Abstract

Background:

To inform clinical practice and policy, it is essential to understand the lived experience of health and social care policies, including restricted visitation policies towards the end of life.

Aim:

To explore the views and experiences of Twitter social media users who reported that a relative, friend or acquaintance died of COVID-19 without a family member/friend present.

Design:

Qualitative content analysis of English-language tweets.

Data sources:

Twitter data collected 7–20th April 2020. A bespoke software system harvested selected publicly-available tweets from the Twitter application programming interface. After filtering we hand-screened tweets to include only those referring to a relative, friend or acquaintance who died alone of COVID-19. Data were analysed using thematic content analysis.

Results:

9328 tweets were hand-screened; 196 were included. Twitter users expressed sadness, despair, hopelessness and anger about their experience and loss. Saying goodbye via video-conferencing technology was viewed ambivalently. Clinicians’ presence during a death was little consolation. Anger, frustration and blame were directed at governments’ inaction/policies or the public. The sadness of not being able to say goodbye as wished was compounded by lack of social support and disrupted after-death rituals. Users expressed a sense of political neglect/mistreatment alongside calls for action. They also used the platform to reinforce public health messages, express condolences and pay tribute.

Conclusion:

Twitter was used for collective mourning and support and to promote public health messaging. End-of-life care providers should facilitate and optimise contact with loved ones, even when strict visitation policies are necessary, and provide proactive bereavement support.

Keywords: Bereavement, grief, pandemics, coronavirus infections, social media

What is already known about the topic?

Twitter is a rich repository of data reflecting contemporaneous public opinion.

The idea of dying alone is contrary to the concept of a ‘good death’ in many cultures, and not being able to say goodbye is a known risk factor for poor bereavement outcomes.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many bereaved people have been unable to be present when their loved one died due to setting-specific infection control restrictions that vary across regions and institutions.

What this paper adds?

Twitter users expressed sadness, despair, hopelessness and anger about their experience and loss during the COVID-19 pandemic, with the challenges they experienced before the death compounded by a lack of social support and disrupted rituals afterwards.

A sense of political neglect or mistreatment was frequently expressed, alongside calls for action, but Twitter users also used the platform to encourage positive public health messages, express condolences to and support others, and pay tribute to the deceased.

There was ambivalence about the use of video-conferencing technology, which was often presented as an inadequate substitute, and frustration and blame were directed at governments’ inaction and policies as well as the behaviour of the general public.

Implications for practice and policy

Governments should provide clear guidance to support end-of-life care providers in facilitating and optimising contact with loved ones, even when strict visiting policies are necessary; this must include adequate access to personal protective equipment.

Signposting bereaved family members and friends to bereavement services, and proactively identifying and supporting those at particular risk of poor outcomes, is as crucial during a pandemic, as it is in non-pandemic times.

Further research is needed to fully understand the emotional toll expressed in these tweets and the immediate and sustained impacts of bereavement during the pandemic.

Background

COVID-19 has caused over 2.5 million deaths worldwide 1 so far. With each death associated with nine close bereavements, 2 an estimated 22.5 million family members and friends have been bereaved in just over a year. It is a time of great unpredictability, with understanding of the burden and course of future disease still evolving, 3 and changing policy messages have created significant public uncertainty. Understanding the lived experience of health and social care policies is essential to inform local, national and international policy-making.

Social media use has boomed in recent years 4 and has transformed how people mourn and express their grief, dissolving the barrier between private and public mourning practices.5–7 Through social media we have moved from ‘sequestered death’ in private spaces to ‘mediated death’ in public spheres. 8 The analysis of social media data offers an opportunity to study expressions of grief and mourning in a naturally occurring setting, and a valuable way of understanding what, and how, people communicate about their experiences and perspectives. Much prior research in this field focuses on the role of social media in memorialisation5,6,9 and peer support, especially via closed Facebook groups.10,11 With some exceptions,12,13 relatively little is known about how bereaved people use Twitter – a unique, semi-anonymous online space. 13 During the COVID-19 pandemic, Twitter has been recognised as a rich repository of information representing public opinion, 14 but its use by people bereaved during the pandemic has not yet been examined.

Deaths from COVID-19 present unique challenges for clinicians and for patients and families towards the end of life and in bereavement.15,16 A key clinical debate is whether, and how, to facilitate family members and close friends to be present when someone dies in a hospital, hospice or care home during a pandemic. The idea of dying alone is contrary to the concept of a ‘good death’ in many cultures, 17 and not being able to say goodbye is a known risk factor for poor bereavement outcomes.15,18 However, the infectious nature of SARS-CoV-2 has complicated family participation in end-of-life care and disrupted support during bereavement. Many family members have been unable to be present at the moment of death due to infection control restrictions within hospitals and care homes. There is anecdotal evidence of variation in these restrictions, in part due to staff absence, shortages of personal protective equipment (PPE), 19 or a lack of centralised guidance. To help inform end-of-life care practices and policies, we aimed to explore how Twitter was used by people to share that a relative, friend or acquaintance had died of COVID-19 without a family member or friend present, and the views and experiences they expressed.

