Abstract

Background/Aims

Patients with diabetes mellitus (DM) often suffer from gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms, but these correlate poorly to established objective GI motility measures. Our aim is to perform a detailed evaluation of potential measures of gastric and small intestinal motility in patients with DM type 1 and severe GI symptoms.

Methods

Twenty patients with DM and 20 healthy controls (HCs) were included. GI motility was examined with a 3-dimensional-Transit capsule, while organ volumes were determined by CT scans.

Results

Patients with DM and HCs did not differ with regard to median gastric contraction frequency (DM 3.0 contractions/minute [interquartile range {IQR}, 2.9-3.0]; HCs 2.9 [IQR, 2.8-3.1]; P = 0.725), amplitude of gastric contractions (DM 9 mm [IQR, 8-11]; HCs 11 mm (IQR, 9-12); P = 0.151) or fasting volume of the stomach wall (DM 149 cm3 [IQR, 112-187]; HCs 132 cm3 [IQR, 107-154]; P = 0.121). Median gastric emptying time was prolonged in patients (DM 3.3 hours [IQR, 2.6-4.6]; HCs 2.4 hours [IQR, 1.8-2.7]; P = 0.002). No difference was found in small intestinal transit time (DM 5 hours [IQR, 3.7-5.6]; HCs 4.8 hours [IQR, 3.9-6.0]; P = 0.883). However, patients with DM had significantly larger volume of the small intestinal wall (DM 623 cm3 [IQR, 487-766]; HCs 478 cm3 [IQR, 393-589]; P = 0.003). Among patients, 13 (68%) had small intestinal wall volume and 9 (50%) had gastric emptying time above the upper 95% percentile of HCs.

Conclusion

In our study, gastric emptying time and volume of the small intestinal wall appeared to be the best objective measures in patients with DM type 1 and symptoms and gastroenteropathy.

Keywords: Diabetes mellitus, Diabetic neuropathies, Gastric emptying, Gastrointestinal motility, Organ size

Introduction

Gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms are common in patients with diabetes mellitus (DM).1 Their severity ranges from mild discomfort to recurrent vomiting, chronic nausea, abdominal pain, diarrhea, or constipation.1,2 Severe GI symptoms are associated with reduced quality of life and cause significant burden on the healthcare system.3 Diabetic dysmotility can affect all segments of the GI tract and specific symptoms do not correlate well with the underlying pathophysiology.4 Autonomic neuropathy of the extrinsic vagal fibers and the intrinsic enteric nervous system is considered the primary cause of dysmotility in DM. Unfortunately, the autonomic and enteric nervous systems are difficult to evaluate in vivo. Although tests of cardiovascular function are used as proxy for GI neuropathy, results correlate poorly with GI symptoms.5,6

Patients with symptoms attributed to the upper GI tract will usually undergo gastric emptying tests. The gold standard is gastric emptying scintigraphy, in which a standardized radiolabeled meal is tracked 30 minutes after ingestion and then every hour for at least 4 hours.7 Limitations of this method include: high cost, radiation exposure, and poor correlation to symptoms.8,9 The wireless motility capsule (WMC) overcomes some of these limitations. It allows minimally invasive, ambulatory, radiation-free, and pan-enteric assessment of total and regional GI transit times.4,10-12 However, symptoms of gastroparesis, such as nausea, vomiting, bloating, and early satiety, show uncertain correlation to transit times found with the WMC.11,12 It is therefore plausible that other parameters than gastric emptying time and intestinal transit times should be considered as future diagnostic tests of GI dysfunction in DM.

With the Motilis 3-dimensional (3D)-Transit system (Motilis Medica SA, Lausanne, Switzerland) an electromagnetic capsule is followed as it traverses the GI tract. Like the WMC, the 3D-Transit provides ambulatory assessment of gastric emptying, small intestinal transit time, and colonic transit time.13-15 Because the 3D-Transit detects the exact anatomical position and orientation of the capsule at a sampling rate of 5-10 per second, the method allows detailed description of contraction parameters. Recent development of the software for post processing of data now provides information not only on the frequency, but also on the amplitude of gastric contractions.

Earlier studies have found increased small intestinal volume in diabetic rats.16-18 In humans, small intestinal volume can be measured from a low-dose CT scan or by MRI. In spite of this, gastric and small intestinal volumes have received little attention as measures of diabetic enteropathy.

In the present explorative study, we aim at comparing (1) the basic gastric contraction rate, (2) the amplitude of gastric contractions, (3) gastric emptying time, (4) volume of the stomach, (5) small intestinal transit time, and (6) volume of the small intestine in patients with DM and GI symptoms with those of healthy controls (HCs).

