Abstract

Tuberculosis (TB) affecting the liver is unusual, and isolated liver TB presenting as a liver abscess more so, even in countries where the disease is endemic. As clinical symptoms and imaging are not typical, a high index of suspicion is necessary for diagnosis. We present here a lady who was admitted with fever and chills. Ultrasound imaging showed a liver abscess. She developed bleeding into the abscess cavity, necessitating an emergency right liver resection. Final histology confirmed mycobacterial granulomatous infection of the liver. Isolated hepatic abscess of tubercular origin is a rare cause of hemorrhage but should be considered as a differential diagnosis. Suspicious features on computerized tomography (CT) scan should prompt microbiological assessment of aspirate from the abscess, establishing the diagnosis, so appropriate treatment can be started, avoiding such complications.

Keywords: liver, tuberculosis, abscess, hemorrhage, hepatectomy

Abbreviations: CT Scan, Computed Tomography; DSA, Digital Subtraction Angiography; ELISA, Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay; PCR, Polymerase Chain Reaction; TB, Tuberculosis

Introduction

Tuberculous liver abscess is very rarely seen in the liver, with a prevalence of only 0.34% in patients with hepatic tuberculosis (TB).1 Although the liver may be involved in miliary TB, isolated involvement of the liver is unusual. Owing to nonspecific signs, symptoms and imaging features, diagnosis of tuberculous liver abscess is rarely made before aspiration or histopathology.2 We present a rare case of tuberculous liver abscess with hemorrhage, requiring urgent surgery.

Case report

A 63-year-old female presented with a 10-day history of upper abdominal pain and high fever with chills. Ultrasound scan showed a 6cm right lobe liver abscess and some bowel wall thickening in the right colon. A clinical diagnosis of amoebic liver abscess was carried out, and she was treated with intravenous metronidazole. However, she was transferred to our tertiary care facility with a worsening clinical condition, with tachycardia and hypotension. She was resuscitated appropriately in the intensive care unit. Hemogram showed a sharp drop in hemoglobin to 5.0 gm% and urgent computerized tomography (CT) scan abdomen was carried out. There was no evidence of any gastrointestinal bleeding and coagulation was normal. The clinical picture was consistent with hemorrhagic shock. The CT scan confirmed a 6.7 cm subcapsular and intraparenchymal mixed density fluid collection with solid components, epicentred in segments 6 and 7 of the liver. Hyperdensity of the collection and contrast extravasation confirmed an active bleed in the previously diagnosed liver abscess (Figure 1). In addition, there was nonvisualization of the right posterior sectoral portal vein and attenuation of the right anterior sectoral portal vein and right hepatic vein (Figure 1). Mild inflammatory thickening of the cecum was noted. An urgent formal angiography (digital subtraction angiography) was carried out in view of the CT angiography findings (Figure 2). As was seen on the CT angiography, there was nonvisualization of the posterior portal pedicle on the portal phase of the angiogram (Figure 2A), and no evidence of any arterial blush/extravasation was noted on the arterial phase of the angiogram (Figure 2B). Hence no therapeutic intervention at angiography was indicated. In view of persistent hemorrhagic shock, she underwent exploration. At laparotomy, a large hematoma within a necrotic friable abscess cavity was seen involving segments 5, 6, and 7 of the liver (Figure 3).There was a diffuse ooze from the abscess cavity and subcapsular surface and associated hemoperitoneum (1.2 L). A right hepatectomy was performed as a definitive procedure to control the bleeding source and excise all necrotic debris (Figure 4). Postoperative recovery was uneventful, apart from a right sided pleural effusion which required Ultrasound guided aspiration (Clavien - Dindo, 3 A).Finalhistology confirmed necrotizing granulomatous inflammation of the liver with superadded pyogenic inflammation. This was associated with endarteritis and periarteritis involving the small vessels. Typical findings of mycobacterial infection consisting of necrosis, granulomas and giant cells were seen (Figure 5).The findings were consistent with TB of the liver. The background liver parenchyma did not show any abnormality. The patient was discharged on postoperative day 11 without any further complications. She was commenced on antitubercular therapy. This included our patient had isolated hepatic TB. This was seen on preoperative imaging (CT scan) including dedicated imaging of the chest and the abdomen. There was no other abnormality within the abdomen, detected during the laparotomy either. The patient was seen at 1 month and 3 months aftersurgery and at completion of the antitubercular therapy. Follow-up at 1 month included a CT scan, which confirmed standard postoperative changes with no fresh abnormality. An ultrasound of the abdomen and chest x ray performed during the duration of the antitubercular therapy did not show any new foci of TB Antitubercular therapy (AKT) was commenced 2 weeks after surgery. AKT consisted of a combination of Rifampicin (10 mg/kg/day) 600 mg once a day, isoniazid (5 mg/kg/day) 300 mg once a day,e thambutol (20 mg/kg/day) 1200 mg once a day and pyrazinamide(25 mg/kg/day) 1500 mg once a day. Pyrazinamide was discontinued after 2 months, and the rest of the medications were continued until completion of therapy at 9 months.

