Abstract

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has exposed humans to the highest physical and mental risks. Thus, it is becoming a priority to probe the mental health problems experienced during the pandemic in different populations. We performed a meta-analysis to clarify the prevalence of postpandemic mental health problems. Seventy-one published papers (n = 146,139) from China, the United States, Japan, India, and Turkey were eligible to be included in the data pool. These papers reported results for Chinese, Japanese, Italian, American, Turkish, Indian, Spanish, Greek, and Singaporean populations. The results demonstrated a total prevalence of anxiety symptoms of 32.60% (95% confidence interval (CI): 29.10–36.30) during the COVID-19 pandemic. For depression, a prevalence of 27.60% (95% CI: 24.00–31.60) was found. Further, insomnia was found to have a prevalence of 30.30% (95% CI: 24.60–36.60). Of the total study population, 16.70% (95% CI: 8.90–29.20) experienced post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic. Subgroup analysis revealed the highest prevalence of anxiety (63.90%) and depression (55.40%) in confirmed and suspected patients compared with other cohorts. Notably, the prevalence of each symptom in other countries was higher than that in China. Finally, the prevalence of each mental problem differed depending on the measurement tools used. In conclusion, this study revealed the prevalence of mental problems during the COVID-19 pandemic by using a fairly large-scale sample and further clarified that the heterogeneous results for these mental health problems may be due to the nonstandardized use of psychometric tools.

Subject terms: Scientific community, Psychiatric disorders

Introduction

Since the end of 2019, the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak has continued to spread worldwide. Researchers rapidly identified the cause of COVID-19 to be the transmission of serious acute respiratory syndrome by a novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) [1]. Unfortunately, due to the lack of effective cures and vaccines, the ability of public medical systems to guard against COVID-19 is deteriorating rapidly. Although approved vaccines are now available, their safety is still a concern [2, 3]. Further, because of reports regarding the potential to be reinfected with COVID-19, public panic is still spreading even though COVID-19 transmission has been contained substantially [4]. To date, projections regarding the end of the COVID-19 pandemic around the world are still far from optimistic. There were more than 158.95 million confirmed cases and 3.30 million deaths by May 11, 2021 (supported by Johns Hopkins University), a situation that has led to unprecedented losses and stress.

COVID-19 not only threatens physical health but has also led to mental health sequelae (i.e., loss of family, job loss, social constraints and uncertainty, and fear about the future) [5–7]. In general, mental health problems, including depression and anxiety, have had major negative impacts on the public during the COVID-19 pandemic [8, 9]. Previous studies showed that mental health problems, such as depression, anxiety, insomnia, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), suddenly increased after the COVID-19 outbreak: 53.8% of respondents rated the psychological impact of the outbreak as moderate or severe; 16.5% of participants reported moderate to severe depressive symptoms; 28.8% of participants reported moderate to severe anxiety symptoms; and 24.5% of participants showed psychological stress [10]. Moreover, such mental health problems were worse in confirmed patients and healthcare workers. As a typical example, one early study revealed acute anxiety symptoms in 98.84% of confirmed patients and depression symptoms in 79.07% of confirmed cases [11]. In addition, an early investigation concerning the mental health status of 400 public health workers found that 31% of public health workers had anxiety symptoms, and 24.5% of them had depressive symptoms [12]. In this vein, it seems that the mental health sequelae of the COVID-19 pandemic warrant more attention. In addition, with the development of the epidemic situation, long-term isolation due to the increasing number of confirmed and suspected patients has caused losses to life and property, which has not only caused considerable psychological stress in the population but has also had physiological effects, such as insomnia and PTSD.

In brief, the COVID-19 pandemic has exposed public health to dramatic risks and resulted in unacceptable mental and physiological stresses. Despite considerable research, two critical concerns regarding mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemic remain. One concern in previous studies is that the conclusions regarding the prevalence of these mental health problems are highly heterogeneous, irrespective of whether they are derived from original investigations or meta-analyses [13, 14]. Another is that early investigations were almost all done during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic and thus may overestimate the scale of mental health problems. Thus, the main purpose of this study is to provide comprehensive statistical results regarding the impact of COVID-19 on individual mental health through a large-scale meta-analysis of the existing research in this field and to provide an evidence-based reference for the prevention and control of psychological crises during this pandemic. It is noteworthy that this study employs a larger data pool than any of the existing meta-analyses to date. Further, much effort has been made to perform an in-depth investigation of the patterns of mental health problems triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic, including population-, region-, and measurement-specific patterns.

Materials and methods

To improve reproducibility and standardization, all the pipelines and protocols were in line with the Cochrane Handbook and were double-checked by using the PRISMA checklist [15]. This meta-analysis has been preregistered on OSF for open access (10.17605/OSF.IO/A5VMK).

Search strategy and selection criteria

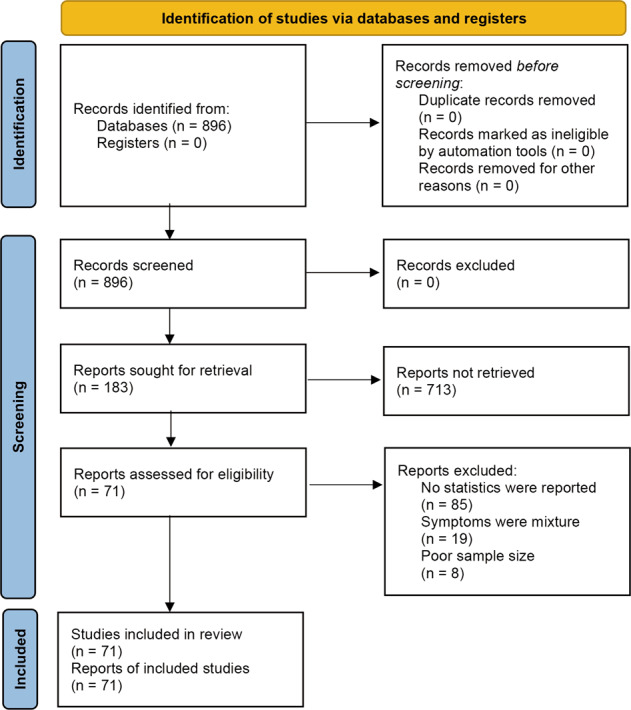

A systematic search was conducted for studies published from January 1, 2020 to July 1, 2020 (the period from the commencement of the outbreak to its initial control in China) in PubMed, EMBASE, the Cochrane Library, EBSCO, Web of Science, CNKI (Chinese database), WANGFANG DATA, the Chinese Biomedical Literature Service System, and public information release platforms (WeChat Subscription or microblogs). According to the indices of the various databases, keywords, including “2019 novel coronavirus,” “COVID-19,” “novel coronavirus pneumonia,” “NPC,” “2019-nCoV,” “mental health,” “anxiety,” “depression,” “psychological health,” “sleep,” “insomnia,” “Posttraumatic stress disorder,” and “PTSD,” were adopted to retrieve published surveys of psychological status during the COVID-19 epidemic from January 1, 2020 to July 1, 2020. In addition to identifying any target studies that may have been missed, we checked the reference list of each selected paper. The population was divided into three categories according to the probable psychological stress intensity experienced: public health workers, confirmed patients, and the general population (see Fig. 1, Supplemental information, and Table S1).

