Abstract

Generating recombinant proteins in insect cells has been made possible via the use of the Baculovirus Expression Vector System (BEVS). Despite the success of many proteins via this platform, some targets remain a challenge due to issues such as cytopathic effects, the unpredictable nature of co-infection and co-expressions, and baculovirus genome instability. Many promoters have been assayed for the purpose of expressing diverse proteins in insect cells, and yet there remains a lack of implementation of those results when reviewing the landscape of commercially available baculovirus vectors. In advancing the platform to produce a greater variety of proteins and complexes, the development of such constructs cannot be avoided. A better understanding of viral gene regulation and promoter options including viral, synthetic, and insect-derived promoters will be beneficial to researchers looking to utilize BEVS by recruiting these intricate mechanisms of gene regulation for heterologous gene expression. Here we summarize some of the developments that could be utilized to improve the expression of recombinant proteins and multi-protein complexes in insect cells.

Keywords: Baculovirus, BEVS, bacmid, insect cell, protein expression

Introduction

The Baculovirus Expression Vector System (BEVS) has been utilized as a tool to produce recombinant proteins for over 40 years [1]. Its use was first demonstrated by a group from Texas A&M University to generate human beta interferon. This work was one of the first publications demonstrating the valuable potential of this system to generate large yields of biologically active recombinant proteins [2]. Since then, significant improvements have been made to the system and it is now accepted as a common expression platform. Proteins from the BEVS have been used in biochemical, biophysical, and structural studies and gone on to benefit drug development and cancer research. Recombinant baculoviruses have also been used as a safer alternative to pesticides due to their highly specific host range and more recently have become vital tools for production of human vaccines [3,4]. Even with the diversity and development of the system over the years, the fundamental design has remained the same. Recombinant baculoviruses are generated with a foreign gene of choice placed under control of a native promoter which is then expressed during the infection cycle and proteins are released during cellular lysis. To achieve maximum expression levels, most available systems utilize very late promoters to drive production of foreign genes. Although this approach is often successful for high throughput production when large quantities of recombinant protein are needed, in certain instances the use of an alternative promoter with earlier or weaker expression can be beneficial to final protein quality and yield. Proteins which aggregate during rapid expression and those that require advanced post-translational modifications have also been shown to benefit from continuous stable expression using earlier promoters [5]. Additionally, when co-expressing proteins, the use of multiple strong very late promoters can put a burden on the cell and result in suboptimal protein yields. For these reasons, the use of alternative promoters can be beneficial for fine tuning control of foreign gene products and optimizing expression protocols. The temporal expression of baculovirus genes is believed to be primarily regulated at the transcription level through the use of various promoters, motifs, transcription factors, and a novel virus encoded RNA polymerase. A greater customization of constructs based on the properties of the desired production process will aid in the ability of researchers to capitalize the full potential of the BEVS. In this review we will discuss options outside of the typically commercialized powerful and late expressing promoters, that can harness the entire baculovirus infection cycle for optimal protein production.

Autographa californica multiple nucleopolyhedrovirus (AcMNPV)

