Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text.

Key Words: engagement, palliative care, transitional care

Background:

Stakeholder involvement in health care research has been shown to improve research development, processes, and dissemination. The literature is developing on stakeholder engagement methods and preliminarily validated tools for evaluating stakeholder level of engagement have been proposed for specific stakeholder groups and settings.

Objectives:

This paper describes the methodology for engaging a Study Advisory Committee (SAC) in research and reports on the use of a stakeholder engagement survey for measuring level of engagement.

Methods:

Stakeholders with previous research connections were recruited to the SAC during the planning process for a multicenter randomized control clinical trial, which is ongoing at the time of this writing. All SAC meetings undergo qualitative analysis, while the Stakeholder Engagement Survey instrument developed by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) is distributed annually for quantitative evaluation.

Results:

The trial’s SAC is composed of 18 members from 3 stakeholder groups: patients and their caregivers; patient advocacy organizations; and health care payers. After an initial in-person meeting, the SAC meets quarterly by telephone and annually in-person. The SAC monitors research progress and provides feedback on all study processes. The stakeholder engagement survey reveals improved engagement over time as well as continued challenges.

Conclusions:

Stakeholder engagement in the research process has meaningfully contributed to the study design, patient recruitment, and preliminary analysis of findings.

The Agency of Healthcare Research and Quality defines stakeholders as “persons or groups who have a vested interest in a clinical decision and the evidence that supports that decision,” and further notes a “stakeholder may be patients, clinicians, caregivers, researchers, advocacy groups, professional societies, businesses, policymakers, or others.”1 Health care research increasingly aims to engage patients, community-based organizations, and other key stakeholders as partners in research, allowing research to be carried out “with” or “by” members of the public rather than “to,” “about,” or “for” them.2–6

Stakeholder involvement enhances research quality, efficiency, and transparency, augments research relevance, and facilitates wider dissemination of results.7–11 Patients, organizations, payers, and other stakeholders may be engaged across different stages of research, including identifying study topics, selecting hypotheses, analyzing data, and disseminating findings.2,12–14 Levels of stakeholder engagement include consultation, collaboration in bidirectional partnerships with researchers, and stakeholder-directed projects.15–17 A systematic review of stakeholder engagement conducted by Concannon et al2 reported that researchers engaged most frequently with patients, modestly with clinicians, and infrequently with other key decision-making groups across the health care system.6 Existing literature supports the importance of stakeholder engagement in health care research, but gaps continue to exist in descriptive information about how to implement such engagement.2,12,18–24

Several studies have proposed process-outcome tools to measure stakeholder involvement, including self-reported stakeholder ratings of engagement, impact on research design, and change in knowledge about research processes; exit surveys; follow-up interviews; or data on improved research quality, processes, and recruitment/retention rates.3,18,23–26 Efforts are underway to validate an engagement tool. A study by Forsythe et al24 characterized stakeholder engagement using a self-report instrument completed by researchers, whereas a further study by Goodman et al27 reported on content validation for a stakeholder engagement tool as well as the preliminarily validated patient engagement in research scale. This paper reports on use of a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Stakeholder Engagement Survey to measure stakeholder engagement from multiple groups over time.6,28,29 These tools have not been fully validated and none are considered a gold standard for evaluating stakeholder experience within the research context.

Emergency Medicine Palliative Care Access (EMPallA) is an ongoing, large, multicenter, randomized controlled trial initiated in 2017 to compare the efficacy of 2 distinct palliative care models among older, emergency department (ED) patients with advanced illness: nurse-led telephonic case management and specialty outpatient palliative care. The PCORI-funded study is being conducted at 18 sites across the country and aims to recruit a diverse group of 1350 older adults living at home with advanced cancer or end-stage organ failure and their caregivers, who visit the ED and are discharged home. Patients are randomized to either be contacted weekly by a Certified Hospice and Palliative Nurse or meet face-to-face monthly with the outpatient specialty palliative care team.30 As of this publication, EMPallA has completed approximately half of its recruitment.

