Abstract

Background

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a complex disease with variable presentation, progression, and response to therapies. Current disease classification is based on subjective clinical phenotypes. The peripheral blood immunophenome can reflect local inflammation, and thus we measured 39 circulating immune cell types in a large cohort of IBD and control subjects and performed immunotype:phenotype associations.

Methods

We performed fluorescence-activated cell sorting or CyTOF analysis on blood from 728 Crohn’s disease, 464 ulcerative colitis, and 334 non-IBD patients, with available demographics, endoscopic and clinical examinations and medication use.

Results

We observed few immune cell types commonly affected in IBD (lowered natural killer cells, B cells, and CD45RA– CD8 T cells). Generally, the immunophenome was distinct between ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Within disease subtype, there were further distinctions, with specific immune cell types associating with disease duration, behavior, and location. Thiopurine monotherapy altered abundance of many cell types, often in the same direction as disease association, while anti-tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) monotherapy demonstrated an opposing pattern. Concomitant use of an anti-TNF and thiopurine was not synergistic, but rather was additive. For example, thiopurine monotherapy use alone or in combination with anti-TNF was associated with a dramatic reduction in major subclasses of B cells.

Conclusions

We present a peripheral map of immune cell changes in IBD related to disease entity and therapies as a resource for hypothesis generation. We propose the changes in B cell subsets could affect antibody formation and potentially explain the mechanism behind the superiority of combination therapy through the impact of thiopurines on pharmacokinetics of anti-TNFs.

Keywords: Immunophenotype, FACS, CyTOF, Anti-TNF, Thiopurine

Abbreviations used in this paper: ADA, anti-drug antibody; AUC, area under the curve; AZA, azathioprine; CBC, cell blood count; CD, Crohn’s disease; DC, dendritic cell; EM, effector memory; FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorting; FDR, false discovery rate; HBI, Harvey-Bradshaw Index; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; MayoEndo, Mayo Endoscopic Score; MSCCR, Mount Sinai Crohn’s and Colitis Registry; NK, natural killer; NLR, neutrophil-to-leukocyte ratio; PCA, principal component analysis; SCCAI, Simple Clinical Colitis Activity Index; SES-CD, Simple Endoscopic Score for Crohn’s Disease; Th, helper T cell; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; Treg, regulatory T cell; UC, ulcerative colitis; UCEIS, Ulcerative Colitis Endoscopic Index of Severity

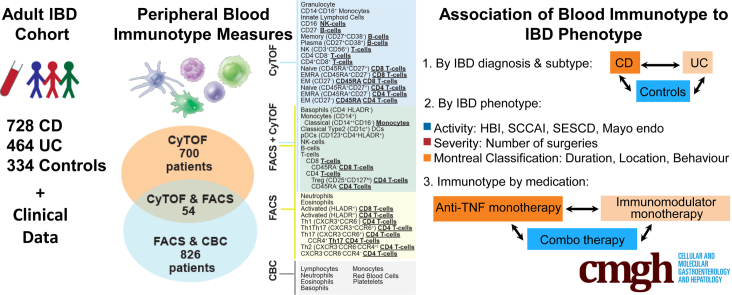

Graphical abstract

Summary.

Few peripheral immune cell types are affected in both ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease, with immunophenome largely distinct between the two IBD subsets. Concomitant use of anti-tumor necrosis factor and thiopurines produced a distinct immunphenome reflecting mainly additive effects of either monotherapy alone, with nuanced impact on B-cell subsets.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic inflammation of the digestive tract. The development and progression of Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) in part reflect immune intolerance to the microbiome at the gut surface.1, 2, 3, 4 Innate and adaptive immune responses in specific tissues generally depend on the trafficking of immune cells to the affected organ. In active IBD, there is a reported contraction of the peripheral blood regulatory T cell (Treg) pool attributed to gut homing.5 In contrast, cells associated with local mucosal inflammation, such as activated B cells, can also recirculate to the periphery influencing both local and systemic immunity.6 Thus, overall IBD can be considered a systemic disease7; however, despite this, the state of the peripheral immunophenome is largely unexplored, especially with respect to IBD subphenotypes and medication effects.

Extensive efforts have been applied to standardize clinical phenotyping and subclassification of IBD patients to facilitate treatment decisions as well as prognostication.8 The subtyping variables include the age of onset, location, and extent of disease in CD and UC and disease behavior in CD, as these are considered the main factors affecting disease course and prognosis. Cleynen et al9 recently addressed genetic factors shaping disease subphenotypes, with colonic-only CD was shown to be genetically intermediate between ileal-only CD and UC. However, no loci could explain disease extension, progression, or extraintestinal manifestations, suggesting that rare or nongenetic factors are important. Interestingly, while a few immune cell population frequencies are heritable, the majority are not, emphasizing the environmental influences10 on the immune system. Thus, in an immune-mediated disease such as IBD, understanding the reshaping of immune landscape could provide valuable insight into the disease pathophysiology. However, prior studies of circulating immune populations in IBD have either focused on deep phenotyping of a single immune subtype or are broader immune cell surveys in relatively small, underpowered cohorts with limited metadata or subtyping, and without assessing UC and CD on a common platform to enable cross-disease comparisons.11

In this study, we associated immune-centric intermediate phenotypes as captured by the blood immunophenome to classical IBD subphenotypes including disease type, location, duration, behavior, extent, and response to medications. We provide for the first time a comprehensive analysis of 39 different lymphoid or myeloid cell subsets from the blood of a large cohort of IBD patients and control subjects. The cohort was split into 2 subcohorts for immunophenotyping either by flow-based or mass spectrometry–based methods allowing for (1) replication of associations for cell populations measured by both methods and (2) expanding the number of diverse immune cells surveyed. This data and analysis resource serves as another layer of IBD subphenotyping that could bridge how underlying genetic or environmental factors influence IBD disease heterogeneity including response to medications.

Results

Blood Immunotypes by IBD Diagnosis

Immunophenotyping data was obtained from 728 CD, 464 UC, and 334 control Mount Sinai Crohn’s and Colitis Registry (MSCCR) subjects, which represents a cross-sectional snapshot of a large IBD cohort. The cohort demographic and clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1 and the study design is described in Figure 1 with 2 prioritized questions, namely the immune cell types associated with (1) disease subtypes and phenotypes and (2) medication use.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for the MSCCR Immunophenotyped Cohort

| Outcome | FACS Subcohort |

PFACSa | CyTOF Subcohort |

PCyTOF | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | CD | UC | Control | CD | UC | |||

| Number of patients with | n = 171 | n = 392 | n = 263 | n = 163 | n = 336 | n = 201 | ||

| Ncbc: CBC | nCBC = 170 | nCBC= 392 | nCBC= 261 | |||||

| N1: panel 1 | n1= 147 | n1= 346 | n1= 228 | |||||

| N2: panel 2 | n2= 161 | n2= 386 | n2= 262 | |||||

| Demographic measures: | ||||||||

| Age at endoscopy, y | 54.0 (51–61) | 40 (29–54) | 45.0 (33–58) | <10–5 | 53 (48–58) | 36 (30–50) | 43 (32–57) | <10–5 |

| Female | 86 (50.3) | 187 (47.7) | 123 (46.8) | .766 | 75 (46.0) | 144 (42.9) | 92 (45.8) | .723 |

| Smoking | 12 (7.0) | 18 (4.6) | 5 (1.9) | .031 | 18 (11.0) | 22 (6.5) | 8 (4.0) | .028 |

| Continental ancestry | <10–5 | <10–5 | ||||||

| European | 88 (51.5) | 337 (86.0) | 215 (81.7) | <10–5 | 96 (58.9) | 277 (82.4) | 171 (85.1) | <10–5 |

| Amerindian (Native American) | 39 (22.8) | 27 (6.9) | 21 (8.0) | <10–5 | 32 (19.6) | 32 (9.5) | 13 (6.5) | <10–3 |

| African American | 35 (20.5) | 16 (4.1) | 16 (6.1) | <10–5 | 25 (15.3) | 16 (4.8) | 1 (0.5) | <10–5 |

| East Asian | 5 (2.9) | 5 (1.3) | 6 (2.3) | .37 | 4 (2.5) | 5 (1.5) | 7 (3.5) | .316 |

| Other/Multiple | 2 (1.2) | 7 (1.8) | 5 (1.9) | .839 | 6 (3.7) | 5 (1.5) | 7 (3.5) | .217 |

| Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry | <10–5 | <10–5 | ||||||

| Not Ashkenazi Jewish | 155 (90.6) | 254 (64.8) | 168 (63.9) | <10–5 | 131 (80.4) | 183 (54.5) | 113 (56.2) | <10–5 |

| Full Ashkenazi Jewish | 12 (7.0) | 113 (28.8) | 81 (30.8) | <10–5 | 26 (16.0) | 129 (38.4) | 69 (34.3) | <10–5 |

| Partial Ashkenazi Jewish (25%–75) | 4 (2.3) | 25 (6.4) | 14 (5.3) | .139 | 6 (3.7) | 24 (7.1) | 19 (9.5) | .099 |

| IBD-related outcomes | ||||||||

| Age at IBD diagnosis, y | NA | 23 (17–32) | 25 (20–37) | .004 | NA | 23 (18–30) | 25 (20–38) | .002 |

| Disease duration, y | NA | 16.3 ± 12.6 | 16.4 ± 12.5 | .911 | NA | 14.7 ± 12.1 | 15.7 ± 12.9 | .335 |

| Disease duration | .512 | .68 | ||||||

| Over 5 y | NA | 313 (79.8) | 204 (77.6) | .546 | NA | 254 (75.6) | 158 (78.6) | .488 |

| Under 2 y | NA | 30 (7.7) | 18 (6.8) | .813 | NA | 41 (12.2) | 20 (10.0) | .512 |

| Endoscopically defined IBD activity | .02 | .301 | ||||||

| SES-CD (CD) and MayoEndo (UC) | ||||||||

| Inactive | NA | 155 (39.5) | 113 (43.0) | .36 | NA | 159 (47.3) | 112 (55.7) | .073 |

| Mild | NA | 113 (28.8) | 93 (35.4) | .075 | NA | 109 (32.4) | 53 (26.4) | .166 |

| Moderate | NA | 91 (23.2) | 38 (14.4) | .009 | NA | 46 (13.7) | 24 (11.9) | .652 |

| Severe | NA | 33 (8.4) | 16 (6.1) | .356 | NA | 22 (6.5) | 12 (6.0) | .934 |

| Clinically defined IBD activity | .061 | .057 | ||||||

| HBI (CD) and SCCAI (UC) | ||||||||

| Inactive | NA | 261 (66.6) | 228 (86.7) | .061 | NA | 253 (75.3) | 185 (92.0) | .057 |

| Active | NA | 63 (16.1) | 35 (13.3) | .061 | NA | 41 (12.2) | 16 (8.0) | .057 |

| Other autoimmune diseases | ||||||||

| Any autoimmune disease | NA | 48 (12.2) | 17 (6.5) | .022 | NA | 29 (8.6) | 19 (9.5) | .868 |

| Psoriasis | NA | 25 (6.4) | 11 (4.2) | .301 | NA | 8 (2.4) | 13 (6.5) | .033 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | NA | 18 (4.6) | 2 (0.8) | .01 | NA | 15 (4.5) | 5 (2.5) | .35 |

| Ankylosing spondylitis | NA | 8 (2.0) | 3 (1.1) | .57 | NA | 8 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | .066 |

| Medication useb | ||||||||

| Mesalamine medications combined | NA | 113 (28.8) | 180 (68.4) | <10–5 | NA | 88 (26.2) | 129 (64.2) | <10–5 |

| Sulfasalazine | NA | 21 (5.4) | 28 (10.6) | .018 | NA | 17 (5.1) | 14 (7.0) | .468 |

| Mesalamine oral | NA | 95 (24.2) | 152 (57.8) | <10–5 | NA | 72 (21.4) | 117 (58.2) | <10–5 |

| Mesalamine rectal | NA | 6 (1.5) | 51 (19.4) | <10–5 | NA | 11 (3.3) | 30 (14.9) | <10–5 |

| Steroid medications (combined) | NA | 42 (10.7) | 55 (20.9) | <10–3 | NA | 27 (8.0) | 26 (12.9) | .09 |

| Budesonide | NA | 8 (2.0) | 9 (3.4) | .401 | NA | 12 (3.6) | 8 (4.0) | .995 |

| Rectal steroids | NA | 10 (2.6) | 39 (14.8) | <10–5 | NA | 8 (2.4) | 14 (7.0) | .018 |

| Corticosteroids | NA | 24 (6.1) | 19 (7.2) | .691 | NA | 11 (3.3) | 8 (4.0) | .851 |

| Antibiotics medications (combined) | NA | 49 (12.5) | 9 (3.4) | <10–3 | NA | 26 (7.7) | 2 (1.0) | .001 |

| Anti-integrin medications | NA | 14 (3.6) | 7 (2.7) | 0.673 | NA | 22 (6.5) | 11 (5.5) | .752 |

| Vedolizumab | NA | 12 (3.1) | 7 (2.7) | .951 | NA | 21 (6.2) | 11 (5.5) | .857 |

| Natalizumab | NA | 2 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | .519 | NA | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 |

| Anti-TNF medications (IFX/ADA) | NA | 149 (38.0) | 51 (19.4) | <10–5 | NA | 132 (39.3) | 38 (18.9) | <10–5 |

| Infliximab | NA | 83 (21.2) | 35 (13.3) | .014 | NA | 62 (18.5) | 28 (13.9) | .216 |

| Adalimumab | NA | 67 (17.1) | 16 (6.1) | <10–4 | NA | 70 (20.8) | 10 (5.0) | <10–5 |

| Certolizumab | NA | 27 (6.9) | 3 (1.1) | <10–3 | NA | 9 (2.7) | 0 (0.0) | .03 |

| Thiopurines | NA | 136 (34.7) | 90 (34.2) | .967 | NA | 94 (28.0) | 56 (27.9) | 1 |

NOTE. Values are median (interquartile range), mean ± SD, or n (%), unless otherwise indicated.

CBC, cell blood count; CD, Crohn’s disease; DC, dendritic cell; EM, effector memory; FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorting; FDR, false discovery rate; HBI, Harvey-Bradshaw Index; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; MayoEndo, Mayo Endoscopic Score; MSCCR, Mount Sinai Crohn’s and Colitis Registry; NA, not available; SCCAI, Simple Clinical Colitis Activity Index; SES-CD, Simple Endoscopic Score for Crohn’s Disease; UC, ulcerative colitis.

Differences between control subjects, CD patients, and UC patients or between CD and UC patients, were assessed by analysis of variance, t test, or chi-square test, as appropriate.

Self-reported medication use was not collected from control subjects (NA).

