Abstract

Cannulation is not only one of the most common medical procedures but also fraught with complications. The skill of the clinician performing cannulation directly impacts cannulation outcomes. However, current methods of teaching this skill are deficient, relying on subjective demonstrations and unrealistic manikins that have limited utility for skills training. Furthermore, of the factors that hinders effective continuing medical education is the assumption that clinical experience results in expertise. In this work, we examine if objective metrics acquired from a novel cannulation simulator are able to distinguish between experienced clinicians and established experts, enabling the measurement of true expertise. Twenty-two healthcare professionals, who practiced cannulation with varying experience, performed a simulated arteriovenous fistula cannulation task on the simulator. Four clinicians were peer-identified as experts while the others were designated to the experienced group. The simulator tracked the motion of the needle (via an electromagnetic sensor), rendered blood flashback function (via an infrared light sensor), and recorded pinch forces exerted on the needle (via force sensing elements). Metrics were computed based on motion, force, and other sensor data. Results indicated that, with near 80% of accuracy using both logistic regression and linear discriminant analysis, the objective metrics differentiated between experts and the experienced, including identifying needle motion and finger force as two prominent features that distinguished between the groups. Furthermore, results indicated that expertise was not correlated with years of experience, validating the central hypothesis of the study. These insights contribute to structured and standardized medical skills training by enabling a meaningful definition of expertise and could potentially lead to more effective skills training methods.

Keywords: Medical simulation, Skill assessment, Objective metrics

Introduction

Cannulation is a prevalent medical procedure, for instance, in intravenous or hemodialysis vascular access. As such, there are millions of cannulations performed every year across the world. However, the success rate of clinicians safely and effectively performing cannulation is relatively low. Studies report that nurses have a first-time success rate of as low as 44%9. In hemodialysis, minor infiltration injury occurs in approximately 50% of all attempts while 5-7% of insertions result in significant complications that require hospitalization18,22. As a result, ineffective cannulation has a significantly negative impact on clinical and financial outcomes15.

One of the most critical factors that influence successful cannulation is the skill of the clinician. Studies indicate that experienced nurses have better cannulation outcomes, including positive patient experiences13. However, current methods of training for cannulation are rudimentary. Most nursing and medical schools utilize hand manikins with fluid-filled tubes for student practice. However, these tools have limited usability since they are unrealistic and do not provide objective feedback for training. Nurses and phlebotomists sometimes also practice on each other during training, raising important ethical concerns. Consequently, there is a need for better training methods for cannulation.

Recent innovations in hardware and software technologies have enabled the creation of smart simulators for medical training. The latest technological tools can not only enable three dimensional (3D) visualization of complex vasculature26, but also facilitate training and/or rehearsal of a medical procedure. With the addition of virtual reality, dynamic haptic feedback, and 3D graphics, state-of-the-art tools are being developed for providing objective metrics-driven medical education19,23,31,34. Several studies in multiple medical domains point to the efficacy of such simulators for skills training and assessment1,10,24. Simulators often feature sensors (e.g., motion, force, video) to capture aspects of the clinician’s performance in a controlled nonclinical environment. Following this (or, in some cases, during performance), sensor data is used to compute objective metrics to quantify skill. These types of metrics, a useful supplement to the traditional apprenticeship model of medical training, have been demonstrated as useful for medical skills development3,11. Due to simulator-based training’s standardization and structure, many medical specialties have incorporated metrics-based credentialing for practice27.

The prevailing paradigm for skill assessment is based on a simulator’s ability to differentiate between expert and novice skill levels. However, a key assumption made in such studies is that experience is synonymous with expertise. Some recent studies, however, indicate that this assumption may not be well-founded. Fahy and colleagues compared three different classification schemes for clinical expertise, including number of cases, self-assessment, and video-assessment, among 105 participants who were asked to perform a suturing task on a laparoscopic simulator8. Results indicated that video-assessment was marginally better than the traditional scheme in discerning levels of expertise. In addition, participants’ self-assessment of expertise was not accurate. Thus, the definition of what constitutes expertise in clinical skill needs is important since patient outcomes are closely related to clinical skill. There has also been recent research that demonstrates that simulators are able to distinguish between various levels of clinical experience. Kil and colleagues used motion and force sensors to track the hand motion and force of attending surgeons and residents in a suturing training task with metrics successfully differentiating between these two finer levels of skill16. Metrics-based skill evaluation was also investigated through comparing hand motion of attending surgeons and residents, using motion tracking (via trajectories of needle movement) and video assessment5,6,28. One recent study revealed that even among experts, different skill levels can be identified through objective metrics12. Methods such as principal component analysis (PCA), crowdsourcing classifiers, and neural networks, have been proven to be effective in distinguishing expertise at various levels3,11,12. Such work highlights the fact that skill is on a continuum and methods that objectively quantify expertise based on performance (and not solely on indicators like experience) may be helpful in defining expertise.

