Abstract

Background

We investigated the impact of collagen usage in colo-colonic anastomoses on intra-abdominal adhesion and anastomosis safety.

Material/Methods

A total of 30 adult albino Wistar rats (aged 6–8 months) weighing 180–230 g in the laboratory setting were used in this study. Rats were divided into the 3 groups, consisting of 10 rats in each group: treated with gentamicin-impregnated collagen, treated with only collagen, and the control group. After 7 days, rats were sacrificed to evaluate adhesion scores and anastomosis bursting pressures. The Evans scoring system was used to rate adhesion levels. Bursting pressures were measured using a handheld tension device, and the scores obtained at the moment of tissue dissection were determined as the bursting pressure.

Results

The mean adhesion scores were 2.86±0.37 in the control group, 1.80±0.91 in the collagen group, and 1.78±0.83 in the gentamicin-impregnated collagen group, with the control group showing significantly higher scores than the other groups (p=0.010 and p=0.011, respectively). The mean bursting pressure levels were 174.29±44.68 mmHg in the control group, 223±38.6 mmHg in collagen group, and 223.33±42 mmHg in the gentamicin-impregnated collagen group, showing that the mean bursting pressure levels were significantly lower in the control group than the other groups (p=0.027 and p=0.029, respectively).

Conclusions

This study suggests that colo-colonic anastomosis coverage using materials incorporating collagen alone or gentamicin-impregnated collagen increases the safety of anastomosis and reduces intra-abdominal adhesions.

Keywords: Anastomosis, Surgical; Collagen; Gentamicins; Tissue Adhesions

Background

Anastomotic leaks are dreadful complications due to their association with high mortality and morbidity rates. Anastomoses are a quite frequently used procedure in general surgery, and the most common causes for anastomotic leaks include tension in the anastomosis site, deteriorated blood flow to the anastomosis, and poor surgical technique. Currently, colo-colonic anastomoses are performed by hand or via gastrointestinal staplers worldwide, and breach of anastomotic integrity due to poor surgical technique or low endurance of the anastomosis due to tissue condition are still the most common reasons for anastomotic leaks. The rate of colo-colonic anastomotic leaks ranges between 3% and 5% following elective surgeries, although it can increase up to 10–15% after emergency surgeries [1]. Intra-abdominal adhesions are one of the most common complications of abdominal surgery. As is well known in pathophysiology, wound healing consists of 3 stages. Inflammation goes on for the first 2 days, matrix synthesis happens between days 2 and 14, and after day 14 remodeling starts and may continue until month 6. Intra-abdominal adhesions occur in the matrix synthesis phase. Adhesions peak in days 7 to 10, and with the remodeling phase they start to reduce in volume and those which endure harden with fibrins [1–3].

Recent studies have demonstrated that intra-abdominal cleansing using antibiotic solutions and coverage of the anastomotic line using patches or fibrin adhesives may have effects on anastomosis endurance and intra-abdominal adhesions; they commonly point toward mechanical reinforcement in strengthening. Adhesions are another issue; some studies show that gentamicin shows improvement in reduction while others reflect a more mechanical sense, showing that covering of the healing tissue can be the primary cause of reduced adhesions [1–5].

To prevent colonic anastomotic leaks, several substances, such as sheep bowel, cartilage plaques, goose trachea, and raw hide, have been used to support anastomosis mechanically. Furthermore, several drugs, surgical procedures, prosthesis, and adhesive substances have been tried [2,3].

Gentamicin is a frequently used antibiotic agent in surgical procedures. Along with its antibacterial activity, gentamicin is known to inhibit collagen catabolism by affecting the prolidase-like enzymes, which are responsible for the collagen formulation of several RNA molecules [4,6].

In this experimental study, our aim was to see if collagen or gentamicin-impregnated collagen reinforcements have any impact on bursting pressures and intra-abdominal adhesions in colo-colonic anastomoses.

Material and Methods

This study was conducted at Trakya University, Faculty of Medicine, Department of Animal Experimentation, and the study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Trakya University, Faculty of Medicine. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the World Veterinary Association Universal Declaration on Animal Welfare, No. 123 European Convention for the Protection of Vertebrate Animals used for Experimental and Other Scientific Purposes, Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, Red Data Book of European Vertebrates, and Convention on the Conservation of European Wildlife and Natural Habitats.

A total of 30 adult albino Wistar rats (aged 6–8 months) weighing 180–230 g in the laboratory setting were used in this study. All rats were divided into the following 3 groups, with 10 rats in each group: the control group (Group I), those treated with non-gentamicin-impregnated collagen (Group II), and those treated with gentamicin-impregnated collagen (Group III). The rats were grown and maintained under standard conditions.