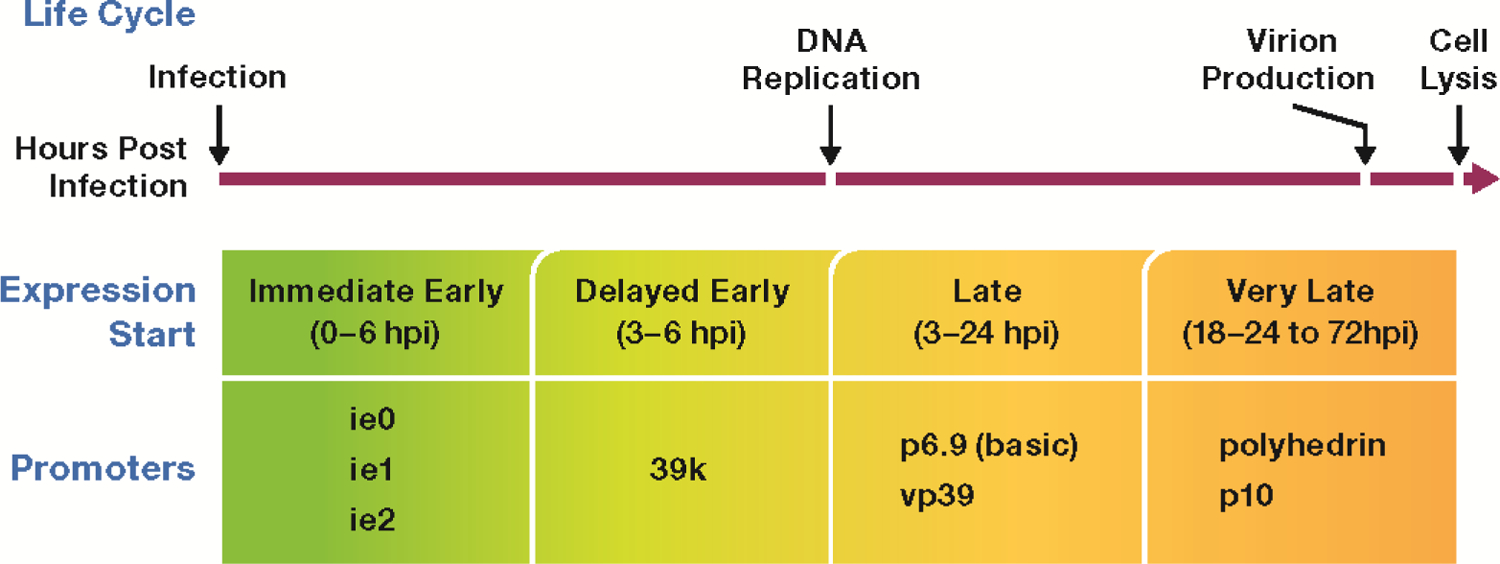

AcMNPV is a highly pathogenic baculovirus that infects lepidopteran insects and is the most commonly used baculovirus for recombinant protein production in insect cells. It consists of a double-stranded DNA genome encoding over 150 genes [6]. The infection process of the baculovirus is temporally regulated and can be divided into immediate early, delayed early, late, and very late phases. These are defined by the genes being transcribed and the hours post-infection (hpi) at which they are expressed. Immediate early genes are the first viral genes to be expressed. Studies have detected mRNA transcripts as early as 30 minutes post-infection and lasting up to six hpi [7], although some essential gene promoters are still active late in the infection cycle. Immediate early gene products are primarily transcription activators which are necessary for delayed early gene transcription. Both Immediate and delayed early genes are initially transcribed prior to viral DNA replication and utilize host RNA polymerase II [8,9]. The onset of viral DNA replication denotes the transition to late gene expression. This transition typically occurs 6 hpi and is followed by the production of budded virions. Time course transcription studies have shown that following DNA replication, late mRNA transcripts rapidly increase within the cell while there is a steady decline in host mRNA [10]. Late genes are transcribed by the novel baculovirus RNA polymerase and their expression is dependent upon viral DNA replication [11,12]. Many late genes are structural genes that are required for both budded virus (BV) at 12–18 hpi and occlusion derived virus (ODV). Beginning approximately 18 hpi and continuing until cell lysis is the very late phase. This is the final phase of infection and is associated with the formation of occluded virion and the hyper-expression of several genes including polyhedrin. Very late genes undergo a rapid burst of transcription, resulting in massive accumulation of their gene products in the cell at a time when nearly all host gene expression has diminished allowing for the devotion of cellular resources to rapid production of viral progeny [13]. The polyhedrin promoter has been considered the standard promoter of the BEV system due to this high activity.

Immediate and Delayed Early Promoters

Immediate early and delayed early promoters are activated prior to viral DNA replication. Immediate early promoters are transcribed by host cell RNA polymerase II and also utilize host transcription factors. The structural organization of immediate early and delayed early promoters differ greatly from late and very late baculovirus promoters and instead more closely resembles that of other eukaryotic promoters [14]. The most distinguishing characteristic of baculovirus immediate early promoters is the conserved CAGT motif which functions as a transcription start site and plays an essential role in regulating downstream gene expression [15]. In some instances, the immediate early promoters contain a TATA-like motif and/or an initiator sequence [9,11,16,24]. This region is recognized by host RNA polymerase II and allows for the transcription of immediate early viral genes upon infection. To determine the function of the CAGT motif, Pullen introduced site-specific mutations within this sequence of the baculovirus IE-1 promoter; alterations in the CAGT motif sequence reduced steady state levels of mRNA and decreased overall promoter expression [15]. While some delayed early promoters contain the CAGT motif, many do not, but they often require immediate early genes for transactivation.

The IE1 promoter is an immediate early promoter and is the most frequently used constitutive promoter available for baculovirus expression as it is active throughout all temporal phases as well as in uninfected insect cells [17,18]. As such, it is frequently used in transient expression plasmids; the promoters for IE0/IEI and IE2 are also used in this manner [19,20]. The 39k promoter is a delayed early promoter which is transactivated by the IE1 protein [21]. The 39k promoter can also be used transiently when co-expressed with the IE1 protein [22]. Both IE1 and 39k promoters have been shown to be particularly useful for secreted protein production [23].

Late Promoters

Late promoters are transcribed by a viral RNA polymerase which recognizes the conserved (A/G/T)TAAG late/very late promoter motif. Transcription initiates at the second nucleotide within this motif and its presence is required for promoter activity [24]. Studies investigating the function of the TAAG motif in late promoters have shown mutations within this sequence nearly abolish transcription [25,26]. Thermodynamic stability, rather than sequence specificity of its surrounding nucleotides, determines its function as a late promoter [27], suggesting the ease of strand separation and viral polymerase access aid in transcription regulation. Baculoviruses utilize a novel alpha amanitin-resistant RNA polymerase comprised of four subunits (LEF-8, LEF-4, LEF-9, and p47) which plays an important role in directing cellular resources toward viral production [28,29]. The genes encoding the polymerase subunits are transcribed early in the infection process utilizing host machinery. When the baculoviral polymerase assembles and DNA replication is nearing completion, transcription of late and very late viral genes can begin. This is accomplished through recognition of the TAAG motif by the viral RNA polymerases, allowing the viral genes to be expressed independent of host transcription machinery, preventing competition with host genes. Upon closer investigation of some late expressing factors, several were essential for or stimulated plasmid replication, which indicates that the baculoviral late gene transcription may be occurring simultaneously with the final host DNA replication, rather than after that has been completed [30].

Many late phase baculoviral transcripts encode structural proteins such as the envelope glycoprotein, gp64. The gp64 promoter is also transactivated by IE1- yet shows activity at both early and late phases [31] due to the presence of both CAGT and TAAG motifs [26]. Within BEVS the gp64 promoter is most commonly used in conjunction with gp64 fusions of heterologous proteins for viral display [32,33]. More commonly utilized late promoters include the p6.9 [34,35] and pCap [36]. The basic 6.9 kDa protein is arginine-rich and is associated with viral DNAs in the nucleocapsid while vp39 is the major capsid protein driven by pCap. Either of these promoters are generally chosen when protein expression from very late promoters has yielded dysfunctional or aggregated proteins. Earlier expression allows for better quality for some recombinant proteins and pCap yields a similar amount of protein to very late promoters when paired with hr3 enhancer due to a longer duration of moderate expression [5]. It has been speculated that the decline of host health during baculovirus infection leads to poor quality control and protein aggregation; it is not clear why that would be the case for some recombinant proteins, but not others.

Very Late Promoters

Very late promoter activity peaks 18–24 hpi and extends beyond that of late promoters. By 24 hpi, very late transcript levels exceed all others in the cell [36]. Very late promoters also are recognized by the novel baculovirus RNA polymerase, as they contain the TAAG motif and transcription start site. An AT-rich region between the TAAG transcription start site and ATG translation start codon of the polyhedrin and p10 genes, known as the burst sequence, further differentiates these very late gene promoter regions [37]. Although the sequence differs between the two promoters, its presence is important for the “burst” of very late gene expression. Mutations within the burst sequence have been shown to reduce expression by 10 to 20-fold [38,39]. A transcription regulator, very late factor 1 (Vlf-1), is believed to bind to the burst sequence and aid in the hyper-expression of downstream gene products [40].

