Abstract

The Ethics Code for Behavior Analysts (Behavior Analyst Certification Board, 2020a) states that behavior analysts must provide services based on the published scientific evidence (Code 2.01, “Providing Effective Treatment”) and maintain competence by reading relevant scholarly literature (Code 1.06, “Maintaining Competence”). Carr and Briggs (2010) acknowledged several potential barriers that might prevent behavior analysts from pursuing this obligation and offered helpful recommendations for circumventing these barriers. Although the nature of these barriers has primarily stayed the same since the publication of Carr and Briggs, the profession and field have grown more complex over the past decade, and several additional barriers have emerged. Luckily, technological advances and resources recently made available offer additional solutions for behavior analysts to consider adopting. Therefore, the purpose of this article is to provide an update to the strategies described by Carr and Briggs for overcoming barriers related to searching the literature, accessing journal content, and contacting the contemporary literature. In addition, we conclude with how leaders might incorporate the proposed strategies into their organization at a systems-wide level.

Keywords: continuing education, ethical obligation, evidence-based practice, information literacy, professional development

Behavior analysis is a unique discipline in that its use of predominantly single-case research designs provides the opportunity for demonstrating rigorous control over behavior without the need for large sample sizes (although such studies exist and amplify the generality of treatment effects; e.g., 152 functional analyses of self-injurious behavior; Iwata et al., 1994). As such, important research may be generated efficiently from one or more participants and submitted for consideration in the peer-review process. This results in relatively quick dissemination to behavior analysts, allowing them to consider the implications of the research as it relates to their conceptual framework as scientists and the manner in which they practice with clients. For example, recent studies have been published that might have implications for a large swath of clients (e.g., increasing head elevation during tummy time; Mendres-Smith et al., 2020) or idiosyncratic client concerns that a practitioner struggles to treat due to a lack of studies on the topic (e.g., assessment and treatment of automatically reinforced aggression; Saini et al., 2015).

Although one can see a vast array of impactful articles by examining the table of contents of applied behavior-analytic journals (e.g., Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis [JABA], Behavior Analysis in Practice [BAP]), one needs to look no further than the abundance of articles published over spring and summer 2020 aimed at assisting practitioners during the COVID-19 pandemic. Indeed, in JABA and BAP alone, researchers published approximately 30 papers related to COVID-19 and telehealth across just a few months. Although the abundance of novel papers is impressive, these articles can be difficult to access outside of an academic institution or daunting to consume for many behavior analysts who have minimal resources or time.

Because behavior analysts are obligated to remain in contact with the literature as part of their professional development, and their clients have a right to effective treatment based on that literature (Behavior Analyst Certification Board [BACB], 2020a), some researchers have attempted to provide behavior analysts with resources to facilitate contact with and consumption of recent research in the behavior analyst’s area of practice. In one such example, Carr and Briggs (2010) published a resource that (a) identified common barriers to accessing and consuming contemporary literature and (b) proposed several solutions for circumventing each barrier that could increase the likelihood of accessing and contacting the novel research. Since its publication, Carr and Briggs has been cited regularly, resulting in papers expanding on its proposed solutions for increasing access to and contact with the literature (e.g., Dubuque, 2011; Parsons & Reid, 2011) or the paper’s content as it relates to ethics and supervision for behavior analysts (e.g., Brodhead et al., 2018; Sellers, Valentino, & LeBlanc, 2016b).

Although Carr and Briggs (2010) identified solutions to potential barriers that remain helpful today, new barriers have emerged over the past decade, and novel solutions are needed. In addition, some of the original solutions are now outdated, and a variety of new resources have become available that serve as updated solutions for both new and old barriers. For example, (a) tabulated information on journals has changed due to cancellations or publisher modifications; (b) technologies that Carr and Briggs recommended, such as Google Reader, are no longer accessible; and (c) behavior analysts with limited resources can now interact with other researchers and access articles in new ways (e.g., using ResearchGate). Our updated strategies for making regular contact with the scholarly literature presented herein are based on an initial list of updated barriers and solutions compiled, organized, and proposed by the first author. This list was subsequently reviewed by the second author, who made suggestions for adding and removing barriers and solutions and organizing the list before it was agreed on and finalized by both of us. Several variables influenced our incorporation of items on this list, including (a) consideration of the original list proposed by Carr and Briggs; (b) recently published articles, chapters, and newsletters dedicated to discussing new strategies or resources for accessing the scholarly literature; and (c) our own experiences as student, scholar, supervisor, and instructor in the field of behavior analysis over the past decade.

The purpose of this article is to provide an updated review of barriers and solutions for contacting and consuming the behavior-analytic literature to assist practitioners over the next decade. In the sections that follow, we review the original barriers and solutions to searching, accessing, and contacting the behavior-analytic literature and provide updated information for each of these sections. In addition, we provide updated journal information (Table 1) and a summary of the updated barriers and solutions (Table 2). Finally, because many leaders may have a goal of creating a “culture of curiosity”—an organization that values dissemination, discussion, and production of research ideas—with an emphasis on refining clinical practice with research, we conclude with how leaders might incorporate the proposed strategies at a systems level. Similar to Carr and Briggs (2010), the following recommendations assume that the practitioner has acquired the necessary repertoires for searching and accessing the scholarly literature (e.g., they can navigate journal and database websites efficiently) and consuming the content after contacting it (e.g., they can interpret and apply concepts into practice).

Table 1.

