Abstract

BACKGROUND/OBJECTIVES:

The number of older adults with complex health needs is growing, and this population experiences disproportionate morbidity and mortality. Interventions led by community health workers (CHWs) can improve clinical outcomes in the general adult population with multimorbidity, but few studies have investigated CHW-delivered interventions in older adults.

DESIGN:

We systematically reviewed the impact of CHW interventions on health outcomes among older adults with complex health needs. We searched for English-language articles from database inception through April 2020 using seven databases. PROSPERO protocol registration CRD42019118761.

SETTING:

Any U.S. or international setting, including clinical and community-based settings.

PARTICIPANTS:

Older adults 60 years of age or older with complex health needs, defined in this review as multimorbidity, frailty, disability, or high-utilization.

INTERVENTIONS:

Interventions led by a CHW or similar role consistent with the American Public Health Association’s definition of CHWs.

MEASUREMENTS:

Pre-defined health outcomes (chronic disease measures, general health measures, treatment adherence, quality of life, or functional measures) as well as qualitative findings.

RESULTS:

Of 5,671 unique records, nine studies met eligibility criteria, including four randomized controlled trials, three quasi-experimental studies, and two qualitative studies. Target population and intervention characteristics were variable, and studies were generally of low-to-moderate methodological quality. Outcomes included mood, functional status and disability, social support, well-being and quality of life, medication knowledge, and certain health conditions (e.g., falls, cognition). Results were mixed with several studies demonstrating significant effects on mood and function, including one high-quality RCT, while others noted no significant intervention effects on outcomes.

CONCLUSION:

CHW-led interventions may have benefit for older adults with complex health needs, but additional high-quality studies are needed to definitively determine the effectiveness of CHW interventions in this population. Integration of CHWs into geriatric clinical settings may be a strategy to deliver evidence-based interventions and improve clinical outcomes in complex older adults.

Keywords: older adults, community health workers, complex health needs

INTRODUCTION

The U.S. population aged 65 and older is projected to reach 80 million by 2040, more than double the older adult population in 2000.1 In a recent Commonwealth Fund study, 36% of U.S. older adults had three or more chronic conditions and 43% were considered high-need, defined as having multiple chronic conditions or a functional limitation.2 High-need older adults with multimorbidity and those who are frail, disabled, or high-utilizers of health care comprise a complex older adult population at increased risk of adverse health outcomes, including hospitalization, loss of independence, and mortality3–12 as well as disproportionate socioeconomic strain, mental health needs, and social isolation.2

There is a shortage of healthcare workers with geriatrics training to support the expanding older adult population, particularly in rural and underserved communities where socioeconomic conditions further contribute to complexity.2,13 Community health workers (CHWs) offer one potential strategy to increase delivery of evidence-based interventions and prevent poor health outcomes among vulnerable older adults. The American Public Health Association (APHA) defines CHWs as “frontline public health workers who are trusted members of and/or have an unusually close understanding of the community served.14” CHWs provide a range of services including health education, health coaching, and support accessing community resources.14–16 Studies have shown that CHW-led interventions can improve chronic disease, mental health, and maternal and child health outcomes in a variety of settings, often in underserved or low-resource communities.16–21

Large RCTs have demonstrated the effectiveness of CHW interventions on health outcomes and utilization in the general adult population with multimorbidity.22–24 However, fewer studies have examined the effectiveness of CHW interventions for older adults, particularly those with complex health needs. A 2014 systematic review investigated the impact of CHW interventions on health outcomes in older adults from ethnic minorities, noting potential improvements in access to care, health behaviors (physical activity, diet), and health outcomes (reduction in blood pressure).25 However, most eligible studies had a mean participant age under 60 years, and the review did not focus specifically on complex conditions. To better understand the impact of CHW interventions on health outcomes in complex older adults, we conducted a systematic review of CHW-led interventions in adults aged 60 and older with complex health needs, which we defined as multimorbidity, frailty, disability, or high-utilization.

METHODS

Methods were guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (see Appendix S1 for checklist).26 A team of clinician-researchers, librarians, and research staff with public health training collaborated on the design of this review. Our protocol is registered through the PROSPERO International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (CRD42019118761).27

Search Strategy

Reference librarians (HBB, PJB) conducted searches for English-language studies from date of inception to current through MEDLINE (Ovid), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (Wiley), Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Wiley), CINAHL (EBSCO), Web of Science (Clarivate Analytics), American Psychological Association PsycINFO (EBSCO), and Global Index Medicus (WHO). Searches were originally conducted on December 21, 2018 and updated on April 23, 2020.

We searched for articles containing terms related to CHWs, older adults, and complex health needs using subject headings and keywords which were adjusted for each database (Appendix S2). Search terms for CHWs were kept broad given the variability in titles used to describe this type of interventionist, and were based on search strategies used in previous systematic reviews of CHW interventions.16,17, 25,28–32 For complex health needs, we searched for terms related to multimorbidity, frailty, disability, and high-utilization as four broad, often overlapping categories associated with complex needs and adverse outcomes in older adults.2–12

Selection Criteria

Selection criteria were defined within the Participants, Interventions, Comparison, Outcomes, and Study Design (PICOS) framework. Only English-language, peer-reviewed original research studies were included. Studies were included if all participants were ≥60 years of age, or if a sub-group analysis of those ≥60 was reported. Studies in any setting (clinical or community-based, U.S. or international) were included.

We included studies in which participants were described as having complex conditions falling within the four categories of multimorbidity, frailty, disability, or high-utilization. We aimed to provide an overview of existing literature on CHW interventions for complex older adults and expected a small number of eligible studies based on our knowledge of the topic. Thus, we did not define specific criteria (e.g., use of standardized instruments) for the four complexity categories. Rather, we looked for author use of terms related to the four categories as defined in our search strategy (Appendix S2), and extracted each study’s description of the complex target population (Table 1).

