Abstract

Muslim populations in Western countries are growing, and they face biopsychosocial, spiritual, and economic challenges. Although Islam gives utmost attention to mental health stability, Muslims tend to underutilize mental health services. Mental health professionals, whether they be researchers, practitioners, or trainers working in schools, colleges/universities, mental health agencies, and research institutions, are well positioned to serve Muslims. Mental health professionals can address Muslims’ biopsychosocial and spiritual issues and enhance their quality of life. In the current study, as the authors, we (a) reviewed 300 peer-reviewed manuscripts on Muslim mental health to understand how researchers have used concept maps or theoretical frameworks to design their empirical research, (b) prepared a comprehensive concept map based on the literature review to determine the central concepts affecting Muslims’ approach to the use of mental health services, and (c) proposed a contextual theoretical (conceptual) framework. We titled the framework as Muslims’ approach to use of mental health services based on the Theory of Planned Behavior and the Theory of Reasoned Action (TPB/TRA) in the context of a Social Ecological Model (SEM). We drew the framework based on TPB/TRA, SEM, and the review of Muslim mental health literature (the concept map). The concept map and the framework provide the most important constructs about challenges Muslim’s face when attempting to utilize mental health services. Future researchers can use the concept map and the framework to conduct theoretically and evidence-based grounded empirical research. We provided implications for researchers, practitioners, educators, and social advocates wishing to contribute to service provision to this population.

Keywords: Muslim mental health, Theory of planned behavior, Theory of reasoned action, Social ecological model, Psychology in Islam, Attitudes, Stigma

Introduction

Spirituality or religiosity has garnered greater attention in different areas including mental health research and services (Carey et al., 2021; Cashwell et al., 2013; Drummond & Carey, 2020; Tanhan, 2019, 2020; Tanhan et al., 2020a, 2020b; Yıldırım et al., 2021c; Young & Cashwell, 2016). Muslims have received increased, and often negative, attention over the past 20 years, particularly in Western countries including the USA. Resources indicate that Islam is the fastest growing religion in the USA (Pew Research Center, 2016). According to the Council on American–Islamic Relations (CAIR, 2015), there are approximately seven million Muslims living in the USA.

Researchers studying Muslim mental health have noted that members of this population face many psychosocial challenges across five domains: globally, within the larger community, in their local communities, interpersonally, and intrapersonally (Ahmed et al., 2014; Ansary & Salloum, 2012; Genc & Baptist, 2020; Nadal et al., 2012; Tanhan & Francisco, 2019; Toprak, 2018). Researchers (Chaudhry & Li, 2011; Tanhan & Francisco, 2019; Tanhan & Strack, 2020) reported that US Muslims are more likely to experience mental health issues than any other minority group due to the psychosocial challenges they encounter. Yet, these individuals are consistently underserved (Ahmed & Reddy, 2007; Bhattacharyya et al., 2014; Tanhan & Francisco, 2019).

Need for Contextually Sensitive Approaches in Muslim Mental Health

Muslims tend to forgo the use of formal mental health services for a variety of complex reasons (Padela et al., 2012; Tanhan & Francisco, 2019) including the lack of contextually effective services (Agilkaya-Şahin, 2019; Tanhan, 2019; Tanhan & Strack, 2020). Yet, developing effective approaches can be difficult and take time. For example, Badri (2018), reported that he was mocked and threatened with termination from his position when he began discussing the need for more contextually, spiritually, religiously, and culturally sensitive approaches for working with Muslims back in 1965. A critical point for Islam and psychology began with Malik Badri’s Dilemma of Muslim Psychologists where he criticized acontextual effort of mental health providers and researchers in Muslim majority countries to use Western approaches, which were ineffective in reaching the public (Badri, 1979, 2020). Skinner (2010) also stressed the need for more sensitive approaches to effectively serve Muslims.

Subsequently, understanding the factors that contribute to the Muslims’ underutilization of mental health services is important (Tanhan & Francisco, 2019; Tanhan & Strack, 2020; Tummala-Narra & Claudius, 2013). These researchers identified numerous influences (e.g., cultural beliefs, stigma, lack of knowledge about mental health services) that drive Muslims’ approach to using mental health service. Other researchers called for systematic investigation into the barriers to service consumption and articulated the need for clear concept maps and theoretical frameworks to guide both research and practice (Agilkaya-Şahin, 2019; Tanhan & Francisco, 2019; Tanhan & Strack, 2020). To date, however, there has been a noticeable lack of such concept maps within the literature. Additionally, a dearth of thorough literature reviews exists and there are limited theoretical frameworks available to understand this population which has hampered the progress of research. Considering recent COVID-19 pandemic, need for contextually sensitive and effective research and services are needed even more (Arslan & Yıldırım, 2021; Tanhan, 2020; Tanhan et al., 2020a, 2020b; Yıldırım et al., 2021a).

Purpose of This Study

Our purpose in this manuscript was (a) to propose a concept map that included key factors that explain how Muslims populations approach mental health services utilization and (b) to offer an empirically testable contextual theoretical framework that may help clarify Muslims decision making in relation to seeking out mental health services.

Traditional Conceptualization of Mental Health Issues

Researchers have reported a range of findings about Muslims’ knowledge of the biomedical explanations of mental health issues (Bagasra & Mackinem, 2014; Tanhan, 2017) and more traditional cultural explanations (Kpobi & Swartz, 2019). Tanhan and Francisco (2019) provided a detailed table for the primary and secondary sources of Islam, which are some of the most important factors to understand how Islam affects Muslims’ life and their approach to mental health services. Tanhan (2017, 2019) reported that Muslims hold both cultural and biomedical explanations of mental health issues.

Three Categories for Conceptualization of Mental Illness: Islam and Muslims’ Culture

Tanhan outlined three categories that originate from cultural or Islamic sources that often impact conceptualizations of mental illness (2017, 2019). The first category is (a) direct teachings from primary sources of Islam: Quran and Sunnah. This category has three subcategories. First (i) subcategory is seeing mental health issues as a test. The second (ii) subcategory is influence of supernatural entities (jinns, shaytan meaning evil, nazar or al-ayn meaning evil eye, and black magic). The third (iii) is lack of or weak faith or lack of practicing it might lead to mental health issues. This last subcategory stresses a balanced life which brings a biopsychosocial spiritual perspective (Tanhan, 2017, 2019).

The second main category is (b) influences of scholars, religious leaders, and philosophers (e.g., Al-Ghazali, Muhammed Rumi) introducing theoretical concepts based on Islamic sources about mental health. And the third (c) category is laity’s belief about mental health issues (e.g., studying too much, not getting married, deceased people affecting the living).

Common Cultural Treatments based on Islam

In addition to beliefs that follow from traditional conceptualizations of the influence of the spiritual realm on the natural realm, cultural treatments for mental health issues are often not aligned with the contemporary scientific/biomedical model, having their origins in primary Islamic sources. Common cultural treatments for mental illness include servanthood, prayer (salah), invocation (duaa), recitation of Quran (al-Ruqyah), Prophetic Medicine (Tibb-i Nabavi), remembrance of Allah (dhikr), charity (sadaqa), working with spiritual leaders, engaging in rituals, nightly prayers, joining spiritual conversation circles known as halaqas, focusing on diet, and muraqaba (i.e., one’s striving to examine their spiritual heart and striving to develop their insight), to name a few.

Muraqaba consists of different techniques including mushahada—observation, tasawwur—imagination (focused attention to imagine Allah/God, and holy people like prophets, and/or holy places), tafakkur—contemplation of creation, tadabbur—contemplation of Allah/God’s names/attributes, and muhasaba—self-assessment (Tanhan, 2019). Even though the trained counselor may find such beliefs antithetical to scientific research, numerous writers have stressed the importance of possessing knowledge of these cultural practices to effectively serve Muslim clients (Ahmed & Amer, 2012; Bagasra & Mackinem, 2014; Tanhan, 2019, 2020; Tanhan & Francisco, 2019). Given the influence of religiously derived understandings of mental health issues and the potential barriers that teachings about them create for Muslim’s, the authors sought to determine what the existing literature reviled about the challenges Muslims face when considering engagement in modern mental health treatment.

Literature Review Method

To conduct a thorough literature review, we searched a set of common key identifiers on research databases including Web of Science, PsycINFO, PubMed, ERIC, EBSCO, SCOPUS, and Education Full Text. The search terms included Muslim mental health, Muslims and mental health issues, Muslims’ psychosocial issues, Muslims’ psychology, Islamic psychology, and Islam and psychology. Inclusion criteria for identified articles were studies published in English and peer-reviewed journals grounded in research and with academic editors. All studies reviewed related to Muslim mental health were published between 2002 and 2020, thereby providing a comprehensive literature summary. We excluded conference papers, books, and technical reports. Research methodologies must have been empirical with quantitative, qualitative, mixed methods, or proposed conceptual frameworks.

