Abstract

Difficulties associated with Autism Spectrum Disorders can cause considerable impact on personal, familial, social, educational and occupational functioning. Living with a child who has an Autism Spectrum Disorder can therefore pose a challenge to family members, including typically developing siblings. However, it is only in recent years that the experience of typically developing siblings has become a focal point. A systematic review using keywords across six databases was undertaken to summarise qualitative studies that focused on the experience of being a sibling of a child with an Autism Spectrum Disorder. Fifteen studies met inclusion criteria and a thematic synthesis was completed. The synthesis found that having a sibling who has an Autism Spectrum Disorder can impact typically developing sibling’s self-identity and personal development in a number of ways. Similarly, interactions with the sibling who has Autism Spectrum Disorders and with other individuals can evoke a myriad of experiences that can both benefit and challenge typically developing siblings. The ability of typically developing siblings to cope with adverse experiences needs to remain a focus. This synthesis concludes that further research is needed to identify which methods are the most effective in supporting typically developing siblings of children with Autism Spectrum Disorders.

Keywords: School-age children, siblings, autism spectrum disorder, experience, systematic review

Introduction

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by deficits in social communication and interaction across a variety of contexts, in addition to restricted, repetitive behaviours and/or interests that are present from early childhood (World Health Organisation [WHO], 2018). Accurately measuring the international prevalence of ASDs remains a considerable challenge (Elsabbagh et al., 2012), with figures generally rising over the past few decades (Onaolapo & Onaolapo, 2017). For example, in England, McConkey (2020) found that for every 100 school pupils, 0.97 were reported to have ASD in 2010/11, rising to 2.25 in 2018/19.

The difficulties associated with an ASD can cause considerable impact on personal, familial, social, educational and occupational areas of functioning (WHO, 2018). As such, it is no wonder that living with a child who has ASD can present both benefits and challenges to family members (Cridland et al., 2014; Macks & Reeve, 2007; Woodgate et al., 2008). While the impact on parents caring for a child with ASD is well documented (Hayes & Watson, 2013; Meadan, Halle, et al., 2010), it is only in recent years that attention has turned to the typically developing (TD) siblings of children with ASD (Green, 2013; Meadan, Stoner, et al., 2010; Thomas et al., 2015).

The sibling relationship is commonly the longest many have in their lives (Green, 2013). Siblings are often the first playmates, the first role models and the first teachers children will have (Banda, 2015; McHale et al., 2016). As such this unique relationship provides the opportunity for social, emotional, behavioural and psychological development (McHale et al., 2012), all of which are particularly important for children with ASD who can face many challenges across these areas (WHO, 2018). While the sibling relationship may provide many positives for the child with ASD, detrimental impacts are noted in TD siblings (Banda, 2015; Ferraioli & Harris, 2010; Kaminsky & Dewey, 2001; Orsmond & Seltzer, 2007; Saxena & Adamsons, 2013). For example, Giallo et al. (2012) found that 15% of siblings (aged 10–18 years) of children with varying disabilities were at risk or in the clinically significant range for emotional symptoms and prosocial behaviour on a self-report questionnaire; 20% to 30% also met at-risk or clinical threshold on overall difficulties and hyperactivity, conduct and peer problems subscales. Similarly, when compared to siblings in general, a number of studies have found that TD siblings of a brother or sister with ASD are at an increased risk of mental health difficulties such as symptoms of depression or anxiety (e.g. Lovell & Wetherell, 2016; Macks & Reeve, 2007).

However, the majority of previous literature on TD siblings of children with ASD has focused on their functioning or adjustment compared to siblings of children who do not have ASD (McHale et al., 2016; Meadan, Stoner, et al., 2010; O’Brien et al., 2009; Shivers et al., 2019; Smith & Elder, 2010; Tsao et al., 2012). For example, a recent meta-analysis of 69 articles found that TD siblings of individuals with ASD have significantly worse outcomes across all areas of social, emotional, behavourial and psychological functioning, than comparison groups (Shivers et al., 2019).

Through the nature of looking at sibling functioning or adjustment, many, if not all, studies have used questionnaire data, mainly gathered from the perspective of parents and/or teachers (Shivers et al., 2019), rather than from the TD siblings themselves. To address this gap, Mandleco and Webb (2015) reviewed research where TD siblings, living with a young person who had Down Syndrome (DS) or ASD, were participants themselves. The authors found that TD siblings living with young people who had ASD seemed to know more about their sibling’s disability than siblings living with young people with DS. However, they reported more negative perceptions and less prosocial behaviours towards their sibling, than siblings of young people with DS. Similarly, they were more likely to report ASD as stressful and negatively impacting their interactions with friends. Following this, Leedham et al. (2020) thematically synthesized qualitative research that investigated the lived experience of TD siblings of people who have an ASD, across the lifespan. They found that TD siblings experienced different roles and responsibilities than may be typically expected, and that these had a significant impact on some siblings’ mental health in adulthood. Similarly, TD siblings were particularly affected by aggressive behaviours displayed by their sibling who has an ASD. However, Leedham et al. (2020) also described a ‘narrative of love, affection and empathy’, across included studies, with TD siblings having developed increased understanding, empathy and compassion towards others, due to their experience of having a sibling who has an ASD.

While the above reviews shed some light on the current literature regarding TD siblings of children with ASD they either compare TD sibling experiences to another population (e.g. DS, Mandleco & Webb, 2015) or merge experiences of younger and much older TD siblings together (e.g. age range: 4 to 67 years old, Leedham et al., 2020). The latter presents a particular challenge to the interpretation of findings as TD siblings born in the 1960s, for example, are likely to have vastly different experiences than those born much later, due to the demonstrable changes in the way society views ASD and the ways in which healthcare professionals work with people who have an ASD. Furthermore, by including such a large age range of siblings, some of the data synthesized is reliant upon sibling reflections of situations they encountered several decades earlier.

