Summary

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is caused by a mutation in the β-globin gene HBB1. We used a custom adenine base editor (ABE8e-NRCH)2,3 to convert the SCD allele (HBBS) to Makassar β-globin (HBBG), a non-pathogenic variant4,5. Ex vivo delivery of mRNA encoding base editor with a targeting guide RNA into hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) from SCD patients resulted in 80% HBBS-to-HBBG conversion. Sixteen weeks after transplantation of edited human HSPCs into immunodeficient mice, HBBG frequency was 68% and bone marrow reticulocytes demonstrated a 5-fold decrease in hypoxia-induced sickling, indicating durable editing. To assess the physiological effects of HBBS base editing, we delivered ABE8e-NRCH and guide RNA into HSPCs from a humanized SCD mouse6, followed by transplantation into irradiated mice. After sixteen weeks, Makassar β-globin represented 79% of β-globin protein in blood and hypoxia-induced sickling was reduced 3-fold. Mice receiving base-edited HSPCs showed rescue of hematologic parameters to near-normal levels and reduced splenic pathology compared to unedited controls. Secondary transplantation of edited bone marrow confirmed durable editing of long-term hematopoietic stem cells and revealed that ≥20% HBBS-to-HBBG editing is sufficient for phenotypic rescue. Base editing of human HSPCs avoided p53 activation and larger deletions observed following Cas9 nuclease treatment. These findings suggest a one-time autologous treatment for SCD that eliminates pathogenic HBBS, generates benign HBBG, and minimizes undesired consequences of double-strand DNA breaks.

Sickle-cell disease is an autosomal recessive disorder caused by mutation of HBB, which normally encodes adult β-globin (βA) (Fig. 1a). At low oxygen concentrations, the mutant β-globin (βS) causes hemoglobin polymerization within red blood cells (RBCs), resulting in characteristic sickle-shaped RBCs and a cascade of hemolysis, inflammation, and microvascular occlusions. Symptoms include anemia, severe acute and chronic pain, immunodeficiency, multi-organ failure and early death1. While allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) transplantation can cure SCD, optimally matched donors are usually not available and the procedure can result in graft rejection or graft-versus-host disease (Supplementary References).

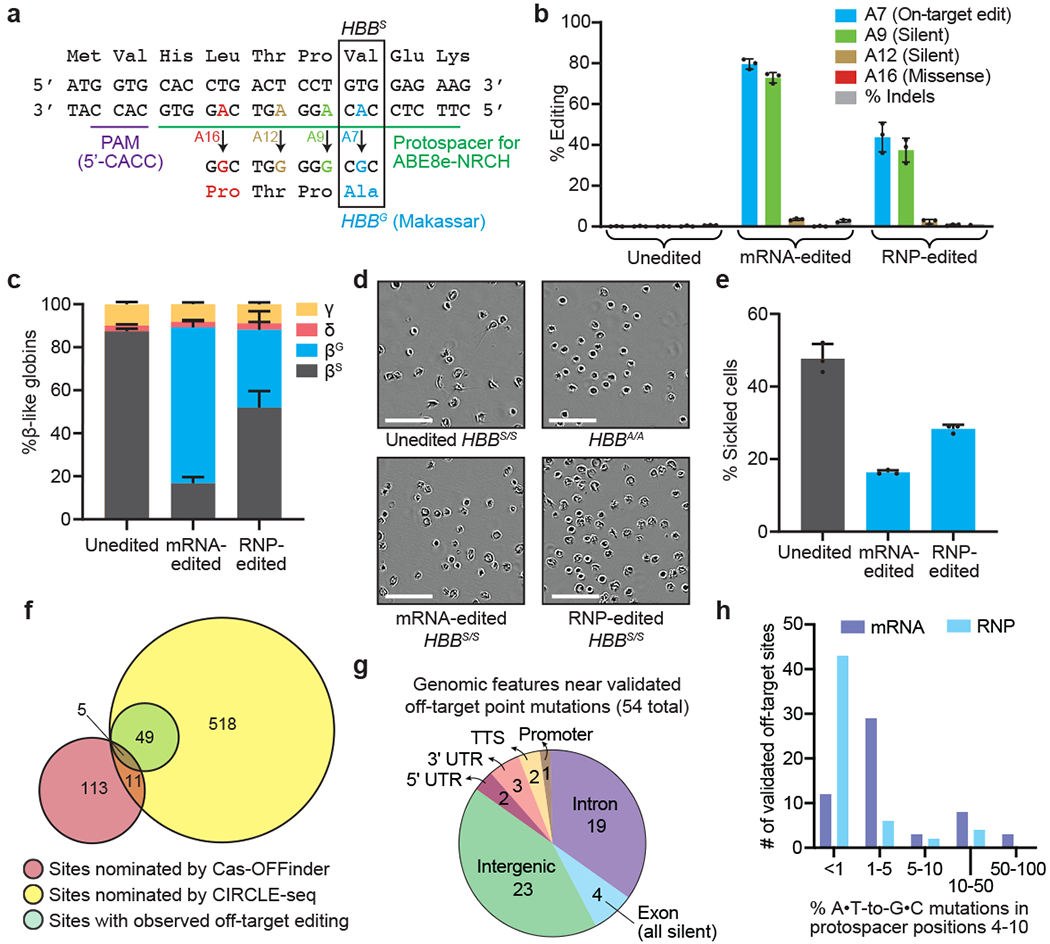

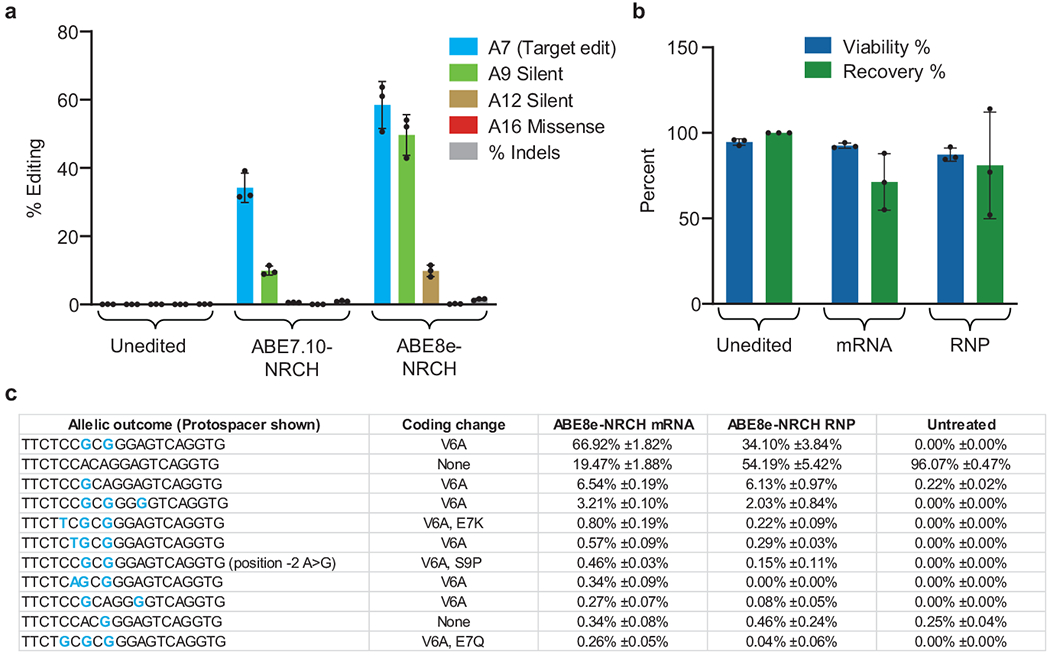

Figure 1. Adenine base editing converts sickle cell disease β-globin (HBBS) to benign Makassar β-globin (HBBG) in patient CD34+ HSPCs.

CD34+ cells from three SCD patient donors were electroporated with ABE8e-NRCH mRNA or RNP using an sgRNA targeting the SCD mutant HBB codon. (a) The edited region of HBB with the target A at protospacer position 7 shown in blue along with potential bystander edits in green (silent), brown (silent), and red (non-silent). (b) Editing efficiencies by HTS at target and bystander adenines, and indels after 6 days in stem-cell culture media following electroporation. (c) Proportion of β-like globin proteins by HPLC of reticulocyte lysates after 18 days in differentiation media following electroporation. (d) Representative phase-contrast images of reticulocytes derived from unedited or edited donor HSPCs incubated 8 hours in 2% O2. Nine images of >50 cells each were collected per sample. Scale bar=50 μm. (e) Quantification of sickled reticulocytes from counting >300 randomly selected cells by a blinded observer from images as in (d). (f) Venn diagram showing candidate off-target sites nominated by Cas-OFFinder and CIRCLE-seq, and nominated sites for which off-target editing was observed by targeted DNA sequencing in SCD patient CD34+ cells electroporated with ABE8e-NRCH mRNA. (g) Predicted genomic features of validated off-target sites. TTS, ≤1 kb from the transcription termination site; UTR, untranslated region. (h) ABE8e-NRCH-treated HSPCs from two different SCD patient donors were sequenced at 697 potential off-target sites. The histogram shows the number of validated off-target base editing sites binned by average percentage of sequencing reads for each site with any A•T-to-G•C mutations in protospacer nucleotides 4-10. Bar values in (b), (c), and (e) and error bars reflect mean±SD of three independent biological replicates, with individual values shown as dots.

Ex vivo modification of autologous HSCs to circumvent the deleterious effects of the SCD mutation underlies several experimental therapies7–9 (Supplementary References). Approaches showing early clinical promise include ectopic expression of an anti-sickling β-like globin gene by lentiviral vectors10 or induction of fetal hemoglobin (HbF) by suppression11 or Cas9-mediated disruption12 of BCL11A. Lentiviral vectors carry risks of insertional mutagenesis, however, and may not effectively suppress the expression of pathological βS. Genetic manipulation to induce HbF expression does not eliminate βS, and when mediated by double-stranded DNA breaks (DSBs), carries risks associated with uncontrolled mixtures of indels, translocations, loss of large chromosomal segments, chromothripsis, and p53 activation13–18 (Supplementary References). Cas9 nuclease-mediated homology-directed repair (HDR) can correct HBBS but is difficult to achieve efficiently in repopulating HSCs19,20 and also requires DSBs. Eliminating the root cause of SCD by converting the HBBS allele to a benign variant without introducing DSBs could overcome these limitations.

Adenine base editors (ABEs) convert targeted A•T base pairs to G•C in living cells without requiring DSBs or donor DNA templates, and with minimal indel formation2. In SCD, the GAG (Glu) codon encoding amino acid 6 of β-globin is mutated to GTG (Val). While adenine base editing cannot revert this mutation, it can convert the pathogenic codon to GCG (Ala), resulting in a naturally occurring, non-pathogenic variant termed Hb-Makassar (HBBG)3–5,21,22 (Fig. 1a).

We generated a novel ABE (ABE8e-NRCH) that converts the SCD allele to the non-pathogenic HBBG Makassar allele with minimal non-silent bystander edits in patient CD34+ HSPCs. Edited HSPCs were durable after engraftment in mice, with an HBBG frequency of 68% 16 weeks after transplantation and markedly reduced sickling in derived erythroid cells. To assess phenotypic rescue, we edited HSPCs from a mouse SCD model6 in which endogenous β-globin genes were replaced by human HBBS and transplanted these edited HSPCs into irradiated adult recipient mice. Primary and secondary transplantation of edited mouse HSPCs confirmed editing in long-term HSCs and restored hematologic parameters to near-normal levels. These findings highlight autologous ex vivo base editing and transplantation of HSCs as a potential one-time treatment for SCD.

Results

HBBS base editing in HSPCs

The HBBS mutation can be targeted by base editing using a phage-assisted continuous evolution (PACE)-generated Cas9-NRCH3 that recognizes a CACC protospacer-adjacent motif (PAM) (Fig. 1a). Separately, we used PACE to evolve TadA-8e, a deoxyadenosine deaminase that supports high base editing efficiencies2. We combined TadA-8e with Cas9-NRCH nickase to generate ABE8e-NRCH. Co-delivery of ABE8e-NRCH and the HBBS-targeting single guide RNA (sgRNA) to homozygous HBBS HEK293T cells by plasmid lipofection achieved 58% HBBS-to-HBBG conversion (Extended Data Fig. 1a).

Next, we used ABE8e-NRCH to edit human HSPCs ex vivo via electroporation of either the ABE8e-NRCH+sgRNA ribonucleoprotein (RNP) or ABE8e-NRCH mRNA with sgRNA. ABE8e-NRCH RNP electroporated into plerixafor-mobilized peripheral blood CD34+ HSPCs cells from three SCD patient donors resulted in 44±5.9% HBBS-to-HBBG editing, 1,2±0.33% indels, and <0.5% other missense alleles after 6 days. Electroporating ABE8e-NRCH mRNA and sgRNA into the same cells resulted in 80±2.1% HBBS-to-HBBG conversion, 2.8±0.50% indels, and <2% other missense bystander alleles (Fig. 1b, Extended Data Fig. 1b–c). Thus, introduction of ABE8e-NRCH RNP or mRNA using a clinically relevant delivery method can convert HBBS to HBBG in HSPCs efficiently and with few byproducts.