Fig. 1. Flow chart of the study selection process in the 2020 PRISMA protocol.

This flowchart is coincide with the broad-certified 2020 PRISMAstatement. Small sample size was predefined as < 30 participants.

Data extraction and quality assessment

The following data were extracted from each article by two researchers independently: study type; total number of participants; participation rate; region; percentage of physicians, nurses, and other healthcare workers screened in the survey; number of male and female participants; assessment methods used and their cutoffs; and the total number and percentage of participants who screened positive for depression, anxiety, insomnia or PTSD. If any of this information was not reported, the necessary calculations (e.g., transforming the percentage of healthcare workers to the number of healthcare workers) were performed. The accuracy of the extracted or calculated data was confirmed by comparing the collection forms of the two investigators.

In addition, two authors independently evaluated the risk of bias of the included cross-sectional studies using a modified form of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale. Potential disagreements were resolved by a third author. Specifically, the quality assessment criteria were as follows: sample representativeness and size; comparability between respondents and nonrespondents; ascertainment of depression, anxiety, and insomnia; and adequacy of the descriptive statistics. The total quality scores ranged between 0 and 5; studies scoring ≥3 points were regarded as having a low risk of bias, while studies scoring <3 points were regarded as having a high risk of bias (see Table S1).

Encoding and statistical analysis

The two investigators (XL and MZ), who performed the literature search, also extracted the data from the included studies independently. Disagreements were resolved with the third investigator (ZC) or by consensus. Then, the following variables were extracted: author, date of publication, age, gender, region, sample size, method, number of positive cases, and positivity rate. All these analytical procedures were performed with the CMA software (V3). In particular, given the heterogeneity within and between studies, random-effects models were used to estimate the average effect and its precision, which would give a more conservative estimate of the 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The I2 statistic and Cochran’s Q test were conducted to assess statistical heterogeneity.

Prior researchers held that the fixed-effects model is ideally suited to the meta-analysis of a nonheterogeneous data pool (I2 < 50%, P value ≥0.1) [16]. Conversely, the random-effects model should be used when there is heterogeneity between the studies (I2 > 50%). According to the factors that may affect the heterogeneity between studies, moderation analysis was further carried out for distinct cohorts (i.e., health workers, confirmed and suspected patients, the general population) and distinct sample sources (China, other countries). A funnel chart was created for visual inspection to determine whether the included studies showed publication bias; Egger’s test and Kendall’s test for the quantitative analysis of publication bias were also used, with p > 0.05 indicating no publication bias.

Results

In the current study, 896 Chinese and English studies were initially retrieved. According to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 71 papers were eligible for inclusion in the data pool for the meta-analysis, and the total number of respondents reached 146,139 (see Table 1 and Table S2).

Table 1.

Summary of characteristics of included studies.

| Author | Publication time | Data collection time | Region | Groups | Sample size | Age | Gender | Anxiety | Depression | Insomnia | PTSD | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Positive | Rate | Scale | Positive | Rate | Scale | Positive | Rate | Scale | Positive | Rate | Scale | |||||||

| Luo Q [23] | 2020.4.17 | 2020.2.10–20 | CN | HW | 171 | 18–41+ | 41 | 130 | 77 | 45% | GAD-7 | 68 | 39.80% | PHQ-9 | NA | NA | NA | 69 | 40.40% | PSS-10 |

| Yang L [24] | 2020.4 | 2020.2 | CN | GP | 521 | 19–60+ | 142 | 379 | 6 | 1.20% | PQEEPH | 48 | 9.20% | PQEEPH | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Zhu X [25] | 2020.5.8 | 2020.1.30–2.13 | CN | GP | 6395 | NA | 2176 | 4219 | 2812 | 43.97% | GAD-7 | 3413 | 53.37% | PHQ-9 | NA | NA | NA | 2071 | 32.38% | SRQ-20 |

| Zhu K [26] | 2020.4.30 | 2020.2.28–3.5 | CN | GP | 1264 | NA | 707 | 557 | 234 | 18.51% | SCARED | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Yin J [27] | 2020.4 | 2020.2.3–2.5 | CN | HW | 1266 | NA | 320 | 946 | 333 | 26.30% | Questionnaire on mental health of medical staff | 348 | 27.50% | Questionnaire on mental health of medical staff | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Wang C [28] | 2020.4.22 | NA | CN | GP | 896 | 17–30 | 254 | 642 | 102 | 11.38% | SCL-90 | 217 | 24.22% | SCL-90 | 105 | 11.72% | SCL-90 | NA | NA | NA |

| HuangPu M [29] | 2020.4.3 | NA | CN | HW | 326 | 28.62 ± 12.23 | 0 | 326 | 266 | 81.60% | SCL-90 | 229 | 70.25% | SCL-90 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Cao J [30] | 2020.3.20 | 2020.2 | CN | CP | 148 | 18–79 | 70 | 78 | 32 | 21.63% | SAS | 74 | 50.00% | SDS | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Liu X [31] | 2020.3.27 | 2020.2.1–18 | CN | HW | 1097 | 18–0 | 19 | 1078 | 302 | 27.53% | GAD-7 | 408 | 37.19% | PHQ-9 | 234 | 21.33% | ISI | 111 | 10.12% | SRQ-20 |

| Song W [32] | 2020.3 | 2020.1.28–2.20 | CN | GP | 1078 | ∼60 | 553 | 525 | 445 | 41. 28% | SCL-90 | 358 | 33. 21% | SCL-90 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Xu Y [33] | 2020.4.15 | 2020.2.7–2.15 | CN | HW | 360 | 23–56 | 69 | 291 | 68 | 18.90% | SAS | 138 | 38.40% | SDS | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Yuan J [34] | 2020.4.2 | 2020.1.27–2.24 | CN | CP | 145 | 45.2 ± 16.6 | 64 | 81 | 126 | 86.90% | SAS | 102 | 70.3% | SDS | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Wei L [35] | 2020.4.21 | NA | CN | HW | 2150 | NA | 873 | 1277 | 924 | 43.00% | GAD-7 | 946 | 44.00% | PHQ-9 | 774 | 36.00% | PSQI | NA | NA | NA |