Results

Through our systematic review, we identified 300 research articles which we reviewed. In the following lines, we have provided the results in four sections.

Literature Review Summary and Some Example Studies for the Main Factors

We read the identified research systematically and identified themes related to factors that impact Muslim’s consumption of mental health services. We reviewed the articles to identify a mental health concept, conceptual or theoretical foundation, and/or mental health approach related to Muslim mental health. See Table 1 for a summary of the articles reviewed.

Table 1.

Literature review summary and some example studies for the main factors

| Factor name and researchers who addressed the factor | |

|---|---|

|

Islam and Muslim Culture* a. Abu-Raiya & Ayten, 2019 b. Alhomaizi et al., 2018 c. Al-krenawi et al., 2009 d. Altalib et al., 2019 e Bagasra & Mackinem, 2014 f. Kpobi & Swartz, 2019 g Rothman & Coyle, 2018 h. Skinner, 2010 i. Sultan et al., 2019 |

j. Tanhan, 2019 k. Tanhan & Francisco, 2019 l. Tekke et al., 2017 *This is an overall factor affecting all other factors especially through cultural beliefs about mental health issues and services. The researchers, in general, did not measure this overall factor directly |

|

Cultural Beliefs about Mental Health Issues and Services a. Al-krenawi et al., 2009 b. Amri & Bemak, 2013 c. Bagasra & Mackinem, 2014 |

d. Ciftci et al., 2013 e. Haque et al., 2016 f. Kpobi & Swartz, 2019 g. Thomas et al., 2015 h. Youssef & Deane, 2006 |

|

Knowledge of Formal Mental Health Services a. Alhomaizi et al., 2018 b. Aloud & Rathur, 2009 c. Ciftci et al., 2013 |

d. Khan, 2006 e. Tanhan & Francisco, 2019 f. Tanhan & Strack, 2020 g. Youssef & Deane, 2006 |

|

Attitudes toward Seeking Formal Mental Health Services a. Alhomaizi et al., 2018 b.Ali & Milstein, 2012 c. Aloud & Rathur, 2009 d. Amri & Bemak, 2013 e. Cook-masaud & Wiggins, 2011 f. Khan, 2006 |

g. Soheilian & Inman, 2009 h. Tanhan & Francisco, 2019 i. Tanhan & Strack, 2020 j. Thomas et al., 2015 k. Tummala-Narra & Claudius, 2013 l. Youssef & Deane, 2006 |

|

Perceived Social Stigma toward Seeking Mental Health Services and/or Issues a. Abu-Ras, 2003 b. Ali & Milstein, G. 2012 c. Aloud & Rathur, 2009 d. Amri & Bemak, 2013 |

e .Ciftci et al., 2013 f. Cook-Masaud & Wiggins, 2011 g. Herzig et al., 2013 h. Phillips & Lauterbach, 2017 i. Soheilian & Inman, 2009 j. Tanhan, 2019 k. Tanhan & Francisco, 2019 |

|

Perceived Self-efficacy (Perceived Behavioral Control: PBC)* a. Amri & Bemak, 2013 b. Ciftci et al., 2013 c. Cook-Masaud & Wiggins, 2011 d. Khan, 2006 |

e. Tanhan, 2019 f. Tanhan & Francisco, 2019 g. Youssef & Deane, 2006 *Most of these researchers mentioned this factor indirectly without naming the factor |

|

Institutional/Professional Factors: Formal mental health institutions/professionals’ low competency level a. Ahmed et al., 2014 b. Ali & Milstein, 2012 c. Aloud & Rathur, 2009 d. Amri & Bemak, 2013 e. Bagasra & Mackinem, 2014 f. Ciftci et al., 2013 g. Cook-Masaud & Wiggins, 2011 |

h. Goforth et al., 2014 i. Khan, 2006 j. Nadal et al., 2012 k. Soheilian & Inman, 2009 l. Tanhan, 2019 m. anhan & Francisco, 2019 n. Tanhan & Strack, 2020 o. Thomas et al., 2015 p. Youssef & Deane, 2006 |

|

Institutional/Professional Factors: Need for psychological (theoretical frameworks, psychotherapy) modals based on Islam to explain human nature* a. Abu-Raiya, 2015 b. Hamjah & Akhir, 2014 c. Kaplick et al., 2019 d. Keshavarzi & Haque, 2013 e. Rothman & Coyle, 2018 |

f. Tanhan, 2019 g. Tanhan & Francisco, 2019 h. Tanhan & Strack, 2020 *Many other researchers (e.g., Tanhan & Francisco, 2019) elaborated on the need for the modals based on perspective in Islam. However, the ones above provided some well-grounded modals based on perspective in Islam |

|

Use of Traditional Resources a. Amri & Bemak, 2013 b. Bektas et al., 2009 c. Bagasra & Mackinem, 2014 d. Chen et al., 2015 e. Green et al., 2019 f. Hamjah & Akhir, 2014 g. Haque et al., 2016 h. Herzig et al., 2013 i. Khan, 2006 j. Kpobi & Swartz, 2019 |

k.Nadal et al., 2012 l. Schlosser et al., 2009 m. Tanhan, 2019 n. Tanhan & Francisco, 2019 o. Tanhan & Strack, 2020 p. Thomas et al., 2015 q. Tobah, 2018 r. Tummala-Narra & Claudius, 2013 s. Vasegh & Ardestani, 2018 t. Youssef & Deane, 2006 |

|

Acculturation a. Amri & Bemak, 2013 b. Aprahamian et al., 2011 c. Bektas et al., 2009 d. Chen et al., 2015 |

e. Goforth et al., 2014 f. Tanhan & Francisco, 2019 g. Tanhan & Strack, 2020 h. Tummala-Narra & Claudius, 2013 |

|

Control Variables a. Education level: Ali & Milstein, 2012; Bagasra & Mackinem, 2014; Tanhan & Francisco, 2019 b. Sex: Alhomaizi et al., 2018; Amri & Bemak, 2013; Ciftci et al., 2013; Youssef & Deane, 2006 c. Use of mental health in the past: Ali & Milstein, 2012; Tanhan & Strack, 2020 |

e. Economic factors: Aloud & Rathur, 2009; Amri & Bemak, 2013; Cook-Masaud & Wiggins, 2011 f. Length of stay in Western countries: Aloud & Rathur, 2009; Goforth, 2014 g. Age: Goforth, 2014; Lowe et al., 2018 |

|

Intention toward Seeking Formal Mental Health Services a. Ali & Milstein, 2012 b. Amri & Bemak, 2013 c. Kelly et al., 1996 |

d. Khan, 2006 e. Tanhan, 2019 f. Tanhan & Francisco, 2019 g. Youssef & Deane, 2006 |

|

Behavior: Actual Use of Mental Health Services at Individual, Group, or Community Level a. Al-Thani & Moore, 2012 b. Dwairy, 2009 |

c. Hamdan, 2008 d. Kaplan et al., 2014 e. Tanhan & Francisco, 2019 f. Tanhan & Strack, 2020 |

We reviewed 300 peer-reviewed manuscripts published in English from 2002 to 2020, which may have led to the exclusion of some other resources (e.g., books, other work published in other languages). We have provided some examples of 300 manuscripts in the table

Main Researchers who Utilized a Theoretical Framework, Theory, or Modal

Of the research reviewed, only a few manuscripts (see Table 2) included a clear conceptual and/or theoretical framework to design the research (e.g.,Manejwala & Abu-Ras, 2019; Phillips & Lauterbach, 2017; Sultan et al., 2019; Tanhan, 2019; Tanhan & Francisco, 2019; Tanhan & Strack, 2020).

Table 2.

