Abstract

Forward genetic mapping of F2 crosses between closely related substrains of inbred rodents - referred to as a reduced complexity cross (RCC) - is a relatively new strategy for accelerating the pace of gene discovery for complex traits, such as drug addiction. RCCs to date were generated in mice, but rats are thought to be optimal for addiction genetic studies. Based on past literature, one inbred Spontaneously Hypertensive Rat substrain, SHR/NCrl, is predicted to exhibit a distinct behavioral profile as it relates to cocaine self-administration traits relative to another substrain, SHR/NHsd. Direct substrain comparisons are a necessary first step before implementing an RCC. We evaluated model traits for cocaine addiction risk and cocaine self-administration behaviors using a longitudinal within-subjects design. Impulsive-like and compulsive-like traits were greater in SHR/NCrl than SHR/NHsd, as were reactivity to sucrose reward, sensitivity to acute psychostimulant effects of cocaine, and cocaine use studied under fixed-ratio and tandem schedules of cocaine self-administration. Compulsive-like behavior correlated with the acute psychostimulant effects of cocaine, which in turn correlated with cocaine taking under the tandem schedule. Compulsive-like behavior also was the best predictor of cocaine seeking responses. Heritability estimates indicated that 22%-40% of the variances for the above phenotypes can be explained by additive genetic factors, providing sufficient genetic variance to conduct genetic mapping in F2 crosses of SHR/NCrl and SHR/NHsd. These results provide compelling support for using an RCC approach in SHR substrains to uncover candidate genes and variants that are of relevance to cocaine use disorders.

Keywords: Addiction vulnerability traits, Cocaine, SHR/NCrl substrain, SHR/NHsd substrain

1. Introduction

The addictions, in particular cocaine addiction, are highly heritable neuropsychiatric diseases [1, 2]. Given the nearly 2 million past-month cocaine users in the US, with ~1 million meeting diagnostic criteria for cocaine dependence [3], new research directed at identifying genetic variants that influence cocaine addiction vulnerability will improve diagnosis, prevention, and treatment. One of the only known genome-wide association study (GWAS) hits to date in cocaine dependence was a variant near FAM53B [4] that was functionally supported by covariance between Fam53b expression and cocaine self-administration in recombinant inbred mice [5]. To date, human GWAS of SUD, especially those comprising stimulant and opioid use disorders, lack sufficient sample sizes and thus adequate power to detect the small effects of the vast majority of common variants on risk for substance use disorders [6, 7]. Mammalian forward genetic mapping studies can more rapidly achieve appropriate sample sizes and power to identify genome-wide significant genetic loci underlying behavioral traits relevant to the addictions. Nevertheless, a major limitation of many rodent genetic studies is poor mapping resolution, namely those employing F2 crosses, thus leaving investigators with highly significant loci, yet an intractable number of genes within these large intervals (typically 15-20 cM or ~30-40 Mb) that contain causal genes and variants. In addition to poor mapping resolution, one must also consider the genetic complexity of loci whereby hundreds of genes and thousands of variants typically underlie F2-derived quantitative trait loci and expression quantitative trait loci (QTLs/eQTLs) between classical inbred strains.

A relatively new approach [8–11] involves forward genetic mapping of complex traits in an F2 cross between closely related substrains of inbred rodents - referred to as a reduced complexity cross (RCC). Genetic and/or fine mapping can be used to resolve QTLs/eQTLs and quantitative trait genes (QTGs) in genetic crosses that segregate a low level of genetic diversity. Kumar and colleagues used an RCC between C57BL/6 substrains to map and validate Cyfip2 in cocaine sensitivity [12]. We subsequently used an RCC between similar substrains to map the same Cyfip2 locus and validate Cyfip2 as a genetic factor underlying binge-like eating [13]. Reduced genetic complexity in C57BL/6 substrains was also used to validate a functional intronic variant in the alpha-2 subunit of the GABA-A receptor in regulating Gabra2 transcript and protein expression via CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing [14]. Finally, Phillips and colleagues exploited reduced genetic complexity between DBA/2 substrains to identify a functional coding variant in Taar1 (trace amine-associated receptor 1) underlying differences in the aversive properties of methamphetamine self-administration and body temperature [15, 16]. These examples show that the use of RCCs for complex trait analysis can accelerate the pace of gene discovery for complex traits relevant to addiction and thus address this challenging public health concern.

The RCC approach to date has only been conducted in mice, but it is widely recognized that rats are optimal for addiction genetic studies because phenotype definitions for addiction vulnerability are well established, readily demonstrated with low attrition rates and more clinically relevant compared to most mouse models [17]. Although several rat models have emerged over the years to evaluate addiction-relevant traits such as High vs. Low Novelty Seekers and High vs. Low Impulsive Rats [18, 19], none are as ideal a tool for studying addiction genetics as inbred Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats (SHR). There is a sizeable literature on drug self-administration in SHR. We have extensively characterized cocaine self-administration in male SHR/NCrl [20–24]. Across studies, we demonstrated that male SHR/NCrl acquired cocaine self-administration faster, exhibited escalated cocaine intake across a range of doses; displayed greater reinforcing strength and motivation for cocaine, and were more reactive to cocaine cues compared to inbred Wistar Kyoto (WKY/NCrl) and outbred Wistar controls. Besides cocaine, male SHR/NCrl self-administered greater amounts of heroin [25] as well as d-amphetamine [26] and methylphenidate [27] compared to WKY/NCrl and/or Wistar. Additionally, male and female SHR/NCrl consumed more ethanol than Sprague-Dawley control rats [28]. These distinct behavioral phenotypes in SHR/NCrl capture several of the salient hallmarks of a substance use disorder outlined in DSM-V [29].

To justify the use of the RCC approach in SHR substrains, it is necessary to first demonstrate a behavioral difference between two closely related substrains. There are at least 8 closely related SHR substrains from different international sources, but none have been directly compared for addiction-relevant traits. In this report, we phenotyped two substrains – SHR/NCrl (Charles River Laboratories) and SHR/NHsd (Harlan Sprague-Dawley). SHR breeding history began in 1963 at Kyoto University when the outbred Wistar stock in Kyoto (WKY) was selectively bred for elevated blood pressure [30]. Incompletely inbred F13 SHR rats were transferred to the NIH in 1966. SHR rats at NIH were subsequently fully inbred by 1969 and then distributed from NIH (SHR/N) to Charles River Labs (SHR/NCrl) in 1973 at F32 and to Harlan (SHR/NHsd), but with the date of transfer and filial generation at transfer not publicized. Critically, male SHR/NHsd did not self-administer greater amounts of d-amphetamine and methylphenidate [31, 32], and female SHR/NHsd did not self-administer greater amounts of low-dose nicotine than WKY/NHsd, Wistar, and/or Sprague-Dawley controls [33]. The only exception to these distinct substrain profiles is that male and female SHR/NHsd did self-administer greater amount of high-dose nicotine compared to WKY/NHsd controls [33, 34]. In summary, a preponderance of circumstantial evidence predicts that SHR/NCrl are likely to exhibit a distinct behavioral profile as it relates to drugs of abuse compared to SHR/NHsd; however, to our knowledge, these substrains have yet to be compared directly at the behavioral level.

Whole genome sequencing studies demonstrated that SHR/NCrl and SHR/NHsd are closely related (<0.5% genetic variation) and exhibit comparable elevated blood pressure at ~ 7 weeks of age [35]. SHR/NCrl and SHR/NHsd are viewed as distinct substrains based on analyses from a 10K DNA microarray showing 2.22% heterozygous single nucleotide polymorphisms in SHR/NHsd vs. 0.02% to 0.17% heterozygous single nucleotide polymorphisms in SHR from Charles River Laboratories and the other international sources [36]. Such genetic divergence in SHR/NCrl vs. SHR/NHsd could cause substrain differences in behavior. Thus, in the present study, we directly compared SHR/NCrl and SHR/NHsd substrains on several model traits for cocaine addiction risk. The phenotypic differences that we report in this study will be exploited to advance our future goal of applying an RCC approach in SHR substrains to identify the genetic basis of variability in cocaine addiction-relevant traits.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals

Ten male SHR/NCrl (8 weeks old on arrival; 150-225 g; Charles River Laboratories, USA) and ten male SHR/NHsd (8 weeks old on arrival; 175-250 g; ENVIGO, USA) were housed individually in ventilated cages under a 12hr light/dark cycle (08:00hr on; 20:00hr off) in a climate-controlled vivarium. Individual housing was used in order not to undermine primary phenotypes under study - drug reward and inhibitory control capacity. Past research demonstrated that group-housing, a form of environmental enrichment, reduced drug reward and improved a variety of executive functions in colony-reared SHR [37–40]. In addition, our past phenotyping studies in SHR/NCrl that involved measures of cocaine self-administration and inhibitory control used single housing, as group-housing has been shown to impede cocaine self-administration [21–24,41]. During food-motivated procedures for impulsive-like and compulsive-like behavior, rats were maintained at 80-85% of their expected free-feeding body weight by restricting food in their home cages and providing free access to water. Food restriction is necessary for reliable performances in the tasks used to measure impulsive-like and compulsive-like behavior [41,42]. During the remaining procedures, rats had unlimited access to food and water in their home cages. All procedures complied with the 8th edition of the NIH Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Boston University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

2.2. Apparatus

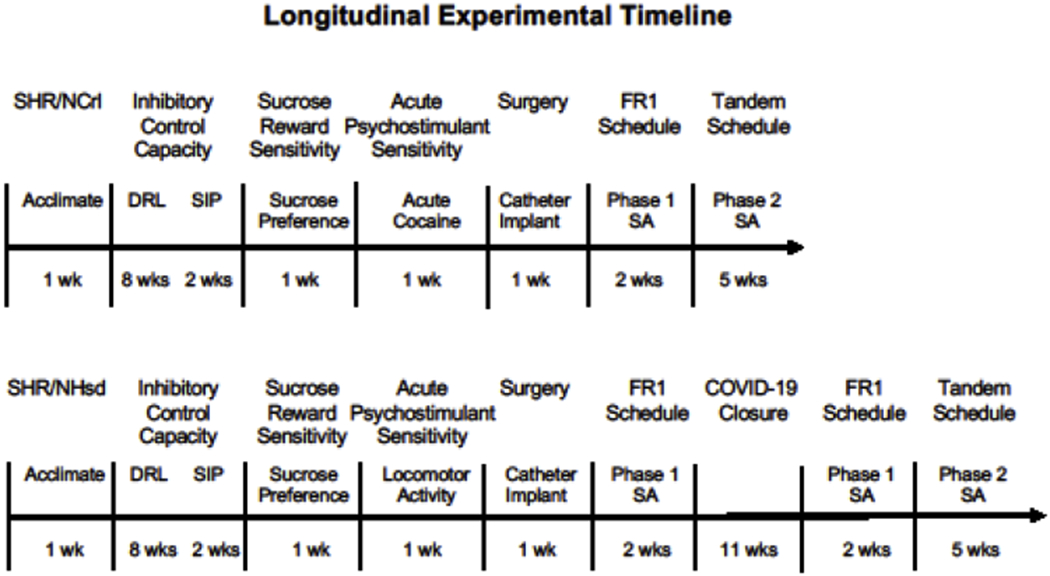

Operant conditioning chambers (model ENV-008CT; Med Associates, St. Albans, VT, USA) were used for tasks that measured impulsive-like and compulsive-like traits and cocaine self-administration behavior. Each operant chamber was outfitted with two retractable levers, two white stimulus lights, a house light, a speaker, a pellet dispenser, and a syringe pump that were arranged as previously described [43]. Sucrose preference was measured in the rat’s home cage and locomotor activity following acute cocaine administration was measured in boxes containing 15 infrared photobeam detectors (model ENV-3013, Med Associates, St Albans VT, USA). The operant chambers and the locomotor activity boxes were enclosed in sound attenuating cubicles with an exhaust fan. A timeline of all procedures is illustrated in Fig 1.

