Abstract

In school, shyness is associated with psychosocial difficulties and has negative impacts on children’s academic performance and wellbeing. Even though there are different strategies and interventions to help children deal with shyness, there is currently no comprehensive systematic review of available interventions. This systematic review and meta-analysis aim to identify interventions for shy children and to evaluate the effectiveness in reducing psychosocial difficulties and other impacts. The methodology and reporting were guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement and checklist. A total of 4,864 studies were identified and 25 of these met the inclusion criteria. These studies employed interventions that were directed at school-aged children between six and twelve years of age and described both pre- and post-intervention measurement in target populations of at least five children. Most studies included an intervention undertaken in a school setting. The meta-analysis revealed interventions showing a large effect in reducing negative consequences of shyness, which is consistent with extant literature regarding shyness in school, suggesting school-age as an ideal developmental stage to target shyness. None of the interventions were delivered in a classroom setting, limiting the ability to make comparisons between in-class interventions and those delivered outside the classroom, but highlighting the effectiveness of interventions outside the classroom. The interventions were often conducted in group sessions, based at the school, and involved activities such as play, modelling and reinforcement and clinical methods such as social skills training, psychoeducation, and exposure. Traditionally, such methods have been confined to a clinic setting. The results of the current study show that, when such methods are used in a school-based setting and involve peers, the results can be effective in reducing negative effects of shyness. This is consistent with recommendations that interventions be age-appropriate, consider social development and utilise wide, school-based programs that address all students.

Introduction

Shyness is commonly experienced by school-aged children [1]. Despite being a frequently used term, there is a diversity of constructs that underpin ‘shyness’, including behavioural inhibition, social reticence, social withdrawal, anxious solitude and social anxiety [2]. There have been several approaches to defining shyness in the past. Some conceptualisations theorise shyness as either behavioural inhibition to the unfamiliar (i.e., wariness in unfamiliar situations) or social withdrawal [i.e., elevated rates of solitary behaviour or symptoms of social anxiety disorder; 3–7]. In contrast, substantial literature has investigated shyness as encompassing individual differences in wariness or anxiety in novel situations, embarrassment or self-conscious in anticipation of social evaluation and reticence in social situations [7]. Shyness has also been considered from a developmental perspective, proposing an interactional child-by-environment model. By this model, behavioural inhibition and social withdrawal are considered risk factors for further social anxiety. Interactions between the child and the environment, and the child and their parents and peers, can either promote or diminish the risk of later anxiety [4,8,9].

Taxonomy of shyness

In order to organise and operationalise the various concepts of shyness in use, Rubin, Coplan [7] proposed a taxonomy of shyness. This taxonomy places behavioural solitude (i.e., lack of interaction in presence of peers) as the over-arching, observable behaviour of shyness. The source of this solitude is either internal, termed social withdrawal (i.e., removing oneself from social interaction) or external, termed active isolation (i.e., being excluded by others). If the source is internal (i.e., social withdrawal), the motivation for withdrawal is either by preference, termed social disinterest, or a result of fear or wariness. The source of fear is then split into four categories: 1) behaviour inhibition (i.e., fear of novelty); 2) anxious solitude (i.e., wariness in familiar social situations); 3) shyness (i.e., wariness of social novelty and/or perceive evaluation); and 4) social reticence (i.e., observed display of onlooker behaviours). In this taxonomy, these fears and behaviours can become clinically significant over time and manifest as a social anxiety disorder. This taxonomy provides a clear conceptualisation of shyness and social anxiety, and outlines observable behaviours, sources, motivations and specific fears.

Shy children in school

In addition to the potential manifestation of social anxiety disorder theorised by Rubin, Coplan [7], children with shyness may also experience a range of other difficulties that, although not clinically diagnosable, can vastly impact their wellbeing, social networks and academic performance [10]. Many of these difficulties are experienced at school, where peer interactions are an integral component of the environment. Shy children are often quiet across a range of situations in school, both in the classroom and in social situations [11]. Talking, in or outside of class, can make a child the centre of attention and open to social evaluation, which sits at the centre of the taxonomy of shyness. Shy children have fewer in-class interactions and respond less often to direct or class-wide questions than their non-shy peers [12]. Research has shown that shy children often have lower academic attainment, poorer performance on tests of language development, and are more likely to have difficulty adjusting at school [10].

