Abstract

Background:

According to the stress inoculation hypothesis, successfully navigating life stressors may improve one’s ability to cope with subsequent stressors, thereby increasing psychiatric resilience.

Aims:

Among individuals with no baseline history of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and/or major depressive disorder (MDD), to determine whether a history of stressful life event protected participants against developing of PTSD and/or MDD after a natural disaster.

Method:

Analyses utilized data from a multi-wave, prospective cohort study of adult Chilean primary care attendees (years 2003–2011; N=1,160). At baseline, participants completed the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI), a comprehensive psychiatric diagnostic instrument, and the List of Threatening Experiences, a 12-item questionnaire that measures major stressful life events. Amid the study (2010), the 6th most powerful earthquake on record struck Chile. One year later (2011), the CIDI was re-administered to assess post-disaster PTSD and/or MDD.

Results:

Marginal structural logistic regressions indicated that for every one-unit increase in the number of pre-disaster stressors, the odds of developing post-disaster PTSD or MDD increased (OR=1.21; 95% CI=1.08–1.37; OR=1.16; 95% CI=1.06–1.27, respectively). When categorizing pre-disaster stressors, individuals with 4+ stressors (vs. 0) had higher odds of developing post-disaster PTSD (OR=2.77; 95% CI=1.52–5.04), while a dose-response relationship between pre-disaster stressors and post-disaster MDD was found.

Conclusions:

In contrast to the Inoculation Hypothesis, results indicated that experiencing multiple stressors increased the vulnerability to developing PTSD and/or MDD after a natural disaster. Increased knowledge regarding the individual variations of these disorders is essential to informing targeted mental health interventions after a natural disaster.

Introduction

Many find inspiration and meaning in Nietzsche’s famous words, “What does not destroy me, makes me stronger.” The theory behind these words is the inoculation hypothesis, which attempts to predict an individual’s reaction to a stressful event based on his/her past experiences (1). Specifically, this hypothesis posits that experiencing manageable stressors may improve an individual’s ability to cope with future stressors by providing a context in which to practice effective coping skills and build a sense of mastery over stressors (2), which in turn could enhance resilience—broadly defined as positive psychological adaptation to adversity (3)—and reduce later vulnerability to poor mental health outcomes (1, 4). However, whether this holds true when individuals are later exposed to traumatic stressors, specifically for some of the most common and debilitating stress-related clinical conditions like major depressive disorder (MDD) or posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), remains open to debate (5, 6).

Traumatic stressors are different from manageable stressors in that manageable stressors are typically less severe, allowing most individuals to engage in coping efforts without exceeding their capacity to manage such stressors. For example, someone who has lost his job may find certain strategies (e.g., problem solving, physical exercise, and social support) are helpful in managing the stress of unemployment; in turn, this experience could provide a template for coping effectively with later stressors. For example, if the later stressor were another episode of unemployment, this would be an example of direct tolerance—a type of inoculation where the prior stressor is the same as the later exposure (3). Conversely, if the later stressor were a divorce, this would be an example of cross tolerance—a type of inoculation where the prior stressor is different from the later exposure. As illustrated in these examples, both prior and later exposures are manageable stressors. According to the inoculation hypothesis, this would increase the likelihood of successful initial coping and subsequent inoculation against stress-related disorders, such as MDD and/or PTSD.

Compared to manageable stressors, traumatic stressors (e.g., rape, combat) are more extreme in nature and can overwhelm an individual’s ability to cope effectively by inducing emotional distress that exceeds what one can independently manage and/or exhausts the capacity of the stress response system (7). Literature suggests that prior stressors, particularly those that are traumatic and unmanageable, can increase risk for later psychiatric disorders such as PTSD and/or MDD (8). For example, individuals with maladaptive cognitive vulnerabilities (e.g., negative attentional bias) developed in response to earlier stressors may more readily develop future psychiatric disorders (9)—as consistent with a stress sensitization model. This model is similar to the concepts of ‘kindling’ and/or ‘weathering,’ in which earlier vulnerability to psychopathology triggered by initial stressful experiences is posited to decrease the threshold of stress exposure required for developing subsequent psychopathology (10). However, previous work has also shown that prior trauma exposure alone does not predict later PTSD, except among those who developed PTSD after the prior exposure (11, 12). If someone has experienced a prior stressor, but did not develop a psychiatric disorder such as PTSD and/or MDD, this suggests he/she successfully managed this stressor from a psychological perspective (e.g., seeking support, establishing daily routines, finding meaning) and may thus be prepared to cope successfully for future traumatic exposures—as consistent with the inoculation hypothesis. However, these hypotheses require further investigation in trauma-exposed populations.

The main objective of the current study was to test the inoculation hypothesis in an understudied Chilean population. During this multi-wave cohort study, one of the most powerful earthquakes on record, measuring 8.8 on the Richter Scale, struck the coast of central Chile (February 27, 2010). This disaster resulted in over 500 deaths, 12,000 injured, 800,000 displaced, and hundreds of thousands of buildings damaged or destroyed (13). The cities of Concepciόn and Talcahuano, where this cohort was based, were major urban areas that experienced most damage from the earthquake and its subsequent effects, including a tsunami that hit Talcahuano (13). Chile is particularly vulnerable to earthquakes and tsunamis due to the country’s geographic location on an arc of volcanos and fault lines circling the Pacific Ocean, otherwise known as the “Ring of Fire.” Individuals in these high-risk locations are often exposed to recurrent disasters and thus likely at higher risk for developing post-disaster psychological issues such as PTSD and/or MDD (14).