Figure 1.

Longitudinal experimental timeline for behavioral phenotyping in adult SHR/NCrl and SHR/NHsd male rats.

2.3. Procedures

2.3.1. Drugs

Cocaine hydrochloride was obtained from the National Institute on Drug Abuse Drug Supply (Bethesda, MD, USA). For acute intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections (1 ml/kg), cocaine (15 and 20 mg/kg) was dissolved in sterile saline. For chronic intravenous (i.v.) delivery, rats self-administered 0.25 mg/kg cocaine (1.35 mg/ml infused at 1.8 ml/min for 0.6 s/100 g body weight). This is considered a moderate i.v. dose of cocaine, based on its relative position on the descending limb of the fixed-ratio 1 dose-response curve and its relative position on the ascending limb of the progressive-ratio breakpoint dose-response curve in SHR/NCrl, WKY/NCrl and Wistar rats [20, 21, 23].

2.3.2. Catheter Surgery and Maintenance

Prior to initiating drug self-administration sessions, rats were implanted with a catheter made from silicon rubber tubing (Dow Silicones Corporation, Midland, MI, USA; inner diameter, 0.51 mm, outer diameter, 0.94 mm) into the right jugular vein as previously described [43]. Catheters were maintained daily (Monday - Thursday) with 0.1 ml of a saline locking solution containing 100 mg/ml cefazolin (WG Critical Care, LLC, Paramus, NJ, USA) and 30 IU/ml heparin (SAGENT Pharmaceuticals, Schaumburg, IL, USA). Over weekends and holidays, rats received 0.05 ml of a glycerol locking solution containing 3 parts glycerol (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) to 1 part of the saline locking solution to fill the catheter dead space. Prior to the next behavioral session, the glycerol locking solution was removed and replaced with 0.1 ml of saline containing 3 IU/ml heparin. Catheters were checked daily for leaks and tested periodically for patency by infusing 0.1 ml of a 10 mg/ml solution of methohexital sodium (Brevital; PAR Pharmaceuticals, Chestnut Ridge, NY, USA). Rats received at least 7 days of post-surgical recovery before beginning self-administration sessions.

2.3.3. Impulsive-Like Behavior

Differential reinforcement of low-rate responding (DRL) procedures were implemented to measure impulsive-like behavior in SHR/NCrl (n=10) and SHR/NHsd (N=10) substrains, as previously described [41]. Briefly, rats first were trained to press the right and left levers under a fixed-ratio (FR) 1 schedule until they reliably obtained 100 food pellets (45 mg chocolate-flavored; Bio-Serv, Frenchtown, NJ, USA) in less than 30 min (typically reached within 2-3 days of training). Rats were then required during daily (Monday - Friday) 55-min sessions to press a randomly assigned active lever (right or left, counterbalanced across rats) under a DRL 5s schedule with an adjusting limited hold (10s maximum) for a minimum of 10 sessions and until stable responding was reached (<20% change in inter-response-time (IRT) at the 5s wait time for three consecutive sessions). An incremental training protocol was used to progress rats to the DRL 30s schedule that also continued for a minimum of 10 sessions and until stable responding was reached at the 30s wait time for three consecutive sessions. Under DRL 5s and 30s contingencies, responses on the active lever greater than 5s or 30s apart, respectively, were reinforced by 45 mg food pellets, while premature responses reset the 5s or 30s timer. Inactive lever responses were recorded but had no programmed consequences. DRL procedures were conducted in darkened chambers. Measures of impulsive action under DRL responding included response efficiency (percentage of reinforced responses) and burst responding (percentage of active lever responses with IRTs less than 2s apart), which were averaged over the last 3 sessions of stable responding in individual rats under the DRL 5s and DRL 30s schedules.

2.3.4. Compulsive-Like Behavior

Following completion of the DRL procedures, schedule-induced polydipsia (SIP) procedures were implemented to measure compulsive-like behavior in SHR/NCrl (n=10) and SHR/NHsd (N=10) substrains as previously described [42]. Briefly, the left lever was retracted and the right lever was replaced by a panel accommodating a 100 ml graduated cylinder with 1-ml volumetric markings. The 3-inch ballpoint sipper tube with a 1-inch bend (Ancare Corp., Bellmore, NY, USA) protruded 3.6 cm into the chamber. Before each session, rats were weighed and the graduated cylinders filled with fresh tap water. After attaching the graduated cylinder to clips on the outside of the panel, the initial water level was recorded to the nearest ml. During 60-min daily sessions (Monday – Friday), 45 mg food pellets were delivered noncontingently under a fixed time (FT) 60s schedule. When each session ended, rats were removed immediately from the chamber and the final water level was recorded to the nearest ml and is reported as ml/kg body weight. Rats underwent 12 SIP sessions conducted in chambers illuminated by the house light.

2.3.5. Sensitivity to Sucrose Reward

Following completion of the SIP procedure, rats returned to ad libitum feeding for 1 week and then sucrose preference testing was implemented to measure sensitivity to a non-drug reward in SHR/NCrl (n=10) and SHR/NHsd (N=10) substrains as previously described [44]. Briefly, testing was conducted in the rat’s home cage in the animal facility over a 4-day period. On day 1, each rat was provided with two water bottles located on the sides of the central food hopper to habituate rats to drinking from 2 bottles for 23hr. On day 2, one bottle was randomly switched to contain 0.8% sucrose solution midway through the light cycle (12:00hr) to habituate rats to the novel sucrose solution for 23hr. On day 3, the bottles were reversed to avoid perseveration effects and sucrose preference was measured after 23hr. On day 4, the 0.8% sucrose solution bottle was replaced with water, and water preference was measured for 23hr before the two bottles were removed from the cage. The ml/kg consumed from each bottle were recorded on each habituation and test day. Sucrose preference was calculated by dividing the ml/kg sucrose consumed by the total ml/kg sucrose + water consumed on day 3. Water preference was calculated similarly by dividing the ml/kg water consumed from the left bottle by the total ml/kg water consumed from the left and right bottles on day 4. Reactivity to sucrose reward was measured by comparing total fluid intake during the water and sucrose preference tests.

2.3.6. Sensitivity to the Acute Psychostimulant Effects of Cocaine

Following the sucrose preference test, we assessed locomotor activity before and after a cocaine challenge to determine sensitivity to the acute psychostimulant effects of cocaine in SHR/NCrl (n=10) and SHR/NHsd (N=10) substrains. On day 1, rats were placed into the apparatus for a 30-min habituation period, which also served to measure the locomotor response to a novel environment. Then rats received an ip injection of sterile 0.9% saline (1 ml/kg) and were returned to the apparatus for 1hr. On days 2 and 3, the procedure was identical except that rats received an ip injection of 15 mg/kg and 20 mg/kg cocaine, respectively. Locomotor activity counts (3-consecutive photobeam breaks) were recorded each day in 5-min bins for the habituation and test phases of each session.

2.3.7. Cocaine Self-Administration

Catheters were surgically implanted as described in section 2.3.2. Procedures adapted from [45] were used to measure cocaine self-administration behavior in SHR/NCrl (n=6) and SHR/NHsd (n=10) substrains under fixed-ratio and tandem schedules. Based on experimental necessity, we reassigned 4 rats in the SHR/NCrl cohort to become yoked-saline controls in a different study after assessing DRL, SIP, sucrose reward and acute locomotor effects of cocaine. As SHR/NCrl have a very pronounced phenotype for elevated cocaine self-administration under a variety of experimental conditions [20–24], sufficient power remained to observe substrain differences with a group size of n=6 SHR/NCrl.

Fixed-Ratio Schedule.

During daily sessions (Monday – Friday), rats were randomly assigned a taking lever (counterbalanced left or right across rats) and each press on this lever (FR1) produced a cocaine infusion (0.25 mg/kg) followed by its retraction. The house light then extinguished and the stimulus light above the taking lever was illuminated for the duration of a 20s timeout (TO) period. After the TO, the taking lever was reinserted into the chamber and the house light was re-illuminated. Individual sessions ended after 30 drug infusions or 2hr, whichever occurred first. Rats received a minimum of 10 taking sessions and until responses were stable for three sessions (range 10-11 sessions). The number of taking responses, averaged over the last 3 sessions of stable responding in individual rats, was used to evaluate cocaine taking behavior.

Tandem Schedule.

A tandem schedule then was used and each cycle of the seek-take chain started with insertion of the seeking lever, with the taking lever retracted. The first lever press on the seeking lever (FR1) initiated a random interval (RI) schedule and the first lever press made after the RI elapsed retracted the seeking lever and inserted the taking lever. The schedule on the seeking lever was increased from RI 2s to RI 120s over 5 to 10 sessions while the schedule on the taking lever remained at FR1 with a 20s TO after the drug infusion. The post-infusion TO then increased from 20s to 600s over the next 5 to 10 sessions. At the terminal schedule, rats were responding under a tandem schedule denoted FR1, RI 120s; FR1, 600s TO. Individual sessions ended after 11 seek-take cycles were completed or 2hr, whichever occurred first. Rats continued with seek-take sessions at the terminal schedule until seeking lever responses were stable for three sessions (range 4-17 sessions at the terminal schedule). The number of seeking responses and number of cycles completed, averaged over the last 3 sessions of stable responding in individual rats, were used to evaluate cocaine seeking and taking under the tandem schedule. At the end of behavioral testing, rats were euthanized by an overdose of sodium pentobarbital.