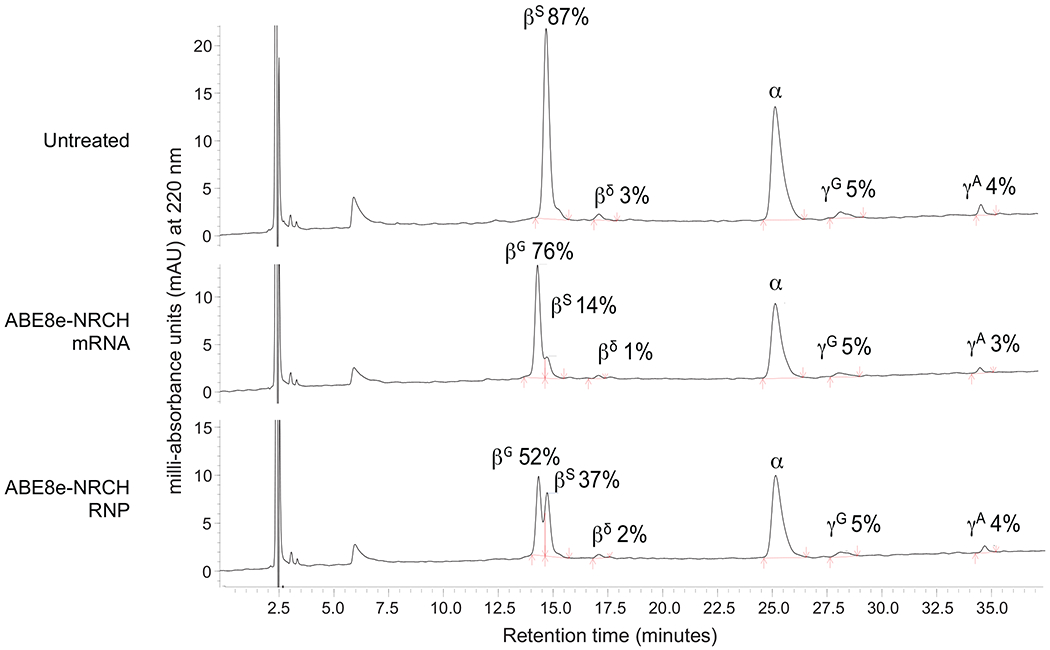

SCD patient HSPCs edited with ABE8e-NRCH mRNA or RNP were differentiated ex vivo into late-stage erythroid precursors (Extended Data Fig. 2, Supplementary Table 1). Quantification of β-like globin proteins by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) showed that unedited SCD patient cells contained 87±1.3% βS and no detectable βG (Extended Data Fig. 3), while base-edited cells contained 72±3.0% βG and 17±3.0% βS, a 5.1-fold decrease of the pathogenic βS protein (Fig. 1c). These findings show that ABE8e-NRCH-mediated editing of HBBS results in substantial production of βG and concomitant loss of βS protein.

To assess the effects of editing on sickling, purified reticulocytes from ex vivo differentiation of unedited or ABE8e-NRCH-edited SCD patient CD34+ cells were incubated in 2% O2. Editing reduced sickling frequency from 47.7% to 16.3%, (Fig. 1d–e), confirming that HBBS-to-HBBG conversion reduces sickling. Reticulocytes differentiated from cells treated with ABE8e-NRCH RNP showed similar results but with lower efficiencies (Fig. 1c–e).

To determine whether base editing alters erythropoiesis, we used flow cytometry to track the expression of cell-surface maturation markers CD49d, CD235a, and Band3 and used a Hoechst stain to track enucleation. No differences in the expression of these markers were observed between edited and unedited cells (Extended Data Fig. 2), suggesting that editing with ABE8e-NRCH does not alter erythropoiesis.

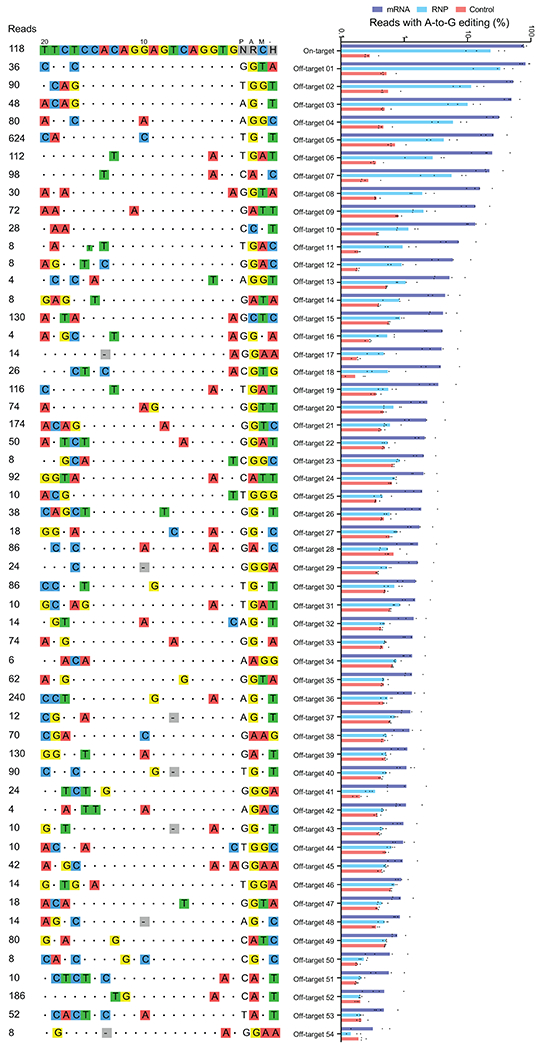

Genome-wide off-target analyses

We used both computational and experimental methods to extensively characterize off-target editing from ABE8e-NRCH and sgRNA treatment (Fig. 1f and Supplementary Discussion). The Cas-OFFinder algorithm23 identified 140 NRCH PAM-containing human genomic sites containing three or fewer mismatches to the target protospacer. We also performed CIRCLE-seq24, a highly sensitive experimental off-target identification method, to detect where Cas9-NRCH, complexed with the HBBS-targeting sgRNA, cleaves purified human genomic DNA in vitro. CIRCLE-seq identified 601 candidate off-target sites (Supplementary Table 2). The 140 sites nominated by Cas-OFFinder and the 601 sites nominated by CIRCLE-seq shared only 16 sites in common.

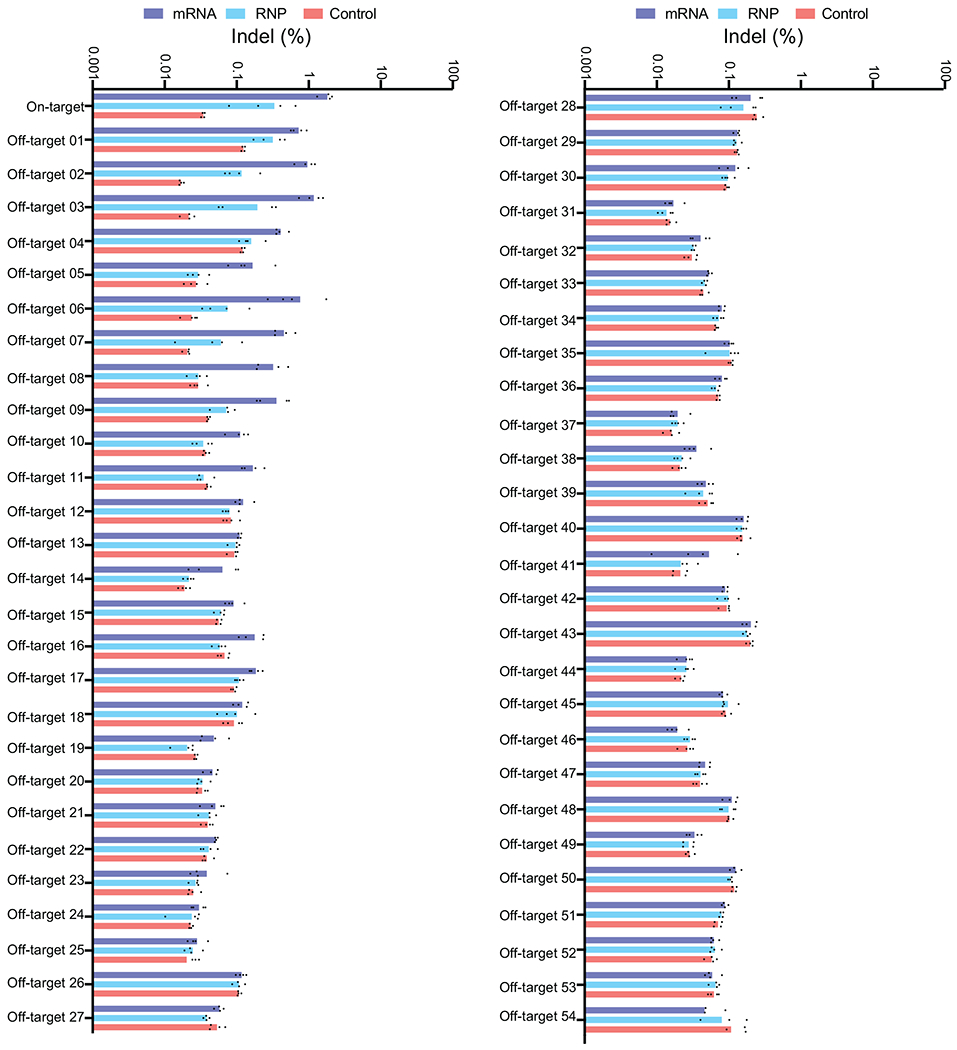

Of the 725 candidate off-target sites, 697 were amenable to multiplex targeted DNA sequencing in SCD patient CD34+ HSPCs treated with ABE8e-NRCH (Supplementary Discussion). We detected point mutations consistent with adenine base editing at 7.8% (54/697) of the sequenced sites. All 54 verified sites were candidates identified by CIRCLE-seq; five were also identified by Cas-OFFinder (Fig. 1f, Extended Data Figs. 4–5, Supplementary Table 2), highlighting the importance of experimental identification of off-target sites. Off-target activity fell predominantly in intergenic and intronic regions. One off-target site was in the promoter region of CCDC85B and four were in exons (Fig. 1g), all of which led to silent mutations (Supplementary Table 2). Off-target sites in UTRs were all >500 bp from any coding region.

As anticipated, off-target editing from RNP was lower than that of mRNA, likely due to shorter duration of exposure or lower editing activity2 (Fig. 1h, Extended Data Figs. 4–5). Indel frequencies were <2% at all off-target sites (Extended Data Fig. 5). Collectively, these findings from extensive genome-wide off-target analyses of ABE8e-NRCH base-edited SCD patient HSPCs did not reveal off-target mutations of anticipated clinical relevance.

Transplantation of human HSPCs into mice

We next examined whether delivery of ABE8e-NRCH into SCD patient CD34+ cells can convert HBBS to HBBG in HSCs that repopulate bone marrow in an animal. CD34+ HSPCs from three SCD patients were edited by electroporation of ABE8e-NRCH and sgRNA in RNA or RNP forms. After 24 hours, the resulting six sets of edited HSPCs and a set of unedited control cells from each donor were each transplanted via tail-vein injection into 3-5 immunodeficient NOD B6.SCID II2rγ−/−KitW41/W41 (NBSGW) mice25. Sixteen weeks after infusion, when persisting human cells are thought to be generated from bone marrow-repopulating HSCs capable of sustaining a hematopoietic system25, we extracted bone marrow for analysis (Fig. 2a).

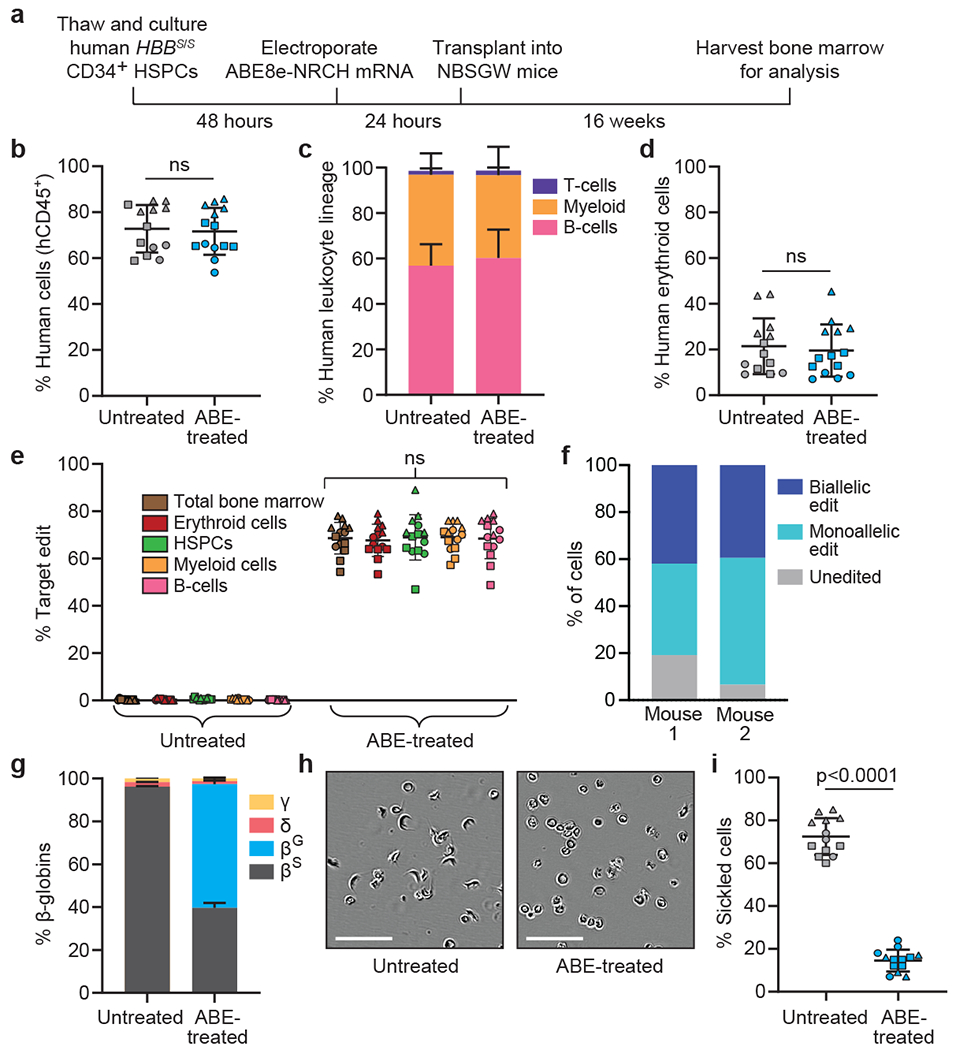

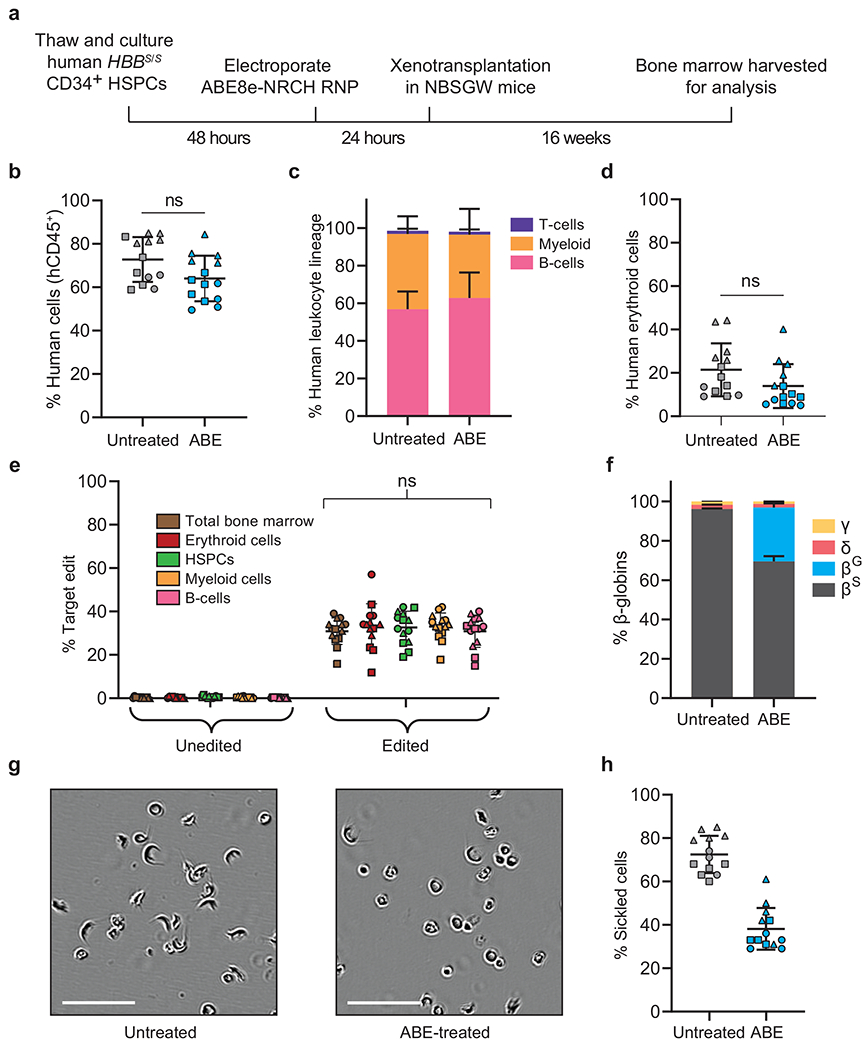

Figure 2. Engraftment of ABE8e-NRCH mRNA-treated SCD patient CD34+ HSPCs after transplantation into immunodeficient mice.

