Abstract

The nopal cactus is an essential part of the Mexican diet and culture. The per capita consumption of young cladodes averages annually to 6.4 kg across the nation. In addition to contributing to the country's food culture, the nopal is considered a food with functional characteristics since, in addition to providing fiber, an important group of polyphenolic compounds is present, which has given cladodes to be considered a healthy food, for what they have been incorporated into the diet of Mexican people and many other countries worldwide. Research suggests that polyphenols from cladodes act as antioxidants and antidiabetics. This review studies the main phenolic components in cladodes and summarizes both conventional and novel methods to identify them.

Keywords: analytical methods, cladodes, health effects, hierarchical structure, Opuntia ficus‐indica, polyphenols

This manuscript summarizes the different polyphenols that have been elucidated in the cladodes to which various biological activities with benefits to human health are attributed, as well as the main factors that affect the processes of preparation and extraction.

1. INTRODUCTION

Worldwide, nopal has become a valuable crop due to its health benefits, ease of cultivation, marketing, and climate adaptation (Aruwa et al., 2018). Nopal (Opuntia ficus‐indica (L.) Mill) belongs to the Cactaceae family that comprises about 1,500 species (El‐Mostafa et al., 2014), some of these species are Opuntia: basilaris, chlorotica, engelmannii, fragilis, humifusa, leucotricha, macrocentra, macrorhiza, dillenii, santa‐rita, stricta (Majdoub et al., 2001). Its cultivation represents a major source of income for farmers living in semi‐arid regions (Bayar et al., 2016). Nopal can grow in South America and other dry areas such as Africa, Australia, Southern Europe, and Asia (Khouloud et al., 2018; Majdoub et al., 2001). Nevertheless, Mexico accounts for 90% of the world´s production and represent the largest supplier to the United States, Canada, Japan, and European countries. Per capita consumption of nopal in Mexico is 6.4 kg (FAOSTAT, 2016).

Nopal is one of the most consumed species due to its nutritional value (Majdoub et al., 2001); furthermore, recent trends in healthy food consumption aroused scientists’ interest to study the effects of nopal polyphenolic compounds in oxidative stress‐related diseases (Scalbert et al., 2005). This work describes the nopal as a potential source of polyphenols and the main factors affecting their analytical identification. In addition, we highlight the importance of the relationship structure function in promoting health through cladodes consumption.

2. NOPAL: MORPHOLOGICAL DESCRIPTION

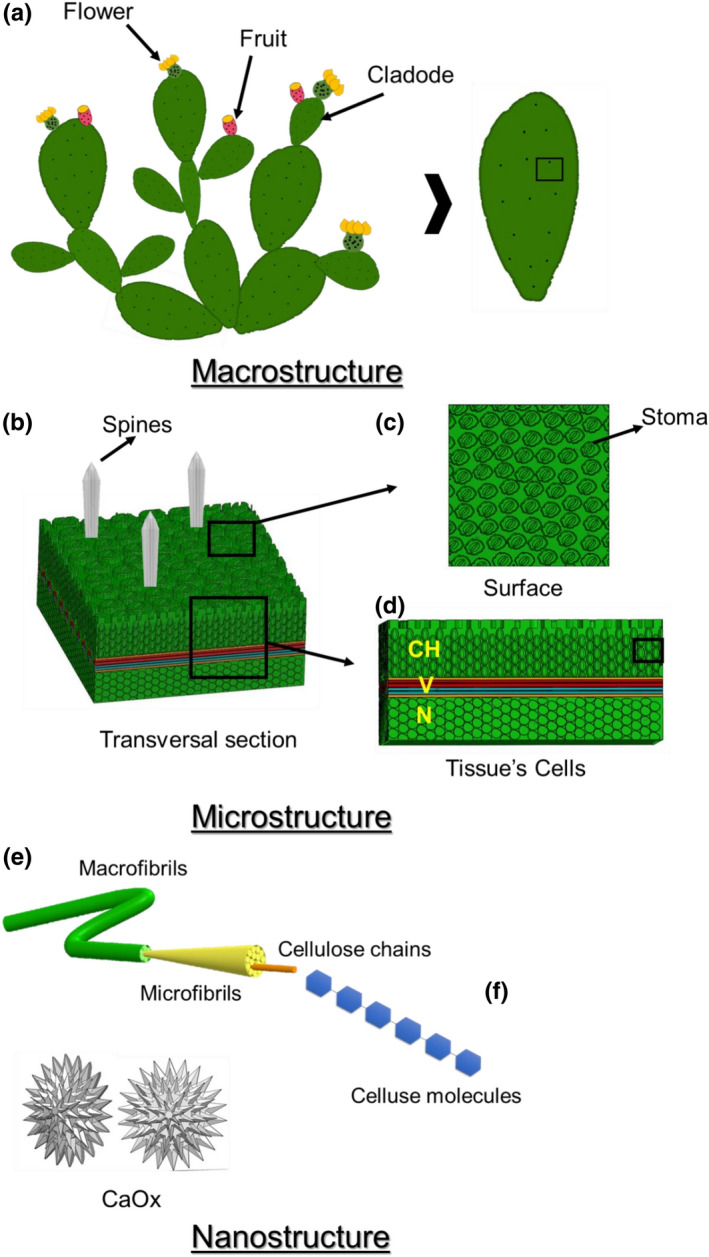

The hierarchical structural organization evaluates the structure functioning at different dimensional scales (macrostructure, microstructure, and nanostructure) (Gibson, 2012). Figure 1 shows a model of the hierarchical structural organization of the nopal, which contributes to its morphological description.

FIGURE 1.

Hierarchical structural organization of nopal

At the first level (macrostructure), nopal has three components which are as follows: flowers, prickly pears fruits, and leaves (botanically called cladodes) (Salehi et al., 2019). The flowers are pear‐shaped, which allows insect pollination (Small & Catling, 2004). The prickly pears are usually ovoid and spherical, often green, yellow, or bright red. They have a high number of seeds, and a protective shell covered with small spines. This gives them an important role in the genetic diversity and distribution of the species (Carrillo et al., 2017).

The leaves or cladodes (Figure 1a) are ovoid or elongated racquet‐shaped, with 30–60 cm in length depending on the water and nutrients available (Ciriminna et al., 2019). In Africa, cladodes are exclusively used for animal feeding (De Albuquerque et al., 2019; Mounir et al., 2020); while in Japan, they are hydroponically cultivated for human consumption (Horibe, 2018), as a medicinal plant for diabetes and hypercholesterolemia (Santos‐Zea et al., 2011). Cladodes have areolas from where flowers, fruits, and thorns grow. One to five large, hard spines, and multiple smaller ones (glochidia) protect cladodes against light reflection, water loss, and herbivores predation (Marin‐Bustamante et al., 2018).

The epidermis (Figure 1b) contains numerous stomata (Figure 1c) that control photosynthesis and respiration (Salem‐Fnayou et al., 2014). An inner tissue called chlorenchyma (CH) constitutes the second hierarchical level (microstructure), which consists of green plastids and abundant starch. The vascular tissue (V) located at the chlorenchyma tissue and the nucleus tissue (N) junction serves as a water and nutrient transporter into the plant, allowing the tissue to function as water storage for long periods of drought (Ginestra et al., 2009). The colorless central core tissue contains reserves of carbohydrates, proteins, and polyphenols (Feugang et al., 2006).