| Zhong Y [36] | 2020.3 | 2020.2.11–2.12 | CN | HW | 136 | 23–55 | 19 | 117 | 83 | 61. 02% | GAD-7 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Xu Y [37] | 2020.4.16 | NA | CN | HW | 42 | NA | NA | NA | 37 | 88.10% | SAS | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Zhang Y [38] | 2020.3.11 | 2020.1.29–2.6 | CN | HW | 224 | NA | 56 | 168 | 67 | 29.90% | SAS | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Liu H [39] | 2020.2.28 | 2020.2 | CN | HW | 427 | 20–50+ | 93 | 334 | 96 | 22.48% | GAD-7 | 84 | 19.67% | PHQ-9 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Song M [40] | 2020.4.21 | 2020.1.28–2.4 | CN | GP | 3111 | 0–60+ | NA | NA | 1210 | 38.89% | GAD-7 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Li X [41] | 2020.4 | 2020.2.18–2.21 | CN | HW | 213 | ∼30–60 | 6 | 207 | 30 | 14.00% | NA | 42 | 19.70% | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Li S [42] | 2020.4 | 2020.2.6–2.8 | CN | GP | 396 | 12.82 ± 2.61 | 199 | 197 | 87 | 22.00% | SCARED | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Zhang X [43] | 2020.3.12 | 2020.1–2 | CN | HW | 133 | 20–50 | 13 | 120 | 78 | 58.65% | SCL-90 | 56 | 42.11% | SCL-90 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Cheng J [44] | 2020.3.4 | 2020.2.1–2.2 | CN | CP | 59 | NA | 24 | 35 | 28 | 47.46% | Self-made questionnaire | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Cao X [45] | 2020.4.28 | NA | CN | CP | 65 | 18–74 | NA | NA | 17 | 26.10% | SCL-90 | 13 | 20% | SCL-90 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Zhang J [11] | 2020.4.28 | NA | CN | CP | 86 | 60–92 | 39 | 47 | 85 | 98.84% | SAS | 68 | 79.07% | SDS | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Fan Y [46] | 2020.4 | 2020.2.23–2.25 | CN | GP | 4148 | 20.59 ± 1.52 | 1121 | 3027 | 2082 | 50.20% | SAS | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Fang X [47] | 2020.2 | 2020.2.1–2.6 | CN | GP | 51 | 23–77 | 25 | 26 | 12 | 23.53% | GAD-7 | 16 | 31.37% | PHQ-9 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Chen Y [48] | 2020.3 | 2020.2.3–2.16 | CN | HW | 711 | NA | 315 | 396 | 154 | 21.66% | GAD-7 | 185 | 26.02% | PHQ-9 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Chen J [49] | 2020.2.22 | NA | CN | HW | 206 | NA | 63 | 143 | 23 | 11.17% | SAS | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Chang J [50] | NA | 2020.1.31–2.3 | CN | GP | 3881 | 18+ | 1434 | 2447 | 1032 | 26.60% | GAD-7 | 821 | 21.16% | PHQ-9 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Yang Y [51] | 2020.3.13 | NA | CN | GP | 176 | NA | 58 | 118 | 71 | 40.30% | SAS | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Wang M [52] | 2020.4.28 | 2020.2.1–2.18 | CN | GP | 1501 | 50–65 | 576 | 925 | 444 | 29.58% | GAD-7 | 612 | 40.77% | PHQ-9 | 432 | 28.78% | ISI | 337 | 24.50% | SRQ-20 |

| Fang P [53] | 2020.2.29 | 2020.1.24–2.1 | CN | GP | 36,636 | NA | 13,848 | 22,788 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 8903 | 24.30% | Self-made questionnaire | NA | NA | NA |

| Li C [54] | 2020.4 | 2020.2.8–2.11 | CN | HW | 205 | NA | 30 | 175 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 104 | 50.73% | PCL-C |

| Mei J [55] | 2020.3 | 2020.1.15–2.10 | CN | CP | 70 | 36.24 ± 9.20 | 15 | 55 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 6 | 8.57% | PSQI | NA | NA | NA |

| Huo M [56] | 2020.2.26 | NA | CN | GP | 930 | NA | 434 | 496 | 253 | 27.20% | GAD-7 | 251 | 26.98% | PHQ-9 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Lei [57] | 2020.3.26 | 2020.2.4–2.10 | CN | GP | 1593 | 18–39 | 617 | 976 | 132 | 8.30% | SAS | 233 | 14.60% | SDS | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Ahmed [58] | 2020.4.1 | NA | CN | GP | 1074 | 14–68 | 571 | 503 | 311 | 29.00% | BAI | 397 | 37.10% | BDI | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Lai [17] | 2020.3.23 | 2020.1.29–2.3 | CN | HW | 1257 | NA | 293 | 964 | 560 | 44.60% | GAD-7 | 634 | 50.40% | PHQ-9 | 427 | 34% | ISI | 899 | 71.50% | IES-R |

| Wang C [10] | 2020.3.3 | 2020.1.31–2.2 | CN | GP | 1210 | 12–59 | 396 | 814 | 348 | 28.80% | DASS-21 | 200 | 16.50% | DASS-21 | NA | NA | NA | 98 | 8.10% | IES-R |

| Huang Y [59] | 2020.4.6 | 2020.2.3–2.17 | CN | GP | 7236 | NA | 7236 | 3284 | 3952 | 35.10% | GAD-7 | 1454 | 20.10% | CES-D | 1317 | 18.20% | PSQI | NA | NA | NA |

| VIDYADHARA [60] | 2020.5.12 | 2020.4.23–4.30 | CN | GP | 500 | NA | 174 | 326 | 158 | 31.50% | DASS-21 | 130 | 26.00% | DASS-21 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Tang W [61] | 2020.5.8 | 2020.2.20/27 | CN | GP | 2501 | 16–27 | 1525 | 960 | NA | NA | NA | 224 | 9.00% | PHQ-9 | 201 | 8.08% | Sleep durations | 67 | 2.70% | PCL-C |

| Wang S [62] | 2020.5.17 | 2020.1.30–2.7 | CN | HW | 123 | 20–50+ | 22 | 111 | 25 | 20.31% | SAS | 9 | 7.00% | SDS | 47 | 38% | PSQI | NA | NA | NA |

| Casagrande [63] | 2020.5.7 | 2020.3.18–4.2 | CN | GP | 2291 | 18–29 | 580 | 1708 | 735 | 32.10% | GAD-7 | NA | NA | NA | 1308 | 57.10% | PSQI | 174 | 7.60% | PCL-5 |

| Cao W [64] | 2020.3.19 | NA | CN | GP | 7143 | NA | 2168 | 4975 | 1779 | 24.00% | GAD-7 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Wu J [65] | 2020.2 | NA | CN | HW | 106 | 24–39 | 21 | 85 | 84 | 79.25% | SAS | NA | NA | NA | 68 | 64.15% | PSQI | NA | NA | NA |

| Xu M [66] | 2020.2 | NA | CN | HW | 41 | 26–35 | 4 | 37 | 16 | 39.02% | SCL-90 | 2 | 4.88% | SCL-90 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Kuang Z [67] | 2020.3 | 2020.2.8 | CN | GP | 422 | 18–50+ | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Wang Y [68] | 2020.3 | 2020.2.6–2.8 | CN | GP | 396 | 8–18 | 199 | 197 | NA | NA | NA | 41 | 10.40% | DSRS | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Cai H [69] | 2020.2 | 2020.1.31–2.4 | CN | GP | 22,302 | NA | 7398 | 14,904 | NA | NA | NA | 7226 | 32.40% | PHQ-9 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Tian Y [70] | 2020.2 | NA | CN | GP | 87 | 32.18 ± 6.89 | 47 | 40 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 2 | 2. 3% | Post-traumatic stress disorder self-rating scale |

