Abstract

Background

Historically, US in the paediatric setting has mostly been the domain of radiologists. However, in the last decade, there has been an uptake of non-radiologist point-of-care US.

Objective

To gain an overview of abdominal non-radiologist point-of-care US in paediatrics.

Materials and methods

We conducted a scoping review regarding the uses of abdominal non-radiologist point-of-care US, quality of examinations and training, patient perspective, financial costs and legal consequences following the use of non-radiologist point-of-care US. We conducted an advanced search of the following databases: Medline, Embase and Web of Science Conference Proceedings. We included published original research studies describing abdominal non-radiologist point-of-care US in children. We limited studies to English-language articles from Western countries.

Results

We found a total of 5,092 publications and selected 106 publications for inclusion: 39 studies and 51 case reports or case series on the state-of-art of abdominal non-radiologist point-of-care US, 14 on training of non-radiologists, and 1 each on possible harms following non-radiologist point-of-care US and patient satisfaction. According to included studies, non-radiologist point-of-care US is increasingly used, but no standardised training guidelines exist. We found no studies regarding the financial consequences of non-radiologist point-of-care US.

Conclusion

This scoping review supports the further development of non-radiologist point-of-care US and underlines the need for consensus on who can do which examination after which level of training among US performers. More research is needed on training non-radiologists and on the costs-to-benefits of non-radiologist point-of-care US.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00247-021-04997-x.

Keywords: Abdomen, Children, Non-radiologist, Point-of-care, Scoping review, Training, Ultrasound

Introduction

In paediatric medicine, US is a widely used imaging technique because it is noninvasive, safe and fast. Traditionally, US examinations are performed by radiologists and ultrasonographers. However, with the introduction of affordable and portable US systems, US is increasingly used as a bedside tool, or the so-called point-of-care, by non-radiologists.

To ensure good medical care for children, a high-quality US examination is of great importance, regardless of the type of physician performing the examination. This quality can be achieved by setting national and international quality standards, and by achieving consensus among US performers on who can do which examination after which level of training. At this point, there is a lack of consensus. This can partly be explained by radiologists, including paediatric radiologists, expressing their fear of losing territory. As the European Society of Radiology (ESR) position paper on US stated, “Turf battles about the use of US continue to grow as more and more specialists are claiming US as part of their everyday’s [sic] work, and the position of radiologists is progressively further undermined” [1]. As a result, non-radiologist point-of-care US has primarily developed outside the sight of radiologists, and consequently many radiologists are not aware of the status of such testing.

If radiologists and non-radiologists would be more aware of both the current uses of non-radiologist point-of-care US and the current gaps in literature, this might form a strong scientific basis for a proper consultation between the two. In a first step to address this issue, we conducted a scoping review focusing on abdominal point-of-care US performed by non-radiologists in children. The aim of this review was to gain an overview of uses of abdominal non-radiologist point-of-care US in children. Additionally, we aimed to identify gaps in the evidence, which can form the basis for future research projects to create a firm scientific base for the implementation of non-radiologist point-of-care US in paediatric medicine.

Materials and methods

The method for this scoping review was based on the framework outlined by Arksey and O’Malley [2]. The review included the following five key elements: (1) identifying the research question; (2) identifying relevant studies; (3) selecting studies; (4) charting the data; and (5) collating, summarising and reporting the results. The research topics we focussed on were:

providing an overview of the uses of abdominal non-radiologist point-of-care US, sorted by organ;

assessing the quality of examinations and training for abdominal non-radiologist point-of-care US;

assessing the patient perspective of abdominal non-radiologist point-of-care US;

financial costs of abdominal non-radiologist point-of-care US; and

legal consequences following the use of abdominal non-radiologist point-of-care US.

The search was conducted with the help of a clinical librarian (J.G.D.) on April 25, 2019, in the Medline, Embase and Web of Science Conference Proceedings databases. The search terms are shown in Online Supplementary Material 1. The inclusion criteria were original research studies on abdominal non-radiologist point-of-care US in children. We excluded studies not written in English, not published, not from Western countries (i.e. North America, Australia or Europe), studies in which both adults and children were studied but in which the data could not be separated, and studies of which no full text was available. In case the US operator was not specified and no radiologist was involved in the study, we assumed the US operator was a non-radiologist. In all other cases, the study was excluded. The full details of the study selection and data extraction can be found in the previously published review protocol [3]. We focussed only on abdominal non-radiologist point-of-care US because given the broadness of the field of non-radiologist point-of-care US, it was not feasible to perform a scoping review of the whole field (e.g., chest or musculoskeletal US).

Results

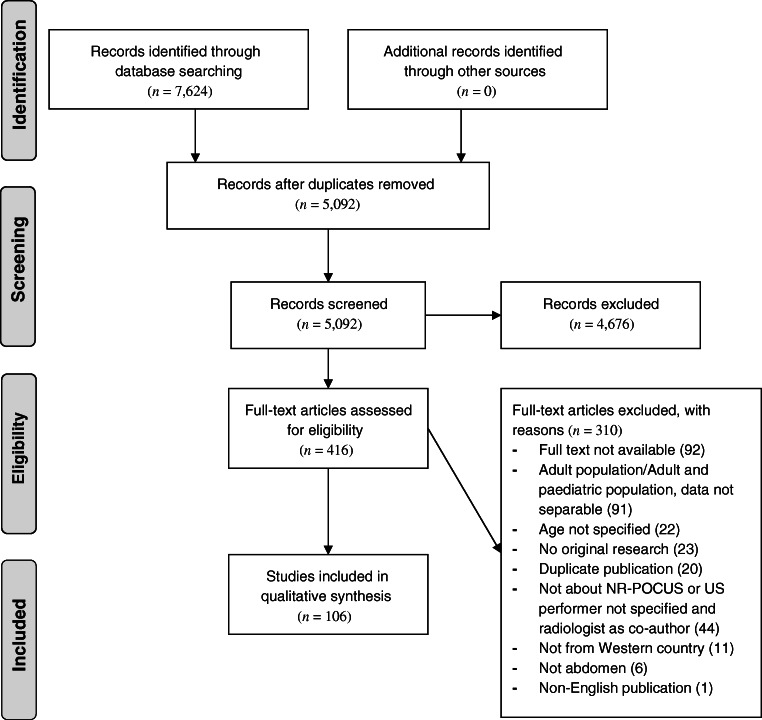

The total number of records found from the initial database searches was 7,624. After eliminating 2,532 duplications and subsequently excluding 4,676 records that did not comply with our inclusion criteria based on title and abstract, the number of potentially relevant records was further reduced to 416. Finally, after full-text screening, we included 106 articles: 39 studies and 51 case reports or case series that together gave an overview of the uses of abdominal non-radiologist point-of-care US, 14 on training of non-radiologists, and 1 each on legal consequences following non-radiologist point-of-care US and on patient satisfaction (Fig. 1). No studies on the financial costs of non-radiologist point-of-care US were identified.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA (preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses) flowchart. NR-POCUS non-radiologist point-of-care ultrasound

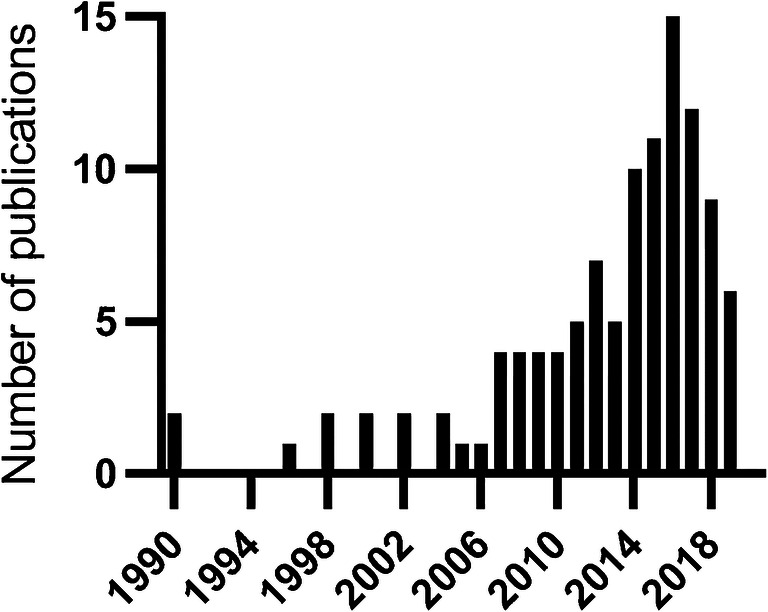

The 106 articles included in this scoping review were published between 1990 and 2019, with 50 (47%) articles published within the last 5 years (Fig. 2). Most of the studies were conducted in the United States (83%). Only four articles were published in journals with a focus on imaging, two of which were in a journal dedicated to point-of-care US in any environment or setting [4–7]. In 11 articles (10%), a radiologist was named as a co-author.

