Abstract

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) can enter the central nervous system and cause several neurological manifestations. Data from cerebrospinal fluid analyses and postmortem samples have been shown that SARS-CoV-2 has neuroinvasive properties. Therefore, ongoing studies have focused on mechanisms involved in neurotropism and neural injuries of SARS-CoV-2. The inflammasome is a part of the innate immune system that is responsible for the secretion and activation of several pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-1β, interleukin-6, and interleukin-18. Since cytokine storm has been known as a major mechanism followed by SARS-CoV-2, inflammasome may trigger an inflammatory form of lytic programmed cell death (pyroptosis) following SARS-CoV-2 infection and contribute to associated neurological complications. We reviewed and discussed the possible role of inflammasome and its consequence pyroptosis following coronavirus infections as potential mechanisms of neurotropism by SARS-CoV-2. Further studies, particularly postmortem analysis of brain samples obtained from COVID-19 patients, can shed light on the possible role of the inflammasome in neurotropism of SARS-CoV-2.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, Inflammasome, Pyroptosis, Neurotropism, Pro-inflammatory cytokines

Introduction

Neurological manifestations have been reported in patients infected with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The neuroinvasive susceptibility of coronaviruses has been depicted in humans in previous epidemics (Hung et al., 2003; Sepehrinezhad et al., 2020). Recently, the brain autopsy findings in a patient with SARS-CoV-2 have suggested that this virus may gain access to the CNS by infecting endothelial cells via transcytosis to neural tissue (Paniz-Mondolfi et al., 2020). Furthermore, the post-mortem findings in patients who died from COVID-19 have revealed the presence of SARS-CoV-2 in the cortical neurons associated with minimal immune cell infiltrates in brain tissues (Song et al., 2020a). Recently, we demonstrated the presence of SARS-CoV-2 in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of patients with COVID-19 infection, who suffering from severe neurological manifestations. Despite several reports of neurological manifestations and neuroinvasiveness of SARS-CoV-2 during infection (Guan et al., 2020; Sepehrinezhad et al., 2020; Mao et al., 2020; Paniz-Mondolfi et al., 2020; Song et al., 2020b), the determination of mechanisms underlying SARS-CoV-2-mediated neurological manifestation and brain injury are warranted. Among different mechanisms described for SARS-CoV-2, cytokine storm (i.e., releasing of the pro-inflammatory cytokines) has been suggested as the major life-threatening complication (Zhao et al., 2021). Growing evidence has revealed that the inflammasome is activated by CoVs infections. Increasing levels of inflammasome-induced pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-1beta (IL-1β) and interleukin 6 (IL-6), have been reported in MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV cases (He et al., 2006; Lau et al., 2013). In SARS-CoV-2, alveolar macrophages have been speculated as the main source of inflammation (Channappanavar et al., 2016). Immunofluorescence observations of samples from patients who died from SARS-CoV-2 infection indicated that the inflammasome pathway plays an important role in the pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 (Toldo et al., 2021). Recently, it has been shown that cell death of monocytes derived from COVID-19 patients was caused by the production of IL-1B, expression of caspase-1, and cleavage of gasdermin D as the main components of the inflammasome (Ferreira et al., 2021). Furthermore, interleukin 18 (IL-18) as other inflammasome-induced cytokines was increased in COVID-19 patients (Satış et al., 2021). In the same way, inhibition of IL-1B displayed efficient effects on oxygenation in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia (Landi et al., 2020). These findings suggest the involvement of inflammasomes in the pathophysiology of CoVs infections. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to review neurotropism mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 and discuss the probable mechanisms of the inflammasome in COVID-19 patients with neurological manifestations.

A brief overview of inflammasome and pyroptosis

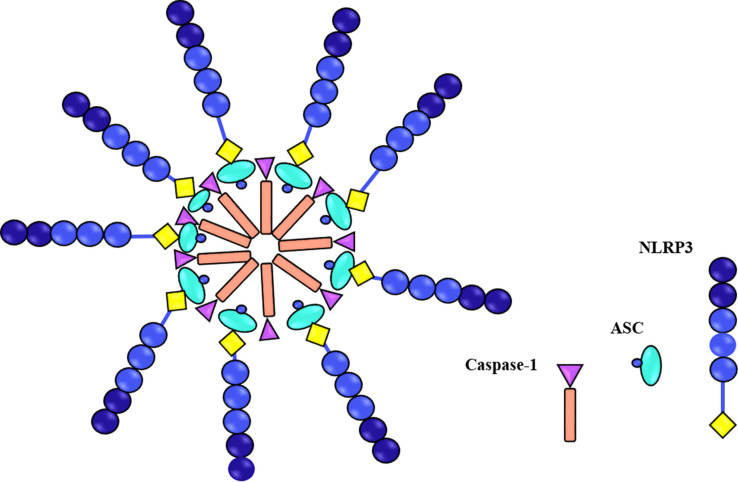

The three genetically described cell death pathways that have been extensively explored during the last decades are apoptosis, necroptosis, and pyroptosis. The first programmed cell death is apoptosis known as immunologically silent, which usually causes cell death through caspase-3/7-dependent manner. On the other hand, lytic cell death is caused by necroptosis and pyroptosis via the release of immunostimulatory substances. Pyroptosis in the canonical model is induced by activation of intracellular multiprotein signalling complexes known as the inflammasomes. Inflammasomes are cytosolic molecular complexes of the innate immune system that are activated in response to cellular infections and other stressors. Activation of caspase-1 and maturation of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-18 as consequences of inflammasome assembly, can restrict the intracellular pathogen replication through induction of programmed cell death (Bergsbaken et al., 2009). Inflammasome activity usually is triggered by various sensor proteins, such as nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor (NOD-like receptor; NLR) or AIM-2-like receptor (ALR). Inflammasomes are named according to their sensor proteins, such as NLRP1, NLRP2, NLRP3, NLRP6, NLRP12, NLRC4, and AIM2 (Ting et al., 2008; Lugrin and Martinon, 2018). The adaptor protein apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a caspase-recruitment domain (ASC) is associated with pro-inflammatory caspase-1 (Stehlik et al., 2003) and form the whole structure of the inflammasome complex (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of NLRP3 inflammasome components. Three components of inflammasome are NLRP3 proteins, ASC, and caspase-1