An Updated Sample Journal List Illustrating Titles Relevant to the Practice of Applied Behavior Analysis in Developmental Disabilities

| Journals | No. of issues per year | Individual subscription cost | Indexed in PsycInfo | Indexed in ERIC b | Searchable website | Online-first articles | Articles freely available online | TOC email alerts | RSS feed available |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities | 6 | $356 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| The Analysis of Verbal Behavior | 2 | $99 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes d | Yes | Yes |

| Behavior Analysis in Practice | 4 | $99 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes d | Yes | Yes |

| Behavior Analysis: Research and Practice (formerly The Behavior Analyst Today) | 4 | $84 a | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes e | Yes | Yes |

| Behavioral Development | 2 | $44 a | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes e | Yes | Yes |

| Behavior Modification | 6 | $203 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Behavioral Interventions | 4 | $1,635 b (institutional) | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes f | Yes | Yes |

| Child and Family Behavior Therapy | 4 | $180 (online) | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes e | Yes | Yes |

| Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities (formerly Education and Training in Developmental Disabilities) | 4 | Free (online) | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| Education and Treatment of Children | 4 | $66 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes g | Yes | No |

| European Journal of Behavior Analysis | 2 | $55 | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Exceptional Children | 4 | $129 | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities | 4 | $79 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis | 4 | $51 b (online) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes d | Yes | Yes |

| Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders | 12 | $199 (online) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Journal of Behavioral Education | 4 | $99 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities | 6 | $99 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Journal of Organizational Behavior Management | 4 | $232 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes h | Yes | Yes |

| Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions | 4 | $79 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Perspectives on Behavior Science (formerly The Behavior Analyst) | 4 | $99 c | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes e | Yes | No |

| The Psychological Record | 4 | $99 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No |

Note. ERIC = Education Resources Information Center; TOC = table of contents.

aIncluded with American Psychological Association membership. b Included with Board Certified Behavior Analyst or Board Certified Assistant Behavior Analyst certification. c Included with Association for Behavior Analysis International membership. d All issues except for the 2 most recent years are available at www.pubmedcentral.com. e All issues except for the 2 most recent years are available on the journal’s website. f A rotating sample issue is available. g Select articles are made available. h All issues except for the most recent year are available on the journal’s website.

Table 2.

Original and Updated Barriers and Proposed Solutions for Searching, Accessing, and Contacting the Research Literature

| Task | Barriers | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Searching the literature | • Deciding where to start can be daunting. | • Access ABA subspecialty area resources offered by the BACB. |

| • Searching individual journal websites is inefficient. | • Access available resources for searching specialized areas of practice. | |

| • General web searches produce many “false positives.” | • Contact members from relevant ABAI SIGs. | |

| • Access to the PsycInfo database may be limited or costly. | • Use individual or organizational subscriptions to PsycInfo. | |

| • Get PsycInfo access via an alumni-association membership. | ||

| • Deduct PsycInfo expense on your tax return. | ||

| • Gain access to ERIC’s searchable database with the BCBA/BCaBA credential. | ||

| Accessing journal content | • Access to journals may not be reliable. | • Consult with established clinicians/researchers to become familiar with relevant journals. |

| • Journal subscriptions are expensive. | • Compile a list of relevant journals to follow on a routine basis. | |

| • There are many relevant journals to follow. | • Follow inexpensive or free journals when possible. | |

| • Author contact information may not always be up to date. | • Gain access to archived articles in PubMed Central. | |

| • Gain access to the library via an adjunct appointment or alumni membership. | ||

| • Use ResearchGate to access content (e.g., contact authors for preprints). | ||

| • Access JABA, JEAB, and BI articles with the BCBA/BCaBA credential. | ||

| Contacting the contemporary literature | • It is difficult to keep up with a multitude of articles published in both behavioral and nonbehavioral journals. | • Organize bookmarks to journal sites in your web browser. |

| • It is effortful to follow multiple journals. | • Routinely visit journal sites to review online-first articles. | |

| • The environment does not support the activity. | • Sign up for table-of-contents email alerts. | |

| • There is limited time to dedicate to reviewing content. | • Use an aggregator to monitor updates to journal websites. | |

| • Follow researchers, articles, and projects on various social platforms (e.g., ResearchGate). | ||

| • Subscribe to research collation services (e.g., Current Contents in ABA). | ||

| • Use self-management procedures. | ||

| • Follow behavior-analytic blogs and podcasts. | ||

| • Set contingencies and dedicate time to reviewing relevant content. | ||

| • Create a supportive verbal community. | ||

| • Consult with senior practitioners/researchers to become familiar with relevant content. | ||

| • Post articles or discuss content on various social media platforms. | ||

| • Start or join a journal club. |

Note. Italicized items indicate an updated barrier or solution. ABA = applied behavior analysis; BACB = Behavior Analyst Certification Board; ABAI SIGs = Association for Behavior Analysis International special interest groups; BCBA = Board Certified Behavior Analyst; BCaBA = Board Certified Assistant Behavior Analyst; JABA = Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis; JEAB = Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior; BI = Behavioral Interventions.

Searching the Literature

The ability to locate relevant literature is a crucial first step toward making regular contact with the discipline’s scholarly work. In addition to the barriers and solutions associated with searching the literature described in Carr and Briggs (2010), we identified a new barrier that may precede all others, and offer several updated solutions for navigating these potential obstacles.

