Abstract

Grandmothers and fathers are key influencers of maternal and child nutrition and are increasingly included in interventions. Yet, there is limited research exploring their experiences participating in interventions. This study reports on findings from a qualitative process evaluation of a quasi‐experimental study that we conducted with grandmother and father peer dialogue groups to support maternal, infant and young child feeding practices in western Kenya. The aim was to explore grandmother and father experiences participating in interventions and how participation influences care and feeding practices. Grandmother and father peer educators received training to facilitate discussions about maternal and child nutrition, HIV and infant feeding, family communication, and family members' roles. Father peer educators also received training on gender inequities and power dynamics. In the original quasi‐experimental study, the intervention was associated with increased social support and improvements in some complementary feeding practices. The process evaluation explored participants' experiences and how participation influenced infant care and feeding practices. We used Atlas.ti to thematically analyse data from 18 focus group discussions. The focus group discussions revealed that grandmothers and fathers valued their groups, the topics discussed and what they learned. Grandmothers reported improved infant feeding and hygiene practices, and fathers reported increased involvement in child care and feeding and helping with household tasks. Both described improved relationships with daughters‐in‐law or wives. This study highlights the importance of engaging influential family members to support child nutrition and identifies factors to build cohesion among group members, by building on grandmothers' roles as advisors and expanding fathers' roles in nutrition through gender transformative activities.

Keywords: child nutrition, fathers, grandmothers, infant feeding, peer education, process evaluation, social networks

Key messages.

Dialogue groups are important vehicles for building social capital and engaging fathers and grandmothers to foster behaviour change and should include active participation, critical reflection and joint problem solving.

There are different and unique ways of effectively engaging fathers and grandmothers that are influenced by their cultural roles that can be identified during formative research.

Fathers can become more involved in infant and young child care and feeding even though it may be counter to traditional gender norms; grandmothers can improve complementary feeding practices.

Both fathers and grandmothers improved relationships, and communications with mothers can be attributed to their participation in dialogue groups.

Future interventions can consider broadening the engagement to include the family (mothers, fathers and grandmothers) together in addition to individual groups, as well as integrating income generating or savings and loan activities to promote group sustainability.

1. INTRODUCTION

Community‐based behaviour change interventions contribute significantly to improved maternal and child nutrition (Janmohamed et al., 2020; Qar et al., 2013). Scaling up community‐based programmes has the potential to reduce malnutrition‐related morbidity and mortality (Black, Allen, et al., 2013). Improvement in nutritional status is normally preceded by modification of practices, attitudes and acquisition of new knowledge. However, very few studies have investigated and documented the pathway of transformation from the participants' perspectives (Gillespie & van den Bold, 2017). Exploration of the experiences of the participants can elucidate the process that resulted in the outcomes observed (Nisbett et al., 2017). In order to formulate more effective context‐specific interventions aimed at curbing malnutrition, it is important to not only evaluate impact but also examine participants' experiences (Gram et al., 2019). Understanding these experiences and not just looking at impact can provide information and strategies to strengthen future interventions to become even more effective and sustainable.

Worldwide, almost half of all childhood deaths are attributed to malnutrition (Black, Victora, et al., 2013). Inappropriate infant and young child feeding (IYCF) practices contribute to growth faltering, undernutrition and suboptimal child development (Bhutta et al., 2013). Kenya is one of the 36 countries that contributes to 90% of the world's stunted children (Black et al., 2008). At the initiation of this study, 35.3% of children under 5 were stunted (Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS) & ICF Macro, 2010), an indicator of prolonged consumption of diets of insufficient quantity and quality and recurrent infections. The level of stunting was highest at 18–23 months (45.7%), potentially due to poor IYCF practices. The prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding among infants 0–5 months was also low (32%). In addition, only 38.5% of children 6–23 months were fed as recommended (i.e., continued breastfeeding while consuming a diverse diet with age appropriate meal frequency). The nutrition situation was further exacerbated by high micronutrient deficiencies in mothers and children, specifically iron and zinc (KNBS, MOPHS, & KEMRI, 2013). In order to reverse this situation, several strategies were adopted by the government including use of community‐based platforms. Evidence has shown that community engagement through a mix of behaviour change techniques (BCTs) increases degree of success and level of uptake of maternal, infant and young child nutrition (MIYCN) interventions (Qar et al., 2013; Webb Girard et al., 2020).

A key component of the Kenya national strategy to improve IYCF through community engagement is the use of mother‐to‐mother support groups (MTMSGs) (Ministry of Health, 2016). Typically, MTMSGs comprise mothers of children under 2 years and may include pregnant women. These groups are mostly embedded within the community health units, which are linked to a health facility. These peer support groups act as platforms for the provision of nutritional education and support with a trained member being a role model of recommended IYCF practices. Research has shown that this interaction that affords mothers a forum to share experiences is effective in improving breastfeeding practices (Bhutta et al., 2008; Lewycka et al., 2013). Although MTMSGs equip mothers with correct knowledge and peer support, translation into actual practices in the home setting may be challenged by influential family members.

Similar to studies in other contexts, our previous formative research revealed that mothers' IYCF decisions are influenced by fathers and grandmothers (USAID's Infant & Young Child Nutrition Project [IYCN], 2011, Thuita et al., 2015). It has been demonstrated that equipping these influencers with the correct MIYCN knowledge and skills enhances better nutrition related choices and practices at the family level (Aubel et al., 2004; Karmacharya et al., 2017; Pisacane et al., 2005; Wolfberg et al., 2004). However, most of these studies focus on the role of the influencers on breastfeeding practices of children aged 0–6 months (Martin et al., 2020). There is less information about interventions to engage family members in maternal nutrition and complementary feeding for children aged 6–24 months. In addition, there is little documentation of the experiences of family members as they participate in these interventions. We implemented a public health intervention aimed at engaging fathers and grandmothers to support MIYCN. The intervention was based on a socioecological framework, particularly the individual, family, and community levels, and social support constructs. To inform the design of the intervention, we first conducted formative research to explore the roles of fathers and grandmothers in MIYCN (IYCN, 2011; Thuita et al., 2015). Similar to many settings around the world, we found that men are primarily responsible for providing food or money to purchase foods and are typically not directly involved in the care and feeding of children younger than 2 years but expressed an interest in learning more and becoming involved. Grandmothers generally play a supportive role, offering advice related to child care and feeding and also directly care for and feed young children. We used separate father and grandmother peer‐led dialogue groups, based on adult learning principles, that were highly participatory and encouraged experience sharing, reflection, and problem solving to improve health and nutrition. Father and grandmother peer educators were trained to facilitate discussion groups on topics specific to their roles. For grandmothers, this meant building on their roles to support recommended practices and for fathers this included integrating gender transformative content and activities along with MIYCN (IYCN 2011b, 2011a).