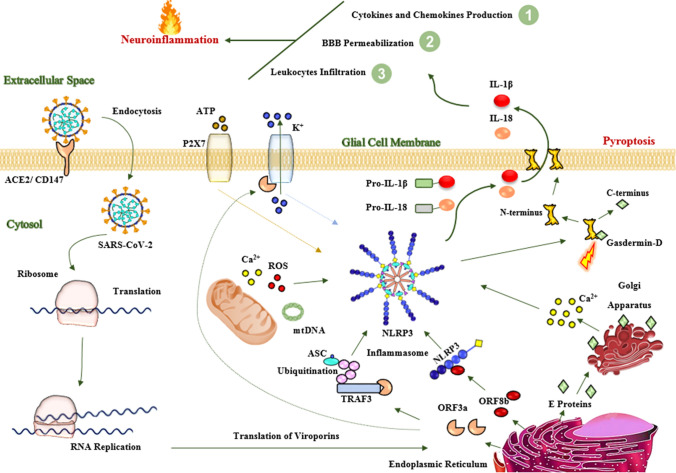

Among different types of sensor proteins, NLRP3 is an important inflammasome, because it can restrict intracellular pathogen replication. The NLRP3 inflammasome is expressed by several myeloid cells, especially macrophages. The NLRP3 is activated by several stimuli including pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), and viral pathogens (He et al., 2010; Toma et al., 2010; Thomas et al., 2009; Mariathasan et al., 2006). The NLRP3 inflammasome response can be classified into activation and maintenance processes. The activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome is usually induced by ligands (i.e., PAMPs or DAMPs). These ligands bind to a pattern recognition receptor (PRR), mainly toll-like receptor-4 (TLR-4), and activate the nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) pathway. NF-κB increases the expression of NLRP3 protein and its proinflammatory cytokines (e.g., Pro-IL-1B and Pro-IL-18) (Bauernfeind et al., 2009). On one hand, the release of the lysosomal components, potassium efflux, and mitochondrial dysfunctions play important roles in the maintenance phase of NLRP3 inflammasome. In this step, the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), the increase of calcium concentration, and the release of mitochondrial DNA into the cytosol maintain the inflammasome complex (Guo et al., 2015). Followed by the activated inflammasome, caspase-1 is activated and cleavages the N-terminal domain of gasdermin-D. These changes lead to a pore in the plasma membrane called pyroptosis (Chen et al., 2016). Furthermore, activated inflammasome converts the Pro-IL-1B and Pro-IL-18 to mature forms and releases them into the extracellular space (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Mechanisms of inflammasome assembly and pyroptosis. The inflammasome is activated by two consecutive signals. First, PAPM or DAMP initiates some pathways through PRR, mainly TLR4 that leads to an increase in the expression of NF-kβ in the nucleus. The NF-kβ triggers the production of Pro-IL-1β and Pro-IL18. The second signal is initiated by potassium efflux, lysosomal rupture, and P2X7 receptors and mitochondrial dysfunctions due to depletion of calcium reserves as well as the release of Mitochondrial DNA (MtDNA) and ROS into the cytosol. These changes create inflammasome components (i.e., NLRP3, ASC, and activated caspase-1). Activated caspase-1 cleavages the linker region of gasdermin-D and forms a pore in the cellular membrane. In addition, caspase-1 changes Pro-IL-1β and Pro-IL18 into the activated forms. Finally, these proinflammatory cytokines released into the extracellular by pores called pyroptosis. Abbreviations: ASC adaptor protein apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a caspase-recruitment domain; DAMP damage-associated molecular pattern; IL-1β interleukin 1beta; IL-18 interleukin18; mt DNA mitochondrial DNA; NF-kβ nuclear factor-kappa B; NLRP3 nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor family pyrin domain containing 3; P2X7 purinergic type 2 ATP receptor family; PAMP pathogen-associated molecular pattern; PRR pattern recognition receptor; ROS reactive oxygen species; TLR4 toll-like receptor 4

Activation of inflammasome and coronavirus infections

The inflammasome is activated by CoVs infections and releases pro-inflammatory cytokines. Raising the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines is the main reason for the progression of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and death followed by CoVs infections (Badraoui et al., 2020; Petrosillo et al., 2020). Increasing levels of inflammasome-induced pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β and IL-6, have been reported in MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV cases (He et al., 2006; Lau et al., 2013). In the case of SARS-CoV-2, the source of inflammation is macrophages that are activated by PAMPs/DAMPs-derived infected pneumocytes (Channappanavar et al., 2016). The expression of NLRP3 inflammasome and caspase-1 were significantly increased in COVID-19 patients (Toldo et al., 2021). Viroporins are hydrophobic multifunctional proteins that play vital roles in inflammasome activation. Viroporins are encoded by viral RNA and contribute to both virus entry to the host cells and virus release from infected cells (Nieva et al., 2012). These viroporins can form oligomeric ion channels or pores across the cell membrane. The SARS-CoV can encode several viroporins, such as the envelope (E) protein and open reading frame 3a (e.g., ORF3a, ORF8a, and ORF8b) (Nieto-Torres et al., 2014). The E protein activates the NF-kB pathway (DeDiego et al., 2014) and increases the release of calcium from the Golgi apparatus (Nieto-Torres et al., 2015). On the other hand, ORF3a modifies ASC through a tumor necrosis factor receptor‐associated factor 3 (TRAF3)-dependent mechanism (Siu et al., 2019), while ORF8b interacts with the NLRP3 protein (Shi et al., 2019). Finally, by combining these interactions, NLRP3 inflammasome is activated and pyroptosis is formed by cleavage of the gasdermin-D at the linker section between the amino-terminal and carboxyl tail (Fig. 3). During pyroptosis, sodium and water can enter the infected cells and cause cell swelling. The ORF3a accelerates the inflammasome assembly by increasing the potassium efflux and releasing ROS generation (Xu et al., 2020). Most important, as it has been shown in recent studies, SARS-CoV-2 has several similarities in terms of phylogenetically, structurally, and pathogenicity with SARS-CoV. For instance, genomic sequence analysis tools indicated that SARS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2, and MERS belong to the cluster of beta coronaviruses (Chen et al., 2020; Cui et al., 2019). SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 use ACE2 receptors to enter the host cells (Wan et al., 2020). Furthermore, both of them present very similar symptoms and clinical manifestations in infected people (Gerges Harb et al., 2020; Hu et al., 2020). Therefore, inflammasome-dependent pathogenicity may be seen in SARS-CoV-2.

Fig. 3.

Proposed mechanisms of neuronal injury by SARS-CoV-2. In the CNS, SARS-CoV-2 enters into the glial cells, in particular microglia, through an endocytosis-dependent manner via interaction of spike proteins with ACE2 receptor. After internalization, viral RNA replicates and viral structural proteins, as well as viroporins, such as E protein, ORF3a, and ORF8b, are translated. The E proteins cause the release of calcium from the Golgi apparatus. The ORF8b interacts with NLRP3 protein. The ORF3a interacts with TRAF3 ubiquitinates ASC protein as well as increases the efflux of potassium from the cell membrane. These events along with mitochondrial dysfunctions, potassium efflux, and activated P2X7 receptors lead to activation of NLRP3 inflammasome and consequently activated caspase-1-induced pyroptosis in the glial cells. Activated proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β and IL-18, trigger the production of other proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNFα, IFNβ, IL-6, and CCL2 into the CNS. IL-1β and IL-18 and other produced proinflammatory cytokines increase the permeability of the BBB and consequently enhance the infiltration of peripheral immune cells into the CNS. All these pathological processes cause severe neuroinflammation. Neuroinflammation is responsible for neuronal injury and subsequently neurological manifestations in SARS-CoV-2 infection. Abbreviations: ACE2 angiotensin-converting enzyme 2; ASC adaptor protein apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a caspase-recruitment domain; CD147 cluster of differentiation 147; E protein envelope protein; IL-1β interleukin 1beta; IL-18 interleukin18; mt DNA mitochondrial DNA; NLRP3 nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor family pyrin domain containing 3; ORF3a open reading frame 3a; P2X7 purinergic type 2 ATP receptor family; ROS reactive oxygen species; TRAF3 tumor necrosis factor receptor‐associated factor 3