Some of the main researchers who utilized a theoretical framework, theory, or a modal to design their research and clearly named the framework

| Authors, Year, and Manuscript’s Name (From the Most Recent Published Manuscript to the Previously Published Manuscript) |

Theoretical Framework, Theory, or Modal | Visual Concept Map | Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tanhan & Strack, 2020. Online photovoice to explore and advocate for Muslim biopsychosocial spiritual wellbeing and issues: Ecological systems theory and ally development. Current Psychology | Ecological systems theory and ally development | Not available | Qualitative |

| Tanhan & Francisco, 2019. Muslims and mental health concerns: A social ecological model perspective. Journal of Community Psychology | Social ecological theory and ally development | Available | Mixed |

| Manejwala & Abu-Ras, 2019. Microaggressions on the university campus and the undergraduate experiences of Muslim south Asian women. Journal of Muslim Mental Health |

Moustakas’s (1994) transcendental phenomenological approach |

Not available | Qualitative |

| Yildiz et al., 2019. Adaptation of a Muslim spiritual attachment scale (God attachment) for Turkish Muslims: a validity and reliability study. Mental Health, Religion & Culture | Theory of attachment | Not available | Quantitative |

| Tanhan, 2019. Acceptance and commitment therapy with ecological systems theory: addressing Muslim mental health issues and wellbeing. Journal of Positive Psychology and Wellbeing | Acceptance and commitment therapy with ecological systems theory | Not available | Qualitative |

|

Sultan et al., 2019. Moderating effects of personality traits in relationship between religious practices and mental health of university students. Journal of Religion and Health |

Five-factor modal | Not available | Quantitative |

| Alhomaizi et al., 2018. An exploration of the help-seeking behaviors of Arab-Muslims in the US: a socio-ecological approach. Journal of Muslim Mental Health |

A socio-ecological approach |

Not available | Qualitative |

| Phillips & Lauterbach, 2017. American Muslim immigrant mental health: The role of racism and mental health stigma. Journal of Muslim Mental Health | Bronfenbrenner’s (1977) ecological systems theory | Not available | Qualitative |

| Martin, 2015. Perceived discrimination of Muslims in health care. Journal of Muslim Mental Health | Transcultural caring dynamics in nursing and health care model | Not available | Quantitative |

| Thomas et al., 2015. Conceptualising mental health in the United Arab Emirates: The perspective of traditional healers. Mental Health, Religion & Culture | Cultural relativism | Not available | Qualitative |

| Bhattacharyya et al., 2014. Social justice beyond the classroom: Responding to the marathon bombing’s Islamophobic aftermath. The Counseling Psychologist | Ally development | Not available | Qualitative |

| Amri & Bemak, 2013. Mental health help-seeking behaviors of Muslim immigrants in the United States: overcoming social stigma and cultural mistrust. Journal of Muslim Mental Health | Multi-phase model of psychotherapy, social justice and human rights | Not available | Qualitative |

| Nadal et al., 2012. Subtle and overt forms of Islamophobia: microaggressions toward Muslim Americans. Journal of Muslim Mental Health | Religious microaggressions taxonomy | Not available | Qualitative |

| Tummala-Narra & Claudius, 2013. A qualitative examination of Muslim graduate international students’ experiences in the United States. International Perspectives in Psychology: Research, Practice, Consultation | Grounded theory | Not available | Qualitative |

| Aloud & Rathur, 2009. Factors affecting attitudes toward seeking and using formal mental health and psychological services among Arab Muslim populations. Journal of Muslim Mental Health |

Factors affecting Arab Muslim attitudes toward formal mental health services, |

Not available | Quantitative |

| Hamdan, 2008. Cognitive restructuring: An Islamic perspective. Journal of Muslim Mental Health | Cognitive restructuring, a particular form of cognitive therapy | Not available | Qualitative |

Note We only considered peer-reviewed manuscripts published in English from 2002 to 2020, which may have led to the exclusion of some other resources. Full details about each manuscript is provided in the reference list

Explaining Mental Health through Modals or Frameworks based on Perspectives in Islam

There are many researchers who strived to adapt or tailor mainstream approaches to serve Muslims (Tanhan, 2019). For example, Tanhan (2019) explained from a theoretical and contextually sensitive perspective how Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) can be used with SEM to serve Muslims. However, different from adapting and tailoring, how Islam explains human wellbeing and psychopathology is an area that gets much more attention in Muslim mental health literature (Tanhan, 2019).

Agilkaya-Şahin (2019) elaborated on three overall approaches that have shaped developments in this area of Islamic psychology. The first one is filter approach by Badri (2020), the second one is Skinner’s Islamic psychology approach, which is an extension of the filter approach and grounds on early Muslim philosophers’ particularly Sufis’ ideas, and Hussain’s comparative approach, which stresses striving to find equivalents of Western theories in Islam and Muslim culture rather than criticizing Western theories. These overall approaches do not provide a testable modal or theoretical framework.

Different from these general approaches, we identified four manuscripts (see Table 3) that included a theoretical framework (modal) to explain how Islam explains human psychology and mental health (Abu-Raiya, 2015; Hamjah & Akhir, 2014; Keshavarzi & Haque, 2013; Rothman & Coyle, 2018). In the following table, we have provided some of the researchers focused on how Islam explains human psychology and mental health. These modals or theoretical frameworks are more practical to be tested for research and services.

Table 3.

The researchers who developed a modal or theoretical framework to explain human psychology or mental health based on perspectives in Islam

| Authors, Year, and Manuscript’ and Journal’s Name | Theoretical Framework (Modal) | Concepts Included in the Theoretical Framework or Modal | Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rothman & Coyle, 2018. Toward a framework for Islamic psychology and psychotherapy: an Islamic model of the soul. Journal of Religion and Health | An Islamic model of the soul, grounded theory | Four main categories: Nature of the soul, structure of the soul, stages of the soul, and development of the soul. Each category includes some subcategories/concepts | Qualitative |

| Hamjah & Akhir, 2014. Islamic approach in counseling. Journal of Religion and Health | Islamic approach in counseling | Three aspects: Aqidah (faith), Ibadah, and akhlaq | Qualitative |

| Keshavarzi & Haque, 2013. Outlining a psychotherapy model for enhancing Muslim mental health within an Islamic context. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion | Based on Islam and Al-Ghazali’s conceptualization |

Four main concepts: Aql—cognition; Nafs—acquired automatic tendencies of the human being; Ruh (spirit)—experiential, transcendental elements; Qalb—heart, the holistic consolidation and expression of all three elements |

Qualitative |

| Abu-Raiya, 2012. Toward a systematic Qura’nic theory of personality. Mental Health, Religion & Culture |

Qura’nic theory of personality |

Eight main interrelated concepts: nafs (psyche), nafs ammarah besoa’ (evil-commanding psyche), alnafs al-lawammah (the reproachful psyche), roh (spirit), a’ql (intellect), qalb (heart), al-nafs al-mutmainnah (the serene psyche), and al-nafs al-marid’a (the sick psyche) | Qualitative |

We only considered peer-reviewed manuscripts published in English from 2002 to 2020, which may have led to the exclusion of some other resources. Full details about each manuscript is provided in the reference list. We listed references based on the most recent published manuscript to the previously published manuscript.

Concept Map

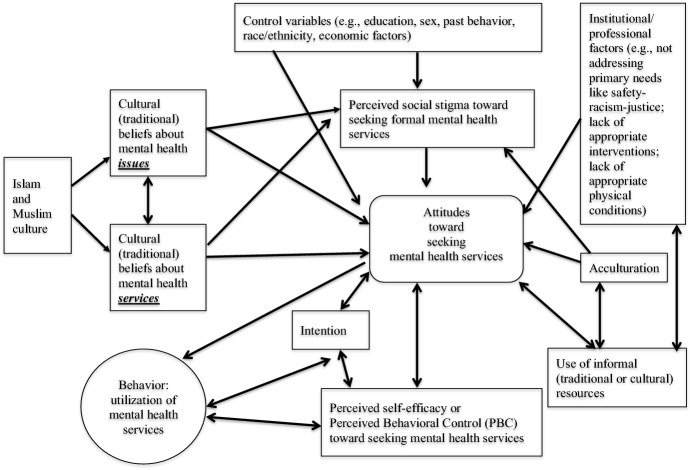

Based on the review of 300 manuscripts and the factors identified in Table 1, we created a proposed concept map to represent the range of factors that impact Muslims’ consumption of mental health services (see Fig. 1). We streamlined the figure to demonstrate the main relationships among the factors. The most commonly included model to explain Muslims help-seeking behaviors was Bronfenbrenner’s Social Ecological Model (SEM, Tanhan & Francisco, 2019) also known as Ecological Systems Theory (EST, Tanhan, 2019). On occasion, the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) and/or Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) was the theoretical framework utilized to explain the phenomena under investigation.

Fig. 1.

The Concept Map: Factors Impacting Muslims Mental Health Service Consumption. Note This final proposed concept map did not include all factors that emerged in the first version of the map, which included more concepts. We included a factor in the final concept map when the factor was included and addressed directly or indirectly in at least three or four peer-reviewed articles

Eleven factors emerged based on the extant literature. These were (a) cultural beliefs about mental health issues, (b) cultural beliefs about mental health services, (c) control variables (education, sex, past behavior, race/ethnicity, economic factors), (d) perceived social stigma, (e) attitudes toward seeking services, (f) intention, (g) perceived self-efficacy, (h) institutional professional factors, (i) acculturation, (j) use of informal resources, and (k) behavior- utilization of services.