The intervention was nestled in a multiphased and multimethod study that included (i) a quasi‐experimental study assessing changes in mothers' complementary feeding practices and fathers and grandmothers' support as a result of the intervention (Mukuria et al., 2016), (ii) in‐depth interviews with dialogue group peer educators to understand their motivation (Martin et al., 2015), and (iii) the current study, a qualitative process evaluation that explores the experiences of fathers and grandmothers who participated in dialogue groups and how their participation influenced infant and young child care and feeding practices and social support. Process evaluations can examine the mechanisms that produce positive change, explain intervention results and advance our understanding of interventions (Linnan & Steckler, 2002), as well as strengthen programme design, delivery and utilization (Nielsen et al., 2018).

2. METHODS

2.1. Overview of the primary study

The primary study employed a quasi‐experimental design, comprising three study arms (Mukuria et al., 2016). Two arms were designated for the intervention (one for fathers and another for grandmothers), whereas the third was a comparison arm. The study was conducted in three sublocations in Western province (Thuita et al., 2015). The study areas were purposively selected based on presence of a community health unit and social, cultural, economic and livelihoods homogeneity. The intervention sites were in Vigulu sublocation, Vihiga district for grandmothers and Kitagwa sublocation, Hamisi district for fathers. In order to avoid inadvertent spill‐over from the intervention groups, a sufficiently distant comparison site, Mambai sublocation in Emuhaya district, was selected. Fathers and grandmothers with children 6–9 months of age were invited to participate in dialogue groups, and participant characteristics have been previously reported (Martin et al., 2015).

The father and grandmother dialogue groups were facilitated by peer educators assisted by community health workers. The peer educators were selected by their group members and underwent a 5‐day training on dialogue group facilitation, family communication, interpersonal relationships and MIYCN (Martin et al., 2015). The peer educators in‐turn used these skills and their experience to facilitate dialogue groups bimonthly for 6 months at times and venues agreed upon by group members. They used discussion guides with key messages: IYCF practices, family support to pregnant and breastfeeding mothers, food preparation and safety, utilization of maternal and child health services, maternal nutrition, communication and prevention of mother‐to‐child transmission of HIV (Mukuria et al., 2016). Fathers' groups also discussed gender norms and roles of men as joint custodians of family health and nutrition. The intervention employed several BCTs (Michie et al., 2013) to restructure the social environment of mothers and families through engaging grandmothers or fathers to improve MIYCN (Table S1). Results from the quasi‐experimental study found significant increases in support mothers received from fathers and grandmothers in the intervention areas as well as improvements in minimum meal frequency, feeding animal source foods, and improved food consistency (Mukuria et al., 2016).

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Kenyatta National Hospital/University of Nairobi Ethics Review Committee and the PATH Research Ethics Committee. Written informed consent was obtained from participants. Informed consent forms were written in English and translated to Swahili and Luhya to ensure study participants understood.

2.2. Overview of the current study

In order to explore grandmothers' and fathers' experiences participating in dialogue groups and how their participation influenced infant and young child care and feeding practices, a process evaluation was undertaken over a period of 12 days between the fifth and sixth months of the primary study (May to June 2012) in the intervention groups only. To better understand participants' experiences with dialogue groups, the process evaluation was conducted near the end of the intervention. We conducted focus group discussions (FGDs) with each dialogue group; eight father dialogue groups with nine to 11 members and 10 grandmother groups comprising seven to 11 members each. FGDs were facilitated by experienced and trained qualitative research assistants who were trained for 3 days by the first author who is a senior researcher. The pretesting of discussion guides and field training of team was conducted in 1 day. Fathers FGDs were conducted by male facilitators, whereas female research assistants facilitated the grandmother groups. All of the facilitators spoke the local language. In‐depth discussions and extensive probing techniques were utilized by the facilitators. Discussions were audio recorded and later transcribed, in addition to extensive notes taken by the recorders. The study team prepared a FGD guide to examine father's and grandmother's experiences participating in peer dialogue groups (Table S1). The topics included dialogue group characteristics, group members' participation, dialogue group topics and facilitation, group satisfaction, reactions and changes at the individual and family level, the group's influence on the community, and the potential for sustainability (Table S1).

2.2.1. Data collection

In order to ensure quality data were collected, research assistants were trained on the FGD guides, facilitation techniques and data collection by two of the authors who are experienced qualitative researchers. The study team pretested the guides before data collection began. Participants from each dialogue group were then invited to participate in the FGDs. As participants had already provided written consent for the overall study, verbal consent was obtained from all members for participation in and audio recording of the FGD. The trained research assistants facilitated the FGDs in Swahili or Luyha, the local language, based on participant preference. The FGDs lasted between 1 and 2 h.

All FGDs were audio recorded, and two note takers took extensive notes during each discussion. The proceedings were translated into English. Daily debriefing meetings were held with the data collection teams to provide feedback on facilitation techniques and notetaking.

2.2.2. Data analysis

The initial data analysis was conducted immediately following data collection, and the results were summarized. For this analysis, the data were analysed afresh, with FGD transcripts analysed thematically, based on principles of grounded theory (Corbin & Strauss, 2008). This allows the data to determine coding using an emic/inductive approach, rather than coding being imposed externally etic approach. The code book was revised continually throughout the data analysis process. During the first round of coding, two analysts independently read and manually coded the same three transcripts to develop a draft codebook with a third analyst. The analysis team met frequently to discuss and revise the codebook. On the basis of the line‐by‐line reviews of coded transcripts and extensive discussions of coding decisions, we determined the level of agreement between coders to be high and no longer necessitated double coding. FGDs were entered into Atlas.ti Version 8 (Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin, Germany). The three analysts met weekly to discuss the coding process, update the codebook as needed, and change previously coded transcripts. Key findings for each code were summarized in data matrices sorted by fathers and grandmothers to examine similarities and differences among them; data matrices also included illustrative quotes. Codes were then reviewed and grouped into themes and discussed among the analysis team. Findings were shared and discussed with the entire study team and compared with the results from the initial analysis.

