Abstract

Background:

Evidence on effective engagement of diverse participants in AD prevention research is lacking.

Objectives:

To quantify recruitment source in relation to race, ethnicity, and retention.

Design:

Prospective cohort study.

Setting:

University lab.

Participants:

Participants included older adults (N=1170) who identified as White (86%), Black (8%), and Hispanic/Latino ethnicity (6%).

Measurements:

The Cognitive Aging Lab Marketing Questionnaire assessed recruitment source, social media use, and research opportunity communication preferences.

Results:

Effective recruitment methods and communication preferences vary by race and ethnicity. The most common referral sources were postcards for racial minorities, friend/family referrals for Hispanic/Latinos, and the newspaper for Whites. Whereas Whites preferred email communications, Hispanic/Latinos preferred texts.

Conclusions:

Recruiting diverse samples in AD prevention research is clinically relevant given high AD-risk of minorities and that health disparities are propagated by their under-representation in research. Our questionnaire and these results may be applied to facilitate effective research engagement.

Keywords: enrollment, retention, diversity, research engagement

INTRODUCTION

One of the most pressing public health needs is to identify ways to prevent or delay dementia such as Alzheimer’s disease [AD; 1]. Dementia such as AD increases in prevalence with age, is the most expensive medical condition in the US [2], and afflicts more than 6 million Americans [3, 4]. Although funding for AD prevention research is increasing, many trials fail to meet enrollment goals [5]. A further challenge is enrolling diverse participants to represent individuals from various racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic backgrounds [6]. These factors confer AD risk, with individuals who are Black/African American or Hispanic/Latino at highest AD-risk [7]. Fargo et al. [8] assert that the most significant obstacle to clinical research progress is recruitment and retention, especially of minorities. These obstacles compromise the statistical power and generalizability of studies, hindering scientific progress [9]. Furthermore, health disparities may be propagated by the under-representation of minorities in clinical research [10]. However, tools for quantifying recruitment effectiveness are lacking.

Overall, studies to identify effective recruitment for AD research have used mixed methods and varying measures, making direct comparisons across studies and generalization to diverse populations difficult [11]. Although the challenges of recruiting patients with dementia for AD research have been examined [e.g., 5, 12, 13], engagement of healthy older adults in AD prevention research is not well studied. Of the studies we identified reporting on recruitment strategies for enrolling healthy older adults in AD prevention research [14–19], half did not compare the effectiveness of different recruitment techniques. There are several studies that report on recruitment strategies for enrolling healthy older adults into registries for AD research [e.g., 20, 21–23]. However, rate of conversion from registry enrollment to enrollment in clinical trials is largely unreported.

Some studies have examined recruitment for hypothetical AD prevention research participation or have characterized healthy cohorts for subsequent AD research. Zhou and colleagues [16] examined willingness to participate in a hypothetical AD prevention study among healthy older adults who identified as either Black (n=47) or White (n=78). Participants who were Black were more likely to be recruited through a community liaison (36%) while participants who were White were more likely to be recruited via a participant registry (33%). Community talks were an equally effective recruitment source. Participants who were White were more likely to indicate willingness to enroll in subsequent AD prevention research. Romero and colleagues [22] applied community engagement to develop a registry of healthy older adults interested in AD prevention research and measured subsequent participation rates in the PREPARE study. PREPARE characterized a healthy cohort for future AD research but did not require a commitment to clinical trial participation. Registrants (N=2,311) were most likely to be successfully recruited through presentations 22.5% or health fairs 14.7%. Recruitment method effectiveness by participant race or ethnicity was not reported. Overall, 63% of registrants agreed to participate in PREPARE. Among 31% of the registrants who were Black, only 15% subsequently enrolled in PREPARE. Although, neither of these studies quantified recruitment for AD prevention clinical trials, results suggest that approaches will be differentially effective to engage participants who are Black.

In an AD prevention study enrolling cognitively healthy veterans [14], 1459 older adults were contacted either by mail or via face-to-face encounters through clinics or at open-house presentations. The researchers also used radio advertisements and flyers for recruitment. Only 18–25% of participants recruited through mailings enrolled in the study while 40% of those reached through face-to-face encounters enrolled. The authors concluded that although mailings are more cost effective, that face-to-face encounters result in a higher yield. Recruitment method effectiveness by participant race or ethnicity was not reported.

