Abstract

In Tanzania, suboptimal complementary feeding practices contribute to high stunting rates. Fathers influence complementary feeding practices, and effective strategies are needed to engage them. The objectives of this research were to examine the acceptability and feasibility of (1) tailored complementary feeding recommendations and (2) engaging fathers in complementary feeding. We conducted trials of improved practices with 50 mothers and 40 fathers with children 6–18 months. At visit 1, mothers reported current feeding practices and fathers participated in focus group discussions. At visit 2, mothers and fathers received individual, tailored counselling and chose new practices to try. After 2 weeks, at visit 3, parents were interviewed individually about their experiences. Interview transcripts were analysed thematically. The most frequent feeding issues at visit 1 were the need to thicken porridge, increase dietary diversity, replace sugary snacks and drinks and feed responsively. After counselling, most mothers agreed to try practices to improve diets and fathers agreed to provide informational and instrumental support for complementary feeding, but few agreed to try feeding the child. At follow‐up, mothers reported improved child feeding and confirmed fathers' reports of increased involvement. Most fathers purchased or provided funds for recommended foods; some helped with domestic tasks or fed children. Many participants reported improved spousal communication and cooperation. Families were able to practice recommendations to feed family foods, but high food costs and seasonal unavailability were challenges. It was feasible and acceptable to engage fathers in complementary feeding, but additional strategies are needed to address economic and environmental barriers.

Keywords: complementary feeding, complementary foods, family influences, formative research, infant feeding behaviour, support

Key messages.

Increasing dietary diversity, preparing thick porridge and stopping sugary snacks and drinks were acceptable and feasible for most mothers and supported by most fathers.

Fathers reported increased support for and involvement in complementary feeding; mothers confirmed almost all fathers purchased or provided funds for foods and a few helped with child feeding and other domestic tasks.

While not a focus of counselling, most mothers and fathers spontaneously reported that engaging fathers in complementary feeding led to improved communication and cooperation between spouses.

1. INTRODUCTION

Adequate complementary feeding practices are critical for child health, growth and development. Suboptimal complementary feeding practices negatively influence later morbidity, mortality and obesity risk, as well as cognitive, educational and economic outcomes (Bhutta et al., 2013; Michaelsen et al., 2017; Stewart et al., 2013). Recommended diets for children 6–23 months of age include feeding diverse and nutrient‐dense foods, animal‐source foods, fruits, and vegetables in addition to breastmilk and avoiding foods or drinks with added sugar or low nutrient value (UNICEF, 2020). Globally, less than 20% of children 6–23 months of age in low‐ and middle‐income countries (LMIC) receive a minimum acceptable diet (UNICEF, 2020). At the same time, the numbers of children 6–23 months of age consuming energy‐dense, nutrient‐poor foods are increasing (Jaacks et al., 2017; Pries et al., 2017). In Tanzania, 30% of children 6–23 months of age received a minimum acceptable diet with children receiving an average of three out of seven food groups (Ministry of Health Community Development Gender Elderly and Children (MOHCDGEC) [Tanzania Mainland] et al., 2019).

Providing adequate diets to children during the complementary feeding period can be difficult for caregivers due to limited resources, time and family support (Avula et al., 2013; Engle et al., 1999). Fathers influence complementary feeding practices (Bezner Kerr et al., 2008; Ochieng et al., 2017; Pelto & Armar‐Klemesu, 2015; Stewart et al., 2013; Thuita et al., 2015), especially access to the foods needed to increase dietary diversity (Sanghvi et al., 2017). In recognition of this influence, global guidance recommends including fathers in complementary feeding counselling and social and behaviour change communication (SBCC) activities (UNICEF, 2020). There is growing evidence that counselling and SBCC activities that engage fathers are associated with improved complementary feeding practices (Dinga et al., 2018; Hoddinott et al., 2018; Menon et al., 2016; Mukuria et al., 2016), but limited examples that directly assess the impact of father engagement (Martin et al., 2020). Designing programs for fathers that include specific, tailored recommendations is recommended to improve complementary feeding (Pelto & Armar‐Klemesu, 2015; Sanghvi et al., 2014).

To date, research about fathers' experiences becoming more involved in complementary feeding is limited (Martin et al., 2020). Quantitative intervention studies tend to focus on maternal reports of father support or fathers' knowledge and practices. Qualitative studies have reported on fathers' increased knowledge of complementary feeding (DeLorme et al., 2018; Downs et al., 2019), father involvement in decision making (Dinga et al., 2018), participatory methods to involve fathers in child care (Bezner Kerr, Lupafya, et al., 2016) and perceptions of masculinity and willingness to change gender norms and roles around child care (Bezner Kerr, Chilanga, et al., 2016). However, less is known about fathers' reactions to complementary feeding recommendations or their experiences supporting or practicing these recommendations. This research responds to this gap.

A review of complementary feeding SBCC interventions reported that effective interventions consistently used formative research to design appropriate interventions and messages (Fabrizio et al., 2014). Formative research can ensure that interventions are specific to the contextual factors that influence complementary feeding (Bentley et al., 2014). This formative research was conducted in the Lake Zone in Tanzania to inform the Addressing Stunting Early in Tanzania (ASTUTE) project, locally known as Mtoto Mwerevu (Swahili for “smart child”) (IMA World Health, 2020). Complementary feeding encompasses the timely introduction of foods at 6 months to complement breastmilk; adequate amounts, frequency, diversity and consistency of age‐specific foods; safe and hygienic food preparation; responsive feeding; and feeding during illness. This research focused on recommendations to improve feeding practices related to the amount, frequency, diversity and consistency of foods and responsive feeding. The objectives of this formative research were to (1) assess the acceptability and feasibility of tailored complementary feeding recommendations among mothers and fathers, and (2) explore fathers' willingness and experiences being more involved in complementary feeding.

2. METHODS

2.1. Trials of improved practices

Trials of improved practices (TIPs) is a formative research approach that involves a series of visits to participants' homes to test and refine nutrition and health recommendations to inform intervention design (Dickin et al., 1997). Based on participants' current practices, they receive several tailored recommendations and then select which practices to try. TIPs allow participants to try a recommended practice for a period of time and then provide feedback about the acceptability and feasibility based on their experience (Dickin et al., 1997; Dickin & Seim, 2013; Harvey et al., 2013). The results help researchers and program implementers identify potential barriers, develop strategies to overcome those barriers and remove or modify recommendations that are not feasible for participants (Harvey et al., 2013).

We conducted three TIPs visits: visit 1 to assess current roles and practices related to complementary feeding, visit 2 to provide tailored recommendations and ask participants to choose practices to try and visit 3 to follow up on participant experiences (Table S1 in the supporting information). Including fathers in TIPs was a novel approach and little was known about how to recommend and motivate specific practices. To better understand norms and attitudes among fathers, we conducted focus group discussions (FGDs) in place of individual interviews with fathers at visit 1. For visit 2, we prepared gender‐specific counselling guides (Supporting Information) based on nutrition counselling materials from the Tanzania Food and Nutrition Centre and previously conducted recipe trials with mothers in the study areas. Mothers who participated in the recipe trials did not participate in TIPs.

2.2. Study context

This study took place in rural areas within three of the five Lake Zone regions (i.e. Geita, Kagera and Mwanza) to represent areas with different staple foods (i.e. banana or maize). The rates of stunting among children under 5 years of age were 39%, 40% and 26% and the proportion of children 6–23 months who consumed a minimum acceptable diet were 28%, 18% and 30%, respectively (Ministry of Health Community Development Gender Elderly and Children (MOHCDGEC) [Tanzania Mainland] et al., 2019). Farming and fishing are common economic activities in the Lake Zone. Sukuma is the predominant ethnic group in Geita and Mwanza, and Haya is the predominant ethnic group in Kagera; both are patrilineal and patrilocal (Manji, 2000; Masele, 2020). In all three regions, it is common for rural families to live together in a homestead with their extended family, including the husband's parents and siblings (Masele, 2020). In the Lake Zone, as in many settings around the world (Doyle et al., 2014), traditional gender roles are common and social norms hold women responsible for household tasks and caregiving, as confirmed in our previous formative research related to breastfeeding (Matare et al., 2019). Typically, men are not involved in the care and feeding of infants and young children, and women have little decision‐making power (Masele, 2020). Women's empowerment indicators are lower in the Lake Zone compared to national levels (MoHCDGEC, 2015). Only 25% of married women in the Lake Zone reported making decisions either by themselves or jointly with their husband about their own health, major household purchases, and visiting their family, compared with 35% nationally. Similarly, 68% of women of reproductive age in the Lake Zone agree that a husband is justified in hitting or beating his wife for specific reasons, compared with 58% nationally (MoHCDGEC, 2015).

