Abstract

Recently, multi-energy inter-pixel coincidence counter (MEICC) has been proposed for charge sharing correction and compensation for photon counting detectors (PCDs), which uses energy-dependent coincidence counters to record coincident events between multiple energy windows of a pixel-of-interest and those of neighboring pixels. A Monte Carlo (MC) simulation study was performed to assess the performance of MEICC; however, the performance might have been overestimated in a previous study. The charge sharing increases the number of photons recorded at a PCD pixel at the expense of the spatial resolution, and therefore, when spatially uniform flat-field x-ray signals are used, it gives PCDs with charge sharing more signals than a PCD without charge sharing. In this paper, we propose to use spatially modulated boxcar signals for evaluating the performances for high spatial frequency tasks because they provide consistent signals regardless of the presence of absence of charge sharing. The flat-field signals must be used for low spatial frequency tasks. We assessed the performances of MEICC and other PCDs with both flat-field signals and boxcar signals, with optimal threshold energies, and with two different pixel sizes. As it is expected, normalized Cramér–Rao lower bounds (nCRLBs) measured with the boxcar signals were worse than those with flat-field signals in general. The nCRLBs of MEICC with 225-μm pixel were close to the current 450-μm PCD. We studied a combination of flat-field signals and N×N super-pixels, where the output of N×N pixels were added, using an MC simulation and a simple charge sharing counting model. The study showed that charge sharing had two opposing impacts on the conventional CT imaging—a negative impact with double-counting among N×N pixels and a positive impact with single-counting spill-in and spill-out across the super-pixel boundary—and the positive impact diminished with increasing N. A use of large N×N super-pixels such as N≥25 was suggested to approximate the zero-frequency detection quantum efficiency of PCD with charge sharing.

Keywords: Computed tomography, photon counting detectors, charge sharing

I. Introduction

Photon counting detector (PCD)-based x-ray computed tomography (CT) has a great potential in many clinical applications [1–14]. One of the challenges for clinical whole-body PCD-CT is a spectral distortion in the PCD due to charge sharing (Fig. 1) and pulse pileup [1, 15]. With reasonably fast PCDs under a given x-ray intensity condition, pulse pileup is significant only when the attenuation by the object is small. An object attenuates x-rays very effectively, and therefore, the count rates for a majority of rays are very low even if the initial x-rays are intense (see Figs. 6 and 7 of Ref. [1]). In addition, using a low x-ray tube current for low-dose CT will mitigate pulse pileup further.

Fig. 1.

The top view along the x-ray path of 3×3 pixels (top row) and the side view (bottom row) with (A) no charge sharing (no cross-talk), (B) spill-out charge sharing, and (C) spill-in charge sharing. Eight neighbor pixels of a pixel-of-interest (POI) are considered as one neighboring area. Subscripts indicate one of 3 energy windows, L, M, or H for 20–50 keV, 50–80 keV, or ≥80 keV, respectively. CX and CCXY are counters and coincidence counters, respectively, for POI and CX and CCXY with underlines are those for one of neighboring pixels.

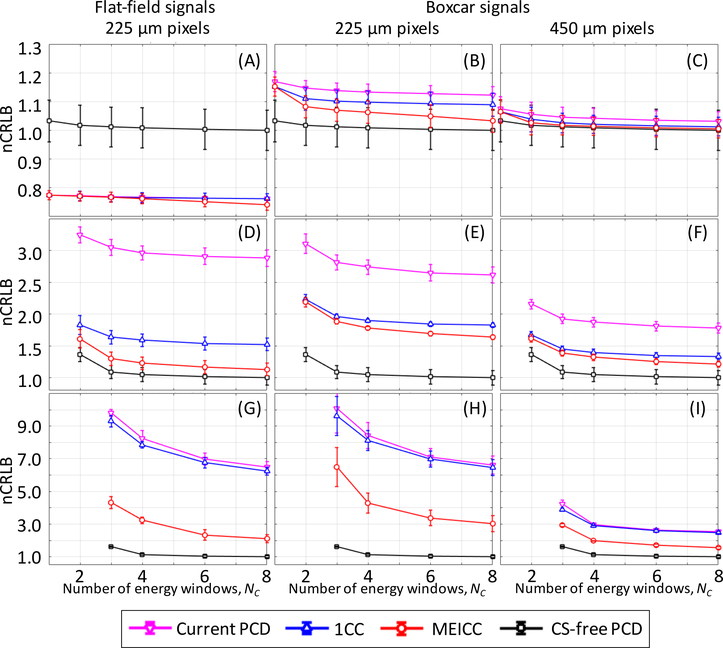

Fig. 6.

The results of single-pixel measurements. The nCRLB values for line integral estimation for conventional CT imaging (A–C), water thickness estimation for water–bone material decomposition (D–F), and gold thickness estimation for K-edge imaging (G–I). The results are with flat-field signals with 225-μm pixels (A, D, and G), spatially modulated boxcar signals with 225-μm pixels (B, E, and H), and boxcar signals with 450-μm pixels (C, F, and I). Error bars indicate standard deviations of nCRLB over three sets of 1,000 noise realizations. nCRLB = Cramér–Rao lower bound normalized by that of CS-free PCD with NC=8; PCD = photon counting detector; CS = charge sharing; 1CC = PCD with one coincidence counter; MEICC = the proposed, multi-energy inter-pixel coincidence counter.

Fig. 7.

Threshold energies that provided the least CRLB for the current PCD and the PCD with MEICC for K-edge imaging.

In contrast, charge sharing is impossible to avoid because it is inherent to the detection physics, and a probability of “charge sharing” is ~70% with a pixel size of 225 μm [15]. Note that we will use a loose definition of charge sharing in this paper, including fluorescence x-ray emission and its reabsorption. The use of larger pixels such as 1 mm could decrease the probability and mitigate charge sharing. However, larger pixels increase the x-ray photon’s incoming rate per pixel and make the problem of pulse pileup worse [1]. Given the current detector speed and x-ray intensity for clinical CT, the pixel size may need to be smaller than 1 mm [1], and consequently, the dominant cause of spectral distortion for most of x-ray beams is the charge sharing, which needs to be addressed.

Detectors that handle charge sharing have been proposed. Their schemes include an event-based real-time charge sharing correction [16–28] or rejection [29–31], an event-based post-acquisition correction [16], or a reading-based post-acquisition correction/compensation.

The event-based real-time charge sharing correction uses a sophisticated inter-pixel communication to recognize coincidence events, identify the primary incident pixel and the corresponding energy window, and add a count to the associated counter. Medipix3RX detector [16, 19] uses a charge summing process that could be explained as implicitly identifying coincident events, although the process is always active and no coincidence event is explicitly identified. The charge summing process of Medipix3RX works well when the incident count rate is low [16, 19]. The above described processing is integrated intricately with the primary counting process and the inter-pixel communication may take time, degrading the detector’s count rate capability significantly, e.g., by a factor of 10 for Medpix3RX. The event-based real-time charge sharing rejection uses a sophisticated inter-pixel communication to recognize coincidence events, then either reject coincidence events or set aside such events to a designated counter.

