This systematic review and meta-analysis examines the emotional and psychological sequelae of hair loss in both men and women as measured by various quality-of-life and psychological tests.

Key Points

Question

Is androgenetic alopecia associated with patients’ health-related quality of life?

Findings

In this systematic review and meta-analysis of 41 studies with 7995 patients, the pooled Dermatology Life Quality Index score for androgenetic alopecia was higher than for other common dermatoses. The pooled Hair-Specific Skindex-29 score showed moderate impairment in the emotion dimension of this assessment tool, whereas the pooled Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale score did not show an association with depression.

Meaning

Results of this study show an association between androgenetic alopecia and moderate impairment of not only health-related quality of life but also emotions, suggesting that patients with this disease may need psychological and psychosocial support.

Abstract

Importance

Androgenetic alopecia (AGA) is associated with trichodynia, anxiety, low self-esteem, and depression, which have implications for quality of life. However, no systematic evaluation has been performed on the association of AGA with health-related quality of life (HRQOL).

Objective

To systematically examine the association of AGA with HRQOL and psychiatric disorders.

Data Sources

Cochrane Library, PubMed, Embase, and WanFang databases were searched from inception through January 24, 2021.

Study Selection

Case series, case-control studies, cross-sectional studies, cohort studies, and randomized clinical trials that examined either HRQOL or psychiatric disorders in patients with AGA were included. Studies published in languages other than English and Mandarin were excluded.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) reporting guideline was used. The risk of bias in included studies was assessed with the Risk of Bias in Non-randomized Studies of Intervention (ROBINS-I) tool. A random-effects model meta-analysis was performed to calculate the pooled effect on HRQOL. A subgroup analysis according to sex and geographic regions was also conducted.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The outcome was HRQOL of patients with AGA.

Results

A total of 41 studies involving 7995 patients was included. The pooled Dermatology Life Quality Index score was 8.16 (95% CI, 5.62-10.71). The pooled Hair-Specific Skindex-29 score indicated moderate impairment of emotions, with the meta-analysis showing a score of 29.22 (95% CI, 24.17-34.28) in the emotion dimension. The pooled Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale score did not indicate depression, with the meta-analysis showing a score of 14.98 (95% CI, 14.28-15.68). Factors that had a direct association with HRQOL included married or coupled status and receipt of medical treatments, whereas factors that had an inverse association with HRQOL included higher self-rated hair loss severity, lower visual analog scale score, and higher educational level.

Conclusions and Relevance

This systematic review and meta-analysis found a significant association of AGA with moderate impairment of HRQOL and emotions, but no association was found with depressive symptoms. The findings suggest that patients with AGA may need psychological and psychosocial support.

Introduction

As the most common type of hair loss, androgenetic alopecia (AGA) affects about 53% of European-American men aged 40 to 49 years in the United States and up to 90% in their lifetime.1 Androgenetic alopecia is less prevalent in women and Asian individuals, affecting approximately 20% of men aged 40 to 49 years and 12% of women older than 70 years in China,2 14.1% of men and 5.6% of women at all ages in Korea,3 and 63% of men aged 17 to 86 years in Singapore.4 As an androgen-dependent trait, male-pattern hair loss is also strongly associated with multiple genetic factors.5 The cause of female-pattern hair loss is less well understood, but genetic predisposition is believed to play an important role. Androgenetic alopecia is characterized by the progressive recession of the frontal hairline followed by a vertex thinning and balding in men and diffuse hair thinning over the vertex scalp in women.6

As a part of self-image, hair is a social construct that is strongly connected to one’s identity. Hair loss affects self-image, causes trichodynia, and plays a role in emotions and social activity, which may be associated with psychiatric problems and impaired health-related quality of life (HRQOL).7,8,9 Willimann and Trüeb10 reported that patients with AGA were troubled not only by change in appearance but also by trichodynia, anxiety, low self-esteem, and depression. However, no systematic evaluation has been performed of the association of AGA with HRQOL. In this systematic review and meta-analysis, we aimed to systematically examine not only the association of AGA with HRQOL but also the association of AGA with psychiatric disorders.

Methods

We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) reporting guideline.11 We registered the study protocol with PROSPERO.

Literature Search and Study Selection

The Cochrane Library, PubMed, Embase, and WanFang databases were searched for relevant studies from inception through January 24, 2021. The search strategy is listed in eTable 1 in the Supplement.

Studies that met the following criteria were included: (1) the study population was composed of patients with AGA, and (2) the outcomes reported included HRQOL or psychiatric disorders. Studies published in languages other than English and Mandarin were excluded. Faced with multiple publications with the same subject matter, we chose the study that reported HRQOL data and extracted relevant data from the other studies. Two of us (C.-H.H. and Y.F.) independently screened studies that met the criteria by scanning titles and abstracts. We then assessed the full text of potentially eligible studies. Discrepancies were resolved by a discussion with the third author (C.-C.C.).

