously infected persons.

Observational studies lack precision when either vaccine uptake or variant prevalence is too low or too high for statistical stability, but they could provide insights if cases and controls are adequately matched for potential confounders (e.g., in a “test-negative design”10). There are ways to at least limit confounding for such studies in general11 and for test-negative studies in particular.12,13

Creative methodologic approaches are still needed to assess any influences of variants of concern on vaccine efficacy and durability. In studies of vaccine efficacy and effectiveness against variants of concern, near-complete sequencing of isolates from selected sentinel sites can reduce biases in the selection of samples for sequencing. Sequencing capacity is lacking in many parts of the world and should be increased. Samples obtained from unselected vaccine recipients with breakthrough infection and from matched unvaccinated controls could be used to assess the influence of particular genomic or antigenic features of interest on vaccine efficacy. With the use of such approaches (i.e., “sieve analyses”14) in trials or in studies conducted after vaccine deployment, important insights could be gleaned about the relevance of particular viral features, and these insights may lead to improved strain selection in the formulation of modified vaccines.

How reliably any immune biomarker can serve as a “correlate of protection” is not yet known. The effects of vaccination on such biomarkers (as surrogate end points) — if those biomarkers prove to be reliably predictive of the effects of vaccine on the incidence or outcome of breakthrough infections — could provide support for regulatory action regarding new candidate vaccines. However, caveats include the potential dependence of immune correlates of protection on vaccine-specific factors, viral strain, and the choice of Covid-19 study end points (i.e., any infection vs. symptomatic infection vs. severe disease).

Evaluating New or Modified Vaccines against Variants

Although there will be reluctance to deploy vaccines that are based on new sequences before there is clear evidence that the original vaccines are failing, there will also be reluctance to allow prolonged circulation of vaccine-resistant variants while new vaccines or modified vaccines are being developed, if this can be avoided. Now is the time to plan for the development of modified vaccines that could protect against vaccine-resistant variants, because such variants may well emerge. Planning should include the effect of vaccine modification on timelines for vaccine supply and rollout.

Studies of modified vaccines (i.e., vaccines in which a new antigen is delivered through a vaccine that has already been shown to be effective against previously circulating viral variants) should address the ability of these vaccines to elicit responses in persons who have not previously had an immunologic response against SARS-CoV-2 and in previously vaccinated persons. Changes in the in vitro neutralization of circulating strains by vaccine-induced antibodies may not imply waning effectiveness. Although neutralizing responses may not be reliably predictive of vaccine efficacy, striking differences may well provide sufficient support for regulatory decisions. For example, the magnitude of the immune response against one or more variants of concern after a person has received a modified vaccine could be compared with that against the prototype virus after a person has received the original vaccine that is known to be effective. Assessment of neutralizing responses against several variants of concern and against the prototype virus may help to determine whether more than one vaccine (or, ultimately, a polyvalent vaccine) is needed.

There has been consensus in recent regulatory discussions15 and in WHO guidance that conventional, large, clinical end-point trials are probably not necessary in order to introduce modified vaccines against variants of concern. Because differences among assays of immune responses may complicate direct comparisons, the Food and Drug Administration (but not the European Medicines Agency) has proposed that animal models16 could be used to provide further support for the effectiveness of modified vaccines against variants of concern.

Even with the deployment of some safe and effective vaccines, more will be needed to address the international pandemic. New vaccines may be more effective than previous vaccines against emerging viral variants, and they may be administered in a single dose, be noninjectable, avoid cold-chain constraints, or have improved manufacturing scalability. The design of modified vaccines or of completely new vaccines should leverage international recommendations regarding antigenic composition.

Trials of new vaccines can still yield reliable and interpretable results in an efficient manner by using randomization, by evaluating effects not only on immunologic but also on clinical end points, and by using placebo controls when ethically appropriate,17,18 perhaps in communities where vaccine supply is very limited or in subpopulations (e.g., young adults) in which even if infection occurs, the probability of progression to serious disease is very low.19,20 Randomized trials require additional planning, but when practicable they prevent unidentified trial design–related differences from confounding the study results.21 Viral genotyping in persons with breakthrough infection (during or after trials) can support multiple analyses, including assessment of the influence of viral variants on vaccine efficacy. In randomized, controlled studies, such genotyping also yields unbiased information about variant-specific efficacy. Countries that participate in such trials may assess vaccine efficacy against locally prevalent viral strains and should receive priority access to trial vaccines if they have been shown to have an acceptable safety profile and to be efficacious (Table 3). In areas where placebo-controlled trials of new vaccines are not appropriate, the use of an active comparator could still yield important results.22 However, the validity of a noninferiority trial in which an active comparator vaccine is used as the control is dependent on the ability of the previous studies of the active comparator to provide investigators with reliable insights about the efficacy of the active comparator vaccine against viral variants that are currently present in communities engaged in the trial.