CD34+ HSPCs from three HBBS/S SCD patient donors were electroporated with ABE8e-NRCH mRNA and sgRNA targeting the SCD mutant HBB codon. 2-5x105 treated cells were transplanted into NBSGW mice via tail-vein injection. Mice were analyzed 16 weeks after transplantation. (a) Experimental workflow. (b) Engraftment measured by percentage of human CD45+ (hCD45+) cells in recipient mouse bone marrow. (c) Human B-cells (hCD19+), myeloid cells (hCD33+), and T-cells (hCD3+) cells in recipient mouse bone marrow shown as percentages of the hCD45+ population. (d) Human erythroid precursors (hCD235a+) in recipient mouse bone marrow shown as percentage of human and mouse CD45− cells, (e) HBBS-to-HBBG editing efficiencies in human donor CD34+ cell-derived lineages from recipient bone marrow. Erythroid, myeloid, B-cell, and HSPC human lineages were collected using antibodies that recognize hCD235a, hCD33, hCD19, and hCD34, respectively, (f) Clonal editing outcomes determined by single-cell 5’ RNA-seq in CD235a+ cells from the bone marrow of two edited mice. (g) Proportions of β-like globin proteins by HPLC of human donor-derived reticulocytes isolated from recipient mouse bone marrow. (h) Representative phase-contrast images of human reticulocytes from bone marrow incubated 8 hours in 2% O2. Nine images of >50 cells each were collected per sample. Scale bar=50 μm. (i) Quantification of sickled cells as in Fig. 1e. n=14 mice receiving edited cells and n=13 mice receiving unedited cells in b-e, g, and i. Triangle, square, and circle symbols represent HSPCs from three different SCD donors. Plotted values and error bars reflect mean±SD. Statistical significance was assessed by one-way ANOVA in i and by two-tailed Student’s t-test elsewhere; “ns”, not significant.

The disruption of targeted genes through DSBs or deletion can alter engraftment and maintenance of certain lineages (Supplementary References). To determine how base editing HBBS affects differentiation potential and lineage survival, we assessed the human hematopoietic lineages present in recipient mouse bone marrow after transplantation. Flow cytometry using an anti-human CD45 antibody revealed ~70% human cells in bone marrow from all animals (Fig. 2b). Flow cytometry to quantify the relative abundances of human B-cells (CD19+), myeloid cells (CD33+), T-cells (CD3+), and erythroid cells (CD235a+) revealed equivalent proportions of each lineage in mice receiving unedited or edited cells (Fig. 2c, 2d, Supplementary Fig. 1), indicating that the engraftment and differentiation potential of CD34+ cells was not altered by base editing.

To examine the possibility of skewed hematopoiesis from base editing, we used human lineage-specific antibodies to purify donor-derived mononuclear cells (“total bone marrow”; CD45+), B-cells (CD19+), myeloid cells (CD33+), HSPCs (CD34+) and erythroblasts (CD235a+) from mouse bone marrow (Supplementary Fig.1). HTS of the targeted genomic region revealed that all isolated populations contained the HBBS-to-HBBG edit at similar frequencies (68±6.6%–69±5.7%, Fig. 2e), suggesting that this allele proportion was maintained in HSCs and in their differentiated progeny. Collectively, these results indicate that ABE8e-NRCH-mediated conversion of HBBS to HBBG in repopulating HSCs does not impede their engraftment or multipotency.

Human CD235a+ erythroblasts and reticulocytes isolated from the bone marrow of two mice transplanted with ABE-treated or untreated SCD patient cells were purified by magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS) (Extended Data Fig. 6) and subjected to single-cell RNA-seq to determine clonal editing outcomes. An average of 46.5% of cells were edited in only one HBBS allele, 40.6% were edited in both alleles, and 12.9% of cells were unedited (Fig. 2f). Base editing decreased the fraction of βS from 96±0.28% of total β-like globin protein to 40±2.3% in CD235a+ cells. βG was undetectable in unedited cells but accounted for 58±2.8% of β-like globin after base editing (Fig. 2g). Human erythroid cells derived from edited HSPCs showed a 5-fold reduction in sickling compared to unedited control cells (Fig. 2h–i). Editing using RNP resulted in similar effects but was less efficient (Extended Data Fig. 7). Collectively, these data indicate that base-edited SCD donor-derived HSCs can repopulate the hematopoietic system and generate erythroid cells with greatly reduced propensity for hypoxic sickling.

Transplantation of mouse HSPCs into mice

Studying the physiological rescue of SCD phenotypes by transplantation of human cells into mice is difficult due to the short lifetime of circulating human RBCs in mice25. To evaluate physiological phenotypes, we edited Lin− HSPCs from the Townes SCD mouse model in which endogenous adult α- and β-like globin genes are replaced by human globin genes, resulting in SCD phenotypes6. Mice harboring one normal and one SCD HBB allele (HBBA/S) model heterozygous “sickle-cell trait,” which is largely asymptomatic in this mouse model (Supplementary Table 3) and in humans.

We electroporated ABE8e-NRCH RNP into HBBS/S HSPCs from Townes mice followed by transplantation into irradiated adult recipient mice 24 hours later. Unedited HBBS/S and HBBA/S HSPCs were used as disease and healthy controls, respectively. Since donor mice cells express CD45.2, while recipient cells express CD45.1, they are distinguishable by allele-specific antibodies (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Table 1)6. We collected blood at 6, 10, 14, and 16 weeks post-transplantation to track engraftment and β-globin content.

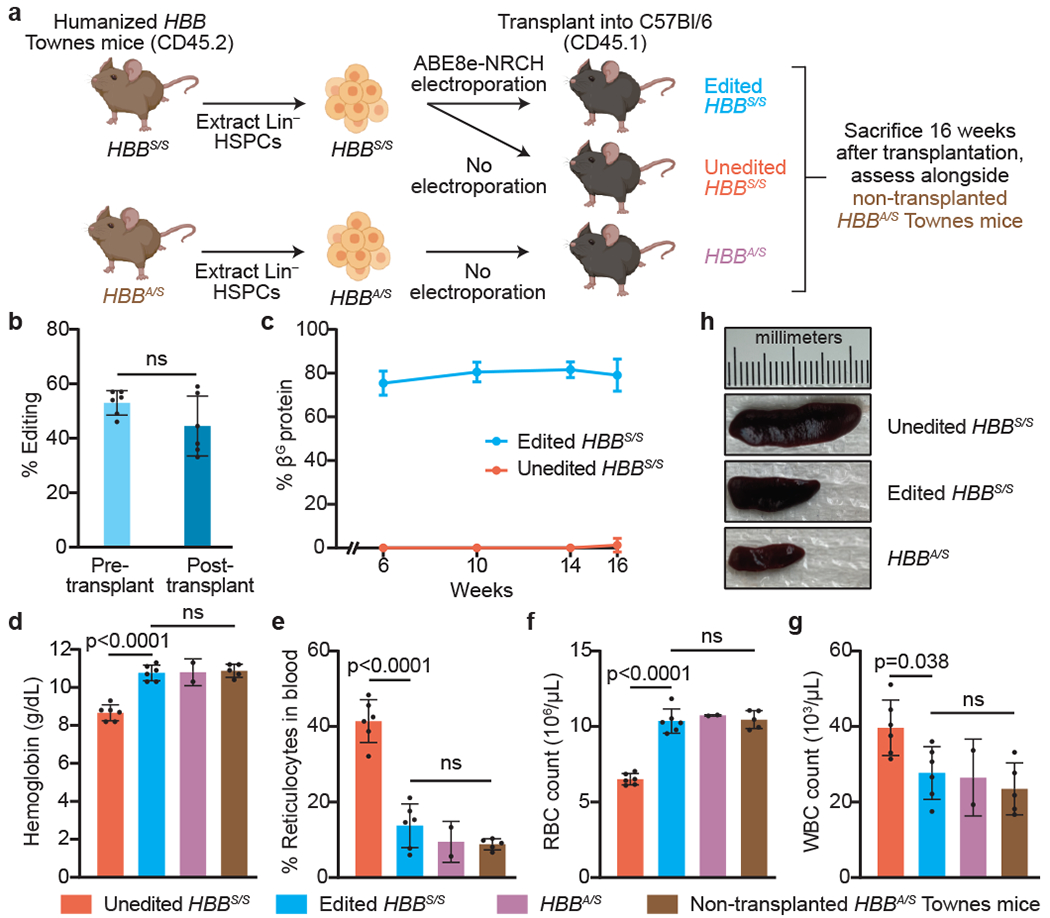

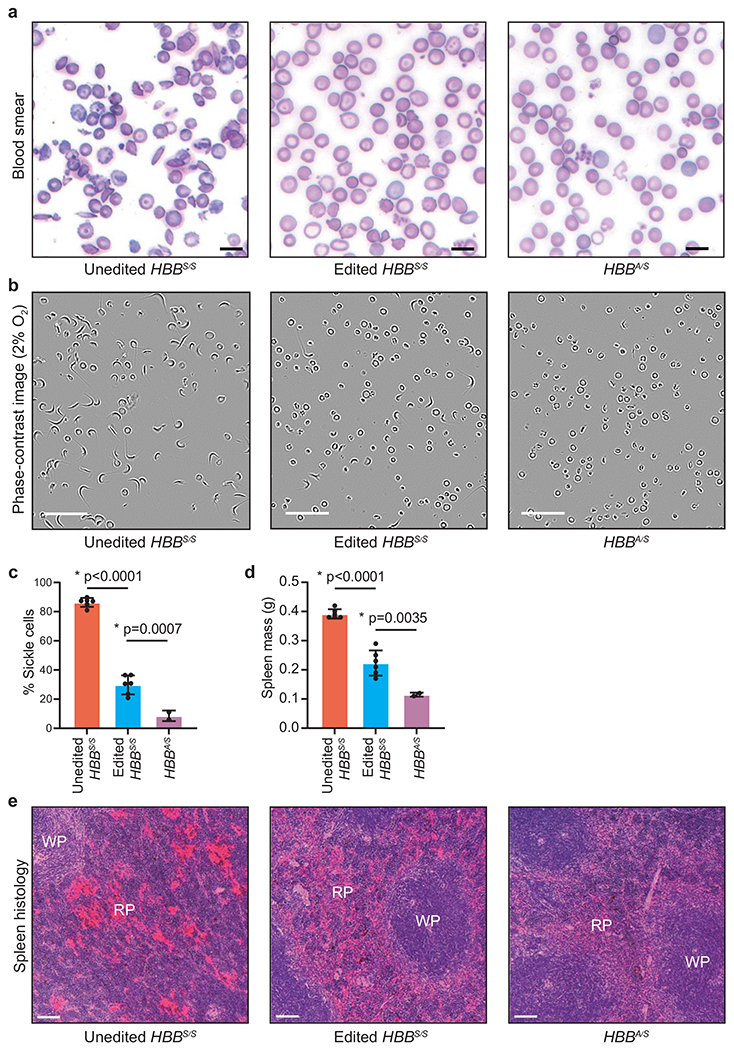

Figure 3. HBBS-to-HBBG base editing alleviates pathology in a mouse model of SCD.

(a) Lineage negative (Lin−) HSPCs from the bone marrow of Townes SCD mice (CD45.2, human HBBS/S) were electroporated with ABE8e-NRCH and sgRNA RNP or not electroporated, then transplanted into irradiated CD45.1 C57BI/6 recipient mice. Unedited HBBA/S HSPCs from Townes sickle-cell trait mice transplanted into irradiated CD45.1 C57BI/6 mice, and non-transplanted HBBA/S Townes mice were used as healthy controls. (b) HBBS-to-HBBG editing efficiency in cells cultured 3 days after electroporation (pre-transplant) or in PBMCs collected 16 weeks post-transplant. ns, not significant by two-tailed Student’s t-test. (c) Percentage of βG among β-like globin proteins by RP-HPLC analysis of blood. (d-g) Hematologic indices 16 weeks post-transplant. Statistical significance was assessed using one-way ANOVA, with Šidák’s multiple comparisons test to calculate p-values. Differences among edited HBBS/S, transplanted HBBA/S, and non-transplanted HBBA/S mice were not significant. Bar values and error bars reflect mean±SD of n=6 mice (unedited HBBS/S, edited HBBS/S), n=2 mice (HBBA/S), or n=5 mice (non-transplanted HBBA/S). (h) Spleens were imaged from each mouse 16 weeks after transplantation with Townes mouse HSPCs. Representative images are shown.

