Abstract

Exogenous application of double-stranded RNAs (dsRNAs) and small-interfering RNAs (siRNAs) to plant surfaces has emerged as a promising method for regulation of essential genes in plant pathogens and for plant disease protection. Yet, regulation of plant endogenous genes via external RNA treatments has not been sufficiently investigated. In this study, we targeted the genes of chalcone synthase (CHS), the key enzyme in the flavonoid/anthocyanin biosynthesis pathway, and two transcriptional factors, MYBL2 and ANAC032, negatively regulating anthocyanin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Direct foliar application of AtCHS-specific dsRNAs and siRNAs resulted in an efficient downregulation of the AtCHS gene and suppressed anthocyanin accumulation in A. thaliana under anthocyanin biosynthesis-modulating conditions. Targeting the AtMYBL2 and AtANAC032 genes by foliar dsRNA treatments markedly reduced their mRNA levels and led to a pronounced upregulation of the AtCHS gene. The content of anthocyanins was increased after treatment with AtMYBL2-dsRNA. Laser scanning microscopy showed a passage of Cy3-labeled AtCHS-dsRNA into the A. thaliana leaf vessels, leaf parenchyma cells, and stomata, indicating the dsRNA uptake and spreading into leaf tissues and plant individual cells. Together, these data show that exogenous dsRNAs were capable of downregulating Arabidopsis genes and induced relevant biochemical changes, which may have applications in plant biotechnology and gene functional studies.

Keywords: exogenous dsRNA, plant foliar treatment, plant gene regulation, RNA interference, gene silencing, anthocyanins

1. Introduction

The current RNA-based crop improvement studies employ the RNA interference (RNAi) phenomenon for downregulation of gene targets in plants for further plant disease control and crop management [1,2]. The principles of the RNAi phenomenon are also being actively exploited in plant gene functional studies. RNAi is a natural regulatory mechanism that involves sequence-specific degradation of target mRNAs or translation inhibition induced by short small-interfering RNAs (siRNAs) or microRNAs (miRNAs) originated from long double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) precursors that may vary in length and origin [3,4]. Plants have developed RNAi as an effective mechanism implicated in plant pathogen and viral defense [5], plant growth and development [6], and abiotic stress responses [7]. In the course of RNAi, long dsRNAs precursors are recognized and processed by a ribonuclease DICER into small RNA duplexes of 20–24-nucleotide (nt)-long, i.e., siRNAs and miRNAs [3]. These siRNAs are then incorporated into the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) that drives silencing of the target mRNAs via their cleavage, destabilization, or hindering translation.

The major RNAi-based crop improvement/protection strategies include the generation of dsRNA/hairpin RNA (hpRNA)-expressing transgenic plants and host-induced gene silencing (HIGS), which allowed the silencing of genes in plant microbial pathogens [8,9,10] or application of modified plant viruses inducing degradation of target plant mRNA, i.e., virus-induced gene silencing or VIGS [11]. RNAi-based insect management strategies include generation of transgenic plants expressing dsRNAs targeting essential insect genes, feeding insects with dsRNAs, or plant foliar treatments with dsRNAs [12,13]. However, the consequences of plant genetic modifications are not clear, which raises serious public concerns on their impacts on human health and environment [14]. Furthermore, generation of transgenic plants is a costly and a complicated process for many horticultural crops. Although VIGS does not require genetic modifications of plants, this method possesses serious limitations that prevent its wide application [15]. Therefore, development of an alternative approach for plant gene regulation without genomic modifications is an important challenge for plant biotechnology.

There is an increasing number of studies that show induction of plant fungal [16,17,18,19,20,21] and viral [22,23,24,25,26,27] resistance after external application (spraying or mechanical inoculation) of dsRNAs, siRNAs, or hpRNAs designed to target virulence-related genes of the pathogens. Recent studies have also provided evidence that both plants and infecting pathogens were capable of the RNA uptake, and this eventually triggered RNAi-mediated silencing of the pathogen virulence-related genes [16,17,21,22,27]. Exogenously induced RNAi has recently emerged as a strategy with a potential to protect plants from microbial diseases, viral infections, and invading insects [9,28,29].

Several studies reported that external application of dsRNAs [22,30,31] to Arabidopsis thaliana and siRNAs [32,33,34] to A. thaliana or Nicotiana benthamiana triggered silencing of common plant transgenes, such as green fluorescent protein (GFP), β-glucuronidase (GUS), yellow fluorescent protein (YFP), or neomycin phosphotransferase II (NPTII). Plant transgenes are known to be more prone for RNAi-mediated suppression in comparison with plant endogenes [35,36,37], and, therefore, targeting transgenes might be more achievable. However, there are also data showing that naked GFP-dsRNAs and GFP-hpRNAs did not induce GFP silencing in N. benthamiana and were not processed into siRNAs, indicating insufficient dsRNA uptake by plant cells [38,39]. According to Numata et al. [32] and Dalakouras et al. [33], downregulation of the GFP and YFP transgenes after foliar application of siRNAs was successful only after application of accessory technologies (using carrier peptide or high-pressure spraying). According to our recent data, appropriate plant age, late time of day, low soil moisture (at the moment of dsRNA application), and optimal dsRNA application modes were important for efficient NPTII transgene suppression in A. thaliana induced by direct foliar dsRNA treatments [31].

To the best of our knowledge, there are four investigations and a patent that showed that external plant treatments with naked dsRNAs led to downregulation of plant endogenous genes, including silencing of the 3-phosphate synthase (EPSPS) gene in tobacco and amaranth leaves [40], MYB1 gene in the orchid flower buds [41], Mob1A, WRKY23, and Actin genes in Arabidopsis and rice [42], two sugar transporter genes STP1 and STP2 in tomato seedlings [43], and a downy mildew susceptibility gene LBDIf7 in grapevine [44]. According to the data, external plant dsRNA treatments led to the dsRNA uptake, reduced mRNA levels of the gene targets, and some phenotypic or biochemical changes. There were also experimental findings where nanoparticles [45] and laser light [46] were used to ensure perception of exogenous dsRNA and downregulation of the targeted endogenous genes SHOOT MERISTEMLESS (STM) and WEREWOLF (WER) in A. thaliana and phytoene desaturase (PDS) gene in Citrus macrophylla after external dsRNA treatments.

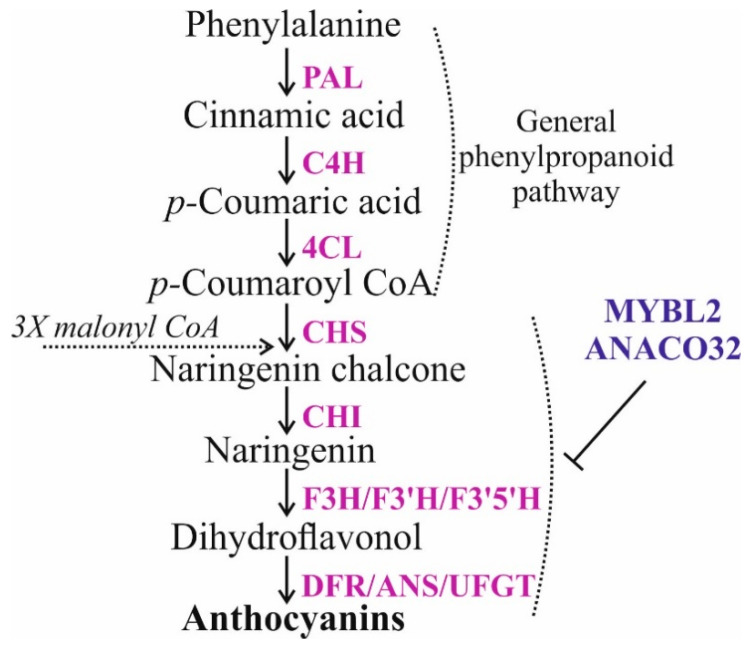

Anthocyanins are naturally occurring colored pigments derived from the plant phenylpropanoid pathway and are relatively easy to induce for accumulation and quantitative analysis [47,48]. Apart from providing color to plants and animal attraction, anthocyanins are known to possess beneficial human health effects and plant protective properties against pests and pathogens [47,49]. Therefore, in the present study, we targeted anthocyanin biosynthesis-related genes (Figure 1), including chalcone synthase (CHS) and two transcriptional repressors, a R3-type single-MYB protein MYBL2 and a NAC-type transcription factor ANAC032 genes, in A. thaliana by direct foliar treatments with dsRNAs and siRNAs. This analysis quantitatively documented changes in AtCHS, AtMYBL2, and AtANAC032 gene expression and anthocyanin production after the foliar dsRNA and siRNA applications. To prove the specificity of the downregulation effect, we also treated wild-type A. thaliana with dsRNAs and siRNAs specific for the bacterial neomycin phosphotransferase II (NPTII) and did not observe an effect.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the anthocyanin biosynthesis pathway. Enzymes of each step are shown in purple. Enzymes involved in general phenylpropanoid pathway are phenylalanine ammonia lyase (PAL), cinnamate 4-hydroxylase (C4H) and 4-coumaryol CoA ligase (4CL). Enzymes involved in flavonoid biosynthesis are chalcone synthase (CHS), chalcone isomerase (CHI), flavanone 3-hydroxylase (F3H), flavanone 3′5′-hydroxylase, (F3′5′H) and flavanone 3′-hydroxylase (F3′H). Anthocyanins are synthesized by dihydroflavonol 4-reductase (DFR), synthase (ANS), and UDP-glucose:flavonoid-3-O-glucosyltransferase (UFGT). Two transcriptional factors negatively regulating anthocyanin biosynthesis include a R3-type single-MYB protein (MYBL2) and a NAC-type transcription factor (ANAC032).

