Abstract

Background

This study aimed to systematically review, appraise, and synthesize the current evidence on the experiences and needs encountered by informal caregiver of patients with glioma throughout the disease trajectory and to provide a set of practical implications for health professionals.

Methods

Seven English databases and four Chinese databases were searched in this systematic review and meta-analysis. Additional manual searches were completed to identify primary studies, with the language limited by English and Chinese. The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal Checklist for Qualitative Research was used to appraise the methodological quality of each study.

Results

The systematic review included 16 papers that yielded 71 findings and 6 categories. Finally, 2 synthesized findings were extracted: (I) role transition of caregivers for glioma patients throughout the disease trajectory; (II) support and information need by caregivers of glioma patients. Accordingly, there is a need to recognize the importance of permanent and tailored support for caregivers by providing accurate, practical, and evidence-based information.

Discussion

This is the first attempt to systematically evaluate the breadth and quality of the literature concerning the experiences of caregivers with glioma patients. The results generated from the review may shed some light on problems encountered by glioma patients and their families. A limitation of this review is that in most selected studies, the reflexivity of interviewees is not addressed, which may influence the interpretation of the findings. Moreover, the selected studies were reported in English or Chinese, therefore, caution is needed in interpreting the results.

Keywords: Glioma, informal caregivers, qualitative research, systematic review, the Transtheoretical Model (TTM)

Introduction

The globe records more than 250,000 new cases of primary malignant brain tumors each year, 77% of which are gliomas (1). The World Health Organization has a grading system for a few select tumors of the central nervous system (2). Based on their histology and isocitrate dehydrogenase status, gliomas can be divided into 4 grades, with grades I and II being low grade, and grades III and IV being high gliomas. The latter is also known as malignant gliomas inclusive of anaplastic glioma (anaplastic oligodendroglioma, anaplastic astrocytoma, and anaplastic oligoastrocytoma) and glioblastoma. As one of the most common forms of primary brain tumors in adults, the estimated annual incidence of glioma ranges from 6.6 to 7.1 per 100,000 individuals (3). Glioma may develop at any age; however, the occurrence reaches the apex in fifty- and sixty-year-old individuals life (4). Although relatively rare, gliomas are life-threatening tumors with poor prognosis. Therefore, the reported 5-year survival rate of patients with glioblastoma is approximately 5% (5). The median survival of patients who are in receipt of a new diagnosis of this malady ranges from less than 1 year to 3 years, with an average span of 12–14 months (6). Therapeutic targeting of this condition entails surgical resection with ensuing adjuvant radiation and chemotherapy (7,8).

Despite advances in medical care, both the treatment and the disease itself can cause severe damage to patients, who must then cope with concomitant devitalizing manifestations inclusive of cognitive and functional decline, seizures, falls, and personality alterations, all of which are well-documented in the existing literature (9-12). Meanwhile, due to the many issues at physical, emotional and social levels encountered by patients, caregivers necessitate an immense amount of supportive care (13) that is rarely necessarily for other cancers (14,15). Literature employs the interchangeable usage of the words carer, informal caregiver, and caregiver; these terms specifically refer to those who provide unpaid care at home to a person while simultaneously playing an important role in the outpatient setting for the chronically ill and cancer patients (16). Informal caregivers are non-professional people, they provide emotional support and assistance in activities of daily living, health-related tasks, and financial management, they served as an extension of the health-care system to take care of the patients at home setting. Considering this, research involving the caregivers’ experience with glioma patients has recently increased, with qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methodology designs being used. Given the nature of qualitative research, the unique experience associated with the care of a glioma patient can be understood better through a qualitative approach.

Nevertheless, many studies have examined patients’ experiences from different perspectives, as it is impossible to establish a comprehensive understanding of the unique experiences from a single study. For instance, in Whisenant’s (17) report, the researchers interviewed 20 caregivers with patients of glioma, they concluded with several themes: commitment, expectation management, role negotiation, self-care, new insight, and role support. However, not too much attention has been drawn on the aspect of information support, which is frequently reported in other types of cancer (15,16).

Thus, the present study aimed to systematically review, appraise, and synthesize the current evidence and provide a set of practical implications for healthcare professionals to gain a deeper understanding of the growing evidence of experiences of caregivers of glioma patients.

We present the following article in accordance with the PRISMA reporting checklist (available at https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/atm-21-2761).

Methods

This systematic review was designed as a qualitative meta-synthesis based on guidelines from the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) (18). The review is registered with the PROSPERO International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (registration number CRD42020222307).

Search strategy

Searches on the MEDLINE, Embase, Web of Science, PsycINFO, CINAHL, Cochrane Library, Scopus, databases were conducted. Relevant Chinese databases, including the China National Knowledge Infrastructure, China Science and Technology Journal Database, Wanfang Database, and Chinese Biomedicine Literature Database were also searched. There were no restrictions regarding the publication period. Reference lists and citations were manually searched to identify further studies. Only literature published in English or Chinese language was considered. The search was conducted on November 23, 2020. Appendix 1 shows the Cochrane library search strategy.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria

Population

The study comprised the opinions and experiences of caregivers for patients with glioma during hospitalization or after discharge, including those of spouses, parents, adult children, friends, and relatives. Participants were required to be age 18 years and older, capable of providing informed consent, and able to communicate verbally. For qualitative studies of patients and caregivers conducted together, separately described articles were also included.

Phenomena of interest

Study focus could include the responsibilities of the caregiver, life changes, challenges, experiences, needs, attitudes, coping strategies, etc.

Context

The context considered was entire process of caregiving for patients with glioma during hospitalization or after discharge in either the inpatient or outpatient settings.

Design

A qualitative research design was applied, including but not limited to phenomenology, grounded theory, ethnography, and narrative approaches. Mixed research containing qualitative methods was also included.

Exclusion criteria

The following literature types were excluded: duplicate studies, abstracts, those lacking full availability; reviews and clinical information articles; studies published in languages other than Chinese or English; research on child cancer survivors; and research focusing on only palliative care.

Data extraction

The JBI qualitative data extraction tool was employed (Appendix 2). The extracted data included specific details about the author, geographic location, setting, participants, objectives, patients’ glioma types, interview time and place, phase in the disease trajectory, and key findings. The term “disease trajectory” for glioma patients starts from the diagnosis of glioma to the point of end-of-life according to previous research (19). If the included study had a mixed method study design, only qualitative findings were analyzed. Additionally, although some studies had described the experience of caregivers for several types of brain tumor, only the findings of caregivers related to glioma were included.

