Abstract

Objectives:

The aim of this study was to examine potential racial/ethnic disparities in community integration for the 2 yrs after burn injury.

Design:

A sample of 1773 adults with burn injury from the Burn Model Systems database was used with data on community integration collected at discharge (preinjury recall), 6, 12, and 24 mos after discharge.

Methods:

Four sets of hierarchal linear models determined the most appropriate model for understanding racial/ethnic differences in Community Integration Questionnaire trajectories over time.

Results:

Data indicated a decrease in community integration between discharge and 6 mos, a slight increase between 6 mos and 1 yr, and then a plateau between 1 and 2 yrs. White individuals had higher community integration score trajectories over time than black (b = 0.53, P < 0.001) and Hispanic (b = 0.58, P < 0.001) individuals, and community integration scores were similar between black and Hispanic individuals (b = −0.05, P = 0.788). These racial/ethnic disparities remained after accounting for age, sex, total burned surface area, number of days in rehabilitation, and active range of motion deficits.

Conclusions:

Additional rehabilitation resources should be targeted to helping black and Hispanic individuals integrate back into their communities after burn injury.

Keywords: Burn Injury, Racial/Ethnic Disparities, Community Integration

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) data suggest that fire and fatal burn injury accounted for more than 3000 deaths and nearly 400,000 nonfatal burn injuries in the United States in 2017.1 Although these numbers are stark, nonwhite, non-Asian individuals bare a disproportion burden of sustaining a burn injury.1–3 Fagenholz et al.4 found that black individuals presented more frequently to the emergency department with burn injuries (3.4 per 1000) as compared with white individuals (2.1 per 1000), and both groups presented more frequently than Hispanic individuals (1.6 per 1000), although the authors did not make direct statistical comparisons between Hispanic, black, or white individuals. There is also a higher risk for burn injury associated with lower-income populations,5 which may explain some of the racial/ethnic disparity in burn prevalence. A 2011 review by Peck6 concluded that consistent risk factors for burn injury are both race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status. Based on the data, the author suggested higher levels of substance and alcohol abuse, along with the lack of adequate smoke detection and alarms, were important factors for burn-related injuries and deaths within lower-income neighborhoods.

In addition to prevalence rates, research has also explored disparities in burn injury outcomes. Women have been shown to have higher odds of mortality after burn compared with men,7 although other research has shown no sex differences in outcomes among postoperative burn injury patients.8 Individuals from lower-income backgrounds are more likely to experience graft loss after burn injury,9 and white individuals with burn have been shown to be 10 times more likely than racial/ethnic minority individuals to return to work within 12 mos after burn injury.10 Racial/ethnic minority groups also have a higher risk of comorbid medical conditions, such as acute respiratory distress syndrome, pneumonia, septicemia, or urinary tract infections, compared with white patients with burn; in particular, black patients in this study had the highest risk among racial/ethnic minority groups.11 Black men with burn have also been shown to have higher odds of mortality, despite age, total burn surface area (TBSA) burned, and insurance type.12

One of the most important outcomes after burn is community integration, a person’s capability to be involved in their expected community role in both leisure and productive activities.13 Burn rehabilitation programs include social and occupational components, as both mechanisms are heavily related to overall well-being.14 For example, returning to work after a burn injury is associated with fewer posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and better health-related quality of life.15 Research concluded that individuals with burn injuries experience barriers to community integration because of burn (eg, skin-graft, respiratory issues) and nonburn (eg, social functioning) factors.13 Racial/ethnic disparities in community integration after burn may exist, but no research has investigated this topic, despite the growing research on disparities in burn rates and outcomes.

In the context of traumatic brain injury (TBI), Sander et al.16 found that black and Hispanic individuals reported lower overall community integration compared with whites and reported less productive activity; similar effects were also found for individuals from low-income backgrounds. In particular, black and Hispanic participants reported lower home integration compared with whites, but this relationship may be explained through shared familial responsibilities within racial/ethnic minority groups. Because many of the Hispanic participants had immediate family members residing in their country of origin, they reported living with close friends or roommates, which may influence task delegation, inadvertently promoting less integration and more task dependency. Although TBI and burn injury are different in important ways, these results suggest that disparities in community integration may exist in the context of burn as well.

