To the Editor:

We read with interest the letters “Autoimmune hepatitis developing after coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Vaccine: Causality or casualty?” by Bril et al. 1 and “Autoimmune hepatitis following SARS-CoV-2 vaccine: May not be a casuality” by Rocco et al. 2 which highlight the hypothesis that COVID-19 mRNA-based vaccines might increase the risk of developing autoimmune diseases. There are growing reports of autoimmune diseases developing after SARS-CoV-2 infection, including Guillain-Barré syndrome and primary biliary cholangitis.3 It is speculated that SARS-CoV-2 can disturb self-tolerance and trigger autoimmune responses through cross-reactivity with host cells and that the COVID-19 mRNA vaccines may trigger the same response.4 , 5

We report a further case of autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) following COVID-19 mRNA vaccination. Our patient is a 71-year-old Caucasian female. Background history was significant for cholecystectomy 20 years previously, left total hip replacement and osteoarthritis of the knees. There were no risk factors for autoimmune disease. She was on no regular medications or supplements.

She received the Moderna mRNA vaccine on the 16th of April 2021. During the 24-hour period around vaccination she took 2 g of paracetamol. Four days post vaccination she noticed jaundice. She attended her primary carer on the 26th of April (+10 days post vaccination). Laboratory results were markedly abnormal (bilirubin 270 μmol/L, alkaline phosphatase 217 U/L, alanine aminotransferase 1,067 U/L). She was promptly referred to our hepatology services.

On physical examination she was jaundiced. Laboratory results were negative for hepatitis B, C, and E, Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus and HIV. Hepatitis A IgG was positive with a negative IgM. Smooth muscle antibody was strongly positive with a titre of 2,560 and an anti-actin pattern. Total IgG was markedly raised at 21.77 g/L. Liver ultrasound, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography and computer tomography pancreas protocol showed distal common bile duct dilation of 1.4 cm consistent with prior cholecystectomy.

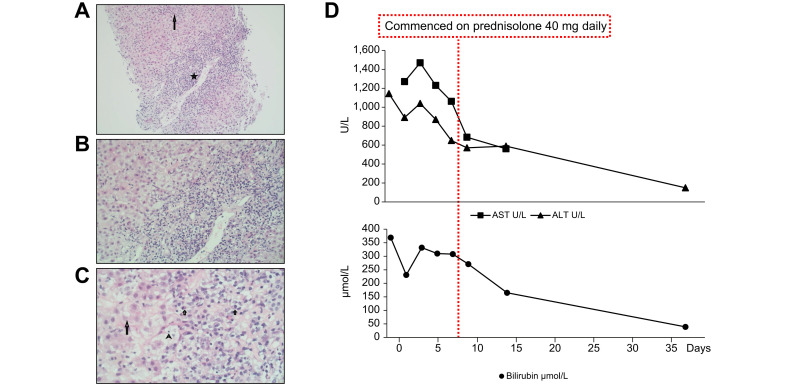

On receipt of positive autoantibodies and a rising liver profile (bilirubin 332 μmol/L, alanine aminotransferase 1,143 U/L, aspartate aminotransferase 1,469 U/L, alkaline phosphatase 237 U/L and international normalized ratio 1.4), steroids were commenced on the 4th of May and liver biopsy was performed the following day. Up to 20 portal tracts were present, each expanded with a marked polymorphous inflammatory cell infiltrate of plasma cells, lymphocytes, eosinophils, neutrophils and PASD-positive ceroid laden macrophages; interface hepatitis was present and continuous in most tracts, with portal-portal and portal-central bridging necrosis (Fig. 1 A–C). The findings were compatible with AIH, however drugs, toxins or infections could not be ruled out as aetiological agents.

Fig. 1.

Histological (H&E stain) and biochemical findings.

(A) Marked portal tract (star) inflammation with enlargement and an irregular disrupted interface and a lobular hepatitis (long arrow)(100x). (B) At higher magnification the portal tract inflammation is mononuclear with spill over and damage to the periportal hepatocytes (200x). (C) At high magnification many of the mononuclear inflammatory cells are plasma cells (short arrows). This lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate damages periportal hepatocytes with some forming rosettes (long arrow) and with occasional emperipolesis of lymphocytes (arrowhead)(400x). (D) Trend of ALT, AST and bilirubin following introduction of steroids. ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase. (This figure appears in color on the web.)