Assessment of methodological quality

The JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Qualitative Research (20) was employed to appraise the methodological quality of each study (Appendix 3). Two researchers appraised the articles independently, and disagreements were discussed with a third researcher until a consensus was reached.

Data synthesis

The JBI meta-aggregation approach was used for the synthesis of evidence (18). Meta aggregation involves a 3-step process beginning with extraction of all findings from all included papers, developing categories, and extracting 1 or more synthesized findings from at least 2 categories. Two researchers conducted the process independently to achieve consistency of each synthesized finding.

Results

Study inclusion

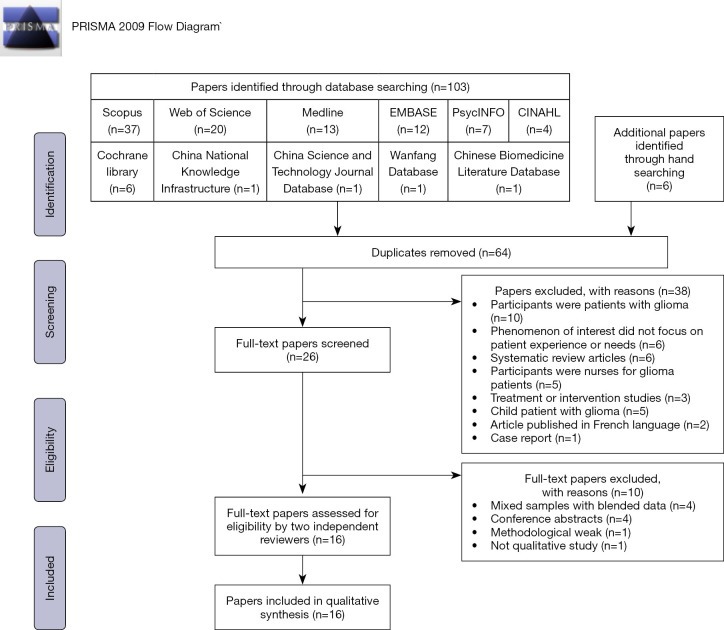

The PRISMA flow diagram shows the process of study selection (Figure 1). Ultimately, 16 papers were selected for qualitative systematic review after the methodological quality was assessed.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of literature search and study selection.

Methodological quality

Based on the JBI critical appraisal checklist, the overall methodological quality of the 16 included studies was moderate to strong: 3 studies were rated as strong (10/10 score), 6 as high (9/10 score), and 7 as moderate (7–8/10 score). These results are listed in Table 1. The studies included for this review were of relatively remarkable quality, which translated to a lower risk of bias.

Table 1. Critical appraisal of studies using the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) qualitative appraisal tool.

| Study | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 | Total score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whisenant 2011, (17) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 10 |

| Arber 2013, (21) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | 9 |

| Cavers 2013, (22) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | U | Y | Y | Y | 8 |

| Collins 2014, (23) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | N | Y | Y | Y | 8 |

| Coolbrandt 2015, (24) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 10 |

| Edvardsson 2008, (25) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | 9 |

| Heckel 2018, (26) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | 9 |

| McConigley 2010, (27) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | 8 |

| Ownsworth 2015, (28) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 10 |

| Piil 2018, (29) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | 7 |

| Sacher 2018, (30) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | U | Y | Y | Y | 8 |

| Salander 1996, (31) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | 8 |

| Schmer 2008, (32) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | 8 |

| Tastan 2011, (33) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | 9 |

| Wasner 2013, (34) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | 9 |

| Wideheim 2002, (35) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | 9 |

| Total % | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 44 | 38 | 94 | 100 | 100 | – |

Y, yes; N, no; U, unclear; N/A, not applicable. Q1, philosophical perspective and the research methodology; Q2, research question; Q3, the methods employed for data collection; Q4, the representation and analysis of data; Q5, the interpretation of results; Q6, research culturally; Q7, the influence of the researcher, and vice-versa, addressed; Q8, participants adequately represented; Q9, ethics of the research; Q10, the degree to which study conclusions flow from the analysis or interpretation of the data.

Characteristics of included studies

This systematic review included 16 qualitative studies, published between 1996 and 2018 across 9 countries. The sample size of the studies ranged from 5 to 45 with a total of 334 participants. Qualitative research methods, such as phenomenological approach, grounded theory, descriptive exploratory method, story theory, and narrative mindreading were applied to portray the role of informal caregivers for patients with glioma, along with their experiences and attitudes, throughout the disease trajectory. These features are demonstrated in Table 2.

Table 2. Characteristics of included studies.

| Author | Settings | Samples | Methods | Objectives | Patient with glioma | Interview time and place | Phase in the disease trajectory | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whisenant (17), 2011 | National Cancer Institute-designated comprehensive cancer center, USA | 20 caregivers (14 spouses, 1 parent, 1 child, 4 others); 12 males and 8 females | Descriptive exploratory method and story theory | To scrutinize population-specific caregiving experience themes via experiences of informal caregivers of primary brain tumor patients | Grade II–IV primary brain glioma | At outpatient/inpatient areas and private rooms | Diagnosed with PMBT between less than 1 year to more than 5 years |

