Abstract

To determine whether a community-based physical rehabilitation program could improve the prognosis of patients who had undergone percutaneous coronary intervention after acute myocardial infarction, we randomly divided 164 consecutive patients into 2 groups of 82 patients. Patients in the rehabilitation group underwent 3 months of supervised exercise training, then 9 months of community-based, self-managed exercise; patients in the control group received conventional treatment. The primary endpoint was major adverse cardiac events (MACE) during the follow-up period (25 ± 15.4 mo); secondary endpoints included left ventricular ejection fraction, 6-minute walk distance, and laboratory values at 12-month follow-up.

During the study period, the incidence of MACE was significantly lower in the rehabilitation group (13.4% vs 24.4%; P <0.01). Cox proportional hazards regression analysis indicated a significantly lower risk of MACE in the rehabilitation group (hazard ratio=0.56; 95% CI, 0.37–0.82; P=0.01). At 12 months, left ventricular ejection fraction and 6-minute walk distance in the rehabilitation group were significantly greater than those in the control group (both P <0.01), and laboratory values also improved.

These findings suggest that community-based physical rehabilitation significantly reduced MACE risk and improved cardiac function and physical stamina in patients who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention after acute myocardial infarction.

Keywords: Cardiac rehabilitation/methods; combined modality therapy/methods; exercise therapy/methods; health promotion; myocardial infarction/rehabilitation; patient compliance; percutaneous coronary intervention/rehabilitation; prospective studies; quality indicators, health care; treatment outcome

Because of lifestyle changes, more Chinese people are having acute myocardial infarction (AMI). Despite initial life-saving treatment, the morbidity associated with AMI is a major reason for emergency medical care, physical disability, and death. Approximately 2.5 million Chinese patients have had an AMI; the incidence is predicted to reach 23 million by 2030.1,2 Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), the chief treatment for AMI,3 has reduced morbidity and mortality; however, enabling patients to recover fully remains a public health issue.

Physical rehabilitation after PCI has helped to lower all-cause and cardiac mortality rates. Exercise has also been credited for alleviating patients' symptoms, improving functional capacity and perceived quality of life, and supporting early return to work and self-management skills.4,5 However, most patients undergo rehabilitation while they are in the hospital, and only for short periods. Community-based protocols may help patients maintain the effects of in-hospital exercise.

Currently, less than 25% of outpatients participate in community-based physical rehabilitation programs; 30% to 40% stop after 6 months, and up to 50% stop after 12 months.6,7 To overcome this challenge, we developed a community-based physical rehabilitation program and evaluated its effects on the health of patients with AMI after successful revascularization by means of PCI.

Patients and Methods

From April 2013 through March 2014, 325 consecutive patients with AMI (age range, 18–79 yr) who underwent PCI at our hospital were evaluated for inclusion in this study. We excluded 73 who had a history of myocardial revascularization, severe aortic stenosis, heart failure, resting systolic blood pressure >180 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure >110 mmHg, acute systemic illness, acute metabolic disorders, uncontrolled malignant arrhythmia, or skeletal vascular disease; 88 other patients declined to participate. This study conformed with our hospital's ethical standards and with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Using computer-generated randomization schedules, we divided the remaining 164 patients into a physical rehabilitation group and a control group of 82 patients each. The groups had similar baseline characteristics (Table I).

TABLE I.

Baseline Characteristics

| Variable | Rehabilitation Group (n=82) | Control Group (n=82) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 60.2 ± 9.2 | 58.7 ± 8.8 | 0.86 |

| Male | 61 (74.4) | 64 (78) | 0.71 |

| Smoker | 45 (54.9) | 43 (52.4) | 0.88 |

| Body mass index | 25.4 ± 2.8 | 25.2 ± 2.6 | 0.68 |

| LVEF (%) | 48.1 ± 9.5 | 47.2 ± 10.3 | 0.72 |

| 6-minute walk distance (m) | 232.7 ± 71.8 | 240.1 ± 74.2 | 0.26 |

| STEMI | 51 (62.2) | 54 (65.9) | 0.75 |

| Multivessel disease | 32 (39) | 29 (35.4) | 0.63 |

| PCI revascularization | — | — | — |

| Complete | 23 (71.9) | 21 (72.4) | 0.72 |

| Incomplete | 9 (28.1) | 8 (27.6) | 0.8 |

| Comorbidities | — | — | — |

| Hypertension | 55 (67.1) | 57 (69.5) | 0.87 |

| Dyslipidemia | 23 (28) | 27 (32.9) | 0.61 |

| Diabetes | 22 (26.8) | 20 (24.4) | 0.86 |

| Obesity | 10 (12.2) | 8 (8.8) | 0.8 |

| Laboratory values (mg/dL) | — | — | — |

| Total cholesterol | 177.9 ± 34.8 | 174 ± 38.7 | 0.75 |

| Triglycerides | 159.4 ± 106.3 | 141.7 ± 97.4 | 0.87 |

| LDL cholesterol | 85.1 ± 42.5 | 81.2 ± 38.7 | 0.73 |

| Glucose | 122.4 ± 32.4 | 117 ± 27 | 0.88 |

LDL = low-density-lipoprotein; LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction; PCI = percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI = ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction

Data are presented as mean ± SD or as number and percentage. P <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Patients in the control group were prescribed conventional medical therapy, including oral aspirin, nitrates, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and statins, and their health education included dietary counseling, smoking cessation counseling (when needed), and stress management.