| Huang X [71] | 2020.2.16 | NA | CN | HW | 50 | 38.28 ± 11.9 | 18 | 32 | 11 | 22.00% | SAS | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Cai F [72] | 2020.2.23 | NA | CN | HW | 48 | 28–39 | 11 | 37 | 42 | 87.50% | SCL-90 | 2 | 4.17% | SCL-90 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Qi J [12] | 2020.2 | NA | CN | HW | 400 | 21–51+ | 105 | 295 | 124 | 31.00% | SAS | 98 | 24.50% | SDS | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Andrea A [73] | NA | 2020.3.15–4.15 | Italy | GP | 131 | NA | 68 | 63 | NA | NA | NA | 30 | 22.90% | (PHQ-9) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Selçuk Özdin [74] | NA | 2020.4.14–4.16 | Turkish | GP | 343 | NA | 174 | 169 | 155 | 45.10% | HAI | 81 | 23.60% | HADS | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Deblina R [75] | NA | 2020.3.2–3.24 | Indian | GP | 662 | NA | 323 | 339 | 387 | 58.50% | Self-made questionnaire | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Jessica [76] | NA | 2020.3.25–4.6 | Spain | GP | 93 | NA | 33 | 60 | 22 | 24.00% | Telephone-based survey | 27 | 29% | Telephone-based survey | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Chrysi K [77] | 2020.5.17 | 2020.4.4–4.9 | Greece | GP | 1000 | NA | 680 | 320 | 425 | 42.50% | STAI | 743 | 74.30% | CES-D | 430 | 43.00% | RASS | NA | NA | NA |

| Rosen [78] | NA | 2020.4.15/4.17 | US | GP | 303 | 18–95 | 206 | 97 | 209 | 69.00% | BAI | NA | NA | NA | 127 | 41.90% | SUDS | NA | NA | NA |

| Du J [79] | 2020.5.31 | 2020.2.13–2.17 | CN | HW | 134 | NA | 53 | 81 | 28 | 20.10% | BAI | 17 | 12.70% | BDI-II | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Guo J [80] | NA | NA | CN | HW | 11,118 | NA | 2802 | 8316 | 1940 | 17.45% | SAS | 3497 | 31.45% | SDS | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Huang J [81] | NA | NA | CN | HW | 230 | NA | 43 | 187 | 53 | 23.04% | SAS | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Liu C [82] | NA | NA | CN | HW | 512 | NA | 79 | 433 | 64 | 12.50% | SAS | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Liu Z [83] | NA | NA | CN | HW | 4679 | NA | 828 | 3852 | 753 | 16.10% | SAS | 1619 | 34.60% | SDS | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Lu W [84] | 2020.3.21 | 2020.2.25–2.26 | CN | HW | 2299 | NA | 514 | 1785 | 569 | 24.70% | HAMA | 268 | 11.70% | HAHD | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Qi J [85] | 2020.5.13 | NA | CN | HW | 1306 | NA | 256 | 1050 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 594 | 45.50% | AISPSQI | NA | NA | NA |

| Zhang C [86] | 2020.3.27 | 2020.1.29–2.3 | CN | HW | 1563 | NA | 270 | 1293 | 698 | 44.70% | GAD-7 | 792 | 50.70% | PHQ-9 | 564 | 36.10% | ISI | NA | NA | NA |

| Zhang W [87] | 2020.3.30 | NA | CN | HW | 2182 | NA | 781 | 1401 | 228 | 10.40% | GAD-2 | 232 | 10.60% | PHQ-2 | 739 | 33.90% | ISI | NA | NA | NA |

| Zhu Z [88] | NA | NA | CN | HW | 5062 | NA | 759 | 4303 | 1218 | 24.06% | GAD-7 | 681 | 13.45% | PHQ-9 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Tan B [89] | 2020.4.6 | 2020.2.19–3.13 | Singapore | HW | 470 | NA | 149 | 321 | 68 | 14.50% | DASS-21 | 42 | 8.90% | DASS-21 | NA | NA | NA | 36 | 7.70% | IES-R |

All studies are cross-sectional. The absolute number of patients for each category is included within the parentheses.

W healthcare workers, GP general people, CP confirmed patients, CH China, US United States, NA not available.

Heterogeneity test

The results of the heterogeneity test on the prevalence of mental problems in patients with COVID-19 showed that the heterogeneity across studies was large (I2 > 98%, P < 0.05), which suggested that the random-effects model was needed to analyze the total effect. Importantly, to increase the robustness of the results and reduce the heterogeneity between studies, population, nationality, and subgroup were analyzed as possible moderators.

Prevalence of mental problems

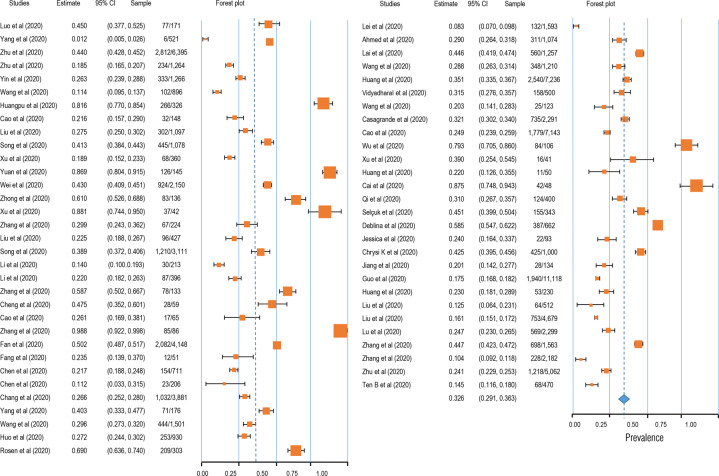

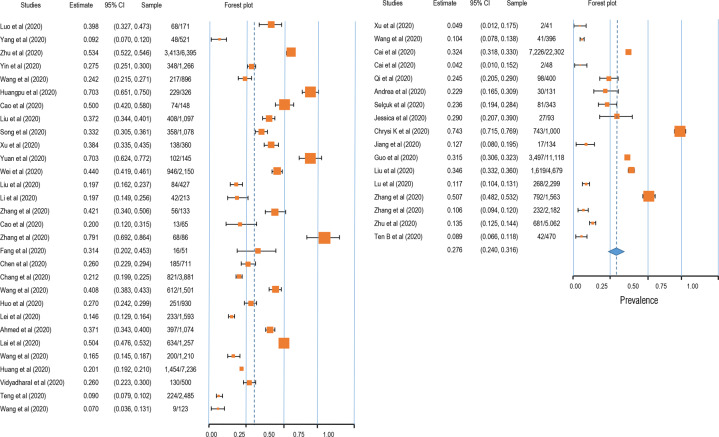

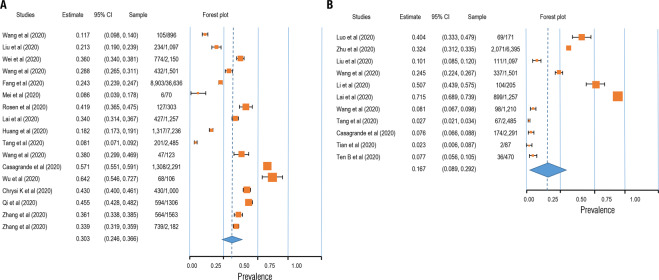

Four symptoms related to stress were selected as the mental problems, and the related symptoms and symptom groups were analyzed according to the definitions given in each study. The prevalence of anxiety was 32.6% (95% CI: 29.1–36.3; N = 86,035, see Fig. 2). In addition, the prevalence of depression was 27.60% (95% CI: 24.0–31.6; N = 90,156, see Fig. 3). Likewise, insomnia prevalence during the COVID-19 pandemic was 30.30% (95% CI: 24.6–36.6; N = 62,202, see Fig. 4A). Finally, 16.70% of participants were found to meet the criteria for PTSD during the COVID-19 pandemic in this meta-analysis (95% CI: 8.9–29.2; N = 17,169, see Fig. 4B).