Data Extraction and Risk-of-Bias Assessment

Two of us (C.-H.H. and Y.F.) independently reviewed the included studies and extracted the following data: (1) name of authors, (2) study design (eg, cohort study, randomized clinical trial, and cross-sectional survey), (3) study period, (4) country in which the study was performed, (5) profiles of patients (ie, sample size, sex, age, disease duration, and hair loss severity), (6) assessment tools and summary scales, (7) confounding factors associated with HRQOL (eg, age, sex, family history of alopecia, educational level, marital status, age at alopecia onset, and severity of alopecia).

The risk of bias of included studies was assessed according to the Risk of Bias in Non-randomized Studies of Intervention (ROBINS-I) tool.12 For randomized clinical trials that compared the efficacy of different interventions in treating AGA and for case series that measured the efficacy of medicine in treating AGA, we extracted only the baseline data of participants to analyze their HRQOL and psychiatric status. Therefore, we also used the ROBINS-I tool to assess the risk of bias in participant enrollment and HRQOL measurement.

Statistical Analysis

After extracting the data, we used RevMan, version 5.4.1 (Cochrane Training), to perform a meta-analysis with at least 3 studies that reported data for each HRQOL or psychological assessment tool.13 We calculated the mean, SD, and 95% CI for each result. Moderate heterogeneity across the included studies was considered when the I2 statistic exceeded 50%.14 The random-effects model was adopted in conducting meta-analyses because of anticipated clinical heterogeneity. We also conducted subgroup analyses on the basis of sex and geographic regions. Tests of subgroup using the methods in the Cochrane handbook14 were performed to obtain P values. A 2-sided P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

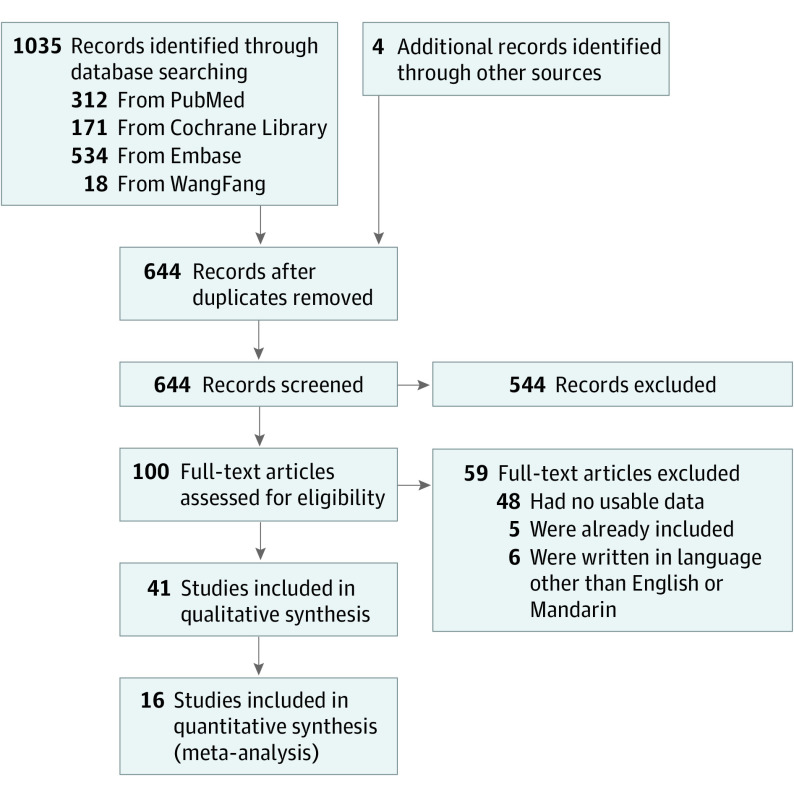

The database search identified 1035 records, and 4 relevant studies were provided by one of us (C.-C.C.). A total of 644 studies remained after removal of duplicates, and further exclusion of 544 citations by screening the titles and abstracts resulted in the full text of 100 studies being assessed for eligibility. Of these 100 full-text articles, 41 were included in this study. The PRISMA flowchart is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. PRISMA Study Flowchart.

We included 41 studies that involved a total of 7995 patients. These studies were conducted in the following countries: China (n = 9),15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23 Turkey (n = 5),24,25,26,27,28 Italy (n = 4),29,30,31,32 the United States (n = 3),33,34,35 India (n = 3),36,37,38 Korea (n = 2),39,40 Pakistan (n = 2),41,42 Greece (n = 2),43,44 Brazil (n = 1),45 Spain (n = 1),46 Nepal (n = 1),47 Malaysia (n = 1),48 Colombia (n = 1),49 Canada (n = 1),50 Japan (n = 1),51 Finland (n = 1),52 Germany (n = 1),53 Australia (n = 1),54 and Egypt (n = 1).55 Of the included studies, 6 were case-control studies,26,27,30,34,35,50 29 were cross-sectional surveys,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,29,31,33,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,46,47,48,49,51,53,54,55 2 were case series,28,32 1 was a population-based cohort study,52 and 3 were randomized clinical trials.43,44,45 The characteristics and results of HRQOL assessment are shown in eTable 2 in the Supplement.