Table 1.

Study Characteristics

| Citation | Design | N | Setting | Complex Health Need |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alegría, 201937 | RCT | I: 153 C: 154 |

MA, NY, FL, Puerto Rico (Community) | Disability: Depression or anxiety plus minor-moderate disability (SPPB) |

| Dye, 201838 | Quasi-exp | I: 33 C: 36 |

Rural Oconee County, SC (Community) | High-utilization: High ED-utilizing county; multiple chronic conditions in most participants |

| Geffen, 201939 | Quasi-exp (+ qual) | 212 | Peri-urban suburb, South Africa (Community) | Multimorbidity: At least 2 listed physical or psychosocial conditions |

| Lawn, 201740 | Qual | 10 older adults 24 support workers 8 coordinators |

Metro and rural South Australia (Community) | High-utilization: Frequent users of hospital/acute care due to comorbidities, psychosocial complexities |

| Li, 201941 | Qual (within parent RCT) | 16 village doctors 16 aging workers 6 psychiatrists |

Rural China (PC) | Multimorbidity: Comorbid hypertension and depression |

| Panagioti, 201842 | RCT (Trial w/in Cohort) | I: 504a C: 802 |

Northwest England (Community; PC recruitment) | Multimorbidity: At least 2 self-reported long-term conditions |

| Russell, 201743,b | Quasi-exp (+ qual) | 34 older adults 23 HHAs |

Urban NY (Community) | Frailty: Dual Medicare and Medicaid recipients (described as frail) |

| Walters, 201744 | Pilot RCT (+ qual) | I: 26 C: 25 |

Urban, semi-rural UK (Community; PC recruitment) | Frailty: Mild frailty (Rockwood Clinical Frailty Scale) |

| Wang, 201345 | Pilot RCT | I: 30 C: 32 |

Rural Taiwan (Community; PC recruitment) | Multimorbidity: At least 2 chronic illnesses |

Abbreviations: C, control; ED, emergency department; HHA, home health aide; I, intervention; PC, primary care; Qual, qualitative; Quasi-exp, quasi-experimental; RCT, randomized controlled trial; SPPB, Short Physical Performance Battery.

In this Trials within Cohorts design, 504 participants were randomized to the treatment group, but only 207 consented to the intervention.

Only 1 of the 2 described interventions in this article met criteria for this systematic review.

We included studies of interventions delivered by CHWs or similar interventionists whose described roles were consistent with the APHA’s definition of a CHW (Appendix S3).14 Team-based or multicomponent interventions involving non-CHW personnel were included if CHWs played a primary role in the delivery of the intervention, and we documented roles played by other personnel during data extraction (Supplementary Table S1).

For quantitative studies, we included randomized controlled trials and quasi-experimental designs with at least one pre-defined health outcome, including chronic disease measures, general health measures, treatment adherence, quality of life, or functional measures. Studies without one of these pre-defined health outcomes were excluded; however, we also extracted outcomes for cost, utilization, feasibility, quality, and satisfaction if reported.

Given the limited literature base and preliminary nature of many community intervention studies, we also included articles reporting qualitative findings from CHW intervention studies to better understand the feasibility and acceptability of these interventions. We included purely qualitative studies and multi-method studies that reported qualitative findings. Selection criteria for qualitative studies were the same as for quantitative studies with the exception of the following: 1) permitted age <60 years for CHWs/team members who participated as interviewees (though still required the intervention target population to be ≥60 years); and 2) did not require use of one of the pre-defined quantitative health outcomes.

Study Selection

The primary review team (MAK, SMK, PRD, KEH) test-screened 200 titles and abstracts to confirm >80% concordance using the defined selection criteria, as done in our previous work.33 Three reviewers (SMK, PRD, KEH) then independently screened titles and abstracts in duplicate and excluded those that clearly did not meet eligibility criteria. A third reviewer (MAK) resolved discrepancies between the pairs for the original search. For the search update in April 2020, two reviewers (MAK, KEH) independently screened titles and abstracts and discrepancies were resolved through consensus discussion.

Two reviewers (MAK, KEH) reviewed all eligible full texts independently to determine final inclusion. Discrepancies in inclusion decisions were resolved through consensus discussion involving a third reviewer (PRD), who also adjudicated discrepancies in reason for exclusion. We contacted study authors by email for clarifying information to determine final inclusion when needed; we received responses to 5 out of 6 inquiries, and excluded the sixth article based on the content available in the article. Finally, two reviewers (MAK, KEH) reviewed reference lists of included studies to identify additional articles; we screened relevant titles/abstracts in duplicate followed by full text review if preliminarily eligible, and resolved discrepancies through consensus discussion.

Data Extraction

Study data were extracted independently by two researchers (MAK, KEH) using a standardized collection table, including study and participant characteristics, criteria for complex health needs, intervention characteristics, CHW elements (e.g. title, role, training), primary and secondary quantitative outcomes, and qualitative findings. Certain data elements (e.g. quantitative outcomes) were not relevant for purely qualitative studies and therefore were not extracted for those studies. A priori, we anticipated few eligible studies and significant heterogeneity in study participants, interventions, and outcomes. Therefore, we did not conduct a quantitative synthesis of results, but included a narrative assessment of our findings.

Assessment of Quality

Two independent reviewers (KEH, MAK) assessed methodological quality using the following tools as appropriate for study design: the Revised Cochrane Risk-of-Bias (RoB 2) Tool for Randomized Trials for RCTs34; the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Quality Appraisal Checklist for qualitative studies35; and the Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies for quasi-experimental studies.36 For multi-method studies reporting both quantitative and qualitative findings, we used the RoB 2 or EPHPP tool for the quantitative component and the NICE tool for the qualitative component. We resolved discrepancies in quality ratings through consensus discussion. Studies were not excluded based on methodological quality.