1. Commitment |

| 2. Managing expectations | ||||||||

| 3. Role negotiation | ||||||||

| 4. Self-care | ||||||||

| 5. Novel perception | ||||||||

| 6. Role support | ||||||||

| Arber (21), 2013 | Cancer center in the south east of the England, UK | 22 caregivers (12 female partners, 5 male partners, 2 daughters, 1 son, 1 mother, and 1 father); 7 males and 15 females | constructivist grounded theory and open-ended approach interviews | To scrutinize primary malignant brain tumor patients’ family caregivers’ experiences | Primary malignant brain tumor (glioblastoma, multiforme, ependymoma, oligodendroglioma and astrocytoma) | Not mentioned | With a diagnosis of brain tumor | The core concept was “Connecting on the caring journey” with the following themes: |

| 1. Fostering supportive relationships | ||||||||

| 2. Places with safety comfort | ||||||||

| 3. Barriers of support connection | ||||||||

| Cavers (22), 2013 | Regional neuro-surgical center, UK | 23 relatives (8 husbands, 11 wives, 3 parents, 1 daughter); 10 males and 13 females | Grounded theory and in-depth qualitative interviews | To comprehend factors impacting the adjusting process to glioma diagnosis | High and low grade gliomas | Home and hospital; around 1 hour | Four times: prior to official diagnosis; at commencement of therapy; on completion of treatment; 6 months subsequent to treatment; and following mourning | 1. Anguish, anxiety and distress prior to and from diagnosis |

| 2. Information preference disparity | ||||||||

| 3. Vital involvement of hope, reassurance, and support | ||||||||

| Collins (23), 2014 | Two metropolitan hospitals, including neurosurgery, oncology and palliative care, Australia | 23 caregivers (17 spouses, 4 children, 2 others); 9 males and 14 females | Grounded Theory and in-depth interviews | To comprehend the setting-based supportive and palliative care requirements, with explicit focus upon care at the end-of-life phase | PMG grades III–IV | 7 home; 9 hospitals; 4 hospices; 3 by telephone | 15 current and 8 bereaved; patient survival was between 1 month and 14 years (median 14 months) | 1. The trials of caring |

| 2. Caregivers facing a paucity of support available to them | ||||||||

| 3. The suffering of caring | ||||||||

| Coolbrandt (24), 2015 | The oncology wards of the University Hospitals Leuven, Belgium | 16 caregivers (13 spouses, 2 parents, 1 friend); 6 males and 10 females | Grounded theory and semi-structured interviews | To scrutinize the HGG patients’ caregivers (family) and their requisites concerning professional care | HGG | 7 hospital, 9 home; 78 minutes on average (range from 46 to 126 minutes) | Treated with chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy or in the follow-up phase after treatment | 1. Finding oneself being lost and alone in a new life |

| 2. Committed but struggling to care | ||||||||

| 3. Caring needs | ||||||||

| Edvardsson (25), 2008 | Sweden | 28 caregivers (15 spouses or cohabitants, 3 live-apart partners, 8 parents, 1 adult child, 1 sibling); 8 males and 20 females | Semi-structured interview | To scrutinize different themes across the family via qualitative analysis | 25 low-grade gliomas and 2 grade III gliomas | Place and time chosen in agreement with the interviewer | Not mentioned | 1. Tremendously stressful emotions |

| 2. Being ignored and invisible | ||||||||

| 3. Altered roles and relations | ||||||||

| 4. Boosting strength in everyday life | ||||||||

| Heckel (26), 2018 | The Regional Cancer Centre and the hospital information system of 7 departments of a university hospital, Germany | 17 caregivers (10 spouse, 7 children); 5 males and 12 females | Semi-structured face-to-face interviews | To ascertain and contrast variations across informal caregivers of brain tumor patients vs. non-brain tumor patients in terms of needs, personal experiences, and perceived burdens | Glioblastoma WHO grade III or IV | Palliative medicine, home; on average 95.96 minutes (min: 40; max: 211) | Patient died | 1. Situation consideration |

| 2. Facing the situation | ||||||||

| 3. Impacts of the situation | ||||||||

| 4. Others’ support | ||||||||

| 5. Information | ||||||||

| 6. Perception by others | ||||||||

| McConigley (27), 2010 | The medical oncology department of a tertiary referral center for neurological cancers, Australia | 21 caregivers (20 spouses, 1 parent); 4 males and 17 females | Grounded theory and semi-structured interviews | To convey high-grade glioma patients’ family caregiver experiences regarding their information and requisite support | Malignant HGGs (astrocytoma grade 3–4, n=3; glioblastoma multiforme, n=18) | Not mentioned | 6–8 weeks postdiagnosis (7 participants), 5–6 months postdiagnosis (7 participants), 9–12 months postdiagnosis (7 participants) | A time of rapid change with 2 subthemes: |

| 1. Renegotiating relationships | ||||||||

| 2. Learning to be a caregiver | ||||||||

| Ownsworth (28), 2015 | The Cancer Council Queensland or a private neurosurgery clinic, Australia | 11 caregivers (8 spouses, 1 father, 2 mothers); 6 males and 5 females | Phenomenological approach and in-depth semi-structured interview | To scrutinize the impact of brain tumor on support and relationship shifts of family caregivers | Grade I–II tumors (n=6); grade III–IV tumors (n=5) | 10 caregivers’ homes, 1 telephone interview; 51 minutes (range, 27–88 minutes) | Between 9 months and 22 years post diagnosis | 1. Meanings of support: requisite intertwined and distinct support, altered support expectations, and factors impacting these expectations |

| 2. Relationship impacts: the experience of strengthened, maintained, or strained relations | ||||||||

| Piil (29), 2018 | The Department of Neurosurgery, Rigshospitalet, University of Copenhagen, Denmark | 33 caregivers (25 spouses/partners, 7 children, 1 sibling) | Semi-structured telephone interviews | To longitudinally ascertain the explicit preferences and requirements for care, support, and rehabilitation along with their link to psychological aspects, physical activity, and health quality across the first year post- HGG diagnosis in patients and their caregivers to encompass qualitative and quantitative aspects | Malignant glioma | 13–25 minutes | At 5 fixed time-points across a disease and treatment trajectory over 1 year: baseline, week 6, week 28, week 40, and week 52 | 1. Individual approach to get prognosis-based data for either seeking or limiting the amount and content of prognostic information |

| 2. The shared hope of patients and their caregivers with the solidarity of the latter with the former | ||||||||

| 3. Patients and caregivers working towards a healthier lifestyle | ||||||||

| 4. Role transition from family member to caregiver | ||||||||

| Sacher (30), 2018 | The Neurooncological Outpatient Division, Department of Neurosurgery, University Hospital of Leipzig, Germany | 45 caregivers (31 spouses/partner, 9 parents, 5 children); 12 males and 33 females | Semi-structured interviews | To ascertain the sociodemographic, clinical and personality factors that impact the quality of life of patients and their caregivers and employ standardized and qualitative approaches to scrutinize for a reciprocal impact of their coping, distress, mood, and well-being | Anaplastic astrocytoma grade III (n=16), glioblastoma grade IV (n=29) | 15–20 minutes | The median interval from cancer diagnosis was 12 months | 1. Daily life alterations and diagnosis |