Concept Map and Theoretical Framework in Research

The majority of researchers reviewed failed to employ a clear theoretical framework to explain the underutilization of mental health services. Nevertheless, some researchers have stressed the importance of having such tools to organize, ground, and move both research and clinical practice forward with cultural sensitivity (Ali & Milstein, 2012; Al-shannaq & Aldalaykeh, 2021; Haque, 2004; Tanhan, 2019; Tanhan & Francisco, 2019). Without a well-established framework, it can be difficult for investigators to improve research and practice based on previous research results (Flanagan & Kaufman, 2004; Ravitch & Riggan, 2012; Tanhan, 2019, 2020; Tanhan et al., 2020a, 2020b).

The preponderance of literature reviewed emphasized the need for an approach that considers both individual and contextual factors related to service consumption. Subsequently, the use of Theory of Planned Behavior/Theory of Reasoned Action (TPB/TRA) is employed to provide an individual perspective, while SEM situates TPB/TRA within a contextual milieu. TPB/TRA is a single lens given that TPB and TRA are derived from the same theories with only subtle differences. Furthermore, in the context of scientific discussions, the authors used TPB/TRA as one theory to credit both theories.

Theoretical Foundations: Individual and Contextual Factors to Understand Muslim Mental Health

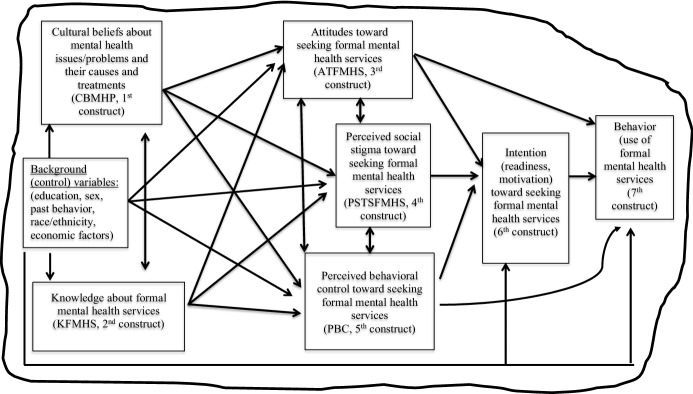

Individual and contextual factors must be considered when studying human psychology so that a comprehensive approach is followed (Bronfenbrenner, 1977; Tanhan & Francisco, 2019). Human beings have biopsychosocial, spiritual, and economic aspects and live within a context that has sub-related-dynamic systems (e.g., micro, meso, exosystem; Bronfenbrenner, 1977; Tanhan, 2019, 2020). Subsequently, we utilized TPB/TRA and Social Ecological Model (SEM) to select the most salient factors from the proposed concept map and to formulate the proposed contextual theoretical framework (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The Proposed Contextual Theoretical (Conceptual) Framework: Muslims’ Approach to Use of Mental Health Services based on Theory of Planned Behavior and Theory of Reasoned Action (TPB/TRA) in the Context of Social Ecological Model (SEM). Note We drew the theoretical (conceptual) framework based on the Theory of Planned Behavior/Theory of Reasoned Action (TPB/TRA), Bronfenbrenner’s Social Ecological Model (SEM), and the review of Muslim mental health literature (the concept map)

We selected TPB/TRA and SEM as theoretical foundations because previous researchers from counseling (Mackenzie et al., 2004; Romano & Netland, 2008), public health, and Muslim mental health (Aloud & Rathur, 2009; Amri & Bemak, 2013; Tanhan, 2017) called for the use of TPB/TRA to examine individuals’ approach to the use of mental health services. The primary constructs of TPB/TRA are similar to the most commonly examined concepts in Muslim mental health (e.g., stigma, attitudes). Additionally, the concept of intention, which is a core construct in TPB/TRA, is central to Islam and yet is largely understudied in Muslim mental health literature. The use of a comprehensive approach for understanding Muslims mental health aligns well with the selection of SEM as a lens in which to situate TPB/TRA.

TPB/TRA and its Place in Mental Health and Muslim Mental Health Literature

Originating from the first version of TRA, TPB is a theory focusing on predicting an individual’s voluntary (volitional) action (behavior) about possible choices by focusing on four main constructs; namely attitude, social norm, Perceived Behavioral Control (PBC meaning perceived self-efficacy), and intention. TPB emerged from the early version of TRA (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975) after Ajzen (2006) expanded TRA by adding PBC as an additional construct. Fishbein and Ajzen (2010) later expanded the first version of TRA so that the model conceptually and visually includes the PBC construct, background factors (e.g., education, culture, knowledge, family, economic situation), and how these factors affect the main constructs (attitudes, social stigma, PBC, and intention) to predict or explain behavior. Although researchers use different names (TPB, TRA, or TPB/TRA), the models are nearly identical with only minor differences; therefore, Tanhan (2017) used the theories together as a single theory, TPB/TRA for understanding Muslims mental health services.

Researchers have suggested the use of TPB/TRA in counseling for research, practice, and teaching (e.g., Romano & Netland, 2008; Tanhan, 2017). Researchers have utilized TPB/TRA in psychology and health disciplines to study a variety of topics (e.g., Ajzen, 2006; Ajzen et al., 2011; Fishbein & Ajzen, 2010; Morrison et al., 2002). And researchers have recommended the application of TPB/TRA to the mental health professions (Mackenzie et al., 2004).

Importance of TPB/TRA

There are several reasons that TPB/TRA is important. First and foremost, it has been utilized in many different disciplines with a range of topics and provided significant results. Second is that it includes crucial constructs and a clear model, rather than so many constructs that it is empirically difficult to test. Third, the theory provides detailed information regarding how to improve instruments to measure each construct related to different topics.

Fourth, generally the theory does not consider background factors (e.g., race and cultural beliefs) as important as the primary constructs (e.g., attitudes). However, the theory places them in the model and calls for empirical testing, especially when the context is new for participants, which is the case for Muslims’ use of mental health services. Fifth, the lack of theories to explain utilization of mental health services (e.g., counseling) both for Muslims and non-Muslims. Sixth, the theory is unique in that it includes intention and Perceived Behavioral Control (PBC, meaning perceived self-efficacy) as two most important constructs to explain or predict behavior. Finally, in Islam, the role of intention is so crucial that it precedes one’s behavior. Therefore, TPB/TRA is a useful theoretical lens to create a framework to understand how Muslim’s approach to the utilization of mental health services. Relatedly the model provides concrete constructs and possible relationships that can be empirically tested, while SEM provides a contextual approach within which TPB/TRA can be understood.

Researchers’ Support and Criticism for TPB/TRA

Researchers (e.g., Sniehotta et al., 2014) acknowledge the contribution of the theory for the past 30 years that the theory has shaped psychological theorizing and behavioral theories from a three-factor model to a more complex model (TPB/TRA). Researchers stressed the theory especially for bringing two important new constructs including PBC and intention (McEachan et al., 2011; Tanhan, 2017) to the discussion of predicting and changing behaviors.

In terms of criticisms, McEachan et al. (2011) called for the retirement of TPB/TRA because of the following reasons. First, whether the scales aligned with TPB/TRA to measure constructs build some concepts in participants’ minds that were not there before and therefore the theory cannot be falsified and its validity could be questioned (Ogden, 2003). Second, the theory is focused on rational reasoning and excludes unconscious influences on behavior (Sheeran et al., 2013). Third, the theory is not fully explaining the role of emotions on behavior (Conner et al., 2013). Fourth, self-regulatory measures like planning regularly predict behavior more than TPB/TRA (Carraro & Gaudreau, 2013). Fifth, the research results showed that TPB/TRA was more predictive when the sample for the studies were young, fit, and affluent and for self-reported behavior over a short time (McEachan et al., 2011). Sixth, the issue with how to explain individuals who set an intention about a behavior (considering it as one of the most important constructs) and yet do not act on it (Orbell & Sheeran, 1998).

And finally, the lack of robust experimental designs, which led to the use of extended/modified models of TPB/TRA models (Sniehotta et al., 2014). Among the most powerful critiques is from Sniehotta et al. (2014) who argued that the theory did not help to understand how cognitions change nor how to devise interventions to influence constructs (e.g., attitudes, subjective norms, behaviors), leading to the call to abandon TPB/TRA and the creation of more effective models of predicting and changing behavior.

