ABSTRACT

The aim of this study was to estimate the age- and gender-specific prevalence and quality of care among patients using medication targeting obstructive lung disease in the five regions of Greenland. The study was designed as a cross-sectional study. Data on patients using medication targeting obstructive lung disease was obtained from the electronically medical record used in Greenland. The prevalence was calculated using the population of Greenland as background population. The quality of care was determined using indicators proposed by international literature and the Steno Diabetes Center Greenland guidelines. The total prevalence of patients using medication targeting obstructive lung disease was 7.5%. The prevalence was significantly higher among women compared to men and differed significantly between the five regions. Smoking status, blood pressure and spirometry were registered within one/two years for 29.8%/43.2%, 29.2%/41.1% and 15.9%/26.0% of the patients, respectively. Regional differences were observed for all indicators.

The use of medication targeting obstructive lung disease is common in Greenland. Yet, the quality of care was low and interventions improving the quality of care is recommended.

KEYWORDS: Chronic obstructive lung disease, Greenland, Inuit, quality of care, prevalence

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is an immense, worldwide health issue with severe impacts on quality of life, and the cause of premature death[1]. In fact, COPD claimed 3 million lives in 2016 and is now the third largest cause of death [1,2]. There is extensive knowledge on what constitutes risk factors and how the disease is most efficiently treated. In addition to cigarette smoking, which is the most commonly encountered risk factor, other factors that influence the risk of developing COPD are genetic factors, age and sex, lung growth and development, exposure to particles, socioeconomic status, asthma and airway hyper reactivity, chronic bronchitis or infections [1,3]. In Greenland, 55% of the population above 15 years of age smoke on daily basis and therefore a high prevalence of COPD in Greenland could be expected [4].

Earlier studies have estimated a prevalence of COPD in Greenland and found a prevalence of patients treated with medication targeting obstructive lung disease aged 50 or above was 6.1% and 7.9% in 2013 and 2016, respectively [5,6]. A comparable prevalence (6.7%) of COPD was established for Canadian Inuit living in Ottawa in 2018, and other studies in Nordic countries have shown similar results [7–9].

According to the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) guidelines, a patient with “appropriate symptoms” and “significant exposures to noxious environmental stimuli” requires a post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC ratio less than 0.7, measured by spirometry, to conclude the diagnosis of COPD [1]. The guidelines recommend annual spirometry test for COPD patients to monitor the disease [1].

In Greenland, the health care system introduced a lifestyle initiative in 2011 focusing on prevention and quality of care among patients with diabetes, hypertension and COPD [10]. The initiative included annual control of COPD patients and their digitally registered prescriptions, smoking status, spirometry results and other lifestyle factors. Although increasing from 2013 to 2016, the use of spirometry and diagnostic classification of COPD was reported suboptimal in Greenland [5,6]. A similar trend is seen in other countries, where use of spirometry has also been reported too low compared to guidelines [11,12]. The current use of spirometry to diagnose and monitor COPD in Greenland is unknown.

This year (2020), the Steno Diabetes Center Greenland (SDCG) was established in Greenland, and the centre is expected to strengthen and further develop the work of the lifestyle initiative with focus on COPD, diabetes and hypertension [13]. It is thus important to establish a baseline of the use of spirometry among patients receiving medication targeting obstructive lung disease in order to improve diagnostics and treatment of COPD in Greenland.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to estimate the age- and gender-specific prevalence of patients using medication targeting obstructive lung disease in the five regions of Greenland, and to evaluate the use of spirometry to set COPD diagnosis. The aim was furthermore to estimate the regional quality of care among patients using medication targeting obstructive lung disease.

Materials and methods

Study design

The study was performed as a cross-sectional study using data from the electronical medical record (EMR) [14] in Greenland.

Setting

Even though Greenland is the largest island in the world, covering an area of more than 2 million km2, most of the area is uninhabited because of the icecap [14]. The population thus lives along the coastline, distributed in 17 towns and approximately 60 minor settlements [15].