At the third hierarchical level (nanostructure), the macro cellulose fibers provide structure to the cell wall (Figure 1e). Alongside the tissues, calcium oxalate crystals are found (decreasing in content as cladodes mature) making calcium more bioavailable in younger cladodes (Contreras‐Padilla et al., 2016), which are consumed as vegetables in different stages of maturation ranging from 30 to 90 days (Hernandez‐Becerra et al., 2020; Marin‐Bustamante et al., 2018). Finally, on the fourth hierarchical level, we find the cellulose molecular structure (Figure 1f) (Ventura‐Aguilar et al., 2017).

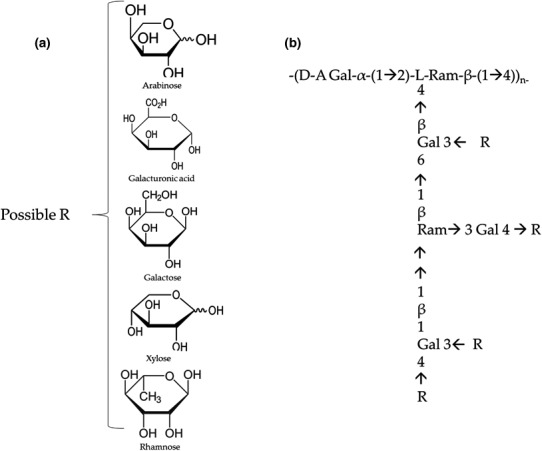

3. CLADODE: COMPOSITION AND BIOLOGICAL ACTIVITY

Cladode chemical composition may vary according to soil factors, cultivation season, and plant age (Table 1). The primary metabolites of cladodes are water, carbohydrates, and proteins. The carbohydrates in cladodes are divided into two types: (a) structural ones that are part of the cell wall, as cellulose (21.6 wt%), hemicelluloses 8.19%, and lignin (3.6 wt%) (López‐Palacios et al., 2016; Scaffaro et al., 2019), and (b) the storage carbohydrates constituted by monosaccharides such as arabinose, galacturonic acid, glucuronic acid, galactose, glucose, xylose, rhamnose, mannose, and fructose (Rodríguez‐González et al., 2014). Polysaccharides from Opuntia ficus‐indica (L.) Mill plants build molecular networks with the capacity to retain water, thus they act as mucoprotective agents (Di Lorenzo et al., 2017). Mucilage is the main polysaccharide of cladodes, it contains polymers of β‐d‐galacturonic acid bound in positions (1–4) and traces of R‐linked l‐rhamnose (1–2) (Figure 2) (Quinzio et al., 2018). Mucilage regulates both the cell water content during prolonged drought and the calcium flux in the plant cells (Hernández‐Urbiola et al., 2010). In the food industry, mucilage is used as an additive, an emulsifier, and an edible coating to extend the shelf life of food products (Medina‐Torres et al., 2013).

TABLE 1.

Chemical composition of nopal cladodes

| Composition (% DW) | Reference | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbohydrates | Proteins | Lipids | Crude fiber | Ash | |

| 42.94 | 7.07 | 2.16 | 7.07 | 17.65 | Hernandez‐Urbiola et al. (2010) |

| — | 11.73 | 1.89 | 55.05 | 23.05 | Cornejo‐Villegas et al. (2010) |

| 61.4 | 6.7 | 0.1 | 15.0 | 17.3 | Guevara‐Fig ueroa et al. (2010) |

| 38.0 | 11.2 | 0.69 | 5.97 | 14.4 | Astello‐García et al. (2015) |

—, No determinate; DW, dry weight.

FIGURE 2.

Structural proposal of the Opuntia ficus‐indica mucilage

Cladodes contain around 6.7%–11.73% of protein (Table 1). Amino acids such as alanine, isoleucine, and asparagine are found in young cladodes, whereas threonine prevails only in mature cladodes (Figueroa‐Pérez et al., 2018). Young cladodes have a higher protein content than mature cladodes, which may be related to the increased metabolic activity in the early stages of maturation (Nuñez‐López et al., 2013). Furthermore, analyses of plant extracts of the Cactaceae family identified several enzymes (e.g., lipases, proteinases, and glucosidases) (Guevara‐Figueroa et al., 2010), and a large content of minerals (23.05%).

Over the years, Mexican people have developed several chronic degenerative diseases such as obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases (Aparicio‐Saguilán et al., 2015). Traditional Mexican medicine recommends consuming cladodes due to their bioactive compounds' effects on health (Table 2); for example, the ability of polyphenols to eliminate free radicals (De Santiago et al. 2019; Filannino et al., 2016; Kim et al., 2016; Petruk et al. 2017).

TABLE 2.

Biological activities reported in cladodes

| Biological activity | Bioactive compound | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Anti‐Inflammatory | Isorhamnetin glycosidesa | Antunes‐Ricardo et al. (2017) |

|

Isorhamnetin conjugatesa Flavonoids |

Antunes‐Ricardo et al. (2015) Filannino et al. (2016) |

|

| Antidiabetic | Flours obtained from different maturity stages | Nuñez‐López et al. (2013) |

| Carbohydrates and leucineb | Deldicque et al. (2013) | |

| Antimicrobial and Antibiofilm Activity | Polyphenolsc | Avila‐Nava et al. (2017) |

| Antioxidants | Polysaccharides | Nuñez‐López et al. (2013) |

| Dehydrated cladode | López‐Romero et al. (2014) | |

| Polyphenolsd | Avila‐Nava et al. (2014) | |

| Flavonoids | Filannino et al. (2016) | |

| Polyphenolse | Msaddak et al. (2017) | |

| Polyphenolse | Smida et al. (2017) | |

| Polyphenolsf | Kechebar et al. (2017) | |

| Polyphenolsc | Smida et al. (2017) | |

| Polyphenolsb | Petruk et al. (2017) | |

| Polyphenolsc | Andreu et al. (2018) | |

| Polyphenolsg | De Santiago et al. (2018) | |

| Quercetin, isorhamnetin and kaempferole | Salehi et al. (2019) | |

| Fermented cactus cladodes | De Santiago et al. (2019) | |

| Hypoglycemic properties | Flours obtained from different maturity stages | Slimen et al. (2019) |

| Hypercholesterolemia | Isorhamnetin derivatives and piscidic acidf | Antunes‐Ricardo et al. (2017) |

| Neuroprotective activity | Polyphenolsc | Antunes‐Ricardo et al. (2015) |

| Immunoprotective | Polyphenolsc | Nuñez‐López et al. (2013) |

| Thermoprotective properties | Betaninb | Deldicque et al. (2013) |

| Antiproliferative in human colon carcinoma | Polyphenolsf | Serra et al. (2013) |

| Prebiotic potential | Polyphenols, Cladodio | Sánchez Tapia et al. (2017) |

Dissolvent used in the extraction: aNaOH, bwater, cmethanol, dacidified methanol, emethanol:acetone:water, fethanol, gmethanol: acidified water.

Avila‐Nava et al. (2014) assessed the antioxidant capacity of cladodes both in vitro and in vivo, by evaluating the consumption of cladodes for 3 days (300 g/day) in healthy subjects aged 20–30 years, with a body mass index (BMI) <25 kg/m2. The results showed an increase in the antioxidant activity of blood (↑5%) and plasma (↑20%). The polyphenols quercetin, isorhamnetin, and kaempferol were identified by high‐performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). The authors concluded that consuming cladodes can reduce pathologies associated with reactive oxygen species.