Inflammasome may mediate SARS-CoV-2-induced neurotropism

The activation of NLRP3 and its role in the pathophysiology of several neurological disorders, such as Alzheimer’s disease (Halle et al., 2008; Scott et al., 2020), Parkinson’s disease (Wang et al., 2016; Zhou et al., 2016), multiple sclerosis (Jahanbazi Jahan-Abad et al., 2019; Malhotra et al., 2020), and traumatic brain injury (O’Brien, 2020) have been described. Neuroinflammation is a distinguished inflammatory process in response to virus infections (i.e., neuroinvasion). It seems that SARS-CoV-2 can target and infect the BBB endothelial cells, neurons, microglia, and astrocytes (Ribeiro et al., 2021) via ACE2 and cluster of differentiation 147 (CD147) receptors (Ribeiro et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2021). Microglia and astrocytes are two major sources of proinflammatory cytokines and consequently neuroinflammation (Kwon and Koh, 2020). Microglia have phagocytosis activity against infiltrating pathogens and remove neurotoxic agents. SARS-CoV-2 can directly infect brain astrocytes neurons in COVID-19 patients (Crunfli et al., 2020). Another postmortem analysis indicated reactive astrogliosis and microglial activation in the medulla oblongata and cerebellum as well as lymphocyte infiltration in the perivascular and parenchymal area in patients who died from COVID-19 (Matschke et al., 2020). Therefore, following SARS-CoV-2 infections, microglia and astrocytes are two main targeted cells by the virus.

As studies revealed, SARS-CoV-2 can activate NLRP3 inflammasome (Xu et al., 2020; Ferreira et al., 2021; Sepehrinezhad et al., 2020; Rezaeitalab et al., 2021). Exposure of BV-2 microglia to SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein S1 increased the production of NLRP3 protein, IL-1β, IL-6, tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα), and nitric oxide. Interestingly, SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein S1 increased the activity of NF-κB and caspase-1 in BV-2 microglial cell line (Olajide et al., 2020). Furthermore, SARS-CoV-2 spike protein triggered the production of interferon-beta (IFN-β), NF-κB, and TNFα in human microglia (Mishra and Banerjea, 2021). Infected of both microglia and astrocyte cultures with murine coronavirus MHV-A59 increased expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines in supernatants (Lavi and Cong, 2020). In addition, infecting mouse microglia and astrocytes with murine coronavirus MHV increased the expression of TNFα and IL-6 (Yu and Zhang, 2006). Moreover, SARS-CoV-2 can infect human astrocytes through ACE2 and activates caspase-1 in the structure of NLRP3 inflammasome and consequently induces pyroptosis and releases of IL-1β and IL-18 into the extracellular space. Caspase-1 causes BBB disruption and initiates neuroinflammation (Israelov et al., 2020; Venero et al., 2013; Mamik et al., 2017). In this context, IL-1β and IL-18 progress neuroinflammation and produce other proinflammatory cytokines by neuronal cells, microglia, and astrocytes (Hauptmann et al., 2020; Hewett et al., 2012; Davis et al., 2018; Arend et al., 2008). IL-1β has also a major role in permeabilization of BBB and activation of astrocytes and microglia and consequently infiltration of peripheral immune cells into the CNS (Wang et al., 2014). Activation of microglia and astrocytes can induce further production of cytokines and chemokines, such as TNFα, IL-6, chemokine (C–C motif) ligand 2 (CCL2), and C–X–C motif chemokine ligand 10 (CXCL10) (Thelin et al., 2018; Riazi et al., 2008; Ferrari et al., 2004). IL-18 can also activate microglia and increase the activity of caspase-1 and the production of proinflammatory cytokines into the CNS (Felderhoff-Mueser et al., 2005; Gong et al., 2020). On the other hand, SARS-CoV-2 viroporins and the P2X7 receptors (P2X7R) can trigger inflammasome assembly and induce pyroptosis in the infected glial cells (Campagno and Mitchell, 2021; Ribeiro et al., 2021). As a result, inflammasome assembly forms pores in the cell membrane that causes sudden depletion of proinflammatory cytokines from infected glia into the extracellular matrix. Finally, all these pathological processes exacerbate neuroinflammation-induced neuronal injury (Kempuraj et al., 2016) and present neurological manifestations following SARS-CoV-2 infection (Fig. 3).

Final Remarks

In this review, we suggested that inflammasome with its downstream signals can be targeted as a main pathology of SARS-CoV-2 in neurological cases. Knowledge of early signs of possible mechanisms after neurological manifestations in the course of SARS-CoV-2 is needed to be able to timely intervene with a suitable treatment. Some possible drugs are available that are previously investigated in clinical practice (Table 1). Considerably more work will need to be done to determine the effects of these drugs on inflammasome in COVID-19 patients with neurological manifestations. In the same way, post mortem analysis is needed to clarify the exact mechanisms of inflammasome and pyroptosis in the CNS with COVID-19 infections.

Table 1.

Some suggested drugs with targeting inflammasome may be used for the treatment of SARS-CoV-2-induced neurological manifestations

| Mechanism | Drug or agents | Mentioned in COVID-19 studies |

|---|---|---|

| Anti-IL-1β therapy | Anakinra | (Mariette et al., 2021; Kooistra et al., 2020; Pasin et al., 2021; Franzetti et al., 2021) |

| Canakinumab | (Landi et al., 2020; Katia et al., 2021; Generali et al., 2021) | |

| NLRP3 inhibitors | Glibenclamide | – |

| MCC950 | (Rodrigues et al., 2021) | |

| CY-09 | – | |

| OLT117 | – | |

| benzoxathiole derivative BOT-4-one | – | |

| β-hydroxybutyrate | – | |

| INF4E | – | |

| 3,4-methylenedioxy-β-nitrostyrene | – | |

| Artemisinin | (Li et al., 2021a; Uckun et al., 2021; Gendrot et al., 2020) | |

| Probenecid | (Swayne et al., 2020) | |

| Mefenamic acid | (Pareek 2020; Shah et al., 2021) | |

| Parthenolide | (Bahrami et al., 2020; Nemati and Rami, 2020) | |

| Oridonin | – | |

| Bay 11–7082 | (Olajide et al., 2021) | |

| microRNA-7: inhibited microglial NLRP3 inflammasome | – | |

| Anti-inflammatory drugs | Tocilizumab and other IL-6 antibodies | (Ulhaq and Soraya, 2020; Aziz et al., 2021; Salama et al., 2021; Horby et al., 2021) |

| Emapalumab: anti-IFN-γ antibody | (Magro, 2020) | |

| Polaprezinc | (Sepehrinezhad et al., 2021) | |

| Colchicine | (Madrid-García et al., 2021; Reyes et al., 2021) | |

| Glucocorticoids | (Mishra and Mulani, 2021; Annane, 2021; Robinson and Morand, 2021) | |

| P2X7R antagonist | Brilliant blue G | – |

| Anti-IL-18 therapy | Anti-IL-1R7 antibody: block the activity of IL-18 | (Li et al., 2021b) |

| Anti-caspase-1 therapy | Pralnacasan | – |

| Belnacasan | – |

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ACE2

Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2

- ALR

AIM-2-like receptor

- ARDS

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- ASC

Adaptor protein apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a caspase-recruitment domain