2.3. Study population

Two wards in each region were purposively selected to ensure diversity in population size and access to the district town centre, healthcare facilities and lake. One village was randomly selected from each ward. Based on accepted sampling approaches for qualitative research (Hagaman & Wutich, 2017; Sobal, 2001), the target sample size in each village was nine couples, or 54 total. Community health workers helped identify potential participants with infants and young children 6–18 months of age using predetermined criteria to ensure variation in child's age and mother's age, parity and educational status. Exclusion criteria were maternal age less than 15 years, a health condition that would interfere with trying recommended behaviours (either mother or child) and travel plans that would preclude follow‐up visits. After mothers consented to participate in the study, their male partners were invited to participate. One FGD was conducted in each village with fathers participating in TIPs. Additional fathers of children 6–18 months of age were recruited to participate in FGDs to have at least 10 participants per group.

2.4. Data collection

Three female and three male interviewers conducted interviews in Swahili. All interviewers were Tanzanian and were experienced qualitative data collectors, with bachelor's or master's degrees in nutrition or public health. They received a 10‐day training in TIPs and complementary feeding and were supervised by a community development specialist and two nutritionists. Interviewers were trained to share recommendations, but not pressure participants to select them as we were interested in participants' responses to the recommendations. Each participant was interviewed by the same interviewer at each visit. Interview‐interviewee pairs were gender‐concordant. With participant consent, all interviews and FGDs were audio recorded.

Interviewers collected data from mothers and fathers at three time points (Table S1). For mothers, at visit 1 they were asked about current feeding practices, which included infant feeding practices in the previous 24‐h period (World Health Organization, 2010) and 7‐day dietary diversity assessment to capture foods not eaten every day developed for this study; household hunger (Ballard et al., 2011); support they receive for complementary feeding; and additional support they would like. Fathers participated in FGDs for visit 1, followed by two visits. Focus group discussions with fathers explored knowledge and beliefs about child feeding, gender norms and roles related to the care and feeding of young children, and potential ways fathers could become more involved in complementary feeding. As part of the FGDs with fathers, we used a vignette (i.e. short story without an ending) to encourage reflection on the types of support husbands could provide for complementary feeding, a method that has been used successfully in Tanzania (Gourlay et al., 2014). The vignette described two brothers with different levels of involvement with their young children, and participants were encouraged to reflect on the circumstances in the story, suggest actions characters should take, and imagine how the story would end.

After the mother's first visit, the female interviewer shared mothers' current feeding practices and concerns with one to two supervisors and the male interviewer that would interview the father. As a group, they used the counselling guides to discuss potential recommendations and decided which recommendations to offer mothers and fathers at visit 2 based on feeding practices and family context. Families received different recommendations based on their circumstances. While the topics in the counselling guide were similar for mothers and fathers (e.g. feeding animal‐source foods, replacing sugary snacks with healthy ones), the specific actions were different based on their roles. Recommendations for mothers focused on direct feeding (e.g. feed animal‐source foods), whereas those for fathers included support for complementary feeding (e.g. purchase animal‐source foods) as well as direct feeding practices.

At visit 2, mothers and fathers were counselled individually about ways to improve complementary feeding practices. Interviewers asked participants to select one to two practices to try over a 2‐week period. Mothers and fathers were counselled individually to allow participants to speak freely about their thoughts and experiences about complementary feeding recommendations and father involvement. At visit 3, two weeks after receiving tailored nutrition counselling and selecting new practices to try, individual in‐depth interviews with mothers and fathers explored their experiences. Participants' selection and trial of recommended practices were tracked and tallied. Tallying allows comparison across recommendations to identify which were most commonly recommended to participants (reflecting frequency of non‐ideal practices) and which were most acceptable (reflecting initial perceptions of acceptability) (Dickin & Seim, 2013).

2.5. Data analysis

We used Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA) to summarise sociodemographic characteristics, child dietary recall data and participants' behavioural choices. Qualitative data included field notes from mothers' visits 1 and 2 and fathers' visit 2, as well as verbatim transcripts of the fathers' visit 1 FGDs and visit 3 in‐depth interviews for mothers and fathers. Interviewers took detailed notes during visits 1 and 2 and expanded their notes after each interview. Field notes were translated into English by independent translators and reviewed by each interviewer for accuracy. An independent translation firm transcribed father FGDs and mothers and fathers visit 3 interviews verbatim in Swahili, and then translated them into English.

Father FGDs were coded and analysed thematically by three study team members. Key themes were identified and summarised in a matrix. English transcripts of visit 3 interviews with mothers and fathers were qualitatively analysed by seven team members. First, we manually coded the women's transcripts. To ensure coding consistency, all analysts independently read and manually coded the same two transcripts. The team then reviewed the coded transcripts as a group and collaboratively created a codebook. The team agreed on code names, definitions and inclusion and exclusion criteria (DeCuir‐Gunby et al., 2010; Macqueen et al., 1996). We continued to individually code and review transcripts with frequent debriefings and codebook refinement. After reviewing the same five transcripts, we determined that the level of coding agreement was consistent across the analysis team, and no longer required each transcript be read by all team members. All transcripts were then coded in Atlas.ti Version 8 (Scientific Software Development, Berlin, Germany) with at least two analysts independently coding each transcript. The analysis team met frequently to discuss emergent codes and any discrepancies until reaching consensus, iteratively revising the codebook. Major themes and findings were discussed during peer debriefings. The analysis team followed the same approach for the fathers' visit 3 transcripts, starting with the same codebook and adding additional codes specific to fathers' experiences. In addition, visit 3 interview transcripts from mother–father pairs were analysed together as a unit and summarised in a matrix to examine couple communication and cooperation and consistency of responses within couples.

2.6. Ethical considerations

The Cornell University Institutional Review Board and the National Institute for Medical Research in Tanzania approved this study. All participants gave written informed consent.

3. RESULTS

Fifty mothers and 40 fathers completed all three TIPs visits. Participant characteristics are summarised in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Participant characteristics and child feeding practices at study entry a

| Mothers n = 50 | Fathers n = 40 | |

|---|---|---|

| Age in years, mean (range) | 28.7 (17–45) | 35 (22–62) |

| Education | ||

| No education | 12 (24%) | 5 (13%) |

| Some primary | 5 (10%) | 4 (10%) |

| Completed primary | 31 (62%) | 23 (58%) |

| Some secondary | 2 (4%) | 8 (20%) |

| Work | ||

| Not working outside the home | 2 (4%) | 0 |

| Daily wage worker | 1 (2%) | 3 (8%) |

| Agricultural worker in own field | 42 (84%) | 35 (88%) |

| Business/vendor | 5 (10%) | 0 |

| Other | 0 | 2 (5%) |

| Number of children, mean (range) | 3 (1–8) | 5 (1–14) |

| Child age in months, mean (range) | 10.4 (6–18) | 10.9 (6–18) |

| Child sex | ||

| Male | 31 (62%) | 26 (65%) |

| Female | 19 (38%) | 14 (35%) |

| Marital status | ||

| Single/never married | 1 (2%) | |

| Married/living with partner | 50 (94%) | |

| Separated/divorced | 2 (4%) | |

| Spouse home every day in the past week | 46 (92%) | |

| Spouse travels often | 13 (26%) | |

| Mother‐in‐law lives nearby | 21 (42%) | |

| Mother lives nearby | 17 (32%) | |

| Household hunger b | ||

| Little to no hunger | 37 (74%) | |

| Moderate hunger | 13 (26%) | |

| Child still breastfeeding | 48 (96%) | |

| Complementary foods introduced | 49 (98%) | |

| Child fed animal‐source foods in previous 24 h | ||

| Dried or fresh fish | 20 (40%) | |

| Other meat | 2 (4%) | |

| Eggs | 1 (2%) | |

| Dairy | 9 (18%) | |

| Child met minimum diet diversity in previous 24 h | 10 (20%) | |

| Mean child dietary diversity score previous 24 h c | 2.7 | |

| Child fed sugary foods or drinks in previous week | 33 (62%) | |

| Child fed sugary foods or drinks in previous 24 h | 15 (30%) | |

Restricted to participants who completed all three TIPs visits.