Stout et al. [24] retrospectively compared the effectiveness of using social media (e.g., flyers on Facebook, NextDoor) to traditional methods (e.g., newspaper ad and article, presentations, word-of-mouth) of recruiting older adults for a longitudinal study examining driving outcomes. Social media was the recruitment source for 18.5% of enrolled participants: all of whom were non-Hispanic White. Journalistic coverage in the local general newspaper was the recruitment source for the largest number (53%) of enrolled participants who were non-Hispanic White, and paid advertisement in the local Black community newspaper accounted for the largest number of enrolled participants who were Black (37.5%). However, this was a retrospective study regarding recruitment for driving research (i.e., not an AD prevention clinical trial).

Overall, few studies have examined research engagement in AD prevention clinical trials and measures for quantifying recruitment referral source are not well established. Further, to our knowledge, no AD prevention studies have examined referral source in relation to retention or reported participant preferences for communication of research opportunities. Recent literature on retention for clinical trials involving patients with AD emphasizes the need to examine strategies to reduce patient drop-out [25].

We investigated recruitment and retention in the Preventing Alzheimer’s with Cognitive Training trial (PACT; NCT03848312). We devised, piloted, and refined the Cognitive Aging Lab Marketing Questionnaire to quantify and evaluate recruitment source. The questionnaire assesses how participants received information about the study and further quantifies study participants’ use of social media, preference for communication methods about research opportunities, and motivations for research participation. Our primary objective was to examine recruitment source by race and ethnicity as well as the relationship of recruitment source to study retention. We further compared social media use and preferences for communications about research opportunities by race and ethnicity.

METHODS

Participants

The sample included N=1170 older adults recruited for the PACT study at the University of South Florida at the time of data extraction. The study was approved by the Western Institutional Review Board, funded by the National Institute on Aging, and registered at Clinicaltrials.gov (NCT03848312). All participants provided informed consent. Enrollment began on February 19, 2019 and data were extracted on September 18, 2020. From this sample, n=872 were enrolled in the study.

Participants were required to be at least 65 years of age and have the ability to speak, understand, and read English or Spanish. Adequate sensorimotor capacity to perform the computer exercises and auditory capacity to understand conversational speech were also required for inclusion. Participants were required to have the ability to understand and be willing to complete and adhere to study procedures. Participants were required to have a Montreal Cognitive Assessment score >=26 [27]. We excluded those with self-reported diagnoses of mental illness (e.g., schizophrenia) that could interfere with ability to adhere to study procedures. Those with moderate or worse depressive symptoms as determined by scores on the 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale of ≥5 were excluded [28]. Individuals who self-reported completing 10 or more hours of a computerized cognitive training program in the last 5 years or use of medications typically prescribed for dementia were excluded. Lastly, persons with self-reported diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment, dementia, stroke, traumatic brain injury, brain tumor, or a neurological disorder that affects cognition or would interfere with the ability to benefit from the study intervention (e.g., Parkinson’s disease) were excluded.

Participants ranged in age from 65 to 95 years (M=72.24, SD=5.38) and education levels ranged from 8 to 20 years (M=16.01, SD=2.42). Our goal was to enroll a sample to appropriately represent the US population of older adults including 8.5% Blacks and 3.5% Asian Americans, with 7% Hispanic/Latino ethnicity. The resulting study sample primarily included individuals who identified as White (86%), Black/African American (8%), Asian (1%), or other (4%). Seventy-one participants identified as Hispanic or Latino (6%). Sixteen participants refused to report race and one refused to report ethnicity. For subsequent analyses, race was recoded as White (n=1007) versus other minorities (n=147).