Fig. 2. Forest plot for meta-analytic results of the prevalence of anxiety symptoms.

The squares colored by orange represent the point estimation foreffect towards corresponding study, with the large square size for high effect size. The orange diamond represent meta-analytic effect size.

Fig. 3. Forest plot for meta-analytic results of the prevalence of depression symptoms.

The squares colored by orange represent the point estimation foreffect towards corresponding study, with the large square size for high effect size. The orange diamond represent meta-analytic effect size.

Fig. 4. Forest plot for meta-analytic results of the prevalence of insomnia and PTSD symptoms.

The squares colored by orange represent the point estimation for effect towards corresponding study, with the large square size for high effect size. The orange diamond represent meta-analytic effect size.

Moderation analysis

Given the high heterogeneity, we assumed that there were some potential moderators, including the cohort (confirmed patients, healthcare workers, and the general population), region (China and other countries), and measurement tool. The results demonstrated a significantly higher prevalence of mental health problems in confirmed patients than in others (see Table S3). Further, the prevalence of mental health problems was found to be lower in China than in other countries. In addition, these findings derived from the moderation analysis revealed the moderating role of the measurement tool, with the results varying significantly across different scales (see Table S3 and Figs. S1–3).

Publication bias assessment

A funnel plot was first used for qualitative analysis of the publication bias. As shown in Figure S4, a symmetrical distribution was found for the four psychological symptoms. In addition, Begg’s rank test was performed to quantitatively analyze the publication bias. The results showed that there was no publication bias in the studies regarding anxiety (Kendall’s tau = 0.044, p = 0.614), depression (Kendall’s tau = −0.046, p = 0.647), insomnia (Kendall’s tau = −0.096, p = 0.592), or PTSD (Kendall’s tau = −0.145, p = 0.533).

Discussion

In this study, a meta-analysis was performed to clarify the mental health situation in the population during the COVID-19 pandemic with respect to anxiety, depression, sleep problems, and PTSD. The results showed that the detection rate of anxiety symptoms in a total of 86,035 cases was 32.6% (95% CI: 29.1–363); the detection rate of depression symptoms in a total of 90,156 cases was 27.6% (95% CI: 24.0–31.6); the detection rate of insomnia symptoms in a total of 62,202 cases was 30.3% (95% CI: 24.6–36.6); and the detection rate of PTSD symptoms was 16.7% in a total of 17,169 cases (95% CI: 8.9–29.2). Furthermore, the moderator analysis showed that mental health problems (i.e., anxiety and depression) had the highest prevalence in COVID-19 patients, and fewer anxiety, depression, and sleep problems were observed in healthcare workers than in the general population. Overall, this study provided solid evidence of the mental health situation during the COVID-19 pandemic and indicated the potential heterogeneity across cohorts, regions, and measurement tools.

Furthermore, regarding anxiety symptoms, health workers accounted for 32.7% (95% CI: 27.9–38.2) of the detection rate; the general population accounted for 29.5% (95% CI: 25.2–34.3). A total of 25.8% (95% CI: 20.4–31.0), and 25.3% (95% CI: 20.4–32.0) of depressive symptoms were found in health workers and the general population, respectively. The highest detection rate of insomnia, which was 37.3% (95% CI: 32.1–42.8%), was found in health workers, and the general population represented 26.1% of cases (95% CI: 18.2–36.1). The detection rate of PTSD was 30.6% (95% CI: 9.1–65.9) in health workers and just 9.3% (95% CI: 4–19.8) in the general population. Moving beyond previous studies, this meta-analysis covered the latest COVID-19-related articles and examined more publications than its predecessors. In contrast to the existing research conclusions, this study found that the mental health problems of healthcare workers are the same as those of the general population, suggesting that the existing research may overestimate the mental health problems of healthcare workers (i.e., one study showed that 50.4% of healthcare workers reported symptoms of depression, 44.6% symptoms of anxiety, and 34.0% insomnia) [17]. This may be because in the early stage of COVID-19, the pressures experienced by healthcare workers were considerable due to the sudden workload and lack of adequate understanding of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, in later stages, as an understanding of COVID-19 improved, healthcare workers became familiar with the situation and gained a more comprehensive understanding of the disease. This led to higher self-regulation ability under the circumstance of the epidemic even though the stress level of the first-line workers was high. Therefore, a very important conclusion of this study is that the mental health problems of healthcare workers are not as serious as previously thought, and lagging research conclusions may lead to label effects, which in turn worsen the mental health status of healthcare workers. In addition, we found that the detection rate of mental health problems in infected patients is higher in the COVID-19 pandemic than it was during the SARS outbreak [18]. For example, during SARS, the detection rate of anxiety symptoms was 35.7% (95% CI: 27.6–44.2), and that of depressed mood was 32.6% (95% CI: 24.7–40.9); in contrast, we found anxiety and depression rates of 63.9% (95% CI: 29.6–88.2) and 55.4% (95% CI: 32.8–76.0), respectively, in the COVID-19 context. During the outbreak of SARS in 2003, information dissemination was less developed than at present, and the public understanding of the virus was based on official information, which made the spread of rumors and concomitant psychological distress less likely. This shows that we should pay attention not only to the spread of the virus but also to the spread of false/fake information about the virus.

The second core finding of this study is that the detection rates of anxiety, depression, insomnia, and PTSD in other countries are higher than those in China. Existing study demonstrated the higher anxiety and depression symptoms in overseas Chinese lived in Italy than do of overseas Chinese lived in mainland China [19]. This may be because China was the first country to have an outbreak of the diseases and has taken a series of effective measures. Civil society organizations took responsibility for isolating residents in every community and helped solve practical life difficulties. At the individual level, home isolation, social distancing, and the wearing of personal protective equipment such as face masks were implemented to prevent community transmission nationwide. Due to the development of advanced technology, residents have had easy access to reliable information and medical guidance, which can reduce misinformation and the impact of rumors. The public was well educated on the seriousness of COVID-19 complied cooperatively with the national approach of hand washing, mask wearing, social distancing, and universal temperature monitoring. All citizens were keenly aware of their roles in preventing the virus from spreading. To strike a balance between epidemic control and normal social and economic operations, industrial activities have gradually resumed in phases and batches since February 8, 2020 [20]. The supply of daily necessities was kept stable in every stage of the outbreak to ensure the smooth operation of society. The WHO-China Joint Mission report said that China has rolled out perhaps the most ambitious, agile, and aggressive disease containment efforts in history [21]. By striking contrast, the number of confirmed cases outside China is quickly climbing following an exponential growth trend. The total number of COVID-19 cases outside China has reached 333,706,43, including 999,603 deaths as of September 29, 2020. Furthermore, we also conjecture that the reason why fewer pandemic impacts were seen in mainland China is that the well-established psychological rescue system strongly guards against the potential panic arising from the COVID-19 pandemic. Specifically, Chinese governmental intervention agencies provide professional psychological intervention services for patients with confirmed diseases or mental disorders, front-line medical staff, and other key groups in special places such as designated hospitals and isolated hospitals. In addition, public psychological rescue organizations offer free 24/7 on-call professional psychological advice to the public. Ultimately, massive open online courses were released to enrich the Chinese public’s understanding of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has significantly strengthened belief in the ability to control this disaster [22]. In addition, the comparative analysis of the results obtained with different measurement tools showed heterogeneity and poor consistency across the tools. Therefore, it is suggested that reliable measurement tools should be established in future research to avoid deviation in research results caused by measurement tools.