Calculated from the Household Hunger Scale (Ballard et al., 2011).

Diet diversity score reflects number of food groups out of seven potential; four is minimum dietary diversity.

Visit 1 – Mothers' practices and beliefs. Based on the infant and young child feeding practices mothers reported, interviewers identified the following key feeding issues: children were commonly fed thin, watery porridge (88%); children's diets had limited diversity and rarely received animal‐source foods other than dagaa (small dried fish); (76%); children received sugary snacks and drinks (60%); responsive feeding was not practised (44%); and children were not fed as often as recommended for their age (40%).

Visit 1 – Fathers' focus group discussions. During FGDs, fathers were asked to describe how food influenced child health, growth and development (Table S2). When asked about the types of foods young children should eat, fathers frequently mentioned porridge and fruits. Some fathers mentioned groundnuts, soya beans, dagaa, and milk. A few mentioned eggs, other beans, and other fish. It was common for fathers to talk about a ‘balanced diet’; however, understanding around this concept appeared to be limited. The need for sugar and flour were reported by several fathers, as was the need for a variety of grains. For example, one participant said ‘my understanding of a balanced diet is the combination of different types of foods with nutrients enabling a child to grow healthy’, but when asked for specifics, he talked about porridge made with a mix of flours from different grains.

Participants described fathers' role in infant and young child care and feeding as providing food and other resources to mothers, who fathers described as being ultimately responsible for feeding infants and young children. While fathers described their role as providing resources, they noted that limited income and access to foods made it difficult to provide complementary foods. For example, dagaa is widely available, but it can be difficult to provide fruits and other animal‐source foods. One father mentioned that fathers' roles include monitoring women to ensure they prepare food for the child, saying, ‘It is necessary to follow up, because there are some women who are lazy. You might provide them with the foods but they won't prepare it unless you follow up’.

After the vignette, participants talked more about fathers' roles and the need to ensure that women were not overburdened. Several participants also explained that in order for a child to grow well and be healthy it was important for husbands and wives to cooperate. One father said, ‘What I see first is cooperation inside the family. Good communication and cooperation will build a strong family with a lot of love that will help a child grow up healthy’.

Fathers also talked about the role of grandparents, especially paternal grandmothers, other children, and neighbours in the care and feeding of infants and young children. Fathers reported wanting more information about infant and young child nutrition and that they value and trust nutrition information from health care providers and local leaders. Although not mentioned spontaneously, when asked directly, fathers agreed that religious leaders would be reliable sources of nutrition information (Table S2).

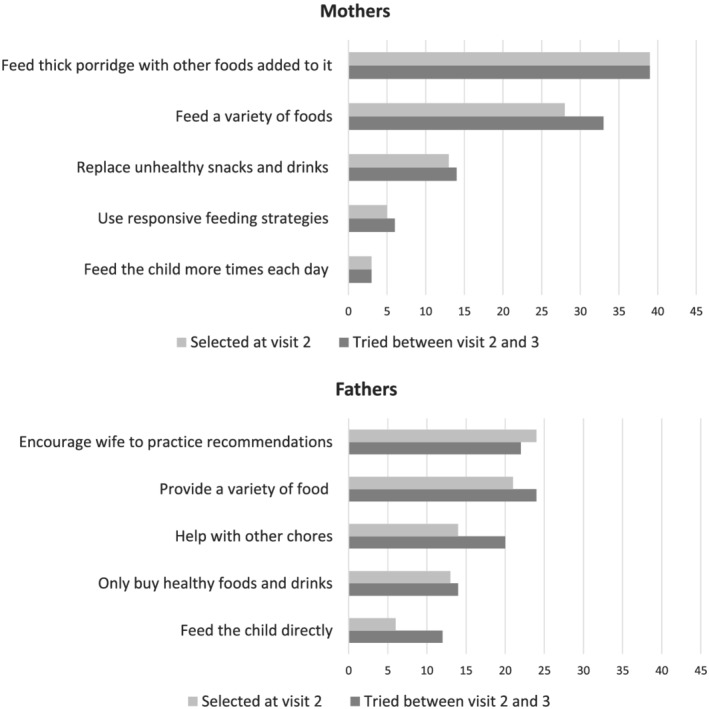

Visit 2 – Tailored counselling recommendations for mothers and fathers. At visit 2, interviewers provided up to five tailored recommendations (average 3) to mothers and fathers to improve complementary feeding practices. The types of recommendations presented to mothers and fathers differed. Mothers were counselled to modify or try new complementary feeding practices, whereas fathers were counselled both to increase support to mothers for complementary feeding, and to actively participate in child feeding. The practices mothers selected were typically related to what they fed the child. It was notable that while almost half of mothers were encouraged to try responsive feeding strategies, few selected them. Few women chose to try feeding children more often. All but one of the practices fathers selected were related to increasing support for complementary feeding through encouragement, buying or providing money for recommended foods, or helping with chores; only a few fathers chose to try feeding the child directly (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Recommendations to improve complementary feeding that mothers and fathers selected to try (visit 2) and reported trying (visit 3)

Visit 3 – Participants' experiences trying recommended practices. At visit 3, mothers and fathers were asked to report the practices they tried and the facilitators and barriers they experienced. The narrative below reports these details with key themes and illustrative quotes in Table 2. Several participants reported trying practices they had been counselled about but had not selected to try at visit 2.

TABLE 2.

Acceptability and feasibility of complementary feeding recommendations and father engagement

| Emergent themes | Illustrative quotes |

|---|---|

| Acceptability and feasibility of complementary feeding recommendations | |

| Giving thick porridge and family foods was acceptable to most mothers and fathers |

“Before we used to add a lot of water [to porridge], but nowadays we just add a little water. Also, he never ate any meat, but nowadays he eats meats and not only the broth.” – Father 27 years with son 9 months “I make nutritional porridge with maize, dagaa, ground nuts, beans, several things. The porridge is thick, because if you make it light, it is like nothing. A mother should make a thick porridge, fill the cup, and feed the child with a spoon.” – Mother 45 years with son 10 months |

| Avoiding sugary snacks and drinks was also acceptable to mothers and fathers |

“I liked that recommendation to stop giving sweets and biscuits because those things are harmful. Sweets and biscuits have too much sugar which is not good for the baby … My family members agreed and said it is not good to give the baby sweets and biscuits.” – Mother 27 years with son 17 months “I educated the family members not to give the baby biscuits. I educated them that the foods that we give the baby, for instance tinned juice, soda, and biscuits are not healthy for the child.” – Father 35 years with daughter 8 months |

| Mothers and fathers were motivated by changes they observed in their child |

“The first change I noticed is she has gained weight. When you look at her face, she looks beautiful, not like back then. Now she is glowing.” – Father 27 years with daughter 9 months “Since I started feeding him as you instructed me, the changes I see are he is becoming healthier and does not cry every now and then as he used to and he can play just fine.” – Mother 37 years with son 11 months |

| Those who fed their children responsively reported positive results |

“The thing I liked was that the child ate food that she did not usually eat. I felt so happy, amazed, because even when I do not have money I know that if I prepare this food for the child and sing to her, she will eat and like it. I have seen that when I feed her and praise and clap and show her that I am happy, it has helped her to eat all of the food that she is given.” – Mother 27 years with daughter 16 months “I tried being at home during meal times so that I could eat with my child and encourage him. I made it seem like a game and that he should like whatever he is eating.” – Father 28 years with son 10 months |

| Buying foods specifically for babies was a barrier for many families due to costs and availability |