Barriers

A practitioner’s quest to locate literature related to a particular behavioral concern may be delayed from the start if they are not sure where they should even begin their search. For instance, a practitioner may be presented with a novel scenario (e.g., a child who engages in trichotillomania) or a unique case (e.g., an adult diagnosed with an intellectual disability who is showing early signs of dementia). The practitioner might be unsure about whether they need to search literature in the field of behavior analysis, clinical psychology, behavioral medicine, or behavioral gerontology in order to identify relevant articles for addressing their practice or research needs. Standing at the edge of this vast literary expanse can be daunting, and exploring multiple databases and digging through mostly unrelated and unusable articles are certainly not efficient search strategies.

Even when a practitioner is aware of a relevant journal to search or which keywords to incorporate, barriers related to using a journal’s searchable database or relying on an internet search engine still exist. That is, searching a journal’s database will only yield results found within that particular journal, and it may miss relevant literature published elsewhere. Additionally, if a practitioner commits to this search strategy, searching the database for multiple journals represents an inefficient search method. Conversely, entering relevant keywords into an internet search engine (e.g., Google) might reduce the effort associated with searching multiple journals. However, substantial effort is now required to sift through “false positive” hits (e.g., clinic websites, literature from other disciplines, non-peer-reviewed articles) and filter out other irrelevant content. Although Google Scholar is a freely accessible search engine that indexes scholarly literature and may help to narrow the scope of search results, its search parameters are basic and do not offer options to limit content to the relevant discipline (e.g., psychology, education) or exclude non-peer-reviewed content (e.g., unpublished dissertations). As an alternative, PubMed Central (PMC) is a free digital repository that archives open-access, full-text scholarly articles (in biomedical and life science journals) and offers a search engine with more parameters to hone one’s search; however, most of the open-access content on PMC is at least 2 years old. Therefore, this may not be the most effective method for searching the contemporary literature either.

The PsycInfo database may be the best available resource for identifying behavior-analytic content because it provides systematic coverage of the psychological literature. In addition, the PsycInfo search tools include a variety of helpful parameters to enhance one’s search of records (e.g., the option to exclude non-peer-reviewed articles or include only articles published in English). Although practitioners may have relied on PsycInfo to access content freely with minimal effort during their undergraduate and graduate careers, it is rare for professional organizations or clinics to subscribe to this (or other) searchable databases due to their associated cost.

Solutions

If faced with an unfamiliar practice issue that remains within one’s scope of competence,1 we suggest that practitioners explore resources that (a) offer educational materials and relevant literature for applied behavior analysis subspecialty areas (e.g., clinical behavior analysis, gerontology, behavioral pediatrics; BACB, 2019), (b) identify noteworthy articles for practicing behavior analysts (e.g., Gillis & Carr, 2014), or (c) include literature reviews of diverse practice areas (e.g., individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities who develop dementia; Lucock et al., 2019). Additionally, practitioners may choose to reach out to experts in a given area to learn more about relevant journal outlets or recommended articles. To locate an expert, one might peruse the special interest groups (SIGs) of the Association for Behavior Analysis International (ABAI) to locate a relevant group and member contact information2.

As of December 2020, individuals could subscribe to PsycInfo, such as by paying for the PsycNet Gold database package that includes electronic access to journals and books published by the American Psychological Association (APA). The price for full access to PsycInfo (via the APA PsycNet Gold package) has decreased slightly over the years. Since reported in Carr and Briggs (2010), the cost has decreased from $149 to $139 for APA members and from $500 to $499 for nonmembers. If practitioners are considering this route, it may be cheaper to become a member of APA ($100 per year for first-time members, plus a $35 enrollment fee) and purchase the APA PsycNet Gold package for $139 (totaling $274) as compared to paying $499 to access APA PsycNet as a nonmember. Although APA membership is available to a wide range of students (e.g., high school, undergraduate, graduate) and professionals in psychology and related fields, the previously mentioned membership rate is for those who may be most in need of accessing PsycInfo. That is, we present the membership dues for becoming an APA member (bacehlor’s level) or associate member (master’s level) for a practitioner who is not already a student or teacher.

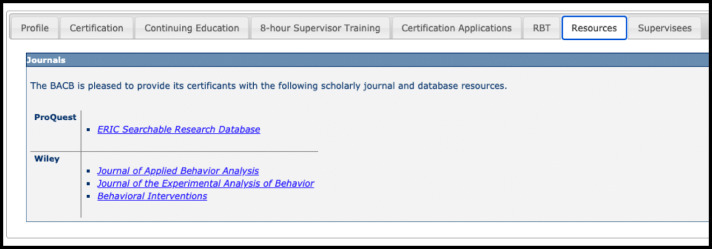

Of course, the cost associated with access to PsycInfo may present an additional financial barrier. Therefore, we suggest that practitioners either (a) negotiate with their place of employment for APA membership and access to PsycInfo as part of their hire, (b) pursue an alumni-association membership or adjunct appointment that might come with access to university library resources, or (c) declare the expense as a Schedule C deductible on one’s annual federal tax returns (in the United States only) in an attempt to mitigate the cost associated with gaining access to PsycInfo. If the cost of PsycInfo cannot be reduced, there are several freely available search engines that index the full text or metadata of scholarly literature across an array of publishing formats and disciplines, including Google Scholar or PMC. Another solution for searching the literature while also mitigating the cost associated with PsycInfo is to use the Education Resources Information Center (ERIC) searchable research database of indexed and full-text education literature and resources, which is now available to all BACB certificants in the Resources tab of their Certification Gateway (BACB, 2014, pp. 1–2; see Figure 1). ERIC indexes a wide variety of journal sources relevant to practicing behavior analysts, including 10 of the 21 journals listed in Table 1 (e.g., The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, JABA, Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, Journal of Behavioral Education).3

Fig. 1.