Fig. 2.

Number of publications on abdominal non-radiologist US in children per year

Overview of uses of non-radiologist point-of-care ultrasound

Of the 39 studies on abdominal non-radiologist point-of-care US, we found 9 studies on the bladder (Table 1; [8–16]), 10 on the bowel (Table 2; [17–26]), 4 on the stomach (Table 3; [27–30]), 1 on the kidney (Table 4; [31]), 4 on fluid status (Table 5; [4, 32–34]), 9 on non-radiologist point-of-care US for trauma screening (Table 6; [35–43]) and 1 “other” on umbilical artery line placement (Table 7; [44]). Next we present these studies per organ. The case reports and series are displayed in Table 8 [5, 45–94].

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies on non-radiologist US of the bladder

| Author | Year | Country | Department | n | Age (years) | Design | Indication | Ultrasound performera |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Massagli [8] | 1990 | USA | Paediatrics | 20 | 0–16 | Obs | Bladder volume | – |

| Chen [9] | 2005 | USA | Emergency | 136 | 0–2 | Obs | Bladder volume | Paediatric EDP |

| Witt [10] | 2005 | USA | Emergency | 65 | 0–1 | RCT | Bladder volume | – |

| Baumann [11] | 2008 | USA | Emergency | 45 | 0–1 | RCT | Bladder volume | Nurse |

| Dessie [12] | 2018 | USA | Emergency | 120 | 14 | RCT | Bladder volume | Paediatric EDP |

| Weill [13] | 2019 | Canada | Emergency | 201 | 0 | RCT | Bladder volume | Paediatric EDP |

| Enright [14] | 2010 | UK | Emergency | 45 | 1–4 | Obs | Dehydration | – |

| Buntsma [15] | 2012 | Australia | Emergency | 60 | 0–1 | Obs | Suprapubic aspiration | EDP |

| Gochman [16] | 1991 | USA | Emergency | 66 | 0–1 | RCT | Suprapubic aspiration | EDP |

EDP emergency department physician, Obs observational, RCT randomised controlled trial

– indicates not reported, and no radiologist as co-author

Table 2.

Characteristics of included studies on non-radiologist US of the bowel

| Author | Year | Country | Department | n | Age (years) | Design | Indication | Ultrasound performer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fox [17] | 2008 | USA | Emergency | 48 | 7–18 | Obs | Appendicitis | EDP |

| Elikashvili [18] | 2014 | USA | Emergency | 150 |

12 (SD 5.2) |

Obs | Appendicitis | Paediatric EDP |

| Doniger [19] | 2018 | USA | Emergency | 40 | 2–18 | Obs | Appendicitis | EDP |

| Nicole [20] | 2018 | Canada | Emergency | 121 | 8–14 | Obs | Appendicitis | EDP |

| Soundappan [21] | 2018 | Australia | Surgery | 65 | 3–15 | Obs | Appendicitis | Paediatric surgeon |

| Jimbo [22] | 2016 | Japan | Surgery | 84 | 4–15 | Retro | Appendicitis | Paediatrician |

| Riera [23] | 2012 | USA | Emergency | 82 | 0–10 | Obs | Intussusception | EDP |

| Lam [24] | 2014 | USA | Emergency | 44 | 2 | Retro | Intussusception | EDP |

| Gurien [25] | 2017 | USA | NICU | 17 | 0 | Obs | Motility | Surgeon |

| Doniger [26] | 2018 | USA | Emergency | 50 | 4–17 | Obs | Constipation | Clinicians |

EDP emergency department physician, NICU neonatal intensive care unit, Obs observational, Retro retrospective, SD standard deviation

Table 3.

Characteristics of included studies on non-radiologist US of the stomach

| Author | Year | Country | Department | n | Age (years)a | Design | Indication | Ultrasound performer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schmitz [27] | 2016 | Switzerland | Anaesthesiology | 18 | 6–12 | Obs | Empty stomach | Anaesthesiologist |

| Moser [28] | 2017 | Canada | Anaesthesiology | 100 | 8–16 | Obs | Empty stomach | Anaesthesiologist |

| Sivitz [29] | 2013 | USA | Emergency | 67 | 0 (IQR 14–83 days) | Obs | Pyloric hypertrophy | Paediatric EDP |

| Wyrick [30] | 2014 | USA | Surgery | 17 | – | Obs | Pyloric hypertrophy | Surgeon, paediatric EDP |

EDP emergency department physician, IQR interquartile range, Obs observational

– indicates not reported, and no radiologist as co–author

Table 4.

Characteristics of included studies on non-radiologist US of the kidney

| Author | Year | Country | Department | n | Age (years) | Design | Indication | Ultrasound performer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guedj [31] | 2015 | France | Emergency | 433 | 0 (IQR 0–1) | Obs | Hydronephrosis | EDP |

EDP emergency department physician, IQR interquartile range, Obs observational

Table 5.

Characteristics of included studies on non-radiologist US of fluid status

| Author | Year | Country | Department | n | Age (years) | Design | Indication | Ultrasound performer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chen [32] | 2007 | USA | Emergency | 72 | 0–16 | Obs | Dehydration | Paediatric EDP |

| Chen [33] | 2010 | USA | Emergency | 112 | 5 (SD 4) | Obs | Dehydration | Paediatric EDP |

| Jauregui [4] | 2014 | USA | Emergency | 113 | 0–18 | Obs | Dehydration | EDP |

| Wyrick [34] | 2015 | USA | Surgery | 31 | 0–0 | Obs | Dehydration | Surgeon |

EDP emergency department physician, Obs observational, SD standard deviation

Table 6.

Characteristics of included studies on non-radiologist US after trauma

| Author | Year | Country | Department | n | Age (years) | Design | Indication | Ultrasound performera |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ingeman [35] | 1996 | USA | Emergency | 31 | 2–18 | Obs | Free fluid | EDP |

| Thourani [36] | 1998 | USA | Emergency | 192 | 0–14 | Obs | Free fluid | Surgeon |

| Partrick [37] | 1998 | USA | Surgery | 230 | 0–17 | Obs | Free fluid | Surgeon |

| Corbett [38] | 2000 | USA | Emergency | 47 | 9 | Obs | Free fluid | EDP |

| Scaife [39] | 2013 | USA | Emergency | 88 | 2–12 | Obs | Free fluid | Surgeon |

| Menaker [40] | 2014 | USA | Emergency | 887 | 6–16 | Obs | Free fluid | EDP |

| McGaha [41] | 2019 | USA | Emergency | 292 | 11+−5 | Retro | Free fluid | – |

| Holmes [42] | 2017 | USA | Emergency | 925 | 9.7±5.3 | RCT | Free fluid | EDP |

| Brenkert [43] | 2017 | USA | Emergency | 103 | 6–14 | Retro | Free fluid | EDP |

EDP emergency department physician, Obs observational, Retro retrospective, RCT randomised controlled trial

– indicates not reported, and no radiologist as co-author

Table 8.