We sought to assess, among individuals with no pre-disaster psychiatric history of MDD or PTSD, whether a history of prior stressors was associated with psychiatric resilience, as evidenced by the absence of negative outcomes where otherwise expected—specifically, whether it protected against the post-disaster development of PTSD and/or MDD, two of the most common psychiatric reactions following disasters (14). The three hypotheses are: 1) prior experience of a natural disaster will protect against developing post-disaster PTSD and/or MDD (i.e., direct tolerance); 2) prior experience of manageable stressors will protect against developing post-disaster PTSD and/or MDD (i.e., cross tolerance); and 3) there will be a dose-response negative relationship between the number of prior stressors and increased odds of post-disaster PTSD and/or MDD. This study will provide an unprecedented opportunity to answer these questions in an international setting, providing culturally- and context-specific information about the risk the factors associated with developing psychopathology after a disaster.

Methods

Participants

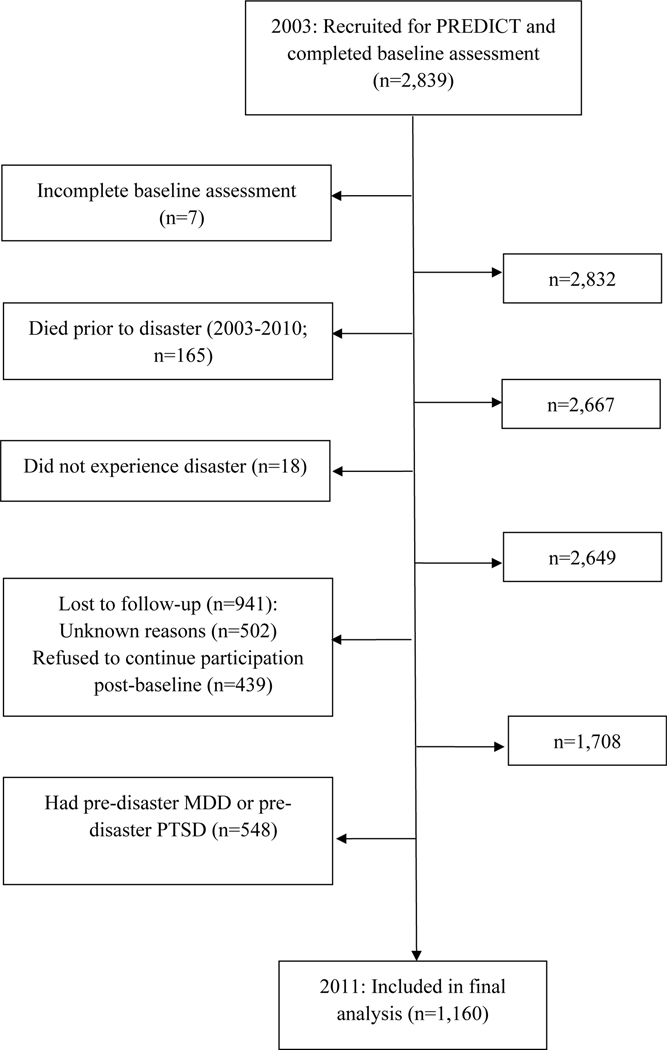

The current analysis utilizes two waves of data from the Chilean site of the PREDICT study (N=1,160), a cross-national prospective cohort study with the primary aim of predicting mental health outcomes in primary care attendees (15–17). Participants were recruited from 10 primary care centers within the national health care service (used by approximately 75% of the population) in the cities of Concepciόn and Talcahuano, Chile (15). Of the 3,000 participants who initially agreed to participate, 2,839 completed the baseline pre-disaster assessment in 2003 and 1,708 participants completed the post-disaster assessment in 2011, one year after the disaster occurred (18). Because the inoculation hypothesis assumes that individuals have successfully coped with prior stressors (i.e., not developing PTSD and/or MDD), those with a pre-disaster MDD and/or PTSD diagnosis (according to the baseline CIDI) were excluded. The exclusion and inclusion criterion used to obtain the analytic sample are displayed in Figure 1 (N=1,160).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of excluded/ineligible individuals: The PREDICT study (2003–2011)

Ethics Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. All procedures involving human subjects/patients were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Concepciόn. The current study utilizes secondary analysis using de-identified data; therefore, IRB approval was not necessary.

Measurements

Dependent Variables: Post-Disaster MDD and Post-Disaster PTSD (as measured in 2011)

The Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI), Spanish version 2.1 (19) was used to assess pre- and post-disaster MDD and PTSD. The CIDI is a fully structured psychiatric diagnostic instrument that assesses psychiatric disorders via computerized algorithms according to DSM–IV-TR criteria (20). The CIDI has good psychometric properties, with excellent inter-rater reliability, good test-rest reliability, good validity (21), and is used widely in countries throughout the world (22). The CIDI is administered by lay interviewers and does not utilize outside informants or medical records (19). It also uses skip patterns to efficiently diagnose the presence/absence of a disorder, though yields limited systematic symptom-level information and may reduce power by excluding individuals with sub-clinical diagnoses. The translated version of the CIDI is an official World Health Organization Spanish version (23, 24), and has been validated in prior national studies conducted in Chile. A prior validation study found that each CIDI section showed moderate to excellent kappa estimates (25).