Although there exists previous literature documenting racial/ethnic disparities in burn rates and outcomes, as well as racial/ethnic disparities in community integration in other injury populations such as TBI, the purpose of this study is to examine racial/ethnic disparities in community integration over the first 2 yrs after burn injury. This study also included important demographic covariates to determine whether they account for any racial/ethnic disparities observed in community integration. Based on the literature review, it was hypothesized that black and Hispanic individuals with burn would have lower levels of community integration over time that white individuals and that these disparities would persist even with the addition of demographic covariates.

METHODS

Participants and Procedure

The current study used data from the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research Burn Model Systems (BMS).17,18 The BMS program consists of a data center, four participating burn centers located in Boston, MA, Dallas, TX, Galveston, TX, and Seattle, WA, and two formerly participating centers located in Baltimore, MD, and Denver, CO. The BMS participants were identified by burn centers based on where burn treatment and rehabilitation occurred as well as aspects of individuals’ burn injuries.

Participants were eligible to participate in the BMS data enrollment if they were 18 yrs or older. Eligibility criteria also included receiving primary treatment from a BMS center for burn wound closure, having surgery for wound closure within 30 days of the burn injury, and being provided comprehensive rehabilitation services at the BMS center. In addition, patients were eligible to participate if they received burn surgery for electrical high-voltage/lightning burns, hand burns, face burns, and/or feet burns. Finally, all participants met one of the following subcriteria: (a) 20% or more TBSA if younger than 65 yrs with burn surgery for wound closure; or (b) 10% or more TBSA if age 65 yrs or older with burn surgery for wound closure. At each burn center, the institutional review board approved a protocol for obtaining patients’ institutional review board–approved written informed consent (or verbal if unable to write) during admission or discharge. The BMS data were collected at discharge (preinjury recall), as well as 6, 12, and 24 mos after discharge. For inclusion in the current study, participants must have been 18 yrs or older at the time of injury and have Community Integration Questionnaire (CIQ) data for at least one of the four time points of interest (discharge, 6, 12, or 24 mos).

For the current study, the BMS provided data collected on 4566 participants who were injured between 1994 and 2014. Data for 2793 participants were not used because race/ethnicity was missing, the race/ethnicity group was too small for analyses (eg, Native American [n = 34], Asian [n = 27], and multiracial [n = 15]), or if CIQ data for all time points were missing. Table 1 lists demographics and burn-related characteristics for the remaining 1773 participants who were included in the current study.

TABLE 1.

Summary of participant and burn characteristics

| Characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Participant | |

| Age, mean (SD) | 42.82 (15.19) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Women | 488 (27.5) |

| Men | 1285 (72.5) |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | |

| White, non-Hispanic | 1261 (71.1) |

| Mid-East and Ind | |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 307 (17.3) |

| Hispanic | 205 (11.6) |

| Burn, mean (SD) | |

| Total burned surface area | 19.28 (17.06) |

| Days in rehabilitation | 4.61 (20.33) |

| Active range of motion deficits | 1.81 (1.73) |

Measures

Community Integration

Level of community integration was measured using the CIQ, a 15-item scale originally developed for use with individuals with traumatic brain injuries to assess home integration, social integration, and productive activities. The CIQ has been validated for use with individuals with burn injuries.19 The BMS centers collected CIQ data at discharge (preinjury recall), 6, 12, and 24 mos using an abbreviated version of the full CIQ to measure participants’ level social integration (eg, leisure activities, visiting others, shopping) with overall summed scores ranging from 0 to 12 where higher scores indicate higher levels of integration. Overall, the CIQ-15 has acceptable psychometric properties for use with non-TBI samples (α = 0.63–0.78).20

Burn Characteristics

The BMS centers recorded data on burns including the number of days in rehabilitation indicated by the total number of days a patient spent in inpatient rehabilitation after the burn, TBSA representing the percentage of body covered by the burn, and if there was an active range of motion deficit due to the burn.