- BBB

Blood–brain barrier

- CCL2

Chemokine (C–C motif) ligand 2

- CD147

Cluster of differentiation 147

- CNS

Central nervous system

- CoVs

Coronaviruses

- COVID-19

Coronavirus disease 2019

- CXCL10

CXC motif chemokine ligand 10

- DAMP

Damage-associated molecular pattern

- DPP4

Dipeptidyl-peptidase 4

- E protein

Envelope protein

- GFAP

Glial fibrillary acidic protein

- IFNβ

Interferon beta

- IL-1β

Interleukin 1beta

- IL-6

Interleukin 6

- IL-18

Interleukin18

- MERS-CoV

Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus

- mt DNA

Mitochondrial DNA

- NF-kβ

Nuclear factor kappa B

- NfL

Neurofilament light chain protein

- NLR

Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor

- NLRP3

Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor family pyrin domain containing 3

- ORF3a

Open reading frame 3a

- P2X7

Purinergic type 2 ATP receptor family

- PAMP

Pathogen-associated molecular pattern

- PRR

Pattern recognition receptor

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- SARS-CoV-2

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

- TLR4

Toll-like receptor 4

- TNFα

Tumor necrosis factor-alpha

- TRAF3

Tumor necrosis factor receptor‐associated factor 3

Author’s contributions

Ali Sepehrinezhad and Sajad Sahab Negah designed the study, performed the literature review and drafted the manuscript. In addition, Ali Gorji and Sajad Sahab Negah critically edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Funding information is not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Annane D. Corticosteroids for COVID-19. J Intensive Med. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.jointm.2021.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arend WP, Palmer G, Gabay C. IL-1, IL-18, and IL-33 families of cytokines. Immunol Rev. 2008;223:20–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00624.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aziz M, Haghbin H, Abu Sitta E, Nawras Y, Fatima R, Sharma S, Lee-Smith W, Duggan J, Kammeyer JA, Hanrahan J, Assaly R. Efficacy of tocilizumab in COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Virol. 2021;93(3):1620–1630. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badraoui R, Alrashedi MM, El-May MV, Bardakci F. (2020) Acute respiratory distress syndrome: a life threatening associated complication of SARS-CoV-2 infection inducing COVID-19. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2020 doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1803139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahrami M, Kamalinejad M, Latifi SA, Seif F, Dadmehr M. Cytokine storm in COVID-19 and parthenolide: preclinical evidence. Phytother Res. 2020;34(10):2429–2430. doi: 10.1002/ptr.6776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauernfeind FG, Horvath G, Stutz A, Alnemri ES, Macdonald K, Speert D, Fernandes-Alnemri T, Wu J, Monks BG, Fitzgerald KA, Hornung V, Latz E. Cutting edge: NF-kappaB activating pattern recognition and cytokine receptors license NLRP3 inflammasome activation by regulating NLRP3 expression. J Immunol. 2009;183(2):787–791. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergsbaken T, Fink SL, Cookson BT. Pyroptosis: host cell death and inflammation. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7(2):99–109. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campagno KE, Mitchell CH. The P2X7 receptor in microglial cells modulates the endolysosomal axis, autophagy, and phagocytosis. Front Cell Neurosci. 2021 doi: 10.3389/fncel.2021.645244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Channappanavar R, Fehr AR, Vijay R, Mack M, Zhao J, Meyerholz DK, Perlman S. Dysregulated type I interferon and inflammatory monocyte-macrophage responses cause lethal pneumonia in SARS-CoV-infected mice. Cell Host Microbe. 2016;19(2):181–193. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, He WT, Hu L, Li J, Fang Y, Wang X, Xu X, Wang Z, Huang K, Han J. Pyroptosis is driven by non-selective gasdermin-D pore and its morphology is different from MLKL channel-mediated necroptosis. Cell Res. 2016;26(9):1007–1020. doi: 10.1038/cr.2016.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Liu Q, Guo D. Emerging coronaviruses: Genome structure, replication, and pathogenesis. J Med Virol. 2020;92(4):418–423. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R, Wang K, Yu J, Howard D, French L, Chen Z, Wen C, Xu Z. The spatial and cell-type distribution of SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2 in the human and mouse brains. Front Neurol. 2021 doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.573095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crunfli, F., Carregari, V. C., Veras, F. P., Vendramini, P. H., Fragnani Valença, A. G., Leão Marcelo Antunes, A. S., Brandão-Teles, C., Da Silva Zuccoli, G., Reis-De-Oliveira, G., C.Silva-Costa, L., Saia-Cereda, V. M., Codo, A. C., Parise, P. L., Toledo-Teixeira, D. A., De Souza, G. F., Muraro, S. P., Silva Melo, B. M., Almeida, G. M., Silva Firmino, E. M., Paiva, I. M., Souza Silva, B. M., Ludwig, R. G., Ruiz, G. P., Knittel, T. L., Gastão Davanzo, G., Gerhardt, J. A., Rodrigues, P. B., Forato, J., Amorim, M. R., Silva, N. B., Martini, M. C., Benatti, M. N., Batah, S., Siyuan, L., João, R. B., Silva, L. S., Nogueira, M. H., Aventurato, Í. K., De Brito, M. R., Machado Alvim, M. K., Da Silva Júnior, J. R., Damião, L. L., De Paula Castilho Stefano, M. E., Pereira De Sousa, I. M., Da Rocha, E. D., Gonçalves, S. M., Lopes Da Silva, L. H., Bettini, V., De Campos, B. M., Ludwig, G., Mendes Viana, R. M., Martins, R., Vieira, A. S., Alves-Filho, J. C., Arruda, E., Sebollela, A. S., Cendes, F., Cunha, F. Q., Damásio, A., Ramirez Vinolo, M. A., Munhoz, C. D., Rehen, S. K., Mauad, T., Duarte-Neto, A. N., Ferraz Da Silva, L. F., Dolhnikoff, M., Saldiva, P., Fabro, A. T., Farias, A. S., Moraes-Vieira, P. M. M., Proença Módena, J. L., Yasuda, C. L., Mori, M. A., Cunha, T. M. & Martins-De-Souza, D. (2020) SARS-CoV-2 infects brain astrocytes of COVID-19 patients and impairs neuronal viability. medRxiv. 10.09.20207464.

- Cui J, Li F, Shi Z-L. Origin and evolution of pathogenic coronaviruses. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2019;17(3):181–192. doi: 10.1038/s41579-018-0118-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis RL, Buck DJ, Mccracken K, Cox GW, Das S. Interleukin-1β-induced inflammatory signaling in C20 human microglial cells. Neuroimmunol Neuroinflam. 2018;5:50. [Google Scholar]

