Abstract

Objective

Persistent post-COVID symptoms are estimated to occur in up to 10% of patients who have had COVID-19. These lingering symptoms may persist for weeks to months after resolution of the acute illness. This study aimed to add insight into our understanding of certain post-acute conditions and clinical findings. The primary purpose was to determine the persistent post COVID impairments prevalence and characteristics by collecting post COVID illness data utilizing Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS®). The resulting measures were used to assess surveyed patients physical, mental, and social health status.

Methods

A cross-sectional study and 6-months Mayo Clinic COVID recovered registry data were used to evaluate continuing symptoms severity among the 817 positive tested patients surveyed between March and September 2020. The resulting PROMIS® data set was used to analyze patients post 30 days health status. The e-mailed questionnaires focused on fatigue, sleep, ability to participate in social roles, physical function, and pain.

Results

The large sample size (n = 817) represented post hospitalized and other managed outpatients. Persistent post COVID impairments prevalence and characteristics were determined to be demographically young (44 years), white (87%), and female (61%). Dysfunction as measured by the PROMIS® scales in patients recovered from acute COVID-19 was reported as significant in the following domains: ability to participate in social roles (43.2%), pain (17.8%), and fatigue (16.2%).

Conclusion

Patient response on the PROMIS® scales was similar to that seen in multiple other studies which used patient reported symptoms. As a result of this experience, we recommend utilizing standardized scales such as the PROMIS® to obtain comparable data across the patients’ clinical course and define the disease trajectory. This would further allow for effective comparison of data across studies to better define the disease process, risk factors, and assess the impact of future treatments.

Keywords: COVID-19, fatigue, long haulers, PASC, PROMIS, SARS-CoV-2, social roles, survey, post COVID syndrome, post COVID symptoms

Introduction

In 2020, the medical community was challenged by the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, caused by Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). This previously unidentified coronavirus infection has proved to be highly contagious, infecting over 150 million people worldwide and causing over 3 million deaths as of May 2021. 1 Patients with severe COVID-19 often develop hypoxia secondary to pneumonitis which often require hospitalization, and this may progress to acute respiratory distress as part of a multisystem inflammatory disease which can necessitate Intensive Care Unit (ICU) care, mechanical ventilation, and may lead to death.

Although most patients eventually recover from their acute COVID-19 infection (<3 weeks), it has become well recognized that many patients continue to suffer from persistent post-infectious symptoms including fatigue, dyspnea, pain, and palpitations.2-5 The prevalence of persistent post-COVID symptoms has been estimated at about 10% in the general population, and may be in excess of 70% in the post-hospital setting.2,3,6 While still being defined, these persistent symptoms (>28 days) can be collectively referred to as Post-Acute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC). As we currently have in excess of 147 million patients who have recovered from acute COVID-19 infection, there are likely several million people suffering from PASC worldwide. Some patients with PASC may suffer from persistent single symptoms such as anosmia versus others with multiple including diffuse pain, fatigue, and brain fog which is consistent with a post-COVID syndrome that mirrors other post viral illness. Having PASC and post-COVID syndrome has led to disruption of work life, decreased productivity and financial hardship for many. 7 Elucidating the duration, frequency, and type of symptoms after acute COVID-19 infection will provide clarity to the post-COVID syndrome and enable better research into the underlying pathophysiologic mechanisms, thereby guiding individualized patient management.

Given the extreme infectivity of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, public health recommendations to minimize spread have included physical distancing, cancelling of many in person social events, and curtailing of travel. While these measures have been successful in reducing the spread of this highly contagious viral illness, there has also been a coincident increase in social isolation, depression, anxiety, and other adverse mental health conditions, including suicidal ideation and substance abuse. 8 These conditions are likely exacerbated by the financial impact of the pandemic which has left many without jobs and steady income. Assessment of impairments in the ability to participate in social roles and adverse impact on mental health could allow for early interventions and improved outcomes.