Demographics

Participants’ demographics were recorded by the BMS center in which they received treatment. This included their age in years, sex (male or female), and race/ethnicity. Race/ethnicity choices included the following: (a) white, non-Hispanic (including Middle-East and Indian), (b) black, non-Hispanic, (c) Hispanic, (d) Pacific Islander, (e) Asian, (f) Native American, (g) multiracial, (h) other, and (i) unknown.

Data Analyses

Analyses were conducted using SPSS Version 24.0. Significance was established at an α level of 0.05, two-tailed. Preliminary analyses were performed to check for the nature of missing data and normality (skewness and kurtosis). Four sets of hierarchal linear models (HLMs) were performed. The first set determined which curvature model most accurately reflected CIQ changes over time. The second set examined whether there were differences in CIQ scores over time between racial/ethnic groups. The third set examined the interaction terms between time and any statistically significant differences, if any, found in the second HLM, to determine whether racial/ethnic differences in CIQ occurred differentially as a function of time. The fourth HLM set included demographic characteristics including age, sex, total burned surface area, number of days in rehabilitation, and active range of motion deficits to attempt to account for the effects of those covariates on racial/ethnic differences in CIQ trajectories.

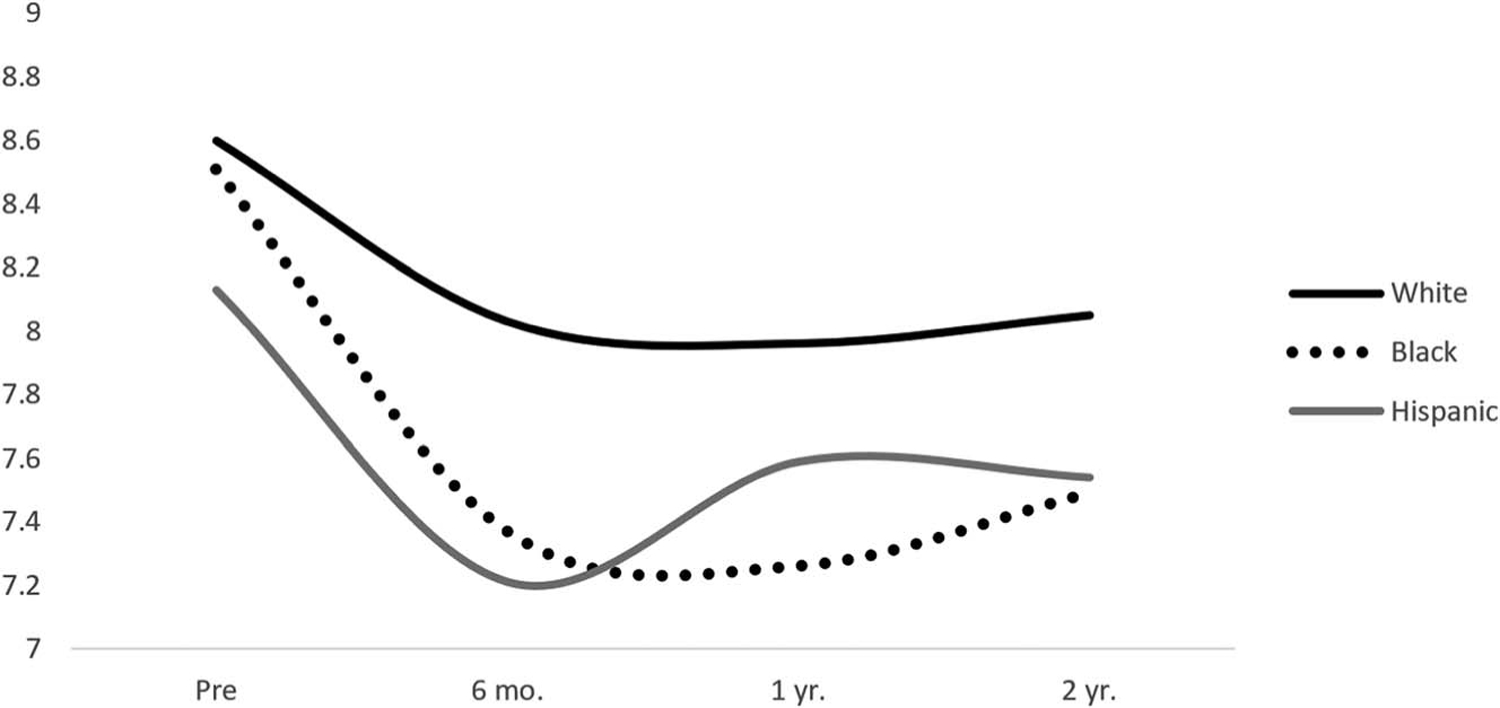

A series of independent-samples t tests or χ2 tests were performed to check for selection bias between included BMS participant data and those whose data were not included in the current analysis. Results indicated no significant difference between groups with regard to sex χ2(3, N = 4562) = 0.301, P = 0.583; age t(3737.73) = 1.753, P = 0.080, d = 0.057; and active range of motion deficits t(2963.50) = −0.337, P = 0.736, d = 0.012. Significant differences between the groups were observed with regard to number of days in rehabilitation t(2227.34) = −3.730, P < 0.001, d = 0.131, and TBSA t(3502.41) = −2.158, P = 0.031, d = 0.073, although the observed effects were small or very small, respectively. Of participants with data included, the percentages of missing CIQ values at discharge, 6, 12, and 24 mos were 46.8, 33.6, 40.0, and 49.2, respectively. Missing data