Following the guidelines of the PCORI Engagement Rubric for stakeholder involvement in research, a Study Advisory Committee (SAC) was established at study outset and has been involved in all stages of the research.29 As EMPallA continues, stakeholders will be involved in data analysis and dissemination. We report on current stakeholder engagement outcomes as measured by a Stakeholder Engagement Survey developed by PCORI and administered in November 2018 and December 2019.29 This paper describes the methodology for SAC engagement, highlights the importance of SAC contributions to date, and reports on stakeholder level of engagement.

METHODS

Population and Setting

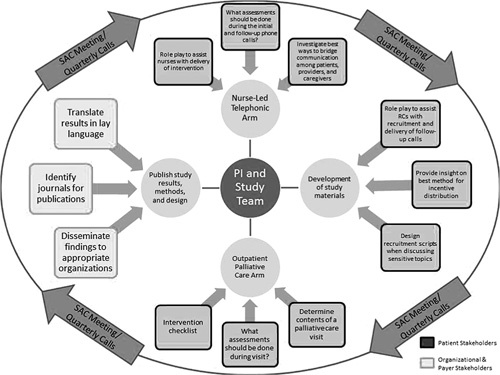

The EMPallA study recruited stakeholders from 3 different categories: (1) patients; (2) organizations; and (3) payers (Fig. 1) based on a history of commitment to patient-centered outcomes research or collaboration with the principal investigator and in accordance with need for demographically and geographically diverse representation. Further stakeholders were identified by word-of-mouth recommendation. Should this form of recruitment have proven unfeasible, contacts from each stakeholder group would have been invited to identify potential members. Stakeholders were recruited during the study planning process in September 2017 and remain engaged throughout the project lifecycle.

FIGURE 1.

Study Advisory Committee (SAC) Engagement Framework. PI indicates principal investigator.

Inclusion Criteria

Relevant patient stakeholders were defined as those either personally experiencing life-limiting illness or their caregivers, allowing intimate comprehension of the needs of our study population and a personal investment in improving the health care system to better serve patient needs. Patient stakeholders were selected based on prior experience in community-based participatory research projects serving diverse populations. To avoid conflicts of interest, SAC members are not participants in the EMPallA study.

Organizational stakeholders were selected to provide content expertise on the clinical context and illnesses of interest (cancer and end-stage organ failure), to facilitate engagement with patients and providers. Initial organizational representatives were identified by contacting organizations relevant to the study’s patient population (eg, cancer, end-stage heart disease) and providers (eg, nursing, emergency medicine, palliative care).

As patient-serving organizations, payer stakeholders provide additional content expertise and are invested in optimally serving patient needs while adopting innovative methods to improve health care quality and reduce cost. Representatives represent a diverse array of geographic contexts (East and West Coasts) and payer types (Medicare Advantage as well as Employee-Based systems).

Engagement Framework and Processes

An initial in-person SAC meeting was held in December 2017 to review the roles, expectations, and steps involved in the research study (Fig. 1). Before this meeting, the Engagement Framework (Fig. 1) was presented to the SAC and accepted by all stakeholders. This defined the role and decision-making authority of the SAC in each component of the research process. Before the meeting, stakeholders received a packet of study materials to review. The principal investigators presented didactic sessions on the phases of research and study background. Group discussions were also held to provide a space for bidirectional dialogue between the investigators and stakeholders, inviting initial feedback and suggestions on the study design.

Since this meeting, SAC engagement has been maintained by quarterly teleconference calls and annual in-person meetings as well as ad hoc. The quarterly teleconference calls convene all stakeholders to facilitate the exchange of information and ideas. The meeting agenda, presentation slides, a synopsis of progress to date and research barriers as well as other preliminary data are circulated for review in advance. The research team solicits additional discussion topics from the stakeholders in advance of each meeting. Members often provide suggestions regarding meeting topics (eg, COVID-19 impacts, racial and ethnic disparities) and share valuable items to disseminate among the SAC. Illustrative patient cases are discussed, affording an in-depth review of how the study affects participant care and experience. Research coordinators and other relevant staff are also invited. Ad hoc calls and meetings are held throughout the year should specific needs arise.