Figure 1.

CT scan showing the liver abscess and lesion. CT, computerized tomography.

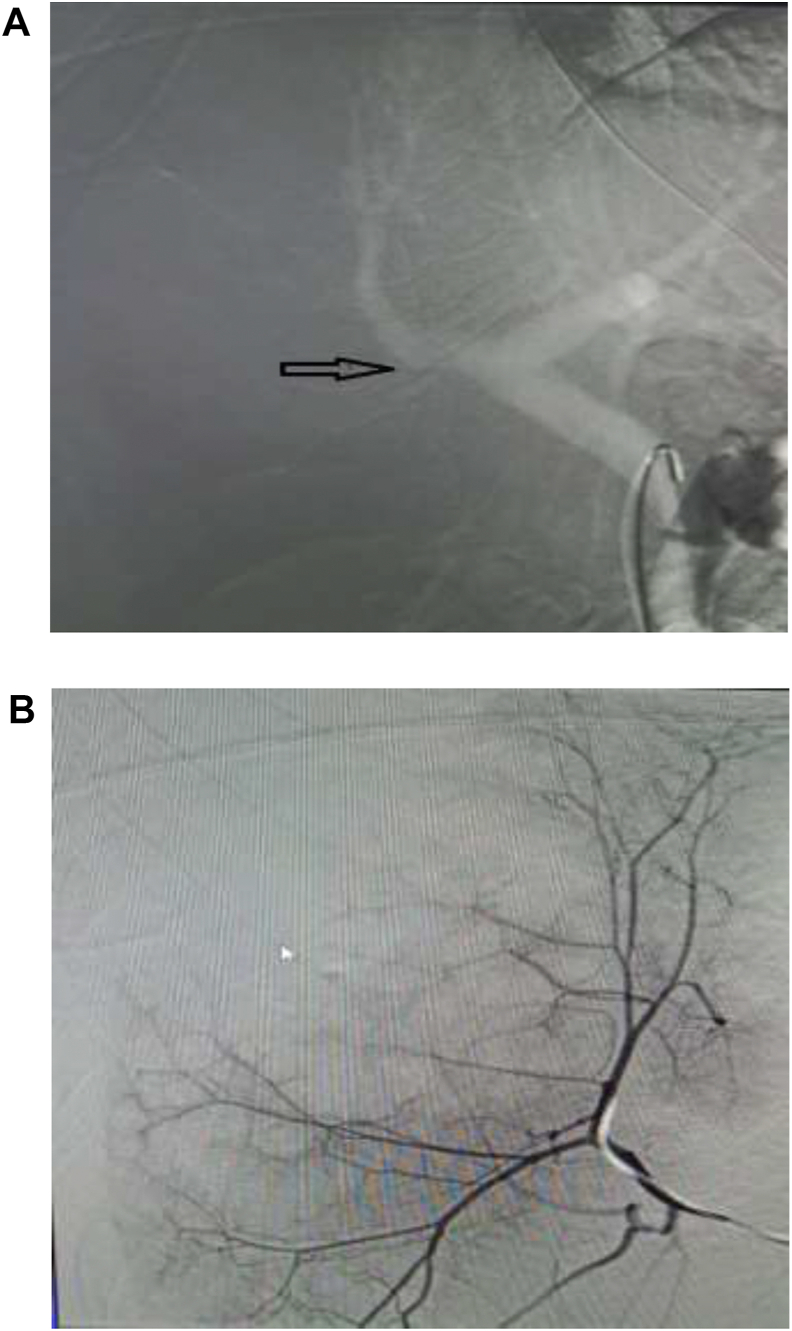

Figure 2.

Angiogram images A: Portal phase of the angiogram showing nonvisualization of the posterior portal pedicle. B: Arterial phase showing no obvious extravasation or blushing.