A paradigm that does not conflate expertise with experience will contribute towards medical personnel training that is based on a more objective criteria for skill. Accordingly, the central goal of this study is to examine if simulator-based metrics can differentiate between true experts and experienced cannulators. This work builds upon our previous work that quantified novice cannulators as they performed simulated hemodialysis cannulation20,35 Results indicated the viability of our metrics for skill assessment. This work also addressees a pressing need for training tools specifically for hemodialysis cannulation. Currently used simulators are “low-tech” arm manikins, intended for intravenous cannulation training, only sometimes adapted for hemodialysis scenarios. However, the utility of these manikins is severely limited since they provide no objective metrics for training, nor do they include dialysis-specific vasculature2,14,34 Consequently, in this work, we examine whether simulator-based metrics can successfully differentiate between the fine-grained skill levels of individuals with varying levels of experience. As a potential consequence of this study, a metrics-based definition of expertise will advance a culture of excellence in medical education, positively impacting patient outcomes.

Materials and Methods

Simulator Structure

A custom designed cannulation simulator was designed for this study consisting of three primary components: simulator hardware, sensing systems, and a control unit. The simulator body is a 3D printed frame that allows it to be rotated 360°. There are four cannulation modules on each side of the rotatable frame as shown in Figure 1. Each cannulation module is filled with foam to simulate body mass. Fistula models with distinct geometric properties made of silicone gel (Ecoflex, Smooth-On Inc.) were placed within the foam. There were four fistulas with the following properties (straight/curved and diameter): the first fistula was straight with a diameter of 9mm; the second was straight with a diameter of 7mm; the third was curved with a diameter of 9mm; the fourth was also curved with a diameter of 7mm. Per the National Kidney Foundation’s Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (KDOQI) guidelines, “The mean diameter of the femoral vein is sufficient for effective cannulation (i.e., 7 mm)”22.

Figure 1:

Cannulation Simulator

(1) Frame; 2) Left-side holder; 3) Right-side holder; 4) Artificial skin; 5) Fistula model; 6) Vibration motor; 7) Infrared (IR) emitter array; a) Simulator body; b) Aurora field generator; c) FingerTPS sleeves; d) Leap Motion camera; e) Cannulation needle; f) Support structure for hanging Leap Motion camera on top of the simulator)

Within each fistula model, a vibration motor (Model 308-107, Precision Microdrives, Ltd.) was embedded to render feedback for palpation. By controlling the power and frequency of the vibration, the characteristic “thrill” haptic sensation of blood flow in an AVF is simulated. A Leap Motion sensor was attached to a pole 28cm above the cannulation platform to capture subjects’ hand movements during palpation. Furthermore, the FingerTPS force recording system was also used to record forces exerted on the surface during palpation. Three finger sleeves were placed on the user’s thumb, index finger, and middle finger since these three fingers are most used during cannulation. In addition to the motor, an Infrared (IR) emitter-detector system (APT1608F3C, Kingbright; 0603 SMT Victory Electronics Co. Ltd) was embedded inside the fistula to identify whether the needle was inserted into the fistula model. Based on the IR detector’s voltage, a red LED would light up to mimic the blood flashback during clinical cannulation. On top of the foam and fistula model, a layer of artificial skin (2mm thick; Ecoflex, Smooth-On Inc.) was placed. To track the motion of the needle throughout the cannulation process, an electromagnetic (EM) tracking system (Aurora, Northern Digital Inc.) is used. The sensor was fixed inside a 15G dialysis needle, with the field generator facing the cannulation platform for motion capture35. A web camera was placed outside of the simulator area to record the cannulation process for review.

The control unit was the wiring interface for the electronics in addition to house an Arduino Uno to control the frequency and power of the vibration motor, an amplifier, and a comparator for the IR system. All sensor data were captured and time-synchronized through custom code written in C++ (Visual Studio 2013) and OPENCV library (v. 3.0). The timestamps of each tracking system were recorded based on CPU time21.

Data Segmentation

For detailed quantitative analysis of skill, we sought to identify the two primary subtasks of cannulation: needle puncture to flashback and flashback to completion. For this, we first cropped the data to include only the cannulation process. This was done by checking the voltage of the IR detector combined with readings of finger force sensors. We defined the starting point of the cannulation process (tstart) by the moment that the IR detector’s voltage started to rise from the baseline. Since ambient light contains a certain amount of IR, when the needle touches the artificial skin layer the ambient light is largely blocked and the voltage readings rise above the baseline as shown in Figure 2. The end of the cannulation process (tend) was defined by the moment when finger pinch forces dropped below 0.2. Since each participant uses a different range of force to hold the needle, it would not be meaningful to compare the raw force data in Newtons across the participants. Therefore, we normalized forces between the range of 0 and 1. Accordingly, all force data reported in this paper is normalized.

Figure 2:

An Example of Data Sequences within One Trial

Further, when the needle punctures through the fistula model, the IR detector inside the needle receives a higher dose of IR due to the IR emitter array, and the corresponding voltage exhibits a significant drop. This time instant is denoted as tflash. (This is not the case if the needle is misplaced in the foam since there is negligible IR exposure). Based on this discrete change in the IR detector voltage, this cannulation process is split into two phases: Phase I (from the start until flashback) and Phase II (from flashback until the end) as illustrated in Figure 2.