BACB Certification Gateway and Scholarly Journal and Database Resources

Accessing Journal Content

Not only do practitioners need to become familiar with journals that publish innovative research relevant to their practice area, but they are also obligated to ensure they have reliable access to this content. Although the barriers related to accessing journal content remain primarily the same, we introduce an additional barrier in what follows and review how recent advances in available resources offer additional solutions for practitioners looking to access content easily and affordably.

Barriers

Even after successfully searching for and locating an article related to one’s area of practice, a practitioner may only be granted access to the title and abstract, whereas the remaining content is restricted behind a paywall. For instance, 16 out of 21 journals (76.2%) listed in Table 1 require a subscription to access all of the journals’ published content. Another option would be to pay for the individual article; however, the cost of an individual article is so expensive that one might as well pay the individual subscription price. For example, it costs approximately $40 to purchase an individual article from The Psychological Record, whereas purchasing a 1-year subscription would cost $99.

Although practitioners are fortunate to have many journals that they can rely on to inform their research and clinical practice, purchasing individual subscriptions to all these journals to access their content is likely impossible financially for most practitioners. Alternatively, practitioners can contact the authors of articles directly to request access to prepublication copies of manuscripts (e.g., a word-processing file). However, authors’ contact information provided in the Author Note of articles may not reflect the most up-to-date address of the corresponding author, especially if it is an older article and the author has since changed affiliations or retired.

Solutions

The primary solutions offered by Carr and Briggs (2010) for accessing journal content remain viable; however, the development of a social networking site for researchers and recent access to several journal subscriptions from the BACB have also improved practitioners’ ability to access content easily and affordably. We still recommend consulting with a senior practitioner or established researcher to become familiar with journals related to one’s area of practice and to compile a small list of relevant journals to follow on a routine basis. We also recommend subscribing to inexpensive journals (e.g., an online subscription to BAP is $99) and being familiar with which journals practitioners have access to through professional memberships (e.g., Perspectives on Behavior Science is included with an ABAI membership) or which journals offer all or some of its content for free (e.g., Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities). In addition, we recommend that practitioners explore the available search features and content offered by PMC, made available through the U.S. National Institutes of Health’s National Library of Medicine. Many journals containing behavior-analytic content are indexed in PMC (e.g., The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, BAP) and make their content available either (a) immediately or (b) following an embargo period (e.g., a delayed release of content from anywhere between a few months and 2 years). Most journals provide free access to full-text articles in PMC within a year of publication. Further, if articles remain unavailable for whatever reason, or practitioners need to access content published within a textbook, the practitioner with a continued affiliation to a university (e.g., alumni-association member, adjunct faculty member) may request these items through an interlibrary loan.

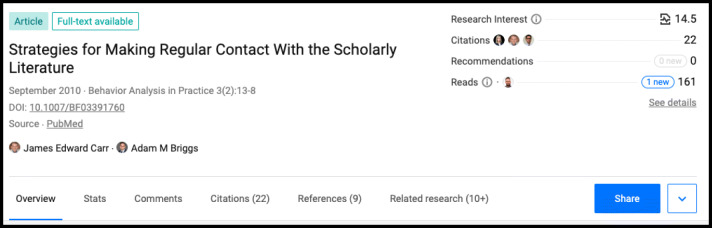

There have been two primary advances since the Carr and Briggs (2010) publication that have improved practitioners’ ability to affordably access journal content with ease. First, the advent of a social networking site for scientists and researchers called ResearchGate (https://www.researchgate.net/) has made it easier for practitioners to access journal content.4 ResearchGate allows one to directly connect with researchers, making it easier to monitor newly added research, peruse previously published content, download available articles, and request articles directly from the researchers themselves (see Figure 2). Second, the BACB provides free subscriptions to JABA, the Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, and Behavioral Interventions to all BACB certificants in the Resources tab of their Certification Gateway (BACB, 2016, p. 1; see Figure 1). The addition of these available resources has improved behavior analysts’ access to relevant journal content, which should have a profound effect on the likelihood that practitioners will access and subsequently contact the scholarly literature.

Fig. 2.

Example of an Article Displayed Within ResearchGate. Note. The top-left corner indicates a full-text version of this article is available for free download. Practitioners also have the option to share the article (bottom-right corner) and can select the drop-down menu in this corner to access other options, such as following or recommending the article. Finally, if the practitioner wanted to directly contact an author, they would select the author’s name to navigate to their profile and would have an option to directly send them a message once here.

Contacting the Contemporary Literature

Simply removing barriers related to searching for and accessing behavior-analytic literature improves the likelihood that the behavior analyst will end up with a relevant article; however, it does not guarantee that they will make regular contact with the contemporary literature. That is, barriers that interfere with one’s ability to actively engage in and keep up with consuming the content of the behavior-analytic literature exist. We review these barriers and discuss several novel solutions for ensuring practitioners are staying in regular contact with relevant literature.

Barriers

As previously mentioned, the sheer number of articles published across an increasing number of relevant journals makes it challenging to follow multiple journals in order to regularly keep up with all of this content, especially when articles are published in non-behavior-analytic journals. Certainly, this growth is promising for behavior analysis as a field. That is, high rates of publication across a variety of peer-reviewed outlets provide evidence that applied behavior analysis remains a widely accepted and effective approach that values continuous improvement in and dissemination of its advancing applied technology.

