Background:

This Special Issue, Future Directions in Transitional Care Research, focuses on the approaches used and lessons learned by researchers conducting care transitions studies funded by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI). PCORI’s approach to transitional care research augments prior research by encouraging researchers to focus on head-to-head comparisons of interventions, the use of patient-centered outcomes, and the engagement of stakeholders throughout the research process.

Objectives:

This paper introduces the themes and topics addressed by the articles that follow, which are focused on opportunities and challenges involved in conducting patient-centered clinical comparative effectiveness research in transitional care. It provides an overview of the state of the care transitions field, a description of PCORI’s programmatic objectives, highlights of the patient and stakeholder engagement activities that have taken place during the course of these studies, and a brief overview of PCORI’s Transitional Care Evidence to Action Network, a learning community designed to foster collaboration between investigators and their research teams and enhance the collective impact of this body of work.

Conclusions:

The papers in this Special Issue articulate challenges, lessons learned, and new directions for measurement, stakeholder engagement, implementation, and methodological and design approaches that reflect the complexity of transitional care comparative effectiveness research and seek to move the field toward a more holistic understanding of transitional care that integrates social needs and lifespan development into our approaches to improving care transitions.

Key Words: transitional care, comparative effectiveness research, patient-centered

BACKGROUND

Care transitions occur when patients move between health care settings or practitioners, such as the transition from an acute care setting to a skilled nursing facility or home.1,2 Discontinuity of care and inadequate communication between providers may contribute to adverse events, delay care, lead to unnecessary hospital visits, increase patient and family distress, and contribute to poorer health outcomes.3 Medicare alone spends $26 billion annually on hospital readmissions, of which $17 billion is spent on avoidable readmissions,4 with roughly 30% of patients experiencing at least 1 discrepancy between their discharge list of medications and the medications they actually take at home.5

During the past 2 decades, the field of transitional care has witnessed a proliferation of evidence-based interventions to support high-quality care transitions for patients and families. Research has explored the efficacy and effectiveness of interventions to enhance communication and foster care continuity, utilizing elements such as home visits, multidisciplinary teams, a single point of contact (transition coach, nurse, etc.), patient education on self-management, tailored discharge care planning and phone calls, and medication reconciliation and management.6–8 Findings have demonstrated the potential for improvements in care continuity and reductions in readmission rates.8–11 However, understanding the comparative effectiveness of transitional care interventions, particularly which interventions work best for which populations, has proven challenging.

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of care transitions interventions have been hampered by small sample sizes and the heterogeneity of study settings, patient populations, and combinations of intervention components, which render comparisons difficult.12 Biological factors also play a role in the heterogeneity of transition issues, as rates of readmission can vary 2-fold or more by age, even within a diagnosis such as sickle cell disease.13 Variance in costs for readmissions suggests corollary variance in the complexity of readmissions: readmission for blood disorders may cost double that of mental/behavioral disorders.14 Evidence to date has focused heavily on transitions from hospital settings, with relatively less emphasis on the role of primary care teams or transitions between other settings (such as rehabilitation or long-term care).15 A dearth of high-quality evidence persists for mental health, surgical, and adolescent/emerging adult populations,16,17 and transitional care interventions have not been uniformly effective across, or even within, patient populations.11,18,19 This variability suggests that contextual factors, such as social determinants of health, community resources, external policy incentives, or the delivery environment may play a role in shaping outcomes.20,21

Aligning with the “triple aim” of improving the individual experience of care, improving population health, and reducing health care costs,22 hospital readmission rates have been viewed as a gold standard for assessing the impact of care transitions interventions, reflected by the use of 30-day readmissions to anchor quality metrics, reimbursement policies, and penalties associated with transitional care.23 Other common outcomes measured include avoidable readmissions, emergency department (ED) visits, and lengths of stay, as well as clinical outcomes.7,24,25 Researchers and other stakeholders in the care transitions field increasingly recognize the potential limitations of a singular focus on readmissions and have begun to acknowledge the value of employing patient-centered outcomes.18,26