Definition of Metrics

To explore the differences in skill between the expert and experienced group objectively using sensor data, we define the following four metrics:

- Time Span (TS) (s): The Time Spans in Phase I and Phase II are defined as:

(1) - Path Length (PL) (mm): Path Length is calculated by the length of the needle trajectory recorded by the Aurora system in Phase I and II as:

where nstart, nflash, and nend are the frame indices of tflash, tend and tend respectively.(2) - Force Intensity (FI): Clinicians often use their index finger and thumb to hold the wings of needles to perform procedures. However, to minimize the variability in the magnitudes of force applied across subjects, we calculated the average force values of three fingers within each trial and chose the one that had the highest value as the reference finger force. Force Intensity is calculated by:

where FII and FIII are the force intensity values of Phase I and II and fref is the reference finger force. This metric is unitless since fref is normalized.(3) Needle Angle (NA): The EM tracking system provides both the 3D spatial location and the 3D orientation of the sensor. We calculated the directional vector of the sensor, which was aligned with the needle itself and the normal vector of each cannulation area. Using these two vectors, the angle between the needle and the skin surface during each trial was calculated according to Figure 3. The needle angle (in both Phase I and II) was estimated by finding the average value of needle angles during that phase.

Figure 3:

Needle Angle Calculation

Experimental Design and Protocol

Ethics approval for this study was obtained from the Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) at Prisma Health and Clemson University. Twenty-two participants who were practicing nurses and dialysis technicians attending a national vascular access conference were recruited for this study. Among these, four participants were peer-recognized as experts in hemodialysis cannulation. For skill analysis, the participants were divided into two groups: the expert group consisted of the four peer-recognized experts, while the experienced group included the rest of the participants. Upon arrival and receiving informed consent, each participant completed a questionnaire that collected data regarding years of experience, cannulation frequency per month, and self-evaluation on their cannulation skills on a scale from 0 to 10. For the experienced group, each participant was asked to perform cannulation in all four different cannulation areas as we rotated the simulator for each trial. Each participant of the expert group was asked to perform cannulation in all four different cannulation areas twice. However, due to time constraints, not all participants were able to finish all four trials, resulting in 58 recorded trials for the experienced group and 29 trials for the expert group. It is worth noted that all the locations of fistulas to be cannulated are decided by a randomized program.

Results

We analyzed data towards answering four research questions: (1) can objective metrics differentiate skill between the experienced and expert groups? (2) do both groups employ modulation of force and movement (as an indicator of skill)? (3) is cannulation behavior adapted to curved (more difficult) versus straight fistulas?, and (4) are questionnaire measures (e.g., years of experience) correlated with quantified skill? We tested for normality of metrics by using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test on all metrics. Results indicated that these data sets did not follow normal distribution. Therefore, the nonparametric Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to determine if the medians of two sample groups were equal.

Objective Metrics

In the following section, we report the difference of medians for the four metrics between the two groups. The median time taken to complete cannulation for the experienced and the expert in Phase I are 1.95s and 1.35s (p<0.01), respectively, while those in Phase II are 2.41s and 1.48s (p<0.01), respectively. The force intensity metric also demonstrates significant differences. The median force intensity of the experienced and the expert in Phase I are 1.35 and 1.03 (p<0.01) respectively, while those in Phase II are 1.63 and 1.03 (p<0.01) respectively. The median path length of the experienced and the expert in Phase I are 69.75mm and 26.70mm (p<0.01) respectively, while those in Phase II are 88.26mm and 19.25mm (p<0.01) respectively. Lastly, needle angle in both Phases was also used to evaluate the skills of the participants. In Phase I and II, the results of the Wilcoxon rank sum test were not able to reject the null hypothesis. This means there is not enough evidence to prove that the experienced and the expert use different needle angles during the cannulation process. 93% of the angle data (in Figure 5 (g) and (h)) are between 20 and 35 degrees, which indicates consistency in this aspect of cannulation.

Figure 5:

The Experienced vs The Expert

(The green bars in subplots (g) and (h) indicate the range of cannulation angles prescribed per training guidelines4,36)

A principal component analysis (PCA) was performed on the metrics as an exploratory tool to assess the relationship between metrics. Figure 6 shows the factor loadings and PCA scores corresponding to the first two principal components (62.49% variance explained). The direction of the factor loading vectors indicates the degrees to which a variable contributes to each principal component. According to Figure 6, the loading vectors that correspond to PL and FI point in very similar directions for both phases, indicating a strong correlation among these variables in both phases (r=0.64 for Phase 1, r=0.82 for Phase 2). Further, the loadings corresponding to the PL and FI of Phase I point in nearly opposite directions from those of Phase II, in the direction of PC2. This indicates that the difference between these Phase I and Phase II behaviors account for a substantial portion of the variability in the dataset (25.75%). As such, this validates the utility of segmenting the cannulation process into the two phases (or subtasks) for a better understanding of cannulation skill.

Figure 6:

The PCA Biplot of Data Based on Objective Metrics. The PCA scores of trials performed by individuals in the expert group are shown in blue; those in the experienced group are shown in red. Only the first principal component (PC1) and second principal component (PC2) are used to represent the variance of this data set.