They were fasted for 12 h before the experiment; however, they were allowed to drink water until 30 min before the experiment. No rat was given colon cleansing before the surgical procedures, and anesthesia was achieved by the intramuscular administration of 5–10 mg/kg xylazine hydrochloride (Rompun®, Bayer, Istanbul, Turkey) and 50 mg/kg ketamine hydrochloride (Ketalar®, Pfizer, Istanbul, Turkey).

A midline incision was made in the intra-abdominal line of each rat using a No. 15 scalpel. For each rat, a 1-cm proximal colon resection was made 2 cm distal from the cecum. Monolayer anastomosis was made using 5/0 polypropylene suture, and 10 rats were given anosthomoses but were treated with neither virgin nor gentamicin-impregnated collagen, and the fascia and skin were closed using 3/0 polypropylene suture by continuous suturing (Group I: received only resection and anastomoses).

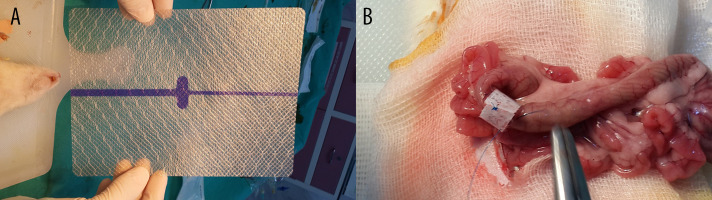

Another 10 rats underwent anastomosis as described above (Group II: treated with non-gentamicin-impregnated collagen). The ends of polypropylene sutures were left 5 cm longer for the sutures in the midline of the antimesenteric side, each of the lateral sides, and the sutures on both mesenteric sides. A width of 2 cm collagen material without gentamicin was applied onto the anastomosis (KolSpon®, Denizhan, Istanbul, Turkey) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

(A) Collagen material without gentamicin; (B) Anostomosis treated with gentamicin-impregnated collagen.

The remaining 10 rats underwent anastomosis as described above (Group III: treated with gentamicin-impregnated collagen). The ends of polypropylene sutures were left 5 cm longer for the sutures in the midline of the antimesenteric side, each of the lateral sides, and the sutures on both mesenteric sides. A width of 2 cm gentamicin-impregnated collagen was applied onto the anastomosis (JASON®G, AKM Sağlık Ürünleri, Ankara, Turkey).

After the postoperative follow-up at 12 h, the rats were provided a normal diet without any water restriction. All rats were sacrificed by exsanguination after administering a standard dose of ketamine and xylazine on day 7 postoperatively. After confirming the death of the rat, a wide incision was made on the anterior abdominal wall to visualize the entire peritoneal cavity, and adhesion scores were rated using the Evans model [6] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Evans adhesion score.

| Stage | Evans adhesion score |

|---|---|

| 0 | No adhesions |

| 1 | Self-departing adhesion |

| 2 | Pulling required adhesion |

| 3 | Dissection required adhesion |

For measuring the anastomotic bursting pressure, 2 cm of the segments from the proximal anastomosis and distal anastomosis were resected in the control group. The resected margins were placed 2 cm distal from the patch margin in the study group. All the distal ends of the resected bowel segments were tightly ligated using 2/0 silk suture. An 18F polyethylene catheter was placed into the lumen from the proximal end, and the other end of the catheter was ligated to the transducer and air pump. Therefore, the required setting was provided to measure the intra-abdominal pressure in millimeters of mercury (mmHg). The bowel segment was placed into a cape that was filled with water, and air was then provided into the lumen in a controlled manner. The first bursting in the anastomotic line was recorded as the anastomotic bursting pressure.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS for Windows version 20.0 statistical software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics were expressed as mean±standard deviation or number (%). The Mann-Whitney U test was used to analyze significant differences between the control group and the experimental group in terms of the bursting pressures. Categorical data were compared using the chi-square test. P value <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Postoperative mortality was observed in 3 rats in the control group and in 1 rat in the study group receiving non-gentamicin-impregnated collagen. However, there was no mortality in the study group receiving gentamicin-impregnated collagen. Those rats that did not survive until the designated sacrifice point at day 7 were not included in statistical analysis.