Additionally, Petruk et al. 2017 found that eucomic and piscidic acids obtained from cladodes polyphenols were responsible for antioxidant activity and produced a protective effect against apoptosis of human keratinocytes induced by UVA. Scholars classified cladodes as a functional food and a prebiotic since they modify the gut microbiota, reduce metabolic endotoxemia, and other obesity and metabolic syndrome biochemical abnormalities (Angulo‐Bejarano et al., 2014; Mercado‐Mercado et al., 2019; Sanchez‐Tapia et al., 2017). Cladodes have antimicrobial, anticancer, and antidiabetes activity and protective effects on hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, rheumatic pain, antiulcerogenic activity, gastric mucosa diseases, and asthma (Tahir et al. 2019). These beneficial health outcomes are attributed to some components of cladodes: polyphenols (phenolic acids, flavonoids, and anthocyanins), β‐carotene, oligosaccharides, polysaccharides, sterols, lignans, saponins, and some vitamins such as E and C (du Toit et al. 2018).

4. POLYPHENOLS: EXTRACTION AND IDENTIFICATION METHODS

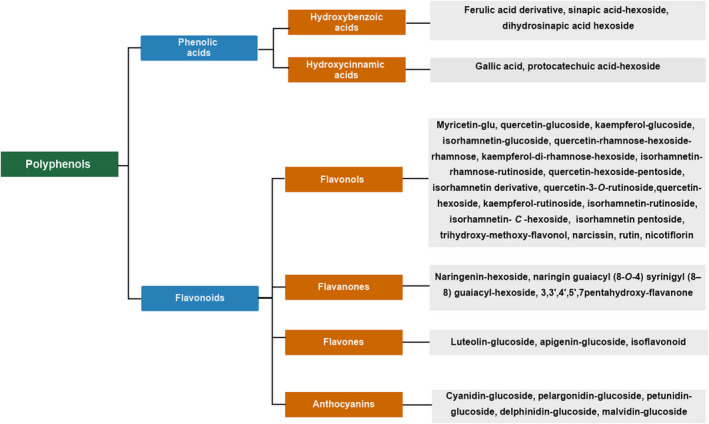

Polyphenols constitute one of the largest groups of secondary plant metabolites (Galanakis et al., 2018; Mirali et al., 2017). They contain one or more hydroxyl groups linked to a benzene ring and have an essential function in the defense against plant pathogens and abiotic stressors (López‐Romero et al., 2014). Figure 3 shows the main polyphenols identified over time in cladodes by different analytical techniques (Antunes‐Ricardo et al., 2014, 2015, 2017; Astello‐García et al., 2015; De Santiago et al., 2018; Msaddak et al., 2017; Rocchetti et al., 2018). Young cladodes have a higher content of polyphenols than mature ones (Figueroa‐Pérez et al., 2018).

FIGURE 3.

Polyphenols in cladodes

4.1. Extraction techniques for the analysis and characterization of polyphenols

Due to the high fiber content of cladodes (Table 1), other minor compounds (of equal biological importance), such as polyphenols, have not been studied deeply. Therefore, we reviewed the methods to extract and characterize polyphenols. Types of extraction methods include liquid‐solid extraction (a procedure that consists of grinding, defatting, solvent extraction, centrifugation, filtration, evaporation, and drying) (Yang et al., 2018) methanol/water/acid, methanol/acetone/water, and methanol/formic acid‐based techniques and are optimized by varying methanol concentrations between 50% and 80% (Table 3). For instance, Antunes‐Ricardo et al. (2014, 2015, 2017) extracted polyphenols with 4 N NaOH (1:10, m/v) at 40℃. Another study carried out by column chromatography, showed that a combination of 45℃ and airflow allowed optimal preservation of phenols and flavonoids (Medina‐Torres et al., 2011). The cladodes extracted by ethanol exhibited good solubility in polar solvents because the polar compounds act as scavengers against reactive oxygen species (Bonilla Rivera et al., 2017). Lastly, the Soxhlet and maceration method conducted by Ammar et al. (2015) in which variability in the extracts yields was attributed to the different polarities of the solvents used; in particular, the methanol and water extract produced the highest extraction yields.

TABLE 3.

Analytical methods for the determination of polyphenols in cladodes

| Opuntia species | Extraction method | Analysis | Compounds identified | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opuntia ficus‐indica (L.) Mill. | Alkaline hydrolysis: 4 N NaOH (1:10, m/v) at 40℃ for 30 min | Detection method: LC/MS‐TOF. Stationary phase: Zorbax SB‐C18, 3.0 × 100 mm, 3.5 µm. Mobile phase: A: water—formic acid, B: methanol. Mode: [M]+; 100–1500 m/z | Quercetin glucosyl‐rhamnosyl‐pentoside, isorhamnetin dihexosyl‐ rhamnoside, kaempferol rhamnosyl‐rhamnosyl‐glucoside, isorhamnetin‐glucosyl‐rhamnosyl‐rhamnoside, isorhamnetin‐glucosyl‐rhamnosyl‐pentoside, isorhamentin hexosyl‐methyl pentosyl‐pentoside, isorhamentin glucosyl‐pentoside, kaempferol‐glucosyl‐rhamnoside, isorhamentin glucosyl‐rhamnoside | Antunes‐Ricardo et al. (2014) |

| Opuntia ficus‐indica (L.) Mill. | Solvent extraction: 0.1 g of sample in 2 ml of methanol:acetone:water (5:4:1), 2.5 hr at 4℃ | Detection method: LC–MS/MS. Stationary phase: Hydro‐RP18, (150 mm × 4.6 mm × 3 mm). Mobile phase: A: acetonitrile/methanol‐formic acid, B: formic acid. Chromatograms recorded: λ = 200–600 nm | Eucomic acid, chlorogenic acid, chlorogenic acid derivative, quercetin 3‐O‐rhamnosyl‐ (1→2)‐[rhamnosyl‐(1→6)]‐glucoside, quercetin 3‐O‐xylosyl‐ rhamnosyl‐glucoside, quercetin 3‐O‐dirhamnoside, kaempferol 3‐O‐(rhamnosyl‐galactoside)−7‐O‐rhamnoside, kaempferol 3‐O‐(rhamnosyl‐glucoside)−7‐O‐rhamnoside, kaempferol 3‐O‐robinobioside‐ 7‐O‐arabinofuranoside, isorhamnetin 3‐O‐rhamnoside‐ 7‐O‐(rhamnosyl‐hexoside), quercetin 3‐O‐rutinoside, quercetin 3‐O‐glucoside, isorhamnetin 3‐O‐rutinoside, kaempferol 3‐O‐rutinoside, quercetin 3‐O‐ arabinofuranoside, kaempferol 3‐O‐glucoside, kaempferol 7‐O‐neohesperidoside, isorhamnetin 3‐O‐galactoside | Astello‐García et al. (2015) |

| Opuntia ficus‐indica (L.) Mill. | Alkaline hydrolysis: 4 N NaOH (1:10, m/v) at 40℃ for 30 min | Detection method: HPLC‐PDA. Stationary phase: Zorbax SB‐C18 (9.4 × 250 mm, 5 µm). Mobile phase: A: water—formic acid, B: methanol. Mode: [M]+;100–1500 m/z | Isorhamnetin‐glucosyl‐pentoside, isorhamnetin‐glucosyl‐rhamnoside, isorhamnetin‐glucosyl‐rhamnosyl‐rhamnoside, isorhamnetin‐glucosyl‐rhamnosyl‐pentoside | Antunes‐Ricardo et al. (2015) |