Therefore, this systematic review aims to summarise studies that explored the experience of being a TD sibling of a child with an ASD, from their own perspective, without comparison to another clinical population or to TD siblings above the age of 18. It is hoped that this would provide deeper insight into the lived experience of being a younger TD sibling and what support, if any, they may benefit from. This mirrors the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE, 2013) guidelines that state families of children with ASD, including siblings, should have an assessment of their own needs.

Method

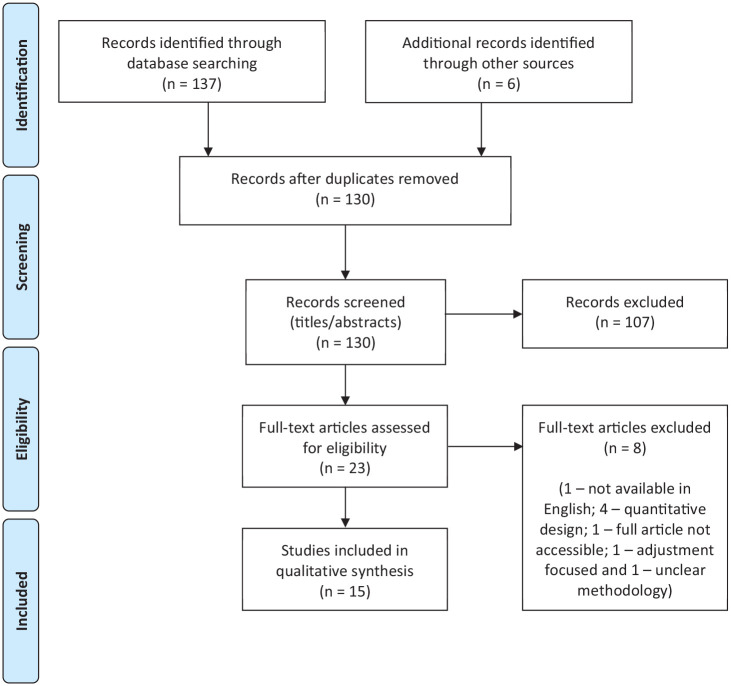

Our review adhered to the steps described in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (Liberati et al., 2009). The protocol for this systematic review was prospectively registered on PROSPERO (Watson, et al., 2019, CRD42019143164).

Search strategy

A systematic search of keywords (Appendix 1) of published studies was undertaken within the following six databases: PsycINFO, PubMed, British Nursing Index, SCOPUS, Web of Science and CINAHL, from inception until 26th October 2020. Database searches were supplemented by additional searches through reference sections of all identified articles, to locate any that may have been overlooked in the initial database searches. Six additional articles were uncovered during this process.

Study inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were eligible for inclusion if the primary aim of the study was to explore the experience of child TD siblings, who have a sibling diagnosed with an Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). As such, qualitative studies that investigated any aspects of sibling experiences (e.g. directly with their sibling and/or indirect experiences such as interaction with their parents/peers/others, schooling, leisure activities etc.) were included. While ‘experience’ is a broad construct, the scope for this review was deliberately kept wide as the authors did not wish to preempt the types of experiences of TD siblings of children who have an ASD.

In addition to the above, articles were included if they were (a) available in English, (b) empirical studies and (c) published in peer-reviewed journals. Review articles, books, book chapters, unpublished dissertations, theses and standalone abstracts without a full-article were excluded.

To meet eligibility criteria, empirical studies needed to incorporate a qualitative design and include (i) direct involvement of TD siblings, (ii) who were aged between 0 to 18 years, (iii) who had at least one sibling who had a diagnosis of an Autism Spectrum Disorder (including Autism, Asperger’s Syndrome or Pervasive Developmental Disorder Not Otherwise Specified (PDD-NOS), with or without an intellectual disability. Studies that reported on other populations (e.g. intellectual disability) in addition to individuals with ASD were also retained. In two studies that included siblings who were both younger and older than 18 years old, data for participants younger than 18 years was extrapolated where possible. However, studies were excluded if they only used TD siblings of children with ASD as (i) comparison groups to their sibling with ASD, (ii) control groups or (iii) as part of an intervention focused on the sibling with ASD. Similarly, studies were excluded if results were reported for the family as a whole, rather than including separate sibling analysis. There were no restrictions on sample size or date published.

Study selection, quality assessment and data extraction procedures

Following the initial database search, duplicates were removed and study titles were reviewed in order to remove any irrelevant articles. Abstracts of articles were then reviewed for potential inclusion following examination of the full article. Identified articles were then reviewed in full and those that did not meet inclusion criteria were removed. In addition, reference sections were scanned in order to identify any additional articles that may have been missed.

The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP, 2019) qualitative studies checklist was used to assess study quality. Based on the criteria used in previous systematic reviews (e.g. Carolan et al., 2018), studies were deemed low, medium or high in quality if 0 to 4, 5 to 7 or 8 to 10 of the ten CASP questions were answered ‘yes’ respectively.

A data extraction framework was developed to summarise information about the studies: (a) publication source, (b) geographical origin, (c) aim, (d) sample, (e) design (e.g. qualitative, quantitative, mixed method, review, longitudinal, case study) (f) procedure (including measures used), (g) analysis and (h) results. The first author completed all of the above steps and a decision to remove or include studies was based on consensus following discussions with the second and third authors (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Search results presented using the PRISMA flow diagram (Moher et al., 2009).