The event-based post-acquisition correction is implemented to Timepix3 [16]. It is essentially a list-mode acquisition and a huge data size may be an issue with applying it to CT: the number of events may be in the order of 1012 per CT scan.

Hsieh proposed a reading-based post-acquisition scheme with a use of one coincidence counter (which we call “1CC” in this paper) to record the number of double-counting events with neighboring pixels with no energy information [32, 33]. Being inspired by Hsieh’s 1CC, we recently proposed another scheme for reading-based post-acquisition correction/compensation called MEICC for multi-energy inter-pixel coincidence counter [34]. We will explain MEICC in Sec. II.A; briefly, MEICC records the spectral information of charge sharing events, while 1CC saves the intensity information.

The performance of MEICC was assessed using a Monte Carlo (MC) simulation and Cramér–Rao lower bound (CRLB) in the previous study [34]. The study found that the CRLBs of PCDs with MEICC were close to those of a PCD without charge sharing. The study, however, had the following three problems. First, the “flat-field signals” (explained later) were used, and as a consequence, we might have overestimated the performance of PCDs with charge sharing. This might be a general problem with the performance assessment of PCDs when neighboring pixels are spatio-energetically correlated due to charge sharing. A second problem was that the threshold energies were not optimized and a uniform energy window width for a given number of windows was used. Third, PCDs with one pixel size only were studied. As severity of charge sharing varies with pixel sizes, it is of interest to assess the performance of MEICC with different pixel sizes.

The aims of this paper were to address these problems for high spatial resolution tasks and to study a combination of flat-field signals and N×N super-pixels for low spatial resolution tasks. In Sec. II, we will outline the MC simulation settings, flat-field signals and a spatially modulated boxcar signals, N×N super-pixels, and a simple charge sharing counting models for analysis. The results will be presented in Sec. III and relevant issues will be discussed in Sec. IV, followed by conclusions in Sec. V.

II. Materials and Methods

We first briefly describe MEICC in Sec. II.A. We then outline two types of signals in Sec. II.B, two acquisition schemes in Sec. II.C, three imaging tasks for which we assessed the performance of PCDs in Sec. II.D, and the MC simulation and data processing schemes for single-pixel measurements in Secs. II.E and II.F, respectively, and those for super-pixel measurements in Sec. II.G, and finally, a simple charge sharing counting model is presented in Sec. II.H. Two PCD pixel sizes, 225 μm and 450 μm, were assessed in this study.

A. MEICC

We use a PCD with three energy windows to explain MEICC in this section. In addition to the standard counters for energy windows (i.e., CL, CM, and CH, see Fig. 2), MEICC uses a network of energy-dependent coincidence counters between energy windows of a pixel-of-interest (POI) and those of neighboring pixels, and records the spectral information of charge sharing events during data acquisition (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The basic architecture of a PCD pixel with MEICC. The neighboring pixels are treated as one area: one or more counts at any of the neighbor pixels will produce the same input to the AND logics. CX and CCXY are counters and coincidence counters, respectively, for a pixel-of-interest (POI), and CX and CCXY with underlines are those for one of neighboring pixels. Notice that a counter is associated with a two-sided energy window (not a one-sided threshold window) in this study. An underline indicates that it belongs to neighboring pixels. When a count is added coincidently to counter CX of the POI and counter CY of one of neighboring pixels, a count is also added to CCXY of the POI. In this case, a count is also added to a coincidence counter of the corresponding neighbor pixel, CCXY, as the circuitry for MEICC in each pixel processes coincidences with its own neighboring pixels independently and in parallel. This figure is from Ref. [34].

When a 90-keV photon is incident onto the POI and spill-out charge sharing occurs (Fig. 1B), the photon may leave 60 keV at the POI and 30 keV at one of the neighboring pixels. One count each will then be added to counter CM of the POI and counter CL of the neighboring pixel. With MEICC, a count will also be added to the coincidence counter of the POI, CCML, that are associated to CM and CL. Underlines indicate that it belongs to neighboring pixels. When spill-in charge sharing happens (Fig. 1C), a count each will be added to CL, CM, and CCLM. Notice that a higher energy is deposited at the incident pixel with charge sharing in most cases (Fig. 3), and therefore, the spectral coincidence counter provides the information on the direction of charge sharing (i.e., if the event was spill-out or spill-in). After the acquisition is completed, the number of events recorded in the standard counters and coincidence counters will be read-out. A post-acquisition algorithm will then be able to either correct or compensate for charge sharing effect using the exact number of charge sharing occurrences recorded in coincidence counters for each pair of energy windows. For example, compensation can be achieved by maximizing the likelihood function and estimating line integrals of basis functions, which is similar to the maximum likelihood (ML) method and the maximum-likelihood with a non-negativity constraint (ML+) presented in Ref. [35, 36] except that coincidence data for MEICC will be included.

Fig. 3.

Probabilities of recorded energy with a 90-keV photon. Previous studies on the spatio-energetic cross-talk showed that, with charge sharing, a photon is likely to deposit a higher energy at the incident pixel and a lower energy at its neighboring pixel(s).

Note that the coincidence counters in MEICC do not interfere with the primary counting process with the standard counters; therefore, PCDs with MEICC is expected to be as fast as those without MEICC. In contrast, event-based real-time charge sharing correction schemes discussed above do not have two separate sets of counters like MEICC. A set of counters is located after the anti-coincidence logics, and one of the counters will be incremented only after coincidence detection and processing is completed.

B. Boxcar Versus Flat-Field Signals

Flat-field signals—x-rays with the same expected intensity and spectrum are incident onto a group of PCD pixels (Fig. 4A, left)—have been used in many studies when the performance of PCDs is evaluated. The CRLB is computed with tiny changes being applied to x-rays for all of the PCD pixels. When charge sharing between neighboring pixels are present, a POI receives more photons that reflect the signals to be detected via spill-in charge sharing than a PCD with no charge sharing (Fig. 4B, left). In other words, charge sharing increases the effective area of PCD pixels. This leads to unphysical, counter-intuitive results when the flat-field scheme is used to assess the performance of one pixel (see Secs. III.A–III.C). The flat-field scheme must be used to assess low spatial frequency imaging tasks or the zero-frequency detection quantum efficiency (DQE) of the PCD, and it must be used with N×N super-pixels (discussed in Sec. II.C). We will study this combination in Secs. II.G and II.H.

Fig. 4.