Patient-centered outcomes research provides an opportunity for researchers to partner with patients, families, clinicians, delivery systems leaders, and other stakeholders to assess outcomes that are meaningful and important to patients and caregivers, and enhance the relevance of research findings for end users.27 For example, using measures of functional status, days at home, or patient experience alongside utilization or readmission rates may provide a more holistic view of the care transitions experience.28 Balancing readmission rates with the assessment of a range of stakeholder-driven outcomes is especially important for underserved populations, estimated to compose up to 30% of patients discharged from the hospital.21 However, the use of patient-centered outcomes in research and clinical settings is a relatively recent development, which may contribute to challenges in the collection, interpretation, and communication of such results.29,30 Investigators may face challenges publishing studies using patient-centered outcomes in professional and trade journals accustomed to seeing readmissions used as the primary outcome in care transitions studies. Finally, questions remain regarding how to integrate patient-centered outcomes into clinical workflow and feedback loops in a meaningful way.31

While a handful of studies have compared transitional care interventions,32–36 knowledge gaps remain regarding the impact of these interventions in different subpopulations, in real-world settings, and on outcomes beyond costs and readmissions.23,33 The state of the evidence underscores the need for head-to-head trials of interventions that can distinguish what intervention components (or combinations of components) work best for which individuals and settings; the need for adaptive methods and pragmatic designs responsive to the complexity of transitional care research conducted in real-world settings; the need to select outcomes representing the perspectives of patients, family members, and other key stakeholders; and the need to establish a means to meaningfully triangulate, evaluate, and deploy validated patient-centered outcomes alongside utilization outcomes. In this Special Issue, we share evidence and insights from a portfolio of research studies that have inhabited these emergent spaces of design, methodology, and patient-centeredness, using stakeholder-driven outcomes to understand what intervention strategies and models work best for whom, under what circumstances.

Transitional Care Research Funded by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute

The Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) is a nonprofit, nongovernmental organization established to fund research that can help people make informed health care decisions and improve health care delivery and outcomes by producing and promoting high-integrity, evidence-based information guided by patients, caregivers, and the broader health care community.37 PCORI’s focus is on funding comparative effectiveness research, using a stakeholder-driven approach that includes patients and other health care stakeholders throughout the research process, to assure the resulting evidence is relevant to end users. A recent analysis of PCORI-funded research suggests engagement of patients and other health care stakeholders “contributes to identifying research questions and outcomes important to patients and clinicians, recruitment and retention of study participants, data collection processes, interpretation of results, and dissemination.27”

Some of PCORI’s transitional care studies were funded as investigator-initiated topics, while others were funded under the auspices of targeted funding announcements in transitional care, sickle cell disease, and palliative care. Targeted announcements utilize stakeholder input to shape topics and questions of high potential impact. To date, PCORI has made a $128 million investment to fund 29 transitional care studies. This portfolio of funded work augments prior research with its focus on head-to-head comparison of interventions, patient-centeredness, explorations of heterogeneity of treatment effects within subgroups, and the use of stakeholder-driven questions, outcomes, and intervention design. Further, while this body of work is inclusive of outcomes traditionally used in transitional care research (eg, utilization, readmissions patient-reported outcomes), it extends and complements those outcomes via the inclusion of patient-centered outcomes deemed important by stakeholders. Among the studies with published results, several demonstrated statistically significant findings for patient-centered outcomes such as quality of life, patient concerns, self-efficacy, and patient activation.38–41

At the time of funding application, research teams were required to outline how patients and other national or regional health care system stakeholders would participate as partners in the proposed research throughout the study. Although patient and stakeholder engagement in PCORI’s funded research awards is required and supported, study teams are encouraged to structure and operationalize engagement mechanisms to best suit their study design and vision for engagement, and provided guidance through PCORI’s Engagement Rubric and PCORI’s Methodology Standards.42,43 Stakeholder engagement is a core activity woven throughout all 29 studies, with unique engagement approaches taken in each study. The stakeholder partners engaged through these awards are diverse and representative of the key contributors to the transitional care landscape. On average, each of these studies engages with 7 stakeholder communities (range: 4–11). These include patients and caregivers who have experienced care transitions, community-based organizations, clinicians, clinic, hospital or health system leaders, policymakers, payer organizations, and advocacy organizations, among others.