Data synthesis

Thematic synthesis (Thomas & Harden, 2008) was used to combine and analyse all text labelled as ‘results’ or ‘findings’ in each article. The raw data collected was read line-by-line several times to identify emerging themes and concepts. As each study was read through, the list of themes and concepts was added to and new ones were developed where required. Once collected, similarities and differences between the themes and concepts were reviewed and organized into groups so that descriptive themes could be generated. At this stage, a draft summary of findings across the studies was written by the first author and reviewed by the other two authors. In order to answer our research question and surpass the content of included articles, each author independently inferred what the TD siblings’ experiences were of having a sibling with ASD from the collated descriptive themes. After further discussion as a group, analytical themes emerged and the process was repeated until these new themes adequately described the initial descriptive themes and concepts, while also offering a new interpretation and implications for future research and clinical directions.

Results

Study characteristics

From the initial 143 articles identified, 15 met eligibility and were included in the review. A detailed summary of all aspects of the 15 included articles from the study aim to results is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of included studies (N = 15).

| First Author, (Year), Country | Purpose | Sample | Method | Analysis | Results | CASP Quality Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pavlopoulou (2020) | To investigate TD sisters’ experiences in a co-established research process. | 11 TD sisters, 13–14 years old, 9 older, 1 younger, 1 twin of ASD siblings (10–14 years old, 9 male) | Photovoice methodology | Thematic analysis | • 8 themes: difficulties with routines; acceptance of ASD is more important than awareness; positive feelings; strengths and resources; finding out what works as a family; witnessing parental struggles; advocacy; support needs | 10 |

| Greece | Interviews | |||||

| Focus groups | ||||||

| Pavlopoulou (2019) | To investigate the experience of TD sisters who have an ASD sibling. | 9 TD sisters, 12–14 years old, 6 older than ASD siblings (10–14 years old, 7 male) | Interviews | Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis | • 4 themes: interactions with ASD sibling; interactions with parents; practical struggles of caring; TD sibling’s needs | 10 |

| UK | ||||||

| Costa (2019) | To understand and analyse the perceptions of TD siblings who have an ASD sibling. | 6 TD siblings, 10–12 years old, 4 female, 3 younger than ASD sibling (5–13 years old, 5 male) | Interviews | Content analysis and a category system used for inductive and deductive analysis | • Greater knowledge and understanding of ASD leads to less embarrassment and increased ability to cope. • Discrepancy with level of parental availability and attention between TD and ASD sibling. • Attitudes of others can be difficult. |

8 |

| Portugal | ||||||

| Tsai (2018) | To describe experiences of mothers and TD siblings of children with Autism in two cultural contexts. | 14 TD siblings | Interviews | Interpretative phenomenological analysis | • 4 themes: influence of ASD; family resilience; what we do as a family; the support needed. • Marked differences in experiences between countries. |

10 |

| Taiwan/UK | • UK: 7 TD siblings 9–13 years old, 3 female, 5 older than ASD siblings (5–15 years old, all male) • Taiwan: 7 TD siblings 9–17 years old, 5 female, 2 older than ASD siblings (5–18 years old, 5 male) |

|||||

| 14 mothers (7 from each country) | ||||||

| Gorjy (2017) | To explore how TD siblings who have an ASD sibling view their lives. | 11 TD adolescent siblings, 12–17 years old, 3 female, one twin and all others were older than ASD sibling (6–15 years old, 9 male) | Interviews | Nvivo 10: thematic analysis | • 6 themes: ‘it’s hard’; ‘it’s different’; ‘it affects my life’; ‘adaption’; ‘it’s worth it’; “but it’s normal for us’. | 10 |

| Australia | ||||||

| Corsano (2017) | To explore the experiences of TD siblings who have a brother with ASD. | • 14 TD siblings, 12–20 years old, 9 male, 11 older than ASD sibling (12–20 years old, all male) | Interviews | Content analysis | • 6 themes: attitudes towards ASD sibling; perceptions; precocious sense of responsibility; concern about the future; friendship difficulties; the need to talk. | 10 |

| Italy | 14 Mothers | |||||

| Ward (2016) | To gain TD sibling’s perspectives of living with an ASD sibling and to examine differences in age, birth order and gender. | 16 families | Interviews | Open coding and development of themes | • 2 themes: positive and negative experiences • Multiple differences in perceptions according to age, birth order and gender of the TD sibling. |

9 |

| USA | • 22 TD siblings (7 came from 3 families), 7–18 years old, 11 female, 12 older, 2 twins. | |||||

| Cridland (2016) | To investigate the experiences of TD siblings of younger brothers with ASD and how best to support them. | 3 families | Interviews | Nvivo: coding and development of themes | • 4 themes: roles at school; roles at home; tension with family system; adjustment to having an ASD sibling. | 10 |

| Australia | • 3 TD adolescent sisters, 16–17 years old, all older than their brother with ASD (13-15 years old) • 3 mothers • 2 fathers |

|||||

| Chan (2014) | To explore the coping ability of TD siblings who have an ASD sibling and how they contribute to the dynamics of familial relationships. | 5 families | Interviews | Nvivo 10: coding and development of themes | • 3 themes: double-standard parenting; strategies and responses to this; mother’s relationship with TD child. | 9 |

| Singapore | • 5 mothers • 5 TD siblings, 9–13 years old, 3 male, 3 younger than ASD sibling (9–13 years old, all male) |

|||||

| Petalas (2012) | To explore how TD siblings of brothers who have ASD make sense of their unique circumstances and experiences. | 12 TD siblings, 14–17 years old, 6 male, 3 younger than sibling with ASD (4–18 years old, all male) | Interviews | Interpretative phenomenological analysis | • 6 themes: negative impact of siling’s ASD; impact of other’s reactions; influence of past experiences; acceptance and tolerance towards ASD sibling; positive experiences; future concerns. | 9 |

| UK | ||||||

| Angell (2012) | To investigate experiences of TD siblings who had an ASD and identify their self-reported support needs. | 12 TD siblings, 7–15 years old, 6 male, two twins, 5 younger than sibling with ASD (6–15 years old, 11 male) | Interviews | Cross-case analysis with a constant comparative method | • 3 themes: descriptions of the sibling subsystem; cohesion between siblings; adaptability of the TD sibling. • Some differences in experiences based on age and birt order of TD siblings. |