RESULTS

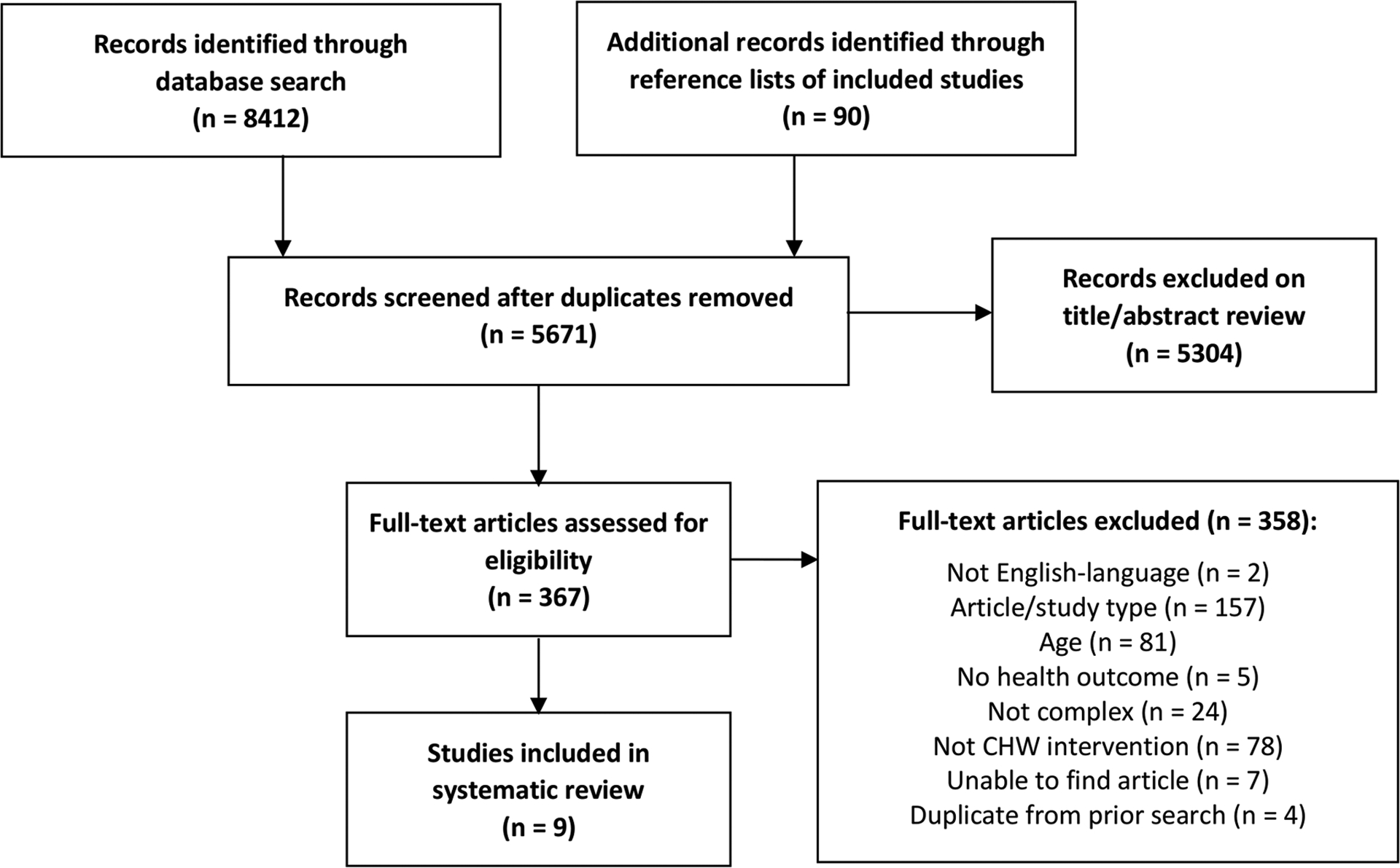

Search results are presented in a PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1).26 The database search and review of reference lists resulted in 5,671 records after duplicates were removed. Of those, 5,304 records were excluded on title and abstract screening. We reviewed 367 full texts and nine studies met final criteria for inclusion.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram for identification and selection of included studies.26

Study Characteristics

Study characteristics are outlined in Table 1. The nine included studies were published between 2013 and 2019.37–45 Two studies were large RCTs (one conducted as a Trials within Cohorts design),37,42 two were pilot RCTs,44,45 three were quasi-experimental (one with comparison group38 and two pre-post designs39,43), and two were qualitative.40,41 One pilot RCT44 and two quasi-experimental studies39,43 additionally reported qualitative findings. Study setting included both rural and urban locations in the U.S. and internationally. Three studies were conducted in the U.S.,37,38,43 two were in the United Kingdom,42,44 and one each were conducted in Taiwan,45 China,41 South Africa,39 and Australia.40 Interventions were generally community-based (several with recruitment through primary care), but one was primary care-based.41

Participants and Complex Conditions

Mean age of participants ranged from 69–80 years and the majority were female. Race and ethnicity were inconsistently reported (five of nine studies) and composition varied (Table 2). The target population of older adults with complex conditions was variable across studies (Table 1). Four studies recruited participants based on multimorbidity,39, 41,42,45 two targeted high-utilizing populations,38,40 two addressed frail older adults,43,44 and one focused on disability.37 Participants in most studies had multiple chronic conditions, regardless of the specific eligibility criteria. Health conditions targeted in the studies were typically nonspecific, but three studies focused on specific conditions: depression or anxiety (plus disability),37 depression plus hypertension,41 and cardiovascular disease, hypertension, or congestive heart failure.38 Although two studies targeted a frail population, only one used a standardized measure for frailty to determine eligibility.44

Table 2.