3. RESULTS

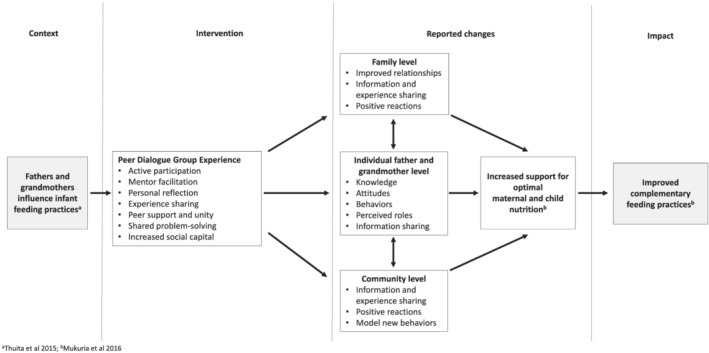

The results from this analysis were used to create a conceptual framework describing participants' experiences engaging in dialogue groups and how it influenced fathers and grandfathers, their family relationships, and community interactions (Figure 1). First, the framework acknowledges the context and refers to our formative research that identified the role and influence of grandmothers and fathers that informed intervention design. It then presents participants experiences with the intervention itself, followed by changes participants attributed to their participation in the dialogue groups at the individual, family and community levels. Finally, we connect the findings from this research to the outcomes from the quasi‐experimental study, which found improvements in some complementary feeding practices and increased social support. Key themes and illustrative quotes for each of the topics below are presented in Tables 1 and 2.

FIGURE 1.

Framework depicting how participation in peer dialogue group influenced complementary feeding

TABLE 1.

Illustrative quotes about participants' experiences with their groups

| Theme | Illustrative quotes |

|---|---|

| Purpose of the group |

This group's purpose is for good nutrition because long ago we did not know how to care for our daughters‐in‐law and grandchildren, but now we know. –Grandmother, Group 1 We come to learn how we can care for our children and how to care for our wives … we come to learn and interact with each other. –Father, Group 8 |

| Topics discussed |

The child should be given only breast milk for 6 months. This will avoid diseases. Now I don't run away when my child cries. When my wife leaves me with the child, she expresses milk and leaves it behind for the child. –Father, Group 1 Previously, I did not know that after birth a mum should breastfeed immediately, because it helps the placenta come out. I like these lessons. –Grandmother, Group 9 We have also learnt how to take care of a woman with HIV and the baby why she should go to hospital and how to feed the baby. –Grandmother, Group 6 I have learnt that we must test for HIV with my wife if she is pregnant, to avoid giving birth to an infected child. –Father, Group 4 What is most useful is, I used to take my child to a herbalist when he sick because every time he was sick I felt he was bewitched, but now I have learnt to take my child to hospital. –Father, Group 8 I learned about women and men's work. I learned that there's no man's job and woman's job; we should help one another. –Father, Group 6 |

| Satisfaction with topics |

The meetings were taught well. At first I was not on good terms with my daughter‐in‐law but now the teachings have helped me reconcile with her. –Grandmother, Group 5 The topics were well covered because after the meeting we normally go home and put into practice what we have learnt. –Father, Group 8 |

| Mentor facilitation and group participation |

During these meetings, everyone has the freedom to express themselves and their experiences. In cases where a personal problem was identified, the group members and the mentor would organize to make a home visit to the member to address the issue. –Grandmother, Group 3 I normally enjoy the discussion because everyone participates in asking and answering questions and even shares experiences. There is also no harassment even if you ask a question out of the topic. –Father, Group 3 We can see changes in our family because our mentor taught us well. Our homes are now changed; we do not sell eggs and other food stuffs as we used to do. –Grandmother, Group 1 We participate by discussing. We engage each member in discussions and everyone participates. –Father, Group 8 |

| Perceptions of group |

What I enjoy most is the unity and cooperation we have in the group and this has made me feel united with my members too. –Grandmother, Group 1 When you have a problem and you go to the group and tell them, they can help you. So the group is useful. –Grandmother, Group 8 Now I have become cautious and keen on what my family is eating. I have learnt about the role of a father. –Father, Group 5 I see ALL was good! Nothing was bad!! —Grandmother, Group 5 |

| Tea allowance |

My family members feel good because they know when I come to the meeting, I will get something and they won't stay hungry so they are happy. –Grandmother, Group 8 We should not consider money as the main reason to be here, we learn a lot, and I think the members should look at the benefits of the teachings. Our children's lives are more precious than ‘money’. –Father, Group 1 |

| Merry‐go‐round savings |

We come to this group to learn. Through this group, we have been able to establish a merry‐go‐round, where we are buying and selling chicken and investing the profits. –Grandmother, Group 4 We've talked about a merry‐go‐round, we don't have savings, we don't have financial security, We've agreed we can contribute 200/= [Kenyan Shillings, US$2] each, per month, and buy a goat every month and give one man, then he can at least have something to fall back to in times of emergency. –Father, Group 5 |

| Facilitators and barriers to sustainability |

Unity and cooperation has kept our group going. –Grandmother, Group 7 What we have learned has kept the group moving. We have really learned a lot and gotten more knowledge. –Father, Group 6 If we do not cooperate with our mentor, the group cannot move forward. So we need to cooperate and work together to succeed. –Grandmother, Group 7 Culture could also prevent us from moving forward because when our community sees us helping our wives with work they feel we are going against the traditions of the community. – Father, Group 6 If we don't get the monthly payment, most of us will not turn up for the meetings. –Father, Group 1 |

TABLE 2.

Illustrative quotes from participants about changes they have made related to nutrition and hygiene and changes they have experienced in their families and community

| Theme | Illustrative quotes |

|---|---|

| Participants' changes in nutrition and hygiene practices | |

| Changes in infant feeding practices |

I learnt about a balanced diet, now I don't give my child porridge alone, the child eats what we eat, even chicken, leafy greens, and avocadoes. –Father, Group 1 I have started keeping some fruits from my farm for my family to eat. I do not sell it all. We have started planting some vegetables in the farm with my wife, we eat some and sell some. We only buy meat not vegetables. –Father, Group 1 When my daughter‐in‐law wants to leave, I tell her to express milk and put in a cup. I know how to keep the milk safe and I feed the child even when the mother is away, my grandson is doing very well now. –Grandmother, Group 5 |

| Changes in hygiene practices |

I teach my family members to wash their hands after visiting the toilets. I have put water in a container outsider the toilet so that everyone washed hands after visiting toilet. –Grandmother, Group 1 Before I cook. I clean the pan, clean the food, and cook it well. –Grandmother, Group 6 I ensure that my wife prepares clean water for drinking, sometimes she's too tired or complains, so I purify the water for drinking myself. –Father, Group 4 |

| Increased involvement in women and children's nutrition |

My wife's health is good because I used to leave all the work to her, but now we are helping each other and our child is also healthy. –Father, Group 6 Now I prepare food, I pick vegetables and chop them. I even cook. I have done this very many times. –Father, Group 5 |

| Changes participants have experienced within their families | |

| Improved relationships and communication |

On my side, the group has brought unity and great changes to my family. –Grandmother, Group 1 Before, we had misunderstandings with my wife but since I joined the group, there is harmony because we help each other. –Father, Group 8 |