In cells infected with native virus, polyhedrin protein forms the crystalline matrix surrounding ODVs protecting them from environmental inactivation and can accumulate up to 50% of total cell protein by the end of infection [41]. However, it is non-essential for viral infection of cultured insect cells in the laboratory, making it the preferred choice of foreign gene replacement for researchers utilizing the BEVS. The polyhedrin promoter is active very late in the infection cycle and undergoes a burst of transcriptional activity approximately 18 hpi. The polyhedrin promoter was first defined as the 69 bp upstream from the polyhedrin gene ATG by Possee & Howard [42] and later refined by Rankin [43] who identified the regions essential for polyhedrin gene product. Morris and Miller [44] demonstrated that reporter gene expression from the polyhedrin promoter was 2 to 3-fold and 10 to 20-fold higher than those observed in late and early promoters respectively. While polyhedrin mediated expression often results in significant accumulation of foreign gene products, limitations to its use can arise due to its very late activity during the period when host cells are experiencing significant cytopathology due to the release of viral proteases. The net effect of these, and presumably many other undetermined factors, can be poor protein quality due to insolubility, misfolding, or inefficient secretion [23]

The p10 protein is expressed at high levels very late in the infection cycle and is believed to play a role in occlusion body maturation and cellular lysis that is required for viral release. Weyer and Possee [37] first defined the p10 promoter as the 101 nucleotides upstream from the ATG codon of the p10 gene and suggested its use for driving foreign protein production. Since then, it has been used extensively in the BEVS for production of proteins such as gene I of cauliflower mosaic virus [45] and human interlukin2 [46]. It is also often used in conjunction with other promoters for co-expression as demonstrated by Furuta [47] for production of the Fab fragment of the 6D9 antibody and Song [48] for production of the anti-colorectal cancer monoclonal antibody CO17–1A. Compared to the polyhedrin promoter, p10 becomes active a few hours earlier and drives slightly lower transcription levels [49].

Hybrids of Very Late Promoters

Hybrid promoter constructs involve pairing full promoter regions to increase duration of expression. Pairing the p10 promoter with a variety of promoters was successful with the greatest GFP expression level coming from p10-p6.9 (TB3) which yielded 4.5 times higher expression of GFP than a polyhedrin promoter control when co-expressed with IE1 [50]. The vp39 promoter, pCap, paired with polyhedrin promoter also allows for higher expression of proteins during the late phase [36,51] compared to polyhedrin promoter which has measurable transcription at 6 hpi, but does not begin to drive hyper-expression until the very late phase. When combined with genes upstream from the polyhedrin gene (pu), ORF4, ORF5, and lef2 and an hr, the CMVmin promoter is activated even without stimulation by the Tet transactivator [52]. Mutations or deletions of any of these three genes in the pu region failed to illicit a similarly high level of expression from the CMVmin promoter. ORF4 and 5 are not well characterized, but lef2 is known to play a role in both transcription and plasmid replication [30].

Several synthetic polyhedrin promoters were made with increasing numbers (1 to 16) of burst sequences at the end of the polyhedrin promoter, in conjunction with the overexpression of vlf-1 from the ie-2 promoter. In High Five cells, 2–5 burst sequences showed greater expression of the target protein with two burst sequences being the highest performing version compared to the polyhedrin promoter alone [39].

Promoters from other baculovirus species and organisms have also been used to increase very late expression in AcMNPV. Orf46 from Spodoptera exigua baculovirus, SeMNPV, had high activity in a transcriptome analysis. The orf46 promoter exhibited a high level of late expression in AcMNPV, but when placed downstream of a polyhedrin promoter, expression of eGFP increased 2-fold [53]. Placing the leader sequence of lobster tropomyosin cDNA, L21, downstream of the polyhedrin promoter increased the expression of luciferase 7-fold higher than the polyhedrin promoter alone [54].

Enhancers

To further push the yield of baculovirus promoters, enhancers have been added to native promoters. Homologous regions (hrs) are AT-rich regions of direct repeats or palindromes which usually contain an EcoRI restriction sequence [55]. The AcMNPV genome contains nine homologous region (hr1, hr1a, hr2, hr2a, hr3, hr4a, hr4b, hr4c, and hr5) sequences. In addition to acting as enhancers, hrs also function as origins of replication [56]. When placed downstream from Drosophila hsp70 promoter, hr1 increased heterologous gene expression by acting as a binding site for a 38 kDa host protein, hr1-BP [57]. It also increased polyhedrin expression by 11-fold when placed downstream from the luciferase reporter gene [58]. Hr2 was used to increase expression from rAAV promoter RBE in Sf9 cells [59]. The IE1 promoter was able to achieve high yields in silkworm larva when paired with downstream BmNPV hr3[60] and aggregation decreased in addition to higher yields when hr3 was included with the late vp39 promoter [5]. 39K promoter was increased 10-fold by the addition of hr5 upstream along with overexpression of the IE1 gene [21]. Including the hr5 upstream of IE1 promoter increased expression of CAT by 5-fold [61]. Non-hr origins such as a portion of the p143 gene [62] have been shown to act in a similar fashion in insect and mammalian cells.

Elements for Down-Regulation

Upstream ATG codons and minicistrons located within promoter regions have been reported to play a regulatory role in baculovirus gene expression. Depending on the location and context, they can impact promoter strength and have potential use for fine tuning downstream gene expression. When point mutations were introduced into the native minicistron located within the baculovirus gp64 late promoter, mutations that interfered with minicistron function resulted in increased reporter gene levels from the downstream gp64 late promoter. When all upstream ATG codons were mutated including those within the minicistron, maximum reporter gene levels were observed suggesting that minicistrons serve a negative regulatory role in baculovirus gene expression [63]. Similarly, Luckow [64] constructed multiple recombinant baculovirus vectors with alterations in polyhedrin promoter leader sequence to better understand translational signals important for high level expression. When portions of the polyhedrin coding sequence were fused in phase with the downstream gene, higher levels of foreign protein and polyhedrin-linked mRNA were observed. Due to the unwanted effects that could arise from additional amino acids on the N terminus of recombinant proteins, the group later set out to identify the best option for producing high levels of non-fused foreign proteins [65]. By maintaining the full polyhedrin leader sequence and mutating ATG to ATT, followed directly by insertion of a foreign gene, levels of non-fused foreign genes were expressed at levels similar to wildtype polyhedrin. When the native polyhedrin start codon was mutated to ATT and in frame with the start codon of the foreign gene, the fused gene products were able to be produced, but at a lower level than the unmutated start site. An analysis of this mutation later determined the ATT to be a non-canonical translation initiation site, driving moderate yields of the fused protein [66]. Within the baculovirus genome, the leader sequence of the IEO promoter was found to include a minicistron [67] as was the region upstream of the 39K ORF [68], indicating that this regulation is occurring in each temporal phase. Synthetic alterations of these upstream regions could aid in controlling translation levels when using these alternative promoters within BEVS.