Evaluation of Intra-Abdominal Adhesions

According to the Evans model, the adhesion scores were determined based on the highest score observed in the abdomen, and the abdominal adhesion scores were estimated as follows: 85.7% (n=6) of rats in the control group were “dissection required adhesion” (Stage 3) and 14.3% (n=1) of rats were “pulling required adhesion” (Stage 2). In the non-gentamicin-impregnated collagen group, the results were 20% (n=2) of rats “dissection required adhesion” (Stage 3), 50% (n=5) “pulling required adhesion” (Stage 2), and 20% (n=2) “self-departing adhesion” (Stage 1). For the rats in the same group, 10% (n=1) “no adhesion” was detected (Stage zero). In the gentamicin-impregnated collagen group, the results were 22.2% (n=2) of rats “dissection required adhesion” (Stage 3), 33.3% (n=3) “pulling required adhesion” (Stage 2), and 44.4% (n=4) “self-departing adhesion” (Stage 2) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Adhesion acores via Evans classification.

| Adhesion scores via Evans classification | Control group (n=7) | Group collagen applied without gentamicin (n=10) | Group collagen applied with gentamicin (n=9) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stage 0, “No adhesions” | 0% | 10% (n=1) | 0% |

| Stage 1, “Self-departing adhesion” | 0% | 20% (n=2) | 44.4% (n=4) |

| Stage 2, “Pulling required adhesion” | 14.3% (n=1) | 50% (n=5) | 33.3% (n=3) |

| Stage 3, “Dissection required adhesion” | 85.7% (n=6) | 20% (n=2) | 22.2% (n=2) |

The mean adhesion scores were 2.86±0.37 in the control group, 1.80±0.91 in the non-gentamicin-impregnated collagen group, and 1.78±0.83 in the gentamicin-impregnated collagen group. These results indicate that the mean adhesion scores were significantly higher in the control group than in the other 2 groups (p=0.010; p=0.011, respectively) (Table 3). There were no significant differences between the collagen-applied group with and without gentamicin in terms of adhesion scores (p=0.828).

Table 3.

Adhesion scores via Evans classification – groups.

| Adhesion acores via Evans classification | Control group (n=7) | Group collagen applied without gentamicin (n=10) | Group collagen applied with gentamicin (n=9) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean±SD | 2.86±0.37 | 1.80±0.91 | 1.78±0.83 |

| Median (Min-Max) | 3 (2–3) | 2 (0–3) | 2 (1–3) |

| P | 0.010* | 0.011* |

Mann-Whitney U test,

p<0.05 statistically significant.

SD – standard deviation, Min – minimum; Max – maximum.

Bursting Pressure Levels

The mean bursting pressure levels were 174.29±44.68 mmHg in the control group (Group I), 223±38.6 mmHg in the non-gentamicin-impregnated collagen group (Group II), and 223.33±42 mmHg in the gentamicin-impregnated collagen group (Group III). These results show that the mean bursting pressure levels were significantly lower in the control group than in the other 2 groups (p=0.027 and p=0.029, respectively) (Table 4). Furthermore, no significant differences were found between the gentamicin-impregnated collagen and non-gentamicin-impregnated collagen groups in terms of the mean bursting pressure levels (p=0.967).

Table 4.

Bursting pressure levels – groups.

| Bursting pressure levels (mmHg) | Control group (n=7) | Group collagen applied without gentamicin (n=10) | Group collagen applied with gentamicin (n=9) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean±SD | 174.29±44.68 | 223±38.6 | 223.33±42 |

| Median (Min-Max) | 160 (140–260) | 225 (160–280) | 220 (160–280) |

| P | 0.027* | 0.029* |

Mann-Whitney U test,

p<0.05 statistically significant.

SD – standard deviation; Min – minimum; Max – maximum.

Discussion

To apply gentamicin locally in the anastomoses line, we decided to use commercial, ready-to-use, gentamicin-impregnated collagen. To differentiate whether the observed effects were primarily related to gentamicin or the applied collagen, a separate study group was established in which collagen was applied without gentamicin. To support the colo-colonic anastomosis in the study groups, we aimed at increasing both the stability of the anastomosis line and wound healing using the collagen material applied with and without gentamicin, due its feature of being fully absorbable and not causing intra-abdominal adhesion. Our study results also showed that, even without gentamicin, collagen alone can increase anastomotic resistance.

Aysan et al used polypropylene meshes to reinforce the anastomosis in rats [3]. Their results were fascinating; whereas in 9 of the 10 subjects, anastomosis did not even explode under 260 mmHg pressure. It is logical that this endurance came from the polypropylene mesh itself, but knowing the polypropylene’s tendency to cause enteric fistulas; it is not clear what the long-term results would be. Nevertheless, anastomotic resistance was enhanced, at least during the early period.

Yılmaz et al performed a similar study using polyethylene membranes around the colonic anosthomoses of rats in 2021. Their results showed no significant difference in anostomosis burst pressures between reinforced and untreated anosthomoses, but intra-abdominal adhesions were significantly lower in the treated group [7]. This can be caused by the lack of collagen or gentamicin in reinforcement material, and also may show that the lessening of the intra-abdominal adhesions most importantly involves providing a barrier between healing tissue and peritonium, and is not primarily dependant on the material used.