CD45.2 expression revealed that donor engraftment was >90% in all mice 10 weeks post-transplantation (Extended Data Fig. 8a). Engraftment of edited and control donor HSPCs progressed similarly, suggesting that editing did not alter transplanted HSC fitness. Pre-transplantation HBBS-to-HBBG editing efficiency measured 3 days after electroporation was 53±4.5% (Fig. 3b). Editing levels in genomic DNA from whole blood in animals 16 weeks post-transplantation showed 44±11% HBBG allele frequency. As we observed with human HSPCs (Fig. 2e), the modest decrease in HBBG allele frequency after 16 weeks of engraftment could arise if repopulating HSCs are less amenable to electroporation or base editing than other cell types within the HSPC population. A clonal analysis of colonies from bone marrow cells after mouse sacrifice revealed that 40±15% of cells were edited in both HBBS alleles, and 36±12% in only one allele, while 24±3.2% of cells were unedited (Extended Data Fig. 8b).

To measure the effect of base editing on hemoglobin composition in circulating RBCs, we analyzed peripheral blood cell lysates from each time point. On average, βG made up 75-82% of total β-like globin protein in mice receiving edited HBBS/S HSPCs, with little fluctuation throughout the experiment (Fig. 3c). The enrichment of βG over the observed editing efficiency (79% vs. 44% at 16 weeks) likely reflects the increased lifetime of βG-containing RBCs. We also found no difference in oxygen binding in blood from mice receiving unedited HBBS/S cells, HBBA/S cells, or edited HBBS/S cells 14 weeks after transplantation, suggesting that βG-containing hemoglobin binds oxygen normally (Extended Data Fig. 8c).

Rescue of SCD in transplanted mice

Complete blood counts were performed on mice transplanted with edited (n=6) or unedited (n=6) mouse HBBS/S HSPCs, as well as mice transplanted with unedited HBBA/S cells (n=2) and non-transplanted mice with an HBBA/S genotype (n=5) serving as two types of healthy controls (Fig. 3d–g, Supplementary Table 3). Compared to healthy controls, mice that received unedited mouse HBBS/S HSPCs showed disruptions in total hemoglobin concentration and cell counts of reticulocytes, RBCs, and white blood cells (WBC) (Fig. 3d–g), abnormalities consistent with hemolytic anemia and inflammation in SCD patients6. Importantly, transplantation of base-edited HBBS/S HSPCs rescued the hematological defects of SCD, restoring all tested blood parameters to levels similar to those of healthy controls (Fig. 3d–g).

To assess the consequence of base editing on circulating RBC morphology, we analyzed blood from mice 16 weeks after transplantation (Extended Data Fig. 9a). Expected morphological abnormalities were observed among RBCs of mice that received unedited HBBS/S cells, including abundant oblong sickle forms, polychromasia reflecting reticulocytosis, and fragmentation. RBCs of mice transplanted with HBBS-to-HBBG edited HSPCs showed a reduction in all pathologic morphologies and were more similar to RBCs of healthy HBBA/S controls. Separately, blood was incubated in 2% O2 to induce sickling (Extended Data Fig. 9b–c). RBCs from mice transplanted with unedited HBBS/S HSPCs showed 86.3±3.0% sickling, compared to 29.8±6.5% sickling in RBCs from mice transplanted with base-edited HBBS/S HSPCs, a 2.9-fold decrease. These data establish that transplantation of edited HBBS/S HSPCs leads to durable production of RBCs that are resistant to sickling both in vivo and in vitro after exposure to hypoxia.

Enlarged spleen is a hallmark symptom of young SCD patients and mouse models6. The average spleen mass of mice receiving edited HBBS/Scells was 0.22±0.043 g, compared to 0.39±0.016 g in mice receiving unedited HBBS/S cells and 0.11±0.007 g in mice receiving HBBA/S cells (Extended Data Fig. 9d). Average spleen mass was thus restored by 61% towards that of healthy controls in animals receiving base edited HSPCs (Fig. 3h). RBC pooling and extramedullary erythropoiesis in the spleen were also largely corrected in mice receiving edited HBBS/S cells (Extended Data Fig. 9e). Taken together, the persistence of ABE8e-NRCH-mediated HBBS-to-HBBG editing in bone marrow-repopulating HSCs and the partial or complete rescue of every examined SCD phenotype suggest that ex vivo base editing of HBBS in HSPCs followed by transplantation can alleviate SCD.

Secondary transplant dose-dependent rescue

We performed secondary transplantations to confirm editing of long-term repopulating HSCs and determine the level of HBBS-to-HBBG base editing required to rescue SCD hematological abnormalities. Following primary transplantation of mouse HSPCs described above, bone marrow extracted from one recipient mouse had an HBBG allele frequency of 39%. This bone marrow was mixed at ratios of 0:100, 20:80, 40:60, 60:40, 80:20, and 100:0 with bone marrow from a mouse that had been transplanted 16 weeks earlier with unedited HBBS/S Lin− HSPCs. Each mixture was transplanted separately into three irradiated C57/BI6 mice (Fig. 4a). Sixteen weeks after secondary transplantation, peripheral blood was collected to assess engraftment (Fig. 4b), HBBG allele frequency and hematologic phenotypes.

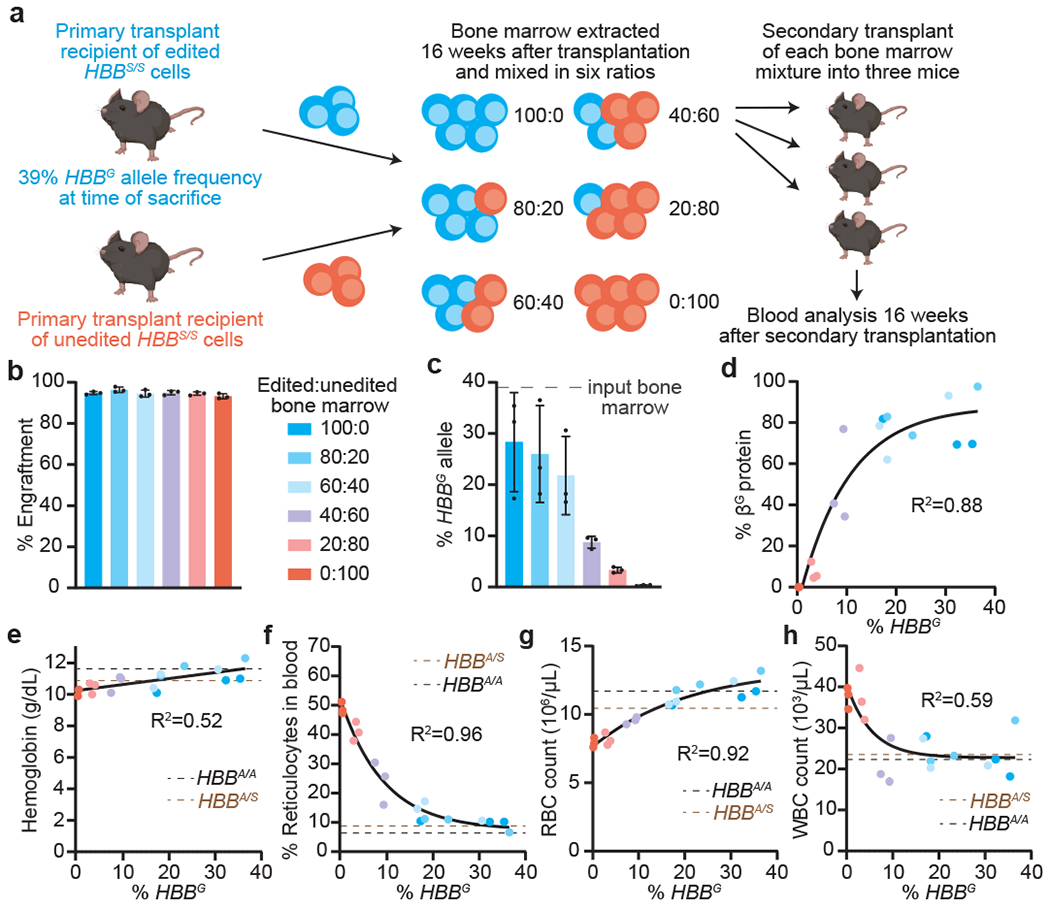

Figure 4. Secondary transplantation reveals HBBS-to-HBBG base editing requirements for hematological correction.

(a) Bone marrow from a CD45.1 C57/BI6 mouse 16 weeks after primary transplantation with ABE8e-NRCH RNP-edited Lin− HSPCs from Townes SCD mice (CD45.2, HBBS/S) was mixed in varying proportions with bone marrow from a C57/BI6 mouse 16 weeks after transplantation with unedited HBBS/S HSPCs from a Townes SCD mouse. For each of six bone marrow mixtures, secondary transplantations of 2x106 cells were performed into three irradiated CD45.1 C57BI/6 recipient mice. Peripheral blood was analyzed after 16 weeks. (b) Engraftment measured by percentage of PBMCs with CD45.1. (c) HBBS-to-HBBG editing efficiency in PBMCs. (d) Percentage of βG among β-like globin proteins by HPLC and (e-h) hematologic indices plotted against HBBG allele frequency measured for each mouse. Parameters from non-transplanted HBBA/S (brown line) and HBBA/A (black line) Townes mice were assessed as healthy controls. One-phase decay fits are shown in (d), (f), (g), and (h), and a linear fit in (e). Bars values and error bars reflect mean±SD of n=3 mice. Dots represent different mice. Colors in (c-h) match the key in (b).

Mice receiving mixtures containing ≥60% marrow from the recipients of edited HSCs maintained HBBG allele frequencies of >20% following secondary transplant (Fig. 4c). In these mice, βG protein represented >70% of all β-like globins in blood (Fig. 4d), and hematologic parameters were similar to those of healthy HBBA/S and HBBA/A mice (Fig. 4e–h). Together, these results demonstrate durable base editing of long-term repopulating mouse HSCs and show that an HBBG allele frequency of ~20% in engrafted cells is sufficient to rescue hematologic phenotypes, a threshold substantially exceeded by the base editing strategy in this study.

Effects of nuclease and ABE treatment

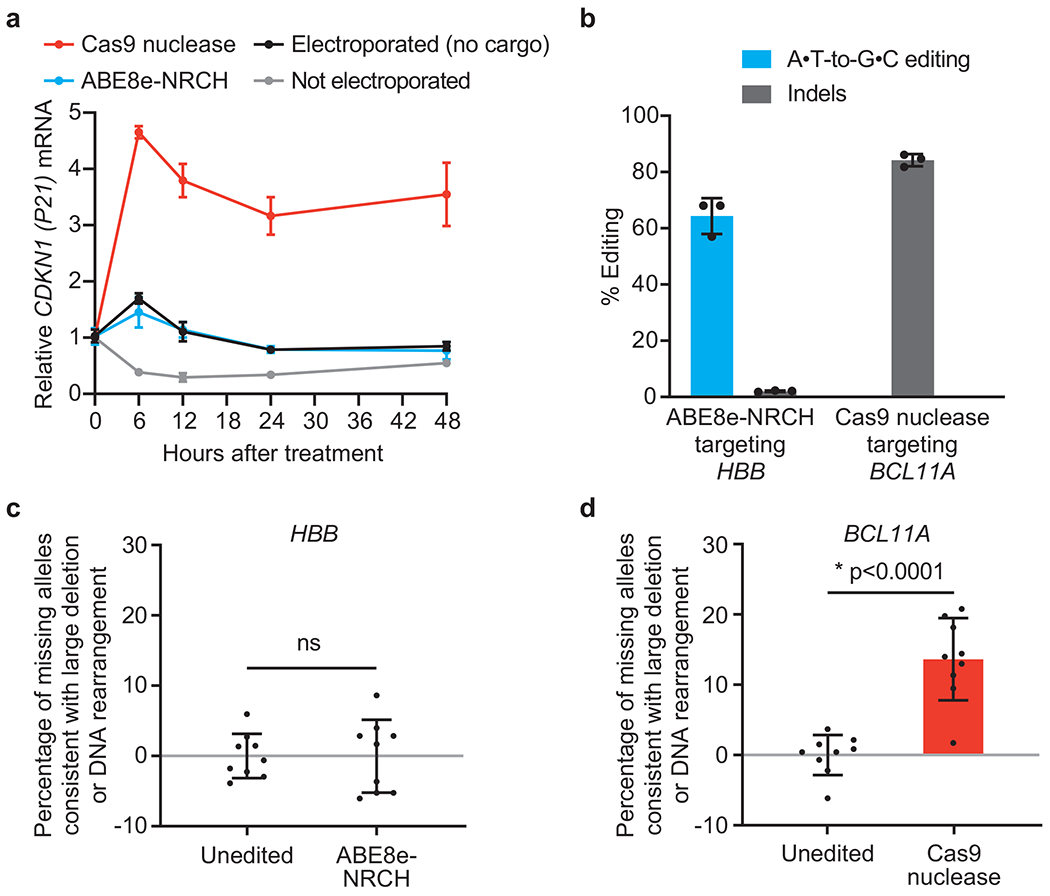

Induction of HbF via Cas9 nuclease-mediated disruption of an erythroid BCL11A enhancer is in clinical trials for the treatment of SCD and β-thalassemia12. Nuclease-mediated DSBs have been reported to stimulate DNA damage responses that can enrich oncogenic cells16,18, and to cause large DNA deletions or rearrangements that are difficult to detect by standard amplicon sequencing14,15. To compare DNA damage responses following ABE8e-NRCH or Cas9 treatment in HSPCs, we performed reverse transcription and droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) to measure CDKN1 (P21) expression, a readout of the p53-mediated DNA damage response (Extended Data Fig. 10a). We assessed untreated cells, cells electroporated with ABE8e-NRCH mRNA and sgRNA, cells electroporated with Cas9 nuclease RNP targeting the BCL11A enhancer, or cells electroporated with no cargo. HSPCs from a healthy donor were used and thus the sgRNA delivered with ABE8e-NRCH was altered by one nucleotide to match the wild-type HBB locus.

Nuclease-treated cells showed 2.7-fold higher average CDKN1 transcript levels 6 hours after treatment, and 4.2-fold higher levels after 48 hours, compared to control cells electroporated with no cargo (Extended Data Fig. 10a). In contrast, cells treated with base editor did not induce CDKN1 transcription beyond that of the no-cargo control cells. Six days after electroporation, DNA sequencing revealed 84±1.8% indels at the BCL11A locus in Cas9 RNP-treated cells and 64±5.2% adenine base editing at HBB protospacer position 9 in ABE8e-NRCH treated cells (Extended Data Fig. 10b).