2. Results

2.1. AtCHS-Specific Exogenous dsRNAs Downregulate AtCHS mRNA Levels and Anthocyanin Content in Arabidopsis

We used PCR and in vitro transcription protocol to produce dsRNA molecules of the AtCHS gene, encoding the key enzyme in the flavonoid/anthocyanin biosynthesis pathway (Figure 1), and the non-related NPTII bacterial gene, encoding the bacterial neomycin phosphotransferase II enzyme. We synthesized the NPTII-dsRNAs and treated wild-type A. thaliana to verify whether any observed effects on AtCHS mRNA levels were sequence-specific. To analyze the effect of exogenous dsRNAs on the expression of AtCHS, large fragments of AtCHS and NPTII cDNAs were amplified (Figure 2a,d). Then, the obtained PCR products, containing T7 promoters at both ends, were used as templates for in vitro transcription. For external application, the synthesized dsRNAs were diluted in water to a final concentration of 0.35 µg/µL. The dsRNAs (100 µL of each dsRNA per individual plant, i.e., 35 µg) were applied on the leaf surface (on both the adaxial and abaxial sides) of four-week-old A. thaliana rosettes by spreading with sterile individual soft brushes [31] (Supplementary Video S1). Importantly, we treated the four-week-old rosettes of A. thaliana at a late day time (21:00–21:30) under low soil moisture conditions in all experiments, since the appropriate plant age, late day time, and low soil moisture at the time of dsRNA application were important parameters for successful NPTII suppression in transgenic A. thaliana according to our recent analysis [31]. An analysis of the dsRNA concentration effect on transgene silencing in A. thaliana was performed previously [30], indicating that 35 µg of a transgene-encoding dsRNA resulted in the highest transgene silencing efficiency as compared to other dsRNA concentrations.

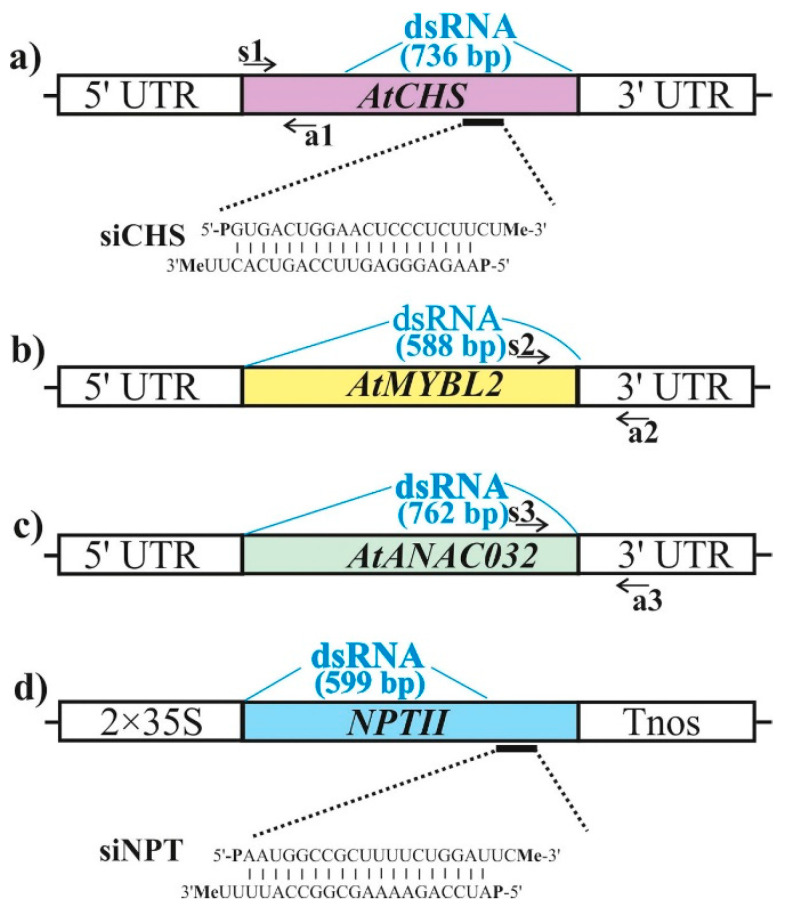

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the dsRNA position and siRNAs structures used in this study and the qRT-PCR primers designed to verify the effects of external RNA treatments on the levels of endogenous AtCHS, AtMYBL2, and AtANAC032 mRNAs. (a) Representation of AtCHS cDNA coding region with positions of the AtCHS-specific dsRNA and siRNA; (b) representation of AtMYBL2 cDNA coding region with position of the AtMYBL2-specific dsRNA; (c) representation of AtANAC032 cDNA coding region and position of AtANAC032-specific dsRNA; (d) representation of NPTII coding region and positions of the NPTII-specific dsRNA and siRNA. Black arrows indicate positions of the primers (s1, a1, s2, a2, s3, a3) used for amplification of the endogenous AtCHS, AtMYBL2, and AtANAC032 transcripts. UTR—untranslated region. 2 × 35S—the double 35S promoter of the cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV). Tnos—nopaline synthase terminator.