Measures

We devised the Cognitive Aging Lab Marketing Questionnaire to quantify and track recruitment source, track study marketing effectiveness, and to determine participants use of social media and preferences for communication about research opportunities. The questionnaire consists of eight questions and is available upon request to the corresponding author. The first version of the questionnaire included an open-ended question to quantify referral source, “How did you hear about our study?” and was piloted among 550 older adult research participants who were recruited for three different cognitive intervention studies with the aim of preventing AD. Qualitative analyses of the participants’ responses identified the most common referral sources as: postcard, friend/family referral, advertisement, library, radio, or newspaper. In version 2, the referral source question format was changed from an open-ended response to include these possible categorical responses. We also added both Facebook and ‘other’ as response options. Version 2 was completed by 538 of the PACT study participants. We examined the resulting ‘other category’ responses and in version 3, we added additional options of community talks, as well as specific referral sources relevant to PACT including memory screening, Trial Match, and two local community engagement programs. In all versions, question 1 ascertained recruitment referral source (see Table 1). Versions 2 and 3 included an ‘other’ option for sources not listed. If ‘other’ was chosen, a comment field was completed to further specify the referral source. Two raters independently coded all version 1 responses as well as the version 2 and 3 ‘other’ referral source responses. Inter-rater reliability of the cases recoded by the two raters was acceptable at Kappa of .702 (95% CI .701–.704). Discrepant codings were reviewed, and consensus was achieved to quantify the source for each study participant. The second question of the CAL Marketing Questionnaire asks participants to indicate any community organizations they are a part of that would be interested in learning about research. The third question asks whether they have accessed our webpage. Data from the latter two questions were regularly examined (by participant race and ethnicity) and used to evaluate existing and plan new recruitment efforts during the study. Questions 4–6 ask whether participants use social media (Facebook, Twitter, or other). Question 7 determines participants’ preferred methods for communication about research opportunities (participants indicated yes or no for options of phone, mail, email, text, and could indicate more than one option). Question 8 is an open-ended question that asks participants to describe their motivation for research participation. For our objectives, data for questions 2, 3 and 8 were not included in analysis.

Table 1.

Frequency of referral sources of participants recruited for the Preventing Alzheimer’s with Cognitive Training (PACT) Trial.

| Recruitment Referral Source | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Newspaper | 196 (16.8%) |

| Friend/Family | 192 (16.4%) |

| Postcard/Mail | 181 (15.5%) |

| Community talk | 100 (8.5%) |

| Radio | 63 (5.4%) |

| Phone Call | 53 (4.5%) |

| Ad | 52 (4.4%) |

| 41 (3.5%) | |

| 39 (3.3%) | |

| University publications or programs | 34 (2.9%) |

| Memory screening | 32 (2.7%) |

| TV | 32 (2.7%) |

| Library | 30 (2.6%) |

| Flyer or poster or table tents | 26 (2.2%) |

| Internet | 25 (2.1%) |

| Other | 24 (2.1%) |

| PACT Staff | 15 (1.3%) |

| Churches | 11 (0.9%) |

| Health fairs or Senior games | 11 (0.9%) |

| Do not know | 9 (0.8%) |

| Trial Match | 2 (0.2%) |

| Alzheimer’s Association Discoveries Program | 2 (0.2%) |

Procedure

Participants were recruited for a randomized trial (i.e., PACT) designed to test the effectiveness of computerized cognitive speed of processing training to reduce incidence of mild cognitive impairment or dementia. Potential participants were telephone screened to determine if they met the initial inclusion criteria. After obtaining consent, eligibility was further assessed at an in-person screening visit by completing brief memory and depression screenings, and the Cognitive Aging Lab Marketing Questionnaire was completed. Demographics, data from the questionnaire, and attrition rates were analyzed.