The Depressive Disorders module (Section E) of the CIDI was used to diagnose post-disaster MDD in the past 12 months (i.e., since the 2010 disaster occurred). These questions follow the DSM-IV symptom criteria. A full description of this module can be found in Appendix 2 (online supplement). In addition to the post-disaster MDD assessment, a modified version of the PTSD module of the CIDI (Section F) Spanish version 2.1 (19) was used to assess post-disaster PTSD. This module asks about all 21 PTSD symptoms from the DSM–IV–TR (26). It is important to note the details of the “post-disaster PTSD module” customizations. There are two major differences in the original PTSD module of the CIDI compared to the modified version. First, unlike the original PTSD module, the modified version did not begin the interview with a complete enumeration of potentially traumatic events as operationalized by the DSM-IV-R. Instead, participants were only asked whether they had or had not experienced the 2010 natural disaster (i.e., Criterion A.1). If the participant did not endorse being in the 2010 disaster, they were screened out of the assessment. No other history of other potentially traumatic events were assessed to ensure that the assessment was measuring PTSD from the 2010 disaster only (i.e., only individuals with disaster-related PTSD were captured) (18).

The second major difference in the modified PTSD module is that all the PTSD symptoms were anchored to assess PTSD symptoms due to the disaster only. This required minor modifications of all the questions. For example, a question used to measure avoidance symptoms reads: “Were you trying to force yourself to not think or talk about the earthquake/tsunami?” A question used to measure a symptom of re-experiencing is: “After the earthquake/tsunami, did you have nightmares?” Note that all the assessment questions referenced the 2010 disaster when asking about PTSD symptoms (18).

Independent Variables: Pre-Disaster Stressors (as measured in 2003)

List of Threatening Experiences

The List of Threatening Experiences (LTE) is 12-item dichotomous response questionnaire used to measure major categories of stressful life events (from the prior 6 months) involving moderate or long-term threat (27). Stressful events include: serious illness, injury, or assault of self or close relative; death of parent, child, spouse/partner, close family friend, or another relative (aunt, cousin, grandparent); marital or relationship separation; serious problem with a close friend, neighbor, or relative; unemployment; recent job termination; major financial crisis; problems with the police (including a court appearance); and something of value was lost or stolen (27). At the baseline assessment, participants indicated whether each of the 12 different stressful life events occurred in the prior 6 months. The total score is the sum of the individual items (maximum score=12) (28). The LTE has been shown to have good psychometric properties, with excellent test-rest reliability, good inter-rater reliability, and high concurrent validity (27). To examine dose-response relationships between the number of pre-disaster stressors and risk of post-disaster PTSD and/or MDD, the total score was categorized (0, 1, 2, 3, 4+ stressors) based on the distribution of the sample. Stressors captured by the LTE were conceptualized as “cross tolerance” for the current study.

Prior Disaster Experience

In the CIDI baseline assessment, participants indicated whether they had previously experienced a natural disaster (i.e., any natural disaster prior to the 2010 earthquake/tsunami) as part of the potentially traumatic events portion of the PTSD module of the CIDI. The disaster stressor captured was conceptualized as “direct tolerance” for the current study.

Confounding Variables

Confounding variables were selected based on prior literature regarding known risk factors for pre-disaster stressors and post-disaster PTSD and MDD (29–31). These include: age, gender, and educational attainment. Age was collapsed into “middle aged” or “not middle aged” (i.e., 45–55 years vs. other), because subsequent post hoc analyses only showed significant differences between these two age groups. Education was also collapsed into “illiterate/elementary school” versus “high school/college” for the same reason (18).

Statistical analyses

Loss to Follow-up

As described in our previous work with this data (18), there is potential for selection bias due to differential loss to follow-up in this longitudinal study design. To examine this possibility, χ2 and multivariable logistic regression analyses were conducted to examine the characteristics of those who were lost to follow-up (n=941 [33.1% of the original sample]; see Figure 1). Those included in the “lost to follow-up” category included individuals who refused subsequent assessments post-baseline, died, or were lost to follow-up for unknown reasons. Among the 941 individuals who dropped out, there were significantly more females than males (69% vs. 30%; χ2=14.84 p<0.001), more participants with a high school/college education compared to those who were illiterate or had an elementary school education (73.4% vs. 26.6%; χ2=11.89, p=0.001), and more individuals who were not middle age relative to those who were middle age (83.5% vs. 16.5%; χ2=4.71, p=0.03). Multivariable logistic regression models predicting loss to follow-up replicated these findings (results not shown) (18). Additional sensitivity analyses examining the differences in the rate of other pre-disaster disorders among those who were and were not lost to follow-up are displayed in Appendix 1 (online supplement).

Inverse Probability Weighting

To mitigate the potential selection bias due to differential loss to follow-up, inverse probability censoring weights were calculated. To estimate the censoring weights, the predicted probability of not dropping out based on each participant’s exposure (i.e., pre-disaster stressors) and confounder values (i.e., gender, age, and education) were estimated using a multivariable logistic regression model. Weights were calculated for each participant as the inverse of this probability. Thus, the weights can be described as the number of participants who are like individual i (in terms of their exposure and confounder values) that would have been in the risk set at the post-disaster assessment in the absence of dropout. In sum, the inverse probability censoring weights create a pseudo-population had dropout been random (with respect to exposure and confounder values). Weights were stabilized to preserve amount of information in the observed data and minimize variability (18, 32).

To mitigate potential confounding bias, inverse probability exposure weights were calculated. To estimate the exposure weights, the probability of each individual’s exposure (i.e., pre-disaster stressors) given their confounder values (i.e., gender, age, and education) was modeled. The final weights can be described as a pseudo-population where each participant’s exposure is independent of his/her measured confounders (33). Weights were stabilized to preserve the amount of information in the observed data and minimize variability (18, 32).