Response to Criticisms

Some of these criticisms might be accurate for some studies because at its basic line TPB/TRA offers a model that is empirical. First and foremost, for the current study, most of the critiques mentioned above were not coming from mental health. There is a lack of empirical studies in terms of TPB/TRA and mental health, which makes the proposed theoretical framework important. In addition, Ajzen (2015) responded to earlier critiques by pointing out that TPB/TRA is not static as researchers criticized it for. He called researchers to read the theory in greater depth. He recommended reading the work of Fishbein and Ajzen (2010) rather than relying on the oversimplified diagram. For example, there is no connection from behavior construct to cognitions in the TPB/TRA diagram yet it is explained in the text that behaviors also affect cognitions. It is important to note that in the first version of TRA there were loops from behaviors to cognitions that showed the dynamic relationship (Tanhan, 2017).

Ajzen (2015) explained how some of the same researchers, who called to terminate the theory, conducted research and falsified aspects of the theory. And Ajzen asserted that this reveals that the theory is not just common-sense and is open to be falsified. For the discussion about the lack of intention predicting a behavior, Ajzen stated that events (e.g., unanticipated obstacles) happening between assessment of intentions and observation of behaviors. He reported that when a situation is real or hypothetical then intentions and beliefs might be different. This means contextual factors (e.g., beliefs about exercising might be different in the morning when a person is relaxed and at night after work) constantly affect people’s decision-making process (Tanhan, 2017). He also stated that the main constructs of the theory (e.g., attitudes) in general are measured with three or four items that could be difficult to capture all aspects of constructs. This might somewhat affect validity and reliability and lead researchers to expand the theory and include some other predictors/constructs, which was another criticism. Ajzen (2015) explained that this is normal to theory, as PBC was added to the original theory to include other predictors.

Ajzen and Sheikh (2013) explained how a second version of one of the main constructs (e.g., attitudes toward not performing a behavior as a first construct in addition to a second one as attitudes toward performing the behavior) could improve explaining variance in intention. In terms of critiques that theory lacks the consideration of affect and is too rational, Ajzen (2015) explained how all studies examined anticipated affect (e.g., guilt, regret) in relation to not performing the related behavior. However, he reported that when a measure (e.g., a second attitude construct) toward not performing the behavior was added to the equation, the role of anticipated effect was no longer there to explain the variance, and the newly added second construct explained the variance.

It is important to bear in mind that within TPB/TRA, the role of affect is included (Tanhan, 2017) under the individual category (e.g., emotion, values, past behavior) under background factors (individual, social, information; see the theory figure in Fishbein & Ajzen, 2010, pp 22 for more details). Affect is not a main construct, and yet being included as a subcategory makes the theory dynamic and rebuts the critiques that the theory is static and views human beings as only acting from a rationale perspective. In this way, any researcher can test affect’s role as a main construct in the context of TPB/TRA. The authors explained both how the theory is empirical and how the importance of each predictor can vary from one study to another based on their samples. This also reminds a researcher of the role of contextual factors. In regard to the critiques that the theory is not helpful for explaining how cognitions change and how to change constructs to devise effective interventions, Ajzen (2015) explained how the theory is not about behavior change rather it is meant to explain and predict one’s intentions and behaviors.

The theory could be utilized as a framework to design effective behavior change interventions by focusing on main constructs (e.g., beliefs, attitudes, subjective perceived norms, PBC, intentions, behaviors). Researchers can focus on the dynamic relationships among these main constructs through understanding the theory and then developing their scales because the theory does not provide specific means, strategies, or techniques overall for a specific topic of interest (Fishbein & Ajzen, 2010; Tanhan, 2017). Fishbein and Ajzen (2010) have two chapters in their book where they have explained in detail how to achieve effective interventions and changes in intention and behaviors. They provided detailed examples and explanations for different specific situations (e.g., testicular self-examination, using public transportation, HIV/AIDS prevention). One of the main explanations for how change occurs in intention and behavior is changing the underlying and accessible three beliefs (i.e., behavioral, normative, and control) that shape the three main constructs (attitudes toward behaviors, subjective perceived norms, PBC).

According to the theory, if these underlying beliefs are changed then the change will affect the three main constructs and through them intention and behavior will be changed. However, the theory keeps other factors’ (e.g., actual control variables like environmental factors or skills) effect in mind (Ajzen, 2015). This explanation, from a mental health perspective, is very similar to cognitive therapy approaches that stress how one’s cognitions (underlying core beliefs) might affect one’s thought processes and other behaviors. Ajzen explained that the correlation among the constructs is not perfect. Therefore, a large amount of change in underlying beliefs creates little change in the main three constructs (attitudes toward behaviors, subjective perceived norms, perceived behavioral control). This large amount of change creates even less desired change in intention and behavior. This means that a large and well-considered change in beliefs is needed for a sizable amount of desired change in intention and behavior.

Ajzen briefly explained in six steps how the theory could be utilized as a conceptual framework to devise a general intervention about to carry out a favorable intention. In response to the critiques that people with favorable intentions do not act on the related behavior, Ajzen (2015) provided four steps to explain the reasons behind that and how effective interventions could be devised accordingly in such situations. Finally, Ajzen also cited some empirical studies done by others who used the theory as a theoretical framework to design and evaluate the effects of an intervention that produced encouraging results. In conclusion, Ajzen (2015) responded to most of the critiques. He stated that researchers need to understand TPB/TRA and conduct research thoroughly in order to decide whether the theory should be retired. He explained how the researcher could come with more effective theories as long as they construct more rigorous theories and come with more empirical results that support them.

Our Current Proposed Theoretical Framework Closes an Important Gap

Based on all these discussions and the fact that there is a lack of research in terms of the use of TPB/TRA in mental health, the current study and the proposed theoretical framework meet an important gap in the literature that carries mental health research and practice forward. TPB/TRA included important contextual factors (e.g., background, knowledge, culture, education, information) and Fishbein and Ajzen (2010) constantly yet between lines called for others to pay attention to such factors. However, they have never mentioned Bronfenbrenner’s Social Ecological Model (SEM) or any other such contextual perspectives. They paid more attention to individual/intrapersonal dynamics rather than the larger context.

Based on mentioned above, in order to give credits to SEM, which has affected mental health and many other disciplines in depth and as a response to merely individual perspectives, the inclusion of SEM is important. Additionally, almost all the researchers in the Muslim mental health literature stressed repeatedly the importance of paying attention to the contextual factors even though just few literally mentioned or explained how to use SEM (e.g., Alhomaizi et al., 2018; Martin, 2015; Tanhan, 2019; Tanhan & Francisco, 2019; Tanhan & Strack, 2020). The researchers stressed the necessity of including all aspects (e.g., attitudes, stigma, sex, culture, religion, knowledge, institutional factors, policies, global issues, and community factors) to understand Muslims’ approach toward formal mental health issues and services.

In addition to the Muslim mental health literature, the researchers in the public health discipline paid attention to contextual factors and SEM more than any other models or theories to understand and address many different health issues (Orsini et al., 2019; Tanhan & Francisco, 2019). Therefore, using SEM in the proposed model will fill an important gap in the Muslim mental health literature. For example, a Muslim might consider the use of counseling at an individual level and have positive attitudes toward counseling and yet could not feel safe to utilize because of political climate. In this case, it is needed to consider both individual and contextual factors so that the proposed theoretical framework is grounded in both research and practice.

Social Ecological Model (SEM) in Counseling and Muslim Mental Health Literature

SEM, also known as human ecological theory or just Ecological Systems Theory (EST), was proposed by Urie Bronfenbrenner in 1970 as a conceptual model to take the environmental conditions into account rather than just intrapersonal/individual and genetic factors (Bronfenbrenner, 1977). He improved the model from 1970 until 2005 (Tanhan, 2019, 2020). The model was a kind of reaction to individual approaches in psychology or other fields (e.g., medicine, public health, education) that focused solely on individuals isolated from their contexts (McLeroy et al., 1988; Tanhan, 2019; Tanhan & Francisco, 2019).

Bronfenbrenner (1977) stressed the importance of seeing the person within their contexts and all the constant dynamic relationships in those contexts. SEM consists of five levels. He explained each of the levels (e.g., microsystem, mesosystem) and how to use the model for the experimental studies. The first four levels are microsystem (including the individual themselves), mesosystem, exosystem, and macrosystem (Bronfenbrenner, 1977). Bronfenbrenner and Evans (2000) added a fifth level called chronosystem to indicate how chronological events (e.g., wars, economic crisis, endemic, pandemic) affect persons and communities across levels. According to the model, all these levels are interrelated and have dynamic relationships with one another, which means a change in one affects the others as well. A thorough understanding of a person is possible if one understands the individual within these contexts rather than isolated from their circumstances (Tanhan, 2019, 2020; Tanhan & Francisco, 2019).