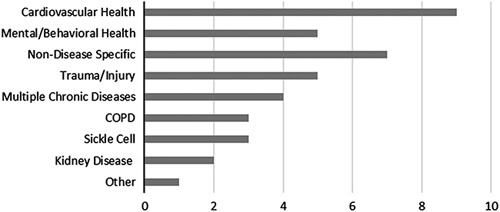

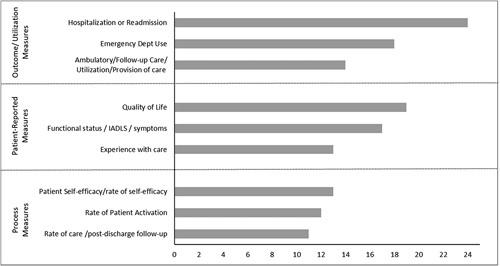

The 29 PCORI-funded transitional care studies were designed to test the comparative effectiveness of approaches to reducing readmissions, improving the patient experience, and improving outcomes important to a range of stakeholders, including patients, family members, clinicians, health systems leaders, and payers. Of the 29 studies, 26 test interventions using experimental designs (24 randomized and 2 quasi-experimental), 2 are observational, and 1 focuses on measure development. The studies encompass a broad range of populations and settings, including studies of transitions among a variety of settings and providers, and studies focused on transitions from adolescent to adult care. Transition settings include EDs, hospital, home, rehabilitation or skilled nursing facilities, and outpatient specialty care, with 7 projects focused on transitions between multiple sites. Figure 1 illustrates the range of health conditions represented in the portfolio, including conditions such as substance use disorder, traumatic brain injury, stroke, sickle cell disease, and serious mental illness. All the studies use multicomponent interventions, utilizing components such as technological interventions, education, coaching, discharge or care planning, and peer support. A strength and unique contribution of the PCORI-funded transitional care portfolio is the breadth of settings (including multiple settings) and the variety of outcomes studied.44 The most commonly assessed outcomes are listed in Figure 2 and include utilization (ie, hospitalization, readmission, and ED use), quality of life, functional status, and patient-centered outcomes such as patient or caregiver self-efficacy and patient care experience. Patients and stakeholders were involved in the selection and refinement in the interventions and outcomes studied: summary statistics provided by PCORI’s evaluation and analysis team showed that among the studies with completed engagement reports at the time of this inquiry (26/29), 92 percent reported engagement with patients and stakeholders on the selection of interventions and 88% engaged stakeholders on the selection or measurement of outcomes.

FIGURE 1.

Health conditions represented among 29 PCORI-funded transitional care studies*. *Categories are not mutually exclusive, therefore an individual study may include multiple diseases or conditions. COPD indicates chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; PCORI, Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute.

FIGURE 2.

Most commonly assessed outcomes collected among 29 PCORI-funded transitional care studies. IADL indicates instrumental activities of daily living; PCORI, Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute.

The Transitional Care Evidence to Action Network

In 2015, PCORI established a learning community to support awardee teams funded within the transitional care portfolio: The Transitional Care Evidence to Action Network, or TC-E2AN. The TC-E2AN connects PCORI-funded investigators and their teams, spanning 16 states and the District of Columbia. The TC-E2AN is intended to bolster and accelerate the research process by serving as an incubator for collaborative learning, a forum for the development of research products, and a platform to shift the evidence conversation from individual studies to a portfolio level. The 29 transitional care studies were funded over a 7-year period, allowing the network to leverage learning from earlier-funded studies to inform the problem-solving and best practices of later studies. A key focus of the network has been understanding the role of patient-centered outcomes in the transitional care context, and how best to interpret and communicate emergent results. The network has also sought to understand the role of engagement in its studies. To that end, in 2016 the network involved patient partners on transitional care projects in a journey mapping exercise to share their experiences as members of transitional care research teams. Common themes were shared with researchers for discussion on how patients can most meaningfully and effectively partner with research teams.45 Collaboration within the TC-E2AN directly informed the development of this Special Issue, as members collectively shared experiences and insights to inform their findings and the field more broadly.