Methods

We analysed Twitter posts mentioning a relative, friend or acquaintance who had died alone of COVID-19. We chose Twitter to analyse user behaviour due to a pool of millions of active users, its use in sharing stories and experiences with the wider world, and its messages having a known source, audience, time stamp, and identifiable content. Twitter’s data are accessible for analysis: 280-character limit, plaintext messages (tweets) can be processed and stored easily, with access to this stream of data, including user account metadata, available through Twitter’s application programming interfaces (APIs).

The study is based on a critical realist theoretical approach 20 in which structured social relations are conceived as having objective influence on human behaviour and reality can be described with more or less accuracy. We used content analysis with the aim of presenting an accurate account of Twitter users’ posts on the site, using thematic coding and numerical counts. The research team includes experienced qualitative health researchers, a software developer, and palliative and geriatric medicine physicians. None of the Twitter users were known to the team.

Ethical approval was obtained from the Faculty of Health Sciences Research Ethics Committee at the University of Bristol (ref. 105943). Reporting follows the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR). 21

Data collection and screening

Data were collected during two complete weeks from 7th to 20th April 2020, during the peak of the first wave of the pandemic in the UK.

We used a bespoke software system to harvest publicly available tweets from Twitter. The software system we developed (using the Node.js programming language) connects to the Twitter streaming ‘statuses/filter’ API. This allows tweets that match a set of keywords to be received in real-time. This method of collecting tweets accords with Twitter’s terms and conditions, in which users consent for their information to be collected and used by third parties. 22 To develop the relevant keyword search terms we hand-searched Twitter for a sample of 30 relevant tweets and identified commonly used phrases and terms. This resulted in the search terms, limited by the 60-character limit of the Twitter API: COVID passed away, COVID grief, COVID lost, COVID died (a space=AND, comma=OR).

Both the Node.js application and the database were deployed using the Heroku software-as-a-service cloud platform. The source code is available under the Open Source Apache-2 licence for the Node.js. 23 The filtered tweets dataset was stored in a Postgres SQL database for offline analysis and subsequently exported to comma-separated-value (CSV) files. The CSV files were imported into Microsoft Excel for data filtering and deduplication: filtering was used to identify relevant and exclude irrelevant tweets. We excluded any tweets which did not include the terms: lonely, alone, isolat*, access, see, saw, goodbye or together. Deduplication removed retweeted posts. We hand-screened tweets to include only tweets referring to a relative, friend or acquaintance of the Twitter user who had died alone of COVID-19. Screening was conducted by one author (LS, RS or DC) and checked by one other. The following were excluded: tweets about people who did not die of COVID-19 or where the cause of death was not stated; media reports of a death; comments on a celebrity death; general comments on dying alone of COVID-19 not in reference to an acquaintance, friend or relative; clinicians’ tweets about patients/families as these were outside the topic of investigation.

Data analysis

We conducted a manual thematic content analysis to identify key themes and sub-themes in the data. Three members of the research team (PB, a geriatrician; LS, a social scientist; CC, a public health consultant and palliative medicine registrar) independently coded 20 tweets each and constructed draft coding frames of themes and sub-themes. These were discussed as a team and combined by LS to create a final coding frame, which was applied by DC and RS to the whole dataset in Excel and reviewed by LS. Numerical counts were made of each sub-theme. A narrative of the findings integrated illustrative tweets.

Consent

Despite Twitter data being publicly available, we considered that informed consent was required as individuals might be identifiable from their tweets. Furthermore, reporting complete Twitter posts might draw attention to groups, individuals, and trends, beyond what would normally be expected from engagement with social media platforms. 24

To illustrate study findings we identified exemplifying candidate tweets to include in full in reporting. Using a study Twitter account we contacted the candidate tweets’ authors to provide study information and request consent. If there was no response, we used up to seven reminders. Only those tweets where the user gave consent are quoted in full; other tweets are quoted only partially, paying attention to preserve anonymity, or are summarised or paraphrased. No Twitter handles are presented. This conservative approach to using Twitter data is best practice, 25 used in previous research. 26