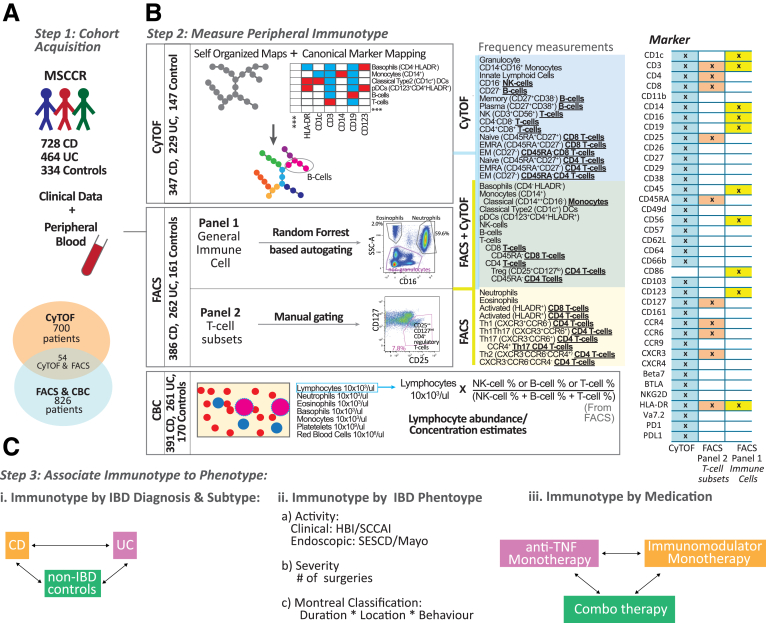

Figure 1.

Schema of the immunophenotyping study in MSCCR cohort. (A) Schema of the MSCCR immunophenotyping analyses, with (B) patients’ distribution and (C) antibody panels utilized for FACS and CyTOF. FACS analyses included 2 antibody panels targeting general immune populations (panel 1, auto-gated by a random forest–based algorithm trained on 27 samples) or T cell subsets (panel 2, manually gated by the same technician). CyTOF samples were processed via Astrolabe platform to detect canonical immune populations based on provided surface marker-to-cell subset table. Thirteen populations were measured by both platforms (green box), while 26 cell subsets were unique to one platform (yellow and blue boxes). CBC data were collected for the FACS cohort to evaluate cell populations’ abundance and were combined with NK, B, and T cells frequencies from FACS to estimate the abundance of these cells.

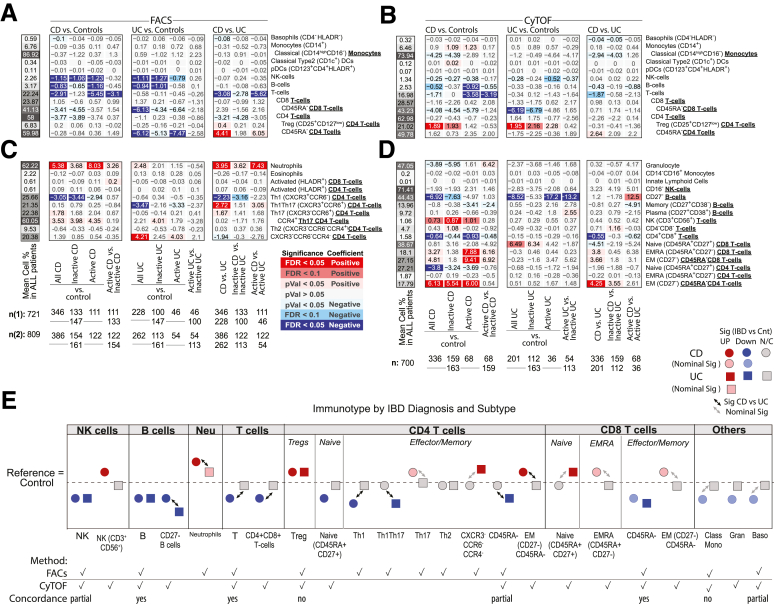

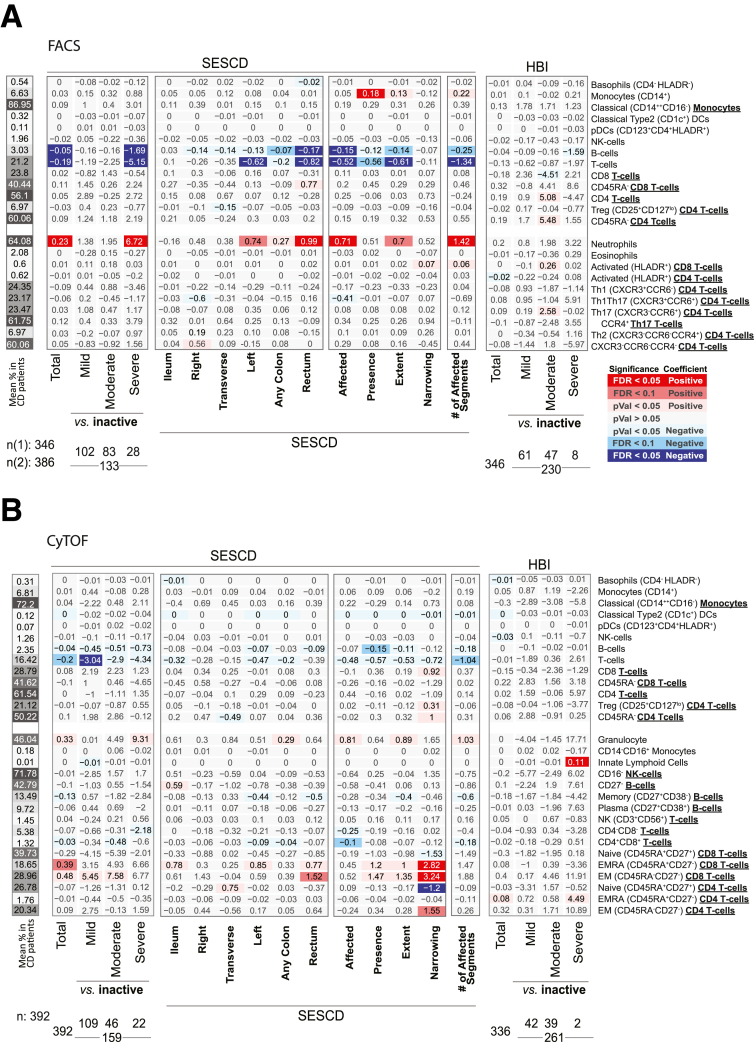

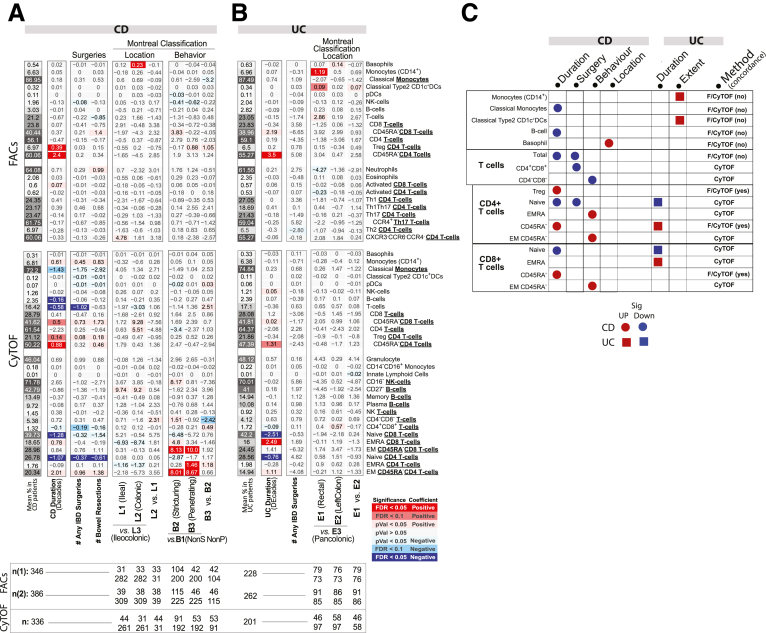

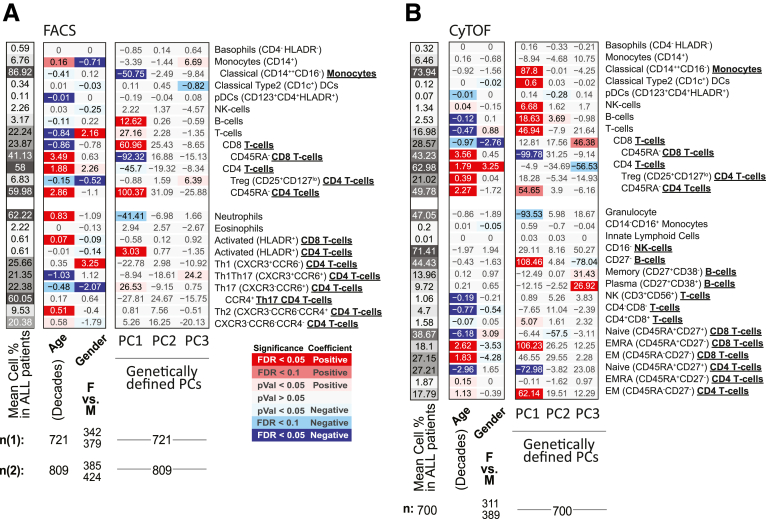

Figure 2A and B summarizes the association results by diagnosis and between UC and CD for the 13 immune cell types as measured by 2 technologies, in different patient subsets. Figure 2C and D summarizes the remaining 26 immune cell associations that were only measured by a single technology, either fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) (Figure 2C) or CyTOF (Figure 2D). Given our study design, we could evaluate if observations among the 13 cell types of Figure 2A and B were concordant and thereby also discuss our results, which are independently replicated. We defined concordance and therefore replication, as a significant result in at least 1 platform and a similar direction of change as measured with the other (Figure 2E). For example, the immune cell types found commonly (and concordantly) altered in IBD patients relative to control subjects included (1) lower frequencies of total B cells (FACS [CyTOF]: CD patients = 3.14% [2.48%], UC patients = 3.04% [2.69%], control subjects = 3.98% [3.01%]) and (2) lower natural killer (NK) cells (FACS [CyTOF]: CD patients = 2.02% [1.38%], UC patients = 2.07 [1.34%], control subjects = 3.17 [1.62%]) and (3) reduced memory (CD45RA–) CD8 T cells, a finding more pronounced in UC (FACS [CyTOF]: CD patients = 41.8% [42.5%], UC patients = 39.1% [40.4%], control subjects = 45.2% [46.6%]) with FACS: PCDvscontrol subjects = .047, qUCvscontrol subjects = .0067; CyTOF: PCDvscontrol subjects = .023, qUCvscontrol subjects = .038) (Figure 2A, B, and E). With respect to the 26 immune cells surveyed by a single technology, we observed that frequency of CD27– B cells decreased (CyTOF: CD patients = 41.6%, UC patients = 40.1%, control subjects = 48.6%) while neutrophils were increased (FACS: CD patients = 64.0%, UC patients = 61.1%, control subjects = 58.7%) in both CD and UC patients relative to control subjects (Figure 2A, B, and E).

Figure 2.

Immune cell associations with disease diagnoses and activity. Association results for CD or UC diagnosis status, endoscopic activity (active/inactive according to SES-CD and MayoEndo, respectively) with (A, C) FACS- and (B, D) CyTOF-defined populations. Populations (A, B) commonly or (C, D) uniquely defined by FACS and CyTOF methodologies are presented in the upper and lower panels, respectively. For each cell population (rows), a multivariable model including the factors presented and core covariates (see Materials and Methods) were fitted independently. Color and intensity indicate direction (red = positive, blue = negative) and significance of the association between traits (columns) and population (row). Values shown represent the estimated group differences. Populations are either defined as % of all immune cells or as % of parental populations as indicated by bold labels in the y-axis and by indentation. Gray-scaled bars on the left of each plot represent the mean cell frequency, and patient numbers are shown at the bottom. In panels A and C, FACS panels 1 (n1) and 2 (n2) have different sample size. (E) A summary of key observations for immunotype associations to IBD diagnosis or subtype and an indication if the results were concordant or not in cell populations as measured by both platforms.

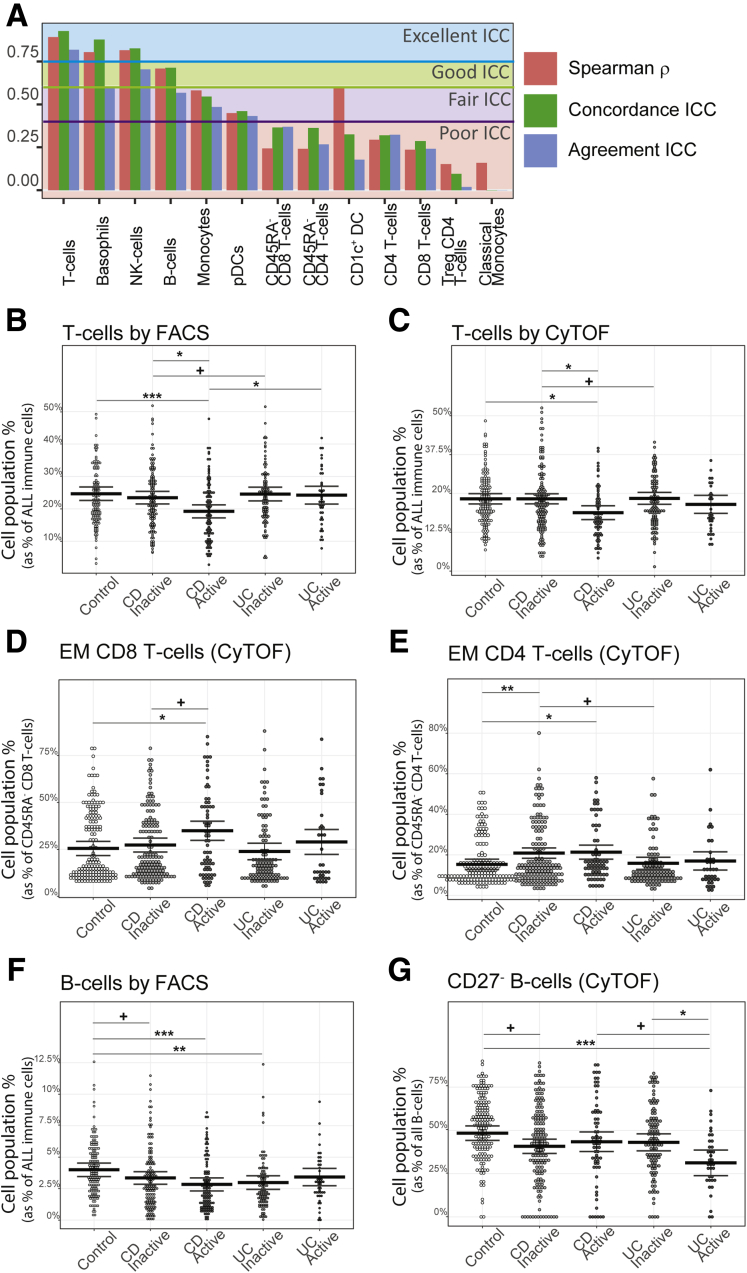

We observed a significant increase in Tregs in both IBD subtypes (CD patients = 17.9%, UC patients = 17.9%, control subjects = 16.0%) by CyTOF (Figure 2B); however, this finding was not replicated by FACS (CD patients = 6.92%, UC patients = 6.47%, control subjects = 6.72%) (Figure 2A). Given this cross-platform discordance, we evaluated more generally agreement between the 2 technologies using the immunophenotype data from 54 individuals that were evaluated using both technologies. The intraclass correlation coefficient (Figure 3A) revealed that in general immune cell types had fair to excellent agreement (T cells, B cells, NK cells, basophils, CD14+monocytes, plasmacytoid dendritic cells [DCs]), while poor agreement was observed for T cell subsets including the Tregs as well as others (CD4 and CD8 T cells and their memory subsets), in addition to classical DCs and classical CD16– monocytes.