The model has been used in various studies including psychology, public health, mental health, medicine, education, and social work (e.g., Orsini et al., 2019). McLeroy et al. (1988) explained how some researchers criticize individual approaches from an SEM perspective because the individual approaches neglect the role of other contextual aspects (e.g., social, global) and just focus on personal lifestyle. Such individual approaches can create victim-blaming situations (Freire, 1972; Tanhan & Francisco, 2019; Tanhan & Strack, 2020) where the victims are disserved and blamed for the issues they face, creating important ethical dilemmas. Therefore, some researchers explained how SEM could be utilized to focus both on individual and environmental factors for different disciplines including health (McLeroy et al., 1988; Orsini et al., 2019; Tanhan et al., 2020a, 2020b), education (Arslan & Tanhan, 2019; Arslan et al., , 2020, 2021; Doyumğaç et al., 2021; Subasi et al., 2021; Tümkaya et al., 2021), and mental health (Tanhan, 2019, 2020; Tanhan et al., 2021a, 2021b). They used SEM and noted that many researchers combined some individual theories with SEM to study their topic of interest.

To summarize, many researchers have utilized SEM to explain how individuals, groups, and communities function within their contexts at individual, microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, and macrosystem levels and the constant interactions among these levels for accurate and effective assessment, intervention, and evaluation. In this way, the researchers and practitioners can increase the quality of health for all by improving the conditions at all levels simultaneously.

Considering all these, the inclusion of SEM is important as a lens to take contextual conditions into account in addition to intrapersonal and genetic factors (Bronfenbrenner, 1977; McLeroy et al., 1988; Tanhan, 2019, 2020). SEM consists of five levels including microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, macrosystem, and chronosystem. Within the model, all levels are interrelated and considered together; otherwise, the risk of victim blaming is increased (Freire, 1972; Prilleltensky, 2012; Tanhan & Francisco, 2019; Tanhan & Strack, 2020). They addressed how SEM is used in different professions like psychology, public health, medicine, and education. However, people, including key people like the ones providing health services, can be manipulated by exploitative systems and so they forget about the contextual factors and may end up harming people (Tanhan & Francisco, 2019). Paying attention to contexts is also stressed in counseling literature (American Counseling Association [ACA], 2014; Arredondo et al., 2008; Tanhan, 2019, 2020). The use of SEM is important because many researchers in the Muslim mental health literature stressed the importance of paying attention to contextual factors though just few explained the model (e.g., Alhomaizi et al., 2013; Martin, 2015; Tanhan, 2019, 2020; Tanhan & Francisco, 2019).

Considering TPB/TRA and SEM Together

Considering all mentioned, TPB/TRA and SEM together is important so that TPB/TRA provides a more individual perspective and a model that could be empirically tested providing concrete constructs. And SEM provides a more contextual and comprehensive perspective so that mental health research and practices are improved and applied appropriately in culturally, contextually, and spiritually sensitive ways. In this way, mental health professionals can strive more to stay away from an acontextual aspect that might cause blaming Muslims for biopsychosocial, spiritual, and economic issues they face. Furthermore, it is also crucial to give a respond to previous calls that some previous researchers (e.g., Tanhan, 2017) both from Muslim mental health, counseling, and public health called for the use of TPB/TRA and SEM (alone or together) to study Muslims seeking mental health services.

In the following section, we elaborated on the concept map (Fig. 1) based on a thorough literature review in order to provide more grounded information about the proposed theoretical framework that combines TPB/TRA and SEM, its constructs, and the process of how each construct was selected for inclusion.

Factors Impacting Mental Health Service Consumption

The review of literature conducted led to the conclusion that Muslims face a few very real obstacles when pursuing mental health services. Some are internalized perceptions based in Muslim culture while others are a result of environmental factors that make pursuing mental care difficult for some individuals. The literature review of 300 articles provided an overview of 11 interacting factors that contribute to the unique challenges faced by this population. To better serve Muslims, researchers must consider how the following 11 factors contribute to the underutilization of the services for the Muslims. However, first it may be beneficial to explain Islam and Muslim culture, as they affect almost all the other factors especially through the first two factors.

Islam and Muslim Culture- an Overall Resource that Affects almost all Aspects of Life

Multiple researchers in the Muslim mental health literature argued that Muslims’ faith and culture directly impact almost all aspects of life including how Muslims’ approach to mental health issues and services (e.g., Abu-Raiya & Ayten, 2019; Altalib et al., 2019; Sultan et al., 2019; Tanhan, 2019; Tanhan & Francisco, 2019). Islam, first and foremost, stresses mental stability (health) as a prerequisite for all other requirements (e.g., even for becoming Muslim, pray, marriage); such a stress is not giving to other aspects like physical health (Tanhan, 2019). This shows that mental health has a central role in Islam.

Islam shapes the various cultures in which Muslims live, and is often the primary force impacting the lives of Muslims, including their approach to understanding and consuming mental health services. Muslims are spread all over the world and derive from multiple subcultures. However, it is possible to identify core characteristics that originates from primary and secondary sources in Islam though such characteristics are affected by contextual factors based on specific subcultures (Tanhan, 2019). Subsequently, this literature review focused on core cultural beliefs from primary and secondary sources of Islam because with the full awareness one’s culture and religion may either facilitate or restrict one’s way of life (Tanhan, 2019, 2020; Tanhan & Strack, 2020; Wiggins, 2011; Young & Cashwell, 2011, 2016.

The literature on Islam and Muslim mental health overall stressed Islam directly affects Muslims’ culture and so their mental health; therefore, it is need to pay attention to Islam’s primary and secondary sources specifically rather than subcultural or minor differences among Muslims. Altalib and others (2019) found similar results based on their meta-analysis of 16 years on global Muslim mental health. Therefore, it is important that mental health professionals pay more attention to Islam as an overall factor than other factors (e.g., country, education, sex) when providing services or conducting research with Muslims who indicate or openly state their religion or spirituality. The professionals can create more space to understand how Islam has affected their clients’ specific culture and subcultures when the professionals acknowledge the role of Islam as an overall resource, when it is appropriate to do so. The Muslims may be more likely to collaborate with the professionals if they articulate how Islam stresses mental stability and that it is a prerequisite for all other requirements (even to become Muslim, pray, having pilgrimage) for a Muslim and others.

If a person is not mentally stable, from an Islamic law perspective, the society or administration cannot question the person for their beliefs or actions. The administration, society, or family is in charge of facilitating life for the person with mental health issues in a humanistic way without judging or punishing them. This might also explain the fact that many people with mental instability (yet who have not dangerous actions) wander in social life and visit places (e.g., shopping centers, cafes, houses) randomly and are treated as the best guests in some parts of many countries with majority Muslims (e.g., Turkey, Iran, Syria, Indonesia, Somalia). In these countries, society sees such people with mental health issues as part of regular life and does not institutionalize and isolate them from life, and Islam also stresses this humanist approach (primary and secondary sources of Islam, Tanhan, 2019; Tanhan & Francisco, 2019). The professionals need to know many Muslims may have forgotten how Islam stresses mental health; therefore, the professional may need to elaborate on this aspect overall. Below we have elaborated upon the 11 factors in detail.

Cultural Beliefs About Mental Health Issues—First Factor

Cultural beliefs related to mental health consist of beliefs that emerge from either religious belief and/or culture related to the cause and treatment of mental issues (Tanhan, 2017). Traditional Islamic beliefs regarding the causes of mental illness are supernatural, and they may originate from theological bases and have the capacity to cause symptoms of mental health illness when interpreted in a wrong way. Therefore, cultural beliefs include aspects, such as the effect of supernatural entities. A Muslim client may believe these entities are causing or exacerbating his or her mental health issues.

These beliefs might originate from Islamic teaching and traditions (e.g., jinn, evil eye) or any other cultural (not necessarily Islamic resources) elements like the idea that deceased people can harm or benefit people. Even though such beliefs do not fit within the scientific biomedical model of mental issues and their treatments, such beliefs can be powerful drivers for some Muslim clients. Mental health professionals need to keep in mind that Muslims’ subcultures carry elements from other main religions (e.g., Christianity, Judaism, Hinduism, Buddhism, diverse African religions) and other cultural traditions. The primary resources in Islam stressed borrowing from other cultures when it fits with the spirit of Islam.

Researchers argued that cultural beliefs lead many Muslims to hold a negative disposition toward formal mental health services, which drives the overuse of informal cultural resources to address these issues (Amri & Bemak, 2013; Ciftci et al., 2013). By contrast, other researchers have reported that Muslims may hold both cultural beliefs and contemporary biomedical perspective about the causes and treatments of mental issues (Bagasra & Mackinem, 2014; Tanhan, 2017; Yıldırım & Maltby, 2021). Thomas et al. (2015) reported that key individuals (e.g., Mutawa, imam) in Muslim communities sometimes collaborated with mental health providers to assist in the integration of biomedical interventions with traditional cultural beliefs. Other researchers (e.g., Tanhan, 2019; Tanhan & Francisco, 2019; Tanhan & Strack, 2020; Youssef & Deane, 2006) suggested that such collaborations are need and rarely occur.