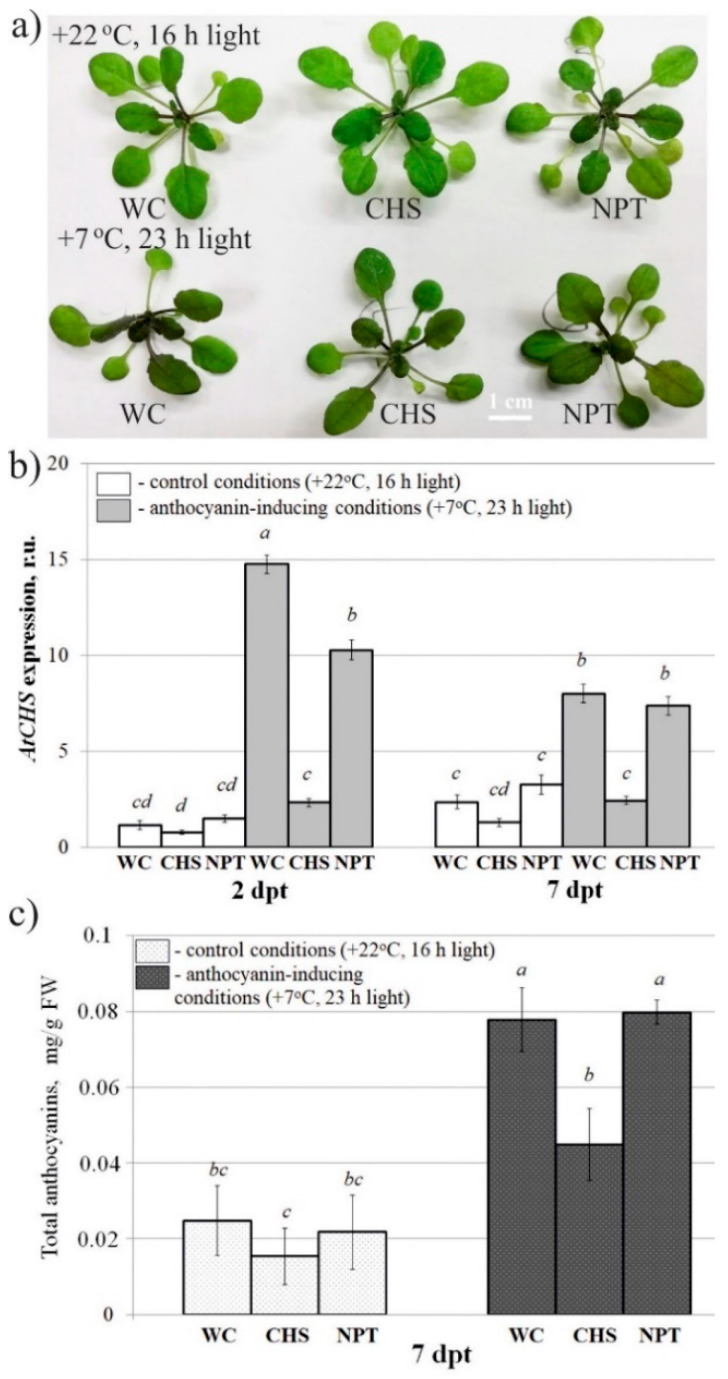

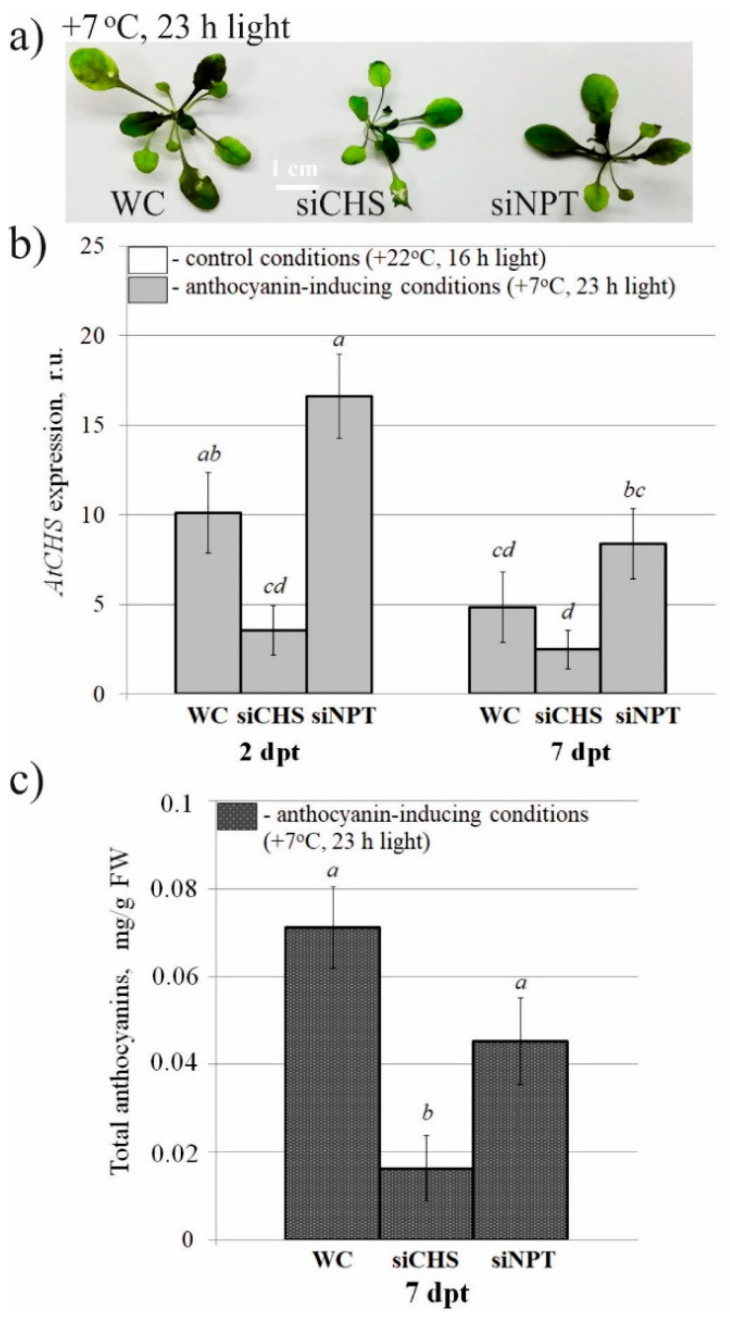

Then, we studied whether exogenous application of the naked AtCHS and NPTII-dsRNAs on the foliar surface of wild-type A. thaliana could led to any changes in the mRNA transcript levels of AtCHS gene and anthocyanin levels in comparison with the control water treatment (Figure 3). Since under standard cultivation conditions anthocyanin production and AtCHS expression were low, we divided the treated A. thaliana rosettes into two groups for post-treatment incubation either under control conditions (+22 °C, 16 h light) or anthocyanin-inducing conditions (+7 °C, and 23 h light) for two and seven days in order to induce AtCHS expression and anthocyanin biosynthesis (Figure 3a). qRT-PCR revealed that cultivation of A. thaliana under the anthocyanin-inducing conditions resulted in a dramatically higher AtCHS mRNA levels in the control plants treated with water and NPTII-dsRNAs than cultivation under control conditions (Figure 3b). Importantly, this AtCHS-induction effect was not observed for plants treated with AtCHS-dsRNAs under the anthocyanin-inducing conditions, at both two days and seven days post-treatment (Figure 3b). Notably, AtCHS mRNA levels were considerably lower in the AtCHS-dsRNA-treated A. thaliana than in the water- and NPTII-treated controls under the anthocyanin-inducing conditions, at both two days and seven days post-treatment.

Figure 3.

The effect of external AtCHS- and NPTII-encoding dsRNAs on AtCHS mRNA level and total anthocyanin content in Arabidopsis thaliana. (a) Arabidopsis plants grown under control (+22 °C, 16 h light, upper panel) and anthocyanin-inducing (+7 °C, 23 h light, lower panel) conditions for seven days after treatment with sterile water or synthetic dsRNA. (b) Quantitative real-time PCR measuring relative mRNA levels of endogenous AtCHS in the leaves of A. thaliana treated with water or synthetic dsRNAs. (c) HPLC results of total anthocyanins in the leaves of A. thaliana grown under the control and anthocyanin-inducing conditions. WC—A. thaliana treated with sterile water; CHS—A. thaliana treated with AtCHS-dsRNAs; NPT—A. thaliana treated with NPTII-dsRNA; dpt—days post-treatment. The data are presented as the mean ± SE (three independent experiments). Means followed by the same letter were not different using Student’s t test. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

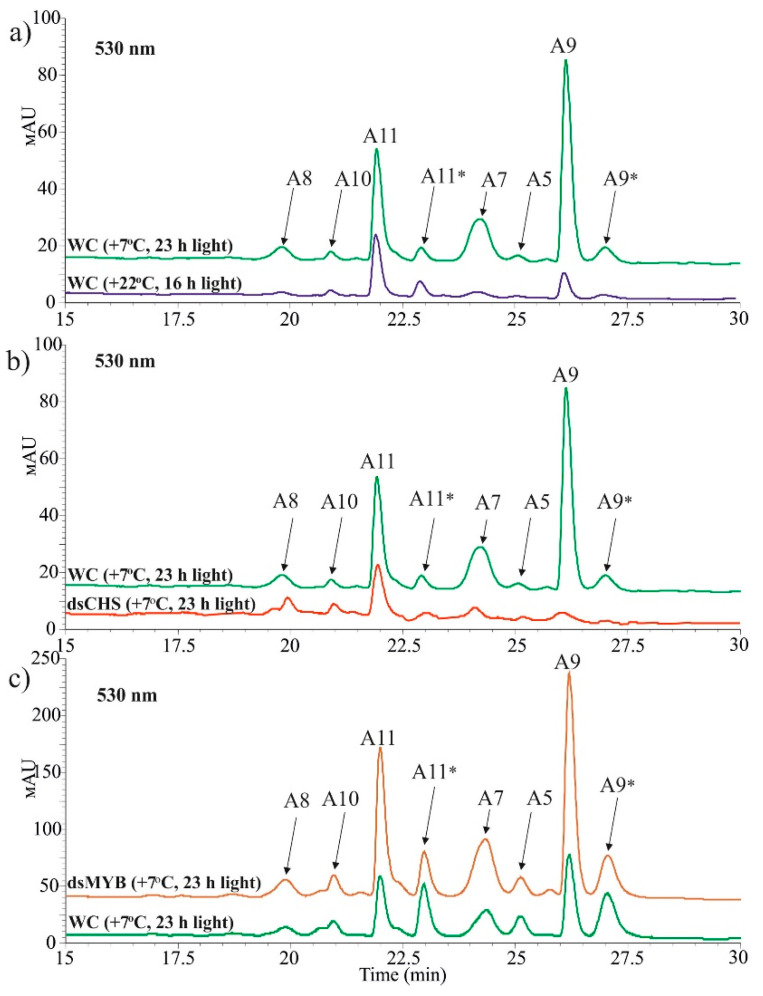

Both HPLC and spectrophotometric analysis of total anthocyanins revealed that plants treated with AtCHS-dsRNAs, but not with NPTII-dsRNAs, exhibited a markedly lower total content of anthocyanins under the anthocyanin-inducing conditions than the water-treated plants (Figure 3c and Figure S1a). Using HPLC with high-resolution mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS), we detected eight anthocyanin compounds in the water- and dsRNA-treated leaves of A. thaliana (Figure 4 and Figure S2a; Table S1). It is possible that other anthocyanins were present in the analyzed tissues of A. thaliana but in trace amounts. The content of most individual anthocyanins was higher in the plants grown under the anthocyanin-inducing conditions than at +22 °C (Figure 4a and Figure S2a). Plant treatment with exogenous AtCHS-dsRNAs reduced the content of all individual anthocyanins, and the changes were statistically significant for A7, A9, and A11* (Figure 4b and Figure S2a).