(A) Views from the top. Flat-field signals change x-ray spectrum and intensity incident onto all of the pixels from condition 1 to condition 2, while boxcar signals changes x-rays onto the pixel-of-interest (POI) only. Condition 1 refers to the baseline spectrum and condition 2 refers to the target spectrum (see Secs. II.D–II.F). (B) Side views. The lines and spheres are x-rays and electronic charge clouds; those in blue and red are generated with conditions 1 and 2, respectively. Numbers are the number of counts produced at the POI. With the flat-field scheme, the POI of PCD with charge sharing (CS) counts five events with condition 2 including two additional events via spill-in charge sharing from neighboring pixels, which is more than the CS-free PCD counts (i.e., three events). In contrast, with the boxcar scheme, the PCD with charge sharing counts three events with condition 2, which is the same as CS-free PCD does. The additional two events with condition 1 come into the POI via spill-in and degrade the signal-to-noise ratio of data. (C) A square hole grid pattern, which could be used to measure the DQE at the Nyquist frequency of the PCD, includes the boxcar signal pattern.

We propose to use spatially contained boxcar signals, where x-rays incident onto the POI only change from the baseline spectrum to the target spectrum, while x-rays incident onto other pixels remain unchanged at the baseline spectrum (Fig. 4A, right) [37]. Regardless of the presence or absence of charge sharing, the CRLB is computed with the same amount of signals using this scheme (see Fig. 4B, right). We believe this is a better scheme to be used to assess the performance of PCDs for high spatial resolution imaging tasks. In fact, the boxcar signal is a part of a square hole grid pattern (Fig. 4C), which can be used to measure the DQE at the Nyquist frequency of the PCD. It is not suitable to combine an N×N super-pixel with boxcar signals because an N×N super-pixel (discussed later) is a low spatial resolution measurement scheme and boxcar signals are designed for high spatial resolution assessments.

C. Single-Pixels and N×N Super-Pixels

We evaluated the output of the POI (which is also called a single-pixel in this paper) as well as an N×N super-pixel with N=2,3,4,5, where the output of N×N pixels were added to create the output of one large pixel. Given that super-pixels would not be used for high resolution imaging tasks, the flat-field scheme was used to assess the performance of super-pixels.

D. Three Physics Tasks

We used the following three different physics tasks with different dimensionality that are relevant to three clinical applications in this study: the line integral estimation of water for the conventional CT imaging, water thickness estimation for water–bone material density imaging, and gold thickness estimation for K-edge imaging with water–bone–gold material decomposition. Note that the conventional CT imaging is a 1-dimensional estimation problem and is different from monochromatic CT imaging used in [34] that is a 2-dimensional estimation problem followed by a weighted summation of the estimated two parameters to synthesize a line integral at a desirable energy.

E. Monte Carlo Simulations for Single-Pixel Measurements

The in-house MC program we developed in the previous study [34] was modified to allow for the use of boxcar signals. This MC program cascades the following processes and is essentially a stochastic version of Photon Counting Toolkit (PcTK) [15, 38] with pre-computed look-up tables, which had excellent agreement with another MC simulation and a PCD [15, 39]: (1) photon generations with randomized energies and time intervals for a Poisson distribution, (2) charge sharing based on a randomized location and interaction and detection processes, (3) pulse train generations with electronic noise, (4) comparator signal generation by pulse height analyzers with set energy thresholds, and (5) counting and coincidence processing. Out of 5×5 pixels, photons were randomly incident onto only the central 3×3 pixels and the above processes were performed for each pixel in parallel. The MC program outputs the counts saved at counters and coincident counters for the POI. For step (2), the interaction types were either no detection, the photoelectric effect with total absorption, the photoelectric effect with K-escape, or the photoelectric effect with re-absorption of fluorescence x-ray. Triple- and quadruple-counting were also included. Neither Compton scattering nor Rayleigh scattering was included and the number of interactions was limited to one, because the probability was low for diagnostic energies [15]. An impulse pulse was used in step (3) and no pulse pileup was included in this study.

X-rays were operated at 140 kVp and 50 mA and a time duration per reading was 45 ms. Three sets of 1,000 noise realizations (thus, 3,000 noise realizations in total) were acquired for a given spectrum and a PCD type. The baseline spectrum was set with the attenuation by 10 cm water and 1 cm bone, resulting in ~21,000 incident photons per pixel per reading on average; three target spectra were set by adding a tiny amount of either water, bone, or gold to the baseline.

We simulated cadmium telluride PCD with a pixel size of either (225 μm)2 or (450 μm)2, a thickness of 1.6 mm, and electronic noise with a standard deviation of 2.0 keV added to a pulse train (not to threshold energies). The following four PCD types were assessed: (1) The current PCD with no additional schemes to address charge sharing; (2) a PCD with 1CC; (3) a PCD with MEICC; and (4) the “charge sharing(CS)-free PCD” with no charge sharing but all of the other factors such as electronic noise, K-escape through either front or back side of the PCD, and non-perfect detection efficiency. The CS-free PCD is similar to a PCD with a very large pixel. The number of energy windows (NC) was 2, 3, 4, 6, and 8; the number of coincidence counters for MEICC (NCC) was NC2; all of the eight neighbors were used for MEICC and 1CC; and the optimal threshold energies with the lowest CRLB for a given setting were found by performing an exhaustive search with a 5-keV increment from 20 keV to 135 keV. The number of entries for the data vector per noise realization was NC for both the CS-free and the current PCDs, NC+1 for 1CC, and NC+NC2 for MEICC. The output data from the POI only was used for single-pixel measurements; no data from the neighboring pixels were used.

F. Data Processing for Single-Pixel Measurements

The following procedure was used for data processing, which is the same as the previous study [34] and similar to other studies [40, 41]. The mean and covariance of PCD data over 1,000 noise realizations were calculated. The Fisher information matrix was computed numerically with two assumptions: (1) counts were multivariate normally distributed; and (2) covariance remained unchanged with an additional tiny amount of attenuator. We think that assumption (1) can be justified as most of energy windows had the mean counts larger than 100 counts. Assumption (2) stabilized the computation at the expense of a possible overestimation of CRLB. The size of Fisher information matrix was 1×1 for the conventional CT imaging, 2×2 for water–bone material decomposition, and 3×3 for K-edge imaging. The inverse of Fisher information matrix was computed. The CRLB of the variance of each basis material was the corresponding diagonal element of the inverse matrix. An unbiased sample standard deviation of CRLB values over the three sets of 1,000 noise realizations was computed. All of the CRLB values were then normalized by the mean CRLB of the CS-free PCD with 8 energy windows, which were denoted by nCRLB.