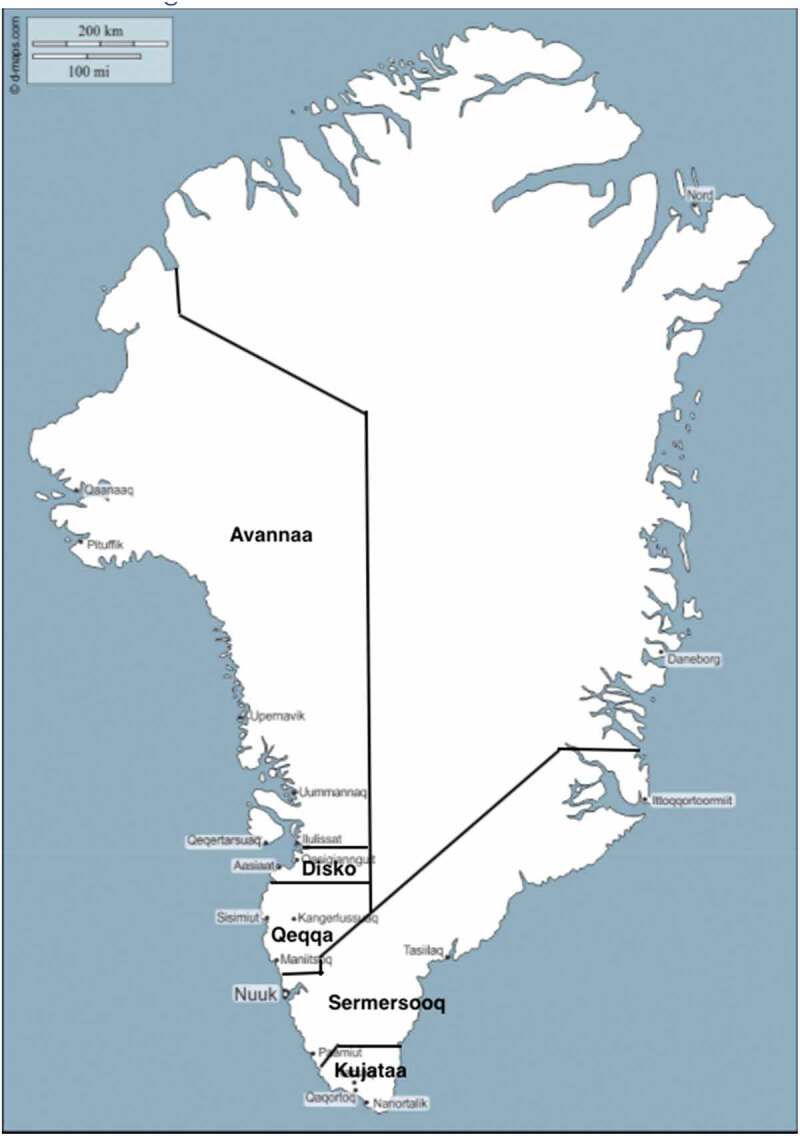

Despite the large distances and remote locations, primary health care is provided in all towns and settlements. The health care system in Greenland is divided into five health care regions covering a number of towns and settlements (see Figure 1). Each town has a primary health care centre, whereas the settlements have smaller health care units [15,16]. Secondary specialised health care is provided by Queen Ingrid’s Hospital in Nuuk.

Figure 1.

The figure illustrates the five health care regions of Greenland (Avannaa, Disko, Kujataa, Sermersooq and Qeqqa)

The figure is modified from a free map obtained from: https://d-maps.com/carte.php?num_car=172070&lang=en&fbclid=IwAR2d6vc2eIeEDMFR58rDP59F0GoA

Patients with COPD are treated in the local health care centres. In case of severe or complicated COPD, patients are however referred to the hospital in Nuuk or consulted by visiting specialists from Queen Ingrid Hospital.

Since 2014, all consultations, including the hospital, health care centre and settlement consultation, have been registered in the same EMR [6,14].

Prescription medicine and all services in the health care system are free of charge.

Study population and variables

The study population includes Greenlandic residents, aged 20 or above, with prescribed medication targeting obstructive lung disease.

Medical data were extracted from the EMR [14]. Data were extracted from patients from all parts of Greenland, except the east coast town, Tasiilaq, where the EMR is not fully implemented. Inclusion criteria for patients included in the study was a registration of an ongoing and active prescription of anatomical therapeutic chemical (ATC) classification code R03 [17] within the period from 1 January 2018 to 31 December 2019. The ATC-classification code R03 covers all medicine used in Greenland targeting obstructive lung disease.

Information extracted from the EMR included age, weight, height, blood pressure, spirometry data, smoking status and presence of COPD/asthma diagnosis. Basic characteristics were compared between men and women, and between young (20–39 years) and senior (40–79 years) patients. To estimate the age-specific prevalence of patients receiving medication targeting obstructive lung disease, patients were divided into age groups of 10 years. Quality of care was described according to process indicators as proposed by international literature and modified to fit the SDCG guidelines. The most recent measurements were used [13,18]. The indicators comprised smoking status, spirometry, blood pressure, pneumococcal vaccination, and influenza vaccination. Smoking status was defined as current smoker or not. Information on quantity and former smoking (pack years) was not available in this study. Spirometry and blood pressure were defined as the latest registered measurement or not measured. Data on smoking status, spirometry and blood pressure were broken down by whether the registration was made within 1 or 2 years. Furthermore, the most recent registrations were used for calculating means and standard deviations. For spirometry, the data represent the best post- or pre-bronchodilator measurement, as it was not possible to retrieve information regarding whether a post-bronchodilator had been taken or not. Pneumococcal- and influenza vaccination were defined as given or not given.

