Abstract

Oryza sativa cv. PTT1 (Pathumthani1) was treated with phenyl-urea-based synthetic cytokinin under drought stress. Soluble sugar contents were examined in rice flag leaves at tillering and grain-filling stages. The same leaf samples were used to analyze the differential abundance intensities of proteins related to metabolism and transport of soluble sugars, and the process of senescence. The results showed drought-induced accumulation of hexose sugars (glucose and fructose) in rice flag leaves, which could be corroborated with enhanced accumulation of MST8 under drought stress. On the other hand, cytokinin-treated plants maintained the normal contents of hexose sugar in their flag leaves under drought stress, alike well-watered plants. In the case of sucrose, cytokinin treatment reduced its accumulation at tillering stage, but the results were reversed at the grain-filling stage, where the cytokinin-treated plants maintained significantly higher contents of sucrose under drought stress. Growth stage dependent variations in sucrose contents corroborated with the accumulation of SPS (SPS1, SPS2, and SPS5) proteins, implicated in sucrose biosynthesis. In our study, among the proteins involved in sucrose transport, SUT1 transporter was induced by drought stress at both the growth stages, whereas SUT2 transporter accumulated equally in all the treatments. However, cytokinin treatment reversed the effect of drought on the accumulation of SUT1. Similarly, SWEET5, and SWEET13 proteins, which were induced by drought stress treatment, were inhibited by cytokinin treatment. However, the accumulation SWEET6, SWEET7, and SWEET15 was not influenced by the treatment of cytokinin in the flag leaves of rice. In addition, cytokinin treatment reduced the leaf wilting, enhanced the fresh weight and grain yield, and curtailed the accumulation of proteins involved in drought-induced senescence. In conclusion, the cytokinin treatment had a positive agro-economic impact on the rice plants and provided better drought adaptability.

Keywords: Rice, Proteome, Cytokinin, Sugar, Drought tolerance

Introduction

Drought is one of the major problems worldwide that affects 1–3% of the land surface and is predicted to increase to up to 30% by 2090 (Burke et al. 2008). Over 50% of the rice cultivation area worldwide is rain-fed which contributes only one-quarter of total production (Rasheed et al. 2020). Drought stress impairs plant growth and development by affecting various biochemical and physiological processes. Plants counter the osmotic stresses by triggering complex stress signaling cascade that results in differential regulation of several regulatory and functional genes (Yamaguchi-Shinozaki and Shinozaki 2006; Gujjar et al. 2014a, b). Exogenously applied cytokinins have recently been implicated in mediating the cellular responses to drought acclimation via modulating various growth-related parameters like MSI (membrane stability index), photosynthetic pigments, chlorophyll stability index, leaf RWC (relative water content), and soluble sugars (Nagar et al. 2015; Chang et al. 2016; Kumari et al. 2018; Samea-Andabjadid et al. 2018; Gujjar and Supaibulwatana 2019; Gujjar et al. 2020). Furthermore, cytokinins help in sustaining better plant growth under osmotic stress conditions, ultimately leading to improved yield (Yang et al. 2016; Joshi et al. 2018; Prerostova et al. 2018). The application of synthetic cytokinins has been advantageous to rice in terms of enhancing the growth and yield (Zahir et al. 2001; Gujjar et al. 2020). Cytokinins facilitate growth and yield by relapsing the conventional transcriptional program activated under abiotic stress. Under stress conditions, cytokinins stimulate the expression of genes related to growth processes and inhibit the expression of genes associated with premature senescence (Gujjar and Supaibulwatana 2019). Increased levels of CK suppress the activity of xanthine dehydrogenase, one of the crucial enzymes involved in the biosynthesis of ABA (Cowan et al. 1999). Cytokinins also act as antagonists to ethylene-induced senescence (Liu et al. 2017) and biosynthesis, sensitivity, and signaling of ABA during drought stress (Gujjar and Supaibulwatana 2019). CPPU (N-2-(chloro-4-pyridyl)-N-phenyl urea), a phenyl-urea-based synthetic cytokinin, is a competitive inhibitor of cytokinin oxidase/dehydrogenase (CKX) that helps the plants to retain enhanced cytokinin concentration (Kopečný et al. 2010; Nisler et al. 2016). The previous studies of our laboratory indicated the positive impact of cytokinin spray (at 5 mg⋅L−1 CPPU) on the process of photosynthesis in rice under drought stress (Gujjar et al. 2020), the contents of soluble sugars in a medicinal plant, Andrographis paniculata (Worakan et al. 2017), and the adaptability of rice to salinity stress (Gashaw et al. 2014).

As drought severity increases, plants encounter drought through the accumulation of intracellular osmoprotectant compounds to protect cellular components and to restore the osmotic balance. Soluble sugars act as key osmoprotectants in plants during osmotic stresses. To support the growth of newly developing tissues under water-deficit stress conditions, they (predominantly glucose and fructose) are remobilized from older to young and apical leaves (Dubey and Singh 1999; Mohammadkhani and Heidari 2008; Mostajeran and Rahimi-Eichi 2009; Nemati et al. 2011; Boriboonkaset et al. 2013). Drought hampers the photosynthetic fixation of carbon into sugars and affects their transport by decreasing the cellular osmotic potential. Consequently, these drought stress-mediated adjustments result in the reprogramming of sugar distribution across the cellular and subcellular compartments (Kaur et al. 2021). Cellular sugar transport is carried out by a specific set of sugar transporter proteins. Three sugar transporter families, prevalent in plants, are monosaccharide transporters (MSTs), sucrose transporters (SUTs), and SWEETs (Sugars Will Eventually be Exported Transporters) (Misra et al. 2019; Hennion et al. 2019). These transporter proteins are the key determinant of the influx/efflux of various sugars to support plant growth and development during water-deficit stress conditions (Kaur et al. 2021). The drought-induced remobilization of soluble sugars is accompanied by proteolytic degradation of older tissues via senescence-associated cysteine proteases, leading to premature senescence of older leaves (Diaz-Mendoza et al. 2016; Sade et al. 2018). Enhanced cytokinin concentration, achieved by either IPT overexpression or exogenous application of synthetic cytokinin, results in redistribution of soluble sugars under osmotic stresses (Zhang et al. 2010; Peleg et al. 2011; Xiao et al. 2017; Gujjar and Supaibulwatana 2019). Consequently, major hexose sugars like glucose and fructose are mobilized back to other plant parts to avoid excess accumulation of soluble sugars in young leaves under osmotic stresses (Reguera et al. 2013). Our study examines the effect of external cytokinin application on the re-distribution of soluble sugars in flag leaves of PTT1 rice cultivar. PTT1 is a semi-dwarf, photoperiod-insensitive, rice variety that can be grown year-round (Sreethong et al. 2018). Being drought-susceptible (Yooyongwech et al. 2013), it is widely grown in the dry season in Thailand’s irrigated rice areas.

We investigated the accumulation patterns of proteins related to metabolism and transport of soluble sugars and the process of senescence, as influenced by cytokinin treatment in rice. We have also analyzed the impact of cytokinin treatment on the growth and morphological parameters of rice under drought stress.

Materials and methods

Plant material, CPPU and drought stress treatments

Oryza sativa ssp. Indica cv. PTT1 seeds were procured from the Laboratory of Plant Physiology and Agri-biotechnology, Faculty of Science, Mahidol University, Bangkok. PTT1 is a drought-sensitive cultivar of rice (Yooyongwech et al. 2013). Seeds were disinfected by sodium hypochlorite (Chlorox® 10% v/v) and were allowed to germinate in dark for 4 days in the double-layered germination trays (l × w × d = 30 × 15 × 2.5 cm) on moistened filter papers. The germinated seedlings were then exposed to light and were supplemented with half-strength Yoshida solution (Yoshida et al. 1971) for 14 days at room temperature (modified from Gashaw et al. 2014). Seedlings (5 cm long, with true leaves) were transplanted to experimental blocks filled with sand and soil (2:1) at the greenhouse, Salaya Campus, Mahidol University. Experimental blocks were supplemented with working Yoshida solution regularly to balance essential nutrient contents. Tensiometers (Soil Moisture, USA) were installed in experimental blocks to keep a check on soil moisture tension. Drought treatment was executed by with-holding water up to 14 days, whereas sufficient soil moisture (soil moisture tension was − 15 kPa) was maintained for control/well-watered plants. Exogenous cytokinin treatment was given by foliar spraying plants with 5 mg⋅L−1 solutions of forchlorfenuron®/CPPU (Kyowa Hakko Kogyo Co., Tokyo) at the rate of 25 ml/plant (Gujjar et al. 2020). CPPU solution was added with 0.1% Tween 20® that was used as a leaf surfactant. Control plants were sprayed with 0 mg⋅L−1 CPPU solution at the same time. Plants were sprayed with CPPU solution only once on day 6 of drought stress (soil moisture tension − 55 kPa). Samples were collected in three biological replicates to examine morphological, physiological, and biochemical changes on day 7 (soil moisture tension − 60 kPa) and day 14 (soil moisture tension − 72 kPa) of drought stress treatment. A total of three treatments were used in the experiment: (1) well-watered (WW) plants; (2) drought-stressed (DR) plants; and (3) drought-stressed with 5 mg⋅L−1 CPPU (DR-CPPU) plants. The experiments were conducted separately during 2 different growth stages of rice viz. tillering stage (60 days after germination) and grain-filling stage (75 days after germination). All the physiological, biochemical, and proteomic investigations were conducted on flag leaves with three biological replications.