Figure 4.

HPLC chromatograms of anthocyanins in Arabidopsis thaliana treated with water, AtCHS-dsRNA, or AtMybL2-dsRNA (detected at 530 nm). (a) Induction of anthocyanin production in water-treated plants (WC) under anthocyanin-induction conditions (+7 °C, 23 h light) in comparison with the control (+22 °C, 16 h light); (b) The effect of AtCHS-dsRNA treatment on anthocyanin profiles in A. thaliana; (c) The effect of AtMybL2-dsRNA treatment on anthocyanin profiles in A. thaliana. A8—Cyanidin 3-O-[2′′-O-(xylosyl) 6′′-O-(p-O-(glucosyl) p-coumaroyl) glucoside] 5-O-[6′′′-O-(malonyl) glucoside]. A10—Cyanidin 3-O-[2′′-O-(2′′′-O-(sinapoyl) xylosyl) 6′′-O-(p-O-(glucosyl) p-coumaroyl) glucoside] 5-O-glucoside. A11. Cyanidin 3-O-[2′′-O-(6′′′-O-(sinapoyl) xylosyl) 6′′-O-(p-O-(glucosyl)-p-coumaroyl) glucoside] 5-O-(6′′′′-O-malonyl) glucoside. A7—Cyanidin 3-O-[2′′-O-(2′′′-O-(sinapoyl) xylosyl) 6′′-O-(p-coumaroyl) glucoside] 5-O-glucoside. A5—Cyanidin 3-O-[2′′-O-(xylosyl)-6′′-O-(p-coumaroyl) glucoside] 5-O-malonylglucoside. A9—Cyanidin 3-O-[2′′-O-(2′′′-O-(sinapoyl) xylosyl) 6′′-O-(p-O-coumaroyl) glucoside] 5-O-[6′′′′-O-(malonyl) glucoside]. * — Asterisk indicates a tautomer.

2.2. AtCHS-Specific Exogenous siRNAs Downregulate AtCHS mRNA Levels and Anthocyanin Content in Arabidopsis

Two 21-nt long complimentary single-stranded RNAs (ssCHS-s and ssCHS-a) designed to target the AtCHS mRNAs were in vitro synthesized and HPLC purified (Table S2). In addition, two 21-nt long complimentary single-stranded RNAs (NPTII R3-s-Me and R3-a-Me) designed to target the NPTII mRNAs [34] were in vitro synthesized and HPLC purified (Table S2). The complimentary ssRNAs contained a phosphate group at 5′ end, a 2ʹ-O-methyl at 3′ end, and 2-nt 3′ overhangs at both ends (Figure 2a,d; Table S2). The ssRNAs were combined and annealed to form siRNAs, i.e., siCHS and siNPTII (Figure 2a,d). The NPTII-specific siRNA was included in the study to verify whether any observed effects of AtCHS-siRNA were sequence-specific. In our earlier study, 50 pmol/μL was chosen as the optimal concentration of the NPTII-siRNAs for plant foliar treatments due to the combination of effectiveness and lower cost of ssRNA synthesis [34].

qRT-PCR analysis revealed that the level of AtCHS mRNAs was considerably lower in siCHS-treated plants than in the water- and siNPTII-treated controls grown under the anthocyanin-inducing conditions for two days after the treatments (Figure 5a,b). We noted that the effect became less evident seven days after the treatments. Both HPLC and spectrophotometric analysis of total anthocyanins in the plants cultivated for seven days after the treatments revealed that the siCHS treatment led to a markedly lower anthocyanin content under the anthocyanin-inducing conditions than the water and siNPTII treatments (Figure 5a,c and Figure S1b). siNPTII resulted in the anthocyanin level comparable to that in the water-treated plants. Using HPLC-MS, we also detected eight anthocyanin compounds in the A. thaliana treated with water or siRNAs (Figure S2b; Table S1). The siCHS treatment considerably lowered content of most individual anthocyanins.

Figure 5.

The effect of external AtCHS- and NPTII-encoding siRNAs on AtCHS mRNA level and total anthocyanin content in Arabidopsis thaliana. (a) Arabidopsis plants grown under control (+22 °C, 16 h light, upper panel) and anthocyanin-inducing (+7 °C, 23 h light, lower panel) conditions for seven days after treatment with sterile water or synthetic siRNA. (b) Quantitative real-time PCR measuring relative mRNA levels of endogenous AtCHS in the leaves of A. thaliana treated with water or synthetic siRNAs. (c) HPLC results of the total anthocyanin content in the leaves of A. thaliana grown at the control and anthocyanin-inducing conditions. WC—A. thaliana treated with sterile water; siCHS—A. thaliana treated with synthetic AtCHS-siRNAs; siNPT—A. thaliana treated with NPTII-siRNA; dpt—days post-treatment. The data are presented as the mean ± SE (three independent experiments). Means followed by the same letter were not different using Student’s t test. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

2.3. Targeting AtMYBL2 and ANAC032 Repressors by Foliar dsRNA Treatments Downregulates Their mRNA Levels and Leads to a Pronounced AtCHS Upregulation

We used PCR and in vitro transcription protocol to produce dsRNA molecules of the AtMYBL2 and AtANAC032 genes, encoding transcriptional repressors negatively regulating anthocyanin biosynthesis in A. thaliana [50,51]. Full-length coding cDNAs of the AtMYBL2 and AtANAC032 genes were amplified (Figure 2b,c). The obtained PCR products, containing T7 promoters at both ends, were used as templates for in vitro transcription. For external plant treatments, the synthesized dsRNAs were diluted and applied on the leaf surface (on both the adaxial and abaxial sides) of four-week-old wild type Arabidopsis, as described above for AtCHS-dsRNA. At the same time, we treated A. thaliana with NPTII-dsRNA to verify whether any observed effects of the dsRNAs were sequence-specific.

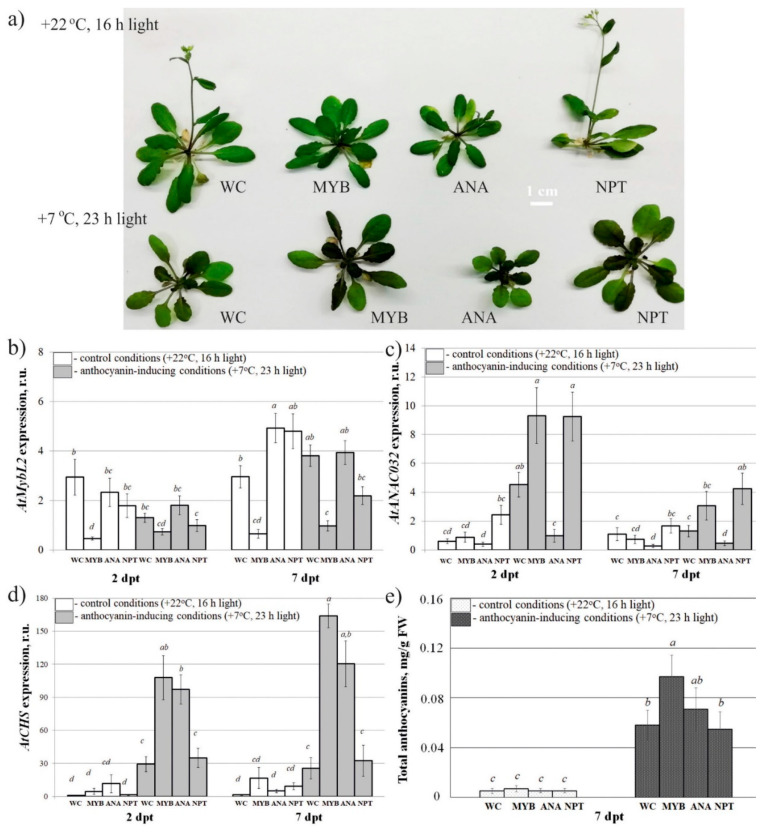

Then, we studied whether simple exogenous application of the AtMYBL2-, AtANAC032-, and NPTII-dsRNAs to the foliar surface of four-week-old A. thaliana could lead to any changes in the mRNA transcript levels of AtMYBL2, AtANAC032, and AtCHS genes in comparison with the water-treated controls two and seven days post-treatments (Figure 6a). For this purpose, we also divided the treated A. thaliana rosettes into two groups for incubation under control conditions (+22 °C, 16 h light) and anthocyanin-inducing conditions (+7 °C, 23 h light). Foliar plant treatment with the AtMYBL2-dsRNAs triggered considerable downregulation of AtMYBL2 mRNA levels both under standard and anthocyanin-inducing conditions (Figure 6b). AtMYBL2 transcript levels were significantly reduced two and seven days post-treatment at +22 °C and seven days post-treatment at +7 °C. Exogenous application of AtANAC032-dsRNA also resulted in a pronounced inhibition of AtANAC032 mRNA levels, especially under the anthocyanin-inducing conditions (Figure 6c). Further analysis revealed a dramatic upregulation of AtCHS expression after application of both AtMYBL2- and AtANAC032-dsRNAs (Figure 6d). However, the dsRNA-induced effect on anthocyanin accumulation was not as evident as that for gene transcript levels (Figure 6e and Figure S1c). While the AtMYBL2- and AtANAC032-dsRNA treatments led to a 3.3-6.4-fold upregulation of AtCHSs, the total content of anthocyanins was considerably increased only after foliar treatment with AtMYBL2 and by 1.7-fold (Figure 6d,e). HPLC analysis of individual anthocyanins revealed a statistically considerable increase in the content of A8, A11, and A9 after treatment with AtMYBL2-dsRNA (Figure S2c). Importantly, exogenous application of NPTII-dsRNA did not have a marked effect on the AtMYBL2, AtANAC032, or AtCHS mRNA levels.