An annual, in-person meeting is held with research staff, coinvestigators, and stakeholders. This meeting lasts for ∼6–8 hours and is a unique opportunity for intergroup collaboration and idea generation. Meeting agendas are planned with stakeholder interests in mind and adapted to stakeholder requests. For example, in response to SAC requests external content experts have presented didactic sessions or conducted focus groups to facilitate discussions and provide a learning environment for SAC members. Recruitment and retention updates, intermediary findings, successes, and challenges are additionally presented, allowing stakeholders to assist research staff in addressing any challenges. Given that several of the stakeholders reside on the West Coast, the 2018 annual meeting was held in California to minimize travel burden. The 2019 annual meeting was held in New York, where the primary research team is based. Given the COVID-19 pandemic, the annual 2020 meeting will occur virtually.

The EMPallA research team continuously ensures that SAC members have appropriate training, resources, and accommodations to effectively serve in their roles and strives for continuous bidirectional information exchange. As such, the study team has altered SAC processes to be as inclusive as possible. Arrangements are made for flights, ground transportation, and hotels to ensure that individuals with limited mobility or disabilities may travel and attend meetings comfortably with medical equipment. Meeting and conference call materials are separately printed in large font for stakeholders with vision impairments and mailed to their home; these stakeholders are also seated closest to the presentation screen for in-person meetings. SAC members with disabilities have attended annual meetings with their caregivers, whose presence provides additional layers of participation. Economic realities are taken into account, including the absence of credit cards, internet access, or access to a scanner/printer among some stakeholders. This may also encourage us to question the expectation of stakeholder responsibilities (such as credit card hold or reimbursable travel expenses), versus an alternate, potentially more socioeconomically just model that strives to ensure equal and full participation of all stakeholders by up-front payment for travel or lodging by the research team. These SAC members provide valuable contextualization and insight for researchers and have triggered a redevelopment of study participant materials, among other changes.

All stakeholders are financially compensated for their time for all meetings and other activities at a common hourly rate. The amount and frequency of compensation was negotiated with the SAC as a single group during initial discussions. Extensive discussion led to agreement for equitable and fair compensation that was blind to professional qualifications or levels of experience.

Engagement Outcome Measurement

Stakeholder engagement in the SAC is measured using a survey instrument that captures quantitative and qualitative feedback. When PCORI was established in 2010 to fund comparative clinical effectiveness research that would assist patients, clinicians, and other health care stakeholders in making informed health decisions,28 the organization developed an Engagement Rubric by drawing from a synthesis of the literature, a qualitative study with patients, a targeted review of Engagement Plans from PCORI-funded project applications and a moderated discussion and review with PCORI’s Advisory Panel on Patient Engagement.7,29 The Engagement Rubric offers recommendations to assist researchers in identifying opportunities for stakeholder engagement in all phases of the research process and relies upon principles for equitable partnerships.27,29 The Rubric has been used as a guide to mobilize SAC members and evaluate their engagement through qualitative reviews of meeting transcripts as well as the administration of the embedded PCORI Stakeholder Engagement Survey.29

The research team administers the PCORI Stakeholder Engagement Survey during the annual meeting (see Engagement Survey, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/MLR/C269). All stakeholders are encouraged to respond, which includes questions on level of influence on the study, self-reported satisfaction with engagement, and challenges faced. Written suggestions to improve stakeholder engagement are also welcomed. The survey comprises 28 questions in a 5-, 4-, or 3-point Likert scale by section, with response choices ranging from “none” to “a great deal.” The survey does not change from year to year.

RESULTS

Stakeholder Characteristics

The SAC comprises 18 stakeholders, 12 women and 6 men representing African American, Asian, and Latino communities (50% White non-Hispanic, 28% Black non-Hispanic, 17% Asian, 6% White Hispanic). Seventeen of 18 SAC members consider English their primary language. At the suggestion of the SAC members in 2018, in 2019 we expanded our study criteria to include Spanish-speaking patients, therefore necessitating the addition of a Latinx SAC member patient stakeholder who was recruited by word of mouth from existing patient stakeholders. The new member was on-boarded primarily by the research team’s Spanish-speaking research coordinator, as she felt more comfortable conversing in Spanish and that partnership continues to flourish. The new member was introduced during a quarterly meeting to ensure inclusivity.

Patient stakeholders provide both geographic and disciplinary diversity, with several holding higher academic degrees. They have a variety of roles and expertise, from leading nonprofit patient advocacy organizations to serving as community faculty at institutions of higher education. All have prior expertise as patient representatives in PCORI- or NIH-funded research and some serve as PCORI Ambassadors.

