Abstract

In Escherichia coli, the DnaB helicase forms the basis for the assembly of the DNA replication complex. The stability of DnaB at the replication fork is likely important for successful replication initiation and progression. Single-molecule experiments have significantly changed the classical model of highly stable replication machines by showing that components exchange with free molecules from the environment. However, due to technical limitations, accurate assessments of DnaB stability in the context of replication are lacking. Using in vitro fluorescence single-molecule imaging, we visualise DnaB loaded on forked DNA templates. That these helicases are highly stable at replication forks, indicated by their observed dwell time of ∼30 min. Addition of the remaining replication factors results in a single DnaB helicase integrated as part of an active replisome. In contrast to the dynamic behaviour of other replisome components, DnaB is maintained within the replisome for the entirety of the replication process. Interestingly, we observe a transient interaction of additional helicases with the replication fork. This interaction is dependent on the τ subunit of the clamp-loader complex. Collectively, our single-molecule observations solidify the role of the DnaB helicase as the stable anchor of the replisome, but also reveal its capacity for dynamic interactions.

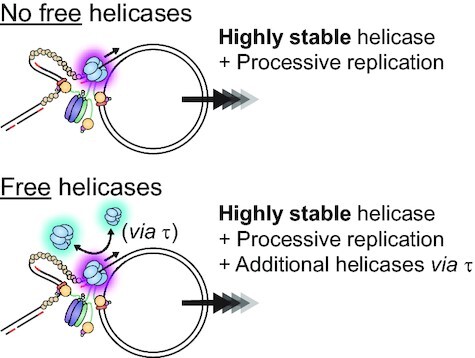

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

Single-molecule observation of the DnaB helicase in E. coli DNA replication shows a single, stably-integrated helicase supports replication, with additional helicases able to interact via available τ subunits.

INTRODUCTION

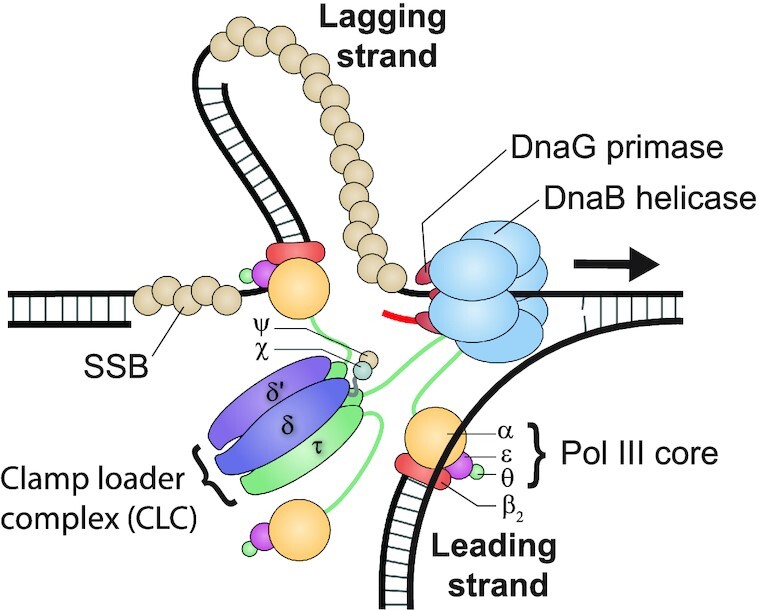

All living organisms depend on the accurate duplication of their genomic DNA to ensure their survival. In every domain of life, this intricate process is fulfilled by a set of co-evolved enzymes collectively known as the replisome. In the model bacterium Escherichia coli, the replisome (Figure 1) consists of twelve separate proteins that assemble on DNA and combine their actions to faithfully copy the circular chromosome (reviewed in (1)). The replicative helicase DnaB plays a key role within the replisome. It is a homo-hexameric, RecA-like ATPase (2) that encircles single-stranded (ss) DNA, on which it hydrolyses ATP or other rNTPs to drive its translocation in the 5′–3′ direction. DnaB unwinds the parental double-stranded (ds) DNA and thereby provides the ssDNA templates for DNA polymerase and primase activity. During replication initiation, the loading of DnaB at the replication origin (oriC) is observed as the key determinant in replisome assembly (reviewed in (3)). In order to be loaded, DnaB must form a tight complex with its helicase-loader protein DnaC, and then be recruited to oriC by the DnaA initiator protein. The DnaC helicase loader destabilises the DnaB hexamer and forms with it a three-tiered, right-handed cracked-ring structure that enables deposition of the helicase onto ssDNA (4–6). Once loaded, the hexameric helicase presents sites for up to two DnaG primase molecules to interact, leading to subsequent ejection of DnaC (7). During replication, two or three helicase-bound primase molecules cooperate to produce short RNA primers required for initiation of DNA polymerase activity (8,9). The DNA polymerase III holoenzyme (Pol III HE) is the replicase responsible for engaging the primers on both the leading and lagging strands and extending them into new DNA. Pol III HE consists of three sub-assemblies: the αϵθ polymerase III core, the clamp loader complex (CLC) and the β2 processivity clamp (10). The CLC hydrolyses ATP to load the β2 clamp onto DNA, which in turn stabilises the Pol III core while it synthesises DNA (11–13). The CLC also acts as the physical bridge between the Pol III cores and DnaB helicase through its multiple τ subunits (14–16).

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the architecture of the E. coli replisome. The DnaB helicase enables the progression of the replisome as it unwinds double-stranded DNA. DnaG primase synthesises short RNA primers (shown in red) on the single-stranded DNA template. The clamp-loader complex (CLC; consisting of δ, δ', ψ, χ and three τ) loads the β2 sliding clamp and the αϵθ polymerase III core onto newly primed sites. The core then synthesises new DNA on both template strands. DNA synthesis occurs continuously on the leading strand and discontinuously on the lagging strand. The CLC tethers the polymerase to the helicase via one τ subunit. Single-stranded DNA-binding protein (SSB) coats and protects the transiently exposed DNA on the lagging strand.

The E. coli replisome is able to duplicate the entire 4.6 Mb chromosome with high speed and accuracy (17,18). Due to the complex network of strong and weak interactions within the replisome, the nature of the interactions and how they permit the replisome to coordinate its various enzymatic activities are still not fully understood. The DnaB helicase, however, is generally acknowledged as the key for orchestrating the formation of the multi-enzyme replisomal complex at the replication fork. Consequently, the stability of the replicative helicase at the fork is likely an important parameter underlying successful replication initiation and processive fork progression. To date, DnaB stability during replication has only been substantiated to a limited extent through studies into DnaB binding kinetics, unwinding analysis and helicase structures in various states (reviewed in (19)).

In vivo single-molecule studies have characterised the average stoichiometry of DnaB at the fork (20–22). One of these studies estimates the lifetime of DnaB at the fork to be on the order of 15 min (22). In a similar scenario, several ensemble in vivo studies of replication fork stalling infer the stability of DnaB after stalling to be between 5 and 30 min (23–26). Due to the nature of these in vivo methods, technical limitations prevent accurate detection of DnaB stability. It is clear that DnaB remains at the fork longer than other replisome components, but the exact stability of the helicase during loading and replication is still uncertain.

Recently, single-molecule studies have revealed the ability of many replisome components to exchange with equivalent molecules in the surrounding environment (22,27–32). Specifically, the E. coli replicative polymerases were shown to rapidly exchange in a concentration-dependent manner (31). Similar behaviour was observed for the single-stranded DNA-binding protein (SSB) that is carried with the replisome (29). This emerging picture of plasticity in DNA replication portrays the replisome as a multi-faceted machine capable of sampling parallel reaction pathways to fulfil its goal (33,34). In light of these observations of the rapid dynamics of many replisome components, it could be inferred that the integrity of the replisome is linked to the stability of the DnaB helicase. It is tempting to speculate about an alternative scenario—that DnaB might also have the capability for dynamic exchange, and thus the entire replisome would be in a constant state of flux.

To assess the stability of the DnaB helicase in the context of replication, we use single-molecule assays to directly visualise individual helicases during DNA replication. In an in vitro reconstituted system, we use fluorescently labelled DnaB to allow us to monitor helicase behaviour in real time. We find that the active DnaB helicase remains stably associated even in the presence of a large excess of free DnaB molecules. Interestingly, additional helicases do transiently interact with the replisome. This transient interaction is enabled through the τ subunit of Pol III HE. In contrast to the dynamic behaviour of other replisome components, our results explicitly demonstrate that DnaB acts as a stable anchor within the replisome, thereby providing the interaction platform necessary to maintain replisome integrity throughout the processive replication of the bacterial chromosome.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Replication proteins

Escherichia coli DNA replication proteins were produced from E. coli expression strains using genes from E. coli K12 strains as described previously: the β2 sliding clamp (35); SSB (36); DnaG primase (37); Pol III αϵθ core (31); and the Pol III clamp loader complexes τ3δδ’ψχ, τ2γ1δδ’ψχ, τ1γ2δδ’ψχ (38), and γ3δδ’ψχ (12). DnaB6, DnaC and the DnaB6(DnaC)6 helicase–loader complex were produced through a new and more effective method. The overexpression and purification steps of this method are detailed in Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Figure S1. Concentrations of DnaB6, DnaC and the DnaB6(DnaC)6 complex were determined using the Quick Start Bradford Dye Reagent (Bio-Rad).