List of Threatening Experiences – Questions about Assault

It is worth noting that two of the LTE questions ask about assault to self (n=204; 17.6%) or assault to others (n=254; 21.9%). According to the DSM-IV-TR criteria, these experiences are considered potentially traumatic events and should not be considered as “manageable stressors.” Therefore, all analyses were conducted two ways: one set of analyses with all 12 of the items of the LTE (i.e., those presented in final tables), and another set of analyses with the two items about assault excluded. Results from both sets of analyses were not statistically different from each other. (i.e., the confidence intervals overlapped, and the point estimates marginally changed). The similarity of results is likely due to the analytic sample used to operationalize “manageable stressors.” Further, given the LTE has been validated as is (the full 12-item questionnaire), the questions regarding assault were kept for all analyses and we will continue to use the term “manageable stressors” for continuity purposes and to accurately reflect the wording of the Inoculation Hypotheses.

Post-hoc Sensitivity Analyses

It is important to note that post-hoc sensitivity analyses excluding individuals with other pre-disaster disorders besides PTSD and MDD (e.g., alcohol abuse, anxiety disorders, dysthymia, non-affective psychotic disorders) did not substantially change the findings. Further, there was no significant interactions (neither additive or multiplicate) between prior disaster experience (before the 2010 earthquake/tsunami) and stressors. Although our results are robust and the effect estimates did not vary substantially, these findings are available upon request (34, 35).

Analysis Plan

As mentioned above, because the inoculation hypothesis assumes that individuals effectively manage their stressors to cope with subsequent adversity, those with a pre-disaster MDD or pre-disaster PTSD (according to the CIDI at the baseline assessment) were excluded. The study hypotheses utilized a series of marginal structural logistic models, with exposure and confounding inverse probability weights. To test direct tolerance, we examined whether one’s history of being in a disaster (prior to the 2010 disaster) protected against developing post-disaster PTSD and MDD. To test cross-tolerance, we examined whether one’s history of non-disaster stressors (i.e., total LTE score) protected against developing post-disaster PTSD and MDD. STATA/MP version 12 was used for data management and statistical analyses (36).

Results

Descriptive Information

Among individuals with post-disaster PTSD (n=106; Table 1) and post-disaster MDD (n=167; Table 2), most of the sample was female, not middle age, had a high school/college education, and had not experienced a disaster prior to the 2010 earthquake/tsunami. The distribution of the LTE scores in all subsamples was positively skewed.

Table 1.

Pre-disaster demographic and stressor information of analytic sample with and without post-disaster PTSD: The PREDICT study, 2003–2011 (N=1,160)

| Total sample (N=1,160; 100%) | n (%) with post-disaster PTSD (n=106; 9.1%) | n (%) without post-disaster PTSD (n=1,054; 90.9%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 348 | 19 (5.5) | 329 (94.5) |

| Female | 812 | 87 (10.7) | 725 (89.3) |

| Age | |||

| 45–54 | 205 | 29 (14.2) | 176 (85.9) |

| <45 and 55+ | 955 | 77 (8.1) | 878 (91.9) |

| Education | |||

| High School/College | 783 | 62 (7.9) | 721 (92.1) |

| Illiterate/Elementary School | 375 | 44 (11.7) | 331 (88.3) |

| Missing | 2 | 0 | 2 (100) |

| Post-disaster Depression | |||

| Yes | 167 | 38 (22.8) | 129 (77.3) |

| No | 993 | 68 (6.9) | 925 (93.2) |

| Pre-disaster Stressors | |||

| Continuous LTE Total Score* | |||

| 0 | 420 | 32 (7.6) | 388 (92.4) |

| 1 | 330 | 27 (8.2) | 303 (91.8) |

| 2 | 174 | 17 (9.8) | 157 (90.2) |

| 3 | 125 | 9 (7.2) | 116 (92.8) |

| 4 | 55 | 10 (18.2) | 45 (81.8) |

| 5 | 28 | 3 (10.7) | 25 (89.3) |

| 6 | 17 | 3 (17.7) | 14 (82.4) |

| 7 | 7 | 3 (42.9) | 4 (57.1) |

| 8 | 2 | 1 (50.0) | 1 (50.0) |

| 9 | 1 | 0 | 1 (100.0) |

| 10 | 1 | 1 (100.0) | 0 |

| Categorized LTE Total Score | |||

| 0 | 420 | 32 (7.6) | 388 (92.4) |

| 1 | 330 | 27 (8.2) | 303 (91.8) |

| 2 | 174 | 17 (9.8) | 157 (90.2) |

| 3 | 125 | 9 (7.2) | 116 (92.8) |

| 4+ | 111 | 21 (18.9) | 90 (81.1) |

| Disaster** | |||

| Yes | 230 | 22 (9.6) | 208 (90.4) |

| No | 926 | 84 (9.1) | 842 (90.9) |

| Missing | 4 | 0 | 4 (100.0) |

PTSD=Posttraumatic Stress Disorder; MDD=Major Depressive Disorder; LTE=List of Threatening Experiences

Among those with post-disaster PTSD, the mean LTE score=1.9 (Standard Deviation=2.1)

Refers to whether participant had experienced a disaster prior to the 2010 earthquake/tsunami

Table 2.