Shyness is also associated with psychosocial challenges in school. Shy children often have a limited number of friends and are at risk of peer victimisation and exclusion [7,13]. They may also use social withdrawal as a way to avoid or cope with peer victimisation [14]. Shyness is positively associated with somatic complaints, school-related stress, anxiety and depressive symptoms [15,16]. Shyness can increase over time, predicting difficulties later in adolescence [17]. Shy children often have poor social skills and high levels of anxiety and depression symptoms in early adolescence [17]. Longitudinal studies show that shyness and social withdrawal are significant risk factors for social anxiety disorder [8,18]. These results are aligned with the Rubin, Coplan [7] taxonomy of shyness and social anxiety, demonstrating the theorised pathway to social anxiety disorder.

School-based interventions for shy children

Given the short- and long-term psychosocial and academic outcomes for shy children, there have been multiple attempts at buffering the impacts of shyness. In the classroom, teachers can use concepts, such as shyness, as a tool to tailor how they work with an individual child [19]. Teachers at a Norwegian elementary school broadly categorised shy children in their classroom as either, 1) withdrawn, 2) anxious, and/or 3) having poor self-esteem. These categories then informed the support given to the individual child, including cognitive support and feedback and encouraging active learning [19]. Informal, teacher-facilitated support or intervention is a common response to shyness within the classroom, as teachers recognise shy children and the potential problems they encounter [20–22]. Teachers report employing social learning strategies, such as verbal encouragement, praise and modelling behaviour, as well as peer-focused strategies to promote inclusion, such as encouraging joint activities [20]. However, the effectiveness of these individual attempts is limited to within the classroom and may not impact poor psychosocial outcomes for shy children in broader contexts.

Beyond classroom support, there are many different structured interventions targeting shyness in school-aged children. Clinical interventions are typically conducted in non-naturalistic settings with homework-style practice in naturalistic settings, and comprise of social skills training, psychoeducation, cognitive restructuring and exposure tasks [8]. Criticisms of this approach are that such interventions do not consider nor change the environment itself and focus on treating social anxiety disorders, ignoring shyness more broadly [8]. Clinical interventions need to be age-appropriate and consider cognitive and social development, social context and parent involvement [23]. As shy children are often excluded or victimised by their peers, interventions need to consider the environment and peer interaction. Developmental interventions include peers in the intervention itself, aiming to increase the use of successful social skills in naturalistic settings [8]. However, this approach requires school resources and willingness of peers to be involved. Crozier [1] suggests that a focus on individual screening and pathologising shyness may not lead to effective intervention, as not all shy children develop anxiety disorders. Wider, school-based programs that address all student’s social confidence, instead of targeted interventions, may be more suitable intervention for shyness [1]. Given the wide range of intervention approaches and intervention programs themselves, there is no clear best-practice for interventions for shy children. This is further complicated by inconsistent use of terminology related to shyness [1].

To reduce academic and concomitant psychosocial difficulties in school for shy children, there is a need for effective, feasible interventions. To date, there is no comprehensive systematic review of the available interventions for shy children. This systematic review and meta-analysis aim to provide an overview of the available interventions for shy children aged six to twelve years, describe the characteristics of the interventions, summarise intervention strategies being used, and determine their overall effectiveness, as well as effectiveness of interventions in relation to the following domains: 1) setting where the interventions is delivered; 2) mode of delivery; 3) intervention focus; and 4) rater of outcome measures.

Method

The methodology and reporting on this systematic review were guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement and checklist. The PRISMA statement and checklist supports researchers in the critical and transparent reporting of systematic reviews in areas of health care [24,25].

[The PRISMA checklist is provided as Supporting Information].

Eligibility criteria

To be eligible for inclusion in this systematic review, studies were required to describe an intervention in school-aged children (between six and twelve years old) for social anxiety and shyness. Only studies describing both pre- and post-intervention measurement in target populations of at least five children were included. Only original articles published in English were considered for eligibility. Conference abstracts, case reports, reviews, student dissertations and editorials were excluded.