Setting the Stage: Findings and Lessons Learned From the Portfolio

The papers composing this Special Issue (Table 1) represent 11 of the 29 studies transitional care studies funded by PCORI, some of which are ongoing and some of which are completed. These papers also represent highlights from the TC-E2AN’s collective thinking and work over the past 5 years. Together, these papers contribute to the field of transitional care research and practice by offering insights and lessons learned from a portfolio of studies enacting the principles of patient and stakeholder engagement, integrating patient-centered outcomes, utilizing head-to-head comparisons of interventions, and acknowledging the complexity of transitional care. This collection of empirically driven manuscripts, guest commentaries, and editorials integrates the viewpoints of a broad range of stakeholders. The first paper presents a framework to articulate the nuanced similarities and differences between patient-centered outcomes and patient-reported outcomes. Reeves and colleagues discuss the opportunities and challenges of integrating patient-centered outcomes into transitional care research and call for the harmonization and standardization of patient-centered outcomes measures that are valid and reliable.46 The second paper by Gesell and colleagues invites us to understand lessons learned in the implementation of the PCORI transitional care studies.47 Using case studies, this paper grapples with the tensions inherent in conducting complex interventions in real-world settings and offers guidance in navigating those tensions. A third paper addresses methodological and analytical considerations associated with the deployment of a pragmatic care transitions trial. Authors Psioda and colleagues describe the application of cutting-edge statistical approaches to evaluate comparative effectiveness in the presence of complex data emanating from the pragmatic nature of the study.48

TABLE 1.

Transitional Care Evidence to Action Network (TC-E2AN) Papers Presented in the Special Issue

| Title | Authors |

|---|---|

| Opening Pandora’s Box: from readmissions to patient-centered outcomes measures (PCOM) in transitional care46 | Mathew J. Reeves; Michele C. Fritz; Ifeyinwa Osunkwo; Corita R. Grudzen; Lewis L. Hsu; Jing Li; Raymona H. Lawrence; Janet Prvu Bettger |

| Implementation of complex interventions: lessons learned from the PCORI Transitional Care Portfolio47 | Sabina B. Gesell; Janet Prvu Bettger; Raymona H. Lawrence; Jing Li; Jeanne Hoffman; Barbara J. Lutz; Corita Grudzen; Anna M. Johnson; Jerry A. Krishnan; Lewis L. Hsu; Dorien Zwart; Mark V. Williams; Jeffrey L. Schnipper |

| Methodological challenges & statistical approaches in the Comprehensive Post-Acute Stroke Services (COMPASS) Study48 | Matthew A. Psioda; Sara B. Jones; James G. Xenakis; Ralph B. D’Agostino |

| Short-term focused feedback: a model to enhance patient engagement in research and intervention delivery49 | Hadley Sauers-Ford; Angela M. Statile; Katherine A. Auger; Susan Wade-Murphy; Jennifer M. Gold; Jeffrey M. Simmons; Samir S. Shah |

| Pragmatic considerations in incorporating stakeholder engagement into a palliative care transitions study50 | Corita R. Grudzen; Claire de Forcrand; Mara Flannery; Jeanne Cho; Martha Navarro; Patrick Dunn; Eric Isaacs; Eric Isaacs; Sally Welsh; Pluscedia Williams; Angela Young-Brinn; Juanita Booker-Vaughns; Dawn Rosini; Ernest Hopkins; Neha Reddy Pidatala; Margaret Maguire; Robert Galvin; Garrett Chan; Constance Kizzie-Gillette; Romilla Batra; William Vaughan |