Organizational stakeholders are comprised of representatives from leading organizations on palliative care, emergency medicine, and transitional care: the American Heart Association, the Society of Academic Emergency Medicine, the Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association, the Emergency Nurses Association, and the American Cancer Society.

Payer stakeholders consist of executive leaders, including a Chief Medical Officer of a large Medicare Advantage Plan, Chief Executive Officer of a health care management firm, and Senior Vice President of a national nonprofit health care company.

Stakeholder Contributions

Each stakeholder group operated within the SAC Engagement Framework (Fig. 1) to provide valuable input to the research process. Patient stakeholders have critically engaged with the research team to codesign protocols, test and assess study components for patient-centeredness, adapt language for patient-facing materials, and translate and disseminate results to ensure they reach the targeted populations. They also play a critical role as simulation trainers for researchers to identify strengths and opportunities in research strategies.

Organizational stakeholders have expressed that they participate in this project as a complement to their existing interventions and to improve the care patients receive at the end of life. Participating organizations work closely with the research team to develop and disseminate communications, including through the use of local patient advocates, providers, and payers to disseminate the study results through social media, community-based outreach, and local academic partners. By promoting the preliminary study findings, these organizations provide credibility and enhance the study’s visibility.

Payer stakeholders provide content expertise on the design and implementation of the telephonic nursing intervention. Results from this branch of the project also support payer groups in making informed decisions on care models to adopt and identify cost-effective interventions for this patient population.

Table 1 outlines the summary of stakeholder contribution and activity by stakeholder group (see Table 1, Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/MLR/C270, which contains descriptions of stakeholder contributions by group).

TABLE 1.

Stakeholder Contributions and Activity by Group

| Stakeholders | Contribution |

|---|---|

| Patient Stakeholders | Suggest ways to approach patients and caregivers during an ED visit, explain the study using lay language, and ensure clear expectations about follow–up to promote retention of study participants upon ED discharge. |

| Advise on study design and materials to ensure all aspects are patient-centered and accessible to patients at home. | |

| Consider patient health literacy. | |

| Assist with refining protocols. | |

| Offer perspectives on how to design the study to accommodate for: health inequities in racial/ethnic minorities, health policy, consumer and senior issues, renal palliative care and caregiver support. | |

| Simulation training for research teams to strengthen recruitment and retention strategies. | |

| Organizational Stakeholders | Develop and deploy communications, including activating local patient advocates, providers and payers to disseminate the results of the study through social media, community-based outreach and local academic partners. |

| Ensure interventions are patient-centered. | |

| Consider patient health literacy. | |

| Payer Stakeholders | Offer suggestions in study design. |

| Provide input in the design of the nurse-led telephonic case management intervention based on the previous success of the program. | |

| Assist in the creation of program materials and nurse protocol. | |

| Provide payer expertise. |

ED indicates emergency department.

Impact of Study Advisory Committee Engagement on the Research Project

Members of the SAC have been involved in each step of the research process. Table 2 summarizes the impact of the SAC on the research project to date. The SAC provided guidance on approaching potential participants and improved the patient-centeredness of the study and its processes. SAC recommendations for changes in patient recruitment strategies led to improved clarity in patient-facing materials and greater transparency in describing research aims. Stakeholder input led to the critical change in study design to unblind research staff, enabling researchers to assist enrolled patients in scheduling an outpatient clinic appointment following ED discharge. The need for ensuring high-quality patient care was deemed more important than this introduction of possible bias. Stakeholders played an important role in contextualizing the barriers that patients and caregivers face when coordinating appointments and follow-up visits after an ED visit.

TABLE 2.

Stakeholder Impact on Research

| Research Phase | Stakeholder Impact |

|---|---|

| Proposal development (complete) | Feedback on the comparators and outcomes of interest |

| Suggested loneliness as a study outcome | |

| Study design (complete) | Shared existing nurse training materials and nursing assessments |

| Provided feedback on language materials | |

| Recommended motivational and CAPC training to nurses | |

| Recommended switch from blinding to unblinding of research staff | |

| Recruitment of study participants (ongoing) | Developed recruitment scripts for nurses and research coordinators |

| Pilot-tested recruitment scripts | |

| Developed approach to patients and caregivers engagement | |

| Retention of study participants (ongoing) | Suggested patient-facing brochure outlining timeline, compensation type, and frequently asked questions |

| Recommended calling participants at different times during the day | |

| Proposed reminder postcards after initial enrollment |

CAPC indicates Center to Advance Palliative Care.