We make one comment on the conventional CT imaging setting. Even though water and bone were used to attenuate the original spectrum and synthesize the baseline spectrum, the use of two basis materials is nothing to do with the dimensionality of the estimation problem. The target spectrum for the conventional CT imaging was synthesized by adding water only to the baseline condition. The problem setting was to compute the minimum noise variance in estimating the added water thickness without biases, and thus, it is a 1-dimensional estimation problem and there is neither model error nor model–data mismatch. Thus, there exists an unbiased estimator, and therefore, the use of CRLB is justified.

G. Monte Carlo Simulations and Data Processing for Super-Pixel Measurements

The MC simulation settings and the data processing scheme were the same as those used for single-pixel measurements (Sec. II.E) except for the following few changes.

There were 9×9 pixels, out of which photons were randomly incident onto the central 7×7 pixels. The pixel size with (225 μm)2 only was used. The time duration per reading was 0.2 ms and six sets of 500 noise realizations (thus, 3,000 noise realizations in total) were acquired for a given spectrum and a PCD type. The shorter acquisition time was necessary to make the computation time manageable. The number of energy windows (NC) was 2, 3, 4, and 6. Neither MEICC with any NC nor NC=8 with any PCD types was used because the mean counts for some primary counters and many coincidence counters were less than 30 counts. The outputs of the central N×N pixels with N=1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 were added to create the output of one N×N super-pixel per reading. The number of entries for the super-pixel data vector per noise realization was the same as that of the single-pixel measurements. The CRLB values were normalized by that of the CS-free PCD with NC=6.

H. A Study on Flat-Field Signals and N×N Super-Pixels

In this section, we used a charge sharing counting model to study the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of N×N super-pixel measurements with flat-field signals for the conventional CT imaging task; the model took into account the effect of both “double-counting” and cross-boundary charge sharing. When one photon is counted by two pixels within the N×N pixels, it is called double-counting and increases the noise of the super-pixel data relative to the signal.

Let us consider N×N super-pixels and flat-field signals with an incident rate of 1 photon per reading. Suppose that when a photon is incident onto a PCD pixel and detected, a probability of no charge sharing is 1–4w and a probability of charge sharing with one of the four neighbors is w (Fig. 5A). The expected number of events with no charge sharing (hence, single-counting events), sc1, can be computed by

| (1) |

as there are N2 pixels inside the super-pixel. The expected number of events with charge sharing between two pixels across the boundary of the super-pixel (Fig. 5B), sc2, can be calculated by

| (2) |

The probability for each pixel edge is 2w because it is a two-way cross-talk with both spill-out (from the super-pixel to its neighbors) and spill-in (from one of the neighbor pixels to the super-pixel) and there are 4N edges along the super-pixel boundary. These events are counted only once by the super-pixel; hence, they are single-counting events in this analysis. Now the expected number of charge sharing events between two of pixels within the super-pixel (Fig. 5B), dc, is

| (3) |

Fig. 5.

(A) When a photon is incident onto a PCD pixel, a probability of no charge sharing is 1–4w. Double-counting may occur between the primary pixel and one of its four neighboring pixels, each with a probability of w. Note that an arrow points from the primary pixel to the destination pixel. (B) A 3×3 super-pixel and all of the possible charge sharing events that involve the super-pixel. Magenta arrows indicate double-counting between two pixels inside the super-pixel. In contrast, blue arrows denote double-counting across the super-pixel boundary, and therefore, only one count each is registered by the super-pixel. Thus, it is a single-counting event as far as the super-pixel is concerned.

The expected signal S and the variance V can be calculated by taking into account the double-counting:

| (4) |

| (5) |

The SNR and the SNR normalized by that of the CS-free N×N super-pixels (nSNR) with the same N can be computed as follows.

| (6) |

| (7) |

The nSNR’s at various N and w were computed in this study.

III. Results

A. Conventional CT Imaging (Single-Pixels)

When the flat-field signals were used with single-pixel measurements and optimal threshold energies (Fig. 6A and Table I), the nCRLBs of all of the PCDs with charge sharing were at 0.74–0.77 and better than the CS-free PCD (1.00–1.02), because the primary information necessary for the conventional CT imaging task performance was the x-ray intensities (i.e., the area-under-the-spectrum-curve); and therefore, receiving more photons outweighed the spectral distortion due to charge sharing.

TABLE I.

Normalized Cramér–Rao Lower Bound Line Integral Estimation for Conventional CT Imaging

| Flat field signals 225 μm, NC | Boxcar signals, 225 μm, NC | Boxcar signals, 450 μm, NC | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 8 | |||

| Current PCD | 0.77 | 0.77 | 0.77 | 0.76 | 0.76 | 1.15 | 1.14 | 1.13 | 1.13 | 1.09 | 1.06 | 1.05 | 1.04 | 1.04 | 1.03 | ||

| 1CC | 0.77 | 0.77 | 0.77 | 0.76 | 0.76 | 1.11 | 1.10 | 1.10 | 1.09 | 1.09 | 1.04 | 1.03 | 1.02 | 1.02 | 1.01 | ||

| MEICC | 0.77 | 0.77 | 0.76 | 0.75 | 0.74 | 1.08 | 1.07 | 1.06 | 1.05 | 1.03 | 1.03 | 1.02 | 1.01 | 1.01 | 1.00 | ||

| CS-free PCD | 1.02 | 1.01 | 1.01 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.02 | 1.01 | 1.01 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.02 | 1.01 | 1.01 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

PCD = Photon Counting Detector; NC = Number of energy bins; 1CC = One Coincidence Counter; MEICC = Multi-energy inter-pixel coincidence counter.

Figure 6B shows the nCRLB with 225-μm PCD single-pixels measured using the boxcar signals. The nCRLBs of PCDs with charge sharing were higher than the CS-free PCD; for example, the nCRLB with NC=6 was 1.05 for MEICC, 1.09 for 1CC, 1.13 for the current PCD, and 1.00 for the CS-free PCD. The MEICC decreased the noise variance by 7% [=(1–1.05/1.13) × 100%] from the current PCD and was more effective than 1CC, which decreased the noise by 4%. It showed that the spectral information of charge sharing MEICC captured was somewhat valuable even for a non-spectral task. The nCRLB was almost constant over NC.

Figure 6C presents the nCRLBs with 450-μm PCD single-pixels measured using the spatially modulated boxcar signals. Qualitative observations were similar to those with 225-μm pixel, although all of the PCDs with charge sharing had nCRLB values that were very close to the CS-free PCD because the 450-μm pixel had less charge sharing than the 225-μm pixel did.