| Catalyzing the translation of patient-centered research into United States Trauma Care Systems: a case example51 | Douglas Zatzick; Kathleen Moloney; Lawrence Palinkas; Peter Thomas; Kristina Anderson; Lauren Whiteside; Deepika Nehra; Eileen Bulger |

| How do care transitions work? Unraveling the working mechanisms of care transition interventions52 | Dorien L.M. Zwart, Jeffrey L. Schnipper, Debbie Vermond, and David W. Bates |

The next 2 papers highlight the role of patient engagement in effective intervention deployment throughout the research process. Sauers-Ford and colleagues discuss how engaging many families and stakeholders over short periods via focus groups and individual interviews (ie, short-term focused engagement) can be leveraged alongside traditional stakeholder engagement approaches to improve transitional care interventions.49 This contribution is followed by a complementary paper by de Forcrand and colleagues articulating an approach for effectively integrating stakeholder perspectives into research.50 Together, these 2 papers offer concrete approaches to enacting meaningful patient and stakeholder engagement within the context of rigorous research. The final 2 empirically driven papers in this issue invite us to consider the interface of research, implementation, and policy. Zatzick and colleagues trace the historical development of patient-centered policy guidance and describe care transition conceptual frameworks that aim to maximize real-world health care system impacts.51 Finally, authors Zwart and colleagues present a conceptual framework from their qualitative inquiry that helps us understand the contextual factors and mechanisms that impact successful care transition interventions.52 The issue concludes with commentaries highlighting future research, practice, and policy directions.

CONCLUSION AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Given the persistence of care fragmentation in the US health care system, innovations to improve transitional care continue to be relevant. By engaging stakeholders in comparative effectiveness research, PCORI’s 29 transitional care studies and the TC-E2AN contribute to this knowledge base and inform the next steps in research, policy, and practice. The papers in this Special Issue articulate challenges and lessons learned, and identify new directions for measurement, patient and stakeholder engagement, implementation, and methodological approaches that reflect the complexity of transitional care research. They also move us toward a more holistic understanding of transitional care that integrates social needs and lifespan developmental transitions into our approaches to improving transitional care.

While many studies are in process, the papers highlighted in this issue demonstrate PCORI’s substantial investment to develop stakeholder-informed research with the potential to enhance the impact of transitional care research. As articulated in these papers and the accompanying commentaries, this body of work provides signposts for future directions in transitional care research that incorporate stakeholders in meaningful ways, enact a nuanced understanding of the relationship between readmissions and other transitional care outcomes (including patient-centered outcomes), explore the role of contextual factors in transitional care interventions and outcomes, and utilize mixed methods and/or hybrid designs to support the interpretation and more expedient translation of evidence into practice.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Carly Parry, Email: cparry@pcori.org.

Aaron Shifreen, Email: ashifreen@pcori.org.

Steven B. Clauser, Email: sclauser@pcori.org.

REFERENCES

- 1. Coleman EA, Boult C. Improving the quality of transitional care for persons with complex care needs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:556–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. The Joint Commission. Hot topics in health care, issue #2. Transitions of care: the need for collaboration across entire care continuum; 2013. Available at: www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/6/TOC_Hot_Topics.pdf. Accessed June 5, 2020.

- 3. Clarke JL, Bourn S, Skoufalos A, et al. An innovative approach to health care delivery for patients with chronic conditions. Popul Health Manag. 2017;20:23–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hines A Barret M Jiang J, et al. Conditions With the largest number of adult hospital readmissions by payer, 2011. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; April 2014 (HCUP Statistical Brief #172). Available at: www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb172-Conditions-Readmissions-Payer.pdf. Accessed June 5, 2020.