Analysis of morphological and physiological parameters

The fresh weight of the plant was recorded immediately after de-rooting the plant and removing residual soil from roots. Leaf wilting was rated based on a visual scale of 0% to 100% with 100% indicating complete, permanent wilting of the leaves (Man et al. 2011). This was calculated by comparing the number of permanently wilted leaves and total leaves in a plant using the following formula: leaf wilting percentage was calculated from numbers of permanently wilted leave (per total numbers of leave) × 100 (Pungulani et al. 2013). Drought-stressed plants were re-watered after 14 days of drought period and were maintained at optimum soil moisture until harvest time to record grain yield.

Analysis of soluble sugars

Total soluble sugars were analyzed spectrophotometrically at 490 nm with some modifications in the protocol of Dubois et al. (1956). About 100 mg of fresh flag leaf tissue was ground with liquid nitrogen and homogenized in 1 ml of sterile water in 1.5 ml Eppendorf tubes. The homogenized mixture was shaken for 1 min, sonicated for 15 min, and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 15 min. The supernatant (sugar extract) was collected and filtered with Whatman® filter paper. Soluble sugar extract at 0.5 ml was saturated with 0.5 ml of 5% phenol in separate test tubes followed by the addition of 2.5 ml 95% H2SO4. The mixture was shaken for 5 min and placed in a water-bath at 30 °C for 20 min. Then, 2 ml of the mixture was analyzed by spectrophotometer (GENESYS™ 10S UV–Vis Spectrophotometer) at 490 nm for total soluble sugars. Glucose (Fluka) was used for the preparation of the standard curve. Quantification of individual soluble sugars (sucrose, glucose, and fructose) was done according to the modified method of Karkacier et al. (2003). Fresh flag leaf tissue (100 mg) was ground with liquid nitrogen and homogenized with 1 ml of nanopure water in 1.5 ml Eppendorf tubes. The homogenized mixture was shaken vigorously for 1 min., sonicated for 15 min. and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 15 min. The supernatant was collected in separate Eppendorf tubes and filtered through a 0.45 μm membrane filter (VertiPure™, Vertical®) into HPCL (high performance liquid chromatography) vials. Filtered samples were stored at − 20 °C prior to the measurement of total soluble sugar contents using HPLC. Sample (filtered extract) volume of 15 μL was injected into Waters HPLC (Waters Associates, Milford, MA, USA) fitted with a Waters 600 pump using a MetaCarb 87C column equipped with a guard column. De-ionized water was used as the mobile phase at the flow rate of 0.4 mL⋅min−1. Peaks of different sugars were detected by Waters 410 differential refractometer detector, and the data were analyzed by Empower® software. Sucrose, glucose, and fructose (Fluka) were used as standards.

Protein extraction and sample preparation for shotgun proteomics

Fresh flag leaf samples were collected in biological triplicates from all treatment combinations of drought and CPPU for differential proteomic analysis. Proteins were extracted using a modified version of the protocol described by Shen et al. (2008). Briefly, 100 mg tissues were ground to a fine powder in liquid nitrogen and homogenized in pre-cooled 1 ml TCA extraction buffer (10% TCA in 100% acetone added with 0.07% fresh 2-mercaptoethanol). Samples were vortexed, incubated at − 20 °C for 1 h, and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 5 min. Supernatants were discarded and precipitates were washed 3 times with ice–cold acetone solution (acetone containing 0.07% 2-mercaptoethanol). The precipitates were dried in the oven at 55 °C, dissolved with lysis buffer (30 mM Tris-base (Tris hydroxymethyl aminomethane), 7 M urea, 2 M thiourea, 4% CHAPS, pH 8.5), vortexed and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 15 min. Supernatants, containing crude protein mixtures, were collected after centrifugation and stored at − 20 °C. The concentration of proteins was measured using BSA (bovine serum albumin) as a standard protein (Lowry et al. 1951) and absorbance was taken by Microplate Reader-TECAN (Spark 10 M) at 595 nm. Due to a large number of samples, 10 µg protein samples from each biological replicate were mixed for further LC–MS analysis. To reduce disulfide bonds, 10 mM dithiothreitol in 10 mM ammonium bicarbonate was added to the protein solution, and reformation of disulfide bonds in the proteins was blocked by alkylation with 30 mM iodoacetamide in 10 mM ammonium bicarbonate. The protein samples were digested with sequencing grade porcine trypsin (1:20 ratio) for 16 h at 37 °C. The tryptic peptides were dried using a speed vacuum concentrator and re-suspended in 0.1% formic acid for nano-liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (nano-LC–MS/MS) analysis.

Liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC/MS) and data analysis

Tryptic peptide samples were injected in triplicate into an HCTUltra LC–MS system (Bruker Daltonics Ltd; Hamburg, Germany), coupled with a nano-LC system: UltiMate 3000 LC System (Thermo Fisher Scientific; Madison, WI, USA) as well as an electrospray at the flow rate of 300 nL∙min−1 to a nanocolumn (PepSwift monolithic column 100 mm internal diameter 50 mm). Mobile phases consisting of solvent A (0.1% formic acid) and solvent B (80% acetonitrile and 0.1% formic acid) were used to elute peptides using a linear gradient of 10–70% of solvent B at 0–13 min (the time point of retention), followed by 90% B at 13–15 min to transfer all peptides in the column. The final elution of 10% B at 15–20 min was carried out at the end to remove any remaining salt. The quantitation of LC–MS/MS data was performed by Differential Analysis software (DeCyderMS, GE Healthcare) (Johansson et al. 2006; Thorsell et al. 2007), and the identification of proteins was performed by searching against the Oryza sativa non-redundant subset database of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository with the data set identifier PXD021005. Searches were performed with a maximum of three missed cleavages, carbamidomethylation of Cys as a fixed modification, and oxidation of Met as variable modifications. Protein scores were derived from ion scores as nonprobabilistic ranking protein hits and obtained as the sum of peptide scores. Data normalization and the quantification of the changes in protein abundance were performed among different treatments by MultiExperiment Viewer (MeV) in the TM4 suite software (Howe et al. 2011). The relative abundances of peptides were presented as log2 abundance intensities. The highest log2 abundance intensity value among the three technical replicates was used as the representative value of that treatment.

Results and discussion

Cytokinin curbs the drought-induced accumulation of hexose sugars in flag leaves

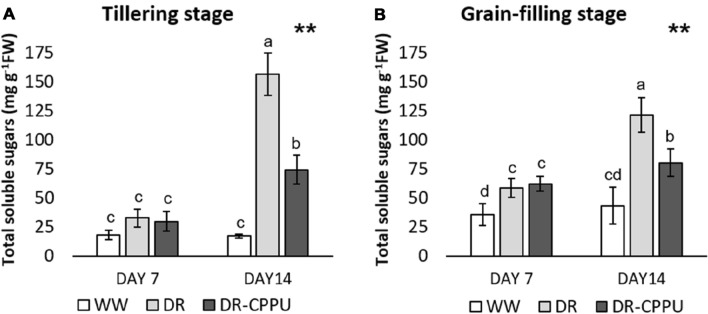

Drought triggers the remobilization of soluble sugars, predominantly glucose and fructose, from older leaves to young and apical leaves under osmotic stress conditions (Dubey and Singh 1999; Mostajeran and Rahimi-Eichi 2009; Nemati et al. 2011; Boriboonkaset et al. 2013), which can be reversed by an enhanced concentration of cytokinins (Peleg et al. 2011; Reguera et al. 2013; Gashaw et al. 2014). In the present study, we examined the effect of cytokinin treatment on the contents of total soluble sugars during drought stress, by the spectrophotometric quantification in the flag leaves (Fig. 1A, B). Across all the treatments, the total soluble sugar contents did not change significantly on day 7 of drought stress (− 60 kPa) at tillering stage. On the other hand, there was a notable impact of drought on day 7 of drought stress (–60 kPa) at grain-filling stage, where the drought-stressed plants retained enhanced contents of total soluble sugars in their flag leaves, compared to well-watered plants. With the progression of drought (day 14; − 72 kPa), there was a considerable influence of CPPU on the contents of total soluble sugars at both tillering and grain-filling stages of rice. Evidently, the total soluble sugar contents increased significantly under severe drought stress conditions. Cytokinin treatment, on the other hand, overturned the effect of drought on the contents of total soluble sugars in the flag leaves of rice.