B. Water–Bone Material Density Imaging (Single-Pixels)

Figure 6E and Table II show the nCRLB of water thickness estimation for water–bone material density imaging with 225-μm PCD single-pixels, the boxcar signals, and the optimal threshold energies. Results of bone thickness estimation was very similar to water, thus, not presented. With all of PCDs, the nCRLB improved with increasing NC and the largest improvement was obtained when NC was increased from two to three: the relative improvements were 14% [=(2.19–1.89)/2.19 × 100%] for MEICC, 12% for 1CC, 10% for the current PCD, and 20% for the CS-free PCD. For a given NC with the boxcar signals, both MEICC and 1CC were at about a halfway between the current PCD and the CS-free PCD (with MEICC being slightly better than 1CC).

TABLE II.

Normalized Cramér–Rao Lower Bound for Water Thickness Estimation for Water–Bone Material Density Imaging

| Flat field signals 225 μm, NC | Boxcar signals, 225 μm, NC | Boxcar signals, 450 μm, NC | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 8 | |||

| Current PCD | 3.25 | 3.05 | 2.96 | 2.91 | 2.88 | 3.11 | 2.81 | 2.74 | 2.65 | 2.62 | 2.16 | 1.93 | 1.87 | 1.81 | 1.78 | ||

| 1CC | 1.83 | 1.64 | 1.59 | 1.59 | 1.52 | 2.23 | 1.96 | 1.90 | 1.84 | 1.83 | 1.67 | 1.45 | 1.40 | 1.35 | 1.34 | ||

| MEICC | 1.61 | 1.30 | 1.23 | 0.76 | 0.76 | 2.19 | 1.89 | 1.78 | 1.69 | 1.64 | 1.62 | 1.39 | 1.32 | 1.26 | 1.22 | ||

| CS-free PCD | 1.36 | 1.09 | 1.05 | 1.01 | 1.00 | 1.36 | 1.09 | 1.05 | 1.01 | 1.00 | 1.36 | 1.09 | 1.05 | 1.01 | 1.00 | ||

PCD = Photon Counting Detector; NC = Number of energy bins; 1CC = One Coincidence Counter; MEICC = Multi-energy inter-pixel coincidence counter.

With the flat-field signals (Fig. 6D), the nCRLBs of both MEICC and 1CC were much closer to that of the CS-free PCD than with the boxcar signals (Fig. 6E), simply because the effective pixel area of PCDs with charge sharing was larger due to charge sharing.

Figure 6F shows the nCRLB with 450-μm PCD pixels. Again, qualitative observations were similar to those with 225-μm pixel; however, all of the PCDs with charge sharing with 450-μm pixels had much better nCRLB values, closer to the CS-free PCD. The nCRLBs with 225-μm pixel MEICC were 1.64–2.19 and comparable to those with 450-μm pixel with the current PCD (1.78–2.16).

C. K-edge Imaging (Single-Pixels)

Figure 6H and Table III show the nCRLB of gold thickness estimation for K-edge imaging with 225-μm PCD single-pixels, the boxcar signals, and the optimal threshold energies. With all of PCDs, the nCRLB improved with increasing NC more significantly than the other tasks, probably because K-edge imaging demands the accuracy of the spectral information the most. The nCRLB of MEICC with the boxcar signals improved by 2.22 (=6.50–4.28) or 34% (=2.22/6.50 × 100%) from 3 windows to 4 windows, and 1.00 or 23% from 4 windows to 6 windows. The improvement with the current PCD was by 1.64 (=10.07–8.43) or 16% (1.64/10.07 × 100%) from 3 windows to 4 windows, and 1.32 or 16% from 4 windows to 6 windows. For a given NC with NC≥4, MEICC was at about a halfway between the current PCD and the CS-free PCD or somewhat closer to the CS-free PCD.

TABLE III.

Normalized Cramér–Rao Lower Bound for Gold Thickness Estimation for K-Edge Imaging

| Flat field signals 225 μm, NC | Boxcar signals, 225 μm, NC | Boxcar signals, 450 μm, NC | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 8 | |||

| Current PCD | 9.81 | 8.24 | 6.98 | 6.48 | 10.07 | 8.43 | 7.11 | 6.62 | 4.21 | 2.97 | 2.64 | 2.54 | |||||

| 1CC | 9.31 | 7.85 | 6.76 | 6.25 | 9.61 | 8.12 | 6.98 | 6.46 | 3.88 | 2.92 | 2.59 | 2.49 | |||||

| MEICC | 4.32 | 3.23 | 2.34 | 2.10 | 6.50 | 4.28 | 3.28 | 3.03 | 2.94 | 1.98 | 1.70 | 1.55 | |||||

| CS-free PCD | 1.61 | 1.14 | 1.04 | 1.00 | 1.61 | 1.14 | 1.04 | 1.00 | 1.61 | 1.14 | 1.04 | 1.00 | |||||

PCD = Photon Counting Detector; NC = Number of energy bins; 1CC = One Coincidence Counter; MEICC = Multi-energy inter-pixel coincidence counter.

Figure 6I presents the nCRLB with 450-μm pixels. Once again, qualitative trends remained the same as 225-μm pixels and all of the PCDs with charge sharing were closer to the CS-free PCD than 225-μm’s counterparts. The nCRLBs with 225-μm pixel MEICC were close to those with 450-μm pixel with the current PCD: 3.03–6.50 versus 2.54–4.21.

Figure 7 shows optimal threshold energies for MEICC and the current PCD with 225-μm pixels, averaged over 3 sets of 1,000 noise realizations. The current PCD with 3 windows set the lowest threshold energy at 63 keV, threw away all of the photons between 20 keV and 62 keV, and focused on acquiring photons only near the K-edge where the K-edge signals were the strongest even with spectral distortion. In contrast, MEICC with 3 windows set two windows below the K-edge and utilized all of the photons over 20–140 keV. MEICC used the spectral information of charge sharing and decreased the noise of K-edge imaging. The optimal threshold energies for 1CC were very similar to those of the current PCD. The optimal threshold energies for 450-μm pixel PCDs with charge sharing were almost identical to those for 225-μm pixel PCDs: The unique and different allocations of energy windows were consistent regardless of the amount of charge sharing.

D. Super-Pixel Measurements

Figure 8 shows the results of N×N super-pixel measurements with N=1–5. It can be seen that the nCRLBs of the conventional CT imaging (Figs. 8A–8E) increased from N=1 to N=4. The nCRLBs with NC=1 were 0.87, 1.09, 1.16, 1.20, 1.13 for the current PCD and 0.86, 1.04, 1.08, 1.10, 1.03 for 1CC, both for N=1, 2, 3, 4, 5, respectively. The nCRLBs of 1CC for the K-edge imaging (Figs. 8K–8O) showed a consistent increase with N as well: The nCRLBs with NC=3 were 4.75, 6.06, 7.13, 7.81, 8.47 for N=1, 2, 3, 4, 5, respectively.

Fig. 8.