| 2. Dependency and restrained freedom | ||||||||

| 3. Altered roles and relationships | ||||||||

| 4. Sources of power in everyday life | ||||||||

| Salander (31), 1996 | Sweden | 24 spouses; 7 males and 17 females | Grounded theory | To scrutinize the emotional and cognitive handling in malignant brain tumor patients’ spouses | Grade III or Grade IV malignant glioma | Home and hospital | Four times: be discharge from the neurosurgical ward; 2 months later, when the patient’s 6 weeks of radiation therapy had been completed; 5 months later at home when patients and caregivers were likely to encounter problems; about a month after the patient had died | 1. A crisis delayed until disease advancement |

| 2. A high-priority crisis | ||||||||

| 3. A crisis delayed until homecoming of the patient | ||||||||

| Schmer (32), 2008 | An urban midwestern city, USA | 10 caregivers (7 spouses, 2 daughters, 1 son-in-law) | Phenomenological approach and semi-structured interviews | To explore the impacts on caregivers’ lives when caring for a brain tumor-afflicted family member | Malignant brain tumor | Conducted at a private conference room away from the treatment area; 42 minutes (range, 35–90 minutes) | Within the initial 6 months of treatment | 1. The shock of brain diagnosis |

| 2. Instantaneous alterations in family roles | ||||||||

| 3. Psychosocial effects on the patient, the caregiver, and family | ||||||||

| Tastan (33), 2011 | The neurosurgery department of a military training and research hospital, Turkey | 10 patients’ relatives (4 spouses, 4 offspring, 1 parent, 1 sibling) | Phenomenological approach and semi-structured interviews | To ascertain and to categorize patient relatives’ experiences over the perioperative period and home care | Glioblastoma(n=4) astrocytoma (n=3), schwannoma (n=1), oligodendroglioma (n=1), and pituitary adenoma (n=1) | 30–45 minutes | The surgery was at least 3 months prior to the study period (3–6 months) | Three categories and 9 themes: |

| (a) Personal feelings | ||||||||

| 1. Foremost reactions: shock and terror of death | ||||||||

| 2. Surgery choice: helplessness or acquiescence | ||||||||

| 3. First meeting post- surgery: joy or trepidation | ||||||||

| 4. Uncertainty and angst | ||||||||

| (b) Change management of: | ||||||||

| 5. Tumor side effects | ||||||||

| 6. Behavior and roles | ||||||||

| 7. Home care | ||||||||

| 8. Social support | ||||||||

| (c) 9. Requisite knowledge to handle the malady | ||||||||

| Wasner (34), 2013 | The neuro-oncological outpatient clinic and the palliative care unit at a university hospital in Germany | 27 caregivers (19 spouses, 3 parents, 4 children, 1 friend) | Narrative mindreading and semi-structured interviews | A personal experience-based approach to examine quality of life, burden of caring, and psychological health of caregivers of PMBT patients | Astrocytoma WHO grade III, glioblastoma | Patients’ private rooms or in a meeting room; 20–60 minutes | PMBT between 1 and 59 months prior to the study | 1. Psychological distress and burden of care |

| 2. Taking responsibility | ||||||||

| 3. Recognizing the significant role of PMBT caregiver | ||||||||

| 4. Need for solid and continuous support | ||||||||

| 5. Practical advice and help | ||||||||

| Wideheim (35), 2002 | A neurology clinic, Sweden | 5 next of kin (2 partners, 2 parents, 1 adult child) | Descriptive prospective interview study | To describe what it like to live with a family member with a highly malignant brain tumor | Highly malignant glioma (grade III and IV) | Not mentioned | Twice: 2–3 weeks after surgery and 3 and 6 months after onset |

(a) How the families felt post-disease onset and receiving diagnosis: |

| 1. Deviant behavior of the patient | ||||||||

| 2. Distancing | ||||||||

| 3. Recognition of death | ||||||||

| (b) Families’ experiences of daily life: | ||||||||

| 4. Fear and anxiety | ||||||||

| 5. Burden | ||||||||

| 6. Support | ||||||||

| 7. Return to a normal life | ||||||||

| 8. Hope | ||||||||

| 9. Preventing illness | ||||||||

| 10. Learning to cope with the grief | ||||||||

| (c) Families’ experiences concerning the association with care staff and information: | ||||||||

| 11. Encounter with staff | ||||||||

| 12. Information |

HGG, high-grade glioma; WHO, World Health Organization; PMG, primary malignant glioma; PMBT, primary malignant brain tumor.

Findings of the review

The systematic review included 16 papers that yielded 72 findings and 6 categories. Lastly, 2 synthesized findings were extracted (Appendix 4):

Role transition of caregivers for glioma patients during their disease trajectory;

Support and information need by caregivers of glioma patients.

Synthesized finding 1: role transition of caregivers for glioma patients during the disease trajectory

When patients were diagnosed with glioma, their family member began to take the role of caregiver. This role transition was a dynamic process and transformed their psychology and behavior during the disease trajectory. Caregivers experienced a difficult journey that began with a shock at the time of diagnosis, leading to an immediate change in family relationships, and then learned to cope with the disease and share hope with patients.

Category 1: emotional roller coaster: psychological distress caused by the disease and the altered behavior of the patient

Beginning from the initial stage of the disease at diagnosis, caregivers’ emotional reaction changed with the patient’s psychological status. Many caregivers and patients had no idea about the course that their illness might take and could only wait. They felt extremely distressed with the occurrence of any unexpected event especially during the prediagnosis stage (22).

Upon learning about the diagnosis, the caregivers reported feeling a sense of shock accompanied by disbelief and powerlessness, which lingered in their experience of dealing with the disease. Thereafter, they had to deal with a second shock when the doctor informed them about the limited expected survival time.

A caregiver explained that as “a particular patient was reiterating the same question frequently, alcoholism was suspected. The brain tumor diagnosis post-scan emerged as a shock” (Schmer 2008).

After the emotional turmoil, they faced a period of uncertainty, accented by anxiety, worry, fear, anger, and distress. They dealt with difficult physical and cognitive symptoms, such as patients’ memory loss and communication issues of patients.

“The old self of the person is only fleeting with an overall change and a sense of loss already” (Collins 2014).