The entire population of Greenland aged above 20 years, except the excluded town Tasiilaq, was used as background population. This accounts for approximately 95% of the population and was extracted from Greenland Statistics’ online statistics bank [19].

Statistical analysis

Estimates were calculated with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Normally distributed parameters were described using mean and standard deviation (SD). Check for normal distribution was performed using QQ-plot. Normally distributed variables were compared using t-tests. Proportions were compared using chi-square tests. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 23.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL). P-values below 0.05 were considered significant.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee for Medical Research in Greenland (no. 2020–13) and by the Agency of Health and Prevention in Greenland.

Results

A total of 2,947 patients with a mean age of 53 years were extracted based on an active prescription of medication targeting obstructive lung disease in the EMR within the two-year period of 2018–2019. Of these, 64.3% (1896) were women and 35.7% (1051) were men. Seventy-three percent (2148) of the patients were categorised as seniors (40–79 years of age), while 24% (707) were categorised as young (20–39 years of age).

Basic characteristics

Table 1 shows basic characteristics of the study population according to gender and according to overall age group (young versus senior).

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of the study population

| Men |

Women |

Total |

Young (20–39 years) |

Seniors (40–79 years) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean (SD) | N | Mean (SD) | P | N | Mean (SD) | N | Mean (SD) | N | Mean (SD) | P | |

| Age (years) | 1,051 | 55 (15.8) | 1,896 | 52 (15.7) | <0.001 | 2,947 | 53 (15.8) | 707 | 31 (5.5) | 2,148 | 59 (9.7) | <0.001 |

| Weight (kg) | 420 | 84 (22.1) | 776 | 75 (20.1) | <0.001 | 1,196 | 78 (21.4) | 143 | 82 (22.0) | 1,001 | 78 (21.2) | 0.038 |

| Height (cm) | 388 | 170 (8.5) | 724 | 159 (47.1) | 0.041 | 1,112 | 167 (84.0) | 137 | 165 (9.0) | 927 | 162 (9.7) | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 384 | 29 (6.9) | 715 | 30 (7.6) | 0.041 | 1,099 | 30 (7.3) | 132 | 30 (7.7) | 921 | 30 (7.3) | 0.876 |

| Blood pressure, systolic (mmHg) | 360 | 134 (15.1) | 670 | 131 (15.7) | 0.003 | 1,030 | 132 (15.6) | 88 | 126 (13.6) | 883 | 133 (15.4) | <0.001 |

| Blood pressure, diastolic (mmHg) | 360 | 82 (10.1) | 669 | 80 (9.4) | <0.001 | 1,029 | 81 (9.7) | 88 | 79 (9.9) | 882 | 81 (9.5) | 0.064 |

| FEV1 (L) | 260 | 2.6 (1.0) | 423 | 2.2 (0.7) | <0.001 | 683 | 2.4 (0.9) | 106 | 3.2 (0.8) | 557 | 2.3 (0.8) | <0.001 |

| FEV1 (%) | 258 | 76.5 (24.6) | 423 | 90.3 (23.1) | <0.001 | 681 | 85.1 (24.6) | 106 | 92.1 (16.0) | 555 | 84.1 (25.6) | <0.001 |

| FVC (L) | 261 | 4.0 (1.2) | 423 | 3.1 (0.8) | <0.001 | 684 | 3.4 (1.1) | 106 | 4.2 (1.0) | 558 | 3.3 (1.0) | 0.002 |

| FVC (%) | 257 | 93.6 (22.2) | 423 | 106.3 (101.1) | 0.048 | 680 | 101.5 (81.1) | 106 | 102.2 (16.2) | 554 | 101.8 (89.4) | 0.968 |

| FEV1/FVC -ratio (%) | 261 | 64.5 (13.6) | 423 | 72.2 (10.5) | <0.001 | 684 | 69.2 (12.3) | 106 | 76.8 (7.3) | 558 | 68.1 (12.5) | <0.001 |

| N | Prevalence (n) | N | Prevalence (n) | P | N | Prevalence (n) | N | Prevalence (n) | N | Prevalence (n) | P | |

| Current smoker (%) | 384 | 47.4 (182) | 722 | 51.9 (375) | 0.150 | 1,106 | 50.4 (557) | 128 | 47.7 (61) | 928 | 52.4 (486) | 0.317 |

| COPD diagnose coded, R95 (%) | 1,051 | 6.4 (67) | 1,896 | 4.5 (85) | 0.026 | 2,947 | 5.2 (152) | 707 | 0.14 (1) | 2,148 | 6.47 (139) | <0.001 |

| Asthma diagnose coded, R96 (%) | 1,051 | 2.4 (25) | 1,896 | 4.0 (76) | 0.020 | 2,947 | 3.4 (101) | 707 | 5.09 (36) | 2,148 | 3.03 (65) | <0.001 |