Figure 6.

The effect of external AtMYBL2-, AtANAC032-, and NPTII-encoding dsRNAs on AtMYBL2, AtANAC032, and AtCHS mRNA levels and total anthocyanin content in Arabidopsis thaliana. (a) Arabidopsis plants grown under control (+22 °C, 16 h light, upper panel) and anthocyanin-inducing (+7 °C, 23 h light, lower panel) conditions for seven days after treatment with sterile water or synthetic dsRNAs. (b) Quantitative real-time PCR measuring relative mRNA levels of endogenous AtMYBL2 in the leaves of A. thaliana treated with water or synthetic dsRNAs. (c) Quantitative real-time PCR measuring relative mRNA levels of endogenous AtANAC032 in the leaves of A. thaliana treated with water or synthetic dsRNAs. (d) Quantitative real-time PCR measuring relative mRNA levels of endogenous AtCHS in the leaves of A. thaliana treated with water or synthetic dsRNAs. (e) HPLC results of the total anthocyanin content in the leaves of A. thaliana grown at the control and anthocyanin-inducing conditions. WC—A. thaliana treated with sterile water; MYB—A. thaliana treated with AtMYBL2-dsRNAs; ANA—A. thaliana treated with AtANAC032-dsRNAs; NPT—A. thaliana treated with NPTII-dsRNA; dpt—days post-treatment. The data are presented as the mean ± SE (three independent experiments). Means followed by the same letter were not different using Student’s t test. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

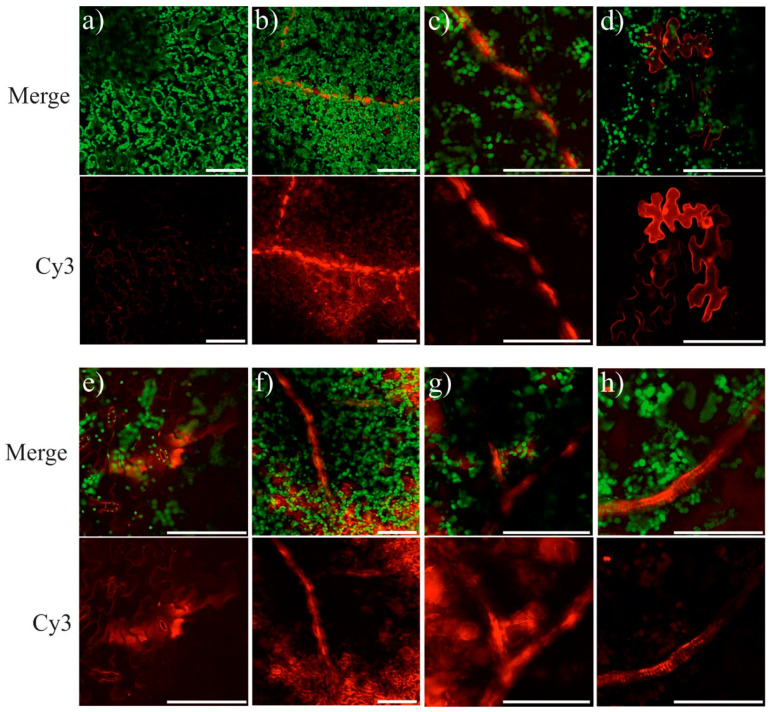

2.4. Detection of AtCHS-dsRNA in A. thaliana Leaves by Laser Scanning Microscopy

To further investigate localization and transport of the exogenous dsRNAs, we labeled the in vitro synthesized AtCHS-dsRNAs with the Cy3 dye and applied to the adaxial and abaxial foliar surface of four-week-old A. thaliana rosettes at 21:00 at a concentration of 0.35 µg/µL [31] by spreading with sterile individual soft brushes. Linear unmixing of the λ-stacks revealed two peaks of fluorescence, including a peak at ≈570 nm–580 nm and a peak at ≈690 nm (Figure S3). The peak at 570 nm–580 nm corresponds to Cy3 (Silencer™ siRNA Labeling Kit with Cy™3 dye), and the peak at 690 nm—chlorophyll fluorescence [52]. Inspection of the adaxial and abaxial leaf surface by laser scanning microscopy 13–15 h post-treatment detected the presence of the Cy3-labeled dsRNA in the leaf veins, parenchyma cells, and stomata of the dsRNA-treated A. thaliana leaves (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Detection of Cy3-labeled AtCHS-dsRNA (red) in the externally treated Arabidopsis thaliana leaves by laser scanning microscopy. Adaxial (a–c) and abaxial (d–h) leaf sides of four-week old A. thaliana were exogenously treated with the labeled AtCHS-dsRNA (red) by sterile soft brushes and analyzed 13–15 h post-treatment. (a) Negative control (sterile water); (b–h)—AtCHS-dsRNA treatment. Green color results from the autofluorescence of chloroplasts. Red color results from the Cy3-labeled dsRNA. Scale bars, 100 μm. Three independent trials showed the same results.

3. Discussion

It is well established that spraying plants with dsRNAs and siRNAs encoding key genes of plant pathogenic fungi [16,17,18,19,20,21] and viruses [22,23,24,25,26,27] effectively reduces development of the pathogens and suppresses the infection process. These externally applied dsRNAs and siRNAs have been shown to spread systemically into plant tissues and were uptaken by the fungal cells inducing a RNAi-mediated silencing of the targeted genes of the pathogens [16,17,21,27]. This strategy of plant disease control was termed as spray-induced gene silencing (SIGS) and is currently considered as an efficient and sustainable plant protection strategy and for other crop improvement strategies [29]. Much less is known about the influence of exogenous dsRNAs/siRNAs on gene silencing in the plant genome. Only four studies [41,42,43,44] and one patent [40] reported on direct plant treatments with naked dsRNA resulting in a reduction of the mRNA levels of a plant endogenous gene target that would also lead to phenotypic or biochemical changes. In addition, two studies reported using nanoparticles [45] or laser light [46] to ensure perception of exogenous dsRNA and downregulation of a plant endogenous gene by external dsRNA application.

We developed our study based on the initial report by Numata et al. [32] who infiltrated A. thaliana leaves with a carrier peptide in a complex with siRNAs encoding the AtCHS gene. Numata et al. [32] reported a local loss of anthocyanin pigmentation by visual observation, but AtCHS mRNA and anthocyanin levels were not analyzed. In our study, we show that foliar application of the gene-specific dsRNAs and siRNAs highly reduced mRNA levels of three anthocyanin biosynthesis-related genes and considerably affected anthocyanin production at both two days and seven days post-treatment. The present study demonstrated that external dsRNA treatments could lead to both gene downregulation (exogenous AtCHS-dsRNAs downregulated AtCHS expression) and gene upregulation (AtMYBL2-dsRNAs and AtANAC032-dsRNAs upregulated AtCHS expression). In all experiments, we treated A. thaliana with NPTII-encoding dsRNAs, which encode a bacterial gene that is not encoded in the genome of wild-type Arabidopsis. In all cases, the foliar-applied unspecific NPTII-dsRNAs had no effect on the expression of the AtCHS, AtMYBL2, and AtANAC032 genes of A. thaliana, which proves that the observed dsRNA-induced gene silencing effect was sequence-specific and was not a result of the dsRNA application itself.