Since discharge from hospital our patient remains well and liver biochemistry has continued to improve on a tapering course of prednisolone (Fig. 1D).

There are a number of similarities between the previously described cases and our own. Firstly, there was a short interval between vaccination and symptom onset in all cases. In response to the first case, Capecchi et al. 6 questioned whether this was too short an interval to develop the necessary immune activation. It is indeed short when compared to established causatives agents of drug-induced autoimmune liver disease such as immune checkpoint inhibitors where a latency period of 2 to 24 weeks has been described.7 However, a much shorter latency period is described for other vaccine-induced autoimmune conditions such as Guillain-Barré syndrome (median onset 13 days).8

Secondly, histological appearances are similar between our case and that described by Bril et al. Both cases had an eosinophil infiltration which is more typical of a drug-induced liver injury. This raises the possibility that this is a vaccine-related drug-induced liver injury with features of AIH rather than the vaccine causing immune dysregulation.

Unlike the other cases, our patient had no confounding risk factors for developing autoimmune liver disease such as other autoimmune conditions or recent pregnancy and she received a different mRNA vaccine, Moderna rather than Pfizer-BioNTech.

These findings raise the question as to whether COVID-19 mRNA vaccination can, through activation of the innate immune system and subsequent non-specific activation of autoreactive lymphocytes, lead to the development of autoimmune diseases including AIH or trigger a drug-induced liver injury with features of AIH. The trigger, if any, may become more apparent over time, especially following withdrawal of immunosuppression. As with other autoimmune diseases associated with vaccines the causality or casualty factor will prove difficult to tease apart and should not distract from the overwhelming benefits of mass COVID-19 vaccination. But it does beg the question of whether or not these individuals should receive the second dose of an mRNA COVID-19 vaccine.

Financial support

The authors received no financial support to produce this manuscript.

Authors’ contributions

Dr Cathy McShane, Dr Clifford Kiat & Dr Órla Crosbie - involved in clinical care of patient and writing of manuscript. Dr Jonathan Rigby – interpreted histology and involved with writing of manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest that pertain to this work.

Please refer to the accompanying ICMJE disclosure forms for further details.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2021.06.044.

Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Bril F., Al Diffalha S., Dean M., Fettig D.M. Autoimmune hepatitis developing after coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccine: causality or casualty? J Hepatol. 2021;75:222–224. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2021.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rocco A., Sgamato C., Compare D., Nardone G. Autoimmune hepatitis following SARS-CoV-2 vaccine: may not be a casuality. J Hepatol. 2021;75:728–729. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2021.05.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartoli A., Gitto S., Sighinolfi P., Cursaro C., Andreone P. Primary biliary cholangitis associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection. J Hepatol. 2021;74:1245–1246. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2021.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lui Y., Sawalha A.H., Lu Q. COVID-19 and autoimmune diseases. Curr Opin Rheumatol. March 1 2021 doi: 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Velikova T., Georgiev T. SARS-CoV-2 vaccines and autoimmune diseases amidst the COVID-19 crisis. Rheumatol Int. January 30 2021 doi: 10.1007/s00296-021-04792-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Capecchi P.L., Lazzerini P.E., Brillanti S. Comment on “Autoimmune hepatitis developing after coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Vaccine: causality or casualty?”. J Hepatol. May 2021;75:994–995. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2021.04.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Regev A., Avigan M., Kiazand A., Vierling J., Lewis J., Omokaro S., et al. Best practices for detection, assessment and management of suspected immune-mediated liver injury caused by immune checkpoint inhibitors during drug development. J Autoimmun. 2020;114 doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2020.102514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haber P., DeStefano F., Angulo F.J., Iskander J., Shadomy S.V., Weintraub E., et al. Guillain-barré syndrome following influenza vaccination. JAMA. 2004;292(20):2478–2481. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.20.2478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.