N = number of patients, SD = standard deviation, P = P-values, n = number of patients with positive answer

When looking at gender, there was a statistically significant difference between men and women. Men were significantly older, weighed more, were taller, and had a higher blood pressure (systolic and diastolic). Men had a lower force expiratory volume within 1 s and force vital capacity in % of the expected (FEV1 (%) and FVC (%)) compared to women, resulting in a significantly impaired lung function (FEV1/FVC-ratio) (p < 0.001).

Among the 2947 included patients, 1,106 were registered with a smoking status. Of these 47.4% women and 51.9% men were registered as current smokers, and for the pooled gender 50.4% (n = 557) were current smokers. There was no statistically significant difference between men and women according to smoking status.

Of the 2,947 patients receiving medication targeting obstructive lung disease, a significantly higher proportion of men was diagnosed with COPD (ICPC2: R95) compared to women (p < 0.026, 6.4% versus 4.5%). In contrast, a significantly higher proportion of women had been diagnosed with asthma (ICPC2: R96) compared to men (p < 0.020, 4.0% versus 2.4%). The total proportion of patients registered with COPD or asthma was 5.2% (152) and 3.4% (101), respectively.

When comparing the young group (20–39 years) with the senior group (40–79 years), the seniors had significantly impaired lung function (FEV1/FVC-ratio) compared to the young group (p < 0.001, 68.1% versus 76.8%). A significantly higher proportion of seniors were diagnosed with COPD compared to the young group (p < 0.001, 6.47% versus 0.14%), whereas a higher proportion of young patients were diagnosed with asthma compared to the seniors (p < 0.001, 5.09% versus 3.03%).

Prevalence

Table 2 shows the estimated age- and gender-specific prevalence of patients using medication targeting obstructive lung disease in Greenland. The total prevalence of patients aged 20–79 years was 7.5%. The prevalence of patients using medication targeting obstructive lung disease was significantly higher among women aged 20–79 years compared to men (p < 0.001). Overall, the prevalence increased with age. The prevalence in the group of seniors (40–79 years) was 9.7%, while the young group (aged 20–39 years) had a lower prevalence at 4.4% (p < 0.001).

Table 2.

The prevalence of patients using medication targeting obstructive lung disease

| Women | Men | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (95% CI) (n/N) | (95% CI) (n/N) | P | (95% CI) (n/N) | |

| Total prevalence (%), 20–79 years | 10.4 (9.9–10.8) (1,845/17,757) |

4.9 (4.7–5.2) (1,010/20,407) |

<0.001 | 7.5 (7.2–7.7) (2,855/38,164) |

| Prevalence (%) in age groups | ||||

| 20–29 years | 4.9 (4.2–5.5) (198/4,080) |

2.1 (1.7–2.5) (91/4,341) |

<0.001 | 3.4 (3.0–3.8) (289/8,421) |

| 30–39 years | 7.9 (7.0–8.8) (292/3,700) |

3.2 (2.7–3.8) (126/3,936) |

<0.001 | 5.5 (5.0–6.0) (418/7,636) |

| 40–49 years | 9.5 (8.4–10.7) (257/2,692) |

4.1 (3.4–4.8) (133/3,230) |

<0.001 | 6.6 (6.0–7.2) (390/5,922) |

| 50–59 years | 12.8 (11.8–13.8) (532/4,157) |

5.1 (4.4–5.7) (249/4,920) |

<0.001 | 8.6 (8.0–9.2) (781/9,077) |

| 60–69 years | 16.98 (15.41–18.55) (371/2,185) |

9.9 (8.8–11.0) (278/2,819) |

<0.001 | 13.0 (12-0-13.9) (649/5,004) |

| 70–79 years | 20.7 (18.1–23.3) (195/943) |

11.5 (9.6–13.3) (133/1,161) |

<0.001 | 15.6 (14.0–17.1) (328/2,104) |

| 80+ years | 16.6 (12.4–20.7) (51/308) |

18.9 (13.7–24.1) (41/217) |

0.488 | 17.5 (14.3–20.) (92/525) |

| Young (%), 20–39 years | 6.30 (5.8–6.8) (490/7780) |

2.6 (2.3–3.0) (217/8,277) |

<0.001 | 4.4 (4.1–4.7) (707/16,057) |

| Seniors (%), 40–79 years | 13.6 (12.9–14.3) (1,355/9,977) |

6.5 (6.1–7.0) (793/12,130) |

<0.001 | 9.7 (9.3–10.1) (2,148/22,107) |

95% CI = 95% confidence intervals, n/N = number of patients/population, P = p-values.

