Abstract

This cross-sectional study aims to develop validated models to estimate the probability of dialysis after nephrectomy and partial nephrectomy.

Postoperative kidney failure requiring dialysis significantly increases in-hospital and long-term mortality.1,2 A major challenge in nephrectomy is estimating the probability of postoperative dialysis. Because of its rarity (0.5% to 2.1%),3,4 to our knowledge, there are no validated models to estimate this probability. We developed externally validated nomograms to compute this probability after nephrectomy and partial nephrectomy (PN).

Methods

We queried all 6 637 415 patients included in the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) database between January 2005 and December 2017. We selected all patients who underwent open or minimally invasive radical nephrectomy, nephroureterectomy, simple nephrectomy, or PN for any indication. We excluded all patients who received dialysis preoperatively or had bilateral nephrectomies, kidney mass ablation, or traumatic nephrectomies. The NSQIP database excludes patients admitted for trauma or any transplant procedure(s). All remaining emergent nephrectomies were included. Because data were publicly available and deidentified, the University of Nebraska Medical Center Institutional Review Board waived the study.

Using NSQIP data from 2005 to 2017, 2 models were generated: one for nephrectomy (including simple nephrectomy, radical nephrectomy, and nephroureterectomy) and one for PN. t Tests or χ2 tests assessed associations between preoperative variables and postoperative dialysis within 30 days postoperatively, as appropriate. While race reported in the NSQIP database was incorporated to calculate glomerular filtration, caution should be used when doing this.5,6 Variables with univariable P values less than .10 were included in multivariable logistic regression models. Backward selection with stay criteria of a P value less than .05 selected variables for the nomograms. The nomograms were validated with 2018 NSQIP data. Data for 2018 postoperative dialysis probabilities were compared with known 2018 postoperative dialysis status to generate calibration plots and C statistics. Deciles of the log of these predicted probabilities were defined; the proportion of patients with postoperative dialysis were plotted against the midpoint of the predicted probability of each decile (eMethods in the Supplement). Statistical analysis was conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute). Two-sided P values less than .05 were considered statistically significant. Using the Shiny package in R version 4.0.3 (R Core Team), we developed an online calculator for each nomogram.