Figure 3.

Association of T and B cells and subsets with disease status and activity. (A) Agreement of CyTOF and FACS on the cross-platform cohort, presenting Spearman’s correlation and the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) for concordance and agreement. Frequencies of B and T cells sets and subsets measured by (B, E) FACS and (C, D, E, G) CyTOF by disease subtype and endoscopic activity. Black lines represent estimated marginal mean and 95% confidence interval from models with relevant covariates. (+P ≤ .05,∗q ≤ .05,∗∗q ≤ .01,∗∗∗q ≤ .001).

Immunotypes Specifically Associated With CD

Several immune cell alterations were uniquely altered in CD relative to healthy control subjects. Concordant results included lower levels of total T cells in CD relative to control subjects (FACS [CyTOF]: (CD patients = 21.4% [17.3%], UC patients = 23.7% [18.7%], control subjects = 24.3% [19.0%]). Other immune cell alterations specifically associated with CD patients in CyTOF-measured populations included increased effector memory (EM) CD4 (CD patients = 20.6%, UC patients = 15.0%, control subjects = 14.5%), EM CD8 (CD patients = 29.4%, UC patients = 24.3%, control subjects = 24.6%), and NK T cells (CD patients = 1.12%, UC patients = 0.65%, control subjects = 0.38%). In contrast, we observed reduced levels of helper T cell 1 (Th1) (CXCR3+CCR6–) (FACS: CD patients = 23.0%, UC patients = 25.4%, control subjects = 26.0%) subsets, naïve CD4 T cells (CyTOF: CD patients = 27.2%, UC patients = 30.3%, control subjects = 31.0%), and CD4+CD8+ T cells (CyTOF: CD patients = 1.47%, UC patients = 196%, control subjects = 2.10%) (Figure 2A–E) in CD vs healthy control subjects. Nominally significant alterations specific to CD vs control included elevated EM and EMRA CD8 T cells, and Th17 T cells, while classical monocytes (CD14hiCD16–), granulocytes, and basophils were decreased (Figure 2E).

Clinical and endoscopic scoring systems are clinical tools used to subclassify IBD activity. A common CD clinical index, is the Harvey-Bradshaw Index (HBI) which evaluates disease by patient questionnaire. In our study only cell blood count (CBC)–defined populations showed significant associations with total HBI scores. These included increased abundance of neutrophils, monocytes, and platelets (Figures 4 and 5). A common endoscopic measure of CD activity, is the Simple Endoscopic Score in CD (SES-CD), which consists of 4 components (reflecting active inflammation: presence/size ulcers; mucosal healing: “extent” ulcerated or “affected” surface; and fibrosis: presence/type “narrowings”) scored from 0 to 3 in 5 bowel segments. Using the SES-CD evaluations we subcategorized patients with active or inactive disease at the time of measure (see Materials and Methods) and assessed which immune cell associations with CD diagnosis were dependent on “active” disease state. The total T and B cell populations, as well as neutrophils, CD4+CD8+ T cells, EMRA CD8 T cells and EM CD45RA- CD8 T cells were all significantly altered (false discovery rate [FDR] < .1) in CD patients with active disease vs control subjects but were much less altered (FDR > .1) in contrasts between inactive CD vs healthy control subjects. NK cells, CD27– B cells, Th1, Treg, NK T cells, and EM (CD45RA–) CD4 T cells, however, appeared associated with CD status largely independent of active disease status as significant changes (FDR < .1) were observed in inactive CD patients vs control subjects (Figures 2A and B and 3B–G).

Figure 4.

Immune cell association with disease activity measures in CD patients. Association results for CD activity measured endoscopically (SES-CD) and based on clinical evaluations (HBI) with (A) FACS- and (B) CyTOF-defined populations. Heatmap coloring and intensity indicate direction (red = positive, blue = negative) and significance of the association between the trait (columns) and cell frequency (row). Values shown represent the association for each trait: for continuous variables (SES-CD Total), they represent frequency increase per unit of change in the trait (column) or the estimated difference between the 2 groups for categorical variables (severe vs inactive). The SES-CD components include the presence and type of ulcers (presence), extent of ulcerated surface (extent), extent of affected surface (affected), and presence and severity of narrowing/stenosis (narrowing), with 4 levels per measure available from 5 ileocolonic regions: ileum, right/ascending, transverse and left/descending/sigmoid colon, and rectum. Sample sizes (n) are as presented at the bottom.

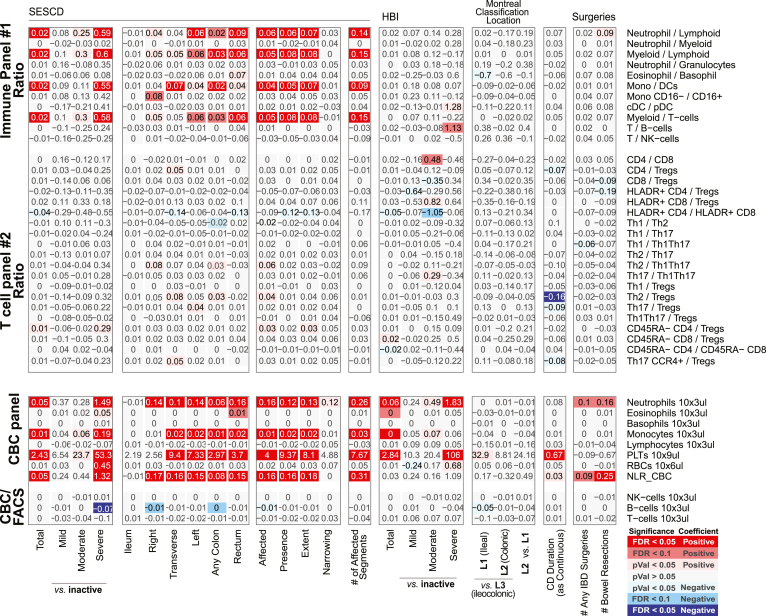

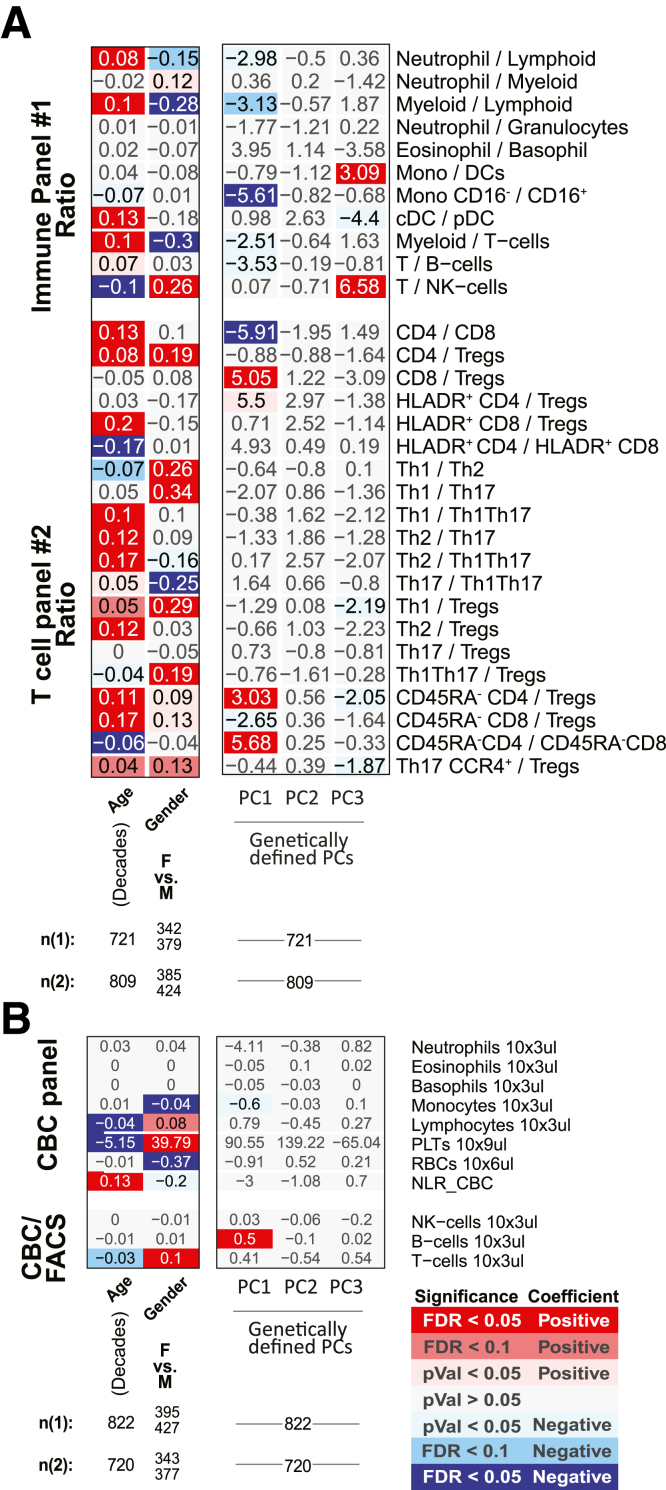

Figure 5.

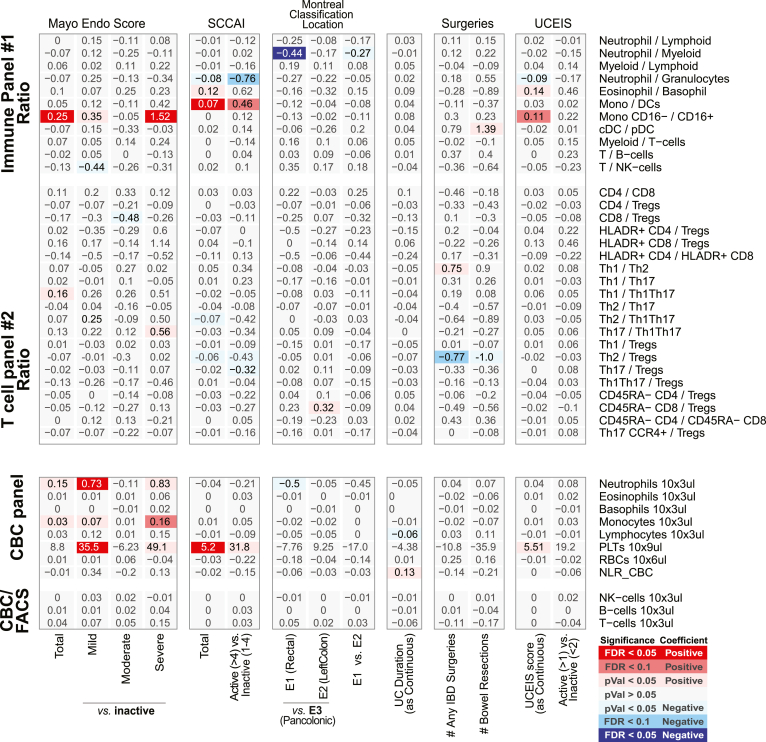

Immune cell association with disease activity, location, duration, and severity measures in CD patients for ratios between FACS-defined immune cell types and CBC. Association results for CD duration (measured in decades), location (Montreal Classification) severity (number of IBD-related surgeries), or activity measured endoscopically (SES-CD, Simple Endoscopic Score for Crohn’s Disease) or based on clinical evaluations (HBI, Harvey-Bradshaw Index). Heatmap coloring and intensity indicate direction (red positive, blue negative) and significance of the association between the trait (columns) and cell frequency (row). Values shown represent the association for each trait: for continuous variables (SES-CD Total), they represent frequency increase per unit of change in the trait (column); or the estimated difference between the 2 groups for categorical variables (severe vs inactive). The SES-CD components include the presence and type of ulcers (presence), extent of ulcerated surface (extent), extent of affected surface (affected), and presence and severity of narrowing/stenosis (narrowing), with 4 levels per measure available from 5 ileocolonic regions: ileum, right/ascending, transverse and left/descending/sigmoid colon, and rectum. Sample size (n) is presented at the bottom. (A) The ratios between immune/myeloid panel 1 populations were analyzed in the total of 721 patients, and the ratios between T cell panel 2 were analyzed in the total of 809 patients. The distribution of observations per categorical level is shown in the column descriptions below the plot, with the first value (n(1)) referring to analyses with the immune/myeloid panel 1 populations’ ratios and the latter value (n(2)) referring to the analyses with T cell panel 2 populations’ ratios. (B) The analyses of CBC data (the top 8 rows) were done with a linear model without inclusion of technical FACS relevant variables in the total of 806 patients. The estimated concentration of lymphocyte populations, based on combination of CBC and FACS data, was analyzed with a full mixed model in the total of 720 patients. The distribution of observations per categorical level is shown in the column descriptions below the plot, with the first value (n(1)) referring to the 8 CBC populations, and the latter value (n(2)) referring to the analyses with the 3 estimated lymphocyte concentration measures.

We next associated the blood immune cell types in CD patients according to the total SES-CD score (as a continuous variable) as well as its subcomponents. Consistent with active vs healthy control comparisons, we observed significant associations of neutrophils, B cells, and T cells with the total SES-CD score (Figure 4), primarily seen with the “affected” and “extent” ulceration subcomponent scores. The measure with the strongest observed associations with immune cell proportions was the number of the ileocolonic regions (out of the total of 5 utilized for SES-CD score) with any subscore >0 (in the affected, presence, extent, or narrowing category) (Figure 4). In a follow-up analysis, we included both the total SES-CD score and the number of regions affected in the same multivariate model and observed that the T cell frequency was significantly associated only with the number of affected ileocolonic regions (FACS: β = –1.60; CyTOF: β = –0.18; P < .05 in both) but not with the total SES-CD score. Thus, the total T cell pool in blood may reflect the overall extent of the intestinal inflammation.