- 5. da Silva BA, Krishnamurthy M. The alarming reality of medication error: a patient case and review of Pennsylvania and National data. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2016;6:31758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Blum MR, Øien H, Carmichael HL, et al. Cost-effectiveness of transitional care services after hospitalization with heart failure. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172:248–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kamermayer AK, Leasure AR, Anderson L. The effectiveness of transitions-of-care interventions in reducing hospital readmissions and mortality: a systematic review. Dimens Crit Care Nurs. 2017;36:311–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Le Berre MA, Maimon G, Sourial N, et al. Impact of transitional care services for chronically ill older patients: a systematic evidence review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65:1597–1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Branowicki PM, Vessey JA, Graham DA, et al. Meta-analysis of clinical trials that evaluate the effectiveness of hospital-initiated postdischarge interventions on hospital readmission. J Healthc Qual. 2017;39:354–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Community-based Care Transitions Program; 2020. Available at: https://innovation.cms.gov/innovation-models/cctp. Accessed June 5, 2020.

- 11. Leppin AL, Gionfriddo MR, Kessler M, et al. Preventing 30-day hospital readmissions: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:1095–1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Penney LS, Nahid M, Leykum LK, et al. Interventions to reduce readmissions: can complex adaptive system theory explain the heterogeneity in effectiveness? A systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18:894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fingar K Owens P Reid L, et al. Characteristics of inpatient hospital stays involving sickle cell disease, 2000-2016 #251. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; September 2019. Report No.: Statistical Brief #251. Available at: https://hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb251-Sickle-Cell-Disease-Stays-2016.jsp. Accessed July 8, 2020. [PubMed]

- 14. Bailey M Weiss AJ Barrett ML, et al. Characteristics of 30-day all-cause hospital readmissions, 2010-2016 #248. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; February 2019. Report No.: Statistical Brief #248. Available at: www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb248-Hospital-Readmissions-2010-2016.jsp. Accessed July 8, 2020. [PubMed]

- 15. Freeman S, Bishop K, Spirgiene L, et al. Factors affecting residents transition from long term care facilities to the community: a scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17:689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jones CE, Hollis RH, Wahl TS, et al. Transitional care interventions and hospital readmissions in surgical populations: a systematic review. Am J Surg. 2016;212:327–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Paul M, Street C, Wheeler N, et al. Transition to adult services for young people with mental health needs: a systematic review. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2015;20:436–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Albert NM, Barnason S, Deswal A, et al. Transitions of care in heart failure: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circ Heart Fail. 2015;8:384–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rennke S, Ranji SR. Transitional care strategies from hospital to home: a review for the neurohospitalist. Neurohospitalist. 2015;5:35–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mitchell SE, Martin J, Holmes S, et al. How hospitals reengineer their discharge processes to reduce readmissions. J Healthc Qual. 2016;38:116–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Virapongse A, Misky GJ. Self-identified social determinants of health during transitions of care in the medically underserved: a narrative review. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33:1959–1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health, and cost. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27:759–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP); 2020. Available at: www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/Readmissions-Reduction-Program. Accessed June 5, 2020.