9 |

| USA | ||||||

| Hwang (2010) | To explore TD children’s experiences and perspectives of living with an ASD sibling. | 9 TD siblings, 7–15 years old, 5 male, 4 younger than sibling with ASD (6–18 years old, 8 male) | Video diaries | Unclear | • Stigmatising attitudes of others caused TD siblings to feel shame. • TD siblings have the ability to reframe negative experiences, are resilient and can cope. |

8 |

| Korea | Home movies | |||||

| Interviews | ||||||

| Petalas (2009) | To investigate perceptions and experiences of TD siblings, who had a brother with ASD. | 8 TD siblings, 9–12 years old, 3 male, one twin, 3 younger than ASD sibling (8–17 years old, all male) | Interviews | Interpretative phenomenological analysis | • 5 themes: impact of their brother’s ASD on their lives; attitudes of others; tolerance and acceptance of ASD sibling; positive attitudes and experiences; support needs | 9 |

| UK | ||||||

| Benderix (2007) | To describe TD siblings’ experiences of having a sibling with ASD and LD. | 5 families | Interviews | Content analysis | • 7 content categories: precocious responsibility; feeling sorry; exposed to frightening behaviour; impact on friendships; empathetic feelings; hope a group home would cause relief; physical violence made TD siblings feel unsafe and anxious. | 10 |

| Sweden | • 14 TD siblings, 5–29 years old, 8 male, 10 older than ASD sibling | |||||

| Mascha (2006) | To pilot a method encouraging TD siblings to talk about their experience of having an ASD sibling. | 11 families | Interviews | Content analysis | • Method used is appropriate for future research. • TD siblings reported both positive and negative experiences. • Attitudes of others towards the sibling with ASD were also a concern. |

8 |

| UK | • 14 TD siblings, 11–18 years old, 10 female, 12 older than ASD sibling (7–20 years) |

Note. ASD = autism spectrum disorder; TD = typically developing; DS = downs syndrome; DAMP = deficits in attention, motor control and perception; LD = learning disability.

The majority of identified articles were from Europe (N = 8) with other represented continents including: Australia (N = 2), USA (N = 2), Asia (N = 2) and one cross-cultural study (Taiwan/UK). Most studies used interviews to collect data (Angell et al., 2012; Benderix & Sivberg, 2007; Chan & Goh, 2014; Corsano et al., 2017; Costa & da Silva Pereira, 2019; Cridland et al., 2016; Gorjy et al., 2017; Mascha & Boucher, 2006; Pavlopoulou & Dimitriou, 2019; Petalas et al., 2009, 2012; Tsai et al., 2018 and Ward et al., 2016). The remaining two studies asked participants to take photos and/or videos, combined with interviews and focus groups (Hwang & Charnley, 2010; Pavlopoulou & Dimitriou, 2020).

A combined total of 164 TD siblings of individuals with ASD were included across the studies, with study sample sizes ranging from three to 22. Just over half (56.7%) of TD siblings were female; they ranged in age from five to 29 years old, two thirds (65.85%) were older than their sibling with ASD and there were seven twins (4.27%). While two studies (Benderix & Sivberg, 2007; Corsano et al., 2017) included TD siblings aged 18<, they were still included in this review as at least half of participants were under 18. The majority of studies (N = 8) did not report on any ethnicity characteristic; however, where this was described, there was a propensity for participants or their families to be Caucasian.

Quality assessment

All 15 studies were of high quality based on criteria used in previous systematic reviews (e.g. Carolan et al., 2018) as they all received ‘yes’ answers for 8 to 10 of 10 CASP checklist questions (CASP, 2019). However, in the majority of studies it was unclear whether, or how, the diagnosis of the child with ASD had been independently confirmed. Similarly, in almost all studies the presence (or absence) of co-morbid mental health conditions and/or learning disabilities of the child with ASD were not accounted for.

Following the process of thematic synthesis (Thomas & Harden, 2008), four analytical themes were generated. These included: (i) impact on self and personal development; (ii) interaction with their sibling with ASD; (iii) interaction with others and (iv) experiences of coping.

Impact on self and personal development

TD sibling’s spoke about the positive impact their sibling with ASD has had on their own personal attributes, such as increased empathy and understanding; developed ability to cope, compromise and feel good about helping out (e.g. Angell et al., 2012; Benderix & Sivberg, 2007; Chan & Goh, 2014; Corsano et al, 2017; Cridland et al., 2016; Gorjy et al., 2017; Mascha & Boucher, 2006; Pavlopoulou & Dimitriou, 2019, 2020; Petalas et al., 2012; Ward et al., 2016). In contrast, many siblings spoke of responsibilities that may be above what would be expected of their developmental age and stage. For example: protecting their sibling with ASD from being bullied or from hurting themselves or others; increased amount of household duties and taking responsibility for their sibling’s care to allow their parents to take a break (e.g. Angell et al., 2012; Benderix & Sivberg, 2007; Corsano et al., 2017; Cridland et al., 2016; Gorjy et al., 2017; Mascha & Boucher, 2006; Ward et al., 2016). Many also expressed concerns about their own and their sibling with ASD’s future (e.g. Benderix & Sivberg, 2007; Corsano et al., 2017; Mascha & Boucher, 2006; Pavlopoulou & Dimitriou, 2020; Petalas et al., 2012; Tsai et al., 2018). However, some TD siblings reported that while the responsibilities placed on them increased as they grew older, their understanding, protection and acceptance of their sibling’s ASD had also increased over time (e.g. Corsano et al., 2016; Cridland et al., 2016; Ward et al., 2016). Furthermore, TD siblings in Hwang and Charnley (2010) and Gorjy et al’s (2017) studies reported that they had used, or wanted to use, their unique platform as having a sibling with ASD to raise awareness, fundraise and promote the acceptance of people with ASD generally.