Data sources and search strategies

Literature searches were conducted in five electronic databases: CINAHL, Embase, Eric, PsycINFO and PubMed. All publication dates up to 23rd December 2020 were included. The search strategies per database are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Search strategies per literature database.

| Database and search terms (subject headings and free text words) |

|---|

| CINAHL: ((MH "Shyness") OR (MH "Social Isolation") OR (MH "Social Isolation (Saba CCC)") OR (MH "Impaired Social Interaction (NANDA)") OR (MH "Social Isolation (NANDA)")) AND ((MH "Clinical Effectiveness") OR (MH "Treatment Outcomes") OR (MH "Effect Size") OR (MH "Outcome Assessment") OR (MH "Outcomes (Health Care)+") OR (MH "Intervention Trials") OR (MH "Program Evaluation") OR (MH "Evaluation+") OR (MH "Course Evaluation") OR (MH "Evaluation Research+")) |

| Embase: (shyness/ OR introversion/ OR psychosocial withdrawal/ OR loneliness/ OR social isolation/ OR internalization/) AND (treatment outcome/ OR measurement/ OR intervention study/ OR program evaluation/ OR program effectiveness/ OR program efficacy/ OR evaluation research/ OR evaluation study/ OR course evaluation/) |

| Eric: (shyness/ OR extraversion introversion/ OR "withdrawal (psychology)"/ OR Social isolation/) AND (effect size/ OR efficiency/ OR outcome measures/ OR treatment duration/ OR treatment outcome/ OR treatment response/ OR measurement/ OR intervention/ OR program administration/ OR program effectiveness/ OR program evaluation/ OR evaluation/ OR evaluation research/ OR course evaluation/ OR courses/ OR "outcomes of treatment"/ OR efficiency/) |

| PsycINFO: (timidity/ OR introversion/ OR social anxiety/ OR "inhibition (personality)"/ OR loneliness/ OR social isolation/ OR timidity/ OR approach avoidance/ OR internalization/) AND ("effect size (statistical)"/ OR Efficiency OR intervention/ OR program evaluation/ OR treatment/ OR evaluation/ OR course evaluation/) |

| PubMed: ("Shyness"[Mesh] OR "Introversion (Psychology)"[Mesh] OR "Inhibition (Psychology)"[Mesh] OR "Loneliness"[Mesh] OR "Social Isolation"[Mesh] OR "Social Communication Disorder"[Mesh] OR "Adjustment Disorders"[Mesh] OR "Emotional Adjustment"[Mesh]) AND ("Treatment Outcome"[Mesh] OR "Program Evaluation"[Mesh] OR "Outcome Assessment (Health Care)"[Mesh] OR "Outcome and Process Assessment (Health Care)"[Mesh] OR "Patient Outcome Assessment"[Mesh] OR "Self-Evaluation Programs"[Mesh] OR "Efficiency"[Mesh]) |

Methodological quality and level of evidence

The Qualsyst critical appraisal tool by Kmet [26] and the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Evidence Hierarchy Levels of Evidence [27] were used to assess the methodological quality of the included studies: I (systematic review of level II studies); II (randomised controlled trial); III-1 (pseudo-randomised controlled trial); III-2 (comparative study with concurrent controls); III-3 (comparative study without concurrent controls); IV (case series with either post-test or pre-post outcomes). The Qualsyst tool provides a systematic, reproducible and quantitative means of appraising the methodological quality of research across a broad range of study designs. The Qualsyst consists of 14 items. All items have a three-point ordinal scoring (yes = 2, partial = 1, no = 0). A total score can be converted into a percentage score. A score above 80% is considered strong quality, a score of 60 to 79% considered good, a score of 50 to 59% considered adequate, and a score below 50% considered poor quality. Studies with poor study quality were excluded from further analysis in this review.

Data extraction

A data extraction form was created to extract data from the included studies under the following categories: study design (according to NHMRC level), methodological quality (Qualsyst), participants (numbers, groups), age (range, mean, standard deviation), gender, intervention, inclusion criteria of the individual study (if stated), outcome measures and treatment outcomes. To ensure the meta-analysis focused on factors that impact on shyness, authors identified and extracted only data collected using the main outcome measure related to shyness (see Table 2). Due to the lack of dedicated shyness outcome measures in literature, the most suitable outcome measure related to shyness was chosen. Data including means, standard deviations, and sample sizes were extracted from the included studies to enable the calculation of the overall effect of shyness interventions (within-group pre-post intervention comparisons), and comparisons between shy children and control groups (between-group experimental vs. control intervention group comparisons).