- 24. Allen J, Hutchinson AM, Brown R, et al. Quality care outcomes following transitional care interventions for older people from hospital to home: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Verhaegh KJ, MacNeil-Vroomen JL, Eslami S, et al. Transitional care interventions prevent hospital readmissions for adults with chronic illnesses. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33:1531–1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bray-Hall ST. Transitional care: focusing on patient-centered outcomes and simplicity. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157:448–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Forsythe LP, Carman KL, Szydlowski V, et al. Patient engagement in research: early findings from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. Health Aff. 2019;38:359–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. van Melle MA, van Stel HF, Poldervaart JM, et al. Measurement tools and outcome measures used in transitional patient safety; a systematic review. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0197312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Frank L, Basch E, Selby JV. The PCORI perspective on patient-centered outcomes research. JAMA. 2014;312:1513–1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Snyder CF, Jensen RE, Segal JB, et al. Patient-reported outcomes (PROs): putting the patient perspective in patient-centered outcomes research. Med Care. 2013;51(suppl 3):S73–S79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Borden WB, Chiang Y-P, Kronick R. Bringing patient-centered outcomes research to life. Value Health. 2015;18:355–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Feltner C, Jones CD, Cené CW, et al. Transitional care interventions to prevent readmissions for persons with heart failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:774–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Liss DT, Ackermann RT, Cooper A, et al. Effects of a transitional care practice for a vulnerable population: a pragmatic, randomized comparative effectiveness trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34:1758–1765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Naylor MD, Hirschman KB, O’Connor M, et al. Engaging older adults in their transitional care: what more needs to be done? J Comp Eff Res. 2013;2:457–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Prvu Bettger J, Alexander KP, Dolor RJ, et al. Transitional care after hospitalization for acute stroke or myocardial infarction. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157:407–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Van Spall HGC, Rahman T, Mytton O, et al. Comparative effectiveness of transitional care services in patients discharged from the hospital with heart failure: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Eur J Heart Fail. 2017;19:1427–1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI). About us, our vision and mission; 2020. Available at: www.pcori.org/about-us. Accessed July 8, 2020.

- 38. Reeves MJ, Fritz MC, Woodward AT, et al. Michigan Stroke Transitions Trial. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2019;12:e005493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gassaway J, Jones ML, Sweatman WM, et al. Effects of peer mentoring on self-efficacy and hospital readmission after inpatient rehabilitation of individuals with spinal cord injury: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;98:1526.e2–1534.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Zatzick D, Russo J, Thomas P, et al. Patient-centered care transitions after injury hospitalization: a comparative effectiveness trial. Psychiatry. 2018;81:141–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Velligan DI, Fredrick MM, Sierra C, et al. Engagement-focused care during transitions from inpatient and emergency psychiatric facilities. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2017;11:919–928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI). PCORI Methodology Standards; 2015. Available at: www.pcori.org/research-results/about-our-research/research-methodology/pcori-methodology-standards. Accessed July 8, 2020.

- 43. Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI). Engagement Rubric; 2017. Available at: www.pcori.org/document/engagement-rubric. Accessed July 8, 2020.

- 44. Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI). Transitional Care: The Network; 2020. Available at: www.pcori.org/topics/transitional-care/network. Accessed July 8, 2020.

- 45. Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI). Patient Engagement in Transitional Care; 2017. Available at: www.pcori.org/topics/transitional-care/patient-engagement-transitional-care. Accessed July 8, 2020.

- 46. Reeves MJ, Fritz MC, Osunkwo I, et al. Opening Pandora’s Box: from readmissions to transitional care patient-centered outcome measures. Med Care. 2021;59(suppl 4):S336–S343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Gesel SB, Prvu Bettger J, Lawrence RH, et al. Implementation of complex interventions: lessons learned from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute Transitional Care Portfolio. Med Care. 2021;59(suppl 4):S344–S354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Psioda MA, Jones SB, Xenakis JG, et al. Methodological challenges and statistical approaches in the COMprehensive Post-Acute Stroke Services Study. Med Care. 2021;59(suppl 4):S355–S363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sauers-Ford H, Statile AM, Auger KA, et al. Short-term focused feedback: a model to enhance patient engagement in research and intervention delivery. Med Care. 2021;59(suppl 4):S364–S370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. de Forcrand C, Flannery M, Cho J, et al. Pragmatic considerations in incorporating stakeholder engagement into a palliative care transitions study. Med Care. 2021;59(suppl 4):S371–S378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Zatzick D, Moloney K, Palinkas L, et al. Catalyzing the translation of patient-centered research into United States Trauma Care Systems: a case example. Med Care. 2021;59(suppl 4):S379–S386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Zwart DLM, Schnipper JL, Vermond D, et al. How do care transitions work? Unraveling the working mechanisms of care transition interventions. Med Care. 2021;59(suppl 4):S387–S397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]