Participant Characteristics

| Citation | Age | % Female | Race/Ethnicity | % Living Alone |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alegría, 201937 | Mean NR I: 5.9% 60–64, 45.8% 65–74, 48.4% 75+ C: 7.8% 60–64, 40.9% 65–74, 51.3% 75+ |

80.8% | 44.9% Hispanic 33.7% Asian 10.2% White 7.9% Black 3.0% Other 0.3% American Indian |

NR |

| Dye, 201838 | Mean NR I: range 61–96 C: range 61–91 |

58.8% (13.2% NR) |

80.9% White 13.2% NR 2.9% Black 2.9% Hispanic |

NR |

| Geffen, 201939 | Mean 69 (sd NR) | 75% | NR | 7% |

| Lawn, 201740 | Mean NR Range 66–97 |

100% | NR | 50% |

| Li, 201941 | N/Aa | N/Aa | N/Aa | N/Aa |

| Panagioti, 201842 | I: 75.4 ± 6.8 C: 74.2 ± 6.4 |

54.4% | 97.6% White 1.8% Non-white |

36.5% |

| Russell, 201743,b | 80.5 ± 7.7 | 73.5% | 50.0% Black 26.5% Other/ Unknown 11.8% White 11.8% Hispanic |

79.4% |

| Walters, 201744 | I: 80.4 ± 6.9 C: 79.7 ± 6.4 |

58.8% | 88.2% White British 7.8% Other White 2.0% African 2.0% Other Asian |

51% |

| Wang, 201345 | I: 70.0 ± 8.8 C: 72.6 ± 6.7 |

54.8% | NR | 35.5% |

Abbreviations: C, control; I, intervention; NR, not reported.

Age, sex, race/ethnicity and living alone are reported for older adult study participants only (not reported for non-older adult interviewees in qualitative studies).

Only 1 of the 2 described interventions in this article met criteria for this systematic review.

Interventions

Interventions varied in content, goal, intensity, and mode of delivery (Table 3, Supplementary Table S1). All interventions incorporated a psychosocial or behavioral approach (e.g. goal-setting, behavior change, emotional/social support, self-management). Two involved physical activity (structured group exercise or home exercise) in addition to a psychosocial or behavior change component.37,44 Two studies were workforce enhancement interventions that trained home support workers in self-management skills for integration into their routine home health care.40,43 There were two health coaching interventions,38,42 one primary care collaborative care team model,41 one peer support program,39 and one medication adherence intervention.45

Table 3.

Intervention Characteristics

| Citation | Intervention Type | Goal | Duration | CHW Title and Selection |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alegría, 201937 | Psychosocial + group exercise | Prevent disability in minority and immigrant older adults w/ mood symptoms and impaired function | 6 mos |

CHW Recruited in collaboration with community site leaders |

| Dye, 201838 | Health coaching | Decrease readmissions and ED use in rural older adults w/ chronic disease post- HHS discharge | 4 mos |

Health Coach Member of the community, evaluated through interview, recruited by coordinator |

| Geffen, 201939 | Peer support | Improve wellbeing among low-income older adults | 5 mos |

AgeWell Visitor Older adult living in the community, interview and selection process |

| Lawn, 201740 | Workforce enhancement | Enhance capacity of support workers in complexity and self-management | N/A (routine HHS) |

Support

Worker Employed as home support worker for older adults |

| Li, 201941 | Collaborative care | Treat comorbid depression and HTN in rural older adults | 12 mos |

Aging Worker Employed in village education/ liaison role; local residents who know villagers well |

| Panagioti, 201842 | Health coaching | Increase self-management and quality of life in older adults w/ multi-morbidity | 6 mos |

Health Advisor Skills in technology, communication, working with public, DM coaching, social prescribing |

| Russell, 201743,a | Workforce enhancement, health coaching | Prepare HHAs to integrate health coaching into care for chronically ill older adults to improve self-management | N/A (routine HHS) |

Health Coach HHA with ≥1yr experience at partner agency and positive evaluations; close relationship between HHAs and community |

| Walters, 201744 | Behavior change | Improve clinical outcomes (e.g. functioning) in older adults w/ mild frailty | 6 mos |

HomeHealth Project

Worker Non-specialist w/skills in communication, working with older people, engagement, person-centered planning |

| Wang, 201345 | Medication adherence | Improve medication safety in rural older adults w/ chronic illnesses | 2 mos |

Volunteer

Coach Recommended by community leader or clinic, lived in the community, high school ed, volunteer experience and certification |

Additional intervention details are available in Supplementary Table S1.

Abbreviations: DM, diabetes mellitus; ED, emergency department; ed, education; HHA, home health aide; HHS, home health services; HTN, hypertension; mo(s), month(s).

Only 1 of the 2 described interventions in this article met criteria for this systematic review.

Intervention duration ranged from 2–12 months (median 5 months) for the seven studies with a defined intervention period. Six studies were primarily home-based, often including additional telephone follow-up.38–40,43–45 One health coaching intervention was completely phone-based.42 One study incorporated both an individual home, community, or phone-based psychosocial intervention and a group exercise component,37 and one involved home visits in addition to primary care visits.41

CHW Role

CHW roles in intervention delivery are outlined in Table 3 and Supplementary Table S1. Only one study used the term “Community Health Worker” for the interventionist.37 Additional terms included “Health Coach” (n=2), “AgeWell Visitor,” “Support Worker,” “Aging Worker,” “Health Advisor,” “HomeHealth Project Worker,” and “Volunteer Coach.” Most studies recruited interventionists who were from the local community they were serving, had experience similar to their role in the study, and had been recommended by community leaders. None indicated that they required a specific level of education. Two studies trained existing home health workers40,43 and one study recruited older adults to serve as peer interventionists.39

All studies reported training protocols for the interventionists (Supplementary Table S1). Training ranged from 2 days to 4 months, with content focused on key concepts and intervention components. Only three studies noted end-of-training tests or fidelity thresholds.37,38,45 Seven studies reported some form of supervision for the CHW, ranging from formal supervision with audio-recorded sessions to informal as-needed communication with supervisors.