The Mayo Clinic COVID Frontline Care Team (CFCT) in Rochester, Minnesota has provided telemedicine care for over 36 000 patients who tested positive for COVID-19 in the Midwest since March 2020, including follow up after hospital discharge.9,10 This telemedicine team was one of the multiple innovations undertaken by the Mayo Clinic in the COVID-19 response which has led to favorable patient outcomes including reductions in COVID-related admission. 11 Many of these patients reported persistent symptoms post COVID infection, primarily concerning impairments in functional aspects of life. The primary aim of this study was to determine the prevalence and characteristics of persistent physical and social impairment after recovery from acute COVID-19 infection in the population served by the CFCT.

Methods

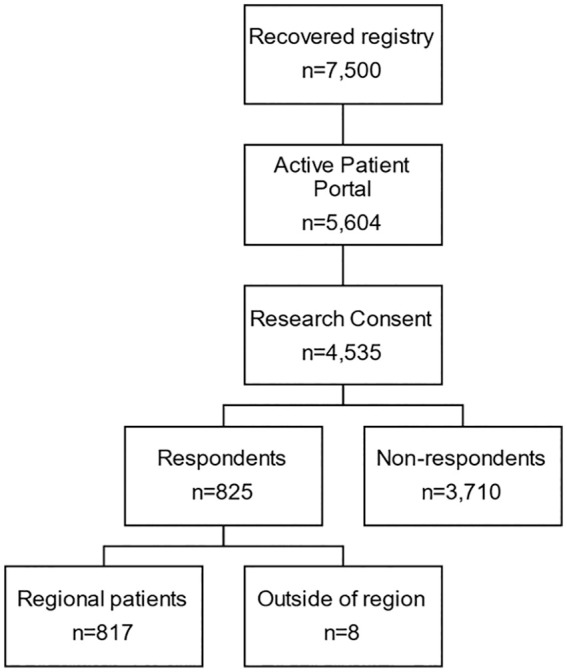

This retrospective cross-sectional survey study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board. The Mayo Clinic maintains a COVID recovered registry which consists of patients identified by history of positive PCR for SARS-CoV-2 who meet the clinical definition of recovery from COVID-19 (either resolution of symptoms or >30 days post initial positive PCR test). Within this registry, a total of 7500 patients were identified as being from the Midwest region between March 1, 2020 and September 12, 2020. Of these 7500 patients within this registry, 5604 had an active patient portal in the electronic medical record (EMR) of which 4535 of these had documented research consent. These 4535 patients had been e-mailed a series of questionnaires on their patient portals by the clinical care team on September 12, 2020. The questionnaires sent out were select PROMIS® (Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System) 12 Computer Adaptive Tests (CATs) for fatigue (v2.0), sleep disturbance (v1.0), sleep-related impairment (v1.0), ability to participate in social roles and activities (v2.0), physical function (v2.0), and pain interference (v1.1). A total of 825 (18.2%) patients responded to the surveys on the patient portal and of these, 8 of the respondents did not have complete demographic information in their chart and so were not included in the final analysis. In summary, this analysis is based on the data linked between the available PROMIS® survey data of the 817 patients with their COVID Recovery Registry data. (Figure 1). The average time span between testing positive for COVID-19 and completing the PROMIS® questionnaires was 68.3 ± 45.3 days.

Figure 1.

Patient selection and response to questionnaires.

Demographic characteristics were abstracted from the registry information and are presented in Table 1. Z-scores were calculated for respondents vs. non-respondents and their associated P-values are reported in Table 1. The PROMIS® questionnaires are scaled to fit a T-scale, which has a normal distribution with a mean score of 50 and each standard deviation being represented by 10 points, and have been clinically validated in multiple conditions. In particular, the PROMIS® questionnaires for fatigue,13-15 pain interference,16-18 and ability to participate in social roles 19 have been validated for syndromes such as fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS). These syndromes have similarly diverse, chronic symptoms of incompletely defined etiology similar to the post-COVID syndrome. We chose the PROMIS® scales for fatigue, sleep, ability to participate in social roles, physical function, and pain based on frequently reported symptoms in post-COVID syndrome both in the literature and in our clinical experience. PROMIS® symptom scores >1 standard deviation (SD) of the mean were considered moderate severity and scores >2 SD of the mean were considered severe.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Survey Respondents and Non-Respondents in the Recovery Cohort.