in these participants were assessed using Little’s Missing Completely At Random test. Results of this test were nonsignificant (χ2 = 37.868, df = 28, P = 0.101) and indicated that the data were missing completely at random. Full information maximum likelihood estimation procedures were used without imputation to include participants with missing data. The CIQ data at each time point were observed to conform to a normal distribution with skewness values ranging between 0.43 and 0.67 and kurtosis values between 0.05 and 0.40, below the traditional cutoff of 1.00. Participants’ mean CIQ scores at discharge, 6, 12, and 24 mos are broken down by race/ethnicity appear in Table 2 and Figure 1.

TABLE 2.

Means and SDs of community integration scores by ethnicity

| Overall | White | Black | Hispanic | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CIQ | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD |

| Discharge | 8.52 ± 2.21 | 8.60 ± 2.22 | 8.51 ± 2.28 | 8.13 ± 2.07 |

| 6 mo | 7.82 ± 2.46 | 8.03 ± 2.42 | 7.37 ± 2.43 | 7.21 ± 2.55 |

| 1 yr | 7.79 ± 2.47 | 7.96 ± 2.51 | 7.26 ± 2.34 | 7.59 ± 2.29 |

| 2 yr | 7.90 ± 2.45 | 8.05 ± 2.43 | 7.49 ± 2.51 | 7.54 ± 2.40 |

FIGURE 1.

Community integration scores over time by race/ethnicity.

RESULTS

Analysis Set 1: Selecting Curvature Models

The first set of HLM analyses were conducted to determine which curvature model most accurately reflected CIQ changes across discharge, 6 mos, 1 yr, and 2 yrs after discharge. In all models, time was coded to reflect actual temporal spacing among data collections such that discharge = 0, 6 mos = 0.5, 1 yr = 1, and 2 yrs = 2. Unconditional growth (linear), quadratic, and cubic models were examined without predictors. Results indicated that a cubic or S-shaped trajectory of CIQ scores across discharge, 6 mos, 1 yr, and 2 yrs was the best fit (Table 3). This pattern conformed to a decrease in CI between discharge and 6 mos, a slight increase between 6 mos and 1 yr, and then a plateau between 1 and 2 yrs.

TABLE 3.

Trend analysis comparison

| Model | df | −2 Log Likelihood | Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linear | 4 | 18107.48 | — |

| Quadratic | 5 | 18050.22 | 57.26 |

| Cubic | 6 | 18033.76 | 16.46 |

Critical χ2 value for significant difference is ≥3.84 for df = 1 and ≥5.99 for df = 2 at α = 0.05 from the previous model.