The positive transcriptional regulation of anthocyanin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis and other plants is achieved via a concerted action of a number of transcription factors, involving the MYB–bHLH–WD repeat (MBW) protein complex, which is composed of R2R3-MYB, basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH), and WD40-repeat proteins [53]. As to negative regulation, single repeat R3-MYB transcription factors, including MYBL2, CAPRICE (CPC), TRIPTYCHON (TRY), ENHANCER OF TRY AND CPC 1 (ETC1), and ETC2, were shown to suppress anthocyanin accumulation by interfering with the formation of MBW protein complex [50,53]. In addition, there are other molecular players regulating anthocyanin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis, such as ubiquitin protein ligases or other transcription factors. For example, a NAC transcription factor, ANAC032, that has recently been reported to act as a negative regulator of anthocyanin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana during stress conditions. In our work, we targeted two unrelated transcription repressors, MYBL2 and ANAC032, and verified that the gene-specific dsRNAs downregulated their expression and upregulated AtCHS at the same time. According to our data, both the AtMYBL2- and AtANAC032-dsRNA treatments led to a 3.3-6.4-fold upregulation of AtCHS expression, while the total content of anthocyanins was considerably increased only after foliar treatment with AtMYBL2 and by 1.7-fold. We propose that since there is a plethora of transcriptional regulators implicated in the regulation of anthocyanin biosynthesis, the resulting elevation of anthocyanin production after targeting only two of them was not dramatic.

In summary, our results demonstrate a high potential of exogenous dsRNAs for regulating plant endogenous genes due to a pronounced sequence-specific gene downregulation effect. Furthermore, external plant treatments with gene-specific dsRNAs were capable of inducing the desired phenotypic and biochemical effects. Taken together, the findings reveal that exogenous RNAs can be exploited by plant biologists for further crop improvement and for fundamental gene functional studies.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material and Growth Conditions

The seeds of wild-type A. thaliana (cv. Columbia) were vapor-phase sterilized as described [34] and plated on solid ½ Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium for two days at 4 °C. Then, the plates were kept at 22 °C for 1 week in a growth chamber (Sanyo MLR-352, Panasonic, Osaka, Japan) at a light intensity of ~120 μmol m−2 s−1 over a 16 h daily light period. One-week-old A. thaliana seedlings were planted to pots (7 cm × 7 cm) containing 100 g of commercially available rich soil (the soil was well-irrigated by filtered water applied at the bottom of the pots). Then, the plants were grown in the chamber at 22 °C under plastic wrap for additional three weeks without additional irrigation before RNA treatments of four-week-old plants. After the RNA treatments, the A. thaliana was incubated for additional seven days either under control (+22 °C, 16 h daily light period) or anthocyanin-inducing (+7 °C, 23 h daily light period) conditions in a growth chamber (KS-200, Smolenskoye SKTB SPU, Smolensk, Russia) without further irrigation to induce AtCHS expression and anthocyanin accumulation.

4.2. Isolation and Sequencing of AtCHS, AtMybL2, and AtANACO323 Transcripts

Full-length coding cDNA sequences of AtCHS (AT5G13930.1, 1188 bp) AtMYBL2 (AT1G71030.1, 588 bp), and AtANAC032 (AT1G77450, 762 bp) were amplified by RT-PCR using RNA samples extracted from the adult leaves of A. thaliana. The RT-PCRs were performed in a Bis-M1105 Thermal Cycler (Bis-N, Novosibirsk, Russia). The primers are listed in Table S3. The RT-PCR products were subcloned into pJET1.2/blunt and sequenced as described previously [54].

4.3. dsRNA Synthesis and Application

All dsRNAs were synthesized using the T7 RiboMAX™ Express RNAi System (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). For this purpose, the cloned full-length cDNAs of AtMYBL2 and AtANAC032 and a large cDNA fragment of AtCHS (736 bp out of 1188 bp) were amplified by PCR for in vitro transcription and dsRNA production. We also amplified a large fragment of NPTII (GenBank AJ414108, 599 bp out of 798 bp) using pZP-RCS2-nptII plasmid [55]. The T7 promoter sequence was introduced into both the 5′ and 3′ ends of the amplified AtCHS, AtMYBL2, AtANAC032, or NPTII in a single PCR for each gene using primers listed in Table S3. The PCRs were performed in the Bis-M1105 Thermal Cycler programmed according to T7 RiboMAX™ Express RNAi System instructions. Then, the obtained PCR products were used as templates for in vitro transcription and dsRNA synthesis following the manufacturer’s protocol. The resultant dsRNAs were analyzed by gel electrophoresis and spectrophotometry to estimate dsRNA purity, integrity, and amount.

The AtCHS-, AtMYBL2-, AtANAC032-, and NPTII-dsRNAs were applied to individual four-week-old rosettes of wild-type A. thaliana by spreading with individual soft brushes (natural pony hair) sterilized by autoclaving [31] (Supplementary Video S1). For each dsRNA treatment, 35 µg of the dsRNA were diluted in 100 µL of nuclease-free water and applied to the foliar surface (all leaves of one rosette for each type of condition were treated on both the adaxial (upper) and abaxial (lower) sides). One plant of A. thaliana was treated with the dsRNA of each type (100 µL) and one plant—with sterile filtered water (100 µL) in each independent experiment. The dsRNAs in all experiments were applied to four-week-old rosettes of A. thaliana at a late day time (21:00–21:30) under low soil moisture conditions, since the appropriate plant age, late day time, and low soil moisture at the time of dsRNA application were important parameters for successful NPTII suppression in transgenic A. thaliana according to our recent analysis [31]. Soil water content before dsRNA treatment was 50–60%.

4.4. siRNA Synthesis and Application

The AtCHS- and NPTII-encoding ssRNAs were in vitro-synthesized, modified, and HPLC purified by Syntol (Moscow, Russia). The RNA oligonucleotide sequences are presented in Table S2 and Figure 2a,d. The synthesized single-stranded oligonucleotides were prepared to form siRNA as described [34]. Briefly, to form the siRNA duplexes, equal volumes of the ssRNAs diluted to a concentration of 100 pmol/µL were combined and annealed at 90 °C for 1 min. Then, the mixture was slowly cooled to room temperature. The final concentration of annealed oligonucleotides was 50 pmol/µL. 100 µL of each siRNA duplex or 100 µL of nuclease-free water were applied onto the leaf surface of four-week-old A. thaliana by spreading with individual soft brushes as described above for dsRNA.

4.5. RNA Isolation and Reverse Transcription

For RNA isolations, a typical adult leaf of A. thaliana was collected from the same individual plant before treatment, two days and seven days post-treatment for each type of treatment in an independent experiment. Total RNA was isolated using the cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB)-based protocol [56] and complementary DNAs were synthesized as described [57].

4.6. Gene Expression Analysis by qRT-PCR

The reverse transcription products were amplified by PCR and verified for the absence of DNA contamination, using primers listed in Table S3. The qRT-PCRs were performed with SYBR Green I Real-time PCR dye and a real-time PCR kit (Evrogen, Moscow, Russia) as described [58] using two internal controls (GAPDH and UBQ) selected in previous studies as relevant reference genes for qRT-PCRs on Arabidopsis [59]. The expression was calculated by the 2−ΔΔCT method [60]. All gene identification numbers and used primers are listed in Table S3.

4.7. Quantification of Anthocyanins

Anthocyanin content in A. thaliana rosettes was determined using a SPECTROstar Nano spectrophotometer (BMG Labtech, Ortenberg, Germany) as described in Teng et al. [61]. Treated A. thaliana rosettes were frozen at −20 °C and subsequently homogenized using a mortar and a pestle. Shredded tissue was weighed and extracted for 1 d at 4 °C in 1 mL of 1% (v/v) hydrochloric acid in methanol. Then, the mixture was centrifuged at 13,200 rpm for 15 min and the absorbance of the supernatant was measured at 530 and 657 nm. Relative anthocyanin concentrations were calculated as described [61].

For HPLC–MS analysis, the samples were filtered through a 0.45-um nylon filter. Identification of all anthocyanins was performed using a 1260 Infinity analytical HPLC system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) coupled to Bruker HCT ultra PTM Discovery System (Bruker Daltonik GmbH, Bremen, Germany) equipped with an electrospray ionization (ESI) source. The data for anthocyanins were acquired in positive ion mode under the operating conditions as described [62]. The MS spectra were recorded across an m/z range of 100–1500, and the individual anthocyanins were identified as described [63].

HPLC with diode array detection (HPLC–DAD) for quantification of all anthocyanins was performed using a HPLC LC-20AD XR analytical system (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). DAD data were recorded in the 200–800 nm range, and chromatograms for quantification were acquired at 530 nm. The chromatographic separation was performed on Shim-pack GIST C18 column (150 mm, 2.1-nm i.d., 3-µm part size; Shimadzu, Japan). Anthocyanins were separated using 0.1% formic acid and acetonitrile as mobile phases A and B, respectively, with the following elution profile: 0 to 35 min 0% of B; 35 to 40 min 40% of B; 40 to 50 min 50% of B; 50 to 65 min 100% of B. 5 μL of the sample extract was injected with a constant column temperature maintained at 40 °C and a flow rate maintained at 0.2 mL/min. All solvents were of HPLC grade. The contents of anthocyanins were determined by external standard method using the four-point regression calibration curves built with the available standards. The commercial standard cyanidin chloride was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) and used as the control.