The results of N×N super-pixel measurements with flat-field signals. The nCRLB values for line integral estimation for conventional CT imaging (A–E), water thickness estimation for water–bone material decomposition (F–J), and gold thickness estimation for K-edge imaging (K–O). Error bars indicate standard deviations of nCRLB over six sets of 500 noise realizations. nCRLB = Cramér–Rao lower bound normalized by that of the CS-free PCD with NC=6; PCD = photon counting detector; CS = charge sharing; 1CC = PCD with one coincidence counter; NC = The number of energy windows.

In contrast, the nCRLBs of the water thickness estimation (Figs. 8F–8J) increased from N=1 to N=2, then the changes between N=2 and N=5 were small and not consistent. The differences in performances between these three tasks may be attributed to the differences in how they were affected by both the noise penalty in double-counting within each energy window (negatively) and the spectral information carried by both spill-in and spill-out charge sharing events (positively).

E. A Study on Flat-Field Signals and N×N Super-Pixels

Figure 9 shows nSNRs computed by the counting model. We made the following four observations. First, the nSNRs with w>0 were larger and better than 1 when N=1, and then decreased monotonically with increasing N (Fig. 9A). Second, the speed of the decreasing was slow, especially with larger w, and it needed a large N for an nSNR to get close to the “converged value.” If the nSNRs with N=1,000 were set to be the converged values, the minimum value of N necessary to be within 0.01 from the converged values is 12, 18, 21, 23, and 25 for w=0.05, 0.10, 0.15, 0.20, and 0.25, respectively. Third, a PCD with w=0.25, which has 100% charge sharing, provided nSNR>1, and is always better than the PCD with w=0 (the CS-free PCD). A noise penalty due to double-counting were outweighed by a large number of spill-in signals coming from outside the super-pixel boundary. Fourth, when N=1,000, the least and worst nSNR was 0.9430 at w=0.0832 (Fig. 9B), and PCDs with severer charge sharing (i.e., w>0.0832) had better nSNRs. It demonstrated an interesting balancing act of charge sharing with the negative impact with double-counting among N×N pixels and the positive impact with single-counting spill-in and spill-out across the super-pixel boundary.

Fig. 9.

The normalized signal-to-noise ratio (nSNR) of super-pixel data with flat-field signals computed by the model. The nSNR values with N=1,000 were 1.000, 0.970, 0.949, 0.944, 0.956, 0.976, and 1.000 with w=0.00, 0.02, 0.05, 0.10, 0.15, 0.20, and 0.25, respectively.

The first observation outlined above agreed with the results of the super-pixel MC simulation (Figs. 8A–8E). For N×N super-pixels of the current PCD with NC=1, the inverse square-root of the nCRLBs relative to those of the CS-free PCD were 1.10, 0.98, 0.95, 0.93, 0.95 for N=1, 2, 3, 4, 5, respectively, whereas the nSNRs of the model with w=0.05 were 1.10, 1.01, 0.99, 0.98, 0.97 for N=1, 2, 3, 4, 5, respectively. The changes with N agreed to each other: The linear correlation coefficient (R) between the current PCD and the model with w=0.05 was 0.986 (P=0.002).

IV. Discussion

PCDs with MEICC were at about a halfway between the current PCD and the CS-free PCD for a given pixel size. MEICC with 225-μm pixel was close to the current 450-μm PCD: nCRLB=1.01–1.12 for 225-μm MEICC versus 1.00–1.12 for the current 450-μm PCD for the conventional CT imaging; 1.64–2.19 versus 1.78–2.16 for water–bone material decomposition; and 3.03–6.50 versus 2.54–4.21 for K-edge imaging.

The use of the boxcar signals has the following two merits. First, it allows for the assessment of the CRLB using the same amount of signals regardless of the presence or absence of charge sharing. With the boxcar signals, spill-in counts coming from the neighboring pixels are noise that disturbs signal detections. In contrast, the use of the flat-field signals underestimates the variance, because spill-in counts increase signals, which led to the counter-intuitive result with the conventional CT imaging: PCDs with charge sharing were better than the CS-free PCD. Second, it allows for the assessment of the system performance at high spatial frequencies, which is a valuable complement to the zero-frequency performance that can be assessed by using the flat-field signals and N×N super-pixels with a large N.

The analysis using the simple counting model of charge sharing showed that the boundary effect of super-pixel with flat-field signals might be larger than many might have anticipated previously. It is suggested to use a large super-pixel, e.g., 25×25 pixels, to approximate the zero-frequency DQE of PCDs. The MC results with super-pixels agreed with the model analysis. The nCLRB increased with increasing N for the conventional CT imaging task and even the rank order of PCDs was not consistent with increasing N. There were differences among the three spectral tasks in how increasing N affected nCRLBs, and it may be attributed to how the spectral information critical for each task was affected by the negative and positive impacts of charge sharing, i.e., noise penalty in double-counting within energy windows and the spectral signal gain via cross-boundary spill-in charge sharing.

The use of spatially modulated signals for spatially and energetically correlated PCD outputs has also been studied by others recently. Zheng, et al. [42] also used the boxcar signals to assess the signal-difference-to-noise ratio with PCDs with charge sharing. Rajbhandary, et al., proposed a use of sinusoidal modulation of object thickness at frequency f to measure the spectroscopic DQE, DQEs(f) [43]. We believe that it is very important to use spatially modulated signals, not flat-field signals, in the assessment of PCDs and PCD-CT for high spatial frequency tasks.

The nSNR computed by the charge sharing counting model is a DQE(0)-like index with a finite N×N pixels and it asymptotically approaches the DQE(0) as increasing N. The nSNR will asymptotically approach (1+4w)/(1+12w)1/2 as N→∞, which agrees with the analytical form of the DQE(f) of PCDs developed by Stierstorfer in [39]: By substituting p010=1–4w, p110=4w, p100=0, and Γ(0,0)=1 for f=0 to Eq. (31) of Ref. [39], we get DQE(0)=(1+4w)2/(1+12w). It can also be shown by taking a derivative that the minimum value of the asymptotic nSNR can be analytically found as 2×sqrt(2)/3≈0.9428 at w=1/12=0.0833, and that is very close to the minimum nSNR value and the minimum point (i.e., 0.9430 at w=0.0832) of the model with N=1,000 presented in Sec. III.E.