Inducible Baculovirus Promoters

Being able to control the expression timing and yield can be helpful in optimizing recombinant protein production, particularly when co-expressing chaperones or proteins which are toxic to the host. Such systems for baculovirus involve transient plasmids or stable cells with heterologous genes driven by baculoviral promoters which are turned on at some point post-infection. The promoters for the immediate early genes, IE0, IE1, and IE2, are often used for this purpose, and are constitutively expressed non-infected insect cells. The 39k promoter is a delayed early promoter which is induced by infection or overexpression of IE1. An optimal synthetic 39K promoter where the transcriptional activation region (− 310 to − 355) has been duplicated around the core promoter seems to yield higher expression levels than the immediate early genes. This region can be added before and after other promoters to increase their induction capacity post-infection [69].

Tetracycline induction is commonly used in mammalian systems and has been tweaked for use with baculovirus expression. The Tet transactivator is driven by p10 or Drosophila hsp70 promoter and the pTre-CMVmin controls the gene of interest. In this version, known colloquially as Tet-Off, the expression from pTRE-CMVmin is on until tetracycline is added and then expression of the desired protein decreases or nearly ceases with higher dosages. Alternatively, tetracycline can be added pre-infection and the gene can be turned on with a Tet-free media change. [70]. Greater control was added to the system by removing Ac-orf 5 which had previously been activating the pTRE-CMVmin independently from the Tet transactivator [71].

The complication with utilizing stress-induced promoters to induce protein expression via baculovirus is that they are often leaky due to the stress accumulated by the infection process. The Drosophila hsp70 promoter is induced by baculovirus infection, but also by temperature [72]. The Drosophila melanogaster metallothionein gene (Mtn) promoter has been shown to be copper or cadmium-inducible when incorporated into AcMNPV. Metal exposure delayed viral processes. Host protein synthesis continued slightly longer than typical and polyhedral formation was delayed 1–2 days. However, copper treatment also extended p10 and polyhedrin-mediated transcription, resulting in higher yields from those promoters [73].

Insect Host Promoters

Although some of the viral promoters mentioned above have high transcription levels, many are dependent on viral machinery that is only available late in the infection cycle. During this phase, cellular integrity is compromised due to the cytopathic effects of infection and several reports indicate protein production and processing can be compromised [17, 74,75,76]. Earlier viral promoters do exist but tend to be limited and transcriptional activity is often unimpressive. One option to overcome these barriers is the use of insect-derived promoters that are typically transcribed at earlier times in the infection cycle and can be used to mediate foreign gene expression either in recombinant baculovirus, transient plasmids, or stable cells lines. Insect-derived promoters are also beneficial to researchers looking to produce foreign genes in cell lines outside the baculovirus host range as protein expression in nonpermissive insect cells has been found to be promoter dependent [77].

Using a CAT reporter, Johnson found the silkworm Bombyx mori actin promoter provided a 24-hr temporal advantage over the polyhedrin promoter. Although reporter gene levels were found to be significantly lower for the Bombyx mori actin promoter, its earlier activity could be useful for biological pest control vectors as it would allow for more rapid accumulation of toxic proteins [78]. A similar trend was observed in silkworm larvae, suggesting the potential use of the Bombyx mori actin promoter as an earlier alternative to traditional late promoters. Similarly, the Trichoplusia ni-derived basic juvenile hormone-suppressible protein 2 (pB2) promoter becomes active earlier than conventional late viral promoters [79]. Using a pB2-p10 chimera, improved activity was shown compared to polyhedrin and p10 promoters at 24 and 48 h post-infection

The Drosophila hsp70 promoter yielded higher than conventional early viral promoters in all permissive cell lines tested [44]. Additionally, the insect-derived promoter outperformed viral promoters from all temporal categories in nonpermissive cell lines. The use of Drosophila hsp70 was later expanded by Lee [77] for baculovirus-mediated gene expression in Drosophila S2 cells. In addition to these, Bleckmann [80] found the Sf21-derived GAPDH promoter to be approximately four times higher expressing then the early viral OPie1 promoter and the ribosomal L34 promoter to have similar expression levels. However, the insect-derived promoters were still significantly lower activity than viral OPie2 and the enhanced hr5-ie1-p10 promoter.

Expressing Multiple Recombinant Proteins

The ability of the BEVS to express multiple recombinant proteins from a single cell is useful when generating multi-component protein complexes or proteins which require additional “helper” proteins such as chaperones. There are two main ways that researchers go about expressing multiple proteins from insect cells: co-infection, which utilizes multiple (often monocistronic) baculoviruses, and co-expression, which utilizes a single polycistronic baculovirus or a single baculovirus with multiple recombinant gene expression cassettes [81]. Previous studies have shown that manipulating the multiplicity of infection (MOI) for each virus, should allow one to control the ratio of each protein expressed [82]. However, formulas that determine how much of each virus should be used only give a theoretical number and often do not account for the cells’ inconsistent uptake of recombinant viruses. It has been shown that as the number of viruses increases, the proportion of cells that are infected with an equal ratio of the viruses decreases [83]. Additionally, a high frequency of recombination occurs when cells are infected with multiple baculovirus [84]. This results in defective virus and failure to express the intended polyprotein product. For these reasons, co-expression is a preferred method to generate multiple proteins when possible.

Inserting the genes for multiple proteins into a single bacmid, co-expression, helps to overcome the problem of uneven distribution of virus taken up by the cells [85]. Expressing multiple recombinant proteins from one baculovirus ensures that each cell infected with the virus will be expressing all the recombinant proteins. A drawback to this approach is an inability to tightly regulate the ratio of each protein expressed. Many co-expression systems utilize the strong and very late baculovirus promoters polyhedrin and p10, such as pFastBac Dual (ThermoFisher) which includes the two promoters in opposing orientations. A similar dual promoter construct has been engineered into a baculovirus to express two post-translational enzymes, farnesyl transferase A and B, in the deleted region of chitinase and cathepsin, leaving the polyhedrin locus attTn7 available for transposition of the gene of interest [86]. While both native promoters generate high yields of recombinant protein, in some instances this results in hindered amounts of the target protein. It has been demonstrated that expressing multiple proteins can overwhelm the insect cells protein production machinery particularly during the very late lytic phase when the host cell functions have declined [87].

Alterations to the host cells can provide additional space for heterologous gene expression. Piggybac vectors were used to add six glycogenes with Tet-inducible promoters to Sf9 cells, creating a strain, SfSWT-5, capable of expressing mammalianized N-glycosylation pathway [88]. Later, nine glycogenes under the control of the 39k virally-induced promoter were included in strain Sf39KSWT to increase expression levels and improve N-glycan processing [89]. With the advancement of site-specific editing by CRISPR-Cas9, strains can be even further refined for specific goals [90].