We also observed immune cell types uniquely associated with the narrowing SES-CD subcomponent, namely, elevated EMRA and EM CD8 T cells and EM CD4 T cells, and reduced native CD4 T cells. Consistent with these observations was the significant positive associations observed between these same cells types and the CD Montreal classifications characterizing patients’ disease behavior, namely B2 (stricturing) and B3 (penetrating) vs B1 (nonstricturing and nonpenetrating) disease (Figure 6A). Whether these cell types reflect the fibrotic and scarring processes at play with narrowing phenotype or structuring of the intestine is of interest.

Figure 6.

Immune cell associations with disease duration, severity, and location in CD and UC patients. Association results for IBD duration (measured in decades), severity (number of IBD-related surgeries), or location (Montreal classification) with FACS- and CyTOF-defined populations for (A) CD and (B) UC. For continuous traits (IBD duration/severity), values represent the frequency increase per unit of change in the trait, while for categorical variables they define the intergroup differences. Figure components are as in Figure 2. (C) Diagram summarizing the significant findings for the CD and UC measures.

Immunotypes Specifically Associated With UC

Considering UC specific changes, Th1Th17 cells (CXCR3+CCR6+) (CD patients = 22.6%, UC patients = 19.0%, control subjects = 22.5%) were significantly lower, while CXCR3–CCR6–CCR4– CD4 T cells (CD patients = 18.1%, UC patients = 20.7%, control subjects = 16.1%), and naïve CD8+ T cells (CD45RA+CD27+) (CD patients = 38.6%, UC patients = 44.3%, control subjects = 37.8%) were higher in UC than in either CD or control subjects. Memory CD4 T cells were also found significantly lower in UC compared with control subjects and CD by FACS (CD patients = 61.5%, UC patients = 55.6%, control subjects = 61.8%) but only trending in the same direction by CyTOF (Figure 2A and C).

A commonly used questionnaire-based UC clinical disease activity index is the Simple Colitis Activity Index (SCCAI), and similar to CD, only CBC-defined immune cells were associated with SCCAI, namely elevated platelets (Figures 7 and 8). We did note, however, that SCCAI was associated with a higher ratio of CD14+ monocytes to DCs (both classical CD1c+ and plasmacytoid DCs) (Figure 8).

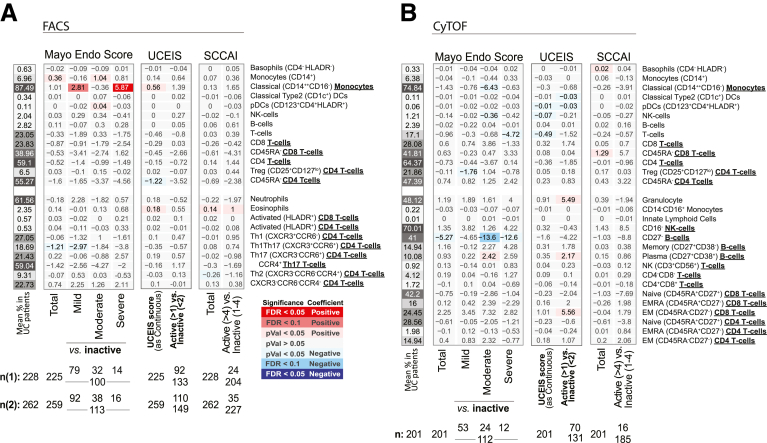

Figure 7.

Immune cell association with disease activity measures in UC patients. Association results for UC endoscopic measures of disease activity (MayoEndo and UCEIS) and based on clinical evaluations (SCCAI) with (A) FACS- and (B) CyTOF-defined populations. Values shown represent the association for each trait: for continuous variables (total MayoEndo), they represent frequency increase per unit of change in the trait (column) or the estimated difference between the 2 groups for categorical variables (severe vs inactive). Sample sizes (n) are presented at the bottom.

Figure 8.

Immune cell association with disease activity, location, duration, and severity measures in UC patients for ratios between FACS-defined immune cell types and CBC. Association results for UC duration (measured in decades), location (Montreal classification) severity (number of IBD-related surgeries), endoscopic measures of disease activity (MayoEndo and UCEIS) and based on clinical evaluations (SCCAI). Values shown represent the association for each trait: for continuous variables (total MayoEndo), they represent frequency increase per unit of change in the trait (column) or the estimated difference between the 2 groups for categorical variables (severe vs inactive). Sample sizes (n) are presented at the bottom. (A) The ratios between immune/myeloid panel 1 populations were analyzed in the total of 721 patients, and the ratios between T cell panel 2 were analyzed in the total of 809 patients. The distribution of observations per categorical level is shown in the column descriptions below the plot, with the first value (n(1)) referring to analyses with the immune/myeloid panel 1 populations’ ratios, and the latter value (n(2)) referring to the analyses with T cell panel 2 populations’ ratios. (B) The analyses of CBC data (the top 8 rows) were done with a linear model without inclusion of technical FACS relevant variables in the total of 806 patients. The estimated concentration of lymphocyte populations, based on combination of CBC and FACS data, was analyzed with a full mixed model in the total of 720 patients. The distribution of observations per categorical level is shown in the column descriptions below the plot, with the first value (n(1)) referring to the 8 CBC populations, and the latter value (n(2)) referring to the analyses with the 3 estimated lymphocyte concentration measures.

A common endoscopic measure of UC disease activity is an endoscopic component of the Mayo Endoscopic Score (MayoEndo) with 4 levels, ranging from normal or inactive colitis (score = 0) to severe colitis with ulcerations and spontaneous bleeding (score = 3). Using the MayoEndo, we subcategorized MSCCR patients with active or inactive disease (see Materials and Methods), and assessed which immune cell changes associated with UC diagnosis were dependent on active disease status at the time of measure. For the most part, any immune cells found altered in all UC vs control comparisons were also altered in inactive UC vs control subsets. Only memory CD4 T cells, CCCR6–CXCR3–CCR4–CD4 T cells, Th1Th17, and CD27– B cells showed stronger effects in the active UC vs control comparisons, suggesting more pronounced inflammatory-associated changes.

Considering the total MayoEndo (as a continuous variable), only nominally significant associations were observed with Th1Th17, CD27– B cells, and monocytes (CD14+). Furthermore, the ratio between classical (CD16–) and nonclassical (CD16+) monocytes was significantly increased with endoscopic activity (Figure 8). When we restricted the analysis to the UC patient subset with the most severe disease (MayoEndo = 3), we observed a significant increase in classical monocytes (CD14++CD16–) relative to inactive UC patients; however, this was not replicated in the CyTOF platform.

Finally, we also considered the Montreal classifications characterizing patients according to locations of disease, only the CD14+ monocytes were also significantly increased in patients with rectal (E1) disease compared with patients with pancolitis (E3) (E1 = 6.58%; E2 = 5.89%; E3 = 5.38%) (Figure 6B). Overall, the differences in immune cell associations depending on whether using clinical or endoscopic disease activity indices is not surprising given the discordance often cited between these 2 clinical indices.12

Key Immunotypes Distinguishing CD and UC Subtypes

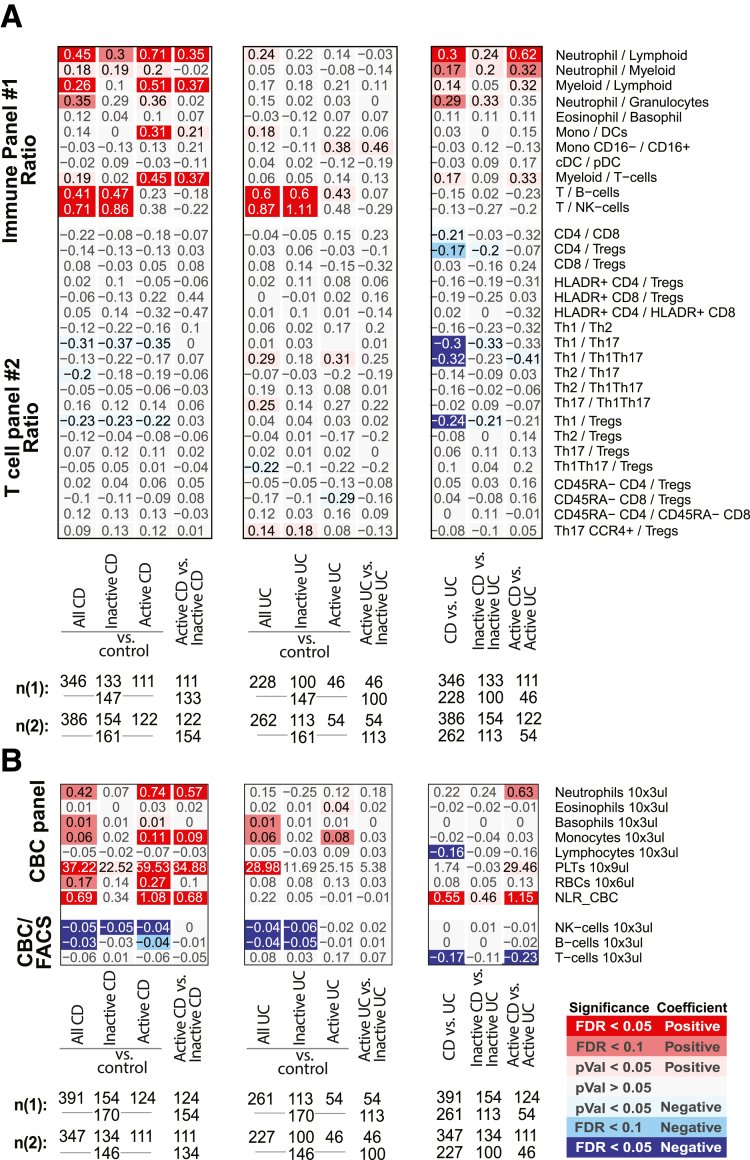

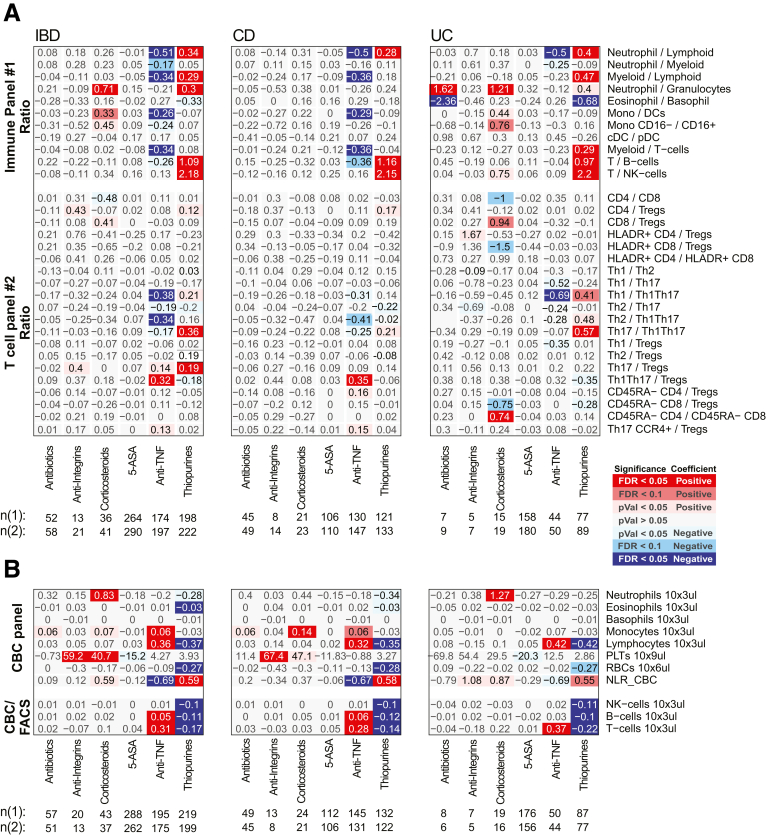

Altogether, the populations distinguishing CD from UC included higher proportions of (1) neutrophils, (2) Th1Th17, (3) memory (particularly EM) CD4 T cells, and (4) CD27– B cells (as fraction of all B cells, and in patients with active IBD only) and lower proportions of (5) the overall T cell compartment, (6) Th1, and 7) CD4+CD8+ T cells (Figure 2A–D). The ratios between Th1 vs Th17, Th1Th17, or Tregs were also lower in CD (Figure 9), corroborating previously observed differences in T cell responses between IBD subsets.13 We also recapitulate the known connection between platelet levels and UC diagnosis.

Figure 9.

Association with disease diagnoses and activity for ratios between FACS-defined immune cell types and CBC. For each cell population (rows), a multivariable model including the factors presented and the core covariates (see Materials and Methods) were fitted independently. Heatmap coloring and intensity indicate direction (red = positive, blue = negative) and significance of the association between the trait (columns) and cell frequency (row). Values shown are the estimated difference between the 2 groups. Numbers of patients per level of categorical variables are shown at the bottom. For analyses with the ratios the mixed effect models include FACS antibody batch as a random effect, while analyses with CBC measurements were analyses as linear models. (A) The ratios between immune/myeloid panel 1 populations were analyzed in the total of 721 patients, and the ratios between T cell panel 2 were analyzed in the total of 809 patients. The distribution of observations per categorical level is shown in the column descriptions below the plot, with the first value referring to analyses with the immune/myeloid panel 1 populations’ ratios, and the latter value referring to the analyses with T cell panel 2 populations’ ratios. (B) The analyses of CBC data (the top 8 rows) were done with a linear model without inclusion of technical FACS relevant variables in the total of 806 patients. The estimated concentration of lymphocyte populations, based on combination of CBC and FACS data, was analyzed with a full mixed model in the total of 720 patients. The distribution of observations per categorical level is shown in the column descriptions below the plot, with the first value referring to the 8 CBC populations, and the latter value referring to the analyses with the 3 estimated lymphocyte concentration measures.

The immature CD27– B cells (primarily transitional CD38+ B cells) stood out as a key distinguishing cell type, as they were reduced both in CD (CDActive = 43.5%, CDInactive = 40.8%, control subjects = 48.4%) and UC (UCActive = 31.3%, UCInactive = 43.1%) yet could further differentiate active UC from active CD (q = 0.098) (Figure 2D). Furthermore, CD27– B cells were lower with moderate and severe UC disease (Mayo= 2 or 3, respectively) than with inactive disease (UCInactive = 32.5%, UCModerate = 18.9%, UCSevere = 19.9%) and control subjects (Figure 2D and E). CD27– B cells, while not associated with SES-CD total score, were nominally positively associated with the ileum SES-CD subscore (insignificant in large intestinal regions) as well as ileocolonic (L3) vs ileal (L1) or colonic (L2) only disease according to the Montreal classification. Of note, basophil frequency was the only significant result that was higher in patients with colonic CD (L2) vs ileocolonic CD (L3) (L1 = 0.61%, L2 = 0.72%, L3 = 0.49%) (Figure 6A and C). Whether these regional immune cell associations reflect underlying differences in inflammatory processes ongoing in large vs small intestine is of interest.