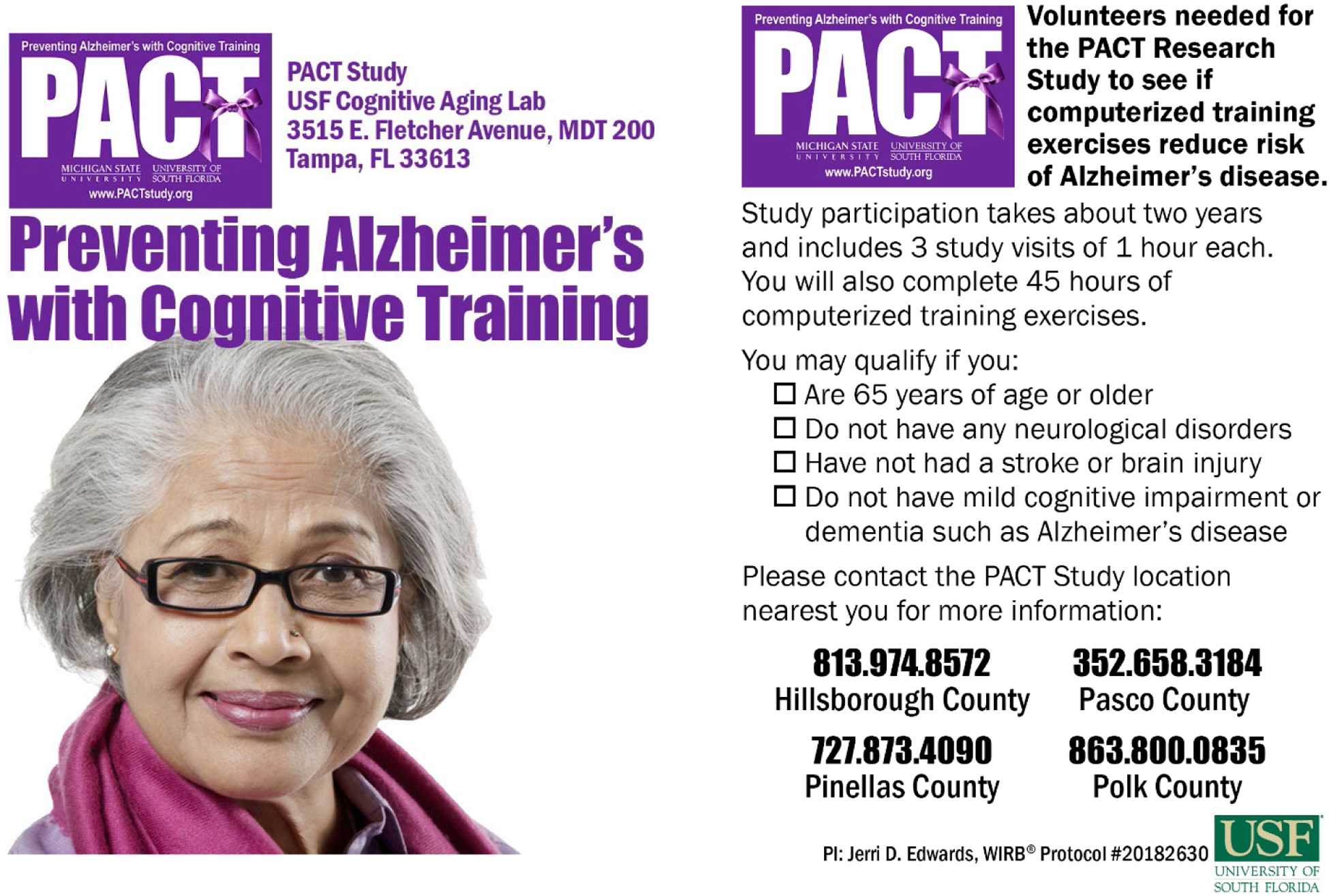

Two USF professors from the School of Mass Communications with expertise in advertising and marketing worked with the Principal Investigator and Study Coordinator as well as our Community Advisory Board to design the recruitment materials. The color purple was used due to its association with AD. Images that represented our target audience of older adults, male and female, and including persons of various race and ethnicity were incorporated. The goals for marketing materials included headlines/language that resonated with our target audience, had a strong call to action, and encouraged participation. Finally, a local ad agency with experience developing social media advertisements was contracted to develop the Facebook campaign. Materials were developed in English and then translated into Spanish. An example of a marketing handout is shown in Figure 1. Other examples of marketing material can be found on our study website Pactstudy.org or acquired by contacting the corresponding author.

Figure 1.

Example PACT study marketing materials.

Recruitment techniques included postcard mailings (10 mailings to 57,250 persons), TV and radio interviews (including stations with primarily Hispanic/Latino or Black audiences), and paid advertisements in newspapers (including newspapers with readers who are primarily Hispanic/Latino or Black). Letters about the study were sent to individuals who previously completed community memory screenings and to email lists relevant to older adults. Flyers, posters, and table toppers were distributed in various locations including at least 61 libraries, 17 medical facilities, 34 restaurants, 11 senior centers, and 17 senior communities. We deliberately placed materials in community locations with high populations of Blacks and/or Hispanic/Latinos. We used two Facebook advertising campaigns: one targeting a general audience and the other focused on reaching older adults who were Black or Hispanic/Latino. Posts about the study and recruitment events were regularly made on the PACT study Facebook page. Community engagement strategies at health fairs, senior adult events, and churches focused on increasing awareness of research participation opportunities and providing educational talks about brain health and dementia. The study was listed online at clinicaltrials.gov and in registries such as Trial Match and the Alzheimer’s Prevention Registry. Retention efforts included emailing a study newsletter every 6 months interspersed with mailing greeting cards every 6 months. The greeting cards served to thank participants for their ongoing study participation.

Statistical Analyses

Chi Square analyses were applied to examine if there were differences in referral source by race, ethnicity, or attrition as well as to compare participants use of social media and communication preferences for research opportunities. Additional sensitivity analyses were added by using binomial logistic regression to examine potential predictors of retention.