To detect long deletions or rearrangements at the targeted loci that may be missed by standard amplicon sequencing14,15, we conducted ddPCR to quantify the amount of each target genomic locus 6 days after electroporation. Primers and probes for BCL11A were designed to hybridize outside the range of deletions previously described for Cas9-mediated editing at this locus, so only longer deletions or DNA rearrangements should cause apparent target locus loss. No change in HBB allele quantification was observed following base editor treatment (Extended Data Fig. 10c), but BCL11A allele quantification decreased by 14% following Cas9 nuclease treatment (Extended Data Fig. 10d) relative to non-targeted ACTB, suggesting long deletions or rearrangements occurred in at least 14% of BCL11A alleles. This frequency is consistent with recent findings in edited human embryos26. Together, these results are concordant with previous findings14 and suggest that base editor treatment of human HSPCs causes less p53 pathway stimulation and fewer large target site perturbations than Cas9 nuclease treatment.

Discussion

We describe a bespoke ABE that directly converts the major SCD allele to a β-globin variant that is non-pathogenic, even in homozygous4 or hemizygous21 form. This base editing strategy occurred efficiently (up to 80% editing in HSPCs and 68% in bone marrow-repopulating HSCs), with minimal bystander edits or indels, and yielded non-sickling RBCs without disruption of globin gene regulation or hematopoiesis.

Several approaches for autologous therapies to treat SCD are being tested in the clinic7,8,10–12. It is not yet known which strategy is safest or most effective. However, the base editing approach demonstrated here offers several potential advantages. First, elimination of the disease-causing mutation by precise HBBS-to-HBBG editing may reduce RBC sickle hemoglobin concentration, the primary determinant of pathogenic hemoglobin polymerization, more effectively than lentiviral β-like globin expression or induction of HbF, both of which leave HBBS alleles intact. While the latter approaches can decrease the fraction of βS in erythroid progeny by 30-70%27,28, we achieved even greater βS reduction in erythroid populations by base editing HBBS.

Second, base editing largely avoids DSBs generated by nucleases, which lead to uncontrolled mixtures of indels at the target site as well as large deletions, translocations, chromosomal loss, chromothripsis, and p53 DNA damage response activation13–18 (Supplementary References). Treatment of HSPCs with ABE8e-NRCH did not lead to detected p53 response or large deletions, in contrast to treatment with Cas9 nuclease (Extended Data Fig. 10).

Third, base editing does not require DNA delivery, a requirement for gene therapy or HDR. The introduction of DNA can lead to toxicity and insertional mutagenesis (Supplementary References). In contrast, base editing using mRNA or RNP directly converts pathogenic HBBS into a non-pathogenic allele with no exogenous DNA requirement.

We examined potential undesired consequences of base editing HSPCs. Base editors can cause bystander editing of nearby nucleotides. In this study, minimal non-synonymous bystander edits were observed (<2%) due to careful positioning of the bespoke ABE at a CACC PAM3 (Fig. 1a, Extended Data Fig. 1c). Spurious editing of RNA can occur29 but is short-lived when base editor mRNA or RNP is used, and did not appear to affect repopulation, viability, or differentiation of HSCs. Off-target base editing can also occur29, although on-target and off-target base editing in the same cell results in multiple point mutations that are less likely to be genotoxic than multiple DSBs from on- and off-target nuclease activity29. Of the 54 identified sites with observed off-target ABE8e-NRCH base editing in an extensive analysis of 697 computationally and experimentally nominated sites, no missense mutations or other off-target edits of anticipated consequence were found. Nevertheless, the safety and therapeutic potential of this approach may be further improved by testing alternative deaminase and Cas9 variants shown to minimize Cas-dependent and Cas-independent off-target base editing, optimizing editing agent dosage, or optimizing delivery methods2 (Supplementary References). Although HBBG is a naturally occurring benign variant, further studies are required to better understand the effects of this allele in combination with HBBS (Supplementary Discussion).

The ex vivo delivery procedure used in this study resembles methods currently used for HSC editing in clinical trials12. The ABEs were electroporated as mRNA or RNP to minimize the duration of exposure to the editing agent, reducing off-target editing compared to DNA delivery2. HSCs were edited using a single electroporation and transplanted into adult animals after 24 hours to minimize the duration of in vitro culture that can lead to the loss of HSC engraftment and multipotency. The phenotypic rescue observed following secondary transplantation of varying proportions of edited and unedited bone marrow establishes that the observed base editing efficiencies substantially exceed the gene correction threshold needed for therapeutic benefit. Base-edited patient-derived CD34+ cells thus provide a promising basis for a one-time autologous SCD therapy.

Methods

HEK293T cell culture and editing

HEK293T cells (ATCC CRL-3216) modified to contain the sickle cell allele3 were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Corning) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (ThermoFisher Scientific) and maintained at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Cells were verified to be free of mycoplasma by PCR test in growth media. Plasmid transfection of base editors in HEK293T cells has been previously described30–32. HEK293T cells were seeded for plasmid transfection at 20,000 cells per well on 96-well poly-D-lysine plates (Corning) in the same culture medium. Cells were transfected 24-30 h after plating with 0.5 μL Lipofectamine 2000 (ThermoFisher Scientific) using 200 ng base editor plasmid and 66 ng guide RNA plasmid following manufacturer’s instructions. The plasmid encoding the new ABE8e-NRCH generated for this study was deposited in AddGene (ID# 165416). Cells were cultured for 3 days following lipofection, then washed with PBS (ThermoFisher Scientific). Genomic DNA was extracted after removing PBS by addition of 50 μL freshly prepared lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 0.05% SDS, 25 μg/mL proteinase K (ThermoFisher Scientific)) directly into each transfected well. The mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 1 h then heat inactivated at 80 °C for 30 min. One microlitre of this lysate was used as a PCR template for high-throughput sequencing.

High-throughput sequencing of the HBB SCD locus in HEK293T cells

High-throughput sequencing (HTS) of genomic DNA was performed as previously described 30,31. Primers for amplification of the HBB SCD locus in HEK293T cells were: GAN162F: 5’-ACACTCTTTCCCTACACGACGCTCTTCCGATCTNNNNAGGGTTGGCCAATCTACTCCC-3’ GAN163R: 5’-TGGAGTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCTGTCTTCTCTGTCTCCACATGCC-3’. Underlined sequences represent adapters for Illumina sequencing. Following Illumina barcoding, PCR products were pooled and purified by electrophoresis with a 2% agarose gel using a Monarch DNA Gel Extraction Kit (New England Biolabs), eluting with 30 μL H2O. DNA concentration was quantified with Qubit dsDNA High Sensitivity Assay Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific) and sequenced on an Illumina MiSeq instrument (single-end read, 250–300 cycles) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. Alignment of fastq files and quantification of editing frequency was performed using CRISPResso233 in batch mode with a window width of 34 nucleotides.

ABE8e-NRCH mRNA

ABE8e-NRCH mRNA was transcribed in vitro from PCR product using full substitution of N1-methylpseudouridine for uridine. mRNA was capped co-transcriptionally using CleanCap AG analog (TriLink Biotechnologies) resulting in a 5’ Cap 1 structure. In vitro transcription reaction was performed as previously described34 with the following changes; 16.5 mM magnesium acetate and 4 mM CleanCap AG were used as the final concentration during transcription, and mRNAs were purified using RNeasy kit (QIAgen). Mammalian-optimized UTR sequences (TriLink) and a 120 base poly A tail were included in the transcribed PCR product.

ABE8e-NRCH protein

RNP delivery of genome editing agents has been previously described and established to decrease off-target editing activity compared to DNA delivery2,35–39. ABE8e-NRCH protein was codon optimized for bacterial expression and cloned into the protein expression plasmid pD881-SR (Atum, Cat. No. FPB-27E-269). This plasmid has been deposited on AddGene (ID# 165417). The expression plasmid was transformed into BL21 Star DE3 competent cells (ThermoFisher, Cat. No. C601003). Colonies were picked for overnight growth in terrific broth (TB)+25ug/mL kanamycin at 37 °C. The next day, 2 L of pre-warmed TB were inoculated with overnight culture at a starting OD600 of 0.05. Cells were shaken at 37 °C for about 2.5 hours until the OD600 was ~1.5. Cultures were cold shocked in an ice-water slurry for 1 hour, following which L-rhamnose was added to a final concentration of 0.8% to induce. Cultures were then incubated at 18 °C with shaking for 24 hours to express protein. Following induction, cells were pelleted and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 degrees. The next day, cells were resuspended in 30 mL cold lysis buffer (1 M NaCl, 100 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.0, 5 mM TCEP, 10% glycerol, with 5 tablets of cOmplete, EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail tablets (Millipore Sigma, Cat. No. 4693132001). Cells were passed three times through a homogenizer (Avestin Emulsiflex-C3) at ~18,000 psi to lyse. Cell debris was pelleted for 20 minutes using a 20,000 g centrifugation at 4 °C. Supernatant was collected and spiked with 40 mM imidazole, followed by a 1-hour incubation at 4 °C with 1 mL of Ni-NTA resin slurry (G Bioscience Cat. No. 786-940, prewashed once with lysis buffer). Protein-bound resin was washed twice with 12 mL of lysis buffer in a gravity column at 4 °C. Protein was eluted in 3 mL of elution buffer (300 mM imidazole, 500 mM NaCl, 100 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.0, 5 mM TCEP, 10% glycerol). Eluted protein was diluted in 40 mL of low-salt buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.0, 5 mM TCEP, 10% glycerol) just before loading into a 50 mL Akta Superloop for ion exchange purification on an Akta Pure25 FPLC. Ion exchange chromatography was conducted on a 5 mL GE Healthcare HiTrap SP HP pre-packed column (Cat. No. 17115201). After washing the column with low-salt buffer, the diluted protein was flowed through the column to bind. The column was then washed in 15 mL of low salt buffer before being subjected to an increasing gradient to a maximum of 80% high salt buffer (1 M NaCl, 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.0, 5 mM TCEP, 10% glycerol) over the course of 50 mL, at a flow rate of 5 mL per minute. 1-mL fractions were collected during this ramp to high-salt buffer. Peaks were assessed by SDS-PAGE to identify fractions containing the desired protein, which were concentrated first using an Amicon Ultra 15-mL centrifugal filter (100-kDa cutoff, Cat. No. UFC910024), followed by a 0.5-mL 100-kDa cutoff Pierce concentrator (Cat. No. 88503). Concentrated protein was quantified using a BCA assay (ThermoFisher, Cat. No. 23227).

Isolation and culture of CD34+ human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs)

Circulating G-CSF–mobilized human mononuclear cells were obtained from deidentified healthy adult donors (Key Biologics, Lifeblood). Plerixafor-mobilized CD34+ cells from patients with SCD were collected according to the protocol “Peripheral Blood Stem Cell Collection for Sickle Cell Disease Patients” (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT03226691), which was approved by the human subject research institutional review boards at the National Institutes of Health and St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. We complied with all relevant ethical regulations and all participants provided informed consent. Enrichment of CD34+ cells was performed by immunomagnetic bead selection using a CliniMACS Plus or AutoMACS instrument (Miltenyi Biotec). CD34+ cells were maintained in stem cell culture media: X-VIVO-10 (Lonza, BEBP02-055Q) media supplemented with 100 ng/μL human SCF (R&D systems, 255-SC/CF), 100 ng/μL human TPO (R&D systems, 288-TP/CF) and 100 ng/μL human Flt-3 ligand (R&D systems, 308-FK/CF). Cells were seeded and maintained at a density of between 0.5-1x106 cells/mL.

RNP and mRNA electroporation in human HSPCs

Electroporation was performed with an ATX MaxCyte electroporator using electroporation program HSC3. The modified synthetic sgRNA contained 2′-O-methyl modifications in the first three and last three nucleotides, and phosphorothioate bonds between the first three and last three nucleotides40 and was purchased from BioSpring. CD34+ HSPCs were thawed 48 hours before electroporation. mRNA and sgRNA were mixed at a 1:1 weight ratio prior to electroporation. RNPs were formed at a 1:1.5 ratio of ABE and Makassar sgRNA, and incubated for 20 minutes at room temperature prior to electroporation. mRNA/sgRNA were electroporated at 200 μg/mL of mRNA and RNP were electroporated at a final concentration of 9 μM of protein per reaction. 20-40 million cells/mL were electroporated in 100 μL of Maxcyte Buffer in OC-100 cartridges for transplantation into NBSGW animals. Electroporated cells were recovered in stem cell culture media composed of X-VIVO 10 media including cytokines (Flt-3 ligand, SCF, and TPO). Cells were maintained in culture at a density between 0.5-1x106 per mL. Genomic DNA was extracted on culture day 6 using QuickExtract buffer (Lucigen Cat. No. QE09050) then analyzed by HTS for editing efficiency.

High-throughput sequencing of the HBB SCD locus in blood cells

After editing, the HBB SCD locus was amplified from genomic DNA with oligonucleotide primers: Forward.LF: 5’-CTACACGACGCTCTTCCGATCTTGGCCAATCTACTCCCAGGAGCAGG-3’ Reverse. LR: 5’-CAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCTTCAAAGAACCTCTGGGTCCAAGGGT-3’ Underlined sequences represent adapters for Illumina sequencing. Following Illumina barcoding, PCR products were pooled and HTS was conducted using a MiSeq or MiniSeq (Illumina). Sequences were analyzed by joining paired reads and analyzing amplicons for indels or the desired test sequence using CRIS.py41. Indels were reported as the number of reads without the WT amplicon length.

Erythroid cell culture

Erythroid differentiation of CD34+ cells was performed using a 3-phase protocol42,43. Phase 1 (days 1–7): IMDM (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 12440061) with 2% human blood type AB plasma (SeraCare, 1810-0001), 3% human AB serum (Atlanta Biologicals, S40110) 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 15070063), 3 units/mL heparin (Sagent Pharmaceuticals, NDC# 25021-401-02), 3 units/mL EPO (Amgen, EPOGEN NDC # 55513-144-01), 200 μg/mL holo-transferrin (Millipore Sigma, T0665, 10 ng/mL human SCF (R&D systems, 255-SC/CF), and 1 ng/mL human interleukin IL-3 (R&D systems, 203-IL/CF). Phase 2 (days 8–14): Phase 1 medium without IL-3. Phase 3 (days 15–21): Phase 2 medium without SCF and with holo-transferrin concentration increased to 1 mg/mL. Cells were maintained daily at a density of 0.1 x 106/mL (phase 1), 0.2 x 106/mL (phase 2) and 1.0 x 106/mL (phase 3)

Erythroblast maturation was monitored by immuno-flow cytometry for the cell surface markers CD235a (BD Pharmingen Cat. No. 559943, 1:100 dilution), CD49d (BioLegend Cat. No. 304304, 1:20 dilution), and Band3 (Gift from X. An, 1:100 diltuion) (Supplementary Table 1). To quantify erythroblast enucleation, 1.5–5 × 105 CD34+-derived erythroid cells were incubated with Hoechst 33342 (Millipore Sigma Cat. No. B2261, 1:1000 dilution) for 20 min at 37 °C, fixed with 0.05% glutaraldehyde, and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100.