Peripheral Blood CD4+ Tregs Are Associated With Disease Duration

After adjusting for endoscopic activity, the most robust associations were higher memory CD4 T cells (by FACS) with disease duration in both CD (β = 2.4% increase per decade) and UC (β = 3.5%) and increased Tregs in CD patients only (FACS: β = 0.39%; CyTOF: β = 0.14%) (Figure 6). The memory CD4 T cells and, surprisingly, also the Treg associations were confirmed by 2 immunophenotyping platforms, suggesting that IBD is progressively altering the immune system by shifting the balance from naïve to memory T cells and, at least in CD, may include a compensatory rise of Tregs.

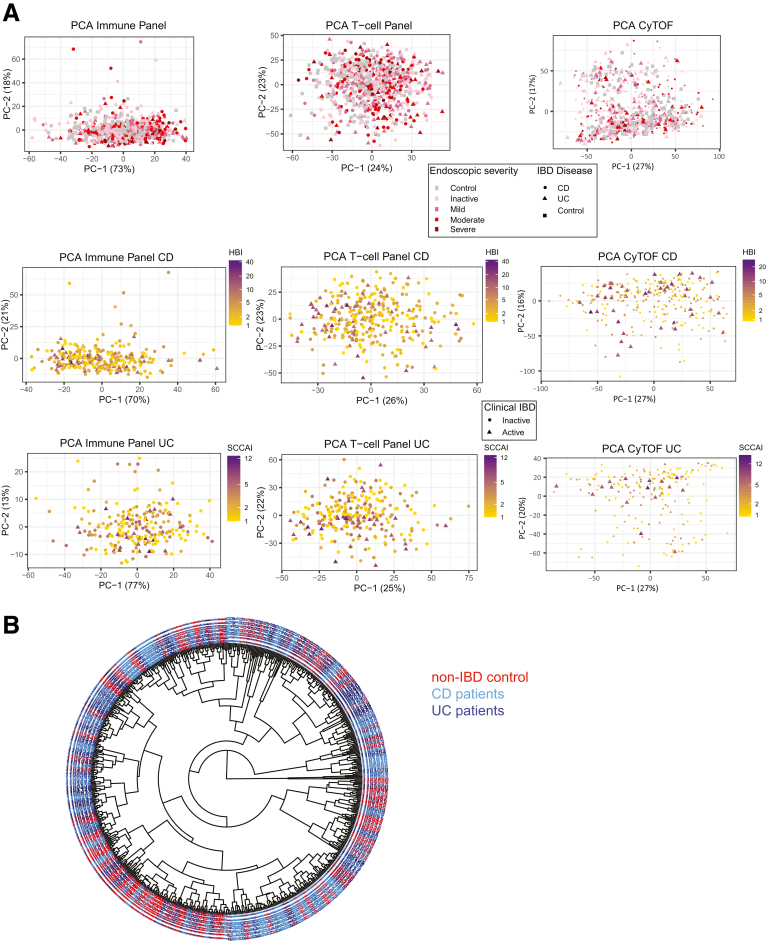

A Data-Driven Survey to Define a Peripheral Immunotype That Can Distinguish IBD and IBD Subtypes

Despite the significant associations of cell frequency and ratios with disease phenotype and activity, substantial heterogeneity within patients was observed (Figure 10). We used machine learning methods to determine if combinations of cell populations could diagnose IBD or discriminate IBD subtypes. A random forest model distinguished IBD patients with area under the curves (AUCs) of 0.87 in the training set (75% of the data) and 0.67 in the remaining 25% testing set by FACS (0.88 and 0.66 by CyTOF, respectively). Cell population ratios had slightly better predictive power (testing AUC in FACS: 0.74; CyTOF: 0.71). Discrimination between disease subtypes was less accurate (AUC <0.62 [FACS] and <0.57 [CyTOF]), with Th1Th17 (FACS), and EM CD4 and CD8 (CyTOF) T cells being most discriminative, as in the association analysis (Figure 2C and D). These results highlight the complexity of peripheral inflammation and the challenges of immunophenotyping in clinical practice.

Figure 10.

IBD patient clustering with the immunophenotyping data. Unsupervised distributions of patients according to the immune cell frequencies: (A–C) by principal component analyses (PCAs) or (D, E) by hierarchical clustering with FACS or CyTOF based populations. (A) PCAs of all CD, UC, and non-IBD control subjects (first 2 axes shown) utilizing all populations in FACS panel 1 (left plots), FACS panel 2 (central plots), or CyTOF (right plots), with the shape of the point indicating the IBD disease status and color indicating the endoscopic-defined disease activity. (B, C) PCAs of all CD or UC patients (first 2 axes shown) utilizing all populations in FACS panel 1 (left plots), FACS panel 2 (central plots), or CyTOF (right plots), with the shape of the point indicating whether the patient had active or inactive disease based on SES-CD (for CD) or MayoEndo (for UC) measures and the color indicating the clinically defined disease activity (HBI for CD and SCCAI for UC). (D, E) Hierarchical clustering of all CD, UC, and non-IBD control subjects (first 2 axis shown) utilizing all populations in combined FACS panel 1 and FACS panel 2 or CyTOF populations. (Euclidian distance metrics and average clustering method). Color of the patient IDs indicates IBD status.

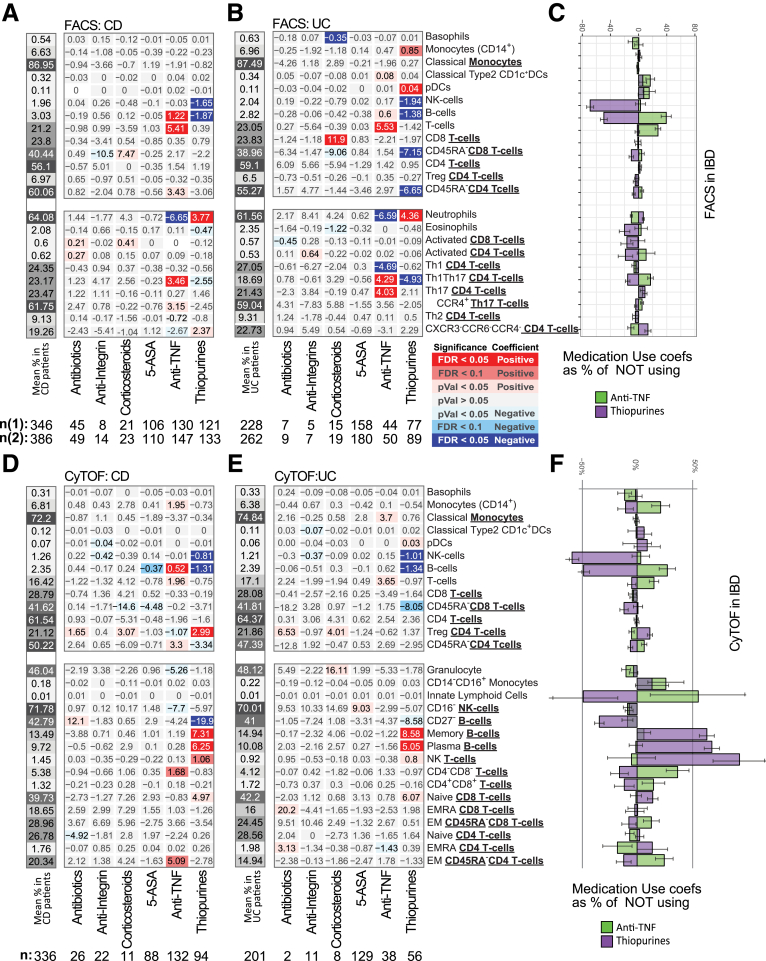

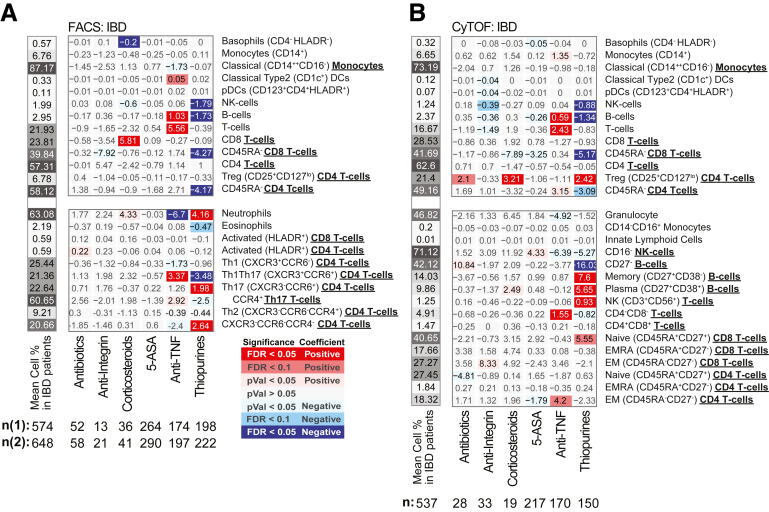

The Immune System Is Reshaped by IBD Medication Use

We investigated the impact of 6 commonly prescribed medications for IBD using a multivariable model and the 4-category endoscopic activity index. The observations (Figures 11A, B, D, and E, 12, and 13) ranged from affecting a few cell types (see corticosteroids in UC) to broadly impacting, as seen with thiopurine and anti-TNF use (Figure 11A, B, D, and E). The changes with anti-TNF or thiopurines use were predominantly in opposing directions (Figures 11C–F and 12).

Figure 11.

Immune cells association with medication use in CD and UC patients. Medication effects in (A, D) CD and (B, E) UC patients. For each population the multivariable model includes also endoscopic activity and core covariates. Values represent the cell frequency differences between CD and UC patients taking or not taking the medication, adjusting for disease severity. (C–F) Bars indicate the medication effects (±SE) as a percentage of cell frequency among nonusers.

Figure 12.

Immune cell association of medication use in IBD patients. Medication effects for (A) FACS- and (B) CyTOF-defined populations in IBD patients. Immune cell populations defined in both FACS and CyTOF methods are shown in the upper panels, and populations as defined only by FACS or CyTOF are shown in the lower panels. For each population a multivariate model including IBD disease, endoscopic activity, and core covariates was fitted independently. Heatmap coloring and intensity indicates direction and significance of the association between the trait (columns) and cell frequency (row). Values shown are medication effect, expressed as the differences in frequency between patients taking the medication vs those not taking it.

Figure 13.

Immune cell association with medication use in CD and UC patients for ratios between FACS-defined immune cell types and CBC. Association results for the self-reported medication use (at the time of study endoscopy) ratios between FACS-defined immune cell types, and CBC. Values shown are medication effect, expressed as the differences in frequency between patients taking the medication and those not taking it. Color and intensity indicate direction (red = positive, blue = negative) and significance of the association per medication (column) and cell frequency (row). (A) The ratios between immune/myeloid panel 1 populations were analyzed in the total of 721 patients, and the ratios between T cell panel 2 were analyzed in the total of 809 patients. The distribution of patients taking the medications is shown in the column descriptions below the plot, with the first value (n(1)) referring to analyses with the immune/myeloid panel 1 populations’ ratios, and the latter value (n(2)) referring to the analyses with T cell panel 2 populations’ ratios. (B) The analyses of CBC data (the top 8 rows) were done with a linear model without inclusion of technical FACS relevant variables in the total of 806 patients. The estimated concentration of lymphocyte populations, based on combination of CBC and FACS data, was analyzed with a full mixed model in the total of 720 patients. The distribution of patients taking the medications is shown in the column descriptions below the plot, with the first value (n(1)) referring to the 8 CBC populations and the latter value (n(2)) referring to the analyses with the 3 estimated lymphocyte concentration measures.

Thiopurine Use Mimics Many of the Immune Cell Changes Associated With IBD

Response to thiopurine use was dramatic affecting 8 immune populations in CD, 10 in UC, and 15 in a CD/UC combined analysis (Figures 11 and 12). Thiopurine use increased neutrophils, NK T cells, memory and plasma B cell subsets, naïve CD8 T cell subsets, and Tregs (by CyTOF, not confirmed by FACS) (Figure 12) and a lower frequency of the total B cell compartment, CD27– B cell subset, NK cells, eosinophils, and Th1Th17 and Th2 T cell subsets. Apart from the CD27– B cell subset (CD: Δ = –19.9%, UC: Δ = –8.58%), the thiopurine effect was similar in both IBD subtypes (Figure 11). Interestingly, many of these cell types showed the same direction of association with CD or UC diagnosis or activity, with higher neutrophil, NK T cell, and Treg and lower NK, total B, and T cell compartments, and Th1Th17 and CD27– B cell subset frequencies. Abundance of many blood cells was also reduced with thiopurine use, including eosinophils (Δ = –0.027 × 103/μL) and lymphocytes (Δ = –0.37 × 103/μL), with a trend for neutrophils (Δ = –0.28 × 103/μL, P = .029) (Figure 13B). The observed reduction in lymphocyte frequency was greater than for neutrophils, resulting in a higher NLR. Overall, we observed that thiopurine use appeared to mimic the immune changes associated with IBD diagnosis and activity.

Anti-TNF Monotherapy Reverses Many of the Immune Profile Changes Observed Between IBD and Control

Anti-TNF use, in contrast to thiopurines, decreased neutrophil, and increased B and T cell frequencies, similarly in UC and CD (Figures 11A and B and 12). The reduction in NLR and neutrophil frequency and the increase in lymphocyte frequency with anti-TNF therapy were more likely due to elevated numbers of lymphocytes (IBD: Δ = 0.36 × 103/μL), rather than to lower neutrophil numbers (Δ = –0.20 × 103/μL; P = .13) (Figure 13). With respect to CD4 T cell subsets, anti-TNF users had higher Th17, Th1Th17, EM CD4, and lower Th1 and CXCR3–CCR6– subsets frequencies (Figures 6A, B, D, and E and 12). Of these, the effect on Th1Th17 and CXCR3–CCR6– subsets was similar in CD and UC, while changes in Th1 and Th17 were UC specific, and increases in EM CD4 were much stronger in CD. Overall, anti-TNF use had a normalizing effect on the immune cell populations associated with IBD disease and activity, potentially reflecting the efficacy of anti-TNF therapy for IBD.