Fig. 1.

Total soluble sugar contents (mg g−1 FW) in rice flag leaves, analyzed spectrophotometrically, under different treatment conditions at tillering (A) and grain filling (B) stages. WW well-watered plants (soil moisture tension of − 15 kPa), DR drought-stressed plants (Soil moisture tension of − 55 kPa and − 72 kPa at ‘day 7’ and ‘day 14’, respectively), and DR-CPPU drought-stressed plants, sprayed with 5 mg L−1 CPPU on ‘day 6’ of drought treatment. Error bars represent SD (standard deviation). Letters viz. a, b, c, and d present over SD bars indicate highly significant differences of mean at p < 0.01 (**), as analyzed by Duncan’s Multiple Range Test (DMRT)

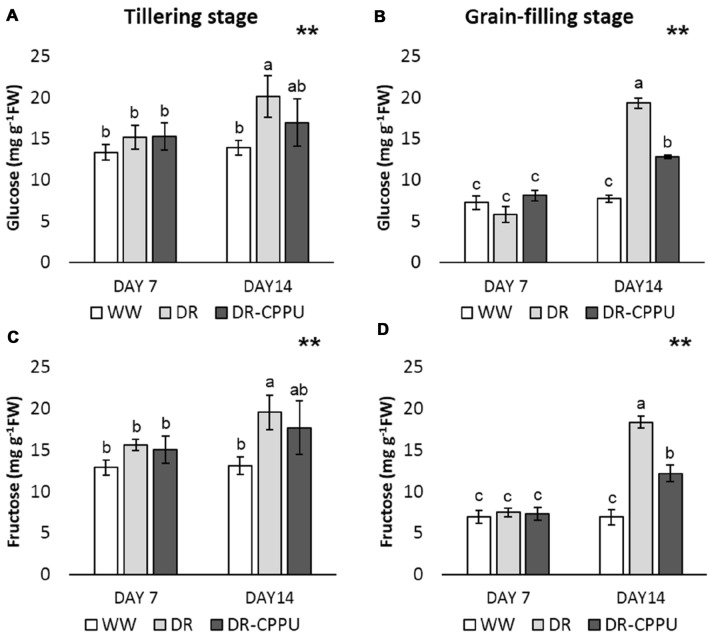

To precisely scrutinize and comprehend the effect of cytokinin treatment on the accumulation of the two major hexose sugars (glucose and fructose), we performed HPLC-based quantification of these sugars in the flag leaves of rice (Fig. 2A–D). The results indicated a virtually similar effect of cytokinin spray on the concentration of glucose and fructose under drought stress. The concentration of both glucose and fructose remained unaffected by drought on day 7 of drought stress, which may be attributed to the mild drought condition of − 60 kPa. However, on day 14 of drought stress, a noticeable upsurge was evident in the contents of both the hexose sugars in drought-stressed plants at tillering as well as grain-filling stages. Nevertheless, cytokinin treatment reversed the effect of drought stress on the accumulation of glucose and fructose, which was signified by relatively low levels of glucose and fructose sugars in cytokinin-treated flag leaves under drought stress at both tillering and grain-filling stages. The results imply drought-induced re-mobilization of hexose sugars from older leaves to flag leaves, which is curtailed by cytokinin treatment at both the growth stages of rice.

Fig. 2.

Glucose (A, B) and fructose (C, D) contents (mg g−1 FW) in rice flag leaves, analyzed by HPLC, under different treatment conditions at tillering and grain filling stages. WW well-watered plants (soil moisture tension of − 15 kPa), DR drought-stressed plants (Soil moisture tension of − 55 kPa and − 72 kPa at ‘day 7’ and ‘day 14’, respectively), and DR-CPPU drought-stressed plants, sprayed with 5 mg L−1 CPPU on ‘day 6’ of drought treatment. Error bars represent SD (standard deviation). Letters viz. a, b, and c present over SD bars indicate highly significant differences of mean at p < 0.01 (**), as analyzed by Duncan’s Multiple Range Test (DMRT)

Furthermore, we investigated the effect of cytokinin treatment on the accumulation of monosaccharide transporters (MSTs), MST6, MST7, and MST8, in flag leaves under drought stress (Table 1). MST proteins, localized on the plasma membranes, are the H+/hexose cotransporters, implicated in the transport of glucose, fructose, and some other monosaccharides from source to sink (Williams et al. 2000; Wan et al. 2020). They are also involved in different processes of plant growth and development and accumulate differentially in response to abiotic stresses (Deng et al. 2019). In our investigation, the accumulation of MST8 was marginally enhanced in drought-stressed plants, compared to well-watered and cytokinin-treated plants of tillering stage. The results can be corroborated with the contents of total soluble sugars, including glucose and fructose, at tillering stage. However, at grain-filling stage, MST8 accumulated more in cytokinin-treated plants under drought stress, which is in contradiction with the results of soluble sugar contents in flag leaves of grain-filling stage plants. The accumulation of MST6 and MST7 transporters remained largely unaffected by either drought or CPPU treatment in our experiment.

Table 1.

Abundance intensities of monosaccharide transporters (MSTs) in rice (PTT1) flag leaves under different treatments

| GI No. | Name of protein | Well-watereda | Droughtb | Drought-CPPUc | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tillering | Grain-filling | Tillering | Grain-filling | Tillering | Grain-filling | ||||||||

| Day 7 | Day 14 | Day 7 | Day 14 | Day 7 | Day 14 | Day 7 | Day 14 | Day 7 | Day 14 | Day 7 | Day 14 | ||

| gi|75325405 | MST6 | 14.84 | 16.30 | 13.62 | 16.39 | 15.05 | 14.29 | 13.56 | 14.36 | 14.71 | 16.15 | 16.91 | 15.32 |

| gi|75332135 | MST7 | 16.58 | 18.79 | 17.79 | 18.48 | 16.11 | 16.72 | 17.33 | 19.01 | 15.94 | 16.40 | 16.23 | 18.26 |

| gi|75332136 | MST8 | 15.41 | 16.59 | 16.88 | 16.55 | 19.29 | 19.09 | 18.06 | 18.73 | 16.23 | 16.82 | 21.63 | 21.78 |

Biological triplicates were pooled into one and were further divided into three technical replicates. The highest log2 intensity value among the three technical replicates was used as the representative value of that treatment

aWell-watered plants were maintained at a soil moisture tension of − 15 kPa during the treatment period

bDrought stress was imposed by withholding water for up to 14 days. Soil moisture tensions of − 55 kPa and − 72 kPa were recorded on day 7 and day 14 during the treatment, respectively

cCPPU treatment was given by foliar spraying plants with a 5 mg/L solution of CPPU (N-2-(chloro-4-pyridyl)-N-phenyl urea) at the rate of 25 mL per plant on day 6 of drought treatment

Effect of cytokinin on the metabolism and transport of sucrose during drought stress