Table 3. Randomized Trials to Determine the Efficacy of New Vaccines.

| Trial Design | Trial Conduct | Ethical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Randomization of participants to receive one or more new vaccines or a common control vaccine | Rapid enrollment of trial participants with high adherence and retention | Trial participants gain either immediate or delayed access to experimental vaccines |

| Use of placebos, if appropriate, or use of active control vaccines with established efficacy19 | Data monitoring committee safeguards participants and enhances trial integrity | Participating communities or countries have priority access to vaccine if it has a good safety profile and is effective |

| Monitoring of symptomatic disease, severe disease, durability of effect, influence of variants on efficacy (“sieve analysis”), and immunologic responses as potential correlates of protection* | Samples are obtained at diagnosis visits from trial participants with infection, and sequencing of samples obtained from recipients of control vaccines and new vaccines is used to assess the influence of viral variants on vaccine efficacy | Vaccine efficacy is assessed in the context of whatever viral strains are circulating in the communities of trial participants; results with global relevance are provided |

Sieve analysis is a statistical method that is used to infer the way in which vaccine efficacy varies with viral variants or genotypes.14

Once modified vaccines or completely new vaccines that address new variants have been introduced, the cycle can begin anew with monitoring for even newer variants that might necessitate further changes in the vaccine antigen sequence. Development and deployment strategies should account for the possibility that multiple variants may circulate in the same area. Studies in which one vaccine is boosted with a later dose of another would also be valuable.

Reducing the Risk That Variants of Concern Will Emerge

Variants of concern have been evolving since the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic, with selective advantage generally favoring more transmissible variants. Variants of concern with resistance against natural or vaccine-induced immunity would probably supplant previously circulating strains only if this immune evasion capability resulted in increased fitness, including transmissibility. Given the emergence of immunity-evading variants even before vaccines were broadly deployed, it is hard to implicate vaccines or vaccine deployment strategies as the major drivers of immune evasion.

However, prolonged viral replication in the presence of partial immunity in immunocompromised persons or circumstances in which rapid transmission of high titers of virus occurs (e.g., crowded living conditions23) could have contributed to the development of variants that can at least partially escape human immune responses. The use of antibody-based treatments (e.g., monoclonal antibodies or convalescent plasma) in circumstances in which they are of limited or undemonstrated efficacy may further contribute to the evolution of variants of concern that could evade not only these but also other antibody responses.24 Partially effective interventions may therefore encourage viral evolution. In addition, the larger the number of infected persons, the greater the chance that new variants of concern will arise. Hence, effective public health strategies such as social distancing, the use of masks, and the targeted use of effective vaccines that reduce both infection and transmission can help to limit viral evolution. Limiting transmission in the general population is extremely important for slowing the emergence of additional variants of concern.

Globally, vaccines are being rolled out slowly, partly because of limitations on production capacity and “vaccine nationalism,”25 and in many countries supplies will probably be limited even in late 2021. Currently, the main strategy is to protect critical services, persons in whom severe disease is most likely to develop (e.g., older adults), and persons who are likely to transmit the virus to vulnerable populations (e.g., health care, frontline, and essential workers), and to contain the spread of the virus in the general population. The balance between using vaccines to protect persons from disease and using vaccines to target prevention of spread involves a strategic decision that should be informed by reliable epidemiologic information.

In some epidemics, complete disease elimination has been achieved efficiently by using an epidemiologic understanding of transmission to target the deployment of vaccines (e.g., vaccinating “rings” of contacts and contacts of contacts around cases of smallpox or Ebola26-28). Together with other public health measures, targeting vaccination to persons in certain areas or to demographic groups with a high incidence of infection rather than focusing only on persons at high risk for serious disease could slow transmission and reduce the risk of development of additional variants of concern, although no strategy can work if adequate vaccine supplies are unavailable. Targeted approaches are now being investigated. For example, in certain areas, the deployment of some vaccines in a modified ring vaccination strategy has been suggested.29 Studies of the effectiveness of such targeted strategies could be of global relevance, especially if groups or areas with consistently high and low rates of transmission can be identified.