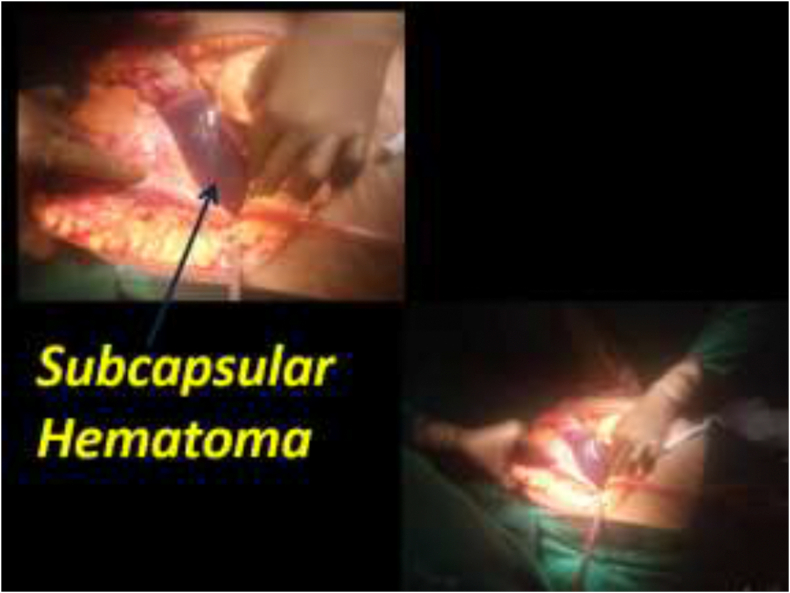

Figure 3.

Intraoperative images of the liver abscess and lesion.

Figure 4.

Right hepatectomy.

Figure 5.

Histology microphotograph (H & E) confirming mycobacterial infection.

Discussion

TB continues to be a major health problem worldwide, despite significant advances in the diagnosis and treatment of the condition. Isolated extra pulmonary TB occurs in 15% of all cases of TB.3 The abdomen is the 6th most common site of extrapulmonary mycobacterial infection.4 Although miliary TB involves the liver commonly and liver is affected in 10–15% of patients with pulmonary TB, isolated hepatic TB is a rare diagnosis, accounting for <1% of all TB infections.5 This is thought to be due to the low tissue oxygen level which makes the liver inhospitable for the bacilli.6 Liver abscess is also a common diagnosis in tropical countries such as India and most commonly happens secondary to amoebic or pyogenic infections.7 Liver abscess from tubercular origin further complicates the rare diagnosis of hepatic TB and has mostly been associated with disseminated miliary TB in immunocompromised patients.7 Low grade fever, along with anorexia, weight loss, and nonspecific constitutional symptoms remain the commonest presentation of TB. Hepatic TB may be completely asymptomatic or may present with constitutional symptoms. Similar to most lesions within the liver, imaging would form the cornerstone for diagnosis of the liver abscess and its further characterization. Ultrasound is a good initial investigation and may help in aspiration, but in our opinion a triphasic CT scan of the liver with hepatic arterial, portal venous and delayed phases is mandatory for the diagnosis of any space occupying lesion within the liver. It also reliably rules out primary or secondary hepatic malignancies. TB of the liver may present in a diffuse form with multiple hypodense lesions, scattered across the liver or focal nodular lesions with ring-like peripheral enhancement or hypodense lesions around the biliary radicals appearing similar to cholangitic abscesses.8 It may also present as a solitary hypodense lesion mimicking a hepatoma.9 Our patient also had similar findings of a large lesion with mixed echoes within, secondary to internal hemorrhage. The active hemorrhage within the lesion did not arouse the suspicion of it being a granulomatous lesion. In addition, with intraperitoneal rupture, there was hemoperitoneum and an acute deterioration in the hemodynamic condition. Even when the lesions have been aspirated, mycobacteria have not been isolated, and confirmation of diagnosis has only been made at laparotomy.10 The aspirates only contain necrotic material in such instances and hence are noncontributory.11 A few cases of ruptured tuberculous liver abscess have been reported.12, 13, 14 Jain et al2 reported a case of retroperitoneal rupture of TB liver abscess. The commonest differentials for such a lesion seen on CT scan and clinically would include a ruptured amoebic liver abscess or a pyogenic liver abscess secondary to colonic diverticulitis or appendicitis. These remain the commonest conditions especially in India and tropical countries where these infections are endemic. Other differentials include a ruptured liver tumor – hepatocellular carcinoma or a nonencapsulated cholangiocarcinoma. Echinococcal infection of the liver (hydatid cyst) can also present rarely in this manner. On rare occasions, necrotic tumor metastases may present with rupture and hemorrhage but this is even rarer. To our knowledge, this is possibly the first reported case of spontaneous hemorrhage within a tuberculous liver abscess, compelling a hepatectomy. Hepatic surgery for tubercular liver abscess has been described, where aspiration has been unsuccessful owing to the debris being too thick or multiseptate.15 Upon diagnosis of any form of abdominal TB, we recommend performing a dedicated and complete CT scan of the chest and the abdomen including the pelvis to rule out any other sites of TB. In our opinion, these investigations are optimum and necessary to rule out any synchronous sites of TB. More specialized tests may be carried out to cater to a specific clinical scenario, if required. Use of Enzyme Linked Immuno Sorbent Assay (ELISA) polymerase chain reaction has been found to be useful in the detection of hepatic TB and can be performed on pus aspirates.15 Suspicion of mycobacterial etiology should therefore be borne in mind when investigating liver abscesses. All attempts must therefore be made to secure a diagnosis and commence antitubercular therapy, which can avoid surgery or complications of rupture and bleeding.7

Conclusion

Isolated tuberculous abscess of the liver in an immunocompetent individual is a rare diagnosis requiring a high index of suspicion to reach early diagnosis. This will prompt early treatment and prevent unnecessary surgery and life-threatening complications.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Shitesh Malewadkar: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Writing - original draft. Vivek Shetty: Formal analysis, Writing - original draft, Data curation, Resources. Soumil Vyas: Formal analysis, Project administration, Validation, Writing - review & editing. Nilesh Doctor: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft, Project administration, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing - review & editing.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have none to declare.