Materials and Methods

Subjects

Between September 2015 and May 2019, 20 adult patients (11 males; mean age, 46.5 [standard deviation {SD}, 12.2]) with DM type 1 and severe GI symptoms and 20 age and sex-matched HCs (11 males; mean age, 45.0 [SD, 10.6]) were enrolled. The patients had been referred to our tertiary clinic because of chronic GI symptoms attributed to long-term diabetes. No formal symptom-based definition of diabetic gastroenteropathy exists, but all patients were evaluated by an experienced specialized neurogastroenterologist (M.W.K.) and screened for the present study if their symptoms were considered severe enough to warrant further clinical evaluation. All patients had symptoms which could be attributed to the upper GI tract but most also had symptoms usually originating from the colon. All participants signed a written informed consent before enrollment and all patients had a total score in Gastroparesis Cardinal Symptom Index (GCSI) above 10.19,20

Exclusion criteria were: previous intestinal resection or other major abdominal surgery, other diseases affecting GI function, and severely reduced kidney or cardiac function. Due to radiation exposure incurred by CT scans, fertile women had to present a negative pregnancy test before participating. All medications affecting the GI function were paused at least 48 hours before each investigation. As a part of the standard diagnostic workup, all patients had been evaluated with gastroscopy, standard blood and stool tests for inflammatory bowel disease, celiac disease, lactose intolerance, thyroid disease, malabsorption, and GI infection. Also, on clinical indication, gastric emptying scintigraphy had been performed in 14 patients.

The study was conducted according to the Helsinki declaration and European Community rules of good clinical practice. Approval was obtained from the scientific ethics committee (reference: 1-10-72-54-15) and the medical authorities (reference: 2016101143).

Assessment of Diabetic Autonomic Neuropathy

Cardiac autonomic neuropathy (CAN) was assessed using the handheld medical device Vagus (Medicus Engineering, Aarhus, Denmark). CAN is routinely used as a surrogate marker of autonomic neuropathy in patients with diabetes. CAN was defined by using gold standard cardiovascular reflex tests including the heart response: to standing from a supine position, to deep breathing, and to forceful expiration (normal cardiovascular reflex tests, no CAN; one abnormal cardiovascular reflex test, early CAN; and autonomic dysfunction, 2 or 3 abnormal cardiovascular reflex tests, manifest CAN). Age-dependent cutoffs were used to define abnormal results.21 Twenty-four hour blood pressure had been recorded on clinical request. Attenuated decrease (dip) in the nocturnal blood pressure of less than 10% was considered abnormal. Periphery neuropathy was assessed with monofilament according to international guidelines.22 Furthermore, patients were asked about their sensation of hypoglycemia. The answers were categorized as “preserved,” “poor,” or “no sensation.”

Assessment of Gastric Contraction Frequency, Amplitude, and Emptying Time

The 3D-Transit system is a wireless electromagnetic capsule system used for detailed assessment of GI motility patterns and transit times.13-15,23,24 After an overnight fast, the extracorporeal detector was mounted and the electromagnetic capsule (21.5 mm × 8.3 mm, 1.6 g/cm3) ingested with a standardized meal (2 granola bars: total 250 kcal; protein 3.8 g, fat 7.4 g, and carbohydrate 42 g; and 300 mL of water). The detector belt was worn from ingestion until capsule expulsion from the body or end of battery power. However, subjects under study were allowed to remove the detector briefly when showering. They were not allowed to do heavy exercise, or stay closer than 40 cm to a computer during the study. Otherwise, all normal daily routines could be followed. Patients wearing an insulin pump or blood glucose sensor were hospitalized and had the device removed the day before starting the 3D-Transit examination. This precaution was taken to avoid interaction between the 3D-Transit system and the medical devices. Blood glucose was adjusted with manual insulin injections supervised by an experienced endocrinologist (S.L.). The blood glucose was targeted to be within the interval of 5-10 mmol/mL.

With 3D-Transit, the electromagnetic field emitted by the capsule is registered by the detector and data is converted into coordinates (x, y, z, ɸ, and θ) via an iterative algorithm. The x, y, and z coordinates define spatial 3D position while ɸ, and θ express the angular position of the capsule to the detector. The lifetime of the battery within the capsule is approximately 60 hours.

Recordings were analyzed in a custom developed software to calculate regional transit times and contractility patterns.13 As previously described in detail, gastric emptying and small intestinal transit times were defined from region-specific contraction frequencies and the changes in position of the capsule on 2D plots.13 All gastric contractions were manually marked to calculate frequency, amplitude, and percentage of time with visible gastric contractions. Analysis of gastric contractions was restricted to the first 6 hours after the index meal because subjects were allowed to eat after this period of time. All analyses were independently made by 2 investigators (M.W.K. and A.M.H.). In case of disagreement, the mean value was used.

Volumes of the Stomach and Small Intestine

A low-dose high-resolution CT scan with intravenous contrast (Visipaque 270 mg/mL; 2 mL/kg body weight with a maximum of 180 mL) was performed after a minimum of 6 hours fasting for food and a minimum of 2 hours for liquids. The scan field covered an area from the left cardiac ventricle to the lower part of the anal canal allowing assessment of abdominal organ volumes as well as gas and fluid volumes within the gut. Data analysis was performed in PMOD version 3.6 (PMOD Technologies, Zurich, Switzerland). Regions of interest were manually defined on each slice of the CT scan. Volumes-of-interest were computed by fusing all the regions of interest. Water/fluid was defined by Hounsfield unit < 30 for water and < –200 Hounsfield units for gas.25 The investigator making all analyses (M.W.K.) was blinded to clinical category of the test subjects. Part of the volume data will be presented elsewhere.26