Results

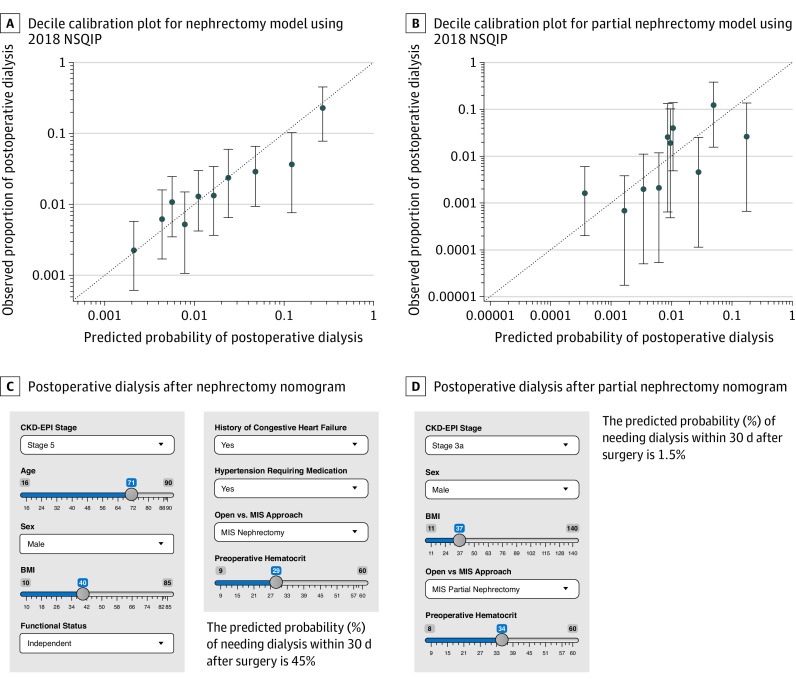

Of the 56 334 included patients, 23 139 (41.1%) were female, and the mean (SD) age was 60.9 (13.4) years. A total of 358 patients (1.1%) received postoperative dialysis after nephrectomy and 114 (0.5%) after PN. The Table shows baseline characteristics and univariable and multivariable models for the nephrectomy cohort (n = 32 555) and PN cohort (n = 23 779). In the 2018 validation cohort, postoperative dialysis probabilities derived from the nomograms were similar to actual rates (Figure, A and B). C statistics for individuals treated between 2005 and 2017 and in 2018 indicated good performance of the nephrectomy nomogram (2005 to 2017: C statistic = 0.835; 2018: C statistic = 0.761) and PN nomogram (2005 to 2017: C statistic = 0.870; 2018: C statistic = 0.789). C statistics for nephrectomy and PN models incorporating only chronic kidney disease stage (CKD-S) were 0.785 and 0.804, respectively, indicating that the covariables helped predict postoperative dialysis. Although hematocrit levels are low in patients with advanced CKD-S, the interaction between hematocrit level and CKD-S was not significant in the nephrectomy and PN models. When CKD-S was held constant, hematocrit level remained significantly associated with postoperative dialysis. Online calculators for nephrectomy and PN nomograms are accessible at https://nephrectomypostopdialysis.shinyapps.io/CompleteModel/ (Figure, C) and https://nephrectomypostopdialysis.shinyapps.io/PartialModel/ (Figure, D), respectively.

Table. Univariable and Multivariable Analyses for Postoperative Dialysis After Nephrectomy and Partial Nephrectomy.

| Covariable | Nephrectomy | Partial nephrectomy | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Postoperative dialysis | Univariable, P value | Final multivariable modela | Postoperative dialysis | Univariable, P value | Final multivariable modela | |||||

| Yes (n = 358) | No (n = 32 197) | AOR (95% CI)b | P value | Yes (n = 114) | No (n = 23 665) | AOR (95% CI)b | P value | |||

| Categorical variables | ||||||||||

| CKD stage | ||||||||||

| Stage 1 | 21 (0.3) | 6723 (99.7) | <.001 | 1 [Reference] | <.001 | 5 (0.1) | 7430 (99.9) | <.001 | 1 [Reference] | <.001 |

| Stage 2 | 62 (0.5) | 11 728 (99.5) | 1.70 (1.02-2.83) | 32 (0.4) | 8771 (99.6) | 5.07 (1.97-13.02) | ||||

| Stage 3a | 50 (1.1) | 4610 (98.9) | 3.44 (2.02-5.87) | 23 (1.0) | 2268 (99.0) | 11.87 (4.49-31.38) | ||||

| Stage 3b | 61 (2.5) | 2369 (97.5) | 7.60 (4.46-12.96) | 18 (1.8) | 986 (98.2) | 17.82 (6.52-48.70) | ||||

| Stage 4 | 80 (11.0) | 644 (89.0) | 32.33 (19.00-55.01) | 23 (8.4) | 252 (91.6) | 67.62 (24.60-185.87) | ||||

| Stage 5 | 37 (22.2) | 130 (77.8) | 65.79 (36.14-119.76) | 4 (13) | 27 (87) | 118.45 (28.40-494.05) | ||||

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Female | 100 (0.7) | 13 447 (99.3) | <.001 | 1 [Reference] | <.001 | 24 (0.2) | 9568 (99.8) | <.001 | 1 [Reference] | <.001 |

| Male | 258 (1.4) | 18 738 (98.6) | 2.18 (1.67-2.84) | 90 (0.6) | 14 091 (99.4) | 3.24 (1.97-5.32) | ||||

| Hispanic | ||||||||||

| No | 295 (1.1) | 25 357 (98.9) | .26 | NA | NA | 100 (0.5) | 19 513 (99.5) | .81 | NA | NA |

| Yes | 20 (0.9) | 2228 (99.1) | NA | NA | 7 (0.5) | 1499 (99.5) | NA | NA | ||

| Race | ||||||||||

| Other | 13 (1.2) | 1074 (98.8) | .001 | NA | NA | 6 (0.7) | 885 (99.3) | .18 | NA | NA |

| Black | 45 (1.9) | 2290 (98.1) | NA | NA | 17 (0.8) | 2229 (99.2) | NA | NA | ||

| White | 256 (1.1) | 23 822 (98.9) | NA | NA | 84 (0.5) | 17 472 (99.5) | NA | NA | ||

| Surgical approach | ||||||||||

| MIS | 165 (0.8) | 21 511 (99.2) | <.001 | 1 [Reference] | <.001 | 41 (0.2) | 16 321 (99.8) | <.001 | 1 [Reference] | <.001 |

| Open | 193 (1.8) | 10 686 (98.2) | 1.76 (1.39-2.24) | 73 (1.0) | 7344 (99.0) | 3.16 (2.09-4.77) | ||||

| Diabetes | ||||||||||

| Nondiabetic | 237 (0.9) | 25 756 (99.1) | <.001 | NA | NA | 75 (0.4) | 18 890 (99.6) | .001 | NA | NA |