“The difficulty is availability of green vegetables and being short of money to buy fruits. There would be no difficulty if there is no shortage of money to buy fruits and no scarcity of green vegetables.” – Mother 39 years with son 12 months “The difficulty was getting money to buy meat. Sometimes you do not get it.” – Father 47 years with son 13 months |

| Seasonal variation in income and food availability were prominent barriers |

“To be honest, I did not have vegetables. They were dry when I searched. I have searched for them now and have not found any.” – Mother 33 years with son 8 months “Incomes often decrease from September to December. Less income limits my ability to provide fish, milk, and dagaa, but I can manage to provide ugali and beans. Now we are selling small amounts of coffee and maize, so we can buy and provide these foods for the child. But, I doubt we will be able to in the future.” – Father 44 years with son 7 months |

| A few mothers reported challenges with feeding | “When I added an egg [to the thick porridge] and gave it to him, he vomited … I decided not to try eggs again … you know most people do not give their children eggs.” – Mother 38 years with son 16 months |

| Father support and spousal relationships | |

| Fathers supported complementary feeding, which mothers confirmed and appreciated | “My husband is supporting me in all aspects, especially with food … he is so close to the child. When he finds the child crying, he will hold him … he helps a lot. He is the one who buys food for the child and sometimes he feeds him … What I like most is that we are helping each other to bring up our child … Our child gets love from both parents.” – Mother 26 years with son 7 months |

| A few fathers reported feeding their children | “When they prepare the food for me, I invite him, he comes and we eat on the same plate together. I have been doing this almost every day since it was recommended to me. It makes me happy. At first he was not used to it, when I used to invite him he used to refuse until he got used to it. Others in my family are happy seeing me eating with my child. Some fathers may not want to try this because small children have a tendency of getting food on you and smothering you with food, but when they come to my house and see how I eat with my child, then they will learn from us. The child sees that he is not segregated and he also likes it. I will continue because the child will learn how to feed himself and he will feel loved by each parent.” – Father 27 years with son 9 months |

| Fathers reported helping with chores and caring for their children |

“I thought if she is doing all the chores, maybe she will not be able to prepare food for the child, so I decided to help [fetch firewood] … she was happy … She saw I was able to help her with something she never expected.” – Father 28 years with son 18 months “My wife said that I should continue playing with my child when I get home from work. Then when my wife is preparing the food, my child can eat happily.” – Father 24 years with son 10 months |

| Fathers talked about their relationships with their children | “From what I can see, they may think that maybe they are being disrespected by their wives. Because most fathers do not like to stay close to their children; if he is seated there he will either call or wait for the mother to come feed the baby porridge or ask a sibling to feed the baby porridge. But a kid cannot feed the baby porridge properly; it is the responsibility of an elder to feed the baby porridge. They can do this as it makes them happy being closer to their children since raising children is the responsibility of both father and mother and it should not be left for the mother to do it alone.” – Father 25 years with son 6 months |

| Fathers reported increased cooperation with their spouse | “I saw good results, because household tasks are to be done in collaboration. And my family members are very happy … they were happy since they saw us helping one another and even the other family members saw. It was good and even simplifying the work for her because you join together.” – Father 37 years with son 11 month |

| Fathers wanted to encourage others fathers to be involved | “Now I can tell my fellow fathers that for a baby to be healthy, we fathers should not leave our children only to their mothers. Wives and husbands have to work together as a family.” – Father 46 years with son 15 months |

| Fathers reported helping with chores, which was confirmed by a few mothers (couple analysis) |

“The father helps with drawing water and collecting firewood for me, so I can cook … when I go out for a bit, he feeds the baby porridge.” – Mother 33 years with son 9 months “Nowadays, fetching water is far, I was able to bring, and also firewood. I went and brought them because she is being with the baby at home so I should find those things … The thing that I like is that when I do this work, the baby gets his meal at a good time, mother gets to make special porridge. So I must continue doing this so the baby could get a good meal.” – Father 39 years with son 9 months |

Dietary recommendations were acceptable to most mothers and fathers, particularly providing thick porridge, adding other foods to porridge, and feeding family foods that were already available. However, giving animal‐source foods other than dagaa was challenging for most families. The high costs of recommended foods, especially animal‐source foods, was the most common barrier reported by fathers and mothers. Mothers also mentioned that eggs and vitamin A‐rich vegetables (e.g. leafy greens, carrots), and some fruits were not always readily available, while other mothers talked about purchasing eggs or using eggs from home. A few mothers reported that other family members discouraged giving eggs to young children, saying eggs were considered expensive or it was ‘just not done’. A few fathers talked about seasonal variation in income, which limited their ability to purchase recommended foods; seasonality also affected the availability of recommended foods. Replacing sugary snacks and drinks with healthy alternatives was widely acceptable among mothers and fathers, who frequently reported giving fruits instead of biscuits or other sweets. They also reported that their families agreed with this recommendation. Parents described feeling motivated to continue with new feeding practices because of perceived improvements in child temperament, health and appearance. Many described their children as happier and crying less after trying the recommended practices.

The few mothers and fathers who reported practicing responsive feeding at visit 3 described it positively. A few fathers reported playing with or telling stories to encourage their children to eat. In contrast, several mothers who had not tried these recommendations reported challenges with children refusing or spitting out food.

Most fathers reported enjoying more involvement in complementary feeding; a few reported that they prepared food or fed their children. Many fathers spontaneously reported improved communication and cooperation with their spouse. Most mothers reported they were pleased with the support they had received from fathers. While participants' responses around their relationships were mostly positive, one mother, whose husband did not participate in a third interview, described not receiving support:

I just raise and feed my child on my own. You know men are so hard to agree, if you tell them to carry a baby they will ask you why are you giving them a child? I cannot force him; I will just carry my child by myself … When you tell a father to provide money for buying things, he says he does not have any. Are you going to tie him up?

–Mother 30 years with daughter 8 months

Almost all mothers and fathers reported that other family members agreed with or supported the recommended practices they were trying. Several fathers and mothers reported sharing or planning to share the recommendations with others in their families and communities.

3.1. Couple analysis

Summaries were completed and analysed for all couples who had interviews at visit 3 (n = 38). Almost all couples described similar experiences trying new practices, which were generally positive. Couples who did not try a recommendation cited financial barriers, limited availability of recommended foods, or their child being sick. There was a high level of consistency within couples about fathers providing or buying food for the child. Almost all couples agreed that fathers purchased recommended foods for the child. While many fathers talked about the importance of spousal communication and cooperation, and talking with mothers about child feeding specifically, only about half of the couples agreed that they talked with their spouse about child feeding. Agreement among couples varied the most on topics related to fathers' nonfinancial support and involvement in complementary feeding. Among couples in which the father reported preparing or feeding their child recommended foods, mothers confirmed fathers' involvement in about half. The main difference within couples was how mothers and fathers described the amount of support the father provided, particularly help with other domestic tasks. Within most couples, fathers reported helping with domestic tasks (e.g. fetching water, taking grain to the mill, collecting firewood) so that mothers would have more time for child care and feeding, but less than half of couples had both mothers and fathers reporting this type of help. Mothers who reported increased father involvement reported appreciating it and wanting it to continue, whereas mothers who did not report increased support or father involvement expressed wanting their husbands to be more involved.