Assessment of Gastrointestinal Symptoms

GI symptoms were assessed by the following 3 validated questionnaires: (1) Symptoms from the upper GI tract were quantified by the 20 item Patient Assessment of Upper Gastrointestinal Symptom Severity Index (PAGI-SYM) questionnaire.20 The PAGI-SYM questionnaires consists of 6 subscales: heartburn/regurgitation, nausea/vomiting, fullness/early satiety, bloating, upper abdominal pain, and lower abdominal pain, each ranging from 0 (minimum) to 5 (maximum severity). (2) Symptoms of gastroparesis were rated by the GCSI, which is a 9-item score derivate from PAGI-SYM.19 (3) The severity of constipation was quantified by the 8 item Constipation Score System.27

Statistical Methods

Three-dimensional Transit data were prepared for analysis by a custom-made file in MATLAB version 2018b (MathWorks Inc, Natick, MA, USA). Statistical analysis was performed in Stata statistical software version 2013 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA). Graphic illustrations were performed using Prism 8 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Parametric data were compared with two-way unpaired Student’s t test with Welch correction for unequal variance. Nonparametric data were compared by means of Wilcoxon Mann-Whitney U test. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Among 128 patients with DM referred to our unit because of GI symptoms, 20 fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were willing to participate. Reasons for non-participation were: concomitant disease (n = 65), concomitant medication (n = 27), previous surgery (n = 4), uncertain symptoms (n = 7), declined study participation (n = 8), and non-compliance (n = 4). A few patients had more than one reason for non-participation. Patients’ demography is displayed in Table 1 and clinical characteristics obtained from the questionnaires in Table 2. Results from the diabetes neuropathy test are shown in Tables 1 and 3.

Table 1.

Demographics and Clinical Characteristics of Patients and Healthy Controls Included in the Study

| Demographics | Patients with DM type 1 | Healthy controls | P-values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participants (M/F) | 11/9 | 11/9 | 1.000 |

| Age (yr) | 46.5 (12.2) | 45.0 (10.6) | 0.675 |

| Duration of GI symptoms (mo) | 42.0 (30.7) | ||

| Duration of diabetes (yr) | 27.3 (12.7) | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.3 (22.1-26.9) | 26.3 (24.2-27.1) | 0.083 |

| Glomerular filtration rate (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 89.4 (25.6) | 97.3 (18.8) | 0.304 |

| Urine albumine-creatinine ratio | 10.5 (5.0-33.0) | ||

| Hemoglobin A1C (%) | 8.4 (1.8) | ||

| Fast acting insulin (IU/kg per day) | 24.3 (8.9) | ||

| Slow-acting insulin (IU/kg per day) | 25.2 (14.9) | ||

| Insulin pump | 5 (25%) | ||

| Insulin sensor | 6 (30%) | ||

| Diabetic eye disease | 12 (60%) | ||

| Heart disease | 2 (11%) | ||

| Lack of noctunal blood pressure dip | 4 (20%) |

DM, diabetes mellitus; M, male; F, female; GI, gastrointestinal; BMI, body mass index; IQR, interquartile range.

Data are presented as mean (SD), medians (interquartile range [IQR]), or n (%).

Table 2.

Clinical Characteristics of the Questionnaires Patients and Healthy Controls Included in the Study

| Clinical questionnaires | Patients with DM type 1 | Healthy controls | P-values |

|---|---|---|---|

| PAGI-SYM | 35.6 (22.9) | 5.6 (6.6) | < 0.001 |

| GCSI | 17.85 (9.27) | 3.1 (3.8) | < 0.001 |

| Sub-score | |||

| Bloating | 6 (4.5-7.5) | 1 (0.0-2.5) | < 0.001 |

| Nausea/vomiting | 2 (0.0-4.0) | 0 (0.0-0.0) | < 0.001 |

| Fulness/early satiety | 9 (4.5-14.5) | 0.5 (0.0-2.0) | < 0.001 |

| CSS | 10 (4.9) | 4.4 (3.2) | < 0.001 |

DM, diabetes mellitus; PAGI-SYM, patient assessment of upper gastrointestinal symptom severity index; GCSI, gastroparesis cardinal symptom index; CSS, constipation scoring system.

Data are presented as mean (SD) or medians (interquartile range [IQR]).

Table 3.

Diagnostic Tests From Each Patient

| Duration of DM (yr) | Gastric emptying > 95% percentile of healthy | Gastric wall volume > 95% percentile of healthy | Small intestinal wall volume > 95% percentile of healthy | Prolonged gastric emptying (scintigraphy) | Cardiac autonomic neuropathy score ≥ 2 | Periphery neuropathy | Sensation of hypoglycemia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | No | Yes | Yes | - | - | Yes | No |

| 11 | Yes | No | No | Normal | No | No | Poor |

| 12 | Yes | No | Yes | Prolonged | - | No | Yes |

| 15 | Yes | Yes | Yes | - | Yes | - | - |

| 15 | No | No | Yes | Normal | No | No | Yes |

| 18 | No | No | No | Normal | No | No | Yes |

| 19 | No | No | Yes | - | No | No | Yes |

| 21 | - | Yes | Yes | - | No | No | - |

| 22 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Prolonged | No | Yes | - |