Analysis Set 2: Examining Racial/Ethnic Differences

A second set of HLM analyses examined whether significant differences in CIQ scores over time were present between racial/ethnic groups. This was accomplished by creating orthogonal dummy codes (0 vs. 1) for Hispanic, black, and white racial/ethnic groups. In the first HLM, white and black CIQ scores were compared over time with race/ethnicity entered as a fixed effect; in the second HLM, white and Hispanic CIQ scores were compared; and in the third HLM, Hispanic and black CIQ scores were compared. In each of these three HLMs, only the participants from the two racial/ethnic groups being compared were included. Time, quadratic time, and cubic time were also included in the models as fixed effects.

These models indicated that white individuals had higher overall CIQ scores than black (b = 0.53, t[1518.10] = 4.01, P < 0.001) and Hispanic (b = 0.58, t[1353.02] = 3.72, P < 0.001) individuals. However, overall CIQ scores were similar between black and Hispanic (b = −.05, t[469.67] = −0.27, P = 0.788) individuals.

Analysis Set 3: Differential Effects of Race/Ethnicity Over Time

A third set of HLM analyses were performed for the racial/ethnic trajectory comparisons in the previous set that had been statistically significant. In these analyses, the race/ethnicity dummy code × cubic time interaction was added, in addition to the lower-order interaction terms (ie, linear and quadratic time), to see whether the previously significant racial/ethnic differences in CIQ scores changed differentially over time. These models suggested that CIQ differences did not vary significantly as a function of cubic time for black (b = 0.47, t[2435.52] = 0.90, P = 0.371) or Hispanic (b = 1.13, t[2271.39] = 1.96, P = 0.050) individuals when compared with white individuals.

Analysis Set 4: Accounting for Racial/Ethnic Differences

A fourth set of HLM analyses were performed for the racial/ethnic trajectory comparisons in the second set that had been statistically significant. In this set, the following demographic and injury characteristics were added as covariates to determine whether they accounted for the previously significant racial/ethnic differences in CIQ over time: age, sex, total burned surface area, number of days in rehabilitation, and active range of motion deficits. These models indicated that differences in CIQ scores between white individuals and black (b = 0.57, t[1172.67] = 3.44, P = 0.001) (Table 4) and Hispanic (b = 0.71, t[1055.51] = 4.09, P < 0.001) (Table 5) individuals remained significant even when demographic and injury characteristics were added as covariates.

TABLE 4.

The CIQ models comparing white and black participants including covariates

| 95% Confidence Interval | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | b | SE | df | t | P | Lower | Upper |

| Intercept | 8.198 | 0.206 | 1378.228 | 39.839 | 0.000 | 7.794 | 8.601 |

| Time | −2.829 | 0.436 | 1980.800 | −6.483 | 0.000 | −3.684 | −1.973 |

| Time × time | 2.754 | 0.653 | 1936.911 | 4.216 | 0.000 | 1.473 | 4.035 |

| Time × time × time | −0.758 | 0.227 | 1923.846 | −3.341 | 0.001 | −1.203 | −0.313 |

| White race | 0.571 | 0.166 | 1172.673 | 3.440 | 0.001 | 0.245 | 0.897 |

| Age | −0.026 | 0.004 | 1147.627 | −6.832 | 0.000 | −0.034 | −0.019 |

| TBSA | −0.004 | 0.004 | 1115.191 | −1.036 | 0.300 | −0.012 | 0.004 |

| Rehab days | −0.003 | 0.003 | 1001.871 | −1.010 | 0.313 | −0.009 | 0.003 |

| Sex | 0.127 | 0.135 | 1160.889 | 0.942 | 0.346 | −0.137 | 0.391 |

| Active range of motion deficits | −0.197 | 0.128 | 1182.349 | −1.545 | 0.123 | −0.447 | 0.053 |

TABLE 5.