Yet, as demand for behavior analysts increases (BACB, 2020c) and the rise of insurance funding and mandates compel clinics to prioritize activities related to reimbursement and the maximization of billable hours (McBain et al., 2020; Sundberg, 2016), practitioners may find that they allocate more of their weekly hours on client and clinical concerns and have less time for staying in contact with the contemporary behavior-analytic literature. Therefore, good habits and powerful systems-level solutions are needed to ensure behavior analysts are prioritizing time to monitor and consume relevant literature.

Solutions

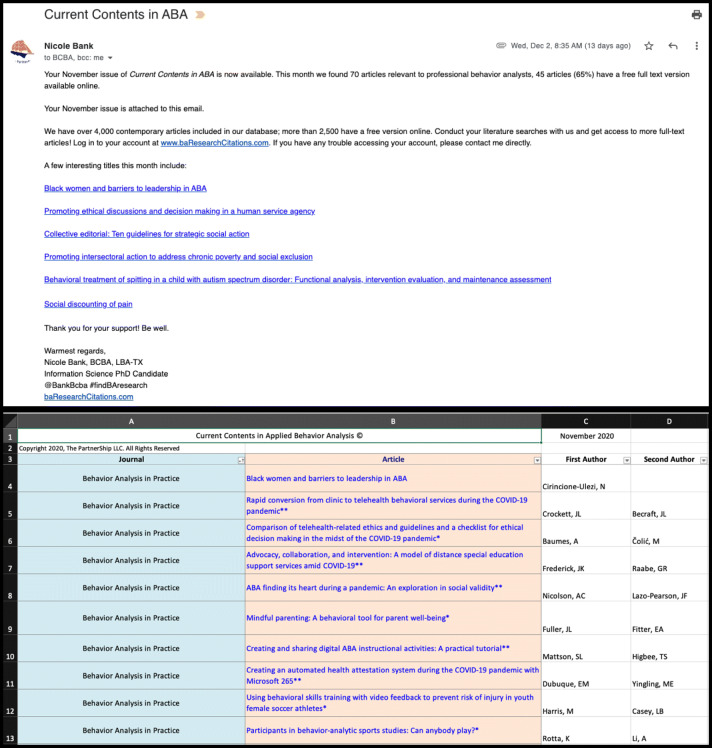

We recommend arranging several antecedent and consequent strategies in order to routinely engage with the contemporary behavior-analytic literature. First, practitioners might choose to bookmark links to sites that regularly display newly published research (e.g., JABA’s Early View, ResearchGate’s Home feed) on their browser to reduce response effort and prompt regular visits to these sites (see Fig. 1 of Carr and Briggs, 2010, p. 16). Second, and in addition to the previous recommendation, practitioners might sign up for email alert services for journals that offer table-of-contents alerts, or use RSS feed aggregators as a tool to track, gather, and organize relevant literature (see Dubuque, 2011, for a description on how to create and manage RSS feeds; see Table 1 for list of journals that offer these services). Further, practitioners can create an account with a site that shares research and allows one to follow researchers, articles, and projects (e.g., Google Scholar, Mendeley, ResearchGate) and sign up for regular email alerts that provide research recommendations based on one’s activity and interests. Further, practitioners can choose to subscribe to a service that collates the latest research related to practicing behavior analysts and sends monthly summary emails (e.g., Current Contents in ABA; https://www.baresearchcitations.com/) as a similar strategy for having relevant content pushed to the practitioner’s email (see Figure 3).

Fig. 3.

Example of Aggregated Information Received From Current Contents in ABA.

Note. Monthly email (top image) and tabulated information (bottom image) received from Current Contents in ABA

In addition to the antecedent procedures described previously, we also recommend arranging contingencies that promote ongoing contact with the literature. These contingencies can include self-management and systems-level arrangements. It is likely that practitioners did not become well-trained behavior analysts without engaging in effective self-management practices. That is, the repertoires that contributed to engaging in regular and effective study habits (e.g., time management) are the same repertoires required for monitoring and engaging with recently published behavior-analytic content. Luckily, there are now many more ways to engage with behavior-analytic content that make this task less effortful and perhaps more engaging. There are a number of behavior-analytic blogs (e.g., ABAI’s Behavior Science Dissemination series; https://science.abainternational.org/) and podcasts (e.g., The Behavioral Observations Podcast; https://behavioralobservations.com/) that a practitioner might follow to access other behavior analysts’ commentary on current newsworthy events and recently published research.

Of course, practitioners could also rely on self-management strategies to select and read recently published research on a regular basis; however, we recognize that this habit might be challenging to maintain over time. Therefore, we recommend several strategies for arranging systems-level contingencies to promote regular engagement with the literature. First, it is important to establish a verbal community with which the practitioner can share and discuss the latest research. If practitioners surround themselves with professionals who are also interested in pursuing the recently published research and discussing it, there is a greater likelihood that at least one of the members of this verbal community will identify a relevant article and share it within this group. It may be wise for practitioners to consult with senior practitioners or established researchers to help them and their verbal community keep a finger on the pulse of the contemporary literature. If there is a barrier to forming a verbal community at one’s place of work, there are always opportunities to harness the power of social media to join other verbal communities (e.g., the Applied Behavior Analysis Facebook group) to share articles one has found interesting and useful or to engage in behavior-analytic discussion with others within this virtual verbal community. Finally, it may be useful to organize a reading group and assign an article to be discussed within one’s verbal community (i.e., a journal club; Parsons & Reid, 2011). A contingency to meet regularly and discuss a recent or relevant article can be accomplished within a small group of colleagues or at an organizational level and simply requires a dedicated group of curious colleagues who commit to setting time aside on a regular interval to review new, relevant, and interesting literature. The journal-club liaison may choose to strategically assign articles that cover large areas of research (e.g., literature reviews) or to provide useful suggestions (e.g., practice recommendations) so that members may contact large amounts of information in a concise and consumable manner that can be immediately incorporated into practice (e.g., JABA’s brief-review format; e.g., Erath & DiGennaro Reed, 2020). Next, we expand on these strategies by providing suggestions for creating a culture of curiosity that integrates systems-level contingencies to promote a community of engagement.