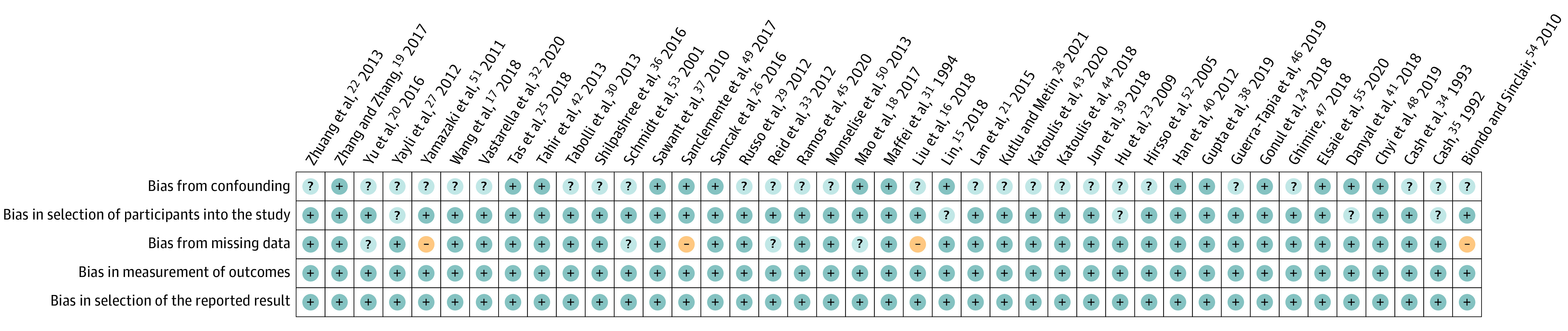

Risk of Bias of Included Studies

Of the 41 included studies, 26 (63%) were rated with unclear risk in the domain of bias from confounding.16,17,20,21,22,23,27,28,29,30,32,33,34,35,36,39,43,44,45,46,47,50,51,52,53,54 The main reason for an unclear risk of bias was that most studies did not report the exclusion criteria for the study population; however, patients with psychiatric disorders or other underlying diseases that might have affected HRQOL should be excluded. Five studies (12%) were rated with unclear risk in the domain of bias in selection of participants into the study because either the method of AGA diagnosis was not reported or the diagnosis was made by a non–health care professional.15,23,27,35,41 Four studies (10%) were rated with unclear risk,18,20,33,53 and 4 studies (10%) were rated with high risk in the domain of bias from missing data.16,49,51,54 Missing data of 20% or more were defined as having a high risk of bias, and missing data between 5% and 20% were considered to have an unclear risk.56 All studies were rated as low risk in both domains of bias in measurement of outcomes and bias in selection of the reported result. The risk of bias of included studies is summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Risk of Bias of Included Studies.

Dots with + indicate low risk of bias; ?, unclear risk of bias; and −, high risk of bias.

HRQOL or Psychological Assessment Instruments

A total of 11 different types of HRQOL assessment tools and 29 different types of psychological assessment instruments were used by the included studies. The HRQOL assessment tools included Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) (n = 16),15,18,19,20,21,22,23,28,29,38,42,43,44,47,48,51 Hair-Specific Skindex-29 (n = 6),27,38,39,40,46,49 Hairdex questionnaire (n = 3),24,37,53 Symptom Checklist-90-Revised (n = 3),17,31,37 Women’s Androgenetic Alopecia Quality of Life index (n = 3),32,45,54 World Health Organization Quality of Life-BREF (n = 2),51,55 12-Item Short Form Survey (n = 2),30,46 RAND 36-Item Health Survey (n = 1),52 Skindex-16 (n = 1),33 Dermatology Quality of Life instrument in Turkish (n = 1),24 and Modified Women’s Androgenetic Alopecia Quality of Life index (n = 1).36

The psychological assessment instruments included the Beck Depression Inventory (n = 3),25,27,52 Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) (n = 3),15,18,23 Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (n = 3),16,25,41 Visual Analog Scale (VAS) (n = 3),21,22,51 Self-Rating Depression Scale (n = 2),20,41 Beck Anxiety Inventory (n = 2),25,27 State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (n = 2),29,51 Toronto Alexithymia Scale (n = 1),30 12-Item General Health Questionnaire (n = 1),30 Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (n = 1),20 Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (n = 1),41 Social Phobia Inventory (n = 1),29 Social Interaction Anxiety Scale (n = 1),29 Self-Consciousness Scale (n = 1),34 Female Sexual Function Index (n = 1),26 Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced Inventory (n = 1),30 Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire (n = 1),20 Big Five Inventory (n = 1),29 Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire-Short Form (n = 1),29 Self-Perception Scale (n = 1),25 Arizona Sexual Experience Scale (n = 1),25 Stressful Life Event Scale (n = 1),37 Emotional Quotient Inventory (n = 1),50 Lifestyle Indices (n = 1),37 Multidimensional Body-Self Relations Questionnaire (n = 1),34 Texas Social Behavior Inventory (n = 1),34 Levenson 24-Item Locus of Control Scale (n = 1),34 15-Item Impact of Event Scale (n = 1),34 and Hair Loss Effects Questionnaire (n = 1).35