| Opuntia ficus‐indica f. inermis | Maceration: 25 g of sample, ethanol 100%, 24 hr | Detection method: LC‐HRESIMS. Stationary phase: RP Pursuit XRs ULTRA 2.8, C18, 100 mm ×2 mm. Mobile phase: A: formic acid‐water, B: formic acid‐metanol. Mode: [M]+ 100–2,000 m/z | Quercetin, quercetin 3‐O‐glucoside, kaempferol, kaempferol 3‐O‐glucoside, kaempferol 3‐O‐rutinoside, isorhamnetin, isorhamnetin 3‐O‐glucoside, isorhamnetin 3‐O‐neohesperidoside, 3,3ʹ,4ʹ,5,7‐pentahydroxy‐flavanone, p‐coumaric acid, zataroside‐A, indicaxanthin, ß‐sitosterol | Msaddak et al. (2017) |

| Opuntia ficus‐indica (L.) Mill. | Solvent extraction: 4 g of sample, methanol 50%, 2 hr | Detection method: HPLC‐DAD. Stationary phase: Kinetex C18, 5 µm RP 250 × 4.60 mm. Mobile phase: A: water—formic acid, B: acetonitrile. Chromatograms recorded: Phenolic acids: λ = 256–325 nm, flavonoids: λ = 360 nm | Quercetin, kaempferol, isorhamnetin, ferulic acid, 4‐hydroxybenzoic acid | De Santiago et al. (2018) |

| Opuntia ficus‐indica | Agitation: 4 g of sample, 0.1% formic acid in 80:20 (v/v) methanol/water, 25,000 rpm for 3 min | Detection method: UHPLC‐ESI‐QTOF‐MS; Stationary phase: Agilent Zorbax eclipse plus C18, 50 × 2.1 mm, 1.8 µm. Mobile phase: A: water, B: methanol‐formic acid‐ammonium formate. Mode:[M]+ 50–1000 m/z | Luteolin‐glu, apigenin‐glu, isoflavonoid, myricetin‐glu, quercetin‐glu, kaempferol‐Glu, isorhamnetin‐Glu, furofurans, dibenzylbutyrolactone, alkylphenols, hydroxybenzaldehydes hydroxycoumarins tyrosols, hydroxybenzoics, hydroxyphenylpropanoics, hydroxycinnamics | Rocchetti et al. (2018) |

| Opuntia ficus‐indica (L.) Mill. | Solvent extraction: 200 mg of sample, methanol acidified with formic acid, Sonicated for 25 min | Detection method: UHPLC‐ESI‐MSn. Stationary phase: XSelect HSS T3, (50 × 2.1 mm × 2.5 µm). Mobile phase: A: acetonitrile—formic acid, B: acidified acetonitrile. Mode: [M]−: noncolored phenolics, [M]+: Betalains | Protocatechuic acid hexoside, myricetin‐hexoside, ferulic acid derivative, ferulic acid hexoside, sinapic acid hexoside, quercetin‐rhamnose‐hexoside‐rhamnose, rutin‐pentoside, syrinigyl(t8‐O−4)guaiacyl, kaempferol‐di‐rhamnose‐hexoside, isorhamnetin‐ rhamnose‐rutinoside, quercetin‐hexoside‐pentoside, isorhamnetin derivative, dihydrosinapic acid hexoside, quercetin 3‐O‐rutinoside (rutin), secoisolariciresinol‐hexoside, isorhamnetin derivative, quercetin‐hexoside, kaempferol‐rutinoside, syringaresinol, naringenin‐hexoside, isorhamnetin rutinoside, isorhamnetin‐C‐hexoside, naringin | Mena et al. (2018) |

| Opuntia ficus‐indica (L.) Mill. | Maceration: 500 mg in 25 ml aqueous methanol (80%) overnight at 4℃ | Detection method: LC/MS‐TOF. Stationary phase: Agilent Extended C18 (1.8 μm, 2.1 × 50 mm). Mobile phase: A: water +0.1% formic acid, B: acetonitrile. Mode: [M]−: 50–1,700 m/z | Piscidic acid, eucomic acid, isorhamnetin rhamnosyl‐rutinoside, isorhamnetin‐glucosyl‐rhamnosyl‐pentoside, rutin, narcissin (isorhamnetin rutinoside), isorhamnetin glucoside | Blando et al. (2019) |

| Opuntia ficus‐indica | Solvent extraction: 100% methanol (3× 2L) | Detection method: HPLC‐PDA‐Ms/Ms; Stationary phase: HS F5 column (15 cm 4.6 mm ID, 5 mm; Mobile phase: A:Water +0.1% formic, B: Acetonitrile +0.1% formic; Mode:[M]+ | Quinic acid, malic acid, piscidic acid, diferuloyl‐syringsic acid, eucomic acid, dicaffeoylferulic acid, p‐coumaric acid 3‐O‐glucoside, 7‐glucosyl‐oxy−5‐methyl flavone glucoside sinapic acid 3‐O‐glucoside, sinapic acid 3‐O‐galactoside, quercetin pentosyl‐rutinoside, kaempferol rhamnosyl‐rutinoside isorhamnetin‐glucosyl‐rutinoside, rhamnetin rhamnosyl‐rutinoside, isorhamnetin rhamnosyl‐rutinoside, isorhamnetin pentosyl‐rutinoside, rutin, kaempferol pentosyl‐rutinoside, isorhamnetin pentosyl‐rutinoside, isorhamnetin pentosyl‐hexoside, isorhamnetin rutinoside, rhamnetin 3‐O‐glucoside, isorhamnetin 3‐O‐glucoside, isorhamnetin coumaroyl‐rutinoside, rhamnetin, isorhamnetin, diosmetin, tricin, hydroxyl octadecadienoic acid, eicosanoic acid, eicosanoic acid isomer heneicosanoic acid eicosanoic acid isomer behenic acid | El‐Hawary et al. (2020) |

HPLC‐PDA: high‐pressure liquid chromatograph equipped with a photodiode array detector; UHPLC‐ESI‐QTOF‐MS: ultrahigh‐performance liquid chromatography coupled with electrospray ionization‐quadrupole time‐of‐flight mass spectrometry; HPLC‐PDA‐Ms/Ms: High‐performance liquid chromatography‐photodiode array‐electrospray ionization mass spectrometry; LC/ MS‐TOF: liquid chromatography coupled to a time‐of‐flight mass spectrometer; UHPLC‐ESI‐MSn: ultrahigh‐performance liquid chromatography with electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry; LC–MS/MS: high‐performance liquid chromatographic and mass spectrometric; HPLC‐DAD: high‐performance liquid chromatography‐diode array detector system; LC‐HRESIMS: liquid chromatography‐high resolution electro‐spray ionization mass spectrometry.

Obtaining polyphenol‐rich extracts requires sample purification by column chromatography (Nemitz et al., 2015). Chromatography is a physical separation method based on differential migration of the sample components carried by the mobile phase through a stationary phase arranged in a column (Granato et al., 2016). Four types of chromatography can be applied to determine the polyphenolic profile of crude extracts from biological materials: high‐performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), thin‐layer chromatography (TLC), high‐performance thin‐layer chromatography (HPTLC), and capillary electrophoresis (CE) (Agatonovic‐Kustrin et al., 2020; Gadioli et al., 2018).

The highest extraction yields were obtained when using C18 reversed‐phase HPLC columns (with inner diameter 2–250 mm; particle size 1.8–2 5 μm) and a mobile phase composed of methanol or acetonitrile under isocratic elution or gradient elution (i.e., water and 0.1%–10% acetic or formic acid) conditions (Table 3). However, a factor to consider is the production of raw extracts, in which the management of parameters such as extraction time, temperature, and solvent composition influence the concentration and types of compounds obtained.