Logistic Regression Model

A logistic regression model was constructed to examine if membership in the expert group can be predicted using the following metrics: PL, NA, and FI for phase 1 and phase 2. The logistic regression model predicts membership in the “expert” group (1=expert; 0=experienced) using a set of predictor variables. Let Yi = 1 if trial i is performed by an expert and Yi = 0 if trial i is performed by an experienced, and use πi to denote the probability that Yi = 0. Then πi is modeled as:

| (4) |

where x1i, … , x6i are the six metrics observed for trial i. The coefficients β0, … , β6 are estimated using R via the glm function.

The estimated coefficients are listed in Table 1. The coefficients of the largest magnitude correspond to phase 1 and phase 2 force intensity (β=−2.18, p<0.01 and β=1.43, p<0.01), indicating a strong effect of force on discriminating between the expert and experienced cannulators. Further, an analysis of deviance reveals that these two variables significantly improve the fit over a logistic regression model with only path length and angle from phase 1 and phase 2 (X2=15.41, p<0.01).

Table 1.

Logistic Regression Model Coefficients

| Estimate | Std. Error | z Value | Pr (>∣z∣) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PhaseI. PL | −0.012 | 0.010 | −1.135 | 0.256 |

| PhaseII.PL | −0.046 | 0.014 | −3.414 | 0.001 |

| PhaseI. NA | −0.025 | 0.051 | −0.501 | 0.616 |

| PhaseII.NA | 0.131 | 0.061 | 2.141 | 0.032 |

| PhaseI.FI | −2.180 | 0.806 | −2.704 | 0.007 |

| PhaseII.FI | 1.434 | 0.478 | 2.998 | 0.003 |

The in-sample accuracy in classifying trials into the expert and experienced groups was 81.6%. Because the data contain multiple observations from each subject, creating a risk of overfitting the model to the specific individuals in the study, a "leave-one-subject-out" cross validation scheme was used to evaluate out-of-sample performance of the logistic regression model. In this strategy, the following procedure is repeated for each subject: all trials performed by the subject are omitted, and the logistic regression model is fit using data from the remaining subjects. The estimated model is then used to predict expert membership on the held-out observations. The average cross-validated out-of-sample classification accuracy for the model was 79.3%; the in-sample accuracy was 81.6%, indicating strong prediction accuracy.

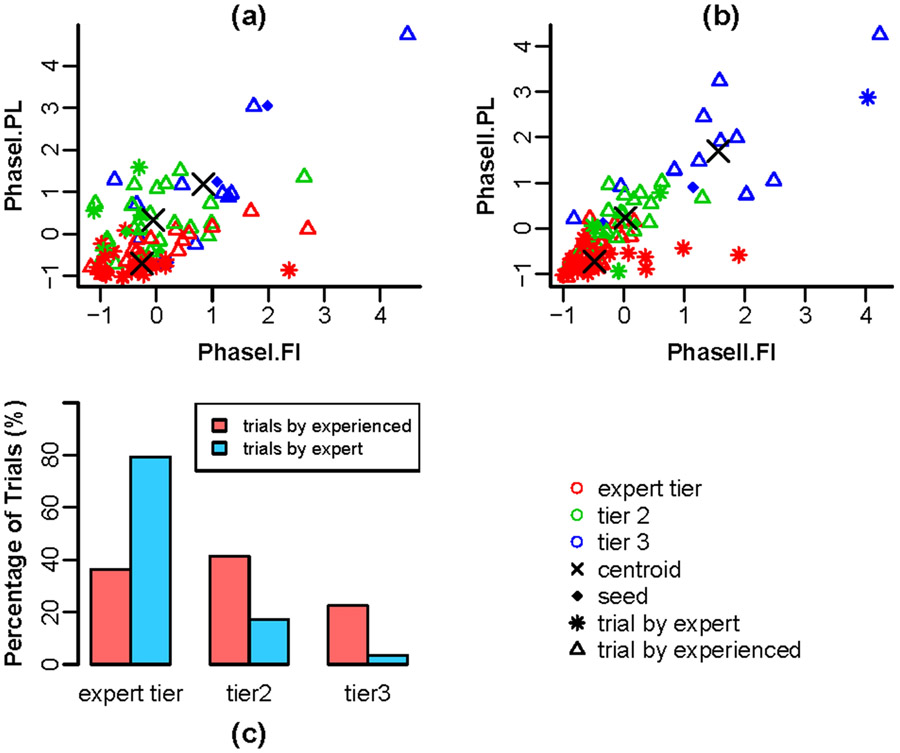

Force-Movement Modulation

Based on previous studies17, we examined whether the modulation of force and movement during cannulation was indicative of skill. That is, we hypothesized that experts carefully negotiate forces and motion applied during cannulation by making one or the other “mode” prominent in context. To this end, clustered subgroups of trials share similar features using a semi-supervised analysis. A small number of trials were first selected using peer-reputation and video evidence to be representatives of three performance tiers: the expert tier represents strong performance, tier 3 represents poor performance, and tier 2 is a group that describes intermediate performance between the two groups. We labeled the representative trials according to their corresponding performance tiers and then analyzed all trials in semi-supervised linear discriminant analysis (LDA) with self-training, as shown in Figure 7. Self-training32 is a method to classify samples containing both labeled and unlabeled observations. The classifier was trained first on the labeled trials and then used to estimate classification probabilities for the unlabeled trials. Those trials with the highest classification probabilities were then added to the labeled set, and the process iterates to convergence. The advantage of the semi-supervised approach is that the labeled observations preserve the groups' interpretability as representative of the aforementioned performance tiers, but the features of the groups are determined in a primarily data-dependent manner.