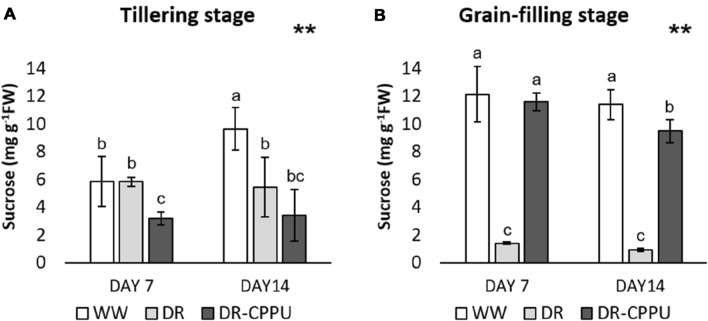

In plants, sucrose is the end product of photosynthesis and the main sugar for translocation from photosynthetic tissues (source) to non-photosynthetic tissues (sinks) through the phloem (Ruan 2014; Stein and Granot 2019). At the cellular level, sucrose is the primary carbon source for growth, development, and defense responses. In our study, the sucrose contents largely contrasted with glucose and fructose in response to cytokinin treatment under drought stress (Fig. 3A, B). Furthermore, the concentration varied drastically at tillering and grain-filling stages. At tillering stage, cytokinin-treated flag leaves retained noticeably lesser contents of sucrose, compared to flag leaves of well-watered and drought-stressed plants. On the other hand, sucrose contents at grain-filling stage were drastically low in the flag leaves of drought-stressed plants, compared to well-watered and CPPU-treated plants. Contrary to hexose sugars, the accumulation of sucrose was curtailed by drought stress in the flag leaves at both the growth stages. To substantiate our findings at the molecular level, we examined the effect of CPPU on the accumulation of proteins related to metabolism and transport of sucrose under drought stress (Table 2). The biosynthesis of sucrose is regulated by the sequential action of two key enzymes, sucrose phosphate synthase (SPS) and sucrose phosphate phosphatase (SPP). SPS converts UDP-glucose and fructose-6-phosphate into sucrose-6-phosphate, whereas SPP removes the orthophosphate (Pi) from sucrose-6-phosphate to yield sucrose as the final product (Koch 2004; Ruan 2014). We examined the abundance intensities of SPS1, SPS2, SPS5, and SPP3 in the flag leaf tissues of rice under different treatments of drought and cytokinin at tillering and grain-filling stages. Besides the noteworthy impact of cytokinin, the accumulation of SPS1, SPS2, and SPS5 proteins also varied in response to different growth stages of rice under drought stress. In the case of SPS1, the cytokinin treatment revealed contrasting regulation at tillering and grain-filling stages. Treatment of cytokinin repressed the accumulation of SPS1 at tillering stage, but induced its accumulation at grain-filling stage. The accumulation of the other two enzymes implicated in sucrose biosynthesis, SPS2, and SPS5, was also induced by cytokinin treatment at grain-filling stage of rice. The abundance intensities of all the three SPS proteins (SPS1, SPS2, and SPS3) corroborated impeccably with the results of HPLC-based sucrose content analysis in the flag leaves of rice. The accumulation of SPP3 protein, on the other hand, remained unaffected by either drought or CPPU treatment in our study. Henceforth, it can be suggested that cytokinins regulate the penultimate step of sucrose synthesis in rice (conversion of UDP-glucose and fructose-6-phosphate into sucrose-6-phosphate).

Fig. 3.

Sucrose contents (mg g−1 FW) in rice flag leaves, analyzed by HPLC, under different treatment conditions at tillering (A) and grain filling (B) stages. WW well-watered plants (soil moisture tension of − 15 kPa), DR drought-stressed plants (Soil moisture tension of − 55 kPa and − 72 kPa at ‘day 7’ and ‘day 14’, respectively), and DR-CPPU drought-stressed plants, sprayed with 5 mg L−1 CPPU on ‘day 6’ of drought treatment. Error bars represent SD (standard deviation). Letters viz. a, b, and c present over SD bars indicate highly significant differences of mean at p < 0.01 (**), as analyzed by Duncan’s Multiple Range Test (DMRT)

Table 2.

Abundance intensities of rice (PTT1) flag leaf proteins, implicated in metabolism and transport of sucrose, under different treatments

| GI No. | Name of protein | Well-watereda | Droughtb | Drought-CPPUc | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tillering | Grain-filling | Tillering | Grain-filling | Tillering | Grain-filling | ||||||||

| Day 7 | Day 14 | Day 7 | Day 14 | Day 7 | Day 14 | Day 7 | Day 14 | Day 7 | Day 14 | Day 7 | Day 14 | ||

| gi|158564091 | SPS1 | 15.79 | 14.46 | 17.58 | 17.08 | 14.98 | 15.36 | 10.33 | 8.98 | 8.25 | 7.26 | 16.27 | 15.96 |

| gi|353678155 | SPS2 | 15.36 | 14.40 | 13.17 | 13.97 | 8.30 | 7.97 | 7.86 | 8.51 | 7.27 | 7.45 | 11.52 | 12.24 |

| gi|75269159 | SPS3 | 14.40 | 13.34 | 18.73 | 17.86 | 13.06 | 14.45 | 13.60 | 12.98 | 13.71 | 14.93 | 18.60 | 16.67 |

| gi|206558124 | SPP3 | 15.60 | 16.93 | 17.25 | 16.89 | 17.86 | 14.72 | 16.60 | 16.20 | 15.59 | 17.36 | 16.95 | 15.18 |

| gi|122247483 | SUT1 | 17.72 | 15.02 | 16.65 | 15.36 | 18.91 | 19.24 | 19.65 | 19.33 | 16.66 | 16.37 | 16.31 | 17.52 |

| gi|158564095 | SUT2 | 14.80 | 16.80 | 14.65 | 16.87 | 14.89 | 15.75 | 16.91 | 15.50 | 15.47 | 14.44 | 16.87 | 16.16 |

| gi|75126698 | SWEET5 | 12.73 | 13.64 | 15.34 | 16.03 | 15.20 | 15.00 | 16.03 | 17.26 | 8.32 | 10.22 | 10.37 | 11.07 |

| gi|75161759 | SWEET6 | 18.33 | 18.18 | 17.41 | 18.19 | 18.03 | 16.95 | 17.91 | 17.71 | 18.07 | 16.97 | 18.78 | 17.15 |

| gi|939108054 | SWEET7 | 14.54 | 15.99 | 14.88 | 15.88 | 15.45 | 15.15 | 14.36 | 15.20 | 13.61 | 13.60 | 13.51 | 14.05 |

| gi|122204154 | SWEET13 | 15.25 | 14.49 | 15.34 | 16.62 | 14.07 | 15.84 | 14.07 | 14.99 | 9.65 | 10.67 | 10.69 | 8.69 |

| gi|75125443 | SWEET15 | 17.92 | 17.09 | 17.42 | 18.09 | 16.80 | 17.07 | 17.33 | 18.56 | 18.21 | 19.18 | 17.76 | 17.03 |

| gi|401140 | SuSy1 | 18.38 | 17.54 | 17.32 | 17.02 | 17.84 | 18.31 | 18.24 | 18.04 | 18.14 | 18.41 | 19.95 | 17.94 |

| gi|109940175 | SuSy3 | 19.11 | 19.20 | 18.80 | 18.71 | 16.28 | 15.84 | 17.23 | 17.41 | 17.79 | 17.64 | 18.45 | 18.21 |

| gi|122247037 | SuSy4 | 15.92 | 17.06 | 15.90 | 16.78 | 16.13 | 16.73 | 15.95 | 14.60 | 17.71 | 15.13 | 15.80 | 13.13 |

| gi|403377889 | SuSy5 | 17.63 | 16.44 | 16.48 | 17.47 | 18.01 | 16.50 | 16.32 | 17.25 | 18.61 | 16.75 | 17.03 | 18.53 |

| gi|75261422 | SuSy6 | 17.99 | 17.50 | 16.58 | 15.76 | 18.49 | 17.54 | 15.91 | 17.67 | 16.94 | 17.63 | 18.95 | 16.21 |

| gi|75259112 | INV3, chl | 16.67 | 16.91 | 16.43 | 16.17 | 12.22 | 13.60 | 11.30 | 12.55 | 13.07 | 12.27 | 11.27 | 11.45 |

| gi|75254382 | INV1, Cyt | 15.24 | 16.67 | 17.51 | 16.66 | 15.76 | 16.04 | 15.83 | 16.43 | 16.28 | 15.40 | 13.68 | 12.16 |

| gi|122247104 | INV1, mit | 18.95 | 16.62 | 15.71 | 17.78 | 11.20 | 10.35 | 12.03 | 9.11 | 18.99 | 18.01 | 20.57 | 19.38 |

Biological triplicates were pooled into one and were further divided into three technical replicates. The highest log2 intensity value among the three technical replicates was used as the representative value of that treatment

SPS sucrose phosphate synthase, SPP sucrose phosphate phosphatase, SUT sucrose transporters, SWEET sugars will eventually be exported transporters, SuSy sucrose synthetase, INV invertase

aWell-watered plants were maintained at a soil moisture tension of − 15 kPa during the treatment period

bDrought stress was imposed by withholding water for up to 14 days. Soil moisture tensions of − 55 kPa and − 72 kPa were recorded on day 7 and day 14 during the treatment, respectively

cCPPU treatment was given by foliar spraying plants with a 5 mg/L solution of CPPU (N-2-(chloro-4-pyridyl)-N-phenyl urea) at the rate of 25 mL per plant on day 6 of drought treatment