| Positive reaction from family members |

My family is happy. I teach them what I learn and they have seen the change, they are happy. –Grandmother, Group 5 My son is happy seeing me and my daughter‐in‐law talk and eat together because this never happened before. –Grandmother, Group 7 I try and buy food and ensure that it is balanced. My wife is so happy because they eat well, everyone runs towards me when I come home from work, they want to know what am carrying. –Father, Group 1 |

| Sharing information with family |

When my brother heard that I had taught his wife on how to feed a child, he came and asked me to teach him more so that his children would grow well. He has seen changes in my home. –Father, Group 1 I shared information with my wife and even brothers on good nutrition and a balanced diet for the mother and child. –Father, Group 2 My sister asked me how she could feed her 1.5‐month‐old baby. I told her to breastfeed for 6 months before giving anything else. –Father, Group 7 My family is happy with my group because when I go back home I teach them these teachings and they like them. –Grandmother, Group 5 I have three daughters‐in‐law, I teach all of them and it improves my relationship with them. –Grandmother, Group 9 |

| Community reaction to dialogue groups | |

| Community reaction and sharing information |

One woman asked me what we normally do in our group. I taught her how to care of her family and how to bond with her daughter‐in‐law. I told her to also take care of her grandchildren by feeding them with proper foods –Grandmother, Group 8 My neighbour saw me with a child taking him to the clinic, when I came back, he wanted to know more, I told him to help his wife with housework since she was pregnant and after giving birth, he called me to help him take his child to hospital. –Father, Group 1 A friend of mine asked if he could join the group because of the changes he has seen in my group … They have seen the changes in my family and my life, so they wanted to join. –Father, Group 7 |

| Modelling behaviour in contrast to traditional gender norms |

When we started, they did not like it. They said, how can you people do women's and children's work. You are stupid.” But, now they have seen the changes and are happy. –Father, Group 1 Initially they said, “this man does not have brains. What kind of a woman is this who is controlling him?”. –Father, Group 5 |

3.1. Group purpose and topics discussed

Both grandmothers and fathers described the purpose of their group was to learn about MIYCN and improve family relationships (Tables 1 and 2). They reported discussing many of the same topics in their groups including exclusive breastfeeding; complementary feeding particularly, dietary diversity, and the timing of the introduction of complementary foods; childcare broadly; encouraging antenatal care; rest and good nutrition during pregnancy; health facility deliveries; growing nutrient‐rich foods; HIV and infant feeding; and the prevention of mother‐to‐child transmission of HIV. A few fathers and grandmothers mentioned that they talked about feeding expressed breast milk when mothers were away. Grandmothers in each group mentioned they frequently talked about hygiene and food safety and the importance of early initiation of breastfeeding. Fathers also reported talking about caring for their families, caring for sick children and taking them to the health centre, accompanying their wives to antenatal clinics, caring for women during pregnancy, and buying healthy foods. In addition, fathers reported talking about improving relationships and communication with their spouses and sharing responsibilities at home. Fathers also mentioned how their groups discussed fathers' roles and division of household labour and how they can be more involved. Almost all grandmother groups and father groups were satisfied with the topics discussed, reporting topics were covered well, which several said led to positive changes at home.

3.2. Mentor facilitation

Overall, grandmothers and fathers were happy with how mentors facilitated their groups (Table 1). Both grandmothers and fathers reported mentors were very flexible, allowed changes in topics or the order of topics, and gave members time to speak, share, and ask questions. A few grandmothers mentioned the mentor followed up by addressing problems or issues that were raised during meetings through home visits.

3.3. Group participation

Both grandmothers and fathers reported attending meetings regularly, twice a month. They also reported feeling free to actively participate by sharing their opinions and experiences (Table 1). They described being able to ask and answer questions during meetings and reminding each other of what they have learned. Several grandmothers mentioned helping each other if members had a problem, and one group mentioned visiting each other at home to follow up. A few grandmothers also reported singing or reciting poems during meetings. Both grandmothers and fathers reported they and their families appreciated the nominal amount of money they received for chai (tea) at group meetings. Several mentioned it motivated attendance. Fathers and grandmothers described using the money to buy food for their family, a reflection of the low socio‐economic status of most participants. Further, half of the grandmothers' groups reported starting ‘merry‐go‐round’ savings activities (rotating informal savings and loans) using the allowance. In comparison, one of the fathers' groups had incorporated group savings activities, and other fathers' groups said they should incorporate them in the future to help with sustainability.

3.4. Group members' perceptions of their groups

Fathers and grandmothers enjoyed learning about nutrition, breastfeeding, complementary feeding, childcare and improving relationships with their wives or daughters‐in‐law (Table 1). Grandmothers and fathers also reported improvements in their children's or grandchildren's health. Grandmothers and fathers identified the group's unity and dynamics were positive aspects. Fathers were happy with group members actively participating, applying what they have learned, not being limited by traditional gender norms around caregiving, teaching others in the community, caring for their family and helping their wives.

When groups were asked to describe negative aspects of their groups, almost all grandmother and more than half of father groups reported that there was little negative. A few fathers and one grandmother mentioned members arriving late and one fathers' group reported some members occasionally not attending meetings.

3.5. Nutrition and health changes reported by participants

Fathers and grandmothers reported many changes as a result of their dialogue groups (Table 2).

3.5.1. Infant feeding

Both grandmothers and fathers attributed changes in complementary feeding practices to their participation. Although grandmothers reported specific changes that were different from previous practices, fathers reported increased involvement in infant feeding. A few grandmothers reported giving children more variety of foods, such as more fruit, and a few others mentioned changes to food preparation, such as adding ingredients to porridge or making porridge thicker. Fathers reported bringing more foods specifically for the child, which grandmothers also reported. A few fathers mentioned they now feed the child when the mother is away. One grandmother and a few fathers reported giving expressed breast milk while the mother is out.

3.5.2. Hygiene practices

Both grandmothers and fathers reported improvements in hygiene and food safety practices. Grandmothers mentioned changes related to hand washing and overall cleanliness. Additionally, a few grandmothers talked about following food safety practices. A couple fathers mentioned improved food safety, hand washing and clean water.

3.5.3. Other health behaviours

Fathers also reported changes related to broader maternal and child health and health seeking behaviour. Fathers talked about taking children to the clinic themselves or suggesting their wives take their children to the clinic when ill rather than seeking care from herbalists. A few fathers described encouraging pregnant women to seek antenatal care from health facilities. In contrast, only one grandmother reported a change related to encouraging health seeking from facilities.

3.5.4. Father involvement and roles

Fathers reported increased involvement at home and improved relationships with their wives. They also talked about bringing home food, helping prepare and plan meals, helping with domestic tasks, and caring for children and wives, especially when pregnant. Fathers discussed how their views of their roles in their family had changed. Half of the fathers' groups discussed helping their wives and sharing responsibilities, despite going against traditional norms.