| Non-respondents | Respondents | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of patients | 3710 | 817 | |

| Mean age | 37 (17) | 44 (17) | <.001 |

| Sex (%) | |||

| Female | 1822 (49.1) | 499 (61.1) | <.001 |

| Male | 1883 (50.9) | 318 (38.9) | <.001 |

| Unknown | 5 (0.1) | 0 (0) | .29 |

| Primary language (%) | |||

| English | 3202 (86.3) | 787 (96.3) | <.001 |

| Non-English: Interpreter not needed | 137 (3.7) | 12 (1.5) | .001 |

| Non-English: Interpreter needed | 295 (8.1) | 18 (2.2) | <.001 |

| Race (%) | |||

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 6 (0.2) | 2 (0.2) | .61 |

| Asian | 92 (2.5) | 21 (2.6) | .88 |

| Black/African American | 310 (8.6) | 33 (4.0) | <.001 |

| White | 3002 (80.9) | 707 (86.5) | <.001 |

| Other | 300 (8.3) | 54 (6.6) | .16 |

Results

Characteristics of Respondents

The mean interval between initial positive PCR for SARS-CoV-2 and survey response was 68.4 days. Demographics of the cohort are displayed in Table 1. Notably, the mean age of our respondent population was older than the non-respondents (44 years vs 37 years, P < .001) and a greater proportion were female (61.1% vs 49.1%, P < .001). The majority of respondents spoke English as their primary language (96.3%) which was again significantly higher than the proportion in non-respondents (86.3%). Conversely, patients who were not primarily English-speaking made up a lower proportion of respondents compared to non-respondents (interpreter not needed: 1.5% vs 3.7%, P = .001; interpreter needed: 2.2% vs 8.1%, P < .001). The racial composition of the respondent group was also different from the non-respondent group with the proportion of White (86.5% vs 80.9%, P < .001) and Black patients (4.0% vs 8.6%, P < .001) reaching statistical significance.

PROMIS® Scores

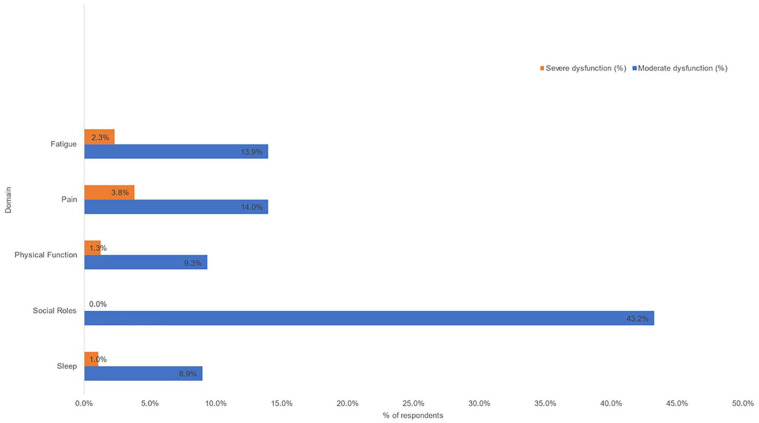

Symptom severity as defined by PROMIS® scores is shown in Table 2 and illustrated in Figure 2. There was variation in response rate across the CATs ranging from 79.5% completion for the ability to participate in social roles CAT to 90.5% on the fatigue CAT. PROMIS® scores >1 standard deviation worse than normal were noted in ability to participate in social roles (43.2%), pain interference (17.8%), fatigue (16.2%), physical function (10.6%), and sleep (10.0%). PROMIS® scores >2 standard deviations worse than normal were noted in pain interference (3.8%), fatigue (2.3%), physical function (1.3%), and sleep (1.0%).

Table 2.