Table 2. Characteristics of included studies.

| Treatment/Target skills | Reference/Location | Study Design1 and Quality2 | Participant groups | Inclusion/Exclusion/Shyness Definition | Shyness Outcome Measure | Treatment Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Social Effectiveness Training for Children (SET-C) Social skills, anxiety, fear, interpersonal functioning, participation in social activities |

Beidel, Turner [30],USA |

Design III-1 |

Total sample: N = 50 Age: Not reported Gender: Not reported Diagnosis (N): social phobia (50), panic disorder (1), generalised anxiety (5), specific phobia (3), OCD (2), separation anxiety (4), adjustment disorder (1), selective mutism (4), ADHD (8)20 |

Inclusion: Primary diagnosis of social phobia and/or social fears at a subclinical level |

Self-report ● Eysenck Personal Inventory ● SPAI-C+ ● STAI-C ● Loneliness Scale ● Daily Diary of stressful events |

Significant effect on extroversion, total social anxiety and phobia scores, K-GAS severity, ADIS-C severity, loneliness, state and trait anxiety, neuroticism, internalising behaviours and play skills for treatment group (p < .05) |

|

Quality Strong 88% (21/24) |

Intervention:

N = 30 Age: 10.5 ± 1.6 Gender: 47% M, 53% F Diagnosis: Not reported |

Exclusion: None reported |

Parent report ● CBCL |

67% of treatment group no longer met diagnostic criteria for social phobia | ||

|

Control:

N = 20 Age:10.6±1.4 Gender: 30% M, 70% F Diagnosis: Not reported |

Definition: Social phobias, fears of interpersonal interactions and public performances |

Teacher report NA Clinician rating ● K-GAS ● ADIS-C |

Non-significant tread for read-aloud effectiveness (p < .07) | |||

|

Observations ● Behavioural assessment during role-play |

Improvements maintained at 6-month follow up | |||||

| Beidel, Turner [31], USA |

NHMRC Level III-1 |

Total sample:

N = 122 Age: 11.61±2.6 Gender: 53.3% M, 46.7% F Diagnosis (%): Social phobia (100), generalised anxiety (31), specific phobia (14), separation anxiety (11), dysthymic disorder (4.1), selective mutism (10), ADHD (12), language/reading disorder (0.8), learning disorder NOS (0.8) |

Inclusion: ages 7 to 17, primary diagnosis of social phobia |

Self-report ● MASC ● SPAI-C+ ● Loneliness Scale ● Daily Diary of stressful |

53% of treatment group no longer met diagnostic criteria (p < .001) |

|

|

Quality Strong 88% (21/24) |

Intervention:

N = 57 Age: Not reported Gender: Not reported Diagnosis: Not reported |

Exclusion: Co-existing disorder with higher severity rating than primary, co-morbid bipolar disorder, psychosis, conduct disorder, autism spectrum disorders and intellectual disability; active suicidal ideation; previous unsuccessful trial of fluoxetine or behaviour therapy |

Parent report ● CBCL |

Significant reduction in severity of social phobia between treatment and placebo (p < .05); non-sig between treatment and placebo Significant reduction in behavioural avoidance for treatment group (p < .05) |

||

|

Fluoxetine:

N = 33 Age: Not reported Gender: Not reported Diagnosis: Not reported |

Definition: Social phobias, fears of interpersonal interactions and public performances |

Teacher report NA |

Significant improvement in social skills and anxiety Non-significant difference in observer rating of anxiety (p < .05) |

|||

|

Placebo:

N = 32 Age: Not reported Gender: Not reported Diagnosis: Not reported |

Clinician rating ● K-GAS ● CGI ● ADIS-C |

All treatment gains maintained at 12-month follow-up | ||||

| Observations-Behavioural assessment during role-play | ||||||

|

Problem-solving and conversational skills training Recognising a problem, defining a problem, generating solutions, evaluating consequences, determining best solution, implementing a solution, listening, talking about oneself, initiating conversations, making requests of others |

Christoff, Scott [32], USA |

NHMRC Level III-3 |

Total sample:

N = 6 Age: 12.8, 12–14 Gender: 2 M, 4 F Diagnosis: Typically developing |

Inclusion: Recommendation by school staff; appear to lack skills for effectively socialising with peers, few friends, did not attend extracurricular events, appeared to be “loners” |

Self-report ● Conversation diary of preceding 24 hr period ● Self-Esteem Scale ● Social Interaction Survey ● Self rating of academic performance, ability to get along with others, number of friends, ability to converse, comfort talking to others, number of extracurriculars |

Problem-solving effectiveness increased above baseline levels, immediately after introduction of problem-solving training |

|

Quality Good 77% (17/22) |

Exclusion: None reported |

Conversation skills increase on first two baseline assessments; then decreased on third and fourth baseline assessments | ||||

| Definition: Not reported |

Parent report ● Subject rating of academic performance, ability to get along with others, number of friends, ability to converse, comfort talking to others, number of extracurriculars |