For larger numbers of recombinant proteins, Berger’s MultiBac system [91] involves cloning individual genes into a series of donor vectors and then recombining them together into an acceptor vector by Cre/loxP with the final assembly being shuttled into the mini attTn7 site at the polyhedrin locus of the bacmid. Further updates to the MultiBac system included a LoxP site integrated into the baculovirus genome to allow for the insertion of fluorescence markers for transfection/infection controls or additional chaperone proteins [92]. Additional inserts can be added to the system by generating polyproteins with include a protease and a series of ORFs, each separated by a protease cleavage site [93]. Cleavage of the individual proteins occurs after the protease self-cleaves from the polyprotein. While this allows for greater expansion of the MultiBac platform, it is not scarless; when using tobacco etch virus cleavage sites, remnants include six amino acids (ENLYFQ) on the C-terminus of each protein and an additional glycine on the N-terminus of all but the first ORF, the protease. Other labs have utilized this platform with a variety of cloning methods and shuttle vectors. USER (Uracil-Specific Excision Reagent) ligation-free cloning method can be used for scarless insertion of pairs of inserts for up to 16 total ORF’s [94]. Macrobac involves BioBricks assembly and ligation independent cloning (LIC) to allow for up to 10 inserts [95]. OmniBac offers the flexibility of bacmid location, utilizing either the Tn7-mediated transposition into the polyhedrin locus, or homologous recombination into the ORF1629 locus [96]. GoldenBac combines the MacroBac and OmniBac capabilities in a single system [97]. The biGBac strategy uses Gibson assembly with optimized linkers to allow for the incorporation of up to 25 inserts [98]. SmartBac has a more versatile set of expression constructs using p10 promoter for very late high expression as well as the late phase p6.9, allowing the user to better control the timing of expression and potentially protein quality [99]. The vector set is also designed in such a way to allow for co-infections in case the large foreign insert is unstable over viral passages. In such polyprotein systems, stoichiometry can be controlled by including multiple copies of a given gene. Alternatively, when lower expression is desired, that gene can be positioned nearer to the end of the transcript or under the control of an alternative promoter. Most recently reported is the PolyBac shuttle vector [100] which has expanded the options available for inserting heterologous genes. Three recombination sites - loxP, attR1/attR2, and the traditional mini attTn7 – are available at distant locations, allowing for either Cre-Lox recombination, Gateway recombination, or Tn7 transposition of multiple transgenes at each location. The investigators took advantage of various promoters to optimize the timing and quality of the individual proteins, achieving the successful addition of the glycosylation pathway via this advanced tool.

To avoid expressing proteases and the associated lingering amino acids, researchers have also used Internal Ribosomal Entry Sites (IRES) to generate multiple recombinant proteins. The Rhopalosiphum padi virus (RhPV) 5’ UTR has been successfully used in bicistronic systems [101,102] and has also been used in combination with Perina nuda virus (PnV) 5’ UTR for a tricistronic vector [103]. Another study found Aphid lethal paralysis virus (ALPV), Black queen cell virus (BQCV), Cricket paralysis virus (CrPV), and Drosophila C virus (DCV) IGR IRES to be active at levels 3 to 4-fold over background in Sf9 and BmN cells in DNA-dual luciferase assays [104]. However, the ORFs downstream of the IRES are expressed at a lower level than the first transcript. If insert size is a concern, 2A self-cleavage sites are much smaller than IRES and can be used to generate two proteins from a single mRNA. The ribosome pauses at the C-terminal glycine of the 2A site and begins again at the proline during translation. There are some residual amino acids when using this strategy, and not all proteins in the population will be cleaved, but the ratios of the two desired proteins are more similar. Four such 2A peptides (P2A, T2A, E2A, and F2A) have been tested with varying levels of efficiency in cultured Drosophila cells and in vivo [105].

Another approach takes advantage of a leaky ribosomal scanning mechanism. In this method the first or second ORF in the polycistron are initiated by non-canonical start sites with the final translation utilizing the standard ATG start codon [106]. While most translation will be initiated at the canonical start, the ribosomal complex will initiate at the previous weak start codons some percentage of the time. This can be useful in cases where the desired ratio of recombinant proteins is to have a high quantity of one and less of the others. Urabe took advantage of non-canonical start codons to alter the expression levels of rAAV capsid proteins. Changing the start codons led to successful AAV replication in Sf9 cells with the three VP proteins being produced at more equivalent levels from a single mRNA transcript [107].

While it may take a few sets of experiments to determine the optimal position for each protein in the given complex for any of these systems, it is now more easily accomplished than in previous versions of baculovirus systems.

Conclusions

While significant advances have been made in baculovirus expression system technologies, there is no consistent predictive algorithm for the optimal expression of different classes of proteins in the system. There are many choices available for driving expression, but very few are readily available in the marketplace. When considering recombinant chaperones or post-translational modification enzymes, it can be beneficial to have such proteins expressed in advance of the gene of interest, allowing very late transcription factors to be fully available for production of the gene of interest. In these circumstances; the use of an earlier or lower promoter for non-target proteins may be beneficial. Alternatively, when expressing proteins comprising a complex, it may be necessary to have the subunits expressed in similar ratios and timeframes. The development of a baculovirus toolkit including easily swapped promoters, enhancers, and chaperones would aid in the empirical testing of complicated proteins and protein complexes. Systematic efforts to produce difficult proteins with a wider variety of promoters could forecast future higher-throughput endeavors. Given the high numbers of ORFs which can now be included in new baculovirus expression vectors, future efforts will likely include selections which take advantage of expression throughout a larger range of the lytic cycle, better control of stoichiometry, and more thoughtful use of the insect cells’ protein production machinery.

Figure 1. Baculovirus Life Cycle in Cultured Insect Cells.

Expression of baculovirus proteins begins at distinct phases post-infection. The most commonly studied promoters have been listed for each phase.

HIGHLIGHTS:

This review includes a description of the most commonly used promoters which are activated during each temporal phase.

There is a brief description of numerous baculovirus enhancers, hybrid promoter, and down-regulating elements as well as inducible promoters and insect promoters.