Most of these researchers in Muslim mental health found cultural beliefs affect Muslims to have negative approach toward mental health issues and formal mental health services. Many Muslims believe mental health issues are caused by supernatural entities (e.g., jinns, spirits, evil eye) and therefore are seeking help from resources stressing these aspects rather than a holistic evidence-based biopsychosocial spiritual approach. Therefore, it is important for formal mental health professionals to consider these cultural perspectives and be willing to attend to their clients in an emphatic way to create space for a more holistic approach rather than a merely biomedical perspective (Tanhan, 2019; Tanhan & Francisco, 2019).

The Muslims might be more likely to collaborate with such professionals once they view their cultural and religious perspectives as respected and accounted for their issues. Additionally, it is more likely that the Muslims will view mental health professionals incompetent if these professionals do not provide space for such cultural beliefs’ role in mental health issues, which generally leads the Muslims overuse of traditional services.

Knowledge of Formal Mental Health Services—Second Factor

Knowledge of mental health services entails the extent to which Muslims know about mental health issues, the role of formal mental health providers, interventions and treatment used, and the availability of formal mental health services in their community (Aloud & Rathur, 2009; Tanhan & Francisco, 2019). The majority of Muslims in the USA are immigrants; therefore, they often possess limited knowledge of mental health services in this country (e.g., Cook-Masaud & Wiggins, 2011; Tanhan, 2019; Tanhan & Francisco, 2019). Muslim immigrants are less likely to have formal mental health services available in their home countries and therefore lack information about the formal mental health services available in the US. In particular, knowledge of services available within their specific communities is often lacking (Tanhan & Francisco, 2019).

Researchers suggested that most Muslims will seek mental health services only in extreme cases, such as uncontrollable behavior, violence to others outside the family, or the presence of delusions or hallucinations (Aloud & Rathur, 2009; Tanhan & Francisco, 2019; Thomas et al., 2015). Generally, less disruptive mental health issues (e.g., depression, anxiety) are not acknowledged as illnesses, leading to a negative attitude toward seeking mental health services (Tanhan, 2017; Yıldırım, 2021). Understanding effective strategies to overcome the lack of knowledge about mental health services among many Muslims is crucial.

Within the extant literature, only a small number of researchers found that Muslims possessed knowledge of mental health services (Bagasra & Mackinem, 2014; Tanhan, 2017; Tanhan & Francisco, 2019; Tanhan & Strack, 2020). For example, in Tanhan and Francisco’s (2019) study, the college affiliated Muslims, in town hall meeting held to share the research results with the Muslim community, reported that they had not known about mental health services and therefore ranked such services as the least important. In the meeting, they also expressed their satisfaction with the authors for working with their community. Following the study, the participants witnessed how it was beneficial to work with mental health professionals and started to utilize the services more often and ask for more collaboration with the professionals to address issues at individual, group, and community levels among the Muslims. In another study, the college affiliated Muslims, who had collaborated with the mental health professionals for a qualitative study in which the researchers used Online Photovoice (OPV) methodology, reported mental health professionals as one of the most important strengths (Tanhan & Strack, 2020). The participants were not provided any information on or asked about mental health professionals or services in the research, as OPV is a qualitative study focusing on the participants lived experiences (Tanhan, 2020).

Based on all these, it is important that the professionals provide educational training on mental health issues and services from a biopsychosocial, spiritual, and economic perspective. The professionals need to collaborate with the Muslims for some mental health activities (e.g., experiential activities, research) beyond merely education to enhance wellbeing and address issues (Tanhan, 2019). Other researchers also stressed similar suggestions in different contexts (e.g., Tanhan et al., 2020a, 2020b; Yıldırım et al., 2021a, 2021b, 2021c).

Attitudes Toward Seeking Formal Mental Health Services—Third Factor

The attitudes that Muslims hold toward seeking formal mental health services is among the most widely studied concepts in this body of literature. Researchers reported that Muslims in the US and other Western cultures tend to hold negative attitudes toward seeking mental health services due to cultural beliefs, lack of knowledge, and perceived stigma (Alhomaizi et al., 2018; Tanhan & Francisco, 2019; Tummala-Narra & Claudius, 2013; Youssef & Deane, 2006). These researchers and some others (Agilkaya, 2012; Besiroglu et al., 2014; Tanhan, 2019; Tanhan & Strack, 2020) specifically stressed developing spiritually, culturally, and contextually sensitive mental health services and collaboration with Muslims (e.g., imams, spiritual leaders, community centers).

Tanhan and Francisco (2019) specifically highlighted collaborating with Muslim communities at different events and addressing mental health issues and services from contextually sensitive perspectives. Only a few researchers found that Muslims held positive attitudes toward mental health services (Khan, 2006; Tanhan & Strack, 2020; Thomas et al., 2015). The Muslims with negative attitudes toward seeking mental health services seem less likely to even think benefit from the services because they even do not consider them as a resource (Tanhan & Francisco, 2019; Tanhan & Strack, 2019), and they approach other resources. The mental health providers providing accurate and contextually sensitive biopsychosocial spiritual services, and economic information, experiential activities, and collaboration on mental health issues may contribute to construct more positive attitudes (Khan, 2006; Tanhan & Strack, 2020; Thomas et al., 2015).

Perceived Stigma Toward Seeking Mental Health Services—Fourth Factor

Perceived stigma is related to the perception of social disgrace (i.e., dishonor, disapproval, and disrespect from family, friends, community) when one seeks formal mental health services. It is a highly studied concept among Muslim populations. Ajzen (2006) defined perceived social stigma as the extent to which one perceives social pressure to engage or not to engage in a particular behavior. Fischer and Turner (1970) defined societal stigma as something, either visible or invisible, that causes a negative social effect on an individual.

Researchers have stressed that when Muslims misunderstand core Islamic beliefs related to the causes of human problems, this may lead to significant social stigma around pursuing mental health care (Abu-Ras, 2003; Herzig et al., 2013; Soheilian & Inman, 2009; Tanhan, 2019). Fewer researchers reported that perceived social stigma was not a significant barrier for the utilization of mental services particularly when more educated and important individuals within Muslim communities were included in sampling (Ali & Milstein, 2012; Kelly et al., 1996; Khan, 2006; Tanhan & Francisco, 2019; Tanhan & Strack, 2020).

The overall findings suggest that the more Muslims have societal stigma for seeking the services the more likely they improve negative attitudes toward the services and hide the person with mental issues from the societal contexts (e.g., Alhomaizi et al., 2018; Amri & Bemak, 2013; Phillips & Lauterbach, 2017; Tanhan, 2019; Tanhan & Francisco, 2019). These all lead to more isolation, less use of the formal mental health services, and more use of other traditional services that might lack a biomedical perspective, which may lead to fewer effective results if not harm at individual and community levels. The professionals may explain how Islam acknowledge each individual and their freedom to be united with the society, unless there is a legitimate reason. In Islam, there is an emphasis on recovery through the society rather than keeping people in institutions, prisons, or behind walls. Based on all these, the professionals can collaborate with key people to educate the Muslims about mental health issues and services from a biopsychosocial, spiritual, and economic holistic perspective.

Perceived Self-efficacy (Perceived Behavioral Control- PBC) toward Seeking Mental Health Services—Fifth Factor

Perceived self-efficacy speaks to one’s perception of her ability to seek mental health services to address mental health issues (Tanhan, 2017). Ajzen (1991) described Perceived Behavioral Control (PBC) as perception of one’s ability to perform a given behavior and/or the ease or difficulty of performing the behavior of interest. PBC is synonymous with Bandura’s concept of perceived self-efficacy. Multiple researchers have noted that Muslims often lack trust in and possess serious doubts about the use of mental health services and therefore would not utilize services even though they may be willing to (Amri & Bemak, 2013; Cook-Masaud & Wiggins, 2011; Tanhan, 2019; Tanhan & Francisco, 2019).

Researchers have called for mental health professionals as researchers and practitioners to examine PBC through the lens of TPB/TRA (Romano & Netland, 2008; Tanhan, 2017). Different from all reviewed studies including recent studies, PBC is an emerging concept that appears to bear direct influence on Muslims’ consumption of mental health services. If Muslims have knowledge and other resources to utilize mental health services, yet low level of PBC (meaning low perceived self-efficacy that means his or her ability to seek mental health services) toward the use of the services, they can be less likely to use the services. Low level of PBC can push Muslims away from the services due to the combined effect of other factors (e.g., stigma). Therefore, it may be worthwhile to address PBC directly with Muslims and make them more conscious of how human nature functions and inform them about self-efficacy. The practitioners can work on PBC through other constructs including social stigma and attitudes. The more accurate knowledge, positive attitudes, and less stigma the higher PBC toward the use of the services is expected.