Production of DnaB6-H201C

The dnaB H201C mutation (Supplementary Figure S2) was made by a two-step overlap extension PCR, with internal mutagenic primers 578/H201C/F (5′-GCAGCCATGCGATGGCGTTACCGGGG) and 579/H201C/R (5′-GCCATCGCATGGCTGCTGAAACAACTG) and external primers 299 (5′-TGGGTGATCTTCAACTGG) and 300 (5′-TGTTCACGGGCAATACG). Plasmid DNA of pSB958 encoding wild-type DnaB (Supplementary Figure S1) was used as template; this plasmid contains a synthetic E. coli dnaCB operon in a pCE30 derivative (39), with a unique NdeI site at the start codon of dnaB. Primer 299 is located upstream of the dnaB gene and 300 is inside dnaB, beyond a unique NcoI site. The final PCR product was cleaned up using a QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen), digested with NdeI and NcoI, and the digested product used to replace the corresponding NdeI–NcoI fragment of pSB958. The nucleotide sequence of the inserted fragment in the resulting plasmid pZX1548 confirmed the presence of the H201C mutation and the absence of other mutations. Expression and purification of DnaB6-H201C was carried out in the same manner as the wild-type DnaB6 helicase (Supplementary Methods).

Labelling of DnaB6-H201C

The labelling methods described are based on a published procedure (40). DnaB6-H201C was labelled with Alexa Fluor 647 (Invitrogen) by solid-state labelling followed by multiple rounds of ammonium sulphate washing. First, 2 mg of DnaB6-H201C was reduced by adding 15 mM additional fresh dithiothreitol (DTT) to the existing buffer. The protein was then precipitated by gradual addition of solid ammonium sulphate (0.45 g ml–1), centrifuged (21 000 × g; 20 min) and the supernatant carefully removed. The protein was washed with 1 ml ice-cold labelling buffer (30 mM Tris–HCl pH 6.8, 100 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM EDTA, 10 mM MgCl2, 100 mM ADP) + 70% (w/v) ammonium sulphate that is now devoid of reducing agent and has been extensively degassed by sonication and deoxygenated with N2 gas. The protein was centrifuged again (21 000 × g; 20 min) and the pellet resuspended in 1 ml labelling buffer + 70% (w/v) ammonium sulphate + 0.95 mg AF647-maleimide dye (dissolved in 30 μl DMSO immediately before use; 20:1 molar ratio of dye to cysteine). The reaction was allowed to proceed by rotating gently overnight at 6°C in the dark. DnaB6-H201C–AF647 was separated from excess dye by centrifugation of the solution (21 000 × g; 20 min) and then washing the protein with 1 ml labelling buffer + 70% (w/v) ammonium sulphate + 4 mM DTT. The wash steps were repeated 15 times until no more dye remained in the supernatant. DnaB6–H201C–AF647 was dialysed into storage buffer (labelling buffer + 4 mM DTT, 20% v/v glycerol). The purity was confirmed by SDS-PAGE and the degree of labelling was determined by to be 3–4 dyes per DnaB hexamer by detection of single-molecule photobleaching steps (see Data analysis).

DnaB6–H201C was also labelled with Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen) by solid-state labelling followed by column chromatography and ammonium sulphate washing (procedure modified to improve protein yield). The labelling procedure was the same as above until the purification steps. After the reaction was complete, DnaB6–H201C–AF488 was separated from excess dye by centrifugation (21 000 × g; 20 min) and resuspended in 1 ml storage buffer. To remove the remaining dye, the labelled protein was applied at 1 ml min–1 to a column (1.5 × 10 cm) of Sephadex G-25 (GE Healthcare) equilibrated in storage buffer. Fractions containing DnaB6–H201C–AF488 were pooled, purity confirmed by SDS-PAGE (Supplementary Figure S3) and the degree of labelling determined to be 2–3 dyes per DnaB hexamer as above.

Ensemble replication assay of DnaB activity

Both Alexa Fluor 647- and Alexa Fluor 488-labelled DnaB6, now referred to as DnaB6(red) and DnaB6(blue) respectively, were tested for their activity in a bulk solution-phase leading-strand replication assay measuring the duplication of a flap-primed single-stranded M13 DNA template (31). First, the primed ssDNA template was made by annealing M13mp18 ssDNA (Guild BioSciences) with a 66-mer (IDT) oligonucleotide consisting of a 30-nt complementary segment. Each replication reaction contained 2.5 nM primed DNA template, 90 nM αϵθ core, 30 nM τ3δδ’ψχ clamp loader, 200 nM β2 clamp, 60 nM DnaB6(red) or DnaB6(blue) and 315 nM DnaC in bulk replication buffer (30 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.6, 12 mM magnesium acetate, 50 mM potassium glutamate, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.0025% v/v Tween20, 1 mM ATP, 10 mM DTT, 100 μM of each dNTP) in a final volume of 10 μl. All the reaction components were mixed (except for DNA) and cooled on ice before the reaction was initiated by adding DNA and moving to 30°C. After 10 min the reaction was stopped by addition of 10 μl heated quench buffer (200 mM EDTA, 2% w/v SDS, 1× DNA loading dye mix). The quenched mixtures were loaded into a 0.7% (w/v) agarose gel in TAE running buffer (160 mM Tris base pH 8.2, 80 mM acetic acid, 2 mM EDTA). DNA products were separated by electrophoresis for 100 min at 75 V, then stained with SYBR Gold and visualised by UV light on a Gel Doc XR (Bio-Rad).

Using this ensemble replication assay, DnaB6(red) and DnaB6(blue) were shown to support DNA replication as compared to WT DnaB6 and inactive DnaB6 (inactive DnaB6 comes from a bad preparation of this protein) (Supplementary Figure S3). Each labelled DnaB helicase proved capable of promoting DNA replication.

Single-molecule DnaB-loading assay

Microfluidic flow-cell devices were prepared as previously described (41,42). Briefly, a flow chamber was created by adhering a PDMS block with an indented channel to a functionalised biotin (Laysan Bio) coverslip. To reduce non-specific interactions with the surface during the experiment, the flow chamber was injected with degassed blocking buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.6, 100 mM NaCl, 2% w/v Tween20) and incubated for 30–60 min. The flow-cell device was mounted on an inverted TIRF microscope (Nikon Eclipse Ti-E), with an electrically heated stage (31°C; Okolab), a 100x TIRF objective (NA = 1.49, oil, Nikon), and connected syringe pump (Adelab Scientific).

The conditions used to measure DnaB loading were modified from previously described single-molecule replication experiments (29,31,38,42). Construction of a 2030-bp rolling-circle DNA template with controlled fork topology has been described previously (43). The loading solution contained 4 nM DnaB6(red), 21 nM DnaC and 20 pM rolling-circle DNA template (components preloaded in situ by incubating in 20 μl for 5 min at 37°C) in 150 μl degassed single-molecule loading buffer (30 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.6, 12 mM magnesium acetate, 50 mM potassium glutamate, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.0025% w/v Tween20, 0.5 mg ml–1 BSA, 1 mM ATP, 10 mM DTT, 150 nM SYTOX Orange (Invitrogen)). The loading solution was injected into the blocked flow chamber at 100 μl min−1 for 1 min and then at 5 μl min−1 for 10 min.

To detect DnaB loaded onto DNA, the SYTOX Orange-stained rolling-circle DNA template was visualised in real time with either a 514-nm (Coherent, Sapphire 514-150 CW) or 568-nm laser (Coherent, Sapphire 568-200 CW) at 400 mW cm−2 for 1 s once every 30 s. The DnaB6(red) protein was visualised by constant excitation with a 647-nm laser (Coherent, Obis 647-100 CW) at 80 mW cm−2. The fluorescence signals were captured with an EMCCD camera (Evolve delta, Photometrix) with appropriate filter sets (Chroma). DnaB loading was identified by colocalisation of DNA foci with DnaB6(red) foci to within 2 pixels (see Data analysis). In the loaded-DnaB stability experiments, the injection of the loading solution was followed by injection of single-molecule loading buffer at 100 μl min−1 for 1 min and then at 10 μl min–1 for 35 min. DNA was excited in a similar manner as the loading experiment; however, DnaB6(red) was excited in intervals of 400 ms once every 8 s to significantly extend the lifetime of the fluorophores to approximately 60 min (Supplementary Figure S4).