This study adjusted the prevalence of mental health problems reported in previous studies by analyzing more recent studies and thus provided a more accurate picture of the mental health status of the population. Previous studies have provided very timely and important evidence to prove that the COVID-19 pandemic is a threat to individual mental health. However, most of the surveys were performed in the early and peak periods and may overestimate the prevalence of these problems. Moreover, for the sake of timeliness in sharing research findings, low-quality articles were published in some journals. Therefore, this study also adopts the method of quality control evaluation to exclude articles with lower quality and obtain more accurate and unbiased conclusions. In general, the detection rate of mental health problems found in this study was lower than that in previous studies. There may be two reasons for this. First, stricter quality control was adopted in this study, making the analysis results more accurate and unbiased. Second, more new studies were included in this study; that is, the investigation time extended from the initial stage to the peak of the pandemic and then to the later stage of COVID-19 pandemic in the present study. Therefore, the results of this study may reflect that, with better control and understanding of the epidemic situation, people’s mental health status has improved, which is a good sign.

This study has several limitations. First, the sample sizes were not matched well, with the number of healthcare workers being smaller than the number of people from the general population. Second, the international sample was insufficient, and the research on Chinese people significantly exceeded than that on people from other countries. Third, the impact of specific epidemic status was not taken into account. In future studies, covariates can be added to the meta-analysis to control the epidemic situation of samples in different regions.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our systematic review and meta-analysis provide a timely and comprehensive synthesis of existing evidence, confirming the presence of mental health problems in patients (including suspected patients) as well as insomnia and PTSD in medical staff. The findings help to quantify staff support in the context of a pandemic when stratified and customized interventions are needed to enhance resilience and reduce vulnerability. With the continuous emergence of new evidence, we can further update the meta-analysis and perform follow-ups to analyze the factors related to the epidemic situation to facilitate national-level planning, improve the hierarchical intervention of the mental health security system, and address similar public health events in the future.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

Special appreciations to Dr. Yancheng Tang (Peking University, Beijing, China; School of Business and Management, Shanghai International Studies University, Shanghai, China) for his comments on scientific contexts. Many thanks to Xi Luo and Ke Xu (Army Medical University, Chongqing, China) for their contributions to English writing. This study was supported by the People’s Liberation Army of China (PLA) Key Researches Foundation (CWS20J007).

Author contributions

XL and ZC: conceptualization, methodology, software, writing—original draft and visualization; MZ, JZ, and RZ: writing—review and editing, methodology, or validation; PL and CZ: writing—revision; RZ and XL: replication analysis and validation; ZC: formal analysis and validation; ZC and ZF: conceptualization, supervision, project administration, and funding acquisition.

Data and code availability

Study protocols and hypotheses were preregistered on the Open Science Framework (OSF) (https://osf.io/a5vmk/). Raw data, protocols, and analysis scripts are available openly at the OSF (https://osf.io/a5vmk/).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Zhengzhi Feng, Email: fzz@tmmu.edu.cn.

Zhiyi Chen, chenzhiyi@email.swu.edu.cn.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41398-021-01501-9.

References

- 1.Lu R, Zhao X, Li J, Niu P, Yang B, Wu H, et al. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus:implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet. 2020;395:565–74. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30251-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hotez PJ, Corry BD, Bottazzi ME. COVID-19 vaccine design: the Janus face of immune enhancement. Nat Rev Immun. 2020;20:347–8. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-0323-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lurie N, Sharfstein JM, Goodman JL. The development of COVID-19 vaccines: safeguards needed. JAMA. 2020;324:439–40. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.12461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deng W, et al. Primary exposure to SARS-CoV-2 protects against reinfection in rhesus macaques. Science. 2020;369:818–23. doi: 10.1126/science.abc5343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berg-Weger M, Morley JE. Editorial: loneliness and social isolation in older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic: implications for gerontological social work. J Nutr Health Aging. 2020;24:456–8. doi: 10.1007/s12603-020-1366-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Usher K, Bhullar N, Durkin J, Gyamfi N, Jackson D. Family violence and COVID-19: increased vulnerability and reduced options for support. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2020;29:549–52. doi: 10.1111/inm.12735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dubey S, Biswas P, Ghosh R, Chatterjee S, Dubey MJ, Chatterjee S, et al. Psychosocial impact of COVID-19. Diabetes & metabolic syndrome, 2020;14,779–88. 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.05.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Choi EPH, Hui BPH, Wan EYF. Depression and anxiety in Hong Kong during COVID-19. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:10. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17103740.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang Y, Li W, Zhang Q, Zhang L, Cheung T, Xiang YT. Mental health services for older adults in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:e19. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30079-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, Tan Y, Xu L, Ho CS, et al. Immediate Psychological Responses and Associated Factors during theInitial Stage of the 2019 Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Epidemic among the General Population in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020; 17:1729. 10.3390/ijerph17051729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Jinglong Z, Rong S, Juan Y. Anxiety and depression in elderly patients during epidemic of coronavirus disease 2019 and its influencing factors. J Clin Med Pract. 2020;04:246–50. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jing Q, et al. The evaluation of sleep disturbances for chinese frontline medical workers under the outbreak of COVID-19. Sleep Med. 2020;72:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2020.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pappa S, Ntella V, Giannakas T, Giannakoulis VG, Papoutsi E, Katsaounou P. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;88:901–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wei L, Caidi Z, Jin JL, Huijuan Z, Hui W, Bixi Y, et al. Meta analysis of mental state of different groups of people during the outbreak of new coronavirus pneumonia. J Tongji Univ. 2020;02:147–54. doi: 10.16118/j.1008-0392.2020.02.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Page MJ, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hedges LV, Vevea JL. Fixed- and random-effects models in meta-analysis. Psychol Methods. 1998;3:486–504. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.3.4.486. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lai J, et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to Coronavirus Disease 2019. JAMA Network Open. 2020;3:e203976. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jonathan PR, et al. Psychiatric and neuropsychiatric presentations associated with severe coronavirus infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis with comparison to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:7. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30477-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen W, Zhan H, Hong YLJY. COVID-19 epidemic survey of mental state of overseas Chinese in Italy abstract. Psychol Mon. 2020;17:46–47+50. [Google Scholar]

- 20.The State Council of the People’s Republic of China. The notice on orderly resuming production and resuming production in enterprises. 2020. http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2020-02/09/content_5476550.htm (in Chinese). Accessed 7 Mar 2020.

- 21.WHO. Report of the WHO-China Joint Mission on Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). 2020. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/who-china-joint-mission-on-covid-19-fifinal-report.pdf. Accessed 7 Mar 2020.