Results

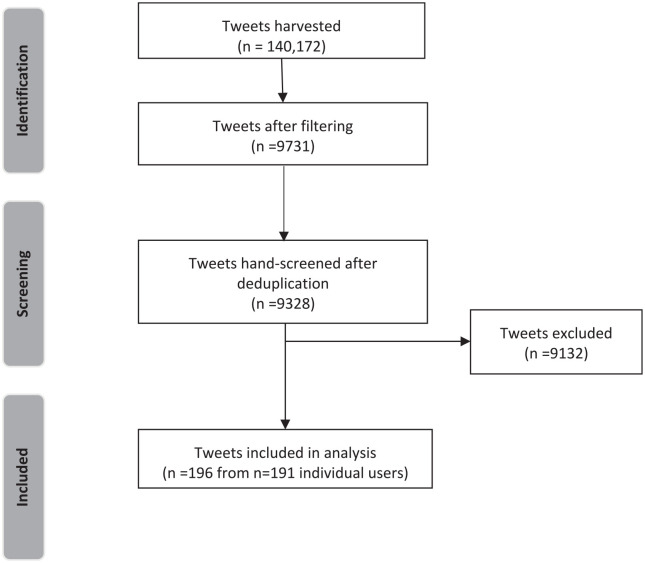

140,172 tweets were identified in 14 days. After filtering and deduplication, 9328 tweets were hand-screened (LS, DC, RS), and 196 included in the analysis, corresponding to 191 individual users (one person wrote five included tweets, one person wrote two) (Figure 1). User characteristics are summarised in Table 1. Seven bereaved family members described multiple bereavements.

Figure 1.

Flowchart (adapted from PRISMA).

Table 1.

Data characteristics (n = 196).

| Date of tweet | |

| 7–13 April 2020 | 89 |

| 14–20 April 2020 | 107 |

| User location | |

| Canada | 8 |

| France | 1 |

| Ireland | 2 |

| Jamaica | 1 |

| Netherlands | 1 |

| Philippines | 3 |

| UK | 41 |

| USA | 71 |

| Not provided/unclear | 68 |

| Deceased | |

| Father/father-in-law | 27 |

| Mother/mother-in-law | 12 |

| Uncle | 14 |

| Aunt | 13 |

| Brother/brother-in-law | 6 |

| Sister/sister-in-law | 2 |

| Cousin | 4 |

| Grandfather | 17 |

| Grandmother | 16 |

| Spouse | 2 |

| More distant relative | 13 |

| Relative’s friend | 6 |

| Friend(s) | 22 |

| Friend’s relative | 19 |

| Multiple relatives/friends | 7 |

| Relationship not stated | 16 |

| Place of death | |

| Hospital | 43 |

| Care home/nursing home/assisted living | 15 |

| Home | 6 |

| Hospice | 1 |

| Government isolation facility | 1 |

| Not stated | 130 |

We contacted 55 authors of candidate tweets. Ten gave consent to include their full tweets in study reporting, two did not consent, and 43 did not reply.

Data were coded into five main themes: restrictions, end of life, emotional impact, disrupted bereavement, and explicit function of tweet. Themes and sub-themes are presented in Table 2 with numerical counts resulting from the content analysis, which are useful to understand the relative frequency of the sub-themes in the dataset of tweets. Data extracts are tagged with a unique ID number and, where consented and available, the country of origin.

Table 2.

Content analysis – themes, sub-themes and frequency.

| Theme | Sub-theme | n |

|---|---|---|

| Restrictions | Hospital visiting restriction | 28 |

| Community visiting restriction | 11 | |

| Shielding limited visiting | 5 | |

| Travel restrictions limited visiting | 3 | |

| End of life | Died alone | 98 |

| Did not get to say goodbye | 57 | |

| Goodbyes via devices/phones | 11 | |

| Was able to visit | 8 | |

| Died with staff (holding hands) | 4 | |

| Peaceful death | 2 | |

| Emotional impact | Sadness | 95 |

| Despair/hopelessness | 59 | |

| Anger/blame | 63 | |

| Sense of injustice | 55 | |

| Shock | 21 | |

| Regret/remorse | 12 | |

| Scared/worried | 6 | |

| Gratitude for care | 4 | |

| Disrupted bereavement | Impact on after death arrangements/funeral | 25 |

| Unable to attend funeral | 13 | |

| Grieving alone | 9 | |

| Recalls a pre-COVID death | 4 | |

| Religion as a comfort | 3 | |

| Organisational support (or lack of) | 3 | |

| Explicit function of tweet | Virus containment advice to others | 33 |

| Condolences to others | 18 | |

| Tribute to deceased | 13 | |

| Rest in peace (RIP) | 8 | |

| Call for solidarity | 2 |

Restrictions

Users mentioned restrictions in four areas: hospital visiting restrictions (particularly in the ICU); community-setting visiting restrictions, mainly in nursing homes; restrictions due to the poor health or vulnerability of the bereaved; and travel restrictions. Institutional visiting restrictions were most often phrased in terms of not being ‘allowed’ to see the person who died and not being able to be present as they died, so that they ‘died alone. . . with no family’ (ID110442). Users described restrictions in care homes, where they were only able to say their goodbyes ‘standing in the garden’, through care home windows (ID49046). In hospitals, people reported ‘no visitors allowed’, leaving loved ones dying alone in ‘overwhelmed’, services (ID92278). The difficulty of such restrictions was evident:

My father died from COVID-19 Friday. I didn’t get to see him since the beginning of March because he was a resident at [name], which went on lockdown for resident safety. I received 3 calls from them. ID14718, USA

A lack of PPE was sometimes blamed:

Saddened to hear my friend’s dad died from Covid-19. He arrived at the hospital to visit his father one last time but they wouldn’t give him an n-95 mask so he couldn’t see him. ID105305, Location unknown

In other cases, the need to protect the health of the bereaved or their family members prevented contact, or travel restrictions prevented visiting. One user tweeted that their friend had been unable to see multiple family members who had died in quick succession as a household member was highly vulnerable to the effects of COVID-19. Users expressed sadness and frustration when travel restrictions both between and within countries prevented contact with loved ones (‘no way to get to him in time’ ID92278).

End of life

Users used the phrase ‘dying alone’, and this was emphasised as a particularly distressing aspect of the death and their resulting bereavement:

My cousins best friend died from COVID-19 today. This is hurting my family. Yet people still aren’t fucking social distancing and still think it’s not serious. SHE DIED ALONE. please, please stay home. ID17115, USA

Users described a ‘cruel death’ (ID30313), ‘lying in a ward. . . organs failing one by one’ (ID19514), and fear that the person who died alone was ‘confused and scared’ (ID90696), often in an alien and overwhelmed environment (‘in a packed ward’ ID68072), ‘like something out of a horror movie’ ID63684).

Two users described clinicians being present at the end of life; one described a phone call from the hospital urging them to say goodbye to their relative who ‘hasn’t got long’ and on arrival finding a nurse holding hands with their dying relative (ID76509). The opposite was also reported:

My mum died alone on a Covid ward and no-one was allowed to see her and we hear not even a nurse was with her at the end. Don’t believe all you see on MSM [mainstream media] no kind nurse was holding her hand. ID121150, Location unknown

Fifty-seven tweets referred to users being unable or deprived of the chance to say goodbye. These tweets were associated with expressions of profound sorrow and ‘heartbreak’. Views of saying goodbye via technology varied; while the opportunity was appreciated, it was also portrayed as inadequate. Two users described the use of technology in positive terms, while five described it as an unwanted alternative they had to accept (e.g. ‘had to beg just to get. . . a [video-call platform] video to say goodbye’ ID54906).

Emotional impact

The most common emotions expressed by users were sadness, despair and hopelessness: ‘Absolutely heart broken’ (ID95547), ‘My heart is torn’ (ID103608), ‘it’s so devastating’ (ID111944), ‘beyond distressing. . . agonising’ (ID26899), ‘traumatizing’ (ID139917).

Anger, frustration and a sense of injustice were also highly evident, with users directing anger at the virus itself as well as governments’ inaction or policy surrounding COVID-19 (‘#TrumpLiedPeopleDied’ ID30724). Similar emotions were levied against healthcare institutions and providers for transmitting or not diagnosing the disease:

I would love to sue them for my Dad’s death and all the other deaths not counted in the statistics. He went in with fractures after a fall. Caught pneumonia/Covid in hospital. Staff missed it. Dad died alone. My world stopped when he died. He was my hero. ID144067, Location unknown

The public was also a target for anger, criticised for not caring about others (‘a lot of you don’t give a fuck unless it impacts you or yours’ ID14243) or not following lockdown rules (‘stay the fuck home’ ID15744) or infection control restrictions:

My grand mother died of COVID thanks to people not practicing social distancing. For anyone that doesn’t follow the same orders I too hope you have to die alone with no one being able to enter the room. That’s what you deserve accountability. ID140147, Location unknown

For many, the COVID-19 death was an unexpected and shocking event. One user reported being informed in a corridor that their relative had died and immediately being sent away ‘to the car’ (ID21988). Others expressed disbelief and a sense of unreality (‘I find myself telling people as it doesn’t feel real’ ID53170).

Other emotions, identified less commonly, were regret, remorse, fear, worry, and gratitude for the care received from healthcare providers before the death; one user praised healthcare workers for putting themselves at risk to allow family members to say goodbye via video: ‘your commitment is breathtaking’ (ID142456).

Disrupted bereavement

Users described how not being able to visit the dying person was compounded by a lack of social support afterwards (‘no wake, no funeral mass, no hugging’ ID18939). Disrupted funerals and other post-death rituals were also a source of distress:

You guys have no idea how mad I am at this! I lost my fucking dad this virus stole my dad from me we didn’t get to say goodbye and we won’t be able to have a viewing because of this virus and these jackasses say it’s a lie I wish it was! [angry emojis] ID148079, Location unknown

Bereaved people expressed frustration or sadness that they had not given their relative the funeral they wanted and the dignity and respect they deserved. Adaptations to funerals using technology were described, usually as a poor substitute for live attendance: ‘we had to have a memorial over [videoconferencing platform]’ (ID52698). However, there was also appreciation for these adaptations:

My uncle died of COVID-19 on Monday. It kills us he died alone! We aren’t able to physically be together. But thank you [videoconferencing provider] for creating a virtual platform where we were able to have a vigil & continue our traditional Novena-9 days of Rosary to pray for him as a family. ID122774, USA

Inability to view the body or attend funerals due to the bereaved being clinically vulnerable and needing to self-isolate was also reported with sadness and despair (‘torture’ ID20503).

