Abstract

Over 25% of the adult population in the United States suffers from multiple chronic conditions, with numbers continuing to rise. Those with multiple chronic conditions often experience symptoms or symptom clusters that undermine their quality of life and ability to self-manage. Importantly, symptom severity in those with even the same multiple chronic conditions varies, suggesting that the mechanisms driving symptoms in patients with multiple chronic conditions are not fixed but may differ in ways that could make them amenable to targeted interventions. In this manuscript we describe at a metabolic level, the symptom experience of persons with multiple chronic conditions, including how symptoms may synergize or cluster across multiple chronic conditions to augment one’s symptom burden. To guide this discussion, we consider the metabolites and metabolic pathways known to span multiple adverse health conditions and associate with severe symptoms of fatigue, depression, and anxiety and their cluster. We also describe how severe versus mild symptoms, and their associated metabolites and metabolic pathways, may vary, depending on the presence of covariates; two of which, sex as a biological variable and the contribution of gut microbiota dysbiosis, are discussed in additional detail. Intertwining metabolomics and symptom science into nursing research, offers the unique opportunity to better understand how the metabolites and metabolic pathways affected in those with multiple chronic conditions may initiate or exacerbate symptom presence within a given individual, ultimately allowing clinicians to develop targeted interventions to improve the health quality of patients their families.

Keywords: symptom science, multiple chronic conditions, metablomics, sickness behavior

Chronic and Multiple Chronic Conditions

In 2017, the RAND Report identified the nine leading chronic health conditions affecting persons in the United States of America (U.S.) to include hypertension (HTN), heart disease, diabetes, cancer, stroke, chronic bronchitis, emphysema, asthma, and kidney disease (Buttorff et al., 2017). In the U.S., the most prevalent of these is HTN, affecting 27.4% of men and 26.5% of women (Buttorff et al., 2017).

Multiple chronic conditions (MCCs), defined as two or more single chronic conditions, each lasting at least a year, that limit activities of daily living, and require on-going medical attention, are also increasing (McPhail, 2016). MCCs afflict from 25%–40% of U.S. citizens, rising to over 80% for those 65 years of age and older (Hayes et al., 2016; McPhail, 2016; Ozdemir & Dotto, 2017; Salzberg et al., 2016; Tisminetzky et al., 2017). The most common clusters of MCCs include at least one of the following: hypertension, diabetes, and cancer, in that order (Pearson et al., 2012). MCCs are more common in women, often suggested to be related to women’s longer lifespan compared to men’s, although other factors less well-studied may play a role as well, including sex as a biological variable. For those with MCCs, both health-related quality of life and functional ability are affected (McPhail, 2016). The Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, from nearly a decade ago (2009–2011) identified that nearly 70% of total health care spending in the U.S. was directed toward providing care for citizens with MCCs (Catlin, 2015); since then numbers and costs have risen (U.S. Census Bureau, 2015; Catlin, 2015). Given the aging of the population, the number of Americans with multiple chronic conditions is expected to increase even further (Holmes, 2016; Rocca et al., 2014).

Sickness Symptoms

Over 30 years ago, a cadre of symptoms, including depression, fatigue, and anxiety, were coined “sickness symptoms” as they often were reported to accompany acute infection (Arnett & Clark, 2012; Corwin, 2000a, 2000b; Dantzer, 2001; Straub, 2012). Over the ensuing decades, these same symptoms were identified to accompany many single and multiple chronic conditions as well, including at least six of the nine identified previously (Freid, 2012): heart disease, diabetes, cancer, stroke, emphysema, and kidney disease (Arnett & Clark, 2012; Straub, 2012, 2017). Since then, research has uncovered a number of underlying processes that contribute to the development of sickness symptoms, ultimately narrowing in on two complex and interrelated processes: inflammation and oxidative stress (Jones, 2006; Khansari et al., 2009; Maes et al., 2011; Martin-Subero et al., 2016; McCusker & Kelley, 2013; Poon et al., 2015). Although these underlying mechanisms have been considered in-depth in regard to their presence in individuals suffering from a single chronic condition, untangling the potentially synergistic, or even antagonistic, mechanisms by which symptoms are expressed in patients with MCCs, has been minimally reported, most likely due to the difficulty in separating unique symptom pathways in a given individual. One approach to understanding the etiology of individual symptoms in patients with MCCs that has not yet, to our knowledge, been considered, is through the lens of metabolomics.

Metabolomics

Metabolomics is an emerging technology that uses an omic approach with revolutionary analytical capabilities to characterize and identify the specific molecules and biochemical pathways participating in physiological and biochemical activities of interest (Horgan et al., 2009; Jones et al., 2012). As stated in a recent white paper by Beger et al. (2016), “…the metabolic state of a person reflects what is encoded by the genome, and modified by diet, environmental factors, and the gut microbiome” (p. 15). Compared to traditional approaches, metabolomics provides researchers and clinicians the ability to identify at a molecular level, what is happening in the body. This allows for a mechanistic understanding and the ability to identify specific targets for intervention. Although not yet focusing on MCCs, metabolomic researchers have leveraged this ability to identify molecules and metabolic pathways associated with several single chronic conditions, including cancer initiation and progression, the development and progress of Alzheimer’s Disease, and the cellular consequences of type 2 diabetes, to identify just a few (Armitage & Barbas, 2014; Jiang et al., 2019; Yang, 2020).

Although generally comprehensive in referencing the advances in metabolomics related to specific chronic conditions (Beger et al., 2016), neither the white paper nor the literature overall addresses or mentions symptoms. Recent technological advances in the field, however, provide a unique opportunity for clinicians and scientists to explore a new framework for symptom science, one that accounts for the variability, clustering, and synergy of symptoms in a given individual, or differences in symptom expression among groups of individuals with the same single or multiple chronic conditions. Utilization of metabolomic technology within this framework has the potential to improve patient assessment and targeted nursing intervention.