Available technologies for expressing multiple recombinant proteins are also compared.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This project has been funded in whole or in part with Federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, under contract number HHSN261200800001E.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References:

- [1].Jarvis DL, Baculovirus-insect cell expression systems. Methods Enzymol, 2009. 463: p. 191–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Smith GE, Summers MD, and Fraser MJ, Production of human beta interferon in insect cells infected with a baculovirus expression vector. Mol Cell Biol, 1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [3].Beas-Catena A, et al. , Baculovirus Biopesticides: An Overview. Journal of Animal and Plant Sciences, 2014. 24(2): p. 362–373. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Cox MM, et al. , Safety, efficacy, and immunogenicity of Flublok in the prevention of seasonal influenza in adults. Ther Adv Vaccines, 2015. 3(4): p. 97–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Ishiyama S and Ikeda M, High-level expression and improved folding of proteins by using the vp39 late promoter enhanced with homologous DNA regions. Biotechnology Letters, 2010. 32(11): p. 1637–1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Shrestha A, et al. , Global Analysis of Baculovirus Autographa californica Multiple Nucleopolyhedrovirus Gene Expression in the Midgut of the Lepidopteran Host Trichoplusia ni. J Virol, 2018. 92(23). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Krappa R and Knebelmorsdorf D, Identification of the Very Early Transcribed Baculovirus Gene Pe-38. Journal of Virology, 1991. 65(2): p. 805–812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Hoopes RR Jr. and Rohrmann GF, In vitro transcription of baculovirus immediate early genes: accurate mRNA initiation by nuclear extracts from both insect and human cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 1991. 88(10): p. 4513–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Berretta M, Ferrelli L, Salvador R, Sciocco A, Romanowski V. Baculovirus Gene Expression. Current Issues in Molecular Virology—Viral Genetics and Biotechnological Applications. in Tech; 2013. pp. 57–78

- [10].Chen YR, et al. , Transcriptome Responses of the Host Trichoplusia ni to Infection by the Baculovirus Autographa californica Multiple Nucleopolyhedrovirus. Journal of Virology, 2014. 88(23): p. 13781–13797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Grula MA, Buller PL, and Weaver RF, alpha-Amanitin-Resistant Viral RNA Synthesis in Nuclei Isolated from Nuclear Polyhedrosis Virus-Infected Heliothis zea Larvae and Spodoptera frugiperda Cells. J Virol, 1981. 38(3): p. 916–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Glocker B, et al. , In vitro transcription from baculovirus late gene promoters: accurate mRNA initiation by nuclear extracts prepared from infected Spodoptera frugiperda cells. J Virol, 1993. 67(7): p. 3771–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Rohrmann GF, in Baculovirus Molecular Biology, 4th, Editor. 2019: Bethesda (MD). [Google Scholar]

- [14].Hoopes RR Jr. and Rohrmann GF, In vitro transcription of baculovirus immediate early genes: accurate mRNA initiation by nuclear extracts from both insect and human cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 1991. 88(10): p. 4513–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Pullen SS and Friesen PD, The CAGT motif functions as an initiator element during early transcription of the baculovirus transregulator ie-1. J Virol, 1995. 69(6): p. 3575–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Kogan PH, Chen X, and Blissard GW, Overlapping TATA-dependent and TATA-independent early promoter activities in the baculovirus gp64 envelope fusion protein gene. J Virol, 1995. 69(3): p. 1452–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Jarvis DL, et al. , Use of early baculovirus promoters for continuous expression and efficient processing of foreign gene products in stably transformed lepidopteran cells. Biotechnology (N Y), 1990. 8(10): p. 950–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Jarvis DL, Weinkauf C, and Guarino LA, Immediate-early baculovirus vectors for foreign gene expression in transformed or infected insect cells. Protein Expr Purif, 1996. 8(2): p. 191–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Chisholm GE and Henner DJ, Multiple early transcripts and splicing of the Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus IE-1 gene. J Virol, 1988. 62(9): p. 3193–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Carson DD, Guarino LA, and Summers MD, Functional mapping of an AcNPV immediately early gene which augments expression of the IE-1 trans-activated 39K gene. Virology, 1988. 162(2): p. 444–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Guarino LA and Summers MD, Functional mapping of a trans-activating gene required for expression of a baculovirus delayed-early gene. J Virol, 1986. 57(2): p. 563–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Theilmann DA and Stewart S, Identification and characterization of the IE-1 gene of Orgyia pseudotsugata multicapsid nuclear polyhedrosis virus. Virology, 1991. 180(2): p. 492–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Lin CH and Jarvis DL, Utility of temporally distinct baculovirus promoters for constitutive and baculovirus-inducible transgene expression in transformed insect cells. J Biotechnol, 2013. 165(1): p. 11–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Chen YR, et al. , The transcriptome of the baculovirus Autographa californica multiple nucleopolyhedrovirus in Trichoplusia ni cells. J Virol, 2013. 87(11): p. 6391–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Morris TD and Miller LK, Mutational analysis of a baculovirus major late promoter. Gene, 1994. 140(2): p. 147–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Garrity DB, Chang MJ, and Blissard GW, Late promoter selection in the baculovirus gp64 envelope fusion protein gene. Virology, 1997. 231(2): p. 167–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Mans RM and Knebel-Morsdorf D, In vitro transcription of pe38/polyhedrin hybrid promoters reveals sequences essential for recognition by the baculovirus-induced RNA polymerase and for the strength of very late viral promoters. J Virol, 1998. 72(4): p. 2991–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Fuchs LY, Woods MS, and Weaver RF, Viral Transcription During Autographa californica Nuclear Polyhedrosis Virus Infection: a Novel RNA Polymerase Induced in Infected Spodoptera frugiperda Cells. J Virol, 1983. 48(3): p. 641–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Jin J, Dong W, and Guarino LA, The LEF-4 subunit of baculovirus RNA polymerase has RNA 5’-triphosphatase and ATPase activities. J Virol, 1998. 72(12): p. 10011–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Lu A and Miller LK, The roles of eighteen baculovirus late expression factor genes in transcription and DNA replication. J Virol, 1995. 69(2): p. 975–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Blissard GW and Rohrmann GF, Baculovirus gp64 gene expression: analysis of sequences modulating early transcription and transactivation by IE1. J Virol, 1991. 65(11): p. 5820–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Grabherr R, et al. , Expression of foreign proteins on the surface of Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus. Biotechniques, 1997. 22(4): p. 730–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Zhou J and Blissard GW, Identification of a GP64 subdomain involved in receptor binding by budded virions of the baculovirus Autographica californica multicapsid nucleopolyhedrovirus. J Virol, 2008. 82(9): p. 4449–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Hill-Perkins MS and Possee RD, A baculovirus expression vector derived from the basic protein promoter of Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus. J Gen Virol, 1990. 71 (Pt 4): p. 971–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Bonning BC, et al. , Superior expression of juvenile hormone esterase and beta-galactosidase from the basic protein promoter of Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus compared to the p10 protein and polyhedrin promoters. J Gen Virol, 1994. 75 (Pt 7): p. 1551–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Thiem SM and Miller LK, Differential gene expression mediated by late, very late and hybrid baculovirus promoters. Gene, 1990. 91(1): p. 87–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Weyer U and Possee RD, Functional analysis of the p10 gene 5’ leader sequence of the Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus. Nucleic Acids Res, 1988. 16(9): p. 3635–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Kato T, et al. , Improvement of the transcriptional strength of baculovirus very late polyhedrin promoter by repeating its untranslated leader sequences and coexpression with the primary transactivator. J Biosci Bioeng, 2012. 113(6): p. 694–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Manohar SL, et al. , Enhanced gene expression in insect cells and silkworm larva by modified polyhedrin promoter using repeated Burst sequence and very late transcriptional factor-1. Biotechnol Bioeng, 2010. 107(6): p. 909–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Yang S and Miller LK, Activation of baculovius very late promoters by interaction with very late factor 1. J Virol, 1999. 73(4): p. 3404–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].O’Reilly DR, Miller LK, Luckow VA. Baculovirus expression vectors. A laboratory manual. (Oxford University Press, New York, 1994) [Google Scholar]