Pre-disaster demographic and stressor information of sample with and without post-disaster MDD: The PREDICT study, 2003–2011 (N=1,160)

| Total sample (N=1,160; 100%) | n (%) with post-disaster MDD (n=167; 14.4%) | n (%) without post-disaster MDD (n=993; 85.6%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 348 | 25 (7.2) | 323 (92.8) |

| Female | 812 | 142 (17.5) | 670 (82.5) |

| Age | |||

| 45–54 | 205 | 40 (19.5) | 165 (80.5) |

| <45 and 55+ | 955 | 127 (13.3) | 828 (86.7) |

| Education | |||

| High School/College | 783 | 115 (14.7) | 668 (85.3) |

| Illiterate/Elementary School | 375 | 52 (13.9) | 323 (86.1) |

| Missing | 2 | 0 | 2 (100) |

| Post-disaster PTSD | |||

| Yes | 106 | 38 (35.9) | 68 (64.2) |

| No | 1,054 | 129 (12.2) | 925 (87.8) |

| Pre-Disaster Stressors | |||

| Continuous LTE Total Score* | |||

| 0 | 420 | 39 (9.3) | 381 (90.7) |

| 1 | 330 | 53 (16.1) | 277 (83.9) |

| 2 | 174 | 32 (18.4) | 142 (81.6) |

| 3 | 125 | 22 (17.6) | 103 (82.4) |

| 4 | 55 | 8 (14.6) | 47 (85.5) |

| 5 | 28 | 8 (28.6) | 20 (71.4) |

| 6 | 17 | 3 (17.7) | 14 (82.4) |

| 7 | 7 | 2 (28.6) | 5 (71.4) |

| 8 | 2 | 0 | 2 (100) |

| 9 | 1 | 0 | 1 (100) |

| 10 | 1 | 0 | 1 (100) |

| Categorized LTE Total Score | |||

| 0 | 420 | 39 (9.3) | 381 (90.7) |

| 1 | 330 | 53 (16.1) | 277 (83.9) |

| 2 | 174 | 32 (18.4) | 142 (81.6) |

| 3 | 125 | 22 (17.6) | 103 (82.4) |

| 4+ | 111 | 21 (18.9) | 90 (81.1) |

| Disaster** | |||

| Yes | 230 | 29 (12.6) | 201 (87.4) |

| No | 926 | 138 (14.9) | 788 (85.1) |

| Missing | 4 | 0 | 4 (100) |

MDD=Major Depressive Disorder; PTSD=Posttraumatic Stress Disorder; LTE=List of Threatening Experiences

Among those with post-disaster MDD, the mean LTE score=1.7 (Standard Deviation=1.6)

Refers to whether participant had experienced a disaster prior to the 2010 earthquake/tsunami

Marginal Structural Logistic Regression Models – PTSD

As shown in Table 3, Model 1 tested the risk of PTSD associated with direct tolerance (i.e., prior disaster experience). Models 2 and 3 tested the risk of PTSD associated with prior non-disaster stressor experience (i.e., cross tolerance). Prior disaster exposure was not a significant predictor of post-disaster PTSD. On the other hand, for every one-unit increase in prior non-disaster stressors, the odds of developing post-disaster PTSD increased (OR=1.21; 95% CI=1.08–1.37; p=0.001; Model 2). When these stressors were categorized, those who experienced 4 or more stressors (vs. 0 stressors), had an increased risk of developing post-disaster PTSD (OR=2.77; 95% CI=1.52–5.04; p=0.001; Model 3).

Table 3.

Marginal structural logistic regression analyses of pre-disaster stressors predicting post-disaster PTSD: The PREDICT study, 2003–2011 (N=1,154)

| Independent Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p | OR | 95% CI | p | OR | 95% CI | p | |

| Disaster* | 1.06 | 0.65–1.74 | 0.815 | ||||||

| LTE sum: linear | 1.21 | 1.08–1.37 | 0.001 | ||||||

| LTE sum: categorized 0 |

Ref | ||||||||

| 1 | 1.07 | 0.63–1.83 | 0.798 | ||||||

| 2 | 1.29 | 0.69–2.39 | 0.422 | ||||||

| 3 | 0.93 | 0.43–2.01 | 0.856 | ||||||

| 4+ | 2.77 | 1.52–5.04 | 0.001 | ||||||

OR=odds ratio; 95% CI=95% confidence interval; LTE=List of Threatening Experiences summary score

Refers to whether participant had experienced a disaster prior to the 2010 earthquake/tsunami

Note: All models utilize stabilized inverse probability censoring and exposure weights (by gender, age, and education) and robust standard error estimate

Marginal Structural Logistic Regression Models – MDD

As displayed in Table 4, Model 1 tested the risk of MDD associated with prior disaster experience. Models 2 and 3 tested the risk of MDD associated with prior non-disaster stressor experience. Prior disaster exposure was not a significant predictor of post-disaster MDD (Model 1). For every one-unit increase in prior non-disaster stressors, the odds of developing post-disaster MDD increased OR=1.16; 95% CI=1.06–1.27; p=0.001; Model 2). When stressors were categorized, experiencing any number of stressors (relative to 0 stressors) significantly increased the odds of developing post-disaster MDD in a dose-response fashion (Model 3).

Table 4.