Purpose

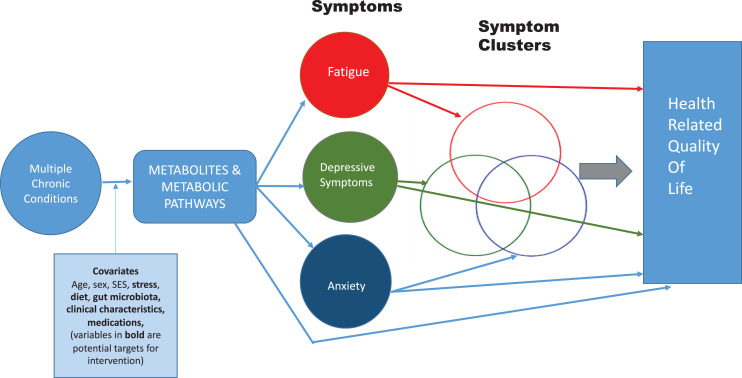

The purpose of this manuscript is to propose a new theoretical framework (Figure 1) for understanding symptom burden in patients with MCC that includes the contribution of metabolites to the development of symptoms and the contribution of symptoms to health-related quality of life. The influence of covariates is also recognized. Advantages of this approach compared to traditional symptom science approaches include the ability to better identify the molecular etiology of a symptom or a symptom cluster, thus paving the way for targeted nursing intervention and evaluation. Specifically, the framework addresses:

How MCCs injure tissues and organs, thereby activating intracellular metabolic pathways that produce cellular products that initiate symptom development. These products may accumulate as the number of diseases accumulate, worsening symptom severity;

How these cellular products may initiate not just one but several symptoms, leading to the phenomenon of symptom clustering;

How covariates may influence the occurrence of, or the response to, MCC-related tissue injury, potentially influencing symptom severity or clustering. For this manuscript, two specific covariates of emerging emphasis in the field are highlighted: the gut microbiota and sex as a biological variable.

Figure 1.

Theoretical framework.

A New Framework for Symptom Science

Tissue damage or cell death from injury or infection are unfailingly associated with an inflammatory response, driven by the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines from white blood cells drawn to the area, that in turn initiate a sequence of responses aimed at protecting the host or healing the injury (Dantzer & Kelley, 2007; Dinarello, 1996; Steptoe et al., 2007). Evidence has accumulated, however, that inflammation also activates pathways damaging to the host, including pathways associated with the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as nitric oxide (Jones, 2006) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS), including peroxynitrite (Carta et al., 2009), and pro-inflammatory cytokine transcription factors such as NF-kappaB (Hensley et al., 2000). Activation of these pathways sets up a positive feedback cycle as these substances themselves further stimulate cell injury and death (Laroux et al., 2001), thereby perpetuating the production of additional ROS/RNS. If this cycle is not interrupted, these and other inflammatory mediators contribute to accelerated aging and chronic inflammatory disease (Go & Jones, 2017; Jones, 2006; Jones et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2014). The high burden of oxidative stress associated with chronic inflammation has been linked to all or nearly all of the 9 conditions identified as most common in the U.S. (Morris & Berk, 2015; Niemann et al., 2017; Patel et al., 2016; Yang et al., 2017), and to the development of symptoms, including fatigue, depression, and/or anxiety via both unique and overlapping processes. Each of these associations is discussed below. Given the growing recognition of the contribution of 2 covariates in particular, sex as a biological variable (Di Florio et al., 2020) and the gut microbiota (Mihai et al., 2018), on both inflammation and affective symptomatology, they are discussed in additional detail.

Symptoms

Fatigue

Oxidative stress occurs whenever the production and accumulation of ROS/RNS exceeds the ability of the cell’s anti-oxidant cell defenses (Halvey et al., 2007), such as those of the glutathione and thioredoxin systems, to clear them. If unchecked, ROS/NRS reduce the efficiency of the mitochondrial electron transport chain (Georgieva et al., 2017), decreasing mitochondrial ATP production and leading to ATP depletion, lactate accumulation (Finsterer, 2012; Georgieva et al., 2017; Jones, 2006), and a reduction in key metabolites important for energy production such as L-Carnitine (Pekala et al., 2011). Energy availability is compromised, contributing to the symptom of fatigue that often accompanies chronic inflammatory disease (Felger & Lotrich, 2013; Finsterer, 2012; Morris & Berk, 2015; Straub, 2012). Chronic inflammation (Cirinos et al., 2017) and oxidative stress (Lopresti et al., 2014; Salim, 2014) can also contribute to the symptoms of depression and anxiety in patients with chronic disease (Catena-Dell’Osso et al., 2013; Czarny et al., 2018; Raison et al., 2006; Raison & Miller, 2013).

Depression

Pro-inflammatory cytokines link to depression in several ways, both directly via effects on the central nervous system (Godbout & Glaser, 2006; Jehn et al., 2010; Miller & Raison, 2016; Miura et al., 2008), as well as indirectly, including via stimulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and elevated cortisol (Cubala & Landowski, 2014; Lamers et al., 2013). Activation of the HPA axis is also associated with a shift in the metabolism of the essential amino acid tryptophan away from the serotonin pathway and toward the kynurenine pathway, through activation of the rate-limiting enzyme indoleamine 2, 3-dioxygenase (IDO; Gabbay et al., 2012; Miura et al., 2008; Raison et al., 2010). Activation of IDO and the kynurenine pathway deprives tryptophan hydroxylase of its substrate in the serotonin pathway, contributing to decreased serotonin production and worsening depressive symptoms (Maes et al., 2011). Other metabolites affected by activation of the serotonin pathway include dopamine and neopterin (Miura et al., 2009; Raison et al., 2010). In a mouse model, metabolic pathways associated with a high fat diet and obesity have been reported to downregulate production of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF); decreased levels of BDNF in turn, are also associated with “depressive-like” behaviors in the animal model (Wu et al., 2017) as well as cognitive dysfunction. A recent review by Chaves Filho et al. (2018) support a similar association between inflammation, IDO, tryptophan, depression, and obesity in humans. Pro-inflammatory cytokines also directly reduce the production of BDNF (Zhang et al., 2016).

Anxiety

The psychological stressors associated with patient anxiety activate autonomic nervous system arousal directly and via stimulation of the HPA axis, ultimately increasing the release of circulating catecholamines (Player & Peterson, 2011). Oxidative stress and inflammation induce similar changes in noradrenergic pathways (Hurst & Collins, 1994; Salim, 2014). More recent evidence has linked the immune-kynurenine pathway to anxiety disorders, based on the hypothesis that kynurenine pathway metabolites induce serotonin deficiency, increasing susceptibility to anxiety reactions (Kim & Jeon, 2018). Repeated episodes of heightened arousal have been linked to hypertension, worsened inflammation, and coronary artery disease (Davies & Allgulander, 2013; Player & Peterson, 2011). Within this framework, we focus on fatigue, depression, and anxiety; however other symptoms that impact health related quality of life can be included in the framework as well (note arrow from metabolites and metabolic pathways to health-related quality of life).