RESULTS

Recruitment Sources and Attrition

Table 1 shows the frequency of recruitment referral sources. The four most common single referral sources were newspaper (16.8%), friend/family (16.4%), postcard/mail (15.5%), and community talk (8.5%). See Table 1 for frequency of referral sources. For analyses, recruitment sources were recoded into the four most common sources (newspaper, friend/family, postcard/mail, community talk) versus other sources. Table 2 shows the frequency of the recoded referral source responses by race, ethnicity, and attrition. Chi-square was calculated to determine if there were differences in recruitment source by race or ethnicity. There were statistically significant differences in recruitment source by race, X2(4, n=1154)=25.08, p<.001, and by ethnicity, X2(4, n=1169)=13.14, p=.011. Minorities were more likely to be recruited by ‘other’ techniques than Non-Hispanic Whites. Results indicated that mailed postcards were the most common single source of recruitment for racial minorities (12.2%) whereas the most common source for Whites was the newspaper (18.4%). Those who were Hispanic or Latino were more likely to report being referred by a friend or family member (12.7%).

Table 2.

Referral Sources for the Preventing Alzheimer’s with Cognitive Training trial (PACT) by Race, Ethnicity, and Attrition.

| Race* | Ethnicity* | Attrition | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Referral Source | White (n=1007) | Other (n=147) | Not Hispanic or Latino (n=1098) | Hispanic or Latino (n=71) | Enrolled (n=742) | Withdrew (n=130) |

| Newspaper | 185 (18.4%) | 9 (6.1%) | 193 (17.6%) | 3 (4.3%) | 129 (17.4%) | 24 (18.5%) |

| Postcard/Mail | 29 (2.9%) | 18 (12.2%) | 182 (16.6%) | 1 (1.4%) | 18 (2.4%) | 5 (3.8%) |

| Community Talk | 84 (8.3%) | 11 (7.5%) | 95 (8.7%) | 5 (7.0%) | 64 (8.6%) | 9 (6.9%) |

| Friend/Family | 172 (17.1%) | 1 (0.7%) | 29 (2.6%) | 9 (12.7%) | 129 (17.4%) | 16 (12.3%) |

| All Other Sources | 537 (53.3%) | 108 (73.5%) | 599 (54.5%) | 53 (74.6%) | 402 (54.2%) | 76 (58.5%) |

Note. Overall, participants of minority race or ethnicity were most likely to be recruited from a variety of techniques. Those who were White were more likely to be recruited via newspaper, while participants of minority races were more likely to be recruited by mailed postcards. Those who were Hispanic or Latino were more likely to be recruited by friends or family. No significant differences were evident by attrition.

ps<.05

Additional Chi-square analyses were calculated to assess whether eligibility differed by race (Black, White, Other) or ethnicity (Hispanic, Non-Hispanic). There were no statistically significant differences in study exclusion by race, X2(2, n=1154)=2.35, p=.308; 13% of Whites were not eligible, 16% of Blacks were not eligible, and 18% of other minorities were not eligible. There were also no statistically significant differences in eligibility by ethnicity, X2(1, n=1169)=0.03, p=.862; 33% non-Hispanics and 31% of Hispanics/Latinos were not eligible.

At the time of data extraction, 130 participants had withdrawn from the study. Those who withdrew included individuals who identified as White (n=111) but also included persons who were Black/African American (n=11), Asian (n=1), biracial (n=1), or other (n=5). Individuals who withdrew included three who identified as Hispanic or Latino (n=3). Reasons for withdrawal included lack of interest (31.5%), being too busy/not available (29.2%), and 16.9% withdrew due to personal reasons. Chi-square was calculated to examine differences in recruitment source by attrition. There was no significant difference in recruitment source for those who were enrolled and retained (n=742) versus those who withdrew (n=130) from the study, X2(4, n=872)=3.39, p=.495.

Additional analyses were conducted to examine potential predictors of retention using binomial logistic regression. We examined recruitment source, age, education, race and ethnicity as predictors of attrition. No significant effects of recruitment source were evident, ps>.05. See Table 3 for effect sizes and statistics.

Table 3.