Explicit function of tweet

The most common function of a tweet was to express support for containment and social distancing measures, practicing good hygiene and using of PPE: ‘wear masks and. . . gloves’ (ID35545). They asked the public to stay at home because ‘lives are more precious’ (ID26899), and the pain of losing someone was ‘unbearable’ (ID40516). Users tweeted to express their condolences to others in similar situations to them (‘I feel your pain. . . Hang in there and I am here for you’ ID15803), as well as to pay tribute to the deceased and wish them peace:

My grandma growing up passed away due to Covid-19. It was sudden and we didn’t get a chance to say good bye and we can’t exactly mourn either. . . She was one of the kindest women I knew and loved so deeply only to die alone in a nursing home where no one spoke her native language. ID32956, USA

My husband died last week of COVID-19 and Parkinson’s. We were married 38 years. He also died alone. I’m so sorry for the loss of your beloved father. May he Rest In Peace ID15044, USA.

Other tweets reminded people to appreciate what they had (‘Hug your mom a little tighter’ ID19253), rallied people to come together (‘We’re all in this!’ ID32711) or called for political action, such as voting against a government due to its perceived mishandling of the pandemic: ‘. . .VOTE out every [politician]!’ (ID27309). Just two users directed comments at the deceased person, both expressing love (‘I’m so sorry you had to be alone. I love you.’ ID33309)

Discussion

Main findings

Twitter users who posted about a friend or family member dying of COVID-19 without a familiar person present expressed sadness, despair, hopelessness and anger about their experience and loss. Visiting restrictions due to institutional policies or a lack of PPE meant people had said goodbye to loved ones through windows or via video-conferencing technology, but overall views of these alternatives to physical presence were ambivalent. To most people, a clinician being present with their loved one at the end of life, while welcome, was little consolation. Anger, frustration and blame were mainly directed at government inaction and national, local or institutional policies, although members of the public were also blamed for not following social restrictions or taking the virus seriously enough. The sadness associated with not being able to say goodbye as they wished was compounded by a lack of social support and disrupted post-death rituals and funerals. Views of live-streamed services were mixed. A sense of political neglect or mistreatment was frequently expressed, alongside calls for action, but Twitter users also used the platform to encourage positive public health messages, express condolences to others and pay tribute to the deceased.

Strengths and weaknesses

There are potential biases related to the use of social media research.27,28 Views given on social media platforms may be exaggerated due to the anonymity of online communication, or users might post altered truths or fictitious stories for attention and ‘likes’, and so on. Many Twitter users did not share their location or the place of death, and our sample is unlikely to represent the general population. For example, people in the creative industries are over-represented among Twitter users, who also tend to be younger than the wider population. 29 Attitudes to using social media to express grief will also vary among bereaved people, with some avoiding it completely and others using it extensively.30,31 Despite these caveats, social media provides insight into feelings and perspectives among its users, and our findings provide a unique perspective on experiences of bereavement during the pandemic.

Synonyms for COVID-19, such as ‘coronavirus’, were not included in the search due to Twitter’s API 60-character limit. Different search terms might have yielded different findings. We felt it was ethical to contact Twitter users for consent to directly quote their tweets. However, as is typical for other marketing research, 32 we received a low proportion of consents. Whilst this highlights a challenge with using social media posts as data, as in other qualitive research the quoted complete tweets illustrate rather than constitute the analysis: efforts were taken to ensure the content of all the tweets included in the analysis was reflected in the narrative presented. The tweets that we did receive consent to qoute in full covered diverse themes and perspectives, although more people expressing anger in their tweets agreed to inclusion compared with those who expressed sadness, which may reflect a wish to highlight their sense of injustice. A strength of the study is the use of hand-screening to identify tweets meeting pre-specified criteria.

What this study adds

These tweets provide real-time data capturing public expressions of feelings around deaths from COVID-19. Twitter offered a public space for sharing grief, expressing support and making sense of the experiences of friends or relatives dying alone with COVID-19. Study findings highlight how Twitter facilitates sharing condolences, collective mourning and the provision of community support during the pandemic, 33 as well as its use to promote public health messaging. By allowing the expression of intense emotional states, Twitter seemed to fulfil a therapeutic function identified in prior research, 34 allowing users to experience emotional relief, for example by feeling ‘seen’ and part of a community with similar experiences. This function may be especially relevant, given the disruption of social networks during periods of lockdown and social distancing.