Institutional Barriers—Sixth Factor

The availability of appropriate services, mental health professionals like counselors who strive to improve their competency, and the active facilitation of Muslims engaging in mental health services (versus creating barriers) encompass the factor of institutional barriers (Cook-Masaud & Wiggins, 2011; Tanhan, 2019; Tanhan & Francisco, 2019). The lack of appropriate services may reinforce negative attitudes toward, misinformation about, and higher stigma toward mental health services. Insufficient services may also lead to low PBC. Researchers argued that mental health providers needed to be more active and community-engaged to connect with Muslim communities and engage these individuals in services.

Tanhan and Strack (2020) noted that Muslim students who knew little about mental health services on campuses started to utilize and collaborate with mental health institutions and overall other resources on campus, following the research conducted with and for the Muslim communities. This approach resulted in enhancing environmental factors (e.g., making mental health centers and campuses more inclusive for Muslims) that facilitated Muslims addressing mental health issues (e.g., Tanhan & Francisco, 2019; Tanhan & Strack, 2020). For example, if professionals pay attention to make counseling services and institutions sensitive to Muslims (e.g., providing prayer places, appropriate restrooms that have water to use for cleaning, and most importantly professionals who have an average knowledge about Islam and strive to enhance their competency to provide a more holistic biopsychosocial spiritual service), then it is more likely that the Muslims will be more willing to collaborate with the professionals (Tanhan & Francisco, 2019; Tanhan & Strack, 2020). Such a sensitive approach on the professionals’ side will also facilitate the Muslims construct more accurate knowledge about, positive attitudes and intention toward, less stigma, and a higher level of PBC for using the services. It is important the professionals, and especially Muslim professionals, give attention to tailor main counseling approaches to be used with the Muslims and improve available theoretical frameworks and modals or develop new ones that explains human psychology from an Islamic perspective (Abu-Raiya, 2015; Agilkaya-Şahin, 2019; Hamjah & Akhir, 2014; Kaplick et al., 2019; Keshavarzi & Haque, 2013; Rothman & Coyle, 2018; Tanhan, 2019; Tanhan & Francisco, 2019).

Use of Traditional Resources—Seventh Factor

Researchers suggested that Muslims may over rely on traditional resources (e.g., religious and spiritual resources like recitation of Quran, visiting sheikh, consulting imam, praying; social resources like family, friends; diet), which may contribute to negative attitudes toward and underutilization of mental health services (Bektas et al., 2009; Chen et al., 2015; Tanhan & Francisco, 2019; Youssef & Deane, 2006) if mental health professionals do not develop effective collaboration (Tanhan, 2019; Tanhan & Francisco, 2019). Muslims at times have denied the role of mental health services and understood religious resources in inflexible ways thereby creating rigidity in their thinking and potentially aggravating their mental health challenges (Tanhan, 2019; Tanhan & Francisco, 2019).

In general, these traditional resources include more religious, spiritual, and social aspects and may not include collaboration with formal mental health services and may lack biological, psychological, and medical aspects of modern services. Therefore, these traditional resources may lack a holistic approach and be insufficient that gradually become part of the issue leading to rigidity and psychopathology. Both the formal professionals and traditional healers can collaborate to construct more holistic biopsychosocial spiritual approaches; otherwise, it may be difficult to address psychopathology and enhance wellbeing with just one approach (Tanhan, 2019; Tanhan & Francisco, 2019). The Muslims will be more likely to approach consuming the formal mental health services if the formal professionals acknowledge and include the traditional resources (Tanhan & Strack, 2020). Overall, the researchers stressed such holistic approaches and empirical research are needed (e.g., Agilkaya-Şahin, 2019; Alhomaizi et al., 2018; Al'Uqdah et al., 2019; Besiri et al., 2014).

Acculturation—Eighth Factor

Acculturation is the process by which individuals or groups engage with another cultural system and experience changes to aspects of their own culture (Bektas et al., 2009; Matsumoto & Juang, 2008). Marginalization, separation, and isolation acculturation strategies can lead to a lack of awareness of mental health services and over reliance on informal resources. An integrated acculturation strategy, by contrast, may lead to greater awareness of available services (Aprahamian et al., 2011; Bektas et al., 2009; Goforth et al., 2014; Tanhan & Francisco, 2019). Muslims with a more integrated acculturation process are more likely to utilize mental health services. Therefore, researchers have highlighted the need for professionals to enhance their cultural competency to facilitate Muslims developing a more integrated acculturation (Al'Uqdah et al., 2019; Amri & Bemak, 2013; Tanhan & Francisco, 2019; Tanhan & Strack, 2020; Tummala-Narra & Claudius, 2013).

Control Variables—Ninth Factor

Researchers have reported contradictory findings in relations to control variables (e.g., education, sex, past behavior, race/ethnicity, economic factors, length of stay in Western countries, age) and their relationships with other factors that influence the consumption of mental health services. Some researchers have found that higher levels of education lead to more favorable engagement with mental health services (Ali & Milstein, 2012; Bagasra & Mackinem, 2014; Tanhan & Francisco, 2019; Tanhan & Strack, 2020). In terms of sex, most studies reported that women had more favorable attitudes toward mental health services and, sadly, greater difficulty utilizing services (Cook-Masaud & Wiggins, 2011; Khan, 2006; Youssef & Deane, 2006).

Race/ethnicity has produced contradictory findings. Generally, Arabs, Middle Eastern Americans, and African American Muslims have the least favorable attitudes toward mental health care, while European American Muslims and South Asian Muslims possess more favorable attitudes. Past behaviors as predictors of engagement with mental health services have been researched sparsely. Some researchers found that the Muslims who have utilized mental health services in the past are more likely to do so again and hold more positive attitudes toward the services (Bagasra & Mackinem, 2014; Tanhan & Strack, 2020).

Economic factors are an area of meager research yet in two cases; more wealthy Muslims did not want to risk the family name; therefore, they sought to avoid mental health services to hide mental illness. Among lower income Muslims, concerns over the affordability of services were a concern (Aloud & Rathur, 2009; Tanhan, 2019). Although there are contradictory findings of how control variables affect Muslims’ approach to the mental health services, additional research is needed.

Intention Toward Seeking Formal Mental Health Services—Tenth Factor

The readiness or motivation to perform a behavior of interest encapsulates the factor of intention (Ajzen, 1991, 2006). Few researchers (Kelly et al., 1996; Tanhan, 2017, 2019) mentioned Muslims’ intention toward use of mental health services. It is important to further investigate the intention given that it is an important concept within Islam, considered more important than the behavior itself in some special cases (Tanhan, 2019).

Tanhan (2019) explained how Islam formulates one’s intention in four ways related to its action. First, a person pleases Allah (God) and gets rewarded when he or she has a meaningful intention (e.g., intending to be beneficial to self, others, and universe) and strives to act accordingly. Second, the person again pleases God and gets rewarded when he or she has a meaningful intention and yet cannot act on it. Third, the person pleases God and gets rewarded when he or she has a harmful or meaningless intention and yet strives not to act on it and does not act on it though they are capable to act on it. Finally, the person is held accountable and displeases God when the person has harmful or meaningless intention and acts on it and/or strives to act on yet cannot make it happen as it intended due to other reasons. In this last case, the person is held accountable for their harmful intention regardless of whether the result leads to something meaningful, neutral, or negative because the intention and action following the intention was meaningless or harmful. If nothing harmful (e.g., physically, or psychologically harming others or the universe) follows the harmful intention, the person is held accountable only for their meaningless or harmful intention. Tanhan (2019) shed light on how mental health professionals can pay attention to develop comprehensive, contextual and empirical counseling approaches benefitting from SEM and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) while giving attention to clients’ intention.

The researchers (Kelly et al., 1996; Khan, 2006) found that some Muslims used the services and had an intent to seek mental health services when needed. However, they did not measure intention through a well-established instrument. Intention has a central role in TPB/TRA to understand behavioral choices because intention precedes the behavior construct. In TPB/TRA, intention is a mediator, which means it is one of the most important constructs that explains the behavior. Intention is important because in most of the studies from TPB/TRA perspective, PBC and intention together, most of the times, explained the most variance in the behavior (Ajzen et al., 2011; Fishbein & Ajzen, 2010). We did not come across anything regarding the role of intention in SEM; however, it is an important fact that intention is one of the crucial concepts in Islam. Subsequently, we included intention as a factor in the concept map.