2.4. Statistical Analyses

Measures of impulsive-like behavior (DRL), compulsive-like behavior (SIP), and sensitivity to sucrose reward (sucrose preference) were analyzed by 2-tailed t-tests for independent samples to compare performances in SHR/NCrl and SHR/NHsd. SIP also was analyzed by 2-factor (substrain X session number) repeated measure analysis of variance (RM ANOVA) to compare the development of polydipsia in SHR/NCrl and SHR/NHsd over the 12 sessions. To evaluate reactivity to sucrose reward in SHR/NCrl and SHR/NHsd, total fluid intake during water and sucrose preference tests was analyzed by 2-factor (substrain X preference test type) RM ANOVA. Locomotor activity in 5-min bins over the 30-min habituation sessions and the 1-hr drug sessions was analyzed by 3-factor (substrain X day/dose X bin) RM ANOVA to measure the time course of basal locomotor activity and the acute psychomotor stimulant effects of cocaine in SHR/NCrl and SHR/NHsd. For drug self-administration data, measures were analyzed by 2-tailed t-tests for independent samples to determine substrain differences in cocaine taking, cocaine seeking, and cocaine seek-take cycles completed. Post-hoc Tukey tests were used following significant ANOVA factors in the above analyses.

The 2-tailed Pearson correlation statistic was used to analyze the associations between selected dependent measures that best characterized the model traits of interest for cocaine addiction risk: DRL 30s and DRL 5s response efficiency (impulsive-like behavior), SIP terminal water consumption (compulsive-like behavior), sucrose preference (sensitivity to sucrose reward), total fluid intake during the sucrose preference test (reactivity to sucrose reward), locomotor responses on habituation day 1 (response to novelty), initial 10 min of locomotor responses after 20 mg/kg cocaine (sensitivity to acute cocaine), and cocaine taking, cocaine seeking, and cocaine seek-take cycles completed (cocaine self-administration). The equation α’ = 1 – (1 – overall-α )1/k was used to correct for multiple comparisons in the correlation matrix [46]. Based on this equation, probability values <0.031 were considered significant in this study. Narrow-sense heritability (h2) was estimated by calculating the total variance, then calculating the average within-strain variance between the two strains (environmental variance), and then subtracting the environmental variance from the total variance which yielded the between-strain variance (genetic). Genetic variance was then divided by the total phenotypic variance which yielded the heritability estimate of the particular trait [47,48].

3. Results

3.1. Impulsive-Like Behavior

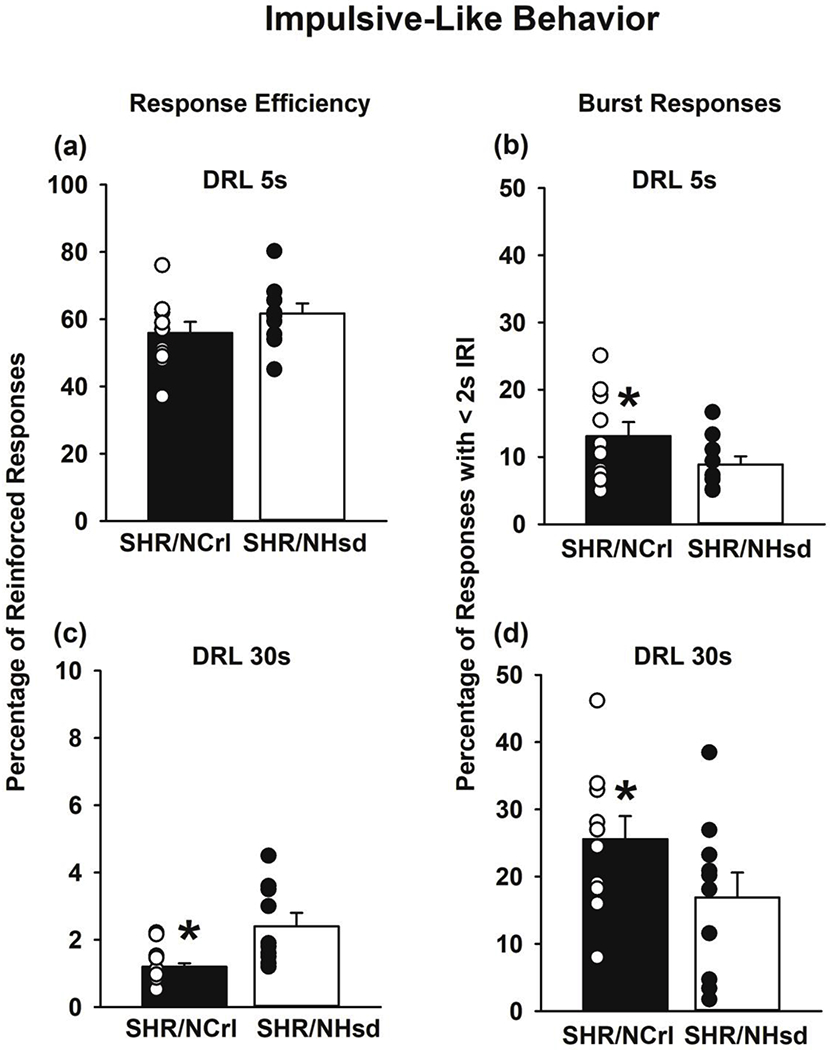

Under the DRL 5s schedule, response efficiency was similar but burst responding was greater (p<0.05) in SHR/NCrl compared to SHR/NHsd (Figs 2a and 2b). Under the DRL 30s schedule, SHR/NCrl exhibited lower response efficiency (p<0.01) and greater burst responding (p<0.05) than SHR/NHsd (Figs 2c and 2d). The total number of active lever responses under the DRL 30s schedule was greater in SHR/NCrl than SHR/NHsd (375±15 vs. 289±16, respectively; p<0.001), whereas under the DRL 5s schedule the total number of active lever responses did not differ significantly between SHR/NCrl and SHR/NHsd (525±36 vs. 457±30, respectively). Thus, under the DRL 30s schedule for which greater inhibitory control was required, responding was relatively more premature and nonproductive in SHR/NCrl, providing evidence for increased impulsive action.

Figure 2.

Differential reinforcement of low-rate (DRL) performances in SHR/NCrl (n=10) and SHR/NHsd (n=10) male rats. Values are the mean ± s.e.m. and individual rat data points for the percentage of reinforced responses (response efficacy) and percentage of responses with IRTs < 2s (burst responding) averaged over the last 3 daily sessions at criteria for the DRL 5s wait time (panels a and b) and the DRL 30s wait time (panels c and d). *ps<0.05 comparing SHR/NCrl to SHR/NHsd.

3.2. Compulsive-Like Behavior

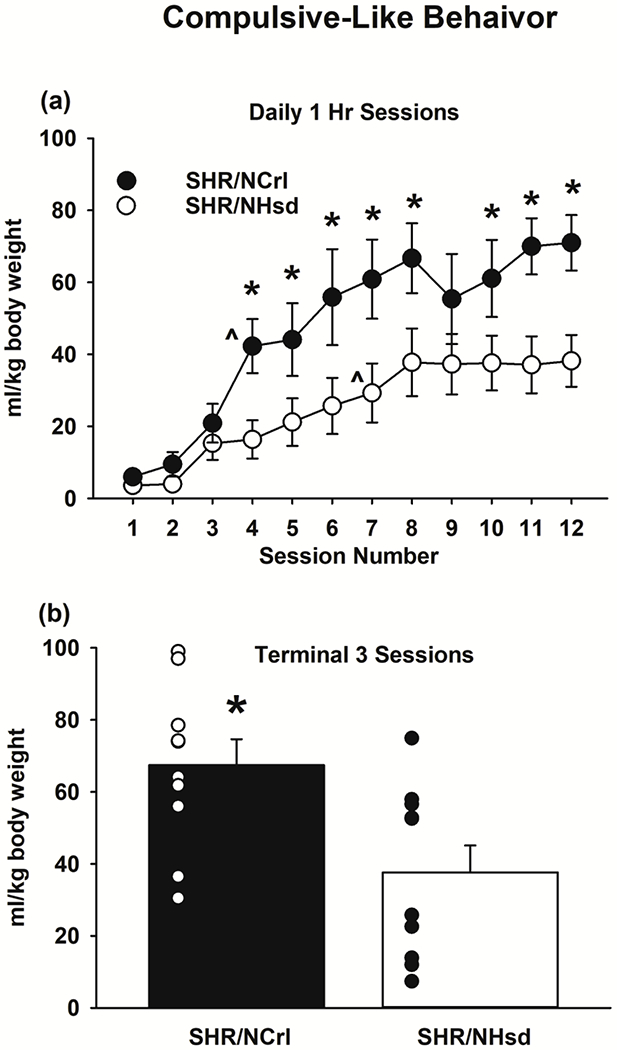

SHR substrains consumed similar amounts of water at the beginning of the SIP task, but SHR/NCrl developed polydipsia faster and to a greater extent than SHR/NHsd. Across the 12 sessions (Fig 3a), the substrain X session number interaction was significant (F[11,198]=2.5, p<0.01). Relative to session 1, water consumption increased beginning on session 4 in SHR/NCrl (ps<0.001), but not until session 7 in SHR/NHsd (ps<0.02). Relative to SHR/NHsd, water consumption was greater in SHR/NCrl on sessions 4-8 and 10-12 (ps<0.05). For the terminal three sessions (Fig 3b), there were robust substrain differences between SHR/NCrl and SHR/NHsd (p<0.01). Thus, consummatory behavior in the SIP task was relatively more habitual and excessive in SHR/NCrl, providing evidence for increased compulsive-like behavior.

Figure 3.

Schedule-induced polydipsia (SIP) in SHR/NCrl (n=10) and SHR/NHsd (n=10) male rats. Values are the mean ± s.e.m. ml/kg water intake for each of the 12 daily sessions (panel a) or the mean ± s.e.m. and individual rat data points for ml/kg water intake averaged over the terminal 3 daily sessions (panel b). * ps<0.05 comparing ml/kg water intake between SHR/NCrl and SHR/NHsd on sessions 4-8, 10-12, and the terminal 3 sessions combined. ^ ps<0.02 relative to session 1.