HRQOL, Depression, and Self-esteem Scores

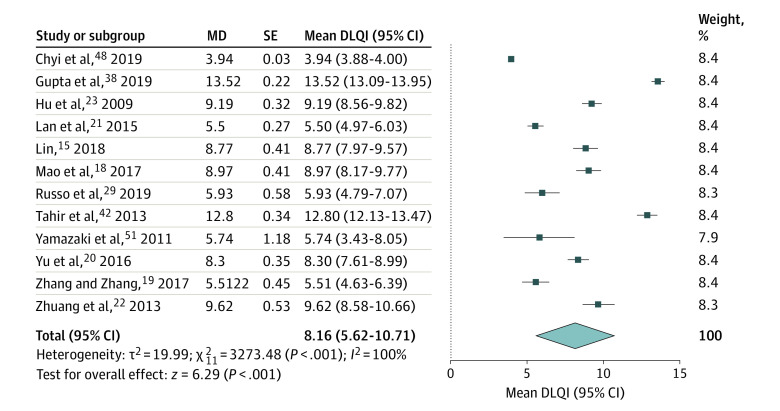

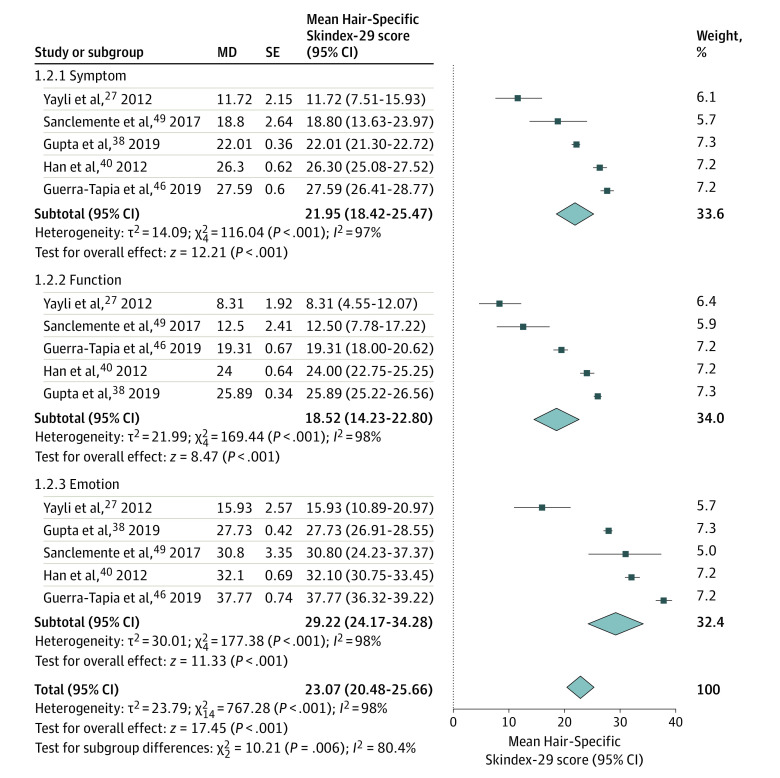

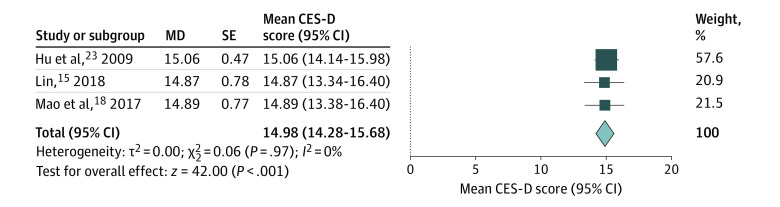

The data on DLQI, Hair-Specific Skindex-29, and CES-D were available for meta-analysis. The meta-analysis showed a pooled DLQI score of 8.16 (95% CI, 5.62-10.71) (Figure 3). Subgroup analysis of DLQI scores found no significant differences between men and women (7.94 [95% CI, 4.46-11.42] vs 10.10 [95% CI, 7.40-12.79]; P = .34) (eFigure 1 in the Supplement) or between European and Asian countries (5.93 [95% CI, 4.79-7.07] vs 8.36 [95% CI, 5.66-11.06]; P = .10) (eFigure 2 in the Supplement). The meta-analysis on Hair-Specific Skindex-29 showed scores of 21.95 (95% CI, 18.42-25.47) in symptom dimension, 18.52 (95% CI, 14.23-22.80) in function dimension, and 29.22 (95% CI, 24.17-34.28) in emotion dimension (Figure 4). The meta-analysis on CES-D showed a score of 14.98 (95% CI, 14.28-15.68) (Figure 5).

Figure 3. Forest Plots of Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) of Patients With Androgenetic Alopecia.

The meta-analysis illustrated a significant impairment of quality of life in patients with androgenetic alopecia (pooled DLQI, 8.16; 95% CI, 5.62-10.71). MD indicates mean difference.