Suggestions for Systems-Level Integration

Businesses and other health care professions have promoted the idea of creating a culture of curiosity within organizations that encourages staff innovation to deliver more effective services and develop novel refinements to address challenges (e.g., Eason, 2010; Kaplan, 2020; Kedge & Appleby, 2009). As mentioned in the introduction, organizations that promote a culture of curiosity value dissemination, discussion, and production of research ideas. For example, Kaplan (2020) described “leaders who recognize the power of an organizational culture in which all team members can be curious about what is possible, be creative, and realize their full potential on behalf of those they serve” (p. 13). Similarly, Satya Nadella, the chief executive officer of Microsoft Corporation, noted that one of the most important components of long-term success at Microsoft is culture: “We want to be not a ‘know-it-all’ but a ‘learn-it-all’ organization” (Majdan & Wasowski, 2017, para. 12). In behavior-analytic organizations, this might involve an emphasis on consuming research regularly, integrating said research into practice, and encouraging the development of novel applications of behavior analysis in clinical or research protocols (Kelley et al., 2015; Valentino & Juanico, 2020).

Perhaps in an effort to establish similar values, the BACB’s (2020a) Ethics Code for Behavior Analysts describes the importance of maintaining competence by reading the relevant scholarly literature and providing clients with the empirically supported treatments derived from that literature base. As outlined in the preceding sections, behavior analysts are obligated to adhere to this code, and there are several solutions for difficulties accessing and consuming new research. However, self-administered contingencies can be challenging to maintain (e.g., McReynolds & Church, 1973). A more encompassing solution for a group of behavior analysts seeking to overcome the aforementioned barriers is for leaders to enrich the environment of their behavior analysts with opportunities to access and consume new research while encouraging the integration of newly supported treatment refinements into routine clinical practice. Although a systematic review of literature from areas such as organizational behavior management related to this point is beyond the scope of this article, what follows are some examples of how leaders might create a culture of curiosity that encourages research consumption and generation.

Organizations can program antecedent strategies to encourage research consumption. To resolve accessibility concerns, leaders can purchase subscriptions to journals not otherwise accessible within one’s BACB Certification Gateway or their professional memberships. Similarly, leaders could purchase access to aggregators (e.g., Current Contents in ABA) so staff can more easily navigate and consume new research in their area. Certainly, this type of financial support is not always possible for small organizations. Antecedent strategies with a minimal cost or time allocation might also include (a) arranging calendar reminders to check journals or databases, (b) disseminating newly discovered articles in emails or staff meetings, or (c) assisting inexperienced staff in creating profiles on research websites such as Google Scholar or ResearchGate.

Although antecedent strategies may resolve some concerns, organizations might program workplace contingencies to promote research consumption, integration, or production. For example, designating one meeting per month as a reading group might encourage staff to read and critically analyze new research, whereas focused discussions could highlight areas for integration into practice or generation of new research ideas (see Parsons & Reid, 2011, for more information on how to arrange reading groups). Further, staff could do this on a smaller scale in Board Certified Behavior Analyst or Registered Behavior Technician supervision meetings, which would allow the staff members to remain in contact with the literature while shaping the fundamental behavior-analytic skills of their supervisees.

Leaders could also designate periods in their staff’s schedules for professional development with the expectation of some relevant product to indicate that the staff used the time appropriately. Leaders can program an hour per week for their staff to make progress on research design, data analysis, or manuscript writing, with the expectation that the staff can depict their progress during follow-up. To limit disruption and enhance the staff’s experience, the leader could ensure that other staff are aware of the individual’s unavailability during that time or allow the staff to work out of the office (e.g., outside during the summer, at a local coffee shop in the winter). Leaders could also ask staff to (a) read new research and summarize the work in a later staff meeting or (b) develop ideas that can be supported through internal or community grants or used to evaluate the organization’s current practices. For example, leaders might ask staff to use this dedicated time to review special issues on topical concerns (e.g., BAP’s special issue on diversity [Volume 12, Issue 4] or its COVID-19 collection), such as evaluating the organization’s current practices for interacting with transgender and gender-nonconforming individuals using Leland and Stockwell’s (2019) assessment tool.

One limitation of these recommendations is that they rely on organizational leadership that arranges contingencies to promote the staff contacting and consuming literature. As such, these strategies may not necessarily result in the maintenance and generalization of the professional skills cultivated by the organization’s contingencies should the leadership team or programmed contingencies change. As Sellers, LeBlanc, and Valentino (2016a) described, supervisors can suggest (or provide proactively) resources related to effective organization and time management. We recommend leaders supplement organizational contingencies with strategies related to self-management, such as by providing access to the various resources described in Sellers, LeBlanc, and Valentino or the many freely or commercially available trainings or electronic applications aimed at improving self-management. Supporting independent consumption of research also may be helpful if staff prefer self-management contingencies to organizational contingencies and if they continue to meet professional and organizational goals under these arrangements.