Coordinating the Worldwide Response

New variants of concern may emerge in any corner of the world and spread quickly, and convergent changes have been noted in variants of concern identified in various parts of the world. The modification of sequences targeted by a vaccine to meet the needs of one country could have repercussions elsewhere. Therefore, vaccine development, vaccine modification, and vaccine deployment should be viewed as international enterprises, with international coordination by the WHO helping benefits to accrue throughout the world.

Coordination is essential in assessing the need for new or modified vaccines, in evaluating them, and in facilitating scientific understanding of the risk posed by novel variants and of the relationships between genetic variation and antigenic escape. Open and frequent scientific discussion is necessary to identify which variants of concern require attention. Criteria are needed to assess the appropriateness of given vaccines and the likely effect of emerging variants on vaccines, as well as to support recommendations on the development and evaluation of modified vaccines and new vaccines and the timing of their deployment. This process can build on the global framework used periodically by the WHO to coordinate the selection of antigens in influenza vaccines (Figure 2).

Figure 2. A Framework for Evaluating Vaccines against Variants of Concern.

After variants of concern are designated, the efficacy of existing vaccines is evaluated with the use of in vitro data, animal models, randomized evidence, observational studies, and surveillance.

Decision making about which antigens should be included in vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 will need to involve epidemiologic data, data from evolutionary biology, and clinical, animal, and in vitro data that are pertinent to immune responses and to continued vaccine efficacy in the face of changing viral sequences and the possible waning of vaccine-induced immunity. Meeting these challenges efficiently will require enhanced surveillance with continued sharing of data (including viral sequences and corresponding antigens that are linked to clinical and epidemiologic information) and samples (including new viral variant isolates and serum samples obtained from vaccinated persons). It will also require the use of standardized reference reagents and models to evaluate viruses and modified vaccines. With collaborative, open discussion of results, this data sharing will help foster consistent and thoughtful public communications about new variants and help maintain appropriate confidence in vaccines and in the processes used to develop, test, and deploy them.

Although Covid-19 continues to present public health challenges, including the emergence of new variants, great progress has been made in understanding this disease and how to protect against it. Even though existing vaccines are helping to bring the pandemic under control in some locations, it is also necessary to plan for unsatisfactory outcomes. As this planning continues, international coordination by the WHO of research efforts and sharing of data and specimens should be a priority. Maintaining the efficacy of vaccines against emerging variants and achieving equitable access to effective vaccines in all countries will be of utmost importance as a sustainable response is built.

Disclosure Forms

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and not necessarily those of their organizations or of the World Health Organization.

This article was published on June 23, 2021, at NEJM.org.

Footnotes

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

References

- 1.Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data (GISAID). hCoV-19 tracking of variants. 2021. (https://www.gisaid.org/).

- 2.World Health Organization. WHO coronavirus (COVID-19) dashboard. 2021. (https://covid19.who.int/).

- 3.Volz E, Mishra S, Chand M, et al. Assessing transmissibility of SARS-CoV-2 lineage B.1.1.7 in England. Nature 2021;593:266-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Faria NR, Mellan TA, Whittaker C, et al. Genomics and epidemiology of the P.1 SARS-CoV-2 lineage in Manaus, Brazil. Science 2021. April 14 (Epub ahead of print). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang P, Nair MS, Liu L, et al. Antibody resistance of SARS-CoV-2 variants B.1.351 and B.1.1.7. Nature 2021;593:130-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Madhi SA, Baillie V, Cutland Cl, et al. Safety and efficacy of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 (AZD1222) Covid-19 vaccine against the B.1.351 variant in South Africa. February 12, 2021. (https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.02.10.21251247v1). preprint.

- 7.Food and Drug Administration. FDA briefing document: Janssen Ad26.COV2.S vaccine for the prevention of COVID-19 (table 22). Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee Meeting, February 26, 2021 (https://www.fda.gov/media/146217/download).

- 8.Novavax COVID-19 vaccine demonstrates 89.3% efficacy in UK phase 3 trial. Press release of Novavax, Gaithersburg, MD, January 28, 2021. (https://ir.novavax.com/news-releases/news-release-details/novavax-covid-19-vaccine-demonstrates-893-efficacy-uk-phase-3#:~:text=In%20the%20South%20Africa%20Phase,population%20that%20was%20HIV%2Dnegative).