Funding

None.

References

- 1.Essop A.R., Segal I., Posen J., Noormohamed N. Tuberculous abscess of the liver. A case report. S Afr Med J. 1983 May 21;63:825–826. PubMed PMID: 6845110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jain R., Sawhney S., Gupta R.G., Acharya S.K. Sonographic appearances and percutaneous management of primary tuberculous liver abscess. J Clin Ultrasound. 1999 Mar-Apr;27:159–163. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0096(199903/04)27:3<159::aid-jcu11>3.0.co;2-k. PubMed PMID: 10064416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ho P.L., Chim C.S., Yuen K.Y. Isolated splenic tuberculosis presenting with pyrexia of unknown origin. Scand J Infect Dis. 2000;32:700–701. doi: 10.1080/003655400459685. PubMed PMID: 11200387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chaudery M., Mohamed F., Shirol S., Gudgeon M. An unusual presentation of Intra-abdominal tuberculosis in a young man. J R Soc Med. 2010 May;103:199–201. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.2010.090350. Erratum in: J R Soc Med. 2010 Jul; 103(7):265. Gudgeon, Mark [added]. PubMed PMID: 20436028; PubMed Central. PMCID: PMC2862073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haque M.M.U., Whadva R.K., Luck N.H., Mubarak M. Primary hepaticobiliary tuberculosis mimicking gall bladder carcinoma with liver invasion: a case report. Pan Afr Med J. 2019 Feb 7;32:68. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2019.32.68.10519.eCollection2019. PubMed PMID: 31223360; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6560998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hussain W., Mutimer D., Harrison R., Hubscher S., Neuberger J. Fulminant hepatic failure caused by tuberculosis. Gut. 1995 May;36:792–794. doi: 10.1136/gut.36.5.792. PubMed PMID: 7797133; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC1382689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Devi S., Mishra P., Sethy M., Thakur G.S. Isolated tubercular liver abscess in a non-immunodeficient patient: a rare case report. Cureus. 2019 Dec 3;11 doi: 10.7759/cureus.6282. PubMed PMID: 31911874; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6939970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maartens G., Wilkinson R.J. vol. 370. 2007 Dec 15. pp. 2030–2043. (Tuberculosis. Lancet). Review. PubMed PMID: 17719083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zorbas K., Koutoulidis V., Foukas P., Arkadopoulos N. Hepatic tuberculoma mimicking hepatocellular carcinoma in an immunocompetent host. BMJ Case Rep. 2013 Dec 4;2013 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-008775. pii: bcr2013008775 PubMed PMID: 24306427; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3863101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rahmatulla R.H., al-Mofleh I.A., al-Rashed R.S., al-Hedaithy M.A., Mayet I.Y. Tuberculous liver abscess: a case report and review of literature. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001 Apr;13:437–440. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200104000-00024. Review. PubMed PMID: 11338077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Biswas B.K., Pal S., Moulik D.J., Sikdar M. Isolated hepatic tuberculoma - a case report. Iran J Pathol. 2016 Fall;11:427–430. Epub 2016 Dec 24. PubMed PMID: 28974959; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5604103. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jain V.K., Mathur K.C., Chadda V.S., Lodha S.K. Tuberculous liver abscess. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. 1981 Apr-Jun;23:97–99. PubMed PMID: 7298083. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pandya J.S., Kandekar R.V., Tiwari A.R., Kadam R., Adhikari D.R. Primary liver abscess with anterior abdominal wall extension caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016 Nov;10:PD08–PD09. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2016/21845.8795. Epub 2016 Nov 1. PubMed PMID: 28050433; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5198386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bansal M., Dalal P., Kadian Y., Malik N. Tubercular liver abscess rupturing into the pleural cavity: a rare complication. Trop Doct. 2019 Oct;49:320–322. doi: 10.1177/0049475519864749. Epub 2019 Jul 23. PubMed PMID: 31335264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hassani K.I., Ousadden A., Ankouz A., Mazaz K., Taleb K.A. Isolated liver tuberculosis abscess in a patient without immunodeficiency: a case report. World J Hepatol. 2010 Sep 27;2:354–357. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v2.i9.354. PubMed PMID: 21161020; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2999300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]