Symptom Expression, Synergy, and Clustering in Patients With Multiple Chronic Conditions

Symptom Expression

Fatigue, depression, and anxiety are common among individuals with MCCs and contribute adversely to patient quality of life and functional ability (Barile et al., 2013; Heyworth et al., 2009; Tinetti et al., 2011; Tyack et al., 2018). Although managing patients with MCCs should include a holistic approach to all conditions, most individuals with MCCs currently receive treatment based on single disease practice guidelines rather than an approach that addresses the complexities of multiple disease overlap (Bell & Saraf, 2016). A recent Cochrane Review on the topic of the effectiveness of interventions for patients with MCCs concluded that most often interventions for improving outcomes in individuals with MCCs were focused on general suggestions for improved case management, multidisciplinary team work, and patient education materials, rather than targeted interventions based on the unique combination of chronic conditions (Smith et al., 2016). The review concluded with the observation that this generalized approach to treatment only minimally improves patient-reported outcomes (Smith et al., 2016). The absence of focus on symptom interventions in the review is concerning. Addressing the impact of symptoms associated with MCC might improve health related quality of life.

Also important in regard to MCCs is the recognition that while symptom severity typically worsens as additional chronic conditions add on, this phenomenon cannot be captured by simply summing the number of chronic diseases present or summing severity scores associated with a particular symptom. Instead, it appears that certain pairings of conditions, for example cardiac and respiratory disease, or arthritis and respiratory disease, have synergistic interactions and patients with those disease combinations often experience more severe symptoms and physical disability than would be expected from adding together their separate effects alone (Fortin et al., 2007; Rijken et al., 2005).

Symptom Synergy

Symptom synergy in patients with multiple chronic conditions was addressed in a recent study wherein the authors tracked self-reported severity of depressive symptoms, in over 5,688 individuals (Pruchno et al., 2016), as determined both by mean score on the CES-D (Radloff & Rae, 1979) and percentage of those scoring >10. Participants reported 0 (n = 1,559), 1 (n = 1,835), 2 (n = 1, 277), 3 (n = 708), 4 (n = 244), or 5 (n = 60) chronic conditions limited to include: arthritis, diabetes, heart disease, hypertension, or pulmonary disease. As expected, the mean CES-D score rose with the addition of each chronic condition, from a baseline of 4.3 (±4.4) in individuals with no chronic condition, to a mean of 12.2 (±7.2) in patients reporting 5 chronic conditions. Of particular note, when mean depressive symptoms across single diseases were compared, patients with HTN alone scored the lowest in depressive symptoms (CES-D = 4.54 ± 4.81), consistent with the reputation of HTN as “a silent killer.” However, when evaluated in combination with other diseases, unexpected symptom synergy with HTN was identified. For example, the CES-D score when adding HTN to arthritis (CES-D = 6.31 ± 5.6) was greater than when adding heart disease to arthritis (CES-D = 5.76 ± 4.53), although depressive symptoms in heart disease alone were greater than HTN alone. Similarly, adding HTN to heart disease and pulmonary disease (CES-D = 8.49 ± 7.39) increased depressive symptoms more than adding diabetes to heart disease and pulmonary disease (CES-D = 8.25 ±8.91); although again, HTN alone was associated with lower CES-D score than diabetes alone. Interestingly, in some cases, adding HTN decreased symptoms. Adding HTN to heart disease decreased the average CES-D score from 5.19 ± 4.91 in heart disease alone, to 4.78 ± 3.44 in heart disease + HTN. These data provide preliminary examples lending support to the scientific premise that individual metabolites or metabolic pathways active in patients with multiple chronic conditions may synergize, in either a positive or a negative way, to affect symptom severity.

Covariates: The Gut Microbiota and Sex as a Biological Variable

Two important covariates from the model that are of increasing interest in symptom science due to the growing recognition of their influence on affective symptomatology are sex as a biological variable and the gut microbiota. Below, we briefly discuss their relevance to the framework.

The gut microbiota

Several of the same pathways that underlie symptoms, are themselves affected by the composition and function of the gut microbiota (i.e., the bacteria of the gut as characterized by 16 S rRNA gene sequencing). All humans are a composite of the genes embedded in their human genome combined with the genes embedded in their microbial colony, and thus the metabolites and metabolic pathways present in us at any one time are a combination of human and microbial traits and production (Turnbaugh et al., 2007). Starting at birth, gut microbes produce essential nutrients, regulate immunity and inflammation, metabolize drugs and toxins, and affect a myriad of host metabolic pathways (Dinan & Cryan, 2017; Turnbaugh et al., 2007). Although influenced by diet, the gut microbiota is relatively stable from early childhood through young and middle adulthood (Jones et al., 2012; Zoetendal et al., 1998), with significant changes occurring primarily in older adults (Nagpal et al., 2018; O’Toole & Jeffery, 2018).

Dysbiosis of the gut microbiota, defined as a pathological imbalance in microbial species compared to the HMP library of healthy adults (Turnbaugh et al., 2007), is associated with a variety of adverse health conditions. An increase in the abundance of specific species of gut bacteria, including Enterobacteriaceae and Streptococcus, has been linked to chronic conditions, including obesity, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, cirrhosis, and rheumatoid arthritis (Aron-Wisnewsky & Clement, 2016; Jie et al., 2017; Wang & Jia, 2016). In 2017, Li and colleagues reported decreased gut microbial diversity, a Prevotella-dominated gut enterotype, and overgrowth of bacteria including Prevotella and Klebesiella in both pre-hypertensive and hypertensive populations. Moreover, hypertensive disorder is associated with the increased passage of gut microbes out of the gut, resulting in a systemic pro-inflammatory response and increased symptom burden (Taylor & Takemiya, 2017).

