Background

Currently, the world has found itself in a global pandemic with coronavirus. At its start, to limit the spread of this virus, countries, states, and counties have implemented stay-at-home orders and shutdowns. These shutdowns had great impacts on people's well-being and exacerbated social determinants of health. This project aims to identify patient social determinants of health and their associations during the COVID-19 pandemic via telemedicine.

Methods

A total of 104 patients were surveyed within Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, who had not been seen for at least 4 weeks before March 23, 2020 and who did not have a scheduled visit within 4 weeks of the initial survey. Based on a patient's specific response, resources were then allocated to them.

Results

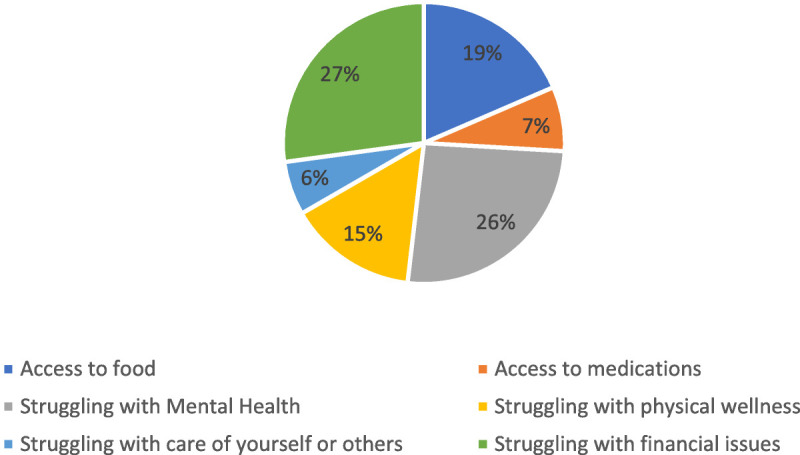

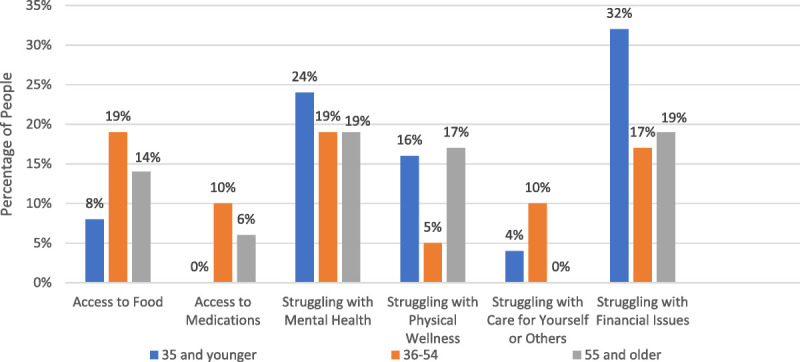

Most patients surveyed identified at least 1 social determinant of health, the most common being financial issues (27%), mental health issues (26%), and access to food (19%). A statistically significant relationship was found between patients who identified finances with access to food, access to medication with struggling to care for themselves or others, and physical wellness with mental health. Lastly, an association was found between those who did not identify any difficulties and wanting more information.

Conclusions

By identifying needed barriers via telemedicine, we can properly allocate resources to those who need it the most and hope to decrease the potential long-term effects of this current pandemic.

Key Words: social determinants of health, COVID-19, quality improvement, public outreach

Across the world, countries, states, and counties closed businesses and enforced social distancing for varying periods as a result of the current COVID-19 pandemic. Allegheny County, the second most populace county in Pennsylvania, had an original stay-at-home order issued by the governor beginning March 23, 2020.1,2 The shutdown that ensued included schools, large gatherings, and nonessential retail stores; essential businesses began limiting occupancy, and hours, while enforcing changes in protocol, such as distancing and wearing masks. Although the county, along with the country, braced for the repercussions of the virus, such as increased hospitalizations, some of the subtler consequences were initially overlooked. These included a spike in unemployment, resulting in financial uncertainty, and the need to distance from loved ones.3 The dramatic effects quarantine can have has been acknowledged in Lancet, which reported that “separation from loved ones, the loss of freedom, uncertainty over disease status, and boredom can, on occasion, create dramatic effects…suicide has been reported.”4

As we navigated the new and changing medical and economic environments, we recognized the potentially profound effects quarantine may have on our patient population. There is minimal literature regarding identifying social determinants of health and allocating resources during a pandemic. Furthermore, after identifying these barriers, we aim to analyze possible associations among them and provide patients with resources to help overcome their specific identified barriers.

METHODS

Internal medicine residents at Allegheny General Hospital located in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, created a telephone survey, which was determined to be a quality improvement project and approved by the Allegheny Singer Research Institute Institutional Review Board. Primary care physicians within an intercity population created a survey to be administered telephonically to patients. This project was determined to be a quality improvement project and approved by a research institute institutional review board. The primary outpatient clinical site serves a vulnerable patient population with a significant need for social services. This survey reviewed the common nonmedical obstacles during the COVID-19 pandemic (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Telephone Survey Used When Calling Patients

| Question | Yes | No |

|---|---|---|

| Are you aware of the current coronavirus pandemic? | ||

| Are you interested in additional assistance with identified needs during the current pandemic? | ||

| Access to food | ||

| Access to prescription medications | ||

| Struggling with mental health | ||

| Struggling with physical wellness, such as exercise | ||

| Struggling with care for yourself or others, such as access to childcare, access to home care | ||

| Struggling with financial assistance | ||

| Other: ______________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ |

NA | NA |

| I am not experiencing any additional difficulty as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic: ___ | NA | NA |

| Would you like more information and education about the coronavirus pandemic? |

The identified needs were based on social determinants such as access to food, financial assistance, and mental health care. Residents identified patients within their assigned primary care panels who had not been seen for at least 4 weeks before March 23, 2020 and who did not have a scheduled visit within 4 weeks of the initial survey. A combination of residents and medical assistants then contacted patients using secure phone lines.