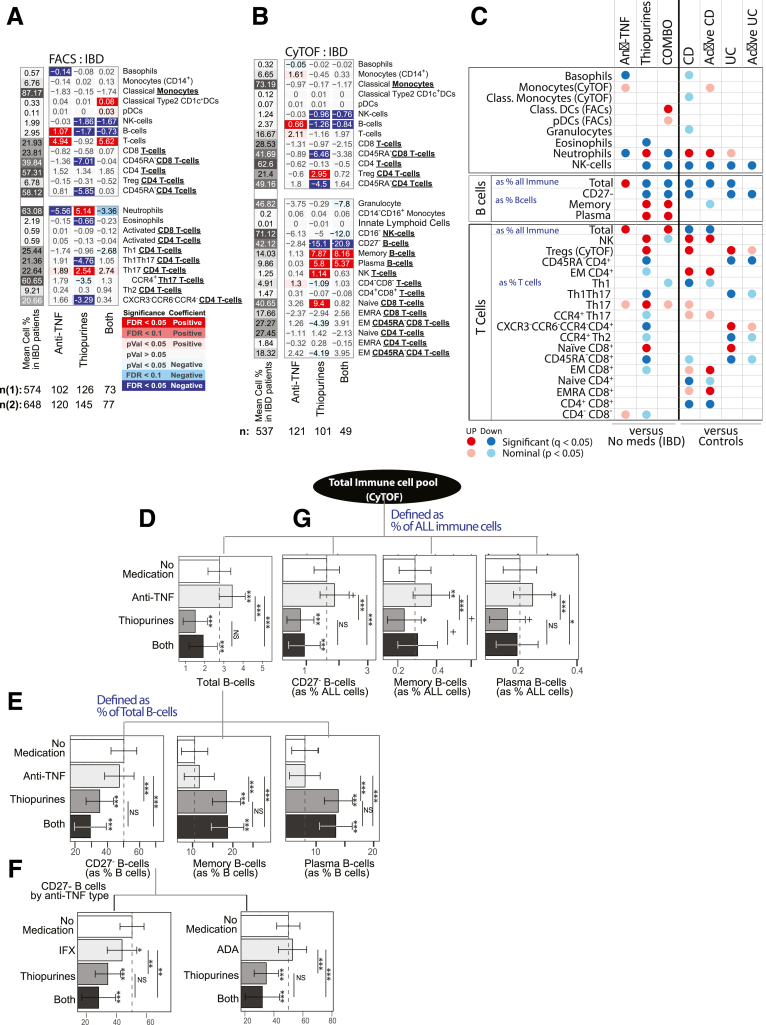

Anti-TNF and Thiopurine Combination Therapy Influences Major B Cell Subsets

A patient concomitantly using a biologic (eg, anti-TNF) and an immunomodulator, generally, does better clinically than a patient taking either of those medications alone (ie, monotherapy); however, the reason for this is uncertain. Our cohort included 77 patients, concomitantly using thiopurines and either infliximab or adalimumab, allowing us to investigate the immune cell effects under combination vs monotherapy (Figures 14A and B and 15A and B). First, no drug synergy was observed, as the cell type abundances measured in patients taking combined therapy did not significantly deviate from the effects associated with either drug taken independently. More often, the consequences of combination therapy on immune cell abundance appeared either additive or antagonistic such that the addition of one drug weakened or canceled out the effect of the other (Figure 14C). This was most evident for the total B cell pool (expressed as % All immune cells), which was increased with anti-TNF monotherapy, decreased with thiopurine monotherapy, and yet was still decreased with combination therapy, suggesting that the thiopurine antagonized and dominated the anti-TNF effects (Figure 14D and 15B). Neutrophils, in contrast, were significantly increased with thiopurine monotherapy, decreased with anti-TNF monotherapy, and yet remained decreased under combination therapy, suggesting that anti-TNF antagonized and dominated the thiopurine effects in this cell population.

Figure 14.

Immune cells association with anti-TNF and thiopurine monotherapy or combination therapy in IBD patients. Medication effect for anti-TNF and thiopurines alone or in combination in cell populations defined by (A) FACS and (B) CyTOF in IBD patients, considering the interaction between medications. (C) Summary of immune cell type associations by medication and disease type or activity, shown side by side to reflect when medication effect mimic or antagonize disease-immune cell associations. (D–G) estimated marginal means and 95% confidence intervals by medication use for CyTOF-defined B cells subsets as (D, G) % of all immune cells or (E, F) as % of all B cells. (F) Effect associated with infliximab or adalimumab. Asterisks atop the confidence intervals indicate significance level compared with patients not taking either medication, and asterisks atop connecting bars indicate comparisons intergroup medication (+P ≤ .1, ∗P ≤ .05,∗∗P ≤ .01,∗∗∗P ≤ .001).

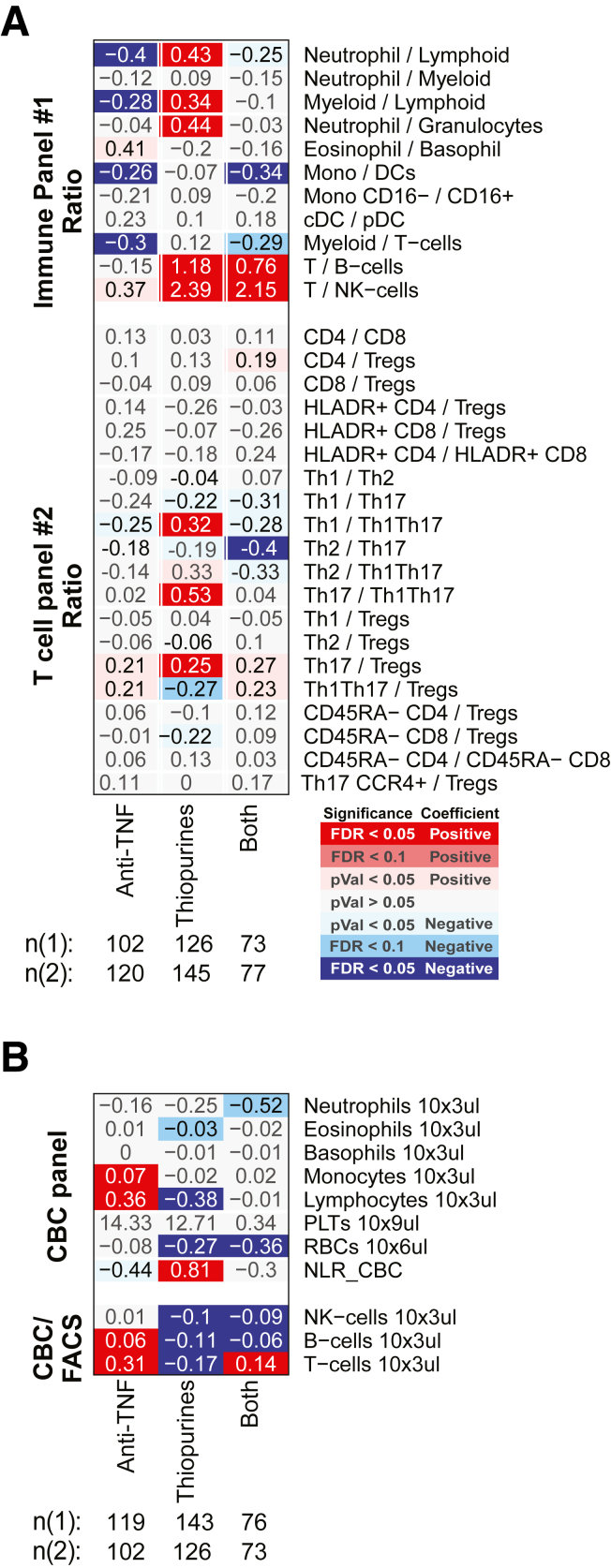

Figure 15.

Association of anti-TNF and thiopurine monotherapy or combination therapy in IBD patients for ratios between FACS-defined immune cell types and CBC. Medication effect for anti-TNF and thiopurines alone, or in combination, considering the interaction effect between the 2 medications. For each population a multivariate model including IBD disease, endoscopic activity, core covariates and anti-TNF/thiopurine interaction was fitted independently. Color and intensity indicate direction (red = positive, blue = negative) and significance of the association per medication (column) and cell frequency (row). Values shown represent the changes in the cell population frequency between the patients taking the medication alone or in combination vs patients not taking any. (A) The ratios between immune/myeloid panel 1 populations were analyzed in the total of 721 patients, and the ratios between T cell panel 2 were analyzed in the total of 809 patients. The distribution of patients taking the medications alone or in combinations is shown in the column descriptions below the plot, with the first value (n(1)) referring to analyses with the immune/myeloid panel 1 populations’ ratios, and the latter value (n(2)) referring to the analyses with T cell panel 2 populations’ ratios. (B) The analyses of CBC data (the top 8 rows) were done with a linear model without inclusion of technical FACS relevant variables in the total of 806 patients. The estimated concentration of lymphocyte populations, based on combination of CBC and FACS data, was analyzed with a full mixed model in the total of 720 patients. The distribution of patients taking the medications alone or in combinations is shown in the column descriptions below the plot, with the first value (n(1)) referring to the 8 CBC populations and the latter value (n(2)) referring to the analyses with the 3 estimated lymphocyte concentration measures.

Given the importance of B cells in the production of anti-drug antibodies (ADAs), a complication of anti-TNF monotherapy that impacts its efficacy,14 we evaluated further the effects of monotherapy and combination therapy on the individual B cell populations measured in our study. We first determined if, in addition to the reduction in the size total B cell pool, the proportions of the individual subtypes comprising the B cell pool were also affected by medication use. On the one hand, the use of anti-TNF monotherapy led to a higher frequency of all B cells (Figure 14E) without affecting the relative distribution of the measured B cell subsets (Figure 14F). On the other hand, thiopurine use, either alone or in combination with an anti-TNF, lowered the overall frequency of all B cells as well as drastically affected the relative distribution of all 3 measured B cell subsets. Compared with nonmedicated IBD patients the frequency of naïve CD27– B cells was decreased while the frequencies of both memory and plasma B cells increased correspondingly (Figure 14E). As shown in Figure 14F, differentiating anti-TNF medication by Remicade or infliximab showed very similar effects.

As the frequencies of the B cells defined as a fraction of all B cells are substantially complimentary to each other, in order to investigate which of the B cell subsets were driving the observed changes with thiopurine use, we reanalyzed the B cells defined as fractions of all immune cells, thus closer approximating the absolute changes in the B cell subsets. Compared with the nonmedicated group, anti-TNF monotherapy increased abundance of all 3 B cell compartments, while thiopurine monotherapy reduced abundance of the same 3 B cell compartments (Figure 14G). Compared with the nonmedicated group, however, patients on combination therapy showed significant reduction in the abundance of only the CD27– naïve B cell compartment (none = 0.95%, anti-TNF monotherapy = 1.28%; thiopurine monotherapy = 0.24%; both = 0.17%), without substantially affecting the abundance of either memory and plasma B cells (memory B cells: none = 0.17%, anti-TNF monotherapy = 0.26%; thiopurine monotherapy = 0.14%; combination therapy = 0.17%; plasma B cells: none = 0.13%, anti-TNF monotherapy = 0.17%; thiopurine monotherapy = 0.10%; combination therapy = 0.11%). Thus, monotherapy and combination therapies produce very different B cell phenomes.

Discussion

In this study, we associated 39 different blood immune cell populations with IBD diagnosis, subtype, clinical and endoscopic disease activity scores, Montreal classifications, disease duration, and medication use. Our goal was to provide a deeper meaning for the subclassifications and therapies which are the cornerstones of IBD clinical practice. Our study design enabled replication of a subset of our IBD associations not only in separate individuals but by a different platform, greatly enhancing the reliability of observations. Overall, our data support that while few immune cell types are commonly affected in IBD (lowered NK cells, B cells and CD45RA– CD8 T cells), generally the immunophenome is distinct between UC and CD. Within disease subtype, further distinction is also observed according to with behavior and location subphenotypes. For example, elevated EM CD4 and CD8 T cells observed with stricturing and penetrating CD and decreased naïve CD4 T cells associated with CD duration and number of surgeries. Finally, with respect to medication effects, thiopurine use appears as an immune hammer, influencing many cell types, often in the same direction as disease association, with anti-TNF use generally observed with an opposing pattern. Concomitant use of an anti-TNF and thiopurine was not synergistic but rather demonstrated either additive or antagonistic outcomes such that for some immune populations the addition of one drug either canceled out or overpowered the effect of the other. The total B cell pool was particularly impacted, increasing with anti-TNF and decreasing in thiopurine monotherapies, with the decrease dominating in the combination therapy.

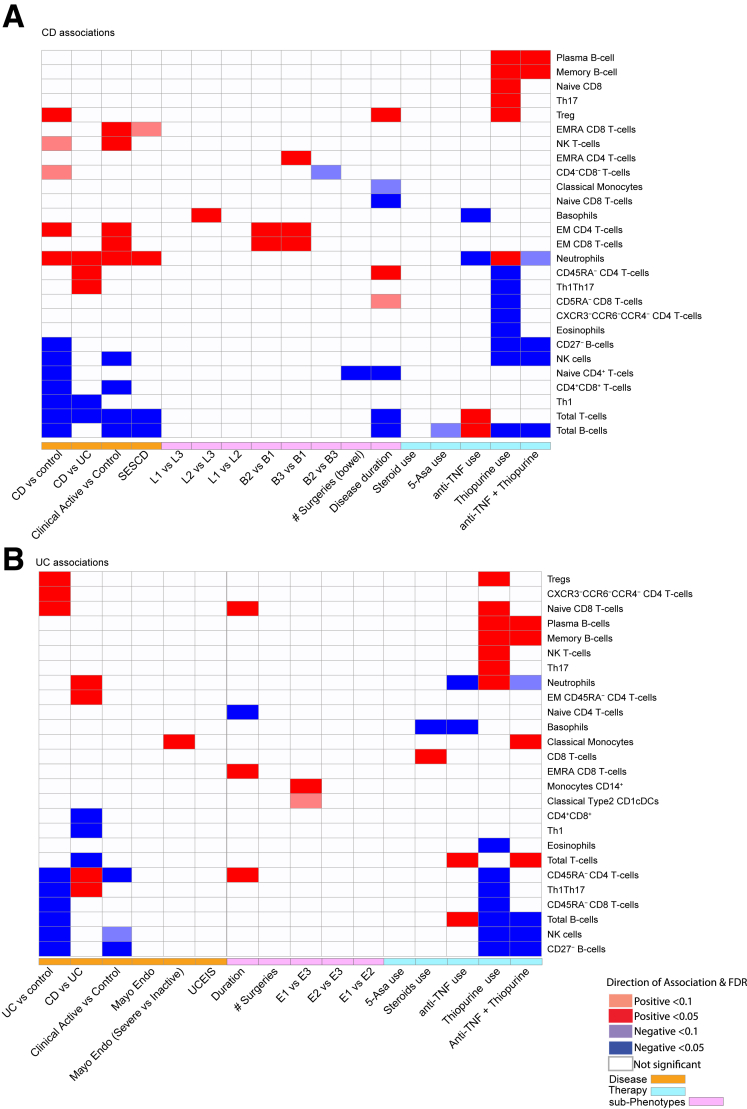

A summary of the key immune cell signatures we uncovered with respect to disease diagnosis (CD vs UC), state (flare vs remission), phenotypes (behavior and location), and medication use is provided in Figure 16. We present these observations as a resource for hypothesis generation of target cell types underlying manifestations of disease as captured by the individual subclassifications or subphenotypes that detail the dynamics or the different stages of disease, such as relapse and remission or colonic vs ileal. Given the number of observations, we prioritized discussion of results using a key attribute in our study, which was the ability to replicate our IBD-immunotype associations for 13 cell types in a separate cohort and measured by an alternative platform. Of these, the most reproduced alterations commonly observed in UC and CD relative to control subjects were decreased NK and total B cells, while elevated CD45RA– CD4-T cells and decreased total T cells reproducibly distinguished CD and UC subtypes.