Figure 4. Forest Plots of Hair-Specific Skindex-29 Scores of Patients With Androgenetic Alopecia.

The meta-analysis illustrated moderate impairment in emotion dimension (pooled score, 29.22; 95% CI, 24.17-34.28) and mild impairment in both symptom (pooled score, 21.95; 95% CI, 18.42-25.47) and function (pooled score, 18.52; 95% CI, 14.23-22.80) dimensions. MD indicates mean difference.

Figure 5. Forest Plots of Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) Score of Patients With Androgenetic Alopecia.

The meta-analysis illustrated no depression in patients with androgenetic alopecia (pooled CES-D score, 14.98; 95% CI, 14.28-15.68). MD indicates mean difference.

Three studies used the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale to evaluate self-esteem among patients with AGA.16,25,41 The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale consisted of 10 items that were scored from either 0 to 3 or 1 to 4, with a cutoff score for low self-esteem of lower than 15 or 25 individually. Tas et al25 scored each item from 0 to 3 and reported significantly lower self-esteem among women with female-pattern hair loss compared with men with AGA (mean [SD] score, 11.57 [2.88] vs 15.76 [5.33]; P < .001). Liu et al16 scored each item from 1 to 4 and reported a mean (SD) score of 29.79 (5.75) among men with pre–hair graft AGA. Danyal et al41 did not describe how each item was scored and reported mean (SD) scores of 16.46 (1.07) for men with AGA with mild hair loss and 17.3 (1.0) for men with AGA with severe hair loss.

Factors Associated With HRQOL

A total of 27 studies (66%)16,17,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,29,30,33,34,35,36,37,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,51,53,55 reported 18 factors associated with HRQOL (eTable 3 in the Supplement). Of these factors, married or coupled status (n = 5)21,23,35,36,42 and receipt of either topical or oral medicines (n = 7)22,43,44,45,46,51,55 had a direct association with HRQOL. Factors such as higher self-rated hair loss severity or lower VAS score (n = 3),21,22,33 and higher educational level (n = 3),17,23,42 had an inverse association with HRQOL. Physician-rated hair loss severity was not a factor in HRQOL, and neither was treatment response. Inconsistent or limited data were found for the other 12 factors.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this systematic review and meta-analysis was the first to examine HRQOL in patients with AGA. The study showed that AGA had an association with moderate impairment of HRQOL, especially in the emotion dimension of the Hair-Specific Skindex-29 tool. The subgroup analysis of DLQI scores found no statistically significant differences in HRQOL between men and women or between European and Asian countries. Married or coupled status and a history of receiving topical or oral medical treatments had a direct association with HRQOL, whereas higher self-rated hair loss severity, lower VAS score, and higher educational level had an inverse association. We also found no association between AGA and depression, and the current evidence on self-esteem was limited.

Androgenetic alopecia has been associated with varying degrees of distress and adverse psychological sequelae, especially in women.7 Schielein et al57 found significant impairment of quality of life in patients with hair loss because of internalized and external stigmatization. Davis and Callender58 reported statistically significant psychological burden and impairment of HRQOL in patients with female-pattern hair loss. Younger age, absence of a romantic relationship, self-esteem that is built on physical appearance, and desire for medical treatment for AGA were found to have unfavorable psychological implications for patients with AGA.59

These previous findings were consistent with the results of the present study and support the meta-analysis outcome that AGA was associated with greater impairment in the emotion dimension than in symptom and function dimensions. Furthermore, subjective satisfaction and HRQOL assessments were inconsistent with objective evaluations. Significant depressive symptom was indicated when the CES-D score was 16 or higher.60 We found a pooled CES-D score of 14.98. The emotion dimension of the Hair-Specific Skindex-29 combines the responses to questions about worry, embarrassment, shame, frustration, and depression. Depression accounts for only a part of the emotion dimension. Therefore, emotion dimension could be impaired even if no depressive symptoms were noted. For these reasons, AGA warrants appropriate psychological and psychosocial support.

Inconsistent results were noted in the comparisons of HRQOL between the sexes. We extracted DLQI scores from 7 studies and performed a subgroup analysis but found no significant differences in HRQOL between men and women (7.94 vs 10.10; P = .34).21,22,23,29,38,42,51 However, significant differences in HRQOL between men and women were reported in 5 studies,25,29,30,34,42 with use of different assessment tools. Further studies should be conducted to examine the association of AGA with HRQOL in men vs women.

Among non-Hispanic White patients, AGA has been found to be more prevalent and severe than among Asian patients61; thus, patients in areas with lower prevalence of AGA are presumed to suffer from higher psychological burden than those in areas with higher prevalence. However, our results showed no significant differences in DLQI scores between patients with AGA in European and Asian countries. This finding may be confounded by the limited number of European (n = 1) vs Asian studies (n = 11).

We found that physician-rated hair loss severity was not a factor associated with HRQOL in AGA. Patients with moderate or very mild hair loss tended to experience more distress than those with mild or severe hair loss because the latter group had adapted to hair loss, as reported by some studies.25,41,62 However, the hair loss assessment instrument and classification of severity in each evaluation tool varied among the included studies, which may account for the inconsistent findings.