4.2. Identification of polyphenols

Several authors have identified polyphenols in cladodes through HPLC and UHPLC because they maximize polyphenol identification accuracy (Tan & Fanaras, 2018). Hence, these techniques lead the separation methods for polyphenols analysis (Table 3).

A study conducted by Petruk et al. (2017) with extracts from Opuntia ficus‐indica var. saboten found three phenolic acid derivatives: piscidic, eucomic, and 2‐hydroxy‐4‐(4‐hydroxyphenyl)‐butanoic acid. Astello‐García et al. (2015) identified polyphenols via LC‐MS according to retention time, UV spectra, and mass (m/z). Through the aglycone fragment, they examined the structure of each flavonoid by characterizing quercetin ([M]+ m/z 301), isorhamnetin ([M]+ m/z 315), kaempferol ([M]+ m/z 285), and luteolin ([M]+ m/z 285).

Similarly, Antunes‐Ricardo et al. (2015) found isorhamnetin glycosides by HPLC‐PDA. Rocchetti et al. (2018) detected 89 flavonoids—mostly the glycosidic forms of kaempferol, isorhamnetin, and quercetin—and 54 phenolic acids in cladodes. This was the first evaluation that includes the phenolic profile in cladodes using UHPLC‐ESI/QTOF‐MS. Msaddak et al. (2017) studied an ethanolic extract of cladodes utilizing LC‐HR‐ESI‐MS; they found 9 flavonoids and 2 phenolic acids. Furthermore, Mena et al. (2018) identified flavanones and lignans by UHPLC‐ESI‐MSn and observed a higher polyphenol content in young cladodes compared with matures ones, which could be attributed to physiological modifications.

Spectrometry‐based techniques are a powerful and fast tool to accurately differentiate compounds in food matrices. However, it is unreliable when quantifying polyphenols due to the lack of availability of reference standards. Among the analytical methods compared in this review, UHPLC‐ESI/QTOF‐MS exhibited an outstanding performance to identify the main polyphenolic classes and subclasses in cladode extracts. Simultaneously, it detected multiple compounds based on the mass‐to‐charge ratio (m/z) of a molecular ion ([M − H]‐) and the characteristic production for each polyphenol.

5. CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

The present study reviewed the structure function of cladodes, which may provide an nutritional and functional value given the properties of their major chemical components. Several studies have shown that polyphenols in cladodes are associated with beneficial effects on human health. Polyphenols can be separated and identified by conducting advanced analytical techniques, which have different advantages associated with the solute‐solvent ratio. Here, we described diverse processes in current research to detect polyphenols in cladodes that could be implemented in future technological developments. The forthcoming research should focus on obtaining additional information to standardize the analytical methods designed to categorize and quantify the polyphenols in cladodes; and conducting more experimental studies, such as in vivo models, on polyphenol cladode extracts to determine the characterization of nopal biological activity.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Madeleine Perucini‐Avendaño: Conceptualization (lead); Investigation (lead); Writing‐original draft (lead). Mayra Nicolás‐García: Conceptualization (supporting); Investigation (supporting). Cristian Jimenez: Conceptualization (equal); Investigation (equal); Supervision (lead); Writing‐review & editing (supporting). Maria de Jesús Perea‐Flores: Formal analysis (supporting); Supervision (supporting). Mayra Beatriz Gómez‐Patiño: Visualization (supporting). Daniel Arrieta‐Baez: Visualization (supporting). Gloria Davila‐Ortiz: Project administration (lead); Supervision (supporting); Writing‐review & editing (lead).

ETHICS APPROVAL

Studies involving animal or human subjects were not required for this review.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors are grateful to the Instituto Politécnico Nacional (IPN‐Mexico) for the support provided through the SIP Projects (SIP projects: 20181560, 20196640) and CONACyT projects (241756).

Perucini‐Avendaño M, Nicolás‐García M, Jiménez‐Martínez C, et al. Cladodes: Chemical and structural properties, biological activity, and polyphenols profile. Food Sci Nutr. 2021;9:4007–4017. 10.1002/fsn3.2388