Upon agreement to participate in this survey, patients were asked a series of questions illustrated in Table 1, including knowledge of the pandemic and a screening for the social determinants of health. Patients were able to identify more than one barrier if applicable.

Once the survey was complete, patients were helped based on identified barriers. Patients received specific information around food banks and distribution centers, medication delivery services, work out regimens and available day care centers. Specifically, if patients were struggling with mental health issues, the behavioral consultant in the clinic aided the medical team in providing the patient with necessary resources and services. Lastly, patients experiencing financial issues were given information around aid, resources, and access to a social worker.

RESULTS

A total of 104 patients were contacted and were agreeable to participate in the survey. One hundred percent of the patients were aware of the pandemic. The mean age of the patients was 48 years, with the majority being Black (52.9%) or White (42.3%). A total of 44 males and 60 females were surveyed. The most commonly identified areas of concern were financial issues (27%), mental health issues (26%), and access to food (19%) (Fig. 1). It is noteworthy that each social determinant of health was identified at least once for the age group of 36 to 54 (Fig. 2). This was not true in any other age category.

FIGURE 1.

Percentage of each social determinant of health out of total identified.

FIGURE 2.

Percentage of people who identified a social determinant of health within each age group.

Overall, for those who identified finances as a barrier, there was a statistically significant correlation with difficulty with access to food [analysis of variance (ANOVA) test, P = 0.009]. In patients who identified physical wellness as a barrier, there was a statistically significant correlation with concurrent mental health struggle (ANOVA test, P = 0.026). For those who identified difficulty with access to medication, there was a statistically significant relationship with struggling to care for themselves or others (ANOVA test, P = 0.035). Lastly, those who did not identify any difficulties during this time were found to answer “yes” in wanting more information and education about the pandemic with statistical significance (ANOVA test, P = 0.002).

DISCUSSION

Our data have indicated that most patients contacted were experiencing at least 1 barrier due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, we found that half of the barriers were associated with another barrier with statistical significance. Surprisingly, those who stated they were not experiencing any difficulties wanted more information about the pandemic, suggesting possible need for resources. Recognizing the significance of these relationships is necessary to assist patients adequately.

This study is limited by sample size; however, it was performed in the early weeks of the pandemic when the first stay-at-home order was initiated. In addition, the population studied has a significant need for social services before the pandemic. This may limit applicability of study to all populations. However, as the pandemic continues, and second waves occur throughout the United States, small pockets of vulnerable populations are forced to have more strict social distancing policies, and therefore, we believe this study continues to be applicable.

Given the survey responses, we would advocate for primary care offices to reach out to patients who have not recently been seen in the office, or do not have an upcoming visit, to assess social determinants of health and disparities. Furthermore, given the aforementioned correlations providing patients with additional resources based on coinciding needs may be valuable. In recognizing that financial difficulty is associated with access to food, it would be prudent to provide those with identified financial instability with resources for assistance and access to social work as well as information about local food banks. For patients grappling with mental health concerns, it may be of benefit to provide them with resources to concurrently improve their physical well-being. Finally, for patients who may have difficulty obtaining their medication, resources for care should be included. Notably, telephone outreach is not only applicable to those struggling with social determinants of health, as those with no identified barriers desired additional information about the pandemic. This finding suggests that our results should be applied broadly, not just in vulnerable populations.

As telemedicine has become increasingly prominent and used during the pandemic, a survey to assist patients is ideal for this updated provision of care. It is our hope that providing patients with information and addressing their barriers with targeted interventions may prevent adverse events during this public health crisis.

CONCLUSIONS

As physicians, our duty to serve patients not only encompasses medical issues but also social determinants that can affect population health. By identifying barriers to social determinants of health, we can properly allocate resources to those who need it the most and hope to decrease the potential long-term effects of this current pandemic.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

All surveys performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee.

Footnotes

The authors have no funding or conflicts of interest to disclose.

Contributor Information

Nikos Pappan, Email: Nikospappan@gmail.com.

Scarlett Austin, Email: Scarlett.austin@ahn.org.

Divya Venkat, Email: Divya.venkat@ahn.org.

Payal Thakkar, Email: payalp1@yahoo.com.

REFERENCES

- 1.Governor Wolf and health secretary issue ‘stay at home’ orders to 7 counties to mitigate spread of COVID-19 [Internet]; 2020. Available at: https://www.governor.pa.gov/newsroom/governor-wolf-and-health-secretary-issue-stay-at-home-orders-to-7-counties-to-mitigate-spread-of-covid-19/. Accessed July 30, 2020.

- 2.Templeton D. Allegheny, most southwest counties moving to green phase of reopening June 5 [Internet]. In: Gazette. Pittsburgh Post-Gazette; 2020. Available at: https://www.post-gazette.com/local/westmoreland/2020/05/29/green-phase-western-pennsylvania-reopening-westmoreland-butler-June-5/stories/202005290094. Accessed July 30, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 3.The employment situation—Bureau of Labor Statistics [Internet]. BLS.gov. 2020. Available at: https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/empsit.pdf. Accessed July 30, 2020.

- 4.Brooks SK Webster RK Smith LE, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395:912–920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]