Compared with other skin diseases, AGA had a higher pooled DLQI score (8.16) than alopecia areata (6.3),63 contact dermatitis (7.35), and acne vulgaris (7.45), but the pooled DLQI score for AGA was lower than for vitiligo (9.11), urticaria (9.8), psoriasis (10.53), and atopic dermatitis (11.2).64 However, additional head-to-head studies are needed for direct comparisons of HRQOL in patients with various dermatoses.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, most of the included studies adopted a cross-sectional design. Many studies did not exclude patients with chronic diseases or psychiatric disorders, which might have confounded their quality of life. The sequence of appearance of AGA and psychiatric disorders was also unknown. Second, the outcomes were evaluated by various HRQOL assessment tools in different studies, and thus meta-analyses were not performed for many tools because of the few studies that used them. Third, most studies provided total scores only, and not the specific score of each domain; therefore, we could not draw the true implications of AGA for different patient aspects. Fourth, only 3 studies in China were available for assessing depression and another 3 studies were available for evaluating self-esteem in patients with AGA. More relevant studies are thus warranted, especially in women with female-pattern hair loss.

Conclusions

This systematic review and meta-analysis was the first, to our knowledge, to examine HRQOL, depression, and self-esteem in patients with AGA. It illustrated the association of AGA with moderate impairment of HRQOL, which was greater than for alopecia areata and other common dermatoses, such as contact dermatitis and acne vulgaris. In addition, AGA was associated with moderate impairment in emotions, which was greater than in the symptom and function dimensions; the association with depressive symptoms was not significant. Patients with AGA deserve attention and appropriate psychological and psychosocial support.

eTable 1. Search Strategy

eTable 2. Summary of Included Studies

eTable 3. Factors Associated With Health-Related Quality of Life in Androgenetic Alopecia

eFigure 1. Dermatology Life Quality Index Score in Androgenetic Alopecia Patients of Different Sexes

eFigure 2. Dermatology Life Quality Index Score in Androgenetic Alopecia Patients in Asia and Europe