| 28 | No | No | Yes | Normal | Yes | No | Yes |

| 28 | Yes | - | - | Normal | Yes | Yes | No |

| 32 | Yes | No | No | Normal | No | No | Poor |

| 33 | No | No | Yes | - | No | No | Yes |

| 34 | Yes | No | No | Normal | No | Yes | No |

| 36 | Yes | No | No | Normal | No | Yes | Poor |

| 37 | No | Yes | Yes | Normal | No | Yes | Yes |

| 40 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Prolonged | Yes | - | Poor |

| 45 | - | No | Yes | - | - | No | Yes |

| 45 | No | Yes | Yes | Prolonged | No | - | Yes |

| 49 | No | No | No | Normal | Yes | Yes | No |

| 9 (50%) | 7 (37%) | 13 (68%) | 4 (29%) | 5 (29%) | 7 (41%) | 8 (47%) |

DM, diabetes mellitus.

Normal values are highlighted in gray. “-” marks missing value. All patients with prolonged gastric emptying at scintigraphy also had abnormally large small intestine.

Gastric Contractions

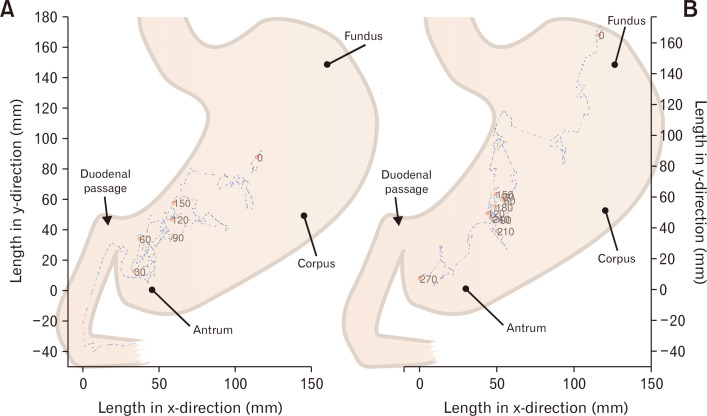

Median time with recognizable contractions of the stomach was 92% (interquartile range [IQR], 79-94) in patients with DM and 92% (IQR, 78-97) in HCs (P = 0.501). The median frequency of gastric contractions was 3.0 contractions per minute (CPM) (IQR, 2.9-3.0) in patients with DM and 2.9 CPM (IQR, 2.8-3.1) in HCs (P = 0.725). The median amplitude of capsule rotation was 27 degrees (IQR, 19-41) in patients with DM and 31 degrees (IQR, 23-42) in HCs (P = 0.736). The median amplitude of change in position of the capsule was 9 mm (IQR, 8-11) in patients with DM and 11 mm (IQR, 9-12) in HCs (P = 0.151). In 2 (10%) patients with DM the amplitude (position) of gastric contractions was below the lower 5% limit of HCs. Examples of intragastric movements in a patient with DM and in a HC are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Intragastric movements of the 3-dimensional Transit electromagnetic capsule. Recordings from a healthy volunteer (A) and a patient with diabetes (B). Red dots show every 30 minute intervals position in the stomach.

Gastric Emptying Time

Median gastric emptying time was 3.3 hours (IQR, 2.6-4.6) in patients with DM and 2.4 hours (IQR, 1.8-2.7) in HCs (P = 0.002). In 9 (50%) of 18 patients, gastric emptying time was beyond the upper 95% limit of the HC group (Table 3).

Gastric Volume

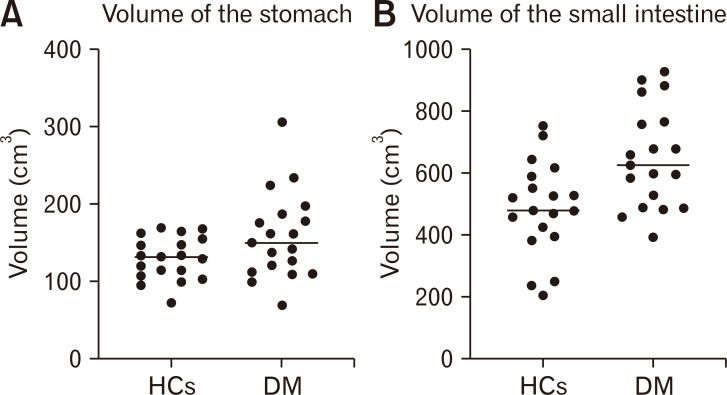

There was no difference in gastric wall volume between patients with DM and HCs (Fig. 2 and Table 4). In 7 of 19 patients (37%), the volume of the gastric wall was above the upper 95% percentile of HCs. The amount of fluid in the stomach and the total volume of the stomach including both the wall and luminal content did not differ significantly between the 2 groups (Table 4).

Figure 2.

Volumes of the gastric (A) and small intestinal walls (B) assesses with CT scans. The horizontal line shows the median. Diabetes patients had a significantly larger volume of the small intestinal wall (P = 0.003) but not of the stomach (P = 0.121). HCs, healthy controls; DM, patients with diabetes mellitus.

Table 4.