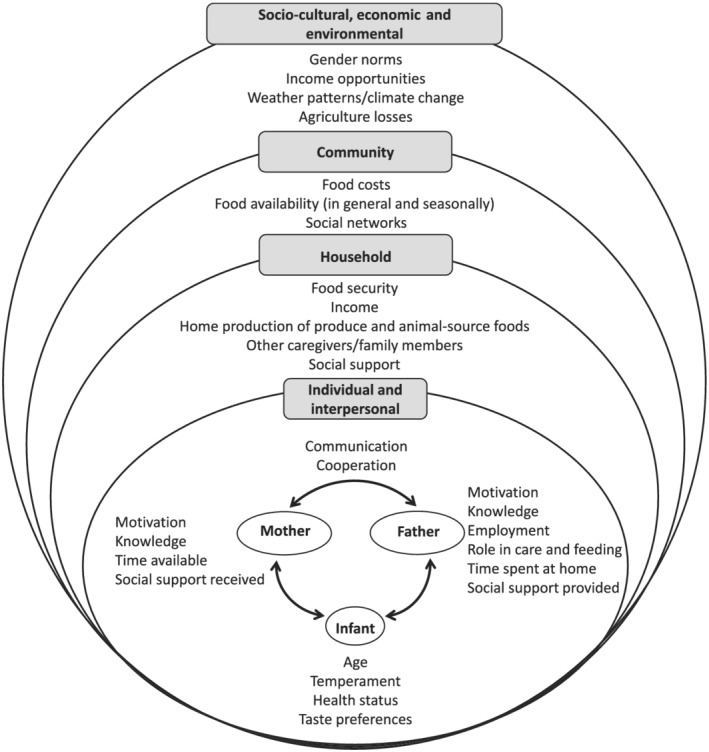

Through our analysis of data from mother and father TIPs visits 1–3, we identified a variety of factors that influenced parents' ability to practice complementary feeding recommendations. We summarised these factors, which have been described above, using a socioecological framework (Figure 2) (Jeong et al., 2018; McLeroy et al., 1988). Influential factors are organised by individual/interpersonal; household; community; and sociocultural, economic and environmental levels.

FIGURE 2.

Factors that influence complementary feeding practices

4. DISCUSSION

This formative research with mothers and fathers in the Lake Zone, Tanzania explored the acceptability and feasibility of (1) recommendations to improve complementary feeding practices, and (2) engaging fathers in complementary feeding. Dietary recommendations that could be carried out using existing resources, such as making porridge thicker and adding or feeding foods that were already available in the household were highly acceptable and feasible for parents. Recommendations that required families to purchase specific foods for infants and young children, while acceptable to mothers and fathers, were not always feasible for families due to resource constraints and seasonal availability. Similar to a TIPs study in Rwanda (Williams et al., 2019), it was difficult for parents to provide animal‐source foods and vitamin A‐rich fruits and vegetables. Limited financial resources and high food prices are well‐known barriers to optimal complementary feeding practices (Avula et al., 2013; Iannotti et al., 2012; Pelto & Armar‐Klemesu, 2015; Stewart et al., 2013). Fathers can play a role in accessing diverse foods, by providing money for food, purchasing food, or making decisions about whether livestock and produce are consumed or sold (Bilal, Dinant, et al., 2016; Nguyen et al., 2019; Sanghvi et al., 2014). Tailored counselling for fathers about providing nutritious foods is a promising strategy to increase young children's consumption of these food, especially foods for which fathers may already have responsibility for securing. However, additional financial and other resources may be needed to overcome financial and seasonal barriers to increase dietary diversity.

Despite responsive feeding being recommended to many families in our sample, few participants chose to try this recommendation. Yet those who did reported positive experiences. It is difficult to determine if the tendency not to select this practice resulted from resistance from participants, how it was recommended by interviewers, or other factors. Additional research is needed to more closely examine barriers and facilitators to responsive feeding. Given the positive experiences of the few participants who did try it, responsive feeding was one of the featured recommendations in ASTUTE community health worker training materials (IMA World Health, 2019).

It was very common for young children in this rural sample to receive energy‐dense, nutrient‐poor foods and beverages. This is similar to a study in Dar‐es‐Salaam, Tanzania, which found that consumption of sugar‐sweetened beverages and processed snacks and junk food is common (Pries et al., 2017). Rates of hypertension, overweight and obesity and risk factors for nutrition‐related noncommunicable diseases among adults in Mwanza, Tanzania, particularly in rural areas, has been increasing steadily (Nsanya et al., 2019). Even though rates of childhood overweight and obesity are relatively low, they will likely increase given trajectories in similar settings (Popkin et al., 2020). Appropriate complementary feeding is a ‘double‐duty action’ that can protect against stunting and may reduce the future risk of overweight and obesity (Hawkes et al., 2020; Pradeilles et al., 2018). Replacing biscuits and other sweets with healthier snacks was acceptable and feasible for mothers and fathers in this study, alongside recommendations to increase dietary diversity. In qualitative formative research in Egypt, parents were motivated to stop giving young children junk foods because of cost savings (Kavle et al., 2015). A TIPs study with mothers in Rwanda called for incorporating fathers, grandmothers, and other family members in interventions that promote ‘double‐duty actions’ (Williams et al., 2019). Future research should examine engaging fathers in SBCC activities to promote healthy feeding practices that address all forms of malnutrition. Additionally, future research – both in Tanzania and elsewhere – should focus on identifying motivating factors for greater paternal involvement in complementary feeding and whether appealing to such benefits as feeling more connected to children, improved communication, greater cooperation with spouses actually encourage men to take a greater part in complementary feeding.

In this setting where traditional gender norms hold mothers responsible for infant and young child care and feeding, fathers were generally positive about their increased involvement in complementary feeding, and most mothers who confirmed their reports appreciated the increased support. This finding is consistent with findings from a mixed‐methods systematic review of interventions that engaged fathers in maternal and child nutrition (Martin et al., 2020). Several fathers also described being more involved in domestic tasks and child care, which has been reported in maternal and child health program engaging fathers in Rwanda (Doyle et al., 2014). In addition to the nutritional benefits for children, engaging fathers in IYCF can also lead to fathers feeling closer to their children (Engle, 1997). Many fathers in this formative research described feeling more connected to their children because of their increased involvement in child care and feeding, particularly those who practiced responsive feeding. Almost all fathers reported improved communication and cooperation with their spouses, which many mothers also reported. Several studies that have engaged fathers in IYCF or maternal and child health have presented similar findings (Bezner Kerr, Chilanga, et al., 2016; Doyle et al., 2014; Martin et al., 2020). This research explored the acceptability of increasing fathers' support for recommended complementary feeding practices and becoming more involved in infant care and feeding given current gender norms. Although uptake of practices involving direct feeding was limited, TIPs enables the exploration of what may be acceptable, and thus represent first steps toward more equitable engagement in child feeding in these very traditional, patriarchal communities. Future research is needed to examine the potential for gender transformative interventions to achieve more gender equitable outcomes related to complementary feeding practices.

While there are many potential benefits of engaging fathers, involving them is not without risk as it can lead to abuse and drain financial resources (Engle, 1997) or limit women's decision‐making power (Yourkavitch et al., 2017). It is critical to conduct formative research to examine the contextual appropriateness of engaging fathers before involving them in programs (MacDonald et al., 2020; Yourkavitch et al., 2017). Further, collecting related monitoring data during a program can help identify any unintended consequences (Martin et al., 2020). While few mothers in this formative research reported their husbands did not provide support or become involved in complementary feeding, none described negative experiences or controlling behaviour from their husbands during TIPs. However, occasional negative experiences have been reported in previous infant feeding research that engaged fathers (Sahip & Turan, 2007). Gender transformative activities, based on formative research, may help prevent negative consequences by facilitating reflection on gender norms and relationship dynamics within families (Doyle et al., 2014; Dworkin et al., 2015).

This study examined mothers' and fathers' responses to tailored recommendations through interpersonal communication. ASTUTE used the findings to develop participatory training materials for community health workers to counsel families about dietary diversity, feeding animal‐source foods, responsive feeding and healthy snacks (IMA World Health, 2019). Reaching mothers and fathers through home visits has been used elsewhere (Bilal, Spigt, et al., 2016; Salasibew et al., 2019). Other approaches to engage fathers in complementary feeding or maternal and child nutrition broadly, include counselling couples together at health facilities (Dinga et al., 2018), community‐based fathers' groups (Mukuria et al., 2016), and support groups that bring family members together with other families (Bezner Kerr, Lupafya, et al., 2016; DeLorme et al., 2018). Large‐scale IYCF programs that have reported improved complementary feeding practices also reached fathers through community mobilization or mass media activities as part of multilevel, multicomponent SBCC interventions (Menon et al., 2016; Sanghvi et al., 2017).