Study Advisory Committee Engagement Outcomes

Three in-person meetings have been held to date. Seventeen stakeholders attended the project kick-off meeting in December 2017, 15 attended the meeting in November 2018, and 11 attended in December 2019. Unfortunately, scheduling conflicts and 1 members’ inability to travel due to illness resulted in lower attendance during the December 2019 in-person meeting. The PCORI Stakeholder Engagement Survey was not distributed at the project kick-off meeting, as the study had just been initiated. Ninety-three percent (n=14) of 2018 stakeholder attendees responded to the PCORI Stakeholder Engagement Survey, and 100% of 2019 attendees (n=11) responded; results are reported separately below. Stakeholders responded to questions on 3 different topics: (1) amount of influence on each phase of the research process; (2) experience with the EMPallA study; and (3) engagement challenges.

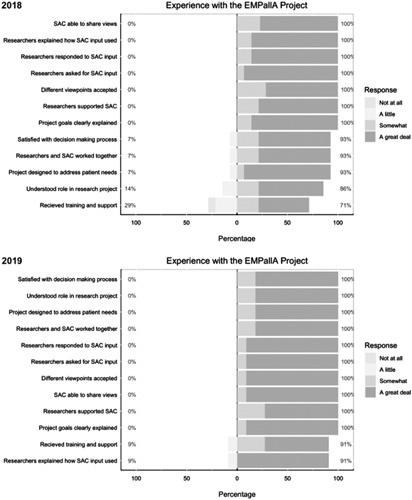

2018 Meeting

In rating their experience as a member of the study team, 86% (n=12) of stakeholders felt “a great deal” that the researchers clearly explained project goals and how stakeholder input was used, that researchers responded to stakeholder input, and that the project was designed to address patient needs (Fig. 2). Ninety-three percent (n=13) felt “a great deal” that researchers asked for their input. However, only 71% (n=10) felt that they received “somewhat” or “a great deal” of training and support to engage with the research team (Fig. 2).

FIGURE 2.

SAC engagement survey results: experience with the project. EMPallA indicates Emergency Medicine Palliative Care Access; SAC, Study Advisory Committee.

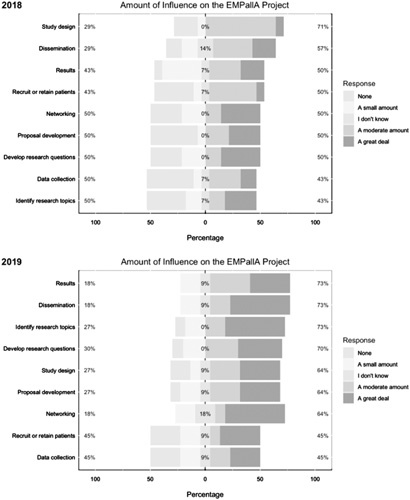

In rating their amount of influence on the study, 71% (n=10) of stakeholders felt that they had at least “a moderate amount” of influence on the study design, and 57% (n=8) felt that they had a role in proposal development and plans for dissemination of study findings (Fig. 3).

FIGURE 3.

Study Advisory Committee engagement survey results: influence on the project. EMPallA indicates Emergency Medicine Palliative Care Access.

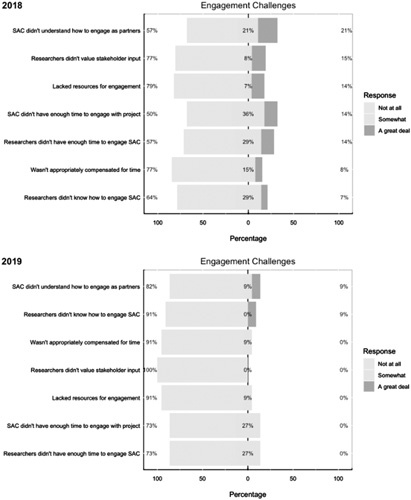

With regards to challenges they faced in engaging with the research team, 50% (n=7) of stakeholders felt at least “somewhat” that they did not have adequate time to engage with the project (Fig. 4). Just under half (43%, n=6) of stakeholders felt at least “somewhat” that researchers did not have enough time to engage them in the project, and that stakeholders did not have enough knowledge about engaging in research as partners (Fig. 4). However, more than three quarters of the stakeholders surveyed felt adequately valued and compensated as partners and felt they had the resources needed to perform their role.