Eight studies involved other personnel in intervention delivery in addition to CHWs (Supplementary Table S1). Two of these studies involved other interventionists providing direct services to participants, including one multicomponent intervention delivered partially by a CHW and partially by an exercise trainer,37 and one collaborative care intervention that involved a CHW (“Aging Worker”) working in collaboration with a village doctor and consulting psychiatrist.41 Six studies had additional team members serving an indirect role in the intervention, including CHW supervision and support or initial participant evaluation.38–40,42–44

Quantitative Health Outcomes

Health outcome measures and results are presented in Table 4 and Supplementary Table S2. Commonly assessed outcomes included self-reported mood (n=4), self-reported functioning/disability and physical performance (n=2), quality of life or well-being (n=4), and self-care (n=2). Two RCTs that combined a psychosocial/behavioral change intervention with exercise showed improved mood, self-reported functioning or disability, and physical measures compared to control.37,44 A large quasi-experimental peer support study demonstrated improvements in well-being, mood, social support and activity, and physical activity.39 A home health aide health coaching intervention improved self-reported general health and self-care maintenance,43 and a medication safety intervention showed improvements in medication safety knowledge and behaviors, but not attitudes, compared to baseline.45 Most other studied outcomes had no significant effects or were not tested for statistical significance. Standardized effect sizes generally were not reported, but one study did report small intent-to-treat effects (Cohen’s d) on measures of mood and function.37

Table 4.

Main Results

| Citation | Comparator | Main Findings | Quality/ROBa |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alegría, 201937 | UC + assessment, written ed | Quan: ↓depressive symptoms, ↑functional performance, ↓disability; no effect on anxiety | ROB low (Cochrane) |

| Dye, 201838 | Matched | Quan: ↓ ED/hospital admissions (no test of significance) | Weak (EPHPP) |

| Geffen, 201939 | Baseline | Quan: ↑ well-being, social support, activity participation, social interaction, physical activity; ↓ mood symptoms, loneliness; no change in falls | Moderate (EPHPP) |

| Qual: increased connection, skills, benefits to self and family for AgeWell Visitors | − (NICE) | ||

| Lawn, 201740 | N/A | Qual: more collaborative relationship between clients and support workers; shift in role towards behavior change and risk identification; increased skills | + (NICE) |

| Li, 201941 | N/A | Qual: team model and support of leaders key to success; increased knowledge of village doctors and aging workers; existing relationship supported collaboration; improved mood/health in patients | + (NICE) |

| Panagioti, 201842 | UC | Quan: No effect on self-management, quality of life, depression, self-care | ROB high (Cochrane) |

| Russell, 201743,b | Baseline | Quan: ↑ quality of life (visual analogue scale only) and self-care; no change in overall quality of life | Weak (EPHPP) |

| Qual: positive opportunity and impact for home health aides; facilitated relationship with clients | + (NICE) | ||

| Walters, 201744 | UC + written ed | Quan: ↑ functioning, ↓ psych distress, ↑ grip strength; no effect on well-being, frailty characteristics, substance use, cognition, falls, quality of life | ROB some concerns (Cochrane) |

| Qual: Health needs motivated participants, satisfied with intervention; project workers gained confidence in role over time; behavioral change approach did not suit all participants | ++ (NICE) | ||

| Wang, 201345 | UC | Quan: ↑ medical knowledge and 3/6 behaviors; no effect on attitude | Moderate (EPHPP) |

Additional outcome details are available in Supplementary Tables S2–S3.

Abbreviations: ED, emergency department; qual, qualitative; quan, quantitative; ROB, risk bias; UC, usual care.

The Revised Cochrane Risk-of-Bias (RoB 2) Tool for Randomized Trials34 was used for RCTs, the Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies36 was used for quasi-experimental studies, and The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Quality Appraisal Checklist35 was used for qualitative studies.

Only 1 of the 2 described interventions in this article met criteria for this systematic review.

Qualitative Findings

Five studies included qualitative findings, either alone or in addition to quantitative outcomes (Table 4 and Supplementary Table S3).39–41,43,44 All included interviews or focus groups with interventionists, and two also interviewed older adult participants.40,44 In general, studies demonstrated feasibility and acceptability of the intervention, positive experiences among interventionists who found their role was beneficial and fulfilling, and satisfaction among older adults with the intervention and interactions with CHWs.

Quality Assessment

Studies were generally of low-to-moderate methodological quality. Only one high-quality RCT with low risk of bias was identified using the Revised Cochrane Risk-of-Bias Tool for Randomized Trials,37 and only one study with a qualitative component received the highest quality rating using the NICE Quality Appraisal Checklist44 (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

This systematic review identified nine eligible studies of CHW-led interventions for older adults with complex health needs, of which three were conducted in the U.S. Eligible studies were all published within the past 7 years, including three since 2019. This recent increase in relevant publications suggests that CHW-led interventions may be an underutilized, but growing, resource for older adults with complex health needs.