- [42].Possee RD and Howard SC, Analysis of the polyhedrin gene promoter of the Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus. Nucleic Acids Res, 1987. 15(24): p. 10233–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Rankin C, Ooi BG, and Miller LK, Eight base pairs encompassing the transcriptional start point are the major determinant for baculovirus polyhedrin gene expression. Gene, 1988. 70(1): p. 39–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Morris TD and Miller LK, Promoter influence on baculovirus-mediated gene expression in permissive and nonpermissive insect cell lines. J Virol, 1992. 66(12): p. 7397–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Vlak JM, et al. , Expression of cauliflower mosaic virus gene I using a baculovirus vector based upon the p10 gene and a novel selection method. Virology, 1990. 179(1): p. 312–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Cha HJ, et al. , Monitoring foreign protein expression under baculovirus p10 and polh promoters in insect larvae. Biotechniques, 2002. 32(5): p. 986, 988, 990 passim. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Furuta T, et al. , Efficient production of an antibody Fab fragment using the baculovirus-insect cell system. J Biosci Bioeng, 2010. 110(5): p. 577–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Song M, et al. , Characterization of N-glycan structures and biofunction of anti-colorectal cancer monoclonal antibody CO17–1A produced in baculovirus-insect cell expression system. J Biosci Bioeng, 2010. 110(2): p. 135–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Roelvink PW, et al. , Dissimilar expression of Autographa californica multiple nucleocapsid nuclear polyhedrosis virus polyhedrin and p10 genes. J Gen Virol, 1992. 73 (Pt 6): p. 1481–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Gomez-Sebastian S, Lopez-Vidal J, and Escribano JM, Significant productivity improvement of the baculovirus expression vector system by engineering a novel expression cassette. PLoS One, 2014. 9(5): p. e96562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Morris TD and Miller LK, Mutational analysis of a baculovirus major late promoter. Gene, 1994. 140(2): p. 147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Lo HR, et al. , Novel baculovirus DNA elements strongly stimulate activities of exogenous and endogenous promoters. J Biol Chem, 2002. 277(7): p. 5256–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Martinez-Solis M, et al. , A novel baculovirus-derived promoter with high activity in the baculovirus expression system. PeerJ, 2016. 4: p. e2183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Sano K, et al. , Enhancement of protein expression in insect cells by a lobster tropomyosin cDNA leader sequence. FEBS Lett, 2002. 532(1–2): p. 143–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Cochran MA and Faulkner P, Location of Homologous DNA Sequences Interspersed at Five Regions in the Baculovirus AcMNPV Genome. J Virol, 1983. 45(3): p. 961–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Guarino LA, Gonzalez MA, and Summers MD, Complete Sequence and Enhancer Function of the Homologous DNA Regions of Autographa californica Nuclear Polyhedrosis Virus. J Virol, 1986. 60(1): p. 224–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Viswanathan P, et al. , The homologous region sequence (hr1) of Autographa californica multinuleocapsid polyhedrosis virus can enhance transcription from non-baculoviral promoters in mammalian cells. J Biol Chem, 2003. 278(52): p. 52564–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Habib S, et al. , Bifunctionality of the AcMNPV homologous region sequence (hr1): enhancer and ori functions have different sequence requirements. DNA Cell Biol, 1996. 15(9): p. 737–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Venkaiah B, et al. , An additional copy of the homologous region (hr1) sequence in the Autographa californica multinucleocapsid polyhedrosis virus genome promotes hyperexpression of foreign genes. Biochemistry, 2004. 43(25): p. 8143–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Chen Y, et al. , A constitutive super-enhancer: homologous region 3 of Bombyx mori nucleopolyhedrovirus. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2004. 318(4): p. 1039–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Rodems SM and Friesen PD, The hr5 transcriptional enhancer stimulates early expression from the Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus genome but is not required for virus replication. J Virol, 1993. 67(10): p. 5776–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Wu YL, et al. , Identification of a high-efficiency baculovirus DNA replication origin that functions in insect and mammalian cells. J Virol, 2014. 88(22): p. 13073–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Chang MJ and Blissard GW, Baculovirus gp64 gene expression: negative regulation by a minicistron. J Virol, 1997. 71(10): p. 7448–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Luckow VA and Summers MD, Signals important for high-level expression of foreign genes in Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus expression vectors. Virology, 1988. 167(1): p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Luckow VA and Summers MD, High level expression of nonfused foreign genes with Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus expression vectors. Virology, 1989. 170(1): p. 31–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Beames B, et al. , Polyhedrin initiator codon altered to AUU yields unexpected fusion protein from a baculovirus vector. Biotechniques, 1991. 11(3): p. 378–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Theilmann DA, et al. , The baculovirus transcriptional transactivator ie0 produces multiple products by internal initiation of translation. Virology, 2001. 290(2): p. 211–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Guarino LA and Smith MW, Nucleotide sequence and characterization of the 39K gene region of Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus. Virology, 1990. 179(1): p. 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Dong ZQ, et al. , Construction and characterization of a synthetic Baculovirus-inducible 39K promoter. J Biol Eng, 2018. 12: p. 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Wu TY, et al. , Expression of highly controllable genes in insect cells using a modified tetracycline-regulated gene expression system. J Biotechnol, 2000. 80(1): p. 75–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Wu YL and Chao YC, The establishment of a controllable expression system in baculovirus: stimulated overexpression of polyhedrin promoter by LEF-2. Biotechnol Prog, 2008. 24(6): p. 1232–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Kust N, et al. , Functional analysis of Drosophila HSP70 promoter with different HSE numbers in human cells. PLoS One, 2014. 9(8): p. e101994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Lanier LM, et al. , Copper treatment increases recombinant baculovirus production and polyhedrin and p10 expression. Biotechniques, 1997. 23(4): p. 728–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Jarvis DL and Summers MD, Glycosylation and secretion of human tissue plasminogen activator in recombinant baculovirus-infected insect cells. Mol Cell Biol, 1989. 