- Dediego ML, Nieto-Torres JL, Regla-Nava JA, Jimenez-Guardeño JM, Fernandez-Delgado R, Fett C, Castaño-Rodriguez C, Perlman S, Enjuanes L. Inhibition of NF-κB-mediated inflammation in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-infected mice increases survival. J Virol. 2014;88(2):913–924. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02576-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariette X, Hermine O, Resche-Rigon M, Porcher R, Ravaud P, Bureau S, Dougados M, Tibi A, Azoulay E, Cadranel J, Emmerich J, Fartoukh M, Guidet B, Humbert M, Lacombe K, Mahevas M, Pene F, Pourchet-Martinez V, Schlemmer F, Yazdanpanah Y, Baron G, Perrodeau E, Vanhoye D, Kedzia C, Demerville L, Gysembergh-Houal A, Bourgoin A, Dalibey S, Raked N, Mameri L, Alary S, Hamiria S, Bariz T, Semri H, Hai DM, Benafla M, Belloul M, Vauboin P, Flamand S, Pacheco C, Walter-Petrich A, Stan E, Benarab S, Nyanou C, Montlahuc C, Biard L, Charreteur R, Dupré C, Cardet K, Lehmann B, Baghli K, Madelaine C, D'Ortenzio E, Puéchal O, Semaille C, Savale L, Harrois A, Figueiredo S, Duranteau J, Anguel N, Monnet X, Richard C, Teboul JL, Durand P, Tissieres P, Jevnikar M, Montani D, Bulifon S, Jaïs X, Sitbon O, Pavy S, Noel N, Lambotte O, Escaut L, Jauréguiberry S, Baudry E, Verny C, Noaillon M, Lefèvre E, Zaidan M, Le Tiec CLT, Verstuyft CV, Roques AM, Grimaldi L, Molinari D, Leprun G, Fourreau A, Cylly L, Virlouvet M, Meftali R, Fabre S, Licois M, Mamoune A, Boudali Y, Georgin-Lavialle S, Senet P, Soria A, Parrot A, François H, Rozensztajn N. Effect of anakinra versus usual care in adults in hospital with COVID-19 and mild-to-moderate pneumonia (CORIMUNO-ANA-1): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2021 doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30556-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felderhoff-Mueser U, Schmidt OI, Oberholzer A, Bührer C, Stahel PF. IL-18: a key player in neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration? Trends Neurosci. 2005;28(9):487–493. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari CC, Depino AM, Prada F, Muraro N, Campbell S, Podhajcer O, Perry VH, Anthony DC, Pitossi FJ. Reversible demyelination, blood-brain barrier breakdown, and pronounced neutrophil recruitment induced by chronic IL-1 expression in the brain. Am J Pathol. 2004;165(5):1827–1837. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63438-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira AC, Soares VC, De Azevedo-Quintanilha IG, Dias SDSG, Fintelman-Rodrigues N, Sacramento CQ, Mattos M, De Freitas CS, Temerozo JR, Teixeira L, Damaceno Hottz E, Barreto EA, Pão CRR, Palhinha L, Miranda M, Bou-Habib DC, Bozza FA, Bozza PT, Souza TML. SARS-CoV-2 engages inflammasome and pyroptosis in human primary monocytes. Cell Death Discov. 2021;7(1):43. doi: 10.1038/s41420-021-00428-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzetti M, Forastieri A, Borsa N, Pandolfo A, Molteni C, Borghesi L, Pontiggia S, Evasi G, Guiotto L, Erba M, Pozzetti U, Ronchetti A, Valsecchi L, Castaldo G, Longoni E, Colombo D, Soncini M, Crespi S, Maggiolini S, Guzzon D, Piconi S. IL-1 Receptor Antagonist Anakinra in the Treatment of COVID-19 Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome: A Retrospective. Obs Study J Immunol. 2021;206(7):1569–1575. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.2001126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gendrot M, Duflot I, Boxberger M, Delandre O, Jardot P, Le Bideau M, Andreani J, Fonta I, Mosnier J, Rolland C. Antimalarial artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACT) and COVID-19 in Africa: In vitro inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 replication by mefloquine-artesunate. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;99:437–440. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.08.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Generali D, Bosio G, Malberti F, Cuzzoli A, Testa S, Romanini L, Fioravanti A, Morandini A, Pianta L, Giannotti G, Viola EM, Giorgi-Pierfranceschi M, Foramitti M, Tira RA, Zangrandi I, Chiodelli G, Machiavelli A, Cappelletti MR, Giossi A, De Giuli V, Costanzi C, Campana C, Bernocchi O, Sirico M, Zoncada A, Molteni A, Venturini S, Giudici F, Scaltriti M, Pan A. Canakinumab as treatment for COVID-19-related pneumonia: A prospective case-control study. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;104:433–440. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.12.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerges Harb, J., Noureldine, H. A., Chedid, G., Eldine, M. N., Abdallah, D. A., Chedid, N. F. & Nour-Eldine, W. (2020) SARS, MERS and COVID-19: clinical manifestations and organ-system complications: a mini review. Pathogens and Disease 78(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Gong Q, Lin Y, Lu Z, Xiao Z. Microglia-astrocyte cross talk through IL-18/IL-18R signaling modulates migraine-like behavior in experimental models of migraine. Neuroscience. 2020;451:207–215. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2020.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan W-J, Ni Z-Y, Hu Y, Liang W-H, Ou C-Q, He J-X, Liu L, Shan H, Lei C-L, Hui DSC, Du B, Li L-J, Zeng G, Yuen K-Y, Chen R-C, Tang C-L, Wang T, Chen P-Y, Xiang J, Li S-Y, Wang J-L, Liang Z-J, Peng Y-X, Wei L, Liu Y, Hu Y-H, Peng P, Wang J-M, Liu J-Y, Chen Z, Li G, Zheng Z-J, Qiu S-Q, Luo J, Ye C-J, Zhu S-Y, Zhong N-S. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo H, Callaway JB, Ting JPY. Inflammasomes: mechanism of action, role in disease, and therapeutics. Nat Med. 2015;21(7):677–687. doi: 10.1038/nm.3893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halle A, Hornung V, Petzold GC, Stewart CR, Monks BG, Reinheckel T, Fitzgerald KA, Latz E, Moore KJ, Golenbock DT. The NALP3 inflammasome is involved in the innate immune response to amyloid-beta. Nat Immunol. 2008;9(8):857–865. doi: 10.1038/ni.1636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauptmann J, Johann L, Marini F, Kitic M, Colombo E, Mufazalov IA, Krueger M, Karram K, Moos S, Wanke F, Kurschus FC, Klein M, Cardoso S, Strauß J, Bolisetty S, Lühder F, Schwaninger M, Binder H, Bechman I, Bopp T, Agarwal A, Soares MP, Regen T, Waisman A. Interleukin-1 promotes autoimmune neuroinflammation by suppressing endothelial heme oxygenase-1 at the blood–brain barrier. Acta Neuropathol. 2020;140(4):549–567. doi: 10.1007/s00401-020-02187-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He L, Ding Y, Zhang Q, Che X, He Y, Shen H, Wang H, Li Z, Zhao L, Geng J, Deng Y, Yang L, Li J, Cai J, Qiu L, Wen K, Xu X, Jiang S. Expression of elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines in SARS-CoV-infected ACE2+ cells in SARS patients: relation to the acute lung injury and pathogenesis of SARS. J Pathol. 2006;210(3):288–297. doi: 10.1002/path.2067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X, Mekasha S, Mavrogiorgos N, Fitzgerald KA, Lien E, Ingalls RR. Inflammation and fibrosis during Chlamydia pneumoniae infection is regulated by IL-1 and the NLRP3/ASC inflammasome. J Immunol. 2010;184(10):5743–5754. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewett SJ, Jackman NA, Claycomb RJ. Interleukin-1β in central nervous system injury and repair. Eur J Neurodegener Dis. 2012;1(2):195–211. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horby, P. W., Pessoa-Amorim, G., Peto, L., Brightling, C. E., Sarkar, R., Thomas, K., Jeebun, V., Ashish, A., Tully, R. & Chadwick, D. (2021) Tocilizumab in patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19 (RECOVERY): preliminary results of a randomised, controlled, open-label, platform trial. medRxiv. 10.1101/2021.02.11.21249258