While implementation of CHW-delivered interventions for this population was considered feasible across urban and rural study settings in six countries, the methodological quality was generally low-to-moderate. The single high-quality RCT in this review by Alegría and colleagues investigated a CHW-delivered cognitive-behavioral therapy-based psychosocial intervention in combination with an exercise trainer-led group exercise program for older adults with mood symptoms and minor-to-moderate disability, which had significant effects on mood (Hopkins Symptom Checklist, HSCL-25) and function (Short Physical Performance Battery, SPPB and Late-Life Function and Disability Instrument, LLFDI).37 A pilot RCT conducted by Walters and colleagues similarly investigated a home-based behavioral change intervention that incorporated home exercise for older adults with mild frailty and demonstrated improvement in mood (General Health Questionnaire, GHQ-12) and function (Modified Barthel Index and grip strength), as well as participant satisfaction as evident from qualitative evaluation.44

These studies suggest that CHW-led multicomponent interventions for older adults with early disability and frailty have the potential to improve mood and functional outcomes, which is consistent with WHO Integrated Care for Older People (ICOPE) guidelines for supporting functional capacity in older adults through an integrated, multicomponent approach.46,47 However, additional studies with larger sample sizes and rigorous quantitative and qualitative methodology are needed to confirm health outcome findings and further explore the experience and perceived benefit of older adult participants and CHWs involved in these programs. Future work is also needed to determine whether certain clinical or sociodemographic characteristics predict benefit from these interventions, which components of complex multicomponent interventions are critical for effectiveness, and how variations in CHW and delivery characteristics impact outcomes.

This review has several limitations. We used broad search terms to capture all interventionists whose roles may be in line with the APHA definition of CHWs; however, we may have missed some relevant studies given the variation in name, training, and role of this workforce.30 We did screen 90 additional studies identified through the reference lists of included articles, none of which met eligibility criteria. Publication bias should also be considered, as we only included intervention studies in peer-reviewed journals; a search including unpublished or grey literature may have identified additional relevant studies. We also chose to include two studies in which existing home health aides or support workers received additional self-management and behavioral change training consistent with a CHW role, which may have increased the heterogeneity of the interventionists in our included studies. We chose to include studies outside the U.S. given the long history of CHW interventions in low- and middle-income countries which have informed the development of CHW programs in the U.S.,48 but the variability in geographic, policy, and economic contexts across these settings further increases the heterogeneity of included studies.

By limiting our definition of complex health needs to multimorbidity, frailty, disability, and high-utilization, our review may have excluded relevant studies of other complex conditions such as dementia, serious mental illness, malignancy, or poorly controlled chronic diseases such as diabetes. Dementia warrants particular consideration, given its significant association with disability, decline, and mortality in older adults.49 While none of the eligible studies in this review focused on dementia, this population may benefit from CHW interventions. For example, the Aging Brain Care model has shown that collaborative care incorporating lay interventionists (“care coordinator assistants”) may improve clinical outcomes in older adults with dementia.50 Our search strategy also identified several relevant studies that were excluded based on age during screening (due to participants under age 60), including the LifeCourse model, which incorporates lay “care guides” to improve quality of life in seriously ill older adults,51 and the IMPaCT CHW model, which has demonstrated improved health outcomes in adults with multimorbidity.22,23 Our review did include several studies with socially vulnerable participants, but this was not specified in our eligibility criteria for complexity. As U.S. older adults with complex health needs experience high rates of socioeconomic strain and isolation,2 there is a need to further investigate the potential impact of CHW interventions on socially vulnerable older adults, particularly given the well-suited skills and training of CHWs to serve populations with high social needs.16,52

We employed broad criteria for four categories of complexity to capture the existing literature on older adult CHW interventions and to identify gaps for future work. While they share underlying risk for decline and loss of independence over time, these high-need older patient populations are inherently heterogeneous, and typically lack standardized definitions.53,54 Only two studies in this review used validated instruments for disability and frailty to determine study eligibility.37,44 Variable definitions for multimorbidity, frailty, disability, and high utilization across studies limits the validity and reliability of our findings. At the same time, this may also increase the generalizability to clinical and community care settings where complex needs are often ill-defined. Future work should focus on the use of pragmatic clinical tools (e.g., measures of comorbidity, frailty, function, or vulnerability) to systematically identify at-risk older adults who may benefit from CHW interventions.

Identifying evidence-based interventions to prevent and manage complex conditions in older adults has important clinical and public health implications. This patient population has diverse, costly, and time-intensive needs, and those who are homebound and most vulnerable may be challenging to identify and manage in typical clinic-based settings.2,55,56 Though the impact of comprehensive care management in medically complex adults remains unclear,57,58 innovative multicomponent interventions and team and home-based care models in older adults with complex conditions are promising.37,44,55,59 Studies have demonstrated that CHWs linked to primary care settings can positively impact health-related outcomes in medically and socially complex general adult populations.22,23 Our review suggests that CHW interventions may also benefit older adults with complex needs; should further work demonstrate effectiveness, integration of CHWs into geriatric primary care and consultative clinical settings may improve outcomes in this population. However, sustainable, large-scale dissemination of such programs would necessitate policy reform including payer reimbursement for CHW services, which to date is not widely established in the U.S.60

In summary, there is a limited body of evidence demonstrating impact of CHW-led interventions for older adults with complex conditions. One high-quality RCT and several moderate-quality studies in this review show promise for interventions led by this workforce, particularly the potential impact of multicomponent psychosocial and exercise interventions on mood and function in older adults with disability or frailty. There is a need for additional high-quality studies to understand the impact, cost-effectiveness, and ideal implementation strategies for CHW-led interventions for older adults with complex needs. As the current population ages, the geriatric healthcare workforce will be further stretched. Effective, scalable interventions led by CHWs and other non-clinicians could play an important role in supporting functional independence and well-being among vulnerable older adults.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Appendix S1. PRISMA checklist.26

Supplementary Appendix S2. Complete search strategy.

Supplementary Appendix S3. APHA definition of CHW.14

Supplementary Table S1. Detailed Intervention Characteristics.

Supplementary Table S2. Detailed Quantitative Outcomes.

Supplementary Table S3. Detailed Qualitative Findings.

Key Points:

We conducted a systematic review of interventions led by community health workers (CHWs) for older adults with complex health needs, defined as multimorbidity, frailty, disability, and high-utilization.

There is limited published research on CHW interventions for older adults with complex health needs; nine studies of generally low-to-moderate methodological quality met eligibility criteria for this review.