Case reports and series on abdominal non-radiologist US in paediatrics

| Author | Year | Country | Department | n | Age (years) | Organ | Diagnosis | Ultrasound performera |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hinds [45] | 2015 | USA | Emergency | 1 | 4 | Abdomen | Lymphangioma | EDP |

| Dingman [46] | 2007 | USA | Emergency | 1 | 4 | Aorta | Aortic coarctation | Emergency medicine resident |

| Baumann [47] | 2008 | USA | Emergency | 1 | 0 | Bladder | Bladder volume | Nurse |

| Elsamra [48] | 2011 | USA | Urology | 2 | 14–17 | Bladder | Ovarian cyst | – |

| Ng [49] | 2015 | USA | Emergency | 1 | 3 | Bladder | Urolithiasis | EDP |

| Chandra [50] | 2015 | USA | Emergency | 8 | 5–17 | Bladder | Urolithiasis | Paediatric EDP |

| Stone [51] | 2010 | USA | Emergency | 1 | 6 | Bowel | Appendicitis | EDP |

| Halm [52] | 2010 | USA | Emergency | 1 | 15 | Bowel | Appendicitis | Paediatric EDP |

| Lavine [53] | 2014 | USA | Emergency | 1 | 8 | Bowel | Appendicitis | EDP |

| Ravichandran [54] | 2016 | USA | Emergency | 1 | 3 | Bowel | Appendicitis | EDP |

| Pade [55] | 2018 | USA | Emergency | 1 | 5 | Bowel | Appendicitis | Paediatric emergency medicine fellow |

| Horowitz [56] | 2016 | USA | Emergency | 3 | 2–4 | Bowel | Foreign body | EDP |

| Leibovich [57] | 2015 | USA | Emergency | 2 | 2–13 | Bowel | Foreign body | – |

| Ramgopal [58] | 2017 | USA | Emergency | 1 | 0 | Bowel | Free fluid | Paediatric EDP |

| Alfonzo [59] | 2017 | USA | Emergency | 1 | 0 | Bowel | Hernia | – |

| Kairam [60] | 2009 | USA | Emergency | 1 | 0 | Bowel | Intussusception | EDP |

| Alletag [61] | 2011 | USA | Emergency | 1 | 0 | Bowel | Intussusception | Paediatric emergency medicine fellow |

| Halm [62] | 2013 | UK | Emergency | 1 | 2 | Bowel | Intussusception | EDP |

| Ramsey [63] | 2014 | USA | Emergency | 1 | 4 | Bowel | Intussusception | Paediatric emergency medicine fellow |

| Nelson [5] | 2014 | USA | Emergency | 1 | 6 | Bowel | Intussusception | EDP |

| Doniger [64] | 2016 | USA | Emergency | 2 | 0–2 | Bowel | Intussusception | Paediatric EDP |

| Sharma [65] | 2019 | Canada | Emergency | 2 | 0 | Bowel | Intussusception | Paediatric emergency medicine fellow |

| Garcia [66] | 2019 | USA | Emergency | 5 | 0–9 | Bowel | Malrotation/volvulus | Paediatric EDP |

| Kornblith [67] | 2016 | USA | Emergency | 2 | 3–15 | Bowel | Meckel diverticulitis | EDP |

| Brazg [68] | 2016 | USA | Emergency | 1 | 5 | Bowel | Omental torsion | EDP |

| James [69] | 2016 | Canada | Emergency | 5 | 5–14 | Bowel | Small-bowel obstruction | EDP |

| Sivitz [70] | 2013 | USA | Emergency | 1 | 0 | Bowel | Volvulus | Paediatric EDP |

| Tsung [71] | 2010 | USA | Emergency | 13 | 1–15 | Gallbladder | Cholecystitis | – |

| Shihabuddin [72] | 2013 | USA | Emergency | 1 | 10 | Gallbladder | Cholecystitis | Paediatric EDP |

| Damman [73] | 2016 | USA | Emergency | 1 | 0 | Gallbladder | Cholelithiasis | – |

| Gilmore [74] | 2004 | USA | Emergency | 1 | 0 | Kidney | Hydronephrosis | EDP |

| Hall [75] | 2011 | UK | Emergency | 1 | 13 | Kidney | Hydronephrosis | EDP |

| Schecter [76] | 2012 | USA | Emergency | 1 | 7 | Kidney | Hydronephrosis | – |

| Dunlop [77] | 2014 | USA | Emergency | 1 | 9 | Kidney | Renal carcinoma | – |

| Garcia [78] | 2019 | USA | Emergency | 1 | 7 | Kidney | Stent displacement | Paediatric EDP |

| Ginger [79] | 2009 | USA | Urology | 8 | 0–17 | Kidney | Stent placement | Urologists |

| Jamjoom [80] | 2015 | Canada | Emergency | 4 | 0–11 | Liver | Neuroblastoma | EDP |

| Pe [81] | 2016 | USA | Emergency | 1 | 13 | Ovary | cystic adenoma | EDP |

| Johnson [82] | 2006 | USA | Emergency | 1 | 15 | Ovary | Ovarian torsion | EDP |

| Pershad [83] | 2002 | USA | Emergency | 1 | 10 | Spleen | Splenic rupture | EDP |

| Parekh [84] | 2018 | USA | Anaesthesiology | 3 | 0–3 | Stomach | Empty stomach | Anaesthesiologist |

| Myatt [85] | 2018 | USA | Emergency | 3 | 2–12 | Stomach | Gastric tube placement | EDP |

| Malcolm [86] | 2009 | USA | Emergency | 8 | 0 | Stomach | Pylorus hypertrophy | EDP |

| Pershad [87] | 2000 | USA | Emergency | 1 | 16 | Trauma | Free fluid | EDP |

| Gallagher [88] | 2012 | USA | Emergency | 1 | 3 | Trauma | Free fluid | EDP |

| Root [89] | 2018 | USA | Emergency | 1 | 17 | Trauma | Free fluid | Paediatric EDP |

| Godambe [90] | 2007 | USA | Emergency | 1 | 8 | Trauma | Hydronephrosis | EDP |

| Neville [91] | 2017 | USA | Emergency | 1 | 16 | Trauma | Splenic rupture and liver laceration | Paediatric emergency medicine fellow |

| Fischer [92] | 2014 | Canada | Emergency | 1 | 12 | Uterus | Haematocolpometra | Paediatric EDP |

| Gross [93] | 2017 | USA | Emergency | 1 | 11 | Vagina | Foreign body | EDP |

| Lahham [94] | 2016 | USA | Emergency | 1 | 16 | Vena cava | Thrombus | EDP |

EDP emergency department physician

– indicates not reported, and no radiologist as co-author

Bladder

Of the nine studies on non-radiologist point-of-care US of the bladder, six assessed bladder volume, two during suprapubic aspiration; one assessed the degree of dehydration (Table 1). Of the studies regarding bladder volume, we identified four randomised controlled trials and two observational studies, mostly aiming to assess the benefit of using non-radiologist point-of-care US to obtain a valid urine sample for urinalysis. Three studies used success rates of catheterisation in infants as the end point and all found an increased success rate when using non-radiologist point-of-care US prior to catheterization [9–11]. One study used success rate of obtaining a clean-catch urine sample and did not find a difference between the two groups [13], and one study found that performing an non-radiologist point-of-care US prior to sending a child to the radiology department for a transabdominal pelvic US predicted the patient readiness for the examination and decreased time to pelvic US. The two studies regarding suprapubic aspiration both assessed whether the success rate could be improved. One study was a randomised controlled trial comparing blind suprapubic aspiration to non-radiologist point-of-care US-guided suprapubic aspiration and found a higher success rate in the US-guided group (79% vs. 52%, P=0.04) [16]. The other study demonstrated a success rate of only 53% when using non-radiologist point-of-care US for bladder scan [15]. Last, the results of the last study suggest that non-radiologist point-of-care US for bladder scan could be used to monitor urine production in children suspected of having dehydration [14].

Bowel

We identified six studies on non-radiologist point-of-care US for diagnosing appendicitis, two on intussusception, one on constipation and one on bowel motility (Table 2). Six studies assessed the diagnostic accuracy of non-radiologist point-of-care US in diagnosing appendicitis in children, all with a combination of pathology and clinical follow-up details as reference standard [17–21, 26]. For detailed analysis of diagnostic accuracy, we refer to a previously published systematic review on this topic [95]. In two of the included studies, performance of non-radiologists was compared to that of radiologists. One of these two studies demonstrated a comparable accuracy between the two raters and a sensitivity of 82% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 64–92) vs. 96% (95% CI: 83–99) and specificity of 97% (95% CI: 85–99) vs. 100% (95% CI: 87–100), respectively [21]. In contrast, the other study demonstrated that non-radiologists reported inconclusive results more often than radiologists (59% compared to 15%, respectively) [20]. Last, one study showed that the use of non-radiologist point-of-care US could decrease the length of hospital stay for children suspected of having appendicitis (length of stay decreased from 288 min (95% CI: 256–319) to 154 min (95% CI: 113–195) [18].