Single-molecule rolling-circle replication assay

Preloaded conditions

This replication assay used the same microfluidic flow-cell devices described above as well as the same DnaB-loading step, followed by a replication step that was adapted from existing methods (29,31,38,42). In preloaded DnaB experiments, the replication solution contained 10 nM Pol III αϵθ core, 3.3 nM τ3δδ’ψχ clamp loader (i.e. Pol III* assembled in situ from clamp loader and cores in 4 μl for 90 s at 37°C), 30 nM β2 clamp, 75 nM DnaG and 20 nM SSB4 in single-molecule replication buffer (single-molecule loading buffer + 250 μM of each dNTP, 250 μM of each NTP, 1 mM UV-aged Trolox, 0.8% w/v glucose, 0.12 mg ml–1 glucose oxidase and 12 μg ml–1 catalase). Replication was initiated by injecting the replication solution into a flow chamber containing immobilised rolling-circle DNA templates at 100 μl min−1 for 1 min and then at 10 μl min−1 for 10 min. DNA and DnaB6(red) were visualised using the same conditions as the Single-molecule loading assay for a period of 10 min.

In-solution conditions

For the in-solution DnaB6(red) experiments, 2 nM DnaB6(red) was added to the replication solution. DnaC is not present here.

Chase conditions

For the WT DnaB6 chase experiments, 30 nM WT DnaB6 was added to the replication solution. The preloaded DnaB6(red) fluorescence lifetime was extended by exciting intermittently for 400 ms once every 800 ms. For the DnaB6(blue) chase experiments, 2 nM DnaB6(blue) was added to the replication solution. DnaB6(blue) was visualised by excitation with a 488-nm laser (Coherent, Sapphire 488-200 CW) at 4500 mW cm−2.

Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) conditions

For the DnaB6(red) FRAP experiments, 2 nM DnaB6(red) was added to the replication solution and after 2 min of imaging replication, a 647-nm FRAP pulse at 240 W cm–2 for 5 s was used to bleach all of the DnaB6(red) foci in the field of view. Recovery of any foci was recorded over the following 4 min.

Stationary replisome association assay

The single-molecule replisome association assay was designed to detect the frequency with which free DnaB molecules interact with the replisome. This assay was identical to the DnaB6(blue) chase experiments, except for the replication/association step. In these experiments, dATP and dTTP were omitted. The remaining dCTP and dGTP are the next three nucleotides to be incorporated at the primer–template junction and thus keep the Pol III core bound in either the polymerization or proofreading mode and not synthesizing new DNA (Supplementary Figure S5). This technique has previously been applied to pre-assemble the whole replisome prior to replication (31,44,45), and to direct Pol III core towards the polymerisation or proofreading mode (46).

Therefore, in the whole replisome experiments, DnaB association was observed after injecting the association solution (replication solution without dATP or dTTP + 2 nM DnaB6(blue)) into a flow chamber containing immobilised rolling-circle DNA templates at 100 μl min−1 for 1 min and then at 10 μl min−1 for 10 min. As with the DnaB6(blue) chase experiments, this experiment was imaged by switching between DnaB6(red) and DnaB6(blue), and SYTOX Orange stained DNA was imaged once every 30 s for a total of 10 min. When indicated, replisome components were omitted to test their effect on the DnaB binding frequency.

Data analysis

All analyses were carried out using ImageJ/Fiji (1.51e) and MATLAB 2016b, and in-house built plugins. Many of these processes are detailed elsewhere (41).

Quantification of degree of labelling

The numbers of fluorophores per labelled DnaB6(red) and DnaB6(blue) were quantified by immobilisation of DnaB6 from a 20 pM solution in replication buffer on the surface of a cleaned microscope coverslip. Imaging was done by exciting constantly at 2400 mW cm–2 for 5 min to allow photobleaching of the fluorophores. Raw movies were corrected for the electronic offset and excitation-beam profile. Single molecules of labelled DnaB6 were identified using our peak fitter tool and the photobleaching steps were fit using change-point analysis (Supplementary Figure S6A and D) (47–49). The histogram of steps per molecule was fit to a Poisson distribution (Supplementary Figure S6C and F). The degree of labelling was found to be 3–4 dyes (Poisson mean parameter, λ = 3.50; number of observations, n = 260) and 2–3 dyes (λ = 2.52; n = 181) per hexamer of DnaB6(red) and DnaB6(blue), respectively.

Determination of stoichiometry

The number of labelled DnaB6 molecules (during the loading step or at actively replicating replisomes) was calculated by dividing their initial intensities by the intensity of a single fluorophore and correcting for the pre-determined degree of labelling. The average intensity per fluorophore was quantified by detecting photobleaching steps in labelled DnaB6 non-specifically bound to the surface (Supplementary Figure S6B and E). The integrated intensity for every fluorescent DnaB in a field of view was calculated after applying a local background subtraction. The histograms obtained were fit with a Gaussian distribution function to give the average intensity.

Colocalisation analysis

Foci of two separate colours were classed as being colocalised if their centroid positions (determined using our peak fitter tool) fell within 2 pixels of each other. The chance of coincidental colocalisation (C) was calculated using Equation 1, where AR is the focus area, AFOV is the field of view area, and n is the number of foci.

|

(1) |

FRAP recovery analysis

To obtain the characteristic exchange time τ from the FRAP experiments, the intensity of DnaB was tracked as a function of time. The data were fit with a FRAP recovery function correcting for photobleaching (22,29,31,50) (Equation 2, where a is the amplitude of photobleaching, τb is the photobleaching time, and I0 is the number of DnaB at the fork at steady state).

|

(2) |

DnaB association frequency analysis

The characteristic timescales of the DnaB dynamics were extracted by tracking the fluorescence intensity of DnaB6(blue) over time. A threshold was determined for each intensity trajectory equivalent to the intensity of half a DnaB6(blue) molecule. The binding frequency was defined as the number of times per minute where the intensity exceeded the threshold.

RESULTS

Single-molecule visualisation of DnaB helicase dynamics

Previous studies have established single-molecule fluorescence methods to monitor reconstituted replisomes during in vitro DNA replication (28,29,31,32,44,45,51–54). Several of these studies also explore how functional E. coli replisomes can be sequentially assembled in vitro by introducing the appropriate proteins over time to immobilised DNA templates (29,31,50). We adapted these replisome assembly conditions to separate helicase loading and DNA replication into discrete steps and thus to examine DnaB activity in each.

To visualise single molecules of DNA-loaded DnaB, we used a mutant of DnaB6 (H201C) site-specifically labelled with a cysteine-reactive red fluorescent dye (Alexa Fluor 647). Note that wild-type DnaB contains no native cysteine residues, and His201 is positioned in a solvent-exposed loop near the C-terminal face of the helicase, remote from the sites of its interaction with DnaG (PDB ID: 2R6A) (55), the DnaC helicase loader and ssDNA (PDB ID: 6QEM) (4) (Supplementary Figure S2). Consistent with this location, neither the mutation nor subsequent labelling significantly affected the function of DnaB during leading-strand replication (Supplementary Figure S3). Nevertheless, we have not been able to exclude that interactions with other proteins (e.g. DnaA or Rep) that are not used in this work may be affected. It is also possible that the helicase activity of the mutant may be modestly affected by modulation of interactions with its excluded (leading) strand, as has been observed for a series of conserved basic residues on its surface (56); note that these residues are also structurally remote from H201, and interactions of DnaB with the excluded strand have not yet been characterised structurally.

A 5′-biotinylated rolling-circle DNA template (2030 bp) with replication fork topology (43) was used for DnaB loading and subsequent replisome assembly (Supplementary Figure S5A). DnaB6(red) mixed with DnaC in the presence of ATP was added to the DNA template and then injected into a microfluidic flow-cell to immobilise the complex on a streptavidin-functionalised surface (Figure 2A). The DNA template stained with SYTOX Orange (green) and DnaB6(red) were both visualised by near-total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) imaging and loaded DnaB helicases identified by the colocalization of the corresponding foci (Figure 2B). Of the DNA template foci detected in one field of view, 32% (n = 128) colocalise with DnaB6(red) foci and thus represent successfully loaded DnaBC helicase–helicase loader complexes. This value is well above the degree of colocalisation expected by chance (5%; see Methods).