3.5.5. Changes within families

All father and grandmother groups reported changes within their families as a result of their participation in the groups (Table 2).

3.5.6. Improved relationships and communication

It was very common for grandmothers and fathers to report improvements in family relationships and increased feelings of peace, harmony, and unity. Grandmothers reported improved relationships with their daughters‐in‐law and described how their daughters‐in‐law had greater trust for how they cared for their grandchildren. Many grandmothers mentioned that learning about relationships and communication enabled them to talk and share with their daughters‐in‐law more than before and that these changes in communication resulted in overall improved relationships. Fathers also reported improved communication with their wives through working together and helping their wives with domestic work. A few fathers also reported talking with their wives more about food and how it should be prepared.

3.5.7. Family reaction

Grandmothers and fathers from all groups reported positive reactions from family members and that their families were happy with the information being shared, improved relationships and positive changes. Fathers also reported that their family members were happy because of increased involvement at home and sharing responsibilities. A few grandmothers and fathers mentioned other family members wanting to join the group. However, several fathers reported negative reactions about their involvement in work that was traditionally viewed as women's responsibilities.

3.5.8. Sharing information

Grandmothers and fathers from all groups reported sharing information with their families, particularly around exclusive breastfeeding and complementary feeding (e.g., balanced diets and dietary diversity), and to a lesser extent health seeking.

3.6. Sharing information with their community

Both grandmothers and fathers reported sharing information beyond their families, with their community, specifically what they learned about nutrition, health, and hygiene practices (Table 2). Many grandmothers and fathers described their neighbours and community members asking them for information about nutrition. A couple of grandmothers mentioned sharing information with others when they noticed someone not practicing recommended behaviours. Some grandmothers shared information during church and women's meetings. Like grandmothers, fathers reported sharing information outside their families, sometimes during church and other meetings. A couple fathers also reported sharing information with community members when they noticed specific issues, such as other fathers quarrelling with their wives or children with poor health. Grandmothers and fathers talked about enjoying sharing what they learned with others in their community. A few grandmothers' groups reported organizing community events to share information, conduct cooking demonstrations and perform songs and dramas. A few fathers and grandmothers also reported their groups were invited to share information during other planned community events. One grandmother group requested more training on how to share information with others in their community, and another grandmother group thought it may be difficult to organize an event because community members would anticipate payment, because they knew about the tea allowance the group members received.

3.6.1. Community reaction

Most grandmothers and fathers reported positive reactions from others in the community about their groups. They said community members were interested in participating in the group and asked questions about the group and nutrition based on positive changes they had observed in the group members' families. However, a few grandmothers and fathers reported some community members feeling left out or negatively towards the group because they were not invited. A few fathers mentioned community members' negative reactions to men doing ‘women's work’ initially, but over time, they began to see the benefits. Another father shared his experience with neighbours being surprised that the father was helping with household chores and then wanting to do the same.

3.7. Group sustainability

Most grandmother and father groups stated that they planned for their groups to continue meeting after the study ended (Table 1). When asked what was needed to ensure their groups would continue, both grandmothers and fathers included incorporating or continuing income generating activities and informal savings activities into their meetings, taking steps to become more official (e.g., uniforms, certificates, books or reading materials, registering), and increasing the number of group members. A few fathers suggested including their wives in the group activities. A few grandmothers and fathers stressed the importance of the support they received from their mentor. When asked about potential barriers to sustainability, both grandmothers and fathers reported absenteeism or members arriving late. Several grandmothers also reported gossip as a potential barrier but did not express that this was a current issue in their group. Grandmothers and fathers cited unity and positive group dynamics as facilitators to group sustainability. Both fathers and grandmothers talked about the importance of the nominal allowance in sustaining their group. Fathers from two groups speculated that some members may stop coming, whereas others thought most members would continue even without the allowance.

4. DISCUSSION

This study describes the pathway through which engaging fathers and grandmothers can impact infant feeding behaviours. From previous formative research, we learned that family support is important for infant feeding, particularly breastfeeding (Thuita et al., 2015; USAID's IYCN, 2011), which is consistent with other studies (Aubel et al., 2004; Karmacharya et al., 2017; Pisacane et al., 2005; Wolfberg et al., 2004). In this study, we investigated the experiences of fathers and grandmothers in peer dialogue groups designed to increase infant feeding support to mothers and how their experiences led to behaviour changes. Through our analysis, we found that fathers and grandmothers attributed changes at the individual, family and community levels to their participation in peer dialogue groups. Our framework (Figure 1) illustrates that the peer dialogue group works through participant changes not only in knowledge, attitudes and behaviours but also in perceived roles, family relationships, information sharing and modelling at home, in their groups, and in the community.

We proposed that changing mothers' social environment by increasing support and involvement from fathers and grandmothers will enable them to practice improved infant feeding behaviours they learned through contact with the health system. Fathers and grandmothers are key family decision makers, and their support is necessary for child health and nutrition. The active participation of fathers and grandmothers in peer dialogue groups improved their individual knowledge and behaviours around key infant feeding practices, strengthened their communication and relationship skills and provided encouragement for them to share their new knowledge and behaviours in the family and community. The mentor facilitation, individual reflections, experience sharing and problem‐solving that is part of the dialogue group reinforced the new knowledge and information (Abusabha et al., 1999; Affleck & Pelto, 2012; Bezner Kerr et al., 2019). As reported by both grandmothers and fathers, the peer support and unity they experienced were important aspects of these groups that built their social capital (trust, reciprocity and social networks), which is similar to what is reported elsewhere with women's groups (Kumar et al., 2018; Kumar & Quisumbing, 2011). Bonding social capital (relations and trust between individuals) and cognitive social capital (common understanding and knowledge) appears to be operating within the groups and between the grandmothers and fathers and their daughters and daughters in‐laws and wives at home through increased social support for infant feeding (Kang et al., 2018). At the family level, reducing gender inequity is integral to improving women's agency over their own decisions (Kumar et al., 2018). As women gain support from men and the community, they can act on promoting their health and their children's health (Sraboni et al., 2014). In our study, fathers reported helping their wives and sharing responsibilities, despite going against traditional norms. These changes were witnessed in the community as well and received some ridicule. Nevertheless, the fathers reported sharing their new knowledge in the community and modelling new behaviours. Positive changes were noted in the family as grandmother and father groups reported positive reactions from family members, with improved relationships, more peace and harmony, increased knowledge and increased father involvement at home and sharing responsibilities with the mothers, consistent with findings from other intervention studies with fathers and grandmothers (Aubel et al., 2004; Betancourt et al., 2011; Doyle et al., 2014). These reported changes are consistent with reports from mothers in our quantitative research (Mukuria et al., 2016).