Finally, leaders can model behavior related to a culture of curiosity. When clients present with novel concerns, leaders can demonstrate how to effectively consult the literature and incorporate or expand on relevant research during routine clinical care, or guide others in this type of behavior. Leaders can instill a culture of questioning in which they encourage staff to ask questions, reinforce skepticism and critical analysis, and minimize aversive consequences related to asking questions (e.g., allowing anonymity to limit staff anxiety related to asking questions in front of peers).

Conclusion

The tactics and strategies proposed by Carr and Briggs (2010) for maintaining contact with the contemporary literature and their associated barriers have largely endured over the past decade; however, as anticipated by the authors of the original publication, some of the tactics and strategies for circumventing these barriers have become outdated (e.g., Google Reader), and the advent of technology and the availability of other resources (e.g., ResearchGate, access to JABA via the BACB Certification Gateway) have improved practitioners’ ability to search, access, and contact contemporary literature. We described one additional barrier for each repertoire and offered four new solutions for addressing the barriers related to searching the literature, two new solutions for accessing journal content, and seven new solutions for contacting the contemporary literature (see Table 2 for a summary). Most of the added solutions addressed barriers related to contacting contemporary literature, which is arguably the most important step in keeping up with the scholarly literature because it involves arranging contingencies to improve or maintain research consumption over time when those articles are readily accessible.

We updated the journal list in Table 1 to reflect journals that regularly publish behavior-analytic content (i.e., at least one behavior-analytic article per issue during the most recent 2 years). This process resulted in adding two new journals and removing five journals, totaling 21 journals in Table 1. The new journals added were Behavioral Development and the European Journal of Behavior Analysis. Journals were removed because they either no longer published behavior-analytic content regularly (i.e., Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, Research in Developmental Disabilities) or because they were discontinued (i.e., Journal of Behavior Assessment and Intervention in Children, Journal of Precision Teaching & Celeration, Journal of Speech-Language Pathology and Applied Behavior Analysis). Given that the purpose of the journal list is to provide recommendations for staying in contact with the contemporary behavior-analytic literature, we felt it was justified to remove journals that were no longer publishing behavior-analytic content regularly (or at all) from this list. In addition, we provided updated journal names for three journals (see Table 1 for updated tabulated journal information).

Another interesting finding is that, since Carr and Briggs’s (2010) publication, a greater proportion of behavior-analytic journals have adopted strategies to make their content more available and easily accessible. Specifically, when comparing the information reported on the 24 journals in Table 1 from Carr and Briggs (p. 15) to the 21 journals in Table 1 of the present article, we noted improvements in nearly all of the categories analyzed across the journals, including (a) more journals with searchable websites (from 62.5% to 95.2% of journals), (b) more journals with advanced online publication (from 41.6% to 90% of journals), (c) a greater number of journals providing freely available articles (from 29.2% to 71.4% of journals), (d) greater inclusion of table-of-contents alert emails across all journals (from 70.8% to 100% of journals), and (e) improved RSS feed availability (from 45.8% to 62% of journals). In addition to noting the journals indexed within PsycInfo, we added information regarding whether journals are indexed in ERIC (10 of 21 journals, or 47.6%), given that BACB certificants now have access to this resource (BACB, 2014).

As previously noted, behavior-analytic research continues to be published at a high rate, which is a great indication of the vitality of the field and practice, especially because demand for effective behavior-analytic service delivery continues to grow (BACB, 2020c). Therefore, we suggest it is more important than ever for practitioners to adopt methods for successfully staying in contact with the scholarly literature and for organizations to arrange contingencies to create a culture of curiosity. Fortunately, technological advances and improved availability of resources have made it easier for practitioners to search, access, and contact the contemporary literature. As researchers, practitioners, organizations, and associations continue to make staying in contact with the literature a priority in the field, we suspect that those pursuing this goal will continue to develop solutions for successfully navigating the remaining barriers. In addition, we assume that technological advancements will continue to offer new and improved solutions. Until then, we hope that this resource assists practitioners with navigating these barriers and offers helpful solutions for improving individual and systems-level strategies for achieving this goal.

Author Note

We thank Jim Carr for his helpful comments on an earlier version of this manuscript.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest (such as honoraria; educational grants; and membership, employment, consultancies, stock ownership, or other equity interest) in the subject matter, materials discussed, or resources recommended in this article.

Ethical approval

This is a discussion article that does not contain data from human participants; therefore, no ethical approval was required.

Footnotes

Practitioners should use Brodhead et al. (2018) as a resource to assess whether an unfamiliar practice area is within one’s scope of competence. If the unfamiliar practice issue is outside of one’s scope of competence, we direct them to resources that (a) provide strategies for developing competence in a new consumer area (LeBlanc et al., 2012), (b) describe tactics for evaluating the evidence base of a nonbehavioral intervention in an expanded consumer area (Walmsley & Baker, 2019), or (c) offer recommendations for respecialization in a new area of practice (BACB, 2020b).

(visit https://www.abainternational.org/constituents/special-interests/special-interest-groups.aspx for a complete list of ABAI SIGs)

We support responsible sharing of articles that adhere to ResearchGate’s policies and the publisher’s copyright laws. For instance, we support authors’ freedom to publicly post and share open-access articles or privately share preprints (when requested) of published articles that are under an embargo by the publisher.