One high-quality RCT and several moderate-quality studies suggest benefit, particularly for the impact of multicomponent CHW interventions on mood and functional outcomes.

Why Does this Paper Matter?

CHW-delivered interventions may improve health outcomes, particularly mood and function, in older adults with complex health needs.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Martha L. Bruce, PhD, MPH and Stephen J. Bartels, MD, MS for their expert mentorship throughout this project.

Financial Disclosures:

This work was supported in part by resources at the VA Bedford Healthcare System in Bedford, MA, the Health Resources and Services Administration (grant number T32HP30036), the National Institute on Aging (grant numbers K23AG043498 and K23AG051681), and the Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Research Center by cooperative agreement no. U48DP005018 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government, the Health Resources and Services Administration, the National Institutes of Health, or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Sponsor’s Role:

The sponsors had no role in the design or conduct of this study or in the preparation of this article.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest related to this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.2019 Profile of Older Americans. Administration for Community Living, Administration on Aging, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Washington, D.C.; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Osborn R, Doty MM, Moulds D, Sarnak DO, Shah A. Older Americans were sicker and faced more financial barriers to health care than counterparts in other countries. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(12):2123–2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nunes BP, Flores TR, Mielke GI, Thume E, Facchini LA. Multimorbidity and mortality in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2016;67:130–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chamberlain AM, Rutten LJF, Jacobson DJ, et al. Multimorbidity, functional limitations, and outcomes: interactions in a population-based cohort of older adults. J Comorb. 2019;9:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hanlon P, Nicholl BI, Jani BD, Lee D, McQueenie R, Mair FS. Frailty and pre-frailty in middle-aged and older adults and its association with multimorbidity and mortality: a prospective analysis of 493 737 UK Biobank participants. The Lancet Public Health. 2018;3(7):e323–e332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rizzuto D, Melis RJF, Angleman S, Qiu C, Marengoni A. Effect of chronic diseases and multimorbidity on survival and functioning in elderly adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(5):1056–1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marengoni A, von Strauss E, Rizzuto D, Winblad B, Fratiglioni L. The impact of chronic multimorbidity and disability on functional decline and survival in elderly persons. A community-based, longitudinal study. J Intern Med. 2009;265(2):288–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Verghese J, Levalley A, Hall CB, Katz MJ, Ambrose AF, Lipton RB. Epidemiology of gait disorders in community-residing older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(2):255–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chyr LC, Drabo EF, Fabius CD. Patterns and predictors of transitions across residential care settings and nursing homes among community-dwelling older adults in the United States. Gerontologist. June 29 2020. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kojima G Frailty as a predictor of nursing home placement among community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2018;41(1):42–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bell J, Turbow S, George M, Ali MK. Factors associated with high-utilization in a safety net setting. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):273–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Geriatrics Society Expert Panel on the Care of Older Adults with Multimorbidity. Patient-centered care for older adults with multiple chronic conditions: a stepwise approach from the American Geriatrics Society. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(10):1957–1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Retooling for an aging America: building the health care workforce. Institute of Medicine, National Academy of Sciences. Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press; 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Support for Community Health Workers to Increase Health Access and to Reduce Health Inequities, Policy No. 20091 American Public Health Association (online). Available at: https://www.apha.org/policies-and-advocacy/public-health-policy-statements/policy-database/2014/07/09/14/19/support-for-community-health-workers-to-increase-health-access-and-to-reduce-health-inequities. Accessed October 26, 2020.

- 15.Hartzler AL, Tuzzio L, Hsu C, Wagner EH. Roles and functions of community health workers in primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2018;16(3):240–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim K, Choi JS, Choi E, et al. Effects of community-based health worker interventions to improve chronic disease management and care among vulnerable populations: a systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(4):e3–e28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Viswanathan M, Kraschnewski JL, Nishikawa B, et al. Outcomes and costs of community health worker interventions: a systematic review. Med Care. 2010;48(9):792–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schroeder K, McCormick R, Perez A, Lipman TH. The role and impact of community health workers in childhood obesity interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2018;19(10):1371–1384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoeft TJ, Fortney JC, Patel V, Unützer J. Task-sharing approaches to improve mental health care in rural and other low-resource settings: a systematic review. J Rural Health. 2018;34(1):48–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mundorf C, Shankar A, Moran T, et al. Reducing the risk of postpartum depression in a low-income community through a community health worker intervention. Matern Child Health J. 2018;22(4):520–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brownstein JN, Chowdhury FM, Norris SL, et al. Effectiveness of community health workers in the care of people with hypertension. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(5):435–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kangovi S, Mitra N, Grande D, Huo H, Smith RA, Long JA. Community health worker support for disadvantaged patients with multiple chronic diseases: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(10):1660–1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kangovi S, Mitra N, Norton L, et al. Effect of community health worker support on clinical outcomes of low-income patients across primary care facilities: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(12):1635–1643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vasan A, Morgan JW, Mitra N, et al. Effects of a standardized community health worker intervention on hospitalization among disadvantaged patients with multiple chronic conditions: a pooled analysis of three clinical trials. Health Serv Res. 2020;55(Suppl 2):894–901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Verhagen I, Steunenberg B, de Wit N, Ros W. Community health worker interventions to improve access to health care services for older adults from ethnic minorities: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kennedy M, Kelly S, Dimilia P, Blunt H, Bagley P, Hatchell K. Community health worker-delivered interventions for older adults with complex health care needs: a systematic review (online). PROSPERO: International prospective register of systematic reviews CRD42019118761. Available at: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42019118761. Accessed October 26, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 28.The Community Guide. Cardiovascular Disease: Interventions Engaging Community Health Workers (online). Available at: https://www.thecommunityguide.org/findings/cardiovascular-disease-prevention-and-control-interventions-engaging-community-health. Accessed October 26, 2020.