The study had the following four limitations. First, no pileup was considered in this study. In the real world, there is a tradeoff between charge sharing and pileup when PCDs with different pixel sizes are assessed. Nonetheless, we believe that this study provided valuable results with two pixel sizes, which serve as a baseline for a given pixel size operated at an extremely low-dose. We shall investigate the tradeoff of the two effects with different pixel sizes and x-ray intensities in the future. Second, the study setting has eliminated false coincidences at high count rates. When count rates are high, coincidence pulses generated by two independent photons incident onto neighboring pixels may be mistreated as charge sharing and a count may be registered to a coincidence counter. This is called false coincidence and it would degrade the performance of MEICC and 1CC. We shall investigate it in the future as well. Third, different baseline spectra such as kVp, filter, and attenuation may change nCRLB values, although we expect that rank orders of PCDs will be consistent. One may wish to use other non-K-edge materials such as fat for the baseline spectrum. We argue that any non-K-edge materials are covered by the water and bone used in this study. For example, using the material decomposition, the attenuation with fat at energy E is practically equivalent to a weighted summation of water and bone as μfat(E) ≈ 1.010 μWater(E)–0.044 μBone(E). Thus, the object with 10 cm of water and 1 cm of bone is nearly equivalent to a combination of xf cm of fat, (10–1.010 xf) cm of water, and (1+0.044 xf) cm of bone. Fourth, algorithms that use MEICC data and either correct or compensate for the charge sharing effect need to be developed and assessed. We shall leave it to a future study.

V. Conclusion

The use of boxcar signals allows for the performance assessment of various PCDs for high spatial frequency tasks with consistent signals regardless of the presence or absence of charge sharing between adjacent PCD pixels. The spectral charge sharing information MEICC records decreases the nCRLB significantly and makes PCDs with MEICC a halfway between the current PCD and the CS-free PCD for a given pixel size. MEICC with 225-μm PCD is found either comparable to or close to the current 450-μm PCD for various spectral tasks. A combination of flat-field signals and N×N super-pixels must be used for low spatial frequency tasks; and N needs to be as large as or larger than 25 in order to approximate the zero-frequency DQE.

Acknowledgment

The author thanks Scott S. Hsieh, Ph.D. of Mayo Clinic for his excellent presentation and insightful discussion on the one coincidence counter at the Fifth Workshop on Medical Application of Spectroscopic X-ray Detectors at CERN (Geneva, Switzerland) [32]. The author is also grateful for Dr. Karl Stierstorfer of Siemens Healthineers for the discussion on the agreement between the DQE(0) in Ref. [39] and the asymptotic form of the nSNR by the model. Finally, the author thanks an anonymous referee for suggesting the analytical derivative of the asymptotic form.

This work was supported in part by the N.I.H. under Grant R21 EB029739 and Siemens Healthineers (Forchheim, Germany).

References

- [1].Taguchi K and Iwanczyk JS, "Vision 20/20: Single photon counting x-ray detectors in medical imaging," Medical Physics, vol. 40, no. 10, p. 100901, 2013. [Online]. Available: 10.1118/1.4820371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Leng S et al. , "Dose-efficient ultrahigh-resolution scan mode using a photon counting detector computed tomography system," (in eng), Journal of medical imaging (Bellingham, Wash.), vol. 3, no. 4, p. 043504, October 2016, doi: 10.1117/1.jmi.3.4.043504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Pourmorteza A, Symons R, Henning A, Ulzheimer S, and Bluemke DA, "Dose Efficiency of Quarter-Millimeter Photon-Counting Computed Tomography: First-in-Human Results," Investigative Radiology, vol. 53, no. 6, pp. 365–372, 2018, doi: 10.1097/rli.0000000000000463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Gutjahr R et al. , "Human Imaging With Photon Counting-Based Computed Tomography at Clinical Dose Levels: Contrast-to-Noise Ratio and Cadaver Studies," (in eng), Investigative Radiology, vol. 51, no. 7, pp. 421–9, July 2016, doi: 10.1097/rli.0000000000000251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Pourmorteza A et al. , "Abdominal Imaging with Contrast-enhanced Photon-counting CT: First Human Experience," Radiology, vol. 279, no. 1, pp. 239–245, 2016, doi:: 10.1148/radiol.2016152601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Yu Z et al. , "Noise performance of low-dose CT: comparison between an energy integrating detector and a photon counting detector using a whole-body research photon counting CT scanner," Journal of Medical Imaging, vol. 3, no. 4, pp. 043503–043503, 2016, doi: 10.1117/1.JMI.3.4.043503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Yu Z et al. , "How Low Can We Go in Radiation Dose for the Data-Completion Scan on a Research Whole-Body Photon-Counting Computed Tomography System," (in eng), J Comput Assist Tomogr, vol. 40, no. 4, pp. 663–70, Jul-Aug 2016, doi: 10.1097/rct.0000000000000412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Symons R et al. , "Feasibility of Dose-reduced Chest CT with Photon-counting Detectors: Initial Results in Humans," Radiology, vol. 285, no. 3, pp. 980–989, 2017, doi: 10.1148/radiol.2017162587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Roessl E and Proksa R, "K-edge imaging in x-ray computed tomography using multi-bin photon counting detectors," Physics in Medicine and Biology, vol. 52, no. 15, pp. 4679–4696, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Feuerlein S et al. , "Multienergy Photon-counting K-edge Imaging: Potential for Improved Luminal Depiction in Vascular Imaging," Radiology, vol. 249, no. 3, pp. 1010–1016, 2008. [Online]. Available: http://radiology.rsnajnls.org/cgi/content/abstract/249/3/1010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Pan D et al. , "Computed Tomography in Color: NanoK-Enhanced Spectral CT Molecular Imaging," Angewandte Chemie International Edition, vol. 49, no. 50, pp. 9635–9639, 2010. [Online]. Available: 10.1002/anie.201005657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Cormode DP et al. , "Atherosclerotic Plaque Composition: Analysis with Multicolor CT and Targeted Gold Nanoparticles," Radiology, vol. 256, no. 3, pp. 774–782, July 28, 2010. 2010. [Online]. Available: http://radiology.rsna.org/content/256/3/774.abstract [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Symons R et al. , "Dual-contrast agent photon-counting computed tomography of the heart: initial experience," The International Journal of Cardiovascular Imaging, journal article pp. 1–9, 2017, doi: 10.1007/s10554-017-1104-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Taguchi K, "Energy-sensitive photon counting detector-based X-ray computed tomography," Radiological Physics and Technology, journal article vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 8–22, 2017, doi: 10.1007/s12194-017-0390-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Taguchi K, Stierstorfer K, Polster C, Lee O, and Kappler S, "Spatio - energetic cross - talk in photon counting detectors: Numerical detector model (PcTK) and workflow for CT image quality assessment," Medical Physics, vol. 45, no. 5, pp. 1985–1998, 2018, doi: : 10.1002/mp.12863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Ballabriga R et al. , "Review of hybrid pixel detector readout ASICs for spectroscopic X-ray imaging," Journal of Instrumentation, vol. 11, no. 01, p. P01007, 2016. [Online]. Available: http://stacks.iop.org/1748-0221/11/i=01/a=P01007. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Ballabriga R, Campbell M, Heijne EHM, Llopart X, and Tlustos L, "The Medipix3 Prototype, a Pixel Readout Chip Working in Single Photon Counting Mode With Improved Spectrometric Performance," Nuclear Science, IEEE Transactions on, vol. 54, no. 5, pp. 1824–1829, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Ullberg C, Urech M, Weber N, Engman A, Redz A, and Henckel F, Measurements of a dual-energy fast photon counting CdTe detector with integrated charge sharing correction (SPIE Medical Imaging). SPIE, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Koenig T et al. , "Charge Summing in Spectroscopic X-Ray Detectors With High-Z Sensors," Nuclear Science, IEEE Transactions on, vol. 60, no. 6, pp. 4713–4718, 2013, doi: 10.1109/tns.2013.2286672. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Nygard E, Yamakawa T, and Nakamura N, "Readout Circuit for a Charge Detector," U.S.A. Patent 6,590,215 B2 2003.