The CIQ models comparing white and hispanic participants including covariates

| 95% Confidence Interval | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | b | SE | df | t | P | Lower | Upper |

| Intercept | 7.906 | 0.215 | 1247.580 | 36.844 | 0.000 | 7.485 | 8.327 |

| Time | −2.728 | 0.435 | 1984.606 | −6.272 | 0.000 | −3.581 | −1.875 |

| Time × time | 2.944 | 0.652 | 1947.081 | 4.518 | 0.000 | 1.666 | 4.222 |

| Time × time × time | −0.861 | 0.226 | 1935.939 | −3.803 | 0.000 | −1.305 | −0.417 |

| White race | 0.709 | 0.173 | 1055.508 | 4.087 | 0.000 | 0.368 | 1.049 |

| Age | −0.026 | 0.004 | 1126.304 | −6.416 | 0.000 | −0.034 | −0.018 |

| TBSA | −0.007 | 0.004 | 1101.819 | −1.736 | 0.083 | −0.014 | 0.001 |

| Rehab days | −0.003 | 0.003 | 997.449 | −0.837 | 0.403 | −0.009 | 0.004 |

| Sex | 0.170 | 0.138 | 1131.088 | 1.229 | 0.219 | −0.101 | 0.441 |

| Active range of motion deficits | −0.152 | 0.127 | 1151.133 | −1.195 | 0.232 | −0.402 | 0.098 |

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to examine potential racial/ethnic disparities in community integration for the 2 yrs after burn injury hospital discharge. This study expands upon previous findings that document racial/ethnic disparities in burn rates1–3 and outcomes,10 as well as racial/ethnic disparities in community integration in other injury populations.16 Trajectories of CIQ scores suggested that on average, individuals with burn injuries experienced a decline in community integration from hospital discharge to 6 mos of follow-up, and then slightly improved at 1 yr, and finally plateaued at 2 yrs. Hierarchical linear models suggested that white individuals had higher community integration score trajectories over time than black and Hispanic individuals and that community integration scores were similar between black and Hispanic individuals. These racial/ethnic disparities in community integration trajectories remained even after accounting for age, sex, total burned surface area, number of days in rehabilitation, and active range of motion deficits.

The finding in the current study that community integration scores decreased from discharge to 6 mos for all three racial/ethnic groups is congruent with observations of Esselman14 that individuals with burn injuries face initial difficulty with community integration as they may be experiencing barriers because of the physical recuperation from the burn injury (ie, respiratory issues, weakness, and fatigue). A slight increase or plateauing in community integrations scores occurred for the different racial/ethnic groups at 1 yr after discharge, and the plateaus continued to 2 yrs, suggesting a more level period of adjustment. Approximately 90% of individuals with burn return to work within 2 yrs after injury,21 which may account in part for this finding as most gains in physical recovery will have occurred by 2 yrs after injury. Psychosocial adjustment has also been found to improve over time in individuals with burn as Wiechman et al.22 found at 1 mo, whereas 54% of individuals with burn endorsed symptoms of moderate to severe depression, this figure reduced to 43% at 2 yrs. A similar process may be occurring with community integration.

The current findings of racial/ethnic disparities for black and Hispanic individuals with burn in community integration over time relative to whites were consistent with previous literature on other types of racial/ethnic disparities after burn. White individuals with burn have been found to be 10 times more likely to resume work responsibilities within 12 mos of injury compared with racial/ethnic minorities.10 In addition, higher mortality has been found in black men after burn.12 These outcomes may be due to several factors. First, Bedri et al.11 found racial/ethnic minority groups have higher risk of comorbid medical conditions compared with white individuals with burn, and this may impact the severity and frequency of physical recuperation from injury, reducing full community integration. Second, because of strong family-based cultural values, racial/ethnic minorities may receive additional and longer support from immediate family members, resulting in less independence (as often emphasized by the rehabilitation team), and as a result lower community integration.23 Third, people from racial/ethnic minority groups may be less likely to receive and make use of rehabilitation services, as has been found in other rehabilitation populations, such as cardiac rehabilitation,24 which could reduce rehabilitation gains and therefore community integration. Finally, lower community integration among black and Hispanic individuals with burn injuries may have to do with neighborhood or workplace inaccessibility (eg, lack of wheelchair friendly curbs, absence of timed pedestrian crossings) as well as general deficiency of rehabilitation and other healthcare services.