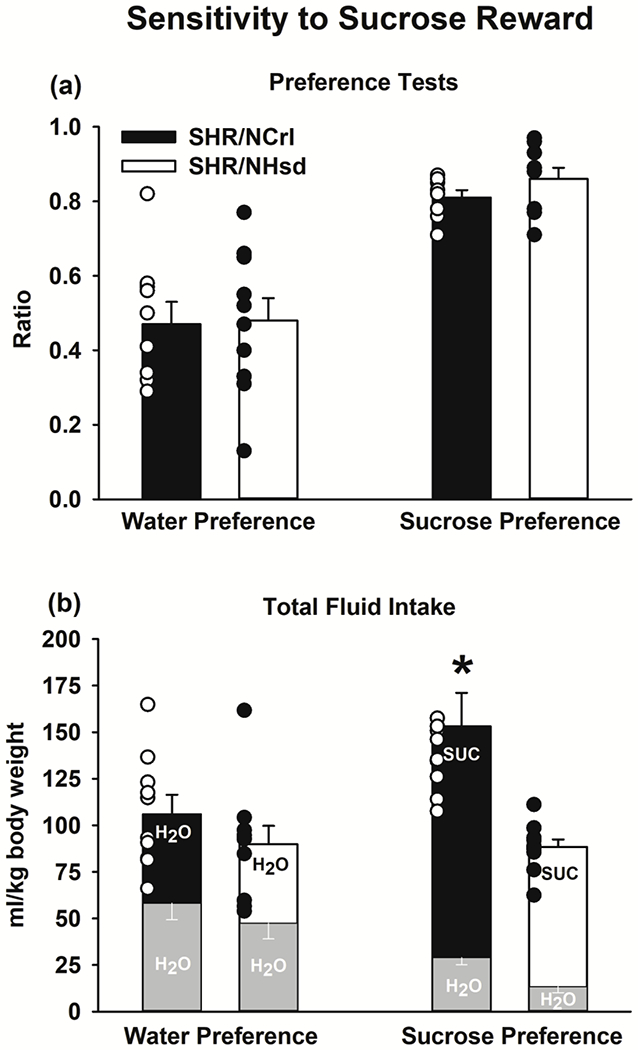

3.3. Sensitivity to Sucrose Reward

The preference ratios for water and sucrose were not significantly different between SHR/NCrl and SHR/NHsd (Fig 4a). Each substrain consumed approximately 50% of their daily fluid intake from each water bottle during the water preference test and approximately 80% of their daily fluid intake from the sucrose bottle during the sucrose preference test. Thus, sensitivity to sucrose reward did not differ between substrains. In contrast, total fluid intake depended on substrain and preference test type (F[1,18]=5.8, p<0.03). Whereas there were no significant substrain differences in total fluid intake during the water preference test, SHR/NCrl had greater total fluid intake than SHR/NHsd during the sucrose preference test (p<0.001; Fig 4b). Moreover, total fluid intake in SHR/NCrl was greater during the sucrose preference than the water preference test (p<0.004), whereas total fluid intake in SHR/NHsd was statistically similar during the water and sucrose preference tests. Thus, SHR/NCrl were relatively more reactive to sucrose reward.

Figure 4.

Sucrose preference testing in SHR/NCrl (n=10) and SHR/NHsd (n=10) male rats. Values are the mean ± s.e.m. and individual rat data points for the water and sucrose preference ratios (panel a) and the total ml/kg fluid intake during the water and sucrose preference tests (panel b). * ps<0.004 comparing total intake in SHR/NCrl to SHR/NHsd during the sucrose preference test and comparing total intake during the sucrose preference test to the water preference test in SHR/NCrl.

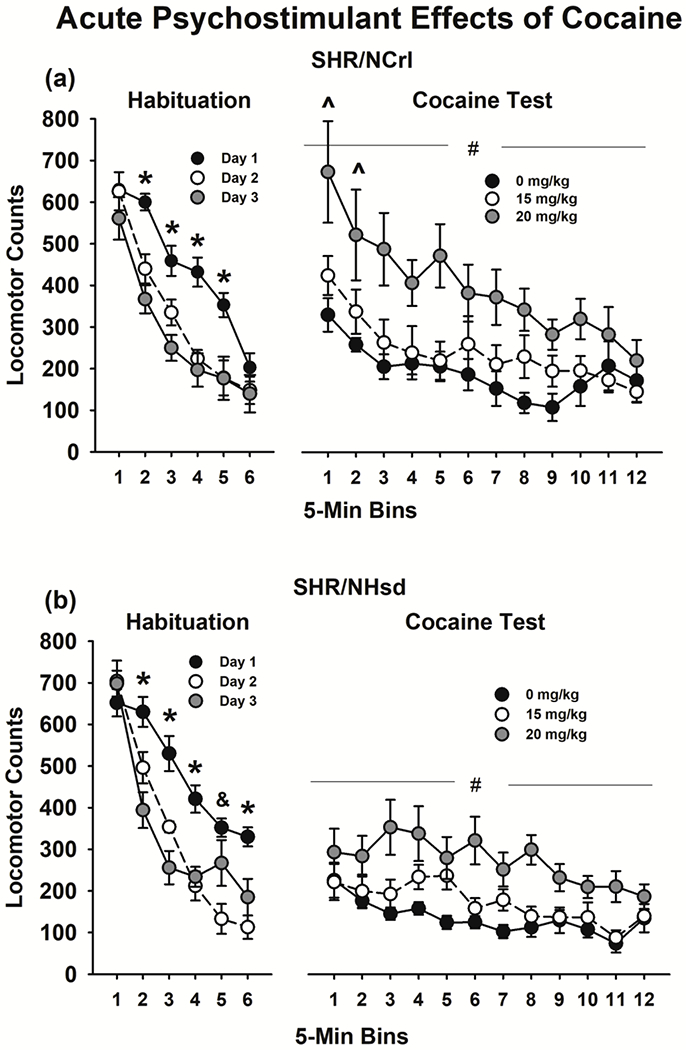

3.4. Sensitivity to the Acute Psychostimulant Effects of Cocaine

During habituation sessions, locomotor activity did not differ significantly between the substrains, but analyses revealed a significant habituation day X bin interaction (F[10,180]=7.5, p<0.001). Within SHR/NCrl (Fig 5a, left), locomotor activity was greater on habituation day 1 than days 2 and 3 for bins 2-5 (ps<0.03). Within SHR/NHsd (Fig 5b, left), locomotor activity was greater on habituation day 1 than days 2 and 3 for bins 2-4 and 6 (ps<0.01), and on habituation day 1 than day 2 for bin 5 (p<0.001). Thus, there was an overall heightened reaction to the novel environment on habituation day 1, with the response to novelty similar in SHR/NCrl and SHR/NHsd. Basal locomotor activity levels were similar as well between substrains over habituation sessions 1-3.

Figure 5.

Psychostimulant effects of acute cocaine in SHR/NCrl (n=10) and SHR/NHsd (n=10) male rats. Values are the mean ± s.e.m. locomotor activity counts in 5 min bins over the 30-min habituation sessions and the 1-hr cocaine tests in SHR/NCrl (panel a) and SHR/NHsd (panel b). * ps<0.03 comparing habituation day 1 to days 2 and 3 for bins 2-5 in SHR/NCrl and for bins 2-4 and 6 in SHR/NHsd. & p<0.001 comparing habituation day 1 to day 2 for bin 5 in SHR/NHsd. # p<0.01 comparing 20 mg/kg to 0 mg/kg and 15 mg/kg cocaine in both substrains ^ ps<0.04 comparing bins 1 and 2 in SHR/NCrl to SHR/NHsd after 20 mg/kg cocaine.

Following acute injections (Fig 5a and 5b, right), cocaine produced dose-dependent increases in locomotor activity (F[2,36]=19.2, p<0.001). There was greater locomotor activity after 20 mg/kg compared to 0 and 15 mg/kg cocaine within SHR/NCrl and SHR/NHsd (ps<0.01). Analysis of the bin X substrain interaction (F[11,198]=3.7, p<0.001) revealed that locomotor activity was greater in SHR/NCrl than SHR/NHsd for the first two 5-min bins of the session after 20 mg/kg cocaine (ps<0.04) but not after 0 or 15 mg/kg cocaine. Thus, SHR/NCrl were relatively more sensitive to the acute psychostimulant effects of 20 mg/kg cocaine.

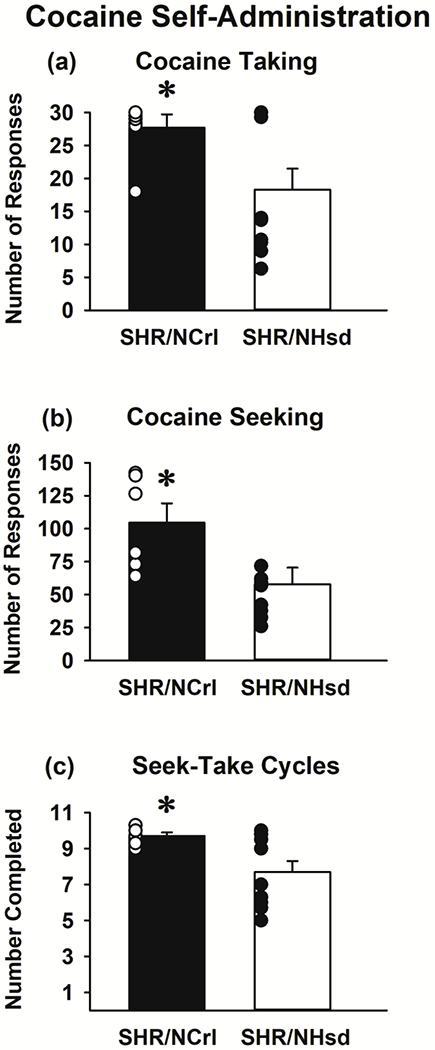

3.5. Cocaine Self-Administration

During initial self-administration training under the FR1 taking schedule (Fig 6a) SHR/NCrl self-administered more cocaine than SHR/NHsd (p<0.05). It should be noted that FR1 training in SHR/NHsd was interrupted between late March and early June 2020 due to a local quarantine related to the COVID-19 pandemic (Fig 1). Rats had just competed the FR1 training phase when the lab was shuttered. At that time, the catheters were filled with the glycerol locking solution, and after its removal in early June, we found that only 1 rat had a nonfunctional catheter that required repair before resuming sessions to repeat the entire FR1 training phase. There were no statistical differences between the initial FR1 baseline (19.5±2.7) and the new FR1 baseline (18.3±3.2) in SHR/NHsd (p<0.49). Thus, the unavoidable interruption in cocaine self-administration during FR1 training did not influence lever responding in SHR/NHsd over the long-term. After transition to the more demanding FR1, RI 120s; FR1, 600s TO tandem schedule, SHR/NCrl emitted more cocaine seeking responses (p<0.03) and completed more of the 11 seek-take cycles (p<0.03) compared to SHR/NHsd (Figs 6b and 6c). Thus, SHR/NCrl exhibited relatively greater cocaine self-administration.