The total prevalence of patients treated with medication targeting obstructive lung disease differed significantly between the five regions (p < 0.001), see Table 3. The total prevalence within a region ranged from 5.9% in Avannaa to 8.5% in Disko. The order in prevalence from highest to lowest prevalence was as follows: Disko>Sermersooq>Qeqqa>Kujataa>Avanaa. A statistically significant regional difference was also present when dividing the patients into young and seniors (p < 0.001).

Table 3.

The prevalence of patients using medication targeting obstructive lung disease in the five regions of Greenland

| Sermersooq | Qeqqa | Kujataa | Avannaa | Disko | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (95% CI) (n/N) | (95% CI) (n/N) | (95% CI) (n/N) | (95% CI) (n/N) | (95% CI) (n/N) | ||

| Total prevalence (%) 20–79 years |

8.0 (7.6–8.4) (1,179/14,735) |

7.6 (6.9–8.2) (505/6,680) |

7.2 (6.5–8.0) (339/4,694) |

5.9 (5.4–6.5) (443/7,459) |

8.5 (7.7–9.3) (389/4,596) |

<0.001 |

| Young (%) 20–39 years |

5.1 (4.6–5.7) (339/6,617) |

4.2 (3.5–5.0) (116/2,738) |

3.7 (2.8–4.6) (65/1,758) |

3.3 (2.7–3.9) (102/3,087) |

4.6 (3.6–5.5) (85/1,857) |

<0.001 |

| Seniors (%) 40–79 years |

10.3 (9.7–11.0) (840/8,118) |

9.9 (8.9–10.8) (389/3,942) |

9.3 (8.3–10.4) (274/2,936) |

7.8 (7.0–8.6) (341/4,372) |

11.1 (9.9–12.3) (304/2,739) |

<0.001 |

95% CI = 95% confidence intervals, n/N = number of patients/population, P = p-values.

Among the 2,947 patients using medication targeting obstructive lung disease, 684 had received a spirometry test. Of those, 302 (44.2%) actually had a FEV1/FVC-ratio below 70% indicating obstruction (data not shown). Among patients using medication targeting obstructive lung disease and with a performed spirometry within 2 years, men had a significantly higher prevalence of obstruction than women (61.7% vs. 33.3%, p < 0.001) (data not shown).

Quality of care

Table 4 shows the proportion of senior patients (40–79 years) using medication targeting obstructive lung disease, for whom specific quality of care-indicators were registered separated into the five regions of Greenland. All indicators showed a significant difference across the five regions (p < 0.001, p < 0.004), except influenza vaccination given within 1 year (p = 0.322). The indicators with the highest registration rate were smoking status and overall blood pressure. In total, smoking status was registered for 29.8% and 43.2% of the patients within 1 and 2 years, respectively. This is lower than 85–90% as suggested by national and international guidelines [1,13,20]. Smoking status registered within 1 year ranged from 23.6% in Sermersooq to 48.7% in Disko. The order from highest to lowest between the five regions within 1 year was as follows: Disko>Kujataa>Qeqqa>Avannaa>Sermersooq. Only minor changes in the order were seen when looking at the registration rates within 2 years.

Table 4.

The quality of care for seniors, aged 40–79 years, using medication targeting obstructive lung disease in the five regions of Greenland

| Sermersooq N = 840 |

Qeqqa N = 389 |

Kujataa N = 274 |

Avannaa N = 341 |

Disko N = 304 |

P | Total N = 2,148 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Process indicators registered within 1 or 2 years, % (n) | |||||||

| Smoking - within 1 year - within 2 years |

23.6 (198) 38. (319) |

29.3 (114) 45.0 (175) |

30.3 (83) 43.1 (118) |

28.7 (98) 36.1 (123) |

48.7 (148) 63.2 (192) |

<0.001 <0.001 |

29.8 (641) 43.2 (927) |

| Blood pressure - within 1 year - within 2 years |

21.4 (180) 35.0 (294) |

30.8 (120) 42.7 (166) |

28.1 (77) 37.6 (103) |

27.6 (94) 34.9 (119) |

51.3 (156) 66.1 (201) |

<0.001 <0.001 |

29.2 (627) 41.1 (883) |

| Spirometry - within 1 year - within 2 years |

13.9 (117) 23.8 (200) |

12.1 (47) 24.7 (96) |

12.4 (34) 20.1 (55) |

21.1 (72) 25.5 (87) |

23.4 (71) 39.5 (120) |

<0.001 <0.001 |

15.9 (341) 26.0 (558) |

| Pneumococcal vaccination | 14.4 (121) | 14.7 (57) | 9.9 (27) | 9.1 (31) | 2.3 (7) | <0.001 | 11.3 (243) |

| Influenza vaccination - within 1 year |

17.9 (150) | 19.3 (75) | 17.9 (49) | 14.4 (49) | 14.8 (45) | 0.322 | 17.1 (368) |

| Influenza vaccination | 26.5 (223) | 24.7 (96) | 30.7 (84) | 20.5 (70) | 19.1 (58) | 0.004 | 24.7 (531) |

N = number of patients, n = number of patients with indicator registered, P = P-values.