Logistic Regression Results for Predicting Attrition

| Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Referral source (post card, community talk, friend/family, or newspaper) | 0.99 | 0.95–1.04 | .845 |

| Age in years | 1.00 | 0.96–1.04 | .881 |

| Education level | 1.01 | 0.93–1.09 | .780 |

| Ethnicity (Hispanic and Non-Hispanic) | 0.33 | 0.10–1.08 | .067 |

| Race (Minorities and White) | 1.29 | 0.73–2.24 | .377 |

Social Media Use and Communication Preferences

Descriptive statistics of social media use indicated that the majority of participants use Facebook (62% of Whites, 57.1% of minority races, 66.2% of Hispanic/Latinos), but not many participants use Twitter (8.7% of Whites, 9.6% of minority races, 11.4% of Hispanic/Latinos) or other social media (1.4% of Whites, 2.1% of minority races, 2.8% of Hispanic/Latinos). No significant differences in social media use by race/ethnicity were evident (ps > .05). For all participants, the most commonly reported preference for communication method about research participation opportunities was e-mail (White 89.0%, minority races 81.6%, Hispanic/Latino 78.9%). The second most commonly reported preference for communication method was US mail by White (73.5%) and other race participants (74.1%) and by text for Hispanic/Latino participants (76.1%). Preferences did not vary by race, X2(1, n=1159)<1.44, ps>.05. Seventy-six percent of Hispanic/Latino ethnicity preferred to be contacted by text message, X2(1, n=1159)=4.63, p=.031, while 89% of Non-Hispanic Whites preferred email, X2(1, n=1167)=6.59, p=.010.

DISCUSSION

Effectiveness of recruitment strategies in AD prevention studies has not typically been systematically evaluated within and across research studies or ethnic/racial subgroups [29, 30]. To date, many previous studies investigating recruitment sources for AD prevention research have not compared effectiveness by race and ethnicity, and no studies have examined if retention varies by recruitment source. We devised the Cognitive Aging Lab Marketing Questionnaire as a tool to quantify and evaluate recruitment. The resulting data were applied to investigate racial or ethnic differences in recruitment source and to examine whether recruitment source was related to participant retention. We further examined participants’ use of social media and communication preferences for research opportunities.

Overall, participants were recruited from a large variety of sources, particularly racial and ethnic minorities. Results indicated the four most common single referral sources were newspaper, friend/family, postcard/mail, and community presentations. There were significant differences in referral source by race and ethnicity. For racial minorities, the most common single referral source was mailed postcards, whereas for Whites the newspaper was more likely to be a referral source. On the other hand, individuals who were Hispanic/Latino were more likely to be referred by a family member or friend. Results are similar to Karran et al. [14] who indicated that mailings accounted for 68% of the enrolled participants as well as Stout et al. [24] who found that newspaper articles or ads were the most common referral source for Non-Hispanic Whites and Blacks, respectively. Our results extend prior results by showing that referral sources for AD prevention research significantly vary not only by race but also by ethnicity. Overall, mailings, newspapers, and community presentations were successful referral sources for Whites and racial minorities. Our results further indicated that participants who were Hispanic or Latino are more likely to be referred by family and friends. Implications are that various recruitment techniques are required to obtain diverse samples. Results showed no significant difference in recruitment source by attrition. Further investigation of moderators of retention is needed. Specifically, future studies should examine relationship of participant motivations to retention, as well as analyze racial or ethnic differences in motivations. Such information can guide successful marketing campaigns for recruitment.

Results regarding social media preferences indicated the majority of participants used Facebook and only a small percentage used Twitter or other forms of social media, with no differences in social media use by race or ethnicity. This is consistent with recent Pew data regarding older adult social media usage [31]. Although in the current study social media was not one of the four most common referral sources, social media may be a viable platform for reaching prospective older adult participants [24]. However, evidence to date indicates newspaper ads seem to be more effective for recruiting older adults overall, and social media advertising may be more effective for recruiting Whites versus minorities. Further research is needed to determine if social media is effective for enrolling diverse AD prevention research participants.

The most commonly reported preference for communication method about research opportunities was e-mail, followed by US mail and text. Interestingly, preferences for hearing about research opportunities significantly varied by ethnicity. We primarily relied on US mail and sent some emails, but did not attempt to recruit by text, which was preferred by Hispanics/Latinos. Overall, researchers need to be aware of these preferences and deploy various recruitment strategies and communication avenues to successfully recruit diverse older adults for AD prevention research.