Figure 6.

Cocaine self-administration in SHR/NCrl (n=6) and SHR/NHsd (n=10) male rats. Values are the mean ± s.e.m. and individual rat data points for the number of taking lever responses under the FR1 schedule (panel a) and for the number of seeking lever responses (panel b) and seek-take cycles completed (panel c) under the tandem FR1, RI 120s; FR1, 600s TO schedule of cocaine (0.25 mg/kg/infusion) delivery. * ps<0.05 comparing SHR/NCrl to SHR/NHsd.

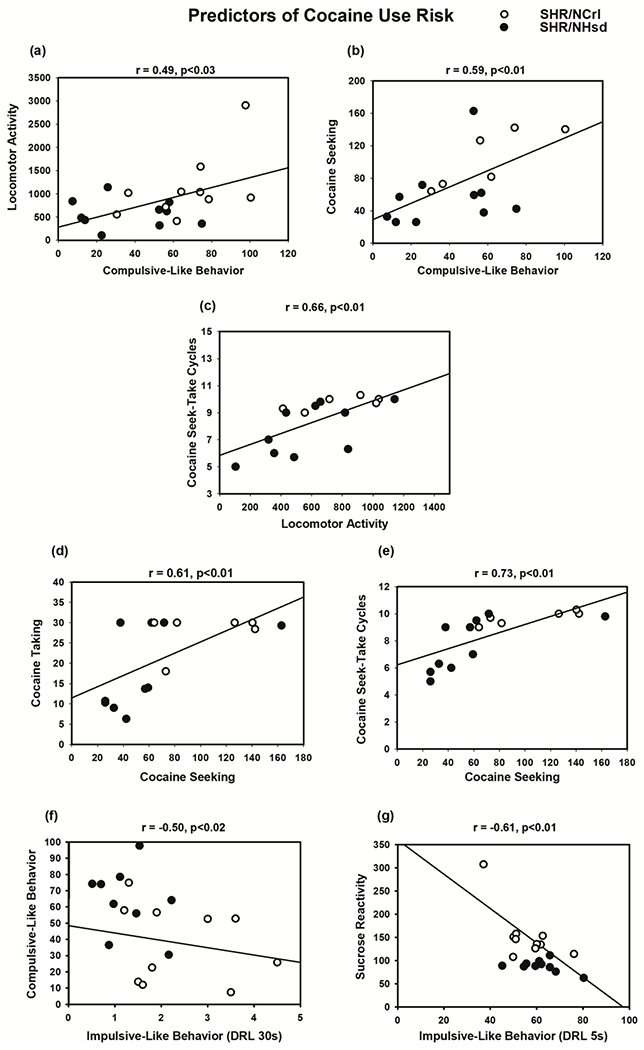

3.6. Predictors of Cocaine Use and Heritability Analyses

Interestingly, the compulsive-like behavior exhibited by SHR/NCrl and SHR/NHsd was the best predictor of the acute psychostimulant effects of 20 mg/kg cocaine (Fig 7a) and of cocaine seeking during chronic cocaine self-administration (Fig 7b). Moreover, locomotor activity after acute injection of 20 mg/kg cocaine predicted the number of cocaine seek-take cycles completed (Fig 7c). Cocaine taking behavior under both self-administration schedules predicted the magnitude of cocaine seeking (Fig 7d and 7e). Lower DRL 30s response efficiency (greater impulsive-like behavior) was associated with greater compulsive-like behavior (Fig 7f), while lower DRL 5s response efficiency (greater impulsive-like behavior) was associated with greater sucrose reactivity (Fig 7g). Sucrose preference and locomotor response to novelty did not significantly correlate with any behavioral measure evaluated (Table 1).

Figure 7.

Model traits predictive of cocaine use risk in SHR/NCrl (white circles) and SHR/NHsd (black circles). Illustrated are behaviors that significantly correlated with compulsive-like behavior (panels a and b), with cocaine-induced locomotor activity (panel c), with cocaine seeking responses (panels d and e), and with impulsive-like behavior (panels f and g).

Table 1.

Correlation matrix between dependent measures in SHR/NCrl and SHR/NHsd substrains. Vertical cell contents: correlation coefficient, 2-tailed p value, and number of observations. Significant correlations are highlighted in gray, after correction for multiple comparisons.

| Response Efficiency DRL 30s | SIP | Sucrose Preference | Sucrose Reactivity | Novelty Response | Cocaine Locomotion | Cocaine Taking | Cocaine Seeking | Cocaine Cycles | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Response Efficiency DRL 5s | −0.079 | −0.062 | 0.157 | −0.607 | −0.083 | 0.034 | −0.112 | −0.294 | −0.165 |

| 0.741 | 0.794 | 0.508 | 0.005 | 0.729 | 0.886 | 0.680 | 0.269 | 0.542 | |

| 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 16 | 16 | 16 | |

| Response Efficiency DRL 30s SIP | −0.502 | 0.053 | −0.195 | 0.380 | −0.136 | −0.101 | −0.176 | −0.169 | |

| 0.024 | 0.826 | 0.409 | 0.099 | 0.568 | 0.710 | 0.515 | 0.532 | ||

| 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 16 | 16 | 16 | ||

| SIP | −0.080 | 0.143 | −0.227 | 0.489 | 0.455 | 0.591 | 0.430 | ||

| 0.739 | 0.548 | 0.336 | 0.029 | 0.077 | 0.016 | 0.097 | |||

| 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 16 | 16 | 16 | |||

| Sucrose Preference | −0.319 | 0.046 | −0.170 | 0.138 | −0.130 | 0.116 | |||

| 0.170 | 0.846 | 0.474 | 0.611 | 0.632 | 0.670 | ||||

| 20 | 20 | 20 | 16 | 16 | 16 | ||||

| Sucrose Reactivity | −0.060 | 0.225 | 0.261 | 0.161 | 0.200 | ||||

| 0.803 | 0.340 | 0.328 | 0.552 | 0.457 | |||||

| 20 | 20 | 16 | 16 | 16 | |||||

| Novelty Response | −0.252 | −0.119 | 0.178 | −0.101 | |||||

| 0.283 | 0.661 | 0.510 | 0.711 | ||||||

| 20 | 16 | 16 | 16 | ||||||

| Cocaine Locomotion | 0.497 | 0.433 | 0.659 | ||||||

| 0.050 | 0.094 | 0.006 | |||||||

| 16 | 16 | 16 | |||||||

| Cocaine Taking | 0.636 | 0.862 | |||||||

| 0.008 | 0.00002 | ||||||||

| 16 | 16 | ||||||||

| Cocaine Seeking | 0.728 | ||||||||

| 0.001 | |||||||||

| 16 |

Narrow-sense heritability estimates (h2) were used to determine the percentage of total phenotypic variance explained by additive genetic factors. After estimating heritability based on parental SHR substrain variance, the most heritable phenotype was the number of cocaine seek-take cycles completed (h2 = 40%). Other phenotypes showing similar h2 estimates were cocaine taking responses (h2 = 31%) and reactivity to sucrose reward (h2 = 38%). The heritability estimates for DRL 30s impulsive-like behavior (h2 = 27%) and SIP compulsive-like behavior (h2 = 27%) were lower and were comparable to the heritability estimates for cocaine seeking responses (h2 = 26%). The lowest heritability estimates were for the acute psychostimulant effects of 20 mg/kg cocaine (h2 = 16% at the 10-min time point and h2 = 22% at the 5-min time point), locomotor response to novelty (h2 = 7%), sucrose preference (h2 = 5%), and DRL 5s impulsive-like behavior (h2 = 4%).

4. Discussion

4.1. Inhibitory Control Capacity as a Model Trait for Cocaine Addiction Risk

Lever responding during the DRL task was more premature and nonproductive in SHR/NCrl than SHR/NHsd, especially for the longer 30s wait time. Lower response efficiency and higher burst responding indicate greater impulsive action [41]. Increased impulsive-like behavior in SHR/NCrl compared to SHR/NHsd is not surprising, given the historical differences in the between-strain comparisons of behavior during DRL and other tasks of impulsive action or choice. Collectively, studies showed that SHR/NCrl were consistently more impulsive-like than both inbred (WKY/NCrl) and outbred (Wistar and Long-Evans but not Sprague-Dawley) control strains [41,42,49–54]. In contrast, SHR/NHsd were more impulsive-like on these tasks compared to one or the other type of control strain, but never compared to both inbred (WKY/NHsd) and outbred (Wistar and Sprague-Dawley) control strains [55–58].

SHR/NCrl were more compulsive-like than SHR/NHsd in the SIP task in that water intake was more habitual and excessive in SHR/NCrl. By the end of testing, SHR/NCrl consumed ~65 ml/kg of water and SHR/NHsd consumed ~40 ml/kg of water in 1hr. Considering that average 24hr water intake in each substrain is ~80 ml/kg [59,60], the excessive drinking that developed in 1hr was clearly maladaptive and exceeded the physiological need for water even after consuming 2.7 grams of food during the 1hr test sessions. Individual differences in the development of SIP are considered a means to identify a compulsive-like endophenotype reflecting poor inhibitory control [61]. To date, SIP has been investigated only in SHR/NCrl for between-strain comparisons, and results consistently showed that polydipsia associated with a FT 60s schedule of food pellet delivery was greater in SHR/NCrl than WKY/NCrl and Wistar control strains [42,52].

The results of DRL and SIP testing indicate that inhibitory control capacity as a model trait for cocaine addiction risk is more limited in SHR/NCrl than SHR/NHsd. We chose a priori to use the DRL and SIP tasks to study these different facets of inhibitory control because these tasks are conducted under non-overlapping test conditions and have unique requirements, including chamber illumination (dark vs lit, respectively), lever availability (inserted vs. retracted, respectively), basis for food pellet delivery (contingent vs. automatic, respectively), and the behavioral variable assessed (reinforced lever responses vs. ml/kg water intake, respectively). The significant correlation between impulsive-like and compulsive-like behaviors in this study likely reflects the relationship between the two inhibitory control endophenotypes rather a direct influence of low levels of reinforced lever responses in the DRL task on excessive fluid consumption in the SIP task. Supporting this assertion was the lack of a significant correlation between low levels of reinforced lever responses in the DRL task and excessive fluid consumption during the sucrose preference test. Heritability estimates indicate that 27% of the variances for impulsive-like and compulsive-like behaviors can be explained by additive genetic factors. Similar results were reported in a recent twin study showing that inhibitory control traits were heritable, with 33% of the variance for impulsive-like behavior and 25% of the variance for compulsive-like behavior explained by additive genetic factors [62]. Of relevance, high levels of impulsivity and compulsivity were found to be risk factors for cocaine dependence in both human laboratory studies [63–65] and rat experiments [18,66,67]. In the current study, compulsive-like behavior was a significant predictor of cocaine seeking responses and initial sensitivity to the acute psychostimulant effects of 20 mg/kg cocaine.