Marginal structural logistic regression analyses of pre-disaster stressors predicting post-disaster MDD: The PREDICT study, 2003–2011 (N=1,154)

| Independent Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p | OR | 95% CI | p | OR | 95% CI | p | |

| Disaster* | 0.82 | 0.53–1.26 | 0.358 | ||||||

| LTE sum: linear | 1.16 | 1.06–1.27 | 0.001 | ||||||

| LTE sum: categorized 0 |

Ref | ||||||||

| 1 | 1.86 | 1.20–2.89 | 0.006 | ||||||

| 2 | 2.19 | 1.31–3.62 | 0.003 | ||||||

| 3 | 2.09 | 1.19–3.69 | 0.011 | ||||||

| 4+ | 2.27 | 1.27–4.04 | 0.006 | ||||||

OR=odds ratio; 95% CI=95% confidence interval; LTE=List of Threatening Experiences summary score

Refers to whether participant had experienced a disaster prior to the 2010 earthquake/tsunami

Note: All models utilize stabilized inverse probability censoring and exposure weights (by gender, age, and education) and robust standard error estimates

Discussion

The current study tested the applicability of the inoculation hypothesis on psychiatric vulnerability in an understudied international population who had experienced a natural disaster. To do so, we assessed whether a history of stressful life events, among Chilean adults with no lifetime history of PTSD and/or MDD, decreased the odds that a subsequent traumatic experience (i.e., exposure to an earthquake) would trigger MDD and/or PTSD. Cumulatively, the findings did not support direct or indirect inoculation. In fact, the results were in the opposite hypothesized direction, and are therefore reflective of the stress sensitization model, which states that experiencing multiple stressors increase the probability of developing a psychiatric disorder (as opposed to more resilient as implied in the inoculation hypothesis).

Because a history of pre-disaster stressors increased the risk of developing post-disaster PTSD and/or MDD, it is likely that this Chilean sample experienced “stress sensitization.” Stress sensitization posits that a stressor will make an individual more vulnerable to the negative effects of subsequent stressors, rather than developing resilience (37–39). Therefore, an individual who has experienced several stressors in their lifetime will be at higher risk for developing a psychiatric disorder (38). This theory is supported by substantial literature (11, 12), and has also been used to explain individual differences in the development, recurrence, and maintenance of psychiatric disorders, such as PTSD and/or MDD (40, 41).

Unfortunately, the majority of research on PTSD has investigated risk associated with prior traumatic stressors, not manageable stressors (29). This is especially true among populations outside of the United States. In the current study, results indicated that for every one unit increase in pre-disaster stressors, the risk of developing post-disaster PTSD increased by 21%. However, when stressors were categorized, only participants who experienced 4 or more stressors (i.e., the highest category), relative to 0 stressors, had a higher risk of developing post-disaster PTSD. The suggests that the amount of prior manageable stressors needs to cross a severity threshold (4+ stressors) to impact future vulnerability to PTSD (42).

In contrast to the PTSD literature, it is well known that “non-traumatic” psychosocial stressors play an essential role in the etiology of MDD (9, 10). Other literature in high-trauma international settings has suggested that manageable stressors can actually have a stronger impact than traumatic stressors on mental health outcomes (43, 44). These adversities may leave residual vulnerabilities on the individual, thus increasing the probability of developing MDD due to sensitization (10). Furthermore, cumulative adversity tends to be more harmful than a single episode through the depletion of coping resources over time (39, 45). This conceptualization reflects the results of the current study, which indicated a dose-response relationship between the number of pre-disaster stressors and the risk of post-disaster MDD. These stressful events may be associated with depression (40) through behavioral (e.g., poor coping mechanisms), cognitive (e.g., negative attention biases, rumination (9, 46), and/or biological mechanisms (e.g., physiological stress response dysregulation (39, 41, 47). Although these pathways were not included in the present study, they merit additional investigation in future longitudinal studies.

Strengths and Limitations

The present study has some limitations worth noting. First, there is potential for measurement error of the exposure variables (i.e., pre-disaster stressors and pre-disaster PTSD and MDD). The preliminary concern is that the baseline examination was administered 7 years before the disaster (2003). New stressors that occurred between the baseline assessment and the earthquake (i.e., between the years of 2003–2010). may have been missed. It is also possible that individuals developed pre-disaster PTSD and/or pre-disaster MDD during this 7-year period. Given our analytic sample excluded individuals with any history of pre-disaster PTSD and/or MDD, those who had PTSD and/or MDD would be categorized as false negatives, leading to biased results.

Similarly, there is potential for misclassification of the outcome variable (post-disaster PTSD). Given the post-disaster PTSD assessment was administered approximately a year after the disaster occurred (2011), there are some individuals who may have had disaster-related PTSD, but their symptoms resolved before the assessment occurred. Conversely, individuals may have developed delayed-onset PTSD years after the disaster; these individuals would not have been captured as having disaster-related PTSD in our assessment. Fortunately, misclassification of post-disaster MDD is less likely given the CIDI only assessed post-disaster MDD from the prior year (i.e., between the disaster occurrence and assessment). Another limitation is that the CIDI automatically generates dichotomized diagnoses because of its skip patterns; therefore, we were unable to examine participants with sub-clinical PTSD/MDD nor accurately measure PTSD/MDD symptoms (19). Excluding those with sub-clinical diagnoses may have also resulted in a loss of power. Future studies should utilize multiple time points before and after a disaster to more accurately examine the longitudinal course of PTSD and MDD.