Dysfunction on PROMIS Scales in Patients Recovered from Acute COVID-19.

| Number of respondents (% of total) | Dysfunction on PROMIS domain (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any (>1 SD) | Moderate (1-2 SD) | Severe (>2 SD) | ||

| PROMIS domain | ||||

| Social roles | 650 (79.6) | 281 (43.2) | 281 (43.2) | 0 (0) |

| Pain | 738 (90.3) | 131 (17.8) | 103 (14.0) | 28 (3.8) |

| Fatigue | 739 (90.6) | 120 (16.2) | 103 (13.9) | 17 (2.3) |

| Physical function | 719 (88.0) | 76 (10.6) | 67 (9.3) | 9 (1.3) |

| Sleep | 671 (82.1) | 67 (10.0) | 60 (8.9) | 7 (1.0) |

Figure 2.

Dysfunction in PROMIS domains in patients recovered from acute COVID-19.

Discussion

This retrospective cross-sectional survey study demonstrates several important findings—(1) PASC symptoms (>30 days) are common in patients after resolution of acute COVID-19 disease and lead to impairment in ability to participate in social roles and physical function, (2) PROMIS® scales reliably assess these symptoms and are comparable to findings in other survey studies, (3) survey tools for assessing post COVID symptoms preferentially select for the language the tool is delivered in, and (4) persistent PASC symptoms are more common in women.

The three most commonly impacted domains of the PROMIS® scale were ability to participate in social roles, fatigue, and pain interference, which is similar to symptoms reported in other studies of post-COVID syndrome which cite pain, fatigue, and dyspnea as the most common manifestations of the condition.2-4,6,7,20 These studies used patient reported symptoms, and not a standardized tool such as the PROMIS® survey. We believe the current study is the first to utilize the PROMIS® scales to assess physical and social dysfunction in patients with post-COVID syndrome, and one of the few to examine the social impact of post-COVID syndrome. A recent study conducted in the United Kingdom found that fatigue, pain, and social role deficiencies including PTSD symptoms, anxiety/depression, and concentration problems were the among the most common post-discharge symptoms. 3 Another recent CDC study reported that COVID-19 infections have been associated with adverse mental health conditions including substance use and suicidal ideation. 5 Further, 8% of seropositive patients in a Swedish study of health care professionals reported disruption to their work life and 15% reported disruption to their social life. 7 These findings reflect that patients with post-COVID syndrome not only suffer from higher symptom burden but are impaired in their ability to participate in social roles, which may have further interplay with symptom progression.

The PROMIS® surveys were delivered in English, which was a limitation of this study, as it led to statistically significant predominance of respondents being White/Caucasian as well as predominantly English-speaking. We also observed decreased response rates in traditionally underserved groups including Black and other racial minorities who are not primarily English-speaking. This may have been due to factors other than language including decreased trust of the medical establishment, decreased access to technology to access the patient portal and questionnaires, as well as comparatively poor health literacy and engagement.

One notable difference between our study population and that described in the previous literature is in the age of our demographic. The mean age of our patient population was 44.4 years, which is significantly lower than the mean ages previously reported for persistent post-COVID symptoms of 56.5 years 2 and 70.5 years. 3 We also report a higher incidence of females in our population than previously reported—61.1% as compared to 37.1%, 2 48.5%, 3 and 48.1%. 5 There are existing data suggesting that women have a distinctly different COVID-19 immune response as compared to men. 21 Additionally, a longitudinal app-based survey of symptoms in London demonstrated a similar increased prevalence of persistent post-COVID symptoms in women (14.9% of all recovered patients vs 9.5% in men). 22 Based on this information, it is reasonable to hypothesize that sex differences in immune response to COVID-19 may be associated with development of persistent post-COVID symptoms.

The average duration of symptoms at the time of our survey was 68.4 days, which reinforces the existing data and our understanding of the duration of persistent post-COVID symptoms.4,5 Additionally, our findings confirm that the post-COVID syndrome may occur across a spectrum of acute illness severity, ranging from those managed outpatient to those severe enough to require hospitalization. We also demonstrate that the duration of post-COVID symptoms in patients who received outpatient management has the potential to extend to a period similar to that of patients who were hospitalized.2-4 That the most commonly reported post-discharge symptoms remained congruous suggests a common underlying etiology to the development of persistent post-COVID symptoms which is at least partially independent of age or acute illness severity. Understanding of the underlying process is the subject of multiple ongoing research efforts.