References

- 1.Rhodes T, Girman CJ, Savin RC, et al. Prevalence of male pattern hair loss in 18-49 year old men. Dermatol Surg. 1998;24(12):1330-1332. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1998.tb00009.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang TL, Zhou C, Shen YW, et al. Prevalence of androgenetic alopecia in China: a community-based study in six cities. Br J Dermatol. 2010;162(4):843-847. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09640.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paik JH, Yoon JB, Sim WY, Kim BS, Kim NI. The prevalence and types of androgenetic alopecia in Korean men and women. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145(1):95-99. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04289.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tang PH, Chia HP, Cheong LL, Koh D. A community study of male androgenetic alopecia in Bishan, Singapore. Singapore Med J. 2000;41(5):202-205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nyholt DR, Gillespie NA, Heath AC, Martin NG. Genetic basis of male pattern baldness. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;121(6):1561-1564. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1747.2003.12615.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Piraccini BM, Alessandrini A. Androgenetic alopecia. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2014;149(1):15-24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cash TF. The psychosocial consequences of androgenetic alopecia: a review of the research literature. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141(3):398-405. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1999.03030.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hunt N, McHale S. The psychological impact of alopecia. BMJ. 2005;331(7522):951-953. doi: 10.1136/bmj.331.7522.951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kivanç-Altunay I, Savaş C, Gökdemir G, Köşlü A, Ayaydin EB. The presence of trichodynia in patients with telogen effluvium and androgenetic alopecia. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42(9):691-693. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2003.01847.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Willimann B, Trüeb RM. Hair pain (trichodynia): frequency and relationship to hair loss and patient gender. Dermatology. 2002;205(4):374-377. doi: 10.1159/000066437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016;355:i4919. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Treadwell JR, Tregear SJ, Reston JT, Turkelson CM. A system for rating the stability and strength of medical evidence. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2006;6:52. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-6-52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deeks JJ, Higgins JPT, Altman DG. Analysing data and undertaking meta-analyses. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, et al. , eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.1. Cochrane Training; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin HB. Investigation and study of the quality of life and depression in patients with androgenetic alopecia and alopecia areata. China Modern Med. 2018;25(23):4. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu F, Miao Y, Li X, et al. The relationship between self-esteem and hair transplantation satisfaction in male androgenetic alopecia patients. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2018;18(5):1441-1447. doi: 10.1111/jocd.12839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang X, Xiong C, Zhang L, et al. Psychological assessment in 355 Chinese college students with androgenetic alopecia. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97(31):e11315. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000011315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mao Y, Dai Y, Sun C, Xu A. Analysis of quality of life and depression in patients with androgenetic alopecia or alopecia areata. Chinese J Dermatol. 2017;50(5):4. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang M, Zhang N. Quality of life assessment in patients with alopecia areata and androgenetic alopecia in the People’s Republic of China. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2017;11:151-155. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S121218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu NL, Tan H, Song ZQ, Yang XC. Illness perception in patients with androgenetic alopecia and alopecia areata in China. J Psychosom Res. 2016;86:1-6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2016.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lan XM, Tan H, Yang XC. Evaluation of the quality of life in male patients with androgenetic alopecia. J Clin Dermatol. 2015;44(7):417-419. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhuang XS, Zheng YY, Xu JJ, Fan WX. Quality of life in women with female pattern hair loss and the impact of topical minoxidil treatment on quality of life in these patients. Exp Ther Med. 2013;6(2):542-546. doi: 10.3892/etm.2013.1126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hu XP, Wang WJ, Zhong QI, Yu B, Ma G. Questionnaire analysis of related factors of male pattern alopecia and clinical efficacy of finasteride therapy in 320 patients. J Xi'an Jiaotong University (Medical Sciences). 2009;30(5):620-623. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gonul M, Cemil BC, Ayvaz HH, Cankurtaran E, Ergin C, Gurel MS. Comparison of quality of life in patients with androgenetic alopecia and alopecia areata. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93(5):651-658. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20186131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tas B, Kulacaoglu F, Belli H, Altuntas M. The tendency towards the development of psychosexual disorders in androgenetic alopecia according to the different stages of hair loss: a cross-sectional study. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93(2):185-190. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20185658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sancak EB, Oguz S, Akbulut T, et al. Female sexual dysfunction in androgenetic alopecia: case-control study. Can Urol Assoc J. 2016;10(7-8):E251-E256. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.3582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yayli S, Tiryaki A, Doǧan S, Iskender B, Bahadir S. The role of stress in alopecia areata and comparison of life quality of patients with androgenetic alopecia and healthy controls. Turkderm -Turk Arch Dermatol Venereol. 2012;46(3):134-137. doi: 10.4274/Turkderm.79653 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kutlu Ö, Metin A. Systemic dexpanthenol as a novel treatment for female pattern hair loss. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20(4):1325-1330. doi: 10.1111/jocd.13729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Russo PM, Fino E, Mancini C, Mazzetti M, Starace M, Piraccini BM. HrQoL in hair loss-affected patients with alopecia areata, androgenetic alopecia and telogen effluvium: the role of personality traits and psychosocial anxiety. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33(3):608-611. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tabolli S, Sampogna F, di Pietro C, Mannooranparampil TJ, Ribuffo M, Abeni D. Health status, coping strategies, and alexithymia in subjects with androgenetic alopecia: a questionnaire study. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14(2):139-145. doi: 10.1007/s40257-013-0010-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maffei C, Fossati A, Rinaldi F, Riva E. Personality disorders and psychopathologic symptoms in patients with androgenetic alopecia. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130(7):868-872. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1994.01690070062009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vastarella M, Cantelli M, Patrì A, Annunziata MC, Nappa P, Fabbrocini G. Efficacy and safety of oral minoxidil in female androgenetic alopecia. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33(6):e14234. doi: 10.1111/dth.14234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reid EE, Haley AC, Borovicka JH, et al. Clinical severity does not reliably predict quality of life in women with alopecia areata, telogen effluvium, or androgenic alopecia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66(3):e97-e102. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.11.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cash TF, Price VH, Savin RC. Psychological effects of androgenetic alopecia on women: comparisons with balding men and with female control subjects. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29(4):568-575. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(93)70223-G [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cash TF. The psychological effects of androgenetic alopecia in men. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26(6):926-931. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(92)70134-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shilpashree P, Clarify S, Jaiswal AK, Shashidhar T. Impact of female pattern hair loss on the quality of life of patients. J Pakistan Assoc Dermatologists. 2016;26(4):347-352. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sawant N, Chikhalkar S, Mehta V, Ravi M, Madke B, Khopkar U. Androgenetic alopecia: quality-of-life and associated lifestyle patterns. Int J Trichology. 2010;2(2):81-85. doi: 10.4103/0974-7753.77510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gupta S, Goyal I, Mahendra A. Quality of life assessment in patients with androgenetic alopecia. Int J Trichology. 2019;11(4):147-152. doi: 10.4103/ijt.ijt_6_19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jun M, Keum DI, Lee S, Kim BJ, Lee WS. Quality of life with alopecia areata versus androgenetic alopecia assessed using Hair Specific Skindex-29. Ann Dermatol. 2018;30(3):388-391. doi: 10.5021/ad.2018.30.3.388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Han SH, Byun JW, Lee WS, et al. Quality of life assessment in male patients with androgenetic alopecia: result of a prospective, multicenter study. Ann Dermatol. 2012;24(3):311-318. doi: 10.5021/ad.2012.24.3.311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Danyal M, Shah SIA, Ul Hassan MS, Qureshi W. Impact of androgenetic alopecia on the psychological health of young men. Pakistan J Med Health Sci. 2018;12(1):406-410. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tahir K, Aman S, Nadeem M, Kazmi AH. Quality of life in patients with androgenetic alopecia. Ann King Edward Med University. 2013;19(2):150-154. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Katoulis AC, Liakou AI, Koumaki D, et al. A randomized, single-blinded, vehicle-controlled study of a topical active blend in the treatment of androgenetic alopecia. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33(4):e13734. doi: 10.1111/dth.13734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Katoulis AC, Liakou AI, Alevizou A, et al. Efficacy and safety of a topical botanical in female androgenetic alopecia: a randomized, single-blinded, vehicle-controlled study. Skin Appendage Disord. 2018;4(3):160-165. doi: 10.1159/000480024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ramos PM, Sinclair RD, Kasprzak M, Miot HA. Minoxidil 1 mg oral versus minoxidil 5% topical solution for the treatment of female-pattern hair loss: a randomized clinical trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82(1):252-253. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.08.060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guerra-Tapia A, Buendía-Eisman A, Ferrando Barbera J; en representación del grupo de validación Hair Specific Skindex-29; Componentes del grupo de Validación Hair Specific Skindex-29 . Final phase in the validation of the cross-cultural adaptation of the Hair-Specific Skindex-29 questionnaire into Spanish: sensitivity to change and correlation with the 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2019;110(10):819-829. doi: 10.1016/j.ad.2019.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ghimire RB. Impact on quality of life in patients who came with androgenetic alopecia for hair transplantion surgery in a clinic. JNMA J Nepal Med Assoc. 2018;56(212):763-765. doi: 10.31729/jnma.3500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chyi LW, Tan ESS, Lee CK, Rehman N, Chao LW, Keat TC. Quality of life in adults with androgenic alopecia. Indian J Public Health Res Dev. 2019;10(4):1120-1125. doi: 10.5958/0976-5506.2019.00860.X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sanclemente G, Burgos C, Nova J, et al. ; Asociación Colombiana de Dermatología y Cirugía Dermatológica (Asocolderma) . The impact of skin diseases on quality of life: a multicenter study. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2017;108(3):244-252. doi: 10.1016/j.ad.2016.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Monselise A, Bar-On R, Chan L, Leibushor N, McElwee K, Shapiro J. Examining the relationship between alopecia areata, androgenetic alopecia, and emotional intelligence. J Cutan Med Surg. 2013;17(1):46-51. doi: 10.2310/7750.2012.12003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yamazaki M, Miyakura T, Uchiyama M, Hobo A, Irisawa R, Tsuboi R. Oral finasteride improved the quality of life of androgenetic alopecia patients. J Dermatol. 2011;38(8):773-777. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2010.01126.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hirsso P, Rajala U, Laakso M, Hiltunen L, Härkönen P, Keinänen-Kiukaanniemi S. Health-related quality of life and physical well-being among a 63-year-old cohort of women with androgenetic alopecia; a Finnish population-based study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2005;3:49. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-3-49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schmidt S, Fischer TW, Chren MM, Strauss BM, Elsner P. Strategies of coping and quality of life in women with alopecia. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144(5):1038-1043. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04195.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Biondo S, Sinclair R.. Quality of life in Australian women with female pattern hair loss. Open Dermatol J. 2010;4:90-94. doi: 10.2174/1874372201004010090 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Elsaie LT, Elshahid AR, Hasan HM, Soultan FAZM, Jafferany M, Elsaie ML. Cross sectional quality of life assessment in patients with androgenetic alopecia. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33(4):e13799. doi: 10.1111/dth.13799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Higgins JPT, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Sterne JAC. Assessing risk of bias in a randomized trial. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, et al. , eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.1. Cochrane Training; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schielein MC, Tizek L, Ziehfreund S, Sommer R, Biedermann T, Zink A. Stigmatization caused by hair loss—a systematic literature review. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2020;18(12):1357-1368. doi: 10.1111/ddg.14234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Davis DS, Callender VD. Review of quality of life studies in women with alopecia. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2018;4(1):18-22. doi: 10.1016/j.ijwd.2017.11.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cash TF. The psychology of hair loss and its implications for patient care. Clin Dermatol. 2001;19(2):161-166. doi: 10.1016/S0738-081X(00)00127-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR, Roberts RE, Allen NB. Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) as a screening instrument for depression among community-residing older adults. Psychol Aging. 1997;12(2):277-287. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.12.2.277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Otberg N, Finner AM, Shapiro J. Androgenetic alopecia. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2007;36(2):379-398. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2007.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kranz D. Young men’s coping with androgenetic alopecia: acceptance counts when hair gets thinner. Body Image. 2011;8(4):343-348. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2011.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rencz F, Gulácsi L, Péntek M, Wikonkál N, Baji P, Brodszky V. Alopecia areata and health-related quality of life: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175(3):561-571. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Basra MK, Fenech R, Gatt RM, Salek MS, Finlay AY. The Dermatology Life Quality Index 1994-2007: a comprehensive review of validation data and clinical results. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159(5):997-1035. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08832.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Search Strategy

eTable 2. Summary of Included Studies

eTable 3. Factors Associated With Health-Related Quality of Life in Androgenetic Alopecia

eFigure 1. Dermatology Life Quality Index Score in Androgenetic Alopecia Patients of Different Sexes

eFigure 2. Dermatology Life Quality Index Score in Androgenetic Alopecia Patients in Asia and Europe