- 9.Dhar MS, Marwal R, Radhakrishnan VS, et al. Genomic characterization and epidemiology of an emerging SARS-CoV-2 variant in Delhi, India. June 3, 2021. (https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.06.02.21258076v1). preprint. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.De Serres G, Skowronski DM, Wu XW, Ambrose CS. The test-negative design: validity, accuracy and precision of vaccine efficacy estimates compared to the gold standard of randomised placebo-controlled clinical trials. Euro Surveill 2013;18:20585-20585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ 2016;355:i4919-i4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lewnard JA, Tedijanto C, Cowling BJ, Lipsitch M. Measurement of vaccine direct effects under the test-negative design. Am J Epidemiol 2018;187:2686-2697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dean NE, Halloran ME, Longini IM Jr. Temporal confounding in the test-negative design. Am J Epidemiol 2020;189:1402-1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gilbert P, Self S, Rao M, Naficy A, Clemens J. Sieve analysis: methods for assessing from vaccine trial data how vaccine efficacy varies with genotypic and phenotypic pathogen variation. J Clin Epidemiol 2001;54:68-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.International Coalition of Medicines Regulatory Authorities. ICMRA COVID-19 Virus Variants Workshop, February 10, 2021. (http://icmra.info/drupal/en/covid-19/10february2021).

- 16.Muñoz-Fontela C, Dowling WE, Funnell SGP, et al. Animal models for COVID-19. Nature 2020;586:509-515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singh JA, Kochhar S, Wolff J, WHO ACT-Accelerator Ethics & Governance Working Group. Placebo use and unblinding in COVID-19 vaccine trials: recommendations of a WHO Expert Working Group. Nat Med 2021;27:569-570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization. Emergency use designation of COVID-19 candidate vaccines: ethical considerations for current and future COVID-19 placebo-controlled vaccine trials and trial unblinding. Policy brief. December 18, 2020. (https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/337940/WHO-2019-nCoV-Policy_Brief-EUD_placebo-controlled_vaccine_trials-2020.1-eng.pdf).

- 19.Krause P, Fleming TR, Longini I, Henao-Restrepo AM, Peto R. COVID-19 vaccine trials should seek worthwhile efficacy. Lancet 2020;396:741-743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.WHO Ad Hoc Expert Group on the Next Steps for Covid-19 Vaccine Evaluation. Placebo-controlled trials of Covid-19 vaccines — why we still need them. N Engl J Med 2021;384(2):e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Collins R, Bowman L, Landray M, Peto R. The magic of randomization versus the myth of real-world evidence. N Engl J Med 2020;382:674-678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fleming TR, Krause PR, Nason M, Longini IM, Henao-Restrepo A-MM. COVID-19 vaccine trials: the use of active controls and non-inferiority studies. Clin Trials 2021. February 3 (Epub ahead of print). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oxford JS, Sefton A, Jackson R, Innes W, Daniels RS, Johnson NPAS. World War I may have allowed the emergence of “Spanish” influenza. Lancet Infect Dis 2002;2:111-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kemp SA, Collier DA, Datir RP, et al. SARS-CoV-2 evolution during treatment of chronic infection. Nature 2021;592:277-282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eaton L. Covid-19: WHO warns against “vaccine nationalism” or face further virus mutations. BMJ 2021;372:n292-n292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Foege WH, Millar JD, Lane JM. Selective epidemiologic control in smallpox eradication. Am J Epidemiol 1971;94:311-315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Henao-Restrepo AM, Longini IM, Egger M, et al. Efficacy and effectiveness of an rVSV-vectored vaccine expressing Ebola surface glycoprotein: interim results from the Guinea ring vaccination cluster-randomised trial. Lancet 2015;386:857-866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fenner F, Henderson DA, Arita I, Jezek Z, Ladnyi ID. Smallpox and its eradication. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1988. (http://whqlibdoc.who.int/smallpox/9241561106.pdf). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Macintyre CR, Costantino V, Trent M. Modelling of COVID-19 vaccination strategies and herd immunity, in scenarios of limited and full vaccine supply in NSW, Australia. Vaccine 2021. April 24 ( 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.04.042) (Epub ahead of print). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.