Although the study was conducted in a longitudinal and prospective fashion, the results likely do not reflect causal relationships due to random error, potential Type II error, unmeasured confounding, moderators, or mediators. For example, the stressor questionnaire did not measure the individual’s appraisal of the stressor his/her coping response, the stressor’s contextual meaning, the frequency/load of the stressful events, and/or whether the person achieved complete mastery over the stressor (47). This information is pertinent to providing stronger evidence for the inoculation hypothesis – we strongly recommend that future studies examining stress response include these indicators (48). Further, the LTE measured stressors from the 6 months prior to the baseline assessment. This is likely not a large enough timeframe to capture the extent to which people may have experienced life stressors, which may have led to biased results. Finally, findings may not necessarily generalize to other populations outside of Chile.

Despite these limitations, the current study has many unique strengths. Analyses took advantage of a rare opportunity to study adults who had undergone a psychiatric and stressor evaluation in a large sample prior to exposure to one of the most powerful earthquakes in history, thus providing a clearer understanding of the pre-existing risk factors for developing PTSD and MDD (18). This type of rich longitudinal data does not exist in the disaster literature (14). Previous studies that have attempted to address these issues have been severely limited by small convenience samples, lack of diagnostic instruments, and scarcity of pre-disaster information (2, 18). The current study overcomes these limitations and allows for testing of hypotheses not previously possible using a methodologically robust study design. This information is critical to understanding variations in risk of PTSD and/or MDD, with the overall goal of identifying those who may need mental health treatment after a disaster (18). By examining who has truly new-onset PTSD and MDD after a natural disaster, the causal mechanisms of these illnesses can be more accurately determined.

Conclusions

Among individuals with no prior PTSD or MDD, this study examined whether a history of exposure to various types of stressors before the 2010 disaster provided inoculation, or protected against, the development of post-disaster PTSD and/or MDD in a longitudinal cohort of Chilean adults. Analyses took advantage of a unique and rare opportunity to examine a large sample of adults who had undergone a structured psychiatric diagnostic interview prior to being exposed to one of the most powerful earthquakes in history, thus providing a clearer understanding of the trajectory of PTSD and/or MDD and their determinants (18). An increased knowledge regarding the individual variations of these disorders is essential to informing targeted mental health interventions after a natural disaster, especially in unstudied populations (13).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

We would like to thank those who participated in this study and our colleagues in Chile who graciously shared their data with us.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health [C.F., F31MH104000 and K.K., 5T32MH017119–30] and FONDEF Chile [B.V., D021–1140 and B.V., 1110687].

Footnotes

Declaration of Interests: None

Data Availability: Authors have ongoing access to de-identified data.