Interaction with their sibling with ASD

Many TD siblings described being proud of their sibling with ASD (e.g. Angell et al., 2012; Costa & da Silva Pereira, 2019; Pavlopoulou & Dimitriou, 2020; Petalas et al., 2009) and appreciated how unique, smart and funny they are (e.g. Costa & da Silva Pereira, 2019; Mascha & Boucher, 2006; Petalas et al., 2009, 2012; Ward et al., 2016). TD siblings also expressed enjoyment of having someone they could play with (e.g. Corsano et al., 2017; Costa & da Silva Pereira, 2019; Mascha & Boucher, 2006; Petalas et al., 2009, 2012; Ward et al., 2016 ), although difficulties with having to deal with problematic and sometimes unpredictable behaviour were often cited. For example they reported experiencing problems with their sibling’s aggression, meltdowns and social and communication difficulties (e.g. Angell et al., 2012; Costa & da Silva Pereira, 2019; Cridland et al., 2016; Gorjy et al., 2017; Mascha & Boucher, 2006; Petalas et al., 2009, 2012; Tsai et al., 2018; Ward et al., 2016). Unsurprisingly, these negative experiences also weighed heavily on the TD sibling’s wellbeing, with many expressing feelings of upset, discomfort, shame, embarrassment, anger, fear, social isolation, concern and feeling ‘burnt out’ (e.g. Angell et al., 2012; Benderix & Sivberg, 2007; Corsano et al., 2017; Cridland et al., 2016; Mascha & Boucher, 2006; Petalas et al., 2009, 2012; Tsai et al., 2018).

Interaction with others

The majority of TD siblings expressed unsurprising feelings of anger, frustration, upset, hurt and embarrassment if subject to negative attitudes, or disapproving comments from others, about their sibling with ASD (e.g. Costa & da Silva Pereira, 2019; Gorjy et al., 2017; Hwang & Charnley, 2010; Pavlopoulou & Dimitriou, 2020; Petalas et al., 2009, 2012). They also spoke about the impact the sibling with ASD had on their friendships and social life. For example, some felt unable to invite friends home, did not feel able to tell others they had a sibling with ASD, or felt as though they needed to explain their sibling’s ‘problem’ (e.g. Benderix & Sivberg, 2007; Corsano et al, 2017; Gorjy et al, 2017; Mascha and Boucher, 2006). In contrast, some TD siblings expressed times where they were grateful for the emotional and practical support offered by friends and extended family members, when perhaps their parents could not (e.g. Cridland et al, 2016; Petalas et al., 2012). Similarly, many TD siblings reported experiencing differential parenting to their sibling with ASD. This included having less access or attention to/from parents and being subject to different expectations than the child with ASD (e.g. Chan & Goh, 2014; Costa & da Silva Pereira, 2019; Cridland et al., 2016; Tsai et al., 2018; Ward et al., 2016).

Experiences of coping

Some TD siblings seemed to report developing less than ideal coping strategies. For example, they expressed feeling as though they needed to change their own behaviour, such as having to ‘give in’ to the child with ASD in order to avoid further conflict and would keep things to themselves, as they did not want to further burden their parents (e.g. Angell et al., 2012; Tsai et al., 2018). Similarly, TD siblings in Benderix and Sivberg’s (2007) study noted that due to their fear of physical violence, they would retreat and self-isolate from the rest of the family. However, through discussions with some TD siblings, they were found to have developed the ability to compromise and strategise in order to cope and overcome the difficulties they faced from having a sibling with ASD (e.g. Chan & Goh, 2014; Pavlopoulou & Dimitriou, 2020).

Discussion

This review aimed to summarise the experience of TD siblings who have a sibling diagnosed with an ASD. To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first systematic review which has focused directly on the experience of being a TD sibling of a child with an ASD, without comparison to another population or merged with the experience of older TD siblings who grew up when the landscape of healthcare and structure of mental health services was vastly different. Across the 15 studies included in this review, four themes emerged which synthesised the lived experience of the 164 TD siblings who participated in the research: (i) impact on self and personal development; (ii) interactions with their sibling with ASD; (iii) interactions with others and (iv) experiences of coping.

Consistent with previous research focusing on the TD and ASD sibling relationship (e.g. Saxena & Adamsons, 2013) and sibling interventions (e.g. Banda, 2015), we found that TD siblings report a range of experiences of having a brother or sister with ASD and a myriad of feelings encompassed within these. However, it is important to challenge the often widely held assumption that having a child with ASD in the family is all ‘doom and gloom’. For example, we found that many TD siblings described the positive influence having a sibling with ASD has had on their personal development, including their desire to promote the acceptance of people with ASD in wider society. Similarly, interactions with their sibling with ASD allowed for the development of pride and appreciation of their unique personality characteristics.