After the diagnosis of the disease, many patients could not return to their work due to reduced physical capacity. Therefore, they became passive toward life and dependent on caregivers. They also faced a disruption in family life links and the approach of death.

“The impending loss of life at the crossroads of life led to insomnia in the couple with the caregiver dreading the loss” (Tastan 2011).

With time, caregivers experienced suffering, acceptance, and feeling lost and lonely because of an uncertain future.

“The experience was akin to walking through a tunnel with the loss of a conspicuous section of the world” (Coolbrandt 2015).

Category 2: role negotiation: the change in the family roles of caregivers

The original family relationship between caregivers and patients was broken, and there was the adaptation by caregivers to a new relationship that was evidently atypical. Further, when the change occurred, they were astounded by its quantity and depth. Among all the relationship factors, the mutuality of the marital relationship shared by spouses was severely affected.

“The stark variation in the relationship is on the lines of the loss of equality and the partner with no return to the past making it the hardest” (Schmer 2008).

Due to the intellectual and physical decline of patients, caregivers suffered from limited freedom. They preferred not to be away from home, which prevented them from travelling or even going to work. Meanwhile, they had to take on many new responsibilities such as deciding about treatment, providing financial support, and others. They always persisted in prioritizing the patients’ needs above their own and showed their absolute commitment to providing limitless care.

“There was part-time work as opposed to the earlier full time job to stay with the patient” (Mcconigley 2010).

Category 3: role growth: the self-efficacy results from emotional bondage and responsibility

Seeing their beloved family member suffer from illness, caregivers developed a feeling of responsibility for the welfare of the patients. They put in efforts to present care and maintain daily life.

One caregiver stated: “Despite the challenge the ability to do what is requisite bestowed a feeling of obliged duty that was challenging to be expressed” (Coolbrandt 2015).

Simultaneously, the role of caregivers increased during this caring process. They faced a shift in awareness through experiencing personal growth to develop belief in a higher power as the controller. As a result, they tried to self-care while performing their duties, such as improving their own health to meet caregiving demands.

“Visits to friends or a concert kept the process of life ongoing given the vital impact of these activities” (Whisenant 2011).

Category 4: hope: positive life value

Learning coping strategies and management of role enable caregivers to maintain hope over time. Additionally, availability of information, solid and continuous support, particularly in the early period, were critical factors for them to regain strength for future.

“The availability of a supportive social environment by luck facilitated the handling of the burden” (Heckel 2008).

The focus of hope changed with the passage of time, helping patients and caregivers to move on. They were hopeful of betterment in the situation than what was indicated by the survival statistics. They hoped for treatment response, or new treatment options. Above all, they hoped for a quality life with patients. Their existential views made life less burdensome.

“A positive development instills the possibility of miracles as hope cannot be quelled” (Coolbrandt 2015).

Moreover, caregivers’ hope varied across the severity of glioma. Families with low-grade glioma were more likely to focus on their daily lives and return to a normal life; they were more likely to embrace hope and have new insights for the prognosis of the disease. In contrast, families with high-grade glioma tended to have immediate concerns about end-of-life and worry about the prolonged uncertainty.

“So I just hope that it doesn’t start growing again (28-year-old male with a low-grade glioma patient)” (Cavers 2013).

Synthesized finding 2: support and information need by caregivers of glioma patients

Category 1: role support is insufficient for caregivers

Caregivers of patients with glioma perceived a slew of support requirements that were unmet, encompassing a paucity of emotional and social support around chaotic situations beginning from the diagnosis of glioma. In addition, practical support, such as financial issues and access to rehabilitation institutions, was inadequate for them.

Professional support

As the disease progressed, caregivers often dealt with numerous unanswered questions and concerns, developing a feeling of “being left in the dark.” They often felt powerless in the process of contacting medical staff, particularly for issues like adverse effects of treatment, postsurgery treatment, and access to rehabilitation services. Many caregivers expressed the need for continuous support such as palliative care. They wanted to feel prepared to face and deal with any kind of situation. However, given the shortage of time and resources, professionals were constantly pressed for time, and questions were often left ignored or unanswered.

“There is a lack of continuity with no single doctor. Despite the efforts to memorize the name of the caregiver, a new doctor was there the next time the doctor’s name from the last visit. And then when we get there and it’s not him” (Collins 2014).

Support from friends and relatives

Most caregivers said they did receive support from family members, friends, and neighbors to cope with the problems during the difficult period. In the initial period of the malady, especially, when distress and uncertainty were at its peak, support from friends and relatives enabled people to maintain hope and helped them adjust to their illness. The sharing of responsibility or just being a good listener for caregivers evoked great gratitude, which enhanced their relationship physically and emotionally.

“My caregivers is my children and they instill determination and zeal for me” (Cavers 2013).

However, there were situations when caregivers tried to share negative attitudes and emotions they encountered in providing care, but had no one to vent to. They were afraid of sharing their bitter experiences even to friends or relatives in fear of being misinterpreted as being resentful or treacherous. As the behavioral or personality changes are unique in glioma patients, caregivers have to notice others’ perceptions and their effect of their subsequent reactions on the social life of family members.

“Some visiting friends displayed fear and hesitancy to closely connect attributed to fear or self-preservation […]” (Heckel 2008).

Social support

Social support either in the form of support group or online support networks was important to the caregivers, which enabled them to communicate with others who understood their situations. It is a safe place for caregivers to express their feelings and maintain their morale. Additionally, support groups emerge as a constructive source of information for caregivers to troubleshoot difficult situations. This kind of support was described as “a license to moan,” “additional comfort zones,” and a way of “getting things off their chest” by the caregivers.

One caregiver described the following: “The expression of anger is on the same lines among all that obliterated the feeling of guilt or feeling disloyal or anything” (Arber 2013).

Conversely, there were caregivers who found little time for the support group due to the requisite efforts for postsurgery treatment. Moreover, they had a feeling that attendance at a support group would focus on death and dying. Caregivers were also interested in practical, economic, and social support. In many cases, caregivers expressed a lack of requisite government support, because the physical condition of the patient was not “bad enough”, or they failed to get the information needed to the social welfare in time.

“The ability of the patient to perform activities without a nurse became an issue as he did not classify for nursing insurance level 1” (Wasner 2013).