4.1. Strengths and limitations

Including fathers in TIPs was a strength of this research. A review of the literature did not reveal other TIPs complementary feeding research that had included fathers, despite fathers' influence being well documented. However, challenges in retaining fathers resulted in less data for fathers at visit 3. A limitation of this research was that it did not include other family members, namely grandmothers, who influence complementary feeding practices and often feed and care for infants and young children (Aubel, 2012; Bezner Kerr et al., 2008; Kinabo et al., 2017). Future formative research should use a family systems framework that includes mothers, fathers, grandmothers and other influential family members to identify acceptable and feasible recommendations for families (MacDonald et al., 2020).

Another strength of this research was analysis of transcripts in multiple groupings, to identify patterns within all mothers, all fathers and then within and among couples. The couple analysis found inconsistencies in mothers' and fathers' reports of father involvement in child care and feeding and highlighted discrepancies such as fathers reporting more participation in domestic tasks than was perceived and reported by mothers. Interviewing couples separately allowed us to examine the individual experience of each mother and father and enabled data triangulation. This enhanced our understanding of participant experiences, but complicates data analysis (Hertz, 1995; Valentine, 1999). How couples are interviewed (i.e. separately or together) influences how they describe their experiences and relationship (Hertz, 1995; Valentine, 1999), and differences in their accounts are expected (Hertz, 1995; Iphofen et al., 2019). It is possible that while fathers perceived they were doing more domestic tasks than they had done previously, it was not substantial enough to alter mothers' perceptions of their own workload or that social desirability bias led fathers to respond as they thought interviewers wanted. If couples were interviewed together these inconsistencies could have been explored but, given gendered relationship dynamics, it is possible they would not have been reported or could increase risk of discord in the family. Despite the complexity this method introduced, it provided useful information about mothers' and fathers' perspectives and experiences.

This purposeful sample allowed in‐depth exploration of mothers' and fathers' experiences with recommendations to improve complementary feeding and increase father involvement, but was not designed to assess the impact of tailored counselling on feeding practices. It also prevents exploration of regional and seasonal differences, limiting generalizability beyond the Lake Zone. The short time frame is useful for intervention design, but is insufficient for evaluating sustained changes in complementary feeding practices and support. Relying on community health workers to recruit participants could have led to bias toward participants that the community health workers already knew and perceived to be approachable or likely to adopt new practices. There are risks of social desirability bias inherent in TIPs, as the interviewers recommended the new practices to try. To address this, interviewers repeatedly let participants know that they were interested in learning about barriers participants faced and any recommendations that families were not able to try. Our findings should be interpreted in the context of these limitations. While we cannot claim generalizability, results fit patterns found in other settings and the study design allowed in‐depth exploration of mothers and fathers experiences trying recommended practices, which is critical for designing social and behaviour change interventions. The short‐term nature of this research, like all formative research and TIPs studies, does not detract from its usefulness for informing interventions and programs. Our findings highlight the importance of including fathers in formative research.

5. CONCLUSIONS

Complementary feeding recommendations that did not require additional expenditures were widely acceptable and feasible for families. Even in these settings where traditional gender norms are common, fathers enjoyed becoming more involved in complementary feeding. This research identified and tested the acceptability of specific ways to engage fathers in complementary feeding, including buying recommended foods, caring for and feeding children and helping with household chores. Parents' limited selection of responsive feeding practices suggests the need to further explore norms and barriers, given that positive experiences were reported by parents who tried these behaviours. Improved couple communication and cooperation were commonly reported, suggesting that inclusion of fathers in complementary feeding SBCC efforts may be a feasible starting point for addressing inequitable gender norms and women's workload. This research highlights the importance of collecting data from fathers and inviting them to provide input and reflect on their experiences in dialogue with mothers, particularly during formative research to inform recommendations and interventions. Additional research is needed to inform the promotion of responsive feeding and to rigorously evaluate the impact of engaging fathers in complementary feeding. Increasing fathers' support for and involvement in complementary feeding has the potential to improve intrahousehold allocation of resources and lessen women's workload. Additional programmatic strategies are needed to address economic and seasonal barriers to providing diverse diets and to transform norms and attitudes underlying gendered roles related to complementary feeding.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

CONTRIBUTIONS

KLD conceptualised this research, KAD, KLD, RAK, SLM, CRM, LN and RBK contributed to study design and implementation. RAK, AK, CRM and IO collected data. SLM, MK, KHL and IO analysed the data. SLM drafted the paper. All authors participated in peer debriefings as part of data analysis, contributed to critically revising the article and approve the final version of the manuscript.

Supporting information

Table S1. TIPs data collection visits and content

Table S2. Key themes from focus group discussions with fathers

Data S1. Supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We appreciate the support from the Government of Tanzania, through the Ministry of Health Community Development, Gender, Elderly and Children. We are grateful to the mothers and fathers in the Lake Zone regions for sharing their experiences with us. We thank Gina Chapleau Klemm, Research Coordinator (Cornell University) and the data collectors Alindwa Bandio, Winfrenda Edward, Prosper Ganyala, Vivian Herbert Illembo, Emmanuel Massawe and Nyamizi Njile. Luiza Chepkemoi and Hiwet Tzehaie (Cornell University), and Kenley Richardson and Kari Riggle (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill) contributed to qualitative data analysis. Stephanie Martin received support from NICHD of the National Institutes of Health under award number P2C HD050924. This work was funded by UK Aid from the UK government, through the Addressing Stunting in Tanzania Early (ASTUTE) program.

Martin SL, Matare CR, Kayanda RA, et al. Engaging fathers to improve complementary feeding is acceptable and feasible in the Lake Zone, Tanzania. Matern Child Nutr. 2021;17:e13144. 10.1111/mcn.13144

Funding information UK AID

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author after receiving approval from the Tanzania Food and Nutrition Centre.

RERERENCES

- Aubel, J. (2012). The role and influence of grandmothers on child nutrition: Culturally designated advisors and caregivers. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 8(1), 19–35. 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2011.00333.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avula, R. , Menon, P. , Saha, K. K. , Bhuiyan, M. I. , Chowdhury, A. S. , Siraj, S. , … Frongillo, E. A. (2013). A program impact pathway analysis identifies critical steps in the implementation and utilization of a behavior change communication intervention promoting infant and child feeding practices in Bangladesh. Journal of Nutrition, 143(12), 2029–2037. 10.3945/jn.113.179085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballard, T. , Coates, J. , Swindale, A. , & Deitchler, M. (2011). Household hunger scale: Indicator definition and measurement guide. Washington, DC: Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance II Project, FHI 360. https://www.fantaproject.org/monitoring‐and‐evaluation/household‐hunger‐scale‐hhs [Google Scholar]