Fathers and grandmother's participation in the dialogue groups led to their gaining knowledge and influence in the community. For the most part, fathers and grandmothers reported a positive reaction from the community about their groups and the positive changes the community observed in the group members' families. This may have led to their enhanced roles in the community and at home.

The dialogue groups provided social cohesion for fathers and grandmothers, which is a component of social capital that creates a sense of trust and solidarity that has been shown to influence changes in social norms (Story, 2014). Grandmothers and fathers reported the group's unity and dynamics were positive aspects that built their trust and confidence to address some social norms. Contrary to cultural norms, fathers reported engaging and promoting maternal and child nutrition and health seeking behaviours for sick children. Both fathers and grandmothers reported sharing information around exclusive breastfeeding (while the norm is early supplementation) and complementary feeding (diet diversity is low in the early complementary feeding period). Similar informal information sharing through social networks was reported in a systematic review of community group interventions (Gram et al., 2019).

Aspects of the dialogue groups that were important and influential for the participants included being able to have their questions answered, listening to teachings, and joint problem solving if a member encountered a problem. The trust built within the group was demonstrated in the demand to include merry‐go‐round savings and loan activities in some of the grandmother groups. A grandmother participant said that through the merry‐go‐round activities, they worked together and that ‘unity is power’. Merry‐go‐round by grandmothers leads to improved practices through an income pathway, providing more resources for grandmothers to practice the behaviour changes related to diet diversity and adding ingredients to porridge that they can afford with the additional resources from the merry go round and the ‘chai’ they received at each meeting. In this low‐income rural community, people's time is valuable for farming or other income generating activities; we encouraged bimonthly attendance of the groups by providing chai. The groups preferred to receive chai in cash form than refreshments during meetings. Participants appreciated this small amount of money and for several participants it enabled them to support some of the new behaviours like purchasing food items or helping with other expenses. However, it was not without its problems. Nongroup members felt left out and expressed jealousy and negativity towards group members. Where resources are very limited, cash allowances need to be handled with care. Overall, the participants reported a positive experience with the groups, which lead to positive outcomes of increased family support for infant feeding practices.

One limitation from this study was that we did not collect qualitative data from mothers directly and so could not similarly examine their experiences. However, through the surveys with mothers we have quantitative data from the quasi‐experimental study, which found mothers in the intervention group areas received significantly more support for complementary feeding than mothers in the comparison areas and support our findings (Mukuria et al., 2016). In addition, the interviews with peer educators are consistent with our findings (Martin et al., 2015). It is possible that participants' responses were influenced by social desirability bias. To minimize this risk, data collectors assured participants that we were interested in their experiences, both positive and negative, as well as barriers to recommended practices. The study could also be affected by self‐selection bias, as fathers and grandmothers who agreed to participate in the interventions were more likely to be interested in learning about MIYCN than fathers and grandmothers who were not interested in maternal and child nutrition or supporting their wives or daughters‐in‐law. It is possible that fathers and grandmothers who participated in the dialogue groups do not reflect every father and grandmother in the target population.

In order to change infant feeding behaviours, social norms need to reinforce recommendations with support from influential members of mothers' social networks, especially fathers and grandmothers (Nguyen et al., 2019). This is how the social environment in which mothers make decisions and practice nutrition behaviours can be strengthened thereby empowering mothers in their nutrition practices, engaging fathers in child nutrition and supporting better communications. (Doyle et al., 2018; Heckert et al., 2019). We found that peer dialogue groups can engage influential family members, increase their knowledge, build their social capital at home and the community and positively influence infant feeding practices. The fathers and grandmothers found their groups' participatory and flexible facilitation methods encouraged experience sharing, reflection and social cohesion. Occasionally bringing all family members together (i.e., mothers, fathers and grandmothers) for some meetings may further strengthen family support for recommended practices as seen in other recent studies (Bezner Kerr et al., 2016).

In addition to the dialogue groups, other multichannel behaviour change strategies that include community leaders, community mobilization activities, and mass media activities can encourage community‐wide support for optimal infant feeding practices (Nguyen et al., 2019; Sanghvi et al., 2017). Also in low‐income settings, incorporating income generating activities or cash or resource transfers has proven effective to enable participants to improve infant feeding (Hoddinott et al., 2018) and was requested by participants in our groups as well. Including an income generating activity in father and grandmother groups has the potential to promote group sustainability. Recognition of the group participants could be enhanced with simple incentives such as awards of certificates, building their standing in the community and the household. In conclusion, this study highlights the importance of engaging influential family members to support MIYCN, by building on grandmothers' roles as advisors and expanding on fathers' roles through gender transformative activities. Dialogue groups led to increased support for MIYCN and a supportive environment for fathers and grandmothers. It is recommended that intervention studies to improve MIYCN that engage the broader family using grandmother and father groups consider their experiences being part of the groups to have a stronger impact and in turn build their capacity to improve the social environment of the family for MIYCN.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

CONTRIBUTIONS

AGM, FT and SLM designed this research. FT and TM oversaw data collection. SLM, SG and KHL analysed the data. AGM, FT and SLM wrote the paper. All authors contributed to critically revising the paper and approved the final version.

Supporting information

Table S1. BCTs and specific intervention components used

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful to the grandmother and father peer educators in Vihiga County for participating in this research, as well as the dedicated community health workers, community health extension workers, and Ministry of Health staff for their support. This study was funded through support provided by the United States Agency for International Development, under IYCN Cooperative Agreement No. GPO‐A‐00‐06‐00008‐00 and APHIAplus Cooperative Agreement No. AID‐623‐A‐11‐00002. Denise Lionetti, Rikka Trangsrud, Janet Shauri, Kiersten Israel‐Ballard and Allison Bingham provided critical programme support and technical guidance. Stephanie Martin received support from NICHD of the National Institutes of Health under award number P2C HD050924.