The two studies regarding intussusception assessed the diagnostic accuracy of non-radiologist point-of-care US, using radiology department examinations as a reference standard (either radiology US [23] or any (i.e. CT, US, barium enema) [24]. Sensitivity of non-radiologist point-of-care US ranged from 85% to 100% and specificity from 97% to 100%.

Finally, one pilot study showed that non-radiologist point-of-care US can be used to detect return of bowel function in infants with gastroschisis by assessing presence of motility [25], and one study assessed whether measuring the transrectal diameter can be used to diagnose constipation in children with abdominal pain. The latter study showed a sensitivity of 86% (95% CI: 69–96), and a specificity of 71% (95% CI: 53–85) using the Rome III criteria as a reference standard [26].

Stomach

We identified two studies on preoperative gastric content assessment and two on pyloric hypertrophy diagnosis (Table 3). The two studies on non-radiologist point-of-care US regarding the assessment of stomach filling status were from the anaesthesiology department and assessed whether non-radiologist point-of-care US could be used to assess whether a patient can be intubated safely. One of these studies used MRI findings as a reference standard [27] and the other used gastroscopy [28]. Both studies demonstrated that gastric content could be assessed with acceptable accuracy (area under the curve for measurements in the right lateral decubital position ranged from 0.73 to 0.92).

The other two studies demonstrated that non-radiologist point-of-care US is capable of accurately diagnosing pyloric hypertrophy when using radiology US as reference standard (sensitivity when identifying pylorus: 100% [95% CI: 66–100]; specificity, 100% [95% CI: 92–100]) [29]. There was no difference between measurements obtained by the non-radiologists compared to the radiologists (P>0.2) [29, 30].

Kidney

The one study on kidneys assessed the diagnostic accuracy of non-radiologist point-of-care US in diagnosing hydronephrosis. It found a sensitivity of 77% (95% CI: 58–95%) and a specificity of 97% (95% CI: 95–99%), using radiology US as reference standard (Table 4) [31].

Fluid status

We identified four studies that assessed the use of non-radiologist point-of-care US in determining fluid status (Table 5). All used the inferior vena cava/aorta ratio and compared this ratio to dehydration. Dehydration was assessed by weight loss, clinical judgement of dehydration, or bicarbonate level. Reported sensitivity ranged from 39% to 86% and reported specificity ranged from 56% to 100% [4, 32–34].

Trauma screening

We identified nine studies on non-radiologist point-of-care US after trauma (i.e. non-radiologist focused abdominal sonography for trauma [FAST]) (Table 6). Four of these studies assessed the diagnostic utility of non-radiologist point-of-care US after trauma using CT, findings during laparoscopy, or clinical outcome as a reference standard. The reported sensitivity ranged 50–100% (95% CI: 36–100) and the specificity ranged 96–100% (95% CI: 80–100) [35, 36, 38, 39]. Five of the identified studies assessed the clinical impact of non-radiologist point-of-care US on management after trauma, either by assessing the impact on number of needed CT scans [37, 39, 40, 42] or by assessing the success rate of nonoperative management (i.e. not needing an intervention) based on the non-radiologist point-of-care US result [41]. Most of these studies demonstrated that, overall, the use of CT decreased when non-radiologist FAST was increasingly used [37, 39, 40]. However, in hemodynamically stable patients, the clinical care (e.g., length of hospital stay and CT usage) did not improve by using non-radiologist FAST [42]. In addition, one study reported that in 5/88 (6%) patients, the non-radiologist FAST exam was negative, whereas the patients had a significant injury (e.g., required blood transfusion) and that in one of these cases the surgeon would have cancelled the CT based on the non-radiologist FAST exam [39].

Other

We identified one study on a procedural non-radiologist point-of-care US, regarding umbilical artery catheter placement. This study showed that non-radiologist point-of-care US can reduce the time of line placement from 139 min (standard deviation [SD]: 49 min) to 75 min (SD: 25 min) (P<0.001) [44] (Table 7).

Table 7.

Characteristics of included studies on other non-radiologist US for “other” category

| Author | Year | Country | Department | n | Age (years) | Design | Indication | Ultrasound performer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fleming [44] | 2011 | USA | NICU | 31 | 0 | RCT | Line placement in umbilical artery | Neonatologist and fellows |

NICU neonatal intensive care unit, RCT randomised controlled trial

Case reports and case series

We identified 49 case reports and case series on abdominal non-radiologist point-of-care US in children (Table 8). According to these publications, a total of 31 different diagnoses were made with the help of non-radiologist point-of-care US. In all but three publications, the diagnosis was made at the emergency department.

Quality and training

We identified 16 published articles concerning the training of non-radiologists performing non-radiologist point-of-care US in children (Table 9; [6, 7, 23, 30, 31, 38, 39, 96–104]). We subdivided these publications into three categories: (1) studies reporting efforts and outcomes of general training strategies for non-radiologist point-of-care US, (2) studies reporting training strategies for a dedicated application of non-radiologist point-of-care US and (3) surveys that reported the state of non-radiologist point-of-care US use and training in paediatric medicine. We describe these findings in the following subsections.

Table 9.

Training strategies (n=14)

| Author | Year | Country | Department | Design | Training method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohen [96] | 2012 | USA | Emergency | Survey | 76% received bedside/informal teaching, 23% received training by lectures and 16% by workshops or full-day course |

| Conlon [97] | 2015 | USA | PICU | Prospective training study (general training) |

- 2-day introductory course: didactic and hands-on training sessions with max 5 students per trainer; 4 consensus-derived training modules (procedural, hemodynamic, thoracic and abdominal) - Demonstration of skills after >25 acceptable studies per module - Reviewing of POCUS images twice a week by non-radiologist POCUS experts and once a month by radiology department |

| Corbett [38] | 2000 | USA | Emergency | Prospective training study (post trauma) | 1-day training course: didactic lectures, a videotaped session with instruction on trauma US, videotape with real-time images of pathology, hands-on workshop on healthy volunteers and finally a test using images |

| Gold [98] | 2017 | USA | Emergency | Survey | Didactics (70%), simulations in skills lab (52%), structured rotations by trained faculty (39%) or no US education (12%) |

| Guedj [31] | 2015 | France | Emergency | Prospective training study (single-organ POCUS) |

- 1–2-h didactic session (basics, physics, UTI sonography) - Hands-on training: 5 procedures |

| Hoeffe [99] | 2016 | Canada | Emergency | Survey | Radiology rotation (28%), official course (45%), no training (28%) |

| Kornblith [100] | 2015 | USA | Emergency | Survey | Not specified |

| Kwan [101] | 2019 | Canada | Emergency | Prospective training study (general training) | Via an online POCUS image interpretation learning and assessment system with 100 cases per application (e.g., FAST, lung, cardiac) with acceptable quality and showing a spectrum of pathology and normal anatomy. Included short clinical presentation, a video and image. Trainees could respond if case was normal/abnormal, and in case of abnormal the area of abnormality was to be selected, and they received feedback |

| Marin [6] | 2012 | USA | Emergency | Survey | Bedside (40%), general emergency management physician training (40%), formal course (25%), outside CME course (10%), radiology training (8%) |

| Nguyen [102] | 2016 | USA | NICU/PICU | Survey | Bedside (63%), lectures (54%), workshops (47/65%), self-study (47/43%), radiology rotation (26/5%) (NPM/PCCM, respectively) |

| Ramirez–Schremp [103] | 2008 | USA | Emergency | Survey | US rotation (33%), hands-on experience (33%), conferences (41%) |

| Reaume [7] | 2019 | USA | Emergency | Survey | Procedure-only training (34%), rotations in other departments (22%), no US training (12%) |

| Riera [23] | 2012 | USA | Emergency | Prospective training study (single-organ POCUS) |