4.2. Reactions to Sucrose, Novelty and Acute Cocaine

Preference for sweet solutions is a measure of sensitivity to a non-drug reward [68]. Sucrose preference did not differ between SHR substrains and heritability was low (5%). Sucrose preference also did not significantly correlate with any cocaine use phenotype that we evaluated, consistent with past research showing that sucrose preference was not correlated with cocaine intake [69]. In contrast, sucrose + water intake during sucrose preference testing (reactivity to sucrose reward) was greater in SHR/NCrl than SHR/NHsd. Past research showed that Sprague-Dawley rats selectively bred for high saccharin intake acquired cocaine self-administration faster and maintained cocaine intake at higher levels compared to Sprague-Dawley rats selectively bred for low saccharin intake [70, 71]. It has been suggested that relatively greater reactivity to sweet solutions in selectively bred rats is a strong indicator of a genetic predisposition for vulnerability to cocaine abuse [72]. The heritability estimate for the sucrose reactivity phenotype indicates that 38% of the variance can be explained by additive genetic factors. This facet of behavior in the SHR substrains might be translational because cocaine-dependent individuals show higher sucrose liking scores than controls [73].

The locomotor response to a novel environment (habituation day 1) did not differ between the SHR substrains, and in support, the estimated heritability was low (7%). Nor did this phenotype significantly correlate with any cocaine use phenotype that we evaluated. This finding is consistent with past research showing that the locomotor response to a novel environment in high and low locomotor responding Sprague-Dawley rats did not predict cocaine intake [19,74]. Likewise, basal locomotor activity (habituation days 1-3) was comparable in SHR/NCrl and SHR/NHsd. This finding also is consistent with between-strain comparisons showing that SHR/NCrl and SHR/NHsd are similarly hyperactive relative to WKY/NCrl and WKY/NHsd controls, respectively [42,55]. In contrast, novelty preference can predict severity of compulsive cocaine use in high and low novelty preferring Sprague-Dawley rats [19], suggesting that novelty preference might be an important phenotype to study in future investigations exploring SHR substrain differences. Previous between-strain comparisons support such efforts, as SHR/NCrl exhibited greater novelty preference than WKY/NCrl and Wistar [26,75], but novelty preference did not differ significantly between SHR/NHsd, WKY/NHsd and Wistar [31].

The locomotor response to acute 20 mg/kg cocaine was greater in SHR/NCrl than SHR/NHsd for the first 10-min after the injection. This phenotype significantly predicted the number of cocaine seek-take cycles completed under the tandem schedule of cocaine self-administration. In a recent study that compared eight inbred mouse strains, the locomotor response to acute 20 mg/kg cocaine depended on strain, with the magnitude of cocaine-induced locomotor activity predictive of cocaine intake and motivation for cocaine self-administration [76]. A study in recombinant inbred mice indicated that 28% to 37% of the variance for locomotor sensitivity to acute cocaine (10-40 mg/kg) can be explained by additive genetic factors [77]. In SHR rat substrains, the heritability estimate was lower and at best, ranged from 22% at 5 min post-cocaine (time point when SHR substrain differences were the greatest) and 16% at 10 min post-cocaine. Notably, initial response to cocaine can be predictive of future cocaine dependence in people [78], supporting our current observation that although not as heritable, cocaine locomotor activity has some predictive value for future cocaine intake. We previously mapped and validated Hnrnph1 as a quantitative trait gene for methamphetamine-induced locomotor activity and subsequently extended these findings to methamphetamine reward and reinforcement [79–81], providing evidence for at least some portion of shared genetic basis between stimulant-induced locomotor activity and stimulant-induced appetitive behaviors.

4.3. Cocaine Self-Administration

SHR/NCrl self-administered more cocaine than SHR/NHsd under the FR1 schedule and also emitted more cocaine seeking responses and completed more cocaine seek-take cycles under the tandem schedule. Heritability estimates indicated that 26% - 40% of the variances for our cocaine use traits can be explained by additive genetic factors, a key finding because cocaine use disorders in people are heritable on the order of 40% - 70% [82,83]. As discussed in section 4.2, four of our model traits for cocaine addiction risk (impulsive- and compulsive-like behavior, reactivity to sucrose reward and initial sensitivity to acute 20 mg/kg cocaine) showed substrain differences, with 22% - 38% of their phenotypic variances explained by additive genetic factors. Heritability’s of 20% or greater provide sufficient genetic variance to conduct genetic mapping in experimental crosses [84].

Of the model traits for cocaine addiction risk we evaluated in SHR/NCrl and SHR/NHsd, compulsive-like behavior and initial sensitivity to acute 20 mg/kg cocaine were the best predictors of cocaine seeking and cocaine taking behaviors, respectively. It was somewhat surprising that impulsive-like behavior was not a significant predictor of any aspect of cocaine self-administration behavior in this study, given its prominent association with cocaine self-administration in outbred Lister Hooded rats [18,66,85,86] and outbred Wistar rats [87,88]. Although both inhibitory control traits were heritable and were correlated in SHR/NCrl and SHR/NHsd, the compulsive-like behavioral phenotype might be relatively more important for predicting cocaine self-administration in an F2 population of rats that segregate SHR/NCrl and SHR/NHsd alleles. Interestingly, the balance between brain circuits that promote (ventral striatum-orbitofrontal cortex) and limit (ventral striatum-anterior cingulate cortex) compulsive behavior is dysregulated in cocaine users, with the degree of circuit dysregulation positively correlated with the number of DSM-IV compulsive drug use symptoms [89]. Strikingly similar brain-behavior relationships were reported in a subset of outbred Sprague-Dawley rats that progressed to compulsive stimulant use [90], highlighting a critical role for compulsive-like behavior, and perhaps genetic variation in prefrontal cortex and nucleus accumbens circuit function, in the development of cocaine addiction.

4.4. Limitations

This study has some limitations. First, only male rats were included in this feasibility study. Given our limited resources and the logistical difficulties in running a large sample size in a longitudinal deep phenotyping study within a truncated time frame, as a first step, we limited the evaluation to males in order to facilitate comparisons with previous studies which by and large, employed males-only. We fully acknowledge the importance of running both sexes and will employ both females and males in future replication studies with facility-bred parental substrains and in an F2 cross. Notably, Vendruscolo and colleagues [91,92] reported sex differences in comparisons between SHR/NCrl and inbred Lewis rats for ethanol consumption (female SHR/NCrl drank more ethanol than female Lewis rats across all concentrations whereas male SHR/NCrl drank more ethanol than male Lewis rats only at low concentrations) and for cocaine-induced sensitization (male SHR/NCrl showed greater sensitization than male Lewis rats but female SHR/NCrl did not differ from female Lewis rats), but not for saccharin reactivity (both male and female SHR/NCrl had increased total fluid intake induced by saccharin availability in free choice with water). The implications are that we are highly likely to map one or more QTLs in males whereas for females, we currently do not know – there could be no substrain differences and thus no QTLs; there could be more robust substrain differences and correspondingly more robust QTLs; or there could be substrain differences in the same direction or different direction and correspondingly different QTLs from the males. Second, the h2 heritability estimates are specific for the phenotypes we measured in parental SHR/NCrl and SHR/NHsd substrains. More precise estimates will be obtained in the F2 cross, including SNP h2 estimates. Lastly, compulsive cocaine use, defined as continued cocaine seeking despite aversive consequences, needs to be studied. This definitive clinical and preclinical measure of cocaine addiction will require much larger group sizes than what was used herein because resistance to punishment only occurs in a subset of rats (~25%) that receives extended cocaine self-administration training [45]. This specific phenotype can more easily be assessed in an F2 cross, as large sample sizes are required for identifying the multiple genes of small effect size that contribute to complex traits [11].

5. Conclusions

These results provide compelling support for using an RCC approach in SHR substrains to uncover candidate genes and variants that are of relevance to cocaine use disorders. The robust substrain differences in multiple model traits for cocaine addiction risk and cocaine self-administration behaviors support the heritability of these traits and increase the likelihood that a forward genetic mapping approach will be successful. The advantage of an RCC is that this type of cross segregates orders of magnitude fewer genetic variants, making an RCC a simple and powerful solution for rapid, high-confidence gene discovery for complex traits [11].

Highlights.

Closely related SHR substrains have distinct cocaine risk traits

Inhibitory control was poorer in SHR/NCrl than SHR/NHsd

SHR/NCrl were more sucrose reactive and sensitive to acute cocaine than SHR/NHsd

Cocaine use was greater in SHR/NCrl than SHR/NHsd

SHR substrains can be used in an RCC to uncover cocaine risk genes and variants

Funding

Supported by a pilot grant from the NIDA P30 Center of Excellence in Omics, Systems Genetics, and the Addictome of the University of Tennessee (P30 DA044223-03 Revised) and in part by NIH grants R21 DA045148 and U01 DA050243. All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of competing interest: none

References

- [1].Ho MK, Goldman D, Heinz A, Kaprio J, Kreek MJ, Li MD, Munafo MR, Tyndale RF, Breaking barriers in the genomics and pharmacogenetics of drug addiction, Clin Pharmacol Ther 88(6) (2010) 779–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Ducci F, Goldman D, The genetic basis of addictive disorders, Psychiatr Clin North Am 35(2) (2012) 495–519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2019, https://www.samhsa.gov/data/release/2019-national-survey-drug-use-and-health-nsduh-releases