Thuita F, Mukuria A, Muhomah T, Locklear K, Grounds S, Martin SL. Fathers and grandmothers experiences participating in nutrition peer dialogue groups in Vihiga County, Kenya. Matern Child Nutr. 2021;17:e13184. 10.1111/mcn.13184

Funding information National Institutes of Health, Grant/Award Number: P2C HD050924; United States Agency for International Development, Grant/Award Numbers: AID‐623‐A‐11‐00002, GPO‐A‐00‐06‐00008‐00

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

REFERENCES

- Abusabha, R. , Peacock, J. , & Achterberg, C. (1999). How to make nutrition education more meaningful through facilitated group discussions. Journal of American Dietetic Association, 99(1), 72–76. 10.1016/S0002-8223(99)00019-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Affleck, W. , & Pelto, G. (2012). Caregivers' responses to an intervention to improve young child feeding behaviors in rural Bangladesh: A mixed method study of the facilitators and barriers to change. Social Science & Medicine, 75(4), 651–658. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.03.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aubel, J. , Toure, I. , & Diagne, M. (2004). Senegalese grandmothers promote improved maternal and child nutrition practices: The guardians of tradition are not averse to change. Social Science & Medicine, 59(5), 945–959. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.11.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt, T. S. , Meyers‐Ohki, S. , Stulac, S. N. , Barrera, A. E. , Mushashi, C. , & Beardslee, W. R. (2011). Nothing can defeat combined hands (Abashize hamwe ntakibananira): Protective processes and resilience in Rwandan children and families affected by HIV/AIDS. Social Science & Medicine, 73(5), 693–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezner Kerr, R. , Chilanga, E. , Nyantakyi‐Frimpong, H. , Luginaah, I. , & Lupafya, E. (2016). Integrated agriculture programs to address malnutrition in northern Malawi. BMC Public Health, 16(1), –1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezner Kerr, R. , Young, S. L. , Young, C. , Santoso, M. V. , Magalasi, M. , Entz, M. , & Snapp, S. S. (2019). Farming for change: developing a participatory curriculum on agroecology, nutrition, climate change and social equity in Malawi and Tanzania. Agriculture and Human Values, 36(3), 549–566. 10.1007/s10460-018-09906-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhutta, Z. A. , Ahmed, T. , Black, R. E. , Cousens, S. , Dewey, K. , Giugliani, E. , Haider, B. A. , Kirkwood, B. , Morris, S. S. , Sachdev, H. P. S. , & Shekar, M. (2008). What works? Interventions for maternal and child undernutrition and survival. The Lancet, 371, 417–440. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61693-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhutta, Z. A. , Das, J. K. , Rizvi, A. , Gaffey, M. F. , Walker, N. , Horton, S. , Webb, P. , Lartey, A. , Black, R. E. , Group TL , & Maternal and Child Nutrition Study Group . (2013). Evidence‐based interventions for improvement of maternal and child nutrition: what can be done and at what cost? The Lancet. Aug 3, 382(9890), 452–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black, R. E. , Allen, L. H. , Bhutta, Z. A. , Caulfield, L. E. , de Onis, M. , Ezzati, M. , Mathers, C. , & Rivera, J. (2013). Maternal and child undernutrition: Global and regional exposures and health consequences. The Lancet, 371, 243–260. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61690-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black, R. E. , Allen, L. H. , Bhutta, Z. A. , Caulfield, L. E. , de Onis, M. , Ezzati, M. , Mathers, C. , Rivera, J. , & for the Maternal and Child Undernutrition Study Group . (2008). Maternal and child undernutrition: Global and regional exposures and health consequences. The Lancet, 371(9608), 243–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black, R. E. , Victora, C. G. , Walker, S. P. , Bhutta, Z. A. , Christian, P. , De Onis, M. , Ezzati, M. , Grantham‐McGregor, S. , Katz, J. , Martorell, R. , & Uauy, R. (2013). Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low‐income and middle‐income countries. The Lancet, 382, 427–451. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60937-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, J. , & Strauss, A. L. (2008). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle, K. , Kato‐Wallace, J. , Kazimbaya, S. , & Barker, G. (2014). Transforming gender roles in domestic and caregiving work: Preliminary findings from engaging fathers in maternal, newborn, and child health in Rwanda. Gender & Development, 22(3), 515–531. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle, K. , Levtov, R. G. , Barker, G. , Bastian, G. G. , Bingenheimer, J. B. , Kazimbaya, S. , Nzabonimpa, A. , Pulerwitz, J. , Sayinzoga, F. , Sharma, V. , & Shattuck, D. (2018). Gender‐transformative Bandebereho couples' intervention to promote male engagement in reproductive and maternal health and violence prevention in Rwanda: findings from a randomized controlled trial. PLoS One, 13(4), e0192756. 10.1371/journal.pone.0192756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie, S. , & van den Bold, M. (2017). Stories of Change in nutrition: An overview. Global Food Security, 13, 1–11. 10.1016/j.gfs.2017.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gram, L. , Fitchett, A. , Ashraf, A. , Daruwalla, N. , & Osrin, D. (2019). Promoting women's and children's health through community groups in low‐income and middle‐income countries: A mixed‐methods systematic review of mechanisms, enablers and barriers. BMJ Global Health, 4(6), e001972. 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckert, J. , Olney, D. , & Ruel, M. (2019). Is women's empowerment a pathway to improving child nutrition outcomes in a nutrition‐sensitive agriculture program?: Evidence from a randomized controlled trial in Burkina Faso. Social Science & Medicine, 233, 93–102. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.05.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoddinott, J. , Ahmed, A. , Karachiwalla, N. I. , & Roy, S. (2018). Nutrition behaviour change communication causes sustained effects on IYCN knowledge in two cluster‐randomised trials in Bangladesh. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 14(1), e12498. 10.1111/mcn.12498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Infant & Young Child Nutrition Project (IYCN) . (2011). Engaging Grandmothers and Men in Infant and Young Child Feeding and Maternal Nutrition. Report of a formative assessment in Eastern and Western Kenya. Washington: PATH. Available from http://iycn.wpengine.netdna‐cdn.com/files/IYCN_Kenya‐Engaging‐Grandmothers‐and‐Men‐Formative‐Assessment_0511.pdf

- IYCN . (2011a). Engaging grandmothers to improve nutrition: A training manual and guide for dialogue group mentors. Washington, DC: PATH. http://www.iycn.org/resource/engaging-grandmothers-to-improve-nutrition-a‐training‐manual‐and‐guide‐for‐dialogue‐group‐mentors/ [Google Scholar]

- IYCN . (2011b). Infant and Young child feeding and gender: A training manual and participant manual for male group leaders. Washington, DC: PATH. http://www.iycn.org/resource/infant-and-young-child‐feeding‐and‐gender‐trainers‐manual‐and‐participants‐manual/ [Google Scholar]

- Janmohamed, A. , Sohani, N. , Lassi, Z. S. , & Bhutta, Z. A. (2020). The Effects of community home visit and peer group nutrition intervention delivery platforms on nutrition outcomes in low and middle‐income countries: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Nutrients, 12(2), 440. 10.3390/nu12020440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang, Y. , Kim, J. , & Seo, E. (2018). Association between maternal social capital and infant complementary feeding practices in rural Ethiopia. Maternal and Child Nutrition, 14, e12484. 10.1111/mcn.12484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karmacharya, C. , Cunningham, K. , Choufani, J. , & Kadiyala, S. (2017). Grandmothers' knowledge positively influences maternal knowledge and infant and young child feeding practices. Public Health Nutrition, 20(12), 2114–2123. 10.1017/S1368980017000969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS) . and ICF Macro . (2010). Kenya Demographic and Health Survey 2008–09.