This study is not without limitations. To advance our understanding of effective research engagement, future studies should apply more rigorous methodology such as embedded trials to systematically compare recruitment and retention strategies [32]. We report on participant recruitment that was limited to the Greater Tampa Bay area of Florida, in the US, and the study was a non- pharmacological intervention, potentially limiting generalization.

In analyzing the marketing questionnaire data, we found it difficult at times to distinguish referral sources. Data revealed that some participants report a method or mode (e.g., flyer, poster, phone call, or advertisement) while others report a source or location (e.g., library, clinic, newspaper, radio). We have now updated the questionnaire to inquire about both the method/mode as well as the source/location to better quantify recruitment. Further, some participants could not adequately recall their original referral source. For example, several indicated telephone call as their referral source – which would not actually be the original source as we did not conduct any ‘cold calling’. Others stated they did not know how they learned of the study. Thus, we are currently devising an electronic tool to quantify referral source using recognition. This tool displays recruitment materials, inquires if participants have seen such materials, and if so, where. We have also devised a database to track all marketing efforts and related expenses so that we may identify cost of recruitment approaches per participant enrolled in the future. We hope these tools will be implemented across AD prevention research studies to systematically investigate and improve research engagement of diverse older adults.

Overall, we found that using the Cognitive Aging Lab Marketing Questionnaire during the study was helpful to quantify successful approaches and modify our recruitment strategies as needed. Resulting data revealed varying effectiveness of recruitment approaches as well as different communication preferences by race and ethnicity. The Cognitive Aging Lab Marketing Questionnaire is a valuable tool to quantify recruitment sources and can be applied to improve enrollment of diverse participants from various racial- and ethnic-, backgrounds. Findings of this study provide useful information to guide future researchers to use effective recruitment sources for enrolling diverse participants into AD prevention studies. Enhancing enrollment of diverse samples in AD prevention research is important given minorities’ high risk for AD. Including minorities in AD prevention research may ultimately help to decrease health disparities.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to acknowledge Kevin Hawley and Coby O’Brien who designed our marketing plan for the PACT study. We also thank Dr. Alisa Houseknecht and the entire PACT study team as well as the University of South Florida Cognitive Aging Lab staff and volunteers who contributed to data collection. We further acknowledge the PACT Data Safety Monitoring Board for their advice and contributions including Drs. Neelum Aggarwal, Olivio Clay, Jianghua He, and Jyoti Mishra. We are particularly grateful for our numerous research study participants and community partners.