FIGURE 4.

Study Advisory Committee (SAC) engagement survey results: engagement challenges.

2019 Meeting

As members of the study team, stakeholders continued to feel “a great deal” that the project goals were explained clearly, stakeholders were given a chance to share their views/researchers asked for their input, and researchers clearly explained how the input from stakeholders was used (91%, n=10). All stakeholders (100%, n=11) reported that they felt strongly that researchers valued the stakeholders’ input. By this point, 91% (n=10) felt that they received “somewhat” or “a great deal” of training and support to engage with the researchers (Fig. 2).

By December 2019, more than half of the stakeholders (55%) felt that they had contributed “a great deal” in the following research phases: identifying the research topic, networking and expanding the research team, and dissemination/sharing study findings. Approximately one third (36%, n=4) of the stakeholders experienced contributing “a great deal” in developing the research question, proposal development, study design, recruitment or retainment of study participants, and results review, interpretation, or translation (Fig. 3).

Reevaluating challenges revealed that only 27% of SAC members felt that the researchers and stakeholders at least “somewhat” lacked adequate time for engagement. About 91% (n=10) of respondents felt that researchers had sufficient knowledge on how to engage with stakeholders as partners, whereas only 18% (n=2) identified that stakeholders were at least “somewhat” lacking in knowledge of how to engage in research partnerships. Stakeholders continued to feel valued “a great deal” (100%, n=11), as well as appropriately compensated and given adequate resources (91%, n=10) (Fig. 4).

DISCUSSION

The EMPallA SAC is composed of multiple, diverse groups whose contributions toward the EMPallA study have resulted in numerous study improvements at all stages of the research process thus far. As described in the Engagement outcomes measurement section, the partnership between SAC and research team is an evolving and fruitful process and we look forward to reporting on more outcomes data in the future. As of 2019, the SAC reported high engagement with 100% who felt strongly that researchers valued their input; 91% clearly understood the project goals and felt supported and more than half felt they have greatly contributed to identifying research topics, expanding the research team, and disseminating results. Early SAC engagement was facilitated by building on existing relationships, although detailed research discussions were held only once the SAC held formal meetings to ensure fair compensation for time. We believe that transparency, clear understanding of roles, and mutual respect for life experiences has helped attain a high engagement rate.

Previous studies on stakeholder engagement in research reported similar groups of stakeholders, impacts on research processes, and challenges to engagement.24,31–35 A review of 50 pilot projects funded by PCORI found that stakeholders influence multiple levels of the research process, providing input on study design, data collection tools, recruitment strategies, and interpretation of research findings from the patient perspective. In contrast, through concerted recruitment efforts the EMPallA SAC was able to engage payers, a stakeholder group with little representation in these previous studies.24 The EMPallA study additionally cultivated long-term stakeholder partnership-building instead of the broader approach present in other studies of multilevel input-gathering across several platforms.31,33,35 Initial challenges in other studies mirrored our own, with lack of stakeholder and researcher time for engagement cited most frequently and gradually resolving over time.24 Measuring stakeholder level of engagement remains a widespread challenge for research teams and multiple quantitative measures have been explored with limited validity.6,24,33

Limitations

Limitations include lack of engagement survey participation from all stakeholders (88% in 2018, n=16; 61% in 2019, n=18) as we were limited to responses from in-person meeting attendees. In addition, surveys were not anonymous, which could have biased responses. We also did not offer a Spanish version of the survey either year. Lastly, we distributed the survey at meetings’ end, which may have biased responses favorably.