4.8. Fluorescent dsRNA Labeling and Laser Scanning Microscopy

Fluorescent labeling of the in vitro synthesized AtCHS-dsRNA was performed using the Silencer™ siRNA Labeling Kit with Cy™3 dye (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. A total of 35 µg of the labeled dsRNA (100 µL) was applied on the adaxial and abaxial leaf surface of four-week A. thaliana as described above. Fluorescent signals were analyzed 13–15 h after the foliar plant treatments by laser scanning microscopy. The whole leaves were mounted in distilled water in a Petri dish and were observed under a Zeiss LSM 780 laser scanning microscope operated in λ-mode equipped with a Plan-Apochromat 20×/0.8 and a Plan-Neofluar 40×/0.6 objectives. The excitation wavelength of an argon laser was set at 488 nm and the emission signal was registered at 20 evenly spaced wavelengths (8.9 nm apart) in a range from 500 to 693 nm by using a QUASAR detector. Finally, the resulted λ-stacks were linearly unmixed with the Zeiss Zen 2.1 SP3 (Black Edition) software. The laser scanning microscopy was carried out at the Far Eastern Center of Electron Microscopy (A.V. Zhirmunsky National Scientific Center of Marine Biology, FEB RAS, Vladivostok, Russia).

4.9. Statistical Analysis

The data are presented as mean ± standard error (SE) and were tested by paired Student’s t-test. The p < 0.05 level was selected as the point of minimal statistical significance in all analyses. At least three independent experiments were performed for each type of analysis.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Materials can be found at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijms22136749/s1.

Author Contributions

A.S.D. and K.V.K. performed the research design, experimental treatments, RNA isolations, reverse transcription, data analysis, and paper preparation. A.R.S., O.A.A. and Z.V.O. were involved in plant management, experimental treatments, RNA isolation, reverse transcription, and performed qRT-PCRs. A.R.S. performed HPLC-MS analysis. A.V.K. performed laser-scanning microscopy. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was fully supported by the Russian Science Foundation (19-74-10023).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available within the article and Supplementary Materials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Kamthan A., Chaudhuri A., Kamthan M., Datta A. Small RNAs in plants: Recent development and application for crop improvement. Front. Plant Sci. 2015;6:208. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosa C., Kuo Y.W., Wuriyanghan H., Falk B.W. RNA interference mechanisms and applications in plant pathology. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2018;56:581–610. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-080417-050044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borges F., Martienssen R.A. The expanding world of small RNAs in plants. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2015;507:727–741. doi: 10.1038/nrm4085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilson R.C., Doudna J.A. Molecular mechanisms of RNA interference. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2013;42:217–239. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-083012-130404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Korner C.J., Pitzalis N., Pena E.J., Erhardt M., Vazquez F., Heinlein M. Crosstalk between PTGS and TGS pathways in natural antiviral immunity and disease recovery. Nat. Plants. 2018;4:157–164. doi: 10.1038/s41477-018-0117-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh A., Gautam V., Singh S., Sarkar Das S., Verma S., Mishra V., Mukherjee S., Sarkar A.K. Plant small RNAs: Advancement in the understanding of biogenesis and role in plant development. Planta. 2018;248:545–558. doi: 10.1007/s00425-018-2927-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guleria P., Mahajan M., Bhardwaj J., Yadav S.K. Plant small RNAs: Biogenesis, mode of action and their roles in abiotic stresses. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2011;6:183–199. doi: 10.1016/S1672-0229(11)60022-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morozov S.Y., Solovyev A.G., Kalinina N.O., Taliansky M.E. Double-stranded RNAs in plant protection against pathogenic organisms and viruses in agriculture. Acta Nat. 2019;11:13–21. doi: 10.32607/20758251-2019-11-4-13-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gebremichael D.E., Haile Z.M., Negrini F., Sabbadini S., Capriotti L., Mezzetti B., Baraldi E. RNA Interference Strategies for Future Management of Plant Pathogenic Fungi: Prospects and Challenges. Plants. 2021;10:650. doi: 10.3390/plants10040650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koch A., Wassenegger M. Host-induced gene silencing-mechanisms and applications. New Phytol. 2021 doi: 10.1111/nph.17364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramegowda V., Mysore K.S., Senthil-Kumar M. Virus-induced gene silencing is a versatile tool for unraveling the functional relevance of multiple abiotic-stress-responsive genes in crop plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2014;5:323. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mamta B., Rajam M.V. RNAi technology: A new platform for crop pest control. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants. 2017;3:487–501. doi: 10.1007/s12298-017-0443-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Santos D., Remans S., Van den Brande S., Vanden Broeck J. RNAs on the go: Extracellular transfer in insects with promising prospects for pest management. Plants. 2021;10:484. doi: 10.3390/plants10030484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Key S., Ma J.K., Drake P.M. Genetically modified plants and human health. J. R. Soc. Med. 2008;101:290–298. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.2008.070372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Unver T., Budak H. Virus-induced gene silencing, a post transcriptional gene silencing method. Int. J. Plant Genom. 2009;2009:198680. doi: 10.1155/2009/198680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang M., Weiberg A., Lin F.M., Thomma B.P.H.J., Huang H.D., Jin H.L. Bidirectional cross-kingdom RNAi and fungal uptake of external RNAs confer plant protection. Nat. Plants. 2016;2:16151. doi: 10.1038/nplants.2016.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koch A., Biedenkopf D., Furch A., Weber L., Rossbach O., Abdellatef E., Linicus L., Johannsmeier J., Jelonek L., Goesmann A., et al. An RNAi-based control of Fusarium graminearum infections through spraying of long dsRNAs involves a plant passage and is controlled by the fungal silencing machinery. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12:e1005901. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McLoughlin A.G., Wytinck N., Walker P.L., Girard I.J., Rashid K.Y., de Kievit T., Fernando W.G.D., Whyard S., Belmonte M.F. Identification and application of exogenous dsRNA confers plant protection against Sclerotinia sclerotiorum and Botrytis cinerea. Sci. Rep. 2018;9:7320. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-25434-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Song X.S., Gu K.X., Duan X.X., Xiao X.M., Hou Y.P., Duan Y.B., Wang J.X., Zhou M.G. A myosin5 dsRNA that reduces the fungicide resistance and pathogenicity of Fusarium asiaticum. Pest. Biochem. Physiol. 2018;150:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pestbp.2018.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Werner B.T., Gaffar F.Y., Schuemann J., Biedenkopf D., Koch A.M. RNA-spray-mediated silencing of Fusarium graminearum AGO and DCL genes improve barley disease resistance. Front. Plant Sci. 2020;11:476. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.00476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qiao L., Lan C., Capriotti L., Ah-Fong A., Nino Sanchez J., Hamby R., Heller J., Zhao H., Glass N.L., Judelson H.S., et al. Spray-induced gene silencing for disease control is dependent on the efficiency of pathogen RNA uptake. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2021 doi: 10.1111/pbi.13589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mitter N., Worrall E.A., Robinson K.E., Li P., Jain R.G., Taochy C., Fletcher S.J., Carroll B.J., Lu G.Q., Xu Z.P. Clay nanosheets for topical delivery of RNAi for sustained protection against plant viruses. Nat. Plants. 2017;3:16207. doi: 10.1038/nplants.2016.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaldis A., Berbati M., Melita O., Reppa C., Holeva M., Otten P., Voloudakis A. Exogenously applied dsRNA molecules deriving from the Zucchini yellow mosaic virus (ZYMV) genome move systemically and protect cucurbits against ZYMV. Mol. Plant. Pathol. 2018;19:883–895. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Worrall E.A., Bravo-Cazar A., Nilon A.T., Fletcher S.J., Robinson K.E., Carr J.P., Mitter N. Exogenous application of RNAi-inducing double-stranded RNA inhibits aphid-mediated transmission of a plant virus. Front. Plant Sci. 2019;10:265. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.00265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vadlamudi T., Patil B.L., Kaldis A., Gopal D.V.R.S., Mishra R., Berbati M., Voloudakis A. DsRNA-mediated protection against two isolates of Papaya ringspot virus through topical application of dsRNA in papaya. J. Virol. Methods. 2020;275:113750. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2019.113750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holeva M.C., Sklavounos A., Rajeswaran R., Pooggin M.M., Voloudakis A.E. Topical application of double-stranded RNA targeting 2b and CP genes of Cucumber mosaic virus Protects Plants against Local and Systemic Viral Infection. Plants. 2021;10:963. doi: 10.3390/plants10050963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Necira K., Makki M., Sanz-García E., Canto T., Djilani-Khouadja F., Tenllado F. Topical application of Escherichia coli-encapsulated dsRNA induces resistance in Nicotiana benthamiana to potato viruses and involves RDR6 and combined activities of DCL2 and DCL4. Plants. 2021;10:644. doi: 10.3390/plants10040644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dubrovina A.S., Kiselev K.V. Exogenous RNAs for gene regulation and plant resistance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20:2282. doi: 10.3390/ijms20092282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang M., Jin H. Spray-induced gene silencing: A powerful innovative strategy for crop protection. Trends Microbiol. 2017;25:4–6. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2016.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dubrovina A.S., Aleynova O.A., Kalachev A.V., Suprun A.R., Ogneva Z.V., Kiselev K.V. Induction of transgene suppression in plants via external application of synthetic dsRNA. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20:1585. doi: 10.3390/ijms20071585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kiselev K.V., Suprun A.R., Aleynova O.A., Ogneva Z.V., Dubrovina A.S. Physiological Conditions and dsRNA Application Approaches for Exogenously induced RNA Interference in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plants. 2021;10:264. doi: 10.3390/plants10020264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Numata K., Ohtani M., Yoshizumi T., Demura T., Kodama Y. Local gene silencing in plants via synthetic dsRNA and carrier peptide. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2014;12:1027–1034. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dalakouras A., Wassenegger M., McMillan J.N., Cardoza V., Maegele I., Dadami E., Runne M., Krczal G., Wassenegger M. Induction of silencing in plants by high-pressure spraying of in vitro-synthesized small RNAs. Front. Plant Sci. 2016;7:1327. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dubrovina A.S., Aleynova O.A., Suprun A.R., Ogneva Z.V., Kiselev K.V. Transgene suppression in plants by foliar application of in vitro-synthesized small interfering RNAs. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020;104:2125–2135. doi: 10.1007/s00253-020-10355-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vermeersch L., De Winne N., Depicker A. Introns reduce transitivity proportionally to their length, suggesting that silencing spreads along the pre-mRNA. Plant J. 2010;64:392–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04335.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dadami E., Moser M., Zwiebel M., Krczal G., Wassenegger M., Dalakouras A. An endogene-resembling transgene delays the onset of silencing and limits siRNA accumulation. FEBS Lett. 2013;18:706–710. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.01.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dadami E., Dalakouras A., Zwiebel M., Krczal G., Wassenegger M. An endogene-resembling transgene is resistant to DNA methylation and systemic silencing. RNA Biol. 2014;11:934–941. doi: 10.4161/rna.29623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dalakouras A., Jarausch W., Buchholz G., Bassler A., Braun M., Manthey T., Krczal G., Wassenegger M. Delivery of hairpin RNAs and small RNAs into woody and herbaceous plants by trunk injection and petiole absorption. Front. Plant Sci. 2018;9:1253. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.01253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Uslu V.V., Bassler A., Krczal G., Wassenegger M. High-pressure-sprayed double stranded RNA does not induce RNA interference of a reporter gene. Front. Plant Sci. 2020;11:534391. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.534391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sammons R., Ivashuta S., Liu H., Wang D., Feng P., Kouranov A., Andersen S. Polynucleotide Molecules for Gene Regulation in Plants. 20110296556 A1. U.S. Patent. 2011 Dec 1;