Hemoglobin quantification

High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) quantification of individual globin chains was performed using reverse-phase columns on a Prominence HPLC System (Shimadzu Corporation). The eluted proteins were identified by light absorbance at 220 nm using a diode array detector. For quantification of globin content from erythroid cells derived from in vitro differentiation of human CD34+ cells, the relative amounts of different β-like globin proteins were calculated from the area under the 220-nm peak and normalized according to the DMSO control. They are expressed as a fraction of the total β-like globins including normal β (βA ) sickle β (βS), Makassar β (βG), γ, and δ-globin.

In vitro sickling assay

Erythroid cells were incubated with Hoechst 33342 (Millipore Sigma Cat. No. B2261, 1:1000 dilution) for 20 mins at 37°c, Hoechst negative population were sorted using a SH800 (Sony Biotechnologies). Sorted cells (0.5-1.0 x 105 cells) were seeded into 12 or 96 well plate with 1mL or 0.1mL of phase 3 ED media under hypoxic conditions (2% O2) for 24 h. The IncuCyte® S3 Live-Cell Analysis System (Sartorius) with a 20× objective was used to monitor cell sickling, with images captured after 8 hours. The percentage of sickling was measured by manual counting of sickled cells versus normal cells based on morphology. For each sickling assay, >300 cells per condition were counted by researchers blinded to that condition. For mouse transplantation studies, mouse blood was diluted (1:5000) in RPMI media and seeded in 6 well plate with 3 mL of RPMI media before imaging in IncuCyte S3.

CIRCLE-seq off-target editing analysis

Genomic DNA from HEK293T cells was isolated using Gentra Puregene Kit (QIAGEN) according to manufacturer’s instructions. CIRCLE-seq was performed as previously described24,44. Briefly, purified genomic DNA was sheared with a Covaris S2 instrument to an average length of 300 bp. The fragmented DNA was end repaired, A tailed and ligated to a uracil-containing stem-loop adaptor, using KAPA HTP Library Preparation Kit, PCR Free (KAPA Biosystems). Adaptor ligated DNA was treated with Lambda Exonuclease (NEB) and E. coli Exonuclease I (NEB) and then with USER enzyme (NEB) and T4 polynucleotide kinase (NEB). Intramolecular circularization of the DNA was performed with T4 DNA ligase (NEB) and residual linear DNA was degraded by Plasmid-Safe ATP-dependent DNase (Lucigen). In vitro cleavage reactions were performed with 250 ng of Plasmid-Safe-treated circularized DNA, 90 nM of Cas9-NRCH protein, Cas9 nuclease buffer (NEB) and 90 nM of synthetic chemically modified sgRNA (BioSpring), in a 100 μl volume. Cleaved products were A tailed, ligated with a hairpin adaptor (NEB), treated with USER enzyme (NEB) and amplified by PCR with barcoded universal primers NEBNext Multiplex Oligos for Illumina (NEB), using Kapa HiFi Polymerase (KAPA Biosystems). Libraries were sequenced with 150 bp paired-end reads on an Illumina MiSeq instrument. CIRCLE-seq data analyses were performed using open-source CIRCLE-seq analysis software and default recommended parameters (https://github.com/tsailabSJ/circleseq).

CasOFFinder off-target editing analysis

Computational prediction of NRCH PAM-containing potential off-target sites with minimal mismatches relative to the intended target site (three or fewer mismatches overall, or two or fewer mismatches allowing G:U wobble base pairings with the guide RNA) was performed using CasOFFinder 23,45

Targeted amplicon sequencing by rhAmpSeq

On- and off-target sites identified by CIRCLE-seq and CasOFFinder were amplified from genomic from CD34+ donors using rhAMPSeq system (IDT), with primers listed in Supplementary Table 2. Sequencing libraries were generated according to manufacturer’s instructions and sequenced with 151-bp paired-end reads on an Illumina NextSeq instrument.

Quantification of base editing efficiency at evaluated off-target sites

The A•T-to G•C editing frequency for each position in the protospacer was quantified using CRISPRessoPooled (v2.0.41) with quantification_window_size 10, quantification_window_center −10, base_editor_output, conversion_nuc_from A, conversion_nuc_to G. The genomic features of all off-target sites were initially annotated using HOMER (v4.10)46. HOMER does not offer high resolution at regions near junctions between annotations, so confirmed off-target sites were inspected individually and annotated using the NCBI Genome Data Viewer. Both HOMER annotations and annotation by inspection are shown in Supplementary Table 2. The editing frequency for each site was calculated as the ratio between the number of reads containing the edited base (i.e., G) in a window from position 4 to 10 of each protospacer (where the NRCH PAM is positions 21-24) within which adenine base editing efficiency is typically maximal29, and the total number of reads. To calculate statistical significance of off-target editing for the ABE8e-NRCH mRNA or RNP treatments compared to control samples, we applied a Chi-square test for each of four samples (two donors, each with two replicates). The 2x2 contingency table was constructed based on the number of edited reads and the number of unedited reads in treated and control groups. FDR was calculated using the Benjamini/Hochberg method. The 54 reported significant off-targets were called based on: (1) FDR < 0.05 and (2) difference in editing frequency between treated and control > 0.5% for at least one treatment. The custom code used to conduct off-target quantification and the statistical analysis is available to download from this website: https://github.com/tsailabSJ/MKSR_off_targets.

Ethical approval for studies involving mice

All studies utilizing mice were approved by the St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee under Protocol 579 entitled “Genetic Models for the Study of Hematopoiesis”. Mice were maintained in the St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital Animal Resource Center according to recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health.

Transplantation of gene-edited CD34+ HSPCs into NOD.Cg-KitW-41J Tyr+ Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/ThomJ (NBSGW) mice

NBSGW mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (stock no. 026622). Cells were cultured 48 hours after thawing before electroporation, then cultured 24 additional hours before xenotransplanation. Minimization of time in culture is helpful to maintain repopulating stem cells47. Base edited or control CD34+ cells were administered at a dose of 0.2×106 per mouse with an IP injection of 10 mg/kg of busulfan (Busulfex; PDL BioPharm) 48 hours before infusion48 or 0.5×106 per mouse with no busulfan preconditioning by tail-vein injection in female mice aged 7-9 weeks. Chimerism post-transplantation was evaluated at 16-17 weeks in the bone marrow at the time of euthanasia. Cell lineage composition was determined in the bone marrow by using cell type-specific antibodies (Supplementary Table 1), and lineages were analyzed using the Attune NxT flow cytometer (ThermoFisher) and sorted using an Aria III cell sorter (BD Biosciences). The antibodies used were: anti-mouse CD45 (BD Pharmingen Cat. No. 561088, 1:40 dilution), anti-human CD45 (BD Horizon Cat. No. 564047, 1:20 dilution), anti-human CD33 (BD Biosciences Cat. No. 333946, 1:20 dilution), anti-human CD3 (BD Pharmingen Cat. No. 557832, 1:20 dilution), anti-human CD19 (BD Biosciences Cat. No. 349209, 1:20 dilution), anti-human CD34 (BD Pharmingen Cat. No. 561440, 1:20 dilution), anti-human CD235a (BD Pharmingen Cat. No. 551336, 1:20 dilution). CD34+ HSPCs or CD235a+ erythroblasts were isolated with magnetic beads, using the human-specific CD34 MicroBead Kit UltraPure (Miltenyi Biotec Inc., catalog # 130-100-453) and CD235a (glycophorin A) MicroBeads, human, (Miltenyi Biotec Inc., catalog # 130-050-501).

Single cell RNA-seq to determine clonal editing outcomes in human CD235a+ cells

CD235a+ cells were sorted from the bone marrow of mice 16 weeks after xenotransplantation of patient-derived CD34+ HSPCs into NBSGW mice using FACS. Sorted cells were than analyzed using the Chromium Next GEM Single Cell 5’ Reagent Kit V2 (dual index) (10x Genomics 1000263) and sequenced on an Illumina NovoSeq following the manufacturer’s protocol. Reads were mapped to hg38 using cellranger (v5.0.1). The allelic editing was analyzed using the 10x Genomics’ Vartrix tool (v1.1.19) to identify the genotypes (A/A, A/G, or G/G) at the disease-causing nucleotide, chr11:5227002, with the following parameters: --out-variants --primary-alignments --umi --out-barcodes --ref-matrix -s coverage. Cells were filtered out if <100 reads mapped to the first exon of HBB. A cell was assigned to A/A or G/G if all reads contain the A allele or the G allele, respectively. A cell was assigned to A/G if at least 100 reads contain the A allele and 100 reads contain the G allele. The average number of reads per cell mapped to HBB per cell was 3385. 339 cells from mouse 1 and 274 cells from mouse 2 were included in the analysis.

Base editing and transplantation of Townes Mouse SCD HSPCs

Townes SCD mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Stock# 013071). This strain harbors the human a-globin locus (HBA1) in place of the orthologous mouse loci Hba1 and Hba2, and the human γ-globin (HBG1) and β-globin (HBBS or HBBA) loci in place of the endogenous mouse loci Hbb-b1 and Hbb-b2. Bone marrow mononuclear cells were obtained by flushing femurs, tibias, hip bones and humeri with IMDM (10% FBS) followed by RBC lysis (ACK Lysing Buffer). Mixed male and female lineage marker negative (Lin−) cells enriched for HSPCs were purified by immuno-magnetic bead selection using the Mouse Lineage Cell Depletion Kit (Miltenyi, 130-090-858). Lin− cells were cultured in Lineage Negative Media: StemSpan SFEM supplemented with mSCF (100 ng/μL), mlL-3 (10 ng/μL), mlL-11 (100 ng/μL), hFLT3 ligand (100 ng/μL) and PenStrep (1X) for 24 hours prior to base editing. Pilot studies indicated that mouse HSPCs were edited more efficiently with RNP compared to base editor mRNA. Further optimization may reveal the reason for this or yield improved electroporation methods for mRNA. Ribonucleoprotein complex was generated by incubating ABE8e-NRCH with targeting sgRNA at concentrations of 2.25 μM base editor and 6.75 μM gRNA (1:3 ratio) in T buffer (total volume 50 μL) for 30 minutes at room temperature. Electroporation was performed using the ThermoFisher Neon Transfection System with 100-μL tips in buffer E2 at 1700 pulse voltage, 20 pulse width, 1 pulse.

Following electroporation, cells were cultured overnight in Lineage Negative Media, followed by transplantation via tail-vein injection of 106 cells into lethally irradiated (1,125 cGy delivered as a single dose), 8- to 12-week-old female C57BI/6 PepBoy (CD45.1) recipients. For analysis following transplantation peripheral blood was collected from the retro-orbital sinus using heparinized micro-hematocrit capillary tubes at 6, 10, 14, and 16 weeks after transplantation to determine the fraction of engrafted donor cells and hemoglobin content. Mice were sacrificed for necropsy at 16 weeks post-transplantation.

Complete blood counts CBCs were performed using a FORCYTE veterinary hematology analyzer. CBC measurements were collected from untransplanted HBBA/S mice at 4-6 months of age. Blood smears were prepared using modified Romanowsky methanolic staining and eosin and thiazin methods. Engraftment was determined by flow cytometry for mouse anti-CD45.1-PE (BD Pharmingen Cat. No. 553776, 1:50 dilution) and mouse anti-CD45.2-FITC (BE Pharmingen Cat. No. 561874, 1:50 dilution). Mouse illustrations were adapted from BioRender.com.

Colony forming assay and analysis of clonal editing outcomes

Lin− cells were purified from the bone marrow of three mice 16 weeks after transplantation using immuno-magnetic bead selection with the Mouse Lineage Cell Depletion Kit (Miltenyi, 130-090-858). For each animal, 500 Lin− cells were plated in triplicate in methylcellulose (STEMCELL Technologies, Methocult GF M3434) incubated at 37 °C. After 12 days, 30-35 colonies per mouse were picked and washed in PBS before prior to lysis. HTS analysis was performed on all colony lysates and allelic editing for each colony was classified based on editing percentages.

Oxygen binding measurements

Hemoglobin-oxygen equilibrium curves (OECs), to determine the oxygen binding affinity of HbA, HbS and HbG, were obtained using the Hemox Analyzer (TCS Scientific, New Hope, PA). Mouse blood or was added to the analysis buffer containing Hemox solution (pH 7.4 at 37 °C), Additive-A (BSA-20), and anti-foaming agent (AFA-25) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Each sample was oxygenated at 37 °C using compressed air and then deoxygenated with compressed N2, while subjected to continuous dual-wavelength spectrophotometry to determine the oxyhemoglobin to deoxyhemoglobin ratio along with continuous measurement of the oxygen partial pressure. OECs and p50 values were generated by the TCS Hemox Analysis Software.

Secondary transplantation of Townes mouse SCD HSPCs

Whole bone marrow from a single female Makassar base-edited mouse and a female mouse receiving unedited HBBS/S cells were collected and RBCs were lysed using ACK Lysing Buffer. Varying ratios of cells from the two mice (0:100, 20:80, 40:60, 60:40, 80:20, and 100:0) were mixed and resuspended in PBS. Two million cells per recipient were injected into irradiated female C57BI/6 PepBoy (CD45.1) recipients (1,125 cGy). Three mice were injected per ratio of bone marrow cells. For analysis following transplantation, peripheral blood was collected from the retro-orbital sinus using heparinized micro-hematocrit capillary tubes. Complete blood counts CBCs were performed using a FORCYTE veterinary hematology analyzer. Mouse illustrations were adapted from BioRender.com.