- All trainees had >1 month of clinical instruction in performing a variety of POCUS procedures in emergency department (100–150 procedures on adults). No previous experience with bowel US - 1 h focused training session: didactic component and hands-on scanning with child as a model |

| Scaife [39] | 2013 | USA | Emergency | Prospective training study (FAST) |

- Technical instruction, viewing an instructional video, didactic session including hands-on training - At least 30 exams, of which 5 were proctored by certified paediatric sonographer or certified adult emergency medicine physician and of which at least 5 were positive for abdominal free fluid - Final competence exam (patients with ascites or ventriculoperitoneal shunt). Topics for exam: detection of intra-abdominal fluid, orientation and accuracy of probe placement, adequate scanning through fields, acceptable efficiency/time frame and ability to obtain key structures |

| Shefrin [104] | 2019 | USA | Emergency | Delphi procedure | Not applicable |

| Wyrick [30] | 2014 | USA | Surgery | Prospective training study (single-organ POCUS) | Five hands-on exams |

CME continuing medical education, FAST focused abdominal sonography for trauma, NICU neonatal intensive care unit, NPM neonatal perinatal medicine, PCCM pediatric critical care medicine, PICU paediatric intensive care unit, POCUS point-of-care ultrasound, UTI urinary tract infection

Studies reporting efforts and outcomes of general training strategies for non-radiologist point-of-care ultrasound

The first is a study from a paediatric critical care department that reported initial efforts, structure, and progress within the division and institution to train and credential physicians [97]. Physicians were trained as follows: they first participated in a 2-day introductory course with didactic lectures and hands-on training sessions. The training consisted of four modules: procedural, haemodynamic, thoracic and abdominal. After the training they were encouraged to perform at least 25 point-of-care US exams per module. Images were saved and were reviewed by point-of-care US experts once a week and by a radiologist once a month. Although only one of the 25 trainees completed the whole course, the non-radiologist point-of-care US examinations they performed contributed to the clinical management (i.e. after performing the US the clinical management was changed) and the authors reported a good experience with the reviewing process.

Another study designed an online learning platform to train paediatric emergency medicine physicians and reported the performance of the trainees [101]. The learning platform consisted of 100 cases (including short clinical presentation, video, images) per application (e.g., FAST, lung, cardiac) and trainees had to distinguish pathology from normal anatomy. In case of pathology they had to identify the location. After every case they received feedback. On average participants needed to complete 1–45 cases to reach 80% accuracy and 11–290 cases to reach 95% accuracy. The least efficient participants (95th percentile) needed to complete 60–288 cases to reach 80% accuracy and 243–1,040 to reach 95% accuracy. Most participants needed about 2–3 h to achieve the highest performance benchmark.

The last study in this category was a publication describing the efforts of a number of experts in the field of paediatric emergency medicine non-radiologist point-of-care US to reach consensus on the core applications to include in point-of-care US training for paediatric emergency medicine physicians using the Delphi method [104]. They concluded that applications of abdominal non-radiologist point-of-care US to include in training of non-radiologists were free peritoneal fluid, abscess incision and drainage, central line placement, intussusception, intrauterine pregnancy, bladder volume, and detection of foreign bodies. According to the experts, applications to exclude from training were abdominal aortic aneurism and ovarian torsion.

Studies reporting training strategies for a dedicated application of non-radiologist point-of-care ultrasound

Five articles described a training strategy for a dedicated application of non-radiologist point-of-care US. These included teaching paediatric emergency medicine fellows to measure the pyloric channel when hypertrophic pyloric stenosis is suspected [30], teaching emergency physicians to diagnose hydronephrosis in children with a urinary tract infection [31], teaching emergency physicians to diagnose ileocolic intussusception [23], training paediatric trauma surgeons to perform a FAST [39] and teaching emergency physicians to diagnose free abdominal fluid after trauma [38].

For the single-organ non-radiologist point-of-care US examinations (pyloric channel measurement, detecting hydronephrosis and detecting ileocolic intussusception), the training consisted of a short hands-on training (e.g., about five non-radiologist point-of-care US exams) with or without a preceding didactic lecture about US physics and the specific pathology. In these studies trainees were able to detect the specific pathology with acceptable accuracy (sensitivity: 77% [95% CI: 58–95], specificity: 97% (95% CI: 95–99]) at the end of the training [23, 30, 31].

For the multiple-organ non-radiologist point-of-care US examinations (i.e. post-trauma non-radiologist point-of-care US) the training was more extensive. For the detection of free fluid, trainees followed a 1-day training that consisted of didactic lectures, a videotaped session with instruction, real-time images of pathology and a hands-on workshop on healthy volunteers. After the training, trainees were able to detect free fluid in trauma patients with a sensitivity of 75% (95% CI: 36–95) and a specificity of 97% (95% CI: 81–100) [38]. For the FAST training, paediatric surgeons were trained for about 16 months: they first followed a technical instruction and hands-on training and then they had to perform at least 30 FAST exams. After this training they had to complete an exam on patients with known ascites. Sensitivity for significant amounts of free fluid was 50%, and specificity was 85%. In addition, surgeons reported they never felt they became experts, and they judged 4–10% of non-radiologist point-of-care US exams as inconclusive [39].

Surveys that reported the state of non-radiologist point-of-care ultrasound use and training in paediatric medicine

We identified eight survey studies, published between 2008 and 2018. All aimed to evaluate current state of non-radiologist point-of-care US use and education in a paediatric department (either paediatric emergency medicine, paediatric critical care medicine or neonatal medicine), all studies were performed in North America [6, 7, 96, 98–100, 102, 103]. From these surveys it becomes clear that the number of paediatric emergency departments using non-radiologist point-of-care US has increased over the last 12 years (from about 57% to 95%). However, all surveys reported a broad variety of training curricula. Reported methods of training were: bedside training, general emergency department training by a non-radiologist point-of-care US experts, following a formal course, a radiology rotation or training in a skills lab. Reported perceived barriers to implement point-of-care US training were mostly lack of training personnel, lack of time, lack of training guidelines, concerns about liability, and resistance from the radiology department.

Patient perspectives

We identified one study that evaluated the satisfaction with emergency department visits of caregivers of children who received a non-radiologist point-of-care US examination (either for diagnostic or educational purposes) compared to that of children who did not receive a non-radiologist point-of-care US examination (Table 10) [105]. Caregivers’ satisfaction was measured with a visual analogue scale. In this study, there was no difference in satisfaction between patients who did and did not receive a non-radiologist point-of-care US examination, and two-thirds of caregivers reported that they felt the examination improved the child’s interaction with the emergency department physician.

Table 10.

Patient perspectives

| Author | Year | Country | Department | Design | Ultrasound performer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lin [105] | 2018 | USA | Emergency | Observational | EDP |

EDP emergency department physician

Financial costs

No publication regarding financial costs was identified.

Legal consequences

We identified one publication concerning legal consequences following the use of non-radiologist point-of-care US (Table 11) [106]. This was a retrospective study concerning extent and quality of lawsuits. A search of the United States Westlaw database identified two lawsuits. Both lawsuits concerned the fact that the non-radiologist point-of-care US exam was not performed; in the first case, the placement of a peripherally inserted venous catheter in a child should have been checked with point-of-care US according to the accusers. In the second case, blood was found in the retroperitoneal space and it was claimed that a FAST exam should have been done. In both cases the defendants (i.e. the physicians) were acquitted.

Table 11.

Possible harms

| Author | Year | Country | Department | Design | Harm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nguyen [106] | 2016 | USA | Neonatology, paediatrics | Retro | Two lawsuits were identified, both concerning failure to perform a point-of-care US exam. Both were won by defendants (physicians) |

Retro retrospective

Discussion

We conducted this scoping review to gain an overview of current uses of abdominal non-radiologist point-of-care US in children to (1) make radiologists and non-radiologists more aware of its status and (2) prompt both categories of US performers to collaborate with each other. This scoping review demonstrates that non-radiologist point-of-care US is increasingly used and studied in paediatric care for a variety of indications. It also shows that non-radiologist point-of-care US in certain indications can have a positive impact on patient care and outcome, e.g., by reducing number of CTs needed or reducing length of hospital stay. This supports the further development of non-radiologist point-of-care US, and it underlines the need for consensus on who can do which examinations.