Figure 16.

A summary of the key immune cell signatures uncovered with respect to disease diagnosis (CD vs UC), state (flare vs remission), phenotypes (behavior and location), and medication use. A heatmap plot of the prominent immune cell and (A) CD or (B) UC associations identified in the current study at FDR <0.05 or <0.1. Cell color indicates direction of association, with blue indicating negative and red indicating positive. Cell color intensity indicates significance of association with gray indicating nonsignificant observations and FDR >0.1. Various characterizations of disease activity are presented, including endoscopic scores (SES-CD for CD and MayoEndo for UC), clinical disease activity scored (HBI for CD and SCCAI for UC), disease duration, number of surgeries, and Montreal disease subclassifications (behavior and location for CD and extent for UC). Effect of key medications either in monotherapy or combination therapy is also shown.

Our results are generally consistent with previous reports implicating NK cells in IBD. While Samarani et al15 demonstrated increased levels of blood NK cells in treatment-naïve CD patients relative to control subjects, they did observe a reduction in specific blood NK subsets such as CD56bright CD16low. Furthermore, they demonstrated that blood NK cells were activated and generally more poised to migrate to the gut in treatment-naïve CD patients as compared with control subjects.15 As we observed reduced numbers of NK cells, independent of active inflammation (albeit in non–treatment-naïve UC and CD patients) this might suggest an increase in NK cell egress to the gut. NK cells may play a proinflammatory role, being a primary source of IFNγ, important in the skewing toward Th1 response. On the other hand, NK cells have anti-inflammatory roles, as they are critical for colitogenic T cell suppression, a disease-controlling role potentially explaining the negative association observed with IBD in our study.14,16,17 With respect to effects of medications, Yusung et al18 reported in a small cohort of CD patients and control subjects that thiopurine monotherapy exerts a proapoptotic effect on blood NK cells, consistent with its effect on other lymphocytes. We extend these observations by confirming that NK cells are significantly reduced in the blood of UC and CD patients relative to control subjects, are not influenced by anti-TNF monotherapy, and decreased in combination with a thiopurine. Overall, our observations support further investigation into potentially unappreciated beneficial or negative therapeutic action of these agents on NK cells in the context of IBD.

Elevated memory (CD45RA–) CD4T cells and decreased total T cells reproducibly distinguished CD and UC subtypes supporting that adaptive immune responses play a major role in the pathogenesis of IBD as well as where differences in subtypes might prevail.19 In particular, we observed that Th1Th17 cells were less frequent in UC patients than in control subjects or even in CD patients. This may be explained by increased extravasation to inflamed tissues of Th1Th17 cells which display gut homing and retention adhesion molecules.20 The Th1/Th17 and Th1/Th1Th17 subset ratios also differentiated CD from UC, suggesting that the balance between IL-17 producing subsets and Th1 cells is indeed relevant to IBD subtype pathophysiology. Thus our analysis is in line with reported increased levels of IL-17 in the inflamed mucosa and blood of IBD patients.21 Whether this cytokine is an effector or response to ongoing inflammation remains uncertain, especially given the observed failure of IL-17 blockade in CD.22

The most poorly replicated observation in our study was for Tregs, found to be significantly upregulated by CyTOF only, in CD and UC patients, both in remission or with active disease. The inconsistent frequency estimations by the 2 immunophenotyping methods is an important observation presented here especially since previous reports showed that patients with IBD exhibited reduced numbers of peripheral Tregs.23 Maul et al,5 however, reported increased peripheral blood Tregs in inactive CD patients, yet a contraction of the Treg pool during active disease, which confirms and contrasts, respectively, with the results of the present study. Finally, Mitsialis et al24 reported no difference in peripheral abundance of Tregs in IBD. In our benchmarking cohort, both methods defined them similarly (CD25highCD127low subsets of CD4 T cells); however, in CyTOF, automatic gating is influenced by all surface markers targeted by the panel (38 antibodies), while with FACS gating it is defined exclusively by selected markers at each step. Because more information is actually being used under the hood to define the CyTOF populations (which is part of the advantage) a head-to-head comparison may be very challenging after all. Overall, it cautions that the determination of certain population frequencies in large-scale studies may still be suboptimal either because the use of identical markers by different technologies may not readily reproduce or insufficient panel sizes limiting cell type identification and thus demonstrates potentially extra challenges in the development of a Treg targeting therapy for CD.25

The total B cell pool and the immature CD27– B cells (primarily transitional CD38+B cells) subsets stood out as a key distinguishing cell type, as they were reduced in CD and UC patients vs control but could also differentiate active UC from active CD. A similarly defined transitional B cell was also found in an independent study26 to be decreased in blood of UC relative to healthy control subjects as well as distinguishing from CD; however, they were not significantly different between CD and healthy control subjects.26 In the present study, in addition to a reduction in CD27– B cells in CD vs control comparisons, we observed a nominally positive association with ileocolonic (L3) vs ileal (L1) or colonic (L2) CD. Whether these regional associations of CD27– B cells support differences in inflammatory processes ongoing in large vs small intestine is of interest. Other regional anomalies with respect to B cells were previously reported with IgA-expressing plasma B cells emerging from gut lymphoid germinal centers preferentially migrating to the small intestinal lamina propria compared with large intestine.27 Overall, our observations are fitting with the recent re-evaluation of the contribution of the B cell compartment in IBD. In particular, whether B cell targeting is part of any therapeutic armamentarium in IBD, which we address next.28

The Study of Biologic and Immunomodulator Naive Patients in Crohn Disease (SONIC) trial has shown that higher proportions of patients treated with anti-TNF (infliximab) and a thiopurine immunomodulator (eg, azathioprine [AZA]) achieve efficacy endpoints superior to anti-TNF monotherapy.29 However, among CD patients with similar serum concentrations of infliximab, combination therapy with AZA was not significantly more effective than infliximab monotherapy.30 This suggested that AZA, may in part, improve efficacy in combination therapy by increasing pharmacokinetic features of infliximab. This was, however, a post hoc analysis and did not exclude other potential hypotheses such as synergistic mechanisms of actions of the 2 drugs. A previous report of a thiopurine-driven reduction of the naïve (CD27–IgD+CD38–) and transitional (CD27–IgD+CD38+) B cells31 supported the improved pharmacokinetic hypothesis, as the authors suggested these cell types may reduce the potential for ADA generation. However, their analysis included only thiopurine monotherapy users. We find that anti-TNF monotherapy increases the circulating pool of B cells, including plasma B cells, memory and CD27–, relative to the nonmedicated IBD group. When combined with a thiopurine, however, the effect of anti-TNF on both memory and plasma B cell levels was negated, such that the levels were comparable to the nonmedicated IBD group. However, the pool of naïve/transitional CD27– B cells is also reduced to levels even lower than in the nonmedicated IBD group. As B cells are responsible for antibody production, this may suggest that thiopurine co-treatment with anti-TNF improves outcome by reducing the pool of naïve B cells capable of maturation into ADA-generating plasma cells upon de novo exposure to biologics. However, B cells may also have an inherent role in the disease process, such that co-use of thiopurines could provide a complimentary anti-IBD mechanism to anti-TNF therapy.28 If the reduced risk of ADA development with thiopurines is indeed responsible for increased anti-TNF efficacy, an alternative therapeutic approach may be to combine anti-TNF with a more narrowly acting medication, specifically affecting B cells rather than with broad acting immunosuppressants such as thiopurines. As immunomodulators do carry various additional risks including lymphomas, hepatoxicity, and cytopenias, this outcome would be clinically appealing. Furthermore, we would advocate that the sequencing of thiopurine use relative to biologics might also be important.

While we present the largest study of immunophenotyping of IBD patients to date, which constitutes an invaluable data resource for further studies, our study has limitations. As our control subjects were on average older than CD and UC patients, we included age as a covariate, potentially ameliorating the disease signal. The available medication information is not sufficiently detailed to address missing outcomes, dose, or length of use. Our focus is limited only to targeted immune cell subsets given limited space for antibodies in the utilized panels, and tuning of antibody panels for specific investigations may be critical.32 We show that immune cell types are altered under pharmacological conditions, which emphasizes medication use as not only highlighting potential mechanisms of drug action, but also as a potential confounding effect in research studies, not specifically addressing their effects. As such, a general conclusion for all human immunophenotyping studies is to consider medication use, as well as gender, age, and ancestry information as covariates.

Materials and Methods

Patient Cohort, Phenotypic Information, and Patient and Public Involvement

Patients from The Mount Sinai Health System were recruited and gave written informed consent to be a part of the MSCCR under an Institutional Review Board–approved protocol (MSBI IRB #088-15). Patients (>18 years of age) were enrolled during their standard of care colonoscopy visit while non-IBD control subjects were undergoing colon cancer screening (Figure 1A). One hour before their colonoscopy blood samples were collected and only a single time point was sampled per patient.

Measures of the IBD disease state were obtained from the clinical and endoscopic observations of the patient at the time of endoscopy. Endoscopic activity was measured by the SES-CD for CD patients. It includes the following components: the presence and type of ulcers (presence), extent of ulcerated surface (extent), extent of affected surface (affected), and presence and severity of narrowing or stenosis (narrowing), with 4 levels per measure available from 5 ileocolonic regions: ileum, right/ascending, transverse and left/descending/sigmoid colon, and rectum.33 In addition to the use of the total combined SES-CD score, and scores per measure and per region, we also used the SES-CD to classify CD severity as inactive (SES-CD 0–2), mild (SES-CD 3–6), moderate (SES-CD 7–15), and severe (SES-CD ≥16).34

For UC patients, endoscopic measurements of the disease activity comprised the MayoEndo and UC Endoscopic Index of Severity (UCEIS). In the first measure, MayoEndo, UC patients are categorized into 4 categories: 0 = with normal or inactive disease; 1 = with mild disease (erythema, decreased vascular pattern); 2 = with moderate disease (marked erythema, absent vascular pattern); and 3 = with severe disease (spontaneous bleeding, ulcerations). UCEIS is a more recent measure of endoscopic activity in UC patients,35 combining vascular pattern (3 levels), bleeding (4 levels), and erosions (4 levels) in a continuous score, which can be used to classify patients with inactive (0 or 1) or active (≥2) disease.36 MayoEndos were determined for UC patients. Endoscopic activity was categorized as inactive (MayoEndo = 0 for UC), mild (MayoEndo = 1), moderate (MayoEndo = 2), and severe (MayoEndo = 3).34

We also included CD and UC disease activity measures based on clinical observations (HBI and clinician-based SCCAI, respectively). The Montreal classification age categories (A1 = <17 years, A2 = 17–40 years, A3 = >40 years) for CD, and disease duration (<2, 2–5, >5) for UC and CD were included.

Current medication use was based on self-reported information for 32 medications. These included antibiotics, oral mesalamine, rectal mesalamine and sulfasalazine (combined into “mesalamine”), infliximab and adalimumab (“anti-TNF”), certolizumab and golimumab (not included as “anti-TNF” due to the difference in structure/action and low numbers, respectively), natalizumab and vedolizumab (“anti-Integrin”), thiopurines (mercaptopurine/6-MP/Purinethol and/or azathioprine/AZA), corticosteroids, and others.

Sample Processing for Flow Cytometry

Whole blood immunophenotyping was performed on the freshly collected peripheral blood in an ACD vacutainer within 3 hours of collection to ensure the integrity of the sample and minimize artifacts. For polychromatic flow cytometry, 200 μL of blood was placed in a 1 mL deep 96-well plate and was stained with antibody cocktails that comprise 2 panels (Table 2). Antibody cocktails were used within 1 month of preparation or for up to approximately 35 samples (whichever comes first) to minimize the effects of instability of tandem dyes over time, with 42 batches in total, made for both immune/myeloid panel 1 and T cell panel 2 at the same time. We assessed the presence of batch effect and order within a batch, and determined that the batch was an important factor included in all analyses. Cells were then subjected to red blood cell lysis incubation for 10 minutes and washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline. Cells were resuspended in 300 μL of phosphate-buffered saline and acquired on a flow cytometer (BD LSR II Fortessa; Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) at the rate of 3000–5000 events/s. In addition to the antibody batch, a flag for whether the samples were processed on Flow Cytometer the same day as they were stained was incorporated in all analyses with FACS-derived data.

Table 2.