Among the soluble sugars synthesized in a plant, sucrose is the major transport form of carbon found in the phloem. Subsequent to its biosynthesis in photosynthetically active tissues, sucrose is loaded in the sieve element–companion cell complex (phloem) for its transport to sink tissues. The loading and unloading of sucrose are carried out by different sugar transporters viz. SUT and SWEET proteins (Chen et al. 2012; Julius et al. 2017), which are tightly regulated by environmental stresses (Lemoine et al. 2013; Xu et al. 2018). SUTs, also known as sucrose/H+ symporters, are involved in the transport of sucrose to sink tissues in plants through phloem. In a study performed to investigate the influence of environmental cues on SUT proteins, rice SUT1 was upregulated, while SUT2 was downregulated under drought stress conditions (Xu et al. 2018). In our study, SUT1 transporter was induced by drought stress at both the growth stages, whereas SUT2 transporter accumulated equally in all the treatments. However, cytokinin treatment reversed the effect of drought on the accumulation of SUT1, similar to well-watered plants. SUT1 transporter, responsible for the transport of sucrose into the cell, is also required for apoplastic phloem sucrose loading in source tissues (e.g., leaves) to transport it to sink tissues (Sun et al. 2010). SWEETs are recently characterized families of sugar transporters, implicated in various plant developmental processes and environmental stresses (Eom et al. 2015; Yang et al. 2018; Misra et al. 2019; Jeena et al. 2019). In pursuit of investigating the effect of cytokinin on these transporter proteins under drought stress, we analyzed the abundance intensities of SWEET (SWEET5, SWEET6, SWEET7, SWEET13, SWEET15) transporters in the flag leaves of rice. Drought stress, discretely, had no significant effect on the accumulation of SWEET proteins at tillering and grain-filling stages. However, cytokinin treatment reduced the accumulation of two SWEET transporters, SWEET5 and SWEET13, in flag leaves of rice at both the growth stages. On the other hand, the accumulation of other SWEET transporters, SWEET6, SWEET7, and SWEET15, was not influenced by the treatment of cytokinin in the flag leaves of rice. SWEET5 and SWEET13 transporters, implicated in the efflux of sugars across the plasma membrane, are primarily involved in phloem loading of sucrose from the source (Streubel et al. 2013; Zhou et al. 2014; Mathan et al. 2020). SWEET5 proteins have also been ascribed for their role to promote senescence and prevent growth in rice (Zhou et al. 2014). Cytokinin-mediated repression of SWEET5 transporters might be ascribed to contribute in the process of delaying the drought-induced senescence. OsSWEET13 and OsSWEET15 transporters, involved in regulating the sucrose transport and levels in response to the abiotic stresses, were induced by abscisic acid (ABA)‐responsive transcription factor OsbZIP72 that directly binds to the promoters of OsSWEET13 and OsSWEET15 and activates their expression (Mathan et al. 2020). Largely, our study on the accumulation patterns of proteins involved in sugar metabolism and transport suggests that cytokinins antagonize the effect of drought on these proteins. Under stress conditions, plants typically follow the strategy to survive with minimum resources that leads to reduced growth and yield. Cytokinins counteract the drought-induced changes in the plants to allow them to maintain normal growth and development under stressful environments (Huang et al. 2018; Gujjar and Supaibulwatana 2019).

Sucrose, after being unloaded from the phloem to the apoplast of sink tissues, enter the sink cells either directly via SUTs or gets hydrolyzed by invertases (INV) to yield glucose and fructose, which can enter the sink cells via MSTs (Ma et al. 2019; Stein and Granot 2019). To support the growth of sink cells, sucrose is enzymatically metabolized into its hexose monomers by either sucrose synthases (SuSys) or INVs (Ruan 2014; Wan et al. 2018). SuSys, using UDP, catalyze the reversible cleavage of sucrose to yield fructose and UDP-glucose, whereas INVs catalyze the irreversible cleavage of sucrose into glucose and fructose (Wan et al. 2018; Yao et al. 2020). To discover the effect of cytokinin treatment on these sucrose-hydrolyzing enzymes, we studied the abundance intensities of SuSys (SuSy1, SuSy3, SuSy4, SuSy5, SuSy6) and INVs (cytosolic INV1, mitochondrial INV1, chloroplastic INV3) in flag leaves of rice under drought stress. In our study, the accumulation of all the five SuSys remained unaffected under the treatments of drought and cytokinin, whereas INVs displayed an altered accumulation in response to cytokinin treatment under drought stress. Cytosolic INV1 was marginally repressed by the treatment of cytokinin at grain-filling stage of rice. The other two, mitochondrial INV1 and chloroplastic INV3, were suppressed by drought stress at tillering as well as grain-filling stage. However, cytokinin treatment reversed the effect on drought and induced the accumulation of mitochondrial INV1. INVs have been ascribed for their functions in sugar partitioning during stress conditions, thus facilitating the delayed senescence via an effect on source–sink relationships (Balibrea Lara et al. 2004; Ruan et al. 2010; Albacete et al. 2015).

Cytokinins uphold the growth and restrain the drought-induced leaf wilting and senescence

Senescence represents the final developmental stage of the leaf in which the nutrients invested in the leaf are remobilized to newly growing parts of the plant. Following the remobilization of nutrients, the process of senescence is accomplished by the action of senescence-associated cysteine proteases that facilitate the proteolysis of old leaves (Diaz-Mendoza et al. 2016; Poret et al. 2016; Botha et al. 2017; Wang et al. 2019a, b). Furthermore, the activities of cysteine proteases are strictly controlled by specific inhibitors called cysteine protease inhibitors (CPIs) (Pak and Van Doorn 2005; Rustgi et al. 2018). Customarily, leaf senescence is complemented by a decline in cytokinin content. It has been frequently reported that the exogenous application of cytokinins or an increase of the endogenous cytokinin concentration causes the redistribution of nutrients and delays leaf senescence (Gan and Amasino 1995; Ma et al. 2018; Wang et al. 2019a, b; Gujjar and Supaibulwatana 2019). To explore the effect of exogenous cytokinin on CPs and CPIs, we examined the abundance intensities of CP1, CPI6, and CPI12 in rice flag leaves during drought stress (Table 3). Rice CP1 has been characterized for its role in inducing programmed cell death (PCD) of tapetum (Lee et al. 2004). In our study, CP1 protein was significantly induced by drought stress, whereas cytokinin treatment suppressed its accumulation under drought stress. On the other hand, cytokinin treatment triggered the accumulation of CPI6, a key enzyme for constraining the proteolytic activities of CPs. The results suggest a positive impact of cytokinin treatment in delaying the leaf senescence in rice under drought stress.

Table 3.

Abundance intensities of rice (PTT1) flag leaf proteins, implicated in the process of senescence, under different treatments

| GI No. | Name of protein | Well-watereda | Droughtb | Drought-CPPUc | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tillering | Grain-filling | Tillering | Grain-filling | Tillering | Grain-filling | ||||||||

| Day 7 | Day 14 | Day 7 | Day 14 | Day 7 | Day 14 | Day 7 | Day 14 | Day 7 | Day 14 | Day 7 | Day 14 | ||

| gi|62510688 | CP1 | 9.20 | 8.23 | 7.28 | 8.78 | 16.02 | 15.45 | 17.42 | 17.56 | 12.79 | 12.36 | 10.72 | 11.91 |

| gi|122247388 | CPI6 | 17.31 | 17.63 | 15.14 | 14.72 | 13.84 | 15.00 | 14.39 | 14.10 | 17.88 | 17.16 | 17.97 | 18.45 |

| gi|122228720 | CPI12 | 19.04 | 18.05 | 18.40 | 20.60 | 20.09 | 20.53 | 18.03 | 19.22 | 19.27 | 17.70 | 21.18 | 18.51 |

Biological triplicates were pooled into one and were further divided into three technical replicates. The highest log2 intensity value among the three technical replicates was used as the representative value of that treatment

CP cysteine protease, CPI cysteine protease inhibitor

aWell-watered plants were maintained at a soil moisture tension of − 15 kPa during the treatment period

bDrought stress was imposed by withholding water for up to 14 days. Soil moisture tensions of − 55 kPa and − 72 kPa were recorded on day 7 and day 14 during the treatment, respectively

cCPPU treatment was given by foliar spraying plants with a 5 mg/L solution of CPPU (N-2-(chloro-4-pyridyl)-N-phenyl urea) at the rate of 25 mL per plant on day 6 of drought treatment