Clinical Implications

Rehabilitation treatment focused on improving community engagement and integration including work, school, and community activities is imperative for the quality of life of individuals with burn injuries.14 Although individuals with burn injuries in integrated social and occupational wellness treatment protocols experience greater recovery25 and better health-related quality of life,15 it is unclear the extent to which these treatments are effective for racial/ethnic minorities with burn injuries or if these programs could be adapted to better meet the needs of minority rehabilitation populations. Resources should be devoted to help rehabilitation programs include social and occupational programing to increase community integration resulting in improved quality of life for individuals with burn injuries. As lower overall community integration scores have resulted in less productive activity levels in black and Hispanic individuals with TBI,16 resources and trainings should be devoted to help rehabilitation programs engage in culturally targeted treatment focusing on racial/ethnic, sex, or familial roles support that may be impeding recovery and community integration.

Limitations

The findings of the current study should be interpreted within the context of several limitations. First, the study evaluated community integration at discharge (preinjury recall), 6 mos, 1 yr, and 2 yrs from injury with no investigation within the first 6 mos of treatment. As initial recovery from burn injuries may be impacting community integration,14 future researchers are encouraged to assess at 1, 2, and 4 mos after injury. Similarly, recall bias may have affected participants’ CIQ scores at discharge, so proxy measures may improve accuracy. Second, the current study only investigated two ethnic/racial minority groups, black and Hispanic, because of limited sample sizes for other groups (ie, Asian, Native American). In addition, Middle-Eastern and Indian participants were classified as white by participating BMS sites during data collection. Future studies should aim to recruit and assess for differences in multiple racial/ethnic minority groups to provide greater understanding of additional disparities. Another limitation of the study is the high percentage of missing data. Although robust state of the art full information maximum likelihood estimation was used to account for missing data, doing so can compress estimation of standard errors and inflate statistical significance, suggesting that the results of the analyses should be interpreted with an appropriate degree of caution. Furthermore, the sample consisted of participants receiving treatment for burns within hospitals located in one of only six major metropolitan areas. Further research would benefit from a sample representing more geographically diverse areas. Finally, as location of burn and TBSA have been found to impact social relationships and quality of life in individuals with burn injuries,26 future researchers are encouraged to investigate whether location of burn and TBSA impact community integration over time.

CONCLUSIONS

The current study investigated racial/ethnic disparities in burn rates and outcomes, as well as racial/ethnic disparities in community integration. Our findings suggest trajectories of community integration scores generally conformed to a decrease from discharge to 6 mos, then a slight increase, and then plateau over time. In addition, we found that white individuals had higher community integration score trajectories over time than black and Hispanic individuals and that community integrations scores were similar between black and Hispanic individuals providing additional support for racial/ethnic disparities in individuals with burn. Rehabilitation programs for individuals with burn injury are recommended to integrate social and occupational wellness programming within a culturally conscious treatment framework to address these racial/ethnic disparities in burn outcomes.

What Is Known

Previous literature documents racial/ethnic disparities in burn rates, burn outcomes, and community integration in other injury populations.

What Is New

In a sample of 1773 adults receiving treatment for burns in one of six major metropolitan hospitals, the current study found that white individuals had higher community integration score trajectories over time than black and Hispanic individuals and that community integrations scores were similar between black and Hispanic individuals. These disparities remained even after accounting for demographics. The findings suggest that additional rehabilitation resources should be targeted to helping black and Hispanic individuals integrate back into their communities after burn injury.

Acknowledgments

The Burn Model System National Database was supported by the US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR) in collaboration with the NIDILRR-funded Burn Model System (BMS) Centers. This study was supported by grant numbers 90DPBU0001 and 90DPBU0004. However, these contents do not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of the BMS Centers, NIDILRR, or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Footnotes

Financial disclosure statements have been obtained, and no conflicts of interest have been reported by the authors or by any individuals in control of the content of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Web-based injury statistics query and reporting system (WISQARS). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention site. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/. Accessed June 25, 2019