- [4].Gelernter J, Sherva R, Koesterer R, Almasy L, Zhao H, Kranzler HR, Farrer L, Genome-wide association study of cocaine dependence and related traits: FAM53B identified as a risk gene, Mol Psychiatry 19(6) (2014) 717–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Dickson PE, Miller MM, Calton MA, Bubier JA, Cook MN, Goldowitz D, Chesler EJ, Mittleman G, Systems genetics of intravenous cocaine self-administration in the BXD recombinant inbred mouse panel, Psychopharmacology (Berl) 233(4) (2016) 701–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Lopez-Leon S, Gonzalez-Giraldo Y, Wegman-Ostrosky T, Forero DA, Molecular Genetics of Substance Use Disorders: An Umbrella Review, Neurosci Biobehav Rev (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Jensen KP, A Review of Genome-Wide Association Studies of Stimulant and Opioid Use Disorders, Mol Neuropsychiatry 2(1) (2016) 37–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Bryant CD, Zhang NN, Sokoloff G, Fanselow MS, Ennes HS, Palmer AA, McRoberts JA, Behavioral differences among C57BL/6 substrains: implications for transgenic and knockout studies, J Neurogenet 22(4) (2008) 315–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Bryant CD, The blessings and curses of C57BL/6 substrains in mouse genetic studies, Ann N Y Acad Sci 1245 (2011) 31–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Bryant CD, Ferris MT, De Villena FPM, Damaj MI, Kumar V, Mulligan MK, Reduced Complexity Cross Design for Behavioral Genetics, Molecular-Genetic and Statistical Techniques for Behavioral and Neural Research (2018) 165–190. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Bryant CD, Smith DJ, Kantak KM, Nowak TS, Williams RW, Damaj MI, Redei EE, Chen H, Mulligan MK, Facilitating Complex Trait Analysis via Reduced Complexity Crosses, Trends Genet 36(8) (2020) 549–562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Kumar V, Kim K, Joseph C, Kourrich S, Yoo SH, Huang HC, Vitaterna MH, de Villena FP, Churchill G, Bonci A, Takahashi JS, C57BL/6N mutation in cytoplasmic FMRP interacting protein 2 regulates cocaine response, Science 342(6165) (2013) 1508–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Kirkpatrick SL, Goldberg LR, Yazdani N, Babbs RK, Wu JY, Reed ER, Jenkins DF, Bolgioni AF, Landaverde KI, Luttik KP, Mitchell KS, Kumar V, Johnson WE, Mulligan MK, Cottone P, Bryant CD, Cytoplasmic FMR1-Interacting Protein 2 Is a Major Genetic Factor Underlying Binge Eating, Biol Psychiat 81(9) (2017) 757–769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Mulligan MK, Abreo T, Neuner SM, Parks C, Watkins CE, Houseal MT, Shapaker TM, Hook M, Tan HY, Wang XS, Ingels J, Peng JM, Lu L, Kaczorowski CC, Bryant CD, Homanics GE, Williams RW, Identification of a Functional Non-coding Variant in the GABA(A) Receptor alpha 2 Subunit of the C57BL/6J Mouse Reference Genome: Major Implications for Neuroscience Research, Front Genet 10 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Harkness JH, Shi X, Janowsky A, Phillips TJ, Trace Amine-Associated Receptor 1 Regulation of Methamphetamine Intake and Related Traits, Neuropsychopharmacology 40(9) (2015) 2175–2184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Reed C, Baba H, Zhu Z, Erk J, Mootz JR, Varra NM, Williams RW, Phillips TJ, A Spontaneous Mutation in Taar1 Impacts Methamphetamine-Related Traits Exclusively in DBA/2 Mice from a Single Vendor, Front Pharmacol 8 (2017) 993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Parker CC, Chen H, Flagel SB, Geurts AM, Richards JB, Robinson TE, Solberg Woods LC, Palmer AA, Rats are the smart choice: Rationale for a renewed focus on rats in behavioral genetics, Neuropharmacology 76 Pt B (2014) 250–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Belin D, Mar AC, Dalley JW, Robbins TW, Everitt BJ, High impulsivity predicts the switch to compulsive cocaine-taking, Science 320(5881) (2008) 1352–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Belin D, Berson N, Balado E, Piazza PV, Deroche-Gamonet V, High-novelty-preference rats are predisposed to compulsive cocaine self-administration, Neuropsychopharmacology 36(3) (2011) 569–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Harvey RC, Sen S, Deaciuc A, Dwoskin LP, Kantak KM, Methylphenidate treatment in adolescent rats with an attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder phenotype: cocaine addiction vulnerability and dopamine transporter function, Neuropsychopharmacology 36(4) (2011) 837–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Somkuwar SS, Jordan CJ, Kantak KM, Dwoskin LP, Adolescent atomoxetine treatment in a rodent model of ADHD: effects on cocaine self-administration and dopamine transporters in frontostriatal regions, Neuropsychopharmacology 38(13) (2013) 2588–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Jordan CJ, Harvey RC, Baskin BB, Dwoskin LP, Kantak KM, Cocaine-seeking behavior in a genetic model of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder following adolescent methylphenidate or atomoxetine treatments, Drug Alcohol Depend 140 (2014) 25–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Jordan CJ, Lemay C, Dwoskin LP, Kantak KM, Adolescent d-amphetamine treatment in a rodent model of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: impact on cocaine abuse vulnerability in adulthood, Psychopharmacology (Berl) 233(23-24) (2016) 3891–3903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Jordan CJ, Taylor DM, Dwoskin LP, Kantak KM, Adolescent D-amphetamine treatment in a rodent model of ADHD: Pro-cognitive effects in adolescence without an impact on cocaine cue reactivity in adulthood, Behav Brain Res 297 (2016) 165–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Miller ML, Ren Y, Szutorisz H, Warren NA, Tessereau C, Egervari G, Mlodnicka A, Kapoor M, Chaarani B, Morris CV, Schumann G, Garavan H, Goate AM, Bannon MJ, Consortium I, Halperin JM, Hurd YL, Ventral striatal regulation of CREM mediates impulsive action and drug addiction vulnerability, Mol Psychiatry 23(5) (2018) 1328–1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].dela Pena I, de la Pena JB, Kim BN, Han DH, Noh M, Cheong JH, Gene expression profiling in the striatum of amphetamine-treated spontaneously hypertensive rats which showed amphetamine conditioned place preference and self-administration, Arch Pharm Res 38(5) (2015) 865–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].dela Pena IC, Ahn HS, Choi JY, Shin CY, Ryu JH, Cheong JH, Methylphenidate self-administration and conditioned place preference in an animal model of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: the spontaneously hypertensive rat, Behav Pharmacol 22(1) (2011) 31–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Berger DF, Lombardo JP, Peck JA, Faraone SV, Middleton FA, Youngetob SL, The effects of strain and prenatal nicotine exposure on ethanol consumption by adolescent male and female rats, Behav Brain Res 210(2) (2010) 147–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Doris PA, Genetics of hypertension: an assessment of progress in the spontaneously hypertensive rat, Physiol Genomics 49(11) (2017) 601–617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Meyer AC, Rahman S, Charnigo RJ, Dwoskin LP, Crabbe JC, Bardo MT, Genetics of novelty seeking, amphetamine self-administration and reinstatement using inbred rats, Genes Brain Behav 9(7) (2010) 790–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Marusich JA, McCuddy WT, Beckmann JS, Gipson CD, Bardo MT, Strain differences in self-administration of methylphenidate and sucrose pellets in a rat model of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, Behav Pharmacol 22(8) (2011) 794–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Han W, Wang T, Chen H, Social learning promotes nicotine self-administration by facilitating the extinction of conditioned aversion in isogenic strains of rats, Sci Rep 7(1) (2017) 8052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Chen H, Hiler KA, Tolley EA, Matta SG, Sharp BM, Genetic factors control nicotine self-administration in isogenic adolescent rat strains, Plos One 7(8) (2012) e44234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Hermsen R, de Ligt J, Spee W, Blokzijl F, Schafer S, Adami E, Boymans S, Flink S, van Boxtel R, van der Weide RH, Aitman T, Hubner N, Simonis M, Tabakoff B, Guryev V, Cuppen E, Genomic landscape of rat strain and substrain variation, BMC Genomics 16 (2015) 357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Zhang-James Y, Middleton FA, Faraone SV, Genetic architecture of Wistar-Kyoto rat and spontaneously hypertensive rat substrains from different sources, Physiol Genomics 45(13) (2013) 528–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Botanas CJ, Lee H, de la Pena JB, Dela Pena IJ, Woo T, Kim HJ, Han DH, Kim BN, Cheong JH, Rearing in an enriched environment attenuated hyperactivity and inattention in the Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats, an animal model of Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, Physiol Behav 155 (2016) 30–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].de Carvalho CR, Pandolfo P, Pamplona FA, Takahashi RN, Environmental enrichment reduces the impact of novelty and motivational properties of ethanol in spontaneously hypertensive rats, Behav Brain Res 208(1) (2010) 231–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Pamplona FA, Pandolfo P, Savoldi R, Prediger RD, Takahashi RN, Environmental enrichment improves cognitive deficits in Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats (SHR): relevance for Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 33(7) (2009) 1153–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Santos CM, Peres FF, Diana MC, Justi V, Suiama MA, Santana MG, Abilio VC, Peripubertal exposure to environmental enrichment prevents schizophrenia-like behaviors in the SHR strain animal model, Schizophr Res 176(2-3) (2016) 552–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Somkuwar SS, Kantak KM, Bardo MT, Dwoskin LP, Adolescent methylphenidate treatment differentially alters adult impulsivity and hyperactivity in the Spontaneously Hypertensive Rat model of ADHD, Pharmacol Biochem Behav 141 (2016) 66–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Ibias J, Pellon R, Schedule-induced polydipsia in the spontaneously hypertensive rat and its relation to impulsive behaviour, Behav Brain Res 223(1) (2011) 58–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Szalay JJ, Morin ND, Kantak KM, Involvement of the dorsal subiculum and rostral basolateral amygdala in cocaine cue extinction learning in rats, Eur J Neurosci 33(7) (2011) 1299–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Slattery DA, Markou A, Cryan JF, Evaluation of reward processes in an animal model of depression, Psychopharmacology (Berl) 190(4) (2007) 555–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Pelloux Y, Everitt BJ, Dickinson A, Compulsive drug seeking by rats under punishment: effects of drug taking history, Psychopharmacology (Berl) 194(1) (2007) 127–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Curtin F, Schulz P, Multiple correlations and Bonferroni’s correction, Biol Psychiatry 44(8) (1998) 775–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Hegmann JP, Possidente B, Estimating genetic correlations from inbred strains, Behav Genet 11(2) (1981) 103–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Falconer DS, Mackay TFC. Introduction to Quantitative Genetics, 4th ed., Longman, Burnt Mill, England, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- [49].Bull E, Reavill C, Hagan JJ, Overend P, Jones DN, Evaluation of the spontaneously hypertensive rat as a model of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: acquisition and performance of the DRL-60s test, Behav Brain Res 109(1) (2000) 27–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Sanabria F, Killeen PR, Evidence for impulsivity in the Spontaneously Hypertensive Rat drawn from complementary response-withholding tasks, Behav Brain Funct 4 (2008) 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Orduna V, Valencia-Torres L, Bouzas A, DRL performance of spontaneously hypertensive rats: dissociation of timing and inhibition of responses, Behav Brain Res 201(1) (2009) 158–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Ibias J, Pellon R, Different relations between schedule-induced polydipsia and impulsive behaviour in the Spontaneously Hypertensive Rat and in high impulsive Wistar rats: questioning the role of impulsivity in adjunctive behaviour, Behav Brain Res 271 (2014) 184–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Orduna V, Impulsivity and sensitivity to amount and delay of reinforcement in an animal model of ADHD, Behav Brain Res 294 (2015) 62–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Aparicio CF, Hennigan PJ, Mulligan LJ, Alonso-Alvarez B, Spontaneously hypertensive (SHR) rats choose more impulsively than Wistar-Kyoto (WKY) rats on a delay discounting task, Behav Brain Res 364 (2019) 480–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].van den Bergh FS, Bloemarts E, Chan JS, Groenink L, Olivier B, Oosting RS, Spontaneously hypertensive rats do not predict symptoms of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, Pharmacol Biochem Behav 83(3) (2006) 380–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Ferguson SA, Paule MG, Cada A, Fogle CM, Gray EP, Berry KJ, Baseline behavior, but not sensitivity to stimulant drugs, differs among spontaneously hypertensive, Wistar-Kyoto, and Sprague-Dawley rat strains, Neurotoxicol Teratol 29(5) (2007) 547–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Wooters TE, Bardo MT, Methylphenidate and fluphenazine, but not amphetamine, differentially affect impulsive choice in spontaneously hypertensive, Wistar-Kyoto and Sprague-Dawley rats, Brain Res 1396 (2011) 45–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Bayless DW, Perez MC, Daniel JM, Comparison of the validity of the use of the spontaneously hypertensive rat as a model of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in males and females, Behav Brain Res 286 (2015) 85–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Charles River Laboratories, Techincal Bulletin #1 (Spring; 1999), https://www.criver.com/sites/default/files/resources/rm_rm_n_techbul_spring_99.pdf [Google Scholar]