| Non–insulin dependent | 56 (1.3) | 4291 (98.7) | NA | NA | 25 (0.7) | 3320 (99.3) | NA | NA | ||

| Insulin dependent | 65 (2.9) | 2150 (97.1) | NA | NA | 14 (1.0) | 1455 (99.0) | NA | NA | ||

| Smoking | ||||||||||

| No | 294 (1.1) | 25 649 (98.9) | .25 | NA | NA | 98 (0.5) | 19 118 (99.5) | .16 | NA | NA |

| Yes | 64 (1.0) | 6548 (99.0) | NA | NA | 16 (0.4) | 4547 (99.6) | NA | NA | ||

| Functional status | ||||||||||

| Independent | 334 (1.0) | 31 446 (99.0) | <.001 | 1 [Reference] | .03 | 114 (0.5) | 23 442 (99.5) | >.99 | NA | NA |

| Dependent | 22 (3.4) | 631 (96.6) | 1.81 (1.05-3.14) | 0 | 158 (100) | NA | NA | |||

| Pulmonary disease | ||||||||||

| No | 324 (1.0) | 30 460 (99.0) | .001 | NA | NA | 109 (0.5) | 22 753 (99.5) | .63 | NA | NA |

| Yes | 34 (1.9) | 1737 (98.1) | NA | NA | 5 (0.5) | 912 (99.5) | NA | NA | ||

| Ascites | ||||||||||

| No | 355 (1.1) | 32 160 (98.9) | .01 | NA | NA | 113 (0.5) | 23 654 (99.5) | .06 | NA | NA |

| Yes | 3 (7) | 37 (93) | NA | NA | 1 (8) | 11 (92) | NA | NA | ||

| Congestive heart failure | ||||||||||

| No | 338 (1.0) | 31 955 (99.0) | <.001 | 1 [Reference] | .02 | 111 (0.5) | 23 582 (99.5) | .01 | NA | NA |

| Yes | 20 (7.6) | 242 (92.4) | 2.14 (1.13-4.04) | 3 (3) | 83 (97) | NA | NA | |||

| Hypertension | ||||||||||

| No | 63 (0.5) | 12 466 (99.5) | <.001 | 1 [Reference] | .004 | 22 (0.2) | 9693 (99.8) | <.001 | NA | NA |

| Yes | 295 (1.5) | 19 731 (98.5) | 1.62 (1.17-2.24) | 92 (0.6) | 13 972 (99.4) | NA | NA | |||

| Disseminated cancer | ||||||||||

| No | 327 (1.1) | 30 033 (98.9) | .15 | NA | NA | 110 (0.5) | 23 310 (99.5) | .10 | NA | NA |

| Yes | 31 (1.4) | 2164 (98.6) | NA | NA | 4 (1.1) | 355 (98.9) | NA | NA | ||

| Steroid use | ||||||||||

| No | 330 (1.1) | 30 828 (98.9) | .001 | NA | NA | 111 (0.5) | 23 007 (99.5) | >.99 | NA | NA |

| Yes | 28 (2.0) | 1369 (98.0) | NA | NA | 3 (0.4) | 658 (99.6) | NA | NA | ||

| Weight loss | ||||||||||

| No | 343 (1.1) | 31 376 (98.9) | .05 | NA | NA | 111 (0.5) | 23 479 (99.5) | .06 | NA | NA |

| Yes | 15 (1.8) | 820 (98.2) | NA | NA | 3 (1.6) | 186 (98.4) | NA | NA | ||

| Preoperative transfusion | ||||||||||

| No | 339 (1.1) | 31 789 (98.9) | <.001 | NA | NA | 113 (0.5) | 23 627 (99.5) | .17 | NA | NA |

| Yes | 19 (4.4) | 408 (95.6) | NA | NA | 1 (3) | 38 (97) | NA | NA | ||

| Preoperative sepsis | ||||||||||

| No | 339 (1.1) | 31 695 (98.9) | <.001 | NA | NA | 113 (0.5) | 23 576 (99.5) | .32 | NA | NA |

| Yes | 19 (3.8) | 478 (96.2) | NA | NA | 1 (1) | 80 (99) | NA | NA | ||

| Emergency surgery | ||||||||||

| No | 345 (1.1) | 31 977 (98.9) | <.001 | NA | NA | 114 (0.5) | 23 627 (99.5) | >.99 | NA | NA |

| Yes | 13 (5.6) | 220 (94.4) | NA | NA | 0 | 38 (100) | NA | NA | ||

| Continuous variables | ||||||||||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 65.1 (12.2) | 62.2 (13.9) | <.001 | 0.99 (0.98-0.999) | .03 | 64.9 (11.0) | 59.0 (12.4) | <.001 | NA | NA |