References

- 1.Meichenbaum D, Novaco R. Stress inoculation: a preventative approach. Issues in mental health nursing. 1985; 7(1–4): 419–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Updegraff JA, Taylor SE. From vulnerability to growth: Positive and negative effects of stressful life events. In: Loss and Trauma: General and Close Relationship Perspectives (ed Miller H): 3–28. Brunner-Routledge, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Southwick SM, Litz BT, Charney D, Friedman MJ. Resilience and Mental Health: Challenges Across the Lifespan. Cambridge University Press, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seery MD, Leo RJ, Lupien SP, Kondrak CL, Almonte JL. An upside to adversity?: moderate cumulative lifetime adversity is associated with resilient responses in the face of controlled stressors. Psychological science. 2013; 24(7): 1181–9.23673992 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hammen C Stress and depression. Annual review of clinical psychology. 2005; 1: 293–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yehuda R Risk and resilience in posttraumatic stress disorder. The Journal of clinical psychiatry. 2004; 65 Suppl 1: 29–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van der Kolk BA, McFarlane AC, Weisaeth L. Traumatic Stress: The Effects of Overwhelming Experience on Mind, Body, and Society. The Guilford Press, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Breslau N, Chilcoat HD, Kessler RC, Davis GC. Previous exposure to trauma and PTSD effects of subsequent trauma: results from the Detroit Area Survey of Trauma. The American journal of psychiatry. 1999; 156(6): 902–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farb NA, Irving JA, Anderson AK, Segal ZV. A two-factor model of relapse/recurrence vulnerability in unipolar depression. Journal of abnormal psychology. 2015; 124(1): 38–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Monroe SM, Harkness KL. Life stress, the “kindling” hypothesis, and the recurrence of depression: considerations from a life stress perspective. Psychol Rev. 2005; 112(2): 417–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Breslau N, Peterson EL, Schultz LR. A second look at prior trauma and the posttraumatic stress disorder effects of subsequent trauma: a prospective epidemiological study. Archives of general psychiatry. 2008; 65(4): 431–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cougle JR, Resnick H, Kilpatrick DG. Does prior exposure to interpersonal violence increase risk of PTSD following subsequent exposure? Behaviour research and therapy. 2009; 47(12): 1012–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Santos R, Byrnes B, Lane P. More than 2 million affected by earthquake, Chile’s president says. CNN; 2010. http://www.cnn.com/2010/WORLD/americas/02/27/chile.quake/. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Norris FH, Galea S, Friedman MJ, Watson PJ Methods for Disaster Mental Health Research Guilford Press, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 15.King M, Weich S, Torres-Gonzalez F, Svab I, Maaroos HI, Neeleman J, et al. Prediction of depression in European general practice attendees: the PREDICT study. BMC public health. 2006; 6: 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.King M, Walker C, Levy G, Bottomley C, Royston P, Weich S, et al. Development and validation of an international risk prediction algorithm for episodes of major depression in general practice attendees: the PredictD study. Archives of general psychiatry. 2008; 65(12): 1368–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bottomley C, Nazareth I, Torres-Gonzalez F, Svab I, Maaroos HI, Geerlings MI, et al. Comparison of risk factors for the onset and maintenance of depression. The British journal of psychiatry : the journal of mental science. 2010; 196(1): 13–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fernandez CA, Vicente B, Marshall B, Koenen KC, Arheart KL, Kohn R, et al. Longitudinal course of disaster-related PTSD among a prospective sample of adult Chilean natural disaster survivors. International journal of epidemiology. 2016: 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization. Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI, Version 2.1). Geneva, Switzerland: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robins LN, Wing J, Wittchen HU, Helzer JE, Babor TF, Burke J, et al. The Composite International Diagnostic Interview. An epidemiologic Instrument suitable for use in conjunction with different diagnostic systems and in different cultures. Archives of general psychiatry. 1988; 45(12): 1069–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Andrews G, Peters L. The psychometric properties of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview. Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology. 1998; 33(2): 80–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kessler RC, Ustun TB. The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative Version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). International journal of methods in psychiatric research. 2004; 13(2): 93–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vicente B, Kohn R, Rioseco P, Saldivia S, Levav I, Torres S. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R disorders in the Chile psychiatric prevalence study. The American journal of psychiatry. 2006; 163(8): 1362–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vicente B, Kohn R, Rioseco P, Saldivia S, Navarrette G, Veloso P, et al. Regional differences in psychiatric disorders in Chile. Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology. 2006; 41(12): 935–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vielma M, Vicente B, Rioseco P, Castro P, Castro N, Torres S. Validacion en Chile de la entrevista diagnostica estandarizada para estudios epidemiologicos CIDI. Revista de Psiquiatria. 1992; 9: 1039–49. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brugha TS, Cragg D. The List of Threatening Experiences: the reliability and validity of a brief life events questionnaire. Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1990; 82(1): 77–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Michalak EE, Tam EM, Manjunath CV, Yatham LN, Levitt AJ, Levitan RD, et al. Hard times and good friends: negative life events and social support in patients with seasonal and nonseasonal depression. Canadian journal of psychiatry Revue canadienne de psychiatrie. 2004; 49(6): 408–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Friedman MJ, Keane TM, Resick PA. Handbook of PTSD: Science and Practice. The Guilford Press, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brewin CR, Andrews B, Valentine JD. Meta-analysis of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 2000; 68(5): 748–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ozer EJ, Best SR, Lipsey TL, Weiss DS. Predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder and symptoms in adults: a meta-analysis. Psychological bulletin. 2003; 129(1): 52–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robins JM, Hernan MA, Brumback B. Marginal structural models and causal inference in epidemiology. Epidemiology. 2000; 11(5): 550–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cole SR, Hernan MA. Constructing inverse probability weights for marginal structural models. American journal of epidemiology. 2008; 168(6): 656–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cuschieri S. The STROBE guidelines. Saudi J Anaesth. 2019; 13(Suppl 1): S31–S4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gotzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int J Surg. 2014; 12(12): 1495–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.StataCorp. 2015. Stata Statistical Software: Release 14. College Station TSL. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dienes KA, Hammen C, Henry RM, Cohen AN, Daley SE. The stress sensitization hypothesis: understanding the course of bipolar disorder. Journal of affective disorders. 2006; 95(1–3): 43–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nurius PS, Uehara E, Zatzick DF. Intersection of Stress, Social Disadvantage, and Life Course Processes: Reframing Trauma and Mental Health. Am J Psychiatr Rehabil. 2013; 16(2): 91–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McLaughlin KA, Conron KJ, Koenen KC, Gilman SE. Childhood adversity, adult stressful life events, and risk of past-year psychiatric disorder: a test of the stress sensitization hypothesis in a population-based sample of adults. Psychological medicine. 2010; 40(10): 1647–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Harkness KL, Hayden EP, Lopez-Duran NL. Stress sensitivity and stress sensitization in psychopathology: an introduction to the special section. Journal of abnormal psychology. 2015; 124(1): 1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hankin BL, Badanes LS, Smolen A, Young JF. Cortisol reactivity to stress among youth: stability over time and genetic variants for stress sensitivity. Journal of abnormal psychology. 2015; 124(1): 54–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Karam EG, Friedman MJ, Hill ED, Kessler RC, McLaughlin KA, Petukhova M, et al. Cumulative traumas and risk thresholds: 12-month PTSD in the World Mental Health (WMH) surveys. Depression and anxiety. 2014; 31(2): 130–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miller KE, Omidian P, Rasmussen A, Yaqubi A, Daudzai H. Daily stressors, war experiences, and mental health in Afghanistan. Transcult Psychiatry. 2008; 45(4): 611–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Newnham EA, Pearson RM, Stein A, Betancourt TS. Youth mental health after civil war: the importance of daily stressors. The British journal of psychiatry : the journal of mental science. 2015; 206(2): 116–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kubiak SP. Trauma and cumulative adversity in women of a disadvantaged social location. The American journal of orthopsychiatry. 2005; 75(4): 451–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ruscio AM, Gentes EL, Jones JD, Hallion LS, Coleman ES, Swendsen J. Rumination predicts heightened responding to stressful life events in major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder. Journal of abnormal psychology. 2015; 124(1): 17–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fernandez CA, Loucks E, Arheart K, Hickson D, Kohn R, Buka SL, et al. Evaluating the effects of coping, social support and optimism on components of Allostatic Load – The Jackson Heart Study. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2015; 12(E165). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Monroe SM. Modern approaches to conceptualizing and measuring human life stress. Annual review of clinical psychology. 2008; 4: 33–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.