- Bentley, M. E. , Johnson, S. L. , Wasser, H. , Creed‐Kanashiro, H. , Shroff, M. , Rao, S. F. , & Cunningham, M. (2014). Formative research methods for designing culturally appropriate, integrated child nutrition and development interventions: An overview. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1,308(1), 54–67. 10.1111/nyas.12290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezner Kerr, R. , Chilanga, E. , Nyantakyi‐Frimpong, H. , Luginaah, I. , & Lupafya, E. (2016). Integrated agriculture programs to address malnutrition in northern Malawi. BMC Public Health, 16(1197), 1197. 10.1186/s12889-016-3840-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezner Kerr, R. , Dakishoni, L. , Shumba, L. , Msachi, R. , & Chirwa, M. (2008). “We Grandmothers Know Plenty”: Breastfeeding, complementary feeding and the multifaceted role of grandmothers in Malawi. Social Science and Medicine, 66(5), 1,095–1,105. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.11.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezner Kerr, R. , Lupafya, E. , Shumba, L. , Dakishoni, L. , Msachi, R. , Chitaya, A. , … Maona, E. (2016). “Doing Jenda Deliberately” in a participatory agriculture and nutrition project in Malawi. In Njuku J., Kaler A., & Parkins J. (Eds.), Transforming gender and food security in the global south (pp. 241–259). London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bhutta, Z. A. , Das, J. K. , Rizvi, A. , Gaffey, M. F. , Walker, N. , Horton, S. , … Black, R. E. (2013). Evidence‐based interventions for improvement of maternal and child nutrition: What can be done and at what cost? The Lancet, 382(9890), 452–477. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60996-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilal, S. M. , Dinant, G. , Blanco, R. , Crutzen, R. , Mulugeta, A. , & Spigt, M. (2016). The influence of father's child feeding knowledge and practices on children's dietary diversity: A study in urban and rural districts of Northern Ethiopia, 2013. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 12(3), 473–483. 10.1111/mcn.12157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilal, S. M. , Spigt, M. , Czabanowska, K. , Mulugeta, A. , Blanco, R. , & Dinant, G. (2016). Fathers' perception, practice, and challenges in young child care and feeding in Ethiopia. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 37(3), 329–339. 10.1177/0379572116654027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeCuir‐Gunby, J. T. , Marshall, P. L. , & McCulloch, A. W. (2010). Developing and using a codebook for the analysis of interview data: An example from a professional development research project. Field Methods, 23(2), 136–155. 10.1177/1525822X10388468 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DeLorme, A. L. , Gavenus, E. R. , Salmen, C. R. , Benard, G. O. , Mattah, B. , Bukusi, E. , & Fiorella, K. J. (2018). Nourishing networks: A social‐ecological analysis of a network intervention for improving household nutrition in Western Kenya. Social Science and Medicine, 197, 95–103. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.11.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickin, K. L. , Griffiths, M. , & Piwoz, E. G. (1997). Designing by dialogue: A program planners' guide to consultative research for improving young child feeding. Washington DC; USA: Academy for Educational Development. https://www.manoffgroup.com/wp‐content/uploads/Designing‐by‐Dialogue.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Dickin, K. L. , & Seim, G. (2013). Adapting the trials of improved practices (TIPs) approach to explore the acceptability and feasibility of nutrition and parenting recommendations: What works for low‐income families? Maternal & Child Nutrition, 11(4), 897–914. 10.1111/mcn.12078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinga, L. A. , Kiage, B. , & Kyallo, F. (2018). Effect of paternal education about complementary feeding of infants in Kisumu County, Kenya. African Journal of Food, Agriculture, Nutrition and Development, 18(3), 13,702–13,716. 10.18697/ajfand.83.17490 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Downs, S. M. , Sackey, J. , Kalaj, J. , Smith, S. , & Fanzo, J. (2019). An mHealth voice messaging intervention to improve infant and young child feeding practices in Senegal. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 15(4), e12825. 10.1111/mcn.12825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle, K. , Kato‐Wallace, J. , Kazimbaya, S. , & Barker, G. (2014). Transforming gender roles in domestic and caregiving work: Preliminary findings from engaging fathers in maternal, newborn, and child health in Rwanda. Gender and Development, 22(3), 515–531. 10.1080/13552074.2014.963326 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin, S. L. , Fleming, P. J. , & Colvin, C. J. (2015). The promises and limitations of gender‐transformative health programming with men: Critical reflections from the field. Culture, Health and Sexuality, 17, 128–143. 10.1080/13691058.2015.1035751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engle, P. L. (1997). The role of men in families: Achieving gender equity and supporting children. Gender and Development, 5(2), 31–40. 10.1080/741922351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engle, P. L. , Menon, P. , & Haddad, L. (1999). Care and nutrition: Concepts and measurement. World Development, 27(8), 1,309–1,337. 10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fabrizio, C. S. , van Liere, M. , & Pelto, G. (2014). Identifying determinants of effective complementary feeding behaviour change interventions in developing countries. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 10(4), 575–592. 10.1111/mcn.12119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gourlay, A. , Mshana, G. , Birdthistle, I. , Bulugu, G. , Zaba, B. , & Urassa, M. (2014). Using vignettes in qualitative research to explore barriers and facilitating factors to the uptake of prevention of mother‐to‐child transmission services in rural Tanzania: A critical analysis. BMC medical research methodology, 14(1), 1–11. 10.1186/1471-2288-14-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagaman, A. K. , & Wutich, A. (2017). How many interviews are enough to identify metathemes in multisited and cross‐cultural research? Another perspective on Guest, Bunce, and Johnson's (2006) landmark study. Field Methods, 29(1), 23–41. 10.1177/1525822X16640447 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, S. A. , Olórtegui, M. P. , Leontsini, E. , Asayag, C. R. , Scott, K. , & Winch, P. J. (2013). Trials of improved practices (TIPs): A strategy for making long‐lasting nets last longer? American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 88(6), 1,109–1,115. 10.4269/ajtmh.12-0641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkes, C. , Ruel, M. T. , Salm, L. , Sinclair, B. , & Branca, F. (2020). Double‐duty actions: Seizing programme and policy opportunities to address malnutrition in all its forms. The Lancet, 395(10218), 142–155. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32506-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertz, R. (1995). Separate but simultaneous interviewing of husbands and wives: Making sense of their stories. Qualitative Inquiry, 1(4), 429–451. 10.1177/107780049500100404 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoddinott, J. , Ahmed, A. , Karachiwalla, N. I. , & Roy, S. (2018). Nutrition behaviour change communication causes sustained effects on IYCN knowledge in two cluster‐randomised trials in Bangladesh. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 14(1), 1–10. 10.1111/mcn.12498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iannotti, L. L. , Robles, M. , Pachón, H. , & Chiarella, C. (2012). Food prices and poverty negatively affect micronutrient intakes in Guatemala. The Journal of Nutrition, 142(8), 1,568–1,576. 10.3945/jn.111.157321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IMA World Health . (2019). Community health worker training dialogues for counselling on complementary feeding. Dar es Salaam. https://astute.imaworldhealth.org/sites/default/files/toolkits/Community%20health%20worker%20(CHW)%20training%20dialogues%20for%20counselling%20on%20complementary%20feeding.pdf

- IMA World Health . (2020). ASTUTE tooklit. Retrieved July 10, 2020, from https://astute.imaworldhealth.org/astute‐CHW

- Iphofen, R. , Tolich, M. , & Lowton, K. (2019). He said, she said, we said: Ethical issues in conducting dyadic interviews. In The SAGE handbook of qualitative research ethics (pp. 133–146). 10.4135/9781526435446.n9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jaacks, L. M. , Kavle, J. , Perry, A. , & Nyaku, A. (2017). Programming maternal and child overweight and obesity in the context of undernutrition: Current evidence and key considerations for low‐ and middle‐income countries. Public Health Nutrition, 20(7), 1,286–1,296. 10.1017/S1368980016003323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, J. , Siyal, S. , Fink, G. , McCoy, D. C. , & Yousafzai, A. K. (2018). “His mind will work better with both of us”: A qualitative study on fathers' roles and coparenting of young children in rural Pakistan. BMC Public Health, 18(1), 1–16. 10.1186/s12889-018-6143-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavle, J. A. , Mehanna, S. , Saleh, G. , Fouad, M. A. , Ramzy, M. , Hamed, D. , … Galloway, R. (2015). Exploring why junk foods are “essential” foods and how culturally tailored recommendations improved feeding in Egyptian children. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 11(3), 346–370. 10.1111/mcn.12165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinabo, J. , Mwanri, A. W. , Mamiro, P. , Bundala, N. , Picado, J. , Kulwa, K. , … Cheung, E. (2017). Infant and young child feeding practices on Unguja Island in Zanzibar, Tanzania: A ProPAN based analysis. Tanzania Journal of Health Research, 19(3), 1–9. 10.4314/thrb.v19i3.5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald, C. A. , Aubel, J. , Aidam, B. A. , & Girard, A. W. (2020). Grandmothers as change agents: Developing a culturally appropriate program to improve maternal and child nutrition in Sierra Leone. Current Developments in Nutrition, 4(1), 1–9. 10.1093/cdn/nzz141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macqueen, K. M. , Mclellan, E. , Kay, K. , & Milstein, B. (1996). Codebook development for team‐based qualitative analysis. CAM Journal, 10(2), 31–36. 10.1177/1525822X980100020301 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Manji, A. (2000). “Her Name Is Kamundage”: Rethinking women and property among the Haya of Tanzania. Africa, 70(3), 482–500. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, S. L. , McCann, J. K. , Gascoigne, E. , Allotey, D. , Fundira, D. , & Dickin, K. L. (2020). Mixed‐methods systematic review of behavioral interventions in low‐ and middle‐income countries to increase family support for maternal, infant, and young child nutrition during the first 1,000 days. Current Developments in Nutrition, 4(6), 1–27. 10.1093/cdn/nzaa085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masele, E. J. (2020). Exploring gender relations in Sukuma oral poetry: A thematic comparative study. Kioo Cha Lugha, 17(1), 164–178. [Google Scholar]