Category 2: the varying information needs of caregivers

Among all the supports provided for caregivers, inadequate provision of information and its influence in the caring role was frequently emphasized, which could cause uncertainty and negative emotion. Caregivers wished comprehensive explanations about symptoms and changes that might arise in the prospective care trajectory. Information pertaining to medication, disease trajectory and treatment options, medical aid, and access to professional service were the most discussed, including the format and display of information. Lucidly written information and material with a clear structure were preferred by the caregivers in accomplishing their role properly and maintaining their well-being.

“A surgery was conducted without any elucidation and upon obtaining a sign on a paper. Further, there was lack of support as to whom was to be approached” (Tastan 2011).

Remarkably, caregivers were torn between a desire for obtaining detailed information and being unsure if they were well-prepared to take in any negative information. In some cases, caregivers had their individual methods to choose information, which revealed 2 different strategies to seek or limit the content and amount of information to retain hope.

One caregiver expressed the following: “A little reassurance could really augment spirits with too much peril being predicted” (Cavers 2013).

However, they found it difficult to ask questions and get the desired information. They rarely had the opportunity to meet professionals or had enough time to talk with the experts. Furthermore, they were hesitant to seek opinions from physicians they thought were inexperienced and preferred to wait for the so-called absolute expert.

One caregiver described the experience of getting information about the patient’s memory problems: “The loss of memory was confirmed by the physician in training, however, corroboration by the chief would further allay the stress of waiting” (Coolbrandt 2015).

Discussion

This systematic review aimed to evaluate qualitative research that explored the experiences of caregivers for glioma patients throughout the disease trajectory. Based on the 16 reviewed studies, 2 synthesized findings were identified.

The behavior change of caregivers for patients with glioma can be understood by the Transtheoretical Model (TTM) (Appendix 5) (36). Developed by Prochaska and DiClemente in the late 1970s, TTM focuses on the decision-making of individuals, highlighting the importance of intentional change. It is widely used for situations like smoking cessation and controlling weight (37,38). There are 5 stages in the change process: precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance. Behavior change is a dynamic process that progresses gradually and is strengthened continuously (36). Each stage is determined by a person’s degree of motivation. Initially, caregivers experienced chaos as they were unprepared for the sudden change. After a period of adapting, the commitment and responsibility prompted them to move on; the self-efficacy of being caregivers motivated them during the whole process. Thereafter, a number of caregivers developed a positive outlook about life, which helped them to encounter and deal with the situation throughout the illness trajectory.

The support and information need of caregivers for glioma patients were another important theme gleamed from the review. The support and information need of caregivers are unique and changing dynamically with the disease progress. The majority of included studies highlighted the importance of providing support to caregivers for glioma patients. This can be similar to the family caregivers for other diseases like dementia (39) and cancer (40,41). However, every disease has a unique illness trajectory; hence, the need for a different support was identified. Due to the high morbidity and mortality, and accompanying by neurocognitive and behavioral changes in glioma patients (42), the experience and need perceived by caregivers are different from those of other diseases.

As the disease progressed, caregivers experienced changes over time, indicating the need for permanent professional support throughout the illness trajectory. Once the patients were diagnosed with glioma, patients and caregivers needed information support to help them in decision-making. Information pertaining to medication, treatment, and rehabilitation are frequently mentioned in the literature (43-45).

Additionally, patients and family caregivers must face surgical intervention, which may result in neurological deterioration or even death during surgery. The underlying uncertainty increases the responsibility placed on the patients’ caregivers; they feel sad and apprehensive. In this stage, providing the patients and caregivers with preoperative information may cause these feelings to subside. Furthermore, the radiotherapy and chemotherapy performed after the patients’ surgery can cause various side-effects, such as fatigue and cognitive function disorders (46). The caregivers need information on how to deal with these side effects as performing daily activities becomes increasingly difficult, thus escalating the need for care and support. In view of the above phenomena in the disease trajectory, healthcare providers should try to impart information based on the disease stage and patient/family requirements.

Once patients are diagnosed with glioma, it is evident that family caregivers become the cornerstone of support. Given their best knowledge about a patient, in the event of impaired cognitive ability, this can be vital. Thus, the caregivers should be able to help and support the patients as much as possible. As confirmed in the literature (47,48), the caregiver burden becomes a challenge for a caregiver’s commitment, which is on the same lines as Alzheimer’s disease patients’ caring experiences (49). However, a variety of research have indicated that supportive care needs for the caregivers are not being met (50-52). Generally, there are 3 main resources of support: family, social, and professional. These supports act to cushion the impact of the disease. Although caregivers rely on family members and friends in the caring process, they may choose not to confide in them thinking that no one could help them, and thus they are alone in the situation. This can lead to a feeling of distress. As time goes on, a lack of balance between responsibilities of care and a normal social life become obvious, which calls for complementary support from other resources.

Furthermore, a few studies have investigated the effects of a multiprofessional team. Physicians, nurses, social workers, case managers, psychologists, and chaplains can come together to build a supportive group that includes acknowledging distress, listening to concerns, and providing reassurance and information. The implementation of such supportive programs was reported in other illnesses, such as stroke (53), dementia (54), and cancer (55). Throughout the whole process, nurses who have the most contact with patients ideally should initiate steps to make a difference.

Future research should be conducted to fulfil the support and information need for caregiver of glioma patients. Firstly, training opportunities should be provided for informal caregivers, especially those novel caregivers, to help them provide effective care. Furthermore, standardized health care manuals should also be published and provided to family caregivers as a reliable reference. Then, the extended care service like the community health care institutions and telehealth should also play their roles in supporting caregivers. In addition, the government should formulate certain health-related policy to help informal caregivers receive economical and social support to resolve their practical problems.

Above all, this paper draws a whole picture of caregivers experience during the whole disease trajectory by synthesizing 16 qualitative research. It identified the use of TTM (Transtheoretical Model) for glioma caregivers to explain their behavior change during the disease trajectory, which added the scope of the TTM. In addition, it is important to note that the support and information need of caregivers for glioma patients are changing with the disease progress, which suggests that the health care processionals should adjust their strategies dynamically and provide individualized support for caregivers.

Conclusions

The caregivers for glioma patients experience a role transition during the disease trajectory. However, role support and information provided are insufficient for caregivers of glioma patients. Therefore, recognizing the importance of permanent and customized support to caregivers by providing honest and evidence-based information is crucial.