While this may be the case, recognition of the toll having a sibling with ASD can have on TD sibling’s lives is imperative (e.g. Leedham et al., 2020; Orsmond & Seltzer, 2007). The challenges they may face in relation to interactions with their sibling, particularly when they are exhibiting problematic and unpredictable behaviour, are not to be ignored. Similarly, the emotional burden that some TD siblings of children with ASD experience will grow heavier through receipt of negative attitudes and comments when interacting with others. While it is hoped that as national awareness and acceptance of people with ASD increases, it is important to recognise the prejudice that individuals, siblings and other family members of children with ASD may still feel. For example, within this review we found that some TD siblings felt unable to invite friends to their house or did not wish to share that their sibling had ASD. This could have a significant effect on a TD sibling’s support network, especially if they are already subject to less support from their parents.

As in previous literature (e.g. Cridland et al., 2014; Macks & Reeve, 2007; Woodgate et al., 2008) we found that living with a child who has ASD can provide many benefits to a TD sibling. However, their ability to cope and the strategies they utilise need to remain a focus. For example, within this review we found that some TD siblings reported less than ideal coping strategies such as ‘giving in’ to their sibling with ASD, keeping things to themselves in order not to burden others and self-isolating to keep out of harm’s way. As suggested by Chan and Goh (2014) and Pavlopoulou and Dimitriou (2020), TD siblings do have the capabilities to adapt and cope with difficulties they face, however it is important that they are given the support to do so, in a healthy way.

Limitations

While there was variation in evidence from different countries, due to resource constraints, our review is limited by the inclusion of English-language publications within peer-reviewed journals only. Similarly, our review is also limited by the studies that it includes. For example, there was an underrepresentation of lower socioeconomic countries and a lack of information regarding the ethnicity of participants. Additionally, there was a higher proportion of female and older TD siblings, many of whom were recruited via their parents for example, through local assessment services who knew the families and/or charity network mailing lists. Furthermore, in many studies it was unclear whether the siblings who had ASD had undergone a formal diagnostic assessment and/or had any other learning, physical or mental health needs. Therefore, it is unclear whether this review captures the breadth of experience across siblings of children who have an ASD, which is a significant limitation of the studies included. Similarly, it remains to be seen how these factors may impact the results found and could be a useful source for future research.

Future directions

There are several clinical and research implications based on the literature review findings. For example, there is a clear gap in the current literature for a more in depth analysis of factors that may or may not lead to more positive experiences for TD siblings of children with ASD. For example, gathering information about whether the severity of the ASD, the cognitive ability of the child with ASD or a co-existing physical, neurodevelopmental or psychological disorder plays a role. More research is also needed in relation to the potential impact of demographic variables on TD siblings’ experiences, including but not limited to: age, gender, birth order, ethnicity and socioeconomic status.

In addition, mirroring suggestions made within all articles included in this review, and cited in the NICE (2013) guidelines, TD siblings should have an assessment of their own needs and support should be given where necessary, to enhance their experiences of coping with any challenges faced from having a sibling with ASD. For example, like Leedham et al. (2020), in the current review we found that many TD siblings spoke of precocious responsibilities, including an increased amount of household chores, less access to or attention from their parents and feeling responsible for the care and protection of their sibling with ASD. As such, it is important that TD siblings are given direct, protected time with their parents that includes the opportunity to discuss their experience(s) and concerns. TD siblings also mentioned that they felt the need to allow their parents respite from the child with ASD and as such would miss out on their own desired activities. However, it is important that TD siblings are also given their own form of respite, with parents signposted to other support networks they can draw on. In addition, we found that TD sibling’s interactions with the child who has ASD and interaction with others could have a significant impact on their own mental health. It may be helpful therefore for TD siblings to be given opportunities to develop their own coping skills to deal with feelings and challenges that may arise regarding having a sibling with ASD; which could be in the form of bespoke support groups where their experiences could be shared with likeminded individuals.

Six studies currently exist which have evaluated support or psychoeducational group interventions for TD siblings (<18 years old) of individuals who have an ASD (Brouzos et al., 2017; Gettings et al., 2015; Granat et al., 2012; Jones et al., 2020; Roberts et al., 2015; Smith & Perry, 2005). While the majority of groups included similar content (e.g. psychoeducation around their sibling’s disability, space to share experiences and learning coping and relaxation techniques); shortcomings in their designs are evident, especially in respect to control groups and sample size. For example, three of the six studies did not have a control group and all samples ranged widely in terms of heterogeneity and sample size.

While all six of the above studies concluded their group programme had been effective, it remains unclear what type of intervention would be the most useful to enhance TD sibling’s experiences of coping and there is much work to be done on unpicking this, with particular attention paid to the research methodology used. For example, there is a need for randomized controlled trials, larger sample sizes and comparisons based on the demographic factors described above. In addition, studies included in this review were limited by their cross-sectional nature and thus an emphasis on longitudinal research is needed in order to map: (i) change over time, (ii) the potential identification of different time points/ages where TD siblings need the most support and (iii) the effect that experiences TD siblings have in childhood have in adulthood, in a prospective, rather than retrospective way.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the current review found that having a sibling with ASD presents its own unique experiences which can have a significant impact on a TD sibling’s self and personal development. Interactions with their sibling with ASD present both benefits and challenges and can be greatly affected by interactions with others and a TD sibling’s experience of coping. Living with a child who has ASD is certainly not an all ‘doom and gloom’ scenario; though more work is needed to ensure that siblings achieve more rather than less positive experiences in future. The importance of enhancing TD sibling’s experiences of coping is highlighted and a range of ideas are presented. Further research is needed to identify which methods are the most effective in supporting TD siblings.

Author biographies

Lucy Watson is a final year Trainee Clinical Psychologist at the University of Surrey. Prior to her clinical training, Lucy has had extensive clinical experience in specialist Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) which increased her interest in field and clinic-based research; with specific emphasis on children who may not meet clinical threshold for CAMHS but who may equally benefit from psychological support. She hopes to continue working with children, siblings and parents post qualification.