Gastric and Small Intestinal Volumes

| Gastrointestinal volumes (cm3) | Healthy controls | Patients with diabetes | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Volume of the stomach including luminal content | 182 (151-246) | 162 (138-193) | 0.078 |

| Volume of the gastric wall | 131 (107-154) | 149 (112-187) | 0.121 |

| Volume of fluid in the stomach | 31 (17-56) | 37 (24-84) | 0.293 |

| Volume of the small intestine including gas and luminal content | 713 (639-899) | 927 (829-1051) | 0.002 |

| Volume of the small intestine wall | 478 (393-589) | 623 (487-766) | 0.003 |

| Volume of fluid in the small intestine | 209 (165-236) | 227 (191-288) | 0.082 |

| Volume of gas in the small intestine | 95 (40-150) | 83 (56-139) | 0.872 |

Among patients with diabetes, 7 (37%) had a total small intestinal volume and 4 (21%) had a total gastric volume above the upper 95% percentile of healthy controls.

Data are presented as medians (interquartile range [IQR]).

Small Intestinal Transit Time

Median small intestinal transit time was 5.0 hours (IQR, 3.7-5.6) in patients with DM and 4.8 hours (IQR, 3.9-6.0) in HCs (P = 0.883). In 2 of 19 patients (11%), small intestinal transit time was above the upper 95% limit of the HC group.

Volume of the Small Intestine

As illustrated in Figure 2 and seen in Table 4, patients with DM had significantly larger volume of the small intestinal wall. In 13 of 19 patients (68%), the small intestinal wall volume was above the upper 95% limit of that in HCs (Table 3). The total small intestinal volume including both the wall and luminal content was likewise significantly larger in patients with diabetes. DM patients had more fluid in the small intestine compared to HCs, but the difference did not reach statistical significance (Table 4).

Questionnaires

In all questionnaires, patients with DM scored significantly higher than HCs (Table 2). Within the group of patients with DM, there was no association between any of the scores and the objective measures described above.

Discussion

Symptoms of gastric and small intestinal dysfunction are common among patients with DM. In the present explorative study, we found no differences in basic gastric contraction frequency or the amplitude of gastric contractions when comparing patients with DM and HCs. Gastric emptying time, but not small intestinal transit time, was longer in patients with DM than in HCs. The volume of the small intestine was significantly larger in patients than in HCs. Hence, the main implications of our study are that gastric emptying time and small intestinal wall volume seem to be the most sensitive objective measures in patients with DM type 1 and symptoms of dysmotility within the upper GI tract.

Diabetic Enteropathy

Because of the non-specific symptoms, diagnosis of diabetic gastroenteropathy is difficult. The pathophysiology behind diabetic gastroenteropathy is incompletely understood. Enteric and vagal neuropathy, depletion of interstitial cells of Cajal, reduced function of smooth muscle cells, and hyperglycemia may all contribute to gastroenteropathy.28-32 The GI tract is innervated by sympathetic, parasympathetic, and enteric nerves. Animal studies have found morphological changes in the vagal nerve and segmental demyelination as well as axonal degeneration of the myenteric and submucosal plexus.29-31 Products of glycation may cause neural damage and reduce neuronal nitric oxide synthase.33 Since neuronal nitric oxide synthase is reduced in early stage diabetic rats while cholinergic nerves are affected later, it has been suggested that inhibitory neurons are affected by DM before excitatory.34 Both factors increase the risk of GI complications. Diabetic gastroparesis is usually diagnosed after 10 years of disease.35 In our study population, the mean duration of diabetes was more than 20 years and hemoglobin A1C was relatively high.

Standard Tests of Autonomic and Peripheral Neuropathy

Earlier studies have shown that autonomic, but not peripheral somatic neuropathy correlates with prolonged gastric emptying.8,36 Hence, CAN is commonly used as a surrogate for enteric neuropathy in patients with DM. CAN is easily assessed with 3 different cardiovascular reflex tests sometimes in combination with a 24-hour blood pressure measurement, but unfortunately the correlation with GI symptoms remains poor.5,8 In the present study, 29% patients with symptoms of diabetic enteropathy had manifest CAN. Bharucha et al37 showed in 78 patients with DM type 1, that decreased heart rate variability in the deep breathing test and not the response to standing or the Valsalva maneuver, correlated with prolonged gastric emptying. Detailed heartrate variability analysis was not part of the primary endpoint and the possible association to prolonged gastric emptying will be investigated in a future study.

Gastric Contractions

Comparing the basic gastric contraction frequency, the amplitude of contractions and the time with identifiable contractions, we found no difference between patients with DM and HCs. Previous studies of the myoelectrical activity assessed with electrogastrography have shown discoordinated activity in patients with DM. This contrasts our results, but electrical impulses from the surface of the body may not entirely correlate with gastric contractions.38 Also, in contrast to our data, a study of 113 subjects evaluated with the WMC found a decreased number of contractions per hour in patients with DM. The reduced number of contractions was associated with prolonged gastric emptying.39 The difference to our study may be due to a type II error caused by the smaller number of patients in our study.