Strengths and limitations

This systematic review is the first to provide a comprehensive understanding of the experiences of caregivers for patients with glioma. It includes caregivers from different cultural backgrounds with different disease stages; hence, the shift in relationship, specific needs, and supportive care appear to be systematic and widespread.

A limitation of this review is the omission of the researcher’s impact on the study and vice-versa in most selected studies. This refers to the personal bias challenge that impacts the quality of qualitative research. This presents an undercurrent existence of some personal impact during the meta-synthesis. In addition, given the exclusion of articles that were not in English or Chinese language, the applicability of the research findings in all sociocultural scenarios is challenging.

Supplementary

The article’s supplementary files as

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by the 15th batch of “Six Talent Peaks” High-level Talent Selection and Training Funding Program in Jiangsu Province (No. WSW-127), the Third Phase Open Project of Nursing Advantage Discipline of Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine (No. 2019YSHL146), and the Research and Practice Innovation Program for Postgraduate Students for Medical School of Nanjing University in 2021.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the PRISMA reporting checklist. Available at https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/atm-21-2761

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/atm-21-2761). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

(English Language Editor: J. Gray)

References

- 1.Walsh KM, Ohgaki H, Wrensch MR. Epidemiology. Handb Clin Neurol 2016;134:3-18. 10.1016/B978-0-12-802997-8.00001-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, et al. The 2016 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: a summary. Acta Neuropathol 2016;131:803-20. 10.1007/s00401-016-1545-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li K, Lu D, Guo Y, et al. Trends and patterns of incidence of diffuse glioma in adults in the United States, 1973-2014. Cancer Med 2018;7:5281-90. 10.1002/cam4.1757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neuroimmunology Group of Neurology Branch of Chinese Medical Association. Neuroimmunology Committee of Chinese Society for Immunology, Immunology Society of Chinese Stroke Association . Chinese Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Tumefactive Demyelinating Lesions of Central Nervous System. Chin Med J (Engl) 2017;130:1838-50. 10.4103/0366-6999.211547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McNeill KA. Epidemiology of Brain Tumors. Neurol Clin 2016;34:981-98. 10.1016/j.ncl.2016.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ostrom QT, Cioffi G, Gittleman H, et al. CBTRUS Statistical Report: Primary Brain and Other Central Nervous System Tumors Diagnosed in the United States in 2012-2016. Neuro Oncol 2019;21:v1-v100. 10.1093/neuonc/noz150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang L, Su J, Jia X, et al. Treating malignant glioma in Chinese patients: update on temozolomide. Onco Targets Ther 2014;7:235-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saito J, Masters J, Hirota K, et al. Anesthesia and brain tumor surgery: technical considerations based on current research evidence. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2019;32:553-62. 10.1097/ACO.0000000000000749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.GBD 2016 Brain and Other CNS Cancer Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of brain and other CNS cancer, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol 2019;18:376-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ownsworth T, Hawkes A, Steginga S, et al. A biopsychosocial perspective on adjustment and quality of life following brain tumor: a systematic evaluation of the literature. Disabil Rehabil 2009;31:1038-55. 10.1080/09638280802509538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baumstarck K, Leroy T, Hamidou Z, et al. Coping with a newly diagnosed high-grade glioma: patient-caregiver dyad effects on quality of life. J Neurooncol 2016;129:155-64. 10.1007/s11060-016-2161-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zwinkels H, Dirven L, Vissers T, et al. Prevalence of changes in personality and behavior in adult glioma patients: a systematic review. Neurooncol Pract 2016;3:222-31. 10.1093/nop/npv040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Halkett GK, Lobb EA, Shaw T, et al. Do carer's levels of unmet needs change over time when caring for patients diagnosed with high-grade glioma and how are these needs correlated with distress? Support Care Cancer 2018;26:275-86. 10.1007/s00520-017-3846-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Given BA, Given CW, Sherwood P. The challenge of quality cancer care for family caregivers. Semin Oncol Nurs 2012;28:205-12. 10.1016/j.soncn.2012.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Drageset S, Lindstrøm TC, Underlid K, et al. Coping with breast cancer: between diagnosis and surgery. J Adv Nurs 2010;66:149-58. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.05210.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adashek JJ, Subbiah IM. Caring for the caregiver: a systematic review characterising the experience of caregivers of older adults with advanced cancers. ESMO Open 2020;5:e000862. 10.1136/esmoopen-2020-000862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whisenant M. Informal caregiving in patients with brain tumors. Oncol Nurs Forum 2011;38:E373-E381. 10.1188/11.ONF.E373-E381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pearson A. Balancing the evidence: incorporating the synthesis of qualitative data into systematic reviews. JBI Reports 2004;2:45-64. 10.1111/j.1479-6988.2004.00008.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.IJzerman-Korevaar M, Snijders TJ, de Graeff A, et al. Prevalence of symptoms in glioma patients throughout the disease trajectory: a systematic review. J Neurooncol 2018;140:485-96. 10.1007/s11060-018-03015-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aromataris E, Munn Z. editors. JBI Reviewer’s Manual [internet]. Adelaide: JBI; 2017 [cited 2017 Oct 2]. Available online: https://reviewersmanual.joannabriggs.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arber A, Hutson N, de Vries K, et al. Finding the right kind of support: a study of carers of those with a primary malignant brain tumour. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2013;17:52-8. 10.1016/j.ejon.2012.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cavers D, Hacking B, Erridge SC, et al. Adjustment and support needs of glioma patients and their relatives: serial interviews. Psychooncology 2013;22:1299-305. 10.1002/pon.3136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Collins A, Lethborg C, Brand C, et al. The challenges and suffering of caring for people with primary malignant glioma: qualitative perspectives on improving current supportive and palliative care practices. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2014;4:68-76. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2012-000419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coolbrandt A, Sterckx W, Clement P, et al. Family Caregivers of Patients with a High-Grade Glioma A Qualitative Study of Their Lived Experience and Needs Related to Professional Care. Cancer Nurs 2015;38:406-13. 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Edvardsson T, Ahlström G. Being the next of kin of a person with a low-grade glioma. Psychooncology 2008;17:584-91. 