Interestingly, the gut microbiota is directly linked to the production of the metabolites identified previously as being significant contributors to the symptoms of depression, fatigue, and anxiety (Buigues et al., 2016; Clapp et al., 2017; Dinan & Cryan, 2012, 2017; Grenham et al., 2011; Lawrence & Hyde, 2017; Mayer, 2011; Mayer et al., 2014; O’Mahony et al., 2015) including: pro-inflammatory cytokines, cortisol hormone, and the molecules of the tryptophan-serotonin-related enzyme pathways, indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) and tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase (TDO; O’Mahony et al., 2015). Specifically: 1) Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines. For most persons, small amounts of gut bacteria leak across the luminal intestinal layer of the gut each day, entering the peritoneal space outside the gut. While, this small amount of leakage is usually minimally associated with an inflammatory response, under some circumstances a significant pro-inflammatory response may be initiated, for example, in those who experience excessive gut leakiness or those who have a more pathogenic gut microbiota. For example, among individuals with a gut microbiota that includes a high proportion of gram-negative bacteria, characterized by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) on the outer cell membrane, there may be an elevated risk of developing a significant pro-inflammatory response to the bacteria that cross the gut wall, potentially placing them at risk of adverse mood and neuroplasticity (Dantzer & Kelley, 2007), as described previously. Although the direct influence of systemic inflammation following exposure of gut bacteria on mood in humans is unclear, in mice, certain highly pathologic bacteria such as Campylobacter jejuni, have been linked to anxiety even at very low doses (Lyte et al., 1998). 2) The HPA Axis. Cortisol hormone, released in response to stress, appears to loosen the tight junctions of the gut, increasing gut permeability to gram-negative and other pathogenic bacteria (Dinan & Cryan, 2017). Persons with MCCs who report higher than normal stress, therefore, may be most at risk of systemic exposure to excessive or inflammatory gut bacteria with further negative impact on their mood, although this has not been demonstrated to date. Gut-related activation of the inflammatory response also influences the HPA axis via cytokine-driven cortisol stimulation (Bailey et al., 2011). 3) The Neural Pathway. The vagus nerve, the parasympathetic arm of the autonomic nervous system, innervates and regulates the gut, promotes anti-inflammatory activity, and influences the Central Nervous System and behavior directly and via interaction with the HPA axis and anti-inflammatory processes (Corwin, 2000a). Afferent vagal firing is highly sensitive to the microbial milieu surrounding the gut (O’Mahony et al., 2015), providing a third key mechanism by which the gut-brain axis is regulated. 4) The Tryptophan-Serotonin Related IDO and TDP Enzyme Pathways. Over 90% of the serotonin in the body is contained in the gut, produced by gut microbial metabolism of the essential amino acid tryptophan to serotonin (Kennedy et al., 2017). Serotonin has direct effects on the enteric nervous system and, once out of the gut, stimulates vagal afferents that carry signals to the brain. Systemic serotonin is also thought to cross the blood brain barrier, affecting the symptom of depression at the level of the hypothalamus. Depressive symptoms have been linked to reduced availability of tryptophan required for normal serotonin synthesis (O’Mahony et al., 2015).

To date, the contribution of the gut microbiota to symptom development, severity, or clustering has not been investigated in patients with multiple chronic conditions. We include it in our model to reflect the growing recognition of its importance to host homeostasis.

Sex as a Biological Variable

Consideration of an individual’s biological sex as a covariate to symptom development, clustering, or synergy in patients with multiple chronic conditions is increasingly recommended for several reasons. First, there is a growing recognition that women are more likely to experience chronic conditions than men (Branyan & Sohrabji, 2020), making the relevance of the question of high importance. Women also are more prone to depressive symptoms than men (Slavich & Sacher, 2019) across multiple stages of the life course (Altemus et al., 2014; Mattina et al., 2019) and demonstrate differences in their metabolic profiles compared to males, including metabolites and metabolic pathways related to steroid metabolism, oxidative phosphorylation, and energy storage (Krumsiek et al., 2015; Patel et al., 2013). Previous research on differences in symptom severity, clustering, or synergy based on sex has been minimal and has not considered the impact of biological sex on the activation or suppression of potentially significant metabolites or metabolic pathways.

Conclusions and Implications for Nursing

The symptoms of fatigue, depression and anxiety are often present in patients with a single chronic condition, with symptom severity usually worsening in those with multiple chronic conditions. Individually, these symptoms have established links to inflammation and oxidative stress, and to the composition of the gut microbiome, with each influenced by sex as a biological variable. It is important, however, that researchers and clinicians become better aware of the potential synergy of metabolites and metabolic pathways activated in persons with MCCs in order to better holistically assess and intervene. It is also important for both researchers and clinicians to recognize how the metabolites or metabolic pathways associated with symptoms may synergize or cluster in those with multiple chronic conditions as well as to consider each patient’s risk for symptoms or symptom clusters in light of personal variables such as biological sex, chronic stress, or the gut microbiome. The model presented provides a framework within which to examine symptoms and their synergies within the context of multiple chronic conditions. With the growing recognition of the complexity and impact of multiple chronic conditions in the U.S., it is imperative that as nurse scientists, we expose these complex interactions and as clinicians, we translate a better mechanistic understanding of symptom development, severity, and clustering into providing the right intervention to the right patient the first time, thus improving health related quality of life.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the NIH/National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR): [P30NR018090]: Center for the Study of Symptom Science, Metabolomics and Multiple Chronic Conditions. Corwin (PI) [3 R01NR0148003 R01NR014800]: Metabolomics Common Fund Supplement: Collaborative Activities to Promote Metabolomics Research. Corwin & Jones (PI).

ORCID iD: Elizabeth J. Corwin  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9348-415X