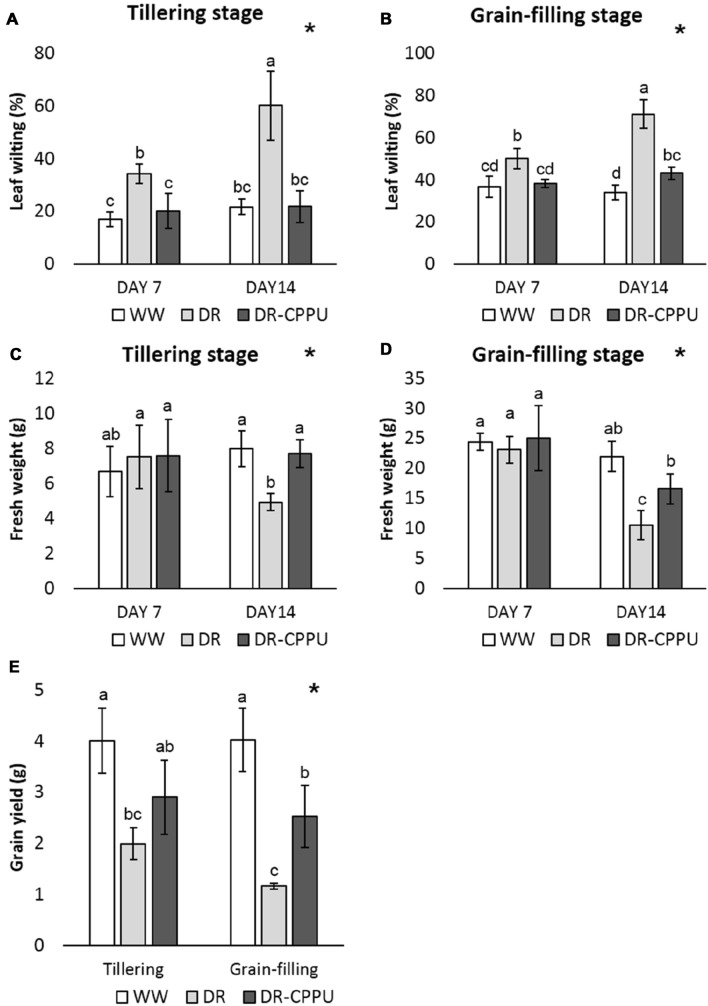

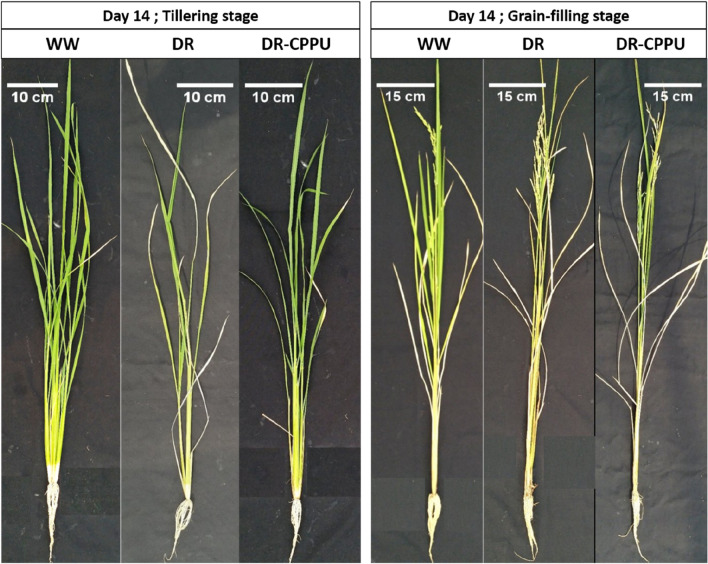

Cytokinins are known to encourage shoot growth and multiple shooting in plants. Elevation in cytokinin contents results in improved plant biomass and grain yield (Peleg et al. 2011; Gashaw et al. 2014; Yang et al. 2016; Gujjar and Supaibulwatana 2019). To unravel the growth and morphological adjustments arbitrated by cytokinin under drought stress, we examined the changes in leaf wilting (Fig. 4A, B), plant biomass (Fig. 4C, D), and grain yield (Fig. 4E). Leaf wilting, one of the key indicators of drought stress, was prompted by drought stress in all the plants at tillering and grain-filling stages. However, cytokinin-treated plants had considerably less leaf wilting, compared to untreated plants under drought stress. There were marginal differences in plant fresh weight on day 7 of drought stress (just one day after cytokinin spray) in all the treatments. On day 14 of drought stress, cytokinin-treated plants recorded significantly higher biomass compared to untreated plants under drought stress. Cytokinin-driven upsurge in plant fresh weight was evident at both tillering and grain-filling stages. To investigate the effect of cytokinin on grain yield, the plants were re-watered uniformly after 14 days of drought period and subsequently maintained with optimum water level (− 15 kPa) until maturity. Grains were harvested and the grain yield was recorded in all the treatments. The results indicated a positive influence of cytokinin treatment on the grain yield at both tillering and grain-filling stages. The pattern of growth and morphological adjustments, as influenced by CPPU treatment, was almost similar during both tillering and grain-filling stages of rice. In terms of morphological appearance, the performance of cytokinin-treated plants, under drought stress, was slightly inferior to well-watered plants. Nevertheless, cytokinin-treated plants were morphologically adjudged to be far better than untreated plants under drought stress (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

Leaf wilting (A, B), fresh weight (C, D) and grain yield (E) of rice plants under different treatment conditions at tillering and grain filling stages. WW well-watered plants (soil moisture tension of − 15 kPa), DR drought-stressed plants (Soil moisture tension of − 55 kPa and − 72 kPa at ‘day 7’ and ‘day 14’, respectively), and DR-CPPU drought-stressed plants (–72 kPa) that sprayed with 5 mg L−1 CPPU on ‘day 6’ of drought treatment. Error bars represent SD (standard deviation). Letters viz. a, b, c, and d present over SD bars indicate the significant differences of mean at p < 0.05 (*), as analyzed by Duncan’s Multiple Range Test (DMRT)

Fig. 5.

Influence of drought and CPPU treatments on the morphology of drought sensitive rice cultivar (PTT1), on day 14 of drought stress, at tillering and grain filling stages. WW well-watered plants (soil moisture tension at − 15 kPa), DR drought-stressed plants (− 72 kPa), and DR-CPPU drought-stressed plants (− 72 kPa) that sprayed with 5 mg L−1 CPPU on ‘day 6’ of drought treatment. Scale bars, representing the length of plant, have been placed at the top of individual pictures

Conclusions

Cytokinins help the plants sustain normal growth and development by positively modulating various drought-induced morphological, physiological, and biochemical processes. Drought induces the remobilization of sugars and other essential nutrients from older leaves to young leaves to support the growth and survival of developing shoots. The process of nutrient remobilization is initiated by ethylene-induced upregulation of senescence-associated cysteine protease genes (Battelli et al. 2014; Diaz-Mendoza et al. 2016) and complemented by sugar transporters (MSTs, SUTs, and SWEETs), resulting in premature senescence of older leaves under drought stress. Elevated cytokinin concentration under drought stress relapses the drought-induced remobilization of sugars from older to younger leaves and helps in redistribution of sugar to delay the drought-induced senescence. Drought stress symptoms are morphologically characterized by leaf wilting and premature senescence, resulting in reduced fresh biomass and yield under drought stress. Cytokinin treatment lessens the leaf wilting and delays the process of senescence, thereby sustaining the fresh biomass and grain yield under drought stress. Time and again, the application of synthetic cytokinins has proved quite useful for plants in terms of growth, development, and drought tolerance ability. However, the precise regulatory mechanism of cytokinin-mediated drought tolerance is yet to be discovered.

Acknowledgements

We thank National Research Council of Thailand (Grant Number: 218383) and CIF grant, Faculty of Science, Mahidol University for financial support. The authors would like to thank Indian Council of Agricultural Research for providing a scholarship to Ranjit Singh Gujjar.

Funding

The research has been funded by National Research Council of Thailand (Grant Number: 218383, 2016–2018).

Data availability

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository with the data set identifier PXD021005.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest among the authors.