Our finding that Twitter was used to promote public health messaging in conjunction with expressing feelings and experiences of bereavement is novel and may be peculiar to the pandemic context. It supports a previous study that found that people use Twitter to engage in public discussions regarding death, sharing information and expressing opinions rather than solely expressing the emotional aspect of their grief. 13 As the authors note, Twitter therefore holds great potential for making public mourning a more acceptable collective activity, by bringing broader discussions surrounding death and dying back into the public sphere. 13 Unlike in that study, which analysed tweets linked to deceased Twitter users, we found less evidence of people writing messages to the person whose death they were grieving. 13 The promotion of public health messaging we identified might reflect the very human need to find meaning and purpose in bereavement. Similarly, studies of Twitter usage after extreme events such as terrorist attacks report the use of Twitter to search for meaning and value.35,36 This usage might also reflect a desire to demonstrate a specific sociopolitical orientation and align oneself with likeminded others, as previously been reported in relation to a Berlin terrorist attack. 35

This study has important implications for clinicians and policy-makers, because it demonstrates how COVID-19 deaths conflict with cultural conceptions of a ‘good’ death and after-death practices, and it can inform the development of appropriate grief interventions, both before and after a death. For example, the sense of injustice, the intensity of the anger demonstrated, and the blame directed towards individuals who weren’t complying with life-saving public health measures, are aspects of COVID-19 bereavement that need to be accommodated in a therapeutic response, and reflect emerging findings from a UK survey. 37 Anger is a common component of grief, and expressing it online might help the bereaved person cope with their emotions. However, the intense anger we identified seemed akin to that reported in studies of survivors of murder, 38 suicide 39 and other traumatic events, which may indicate the potential for high levels of prolonged grief disorder, 40 post-traumatic stress 41 and other poor bereavement outcomes among people bereaved in the first wave of COVID-19.

The cultural norms disrupted by COVID-19 include people not dying alone and loved ones being able to say goodbye, which is correlated with better adjustment in bereavement. 42 Recognising the power of these cultural narratives and the impact on family members43,44 means facilitating and optimising contact with loved ones at the end of life, even in the context of a pandemic. It is therefore crucial that end-of-life-care providers are prioritised when supplies of PPE are overstretched, so that they are able to offer in-person visits. This is contrary to practice in 2020: an international survey of hospice and palliative care services found 48% reported shortages of PPE. 20 Where an in-person meeting cannot be achieved, a meaningful goodbye 45 might still be possible, but clinicians should not assume that video-conferencing is universally desired or of benefit. Rather, clinicians should listen to family members, think creatively, and adopt a cautious and individualised approach to the use of technology.33,46 Personal, meaningful and supportive funerals may also still be possible despite restrictions.47,48 Policy makers should consider early provision of clear, central guidance to reduce unwarranted variation for visiting loved ones in a terminal phase. In the UK, government guidance devolved responsibility for visiting to local decision makers, suggesting use of risk-based assessments to determine access, but provided little guidance on how this should be delivered.49,50 This may have left staff feeling unsupported, ultimately enforcing inconsistent restrictions on relatives, with lasting tragic consequences. Finally, given the profound distress evident in these accounts of bereavement after a death from COVID-19, signposting to bereavement services and identifying and supporting those at particular risk of poor outcomes18,51 is crucial.

The emotional toll expressed in these tweets warrants further investigation to understand the immediate and longer term impacts of grief in a pandemic. Research currently underway will help fully understand these impacts.52,38 In-depth qualitative research is needed to explore how people use social media when bereaved and the role of social media in providing a sense of connection and peer-to-peer support in a time of collective mourning and disrupted social networks. Finally, further research is needed to explore the role of social media in creating a sense-making narrative, reflecting and enforcing cultural ideas about death and bereavement, 53 and to develop and agree a ‘good conduct’ guide for social science researchers accessing Twitter.

Conclusions

This paper highlights an historic conjunction of a global pandemic with a new era of unprecedented online connectivity. Millions of people have lost loved ones during the pandemic and been personally affected by infection control measures. At the same time, modern video messaging, social-media platforms and online discourse have amplified the ability to express emotion and grieve. Had this pandemic occurred even a decade ago, the possibilities for personal expression would have been fewer. Twitter users in April 2020 shared the sadness, despair and anger resulting from their loved ones dying alone and the impossibility of properly comforting the dying at the end of their life. These sentiments were compounded by disruption to desired funeral practices and a lack of social support. Twitter was used for collective grieving and support as well as to promote public health messaging. These findings highlight the need for care providers and policy-makers to facilitate and optimise contact with patients at the end of life through clear guidance and PPE allocation, and to ensure adequate signposting and support for bereaved people.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Clause, Inc. for donating the computer resources to collect, filter and store the Twitter data used in this study, and all those who consented to the inclusion of their full Tweet in this study report.