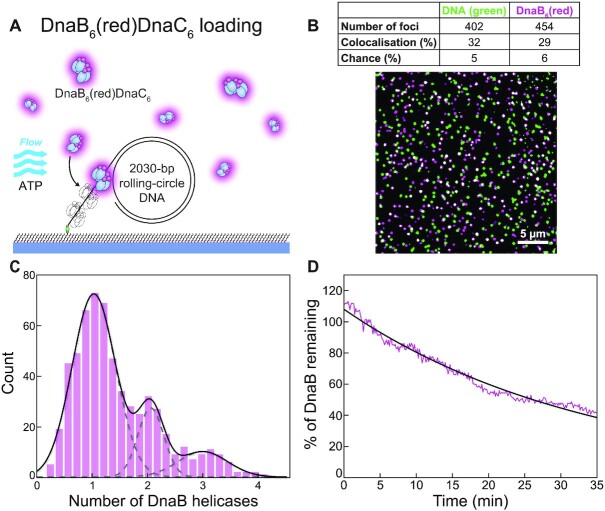

Figure 2.

Visualisation of loaded DnaB helicases at the single-molecule level. (A) Illustration of the singlemolecule helicase-loading assay. DnaB6(red)DnaC6, a 2030 bp rolling-circle DNA template and the nucleotides required for loading are mixed and applied to a microfluidic flow channel. The 5′-biotinylated DNA couples to the streptavidin-functionalised surface and immobilises the complex. (B) Loaded DnaB helicases appear as colocalised foci (white) of DnaB6(red) and SYTOX Orange-stained DNA (green). The table indicates the number of foci, the degree of colocalisation and the degree of coincidental colocalisation by chance. (C) Distribution of DnaB6(red) stoichiometry loaded onto the 59-nt single-stranded DNA tail (n = 606). The black line represents the sum of three Gaussian distribution functions fit to the data. The dashed grey lines represent the individual Gaussian distributions. (D) The average binding lifetime of loaded DnaB6(red) molecules (magenta; n = 123). A single-exponential fit to the data (black) gives a binding lifetime of 34.4 ± 0.4 min. Photobleaching time is measured to be ∼60 min (Supplementary Figure S4) and therefore does not significantly impact on the observed kinetics.

To calculate the number of DnaB helicases loaded on DNA templates, we quantified the intensities of colocalised DnaB6(red) foci and divided them by the calibrated average intensity for a single DnaB molecule (Supplementary Figure S6B). The resulting distribution shows three distinct populations corresponding to 1.0 ± 0.1, 2.0 ± 0.1 and 2.9 ± 0.1 loaded helicases (mean ± S.E.M., n = 606) with decreasing occurrence, respectively (Figure 2C). The 59-nt single-stranded tail of the DNA template (Supplementary Figure S5A) could plausibly accommodate up to two DnaBC complexes with an estimated footprint of ∼30 nt (4) or three DnaB after DnaC dissociation with a footprint of 18–20 nt per helicase hexamer (57). It is also possible that one molecule of DnaB could occupy the 25-nt gap on the leading strand. The shape of the distribution (Figure 2C) implies that the probability of loading another helicase decreases as available ssDNA space decreases.

We assessed the stability of DnaB helicases loaded at the fork by flowing out excess DnaB6(red) (and DnaC) and measuring the binding lifetime of loaded DnaB6(red) (Figure 2D). The average intensity over time of n = 123 DnaB6(red) molecules was fit to a single exponential decay, yielding a mean lifetime of 34.4 ± 0.4 min (mean ± S.E.M.). The photobleaching of DnaB6(red) was greatly extended by imaging intermittently for 400 ms once every 8 s. To determine the photobleaching lifetime under these conditions, we extrapolated several known values for other conditions to determine a value of ∼60 min (Supplementary Figure S4). It is unlikely that this degree of photobleaching interferes with the measurement of the DnaB binding lifetime. Even taking the impact of photobleaching into account, our data suggest that once loaded, DnaB remains stably bound at a fork for ∼30 min.

After our observation of the number of helicases loaded at the fork, we set out to determine the number associated with progressing replisomes. Similar to the helicase loading experiments, we pre-loaded DnaB6(red) on the rolling-circle DNA template and immobilised the complex on the surface. Then, we flow out excess DnaB6(red) (and DnaC) and flow in replication solution (Pol III*, β2 clamp, DnaG primase, SSB, dNTPs, NTPs) to initiate the replication reaction (Figure 3A). Rolling-circle replication products could be observed within tens of seconds as they were stretched out by hydrodynamic force, where the start of the kymograph indicates the point of buffer injection (Figure 3B, Supplementary Figure S7A). Intermittent imaging of SYTOX Orange stained DNA (green) and DnaB6(red) identified DnaB helicases present only at the replication fork of DNA products (Figure 3B). Stoichiometric quantification of these DnaB6(red) foci produced a distribution centred about 0.9 ± 0.1 helicases (mean ± S.E.M., n = 32) (Figure 3C). Therefore, these results confirmed that of the multiple DnaB helicases stably loaded onto ssDNA, only one is converted into an active replisome.

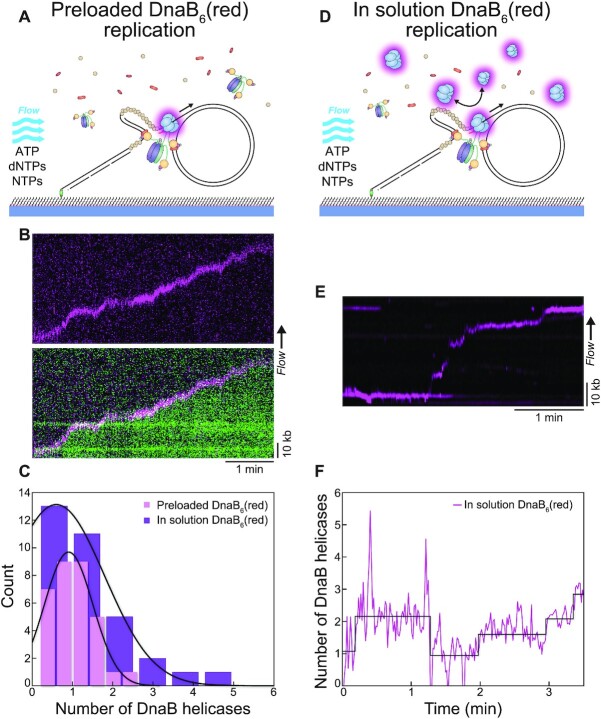

Figure 3.

More than one DnaB helicase are frequently present at the replication fork. (A) Illustration of the rolling-circle replication assay with DnaB6(red) preloaded on the DNA prior to introducing the replication solution. Replication is monitored in real time by flow stretching the replicating DNA products by hydrodynamic force. (B) (Top) Representative kymograph of preloaded DnaB6(red) moving with the fork during rolling-circle replication. (Bottom) Overlay of the DnaB6(red) and SYTOX Orange-stained DNA (green) kymographs shows the helicase molecule moving with the replication fork at the tip of the DNA product. (C) Distributions of DnaB helicase stoichiometry at the fork in the absence of DnaB6(red) in solution (magenta; n = 32) and in the presence of DnaB6(red) in solution (purple; n = 33). The black lines represent Gaussian fits to the data. (D) Illustration of the in-solution assay, where DnaB6(red) is preloaded and also included at 2 nM in the replication solution. (E) Representative kymograph showing the DnaB6(red) signal at the fork when DnaB6(red) is present in solution. (F) Number of DnaB6(red) as a function of time for the kymograph in (E) showing the fluctuation in DnaB helicase stoichiometry during the course of replication, where steps are detected by change-point analysis (47–49).

When we repeat this rolling-circle replication experiment, but now with 2 nM DnaB6(red) present in the replication solution, we observe a different outcome (Figure 3D). DnaB6(red) foci were found at the fork (Figure 3E) but also occasionally left behind the progressing replisome (Supplementary Figure S7B). We considered the possibility that DnaB6(red) might be binding to incomplete Okazaki fragments with ssDNA gaps under these conditions where excess Pol III holoenzyme and SSB, but not DnaC, are present in solution. Although DnaB is known to associate with naked ssDNA (57,58), its loading onto SSB-coated ssDNA generally requires specialized DNA structures such as forks, DnaC and other (replication restart) proteins (58–60). Although ssDNA gaps on the lagging strand can be observed when experiments are set up specifically to detect them (61,62) and may be produced under our conditions due to premature release of the lagging strand polymerase, we have shown that these gaps are subsequently filled by the additional free Pol III holoenzyme from solution (29). We conclude therefore that the labelled DnaB is most likely bound via the τ subunit (50) to the Pol III holoenzyme left behind at Okazaki fragment junctions under these conditions where Okazaki fragment processing enzymes (DNA Pol I and ligase) are absent (29).