We used the electromagnetic 3D-Transit system to describe gastric motility in detail. The 3D-Transit capsule is very sensitive as even millimeters of displacements in its position or a few degrees of rotation will be registered. Capsule location in the stomach fundus may change the contraction frequency. However, brief stays in the fundus were included in the total gastric contraction analysis, as the stays were short lasting and estimated without influence of the contractility pattern. Theoretically, changes in position are more sensitive than pressure changes, especially in large hollow organs. Hence, we expected that the 3D-Transit would add new and valuable information about gastric contractions not available with other methods. However, median values for the frequency of gastric contractions were almost identical among patients with DM and HCs. The number of subjects included in the present study was too small to draw definite conclusions, but our data may suggest the basic frequency of myoelectrical activity generated by the smooth muscle cells was intact. The amplitude of movements of the capsule was lower in patients with DM than in HCs, but the difference did not reach statistical significance, which may be related to the relatively small sample. Previous studies have shown that DM causes impaired accommodation of the stomach, which may contribute to GI symptoms even if gastric contractions remain unaltered.40

Gastrointestinal Transit Times

Patients with diabetic enteropathy have pan-enteric dysmotility and assessment of regional GI transit times is part of the clinical evaluation at many centers. The commonly used WMC is a radiation-free, ambulatory and minimal invasive method that has been validated against scintigraphy and the 13C breath test.41 The 3D-Transit system is not yet as well established as the WMC. However, gastric emptying and small intestinal transit time obtained by magnet tracking have been tested together with endoscopic video capsule (PillCam) and gastric emptying scintigraphy.24,42 The electromagnetic capsule for 3D-Transit is smaller (21.5 mm × 8.3 mm) than the WMC (26.8 mm × 11.7 mm) but normative data for regional transit times with the 2 methods are very similar. With the WMC, gastric emptying was more affected in DM than the small intestinal transit time.43 Thus, the previous studies with the WMC support the findings of the present study.

Volume of the Small Intestine

In previous studies, rats with DM had hyperplasia of the small intestine.16-18 This is probably mainly due to mucosal hypertrophy.44,45 In our study, patients with diabetes had a 34% increase of small intestinal wall volume compared to HCs. We found it noteworthy that 68% of patients with DM and symptoms of upper GI dysmotility had volumes of the small intestinal wall above the upper 95% limit of the HCs. Thus, assessment of small intestinal wall volume holds promise as a more sensitive marker of diabetic enteropathy than other existing methods. Unfortunately, assessment of intestinal volumes is time consuming and new techniques for this are warranted.

Limitations

The present study is an explorative study including 40 study participants in total. The small study size increases the risk of type II errors. Thus, a larger study is needed to confirm our findings. Furthermore, in future studies a control group of patients recently diagnosed with DM could be included. The patients included in the present study were selected from the much larger group of patients referred to our unit for assessment of diabetic enteropathy. This may have caused selection bias and therefore affect the external validity of the study findings. The main reasons for excluding patients from the study were use of medication influencing gut motility and nephropathy.

Gastric emptying scintigraphy was not part of our study protocol, but 14 patients had the procedure performed on clinical indications. A direct comparison between 3D-Transit or volume assessed by CT and gastric emptying scintigraphy would be highly relevant, as the latter is considered the gold standard test for gastric emptying. Such comparison was however beyond the scope of the present study. There was discrepancy between results from gastric emptying scintigraphy and the 3D-Transit capsule. Scintigraphy was not performed on the same days as the 3D-Transit study. Symptoms of diabetic enteropathy may fluctuate and there is intersubjective variation in objective methods used. Whether this is the cause of the discrepancy found or 3D-Transit is more sensitive than gastric emptying scintigraphy needs to be addressed in larger studies. Finally, all patients in the present study had DM type 1 and results may not be directly applicable to patients with DM type 2.

In conclusion, in this present study the frequency of gastric contractions was unaffected by DM. Among the parameters studied, gastric emptying time and volume of the small intestine seem to provide the most sensitive objective measures in patients with DM type 1 and symptoms attributed to the upper GI tract.

Footnotes

Financial support: This article was financial supported by; The Novo Nordisk Foundation (13159), The Lundbeck Foundation (R230-2016-2306), Højmosegaard Legatet, The A.P. Møller Foundation for the Advancement of Medical Science, Holger Rabitz og Hustru Doris Mary født Phillips Legat, Loge nr 73, Svend Fældings Humanitære Fond, Torben og Alice Frimodts Fond, The Foundation for Medical Students University of Copenhagen and Wilhelm Frank og Angelina Franks Mindelegat.

Conflicts of interest: Vincent Schlageter is co-owner of Motilis Medica SA, he took part in the technical terms of improving the software for gastric analysis. Jesper Fleischer is the co-inventor of Vagus. Mette W Klinge, Nanna Sutter, Esben B Mark, Anne-Mette Haase, Per Borghammer, Sten Lund, Karoline Knudsen, Asbjørn M Drewes, and Klaus Krogh have no competing interests.

Author contributions: Mette W Klinge: contribution to the concept and design, analyzing of data, interpretation of data, and drafting the article; Nanna Sutter: practical work during study examinations and data analysis; Esben B Mark: data analysis, critical reviewing for important intellectual content; Anne-Mette Haase: contribution to the concept and design, data analysis, and critical reviewing for important intellectual content; Per Borghammer and Sten Lund: contribution to the concept and design, interpretation of data, and critical reviewing for important intellectual content; Vincent Schlageter: data analysis, interpretation of data, and critical reviewing for important intellectual content; Jesper Fleischer: interpretation of data and critical reviewing for important intellectual content; Karoline Knudsen: data analysis and critical reviewing for important intellectual content; Asbjørn M Drewes: interpretation of data and critical reviewing for important intellectual content; and Klaus Krogh: contribution to the concept and design, interpretation of data, drafting the article, and critical reviewing for important intellectual content. All authors final approved the manuscript before submission.