Similar to our study, Subhas et al used topical gentamicin with fibrin glue in rat anostomoses [8]. No additional anostomotic strength parameters were found. The difference from our results may be due to lack of collagen in the reinforcing material used by Subhas et al.

Vaneerdeweg et al conducted similar study with rat anostomosis, but used gentamicin containing sponges instead of gentamicin-impregnated collagen [5], finding no significant difference between the bursting pressures. These studies strongly suggest that gentamicin alone has no effect on anostomotic strength, and collagen is the primary reinforcement material in strengthening.

As the mean adhesion scores in the control group were significantly higher than those in the other 2 groups, we suggest that the adhesions around anastomoses result from the close contact that occurred between the polypropylene suture material and the peritoneum.

Another colo-colonic anosthomosis study on rats were performed by Bolzam-Nascimento et al in 2009 [9]. Rats were given left colic anostomoses; half of them were treated with omentoplasty around their anostomoses and then they were made to undergo hemorragic shock. The group with omentum-reinforced anosthomoses had significntly lower leak rates. Again, this suggests that increasing the stability of anosthomoses with mechanical means may result in safer anostomoses.

Regarding the limitations in our study, we used 2 types of collagen materials and waited for 7 days before sacrificing rats and did not compare molecular biomarkers of healing. Further studies are needed to determine the effects of other types of collagen materials on anastomoses. Longer or shorter periods between first surgery and sacrifice may provide different results regarding anastomotic resistance between study groups. In addition, molecular biomarkers of healing should be measured in subsequent studies.

Conclusions

The current experimental study found that using materials incorporating collagen alone or gentamicin-impregnated collagen for colo-colic anostomosis coverage increases the safety of anastomosis and reduces intra-abdominal adhesions.

Acknowledgements

We thank Trakya University, Medical Faculty, Biostatistics Department for their invaluable support.

Footnotes

Ethics Approval

All applicable international, national, and/or institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals were followed. All procedures performed in studies involving animals were in accordance with the ethics standards of the institution or practice at which the studies were conducted.

Conflict of Interest

None.

Declaration of Figures Authenticity

All figures submitted have been created by the authors who confirm that the images are original with no duplication and have not been previously published in whole or in part.

Source of support: Departmental sources

References

- 1.Gonzalez-Valverde FM, Vicente-Ruiz M, Gomez-Ramos MJ. Risk factors of anastomotic leakage in colon cancer. Cir Cir. 2019;87(3):347–52. doi: 10.24875/CIRU.18000616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kanellos I, Mantzoros I, Demetriades H, et al. Sutureless colonic anastomosis in the rat: A randomized controlled study. Tech Coloproctol. 2002;6(3):143–46. doi: 10.1007/s101510200033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aysan E, Dincel O, Bektas H, Alkan M. Polypropylene mesh covered colonic anastomosis. Results of a new anastomosis technique. Int J Surg. 2008;6(3):224–29. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tekos A, Prodromaki E, Papadimou E, et al. Aminoglycosides suppress tRNA processing in human epidermal keratinocytes in vitro. Skin Pharmacol Appl Skin Physiol. 2003;16(4):252–58. doi: 10.1159/000070848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Subhas G, Bhullar JS, Cook J, et al. Topical gentamicin does not provide any additional anastomotic strength when combined with fibrin glue. Am J Surg. 2011;201:339–43. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2010.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Evans DM, Mc Aree K, Guyton DP, et al. Dose dependency and wound healing aspects of the use of tissue plasminogen activator in the prevention of intra-abdominal adhesions. Am J Surg. 1993;165(2):229–32. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(05)80516-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yılmaz G, Özdenkaya Y, Karatepe O, et al. Effects of polyurethane membrane on septic colon anastomosis and intra-abdominal adhesions. Turk J Trauma Surg. 2021;27(1):440–45. doi: 10.14744/tjtes.2020.41624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vaneerdeweg W, Hendriks JMH, Lauwers PRM, et al. Effect of gentamicin-containing sponges on the healing of colonic anastomoses in a rat model of peritonitis. Eur J Surg. 2000;166:959–62. doi: 10.1080/110241500447137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bolzam-Nascimento R, Coy CS, Pereira YE, et al. Influence of omentoplasty on colonic anastomosis in animals submitted to hemorrhagic shock in rats. Acta Cir Bras. 2009;24:233–38. doi: 10.1590/s0102-86502009000300013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]