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9348-415X

References

- Altemus M., Sarvaiya N., Neill Epperson C. (2014). Sex differences in anxiety and depression clinical perspectives. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology, 35(3), 320–330. 10.1016/j.yfrne.2014.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armitage E. G., & Barbas. C. (2014). Metabolomics in cancer biomarker discovery: Current trends and future perspectives. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analyses, 87(18), 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett S. V., Clark I. A. (2012). Inflammatory fatigue and sickness behaviour—Lessons for the diagnosis and management of chronic fatigue syndrome. Journal of Affective Disorders, 141(2–3), 130–142. 10.1016/j.jad.2012.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aron-Wisnewsky J., Clement K. (2016). The gut microbiome, diet, and links to cardiometabolic and chronic disorders. Nature Reviews Nephrology, 12(3), 169–181. 10.1038/nrneph.2015.191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey M. T., Dowd S. E., Galley J. D., Hufnagle A. R., Allen R. G., Lyte M. (2011). Exposure to a social stressor alters the structure of the intestinal microbiota: implications for stressor-induced immunomodulation. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 25(3), 397–407. 10.1016/j.bbi.2010.10.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barile J. P., Thompson W. W., Zack M. M., Krahn G. L., Horner-Johnson W., Bowen S. E. (2013). Multiple chronic medical conditions and health-related quality of life in older adults, 2004-2006. Preventing Chronic Disease, 10, E162. 10.5888/pcd10.120282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beger R. D., Dunn W., Schmidt M. A., Gross S. S., Kirwan J. A., Cascante M., Brennan L., Wishart D. S., Oresic M., Hankemeier T., Broadhurst D. I., Lane A. N., Suhre K., Kastenmuller G., Sumner S. J., Thiele I., Fiehn O., Kaddurah-Daouk R. for “Precision, M., & Pharmacometabolomics Task Group”-Metabolomics Society, I. (2016). Metabolomics enables precision medicine: “A White Paper, Community Perspective.” Metabolomics, 12(10), 149. 10.1007/s11306-016-1094-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell S. P., Saraf A. A. (2016). Epidemiology of multimorbidity in older adults with cardiovascular disease. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine, 32(2), 215–226. 10.1016/j.cger.2016.01.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branyan T. E., Sohrabji F. (2020). Sex differences in stroke co-morbidities. Experimental Neurology, 332, 113384. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2020.113384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buigues C., Fernandez-Garrido J., Pruimboom L., Hoogland A. J., Navarro-Martinez R., Martinez-Martinez M., Verdejo Y., Mascaros M. C., Peris C., Cauli O. (2016). Effect of a prebiotic formulation on frailty syndrome: A randomized, double-blind clinical trial. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 17(6), 932. 10.3390/ijms17060932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buttorff C., Ruder T., Bauman M. (2017). Multiple chronic conditions in the United States. RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org//pubs/tools/TL221.html [Google Scholar]

- Carta S., Castellani P., Delfino L., Tassi S., Vene R., Rubartelli A. (2009). DAMPs and inflammatory processes: The role of redox in the different outcomes. Journal of Leukocyte Biology, 86(3), 549–555. 10.1189/jlb.1008598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catena-Dell’Osso M., Rotella F., Dell’Osso A., Fagiolini A., Marazziti D. (2013). Inflammation, serotonin and major depression. Current Drug Targets, 14(5), 571–577. <Go to ISI>://WOS:000317909000006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catlin B., Jovaag A., Wan Dijik W. (2015). 2015 County health rankings key findings report. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Chaves Filho A. J. M., Lima C. N. C., Vasconcelos S. M. M., de Lucena D. F., Maes M., Macedo D. (2018). IDO chronic immune activation and tryptophan metabolic pathway: A potential pathophysiological link between depression and obesity. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry, 80 t C(P), 234–249. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2017.04.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chirinos D. A., Murdock K. W., LeRoy A. S., Fagundes C. (2017). Depressive symptom profiles, cardio-metabolic risk and inflammation: Results from the MIDUS study. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 82, 17–25. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2017.04.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapp M., Aurora N., Herrera L., Bhatia M., Wilen E., Wakefield S. (2017). Gut microbiota’s effect on mental health: The gut-brain axis. Clinical Practice, 7(4), 987. 10.4081/cp.2017.987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corwin E. J. (2000. a). Understanding cytokines. Part I: Physiology and mechanism of action. Biological Research for Nursing, 2(1), 30–40. 10.1177/109980040000200104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corwin E. J. (2000. b). Understanding cytokines. Part II: Implications for nursing research and practice. Biological Research for Nursing, 2(1), 41–48. 10.1177/109980040000200105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cubala W. J., Landowski J. (2014). C-reactive protein and cortisol in drug-naive patients with short-illness-duration first episode major depressive disorder: Possible role of cortisol immunomodulatory action at early stage of the disease. Journal of Affective Disorders, 152–154, 534–537. 10.1016/j.jad.2013.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czarny P., Wigner P., Galecki P., Sliwinski T. (2018). The interplay between inflammation, oxidative stress, DNA damage, DNA repair and mitochondrial dysfunction in depression. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry, 80(Pt C), 309–321. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2017.06.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantzer R. (2001). Cytokine-induced sickness behavior: Mechanisms and implications. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 933, 222–234. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12000023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantzer R., Kelley K. W. (2007). Twenty years of research on cytokine-induced sickness behavior [Historical Article Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural]. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 21(2), 153–160. 10.1016/j.bbi.2006.09.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies S. J., Allgulander C. (2013). Anxiety and cardiovascular disease. Modern Trends in Pharmacopsychiatry, 29, 85–97. 10.1159/000351945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Florio D. N., Sin J., Coronado M. J., Atwal P. S., Fairweather D. (2020). Sex differences in inflammation, redox biology, mitochondria and autoimmunity. Redox Biology, 31, 101482. 10.1016/j.redox.2020.101482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinan T. G., Cryan J. F. (2012). Regulation of the stress response by the gut microbiota: Implications for psychoneuroendocrinology. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 37(9), 1369–1378. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinan T. G., Cryan J. F. (2017). Gut-brain axis in 2016: Brain-gut-microbiota axis—Mood, metabolism and behaviour. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 14(2), 69–70. 10.1038/nrgastro.2016.200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinarello C. A. (1996). Biologic basis for interleukin-1 in disease. Blood, 87(6), 2095–2147. 10.1182/blood.V87.6.2095.bloodjournal8762095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felger J. C., Lotrich F. E. (2013). Inflammatory cytokines in depression: Neurobiological mechanisms and therapeutic implications [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Review]. Neuroscience, 246, 199–229. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.04.060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finsterer J. (2012). Biomarkers of peripheral muscle fatigue during exercise. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 13, 218. 10.1186/1471-2474-13-218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortin M., Dubois M. F., Hudon C., Soubhi H., Almirall J. (2007). Multimorbidity and quality of life: A closer look. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 5, 52. 10.1186/1477-7525-5-52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freid V. M., Bernstein A. B., Bush M. (2012). Multiple chronic conditions among adults aged 45 and over: Trends over the past 10 years. NCHS Data Brief, 100, 1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabbay V., Ely B. A., Babb J., Liebes L. (2012). The possible role of the kynurenine pathway in anhedonia in adolescents. Journal of Neural Transmission, 119(2), 253–260. 10.1007/s00702-011-0685-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgieva E., Ivanova D., Zhelev Z., Bakalova R., Gulubova M., Aoki I. (2017). Mitochondrial dysfunction and redox imbalance as a diagnostic marker of “Free Radical Diseases”. Anticancer Research, 37(10), 5373–5381. 10.21873/anticanres.11963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Go Y. M., Jones D. P. (2017). Redox theory of aging: Implications for health and disease. Clinical Science (London), 131(14), 1669–1688. 10.1042/CS20160897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godbout J. P., Glaser R. (2006). Stress-induced immune dysregulation: implications for wound healing, infectious disease and cancer [Review]. Journal of Neuroimmune Pharmacology, 1(4), 421–427. 10.1007/s11481-006-9036-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grenham S., Clarke G., Cryan J. F., Dinan T. G. (2011). Brain-gut-microbe communication in health and disease. Frontiers in Physiology, 2, 94. 10.3389/fphys.2011.00094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halvey P. J., Hansen J. M., Johnson J. M., Go Y. M., Samali A., Jones D. P. (2007). Selective oxidative stress in cell nuclei by nuclear-targeted D-amino acid oxidase. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling, 9(7), 807–816. 10.1089/ars.2007.1526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes S. L., Salzberg C. A., McCarthy D., Radley D. C., Abrams M. K., Shah T., Anderson G. F. (2016). High-need, high-cost patients: Who are they and how do they use health care? A population-based comparison of demographics, health care use, and expenditures. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund), 26, 1–14. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27571599 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hensley K., Robinson K. A., Gabbita S. P., Salsman S., Floyd R. A. (2000). Reactive oxygen species, cell signaling, and cell injury. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 28(10), 1456–1462. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10927169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyworth I. T. M., Hazell M. L., Linehan M. F., Frank T. L. (2009). How do common chronic conditions affect health-related quality of life? British Journal of General Practice, 59(568), 833–838. 10.3399/bjgp09X453990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes N., Berube A. (2016). City and metropolitan inequality on the rise, driven by declining incomes. Brookings Report. https://www.brookings.edu/research/city-and-metropolitan-income-inequality-data-reveal-ups-and-downs-through-2016/