- Matare, C. R. , Craig, H. C. , Martin, S. L. , Kayanda, R. A. , Chapleau, G. M. , Bezner Kerr, R. , … Dickin, K. L. (2019). Barriers and opportunities for improved exclusive breast‐feeding practices in Tanzania: Household trials with mothers and fathers. Food and Nutrition Bulletinnd nu, 40(3), 308–325. 10.1177/0379572119841961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeroy, K. R. , Bibeau, D. , Steckler, A. , & Glanz, K. (1988). An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Education and Behavior, 15, 351–377. 10.1177/109019818801500401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menon, P. , Nguyen, P. H. , Saha, K. K. , Khaled, A. , Sanghvi, T. , Baker, J. , … Rawat, R. (2016). Combining intensive counseling by frontline workers with a nationwide mass media campaign has large differential impacts on complementary feeding practices but not on child growth: results of a cluster‐randomized program evaluation in Bangladesh. Journal of Nutrition, 146(10), 2075–2084. 10.3945/jn.116.232314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaelsen, K. F. , Grummer‐Strawn, L. M. , & Begin, F. (2017). Emerging issues in complementary feeding: Global aspects. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 13, 1–7. 10.1111/mcn.12444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health Community Development Gender Elderly and Children (MOHCDGEC) [Tanzania Mainland] , Ministry of Health (MOH) [Zanzibar] , Tanzania Food and Nutrition Center, National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) , Office of the Chief Government Statistician [Zanzibar] (OCGS) , & UNICEF . (2019). Tanzania National Nutrition Survey using SMART methodology 2018. Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: MoHCDGEC, MoH, TFNC, NBS, OCGS, and UNICEF. https://www.unicef.org/tanzania/media/2141/file/Tanzania%20National%20Nutrition%20Survey%202018.pdf [Google Scholar]

- MoHCDGEC . (2015). Tanzania demographic and health survey and malaria indicator survey, 172–173. https://www.dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR321/FR321.pdf

- Mukuria, A. G. , Martin, S. L. , Egondi, T. , Bingham, A. , & Thuita, F. M. (2016). Role of social support in improving infant feeding practices in Western Kenya: A quasi‐experimental study. Global Health Science and Practice, 4(1), 55–72. 10.9745/GHSP-D-15-00197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, P. H. , Frongillo, E. A. , Kim, S. S. , Zongrone, A. A. , Jilani, A. , Tran, L. M. , … Menon, P. (2019). Information diffusion and social norms are associated with infant and young child feeding practices in Bangladesh. Journal of Nutrition, 149(11), 2034–2045. 10.1093/jn/nxz167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nsanya, M. K. , Kavishe, B. B. , Katende, D. , Mosha, N. , Hansen, C. , Nsubuga, R. N. , … Kapiga, S. (2019). Prevalence of high blood pressure and associated factors among adolescents and young people in Tanzania and Uganda. The Journal of Clinical Hypertension, 21(4), 470–478. 10.1111/jch.13502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochieng, J. , Afari‐sefa, V. , Lukumay, P. J. , & Dubois, T. (2017). Determinants of dietary diversity and the potential role of men in improving household nutrition in Tanzania. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 12(12), 1–18. 10.1371/journal.pone.0189022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelto, G. H. , & Armar‐Klemesu, M. (2015). Identifying interventions to help rural Kenyan mothers cope with food insecurity: Results of a focused ethnographic study. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 11(2015), 21–38. 10.1111/mcn.12244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popkin, B. M. , Corvalan, C. , & Grummer‐Strawn, L. M. (2020). Dynamics of the double burden of malnutrition and the changing nutrition reality. The Lancet, 395(10217), 65–74. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32497-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pradeilles, R. , Baye, K. , & Holdsworth, M. (2018). Addressing malnutrition in low‐ and middle‐income countries with double‐duty actions. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 78, 388–397. 10.1017/S0029665118002616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pries, A. M. , Huffman, S. L. , Champeny, M. , Benjamin, M. , Ndeye, A. , El, C. , … Foundation, M. G. (2017). Consumption of commercially produced snack foods and sugar‐sweetened beverages during the complementary feeding period in four African and Asian urban contexts. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 13(S2), 1–12. 10.1111/mcn.12412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahip, Y. , & Turan, J. M. (2007). Education for expectant fathers in workplaces in Turkey. Journal of Biosocial Science, 39(6), 843–860. 10.1017/s0021932007002088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salasibew, M. M. , Moss, C. , Ayana, G. , Kuche, D. , Eshetu, S. , & Dangour, A. D. (2019). The fidelity and dose of message delivery on infant and young child feeding practice and nutrition sensitive agriculture in Ethiopia: A qualitative study from the Sustainable Undernutrition Reduction in Ethiopia (SURE) programme. Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition, 38(1), 1–11. 10.1186/s41043-019-0187-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanghvi, T. , Martin, L. , Hajeebhoy, N. , Abrha, T. H. , Haque, R. , Thi, H. , … Roy, S. (2014). Strengthening systems to support mothers in infant and young child feeding at scale. Food & Nutrition Bulletin, 34(3), 156–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanghvi, T. , Seidel, R. , Baker, J. , & Jimerson, A. (2017). Using behavior change approaches to improve complementary feeding practices. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 13(S2), 1–11. 10.1111/mcn.12406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobal, J. (2001). Sample extensiveness in qualitative nutrition education research. Journal of Nutrition Education, 33(4), 184–192. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11953239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, C. P. , Iannotti, L. , Dewey, K. G. , Michaelsen, K. F. , & Onyango, A. W. (2013). Contextualising complementary feeding in a broader framework for stunting prevention. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 9(S2), 27–45. 10.1111/mcn.12088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thuita, F. M. , Martin, S. L. , Ndegwa, K. , Bingham, A. , & Mukuria, A. G. (2015). Engaging fathers and grandmothers to improve maternal and child dietary practices: Planning a community‐based study in Western Kenya. African Journal of Food, Agriculutre, Nutrition, and Development, 15(5), 10,386–10,405. 10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF . (2020). Improving young children's diets during the complementary feeding period. UNICEF Programming Guidance. New York: UNICEF. https://sites.unicef.org/nutrition/files/Complementary_Feeding_Guidance_2020_portrait_ltr_web2.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Valentine, G. (1999). Doing household research: interviewing couples together and apart. Area, 31(1), 67–74. 10.1111/j.1475-4762.1999.tb00172.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williams, P. A. , Schnefke, C. H. , Flax, V. L. , Nyirampeta, S. , Stobaugh, H. , Routte, J. , … Muth, M. K. (2019). Using trials of improved practices to identify practices to address the double burden of malnutrition among Rwandan children. Public Health Nutrition, 22(17), 3,175–3,186. 10.1017/S1368980019001551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . (2010). Indicators for assessing infant and young child feeding practices: Part 2 Measurement, Geneva: World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44306/9789241599290_eng.pdf?ua=1 [Google Scholar]

- Yourkavitch, J. M. , Alvey, J. L. , Prosnitz, D. M. , & Thomas, J. C. (2017). Engaging men to promote and support exclusive breastfeeding: A descriptive review of 28 projects in 20 low‐ and middle‐income countries from 2003 to 2013. Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition, 36(1), 1–10. 10.1186/s41043-017-0127-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. TIPs data collection visits and content

Table S2. Key themes from focus group discussions with fathers

Data S1. Supporting information

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author after receiving approval from the Tanzania Food and Nutrition Centre.