After being discharged from the hospital, patients in the physical rehabilitation group received conventional medical therapy and underwent supervised exercise training for 3 months; they then participated in a community-based and self-managed exercise program for 9 months, aided by counseling. Exercise training included a 10-minute warm-up, 30 to 40 minutes of aerobic exercise (walking or bicycling), and a 10-minute cool-down period. During the supervised training phase, experienced general practitioners explained how to exercise properly. The target was a heart rate slower than 130 beats/min or a resting heart rate + 20 beats/min. During the 9-month self-managed period, each patient was to keep exercising as instructed, 3 to 5 times weekly, at home or at specialized rehabilitation facilities in the community. The target heart rate was 65% to 80% of maximum. Patients who had uncomfortable symptoms were to stop exercising until their next counseling meeting, when their program would be evaluated and potentially modified or discontinued. Each patient's self-managed program was remotely monitored through individual weekly WeChat messages and telephone calls. Virtual meetings, including experienced general practitioners and all patients in the physical rehabilitation group, were held every 2 weeks to answer questions. The patients recorded their activity on log sheets, and their progress was monitored for at least 12 months through December 2016.

Study Endpoints

The study's primary endpoint was the occurrence of major adverse cardiac events (MACE), encompassing revascularization, myocardial infarction, and cardiac death, during a planned follow-up period through December 2016. Secondary endpoints included left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), 6-minute walk distance, and laboratory values at 12-month follow-up.

Statistical Analysis

Normally distributed continuous variables, compared by using t tests, were expressed as mean ± SD. Categorical variables, compared by using the χ2 test, were expressed as number and percentage. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis and Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to estimate hazard ratios (HR) for MACE after adjusting for other covariates. All tests were 2-sided, and P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed with use of SPSS version 20.0 for Windows (SPSS, an IBM company). We estimated that a sample size of 82 patients per group would provide >80% power with a type I error rate (2-sided) of 5% to detect a between-group difference of 10% in MACE.

Results

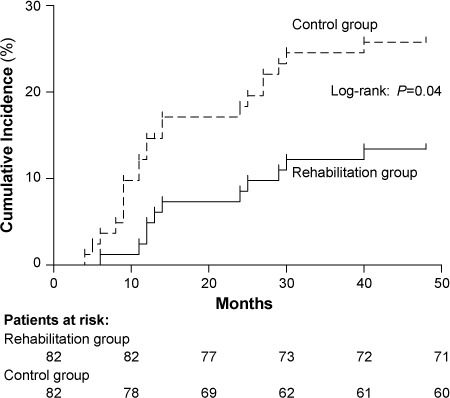

During the mean follow-up time of 25 ± 15.4 months, 11 patients (13.4%) in the rehabilitation group and 20 (24.4%) in the control group had a MACE. The log-rank analysis showed that MACE risk was significantly lower in the rehabilitation group than in the control group (HR=0.48; 95% CI, 0.24–0.97; P=0.04) (Fig. 1). After adjustment for potential confounders, Cox proportional hazards regression analysis indicated that MACE risk was significantly lower for patients in the rehabilitation group (HR=0.56; 95% CI, 0.37–0.82; P=0.01).

Fig. 1.

Kaplan-Meier curves show major adverse cardiac event rates for patients in the rehabilitation and control groups. P <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

After 12 months, LVEF and 6-minute walk distance significantly increased in the rehabilitation group in comparison with the control group (Table II). Laboratory values and body mass index were also lower in the rehabilitation group. The number of smokers decreased in both groups, but there was no significant difference between groups.

TABLE II.