- 41.Lau S.E., Schwarzacher T., Othman R.Y., Harikrishna J.A. dsRNA silencing of an R2R3-MYB transcription factor affects flower cell shape in a Dendrobium hybrid. BMC Plant Biol. 2015;15:194. doi: 10.1186/s12870-015-0577-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li H., Guan R., Guo H., Miao X. New insights into an RNAi approach for plant defence against piercing-sucking and stem-borer insect pests. Plant Cell Environ. 2015;38:2277–2285. doi: 10.1111/pce.12546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Warnock N.D., Wilson L., Canet-Perez J.V., Fleming T., Fleming C.C., Maule A.G., Dalzell J.J. Exogenous RNA interfer-ence exposes contrasting roles for sugar exudation in host-finding by plant pathogens. Int. J. Parasitol. 2016;46:473–477. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2016.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marcianò D., Ricciardi V., Fassolo E.M., Passera A., BIANCO P.A., Failla O., Casati P., Maddalena G., De Lorenzis G., Toffolatti S.L. RNAi of a putative grapevine susceptibility gene as a possible downy mildew control strategy. Front. Plant Sci. 2021 doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.667319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jiang L., Ding L., He B., Shen J., Xu Z., Yin M., Zhang X. Systemic gene silencing in plants triggered by fluorescent na-noparticle-delivered double-stranded RNA. Nanoscale. 2014;6:9965–9969. doi: 10.1039/C4NR03481C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Killiny N., Gonzalez-Blanco P., Gowda S., Martini X., Etxeberria E. Plant functional genomics in a few days: Laser-assisted delivery of double-stranded RNA to higher plants. Plants. 2021;10:93. doi: 10.3390/plants10010093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kong J.M., Chia L.S., Goh N.K., Chia T.F., Brouillard R. Analysis and biological activities of anthocyanins. Phytochemistry. 2003;64:923–933. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(03)00438-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chaves-Silva S., Dos Santos A.L., Chalfun-Júnior A., Zhao J., Peres L.E.P., Benedito V.A. Understanding the genetic regulation of anthocyanin biosynthesis in plants—Tools for breeding purple varieties of fruits and vegetables. Phytochemistry. 2018;153:11–27. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2018.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mattioli R., Francioso A., Mosca L., Silva P. Anthocyanins: A comprehensive review of their chemical properties and health effects on cardiovascular and neurodegenerative diseases. Molecules. 2020;25:3809. doi: 10.3390/molecules25173809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Matsui K., Umemura Y., Ohme-Takagi M. AtMYBL2, a protein with a single MYB domain, acts as a negative regulator of anthocyanin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2008;55:954–967. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mahmood K., Xu Z., El-Kereamy A., Casaretto J.A., Rothstein S.J. The Arabidopsis transcription factor ANAC032 represses anthocyanin biosynthesis in response to high sucrose and oxidative and abiotic stresses. Front. Plant Sci. 2016;7:1548. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pedros R., Moya I., Goulas Y., Jacquemoud S. Chlorophyll fluorescence emission spectrum inside a leaf. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2008;7:498–502. doi: 10.1039/b719506k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li S. Transcriptional control of flavonoid biosynthesis. Plant Signal. Behav. 2014;9:e27522. doi: 10.4161/psb.27522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dubrovina A.S., Aleynova O.A., Ogneva Z.V., Suprun A.R., Ananev A.A., Kiselev K.V. The effect of abiotic stress conditions on expression of calmodulin (CaM) and calmodulin-like (CML) genes in wild-growing grapevine Vitis amurensis. Plants. 2019;8:602. doi: 10.3390/plants8120602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tzfira T., Tian G.W., Lacroix B., Vyas S., Li J., Leitner-Dagan Y., Krichevsky A., Taylor T., Vainstein A., Citovsky V. pSAT vectors: A modular series of plasmids for autofluorescent protein tagging and expression of multiple genes in plants. Plant Mol. Biol. 2005;57:503–516. doi: 10.1007/s11103-005-0340-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kiselev K.V., Dubrovina A.S., Shumakova O.A., Karetin Y.A., Manyakhin A.Y. Structure and expression profiling of a novel calcium-dependent protein kinase gene, CDPK3a, in leaves, stems, grapes, and cell cultures of wild-growing grapevine Vitis amurensis Rupr. Plant Cell Rep. 2013;32:431–442. doi: 10.1007/s00299-012-1375-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Aleynova O.A., Kiselev K.V., Ogneva Z.V., Dubrovina A.S. The grapevine calmodulin-like protein gene CML21 is regulated by alternative splicing and involved in abiotic stress response. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21:7939. doi: 10.3390/ijms21217939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dubrovina A.S., Kiselev K.V. The role of calcium-dependent protein kinase genes VaCPK1 and VaCPK26 in the response of Vitis amurensis (in vitro) and Arabidopsis thaliana (in vivo) to abiotic stresses. Russ. J. Genet. 2019;55:319–329. doi: 10.1134/S1022795419030049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Czechowski T., Stitt M., Altmann T., Udvardi M.K., Scheible W.R. Genome-wide identification and testing of superior reference genes for transcript normalization in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2005;139:5–17. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.063743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Livak K.J., Schmittgen T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Teng S., Keurentjes J., Bentsink L., Koornneef M., Smeekens S. Sucrose-specific induction of anthocyanin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis requires the MYB75/PAP1 gene. Plant Physiol. 2005;139:1840–1852. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.066688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Abdullin S.R., Nikulin V.Y., Nikulin A.Y., Manyakhin A.Y., Bagmet V.B., Suprun A.R., Gontcharov A.A. Roholtiella mixta sp. nov. (Nostocales, Cyanobacteria): Morphology, molecular phylogeny, and carotenoid content. Phycologia. 2021;60:73–82. doi: 10.1080/00318884.2020.1852846. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tohge T., Nishiyama Y., Hirai M.Y., Yano M., Nakajima J., Awazuhara M., Inoue E., Takahashi H., Goodenowe D.B., Kitayama M., et al. Functional genomics by integrated analysis of metabolome and transcriptome of Arabidopsis plants over-expressing an MYB transcription factor. Plant J. 2005;42:218–235. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available within the article and Supplementary Materials.