- [60].Kraly FS, Coogan LA, Specht SM, Trattner MS, Zayfert C, Cohen A, Goldstein JA, Disordered drinking in developing spontaneously hypertensive rats, Am J Physiol 248(4 Pt 2) (1985) R464–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Moreno M, Flores P, Schedule-induced polydipsia as a model of compulsive behavior: neuropharmacological and neuroendocrine bases, Psychopharmacology (Berl) 219(2) (2012) 647–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Tiego J, Chamberlain SR, Harrison BJ, Dawson A, Albertella L, Youssef GJ, Fontenelle LF, Yucel M, Heritability of overlapping impulsivity and compulsivity dimensional phenotypes, Sci Rep 10(1) (2020) 14378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Moeller FG, Dougherty DM, Barratt ES, Schmitz JM, Swann AC, Grabowski J, The impact of impulsivity on cocaine use and retention in treatment, J Subst Abuse Treat 21(4) (2001) 193–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Ersche KD, Jones PS, Williams GB, Smith DG, Bullmore ET, Robbins TW, Distinctive personality traits and neural correlates associated with stimulant drug use versus familial risk of stimulant dependence, Biol Psychiatry 74(2) (2013) 137–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Ersche KD, Gillan CM, Jones PS, Williams GB, Ward LH, Luijten M, de Wit S, Sahakian BJ, Bullmore ET, Robbins TW, Carrots and sticks fail to change behavior in cocaine addiction, Science 352(6292) (2016) 1468–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Economidou D, Pelloux Y, Robbins TW, Dalley JW, Everitt BJ, High impulsivity predicts relapse to cocaine-seeking after punishment-induced abstinence, Biol Psychiatry 65(10) (2009) 851–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Dalley JW, Everitt BJ, Robbins TW, Impulsivity, compulsivity, and top-down cognitive control, Neuron 69(4) (2011) 680–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Scheggi S, De Montis MG, Gambarana C, Making Sense of Rodent Models of Anhedonia, Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 21(11) (2018) 1049–1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Lynch WJ, Taylor JR, Decreased motivation following cocaine self-administration under extended access conditions: effects of sex and ovarian hormones, Neuropsychopharmacology 30(5) (2005) 927–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Carroll ME, Morgan AD, Lynch WJ, Campbell UC, Dess NK, Intravenous cocaine and heroin self-administration in rats selectively bred for differential saccharin intake: phenotype and sex differences, Psychopharmacology (Berl) 161(3) (2002) 304–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Carroll ME, Anderson MM, Morgan AD, Regulation of intravenous cocaine self-administration in rats selectively bred for high (HiS) and low (LoS) saccharin intake, Psychopharmacology (Berl) 190(3) (2007) 331–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Perry JL, Morgan AD, Anker JJ, Dess NK, Carroll ME, Escalation of i.v. cocaine self-administration and reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior in rats bred for high and low saccharin intake, Psychopharmacology (Berl) 186(2) (2006) 235–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Janowsky DS, Pucilowski O, Buyinza M, Preference for higher sucrose concentrations in cocaine abusing-dependent patients, J Psychiatr Res 37(1) (2003) 35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Sutton MA, Karanian DA, Self DW, Factors that determine a propensity for cocaine-seeking behavior during abstinence in rats, Neuropsychopharmacology 22(6) (2000) 626–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Langen B, Dost R, Comparison of SHR, WKY and Wistar rats in different behavioural animal models: effect of dopamine D1 and alpha2 agonists, Atten Defic Hyperact Disord 3(1) (2011) 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Roberts AJ, Casal L, Huitron-Resendiz S, Thompson T, Tarantino LM, Intravenous cocaine self-administration in a panel of inbred mouse strains differing in acute locomotor sensitivity to cocaine, Psychopharmacology (Berl) 235(4) (2018) 1179–1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Phillips TJ, Huson MG, McKinnon CS, Localization of genes mediating acute and sensitized locomotor responses to cocaine in BXD/Ty recombinant inbred mice, J Neurosci 18(8) (1998) 3023–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Lambert NM, McLeod M, Schenk S, Subjective responses to initial experience with cocaine: an exploration of the incentive-sensitization theory of drug abuse, Addiction 101(5) (2006) 713–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Yazdani N, Parker CC, Shen Y, Reed ER, Guido MA, Kole LA, Kirkpatrick SL, Lim JE, Sokoloff G, Cheng R, Johnson WE, Palmer AA, Bryant CD, Hnrnph1 Is A Quantitative Trait Gene for Methamphetamine Sensitivity, PLoS Genet 11(12) (2015) e1005713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Ruan QT, Yazdani N, Blum BC, Beierle JA, Lin W, Coelho MA, Fultz EK, Healy AF, Shahin JR, Kandola AK, Luttik KP, Zheng K, Smith NJ, Cheung J, Mortazavi F, Apicco DJ, Ragu Varman D, Ramamoorthy S, Ash PEA, Rosene DL, Emili A, Wolozin B, Szumlinski KK, Bryant CD, A Mutation in Hnrnph1 That Decreases Methamphetamine-Induced Reinforcement, Reward, and Dopamine Release and Increases Synaptosomal hnRNP H and Mitochondrial Proteins, J Neurosci 40(1) (2020) 107–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Ruan QT, Yazdani N, Reed ER, Beierle JA, Peterson LP, Luttik KP, Szumlinski KK, Johnson WE, Ash PEA, Wolozin B, Bryant CD, 5’ UTR variants in the quantitative trait gene Hnrnph1 support reduced 5’ UTR usage and hnRNP H protein as a molecular mechanism underlying reduced methamphetamine sensitivity, Faseb J 34(7) (2020) 9223–9244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Bi J, Gelernter J, Sun J, Kranzler HR, Comparing the utility of homogeneous subtypes of cocaine use and related behaviors with DSM-IV cocaine dependence as traits for genetic association analysis, Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 165B(2) (2014) 148–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Sun J, Kranzler HR, Gelernter J, Bi J, A genome-wide association study of cocaine use disorder accounting for phenotypic heterogeneity and gene-environment interaction, J Psychiatry Neurosci 45(1) (2020) 34–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Yang J, Zhu J, Williams RW, Mapping the genetic architecture of complex traits in experimental populations, Bioinformatics 23(12) (2007) 1527–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Dalley JW, Fryer TD, Brichard L, Robinson ES, Theobald DE, Laane K, Pena Y, Murphy ER, Shah Y, Probst K, Abakumova I, Aigbirhio FI, Richards HK, Hong Y, Baron JC, Everitt BJ, Robbins TW, Nucleus accumbens D2/3 receptors predict trait impulsivity and cocaine reinforcement, Science 315(5816) (2007) 1267–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Molander AC, Mar A, Norbury A, Steventon S, Moreno M, Caprioli D, Theobald DE, Belin D, Everitt BJ, Robbins TW, Dalley JW, High impulsivity predicting vulnerability to cocaine addiction in rats: some relationship with novelty preference but not novelty reactivity, anxiety or stress, Psychopharmacology (Berl) 215(4) (2011) 721–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Perry JL, Nelson SE, Carroll ME, Impulsive choice as a predictor of acquisition of IV cocaine self- administration and reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior in male and female rats, Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 16(2) (2008) 165–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Anker JJ, Perry JL, Gliddon LA, Carroll ME, Impulsivity predicts the escalation of cocaine self-administration in rats, Pharmacol Biochem Behav 93(3) (2009) 343–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Hu Y, Salmeron BJ, Gu H, Stein EA, Yang Y, Impaired functional connectivity within and between frontostriatal circuits and its association with compulsive drug use and trait impulsivity in cocaine addiction, JAMA Psychiatry 72(6) (2015) 584–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Hu Y, Salmeron BJ, Krasnova IN, Gu H, Lu H, Bonci A, Cadet JL, Stein EA, Yang Y, Compulsive drug use is associated with imbalance of orbitofrontal- and prelimbic-striatal circuits in punishment-resistant individuals, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 116(18) (2019) 9066–9071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Vendruscolo LF, Terenina-Rigaldie E, Raba F, Ramos A, Takahashi RN, Mormede P, Evidence for a female-specific effect of a chromosome 4 locus on anxiety-related behaviors and ethanol drinking in rats, Genes Brain Behav 5(6) (2006) 441–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Vendruscolo LF, Vendruscolo JC, Terenina E, Ramos A, Takahashi RN, Mormede P, Marker-assisted dissection of genetic influences on motor and neuroendocrine sensitization to cocaine in rats, Genes Brain Behav 8(3) (2009) 267–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]