- Hu T, Liu Y, Zhao M, Zhuang Q, Xu L, He Q. A comparison of COVID-19. SARS and MERS Peerj. 2020;8:e9725. doi: 10.7717/peerj.9725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung EC, Chim SS, Chan PK, Tong YK, Ng EK, Chiu RW, Leung CB, Sung JJ, Tam JS, Lo YM. Detection of SARS coronavirus RNA in the cerebrospinal fluid of a patient with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Clin Chem. 2003;49(12):2108–2109. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2003.025437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israelov H, Ravid O, Atrakchi D, Rand D, Elhaik S, Bresler Y, Twitto-Greenberg R, Omesi L, Liraz-Zaltsman S, Gosselet F, Schnaider Beeri M, Cooper I. Caspase-1 has a critical role in blood-brain barrier injury and its inhibition contributes to multifaceted repair. J Neuroinflammation. 2020;17(1):267. doi: 10.1186/s12974-020-01927-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahanbazi Jahan-Abad A, Karima S, Sahab Negah S, Noorbakhsh F, Borhani-Haghighi M, Gorji A. Therapeutic potential of conditioned medium derived from oligodendrocytes cultured in a self-assembling peptide nanoscaffold in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Brain Res. 2019;1711:226–235. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2019.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katia F, Myriam DP, Ucciferri C, Auricchio A, Di Nicola M, Marchioni M, Eleonora C, Emanuela S, Cipollone F, Vecchiet J. Efficacy of canakinumab in mild or severe COVID-19 pneumonia. Immunity Inflam Dis. 2021;9(2):399–405. doi: 10.1002/iid3.400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempuraj D, Thangavel R, Natteru PA, Selvakumar GP, Saeed D, Zahoor H, Zaheer S, Iyer SS, Zaheer A. Neuroinflammation induces neurodegeneration. J Neurol Neurosurg Spine. 2016;1(1):1003. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kooistra EJ, Waalders NJB, Grondman I, Janssen N, a. F., De Nooijer, A. H., Netea, M. G., Van De Veerdonk, F. L., Ewalds, E., Van Der Hoeven, J. G., Kox, M., Pickkers, P., Kooistra, E. J., Waalders, N. J. B., Grondman, I., Janssen, N. a. F., De Nooijer, A. H., Netea, M. G., Van De Veerdonk, F. L., Ewalds, E., Van Der Hoeven, J. G., Kox, M., Pickkers, P., Hemelaar, P., Beunders, R., Bruse, N., Frenzel, T., Schouten, J., Touw, H., Van Der Velde, S., Van Der Eng, H., Roovers, N., Klop-Riehl, M., Gerretsen, J., Claassen, W., Heesakkers, H., Van Schaik, T., Buijsse, L., Joosten, L., De Mast, Q., Jaeger, M., Kouijzer, I., Dijkstra, H., Lemmers, H., Van Crevel, R., Van De Maat, J., Nijman, G., Moorlag, S., Taks, E., Debisarun, P., Wertheim, H., Hopman, J., Rahamat-Langendoen, J., Bleeker-Rovers, C., Koenen, H., Fasse, E., Van Rijssen, E., Kolkman, M., Van Cranenbroek, B., Smeets, R., Joosten, I. & The, R. C. I. C.-S. G. Anakinra treatment in critically ill COVID-19 patients: a prospective cohort study. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):688. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03364-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon HS, Koh S-H. Neuroinflammation in neurodegenerative disorders: the roles of microglia and astrocytes. Translational Neurodegen. 2020;9(1):42. doi: 10.1186/s40035-020-00221-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landi L, Ravaglia C, Russo E, Cataleta P, Fusari M, Boschi A, Giannarelli D, Facondini F, Valentini I, Panzini I, Lazzari-Agli L, Bassi P, Marchionni E, Romagnoli R, De Giovanni R, Assirelli M, Baldazzi F, Pieraccini F, Rametta G, Rossi L, Santini L, Valenti I, Cappuzzo F. Blockage of interleukin-1β with canakinumab in patients with Covid-19. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):21775. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-78492-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau SKP, Lau CCY, Chan KH, Li CPY, Chen H, Jin DY, Chan JFW, Woo PCY, Yuen KY. Delayed induction of proinflammatory cytokines and suppression of innate antiviral response by the novel Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: implications for pathogenesis and treatment. J Gen Virol. 2013;94(Pt 12):2679–2690. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.055533-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavi E, Cong L. Type I astrocytes and microglia induce a cytokine response in an encephalitic murine coronavirus infection. Exp Mol Pathol. 2020;115:104474. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2020.104474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Yuan M, Li H, Deng C, Wang Q, Tang Y, Zhang H, Yu W, Xu Q, Zou Y, Yuan Y, Guo J, Jin C, Guan X, Xie F, Song J. Safety and efficacy of artemisinin-piperaquine for treatment of COVID-19: an open-label, non-randomised and controlled trial. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2021;57(1):106216. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.106216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Jiang L, Beckmann K, Højen JF, Pessara U, Powers NE, De Graaf DM, Azam T, Lindenberger J, Eisenmesser EZ, Fischer S, Dinarello CA. A novel anti-human IL-1R7 antibody reduces IL-18-mediated inflammatory signaling. J Biol Chem. 2021;296:100630. doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2021.100630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lugrin J, Martinon F. The AIM 2 inflammasome: sensor of pathogens and cellular perturbations. Immunol Rev. 2018;281(1):99–114. doi: 10.1111/imr.12618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madrid-García A, Pérez I, Colomer JI, León-Mateos L, Jover JA, Fernández-Gutiérrez B, Abásolo-Alcazar L, Rodríguez-Rodríguez L. Influence of colchicine prescription in COVID-19-related hospital admissions: a survival analysis. Ther Adv Musculoskeletal Dis. 2021 doi: 10.1177/1759720X211002684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magro G. COVID-19: Review on latest available drugs and therapies against SARS-CoV-2 Coagulation and inflammation cross-talking. Virus Res. 2020;286:198070. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2020.198070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra S, Costa C, Eixarch H, Keller CW, Amman L, Martínez-Banaclocha H, Midaglia L, Sarró E, Machín-Díaz I, Villar LM, Triviño JC, Oliver-Martos B, Parladé LN, Calvo-Barreiro L, Matesanz F, Vandenbroeck K, Urcelay E, Martínez-Ginés ML, Tejeda-Velarde A, Fissolo N, Castilló J, Sanchez A, Robertson A, a. B., Clemente, D., Prinz, M., Pelegrin, P., Lünemann, J. D., Espejo, C., Montalban, X. & Comabella, M. NLRP3 inflammasome as prognostic factor and therapeutic target in primary progressive multiple sclerosis patients. Brain. 2020;143(5):1414–1430. doi: 10.1093/brain/awaa084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamik MK, Hui E, Branton WG, Mckenzie BA, Chisholm J, Cohen EA, Power C. HIV-1 viral protein R activates NLRP3 inflammasome in microglia: implications for HIV-1 associated neuroinflammation. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2017;12(2):233–248. doi: 10.1007/s11481-016-9708-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao L, Jin H, Wang M, Hu Y, Chen S, He Q, Chang J, Hong C, Zhou Y, Wang D, Miao X, Li Y, Hu B. Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan China. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77(6):1–9. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariathasan S, Weiss DS, Newton K, Mcbride J, O'rourke, K., Roose-Girma, M., Lee, W. P., Weinrauch, Y., Monack, D. M. & Dixit, V. M. Cryopyrin activates the inflammasome in response to toxins and ATP. Nature. 2006;440(7081):228–232. doi: 10.1038/nature04515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matschke J, Lütgehetmann M, Hagel C, Sperhake JP, Schröder AS, Edler C, Mushumba H, Fitzek A, Allweiss L, Dandri M, Dottermusch M, Heinemann A, Pfefferle S, Schwabenland M, Sumner Magruder D, Bonn S, Prinz M, Gerloff C, Püschel K, Krasemann S, Aepfelbacher M, Glatzel M. Neuropathology of patients with COVID-19 in Germany: a post-mortem case series. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19(11):919–929. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(20)30308-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra R, Banerjea AC. SARS-CoV-2 Spike Targets USP33-IRF9 Axis via Exosomal miR-148a to Activate Human Microglia. Front Immunol. 2021;12:656700. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.656700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra GP, Mulani J. Corticosteroids for COVID-19: the search for an optimum duration of therapy. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9(1):e8. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30530-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemati M, Rami Y. Parthenolide: suggested drug for COVID-19. Инфeкция и Иммyнитeт. 2020;10(4):786. [Google Scholar]