Figure 7:

Semi-supervised LDA Data Clustering on Assessing Performance

Adaptability to Fistula Parameters

We also hypothesized that fistula-specific behavior adaptation (e.g., fistula curvature and diameter) would reveal the cannulation skills of participants. To test this, we organized data according to the curvature and diameter of the fistula models and conducted metrics-based analysis. Results revealed that time to complete cannulation and force intensity metrics in Phase II demonstrated statistical significance. That is, when encountering curved fistula models, participants used 1.11s less time in Phase II (p=0.02) and used 1.06 less force intensity in Phase II (p=0.01) as demonstrated in Figure 8. Considering that curved fistulas have a higher chance of needle infiltration, it is expected that experts would advance the needle more gently and for a shorter time span once they see blood flashback.

Figure 8:

The Adaptability Comparison between the Expert and the Experienced

Are Years of Experience a Reliable Factor to Find the Experts?

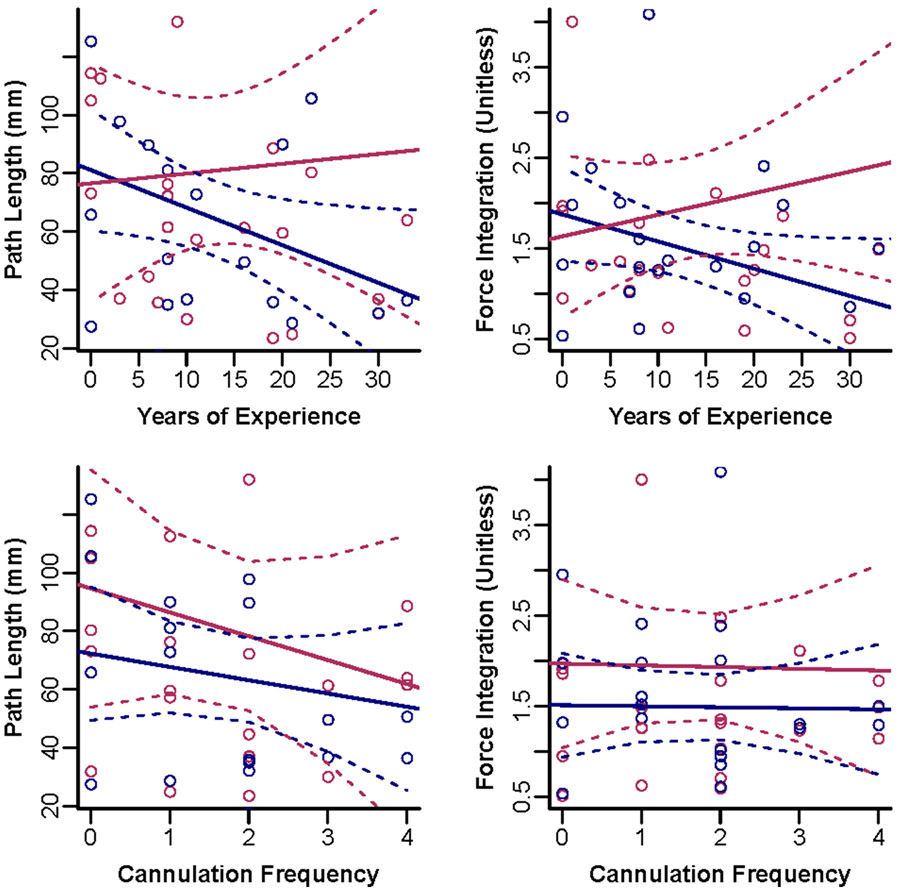

Our final question examined a common assumption in skill development—that years of experience is equivalent to expertise in a clinical task. We gathered two measures from experiment questionnaires: years of experience and frequency of cannulation. As depicted in Figure 9, there is no apparent trend from that data that suggests cannulation skills correlate with years of experience or cannulation frequency. It is worth noting, however, that PL in phase I has a correlation of 0.37 with years of experience (p=0.049) and FI in Phase I has a correlation of 0.34 with years of experience (p=0.06). As for cannulation frequency, data did not hint at a relationship between skill and the number of times a participant performs dialysis cannulation per month.

Figure 9:

Relationship of cannulation performance as a function of years of experience and cannulation frequency. (The navy colored dots are medians of Phase I while the maroon colored dots are medians of Phase II. The solid lines stand for the linear regression estimates and the dotted lines secure the region for 95% confidence intervals.)