Please note that, at the time of this manuscript submission in December 2020, the ProQuest policy stipulated that the database should only be used by BACB certificants not currently employed by a higher education institution or a hospital.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2014). A new resource for BACB Certificants. BACB Newsletter: A special issue on the ProQuest benefit, 1–2. https://www.bacb.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/BACB_Newsletter_08-14.pdf

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2016). New journal resources for BCBAs and BCaBAs. BACB Newsletter, 1. https://www.bacb.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/191611-newsletter.pdf

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2019). Applied behavior analysis: Subspecialty areas. https://www.bacb.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Executive-Summary_190520.pdf

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2020a). Ethics code for behavior analysts. https://www.bacb.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Ethics-Code-for-Behavior-Analysts-2102010.pdf

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2020b). Recommendations for respecializing in a new ABA practice area. https://www.bacb.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Respecialization-Guidance_20200611.pdf

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2020c). US employment demand for behavior analysts: 2010–2019. https://www.bacb.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/US-Employment-Demand-for-Behavior-Analysts_2020_.pdf

- Brodhead MT, Quigley SP, Wilczynski SM. A call for discussion about scope of competence in behavior analysis. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2018;11(4):424–435. doi: 10.1007/s40617-018-00303-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr JE, Briggs AM. Strategies for making regular contact with the scholarly literature. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2010;3(2):13–18. doi: 10.1007/BF03391760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubuque EM. Automating academic literature searches with RSS feeds and Google Reader™. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2011;4(1):63–69. doi: 10.1007/BF03391776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eason T. Lifelong learning: Fostering a culture of curiosity. Creative Nursing. 2010;16(4):155–159. doi: 10.1891/1078-4535.16.4.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erath TG, DiGennaro Reed FD. A brief review of technology-based antecedent training procedures. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2020;53(2):1162–1169. doi: 10.1002/jaba.633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillis JM, Carr JE. Keeping current with the applied behavior-analytic literature in developmental disabilities: Noteworthy articles for the practicing behavior analyst. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2014;7(1):10–14. doi: 10.1007/s40617-014-0002-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata BA, Pace GM, Dorsey MF, Zarcone JR, Vollmer TR, Smith RG, Rodgers TA, Lerman DC, Shore BA, Mazalesk JL. The functions of self-injurious behavior: An experimental-epidemiological analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1994;27(2):215–240. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1994.27-215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan GS. Defining a new leadership model to stay relevant in healthcare. Frontiers of Health Services Management. 2020;36(3):12–20. doi: 10.1097/HAP.0000000000000077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kedge S, Appleby B. Promoting a culture of curiosity within nursing practice. British Journal of Nursing. 2009;18(10):635–637. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2009.18.10.42485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley, D. P., Wilder, D. A., Carr, J. E., Ray, C., Green, N., & Lipschultz, J. (2015). Research productivity among practitioners in behavior analysis: Recommendations from the prolific. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 8(2), 201–206. 10.1007/s40617-015-0064-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- LeBlanc LA, Heinicke MR, Baker JC. Expanding the consumer base for behavior-analytic services: Meeting the needs of consumers in the 21st century. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2012;5(1):4–14. doi: 10.1007/BF03391813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leland W, Stockwell A. A self-assessment tool for cultivating affirming practices with transgender and gender-nonconforming (TGNC) clients, supervisees, students, and colleagues. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2019;12(4):816–825. doi: 10.1007/s40617-019-00375-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucock ZR, Sharp RA, Jones RSP. Behavior-analytic approaches to working with people with intellectual and developmental disabilities who develop dementia: A review of the literature. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2019;12(1):255–264. doi: 10.1007/s40617-018-0270-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majdan, K., & Wasowski, M. (2017). We sat down with Microsoft’s CEO to discuss the past, present and future of the company. Business Insider. https://www.businessinsider.com/satya-nadella-microsoft-ceo-qa-2017-4

- McBain RK, Cantor JH, Kofner A, Stein BD, Yu H. State insurance mandates and the workforce for children with autism. Pediatrics. 2020;146(4):1–11. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McReynolds WT, Church A. Self-control, study skills development and counseling approaches to the improvement of study behavior. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1973;11(2):233–235. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(73)80013-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendres-Smith AE, Borrero JC, Castillo MI, Davis BJ, Becraft JL, Hussey-Gardner B. Tummy time without the tears: The impact of parent positioning and play. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2020;53(4):2090–2107. doi: 10.1002/jaba.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons MB, Reid DH. Reading groups: A practical means of enhancing professional knowledge among human service practitioners. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2011;4(2):53–60. doi: 10.1007/BF03391784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saini V, Greer BD, Fisher WW. Clarifying inconclusive functional analysis results: Assessment and treatment of automatically reinforced aggression. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2015;48(2):315–330. doi: 10.1002/jaba.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers TP, LeBlanc LA, Valentino AL. Recommendations for detecting and addressing barriers to successful supervision. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2016;9(4):309–319. doi: 10.1007/s40617-016-0142-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers TP, Valentino AL, LeBlanc LA. Recommended practices for individual supervision of aspiring behavior analysts. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2016;9(4):274–286. doi: 10.1007/s40617-016-0110-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundberg, D. (2016, April 25). The high cost of stress in the ABA workplace. Behavioral Science in the 21st Century. https://bsci21.org/the-high-cost-of-stress-in-the-aba-workplace/

- Valentino, A. L., & Juanico, J. F. (2020). Overcoming barriers to applied research: A guide for practitioners. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 13(4), 894–904. 10.1007/s40617-020-00479-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Walmsley C, Baker JC. Tactics to evaluate the evidence base of a nonbehavioral intervention in an expanded consumer area. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2019;12(3):677–687. doi: 10.1007/s40617-018-00308-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]