References

- 1.Du YT, Rayner CK, Jones KL, Talley NJ, Horowitz M. Gastrointestinal symptoms in diabetes: prevalence, assessment, pathogenesis, and management. Diabetes Care. 2018;41:627–637. doi: 10.2337/dc17-1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bytzer P, Talley NJ, Leemon M, Young LJ, Jones MP, Horowitz M. Prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms associated with diabetes mellitus: a population-based survey of 15.000 adults. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:1989–1996. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.16.1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DiBaise JK, Patel N, Noelting J, Dueck AC, Roarke M, Crowell MD. The relationship among gastroparetic symptoms, quality of life, and gastric emptying in patients referred for gastric emptying testing. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016;28:234–242. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farmer AD, Pedersen AG, Brock B, et al. Type 1 diabetic patients with peripheral neuropathy have pan-enteric prolongation of gastrointestinal transit times and an altered caecal pH profile. Diabetologia. 2017;60:709–718. doi: 10.1007/s00125-016-4199-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clouse RE, Lustman PJ. Gastrointestinal symptoms in diabetic patients: lack of association with neuropathy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1989;84:868–872. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Punkkinen J, Färkkilä M, Mätzke S, et al. Upper abdominal symptoms in patients with type 1 diabetes: unrelated to impairment in gastric emptying caused by autonomic neuropathy. Diabet Med. 2008;25:570–577. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2008.02428.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abell TL, Camilleri M, Donohoe K, et al. Consensus recommendations for gastric emptying scintigraphy: a joint report of the American neurogastroenterology and motility society and the society of nuclear medicine. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:753–763. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Darwiche G, Almér LO, Björgell O, Cederholm C, Nilsson P. Delayed gastric emptying rate in type 1 diabetics with cardiac autonomic neuropathy. J Diabetes Complications. 2001;15:128–134. doi: 10.1016/S1056-8727(00)00143-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vijayvargiya P, Jameie-Oskooei S, Camilleri M, Chedid V, Erwin PJ, Murad MH. Association between delayed gastric emptying and upper gastrointestinal symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut. 2019;68:804–813. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-316405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang YT, Mohammed SD, Farmer AD, et al. Regional gastrointestinal transit and pH studied in 215 healthy volunteers using the wireless motility capsule: influence of age, gender, study country and testing protocol. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;42:761–772. doi: 10.1111/apt.13329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hasler WL, May KP, Wilson LA, et al. Relating gastric scintigraphy and symptoms to motility capsule transit and pressure findings in suspected gastroparesis. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2018;30:e13196. doi: 10.1111/nmo.13196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arora Z, Parungao JM, Lopez R, Heinlein C, Santisi J, Birgisson S. Clinical utility of wireless motility capsule in patients with suspected multiregional gastrointestinal dysmotility. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60:1350–1357. doi: 10.1007/s10620-014-3431-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haase AM, Gregersen T, Schlageter V, et al. Pilot study trialling a new ambulatory method for the clinical assessment of regional gastrointestinal transit using multiple electromagnetic capsules. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2014;26:1783–1791. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fynne L, Worsøe J, Gregersen T, Schlageter V, Laurberg S, Krogh K. Gastrointestinal transit in patients with systemic sclerosis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:1187–1193. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2011.603158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gregersen T, Haase AM, Schlageter V, Gronbaek H, Krogh K. Regional gastrointestinal transit times in patients with carcinoid diarrhea: assessment with the novel 3D-transit system. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;21:423–432. doi: 10.5056/jnm15035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schedl HP, Schwartz J, Wilson HD. Increased intestinal growth in the streptozotocin-diabetic rat occurs prior to changes in hormone secretion. Digestion. 1988;39:137–143. doi: 10.1159/000199617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao J, Yang J, Gregersen H. Biomechanical and morphometric intestinal remodelling during experimental diabetes in rats. Diabetologia. 2003;46:1688–1697. doi: 10.1007/s00125-003-1233-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sha H, Zhao JB, Zhang ZY, et al. Effect of kaiyu qingwei jianji on the morphometry and residual strain distribution of small intestine in experimental diabetic rats. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:7149–7154. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i44.7149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Revicki DA, Rentz AM, Dubois D, et al. Gastroparesis cardinal symptom index (GCSI): development and validation of a patient reported assessment of severity of gastroparesis symptoms. Qual Life Res. 2004;13:833–844. doi: 10.1023/B:QURE.0000021689.86296.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rentz AM, Kahrilas P, Stanghellini V, et al. Development and psychometric evaluation of the patient assessment of upper gastrointestinal symptom severity index (PAGI-SYM) in patients with upper gastrointestinal disorders. Qual Life Res. 2004;13:1737–1749. doi: 10.1007/s11136-004-9567-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Andersen ST, Witte DR, Fleischer J, et al. Risk factors for the presence and progression of cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy in type 2 diabetes: addition-Denmark. Diabetes Care. 2018;41:2586–2594. doi: 10.2337/dc18-1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Apelqvist J, Bakker K, van Houtum WH, Scapher NC. Practical guidelines on the management and prevention of the diabetic foot: based upon the international consensus on the diabetic foot (2007) prepared by the international working group on the diabetic foot. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2008;24(suppl 1):S181–S187. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haase AM, Fallet S, Otto M, Scott SM, Schlageter V, Krogh K. Gastrointestinal motility during sleep assessed by tracking of telemetric capsules combined with polysomnography - a pilot study. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2015;8:327–332. doi: 10.2147/CEG.S91964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Knudsen K, Haase AM, Fedorova TD, et al. Gastrointestinal transit time in parkinson's disease using a magnetic tracking system. J Parkinson Dis. 2017;7:471–479. doi: 10.3233/JPD-171131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fedorova TD, Seidelin LB, Knudsen K, et al. Decreased intestinal acetylcholinesterase in early parkinson disease: an 11C-donepezil PET study. Neurology. 2017;88:775–781. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klinge MW, Borghammer P, Lund S, et al. Enteric cholinergic neuropathy in patients with diabetes: non-invasive assessment with positron emission tomography. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2020;32:e13731. doi: 10.1111/nmo.13731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Agachan F, Chen T, Pfeifer J, Reissman P, Wexner SD. A constipation scoring system to simplify evaluation and management of constipated patients. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:681–685. doi: 10.1007/BF02056950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Horváth VJ, Vittal H, Lörincz A, et al. Reduced stem cell factor links smooth myopathy and loss of interstitial cells of cajal in murine diabetic gastroparesis. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:759–770. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guo C, Quobatari A, Shangguan Y, Hong S, Wiley JW. Diabetic autonomic neuropathy: evidence for apoptosis in situ in the rat. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2004;16:335–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2004.00524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guy RJ, Dawson JL, Garrett JR, et al. Diabetic gastroparesis from autonomic neuropathy: surgical considerations and changes in vagus nerve morphology. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1984;47:686–691. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.47.7.686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tay SS, Wong WC. Short and long-term induced effects of streptozotocin induced diabetes on the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus nerve in the rat. Acta Anat. 1994;150:274–281. doi: 10.1159/000147630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Frokjaer JB, Andersen SD, Ejskjaer N, Funch-jensen P, Drewes AM, Gregersen H. Impaired contractility and remodeling of the upper gastrointestinal tract in diabetes mellitus type-1. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:4881–4890. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i36.4881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bulc M, Palus K, Dąbrowski M, Całka J. Hyperglycaemia-induced downregulation in expression of nNOS intramural neurons of the small intestine in the pig. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:1681. doi: 10.3390/ijms20071681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Demedts I, Masaoka T, Kindt S, et al. Gastrointestinal motility changes and myenteric plexus alterations in spontaneously diabetic biobreeding rats. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2013;19:161–170. doi: 10.5056/jnm.2013.19.2.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aleppo G, Calhoun P, Foster NC, et al. Reported gastroparesis in adults with type 1 diabetes (T1D) from the T1D exchange clinic registry. J Diabetes Complications. 2017;31:1669–1673. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2017.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Merio R, Festa A, Bergmann H, et al. Slow gastric emptying in type 1 diabetes: relation to autonomic and peripheral neuropathy, blood glucose and glycemic control. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:419–423. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.3.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bharucha AE, Batey-Schaefer B, Cleary PA, et al. Delayed gastric emptying is associated with early and long-term hyperglycemia in type 1 diabetes mellitus. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:330–339. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yin J, Chen JDZ. Electrogastrography: methodology, validation and applications. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2013;19:5–17. doi: 10.5056/jnm.2013.19.1.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kloetzer L, Chey WD, McCallum RW, et al. Motility of the antroduodenum in healthy and gastroparetics characterized by wireless motility capsule. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22:527–533. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chedid V, Brandler J, Vijayvargiya P, Park SY, Szarka LA, Camilleri M. Characterization of upper gastrointestinal symptoms, gastric motor functions, and associations in patients with diabetes at a referral center. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114:143–154. doi: 10.1038/s41395-018-0234-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hasler WL. The use of SmartPill for gastric monitoring. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;8:587–600. doi: 10.1586/17474124.2014.922869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Worsøe J, Fynne L, Gregersen T, et al. Gastric transit and small intestinal transit time and motility assessed by a magnet tracking system. BMC Gastroenterol. 2011;11:145. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-11-145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rouphael C, Arora Z, Thota PN, et al. Role of wireless motility capsule in the assessment and management of gastrointestinal dysmotility in patients with diabetes mellitus. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2017;29:e13087. doi: 10.1111/nmo.13087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fischer KD, Dhanvantari S, Drucker DJ, Brubaker PL. Intestinal growth is associated with elevated levels of glucagon-like peptide 2 in diabetic rats. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:E815–E820. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1997.273.4.E815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhao M, Liao D, Zhao J. Diabetes-induced mechanophysiological changes in the small intestine and colon. World J Diabetes. 2017;8:249–269. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v8.i6.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]