Our sample size is large and heterogeneous, representing both patients who are post-hospitalization as well as those who were never admitted. This compares favorably to previous study sample compositions—817 patients in our sample compared to 143, 2 191, 3 292, 5 and 177. 4 We do however recognize limitations inherent to our cross-sectional study design related to generalizability and inability to assess causation. The survey data collected in this trial was clinical survey data and utilized the patient portal system of our institution. As such, there was only one mailing and if the patient did not return to the health care facility there was no other opportunity to complete the surveys, therefore we do not know the reason for the non-responses, We recognize that the response rate or these surveys is low (18.2%) but it should be recognized that the response rates of surveys have been steadily declining in recent years.23-28 and the response rate of 18.2% is actually on the upper end of standard survey response rate (14.2%) for electronic surveys. 29 In addition to the limitations discussed above regarding the characteristics of respondents, there is likely some response bias in that those with more severe symptoms were more likely to respond. PROMIS® scales exist for a wide array of symptoms including for psychological disturbance and additional scales for anxiety and depression could be employed to better delineate social and psychological impacts post COVID. One limitation here, however, is that some common post-COVID symptoms such as dyspnea, anosmia, and orthostatic intolerance do not have a matching scale in the PROMIS® ecosystem, so would need to be assessed with a separate symptom scale. A final limitation is that the PROMIS® survey data was only collected once post COVID-19. Although this provided us with good data on the mental and physical health of the patients post-COVID-19 compared to the normal US population, it would have been ideal if the patient had other PROMIS® measures on file, such as pre-COVID-19 or during COVID-19 in order to monitor progression of mental and physical health.

Conclusion

Persistent symptoms are common after resolution of acute COVID infection, particularly in women. These symptoms are reliably assessed using PROMIS® scales which are readily administered via the EMR. Based on this, we advocate the use of the PROMIS® scales as a standardized measurement tool to ensure consistency across studies.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank all the survey participants who took the time to complete the study surveys. Without their participation, this study would not have been possible.

Footnotes

Authors’ Contributions: RG, AKG, MAN, ITC, SLG, CVA, BRS, and RTH made substantial contributions to the concept and design of the study, the interpretation of data, and the critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, made substantial contributions to the acquisition of data, the analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, and substantial contributions to critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported in part by funds from our Division. The data entry system used was RedCap, supported in part by the Center for Clinical and Translational Science award (UL1 TR000135) from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS).

Ethics and Consent to Participate: In accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, this study was reviewed and approved (ID 20-003360) by the Institutional Review Board (IRB). Protocol-approved passive consent was obtained from all study participants prior to study initiation.

Ethical Standards: This study was determined to be EXEMPT under 45 CFR 46.101, item 2 by the Institutional Review Board which had ethical oversight for this study. In addition, the authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the Institutional Review Board guidelines on human experimentation in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki of 1975, as revised in 2008. Protocol-approved passive consent was obtained from all study participants prior to study initiation.

ORCID iDs: Ravindra Ganesh  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6877-1712

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6877-1712

Ivana T. Croghan  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3464-3525

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3464-3525

Stephanie L. Grach  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8337-6219

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8337-6219

Availability of Data and Materials: All data supporting the study findings are contained within this manuscript

References

- 1. Johns Hopkins University & Medicine. Coronavirus Resource Center. 2021. Accessed May 2, 2021. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/