- Nieto-Torres JL, Dediego ML, Verdiá-Báguena C, Jimenez-Guardeño JM, Regla-Nava JA, Fernandez-Delgado R, Castaño-Rodriguez C, Alcaraz A, Torres J, Aguilella VM, Enjuanes L. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus envelope protein ion channel activity promotes virus fitness and pathogenesis. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10(5):e1004077. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieto-Torres JL, Verdiá-Báguena C, Jimenez-Guardeño JM, Regla-Nava JA, Castaño-Rodriguez C, Fernandez-Delgado R, Torres J, Aguilella VM, Enjuanes L. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus E protein transports calcium ions and activates the NLRP3 inflammasome. Virology. 2015;485:330–339. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2015.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieva JL, Madan V, Carrasco L. Viroporins: structure and biological functions. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2012;10(8):563–574. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’brien, W. T., Pham, L., Symons, G. F., Monif, M., Shultz, S. R. & Mcdonald, S. J. The NLRP3 inflammasome in traumatic brain injury: potential as a biomarker and therapeutic target. J Neuroinflammation. 2020;17(1):104. doi: 10.1186/s12974-020-01778-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olajide, O. A., Iwuanyanwu, V. U. & Adegbola, O. D. (2020) SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein S1 induces neuroinflammation in BV-2 microglia. bioRxiv. 10.1101/2020.12.29.424619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Olajide, O. A., Iwuanyanwu, V. U., Lepiarz-Raba, I. & Al-Hindawi, A. A. (2021) Exaggerated cytokine production in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells by recombinant SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein S1 and its inhibition by dexamethasone. bioRxiv. Doi. 10.1101/2021.02.03.429536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Paniz-Mondolfi A, Bryce C, Grimes Z, Gordon RE, Reidy J, Lednicky J, Sordillo EM, Fowkes M. Central nervous system involvement by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) J Med Virol. 2020;92(7):699–702. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pareek RP. Use of mefenamic acid as a supportive treatment of COVID-19: a repurposing drug. Int J Sci Res. 2020;9(6):69. doi: 10.21275/SR20530150407. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pasin L, Cavalli G, Navalesi P, Sella N, Landoni G, Yavorovskiy AG, Likhvantsev VV, Zangrillo A, Dagna L, Monti G. Anakinra for patients with COVID-19: a meta-analysis of non-randomized cohort studies. Eur J Intern Med. 2021;86:34–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2021.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrosillo N, Viceconte G, Ergonul O, Ippolito G, Petersen E. COVID-19, SARS and MERS: are they closely related? Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;26(6):729–734. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes AZ, Hu KA, Teperman J, Wampler Muskardin TL, Tardif J-C, Shah B, Pillinger MH. Anti-inflammatory therapy for COVID-19 infection: the case for colchicine. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80(5):550–557. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-219174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezaeitalab F, Jamehdar SA, Sepehrinezhad A, Rashidnezhad A, Moradi F, Fard SE, F., Hasanzadeh, S., Etezad Razavi, M., Gorji, A. & Sahab Negah, S. Detection of SARS-coronavirus-2 in the central nervous system of patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome and seizures. J Neurovirol. 2021;27(2):348–353. doi: 10.1007/s13365-020-00938-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riazi K, Galic MA, Kuzmiski JB, Ho W, Sharkey KA, Pittman QJ. Microglial activation and TNFα production mediate altered CNS excitability following peripheral inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2008;105(44):17151–17156. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806682105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro DE, Oliveira-Giacomelli Á, Glaser T, Arnaud-Sampaio VF, Andrejew R, Dieckmann L, Baranova J, Lameu C, Ratajczak MZ, Ulrich H. Hyperactivation of P2X7 receptors as a culprit of COVID-19 neuropathology. Mol Psychiatry. 2021;26(4):1044–1059. doi: 10.1038/s41380-020-00965-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson PC, Morand E. Divergent effects of acute versus chronic glucocorticoids in COVID-19. Lancet Rheumatol. 2021;3(3):e168–e170. doi: 10.1016/S2665-9913(21)00005-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, T. S., De Sá, K. S. G., Ishimoto, A. Y., Becerra, A., Oliveira, S., Almeida, L., Gonçalves, A. V., Perucello, D. B., Andrade, W. A., Castro, R., Veras, F. P., Toller-Kawahisa, J. E., Nascimento, D. C., De Lima, M. H. F., Silva, C. M. S., Caetite, D. B., Martins, R. B., Castro, I. A., Pontelli, M. C., De Barros, F. C., Do Amaral, N. B., Giannini, M. C., Bonjorno, L. P., Lopes, M. I. F., Santana, R. C., Vilar, F. C., Auxiliadora-Martins, M., Luppino-Assad, R., De Almeida, S. C. L., De Oliveira, F. R., Batah, S. S., Siyuan, L., Benatti, M. N., Cunha, T. M., Alves-Filho, J. C., Cunha, F. Q., Cunha, L. D., Frantz, F. G., Kohlsdorf, T., Fabro, A. T., Arruda, E., De Oliveira, R. D. R., Louzada-Junior, P. & Zamboni, D. S. (2021) Inflammasomes are activated in response to SARS-CoV-2 infection and are associated with COVID-19 severity in patients. J Exp Med 218(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Salama C, Han J, Yau L, Reiss WG, Kramer B, Neidhart JD, Criner GJ, Kaplan-Lewis E, Baden R, Pandit L. Tocilizumab in patients hospitalized with Covid-19 pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(1):20–30. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2030340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satış H, Özger HS, Aysert Yıldız P, Hızel K, Gulbahar Ö, Erbaş G, Aygencel G, Guzel Tunccan O, Öztürk MA, Dizbay M, Tufan A. Prognostic value of interleukin-18 and its association with other inflammatory markers and disease severity in COVID-19. Cytokine. 2021;137:155302. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2020.155302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott XO, Stephens ME, Desir MC, Dietrich WD, Keane RW, De Rivero Vaccari JP. The inflammasome adaptor protein ASC in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(13):4674. doi: 10.3390/ijms21134674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sepehrinezhad A, Shahbazi A, Negah SS. COVID-19 virus may have neuroinvasive potential and cause neurological complications: a perspective review. J Neurovirol. 2020;26:324–329. doi: 10.1007/s13365-020-00851-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sepehrinezhad A, Rezaeitalab F, Shahbazi A, Sahab-Negah S. A computational-based drug repurposing method targeting SARS-CoV-2 and its neurological manifestations genes and signaling pathways. Bioinform Biol Insights. 2021;15:11779322211026728. doi: 10.1177/11779322211026728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah FH, Lim KH, Kim SJ. Do fever-relieving medicines have anti-COVID activity: an in silico insight. Futur Virol. 2021;16(4):293–300. doi: 10.2217/fvl-2020-0398. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shi C-S, Nabar NR, Huang N-N, Kehrl JH. SARS-Coronavirus Open Reading Frame-8b triggers intracellular stress pathways and activates NLRP3 inflammasomes. Cell Death Discovery. 2019;5(1):101. doi: 10.1038/s41420-019-0181-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siu KL, Yuen KS, Castaño-Rodriguez C, Ye ZW, Yeung ML, Fung SY, Yuan S, Chan CP, Yuen KY, Enjuanes L, Jin DY. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus ORF3a protein activates the NLRP3 inflammasome by promoting TRAF3-dependent ubiquitination of ASC. Faseb j. 2019;33(8):8865–8877. doi: 10.1096/fj.201802418R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song, E., Zhang, C., Israelow, B., Lu-Culligan, A., Prado, A. V., Skriabine, S., Lu, P., Weizman, O.-E., Liu, F., Dai, Y., Szigeti-Buck, K., Yasumoto, Y., Wang, G., Castaldi, C., Heltke, J., Ng, E., Wheeler, J., Alfajaro, M. M., Levavasseur, E., Fontes, B., Ravindra, N. G., Van Dijk, D., Mane, S., Gunel, M., Ring, A., Jaffar Kazmi, S. A., Zhang, K., Wilen, C. B., Horvath, T. L., Plu, I., Haik, S., Thomas, J.-L., Louvi, A., Farhadian, S. F., Huttner, A., Seilhean, D., Renier, N., Bilguvar, K. & Iwasaki, A. (2020a) Neuroinvasion of SARS-CoV-2 in human and mouse brain. bioRxiv:2020.06.25.169946.