REFERENCES

- Agatonovic‐Kustrin, S. , Doyle, E. , Gegechkori, V. , & Morton, D. W. (2020). High‐performance thin‐layer chromatography linked with (bio) assays and FTIR‐ATR spectroscopy as a method for discovery and quantification of bioactive components in native Australian plants. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis, 184, 113208. 10.1016/j.jpba.2020.113208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammar, I. , Ennouri, M. , & Attia, H. (2015). Phenolic content and antioxidant activity of cactus (Opuntia ficus‐indica L.) flowers are modified according to the extraction method. Industrial Crops and Products, 64, 97–104. 10.1016/j.indcrop.2014.11.030 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Andreu, L. , Nuncio‐Jáuregui, N. , Carbonell‐Barrachina, Á. A. , Legua, P. , & Hernández, F. (2018). Antioxidant properties and chemical characterization of Spanish Opuntia ficus‐indica Mill. cladodes and fruits. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 98(4), 1566–1573. 10.1002/jsfa.8628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angulo‐Bejarano, P. I. , Martínez‐Cruz, O. , & Paredes‐López, O. (2014). Phytochemical content, nutraceutical potential and biotechnological applications of an ancient Mexican plant: nopal (Opuntia ficus‐indica). Current Nutrition & Food Science, 10(3), 196–217. 10.2174/157340131003140828121015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Antunes‐Ricardo, M. , Gutiérrez‐Uribe, J. A. , & Guajardo‐Flores, D. (2017). Extraction of isorhamnetin conjugates from Opuntia ficus‐indica (L.) Mill using supercritical fluids. The Journal of Supercritical Fluids, 119, 58–63. 10.1016/j.supflu.2016.09.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Antunes‐Ricardo, M. , Gutiérrez‐Uribe, J. A. , López‐Pacheco, F. , Alvarez, M. M. , & Serna‐Saldívar, S. O. (2015). In vivo anti‐inflammatory effects of isorhamnetin glycosides isolated from Opuntia ficus‐indica (L.) Mill cladodes. Industrial Crops and Products, 76, 803–808. 10.1016/j.indcrop.2015.05.089 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Antunes‐Ricardo, M. , Moreno‐García, B. E. , Gutiérrez‐Uribe, J. A. , Aráiz‐Hernández, D. , Alvarez, M. M. , & Serna‐Saldivar, S. O. (2014). Induction of apoptosis in colon cancer cells treated with isorhamnetin glycosides from Opuntia ficus‐indica pads. Plant Foods for Human Nutrition, 69(4), 331–336. 10.1007/s11130-014-0438-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aparicio‐Saguilán, A. , Valera‐Zaragoza, M. , Perucini‐Avendaño, M. , Páramo‐Calderón, D. E. , Aguirre‐Cruz, A. , Ramírez‐Hernández, A. , & Bello‐Pérez, L. A. (2015). Lintnerization of banana starch isolated from underutilized variety: Morphological, thermal, functional properties, and digestibility. CyTA‐Journal of Food, 13(1), 3–9. 10.1080/19476337.2014.902864 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aruwa, C. E. , Amoo, S. O. , & Kudanga, T. (2018). Opuntia (Cactaceae) plant compounds, biological activities, and prospects–A comprehensive review. Food Research International, 112, 328–344. 10.1016/j.foodres.2018.06.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astello‐García, M. G. , Cervantes, I. , Nair, V. , Santos‐Díaz, M. D. S. , Reyes‐Agüero, A. , Guéraud, F. , Negre‐Salvayre, A. , Rossignol, M. , Cisneros‐Zevallos, L. , & Barba de la Rosa, A. P. (2015). Chemical composition and phenolic compounds profile of cladodes from Opuntia spp. cultivars with different domestication gradient. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis, 43, 119–130. 10.1016/j.jfca.2015.04.016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Avila‐Nava, A. , Calderón‐Oliver, M. , Medina‐Campos, O. N. , Zou, T. , Gu, L. , Torres, N. , Tovar, A. R. , & Pedraza‐Chaverri, J. (2014). Extract of cactus (Opuntia ficus indica) cladodes scavenges reactive oxygen species in vitro and enhances plasma antioxidant capacity in humans. Journal of Functional Foods, 10, 13–24. 10.1016/j.jff.2014.05.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Avila‐Nava, A. , Noriega, L. G. , Tovar, A. R. , Granados, O. , Perez‐Cruz, C. , Pedraza‐Chaverri, J. , & Torres, N. (2017). Food combination based on a pre‐Hispanic Mexican diet decreases metabolic and cognitive abnormalities and gut microbiota dysbiosis caused by a sucrose‐enriched high‐fat diet in rats. Molecular Nutrition & Food Research, 61(1), 1501023. 10.1002/mnfr.201501023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayar, N. , Kriaa, M. , & Kammoun, R. (2016). Extraction and characterization of three polysaccharides extracted from Opuntia ficus indica cladodes. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 92, 441–450. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.07.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belhadj Slimen, I. , Chabaane, H. , Chniter, M. , Mabrouk, M. , Ghram, A. , Miled, K. , Behi, I. , Abderrabba, M. , & Najar, T. (2019). Thermoprotective properties of Opuntia ficus‐indica f. inermis cladodes and mesocarps on sheep lymphocytes. Journal of Thermal Biology, 81, 73–81. 10.1016/j.jtherbio.2019.02.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blando, F. , Russo, R. , Negro, C. , De Bellis, L. , & Frassinetti, S. (2019). Antimicrobial and antibiofilm activity against Staphylococcus aureus of Opuntia ficus‐indica (L.) Mill. cladode polyphenolic extracts. Antioxidants, 8(5), 117. 10.3390/antiox8050117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla Rivera, P. E. , Fernandez Rebaza, G. A. , Bustamante Peñaloza, L. E. , Casas Martel, L. E. , Cirineo Rodríguez, M. X. , Hinostroza Lorenzo, M. L. , Villar Melendez, H. C. , & Yupanqui Gallegos, B. M. (2017). Determinación estructural de flavonoides en el extracto etanólico de cladodios de Opuntia ficus‐indica (L.) Mill. “Tuna Verde”. Revista Peruana De Medicina Integrativa, 2(4), 835–840. 10.26722/rpmi.2017.24.71 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo, C. H. , Gómez‐Cuaspud, J. A. , & Suarez, C. M. (2017). Compositional, thermal and microstructural characterization of the Nopal (Opuntia ficus indica), for addition in commercial cement mixtures. In Journal of Physics: Conference Series (Vol. 935, No. 1, p. 012045). IOP Publishing. 10.1088/1742-6596/935/1/012045 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ciriminna, R. , Chavarría‐Hernández, N. , Rodríguez‐Hernández, A. I. , & Pagliaro, M. (2019). Toward unfolding the bioeconomy of nopal (Opuntia spp.). Biofuels, Bioproducts and Biorefining, 13(6), 1417–1427. 10.1002/bbb.2018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Contreras‐Padilla, M. , Rodríguez‐García, M. E. , Gutiérrez‐Cortez, E. , del Carmen Valderrama‐Bravo, M. , Rojas‐Molina, J. I. , & Rivera‐Muñoz, E. M. (2016). Physicochemical and rheological characterization of Opuntia ficus mucilage at three different maturity stages of cladode. European Polymer Journal, 78, 226–234. 10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2016.03.024 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cornejo‐Villegas, M. A. , Acosta‐Osorio, A. A. , Rojas‐Molina, I. , Gutiérrez‐Cortéz, E. , Quiroga, M. A. , Gaytán, M. , Herrera, G. , & Rodríguez‐García, M. E. (2010). Study of the physicochemical and pasting properties of instant corn flour added with calcium and fibers from nopal powder. Journal of Food Engineering, 96(3), 401–409. 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2009.08.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Albuquerque, J. G. , de Souza Aquino, J. , de Albuquerque, J. G. , de Farias, T. G. S. , Escalona‐Buendía, H. B. , Bosquez‐Molina, E. , & Azoubel, P. M. (2019). Consumer perception and use of nopal (Opuntia ficus‐indica): A cross‐cultural study between Mexico and Brazil. Food Research International, 124, 101–108. 10.1016/j.foodres.2018.08.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Santiago, E. , Domínguez‐Fernández, M. , Cid, C. , & De Peña, M. P. (2018). Impact of cooking process on nutritional composition and antioxidants of cactus cladodes (Opuntia ficus‐indica). Food Chemistry, 240, 1055–1062. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.08.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Santiago, E. , Gill, C. I. , Carafa, I. , Tuohy, K. M. , De Peña, M. P. , & Cid, C. (2019). Digestion and colonic fermentation of raw and cooked Opuntia ficus‐indica cladodes impacts bioaccessibility and bioactivity. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 67(9), 2490–2499. 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b06480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deldicque, L. , Van Proeyen, K. , Ramaekers, M. , Pischel, I. , Sievers, H. , & Hespel, P. (2013). Additive insulinogenic action of Opuntia ficus‐indica cladode and fruit skin extract and leucine after exercise in healthy males. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 10(1), 1–6. 10.1186/1550-2783-10-45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Lorenzo, F. , Silipo, A. , Molinaro, A. , Parrilli, M. , Schiraldi, C. , D’Agostino, A. , Izzo, E. , Rizza, L. , Bonina, A. , Bonina, F. , & Lanzetta, R. (2017). The polysaccharide and low molecular weight components of Opuntia ficus indica cladodes: Structure and skin repairing properties. Carbohydrate Polymers, 157, 128–136. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2016.09.073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Toit, A. , De Wit, M. , Osthoff, G. , & Hugo, A. (2018). Antioxidant properties of fresh and processed cactus pear cladodes from selected Opuntia ficus‐indica and O. robusta cultivars. South African journal of botany, 118, 44–51. [Google Scholar]

- El‐Hawary, S. S. , Sobeh, M. , Badr, W. K. , Abdelfattah, M. A. O. , Ali, Z. Y. , El‐Tantawy, M. E. , Rabeh, M. A. , & Wink, M. (2020). HPLC‐PDA‐MS/MS profiling of secondary metabolites from Opuntia ficus‐indica cladode, peel and fruit pulp extracts and their antioxidant, neuroprotective effect in rats with aluminum chloride induced neurotoxicity. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences, 27(10), 2829–2838. 10.1016/j.sjbs.2020.07.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El‐Mostafa, K. , El Kharrassi, Y. , Badreddine, A. , Andreoletti, P. , Vamecq, J. , El Kebbaj, M. S. , Latruffe, N. , Lizard, G. , Nasser, B. , & Cherkaoui‐Malki, M. (2014). Nopal cactus (Opuntia ficus‐indica) as a source of bioactive compounds for nutrition, health and disease. Molecules, 19, 14879–14901. 10.3390/molecules190914879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FAOSTAT . (2016). Food & Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Statistics Division. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Statistics Division. http://www.fao.org/home/en/