Secondary Outcomes After 12 Months

| Variable | Rehabilitation Group (n=82) | Control Group (n=82) | PValue |

|---|---|---|---|

| Smoking | 16 (19.5) | 22 (26.8) | 0.35 |

| BMI | 22.3 ± 2.3 | 24.5 ± 2.5 | <0.01 |

| LVEF (%) | 61.2 ± 8.5 | 48.5 ± 9.7 | <0.001 |

| 6-minute walk distance (m) | 400.7 ± 73.7 | 289.2 ± 76.3 | <0.01 |

| Laboratory values (mg/dL) | |||

| Total cholesterol | 139.2 ± 30.9 | 170.1 ± 34.8 | <0.01 |

| Triglycerides | 97.4 ± 62 | 132.8 ± 70.8 | <0.01 |

| LDL cholesterol | 69.6 ± 38.7 | 85.1 ± 42.5 | 0.016 |

| Glucose | 91.8 ± 27 | 108 ± 28.8 | <0.01 |

BMI = body mass index; LDL = low-density-lipoprotein; LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction

Data are presented as mean ± SD or as number and percentage. P <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Discussion

During the last few decades, progress in the field of cardiovascular medicine has led to the capability of rehabilitating patients after AMI, and interventional therapy has led to success. As the results of this study suggest, our community-based physical rehabilitation program significantly reduced MACE risk, improved LVEF and 6-minute walk distance, and improved relevant laboratory values.

The effects of exercise training on cardiovascular diseases have been investigated. In a systematic review, Smart and Marwick8 reported that exercise training was safe in patients with heart failure and that it meaningfully improved peak oxygen consumption. In a meta-analysis, Yang and colleagues9 concluded that exercise-centered cardiac rehabilitation in patients who had undergone PCI led to substantial improvements in recurrent angina, ST-segment patterns, total exercise time, and maximal exercise tolerance. Sunamura and associates10 found that cardiac rehabilitation was associated with improved 10-year survival in patients with AMI who had undergone primary PCI. Unfortunately, most exercise programs are conducted only in the short term, during hospitalization (≤3 mo).

Community-based rehabilitation programs have not been widely used because of perceived difficulties in implementation, monitoring, and follow-up. However, our protocol proved feasible; all patients in the rehabilitation group successfully completed the program and experienced benefits from exercising. Moreover, the program's success stemmed from close cooperation between cardiologists, general practitioners, and study participants and their families.

Our study had some limitations. Patients in the rehabilitation group managed their own exercise and self-recorded their compliance, so information bias may exist. In addition, dietary patterns and psychological states were not monitored during the program and thus may be confounding factors.

Conclusion

We found that community-based physical rehabilitation significantly reduced MACE risk and improved the cardiac function and physical stamina of patients who underwent PCI after AMI.

References

- 1.Zhang L, Desai NR, Li J, Hu S, Wang Q, Li X et al. National quality assessment of early clopidogrel therapy in Chinese patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) in 2006 and 2011: insights from the China Patient-Centered Evaluative Assessment of Cardiac Events (PEACE)-retrospective AMI study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4(7):e001906. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.115.001906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tao J, Wang YT, Abudoukelimu M, Yang YN, Li XM, Xie X et al. Association of genetic variations in the Wnt signaling pathway genes with myocardial infarction susceptibility in Chinese Han population. Oncotarget. 2016;7(33):52740–50. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Montalescot G, Andersen HR, Antoniucci D, Betriu A, de Boer MJ, Grip L et al. Recommendations on percutaneous coronary intervention for the reperfusion of acute ST elevation myocardial infarction. Heart. 2004;90(6):e37. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang Y, Cao H, Jiang P, Tang H. Cardiac rehabilitation in acute myocardial infarction patients after percutaneous coronary intervention: a community-based study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018;97(8):e9785. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000009785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee HY, Kim JH, Kim BO, Byun YS, Cho S, Goh CW et al. Regular exercise training reduces coronary restenosis after percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol. 2013;167(6):2617–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.06.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wolkanin-Bartnik J, Pogorzelska H, Bartnik A. Patient education and quality of home-based rehabilitation in patients older than 60 years after acute myocardial infarction. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2011;31(4):249–53. doi: 10.1097/HCR.0b013e31821c1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salvetti XM, Oliveira JA, Servantes DM, Vincenzo de Paola AA. How much do the benefits cost? Effects of a home-based training programme on cardiovascular fitness, quality of life, programme cost and adherence for patients with coronary disease. Clin Rehabil. 2008;22(10–11):987–96. doi: 10.1177/0269215508093331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smart N, Marwick TH. Exercise training for patients with heart failure: a systematic review of factors that improve mortality and morbidity. Am J Med. 2004;116(10):693–706. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2003.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang X, Li Y, Ren X, Xiong X, Wu L, Li J et al. Effects of exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation in patients after percutaneous coronary intervention: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Sci Rep. 2017;7:44789. doi: 10.1038/srep44789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sunamura M, Ter Hoeve N, van den Berg-Emons RJG, Boersma E, van Domburg RT, Geleijnse ML. Cardiac rehabilitation in patients with acute coronary syndrome with primary percutaneous coronary intervention is associated with improved 10-year survival. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes. 2018;4(3):168–72. doi: 10.1093/ehjqcco/qcy001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]