References

- Albacete A, Cantero-Navarro E, Großkinsky DK, Arias CL, Balibrea ME, Bru R, Martínez-Andújar C. Ectopic overexpression of the cell wall invertase gene CIN1 leads to dehydration avoidance in tomato. J Exp Bot. 2015;66(3):863–878. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eru448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balibrea Lara ME, Gonzalez Garcia MC, Fatima T, Ehness R, Lee TK, Proels R, Tanner W, Roitsch T. Extracellular invertase is an essential component of cytokinin-mediated delay of senescence. Plant Cell. 2004;16(5):1276–1287. doi: 10.1105/tpc.018929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battelli R, Lombardi L, Picciarelli P, Lorenzi R, Frigerio L, Rogers HJ. Expression and localisation of a senescence-associated KDEL-cysteine protease from Lilium longiflorum tepals. Plant Sci. 2014;214:38–46. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2013.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boriboonkaset T, Theerawitaya C, Yamada N, Pichakum A, Supaibulwatana K, Cha-um S, Kirdmanee C. Regulation of some carbohydrate metabolism-related genes, starch and soluble sugar contents, photosynthetic activities and yield attributes of two contrasting rice genotypes subjected to salt stress. Protoplasma. 2013;250(5):1157–1167. doi: 10.1007/s00709-013-0496-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botha AM, Kunert KJ, Cullis CA. Cysteine proteases and wheat (Triticum aestivum L) under drought: a still greatly unexplored association. Plant Cell Environ. 2017;40(9):1679–1690. doi: 10.1111/pce.12998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke EJ, Brown SJ. Evaluating uncertainties in the projection of future drought. J Hydrometeorol. 2008;9(2):292–299. doi: 10.1175/2007JHM929.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Z, Liu Y, Dong H, Teng K, Han L, Zhang X. Effects of cytokinin and nitrogen on drought tolerance of creeping bentgrass. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(4):e0154005. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0154005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen LQ, Qu XQ, Hou BH, Sosso D, Osorio S, Fernie AR, Frommer WB. Sucrose efflux mediated by SWEET proteins as a key step for phloem transport. Science. 2012;335:207–211. doi: 10.1126/science.1213351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan AK, Cairns AL, Bartels-Rahm B. Regulation of abscisic acid metabolism: towards a metabolic basis for abscisic acid-cytokinin antagonism. J Exp Bot. 1999;50(334):595–603. doi: 10.1093/jxb/50.334.595. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deng X, An B, Zhong H, Yang J, Kong W, Li Y. A novel insight into functional divergence of the MST gene family in rice based on comprehensive expression patterns. Genes. 2019;10(3):239. doi: 10.3390/genes10030239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Mendoza M, Velasco-Arroyo B, Santamaria ME, González-Melendi P, Martinez M, Diaz I. Plant senescence and proteolysis: two processes with one destiny. Genet Mol Biol. 2016;39(3):329–338. doi: 10.1590/1678-4685-GMB-2016-0015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubey RS, Singh AK. Salinity induces accumulation of soluble sugars and alters the activity of sugar metabolising enzymes in rice plants. Biol Plant. 1999;42(2):233–239. doi: 10.1023/A:1002160618700. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois M, Gilles KA, Hamilton JK, Rebers PT, Smith F. Colorimetric method for determination of sugars and related substances. Anal Chem. 1956;28(3):350–356. doi: 10.1021/ac60111a017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eom JS, Chen LQ, Sosso D, Julius BT, Lin IW, Qu XQ, Frommer WB. SWEETs, transporters for intracellular and intercellular sugar translocation. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2015;25:53–62. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2015.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan S, Amasino RM. Inhibition of leaf senescence by autoregulated production of cytokinin. Science. 1995;270(5244):1986–1988. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5244.1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gashaw A, Theerawitaya C, Samphumphuang T, Cha-um S, Supaibulwatana K. CPPU elevates photosynthetic abilities, growth performances and yield traits in salt stressed rice (Oryza sativa L. spp. indica) via free proline and sugar accumulation. Pestic Biochem Physiol. 2014;108:27–33. doi: 10.1016/j.pestbp.2013.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gujjar RS, Supaibulwatana K. The mode of cytokinin functions assisting plant adaptations to osmotic stresses. Plants. 2019;8(12):542. doi: 10.3390/plants8120542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gujjar RS, Akhtar M, Singh M. Transcription factors in abiotic stress tolerance. Indian J Plant Physiol. 2014;19(4):306–316. doi: 10.1007/s40502-014-0121-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gujjar RS, Akhtar M, Rai A, Singh M. Expression analysis of drought-induced genes in wild tomato line (Solanum habrochaites) Curr Sci. 2014;107(3):496–502. [Google Scholar]

- Gujjar RS, Banyen P, Chuekong W, Worakan P, Roytrakul S, Supaibulwatana K. A synthetic cytokinin improves photosynthesis in rice under drought stress by modulating the abundance of proteins related to stomatal conductance, chlorophyll contents, and rubisco activity. Plants. 2020;9(9):1106. doi: 10.3390/plants9091106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennion N, Durand M, Vriet C, Doidy J, Maurousset L, Lemoine R, Pourtau N. Sugars en route to the roots. Transport, metabolism and storage within plant roots and towards microorganisms of the rhizosphere. Physiol Plant. 2019;165(1):44–57. doi: 10.1111/ppl.12751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe EA, Sinha R, Schlauch D, Quackenbush J. RNA-seq analysis in MeV. Bioinformatics. 2011;27(22):3209–3210. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Hou L, Meng J, You H, Li Z, Gong Z, Shi Y. The antagonistic action of abscisic acid and cytokinin signaling mediates drought stress response in arabidopsis. Mol Plant. 2018;11(7):970–982. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2018.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeena GS, Kumar S, Shukla RK. Structure, evolution and diverse physiological roles of SWEET sugar transporters in plants. Plant Mol Biol. 2019;100:351–365. doi: 10.1007/s11103-019-00872-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson C, Samskog J, Sundström L, Wadensten H, Björkesten L, Flensburg J. Differential expression analysis of Escherichia coli proteins using a novel software for relative quantitation of LC-MS/MS data. Proteomics. 2006;6:4475–4485. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200500921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi R, Sahoo KK, Tripathi AK, Kumar R, Gupta BK, Pareek A, Singla-Pareek SL. Knockdown of an inflorescence meristem-specific cytokinin oxidase–OsCKX2 in rice reduces yield penalty under salinity stress condition. Plant Cell Environ. 2018;41(5):936–946. doi: 10.1111/pce.12947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julius BT, Leach KA, Tran TM, Mertz RA, Braun DM. Sugar transporters in plants: new insights and discoveries. Plant Cell Physiol. 2017;58(9):1442–1460. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcx090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karkacier M, Erbas M, Uslu MK, Aksu M. Comparison of different extraction and detection methods for sugars using amino-bonded phase HPLC. J Chromatogr Sci. 2003;41(6):331–333. doi: 10.1093/chromsci/41.6.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur H, Manna M, Thakur T, Gautam V, Salvi P. Imperative role of sugar signalling and transport during drought stress responses in plants. Physiol Plant. 2021 doi: 10.1111/ppl.13364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch K. Sucrose metabolism: regulatory mechanisms and pivotal roles in sugar sensing and plant development. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2004;7(3):235–246. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2004.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopečný D, Briozzo P, Popelková H, Šebela M, Končitíková R, Spíchal L, Houba-Hérin N. Phenyl-and benzylurea cytokinins as competitive inhibitors of cytokinin oxidase/dehydrogenase: a structural study. Biochimie. 2010;92(8):1052–1062. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumari S, Kumar S, Prakash P. Exogenous application of cytokinin (6-BAP) ameliorates the adverse effect of combined drought and high temperature stress in wheat seedling. J Pharma Phytochem. 2018;7(1):1176–1180. [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Jung KH, An G, Chung YY. Isolation and characterization of a rice cysteine protease gene, OsCP1, using T-DNA gene-trap system. Plant Mol Biol. 2004;54(5):755–765. doi: 10.1023/B:PLAN.0000040904.15329.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemoine R, La Camera S, Atanassova R, Dédaldéchamp F, Allario T, Pourtau N, Faucher M. Source-to-sink transport of sugar and regulation by environmental factors. Front Plant Sci. 2013;4:272. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2013.00272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Moore S, Chen C, Lindsey K. Crosstalk complexities between auxin, cytokinin, and ethylene in Arabidopsis root development: from experiments to systems modeling, and back again. Mol Plant. 2017;10(12):1480–1496. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2017.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma X, Zhang J, Burgess P, Rossi S, Huang B. Interactive effects of melatonin and cytokinin on alleviating drought-induced leaf senescence in creeping bentgrass (Agrostis stolonifera) Environ Exp Bot. 2018;145:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2017.10.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma S, Li Y, Li X, Sui X, Zhang Z. Phloem unloading strategies and mechanisms in crop fruits. J Plant Growth Regul. 2019;38(2):494–500. doi: 10.1007/s00344-018-9864-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Man D, Bao YX, Han LB, Zhang X. Drought tolerance associated with proline and hormone metabolism in two tall fescue cultivars. HortScience. 2011;46(7):1027–1032. doi: 10.21273/HORTSCI.46.7.1027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mathan J, Singh A, Ranjan A. Sucrose transport in response to drought and salt stress involves ABA-mediated induction of OsSWEET13 and OsSWEET15 in rice. Physiol Plant. 2020 doi: 10.1111/ppl.13210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misra VA, Wafula EK, Wang Y, dePamphilis CW, Timko MP. Genome-wide identification of MST, SUT and SWEET family sugar transporters in root parasitic angiosperms and analysis of their expression during host parasitism. BMC Plant Biol. 2019;19(1):196. doi: 10.1186/s12870-019-1786-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadkhani N, Heidari R. Drought-induced accumulation of soluble sugars and proline in two maize varieties. World Appl Sci J. 2008;3(3):448–453. [Google Scholar]

- Mostajeran A, Rahimi-Eichi V. Effects of drought stress on growth and yield of rice (Oryza sativa L.) cultivars and accumulation of proline and soluble sugars in sheath and blades of their different ages leaves. Agric Environ Sci. 2009;5(2):264–272. [Google Scholar]

- Nagar SH, Arora AJ, Singh VP, Ramakrishnan S, Umesh DK, Kumar SH, Saini RP. Effect of cytokinin analogues on cytokinin metabolism and stress responsive genes under osmotic stress in wheat. Bioscan. 2015;10(1):67–72. [Google Scholar]