This scoping review also assessed the quality of examinations and training of non-radiologists performing abdominal point-of-care US in children. Regarding the quality, in some settings non-radiologists performed equal to radiologists [8, 23, 29, 30], but this was certainly not always the case [20, 31]. Moreover, clinically important missed diagnoses have been reported [39], underlining the need for proper training of non-radiologists. This scoping review makes clear that no standardised training guidelines are available, which is a key issue for the further development of non-radiologist point-of-care US.

Based on the included studies, effective training could start with a short introduction lecture, followed by an online training program (e.g., Kwan et al. [101]), which can be followed at home, and such training could conclude with a non-radiologist point-of-care US rotation in the emergency department, radiology department or both. In the included studies, a basic training of just 1–2 h was found to be sufficient for physicians performing dedicated single-organ point-of-care US exams. We, however, believe that in order to gain more generalizable skills and to ensure a high quality of all operators, a more thorough approach is needed, with paediatric radiologic input. An example of how collaboration between non-radiologists and radiologists could help to maintain quality of the non-radiologist point-of-care US exams is implementing a review process, as Conlon et al. [97] described, where radiologists and non-radiologists come together on regular basis to discuss cases.

There are some important issues to take into consideration before further implementing non-radiologist point-of-care US into daily care. First, very few studies have properly looked at missed diagnoses or incorrect diagnoses. There is a risk of non-radiologist point-of-care US leading to a delayed diagnosis and subsequently to the patient’s wellbeing being at risk. The fact that these cases have not led to published lawsuits is not evidence that this is not a problem. Second, no studies exist on the financial costs of readily available point-of-care US, which could lead to an increase in health care costs; hence a proper cost–benefit analysis is warranted. Also, little attention has been paid to the patient’s perspectives thus far. In addition, few studies compared the performance of the non-radiologists to that of radiologists. Comparing a non-radiologist to a radiologist after completing a proper training program would give more insight into the quality of US examinations. Last, from the included studies we cannot conclude what the impact of is on the clinical daily practice because the studies describe research circumstances. More research on this topic is needed before implementing changes to point-of-care US usage.

The strengths of this scoping review are our thorough search strategy with help of a clinical librarian and the cooperation of both radiologists and non-radiologists. Our scoping review has some limitations as well. First, we limited our scoping review to abdominal US. This was done to keep a clear focus; however, we suspect that a similar result can be found in other fields where non-radiologist point-of-care US is being used, such as in chest or musculoskeletal US. Second, we limited our scoping review to in-hospital use of non-radiologist point-of-care US in developed countries. Our findings might have been different in low-resource countries, where access to radiology departments can be limited. In such a setting non-radiologist point-of-care US might well be the only imaging modality available. In addition, we did not perform a quality assessment of included studies because we aimed to provide a general overview and not to answer a very specific research question through a systematic review. Also, we excluded articles including both children and adults if the data could not be separated. This might have led to a loss of relevant information.

Conclusion

This scoping review supports the further development of non-radiologist point-of-care US and underlines the need for consensus among US performers on who can do which examination after which level of training. More research on training non-radiologists and on cost–benefit of non-radiologist point-of-care US is needed.

Supplementary Information

(XLSX 12 kb)

Acknowledgements

Owen J. Arthurs is funded by a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Career Development Fellowship (NIHR-CDF-2017-10-037). This article presents independent research funded by NIHR and the views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the National Health Service, NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Declarations