- [21].Blevis IM, Rubin D, Zarechin O, and Verbakel F, "Direct Conversion Radiation Detector Digital Signal Processing ELectronics," U.S.A. Patent 9,784,854 B2 2017.

- [22].Macias-Montero J-G et al. , "ERICA: an energy resolving photon counting readout ASIC for X-ray in-line cameras," Journal of Instrumentation, vol. 11, no. 12, p. C12027, 2016, doi: 10.1088/1748-0221/11/12/C12027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Hsieh SS and Sjolin M, "Digital count summing vs analog charge summing for photon counting detectors: A performance simulation study," Medical Physics, vol. 45, no. 9, pp. 4085–4093, 2018, doi: 10.1002/mp.13098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Viswanath R, Surendranath N, and Parupudi RKV, "Photon couounting with coincidence detection," U.S.A. Patent 10,024,979 B1, 2018.

- [25].Lundqvist TM, "Method and Arrangement Relating to X-ray Imaging," U.S.A. Patent 6,559,453 B2 2003.

- [26].Maj P et al. , "Measurements of Matching and Noise Performance of a Prototype Readout Chip in 40 nm CMOS Process for Hybrid Pixel Detectors," IEEE Transactions on Nuclear Science, vol. 62, no. 1, pp. 359–367, 2015, doi: 10.1109/TNS.2014.2385595. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Bellazzini R et al. , "PIXIE III: a very large area photon-counting CMOS pixel ASIC for sharp X-ray spectral imaging," Journal of Instrumentation, vol. 10, no. 01, pp. C01032–C01032, 2015/01/22 2015, doi: 10.1088/1748-0221/10/01/c01032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Heanue JA, Pearson DA, and Melen RE, "CdZnTe detector array for a scanning-beam digital x-ray system," SPIE Medical Imaging '99, vol. 3659, pp. 718–725, 1999. [Online]. Available: 10.1117/12.349551. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Ishitsu T, Takahashi I, and Yokoi K, "Radiation Imaging Apparatus, Radiation Counting Apparatus, and Radiation Imaging Method," U.S.A. Patent 10,292,669 B2 2019.

- [30].Steadman RB and Roessl E, "Photon Counting Device and Method," U.S.A. Patent 10,365,380 B2 2019.

- [31].Fredenberg E, Lundqvist M, Cederström B, Åslund M, and Danielsson M, "Energy resolution of a photon-counting silicon strip detector," Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment, vol. 613, no. 1, pp. 156–162, 2010, doi: 10.1016/j.nima.2009.10.152. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Hsieh SS, "Coincidence counting for charge sharing compensation," presented at the Workshop on Medical Applications of Spectroscopic X-ray Detectors, Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- [33].Hsieh SS, "Coincidence counting for charge sharing compensation in spectroscopic photon counting detectors," IEEE Transaction on Medical Imaging, vol. 39, no. 3, pp. 678–687, 2020, doi: 10.1109/TMI.2019.2933986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Taguchi K, "Multi-energy inter-pixel coincidence counters for charge sharing in photon counting detectors," Medical Physics, vol. 47, pp. 2085–2098, 2020, doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/mp.14047https://aapm.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/mp.14047http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/mp.14047https://aapm.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/mp.14047 http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/mp.14047 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Lee O, Kappler S, Polster C, and Taguchi K, "Estimation of Basis Line-Integrals in a Spectral Distortion-Modeled Photon Counting Detector Using Low-Order Polynomial Approximation of X-ray Transmittance," (in eng), IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging, vol. 36, no. 2, pp. 560–573, October 26 2017, doi: 10.1109/tmi.2016.2621821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Lee O, Kappler S, Polster C, and Taguchi K, "Estimation of Basis Line-Integrals in a Spectral Distortion-Modeled Photon Counting Detector Using Low-Rank Approximation-Based X-Ray Transmittance Modeling: K-Edge Imaging Application," (in eng), IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging, vol. 36, no. 11, pp. 2389–2403, August 29 2017, doi: 10.1109/TMI.2017.2746269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Taguchi K, "Multi-energy inter-pixel coincidence counters (MEICC) for charge sharing correction and compensation for photon counting detectors: Assessment at a normalized spatial resolution," SPIE Medical Imaging 2020: Physics of Medical Imaging, vol. 11312, pp. 11312–12, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- [38].Taguchi K, Stierstorfer K, Polster C, Lee O, and Kappler S, "Spatio-energetic cross-talk in photon counting detectors: N × N binning and sub-pixel masking," Medical Physics, vol. 45, no. 11, pp. 4822–4843, 2018, doi: : 10.1002/mp.13146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Stierstorfer K, "Modeling the frequency-dependent detective quantum efficiency of photon-counting x-ray detectors," Medical Physics, vol. 45, no. 1, pp. 156–166, 2018, doi: 10.1002/mp.12667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Hsieh SS and Pelc NJ, "A dynamic attenuator improves spectral imaging with energy-discriminating, photon counting detectors," (in eng), IEEE Trans Med Imaging, vol. 34, no. 3, pp. 729–39, March 2015, doi: 10.1109/tmi.2014.2360381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Hsieh SS and Pelc NJ, "Improving pulse detection in multibin photon-counting detectors," (in eng), Journal of medical imaging (Bellingham, Wash.), vol. 3, no. 2, p. 023505, April 2016, doi: 10.1117/1.jmi.3.2.023505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Zheng Y et al. , "Robustness of optimal energy thresholds in photon-counting spectral CT," Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment, vol. 953, p. 163132, 2020/02/11/ 2020, doi: 10.1016/j.nima.2019.163132. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Rajbhandary PL, Persson M, and Pelc NJ, "Detective efficiency of photon counting detectors with spectral degradation and crosstalk," (in eng), Med Phys, vol. 47, no. 1, pp. 27–36, January 2020, doi: 10.1002/mp.13889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]