CONCLUSIONS

The early initiation and continued engagement of stakeholders in research improves the research process and promotes more patient-centered results. Following guidelines such as the PCORI Engagement Rubric as well as developing an engagement plan may promote meaningful exchange between research staff and stakeholders. Using an instrument that captures both quantitative and qualitative engagement feedback may assist in identifying areas of strength or improvement in stakeholder engagement processes. With stakeholder involvement in health care research, there is an urgent need to develop a robust evaluation tool to ensure that engagement is meaningful for both stakeholders and researchers. The EMPallA study’s engagement with the SAC demonstrates the added value of stakeholder engagement and provides valuable insight into the adaptations, strengths, and challenges encountered in the research process when developing meaningful exchange with stakeholders.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal's website, www.lww-medicalcare.com.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the members of the EMPallA Study Advisory Committee for their contributions to this article.

Footnotes

This work was supported through a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Award (16-093-6306).

All statements in this report, including its findings and conclusions, are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), its Board of Governors or Methodology Committee.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Claire de Forcrand, Email: deforcrandde@wisc.edu.

Mara Flannery, Email: Mara.Flannery@nyulangone.org.

Jeanne Cho, Email: jeannehcho@gmail.com.

Neha Reddy Pidatala, Email: nehapreddy@gmail.com.

Romilla Batra, Email: rbatra@scanhealthplan.com.

Juanita Booker-Vaughns, Email: toreyon64@yahoo.com.

Garrett K. Chan, Email: gchanrn@yahoo.com.

Patrick Dunn, Email: Pat.Dunn@heart.org.

Robert Galvin, Email: Robert.Galvin@Blackstone.com.

Ernest Hopkins, Email: ernesthopkins2004@yahoo.com.

Eric D. Isaacs, Email: Eric.Isaacs@ucsf.edu.

Constance L. Kizzie-Gillett, Email: ckizgil@gmail.com.

Margaret Maguire, Email: Margaret.Maguire@regence.com.

Martha Navarro, Email: marthanavarro@cdrewu.edu.

Dawn Rosini, Email: dawnne_dmr@yahoo.com.

William Vaughan, Email: wkvjee@hotmail.com.

Sally Welsh, Email: Welsh816@comcast.net.

Pluscedia Williams, Email: pluscedia.williams@gmail.com.

Angela Young-Brinn, Email: confidenceplus2000@gmail.com.

Corita R. Grudzen, Email: corita.grudzen@nyulangone.org.

REFERENCES

- 1. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. AHRQ Effective Health Care Program Stakeholder Guide, no. 14-EHC010-EF. Rockville, MD: AHRQ Publication; 2014.

- 2. Concannon TW, Fuster M, Saunders T, et al. A systematic review of stakeholder engagement in comparative effectiveness and patient-centered outcomes research. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29:1692–1701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Deverka PA, Lavallee DC, Desai PJ, et al. Stakeholder participation in comparative effectiveness research: defining a framework for effective engagement. J Comp Eff Res. 2012;1:181–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kok MO, Gyapong JO, Wolffers I, et al. Which health research gets used and why? An empirical analysis of 30 cases. Heal Res Policy Syst. 2016;14:36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Viswanathan M, Ammerman A, Eng E, et al. Community-based participatory research: assessing the evidence. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Summ). 2004;99:1–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Harrison JD, Auerbach AD, Anderson W, et al. Patient stakeholder engagement in research: a narrative review to describe foundational principles and best practice activities. Health Expect. 2019;22:307–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Committee on Comparative Effectiveness Research Prioritization, Institute of Medicine. Initial National Priorities for Comparative Effectiveness Research. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sox HC, Greenfield S. Comparative effectiveness research: a report from the Institute of Medicine. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:203–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Roehr B. More stakeholder engagement is needed to improve quality of research, say US experts. BMJ. 2010;341:c4193. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Federal Coordinating Council for Comparative Effectiveness Research. Report to the President and Congress. Washington; 2009.