Cas9 nuclease purification

3xNLS-SpCas9 plasmid28 was transformed into BL21 (DE3) competent cells (MilliporeSigma, 702353) and grown in Terrific Broth (TB) media at 37 °C until the density reached OD600=2.4-2.8. Cells were induced with 0.5 mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) per liter for 20 hours at 20 °C. Cell pellets were lysed in 25 mM Tris, pH 7.6, 500 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol by homogenization and centrifuged at 20,000 rpm for 1 hour at 4 °C. Cas9 was purified by Nickel-NTA resin and treated with TEV protease (1 mg TEV per 40 mg of protein) and benzonase (100 units/mL, Novagen 70664-3) overnight at 4 °C. Subsequently, Cas9 was purified using a size exclusion column (Amersham Biosciences HiLoad 26/60 Superdex 200 17-1071-01) followed by a 5-mL SP HP ion exchange column (GE 17-1151-01) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Proteins were dialyzed in 20 mM Hepes buffer pH 7.5 containing 400 mM KCI, 10% glycerol, and 1 mM TCEP buffer. Contaminants were removed using a Toxin Sensor Chromogenic LAL Endotoxin Assay Kit (GenScript, L00350). Purified proteins were concentrated and filtered using Amicon ultrafiltration units with a 30-kDa MWCO (MilliporeSigma, UFC903008) and an Ultrafree-MC centrifugal filter (MilliporeSigma, UFC30GV0S). Protein fractions were further assessed using TGX stain-free 4-20% SDS-PAGE (Biorad, 5678093) and quantified by BCA assay.

Reverse transcription digital droplet PCR to assess CDKN1 expression

Healthy donor CD34+ HSPCs were electroporated with ABE8 NRCH mRNA+sgRNA targeting the HBB locus. In parallel, 3xNLS Cas9 nuclease RNP complexed with sgRNA targeting the BCL11A erythroid-specific enhancer was used to compare base editor to nuclease strategies. Cells electroporated without ABE8e-NRCH or 3xNLS Cas9 were used as a control (“electroporation, no cargo”), and as a separate control, cells were cultured without electroporation (“not electroporated”). mRNA and sgRNA were mixed at a 1:1 mass ratio prior to electroporation. RNPs were formed at a 1:1.5 ratio of Cas9 and sgRNA, and incubated for 20 minutes at room temperature to complex prior to electroporation. mRNA+sgRNA complexes were electroporated at 200 μg/mL of mRNA. Cas9 RNP was electroporated at a final concentration of 4 μM protein.

Guide RNA sequences were: BCL11A-targeting guide sequence: 5’-CUAACAGUUGCUUUUAUCAC-3’ Healthy HBB-targeting guide sequence: 5’-UUCUCCUCAGGAGUCAGGUG-3’ After electroporation, RNA was extracted from 100K cells at several time points (0, 6, 12, 24, and 48 hrs) using the RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (QIAGEN; Cat. No. #74136) and RNA concentrations were determined by Nanodrop (Thermo Scientific). Genomic DNA was extracted on day 6 post-electroporation using QuickExtract buffer then analyzed by HTS to determine editing efficiency.

One-step reverse transcription digital droplet PCR (RT-ddPCR) on extracted RNA was used to determine CDKN1 (p21) mRNA expression levels, upregulation of which indicates an active p53-mediated DNA damage response49. Ribonuclease P/MRP subunit p30 (RPP30) was used as reference control. 3 ng of RNA was mixed with reverse transcriptase, 300 mM DTT, and Supermix in One-Step RT-ddPCR advanced kit for probes (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA), CDKN1 primers/probe (Bio-Rad, 10031252; Assay ID: dHsaCPE5052298), and RPP30 primers/probe (Bio-Rad, 10031255; Assay ID: dHsaCPE5038241) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. After making droplets using an Automated Droplet Generator (Bio-Rad), thermocycling was performed as follows: 50 °C for 60 min, 95 °C for 10 min, then 40 cycles consisting of 95 °C for 30 sec followed by 55 °C for 1 min. Following the cycles, a final incubation was conducted at 98 °C for 10 min. Droplets were read using QX200 (Bio-Rad, 1864001) and data were analyzed using QuantaSoft (Bio-Rad).

Assessing target site disruption using digital droplet PCR

DNA from 100,000 CD34+ HPSCs were extracted using an Agencourt DNAdvance kit (Beckman Coulter Cat. No. A48705) according to manufacturer’s instructions. DNA concentrations were determined by Nanodrop (Thermo Scientific). Digital droplet PCR was used to determine change in abundance of target loci. 50-150 ng of DNA was added to a reaction mixture containing ddPCR Supermix for Probes (Bio-Rad, 1863026), HindIII-HF (0.25 units/μL, New England BioLabs, R3104L), ACTB primers and probes (900 nM each primer, 250 nM probe, Primers:

ACTB-Forward: 5’-ACACTGTGCCCATCTAC-3’

ACTB-Reverse: 5’-AATGTCACGCACGATTTC-3’

Probe: 5’-/5HEX/CGGGACCTG/ZEN/ACTGACTACCTCAT/3IABkFQ/−3’), and either HBB primers and probes (900 nM each primer, 250 nM probe, Primers:

HBB-Forward: 5’-GCCACACCCTAGGGTTG-3’

HBB-Reverse: 5’-GGGAAAATAGACCAATAGGCAG-3’

Probe: 5’-AGGGCTGGGCATAAAAGTCAG-3’ or BCL11A primers and probes (900 nM each primer, 250 nM probe, Primers:

BCL11A-Forward: 5’-TCTTAGACATAACACACCAGG-3’

BCL11a-Reverse: 5’-GTCTGCCAGTCCTCTTC-3’

Probe: 5’-TCAATACAACTTTGAAGCTAGTCTAGTG-3’) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Forward primers for amplification of HBB and BCL11A also contained the Illumina adapter at the 5’ end: ACACTCTTTCCCTACACGACGCTCTTCCGATCTNNNN. Reverse primers for amplification of HBB and BCL11A also contained the Illumina adapter at the 5’ end: TGGAGTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCT. Primers and probes for HBB were positioned to distinguish the target from the homologous HBD gene. Droplets were generated using a QX200 Manual Droplet Generator (Bio-Rad, 186-4002). Digital droplet PCR was performed as follows: 95 °C for 10 min, then 50 cycles of 94 °C for 30 seconds, 59.5 °C for 2 min. Following the cycles, a final incubation was conducted at 98 °C for 10 min. Droplets were read by a QX200 Droplet Reader (Bio-Rad, 1864001) and data were analyzed using QuantaSoft (Bio-Rad).

Extended Data

Extended Data Figure 1. Optimization in HEK293T cells, viability and recovery following human SCD patient HSPC editing, and allelic editing outcomes.

(a) Plasmids encoding the HBBS-targeting sgRNA and either ABE7.10-NRCH or ABE8e-NRCH were transfected by lipofection into HEK293T cells. Editing efficiency was measured after 3 days by high-throughput DNA sequencing (HTS). Unedited cells were not lipofected. (b) Two days after electroporation into human patient HSPCs of base editor mRNA and sgRNA, or electroporation of ribonucleoprotein (RNP), cell number and viability were measured using a Chemometec Nucleocounter-3000. Acridine orange was used to stain the total cell number and DAPI was used to stain dead, permeabilized cells. The percent viability was calculated as the DAPI stained cells divided by the acridine orange cells within each sample. The percent recovery was normalized to the cell count of the unedited sample. Unedited cells were not electroporated, (c) Six days after electroporation of SCD patient HSPCs, genomic DNA was extracted and the target HBB locus was PCR amplified and sequenced using an Illumina instrument. The sequencing analysis program CRIS.py was used to identify and quantify the resulting alleles. All alleles above a threshold of 0.2% frequency are shown. Below this threshold, variant alleles appear with greatest frequency in the untreated control sample, suggesting they do not arise from base editor treatment. Nucleotides altered from the endogenous sequence are shown in blue. Rare cytosine base editing was observed at <1% frequency, as has been previously described as a possible outcome from adenine base editing50. Bar values and error bars reflect mean±SD, n=3.

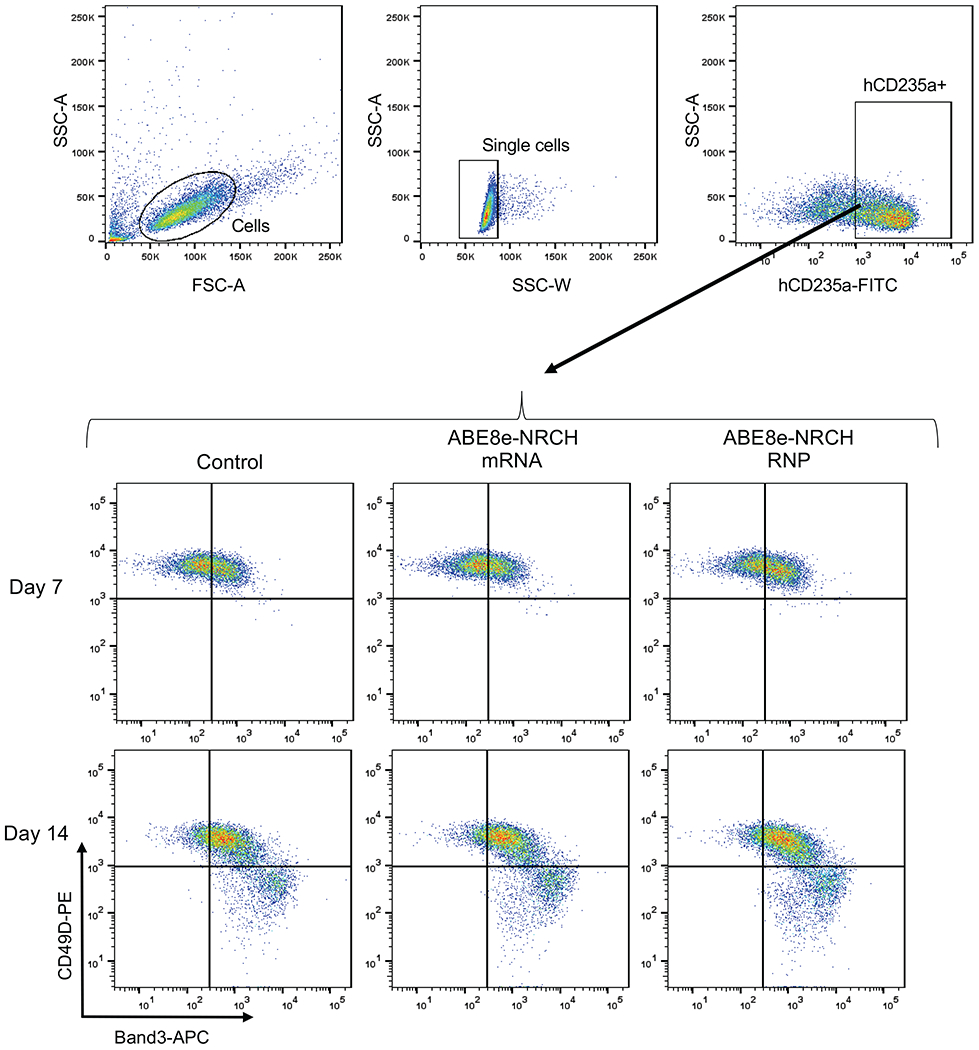

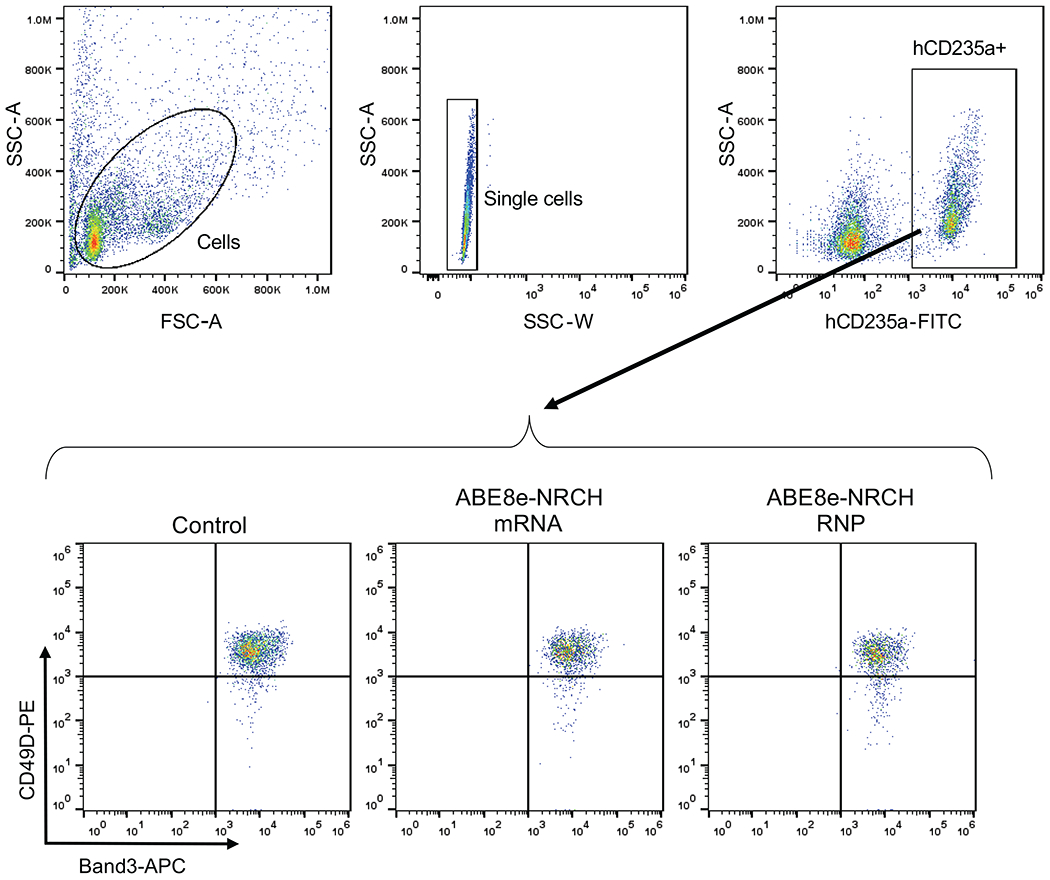

Extended Data Figure 2. Erythroid differentiation of edited SCD patient CD34+ HSPCs.

Representative, immuno-flow cytometry for erythroid maturation stage markers42,43 at culture days 7 and 14. Top: gating strategy to identify single cells expressing the erythroid marker hCD235a. Bottom: gating strategy to track the progress of erythroid maturation based on expression of CD49D and Band3 in hCD235a+ cells. SSC-A: Side scatter area. SSC-W: Side scatter width. FSC-A: Forward scatter area.