- Nemati I, Moradi F, Gholizadeh S, Esmaeili MA, Bihamta MR. The effect of salinity stress on ions and soluble sugars distribution in leaves, leaf sheaths and roots of rice (Oryza sativa L.) seedlings. Plant Soil Environ. 2011;57(1):26–33. doi: 10.17221/71/2010-PSE. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nisler J, Kopečný D, Končitíková R, Zatloukal M, Bazgier V, Berka K, Spíchal L. Novel thidiazuron-derived inhibitors of cytokinin oxidase/dehydrogenase. Plant Mol Biol. 2016;92(1–2):235–248. doi: 10.1007/s11103-016-0509-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pak C, Van Doorn WG. Delay of Iris flower senescence by protease inhibitors. New Phytol. 2005;165(2):473–480. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2004.01226.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peleg Z, Reguera M, Tumimbang E, Walia H, Blumwald E. Cytokinin-mediated source/sink modifications improve drought tolerance and increase grain yield in rice under water-stress. Plant Biotechnol J. 2011;9(7):747–758. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2010.00584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poret M, Chandrasekar B, van der Hoorn RA, Avice JC. Characterization of senescence-associated protease activities involved in the efficient protein remobilization during leaf senescence of winter oilseed rape. Plant Sci. 2016;246:139–153. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2016.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prerostova S, Dobrev P, Gaudinova A, Knirsch V, Körber N, Pieruschka R, Humplik J. Cytokinins: their impact on molecular and growth responses to drought stress and recovery in arabidopsis. Front Plant Sci. 2018;9:655. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.00655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pungulani LL, Millner JP, Williams WM, Banda M. Improvement of leaf wilting scoring system in cowpea Vigna unguiculat (L) Walp.): from qualitative scale to quantitative index. Aust J Crop Sci. 2013;7(9):1262. [Google Scholar]

- Rasheed R, Ashraf MA, Iqbal M, Hussain I, Akbar A, Farooq U, Shad MI. Major constraints for global rice production: changing climate, abiotic and biotic stresses. In: Roychoudhury A, editor. Rice research for quality improvement: genomics and genetic engineering. Singapore: Springer; 2020. pp. 15–45. [Google Scholar]

- Reguera M, Peleg Z, Abdel-Tawab YM, Tumimbang EB, Delatorre CA, Blumwald E. Stress-induced cytokinin synthesis increases drought tolerance through the coordinated regulation of carbon and nitrogen assimilation in rice. Plant Physiol. 2013;163(4):1609–1622. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.227702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruan YL. Sucrose metabolism: gateway to diverse carbon use and sugar signaling. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2014;65:33–67. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-050213-040251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruan YL, Jin Y, Yang YJ, Li GJ, Boyer JS. Sugar input, metabolism, and signaling mediated by invertase: roles in development, yield potential, and response to drought and heat. Mol Plant. 2010;3(6):942–955. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssq044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rustgi S, Boex-Fontvieille E, Reinbothe C, von Wettstein D, Reinbothe S. The complex world of plant protease inhibitors: Insights into a Kunitz-type cysteine protease inhibitor of Arabidopsis thaliana. Commun Integr Biol. 2018;11(1):e1368599. doi: 10.1080/19420889.2017.1368599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sade N, del Mar Rubio-Wilhelmi M, Umnajkitikorn K, Blumwald E. Stress-induced senescence and plant tolerance to abiotic stress. J Exp Bot. 2018;69(4):845–853. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erx235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samea-Andabjadid S, Ghassemi-Golezani K, Nasrollahzadeh S, Najafi N. Exogenous salicylic acid and cytokinin alter sugar accumulation, antioxidants and membrane stability of faba bean. Acta Biol Hung. 2018;69(1):86–96. doi: 10.1556/018.68.2018.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen L, Wang X, Wang Z, Wu Y, Chen J. Studies on tea protein extraction using alkaline and enzyme methods. Food Chem. 2008;107(2):929–938. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.08.047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sreethong T, Prom-u-thai C, Rerkasem B, Dell B, Jamjod S. Variation of milling and grain physical quality of dry season Pathum Thani 1 in Thailand. Chiang Mai Univ J Nat Sci. 2018;17(3):191–202. [Google Scholar]

- Stein O, Granot D. An overview of sucrose synthases in plants. Front Plant Sci. 2019;10:95. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.00095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streubel J, Pesce C, Hutin M, Koebnik R, Boch J, Szurek B. Five phylogenetically close rice SWEET genes confer TAL effector-mediated susceptibility to Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae. New Phytol. 2013;200(3):808–819. doi: 10.1111/nph.12411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Reinders A, LaFleur KR, Mori T, Ward JM. Transport activity of rice sucrose transporters OsSUT1 and OsSUT5. Plant Cell Physiol. 2010;51(1):114–122. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcp172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorsell A, Portelius E, Blennow K, Westman-Brinkmalm A. Evaluation of sample fractionation using micro-scale liquid-phase isoelectric focusing on mass spectrometric identification and quantitation of proteins in a SILAC experiment. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2007;21:771–778. doi: 10.1002/rcm.2898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan H, Wu L, Yang Y, Zhou G, Ruan YL. Evolution of sucrose metabolism: the dichotomy of invertases and beyond. Trends Plant Sci. 2018;23(2):163–177. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2017.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan L, Ren W, Miao H, Zhang J, Fang J. Genome-wide identification, expression, and association analysis of the monosaccharide transporter (MST) gene family in peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) 3 Biotech. 2020;10(3):1–16. doi: 10.1007/s13205-020-2123-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Hao Q, Wang W, Li Q, Chen F, Ni F, Wang W. The involvement of cytokinin and nitrogen metabolism in delayed flag leaf senescence in a wheat stay-green mutant, tasg1. Plant Sci. 2019;278:70–79. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2018.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Lei H, Xu C, Chen G. Long-term drought resistance in rice (Oryza sativa L.) during leaf senescence: a photosynthetic view. Plant Growth Regul. 2019;88(3):253–266. doi: 10.1007/s10725-019-00505-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williams LE, Lemoine R, Sauer N. Sugar transporters in higher plants–a diversity of roles and complex regulation. Trends Plant Sci. 2000;5(7):283–290. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(00)01681-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worakan P, Karaket N, Maneejantra N, Supaibulwatana K. A phenylurea cytokinin, CPPU, elevated reducing sugar and correlated to andrographolide contents in leaves of Andrographis paniculata (Burm. F.) wall. Ex Nees. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2017;181(2):638–649. doi: 10.1007/s12010-016-2238-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao XO, Zeng YM, Cao BH, Lei JJ, Chen QH, Meng CM, Cheng YJ. PSAG12-IPT overexpression in eggplant delays leaf senescence and induces abiotic stress tolerance. J Hortic Sci Biotechnol. 2017;92(4):349–357. [Google Scholar]

- Xu Q, Chen S, Yunjuan R, Chen S, Liesche J. Regulation of sucrose transporters and phloem loading in response to environmental cues. Plant Physiol. 2018;176(1):930–945. doi: 10.1104/pp.17.01088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Shinozaki K. Transcriptional regulatory networks in cellular responses and tolerance to dehydration and cold stresses. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2006;57:781–803. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang D, Li Y, Shi Y, Cui Z, Luo Y, Zheng M, Wang Z. Exogenous cytokinins increase grain yield of winter wheat cultivars by improving stay-green characteristics under heat stress. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(5):e0155437. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0155437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Luo D, Yang B, Frommer WB, Eom JS. SWEET 11 and 15 as key players in seed filling in rice. New Phytol. 2018;218(2):604–615. doi: 10.1111/nph.15004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao D, Gonzales-Vigil E, Mansfield SD. Arabidopsis sucrose synthase localization indicates a primary role in sucrose translocation in phloem. J Exp Bot. 2020;71(6):1858–1869. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erz539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yooyongwech S, Cha-um S, Supaibulwatana K. Water relation and aquaporin genes (PIP1; 2 and PIP2; 1) expression at the reproductive stage of rice (Oryza sativa L. spp. indica) mutant subjected to water deficit stress. Plant Omics. 2013;6(1):79. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida S, Forno DA, Cock JH. Laboratory manual for physiological studies of rice. Philippines: Los Banos; 1971. p. 61. [Google Scholar]

- Zahir ZA, Asghar HN, Arshad M. Cytokinin and its precursors for improving growth and yield of rice. Soil Biol Biochem. 2001;33(3):405–408. doi: 10.1016/S0038-0717(00)00145-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P, Wang WQ, Zhang GL, Kaminek M, Dobrev P, Xu J, Gruissem W. Senescence-inducible expression of isopentenyl transferase extends leaf life, increases drought stress resistance and alters cytokinin metabolism in cassava. J Integr Plant Biol. 2010;52(7):653–669. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2010.00956.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Liu L, Huang W, Yuan M, Zhou F, Li X, Lin Y. Overexpression of OsSWEET5 in rice causes growth retardation and precocious senescence. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(4):e94210. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository with the data set identifier PXD021005.