Analysis of the stoichiometry of DnaB6(red) localised at the fork results in a distribution centred at 0.6 ± 0.3 helicases (mean ± S.E.M., n = 33). Examining individual intensity traces of DnaB6(red) shows that intermittently, there is an increase in fluorescence equivalent to another helicase molecule localised to the replisome (Figure 3F). The physical divergence of these two helicase signals (Figure 3E) suggests one supports rolling circle replication, while the other does not. The presence of more than one helicase raises two questions: Is the replisomal DnaB helicase exchanging with other helicases in the surrounding solution? Or conversely, are extra helicases contributing to the replisome via a secondary mechanism?

DnaB helicase is a stable anchor within the replisome

There is no evidence in the literature to suggest that DnaB stochastically exchanges during DNA replication in the same manner shown for Pol III* and SSB (22,29,31). We detect, however, recurrent dynamics in the DnaB6(red) signal, indicating there is often more than one helicase at the replication fork (Figure 3E and F), and thus the potential for helicase exchange. Similar to other single-molecule studies of exchange, we applied fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) to our replication assay with DnaB6(red) present in solution. Recovery events were detected (Supplementary Figure S8A and B) which indicates DnaB6(red) molecules from solution associate with the fork during replication. Summing multiple single-molecule recovery curves suggests a recovery on the timescale of several minutes (Supplementary Figure S8C). While suggestive of dynamic exchange, the apparent on/off events in the fluorescence signal creates noise in the FRAP recovery curves, making the process challenging to study.

To further test the helicase exchange hypothesis, we developed a chase exchange assay as an alternative approach to address exchange during DNA replication. First, we initiated rolling-circle replication with pre-loaded DnaB6(red) and then chased with a physiological concentration (30 nM) of dark, WT DnaB6 in the replication solution (Figure 4A). We hypothesised that if fluorescent DnaB exchanges with unlabelled DnaB from solution, we should see a disappearance of fluorescence at the fork. However, we found replisomal DnaB6(red) molecules to be unaffected by the excess unlabelled, WT DnaB6 during replication (Figure 4B, Supplementary Figure S7C). Analysing the fluorescence of these replicating DnaB6(red) foci identified that the average lifetime of 4.6 ± 0.1 min (mean ± S.E.M., n = 29) is very close to that of the photobleaching lifetime of 4.8 ± 0.1 min (mean ± S.E.M., n = 667) (Figure 4C). The inability of the WT DnaB6 to perturb replisomal DnaB6(red) is compelling evidence that the helicase does not undergo exchange during DNA replication. Instead, these results suggest a single DnaB helicase persists for the entirety of the replication cycle, acting as a stable anchor for the other replisome components.

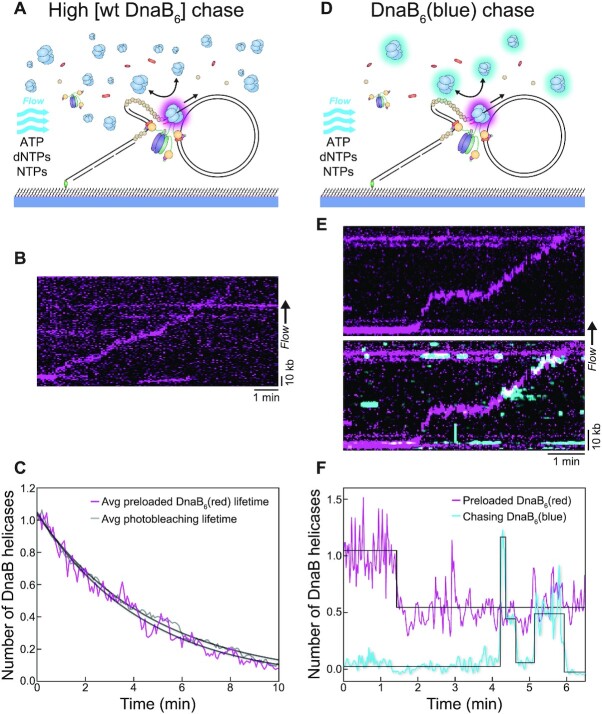

Figure 4.

DnaB helicases are both stable and dynamic during replication. (A) Illustration of the WT DnaB chase assay, where preloaded DnaB6(red) was ‘chased’ with a relatively high concentration of WT DnaB (30 nM) in the replication solution. Like the standard rolling-circle assay, DNA products are stretched out by hydrodynamic force. (B) Representative kymograph of DnaB6(red) moving with the fork during rolling-circle replication in the WT DnaB chase assay. (C) The average intensity over time from replicating DnaB6(red) molecules in the WT DnaB chase assay (magenta; n = 29), compared to the photobleaching lifetime of DnaB6(red) (grey; n = 667). The curve from each condition is fit with a single-exponential decay to provide the characteristic lifetime. (D) Illustration of the DnaB6(blue) chase assay, where preloaded DnaB6(red) is ‘chased’ with DnaB6(blue) (2 nM) in the replication solution. Again, the DNA products are stretched out by hydrodynamic force. (E) (Top) Representative kymographs of DnaB6(red) moving with the fork during rolling-circle replication in the DnaB6(blue) chase assay. (Bottom) The DnaB6(blue) kymograph from the same replication event shows the frequent association of additional helicases with the replication fork. (F) The stoichiometry over time from both the DnaB6(red) and DnaB6(blue) signal corresponding to the kymograph in (E), where steps are detected by change-point analysis (47–49).

To further investigate the extra DnaB6(red) foci identified at the replication fork, we applied a similar technique to the dark WT DnaB6 chase experiment. In this experiment, DnaB6(red) was pre-loaded onto the rolling-circle DNA template, but then chased with DnaB6(blue) in the replication solution (Figure 4D). Imaging both colours of labelled DnaB during replication showed DnaB6(red) foci at the replication fork in parallel to our previous observations, but also DnaB6(blue) molecules binding intermittently at the fork (Figure 4E, Supplementary Figure S7D). The appearance of DnaB6(blue) fluorescence did not correlate with the disappearance of DnaB6(red) signal (Figure 4F), which further solidifies the absence of helicase exchange. The dynamic association of DnaB6(blue) with the replication fork suggests extra DnaB helicases can somehow transiently interact with the replisome.

Additional helicases dynamically interact with the replisome through the τ subunit of the CLC

Our observation of the presence of extra helicases at the replication fork has not been reported before. Our chase replication experiments establish that any additional helicases do not interfere with the unwinding function of the main replisomal DnaB helicase. To understand the nature of the interaction of the extra DnaB helicases, we restructured our replication assay into a stationary replisome association assay. In this assay we utilise our available fluorescent tools to assess association of fluorescent DnaB with a stationary replisome to achieve much higher throughput of data. This stationary replisome association assay builds on observations of single-molecule DNA replication as carried out by replisomes completely pre-assembled prior to replication (31,44,45). First, the loaded DnaB6(red)DnaC6–DNA complex (identical to the DnaB-loading experiments in Figure 2A) is immobilised on the surface of a flow-cell. Then, an association solution consisting of the remaining replisome components, DnaB6(blue), ATP, dCTP and dGTP is injected (Figure 5A). Including only two of the four nucleotides allows for proper binding of the polymerases within the replisome but prevents them from replicating the whole template (Supplementary Figure S5B). When the polymerase core is blocked from synthesis, it is expected to enter a stalled state which still retains a strong affinity for DNA (46), and thus the entire replisome can be assembled but remains stationary. Herein lies the effectiveness of this assay, as we can identify assembled replisomes and then automate the acquisition and analysis of DnaB6(blue)-replisome interactions.

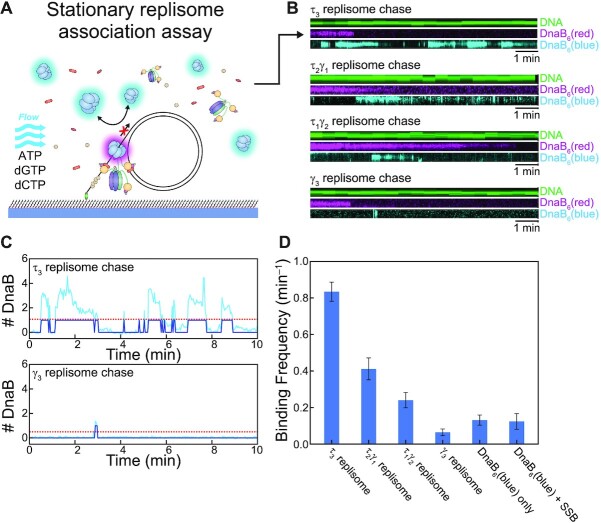

Figure 5.