In the total study population, blood pressure was registered for 29.2% and 41.1% of the patients within 1 and 2 years, respectively. This is lower than 85–90% as suggested by national and international guidelines [1,13,20]. The registration rate of blood pressure ranged from 21.4% to 51.3% (Sermersooq-Disko) within 1 year, and 35.0% to 66.1% (Avannaa-Disko) within 2 years.

In total, the one- and two-year rate having received a spirometry test was 15.9% and 26.0%, respectively. Here, the order between the five regions within two years was: Disko>Avannaa>Qeqqa>Sermersooq>Kujataa ranging from 20.1% in Kujataa to 39.5% in Disko. The indicator with the lowest registration rate was pneumococcal vaccination, which 11.3% of the patients had received.

There was no difference with respect to genders. However, a highly significant difference between the age groups young and seniors was identified, where seniors overall had a higher registration rate (data not shown).

Discussion

The prevalence of patients aged 20–79 years treated with medication targeting obstructive lung disease was 7.5% (Table 2). Of these, a significantly higher proportion were women than men, and half the patients were current smokers. Seventy-three percent of the study population were considered seniors (40–79 years of age). The senior patients had significantly impaired lung function compared to the young group (20–39 years) as seen from a lower FEV1 of expected as well as FEV1/FVC ratio. Significantly more seniors were diagnosed with COPD compared to the young, whereas a significantly larger proportion of the young patients were diagnosed with asthma. Our study furthermore shows that the overall quality of care was too low compared to guidelines [13,20], and standard measurements as smoking status, blood pressure and spirometry were registered in 43.2%, 41.1% and 26.0% within 2 years, respectively (Table 4). Both the prevalence and the quality of care differed significantly within the five regions in Greenland.

Prevalence

In a previous study from 2016 by Nielsen et al [6]., the same method was used to estimate the prevalence of patients, i.e. using medication targeting obstructive lung disease. They found a prevalence of patients ≥50 years to be 7.9%, and thus quite similar to the total prevalence in this study (7.5%, Table 2). However, since the total prevalence in our study was calculated based on patients aged 20–79 years, it is more relevant to compare the prevalence of our senior group with the age range 40–79 years to the prevalence presented by Nielsen et al. We found a prevalence in the senior group to be 9.7%, and thus higher than the prevalence found by Nielsen et al. (7.9%). This apparent increase in prevalence could be explained by an enhanced focus on lifestyle diseases in Greenland, which might lead to more prescriptions on medication targeting obstructive lung disease. Our study showed that the prevalence of patients using medication against obstructive lung disease increases with age, which is a known dynamic of COPD[21]. The number of seniors in Greenland have increased since 201619, and it is thus also possible that the actual prevalence of obstructive lung disease is increasing in Greenland partly because of the increasing age of the Greenlandic population. The highest regional prevalence was observed in the Region Disko, which also had the highest registration of smoking and spirometry. Region Disko is very well-organised when it comes to focus on and management of chronic diseases, e.g. diabetes, and the varying regional prevalence of patients using medication against obstructive lung diseases might thus be associated with a varying degree of organisation of chronic diseases among the five regions [14].

The prevalence of COPD in other Inuit populations has been investigated. A study by Smylie et al. [7] investigated health determinants, health status and health care access for Canadian Inuit living in Ottawa, Canada. They found the prevalence of COPD to be 6.7% (95% CI: 3.1–10.6) [7]. Furthermore, studies from northern countries have shown similar results [8,9].

Another study conducted by Ospina et al. [22] focused on whether differences in incidence and prevalence of COPD exist between Canadian Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal peoples. They found that all Aboriginal peoples had COPD incidence rates significantly higher compared to the non-Aboriginal group (Incidence rate ratio [IRR]: 2.1; 95% CI: 1.97–2.27). Furthermore, when divided into groups (First Nation peoples, Inuit and Métis) and adjusted for covariates (sex, age, socioeconomic status, area of residence), the Inuit were 1.86 to 2.10 times more likely to have COPD from 2002 to 201022.