- 29.Jack HE, Arabadjis SD, Sun L, Sullivan EE, Phillips RS. Impact of community health workers on use of healthcare services in the United States: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(3):325–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Olaniran A, Smith H, Unkels R, Bar-Zeev S, van den Broek N. Who is a community health worker? - a systematic review of definitions. Glob Health Action. 2017;10(1):1272223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Palmas W, March D, Darakjy S, et al. Community health worker interventions to improve glycemic control in people with diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(7):1004–1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wurzer BM, Hurkmans EJ, Waters DL. The use of peer-led community-based programs to promote healthy aging. Curr Geri Rep. 2017;6:202–211. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Batsis JA, DiMilia PR, Seo LM, et al. Effectiveness of ambulatory telemedicine care in older adults: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(8):1737–1749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sterne JAC, Savovic J, Page MJ, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Methods for the development of NICE public health guidance (third edition). National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (online). Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/process/pmg4/chapter/appendix-h-quality-appraisal-checklist-qualitative-studies. Accessed December 31, 2020. [PubMed]

- 36.Thomas BH, Ciliska D, Dobbins M, Micucci S. A process for systematically reviewing the literature: providing the research evidence for public health nursing interventions. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2004;1(3):176–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alegría M, Frontera W, Cruz-Gonzalez M, et al. Effectiveness of a disability preventive intervention for minority and immigrant elders: The Positive Minds-Strong Bodies Randomized Clinical Trial. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;27(12):1299–1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dye C, Willoughby D, Aybar-Damali B, Grady C, Oran R, Knudson A. Improving chronic disease self-management by older home health patients through community health coaching. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(4):660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Geffen LN, Kelly G, Morris JN, Howard EP. Peer-to-peer support model to improve quality of life among highly vulnerable, low-income older adults in Cape Town, South Africa. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19(1):279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lawn S, Westwood T, Jordans S, O’Connor J. Support workers as agents for health behavior change: an Australian study of the perceptions of clients with complex needs, support workers, and care coordinators. Gerontol Geriatr Educ. 2017;38(4):496–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li LW, Xue J, Conwell Y, Yang Q, Chen S. Implementing collaborative care for older people with comorbid hypertension and depression in rural China. Int Psychogeriatr. 2019:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Panagioti M, Reeves D, Meacock R, et al. Is telephone health coaching a useful population health strategy for supporting older people with multimorbidity? An evaluation of reach, effectiveness and cost-effectiveness using a ‘trial within a cohort’. BMC Med. 2018;16(1):80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Russell D, Mola A, Onorato N, et al. Preparing home health aides to serve as health coaches for home care patients with chronic illness: findings and lessons learned from a mixed-method evaluation of two pilot programs. Home Health Care Management & Practice. 2017;29(3):191–198. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Walters K, Frost R, Kharicha K, et al. Home-based health promotion for older people with mild frailty: the HomeHealth intervention development and feasibility RCT. Health Technol Assess. 2017;21(73):1–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang CJ, Fetzer SJ, Yang YC, Wang JJ. The impacts of using community health volunteers to coach medication safety behaviors among rural elders with chronic illnesses. Geriatr Nurs. 2013;34(2):138–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Integrated care for older people: guidelines on community-level interventions to manage declines in intrinsic capacity. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Integrated care for older people (ICOPE): guidance for person-centered assessment and pathways in primary care. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019. (WHO/FWC/ALC/19.1). Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Perry HB, Zulliger R, Rogers MM. Community health workers in low-, middle-, and high-income countries: an overview of their history, recent evolution, and current effectiveness. Annu Rev Public Health. 2014;35:399–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.2020 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2020. March 10. 10.1002/alz.12068 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.LaMantia MA, Alder CA, Callahan CM, et al. The Aging Brain Care Medical Home: Preliminary Data. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015;63(6):1209–1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shippee T, Shippee N, Fernstrom K, et al. Quality of Life for Late Life Patients: Mixed-Methods Evaluation of a Whole-Person Approach for Patients With Chronic Illnesses. J Appl Gerontol. 2019;38(7):910–930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rosenthal EL, Brownstein JN, Rush CH, et al. Community health workers: part of the solution. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(7):1338–1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Guiding principles for the care of older adults with multimorbidity: an approach for clinicians. American Geriatrics Society Expert Panel on the Care of Older Adults with Multimorbidity. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(10):E1–E25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Long P, Abrams M, Milstein A, et al. , eds. Effective Care for High-need Patients: Opportunities for Improving Outcomes, Value, and Health. Wahington, D.C.: National Academy of Medicine; 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Boult C, Wieland GD. Comprehensive primary care for older patients with multiple chronic conditions: “Nobody rushes you through”. JAMA. 2010;304(17):1936–1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Valluru G, Yudin J, Patterson CL, et al. Integrated home- and community-based services improve community survival among Independence at Home Medicare beneficiaries without increasing medicaid costs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(7):1495–1501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Finkelstein A, Zhou A, Taubman S, Doyle J. Health care hotspotting - a randomized, controlled trial. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(2):152–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zulman DM, Pal Chee C, Ezeji-Okoye SC, et al. Effect of an intensive outpatient program to augment primary care for high-need Veterans Affairs patients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(2):166–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Buhr G, Dixon C, Dillard J, et al. Geriatric resource teams: equipping primary care practices to meet the complex care needs of older adults. Geriatrics (Basel). 2019;4(4):59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lapidos A, Lapedis J, Heisler M. Realizing the value of community health workers - new opportunities for sustainable financing. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(21):1990–1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Appendix S1. PRISMA checklist.26

Supplementary Appendix S2. Complete search strategy.

Supplementary Appendix S3. APHA definition of CHW.14

Supplementary Table S1. Detailed Intervention Characteristics.

Supplementary Table S2. Detailed Quantitative Outcomes.

Supplementary Table S3. Detailed Qualitative Findings.