9(1): p. 214–2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Sridhar P, et al. , Temporal nature of the promoter and not relative strength determines the expression of an extensively processed protein in a baculovirus system. FEBS Lett, 1993. 315(3): p. 282–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Rankl NB, et al. , The production of an active protein kinase C-delta in insect cells is greatly enhanced by the use of the basic protein promoter. Protein Expr Purif, 1994. 5(4): p. 346–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Lee DF, et al. , A baculovirus superinfection system: efficient vehicle for gene transfer into Drosophila S2 cells. J Virol, 2000. 74(24): p. 11873–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Johnson R, Meidinger RG, and Iatrou K, A cellular promoter-based expression cassette for generating recombinant baculoviruses directing rapid expression of passenger genes in infected insects. Virology, 1992. 190(2): p. 815–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Lopez-Vidal J, et al. , Characterization of a Trichoplusia ni hexamerin-derived promoter in the AcMNPV baculovirus vector. J Biotechnol, 2013. 165(3–4): p. 201–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Bleckmann M, et al. , Genomic Analysis and Isolation of RNA Polymerase II Dependent Promoters from Spodoptera frugiperda. PLoS One, 2015. 10(8): p. e0132898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Sokolenko S, et al. , Co-expression vs. co-infection using baculovirus expression vectors in insect cell culture: Benefits and drawbacks. Biotechnol Adv, 2012. 30(3): p. 766–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Palomares LA, Mena JA, and Ramirez OT, Simultaneous expression of recombinant proteins in the insect cell-baculovirus system: production of virus-like particles. Methods, 2012. 56(3): p. 389–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Belyaev AS, Hails RS, and Roy P, High-level expression of five foreign genes by a single recombinant baculovirus. Gene, 1995. 156(2): p. 229–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Kamita SG, Maeda S, and Hammock BD, High-frequency homologous recombination between baculoviruses involves DNA replication. J Virol, 2003. 77(24): p. 13053–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Kerrigan JJ, et al. , Production of protein complexes via co-expression. Protein Expr Purif, 2011. 75(1): p. 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Gillette WK, et al. , Farnesylated and methylated KRAS4b: high yield production of protein suitable for biophysical studies of prenylated protein-lipid interactions. Sci Rep, 2015. 5: p. 15916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Tate CG, Whiteley E, and Betenbaugh MJ, Molecular chaperones stimulate the functional expression of the cocaine-sensitive serotonin transporter. J Biol Chem, 1999. 274(25): p. 17551–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Aumiller JJ, et al. , A new glycoengineered insect cell line with an inducibly mammalianized protein N-glycosylation pathway. Glycobiology, 2012. 22(3): p. 417–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Toth AM, et al. , A new insect cell glycoengineering approach provides baculovirus-inducible glycogene expression and increases human-type glycosylation efficiency. J Biotechnol, 2014. 182–183: p. 19–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Mabashi-Asazuma H and Jarvis DL, CRISPR-Cas9 vectors for genome editing and host engineering in the baculovirus-insect cell system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2017. 114(34): p. 9068–9073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Berger I, Fitzgerald DJ, and Richmond TJ, Baculovirus expression system for heterologous multiprotein complexes. Nat Biotechnol, 2004. 22(12): p. 1583–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Trowitzsch S, et al. , MultiBac complexomics. Expert Rev Proteomics, 2012. 9(4): p. 363–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Nie Y, et al. , Multiprotein complex production in insect cells by using polyproteins. Methods Mol Biol, 2014. 1091: p. 131–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Zhang Z, Yang J, and Barford D, Recombinant expression and reconstitution of multiprotein complexes by the USER cloning method in the insect cell-baculovirus expression system. Methods, 2016. 95: p. 13–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Gradia SD, et al. , MacroBac: New Technologies for Robust and Efficient Large-Scale Production of Recombinant Multiprotein Complexes. Methods Enzymol, 2017. 592: p. 1–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Vijayachandran LS, et al. , Gene gymnastics: Synthetic biology for baculovirus expression vector system engineering. Bioengineered, 2013. 4(5): p. 279–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Neuhold J, et al. , GoldenBac: a simple, highly efficient, and widely applicable system for construction of multi-gene expression vectors for use with the baculovirus expression vector system. BMC Biotechnol, 2020. 20(1): p. 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Weissmann F, et al. , biGBac enables rapid gene assembly for the expression of large multisubunit protein complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2016. 113(19): p. E2564–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Zhai Y, et al. , SmartBac, a new baculovirus system for large protein complex production. J Struct Biol X, 2019. 1: p. 100003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Maghodia AB, Geisler C, and Jarvis DL, A New Bacmid for Customized Protein Glycosylation Pathway Engineering in the Baculovirus-Insect Cell System. ACS Chem Biol, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [101].Chen YJ, Chen WS, and Wu TY, Development of a bi-cistronic baculovirus expression vector by the Rhopalosiphum padi virus 5’ internal ribosome entry site. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2005. 335(2): p. 616–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Pijlman GP, et al. , Stabilized baculovirus vector expressing a heterologous gene and GP64 from a single bicistronic transcript. J Biotechnol, 2006. 123(1): p. 13–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].W.S., et al. , Development of a prokaryotic-like polycistronic baculovirus expression vector by the linkage of two internal ribosome entry sites. J Virol Methods, 2009. 159(2): p. 152–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Carter JR, Fraser TS, Fraser MJ. Examining the relative activity of several dicistrovirus intergenic internal ribosome entry site elements in uninfected insect and mammalian cell lines. J Gen Virol. 2008. December;89(Pt 12):3150–3155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Daniels RW, et al. , Expression of multiple transgenes from a single construct using viral 2A peptides in Drosophila. PLoS One, 2014. 9(6): p. e100637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].Bosma B, et al. , Optimization of viral protein ratios for production of rAAV serotype 5 in the baculovirus system. Gene Ther, 2018. 25(6): p. 415–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [107].Urabe M, Ding C, and Kotin RM, Insect cells as a factory to produce adeno-associated virus type 2 vectors. Hum Gene Ther, 2002. 13(16): p. 1935–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]