- Horgan R. P., Clancy O. H., Myers J. E., Baker P. N. (2009). An overview of proteomic and metabolomic technologies and their application to pregnancy research. Bjog-An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 116(2), 173–181. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.01997.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurst S. M., Collins S. M. (1994). Mechanism underlying tumor necrosis factor-alpha suppression of norepinephrine release from rat myenteric plexus. American Journal of Physiology, 266(6 Pt 1), G1123–1129. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8023943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jehn C. F., Kuhnhardt D., Bartholomae A., Pfeiffer S., Schmid P., Possinger K., Flath B. C., Luftner D. (2010). Association of IL-6, hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis function, and depression in patients with cancer. Integrative Cancer Therapies, 9(3), 270–275. 10.1177/1534735410370036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y., Zhu Z., Shi J., An Y., Zhang K., Wang Y., Li S., Jin L., Ye W., Cui M., Chen X. (2019). Metabolomics in the development and progression of dementia: A systematic review. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 13, 343. 10.3389/fnins.2019.00343.eCollection2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jie Z., Xia H., Zhong S. L., Feng Q., Li S., Liang S., Zhong H., Liu Z., Gao Y., Zhao H., Zhang D., Su Z., Fang Z., Lan Z., Li J., Xiao L., Li J., Li R., Li X., Kristiansen K. (2017). The gut microbiome in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Nature Communications, 8(1), 845. 10.1038/s41467-017-00900-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones D. P. (2006). Redefining oxidative stress. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling, 8(9–10), 1865–1879. 10.1089/ars.2006.8.1865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones D. P., Park Y., Ziegler T. R. (2012). Nutritional metabolomics: Progress in addressing complexity in diet and health. Annual Review of Nutrition, 32, 183–202. 10.1146/annurev-nutr-072610-145159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones D. P., True H. D., Patel J. (2017). Leukocyte trafficking in cardiovascular disease: Insights from experimental models. Mediators of Inflammation, 2017. 10.1155/2017/9746169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy P. J., Cryan J. F., Dinan T. G., Clarke G. (2017). Kynurenine pathway metabolism and the microbiota-gut-brain axis. Neuropharmacology, 112(Pt B), 399–412. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2016.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khansari N., Shakiba Y., Mahmoudi M. (2009). Chronic inflammation and oxidative stress as a major cause of age-related diseases and cancer. Recent Patents on Inflammation & Allergy Drug Discovery, 3(1), 73–80. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19149749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y. K., Jeon S. W. (2018). Neuroinflammation and the immune-kynurenine pathway in anxiety disorders. Current Neuropharmacology, 16(5), 574–582. 10.2174/1570159X15666170913110426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krumsiek J., Mittelstrass K., Do K. T., Stuckler F., Ried J., Adamski J., Peters A., Illig T., Kronenberg F., Friedrich N., Nauck M., Pietzner M., Mook-Kanamori D. O., Suhre K., Gieger C., Grallert H., Theis F. J., Kastenmuller G. (2015). Gender-specific pathway differences in the human serum metabolome. Metabolomics, 11(6), 1815–1833. 10.1007/s11306-015-0829-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamers F., Vogelzangs N., Merikangas K. R., de Jonge P., Beekman A. T., Penninx B. W. (2013). Evidence for a differential role of HPA-axis function, inflammation and metabolic syndrome in melancholic versus atypical depression. Molecular Psychiatry, 18(6), 692–699. 10.1038/mp.2012.144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laroux F. S., Pavlick K. P., Hines I. N., Kawachi S., Harada H., Bharwani S., Hoffman J. M., Grisham M. B. (2001). Role of nitric oxide in inflammation. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica, 173(1), 113–118. 10.1046/j.1365-201X.2001.00891.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence K., Hyde J. (2017). Microbiome restoration diet improves digestion, cognition and physical and emotional wellbeing. PLoS One, 12(6), e0179017. 10.1371/journal.pone.0179017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Lopresti A. L., Maker G. L., Hood S. D., Drummond P. D. (2014). A review of peripheral biomarkers in major depression: The potential of inflammatory and oxidative stress biomarkers. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry, 48, 102–111. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2013.09.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyte M., Varcoe J. J., Bailey M. T. (1998). Anxiogenic effect of subclinical bacterial infection in mice in the absence of overt immune activation. Physiology & Behavior, 65(1), 63–68. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9811366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maes M., Leonard B. E., Myint A. M., Kubera M., Verkerk R. (2011). The new ‘5-HT’ hypothesis of depression: Cell-mediated immune activation induces indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase, which leads to lower plasma tryptophan and an increased synthesis of detrimental tryptophan catabolites (TRYCATs), both of which contribute to the onset of depression. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry, 35(3), 702–721. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.12.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Subero M., Anderson G., Kanchanatawan B., Berk M., Maes M. (2016). Comorbidity between depression and inflammatory bowel disease explained by immune-inflammatory, oxidative, and nitrosative stress; tryptophan catabolite; and gut-brain pathways. CNS Spectrums, 21(2), 184–198. 10.1017/S1092852915000449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattina G. F., Van Lieshout R. J., Steiner M. (2019). Inflammation, depression and cardiovascular disease in women: The role of the immune system across critical reproductive events. Therapeutic Advances in Cardiovascular Disease, 13. 10.1177/1753944719851950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer E. A. (2011). Gut feelings: The emerging biology of gut-brain communication. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 12(8), 453–466. 10.1038/nrn3071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer E. A., Knight R., Mazmanian S. K., Cryan J. F., Tillisch K. (2014). Gut microbes and the brain: Paradigm shift in neuroscience. The Journal of Neuroscience, 34(46), 15490–15496. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3299-14.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCusker R. H., Kelley K. W. (2013). Immune-neural connections: how the immune system’s response to infectious agents influences behavior. The Journal of Experimental Biology, 216(Pt 1), 84–98. 10.1242/jeb.073411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPhail S. M. (2016). Multimorbidity in chronic disease: Impact on health care resources and costs. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy, 9, 143–156. 10.2147/Rmhp.S97248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihai S., Codrici E., Popescu I. D., Enciu A. M., Albulescu L., Necula L. G., Mambet C., Anton G., Tanase C. (2018). Inflammation-related mechanisms in chronic kidney disease prediction, progression, and outcome. Journal of Immunology Research, 2018, 2180373. 10.1155/2018/2180373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller A. H., Raison C. L. (2016). The role of inflammation in depression: From evolutionary imperative to modern treatment target. Nature Reviews Immunology, 16(1), 22–34. 10.1038/nri.2015.5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura H., Ozaki N., Sawada M., Isobe K., Ohta T., Nagatsu T. (2008). A link between stress and depression: Shifts in the balance between the kynurenine and serotonin pathways of tryptophan metabolism and the etiology and pathophysiology of depression. Stress, 11(3), 198–209. 10.1080/10253890701754068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura H., Shirokawa T., Isobe K., Ozaki N. (2009). Shifting the balance of brain tryptophan metabolism elicited by isolation housing and systemic administration of lipopolysaccharide in mice. Stress, 12(3), 206–214. 10.1080/10253890802252442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris G., Berk M. (2015). The many roads to mitochondrial dysfunction in neuroimmune and neuropsychiatric disorders. BMC Medicine, 13, 68. 10.1186/s12916-015-0310-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagpal R., Mainali R., Ahmadi S., Wang S., Singh R., Kavanagh K., Kitzman D. W., Kushugulova A., Marotta F., Yadav H. (2018). Gut microbiome and aging: Physiological and mechanistic insights. Nutrition and Healthy Aging, 4(4), 267–285. 