Additional helicases are able to interact with the replisome through the τ subunit of the clamploader complex. (A) Illustration of the stationary replisome-association assay. The replisome (including DnaB6(blue)) is assembled during the ‘association’ phase after preloading DnaB6(red) onto DNA. Including only dGTP and dCTP in this reaction permits the replisome to assemble but precludes net DNA synthesis. (B) Example kymographs from different experiments where the CLC has a varying composition of τ subunits. Comparing the DnaB6(blue) kymographs shows how changing the reaction composition affects the frequency at which free DnaB6(blue) binds to assembled replisomes. More example kymographs can be found in the Supplementary Figure S9. (C) The detection of DnaB6(blue) binding from the example kymographs from the τ3 replisome chase and γ3 replisome chase experiments in (B). A binding event is recorded (dark blue) when the intensity of the DnaB6(blue) signal (light blue) passes the threshold level (red). (D) Comparison of the binding frequency of DnaB6(blue) from different experiments: τ3 replisome, n = 123; τ1γ2 replisome, n = 70; γ3 replisome, n = 43; DnaB6(blue) only, n = 74; DnaB6(blue) and SSB only, n = 36. Tabulation of these values can be found in Supplementary Figure S11.

We identified stationary, assembled replisomes based on the colocalisation of DnaB6(red) and SYTOX Orange-stained DNA in the same manner as the DnaB loading experiments (Supplementary Figure S9A). When the immobilised DnaB6(red)DnaC6-DNA complexes are exposed to the association solution with all the replisome components, we see dynamic binding of DnaB6(blue) molecules (Figure 5B). These dynamics are consistent with the association events detected at the replication fork during the DnaB6(blue) chase assay (Figure 4E). When we analyse all the intensities observed throughout the experiment, we see that, on average, DnaB6(blue) is bound 43% of the time (Supplementary Figure S10A). In contrast, when we omit all other replisome components from the association solution, we only see DnaB6(blue) bound 12% of the time (Supplementary Figure S10B). To extract the characteristic frequency of the binding dynamics, we applied thresholding analysis to the DnaB6(blue) signal to automate the detection of binding events (Figure 5C). We found that the binding frequency of DnaB6(blue) varied both within and between experiments depending on several factors. For the condition where all replisome components are present (Figure 5D), we determined a binding frequency of 0.84 ± 0.05 min–1 (mean ± S.E.M., n = 123). We are able to compare this measurement to other DnaB6(blue) binding populations within the same experiment. When we measure the DnaB6(blue) dynamics on DNA templates that lack a loaded DnaB6(red), the frequency was slightly lower (0.69 ± 0.01 min–1, n = 1651; Supplementary Figure S11). The dynamics on DnaB6(red) foci not bound to DNA are less frequent (0.35 ± 0.02 min–1, n = 421; Supplementary Figure S11). Together these observations show that the additional DnaB interactions occur more frequently at replisomes containing all components. Furthermore, when we modify the experimental condition to include only DnaB6(blue) in the association solution, we observe significantly less DnaB6(blue) binding at colocalised DnaB6(red)–DNA sites (0.13 ± 0.02 min–1, n = 74) (Figure 5D). The lack of dynamics in the absence of other replisomal components indicates that the additional DnaB binds to the replisome through an interaction with another replisomal protein.

To identify this factor, we repeated the experiment with the omission of specific proteins and found that when the CLC lacks the τ subunit (γ3δδ’ψχ), significantly less frequent DnaB6(blue) binding is detected. Under these conditions, the binding frequency of DnaB6(blue) at DnaB6(red)–DNA sites, 0.07 ± 0.02 min–1 (n = 43) is not significantly different from that observed with DnaB6(blue) only (above) or with only SSB and DnaB6(blue) (0.12 ± 0.04 min–1, n = 36) (Figure 5D). Part of the DnaB6(blue) binding dynamics can be recovered proportionally by the presence of a CLC that includes either one (τ1γ2δδ’ψχ; 0.24 ± 0.04 min–1, n = 70) or two τ subunits (τ2γ1δδ’ψχ; 0.41 ± 0.06 min–1, n = 26) (Figure 5D). Taken together, these results implicate the τ subunit of Pol III holoenzyme as the factor responsible for recruiting extra DnaB helicases to the replisome. DnaB has a known affinity for τ (16,50), yet it was always believed that this interaction was reserved for maintaining the physical connection between the Pol III HE and the replisomal helicase.

DISCUSSION

We report here the use of single-molecule fluorescence imaging to visualise single molecules of the DnaB helicase and study its dynamics. We used a collection of functional assays to examine the stability of the helicase during the discrete stages of helicase loading and DNA replication.

Firstly, our quantification of labelled DnaB stoichiometry showed that during loading, multiple DnaB molecules can be deposited onto the exposed single-stranded region of our DNA template. In contrast, quantitative studies of replication initiation identified that each strand of the E. coli origin of replication, oriC is bound by a single DnaBC complex (63,64). Our loading method, although effective for our assay, does not reproduce the physiological conditions of initiation at oriC. We used a pre-made fork template with an exposed 5′ end in contrast to the topologically closed DNA bubble that occurs at oriC. We also do not include the DnaA initiator protein, which normally recruits DnaB to the origin through interactions with both DnaB and DnaC (64–69). Our results demonstrate that multiple helicases will associate with ssDNA if there is space available. Therefore, we know DnaBC is capable of engaging ssDNA by itself, but special mechanisms are in play at oriC involving DnaA to load two and only two helicases onto opposite strands.

We find that, once loaded, DnaB remains stably associated with the forked ssDNA for ∼30 min. This lifetime of DnaB during loading is comparable to other observations of DnaB being bound to ssDNA for times between 5 and 30 min (22–26). Our results are further evidence that once DnaB associates with DNA, it forms a highly stable nucleoprotein complex. The DnaB helicase is also expected to be stably integrated as part of the active replisome. Other studies have inferred the stability of replisomal DnaB based on in vivo lifetime measurements (22), and the stability of the whole replisome during normal DNA replication (70) or once challenged (23–26). It is nevertheless possible that hidden amongst these indirect measurements of stability, DnaB has the capacity to exchange during replication. There are an increasing number of studies demonstrating that, at cellular protein concentrations, the bacterial replisome does not have a static composition, but rather exchanges its components frequently (22,27–32,71). Therefore, we designed three single-molecule replication assays to directly detect DnaB exchange. Each of these showed the absence of exchange on the minutes timescale—instead the replisomal helicase was maintained for the entirety of replication. This result implicates DnaB as the stability factor of the replisome on which other components can dynamically interchange, and agrees with the regulatory mechanism suggested by Monachino et al. (50). Our direct observations of DnaB stability indicates its function as the processivity factor of the replisome. The replisomal helicase not only forms the stable anchor on which exchange occurs, but also acts as the central platform for the coordination of the main events of replication.

Despite the lack of DnaB exchange in the replisome, we do detect recurrent dynamics in the DnaB signals. These dynamics signify the frequent and transient association of extra helicases with the replication fork. From our chase experiments, we demonstrate that these extra helicases are indeed not stably incorporated, and do not interfere with the replisomal DnaB. Two other single-molecule studies of replisome stoichiometries in live cells find populations centred about one or two helicases (20,21). Both studies explain the two-helicase population as the result of two replisomes bidirectionally replicating the chromosome contained within a single diffraction-limited spot. The width of the stoichiometry distributions in both studies, however, could hide populations in which up to three or four hexamers are bound momentarily within these diffraction-limited spots. These observations are consistent with our finding of extra DnaB transiently interacting with the replisome.

It is unclear if additional helicases play a functional role in the replisome. Our observation of successful replication with and without extra helicases suggests that these DnaB molecules do not contribute to unwinding of dsDNA. Furthermore, as we have demonstrated the high degree of stability of the helicase, the benefit of having additional DnaB in the replisome is not readily apparent. One possible implication relates to cellular DNA lesions (60), where re-loading of DnaB after lesion-induced stalling could be helped by readily available extra helicases. Through quantification of the frequency of DnaB associating with stationary replisomes, we determined that additional helicases interact with the replisome through the τ subunit(s) of the clamp-loader complex. With increasing number of τ subunits in the CLC, we see a proportionate increase in the binding frequencies of additional helicases. This dependency shows that the local concentration of τ subunits dictates the access of free helicases from solution. The mode of this interaction is likely the same as the previously identified weak interaction of domain IV of τ and DnaB (50). It remains difficult to pinpoint the exact number of replisomal helicase connections and if such factors are static or dynamic throughout the Okazaki fragment cycling of the replisome.

In conclusion, we applied single-molecule imaging tools to an in vitro-reconstituted E. coli replication reaction to demonstrate a high stability of integration of the replicative DnaB helicase at replication forks. We argue that DnaB is the stable anchor within the replisome that plays a critical role in replisome processivity and thus integrity. Having established a fluorescence-based assay for visualisation of DnaB at the single-molecule level, future experimentation should focus on the dynamics of replication initiation as well as alternative pathways sampling by DnaB and the CLC during the cycling of Okazaki fragments. Such studies would help us understand how the DnaB helicase, and by extension the whole replisome, coordinates with other proteins to respond to challenges to replication integrity.