- KNBS , MOPHS , & KEMRI . (2013). The Kenya National Micronutrient Survey 2011.

- Kumar, N. , & Quisumbing, A. R. (2011). Access, adoption, and diffusion: understanding the long‐term impacts of improved vegetable and fish technologies in Bangladesh. Journal of Development Effectiveness, 3, 193–219. 10.1080/19439342.2011.570452 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, N. , Scott, S. , Menon, P. , Kannan, S. , Cunningham, K. , Tyagi, P. , Wable, G. , Rughunathan, K. , & Quisumbing, A. (2018). Pathways from women's group‐based programs to nutrition change in South Asia: A conceptual framework and literature review. Global Food Security. Jun, 17, 172–185. 10.1016/j.gfs.2017.11.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewycka, S. , Mwansambo, C. , Rosato, M. , Kazembe, P. , Phiri, T. , Mganga, A. , Chapota, H. , Malamba, F. , Kainja, E. , Newell, M. L. , Greco, G. , Pulkki‐Brännström, A. M. , Skordis‐Worrall, J. , Vergnano, S. , Osrin, D. , & Costello, A. (2013). Effect of women's groups and volunteer peer counselling on rates of mortality, morbidity, and health behaviours in mothers and children in rural Malawi (MaiMwana): A factorial, cluster‐randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, 381(9879), 1721–1735. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61959-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linnan, L. , & Steckler, A. (2002). Process evaluation for public health interventions and research: An Overview. In Linnan L. & Steckler A. (Eds.), Process evaluation for public health interventions and research (pp. 1–24). San Francisco: Jossey‐Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, S. L. , McCann, J. K. , Gascoigne, E. , Allotey, D. , Fundira, D. , & Dickin, K. L. (2020). Mixed‐methods systematic review of behavioral interventions in low‐ and middle‐income countries to increase family support for maternal, infant, and young child nutrition during the first 1000 days. Current Developments in Nutrition, 4(6). 10.1093/cdn/nzaa085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin, S. L. , Muhomah, T. , Thuita, F. , Bingham, A. , & Mukuria, A. G. (2015). What motivates maternal and child nutrition peer educators? Experiences of fathers and grandmothers in western Kenya. Social Science & Medicine, 143, 45–53. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.08.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michie, S. , Richardson, M. , Johnston, M. , Abraham, C. , Francis, J. , Hardeman, W. , Eccles, M. P. , Cane, J. , & Wood, C. E. (2013). The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 46(1), 81–95. 10.1007/s12160-013-9486-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health . (2016). Baby Friendly Community Initiative Implementation Guidelines.

- Mukuria, A. G. , Martin, S. L. , Egondi, T. , Bingham, A. , & Thuita, F. M. (2016). Role of social support in improving infant feeding practices in Western Kenya: A quasi‐experimental study. Global Health Science and Practice, 4(1), 55–72. 10.9745/GHSP-D-15-00197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, P. H. , Frongillo, E. A. , Kim, S. S. , Zongrone, A. A. , Jilani, A. , Tran, L. M. , Sanghvi, T. , & Menon, P. (2019). Information diffusion and social norms are associated with infant and young child feeding practices in Bangladesh. Journal of Nutrition, 149(11), 2034–2045. 10.1093/jn/nxz167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, J. N. , Olney, D. K. , Ouedraogo, M. , Pedehombga, A. , Rouamba, H. , & Yago‐Wienne, F. (2018). Process evaluation improves delivery of a nutrition‐sensitive agriculture programme in Burkina Faso. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 14(3), 1‐10, e12573. 10.1111/mcn.12573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nisbett, N. , van den Bold, M. , Gillespie, S. , Menon, P. , Davis, P. , Roopnaraine, T. , Kampman, H. , Kohli, N. , Singh, A. , & Warren, A. (2017). Community‐level perceptions of drivers of change in nutrition: Evidence from South Asia and sub‐Saharan Africa. Global Food Security, 13, 74–82. 10.1016/j.gfs.2017.01.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pisacane, A. , Continisio, G. I. , Aldinucci, M. , D'Amora, S. , & Continisio, P. (2005). A controlled trial of the father's role in breastfeeding promotion. Pediatrics, 116(4), e494–e498. 10.1542/peds.2005-0479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qar, Z. , Bhutta, A. , Das, J. K. , Rizvi, A. , Gaff, M. F. , Walker, N. , Black, R.E , Maternal and Child Nutrition 2 . (2013). Evidence‐based interventions for improvement of maternal and child nutrition: What can be done and at what cost? The Lancet Nutrition Interventions Review Group, and the Maternal and Child Nutrition Study Group, 382. www.thelancet.com, 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60996-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanghvi, T. , Seidel, R. , Baker, J. , & Jimerson, A. (2017). Using behavior change approaches to improve complementary feeding practices. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 13, e12406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sraboni, E. , Malapit, H. J. , Quisumbing, A. R. , & Ahmed, A. U. (2014). Women's empowerment in agriculture: What role for food security in Bangladesh? World Development, 61, 11–52. 10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.03.025 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Story, W. T. (2014). Social capital and the utilization of maternal and child health services in India: A multilevel analysis. Health & Place, 28, 73–84. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2014.03.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thuita, F. M. , Martin, S. , Ndegwa, K. , Bingham, A. , & Mukuria, A. (2015). Engaging fathers and grandmothers to improve maternal and child dietary practices: Planning a community‐based study in western Kenya|African Journal of Food, Agriculture, Nutrition and Development. African Journal of Food, Agriculture, Nutrition and Development, 10386–10405. [Google Scholar]

- USAID's Infant and Young Child Nutrition Project (IYCN) . (2011). Engaging grandmothers and men in infant and young child feeding and maternal nutrition: Report of a formative assessment in Eastern and Western Kenya. Retrieved from http://iycn.wpengine.netdna‐cdn.com/files/IYCN_Kenya‐Engaging‐Grandmothers‐and‐Men‐Formative‐Assessment_0511.pdf

- Webb Girard, A. , Waugh, E. , Sawyer, S. , Golding, L. , & Ramakrishnan, U. (2020, January 1). A scoping review of social‐behaviour change techniques applied in complementary feeding interventions. Maternal and Child Nutrition, 16, e12882. 10.1111/mcn.12882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfberg, A. J. , Michels, K. B. , Shields, W. , O'Campo, P. , Bronner, Y. , & Bienstock, J. (2004). Dads as breastfeeding advocates: Results from a randomized controlled trial of an educational intervention. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 191(3), 708–712. 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.05.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. BCTs and specific intervention components used

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.