- Song, E., Zhang, C., Israelow, B., Lu-Culligan, A., Sprado, A., Skriabine, S., Lu, P., Weizman, O.-E., Liu, F. & Dai, Y. (2020b) Neuroinvasion of SARS-CoV-2 in human and mouse brain. bioRxiv. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Stehlik C, Lee SH, Dorfleutner A, Stassinopoulos A, Sagara J, Reed JC. Apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a caspase recruitment domain is a regulator of procaspase-1 activation. J Immunol. 2003;171(11):6154–6163. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.11.6154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swayne LA, Johnstone SR, Ng CS, Sanchez-Arias JC, Good ME, Penuela S, Lohman AW, Wolpe AG, Laubach VE, Koval M, Isakson BE. Consideration of Pannexin 1 channels in COVID-19 pathology and treatment. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2020;319(1):L121–l125. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00146.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thelin EP, Hall CE, Gupta K, Carpenter KLH, Chandran S, Hutchinson PJ, Patani R, Helmy A. Elucidating pro-inflammatory cytokine responses after traumatic brain injury in a human stem cell model. J Neurotrauma. 2018;35(2):341–352. doi: 10.1089/neu.2017.5155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas PG, Dash P, Aldridge JR, Jr, Ellebedy AH, Reynolds C, Funk AJ, Martin WJ, Lamkanfi M, Webby RJ, Boyd KL, Doherty PC, Kanneganti TD. The intracellular sensor NLRP3 mediates key innate and healing responses to influenza A virus via the regulation of caspase-1. Immunity. 2009;30(4):566–575. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ting JP, Lovering RC, Alnemri ES, Bertin J, Boss JM, Davis BK, Flavell RA, Girardin SE, Godzik A, Harton JA, Hoffman HM, Hugot JP, Inohara N, Mackenzie A, Maltais LJ, Nunez G, Ogura Y, Otten LA, Philpott D, Reed JC, Reith W, Schreiber S, Steimle V, Ward PA. The NLR gene family: a standard nomenclature. Immunity. 2008;28(3):285–287. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toldo S, Bussani R, Nuzzi V, Bonaventura A, Mauro AG, Cannatà A, Pillappa R, Sinagra G, Nana-Sinkam P, Sime P, Abbate A. Inflammasome formation in the lungs of patients with fatal COVID-19. Inflamm Res. 2021;70(1):7–10. doi: 10.1007/s00011-020-01413-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toma C, Higa N, Koizumi Y, Nakasone N, Ogura Y, Mccoy AJ, Franchi L, Uematsu S, Sagara J, Taniguchi S, Tsutsui H, Akira S, Tschopp J, Núñez G, Suzuki T. Pathogenic Vibrio activate NLRP3 inflammasome via cytotoxins and TLR/nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-mediated NF-kappa B signaling. J Immunol. 2010;184(9):5287–5297. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uckun FM, Saund S, Windlass H, Trieu V. Repurposing anti-malaria phytomedicine artemisinin as a COVID-19 drug. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:407. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.649532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulhaq ZS, Soraya GV. Anti-IL-6 receptor antibody treatment for severe COVID-19 and the potential implication of IL-6 gene polymorphisms in novel coronavirus pneumonia. Med Clin (barc) 2020;155(12):548–556. doi: 10.1016/j.medcli.2020.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venero JL, Burguillos MA, Joseph B. Caspases playing in the field of neuroinflammation: old and new players. Dev Neurosci. 2013;35(2–3):88–101. doi: 10.1159/000346155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan Y, Shang J, Graham R, Baric RS, Li F. Receptor recognition by the novel coronavirus from Wuhan: an analysis based on decade-long structural studies of SARS coronavirus. J Virol. 2020;94(7):e00127–e220. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00127-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Jin S, Sonobe Y, Cheng Y, Horiuchi H, Parajuli B, Kawanokuchi J, Mizuno T, Takeuchi H, Suzumura A. Interleukin-1β induces blood-brain barrier disruption by downregulating Sonic hedgehog in astrocytes. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(10):e110024. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Nguyen LT, Burlak C, Chegini F, Guo F, Chataway T, Ju S, Fisher OS, Miller DW, Datta D, Wu F, Wu CX, Landeru A, Wells JA, Cookson MR, Boxer MB, Thomas CJ, Gai WP, Ringe D, Petsko GA, Hoang QQ. Caspase-1 causes truncation and aggregation of the Parkinson's disease-associated protein α-synuclein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(34):9587–9592. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1610099113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H., Chitre, S. A., Akinyemi, I. A., Loeb, J. C., Lednicky, J. A., Mcintosh, M. T. & Bhaduri-Mcintosh, S. (2020) SARS-CoV-2 viroporin triggers the NLRP3 inflammatory pathway. bioRxiv:2020.10.27.357731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Yu, D. & Zhang, X. (2006) Differential induction of proinflammatory cytokines in primary mouse astrocytes and microglia by coronavirus infection. In The Nidoviruses.) Springer, pp. 407–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Zhao Z, Wei Y, Tao C. An enlightening role for cytokine storm in coronavirus infection. Clin Immunol. 2021;222:108615. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2020.108615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Lu M, Du RH, Qiao C, Jiang CY, Zhang KZ, Ding JH, Hu G. MicroRNA-7 targets Nod-like receptor protein 3 inflammasome to modulate neuroinflammation in the pathogenesis of Parkinson's disease. Mol Neurodegener. 2016;11:28. doi: 10.1186/s13024-016-0094-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.