- 2.Edelman LS, Cook LJ, Saffle JR: Burn injury in Utah: demographic and geographic risks. J Burn Care Res 2010;31:375–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Istre GR, McCoy MA, Osborn L, et al. : Deaths and injuries from house fires. N Engl J Med 2001;344:1911–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fagenholz PJ, Sheridan RL, Harris NS, et al. : National study of emergency department visits for burn injuries, 1993 to 2004. J Burn Care Res 2007;28:681–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hulland E, Chowdhury R, Sarnat S, et al. : Socioeconomic status and non-fatal adult injuries in selected Atlanta (Georgia USA) hospitals. Prehosp Disaster Med 2017;32:403–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peck MD: Epidemiology of burns throughout the world. Part I: distribution and risk factors. Burns 2011;37:1087–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kerby JD, McGwin G Jr., George RL, et al. : Sex differences in mortality after burn injury: results of analysis of the National Burn Repository of the American Burn Association. J Burn Care Res 2006;27:452–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ederer IA, Hacker S, Sternat N, et al. : Gender has no influence on mortality after burn injuries: a 20-year single center study with 839 patients. Burns 2019;45:205–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doctor N, Yang S, Maerzacker S, et al. : Socioeconomic status and outcomes after burn injury. J Burn Care Res 2016;37:e56–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wrigley M, Trotman BK, Dimick A, et al. : Factors relating to return to work after burn injury. J Burn Care Rehabil 1995;16:445–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bedri H, Romanowski KS, Liao J, et al. : A national study of the effect of race, socioeconomic status, and gender on burn outcomes. J Burn Care Res 2017;38:161–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murphy S, Clark DE, Carter DW: Racial disparities exist among burn patients despite insurance coverage. Am J Surg 2019;218:47–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Esselman PC, Ptacek JT, Kowalske K, et al. : Community integration after burn injuries. J Burn Care Rehabil 2001;22:221–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Esselman PC: Burn rehabilitation: an overview. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2007;88:S3–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dyster-Aas J, Willebrand M, Wikehult B, et al. : Major depression and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms following severe burn injury in relation to lifetime psychiatric morbidity. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2008;64:1349–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sander AM, Pappadis MR, Davis LC, et al. : Relationship of race/ethnicity and income to community integration following traumatic brain injury: investigation in a non-rehabilitation trauma sample. NeuroRehabilitation 2009;24:15–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klein MB, Lezotte DL, Fauerbach JA, et al. : The National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research burn model system database: a tool for the multicenter study of the outcome of burn injury. J Burn Care Res 2007;28:84–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goverman J, Mathews K, Holavanahalli RK, et al. : The National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research Burn Model System: twenty years of contributions to clinical service and research. J Burn Care Res 2017;38:e240–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gerrard P, Kazis LE, Ryan CM, et al. : Validation of the Community Integration Questionnaire in the adult burn injury population. Qual Life Res 2015;24:2651–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Corrigan JD, Deming R: Psychometric characteristics of the Community Integration Questionnaire: replication and extension. J Head Trauma Rehabil 1995;10:41–53 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brych SB, Engrav LH, Rivara FP, et al. : Time off work and return to work rates after burns: systematic review of the literature and a large two-center series. J Burn Care Rehabil 2001;22:401–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wiechman SA, Ptacek JT, Patterson DR, et al. : Rates, trends, and severity of depression after burn injuries. J Burn Care Rehabil 2001;22:417–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Niemeier JP, Kaholokula JK, Arango-Lasprilla JC, et al. : The effects of acculturation on neuropsychological rehabilitation of ethnically diverse persons. in: Uomoto JM, Wong TM (eds): Multicultural Neurorehabilitation: Clinical Principals for Rehabilitation Professionals. New York, NY, Springer, 2015:139–68 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gregory PC, LaVeist TA, Simpson C: Racial disparities in access to cardiac rehabilitation. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2006;85:705–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schneider JC, Bassi S, Ryan CM: Barriers impacting employment after burn injury. J Burn Care Res 2009;30:294–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thombs BD, Notes LD, Lawrence JW, et al. : From survival to socialization: a longitudinal study of body image in survivors of severe burn injury. J Psychosom Res 2008;64:205–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]