10.3233/NHA-170030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niemann B., Rohrbach S., Miller M. R., Newby D. E., Fuster V., Kovacic J. C. (2017). Oxidative stress and cardiovascular risk: Obesity, diabetes, smoking, and pollution: Part 3 of a 3-part series. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 70(2), 230–251. 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.05.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Mahony S. M., Clarke G., Borre Y. E., Dinan T. G., Cryan J. F. (2015). Serotonin, tryptophan metabolism and the brain-gut-microbiome axis. Behavioural Brain Research, 277, 32–48. 10.1016/j.bbr.2014.07.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Toole P. W., Jeffery I. B. (2018). Microbiome-health interactions in older people. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, 75(1), 119–128. 10.1007/s00018-017-2673-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozdemir B. C., Dotto G. P. (2017). Racial differences in cancer susceptibility and survival: More than the color of the skin? Trends Cancer, 3(3), 181–197. 10.1016/j.trecan.2017.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel M. J., Batch B. C., Svetkey L. P., Bain J. R., Turer C. B., Haynes C., Muehlbauer M. J., Stevens R. D., Newgard C. B., Shah S. H. (2013). Race and sex differences in small-molecule metabolites and metabolic hormones in overweight and obese adults. OMICS, 17(12), 627–635. 10.1089/omi.2013.0031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel R. S., Ghasemzadeh N., Eapen D. J., Sher S., Arshad S., Ko Y. A., Veledar E., Samady H., Zafari A. M., Sperling L., Vaccarino V., Jones D. P., Quyyumi A. A. (2016). Response to letter regarding article “Novel Biomarker of Oxidative Stress is Associated with Risk of Death in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease”. Circulation, 133(22), e667. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.022753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson W. S., Bhat-Schelbert K., Probst J. C. (2012). Multiple chronic conditions and the aging of America: Challenge for primary care physicians. Journal of Primary Care & Community Health, 3(1), 51–56. 10.1177/2150131911414577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pekala J., Patkowska-Sokola B., Bodkowski R., Jamroz D., Nowakowski P., Lochynski S., Librowski T. (2011). L-Carnitine—Metabolic functions and meaning in humans life. Current Drug Metabolism, 12(7), 667–678. <Go to ISI>://WOS:000295405400009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Player M. S., Peterson L. E. (2011). Anxiety disorders, hypertension, and cardiovascular risk: A review. The International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine, 41(4), 365–377. 10.2190/PM.41.4.f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poon D. C. H., Ho Y. S., Chiu K., Wong H. L., Chang R. C. C. (2015). Sickness: From the focus on cytokines, prostaglandins, and complement factors to the perspectives of neurons. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 57, 30–45. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruchno R. A., Wilson-Genderson M., Heid A. R. (2016). Multiple chronic condition combinations and depression in community-dwelling older adults. The Journals of Gerontology Series A Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 71(7), 910–915. 10.1093/gerona/glw025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff L. S., Rae D. S. (1979). Susceptibility and precipitating factors in depression: Sex differences and similarities. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 88(2), 174–181. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/447900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raison C. L., Capuron L., Miller A. H. (2006). Cytokines sing the blues: Inflammation and the pathogenesis of depression [Review]. Trends in Immunology, 27(1), 24–31. 10.1016/j.it.2005.11.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raison C. L., Dantzer R., Kelley K. W., Lawson M. A., Woolwine B. J., Vogt G., Spivey J. R., Saito K., Miller A. H. (2010). CSF concentrations of brain tryptophan and kynurenines during immune stimulation with IFN-alpha: relationship to CNS immune responses and depression. Molecular Psychiatry, 15(4), 393–403. 10.1038/mp.2009.116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raison C. L., Miller A. H. (2013). Do cytokines really sing the blues? Cerebrum, 2013, 10. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24116267 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rijken M., van Kerkhof M., Dekker J., Schellevis F. G. (2005). Comorbidity of chronic diseases: Effects of disease pairs on physical and mental functioning.Quality of Life Research, 14(1), 45–55. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15789940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocca W. A., Boyd C. M., Grossardt B. R., Bobo W. V., Finney Rutten L. J., Roger V. L., Ebbert J. O., Therneau T. M., Yawn B. P., St Sauver J. L. (2014). Prevalence of multimorbidity in a geographically defined American population: patterns by age, sex, and race/ethnicity. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 89(10), 1336–1349. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2014.07.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salim S. (2014). Oxidative stress and psychological disorders. Current Neuropharmacology, 12(2), 140–147. 10.2174/1570159x11666131120230309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salzberg C. A., Hayes S. L., McCarthy D., Radley D. C., Abrams M. K., Shah T., Anderson G. F. (2016). Health system performance for the high-need patient: A look at access to care and patient care experiences. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund), 27, 1–12. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27571600 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slavich G. M., Sacher J. (2019). Stress, sex hormones, inflammation, and major depressive disorder: Extending Social Signal Transduction Theory of Depression to account for sex differences in mood disorders. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 236(10), 3063–3079. 10.1007/s00213-019-05326-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S. M., Wallace E., O’Dowd T., Fortin M. (2016). Interventions for improving outcomes in patients with multimorbidity in primary care and community settings. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 3, CD006560. 10.1002/14651858.CD006560.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steptoe A., Hamer M., Chida Y. (2007). The Effects of acute psychological stress on circulating inflammatory factors in humans: a review and meta-analysis. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 21(7), 901–912. 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straub R. H. (2012). Evolutionary medicine and chronic inflammatory state-known and new concepts in pathophysiology. Journal of Molecular Medicine-Jmm, 90(5), 523–534. 10.1007/s00109-012-0861-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straub R. H. (2017). The Brain and immune system prompt energy shortage in chronic inflammation and ageing. Nature Reviews Rheumatology, 13(12), 743–751. 10.1038/nrrheum.2017.172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor W. R., Takemiya K. (2017). Hypertension opens the flood gates to the gut microbiota. Circulation Research, 120(2), 249–251. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.310339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinetti M. E., McAvay G. J., Chang S. S., Newman A. B., Fitzpatrick A. L., Fried T. R., Peduzzi P. N. (2011). Contribution of multiple chronic conditions to universal health outcomes. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 59(9), 1686–1691. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03573.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tisminetzky M., Bayliss E. A., Magaziner J. S., Allore H. G., Anzuoni K., Boyd C. M., Gill T. M., Go A. S., Greenspan S. L., Hanson L. R., Hornbrook M. C., Kitzman D. W., Larson E. B., Naylor M. D., Shirley B. E., Tai-Seale M., Teri L., Tinetti M. E., Whitson H. E., Gurwitz J. H. (2017). Research Priorities to Advance the Health and Health Care of Older Adults with Multiple Chronic Conditions. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 65(7), 1549–1553. 10.1111/jgs.14943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbaugh P. J., Ley R. E., Hamady M., Fraser-Liggett C. M., Knight R., Gordon J. I. (2007). The Human microbiome project. Nature, 449(7164), 804–810. 10.1038/nature06244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyack Z., Kuys S., Cornwell P., Frakes K. A., McPhail S. (2018). Health-related quality of life of people with multimorbidity at a community-based, interprofessional student-assisted clinic: Implications for assessment and intervention. Chronic Illness, 14(3), 169–181. 10.1177/1742395317724849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2015). Race and ethnicity in Georgia. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/GA?