Footnotes

Authorship: PB, CC and LS conceived the study and designed the study protocol. MT commented on the protocol. PB, CC, LS RS and DC analysed the study data; RS sought approval from study participants. DS designed and ran the software programme to collect the data. All authors contributed to drafting the paper, revised the paper and approved the final version. LS obtained ethical approval, oversaw data collection, led the analysis and reporting and is the guarantor.

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethics and consent: Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Faculty of Health Sciences Research Ethics Committee at the University of Bristol (ref. 105943).

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: LS and RS are funded by a Career Development Fellowship from the National Institute for Health Research. PB is funded by Research Capability Funding from North Bristol NHS Trust.

Data management and sharing: As Twitter users do not necessarily consent to the use of their tweets in research and are potentially identifiable from their tweets, it is not ethical to provide access to the dataset used in this analysis. However, the source code is available 24 under the Open Source Apache-2 license for the Node.js application and details of the search terms and filtering are reported in the paper.

ORCID iD: Lucy E Selman  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5747-2699

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5747-2699

References

- 1. World Health Organisation. WHO coronavirus disease (COVID-19) Dashboard, https://covid19.who.int/ (2021, accessed 20/01/2021).

- 2. Verdery AM, Smith-Greenaway E, Margolis R, et al. Tracking the reach of COVID-19 kin loss with a bereavement multiplier applied to the United States. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2020; 117: 17695–17701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Koffman J, Gross J, Etkind SN, et al. Clinical uncertainty and Covid-19: embrace the questions and find solutions. Palliat Med 2020; 34: 829–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. OECD. Internet access (indicator), 10.1787/69c2b997-en (2021, accessed 11 May 2021). [DOI]

- 5. Carroll B, Landry K. Logging on and letting out: using online social networks to grieve and to mourn. Bull Sci Technol Soc 2010; 30: 341–349. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brubaker JR, Hayes GR, Dourish P. Beyond the grave: Facebook as a site for the expansion of death and mourning. Informat Soc 2013; 29: 152–163. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Walter T, Hourizi R, Moncur W, et al. Does the internet change how we die and mourn? Overview and analysis. OMEGA J Death Dying 2012; 64: 275–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gibson M. Death and mourning in technologically mediated culture. Health Sociol Rev 2007; 16: 415–424. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Marwick A, Ellison NB. “There Isn’t Wifi in Heaven!” negotiating visibility on Facebook memorial pages. J Broadcast Electron Media 2012; 56: 378–400. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hollander EM. Cyber community in the valley of the shadow of death. J Loss Trauma 2001; 6: 135–146. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hård Af, Segerstad Y, Kasperowski D. A community for grieving: affordances of social media for support of bereaved parents. New Rev Hypermed Multimed 2015; 21: 25–41. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Patton DU, MacBeth J, Schoenebeck S, et al. Accommodating grief on Twitter: an analysis of expressions of grief among gang involved youth on Twitter using qualitative analysis and natural language processing. Biomed Inform Insights 2018; 10: 1178222618763155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cesare N, Branstad J. Mourning and memory in the twittersphere. Mortality 2018; 23: 82–97. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chen E, Lerman K, Ferrara E. Tracking social media discourse about the COVID-19 pandemic: development of a public coronavirus Twitter data set. JMIR Public Health Surveill 2020; 6: e19273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Selman LE, Chao D, Sowden R, et al. Bereavement support on the frontline of COVID-19: recommendations for hospital clinicians. J Pain Symptom Manage 2020; 60: e81–e86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Eisma MC, Tamminga A, Smid GE, et al. Acute grief after deaths due to COVID-19, natural causes and unnatural causes: an empirical comparison. J Affect Disord 2021; 278: 54–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Caswell G, O’Connor M. Agency in the context of social death: dying alone at home. Contemp Social Sci 2015; 10: 249–261. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kentish-Barnes N, Chaize M, Seegers V, et al. Complicated grief after death of a relative in the intensive care unit. Eur Respir J 2015; 45: 1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Oluyase A, Hocaoglu M, Cripps R, et al. The challenges of caring for people dying from COVID-19: a multinational, observational study of palliative and hospice services (CovPall). J Pain Symptom Manage. Epub ahead of print 5 February 2021. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2021.01.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Archer MS, Bhaskar R, Collier A, et al. Critical realism: essential readings. London: Routledge, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 21. O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, et al. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med 2014; 89: 1245–1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Twitter. Twitter privacy policy, https://twitter.com/en/privacy (accessed 08 October 2020).