Discussion

As previously mentioned, the prevailing paradigm in medical education is to assume that experience performing certain clinical procedures (like cannulation) is correlated with expertise. As such, little attention has focused on defining skill expertise using objective metrics outside of this paradigm. In this study, we explored several methods to quantify and differentiate cannulation skill between expert cannulators and those with experience using sensor-based metrics. Based on the results presented, experienced and expert subjects performed differently in terms of the metrics TS, PL, and FI in Phase I and II of the cannulation task. Specifically, the median of time spent (TS) in Phase I among the experts was 0.6s less than that of the experienced group (1.35s vs 1.95s). This suggests that experts were more time efficient in guiding the needle into the fistula, thereby shortening the time of pain and potential tissue damage in a clinical setting. Similar results appear in the TS of Phase II, where the median time spent among experts was nearly 1.0s less than the experienced group (1.48s vs 2.41s). In Phase II, the cannulator aims to secure the needle in a proper position for taping. Experts spending less time in Phase II is likely to indicate their confidence and effectiveness in adjusting the needle position after flashback.

In addition to time, we also computed metrics based on needle movement. Ideally, needle movement should be smooth, controlled, and steady. Path length (PL) of needle movement was calculated for all trials of both groups. In a previous study, excessive needle movement during cannulation was related to unnecessary tissue damage33. Other past studies also proved that shorter path length related to higher levels of skill among clinicians5,7,25. The median PL among experts was approximately 43mm and 69mm less than that of the experienced groups in Phase I and II respectively. As results indicate, there was a discernible difference between the two groups with respect to needle movement during insertion.

In addition to the previously used metrics of time and path length, we formulated a new metric based on pinch forces during needle insertion. Force Intensity (FI) was introduced to quantify, for the first time, an important aspect of hemodialysis cannulation skill. We postulated that experts had distinctive patterns of touch during cannulation that enabled their effectiveness. Several educators in the hemodialysis healthcare community describe the critical role forces plan in safe and effective cannulation. Force “style” can be categorized as “heavy handed” versus “light handed”. Patients often prefer to receive care from “light handed” clinicians since they are gentler and, consequently, induce less pain. In this vein, Villanueva and colleagues demonstrate that force used to hold a clinical tool with the fingers is positively correlated with the force exerted on the tissue at the distal end of the tool29. Results from the FI metric indicate that, in both Phase I and II, experts tended to use less force intensity than the experienced group. Specifically, in Phase II the median of force intensity of the experienced group was 60% higher than that of experts. This implies that experts were more likely to use controlled forces in short bursts of time, representing “light handed” behavior. Similarly, a previous study reported that during various complex catheterization tasks, experts applied significantly less distal forces compared to novices29. As for the needle angle (NA) metric, results indicated that the two groups did not use significantly different needle angles during cannulation. Prescribed guidelines for cannulating AVFs instruct clinicians to keep needle angle between 20 and 35 degrees4,36, which is consistent with the angles observed in this study. From another perspective, this result seems to indicate that simply recording needle angles does not distinguish experts from the experienced.

The advantage of having these objective metrics from various sensing mechanisms is that it allows the combination of metrics, depicting a more vivid picture of the two groups. With PCA analysis, the original 6-dimensional dataset, including path length, force integration and needle angle from both Phase I and Phase II, was reduced to 2 dimensions. This not only helps visualize the differences between the two skill levels, but also confirms that Phase I and Phase II have distinct characteristics. We also combined these metrics to construct models to predict expertise based on sensor-based objective metrics. Using PL, NA, and FI for Phase I and II, a logistic regression model was built, and both in-sample and out-of-sample accuracy were around 80%. In addition, results from the semi-supervised self-learning classifier for expertise yielded that 79.3% of expert trials fell into the "expert tier" while 63.8% of the trials of experienced participants fell outside of the "expert tier". From this model it can be noted that experts consistently perform at par whereas the experienced perform “expertly” only some of the time. Both the logistic regression and clustering models show promise for expertise-based skill assessment. As an aside, the logistic regression model with FI yielded a significantly better fit than one without FI for predicting experts. Therefore, we infer that force sensing in this simulator provides valuable insight towards skill assessment.

Although the previous analyses revealed skill differences between the two groups, we also investigated how fistula parameters (i.e. diameter and curvature) affected the performance of the experienced and expert groups. Analysis reveals that with curved fistulas, all subjects tended to use less time span and less force intensity in Phase II compared to straight fistulas. Because curved fistulas constrain the needle to less room for attaining blood flashback without infiltration, experts were able to adapt their behavior to this challenging situation (see Figure 8).

Finally, we examined if the amount of experience is related to expertise as quantified by our metrics. As presented in Figure 9, no strong correlation was evidenced between cannulation performance (quantified by metrics) and years of experience or cannulation frequency. Although years of experience (or the number of cases, in surgery) is often used to informally gauge expertise among clinicians, many remain “perpetual novices” despite having clinical experience for lack of meaningful training30. As such, there is a need for expertise to be defined as a function of true clinical skill with objective metrics being an excellent candidate for this purpose.