- Wang J., Jia H. (2016). Metagenome-wide association studies: fine-mining the microbiome. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 14(8), 508–522. 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P., Guan P. P., Wang T., Yu X., Guo J. J., Wang Z. Y. (2014). Aggravation of Alzheimer’s disease due to the COX-2-mediated reciprocal regulation of IL-1 beta and A beta between glial and neuron cells. Aging Cell, 13(4), 605–615. 10.1111/acel.12209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Wu H., Liu Q., Kalavagunta P. K., Huang Q., Lv W., An X., Chen H., Wang T., Heriniaina R. M., Qiao T., Shang J. (2017). Normal diet Vs High fat diet—A comparative study: Behavioral and neuroimmunological changes in adolescent male mice. Metab Brain Dis. 3(1), 177–190. 10.1007/s11011-017-0140-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L., Wang Y., Cai H., Wang S., Shen Y., Ke C. (2020). Application of metabolomics in the diagnosis of breast cancer: a systemcatic review. Journal of Cancer, 11(9), 2540–2551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X., Li Y., Li Y., Ren X., Zhang X., Hu D., Gao Y., Xing Y., Shang H. (2017). Oxidative Stress-Mediated Atherosclerosis: Mechanisms and Therapies. Front Physiol, 8, 600. 10.3389/fphys.2017.00600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J. C., Yao W., Hashimoto K. (2016). Brain-derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF)-TrkB Signaling in Inflammation-related Depression and Potential Therapeutic Targets. Current Neuropharmacology, 14(7), 721–731. 10.2174/1570159x14666160119094646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoetendal E. G., Akkermans A. D., De Vos W. M. (1998). Temperature gradient gel electrophoresis analysis of 16 S rRNA from human fecal samples reveals stable and host-specific communities of active bacteria. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 64(10), 3854–3859. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9758810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]