- 11. Mockford C, Staniszewska S, Griffiths F, et al. The impact of patient and public involvement on UK NHS health care: a systematic review. Int J Qual Health Care. 2012;24:28–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shippee ND, Domecq Garces JP, Prutsky Lopez GJ, et al. Patient and service user engagement in research: a systematic review and synthesized framework. Health Expect. 2015;18:1151–1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mullins CD, Abdulhalim AM, Lavallee DC. Continuous patient engagement in comparative effectiveness research. JAMA. 2012;307:1587–1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Goodman S Aronson N Basch E, et al. PCORI Methodology Report PCORI Methodology Committee Executive Director of Clinical Evaluation, Innovation, and Policy, Blue Cross and Blue Shield Association (BCBSA) PCORI Methodology Report II. 2019. Available at: http://www.pcori.org/methodology-standards . Accessed July 20, 2020.

- 15. Roger S. Involving the public in NHS, public health, and social care research: briefing notes for researchers (2nd ed). Health Expect. 2005;8:91–92. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Salmi L, Lum HD, Hayden A, et al. Stakeholder engagement in research on quality of life and palliative care for brain tumors: a qualitative analysis of #BTSM and #HPM tweet chats. NeuroOncol Pract. 2020;7:676–684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cutshall NR, Kwan BM, Salmi L, et al. “It Makes People Uneasy, but It’s Necessary. #BTSM”: using Twitter to explore advance care planning among brain tumor stakeholders. J Palliative Med. 2020;23:121–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Brett J, Staniszewska S, Mockford C, et al. Mapping the impact of patient and public involvement on health and social care research: a systematic review. Health Expect. 2014;17:637–650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Forsythe LP, Szydlowski V, Murad MH, et al. A systematic review of approaches for engaging patients for research on rare diseases. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(suppl 3):S788–S800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Boote J, Baird W, Sutton A. Public involvement in the design and conduct of clinical trials: a narrative review of case examples. Trials. 2011;12(suppl 1):A82. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Staley K. Exploring Impact: Public Involvement in NHS, Public Health and Social Care Research. INVOLVE, Eastleigh; 2009.

- 22. Staniszewska S, Brett J, Mockford C, et al. The GRIPP checklist: strengthening the quality of patient and public involvement reporting in research. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2011;27:391–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Forsythe LP, Carman KL, Szydlowski V, et al. Patient engagement in research: early findings from the patient-centered outcomes research institute. Health Affairs. 2019;38:359–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Forsythe LP, Ellis LE, Edmundson L, et al. Patient and stakeholder engagement in the PCORI pilot projects: description and lessons learned. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31:13–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dudley L, Gamble C, Preston J, et al. What difference does patient and public involvement make and what are its pathways to impact? Qualitative study of patients and researchers from a cohort of randomised clinical trials. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0128817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Domecq JP, Prutsky G, Elraiyah T, et al. Patient engagement in research: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Goodman MS, Ackermann N, Bowen DJ, et al. Content validation of a quantitative stakeholder engagement measure. J Community Psychol. 2019;47:1937–1951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Frank L, Basch E, Selby JV. The PCORI perspective on patient-centered outcomes research. JAMA. 2014;312:1513–1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Patient-Centred Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI). PCORI Engagement Rubric. 2015. Available at: http://www.pcori.org/sites/default/files/Engagement-Rubric.pdf. Accessed July 20, 2020.

- 30. Grudzen CR, Shim DJ, Schmucker AM, et al. Emergency Medicine Palliative Care Access (EMPallA): protocol for a multicentre randomised controlled trial comparing the effectiveness of specialty outpatient versus nurse-led telephonic palliative care of older adults with advanced illness. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e025692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ellis LE, Kass NE. How are PCORI-funded researchers engaging patients in research and what are the ethical implications? AJOB Empir Bioeth. 2017;8:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Manafo E, Petermann L, Mason-Lai P, et al. Patient engagement in Canada: a scoping review of the “how” and “what” of patient engagement in health research. Health Res Policy Syst. 2018;16:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Goodman MS, Sanders Thompson VL. The science of stakeholder engagement in research: classification, implementation, and evaluation. Transl Behav Med. 2017;7:486–491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Forsythe L, Heckert A, Margolis MK, et al. Methods and impact of engagement in research, from theory to practice and back again: early findings from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. Qual Life Res. 2018;27:17–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Boyer AP, Fair AM, Joosten YA, et al. A multilevel approach to stakeholder engagement in the formulation of a clinical data research network. Med Care. 2018;56(10 suppl 1):S22–S26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal's website, www.lww-medicalcare.com.