DATA AVAILABILITY

Home-built ImageJ plugins have been deposited on the Github repository for Single-molecule/Image analysis tools (https://github.com/SingleMolecule).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the greater van Oijen/Dixon lab group for discussion of the project with special thanks to Dr Flynn Hill, Dr Enrico Monachino and Dr Jacob Lewis.

Contributor Information

Richard R Spinks, Molecular Horizons and School of Chemistry and Molecular Bioscience, University of Wollongong, Wollongong, New South Wales 2522, Australia; Illawarra Health & Medical Research Institute, Wollongong, New South Wales 2522, Australia.

Lisanne M Spenkelink, Molecular Horizons and School of Chemistry and Molecular Bioscience, University of Wollongong, Wollongong, New South Wales 2522, Australia; Illawarra Health & Medical Research Institute, Wollongong, New South Wales 2522, Australia.

Sarah A Stratmann, Zernike Institute for Advanced Materials, University of Groningen, Groningen 9747 AG, The Netherlands.

Zhi-Qiang Xu, Molecular Horizons and School of Chemistry and Molecular Bioscience, University of Wollongong, Wollongong, New South Wales 2522, Australia; Illawarra Health & Medical Research Institute, Wollongong, New South Wales 2522, Australia.

N Patrick J Stamford, Research School of Chemistry, Australian National University, Canberra, Australian Capital Territory 2601, Australia.

Susan E Brown, Research School of Chemistry, Australian National University, Canberra, Australian Capital Territory 2601, Australia.

Nicholas E Dixon, Molecular Horizons and School of Chemistry and Molecular Bioscience, University of Wollongong, Wollongong, New South Wales 2522, Australia; Illawarra Health & Medical Research Institute, Wollongong, New South Wales 2522, Australia; Research School of Chemistry, Australian National University, Canberra, Australian Capital Territory 2601, Australia.

Slobodan Jergic, Molecular Horizons and School of Chemistry and Molecular Bioscience, University of Wollongong, Wollongong, New South Wales 2522, Australia; Illawarra Health & Medical Research Institute, Wollongong, New South Wales 2522, Australia.

Antoine M van Oijen, Molecular Horizons and School of Chemistry and Molecular Bioscience, University of Wollongong, Wollongong, New South Wales 2522, Australia; Illawarra Health & Medical Research Institute, Wollongong, New South Wales 2522, Australia.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