- 22.Chen LL, Du MJ. Research on the improvement of psychological counseling mechanism for major public emergencies in Hubei Province during the 14th Five Year Plan period. Soc Sci Trends. 2020;8:110–8. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Qianyi L, et al. Investigation of mental health status of frontline medical staff in COVID-19 treatment hospital in Guangdong Province. Guangdong Med. 2020;41:984–90. 10.13820/j.cnki.gdyx.20200920.

- 24.Yang L, Zhang Y, Xu Y, Zheng J, Lin CQ. investigation on psychological stress in fighting against corona virus disease 2019 among community residents. Nurs Res. 2020;34:1140–5. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xiaolin Z, et al. Psychological status of school students and employees during the COVID-19 epidemic. Chin J Ment Health. 2020;34:549–54. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaiheng Z, et al. Anxiety symptom and its associates among primary school students in Hubei province during 2019 novel coronavirus diseases epidemic. Chin Public Health. 2020;36:673–6. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jiao Y, et al. Psychological investigation and analysis on mental care personnel in designated hospitals of coronavirus disease 2019. Med Philos. 2020;41:38–42+67.

- 28.Wang Z, Chen L, Li L, Zhang X, Wang YM, Xu X. Influence of COVID-2019 on mental health of medical students. J Changchun Univ Tradit Chin Med. 2020;36:1015–8. doi: 10.13463/j.cnki.cczyy.2020.05.051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huangfu M, Fu X, Wang LH. Investigation on psychological stress of frontline nurses in novel coronavirus pneumonia prevention. Chongqing Med. 2020;19:3172–6. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cao J, Wen M, Shi Y, Wu Y, He Q. Prevalence and factors associated with anxiety and depression in patients with Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) J Nurs. 2020;35:15–17. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xiaolei L, et al. Psychological state of nursing staff in a large scale of general hospital during COVID-19 epidemic. Chin J Hosp Infect. 2020;30:1641–6. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Song F, Wang X, Ju Z, Liu A, Junjie L, Wang T. Mental health status and related influencing factors during the epidemic of coronavirus disease 2019(COVID-19) Public Health Prev Med. 2020;31:23–27. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu Y, Zhao M, Tang X, Zhu X, Chen J. Correlation study between mental health and coping style of medical staff during COVID-19 epidemic. Anhui Med. 2020;41:368–71. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yuan J, Du Y, Xu W, Chen Y. Study on the anxiety and depression levels and influencing factors in patients with suspected corona virus disease 2019 in isolation. Chongqing Med. 2020;19:3156–60. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wei L, Shi L, Cao J. Psychological status of primary care workers during the COVID-19 epidemic in Shanghai. J Tongji Univ. 2020;41:155–60. doi: 10.16118/j.1008-0392.2020.02.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhong Y, Song X, Li J, Luo X, Chen W. Survey on the mental health of medical staffs in Emergency Department and Fever Clinic in Guiyang City under the Epidemic Situation of COVID-19. J Guizhou Univ Tradit Chin Med. 2020;42:16–22. doi: 10.16588/j.cnki.issn1002-1108.2020.02.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu Y. Investigation and analysis of the psychological status of the first batch of military nurses in “aiding Hubei to fight epidemic disease” and protection suggestions. Mil Med. 2020;04:313–5. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang Y, Zhang X, Peng J, Fang P. A survey on mental of medical staff fighting 2019 Novel Coronavirus Disease in Wuhan. J Trop Med. 2020;10:1371–4. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu H, Liu Q, Li J. Investigation on the participation of mental health workers fighting against COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Psychiatry. 2020;02:201–4+209. doi: 10.13479/j.cnki.jip.2020.02.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sun M, Li S, Yue HY, Li X, Li W, Xu S. analysis of Internet users’ anxiety and its influencing factors during the period of new crown pneumonia in China. World Sci Technol Modernization Chin Med. 2020;03:686–91. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li X. novel coronavirus pneumonia isolation ward hope level, mental health and influencing factors. Gen Nurs. 2020;10:1203–6. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li S, Wang Y, Yang Y, Lei X, Yang Y. Investigation on the influencing factors for anxiety related emotional disorders of children and adolescents with home quarantine during the prevalence of coronavirus disease 2019. China J Child Health. 2020;28:407–10. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang X, et al. Survey of psychological status of front-line nurses staff during the period of epidemic and intervention measures. Nurs Pract Res. 2020;17:11–14. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cheng J, Tan X, Zhang L, Zhu S, Yao H, Liu B. Research on the psychological status and influence factor of novel coronavirus pneumonia patients and people under medical observation. J Nurs Manag. 2020;20:247–51. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cao X, Tang X, Xue JY. Knowledge Investigation,prevention and psychological analysis of patients with suspected coronavirus disease 2019. J Med Univ Chongqing. 2020. 10.13406/j.cnki.cyxb.002460.

- 46.Fan Y, Wang J, Jia X, Liu X, Song YL, Zhang L. The role of mental problem evaluation and intervention in the university or college students kept at the home due to serious Corona Virus Disease-2019 epidemic during high education. Pharm Serv Res. 2020;20:81–85+91. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fang X, et al. The mental health status of the close contacts of the new coronavirus pneumonia during the epidemic period. Chin J Crit Care Med. 2020;31:60–62. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen Y, Sun J, Hu J, Chen PL, Chen S. Analysis of mental health status of residents during COVID-19 epidemic. Clin Educ Gen Pract. 2020;18:237–9+244. doi: 10.13558/j.cnki.issn1672-3686.2020.003.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen J, Yin X, Luo J, Chen F, Ren J, Gong W. investigation and analysis of psychological anxiety status of medical staff in Qingbaijiang District of Chengdu city under new epidemic situation of coronavirus pneumonia. Shandong Med. 2020;60:70–72. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chang J, Yuan Y, Wang D. Mental health status and its influencing factors among college students during the epidemic of COVID-19. J South Med Univ. 2020;40:171–6. doi: 10.12122/j.issn.1673-4254.2020.02.06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yang Y, Qi Ling Z, Zhang H. The anxiety and social support of the spouses of front-line medical staff in Suining under the new coronavirus pneumonia situation. Gen Nurs. 2020;18:940–4. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang M, Liu X, Guo H, Fan HZ, Jiang R, Tan S. Mental health of middle-aged and elderly population during outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019. J Chin Geriatr Multi Organ Dis. 2020;19:241–5. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fang P, et al. Analysis on psychological characteristics of the public in the epidemic of COVID-19. Infect Dis Inf. 2020;33:30–35. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li C, et al. Investigation and analysis of post-traumatic stress disorder in front-line nursing staff of new coronavirus. Nurse’s Continuing Educ J. 2020;35:615–8. doi: 10.16821/j.cnki.hsjx.2020.25.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mei J, et al. Analysis of psychological and sleep state of medical staff with novel coronavirus pneumonia. Med. Guidance. 2020;39:345–9. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Huo M, Yin Y, Jiang L, Duan X. Survey on the mental status of inhabitants living in Wuhan, Huanggang, Kunming and Yuxi epidemic outbreak stage of COVID-19. Int J Psychiatry. 2020;47:197–200. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lei L, et al. Comparison of prevalence and associated factors of anxiety and depression among people affected by versus people unaffected by quarantine during the COVID-19 eEpidemic in Southwestern China. Med Sci Monit. 2020;26:e924609. doi: 10.12659/MSM.924609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ahmed MZ, Ahmed O, Aibao Z, Hanbin S, Siyu L, Ahmad A. Epidemic of COVID-19 in China and associated psychological problems. Asian J Psychiatry. 2020;51:102092. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Huang, Y, Zhao, N. Mental health burden for the public affected by the COVID-19 outbreak in China: Who will be the high-risk group?. Psychol Health Med. 2020;1–12. 10.1080/13548506.2020.1754438. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 60.Vidyadhara S, Chakravarthy A, Pramod Kumar A, Sri Harsha C, Rahul R. Mental health status among the South Indian Pharmacy students during Covid-19 pandemic’s quarantine period: a cross-sectional study. MedRxiv. May 12, 2020. 10.1101/2020.05.08.20093708.