Extended Data Figure 3. Reverse-phase high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis of erythroid cells derived from in vitro differentiation of edited SCD patient CD34+ HSPCs.

Reverse-phase HPLC chromatograms of erythroid cell lysates at culture day 18, with β-like globins and their associated fractions marked near the associated peak. Data from the most efficiently edited donor is shown. Red arrows indicate the start and end of globin chain peaks.

Extended Data Figure 4. Off-target base editing associated with ABE8e-NRCH conversion of HBBS to HBBG Makassar in sickle cell disease patient CD34+ hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells.

CIRCLE-seq read counts obtained for each verified off-target site and the alignment of each site to the guide sequence are shown. Bar graphs show the percentage of sequencing reads containing A•T-to-G•C mutations within protospacer positions 4-10 at on-and off-target sites in genomic DNA samples from patient CD34+ HSPCs treated with ABE8e-NRCH mRNA, protein, or untreated controls (n=4). Note that the mutation frequency shown is summed across all reads with one or more A•T-to-G•C mutations in this window. Sequencing errors therefore accumulate in control samples compared to standard sequencing error frequencies for a single nucleotide. Bar values and error bars reflect mean±SD.

Extended Data Figure 5. Off-target indel formation associated with ABE8e-NRCH conversion of HBBS to HBBG Makassar in sickle cell disease patient CD34+ hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells.

Bar graph showing the percentage of sequencing reads containing alleles harboring indels at on-and off-target sites in genomic DNA samples from patient CD34+ HSPCs treated with ABE8e-NRCH mRNA, protein, or untreated controls (n=4). Bar values and error bars reflect mean±SD.

Extended Data Figure 6. Flow cytometry analysis of human donor-derived erythroid CD235a+ cells after transplantation.

(a) Human CD235a+ erythroid cells were purified by immuno-magnetic bead selection and analyzed by flow cytometry for the indicated erythroid maturation markers42,43, (b) Enucleated reticulocytes were assessed by the cell-permeable DNA stain Hoechst 33342 and the erythroid marker CD235a.

Extended Data Figure 7. Engraftment of ABE8e-NRCH RNP-treated SCD patient CD34+ HSPCs after transplantation into immunodeficient mice.

CD34+ HSPCs from three HBBS/S SCD patient donors were electroporated with ABE8e-NRCH RNP using a single guide RNA (sgRNA) targeting the SCD mutant codon, followed by transplantation of 2-5x105 treated cells into NBSGW mice via tail-vein injection. Mice were sacrificed and analyzed 16 weeks after transplantation, (a) Experimental workflow, (b) Engraftment measured by the percentage of human donor CD45+ cells (hCD45+ cells) in recipient mouse bone marrow, (c) Human B-cells (hCD19+), myeloid cells (hCD33+), and T-cells (hCD3+) cells in recipient mouse bone marrow, shown as percentages of the total hCD45+ population. (d) Human erythroid precursors (hCD235a+) in recipient mouse bone marrow shown as percentage of total human and mouse CD45−cells. (e) On-target (A7, Fig. 1a) editing efficiencies in human donor CD34+ cell-derived lineages purified from recipient bone marrow by fluorescence-activated cell sorting. Erythroid, myeloid, B-cell, and HSPC human lineages were collected using antibodies that recognize hCD235a, hCD33, hCD19, and hCD34+, respectively. Statistical significance was assessed by one-way ANOVA to compare groups; “ns”, not significant. (f) Percentages of β-like globin proteins determined by reverse-phase HPLC analysis of human donor-derived reticulocytes isolated from recipient mouse bone marrow. (g) Representative phase contrast images of human reticulocytes purified from bone marrow and incubated for 8 hours in 2% O2. Nine images of >50 cells per image were collected per sample. Scale bar=50 μm. (h) Quantification of sickled cells calculated by counting images after incubation for 8 hours in 2% O2 such as in (g). More than 300 randomly selected cells per sample were counted by a blinded observer. n=14 total mice analyzed in panels b-f; triangle, square, and circle symbols represent samples from three different SCD CD34+ HSPC donors. Negative control data is shared with Figure 2. Bar values and error bars reflect mean±SD. Statistical significance between treated and untreated samples was assessed by a two-tailed Student’s t-test; “ns”, not significant.

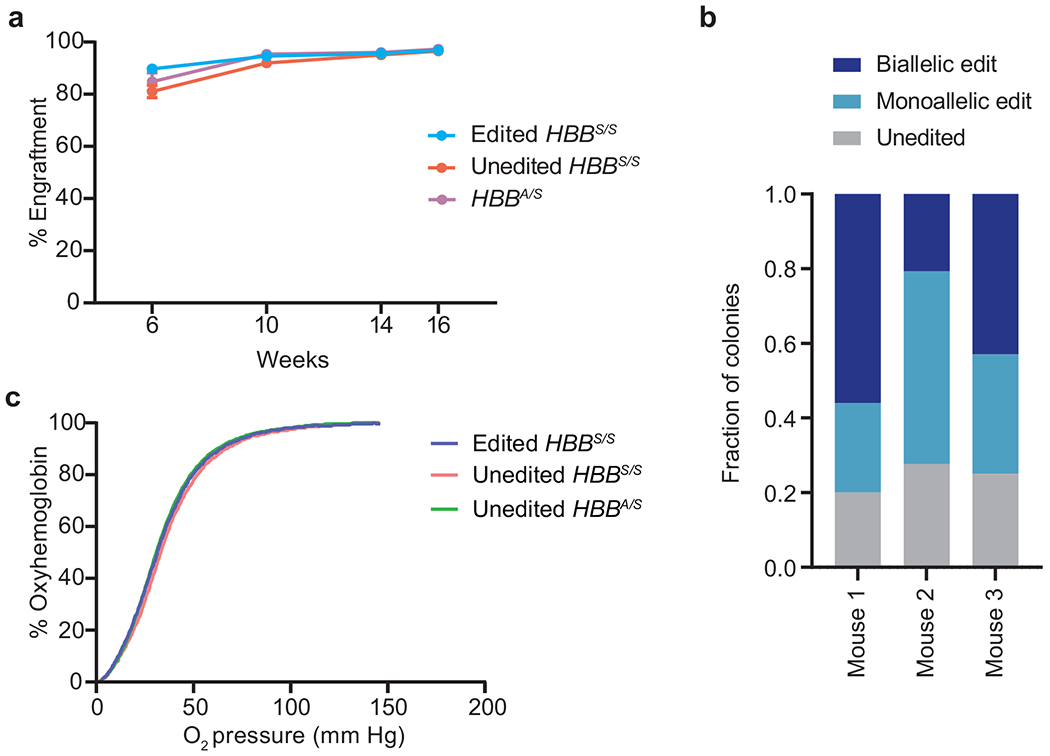

Extended Data Figure 8. Engraftment of transplanted Townes mouse HSPCs, clonality of editing outcomes, and oxygen binding affinity of blood.

(a) Donor cell engraftment measured by flow cytometry assessing the percentage of CD45.1+ cells among peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs). (b) Bone marrow from three mice transplanted with edited mouse HSPCs was plated at low density in methylcellulose. After 14 days of culture, 30 to 35 individual colonies per mouse were picked into cell lysis buffer and the edited locus was amplified by PCR and sequenced by HTS. Colonies were categorized by whether they contained no editing, a monoallelic edit, or a biallelic edit. (c) Blood was drawn from mice at week 14 after transplantation. Hemoglobin oxygenation was measured using a Hemox Analyzer (TCS Scientific) across a continuous declining gradient of oxygen pressure to assess whether HBBS-to-HBBG editing led to altered hemoglobin-oxygen binding. Bar values and error bars reflect mean±SD.

Extended Data Figure 9. Adenine base editing of the sickle cell disease β-globin allele (HBBS) to the Makassar variant (HBBG) reduces erythrocyte sickling and splenic pathologies in mice.

Mice were treated as described in Fig. 3a. Blood and spleen were analyzed sixteen weeks after transplantation of Lin− mouse HSPCs containing human HBB alleles, (a) Representative images of blood smears. One blood smear image was collected per mouse. Scale bar=25 μm. (b) Representative phase contrast images of peripheral blood incubated for 8 hours in 2% O2. Nine images of >50 cells per image were collected per sample. Scale bar=50 μm. (c) Quantification of sickled cells. More than 300 randomly selected cells were counted by a blinded observer. (d) Mass of dissected spleens. (e) Histological sections of spleens of recipient mice 16 weeks after transplantation. Splenic pathologies in mice that received unedited donor HBBS/S HSCs include excessive extramedullary erythropoiesis and vascular congestion indicated by RBC pooling (bright red color) resulting in expansion of red pulp (RP), reduction in white pulp sizes (WP), and splenomegaly. Images were taken at 10x magnification and were processed, stained and photographed at the same time under identical conditions. Three images of each spleen were collected from different parts of the organ for each mouse. Scale bar=100 μm. Unedited HBBS/S: n=6 mice; edited HBBS/S: n=6 mice; HBBA/S: n=2 mice. Plotted values and error bars reflect mean±SD, with individual values shown as dots. Statistical significance was assessed using one-way ANOVA, with Šidák’s multiple comparisons test of the edited HBBS/S values compared to each other group to calculate p-values.

Extended Data Figure 10. Comparison of DNA damage response and loss of target allele amplification consistent with large deletion or DNA rearrangement in HSPCs following treatment with Cas9 nuclease or with adenine base editor.

HSPCs from a healthy human donor were electroporated in triplicate with Cas9 nuclease RNP targeting the BCL11A erythroid-specific enhancer, ABE8e-NRCH mRNA and an sgRNA targeting the wild-type HBB locus, or no cargo as a control. An additional set of control cells was not electroporated, (a) CDKN1 transcription levels, a measure of the p53-mediated DNA damage response49, were quantified by droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) after reverse transcription, and were normalized to CDKN1 levels before electroporation (n=3). (b) Editing efficiencies at the targeted genomic loci in HSPCs were measured by HTS 6 days after electroporation. Adenine base editing at the synonymous bystander position 9 of the HBB protospacer is shown for ABE8e-NRCH. (c, d) The indicated target sites were amplified and quantified by ddPCR to measure the fraction of missing alleles consistent with larger deletions, translocations, or other chromosomal rearrangements that result in loss of the ability to be amplified by PCR. PCR amplification of a non-targeted ACTB site was used to normalize each sample. Each DNA sample was assessed in triplicate (n=9). Plotted values and error bars reflect mean±SD, with individual values in bar graphs shown as dots. Statistical significance between edited and unedited samples was assessed by a two-tailed Student’s t-test; “ns”, not significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the SCD patients who contributed samples for this study. We are grateful for helpful discussions with Daniel Gao and other members of our laboratories. We thank Mary O’Reilly for assistance with Adobe Illustrator. This work was supported by US National Institutes of Health awards U01 AI142756, RM1 HG009490, R01 EB022376, R35 GM118062 (D.R.L.) and P01 HL053749 (M.J.W. and S.Q.T.), the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (D.R.L.), the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (D.R.L.), the St. Jude Collaborative Research Consortium (D.R.L, S.M.P.-M., S.Q.T and M.J.W.), the Doris Duke Foundation (for aspects of this study that did not utilize mice, M.J.W., S.Q.T. and A.S.), the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (A.S. and M.J.W.) and the Assisi Foundation of Memphis (M.J.W.). G.A.N. was supported by a Helen Hay Whitney Postdoctoral Fellowship and the HHMI. A.S. was supported by a Scholar Award by the American Society of Hematology. L.W.K and K.A.E. acknowledge NSF GRFP fellowships.

Footnotes

Competing interests

Authors have filed patent applications on base editing through the Broad Institute. D.R.L. is a consultant and equity owner of Beam Therapeutics, Prime Medicine, and Pairwise Plants, companies that use genome editing. M.J.W. is on advisory boards for Cellarity Inc., Novartis, and Forma Therapeutics, and is an equity owner of Beam Therapeutics. A.S. is a consultant for Spotlight Therapeutics and his institution receives clinical trial support for the conduct of sickle cell disease gene editing trials from Vertex Pharmaceuticals, CRISPR Therapeutics, and Novartis. J.S.Y is an equity owner of Beam Therapeutics. The authors declare no competing non-financial interests.

Data Availability

HTS sequencing files can be accessed using the NCBI SRA (PRJNA725249).

Code Availability

The code used to conduct off-target quantification and the statistical analysis is available here: https://github.com/tsailabSJ/MKSR_off_targets.

Supplementary Information is available in the online version of the paper.

References

- 1.Piel FB, Steinberg MH & Rees DC Sickle Cell Disease. N Engl J Med 377, 305, doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1706325 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Richter MF et al. Phage-assisted evolution of an adenine base editor with improved Cas domain compatibility and activity. Nat Biotechnol 38, 883–891, doi: 10.1038/s41587-020-0453-z (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller SM et al. Continuous evolution of SpCas9 variants compatible with non-G PAMs. Nat Biotechnol 38, 471–481, doi: 10.1038/s41587-020-0412-8 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sangkitporn S, Rerkamnuaychoke B, Sangkitporn S, Mitrakul C & Sutivigit Y Hb G Makassar (beta 6:Glu-Ala) in a Thai family. J Med Assoc Thai 85, 577–582 (2002). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blackwell RQ, Oemijati S, Pribadi W, Weng MI & Liu CS Hemoglobin G Makassar: beta-6 Glu leads to Ala. Biochim Biophys Acta 214, 396–401 (1970). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu LC et al. Correction of sickle cell disease by homologous recombination in embryonic stem cells. Blood 108, 1183–1188, doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-004812 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leonard A, Tisdale J & Abraham A Curative options for sickle cell disease: haploidentical stem cell transplantation or gene therapy? Br J Haematol 189, 408–423, doi: 10.1111/bjh.16437 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Magrin E, Miccio A & Cavazzana M Lentiviral and genome-editing strategies for the treatment of beta-hemoglobinopathies. Blood 134, 1203–1213, doi: 10.1182/blood.2019000949 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zeng J et al. Therapeutic base editing of human hematopoietic stem cells. Nat Med 26, 535–541, doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0790-y (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ribeil JA et al. Gene Therapy in a Patient with Sickle Cell Disease. N Engl J Med 376, 848–855, doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1609677 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Esrick EB et al. Post-Transcriptional Genetic Silencing of BCL11A to Treat Sickle Cell Disease. N Engl J Med , doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2029392 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frangoul H et al. CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Editing for Sickle Cell Disease and beta-Thalassemia. N Engl J Med , doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2031054 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]