Australian Research Council [DP150100956, DP180100858 to A.M.v.O., N.E.D.]; Australian Laureate Fellowship [FL140100027 to A.M.v.O.]; King Abdullah University of Science and Technology, Saudi Arabia [OSR-2015-CRG4-2644 to N.E.D., A.M.v.O.]; Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship (to R.R.S). Funding for open access charge: Australian Research Council.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Lewis J.S., Jergic S., Dixon N.E.. The E. coli DNA replication fork. Enzymes. 2016; 39:31–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Leipe D.D., Aravind L., Grishin N.V., Koonin E.V.. The bacterial replicative helicase DnaB evolved from a RecA duplication. Genome Res. 2000; 10:5–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chodavarapu S., Kaguni J.M.. Replication initiation in bacteria. Enzymes. 2016; 39:1–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chodavarapu S., Jones A.D., Feig M., Kaguni J.M.. DnaC traps DnaB as an open ring and remodels the domain that binds primase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016; 44:210–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Felczak M.M., Chodavarapu S., Kaguni J.M.. DnaC, the indispensable companion of DnaB helicase, controls the accessibility of DnaB helicase by primase. J. Biol. Chem. 2017; 292:20871–20882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Arias-Palomo E., Puri N., O'Shea Murray V.L., Yan Q., Berger J.M.. Physical basis for the loading of a bacterial replicative helicase onto DNA. Mol. Cell. 2019; 74:173–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Makowska-Grzyska M., Kaguni J.M.. Primase directs the release of DnaC from DnaB. Mol. Cell. 2010; 37:90–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lu Y.B., Ratnakar P.V., Mohanty B.K., Bastia D.. Direct physical interaction between DnaG primase and DnaB helicase of Escherichia coli is necessary for optimal synthesis of primer RNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1996; 93:12902–12907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Corn J.E., Pease P.J., Hura G.L., Berger J.M.. Crosstalk between primase subunits can act to regulate primer synthesis in trans. Mol. Cell. 2005; 20:391–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kelman Z., O’Donnell M.. DNA polymerase III holoenzyme: structure and function of a chromosomal replicating machine. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1995; 64:171–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Leu F.P., Hingorani M.M., Turner J., O’Donnell M.. The δ subunit of DNA polymerase III holoenzyme serves as a sliding clamp unloader in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 2000; 275:34609–34618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dohrmann P.R., McHenry C.S.. A bipartite polymerase–processivity factor interaction: only the internal β binding site of the α subunit is required for processive replication by the DNA polymerase III holoenzyme. J. Mol. Biol. 2005; 350:228–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jergic S., Horan N.P., Elshenawy M.M., Mason C.E., Urathamakul T., Ozawa K., Robinson A., Goudsmits J.M.H., Wang Y., Pan X.et al.. A direct proofreader-clamp interaction stabilizes the Pol III replicase in the polymerization mode. EMBO J. 2013; 32:1322–1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gao D., McHenry C.S.. τ binds and organizes Escherichia coli replication proteins through distinct domains. Partial proteolysis of terminally tagged τ to determine candidate domains and to assign domain V as the α binding domain. J. Biol. Chem. 2001; 276:4433–4440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gao D., McHenry C.S.. τ binds and organizes Escherichia coli replication proteins through distinct domains. Domain IV, located within the unique C terminus of τ, binds the replication fork helicase, DnaB. J. Biol. Chem. 2001; 276:4441–4446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jergic S., Ozawa K., Williams N.K., Su X.-C., Scott D.D., Hamdan S.M., Crowther J.A., Otting G., Dixon N.E.. The unstructed C-terminus of the τ subunit of Escherichia coli DNA polymerase III holoenzyme is the site of interaction with the α subunit. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007; 35:2813–2824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Drake J.W. Comparative rates of spontaneous mutation. Nature. 1969; 221:1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chandler M., Bird R.E., Caro L.. The replication time of the Escherichia coli K12 chromosome as a function of cell doubling time. J. Mol. Biol. 1975; 94:127–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Perera H.M., Behrmann M.S., Hoang J.M., Griffin W.C., Trakselis M.A.. Contacts and context that regulate DNA helicase unwinding and replisome progression. Enzymes. 2019; 45:183–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Reyes-Lamothe R., Sherratt D.J., Leake M.C.. Stoichiometry and architecture of active DNA replication machinery in Escherichia coli. Science. 2010; 328:498–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mangiameli S.M., Merrikh C.N., Wiggins P.A., Merrikh H.. Transcription leads to pervasive replisome instability in bacteria. eLife. 2017; 6:e19848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Beattie T.R., Kapadia N., Nicolas E., Uphoff S., Wollman A.J., Leake M.C., Reyes-Lamothe R.. Frequent exchange of the DNA polymerase during bacterial chromosome replication. eLife. 2017; 6:e21763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Maisnier-Patin S., Nordström K., Dasgupta S.. Replication arrests during a single round of replication of the Escherichia coli chromosome in the absence of DnaC activity. Mol. Microbiol. 2001; 42:1371–1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Labib K., Hodgson B.. Replication fork barriers: pausing for a break or stalling for time. EMBO Rep. 2007; 8:346–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pomerantz R.T., O’Donnell M.. Direct restart of a replication fork stalled by a head-on RNA polymerase. Science. 2010; 327:590–592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mettrick K.A., Grainge I.. Stability of blocked replication forks in vivo. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016; 44:657–668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Loparo J.J., Kulczyk A.W., Richardson C.C., van Oijen A.M.. Simultaneous single-molecule measurements of phage T7 replisome composition and function reveal the mechanism of polymerase exchange. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2011; 108:3584–3589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Geertsema H.J., Kulczyk A.W., Richardson C.C., van Oijen A.M.. Single-molecule studies of polymerase dynamics and stoichiometry at the bacteriophage T7 replication machinery. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2014; 111:4073–4078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lewis J.S., Spenkelink L.M., Jergic S., Wood E.A., Monachino E., Horan N.P., Duderstadt K.E., Cox M.M., Robinson A., Dixon N.E.et al.. Single-molecule visualization of fast polymerase turnover in the bacterial replisome. eLife. 2017; 6:e23932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Li Y., Chen Z., Matthews L.A., Simmons L.A., Biteen J.S.. Dynamic exchange of two essential DNA polymerases during replication and after fork arrest. Biophys. J. 2019; 116:684–693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Spenkelink L.M., Lewis J.S., Jergic S., Xu Z.-Q., Robinson A., Dixon N.E., van Oijen A.M.. Recycling of single-stranded DNA-binding protein by the bacterial replisome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019; 47:4111–4123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lewis J.S., Spenkelink L.M., Schauer G.D., Yurieva O., Mueller S.H., Natarajan V., Kaur G., Maher C., Kay C., O’Donnell M.E.et al.. Tunability of DNA polymerase stability during eukaryotic DNA replication. Mol. Cell. 2020; 77:17–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Scherr M.J., Safaric B., Duderstadt K.E.. Noise in the machine: alternative pathway sampling is the rule during DNA replication. Bioessays. 2018; 40:1700159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mueller S.H., Spenkelink L.M., van Oijen A.M.. When proteins play tag: the dynamic nature of the replisome. Biophys. Rev. 2019; 11:641–651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Oakley A.J., Prosselkov P., Wijffels G., Beck J.L., Wilce M.C.J., Dixon N.E.. Flexibility revealed by the 1.85 Å crystal structure of the β sliding-clamp subunit of Escherichia coli DNA polymerase III. Acta Crystallogr. D. 2003; 59:1192–1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mason C.E., Jergic S., Lo A.T.Y., Wang Y., Dixon N.E., Beck J.L.. Escherichia coli single-stranded DNA-binding protein: nanoESI-MS studies of salt-modulated subunit exchange and DNA binding transactions. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2013; 24:274–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Stamford N.P.J., Lilley P.E., Dixon N.E.. Enriched sources of Escherichia colil replication proteins. The dnaG primase is a zinc metalloprotein. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1992; 1132:17–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tanner N.A., Hamdan S.M., Jergic S., Loscha K.V., Schaeffer P.M., Dixon N.E., van Oijen A.M.. Single-molecule studies of fork dynamics in Escherichia coli DNA replication. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2008; 15:170–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Elvin C.M., Thompson P.R., Argall M.E., Hendry P., Stamford N.P.J., Lilley P.E., Dixon N.E.. Modified bacteriophage lambda promoter vectors for overproduction of proteins in Escherichia coli. Gene. 1990; 87:123–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kim Y., Ho S.O., Gassman N.R., Korlann Y., Landorf E.V., Collart F.R., Weiss S.. Efficient site-specific labeling of proteins via cysteines. Bioconj. Chem. 2008; 19:786–791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Geertsema H.J., Duderstadt K.E., van Oijen A.M.. Single-molecule observation of prokaryotic DNA replication. Methods Mol. Biol. 2015; 1300:219–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Spinks R.R., Spenkelink L.M., van Oijen A.M.. Single-molecule fluorescence methods to study protein exchange kinetics in supramolecular complexes. Methods Mol. Biol. 2021; 2281:49–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Monachino E., Ghodke H., Spinks R.R., Hoatson B.S., Jergic S., Xu Z.-Q., Dixon N.E., van Oijen A.M.. Design of DNA rolling-circle templates with controlled fork topology to study mechanisms of DNA replication. Anal. Biochem. 2018; 557:42–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Yao N.Y., Georgescu R.E., Finkelstein J., O’Donnell M.E.. Single-molecule analysis reveals that the lagging strand increases replisome processivity but slows replication fork progression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009; 106:13236–13241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Tanner N.A., Tolun G., Loparo J.J., Jergic S., Griffith J.D., Dixon N.E., van Oijen A.M.. E. coli DNA replication in the absence of free β clamps. EMBO J. 2011; 30:1830–1840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Park J., Jergic S., Jeon Y., Cho W.K., Lee R., Dixon N.E., Lee J.-B.. Dynamics of proofreading by the E. coli Pol III replicase. Cell Chem. Biol. 2018; 25:57–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Watkins L.P., Yang H.. Detection of intensity change points in time-resolved single-molecule measurements. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2005; 109:617–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Duderstadt K.E., Geertsema H.J., Stratmann S.A., Punter C.M., Kulczyk A.W., Richardson C.C., van Oijen A.M.. Simultaneous real-time imaging of leading and lagging strand synthesis reveals the coordination dynamics of single replisomes. Mol. Cell. 2016; 64:1035–1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hill F.R., van Oijen A.M., Duderstadt K.E.. Detection of kinetic change points in piece-wise linear single molecule motion. J. Chem. Phys. 2018; 148:123317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Monachino E., Jergic S., Lewis J.S., Xu Z.-Q., Lo A.T.Y., O'Shea V.L., Berger J.M., Dixon N.E., van Oijen A.M.. A primase-induced conformational switch controls the stability of the bacterial replisome. Mol. Cell. 2020; 79:140–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Tanner N.A., Loparo J.J., Hamdan S.M., Jergic S., Dixon N.E., van Oijen A.M.. Real-time single-molecule observation of rolling-circle DNA replication. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009; 37:e27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Georgescu R.E., Kurth I., O’Donnell M.E.. Single-molecule studies reveal the function of a third polymerase in the replisome. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2011; 19:113–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Georgescu R.E., Yao N., Indiani C., Yurieva O., O’Donnell M.E.. Replisome mechanics: lagging strand events that influence speed and processivity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014; 42:6497–6510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Graham J.E., Marians K.J., Kowalczykowski S.C.. Independent and stochastic action of DNA polymerases in the replisome. Cell. 2017; 169:1201–1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Bailey S., Eliason W.K., Steitz T.A.. Structure of hexameric DnaB helicase and its complex with a domain of DnaG primase. Science. 2007; 318:459–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Carney S.M., Gomathinayagam S., Leuba S.H., Trakselis M.A.. Bacterial DnaB helicase interacts with the excluded strand to regulate unwinding. J.Biol. Chem. 2017; 292:19001–19012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Bujalowski W., Jezewska M.J.. Interactions of Escherichia coli primary replicative helicase DnaB protein with single-stranded DNA. The nucleic acid does not wrap around the protein hexamer. Biochemistry. 1995; 34:8513–8519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Arai K., Kornberg A.. A general priming system employing only dnaB protein and primase for DNA replication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1979; 76:4308–4312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Michel B., Sandler S.J.. Replication restart in bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 2017; 199:e00102-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Windgassen T.A., Wessel S.R., Bhattacharyya B., Keck J.L.. Mechanisms of bacterial DNA replication restart. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018; 46:504–519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Wu C.A., Zechner E.L., Reems J.A., McHenry C.S., Marians K.J.. Coordinated leading- and lagging-strand synthesis at the Escherichia coli DNA replication fork. V. Primase action regulates the cycle of Okazaki fragmant synthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 1992; 267:4074–4083. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Yuan Q., McHenry C.S.. Cycling of the E. coli lagging strand polymerase is triggered exclusively by the availability of a new primer at the replication fork. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014; 42:1747–1756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Fang L., Davey M.J., O’Donnell M.. Replisome assembly at oriC, the replication origin of E. coli, reveals an explanation for initiation sites outside an origin. Mol. Cell. 1999; 4:541–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Carr K.M., Kaguni J.M.. Stoichiometry of DnaA and DnaB Protein in initiation at the Escherichia coli chromosomal origin. J. Biol. Chem. 2001; 276:44919–44925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Marszalek J., Kaguni J.M.. DnaA protein directs the binding of DnaB protein in initiation of DNA replication in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 1994; 269:4883–4890. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Sutton M.D., Carr K.M., Vicente M., Kaguni J.M.. Escherichia coli DnaA protein. The N-terminal domain and loading of DnaB helicase at the E. coli chromosomal origin. J. Biol. Chem. 1998; 273:34255–34262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Seitz H., Weigel C., Messer W.. The interaction domains of the DnaA and DnaB replication proteins of Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 2000; 37:1270–1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Felczak M.M., Simmons L.A., Kaguni J.M.. An essential tryptophan of Escherichia coli DnaA protein functions in oligomerization at the E. coli replication origin. J. Biol. Chem. 2005; 280:24627–24633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Keyamura K., Abe Y., Higashi M., Ueda T., Katayama T.. DiaA dynamics are coupled with changes in initial origin complexes leading to helicase loading. J. Biol. Chem. 2009; 284:25038–25050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Kim S., Dallmann H.G., McHenry C.S., Marians K.J.. Coupling of a replicative polymerase and helicase: a τ–DnaB interaction mediates rapid replication fork movement. Cell. 1996; 84:643–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Yuan Q., Dohrmann P.R., Sutton M.D., McHenry C.S.. DNA polymerase III, but not polymerase IV, must be bound to τ-containing DnaX complex to enable exchange into replication forks. J. Biol. Chem. 2016; 291:11727–11735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Home-built ImageJ plugins have been deposited on the Github repository for Single-molecule/Image analysis tools (https://github.com/SingleMolecule).