- Feugang, J. M. , Konarski, P. , Zou, D. , Stintzing, F. C. , & Zou, C. (2006). Nutritional and medicinal use of Cactus pear (Opuntia spp.) cladodes and fruits. Frontiers in Bioscience, 11(1), 2574–2589. 10.2741/1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa‐Pérez, M. G. , Pérez‐Ramírez, I. F. , Paredes‐López, O. , Mondragón‐Jacobo, C. , & Reynoso‐Camacho, R. (2018). Phytochemical composition and in vitro analysis of nopal (O. ficus‐indica) cladodes at different stages of maturity. International Journal of Food Properties, 21(1), 1728–1742. 10.1080/10942912.2016.1206126 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Filannino, P. , Cavoski, I. , Thlien, N. , Vincentini, O. , De Angelis, M. , Silano, M. , Gobbetti, M. , & Di Cagno, R. (2016). Lactic acid fermentation of cactus cladodes (Opuntia ficus‐indica L.) generates flavonoid derivatives with antioxidant and anti‐inflammatory properties. PLoS One, 11(3), e0152575. 10.1371/journal.pone.0152575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadioli, I. L. , da Cunha, M. D. S. B. , de Carvalho, M. V. O. , Costa, A. M. , & Pineli, L. D. L. D. O. (2018). A systematic review on phenolic compounds in Passiflora plants: Exploring biodiversity for food, nutrition, and popular medicine. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 58(5), 785–807. 10.1080/10408398.2016.1224805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galanakis, C. M. , Tsatalas, P. , & Galanakis, I. M. (2018). Phenols from olive mill wastewater and other natural antioxidants as UV filters in sunscreens. Environmental Technology & Innovation, 9, 160–168. 10.1016/j.eti.2017.12.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, L. J. (2012). The hierarchical structure and mechanics of plant materials. Journal of the Royal Society Interface, 9(76), 2749–2766. 10.1098/rsif.2012.0341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginestra, G. , Parker, M. L. , Bennett, R. N. , Robertson, J. , Mandalari, G. , Narbad, A. , Lo Curto, R. B. , Bisignano, G. , Faulds, C. B. , & Waldron, K. W. (2009). Anatomical, chemical, and biochemical characterization of cladodes from prickly pear [Opuntia ficus‐indica (L.) Mill.]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 57(21), 10323–10330. 10.1021/jf9022096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granato, D. , Santos, J. S. , Maciel, L. G. , & Nunes, D. S. (2016). Chemical perspective and criticism on selected analytical methods used to estimate the total content of phenolic compounds in food matrices. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry, 80, 266–279. 10.1016/j.trac.2016.03.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guevara‐Figueroa, T. , Jiménez‐Islas, H. , Reyes‐Escogido, M. L. , Mortensen, A. G. , Laursen, B. B. , Lin, L.‐W. , De León‐Rodríguez, A. , Fomsgaard, I. S. , & Barba de la Rosa, A. P. (2010). Proximate composition, phenolic acids, and flavonoids characterization of commercial and wild nopal (Opuntia spp.). Journal of Food Composition and Analysis, 23(6), 525–532. 10.1016/j.jfca.2009.12.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez‐Becerra, E. , Mendoza‐Avila, M. , Jiménez‐Mendoza, D. , Gutierrez‐Cortez, E. , Rodríguez‐García, M. E. , & Rojas‐Molina, I. (2020). Effect of Nopal (Opuntia ficus indica) consumption at different maturity stages as an only calcium source on bone mineral metabolism in growing rats. Biological Trace Element Research, 194(1), 168–176. 10.1007/s12011-019-01752-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernández‐Urbiola, M. I. , Contreras‐Padilla, M. , Pérez‐Torrero, E. , Hernández‐Quevedo, G. , Rojas‐Molina, J. I. , Cortes, M. E. , & Rodríguez‐García, M. E. (2010). Study of nutritional composition of nopal (Opuntia ficus indica cv. Redonda) at different maturity stages. The Open Nutrition Journal, 4(1), 11–16. 10.2174/1874288201004010011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Horibe, T. (2018). Advantages of hydroponics in edible cacti production. Horticulture International Journal, 2(4), 154–156. 10.15406/hij.2018.02.00044 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kechebar, M. S. A. , Karoune, S. , Laroussi, K. , & Djellouli, A. (2017). Phenolic composition and antioxidant activities of Opuntia ficus Indica L. cladodes related to extraction method. International Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemical Research, 9(6). 10.25258/phyto.v9i6.8171. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khouloud, A. , Abedelmalek, S. , Chtourou, H. , & Souissi, N. (2018). The effect of Opuntia ficus‐indica juice supplementation on oxidative stress, cardiovascular parameters, and biochemical markers following yo‐yo Intermittent recovery test. Food Science & Nutrition, 6(2), 259–268. 10.1002/fsn3.529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J. W. , Kim, T. B. , Yang, H. , & Sung, S. H. (2016). Phenolic compounds isolated from Opuntia ficus‐indica fruits. Natural Product Sciences, 22(2), 117–121. https://10.20307/nps.2016.22.2.117 [Google Scholar]