Among the included study patients, 50.4% were registered as current smokers. This proportion is very close to the proportion of smokers in the general population in Greenland (55%), and other Inuit populations [4,22]. This could partly explain a possible higher prevalence of COPD among Inuit. However, an essential step in the treatment of obstructive lung diseases such as COPD is smoking cessation. A study performed by Backe et al. [23] investigating the prevalence and quality of care of diabetes patients in Greenland, showed a considerably lower proportion of smokers among the diabetes patients (37%), where smoking cessation is also part of treatment. Accurate diagnosis including spirometry performance is important to get the optimal treatment of COPD. For more than 10 years, quality of diabetes care has been ensured including continuous monitoring, active case finding, accurate diagnosis, diagnose coding and performance feedback to clinics [14]. A similar national strategy should be considered in the COPD care.

Our study showed that the prevalence of patients using medication targeting obstructive lung disease was higher among women compared to men. This could be explained by the fact that more adult women become asthmatic. Further contributing to the higher prevalence might be the fact that women more frequently are in contact with the primary health care system [24,25]. Although the prevalence of patients using medication targeting obstructive lung disease was higher among women, only men had obstruction as seen from a FEV1/FVC-ratio <70% (64.5%). This in accordance with more men than women having the diagnosis COPD. Although we found no difference between the proportion of current smokers among men and women, the recent population survey showed that more men than women are heavy smokers4, which thus might contribute to the impaired lung function observed in men.

Quality of care

In the present study, the quality of care was evaluated through the registration rate of several process indicators, such as smoking status or spirometry. The overall quality of care was found to be low, and none of the indicators had a total registration rate above 50% (Table 4). This is far from the international and Danish guidelines as well as the goals set by the SDCG, where smoking status and blood pressure should be performed on 85% of COPD-patients annually [1,13,20]. The same percentage is expected for spirometry biannually. Furthermore, the proportion of patients having performed spirometry within 2 years were lower than the proportion in the previous study by Nielsen et al. (34.8% versus 26.0% in this study) [6].

In a study conducted by Løkke et al., [11] the quality of COPD-care in general practice in Denmark was reviewed. Here, they found that even though the general practice clinics were volunteering to participate in the study, only approximately 40% of the patients in the study had a spirometry performed [11].

Similar results have been found in other countries as well, and the consequence of low spirometry use is misdiagnosis and suboptimal treatment [8,9,12,26,27].

Both prevalence and quality of care varied between the five studied Greenlandic regions. The indicators on quality of care with the biggest regional difference was smoking status and overall blood pressure.

These variations may represent different areas of focus when it comes to the lifestyle diseases, and obstructive lung diseases like COPD might therefore have been overlooked in some regions. Nevertheless, all five regions showed a considerably low quality of care, necessitating a number of enhancements in diagnosis and treatment of patients with obstructive lung diseases.

Strengths and limitations

The major strength of this study is that it covers 95% of the entire Greenlandic population above 20 years. Also, patients were identified electronically through the EMR. However, it is possible that some patients still have handwritten prescriptions, leading to an underestimation of the prevalence. These non-electronically prescriptions are, however, outdated and used infrequently, because the EMR system is part of the physician’s daily routine and is easy to use. However, the regional difference in prevalence could partially be explained by this, because the smaller settlements might occasionally still use the handwritten prescriptions.

Likewise, the registration of the different process indicators (spirometry, vaccination, blood pressure check, etc.) could probably be underestimated, since it is not certain that all performances were registered electronically. Still, all physicians are required by law to keep medical records and clinical tests must be documented, so a possible underestimation is to be considered insignificant. Nevertheless, some registrations could have been made in the journal text rather than in the lifestyle table and therefore not included. Regarding smoking history, it is a limitation that we can only access information on whether a patient is currently smoking or not. It is highly relevant to have more information on their smoking history in order to interpret the results.

Conclusion

In conclusion, treatment with medication targeting obstructive lung disease is widely used in Greenland. Yet, the quality of care including spirometry to set a diagnosis among patients was low. It is highly recommended to introduce a new strategy facilitating the improvement of quality of care for patients with symptoms of obstructive lung disease including active case finding among smokers, easy access to spirometry and other diagnostic facilities, close monitoring of prevalence and performance feedback on quality of care to local clinics.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- [1].Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive lung disease: the GOLD science committee report 2019. Global initatitive for Chronic Obstructive Lung disease (GOLD), https://goldcopd.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/GOLD-2019-v1.7-FINAL-14Nov2018-WMS.pdf (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- [2].Global health estimates 2016: disease burden by cause, age, sex, by country and by region, 2000–2016. Geneva. World Health Organization., https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/the-top-10-causes-of-death (2018). [Google Scholar]