FACS-Based Cell Population Summary (Panels 1 and 2)

| Panel 1: Immune/myeloid cellsa | Control (n = 147) | CD (n = 346) | UC (n = 228) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neutrophils (SSC-Ahigh CD16+) | 58.83 (50.75, 60.48, 66.18) | 64.08 (57.38, 64.24, 72.03) | 61.56 (53.45, 61.85, 68.54) |

| Eosinophils (SSC-Ahigh CD16–) | 2.36 (1.24, 2.00, 2.99) | 2.08 (0.90, 1.53, 2.64) | 2.35 (0.92, 1.74, 3.25) |

| Basophils (CD123+, HLA-DR–) | 0.64 (0.42, 0.58, 0.86) | 0.54 (0.29, 0.48, 0.69) | 0.63 (0.33, 0.60, 0.81) |

| Monocytes (CD14+) | 6.74 (5.31, 6.57, 7.75) | 6.63 (4.97, 6.44, 7.96) | 6.96 (5.33, 6.88, 8.35) |

| Classical monocytes (CD14highCD16low) | 85.94 (82.11, 87.08, 90.68) | 86.95 (83.35, 87.47, 92.52) | 87.49 (83.87, 88.42, 92.32) |

| Classical DCs (CD1c+) | 0.37 (0.25, 0.32, 0.43) | 0.32 (0.20, 0.29, 0.40) | 0.34 (0.21, 0.29, 0.42) |

| Plasmocytoid DCs (CD123+) | 0.10 (0.05, 0.08, 0.12) | 0.11 (0.05, 0.09, 0.14) | 0.11 (0.05, 0.09, 0.14) |

| NK cells (CD56+) | 3.32 (1.87, 2.88, 4.51) | 1.96 (0.70, 1.67, 2.80) | 2.04 (0.81, 1.59, 2.90) |

| B cells (CD19+) | 4.06 (2.61, 3.91, 5.29) | 3.03 (1.30, 2.45, 4.27) | 2.82 (1.50, 2.50, 3.78) |

| T cells (CD3+) | 23.46 (17.54, 22.04, 27.93) | 21.20 (14.76, 20.40, 26.87) | 23.05 (17.51, 22.52, 27.29) |

| Panel 2: T cell subsetsb | (n = 161) | (n = 386) | (n = 262 |

|---|---|---|---|

| CD8 T cells (CD3+ CD8+) | 24.12 (15.69, 22.02, 31.08) | 23.80 (15.27, 22.85, 30.53) | 23.83 (16.03, 22.65, 31.83) |

| Activated CD8 (HLA-DR+) | 0.72 (0.29, 0.49, 0.95) | 0.60 (0.13, 0.35, 0.82) | 0.57 (0.17, 0.38, 0.76) |

| Memory CD8 (CD45RA–) | 46.30 (35.76, 43.65, 55.41) | 40.44 (27.14, 40.78, 52.03) | 38.96 (26.86, 37.96, 49.34) |

| CD4 T cells (CD3+ CD4+) | 60.78 (52.43, 64.38, 72.70) | 56.10 (43.28, 59.68, 68.89) | 59.10 (49.20, 61.79, 71.31) |

| Tregs (CD3+ CD25++ CD127int) | 7.04 (5.48, 7.17, 8.23) | 6.97 (5.43, 6.85, 8.48) | 6.50 (4.90, 6.23, 7.80) |

| Activated CD4 (HLA-DR+) | 0.69 (0.20, 0.46, 0.82) | 0.62 (0.13, 0.32, 0.74) | 0.53 (0.13, 0.30, 0.63) |

| Memory CD4 (CD45RA–) | 67.45 (56.46, 67.68, 80.50) | 60.06 (48.43, 60.17, 72.69) | 55.27 (43.38, 55.94, 66.81) |

| Th1 (CXCR3+ CCR6–) | 26.56 (20.43, 24.63, 32.06) | 24.35 (16.85, 21.84, 27.97) | 27.05 (19.48, 24.92, 31.68) |

| Th1Th17 (CXCR3+ CCR6+) | 21.33 (15.50, 20.77, 26.72) | 23.17 (16.83, 22.64, 28.72) | 18.69 (12.32, 18.16, 23.92) |

| Th17 (CXCR3– CCR6+) | 21.33 (16.96, 20.32, 25.32) | 23.47 (17.59, 23.58, 30.37) | 21.43 (16.16, 21.07, 27.16) |

| CCR4+ Th17 | 57.61 (48.62, 60.26, 69.89) | 61.75 (53.97, 63.62, 72.27) | 59.04 (49.79, 60.29, 70.16) |

| Th2 (CCR4+CXCR3– CCR6–) | 10.86 (7.40, 10.76, 14.22) | 9.13 (5.81, 8.41, 11.59) | 9.31 (6.19, 8.80, 11.88) |

| CCR4–CXCR3– CCR6-CD+ | 19.23 (12.85, 17.03, 23.17) | 19.26 (12.52, 16.53, 23.27) | 22.73 (14.53, 20.43, 29.19) |

NOTE. Values are mean (25% quantile, median, 75% quantile).

CD, Crohn’s disease; DC, dendritic cell; NK, natural killer; Treg, regulatory T cell; UC, ulcerative colitis.

Population frequency is defined as fraction of all live cells except for the indented population (ie, Classical monocytes) which are defined as % of the parental population (ie, Monocytes).

Population frequency is defined as fraction of all CD3+ T-cells except for the indented population (ie, Activated and Memory CD8) which are defined as % of the parental population (ie, CD8 T-cells).

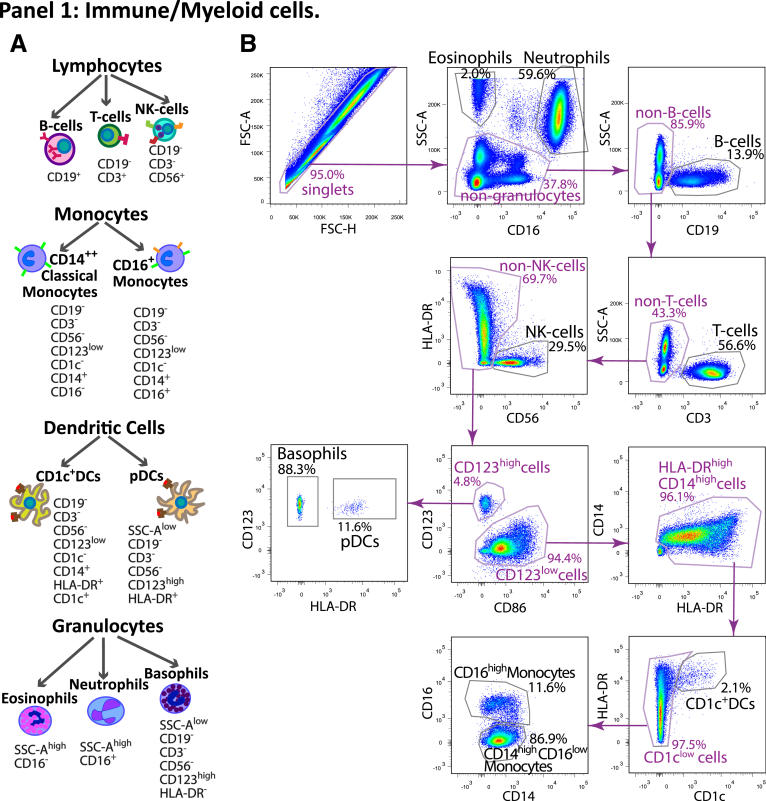

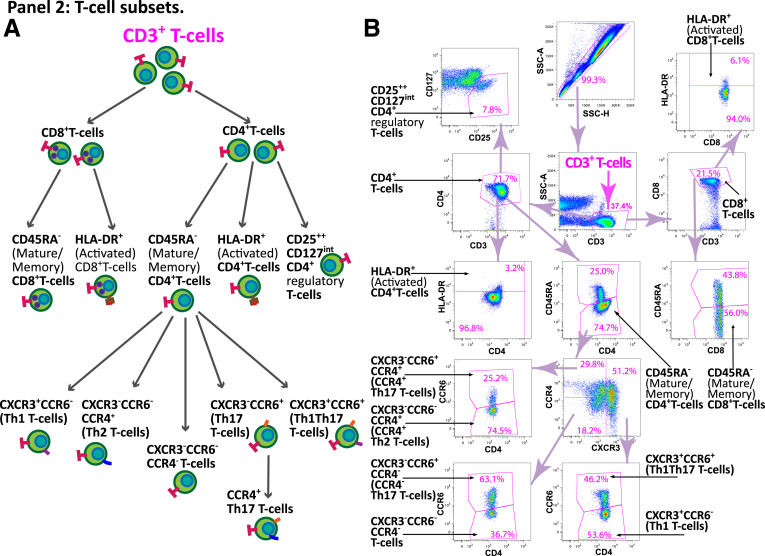

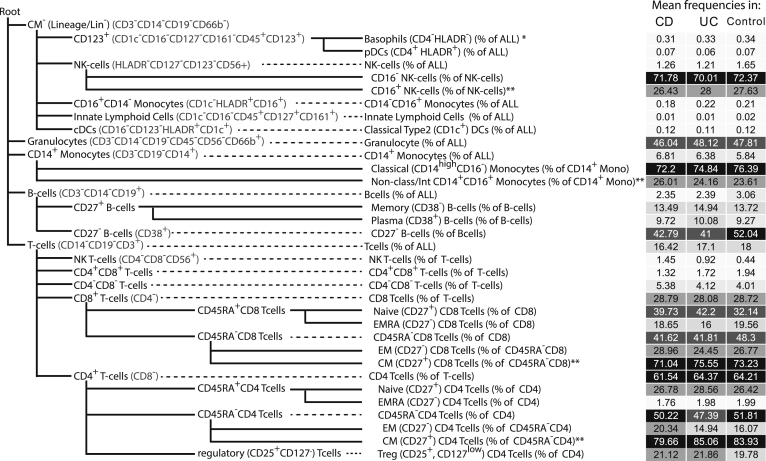

The cell populations tested in the study are illustrated in Figure 17 and 18. Panel 1 included 10 surface markers (CD45, CD1c, CD3, CD14, CD16, CD19, CD56, CD86, CD123, and HLA-DR), and focused on general immune cellular compartments, including the main lymphoid cell types (T, B, and NK cells), granulocytes (neutrophils, eosinophils, and basophils), and myeloid subsets (CD14hi CD16lo classical monocytes, CD14lo CD16hi nonclassical monocytes, CD1c+ classical DCs, and CD123+ plasmocytoid DCs) (Figure 1B). The Human Immune Monitoring Core at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai has developed an automated gating approach for this panel described below. First, cells in FACS files for 29 samples were manually gated into 10 cell subsets as described previously, and an additional subset of immune cells that did not belong into any of the other subsets in Figure 17. The manually gated cells were exported from FlowJo (FlowJo, version 10.0, Ashland, OR) into separate FCS file, loaded into R version 3.5.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) using the Bioconductor flowCore package. Only cells that were gated into one of the subsets were used in subsequent analysis. Second, 200,000 cells were randomly subsampled from all of the files and were used for training the classifier. The subsampling was not uniform: rare subsets such as eosinophils, basophils, nonclassical monocytes, and both DC subsets were not subsampled in order to enrich the training subset for them. Third, we fit a random forest classifier (randomForest R package) to the training data, using the default model parameters except for ntree = 100. The samples with predicted accuracy over 0.97 were retained for analyses. Panel 2 (T cell subset panel, Figure 18) is a focused 11-color panel for CD45, CD45RA, CD3, CD4, CD8, CD25, CD127, CCR4, CCR6, CXCR3, and HLA-DR surface markers. This panel aims to identify memory Th1, Th2, and Th17 cells based on their chemokine receptors of CCR4, CCR6, and CXCR3 as well as CD45RA. Tregs were defined by CD25 and CD127 together with CD45RA, and HLA-DR expression represented T cell activation status for the qualitative information. T cell subsets were identified by manual gating by the same technician for all samples in Figure 18.

Figure 17.

Immune panel 1 gating map. (A) Schematic representation of the populations defined in panel 1 with the surface markers defining each subset. (B) An example of the FACS gating for the panel 1 from a representative sample in the study.

Figure 18.

T cell panel 2 gating map. (A) Schematic representation of the populations defined in panel 2 with the surface markers defining each subset. The diagram indicates the hierarchy utilized in measuring the frequency of each T cell subset, where the frequency of each subsets is defined in relation to each parental subset. (B) An example of the FACS gating for panel 2 from a representative sample in the study. CD3+ cell subset, which is the starting point for all populations defined in panel 2.

For panel 1, immune subset frequencies are expressed as a % of total gated immune cells except for classical monocytes (CD14+ CD16–) which were defined as % of the total of CD14+ monocytes. For the T cell subsets from panel 2, the frequency is defined as percentage of the parental population (based on the gating strategy) (Table 2 and Figure 18). Because we defined subsets of CD4 and CD8 T cells according to the level of CD45RA expression, the frequencies of CD45RA+ and CD45RA– CD4 and CD8 T cells were complimentary to each other: the r2 for CD4+CD45RA+ and CD4+CD45RA– T cells is –0.99 and the r2 for CD8+CD45RA+ and CD8+CD45RA– T cells is –0.96. To reduce the penalty for correction for multiple testing, we retained only CD4+CD45RA– and CD8+CD45RA– T cells (representing predominantly memory T cells) for the following analyses, with the interpretation that CD4+CD45RA+ and CD8+CD45RA+ (representing predominantly naïve T cells) populations would have identical, or nearly identical significance estimations, and the effect size of similar magnitude but of opposite direction. Similarly, the frequencies of nonclassical monocytes (CD14+ CD16+) are complimentary to the frequencies of classical monocytes (CD14+ CD16–) in panel 1.

Cell populations from the CBC panel are presented as the numbers of cells per volume unit of blood (103/μL for neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, eosinophils and basophils, 106/μL for red blood cell count, and 109/μL for the platelet count). We also estimated the concentration of T, B, and NK cells from the total concentration of lymphocytes using flow cytometry–derived relative frequency of each of these cell types from the combined fraction of the 3 cell types. These estimated concentrations of the lymphocyte populations are included with the CBC panel analyses.

In addition to subset frequencies and concentration, we analyzed the ratios between selected immune populations or T cell subsets (Tables 3 and 4), which was log-transformed for the analyses. The neutrophil-to-leukocyte ratio (NLR)37 was calculated from FACS cell frequencies and from CBC concentration values. As part of quality control, any measures more than 6 SDs from the mean were excluded from the analyses for both flow cytometry and CBC panels.

Table 3.

FACS-Based Cell Population Ratio Summary

| Ratios between panel 1 subsetsa | Control (n = 147) | CD (n = 346) | UC (n = 228) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neutrophil/lymphoid | 2.26 (1.39, 2.05, 2.74) | 3.18 (1.83, 2.51, 4.05) | 2.79 (1.62, 2.23, 3.18) |

| Neutrophil/myeloid | 9.25 (6.75, 8.44, 10.5) | 11.9 (7.10, 9.32, 12.5) | 10.5 (6.47, 8.34, 10.9) |

| Myeloid/lymphoid | 0.26 (0.19, 0.24, 0.30) | 0.33 (0.19, 0.26, 0.39) | 0.30 (0.20, 0.27, 0.36) |

| Neutrophil/granulocytes | 29.3 (14.0, 21.4, 35.3) | 44.7 (18.6, 30.2, 49.4) | 45.9 (14.9, 24.5, 43.3) |

| Eosinophil/basophil | 11.1 (2.22, 3.38, 5.44) | 11.3 (1.87, 3.55, 6.05) | 11.6 (1.66, 3.60, 6.39) |

| Mono/DCs | 16.4 (11.7, 15.4, 19.9) | 18.6 (12.2, 16.3, 22.0) | 19.6 (12.6, 16.1, 22.7) |

| Mono CD16–/CD16+ | 8.25 (4.59, 6.74, 9.72) | 12.5 (5.01, 6.98, 12.4) | 14.0 (5.20, 7.64, 12.0) |

| CD1C+ cDC/pDC | 9.47 (2.54, 3.87, 6.46) | 9.89 (1.91, 3.10, 5.50) | 8.02 (2.09, 3.50, 5.71) |