10.1002/pon.1276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heckel M, Hoser B, Stiel S. Caring for patients with brain tumors compared to patients with non-brain tumors: Experiences and needs of informal caregivers in home care settings. J Psychosoc OncoL 2018;36:189-202. 10.1080/07347332.2017.1379046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McConigley R, Halkett G, Lobb E, et al. Caring for someone with high-grade glioma: a time of rapid change for caregivers. Palliat Med 2010;24:473-9. 10.1177/0269216309360118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ownsworth T, Goadby E, Chambers SK. Support after brain tumor means different things: family caregivers' experiences of support and relationship changes. Front Oncol 2015;5:33. 10.3389/fonc.2015.00033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Piil K, Jakobsen J, Christensen KB, et al. Needs and preferences among patients with high-grade glioma and their caregivers - A longitudinal mixed methods study. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2018;27:e12806. 10.1111/ecc.12806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sacher M, Meixensberger J, Krupp W. Interaction of quality of life, mood and depression of patients and their informal caregivers after surgical treatment of high-grade glioma: a prospective study. J Neurooncol 2018;140:367-75. 10.1007/s11060-018-2962-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Salander P. Brain tumor as a threat to life and personality: The spouse's perspective. J Psychosoc Oncol 1996;14:1-18. 10.1300/J077v14n03_01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schmer C, Ward-Smith P, Latham S, et al. When a family member has a malignant brain tumor: the caregiver perspective. J Neurosci Nurs 2008;40:78-84. 10.1097/01376517-200804000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tastan S, Kose G, Iyigun E, et al. Experiences of the relatives of patients undergoing cranial surgery for a brain tumor: A descriptive qualitative study. J Neurosci Nurs 2011;43:77-84. 10.1097/JNN.0b013e31820c94da [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wasner M, Paal P, Borasio GD. Psychosocial care for the caregivers of primary malignant brain tumor patients. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care 2013;9:74-95. 10.1080/15524256.2012.758605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wideheim AK, Edvardsson T, Pahlson A, et al. A family's perspective on living with a highly malignant brain tumor. Cancer Nurs 2002;25:236-44. 10.1097/00002820-200206000-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Prochaska JO, Velicer WF. The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. Am J Health Promot 1997;12:38-48. 10.4278/0890-1171-12.1.38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu YK, Chu NF. Introduction of the transtheoretical model and organisational development theory in weight management: A narrative review. Obes Res Clin Pract 2015;9:203-13. 10.1016/j.orcp.2014.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Inoue S, Shimomitsu T. The behavioral approach to promote physical activity--application of the transtheoretical model. Nihon Rinsho 2000;58 Suppl:538-44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sacks D, Baxter B, Campbell B, et al. Multisociety Consensus Quality Improvement Revised Consensus Statement for Endovascular Therapy of Acute Ischemic Stroke. Int J Stroke 2018;13:612-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Koch-Gallenkamp L, Bertram H, Eberle A, et al. Fear of recurrence in long-term cancer survivors-Do cancer type, sex, time since diagnosis, and social support matter? Health Psychol 2016;35:1329-33. 10.1037/hea0000374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hatamipour K, Rassouli M, Yaghmaie F, et al. Spiritual needs of cancer patients: a qualitative study. Indian J Palliat Care 2015;21:61-7. 10.4103/0973-1075.150190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bunevicius A. Personality traits, patient-centered health status and prognosis of brain tumor patients. J Neurooncol 2018;137:593-600. 10.1007/s11060-018-2751-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Halkett GK, Lobb EA, Oldham L, et al. The information and support needs of patients diagnosed with High Grade Glioma. Patient Educ Couns 2010;79:112-9. 10.1016/j.pec.2009.08.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Boele FW, Hoeben W, Hilverda K, et al. Enhancing quality of life and mastery of informal caregivers of high-grade glioma patients: a randomized controlled trial. J Neurooncol 2013;111:303-11. 10.1007/s11060-012-1012-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lobb EA, Halkett GK, Nowak AK. Patient and caregiver perceptions of communication of prognosis in high grade glioma. J Neurooncol 2011;104:315-22. 10.1007/s11060-010-0495-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rasmussen BK, Hansen S, Laursen RJ, et al. Epidemiology of glioma: clinical characteristics, symptoms, and predictors of glioma patients grade I-IV in the Danish Neuro-Oncology Registry. J Neurooncol 2017;135:571-9. 10.1007/s11060-017-2607-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Boele FW, van Uden-Kraan CF, Hilverda K, et al. Attitudes and preferences toward monitoring symptoms, distress, and quality of life in glioma patients and their informal caregivers. Support Care Cancer 2016;24:3011-22. 10.1007/s00520-016-3112-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jacobs DI, Kumthekar P, Stell BV, et al. Concordance of patient and caregiver reports in evaluating quality of life in patients with malignant gliomas and an assessment of caregiver burden. Neurooncol Pract 2014;1:47-54. 10.1093/nop/npu004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Raggi A, Tasca D, Panerai S, et al. The burden of distress and related coping processes in family caregivers of patients with Alzheimer's disease living in the community. J Neurol Sci 2015;358:77-81. 10.1016/j.jns.2015.08.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sklenarova H, Krümpelmann A, Haun MW, et al. When do we need to care about the caregiver? Supportive care needs, anxiety, and depression among informal caregivers of patients with cancer and cancer survivors. Cancer 2015;121:1513-9. 10.1002/cncr.29223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Applebaum A. Isolated, invisible, and in-need: there should be no "I" in caregiver. Palliat Support Care 2015;13:415-6. 10.1017/S1478951515000413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rigby H, Gubitz G, Phillips S. A systematic review of caregiver burden following stroke. Int J Stroke 2009;4:285-92. 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2009.00289.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cameron JI, Naglie G, Silver FL, et al. Stroke family caregivers' support needs change across the care continuum: a qualitative study using the timing it right framework. Disabil Rehabil 2013;35:315-24. 10.3109/09638288.2012.691937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Huis In Het Veld JG, Verkaik R, Mistiaen P, et al. The effectiveness of interventions in supporting self-management of informal caregivers of people with dementia; a systematic meta review. BMC Geriatr 2015;15:147. 10.1186/s12877-015-0145-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Northouse LL, Katapodi MC, Song L, et al. Interventions with family caregivers of cancer patients: meta-analysis of randomized trials. CA Cancer J Clin 2010;60:317-39. 10.3322/caac.20081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The article’s supplementary files as