| BMI, mean (SD)c | 31.5 (8.1) | 30.1 (7.1) | .001 | 1.03 (1.01-1.04) | .001 | 33.2 (8.1) | 30.8 (6.8) | .003 | 1.04 (1.01-1.06) | .002 |

| Preoperative WBC level, mean (SD), /μL | 8.4 (4.4) | 7.8 (2.9) | .01 | NA | NA | 7.7 (2.2) | 7.3 (2.5) | .11 | NA | NA |

| Preoperative hematocrit level, mean (SD), % | 35.9 (6.6) | 39.4 (5.5) | <.001 | 0.97 (0.95-0.99) | .002 | 38.7 (5.3) | 41.5 (4.4) | <.001 | 0.93 (0.90-0.97) | <.001 |

| Preoperative platelet level, mean (SD), ×103 cells/μL | 237.7 (99.4) | 258.0 (94.9) | <.001 | NA | NA | 217.2 (63.5) | 241.0 (70.7) | <.001 | NA | NA |

Abbreviations: AOR, adjusted odds ratio; BMI, body mass index; CKD, chronic kidney disease; MIS, minimally invasive surgery; NA, not applicable; WBC, white blood cell count.

SI conversion factors: To convert WBC to ×109/L, multiply by 0.001; and platelets to ×109/L, multiply by 1.

NA indicates the variable did not meet stay criteria during backward selection and was therefore not included in the multivariable model.

AOR was adjusted for other variables with reported AORs in that same model.

Calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

Figure. Calibration Plots and Sample Nomogram Calculators for Nephrectomy and Partial Nephrectomy Models.

A and B, Calibration plot for nephrectomy (A) and partial nephrectomy (B) models derived from external validation with 2018 National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) data. The dashed diagonal line represents situation when predicted probability of dialysis is perfectly calibrated with actual incidence of dialysis. Error bars (95% CIs) represent performance of the 2005-2017 nomogram applied to 2018 NSQIP data. C and D, Sample images of preoperative nomogram calculator estimating probability of postoperative dialysis after nephrectomy (C) or partial nephrectomy (D). BMI indicates body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); CKD-EPI, Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation; MIS = minimally invasive surgery.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to develop 2 externally validated nomograms using preoperative multi-institutional data to compute postoperative dialysis probability: one for nephrectomy and one for PN. While nomograms traditionally use multistep calculations, we translated ours into user-friendly calculators that are accessible in real time with patients.

Patients with CKD undergoing nephrectomy or PN wish to understand their postoperative dialysis risk. However, it is challenging to estimate this objectively. Our calculators address this dilemma. Preoperatively, they serve as decision support tools by empowering patients to make informed decisions. They improve how clinicians discuss postoperative dialysis, provide informed consent, and involve nephrologists or palliative care professionals. Intraoperatively, they may motivate dialysis catheter placement or surgical techniques that preserve kidney function. Postoperatively, they help clinicians manage expectations with patients who require dialysis.

Study limitations include the inability to identify patients with a solitary kidney, prior kidney surgery, uneven differential kidney function, transplanted kidney, or short-term vs permanent postoperative dialysis in the NSQIP database as well as selection bias with larger hospitals participating in NSQIP.

eMethods. Describing Validation of Nomogram with 2018 NSQIP Data.

References

- 1.Coca SG, Yusuf B, Shlipak MG, Garg AX, Parikh CR. Long-term risk of mortality and other adverse outcomes after acute kidney injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53(6):961-973. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.11.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lafrance JP, Miller DR. Acute kidney injury associates with increased long-term mortality. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21(2):345-352. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009060636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dozier KC, Yeung LY, Miranda MA Jr, Miraflor EJ, Strumwasser AM, Victorino GP. Death or dialysis? the risk of dialysis-dependent chronic renal failure after trauma nephrectomy. Am Surg. 2013;79(1):96-100. doi: 10.1177/000313481307900137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schmid M, Krishna N, Ravi P, et al. Trends of acute kidney injury after radical or partial nephrectomy for renal cell carcinoma. Urol Oncol. 2016;34(7):293.e1-293.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2016.02.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Norris KC, Eneanya ND, Boulware LE. Removal of race from estimates of kidney function: first, do no harm. JAMA. 2021;325(2):135-137. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.23373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diao JA, Wu GJ, Taylor HA, et al. Clinical implications of removing race from estimates of kidney function. JAMA. 2021;325(2):184-186. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.22124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods. Describing Validation of Nomogram with 2018 NSQIP Data.