Dr Paul Hanna is the Research Director in Clinical Psychology at the University of Surrey. His research expertise is in community psychology, mental health/wellbeing, distress, and qualitative methods. Paul has published in a range of journals including Theory and Psychology, Journal of Community and Applied Psychology, Qualitative Research, Qualitative Research in Psychology, The Australian Community Psychologist and the Journal of Consumer Culture.

Christina J Jones, PhD, is a Reader in Clinical Health Psychology at the University of Surrey where she is responsible for research methods training for the doctoral programme in clinical psychology. Christina has expertise in evidence synthesis and the development and evaluation of psychological interventions.

Appendix 1

List of keywords used in electronic search strategy

autism,

asd,

autism spectrum,

Asperger,

pervasive developmental,

siblings,

brother,

sister,

children,

adolescent,

youth,

teenager,

paediatric,

pediatric,

experience,

perception,

attitude,

view,

feeling,

perspective

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Lucy Watson  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1580-3004

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1580-3004

References

*Indicates those articles included in the systematic literature review.

- *Angell M., Meadan H., Stoner J. (2012). Experiences of siblings of individuals with autism spectrum disorders. Autism Research & Treatment, 2012, 949586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banda D. R. (2015). Review of sibling interventions with children with Autism. Education & Training in Autism & Developmental Disabilities, 50(3), 303–315. [Google Scholar]

- *Benderix Y., Sivberg B. (2007). Siblings’ experiences of having a brother or sister with autism and mental retardation: A case study of 14 siblings from five families. Journal of Paediatric Nursing, 22(5), 410–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouzos A., Vassilopoulous S. P., Tassi C. (2017). A psychoeducational group intervention for siblings of children with autism spectrum disorder. The Journal for Specialists in Group Work, 42(4), 274–298. [Google Scholar]

- Carolan C. M., Smith A., Davies G. R., Forbat L. (2018). Seeking, accepting and declining help for emotional distress in cancer: A systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative evidence. European Journal of Cancer Care, 27(2), e12720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Chan G. W. L., Goh E. C. L. (2014). ‘My parents told us that they will always treat my brother differently because he is autistic’ - are siblings of autistic children the forgotten ones? Journal of Social Work Practice, 28(2), 155–171. [Google Scholar]

- *Corsano P., Musetti A., Guidotti L., Capelli F. (2017). Typically developing adolescents’ experience of growing up with a brother with an autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disabilities, 42(2), 151–161. [Google Scholar]

- *Costa T. M., da Silva Pereira P. (2019). The child with autism spectrum disorder: The perceptions of siblings. Support for Learning, 34(2), 193–210. [Google Scholar]

- Cridland E. K., Jones S. C., Magee C. A., Caputi P. (2014). Family-focused autism spectrum disorder research: A review of the utility of family systems approaches. Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practice, 18(3), 213–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Cridland E. K., Jones S. C., Stoyles G., Caputi P., Magee C. A. (2016). Families living with autism spectrum disorder: Roles and responsibilities of adolescent sisters. Focus on Autism & Other Developmental Disabilities, 31(3), 196–207. [Google Scholar]

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. (2019). CASP qualitative checklist. https://casp-uk.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018_fillable_form.pdf

- Elsabbagh M., Divan G., Koh Y-J., Kim Y. S., Kauchali S., Marcín C., Montiel-Nava C., Patel V., Paula C. S., Wang C., Yasamy M. T., Fombonne E. (2012). Global prevalence of autism and other pervasive developmental disorders. Autism Research, 5(3), 160–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferraioli S., Harris S. (2010). The impact of autism on siblings. Social Work in Mental Health, 8, 41–53. [Google Scholar]

- Gettings S., Franco F., Santosh P. J. (2015). Facilitating support groups for siblings of children with neurodevelopmental disorders using audio-conferencing: A longitudinal feasibility study. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 9(1), 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giallo R., Gavidia-Payne S., Minett B., Kappor A. (2012). Sibling voices: The self-reported mental health of siblings of children with a disability. Clinical Psychologist, 16(1), 36–43. [Google Scholar]

- *Gorjy R. S., Fielding A., Falkmer M. (2017). “It’s better than it used to be”: Perspectives of adolescent siblings of children with an autism spectrum condition. Child & Family Social Work, 22, 1488–1496. [Google Scholar]

- Granat T., Nordgren I., Rein G., Sonnander K. (2012). Group intervention for siblings of children with disabilities: A pilot study in a clinical setting. Disability and Rehabilitation, 34(1), 69–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green L. (2013). The well-being of siblings of individuals with autism. ISRN Neurology, 2013, 417194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes S. A., Watson S. L. (2013). The impact of parenting stress: A meta-analysis of studies comparing the experience of parenting stress in parents of children with and without autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders, 43, 629–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Hwang S., Charnley H. (2010). Making the familiar strange and making the strange familiar: Understanding Korean children’s experience living with an autistic sibling. Disability & Society, 25(5), 579–592. [Google Scholar]