Conflicts of interest

None

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.ESR Executive Council European Society of Radiology (2010) ESR position paper on ultrasound. Insights Imaging. 2009;1:27–29. doi: 10.1007/s13244-009-0005-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8:19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Wassenaer EA, Daams JG, Benninga MA, et al. The current status of non-radiologist-performed abdominal ultrasonography in paediatrics — a scoping literature review protocol. Pediatr Radiol. 2019;49:1249–1252. doi: 10.1007/s00247-019-04452-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jauregui J, Nelson D, Choo E, et al. The BUDDY (bedside ultrasound to detect dehydration in youth) study. Crit Ultrasound J. 2014;6:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s13089-014-0015-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nelson MJ, Paterson T, Raio C. Case report: transient small bowel intussusception presenting as right lower quadrant pain in a 6-year-old male. Crit Ultrasound J. 2014;6:1–4. doi: 10.1186/2036-7902-6-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marin JR, Zuckerbraun NS, Kahn JM. Use of emergency ultrasound in United States pediatric emergency medicine fellowship programs in 2011. J Ultrasound Med. 2012;31:1357–1363. doi: 10.7863/jum.2012.31.9.1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reaume M, Siuba M, Wagner M, et al. Prevalence and scope of point-of-care ultrasound education in internal medicine, pediatric, and medicine-pediatric residency programs in the United States. J Ultrasound Med. 2019;38:1433–1439. doi: 10.1002/jum.14821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Massagli TL, Jaffe KM, Cardenas DD. Ultrasound measurement of urine volume of children with neurogenic bladder. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1990;32:314–318. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1990.tb16942.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen L, Hsiao AL, Moore CL, et al. Utility of bedside bladder ultrasound before urethral catheterization in young children. Pediatrics. 2005;115:108–111. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Witt M, Baumann BM, McCans K. Bladder ultrasound increases catheterization success in pediatric patients. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12:371–374. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2004.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baumann BM, McCans K, Stahmer SA, et al. Volumetric bladder ultrasound performed by trained nurses increases catheterization success in pediatric patients. Am J Emerg Med. 2008;26:18–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2007.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dessie A, Steele D, Liu AR, et al. Point-of-care ultrasound assessment of bladder fullness for female patients awaiting radiology-performed transabdominal pelvic ultrasound in a pediatric emergency department: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2018;72:571–580. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2018.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weill O, Labrosse M, Levy A, et al. Point-of-care ultrasound before attempting clean-catch urine collection in infants: a randomized controlled trial. Can J Emerg Med. 2019;21:646–652. doi: 10.1017/cem.2019.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Enright K, Beattie T, Taheri S. Use of a hand-held bladder ultrasound scanner in the assessment of dehydration and monitoring response to treatment in a paediatric emergency department. Emerg Med J. 2010;27:731–733. doi: 10.1136/emj.2008.063271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buntsma D, Stock A, Bevan C, Babl FE. Success rate of BladderScan-assisted suprapubic aspiration. Emerg Med Australas. 2012;24:647–651. doi: 10.1111/1742-6723.12011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gochman RF, Karasic RB, Heller MB. Use of portable ultrasound to assist urine collection by suprapubic aspiration. Ann Emerg Med. 1991;20:631–635. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(05)82381-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fox JC, Solley M, Anderson CL, et al. Prospective evaluation of emergency physician performed bedside ultrasound to detect acute appendicitis. Eur J Emerg Med. 2008;15:80–85. doi: 10.1097/MEJ.0b013e328270361a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elikashvili I, Tay ET, Tsung JW. The effect of point-of-care ultrasonography on emergency department length of stay and computed tomography utilization in children with suspected appendicitis. Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21:163–170. doi: 10.1111/acem.12319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Doniger SJ, Kornblith A. Point-of-care ultrasound integrated into a staged diagnostic algorithm for pediatric appendicitis. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2018;34:109–115. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000000773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nicole M, Desjardins MP, Gravel J. Bedside sonography performed by emergency physicians to detect appendicitis in children. Acad Emerg Med. 2018;25:1035–1041. doi: 10.1111/acem.13445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Soundappan SS, Karpelowsky J, Lam A, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of surgeon performed ultrasound (SPU) for appendicitis in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2018;53:2023–2027. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2018.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jimbo K, Takeda M, Miyata E, et al. Is a pediatrician performed gray scale ultrasonography with power Doppler study safe and effective for triaging acute non-perforated appendicitis for conservative management? J Pediatr Surg. 2016;51:1952–1956. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2016.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Riera A, Hsiao AL, Langhan ML, et al. Diagnosis of intussusception by physician novice sonographers in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60:264–268. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lam SHF, Wise A, Yenter C. Emergency bedside ultrasound for the diagnosis of pediatric intussusception: a retrospective review. World J Emerg Med. 2014;5:255–258. doi: 10.5847/wjem.j.issn.1920-8642.2014.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gurien LA, Wyrick DL, Dassinger MS, et al. Use of bedside abdominal ultrasound to confirm intestinal motility in neonates with gastroschisis: a feasibility study. J Pediatr Surg. 2017;52:715–717. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2017.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Doniger SJ, Dessie A, Latronica C. Measuring the transrectal diameter on point-of-care ultrasound to diagnose constipation in children. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2018;34:154–159. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000000775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schmitz A, Schmidt AR, Buehler PK, et al. Gastric ultrasound as a preoperative bedside test for residual gastric contents volume in children. Paediatr Anaesth. 2016;26:1157–1164. doi: 10.1111/pan.12993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moser JJ, Walker AM, Spencer AO. Point-of-care paediatric gastric sonography: can antral cut-off values be used to diagnose an empty stomach? Br J Anaesth. 2017;119:943–947. doi: 10.1093/bja/aex249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sivitz AB, Tejani C, Cohen SG. Evaluation of hypertrophic pyloric stenosis by pediatric emergency physician sonography. Acad Emerg Med. 2013;20:646–651. doi: 10.1111/acem.12163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wyrick DL, Smith SD, Dassinger MS. Surgeon as educator: bedside ultrasound in hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. J Surg Educ. 2014;71:896–898. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2014.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guedj R, Escoda S, Blakime P, et al. The accuracy of renal point of care ultrasound to detect hydronephrosis in children with a urinary tract infection. Eur J Emerg Med. 2015;22:135–138. doi: 10.1097/MEJ.0000000000000158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen L, Kim Y, Santucci KA. Use of ultrasound measurement of the inferior vena cava diameter as an objective tool in the assessment of children with clinical dehydration. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14:841–845. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2007.06.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen L, Hsiao A, Langhan M, et al. Use of bedside ultrasound to assess degree of dehydration in children with gastroenteritis. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17:1042–1047. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2010.00873.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wyrick DL, Smith SD, Burford JM, et al. Surgeon-performed bedside ultrasound to assess volume status: a feasibility study. Pediatr Surg Int. 2015;31:1165–1169. doi: 10.1007/s00383-015-3798-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ingeman JE, Plewa MC, Okasinski RE, et al. Emergency physician use of ultrasonography in blunt abdominal trauma. Acad Emerg Med. 1996;3:931–937. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1996.tb03322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thourani VH, Pettitt BJ, Schmidt JA, et al. Validation of surgeon-performed emergency abdominal ultrasonography in pediatric trauma patients. J Pediatr Surg. 1998;33:322–328. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(98)90455-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Partrick DA, Bensard DD, Moore EE, et al. Ultrasound is an effective triage tool to evaluate blunt abdominal trauma in the pediatric population. J Trauma. 1998;46:357–359. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199807000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Corbett SW, Andrews HG, Baker EM, Jones WG. ED evaluation of the pediatric trauma patient by ultrasonography. Am J Emerg Med. 2000;18:244–249. doi: 10.1016/s0735-6757(00)90113-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scaife ER, Rollins MD, Barnhart DC, et al. The role of focused abdominal sonography for trauma (FAST) in pediatric trauma evaluation. J Pediatr Surg. 2013;48:1377–1383. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2013.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Menaker J, Blumberg S, Wisner DH, et al. Use of the focused assessment with sonography for trauma (FAST) examination and its impact on abdominal computed tomography use in hemodynamically stable children with blunt torso trauma. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;77:427–432. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McGaha P, Motghare P, Sarwar Z, et al. Negative focused abdominal sonography for trauma examination predicts successful nonoperative management in pediatric solid organ injury: a prospective Arizona-Texas-Oklahoma-Memphis-Arkansas + consortium study. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2019;86:86–91. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000002074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Holmes JF, Kelley KM, Wootton-Gorges SL, et al. Effect of abdominal ultrasound on clinical care, outcomes, and resource use among children with blunt torso trauma a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;317:2290–2296. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.6322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brenkert TE, Adams C, Vieira RL, Rempell RG. Peritoneal fluid localization on FAST examination in the pediatric trauma patient. Am J Emerg Med. 2017;35:1497–1499. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2017.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fleming SE, Kim JH. Ultrasound-guided umbilical catheter insertion in neonates. J Perinatol. 2011;31:344–349. doi: 10.1038/jp.2010.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hinds DF, Aponte EM, Secko M, Mehta N. Identification of a pediatric intra-abdominal cystic lymphangioma using point-of-care ultrasonography. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2015;31:62–64. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000000334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dingman JR, Zaveri PP. Severe hypertension in a 4-year-old child. Clin Pediatr Emerg Med. 2007;8:131–136. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Baumann BM, Welsh BE, Rogers CJ, Newbury K. Nurses using volumetric bladder ultrasound in the pediatric ED. Am J Nurs. 2008;108:73–76. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000315268.51274.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Elsamra SE, Gordon Z, Ellsworth PI. The pitfalls of BladderScan PVR in evaluating bladder volume in adolescent females. J Pediatr Urol. 2011;7:95–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2010.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ng C, Tsung JW. Avoiding computed tomography scans by using point-of-care ultrasound when evaluating suspected pediatric renal colic. J Emerg Med. 2015;49:165–171. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2015.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chandra A, Zerzan J, Arroyo A, et al. Point-of-care ultrasound in pediatric urolithiasis: an ED case series. Am J Emerg Med. 2015;33:1531–1534. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2015.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stone MB, Chao J. Emergency ultrasound diagnosis of acute appendicitis. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17:6563583. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Halm BM, Eakin PJ, Franke AA. Diagnosis of appendicitis by a pediatric emergency medicine attending using point-of-care ultrasound/a case report. Hawaii Med J. 2010;69:208–211. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lavine EK, Saul T, Frasure SE, Lewiss RE. Point-of-care ultrasound in a patient with perforated appendicitis. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2014;30:665–667. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000000219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ravichandran Y, Harrison P, Garrow E, Chao JH. Size matters: point-of-care ultrasound in pediatric appendicitis. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2016;32:815–816. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000000690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pade KH. Point-of-care ultrasound facilitates bedside diagnosis of appendicitis with an appendicolith in a pediatric patient. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2018;34:818–819. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000001654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Horowitz R, Cico SJ, Bailitz J. Point-of-care ultrasound: a new tool for the identification of gastric foreign bodies in children? J Emerg Med. 2016;50:99–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2015.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Leibovich S, Doniger SJ. The use of point-of-care ultrasound to evaluate for intestinal foreign bodies in the pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2015;31:731–734. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000000569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ramgopal S, Scholz S, Marin JR. Point-of-care ultrasound in acute neonatal ascites. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2017;33:599–601. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000001223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Alfonzo M, von Reinhart A, Riera A. Point-of-care ultrasound identification of an abdominal hernia. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2017;33:596–598. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000001222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kairam N, Kaiafis C, Shih R. Diagnosis of pediatric intussusception by an emergency physician-performed bedside ultrasound: a case report. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2009;25:177–180. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e31819a8a46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Alletag MJ, Riera A, Langhan ML, Chen L. Use of emergency ultrasound in the diagnostic evaluation of an infant with vomiting. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2011;27:986–989. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e318232a265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Halm BM. Reducing the time in making the diagnosis and improving workflow with point-of-care ultrasound. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2013;29:218–221. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e318280d698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ramsey KW, Halm BM. Diagnosis of intussusception using bedside ultrasound by a pediatric resident in the emergency department. Hawaii J Med Public Health. 2014;73:58–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Doniger SJ, Salmon M, Lewiss RE. Point-of-care ultrasonography for the rapid diagnosis of intussusception: a case series. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2016;32:340–342. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000000624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sharma P, Al-Sani F, Saini S, et al. Point-of-care ultrasound in pediatric diagnostic dilemmas — two atypical presentations of intussusception. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2019;35:72–74. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000001712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Garcia AM, Asad I, Tessaro MO, et al. A multi-institutional case series with review of point-of-care ultrasound to diagnose malrotation and midgut volvulus in the pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2019;35:443–447. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000001737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kornblith AE, Doniger SJ. Point-of-care ultrasonography for appendicitis uncovers two alternate diagnoses. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2016;32:262–265. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000000623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Brazg J, Haines L, Levine MC. Omental torsion mimicking perforated appendicitis in a pediatric patient: emergency bedside sonography. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34:684.e3–684.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2015.07.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.James V, Alsani FS, Fregonas C, et al. Point-of-care ultrasound in pediatric small bowel obstruction: an ED case series. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34:2464.e1–2464.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2016.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sivitz AB, Lyons R. Mid-gut volvulus identified by pediatric emergency ultrasonography. J Emerg Med. 2013;45:e173–e174. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2013.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tsung JW, Raio CC, Ramirez-Schrempp D, Blaivas M. Point-of-care ultrasound diagnosis of pediatric cholecystitis in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2010;28:338–342. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shihabuddin B, Sivitz A. Acute acalculous cholecystitis in a 10-year-old girl with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2013;29:117–121. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e31827b57e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Damman J, Doniger SJ, Atigapramoj N. Neonatal gallstones serendipitously discovered by point-of-care ultrasound in the pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2016;32:734–735. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000000622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gilmore B, Noe HN, Chin T, Pershad J. Posterior urethral valves presenting as abdominal distension and undifferentiated shock in a neonate: the role of screening emergency physician-directed bedside ultrasound. J Emerg Med. 2004;27:265–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2004.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hall DS, Nada G. Massive pelviureteric junction obstruction: the role of focused ultrasound in the emergency investigation of abdominal masses in children. Emerg Med J. 2011;28:910. doi: 10.1136/emj.2010.104471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Schecter J, Chao JH. Posterior urethral valves diagnosed by bedside ultrasound in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2012;30:633.e1–633.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2011.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dunlop JH, Cohen JS. Incidental renal mass found on focused assessment with sonography in trauma. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2014;30:752–754. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000000242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Garcia AM, Riera A, Deanehan JK. Use of point-of-care ultrasound to assess and guide renal stent repositioning in the pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2019;35:382–384. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000001767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ginger VAT, Lendvay TS. Intraoperative ultrasound: application in pediatric pyeloplasty. Urology. 2009;73:377–379. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2008.08.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jamjoom RS, Etoom Y, Solano T, et al. Emergency point-of-care ultrasound detection of cancer in the pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2015;31:602–604. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000000512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Pe M, Dickman E, Tessaro M. A novice user of pediatric emergency point-of-care ultrasonography avoids misdiagnosis in a case of chronic abdominal distention. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2016;32:116–119. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000000707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Johnson S, Fox JC, Koenig KL. Diagnosis of ovarian torsion in a hemodynamically unstable pediatric patient by bedside ultrasound in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2006;24:496–497. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2005.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Pershad J. A 10-year-old girl with shock: role of emergency bedside ultrasound in early diagnosis. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2002;18:182–184. doi: 10.1097/00006565-200206000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Parekh UR, Rajan N, Iglehart R, et al. Bedside ultrasound assessment of gastric content in children noncompliant with preoperative fasting guidelines: is it time to include this in our practice? Saudi J Anesth. 2018;12:318–320. doi: 10.4103/sja.SJA_452_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Myatt TC, Medak AJ, Lam SHF. Use of point-of-care ultrasound to guide pediatric gastrostomy tube replacement in the emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2018;34:141–144. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000001400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Malcom GE, Raio CC, Del Rios M, et al. Feasibility of emergency physician diagnosis of hypertrophic pyloric stenosis using point-of-care ultrasound: a multi-center case series. J Emerg Med. 2009;37:283–286. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2007.11.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Pershad J, Gilmore B. Serial bedside emergency ultrasound in a case of pediatric blunt abdominal trauma with severe abdominal pain. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2000;16:375–376. doi: 10.1097/00006565-200010000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Gallagher R, Vieira R, Levy J. Bedside ultrasonography in the pediatric emergency department: the focused assessment with sonography in trauma examination uncovers an occult intra-abdominal tumor. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2012;28:1107–1111. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e31826d1e86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Root JM, Abo A, Cohen J (2018) Point-of-care ultrasound evaluation of severe renal trauma in an adolescent. Pediatr Emerg Care 34:286–287 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 90.Godambe SA, Boulden T. The use of an emergency physician-directed bedside ultrasound examination to clarify a diagnosis in an 8-year-old boy with chronic abdominal pain. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2007;23:560–562. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e31812e578c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Neville DNW, Marin JR. Splenic rupture and liver laceration in an adolescent with autism spectrum disorder. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2017;33:213–215. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000001051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Fischer JW, Kwan CW. Emergency point-of-care ultrasound diagnosis of hematocolpometra and imperforate hymen in the pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2014;30:128–130. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000000080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Gross IT, Riera A. Vaginal foreign bodies: the potential role of point-of-care-ultrasound in the pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2017;33:756–759. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000001304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lahham S, Tsai L, Wilson SP, et al. Thrombosis of inferior vena cava diagnosed using point-of-care ultrasound after pediatric near-syncope. J Emerg Med. 2016;51:e89–e91. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2016.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Benabbas R, Hanna M, Shah J, Sinert R. Diagnostic accuracy of history, physical examination, laboratory tests, and point-of-care ultrasound for pediatric acute appendicitis in the emergency department: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acad Emerg Med. 2017;24:523–551. doi: 10.1111/acem.13181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Cohen JS, Teach SJ, Chapman JI. Bedside ultrasound education in pediatric emergency medicine fellowship programs in the United States. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2012;28:845–850. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e318267a771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Conlon TW, Himebauch AS, Fitzgerald JC, et al. Implementation of a pediatric critical care focused bedside ultrasound training program in a large academic PICU. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2015;16:219–226. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Gold DL, Marin JR, Haritos D, et al. Pediatric emergency medicine physicians’ use of point-of-care ultrasound and barriers to implementation: a regional pilot study. AEM Educ Train. 2017;1:325–333. doi: 10.1002/aet2.10049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hoeffe J, Desjardins MP, Fischer J, et al. Emergency point-of-care ultrasound in Canadian pediatric emergency fellowship programs: current integration and future directions. Can J Emerg Med. 2016;18:469–474. doi: 10.1017/cem.2016.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kornblith AE, Van Schaik S, Reynolds T. Useful but not used: pediatric critical care physician views on bedside ultrasound. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2015;31:186–189. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000000376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kwan C, Pusic M, Pecaric M, et al. The variable journey in learning to interpret pediatric point-of-care ultrasound images: a multicenter prospective cohort study. AEM Educ Train. 2019;4:111–122. doi: 10.1002/aet2.10375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Nguyen J, Amirnovin R, Ramanathan R, Noori S. The state of point-of-care ultrasonography use and training in neonatal-perinatal medicine and pediatric critical care medicine fellowship programs. J Perinatol. 2016;36:972–976. doi: 10.1038/jp.2016.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ramirez-Schrempp D, Dorfman DH, Tien I, Liteplo AS. Bedside ultrasound in pediatric emergency medicine fellowship programs in the United States: little formal training. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2008;24:664–667. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e3181884955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Shefrin AE, Warkentine F, Constantine E et al (2019) Consensus core point-of-care ultrasound applications for pediatric emergency medicine training. AEM Educ Train 3:251–258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 105.Lin MJ, Neuman MI, Monuteaux M, Rempell R. Does point-of-care ultrasound affect patient and caregiver satisfaction for children presenting to the pediatric emergency department? AEM Educ Train. 2018;2:33–39. doi: 10.1002/aet2.10067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Nguyen J, Cascione M, Noori S. Analysis of lawsuits related to point-of-care ultrasonography in neonatology and pediatric subspecialties. J Perinatol. 2016;36:784–786. doi: 10.1038/jp.2016.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(XLSX 12 kb)