Limitations

We wish to point out several limitations of our study. First, the sample size of experts is relatively small and, as such, is limited in variability seen in metrics. In addition, we didn’t account for correlations within subjects, maybe hindering the replicability of the exact analytical results to another study population. Second, not all the test subjects were primarily dialysis cannulation technicians or nurses; these individuals regularly performed other types of vascular access interventions. Third, the thickness of the artificial skin layer—an important parameter during cannulation—remained unchanged in this study. In the future, we aim to improve the test design and simulator structure to make it adjustable. Fourth, the metric needle angle (NA) was calculated based on the average angle in each phase. Consequently, detailed needle angle movement cannot be reflected through this metric. Finally, we did not examine if some learning occurred in subjects as trials progressed. Though the results presented here is hemodialysis cannulation specific, in the future, we aim to examine simulator-based cannulation for other procedures with pertinent design customizations.

In summary, we presented preliminary findings towards employing a multimodal hemodialysis cannulation training simulator for skill assessment and training. Twenty-two hemodialysis technicians and nurses performed cannulation on the simulator, with results indicating that experts performed significantly differently than those in the experienced group. The simulator-based objective metrics used in this study demonstrate that expertise in cannulation is not necessarily synonymous with clinical experience. Furthermore, even finer-grained differences in skill level can be discerned by the suite of metrics employed in this study. In the future, we plan to acquire a larger dataset of cannulation performances from clinicians and dialysis technician students towards establishing benchmarks for skill assessment and training.

Figure 4:

Demographic Information of the Participants

(For cannulation frequency: 1: less than 5 cases per month; 2: between 5 and 20 cases per month; 3: between 20 and 50 cases per month; 4: between 50 and 100 cases per month)

Acknowledgements

Research reported in this publication was supported by a NIH/NIDDK K01 award (K01DK111767).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

Results presented in this paper have not been published previously in whole or part, except in abstract format. Mr. Liu has nothing to disclose. Ms. Zhang has nothing to disclose. Dr. Kunkel has nothing to disclose. Dr. Roy-Chaudhury reports other from WL Gore, other from Becton Dickinson, other from Medtronic, other from Cormedix, other from Humacyte, other from Bayer, other from Akebia, other from Reata, other from Vifor-Relypsa, other from Inovasc, outside the submitted work; Dr. Singapogu reports grants from NIH/NIDDK, during the conduct of the study; other from Radiant Ventures, outside the submitted work.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

References:

- 1.Aggarwal R, Ward J, Balasundaram I, Sains P, Athanasiou T, and Darzi A. Proving the effectiveness of virtual reality simulation for training in laparoscopic surgery. Ann. Surg 246:771–779, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersen P, and Cox K. SimMan 3G™: Manikin-Led Simulation Orientation. Clinical Simulation In Nursing 40:1–6, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anh NX, Nataraja RM, and Chauhan S. Towards near real-time assessment of surgical skills: A comparison of feature extraction techniques. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine 187:105234, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brouwer DJ Cannulation Camp: Basic needle cannulation training for dialysis staff. Dialysis & Transplantation 40:434–439, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen H-E, Yovanoff MA, Pepley DF, Prabhu RS, Sonntag CC, Han DC, Moore JZ, and Miller SR. Evaluating Surgical Resident Needle Insertion Skill Gains in Central Venous Catheterization Training. Journal of Surgical Research 233:351–359, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clinkard D, Moult E, Holden M, Davison C, Ungi T, Fichtinger G, and McGraw R. Assessment of Lumbar Puncture Skill in Experts and Nonexperts Using Checklists and Quantitative Tracking of Needle Trajectories: Implications for Competency-Based Medical Education. Teaching and Learning in Medicine 27:51–56, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Datta V, Mackay S, Mandalia M, and Darzi A. The use of electromagnetic motion tracking analysis to objectively measure open surgical skill in the laboratory-based model1 1No competing interests declared. Journal of the American College of Surgeons 193:479–485, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fahy AS, Jamal L, Carrillo B, Gerstle JT, Nasr A, and Azzie G. Refining How We Define Laparoscopic Expertise. Journal of Laparoendoscopic & Advanced Surgical Techniques 29:396–401, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frey AM Success Rates for Peripheral IV Insertion in a Children’s Hospital. Journal of Infusion Nursing 21:160–165, 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fried GM FLS Assessment of Competency Using Simulated Laparoscopic Tasks. J Gastrointest Surg 12:210–212, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang FC, Mohamadipanah H, Mussa-lvaldi F, and Pugh C. Combining metrics from clinical simulators and sensorimotor tasks can reveal the training background of surgeons. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 1–1, 2019.doi: 10.1109/TBME.2019.2892342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hung AJ, Oh PJ, Chen J, Ghodoussipour S, Lane C, Jarc A, and Gill IS. Experts vs super-experts: differences in automated performance metrics and clinical outcomes for robot-assisted radical prostatectomy. BJU International 123:861–868, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jacobson AF, and Winslow EH. Variables influencing intravenous catheter insertion difficulty and failure: An analysis of 339 intravenous catheter insertions. Heart & Lung 34:345–359, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones RS, Simmons A, Boykin GL, Stamper D, and Thompson JC. Measuring Intravenous Cannulation Skills of Practical Nursing Students Using Rubber Mannequin Intravenous Training Arms. Mil Med 179:1361–1367, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keleekai NL, Schuster CA, Murray CL, King MA, Stahl BR, Labrozzi LJ, Gallucci S, LeClair MW, and Glover KR. Improving Nurses’ Peripheral Intravenous Catheter Insertion Knowledge, Confidence, and Skills Using a Simulation-Based Blended Learning Program: A Randomized Trial. Simulation in Healthcare: The Journal of the Society for Simulation in Healthcare 11:376–384, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.KM I, Groff RE, and Singapogu RB. Surgical Suturing with Depth Constraints: Image-based Metrics to Assess Skill. , 2018.doi: 10.1109/EMBC.2018.8513266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Konstantinova J, Li M, Mehra G, Dasgupta P, Althoefer K, and Nanayakkara T. Behavioral Characteristics of Manual Palpation to Localize Hard Nodules in Soft Tissues. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 61:1651–1659, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee T, Barker J, and Allon M. Needle Infiltration of Arteriovenous Fistulae in Hemodialysis: Risk Factors and Consequences. American Journal of Kidney Diseases 47:1020–1026, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin Y, Wang X, Wu F, Chen X, Wang C, and Shen G. Development and validation of a surgical training simulator with haptic feedback for learning bonesawing skill. Journal of Biomedical Informatics 48:122–129, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu Z, Bible J, Wells J, Vadivalagan D, and Singapogu R. Examining the Effect of Haptic Factors for Vascular Palpation Skill Assessment Using an Affordable Simulator. IEEE Open Journal of Engineering in Medicine and Biology 1:228–234, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu Z, Petersen L, Zhang Z, and Singapogu R. A Method for Segmenting the Process of Needle Insertion during Simulated Cannulation using Sensor Data. , 2020.doi: 10.1109/EMBC44109.2020.9176158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lok CE, Huber TS, Lee T, Shenoy S, Yevzlin AS, Abreo K, Allon M, Asif A, Astor BC, Glickman MH, Graham J, Moist LM, Rajan DK, Roberts C, Vachharajani TJ, and Valentini RP. KDOQI Clinical Practice Guideline for Vascular Access: 2019 Update. American Journal of Kidney Diseases 75:S1–S164, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Loukas C, Nikiteas N, Kanakis M, Moutsatsos A, Leandros E, and Georgiou E. A Virtual Reality Simulation Curriculum for Intravenous Cannulation Training. Academic Emergency Medicine 17:1142–1145, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCluney AL, Vassiliou MC, Kaneva PA, Cao J, Stanbridge DD, Feldman LS, and Fried GM. FLS simulator performance predicts intraoperative laparoscopic skill. Surgical Endoscopy 21:1991–1995, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moorthy K, Munz Y, Sarker SK, and Darzi A. Objective assessment of technical skills in surgery. BMJ 327:1032–1037, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Polanczyk A, Klinger M, Nanobachvili J, Huk I, and Neumayer C. Artificial Circulatory Model for Analysis of Human and Artificial Vessels. Applied Sciences 8:1017, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reznick RK, and MacRae H. Teaching surgical skills—changes in the wind. New England Journal of Medicine 355:2664–2669, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Uemura M, Tomikawa M, Kumashiro R, Miao T, Souzaki R, leiri S, Ohuchida K, Lefor AT, and Hashizume M. Analysis of hand motion differentiates expert and novice surgeons. Journal of Surgical Research 188:8–13, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Villanueva A, Dong H, and Rempel D. A biomechanical analysis of applied pinch force during periodontal scaling. Journal of Biomechanics 40:1910–1915, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilson B, Harwood L, and Oudshoorn A. Moving beyond the “perpetual novice”: Understanding the experiences of novice hemodialysis nurses and cannulation of the arteriovenous fistula. CANNT Journal 23:11–18, 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilson M, McGrath J, Vine S, Brewer J, Defriend D, and Masters R. Psychomotor control in a virtual laparoscopic surgery training environment: gaze control parameters differentiate novices from experts. Surg Endosc 24:2458–2464, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yarowsky D Unsupervised Word Sense Disambiguation Rivaling Supervised Methods. , 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yeo CT, Ungi T, U-Thainual P, Lasso A, McGraw RC, and Fichtinger G. The Effect of Augmented Reality Training on Percutaneous Needle Placement in Spinal Facet Joint Injections. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 58:2031–2037, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yovanoff M, Pepley D, Mirkin K, Moore J, Han D, and Miller S. Improving Medical Education: Simulating Changes in Patient Anatomy Using Dynamic Haptic Feedback. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting 60:603–607, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang Z, Liu Z, and Singapogu R. Extracting Subtask-specific Metrics towards Objective Assessment of Needle Insertion Skill for Hemodialysis Cannulation. J. Med. Robot. Res , 2020.doi: 10.1142/S2424905X19420066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Clinical Practice Guidelines for Vascular Access. American Journal of Kidney Diseases 48:S248–S273, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]