- Jones E. A., Fiani T., Stewart J. L., Neil N., McHugh S., Fienup D. M. (2020). Randomised controlled trial of a sibling support group: Mental health outcomes for siblings of children with autism. Autism, 24(6), 1468–1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaminsky L., Dewey D. (2001). Sibling relationships of children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 31(4), 399–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leedham A. T., Thompson A. R., Freeth M. (2020). A thematic synthesis of siblings’ lived experiences of autism: Distress, responsibilities, compassion and connection. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 97, 103547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberati A., Altman D. G., Tetzlaff J., Mulrow C., Gøtzsche P. C., Ioannidis J. P., Clarke M., Devereaux P. J., Kleijnen J., Moher D. (2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: Explanation and elaboration. British Medical Journal, 339, b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovell B., Wetherell M. A. (2016). The psychophysiological impact of childhood autism spectrum disorder on siblings. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 49–50, 226–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macks R. J., Reeve R. E. (2007). The adjustment of non-disabled siblings of children with autism. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders, 37, 1060–1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandleco B., Webb A. E. M. (2015). Sibling perceptions of living with a young person with down syndrome or autism spectrum disorder: An integrated review. Journal for Specialists in Pediatric Nursing, 20(3), 138–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Mascha K., Boucher J. (2006). Preliminary investigation of a qualitative method of examining siblings’ experiences of living with a child with ASD. British Journal of Developmental Disabilities, 52(1), 19–28. [Google Scholar]

- McHale S. M., Updegraff K. A., Feinberg M. E. (2016). Siblings of youth with autism spectrum disorders: Theoretical perspectives on sibling relationships and individual adjustment. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders, 46(2), 589–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHale S. M., Updegraff K. A., Whiteman S. D. (2012). Sibling relationships and influences in childhood and adolescence. Journal of Marriage & Family, 74(5), 913–930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meadan H., Halle J. W., Ebata A. T. (2010). Families with children who have autism spectrum disorders: Stress and support. Exceptional Children, 77(1), 7–36. [Google Scholar]

- Meadan H., Stoner J. B., Angell M. E. (2010). Review of literature related to the social, emotional, and behavioral adjustment of siblings of individuals with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 22, 83–100. [Google Scholar]

- McConkey R. (2020). The rise in the numbers of pupils identified by school with autism spectrum disorder (ASD): A comparison of the four countries in the United Kingdom. Support for Learning, 35(2), 132–143. [Google Scholar]

- Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. British Medical Journal, 339, b2535. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2013). Autism spectrum disorder in under 19s: Support and management. NICE guideline 170. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg170/chapter/1-Recommendations#families-and-carers-2 [PubMed]

- O’Brien I., Duffy A., Nicholl H. (2009). Impact of childhood chronic illnesses on siblings: A literature review. British Journal of Nursing, 18(22), 1358–1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onaolapo A. Y., Onaolapo O. J. (2017). Data on autism spectrum disorders prevalence: A review of facts, fallacies and limitations. Universal Journal of Clinical Medicine, 5(2), 14–23. [Google Scholar]

- Orsmond G. I., Seltzer M. M. (2007). Siblings of individuals with autism spectrum disorders across the life course. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities, 13, 313–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Pavlopoulou G., Dimitriou D. (2020). In their own words, in their own photos: Adolescent females’ siblinghood experiences, needs and perspectives growing up with a preverbal autistic brother or sister. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 97, 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Pavlopoulou G., Dimitriou D. (2019). ‘I don’t live with autism; I live with my sister’. Sisters’ accounts on growing up with their preverbal autistic siblings. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 88, 1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Petalas M. A., Hastings R. P., Nash S., Dowey A., Reilly D. (2009). “I like that he always shows who he is”: The perceptions and experiences of siblings with a brother with autism spectrum disorder. International Journal of Disability, Development & Education, 56(4), 381–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Petalas M. A., Hastings R. P., Nash S., Reilly D., Dowey A. (2012). The perceptions and experiences of adolescent siblings who have a brother with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 37(4), 303–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts R. M., Ejova A., Giallo R., Strohm K., Lillie M., Fuss B. (2015). A controlled trial of the Sibworks group program for siblings of children with special needs. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 43–44, 21–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxena M., Adamsons K. (2013). Siblings of individuals with disabilities: Reframing the literature through a bioecological lens. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 5(4), 300–316. [Google Scholar]

- Shivers C., Jackson J. B., McGregor C. M. (2019). Functioning among typically developing siblings of individuals with autism spectrum disorder: A meta-analysis. Clinical Child & Family Psychology Review, 22, 172–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith L. O., Elder J. H. (2010). Siblings and family environments of person with autism spectrum disorder: A review of the literature. Journal of Child & Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 23(3), 189–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith T., Perry A. (2005). A sibling support group for brothers and sisters of children with autism. Journal of Developmental Disabilities, 11(1), 77–88. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas J., Harden A. (2008). Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 8(1): 45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas S., Reddy K., Sagar J. V. (2015). Psychosocial issues of siblings of children with autism spectrum disorder. International Journal of Advanced Research, 3, 119–124. [Google Scholar]

- *Tsai H.-W. J., Cebula K., Liang S. H., Fletcher-Watson S. (2018). Siblings’ experience of growing up with children with autism in Taiwan and the United Kingdom. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 83, 206–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsao L. L., Davenport R., Schmiege C. (2012). Supporting siblings of children with autism spectrum disorders. Early Childhood Education Journal, 40(1), 47–54. [Google Scholar]

- *Ward B., Smith Tanner B., Mandleco B., Dyches T. T., Freeborn D. (2016). Sibling experiences: Living with young persons with autism spectrum disorders. Paediatric Nursing, 42(2), 69–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson L., Jones C. J., Hanna P. (2019). A systematic review exploring the experiences of siblings of children with autism spectrum disorders and what support is available for them? PROSPERO: International prospective register of systematic reviews. CRD42019143164. https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42019143164

- Woodgate R. L., Ateah C., Secco L. (2008). Living in a word of our own: The experience of parents who have a child with Autism. Qualitative Health Research, 18, 1075–1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation. (2018). International classification of diseases for mortality and morbidity statistics (11th Revision). https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en#/http://id.who.int/icd/entity/437815624