- 61.Tang W, et al. Prevalence and correlates of PTSD and depressive symptoms one month after the outbreak of the COVID-19 epidemic in a sample of home-quarantined Chinese university students. J Affect Disord. 2020;274:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang S, Xie L, Xu Y, Yu S, Yao B, Xiang D. Sleep disturbances among medical workers during the outbreak of COVID-2019. Occup Med. 2020;70:364–9. 10.1093/occmed/kqaa074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 63.Casagrande M, Favieri F, Tambelli R, Forte G. The enemy who sealed the world: effects quarantine due to the COVID-19 on sleep quality, anxiety, and psychological distress in the Italian population. Sleep Med. 2020;75:12–20. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2020.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cao W, et al. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Res. 2020;287:112934. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wu J, et al. Sleep quality survey and its influencing factors of clinical nurses in the first class of new coronavirus pneumonia. Chin Nurs Res. 2020;34:558–62. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Xu M, Zhang Y. Psychological survey of the first line supporting nurses who fight the new coronavirus pneumonia. Clin Nurs Res. 2020;34:368–70. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kuang Z, Guo K, Liu Y, Li J, Kuang YF. investigation on cognition and psychological status of new university coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan. J. Trop Med. 2020;03:283–5+288. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang Y, Yang Y, Li S, Lei X, Yang Y. Investigation on the status and influencing factors for depression symptom of children and adolescents with home quarantine during the prevalence of novel coronavirus pneumonia. Chin J Child Health. 2020;28:277–80. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cai H, et al. Novel coronavirus pneumonia epidemic-related knowledge, behaviors and psychology status among college students and their family members and. China Public Health. 2020;36:152–5. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tian Y, Zhang Y, Qian ZL. Investigation on the emotional status of villagers in a rural area of Hangzhou after the implementation of closure measures during the prevention and control of 2019–nCoV infection. Health Res. 2020;40:16–18+21. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Huang X, Ke P. Effect of standardized training novel coronavirus pneumonia on the anxiety level of the central sterile supply center. Gen Nurs. 2020;8:548–50. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cai F, Yuan Q. The psychological status of the first line medical staff in combating new coronavirus pneumonia and intervention measures. Gen Nurs. 2020;18:827–8. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Amerio A, et al. Covid-19 pandemic impact on mental health: a web-based cross-sectional survey on a sample of Italian general practitioners. Acta Bio Med. 2020;91:83–88. doi: 10.23750/abm.v91i2.9619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Özdin S, Bayrak Özdin Ş. Levels and predictors of anxiety, depression and health anxiety during COVID-19 pandemic in Turkish society: the importance of gender. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2020;66:504–11. doi: 10.1177/0020764020927051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Roy D, Tripathy S, Kar SK, Sharma N, Verma SK, Kaushal V. Study of knowledge, attitude, anxiety & perceived mental healthcare need in Indian population during COVID-19 pandemic. Asian J Psychiatry. 2020;51:102083. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Goodman-Casanova JM, Dura-Perez E, Guzman-Parra J, Cuesta-Vargas A, Mayoral-Cleries F. Telehealth home support during COVID-19 confinement for community-dwelling older adults with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia: survey study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22:e19434. doi: 10.2196/19434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kaparounaki CK, Patsali ME, Mousa DV, Papadopoulou E, Papadopoulou K, Fountoulakis KN. University students’ mental health amidst the COVID-19 quarantine in Greece. Psychiatry Res. 2020;290:113111. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zohn R, Weinberger-Litman SL, Cheskie R, Rosmarin DH, Leib L. Anxiety and distress among the first community quarantined in the U.S due to COVID-19: Psychological implications for the unfolding crisis. 2020. 10.31234/osf.io/7eq8c.

- 79.Du J, et al. Psychological symptoms among frontline healthcare workers during COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2020;20. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2020.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 80.Guo J, Liao L, Wang B, Li X, Guo L, Tong Z, et al. Psychological effects of covid-19 on hospital staff: a national cross-sectional survey in mainland China. Vasc Invest Ther. 2021;4:6–11.

- 81.Huang JZ, Han MF, Luo TD, Ren AK, Zhou XP. Mental health survey of novel coronavirus pneumonia patients receiving medical treatment in hospitals. Chin J Ind Hyg Occup Dis. 2020;38:192–5. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn121094-20200219-00063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Liu C, Yang Y, Zhang XM, Xu X, Dou QL, Zhang WW. The prevalence and influencing factors in anxiety in medical workers fighting COVID-19 in China: a cross-sectional survey. Epidemiology and infection, 2020;148:e98. 10.1017/S0950268820001107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 83.Liu Z, et al. Mental health status of doctors and nurses during COVID-19 epidemic in China. SSRN Electron J. 2020. 10.2139/ssrn.3551329.

- 84.Lu W, Wang H, Lin Y, Li L. Psychological status of medical workforce during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. Psychiatry Res. 2020;288:112936. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Qi J, Xu J, Li BZ, Huang JS, Yang Y, Zhang ZT, et al. The evaluation of sleep disturbances for Chinese frontline medical workers under the outbreak of COVID-19. Sleep medicine, 2020;72:1–4. 10.1016/j.sleep.2020.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 86.Zhang C, et al. Survey of insomnia and related social psychological factors among medical staff involved in the 2019 Novel Coronavirus Disease outbreak. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:306. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zhang WR, Wang K, Yin L, Zhao WF, Xue Q, Peng M, et al. Mental Health and Psychosocial Problems of Medical Health Workers during the COVID-19 Epidemic in China. Psychotherapy and psychosomatics. 2020;89:242–50. doi: 10.1159/000507639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zhu Z, Xu S, Wang H, Liu Z, Wu J, Li G, et al. COVID-19 in Wuhan: Sociodemographic characteristics and hospital support measures associated with the immediate psychological impact on healthcare workers. EClinicalMedicine, 2020;24:100443. 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 89.Tan BYQ, et al. Psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on health care workers in Singapore. Ann Intern Med. 2020 doi: 10.7326/M20-1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Study protocols and hypotheses were preregistered on the Open Science Framework (OSF) (https://osf.io/a5vmk/). Raw data, protocols, and analysis scripts are available openly at the OSF (https://osf.io/a5vmk/).