- 23. Selman D. Tweet Saver. Github2020. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ahmed W, Bath PA, Demartini G. Using Twitter as a data source: an overview of ethical, legal, and methodological challenges. In: Woodfield K. (ed.) The ethics of online research. Bingley, UK: Emerald Publishing Limited, 2017, pp.79–107. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Williams ML, Burnap P, Sloan L. Towards an ethical framework for publishing Twitter data in social research: taking into account users’ views, online context and algorithmic estimation. Sociology 2017; 51: 1149–1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ranco G, Aleksovski D, Caldarelli G, et al. The effects of Twitter sentiment on stock price returns. PLoS One 2015; 10: e0138441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Beninger K, Fry A, Jago N, et al. Research using social media; users’ views. 2014. London: NatCen Social Research. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hopewell-Kelly N, Baillie J, Sivell S, et al. Palliative care research centre’s move into social media: constructing a framework for ethical research, a consensus paper. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2019; 9: 219–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sloan L, Morgan J, Burnap P, et al. Who tweets? Deriving the demographic characteristics of age, occupation and social class from Twitter user meta-data. PLoS One 2015; 10: e0115545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hjorth L, Kim K-hY. The mourning after: A case study of social media in the 3.11 earthquake disaster in Japan. Television New Media 2011; 12: 552–559. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Varga MA, Varga M. Grieving college students use of social media. Illness Crisis Loss. Epub ahead of print 3 February 2019. DOI: 10.1177/1054137319827426. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hikmet N, Chen SK. An investigation into low mail survey response rates of information technology users in health care organizations. Int J Med Inform 2003; 72: 29–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pattison N. End-of-life decisions and care in the midst of a global coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Intens Crit Care Nurs 2020; 58: 102862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Barak A. The psychological role of the Internet in mass disasters: past evidence and future planning. In: Brunet A, Ashbaugh AR, Herbert CF. (eds.) Internet use in the aftermath of trauma. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: IOS Press, 2010, pp.23–43. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Fischer-Preßler D, Schwemmer C, Fischbach K. Collective sense-making in times of crisis: connecting terror management theory with Twitter user reactions to the Berlin terrorist attack. Comput Human Behav 2019; 100: 138–151. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Stieglitz S, Bunker D, Mirbabaie M, et al. Sense-making in social media during extreme events. J Contingen Crisis Manage 2018; 26: 4–15. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Harrop E, Farnell DJJ, Longo M, et al. Supporting people bereaved during COVID-19. Study Report 1. 27 November 2020. Cardiff, Wales: Cardiff University. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Boelen PA, van Denderen M, de Keijser J. Prolonged grief, posttraumatic stress, anger, and revenge phenomena following homicidal loss: the role of negative cognitions and avoidance behaviors. Homic Stud 2016; 20: 177–195. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tal Young I, Iglewicz A, Glorioso D, et al. Suicide bereavement and complicated grief. Dialog Clin Neurosci 2012; 14: 177–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Boelen PA, Lenferink LIM, Nickerson A, et al. Evaluation of the factor structure, prevalence, and validity of disturbed grief in DSM-5 and ICD-11. J Affect Disord 2018; 240: 79–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Power MJ, Fyvie C. The role of emotion in PTSD: two preliminary studies. Behav Cognit Psychother 2013; 41: 162–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kissane DW, Bloch S, McKenzie DP. Family coping and bereavement outcome. Palliat Med 1997; 11: 191–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Anderson-Shaw LK, Zar FA. COVID-19, moral conflict, distress, and dying alone. J Bioethic Inquiry 2020; 17: 777–782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wakam GK, Montgomery JR, Biesterveld BE, et al. Not dying alone—modern compassionate care in the Covid-19 pandemic. New Engl J Med 2020; 382: e88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Otani H, Yoshida S, Morita T, et al. Meaningful communication before death, but not present at the time of death itself, is associated with better outcomes on measures of depression and complicated grief among bereaved family members of cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage 2017; 54: 273–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Fusi-Schmidhauser T, Preston NJ, Keller N, et al. Conservative management of Covid-19 patients—emergency palliative care in action. J Pain Symptom Manage 2020; 60: E27–E30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Burrell A, Selman LE. How do funeral practices impact bereaved relatives’ mental health, grief and bereavement? A mixed methods review with implications for COVID-19. OMEGA J Death Dying. Epub ahead of print 8 July 2020. DOI: 10.1177/0030222820941296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bear L, Simpson N, Angland M, et al. ‘A Good Death’, during the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK: a report of key findings and recommendations. London: LSE Anthropology, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 49. NHS England and NHS Improvement. Visiting healthcare inpatient settings during the COVID-19 pandemic. London: NHS, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 50. NHS England and NHS Improvement. Clinical guide for supporting compassionate visiting arrangements for those receiving care at the end of life. London: NHS, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Harrop E, Mann M, Semedo L, et al. What elements of a systems’ approach to bereavement are most effective in times of mass bereavement? A narrative systematic review with lessons for COVID-19. Palliat Med 2020; 34: 1165–1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Covid Bereavement. Grief experience and support needs of people bereaved during the COVID-19 pandemic, https://www.covidbereavement.com/ (2020, accessed 14 January 2021).

- 53. Hanusch F. Representing death in the news: Journalism, media and mortality. London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010. [Google Scholar]