FUNDING

The PACT study was funded by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Aging (AG058234). The sponsor did not contribute to the preparation, review, or approval of this manuscript and did not play a role in the design or conduct of this study nor in data collection, analysis, or interpretation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sherzai D and Sherzai A, Preventing Alzheimer’s: Our most urgent health care priority. Am. J. Lifestyle Med, 2019. 13(5): p. 451–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hurd MD, Martorell P, Delavande A, Mullen KJ, and Langa KM, Monetary costs of dementia in the United States. N. Engl. J. Med, 2013. 368(14): p. 1326–1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Plassman BL, Langa KM, Fisher GG, et al. , Prevalence of dementia in the United States: The aging, demographics, and memory study. Neuroepidemiology, 2007. 29(1–2): p. 125–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knopman DS and Roberts RO, Estimating the number of persons with frontotemporal lobar degeneration in the US population. J. Mol. Neurosci, 2011. 45(3): p. 330–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grill JD and Galvin J, Facilitating Alzheimer’s disease research recruitment. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord, 2014. 28(1): p. 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Griffith DM and Griffith PA, Commentary on “Perspective on race and ethnicity in Alzheimer’s disease research”. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association, 2008. 4(4): p. 239–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mayeda ER, Glymour MM, Quesenberry CP, and Whitmer RA, Inequalities in dementia incidence between six racial and ethnic groups over 14 years. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association, 2016. 12(3): p. 216–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fargo K, Carrillo MC, Weiner MW, Potter WZ, and Khachaturian Z, The crisis in recruitment for clinical trials in Alzheimer’s and dementia: An action plan for solutions. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association, 2016. 12(11): p. 1113–1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.VanEpps EM, Volpp KG, and Halpern SD, Improving clinical trial enrollment with behavioral economics. Sci. Transl. Med, 2016. 20(8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Institute on Aging, Together we make the difference. National strategy for recruitment and participation in Alzheimer’s and related dementias clinical research 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Gilmore-Bykovskyi AL, Jin Y, Gleason C, et al. , Recruitment and retention of underrepresented populations in Alzheimer’s disease research: A systematic review. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions, 2019. 5: p. 751–770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grill JD and Karlawish J, Addressing the challenges to successful recruitment and retention in Alzheimer’s disease clinical trials. Alzheimers Res. Ther, 2010. 2(6): p. 34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Watson JL, Ryan LM, Silverberg N, Cahan V, and Bernard MA, Obstacles and opportunities in Alzheimer’s clinical trial recruitment. Health Aff. (Millwood), 2014. 33(4): p. 574–579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karran M, Guerrero-Berroa E, Schmeidler J, et al. , Recruitment of older veterans with diabetes risk for Alzheimer’s disease for a randomized clinical trial of computerized cognitive training. J. Alzheimers Dis, 2019. 69(2): p. 401–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tarrant SD, Bardachates K, Nicohols H, et al. , The effectiveness of small-group community-based information sessions on clinical trial recruitment for secondary prevention of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord, 2017. 31(2): p. 141–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou Y, Elashoff D, Kremen S, et al. , African Americans are less likely to enroll in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease clinical trials. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions, 2017. 3(1): p. 57–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schneiders T, Danner D, and McGuire CL, Incentives and barriers to research participation and brain donation among African Americans. Am. J. Alzheimers Dis. Other Demen, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Puchalt-Perales J, Shaw A, and McGee J, Preliminary efficacy of a recruitment educational strategy on Alzheimer’s disease knowledge, research participation attitudes, and enrollment among Hispanics. Hispanic Healthcare International, 2020. 18(3): p. 144–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Williams MM, Meisel MM, Williams J, and Morris JC, An interdisciplinary outreach model of African American recruitment for Alzheimer’s disease research. The Gerontologist, 2011. 51(suppl_1): p. S134–S141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walter S, Clanton TB, Langford OG, et al. , Recruitment into the Alzheimer Prevention Trials (APT) Webstudy for a Trial-Ready Cohort for Preclinical and Prodromal Alzheimer’s Disease (TRC-PAD). The Journal of Prevention of Alzheimer’s Disease, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Langbaum JB, High N, Nichols J, et al. , The Alzheimer’s Prevention Registry: A large internet-based participant recruitment registry to accelerate referrals to Alzheimer’s-focused studies. The Journal of Prevention of Alzheimers Disease, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Romero HR, Welsh-Bohmer KA, Gwyther LP, et al. , Community engagement in diverse populations for Alzheimer’s disease prevention trials. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord, 2014. 28(3): p. 269–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Green-Harris G, Coley SL, Koscik RL, et al. , Addressing disparities in Alzheimer’s disease and African-American participation in research: An asset-based community development approach. Front. Aging Neurosci, 2019. 11(125). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stout SH, Babulal GM, Johnson A, Williams MM, and Roe CM, Recruitment of African American and non-Hispanic White older adults for Alzheimer disease research via tradtional and social media: A case study. J. Cross Cult. Psychol, 2020. 35: p. 329–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bernstein OM, Grill JD, and Gillen DL, Recruitment and retention of participant and study partner dyads in two multinational Alzheimer’s disease registration trials. Alzheimer’s Research & Therapy, 13(1), 1–11. Alzheimers Res. Ther., 2021. 13: p. 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boada M, Santos-Santos MA, Rodríguez-Gómez O, et al. , Patient engagement: the Fundació ACE framework for improving recruitment and retention in Alzheimer’s disease research. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 62(3), 1079–1090. J. Alzheimers Dis., 2018. 62: p. 1079–1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. , The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 2005. 53(4): p. 695–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sheikh JI and Yesavage JA, Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS): Recent evidence and development of a shorter version. Clinical Gerontologist: The Journal of Aging and Mental Health, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wong R, Amano T, Lin S, Zhou Y, and Morrow-Howell N, Strategies for the recruitment and retention of racial/ethnic minorities in Alzheimer disease and dementia clinical research. Current Alzheimer Research, 2019. 16(5): p. 458–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dilworth-Anderson P, Introduction to the science of recruitment and retention among ethnically diverse populations. The Gerontologist, 2011. 51(S1): p. S1–S4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pew Research Center Internet & Technology. Social Media Fact Sheet. 2019; Available from: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/social-media/.

- 32.Treweek S, Bevan S, Bower P, et al. , Trial Forge Guidance 2: How to decide if a further Study Within A Trial (SWAT) is needed. Trials, 2020. 21(1): p. 33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]