- [3].Postma DS, Bush A, van den Berge M.. Risk factors and early origins of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet. 2015;385(9971):899–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Larsen CVL, Bjerregaard P, et al. Befolkningsundersøgelsen i Grønland 2018. Levevilkår, livstil og helbred. 2019:26-29. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Olsen S, Jarbøl DE, Kofoed M, et al. Prevalence and management of patients using medication targeting obstructive lung disease: a cross-sectional study in primary healthcare in Greenland. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2013;72(1):20108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Nielsen LO, Olsen S, Jarbol DE, et al. Spirometry in Greenland: a cross-sectional study on patients treated with medication targeting obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2016;75(1):33258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Smylie J, Firestone M, Spiller MW. Our health counts: population-based measures of urban Inuit health determinants, health status, and health care access. Can J Public Health = Revue Canadienne De Sante Publique. 2018;109(5–6):662–670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Broström E, Jõgi R, Gislason T, et al. The prevalence of chronic airflow obstruction in three cities in the Nordic-Baltic region. Respir Med. 2018;143:8–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Backman H, Eriksson B, Rönmark E, et al. Decreased prevalence of moderate to severe COPD over 15 years in northern Sweden. Respir Med. 2016;114:103–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Aia E, Reiss MLP. Smoking among patients in the primary health care system in Nuuk, Greenland. Clin Nurse Stud. 2014;2014:2. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Løkke A, Søndergaard J, Hansen MK, et al. Management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in general practice in Denmark. Dan Med J. 2020;67(5). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Heffler E, Crimi C, Mancuso S, et al. Misdiagnosis of asthma and COPD and underuse of spirometry in primary care unselected patients. Respir Med. 2018;142:48–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].En styrket diabetes- og livstilsindsats i Grønland, Drejebog for etablering af steno diabetes Center Grønland, https://steno.dk/centre/steno-diabetes-center-groenland (2020).

- [14].Pedersen ML. Diabetes care in the dispersed population of Greenland. A new model based on continued monitoring, analysis and adjustment of initiatives taken. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2019;78:1709257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Meklenborg I, Pedersen ML, Bonefeld-Jørgensen EC. Prevalence of patients treated with anti-diabetic medicine in Greenland and Denmark. A cross-sectional register study. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2018;77(1):1542930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Tvermosegaard M, Rønn PF, Pedersen ML, et al. Validation of cardiovascular diagnoses in the Greenlandic hospital discharge register for epidemiological use. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2018;77(1):1422668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].ATC-systemet og mængde opgjort i DDD, https://sundhedsdatastyrelsen.dk/da/tal-og-analyser/analyser-og-rapporter/laegemidler/atc-og-ddd (2020).

- [18].Gershon AS, Mecredy GC, Aaron SD, et al. Development of quality indicators for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): a modified RAND appropriateness method. Canadian Journal of Respiratory, Critical Care, and Sleep Medicine. 2019;3(1):30–38. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Grønlands Statistik - Statistikbanken, Befolkningen pr 1. januar 1977–2020 [BEDST1]. http://bank.stat.gl/pxweb/da/Greenland/Greenland__BE__BE01__BE0120/BEXST1.PX?rxid=BEXST116-09-2020%2012:01 28 (2020)

- [20].Jette Elbrønd MJ, Nielsen LM, Wilcke T. KOL - DSAM vejledninger, kvalitetssikring af opfølgning og behandling. 2017. https://vejledninger.dsam.dk/kol/?mode=visKapitel&cid=1054&gotoChapter=1054.

- [21].Mercado N, Ito K, Barnes PJ. Accelerated ageing of the lung in COPD: new concepts. Thorax. 2015;70(5):482–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Ospina MB, Voaklander D, Senthilselvan A, et al. Incidence and prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among aboriginal peoples in Alberta, Canada. PloS One. 2015;10(4):e0123204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Backe MB, Pedersen ML. Prevalence, incidence, mortality, and quality of care of diagnosed diabetes in Greenland. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2020;160:107991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Fuseini H, Newcomb DC. Mechanisms driving gender differences in asthma. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2017;17(19). DOI: 10.1007/s11882-017-0686-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Pedersen ML, Rolskov A, Jacobsen JL, et al. Frequent use of primary health care service in Greenland: an opportunity for undiagnosed disease case-finding. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2012;71(18431). DOI: 10.3402/ijch.v71i0.18431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Reddel HK, Valenti L, Easton KL, et al. Assessment and management of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Australian general practice. Aust Fam Physician. 2017;46(6):413–419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Lim S, Lam DC-L, Muttalif AR, et al. Impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in the Asia-Pacific region: the EPIC Asia population-based survey. Asia Pac Fam Med. 2015;14(4). DOI: 10.1186/s12930-015-0020-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]