- 2. Carfì A, Bernabei R, Landi F, Gemelli Against COVID-19 Post-Acute Care Study Group. Persistent symptoms in patients after acute COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;324(6):603-605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Halpin SJ, McIvor C, Whyatt G, et al. Postdischarge symptoms and rehabilitation needs in survivors of COVID-19 infection: a cross-sectional evaluation. J Med Virol. 2021;93(2):1013-1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Logue JK, Franko NM, McCulloch DJ, et al. Sequelae in adults at 6 months after COVID-19 infection. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(2):e210830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tenforde MW, Kim SS, Lindsell CJ, et al. Symptom duration and risk factors for delayed return to usual health among outpatients with COVID-19 in a multistate health care systems network – United States, March-June 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(30):993-998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Greenhalgh T, Knight M, A’Court C, Buxton M, Husain L. Management of post-acute covid-19 in primary care. BMJ. 2020;370:m3026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Havervall S, Rosell A, Phillipson M, et al. Symptoms and functional impairment assessed 8 months after mild COVID-19 among health care workers. JAMA. 2021;325(19):2015-2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Czeisler ME, Lane RI, Petrosky E, et al. Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic – United States, June 24-30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(32):1049-1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Crane SJ, Ganesh R, Post JA, Jacobson NA. Telemedicine consultations and follow-up of patients with COVID-19. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95(9S):S33-S34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ganesh R, Salonen BR, Bhuiyan MN, et al. Managing patients in the COVID-19 pandemic: a virtual multidisciplinary approach. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2021;5(1):118-126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. O’Horo JC, Cerhan JR, Cahn EJ, et al. Outcomes of COVID-19 with the Mayo Clinic model of care and research. Mayo Clin Proc. 2021;96(3):601-608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. National Institutes of Health. Patient-Reported Oucomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS®). Program: PROMIS® web site. 2019. Updated January 29, 2019. Accessed May 5, 2021. https://commonfund.nih.gov/PROMIS®/index

- 13. Ameringer S, Elswick RK Jr, Menzies V, et al. Psychometric evaluation of the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system fatigue-short form across diverse populations. Nurs Res. 2016;65(4):279-289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yang M, Keller S, Lin JS. Psychometric properties of the PROMIS® ((R)) fatigue short form 7a among adults with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Qual Life Res. 2019;28(12):3375-3384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yost KJ, Waller NG, Lee MK, Vincent A. The PROMIS® fatigue item bank has good measurement properties in patients with fibromyalgia and severe fatigue. Qual Life Res. 2017;26(6):1417-1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Askew RL, Cook KF, Revicki DA, Cella D, Amtmann D. Evidence from diverse clinical populations supported clinical validity of PROMIS® pain interference and pain behavior. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;73:103-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Merriwether EN, Rakel BA, Zimmerman MB, et al. Reliability and construct validity of the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS®) instruments in women with fibromyalgia. Pain Med. 2017;18(8):1485-1495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nayfe R, Chansard M, Hynan LS, et al. Comparison of patient-reported outcomes measurement information system and legacy instruments in multiple domains among older veterans with chronic back pain. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2020;21(1):598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cook KF, Jensen SE, Schalet BD, et al. PROMIS® measures of pain, fatigue, negative affect, physical function, and social function demonstrated clinical validity across a range of chronic conditions. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;73:89-102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lambert NJ, Corps S. COVID-19 “Long Hauler” Symptoms Survey Report. Indiana University School of Medicine; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Takahashi T, Ellingson MK, Wong P, et al. Sex differences in immune responses that underlie COVID-19 disease outcomes. Nature. 2020;588(7837):315-320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sudre CH, Murray B, Varsavsky T, et al. Attributes and predictors of long COVID. Nat Med. 2021;27(4):626-631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bradburn NM. Presidential address: a response to the nonresponse problem. Public Opin Q. 1992;56:391-397. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Groves RM. Survey Errors and Survey Costs. John Wiley & Sons; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Curtin R, Presser S, Singer E. Changes in telephone survey nonresponse over the past quarter century. Public Opin Q. 2005;69:87-98. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nohr EA, Frydenberg M, Henriksen TB, Olsen J. Does low participation in cohort studies induce bias? Epidemiology. 2006;17:413-418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Forthofer RN. Investigation of nonresponse bias in NHANES II. Am J Epidemiol. 1983;117:507-515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bradshaw L, Sumner J, Delic J, Henneberger P, Fishwick D. Work aggravated asthma in Great Britain: a cross-sectional postal survey. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2018:19(6):561-569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hardigan PC, Popovici I, Carvajal MJ. Response rate, response time, and economic costs of survey research: a randomized trial of practicing pharmacists. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2016;12(1):141-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]