- López‐Palacios, C. , Peña‐Valdivia, C. B. , Rodríguez‐Hernández, A. I. , & Reyes‐Agüero, J. A. (2016). Rheological flow behavior of structural polysaccharides from edible tender cladodes of wild, semidomesticated and cultivated ‘nopal’(Opuntia) of mexican highlands. Plant Foods for Human Nutrition, 71(4), 388–395. 10.1007/s11130-016-0573-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López‐Romero, P. , Pichardo‐Ontiveros, E. , Avila‐Nava, A. , Vázquez‐Manjarrez, N. , Tovar, A. R. , Pedraza‐Chaverri, J. , & Torres, N. (2014). The effect of nopal (Opuntia ficus indica) on postprandial blood glucose, incretins, and antioxidant activity in Mexican patients with type 2 diabetes after consumption of two different composition breakfasts. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 114(11), 1811–1818. 10.1016/j.jand.2014.06.352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majdoub, H. , Roudesli, S. , & Deratani, A. (2001). Polysaccharides from prickly pear peel and nopals of Opuntia ficus‐indica: Extraction, characterization, and polyelectrolyte behaviour. Polymer International, 50(5), 552–560. 10.1002/pi.665 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marin‐Bustamante, M. Q. , Chanona‐Pérez, J. J. , Gυemes‐Vera, N. , Arzate‐Vázquez, I. , Perea‐Flores, M. J. , Mendoza‐Pérez, J. A. , Calderón‐Domínguez, G. , & Casarez‐Santiago, R. G. (2018). Evaluation of physical, chemical, microstructural and micromechanical properties of nopal spines (Opuntia ficus‐indica). Industrial Crops and Products, 123, 707–718. 10.1016/j.indcrop.2018.07.030 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Medina‐Torres, L. , García‐Cruz, E. E. , Calderas, F. , González Laredo, R. F. , Sánchez‐Olivares, G. , Gallegos‐Infante, J. A. , Rocha‐Guzmán, N. E. , & Rodríguez‐Ramírez, J. (2013). Microencapsulation by spray drying of gallic acid with nopal mucilage (Opuntia ficus indica). LWT‐Food Science and Technology, 50(2), 642–650. 10.1016/j.lwt.2012.07.038 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Medina‐Torres, L. , Vernon‐Carter, E. J. , Gallegos‐Infante, J. A. , Rocha‐Guzman, N. E. , Herrera‐Valencia, E. E. , Calderas, F. , & Jiménez‐Alvarado, R. (2011). Study of the antioxidant properties of extracts obtained from nopal cactus (Opuntia ficus‐indica) cladodes after convective drying. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 91(6), 1001–1005. 10.1002/jsfa.4271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mena, P. , Tassotti, M. , Andreu, L. , Nuncio‐Jáuregui, N. , Legua, P. , Del Rio, D. , & Hernández, F. (2018). Phytochemical characterization of different prickly pear (Opuntia ficus‐indica (L.) Mill.) cultivars and botanical parts: UHPLC‐ESI‐MSn metabolomics profiles and their chemometric analysis. Food Research International, 108, 301–308. 10.1016/j.foodres.2018.03.062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercado‐Mercado, G. , Blancas‐Benítez, F. J. , Zamora‐Gasga, V. M. , & Sáyago‐Ayerdi, S. G. (2019). Mexican Traditional Plant‐Foods: Polyphenols Bioavailability, Gut Microbiota Metabolism and Impact Human Health. Current Pharmaceutical Design, 25(32), 3434–3456. 10.2174/1381612825666191011093753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirali, M. , Purves, R. W. , & Vandenberg, A. (2017). Profiling the phenolic compounds of the four major seed coat types and their relation to color genes in lentil. Journal of Natural Products, 80(5), 1310–1317. 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.6b00872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mounir, B. , Younes, E. G. , Asmaa, M. , Abdeljalil, Z. , & Abdellah, A. (2020). Physico‐chemical changes in cladodes of Opuntia ficus‐indica as a function of the growth stage and harvesting areas. Journal of Plant Physiology, 251, 153196. 10.1016/j.jplph.2020.153196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Msaddak, L. , Abdelhedi, O. , Kridene, A. , Rateb, M. , Belbahri, L. , Ammar, E. , Nasri, M. , & Zouari, N. (2017). Opuntia ficus‐indica cladodes as a functional ingredient: Bioactive compounds profile and their effect on antioxidant quality of bread. Lipids in Health and Disease, 16(1), 32. 10.1186/s12944-016-0397-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemitz, M. C. , Moraes, R. C. , Koester, L. S. , Bassani, V. L. , von Poser, G. L. , & Teixeira, H. F. (2015). Bioactive soy isoflavones: Extraction and purification procedures, potential dermal use and nanotechnology‐based delivery systems. Phytochemistry Reviews, 14(5), 849–869. 10.1007/s11101-014-9382-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nuñez‐López, M. A. , Paredes‐López, O. , & Reynoso‐Camacho, R. (2013). Functional and hypoglycemic properties of nopal cladodes (O. ficus‐indica) at different maturity stages using in vitro and in vivo tests. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 61(46), 10981–10986. 10.1021/jf403834x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petruk, G. , Di Lorenzo, F. , Imbimbo, P. , Silipo, A. , Bonina, A. , Rizza, L. , Piccoli, R. , Monti, D. M. , & Lanzetta, R. (2017). Protective effect of Opuntia ficus‐indica L. cladodes against UVA‐induced oxidative stress in normal human keratinocytes. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters, 27(24), 5485–5489. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2017.10.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinzio, C. , Ayunta, C. , de Mishima, B. L. , & Iturriaga, L. (2018). Stability and rheology properties of oil‐in‐water emulsions prepared with mucilage extracted from Opuntia ficus‐indica (L). Miller . Food Hydrocolloids, 84, 154–165. 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2018.06.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rocchetti, G. , Pellizzoni, M. , Montesano, D. , & Lucini, L. (2018). Italian Opuntia ficus‐indica cladodes as rich source of bioactive compounds with health‐promoting properties. Foods, 7(2), 24. 10.3390/foods7020024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez‐González, S. , Martínez‐Flores, H. E. , Chávez‐Moreno, C. K. , Macías‐Rodríguez, L. I. , Zavala‐Mendoza, E. , Garnica‐Romo, M. G. , & Chacón‐García, L. (2014). Extraction and characterization of mucilage from wild species of O puntia . Journal of Food Process Engineering, 37(3), 285–292. 10.1111/jfpe.12084 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salehi, E. , Emam‐Djomeh, Z. , Askari, G. , & Fathi, M. (2019). Opuntia ficus indica fruit gum: Extraction, characterization, antioxidant activity and functional properties. Carbohydrate Polymers, 206, 565–572. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.11.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salem‐Fnayou, A. B. , Zemni, H. , Nefzaoui, A. , & Ghorbel, A. (2014). Micromorphology of cactus‐pear (Opuntia ficus‐indica (L.) Mill) cladodes based on scanning microscopies. Micron, 56, 68–72. 10.1016/j.micron.2013.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez‐Tapia, M. , Aguilar‐López, M. , Pérez‐Cruz, C. , Pichardo‐Ontiveros, E. , Wang, M. , Donovan, S. M. , Tovar, A. R. , & Torres, N. (2017). Nopal (Opuntia ficus indica) protects from metabolic endotoxemia by modifying gut microbiota in obese rats fed high fat/sucrose diet. Scientific reports, 7(1), 1–16. 10.1038/s41598-017-05096-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos‐Zea, L. , Gutiérrez‐Uribe, J. A. , & Serna‐Saldivar, S. O. (2011). Comparative analyses of total phenols, antioxidant activity, and flavonol glycoside profile of cladode flours from different varieties of Opuntia spp. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 59(13), 7054–7061. 10.1021/jf200944y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scaffaro, R. , Maio, A. , Gulino, E. F. , & Megna, B. (2019). Structure‐property relationship of PLA‐Opuntia Ficus Indica biocomposites. Composites Part B: Engineering, 167, 199–206. 10.1016/j.compositesb.2018.12.025 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scalbert, A. , Manach, C. , Morand, C. , Rémésy, C. , & Jiménez, L. (2005). Dietary polyphenols and the prevention of diseases. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 45(4), 287–306. 10.1080/1040869059096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serra, A. T. , Poejo, J. , Matias, A. A. , Bronze, M. R. , & Duarte, C. M. (2013). Evaluation of Opuntia spp. derived products as antiproliferative agents in human colon cancer cell line (HT29). Food Research International, 54(1), 892–901. 10.1016/j.foodres.2013.08.043 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Small, E. , & Catling, P. M. (2004). Blossoming treasures of biodiversity 11. Cactus pear (Opuntia ficus‐indica)‐ miracle of water conservation. Biodivers, 5(1), 27–31. [Google Scholar]

- Smida, A. , Ncibi, S. , Taleb, J. , Saad, A. B. , Ncib, S. , & Zourgui, L. (2017). Immunoprotective activity and antioxidant properties of cactus (Opuntia ficus indica) extract against chlorpyrifos toxicity in rats. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy, 88, 844–851. 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.01.105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tahir, H. E. , Xiaobo, Z. , Komla, M. G. , & Mariod, A. A. (2019). Nopal cactus (Opuntia ficus‐indica (L.) Mill) as a source of bioactive compounds. In Wild Fruits: Composition, Nutritional Value and Products, (333–358). Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, A. , & Fanaras, J. C. (2018). How much separation for LC–MS/MS quantitative bioanalysis of drugs and metabolites? Journal of Chromatography B, 1084, 23–35. 10.1016/j.jchromb.2018.03.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura‐Aguilar, R. I. , Bosquez‐Molina, E. , Bautista‐Baños, S. , & Rivera‐Cabrera, F. (2017). Cactus stem (Opuntia ficus‐indica Mill): Anatomy, physiology and chemical composition with emphasis on its biofunctional properties. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 97(15), 5065–5073. 10.1002/jsfa.8493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Q. Q. , Gan, R. Y. , Ge, Y. Y. , Zhang, D. , & Corke, H. (2018). Polyphenols in common beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.): Chemistry, analysis, and factors affecting composition. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety, 17, 1518–1539. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.08.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]