Introduction of problem-solving training lead to increase to specific conversational skills, above baseline levels | ||||

| Introduction of conversational skills training led to increases in conversational skills, effective behaviour and overall conversational qualit | ||||||

|

Teacher report ● Subject rating of academic performance, ability to get along with others, number of friends, ability to converse, comfort talking to others, number of extracurriculars |

Quality ratings and number of appropriate statements increased over time | |||||

| Question-asking skills showed less change over time | ||||||

|

Clinician ratings ● Problem-solving effectiveness, based on means-end problem-solving ● audio of peer-peer conversations (specific skills, effective behaviour, overall quality) ● Cafeteria observations+ |

Significant interaction between interaction frequency and higher self-esteem | |||||

|

Observations NA |

Significant increase in social interaction scores | |||||

| Significant increase in mean ratings of social adjustment, conversational ability and extracurriculars | ||||||

|

Turtle Program Social skill, introducing self, eye contact, communication, relaxation, expressing emotions, working together, exposure to fear |

Chronis-Tuscano, Rubin [33], USA |

NHMRC Level III-2 |

Total Sample:

N = 41 Age: Not reported Gender: Not reported Diagnosis: Not reported |

Inclusion: 42 to 60 months, Behavioural Inhibition Questionnaire > 132 |

Self report NA |

Significant Time x Group interactions for anxiety symptoms, favouring treatment group |

|

Quality Strong 93% (26/28) |

Treatment:

N = 18 Age: 50.81± 9.37 months Gender: 50% M, 50% F Diagnosis (%): Social phobia (72), any anxiety disorder (77.8), selective mutism (11.1), specific phobia (5.5), separation anxiety (16.7), major depressive disorder (11.1), ADHD (5.5), ODD (5.5) |

Exclusion: Social Communication Questionnaire score > 15 |

Parent report ● Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment + ● BIQ ● CBCL ● PAS; Total and social anxiety scales |

Treatment effects on social anxiety marginally significant, medium effect size | ||

|

Waitlist:

N = 22 Age: 54.27 ± 10.19 Gender: 36% M, 64% F Diagnosis (%): social phobia (45), any anxiety disorder (45), specific phobia (4.5), separation anxiety (4.5), major depressive disorder (4.5) |

Definition: behavioural inhibition, social reticent behaviours |

Teacher report ● SAS; Total and social anxiety scales |

Significant Time x Group interactions on BIQ, CBCL Internalising scale, PAS social anxiety scale, greater improvements in treatment group | |||

|

Clinician rating NA |

Teachers reported significant reductions for treatment group in total and generalised anxiety with medium to large effect size, compared to waitlist | |||||

|

Observations ● Positive Affect/Sensitivity and Negative Control of parent during free play with child |

Significant Time x Group interaction on maternal Affect/Sensitivity during free play, greater improvement in treatment group with medium effect size | |||||

| No treatment effects on maternal Negative Control | ||||||

|

The Courage and Confidence Mentor Program Internalising problems |

Cook, Xie (30), USA |

NHMRC Level IV |

Total sample:

N = 5 Age: 6th to 8th grade (11–14 years) Gender: 3 M, 2 F Diagnosis: Typically developing |

Inclusion: SIBS score > 8, < 15; SUD ratings > 6 across two consecutive days |

Self report ● SUD ● CIRP |

Teachers reported intervention to be reasonable, acceptable and effective Students found intervention acceptable on CIRP |

|

Quality Strong 82% (18/22) |

Exclusion: None reported |

Parent report NA |

SUD ratings of all participants decreased from baseline (M = 7.3) to end of intervention (M = 3.3). | |||

| Definition: Internalising problems |

Teacher report ● SIBS ● TRF; Internalising Scale+ ● Intervention Rating Profile |

|||||

|

Clinician rating NA |

||||||

|

Observations NA |

||||||

|

Play Skills for Shy Children Social skills, initiating and maintaining interactions, expressing and understand emotions, relaxation techniques |

Coplan, Schneider [35], Canada |

NHMRC Level II |

Total sample:

N = 22 Age: 56.25±5.99 months Gender: 11 M, 11 F Diagnosis: Typically developing |

Inclusion: between 48 and 60 months of age, parent-rating BIQ scores above top 15% cut-off, SDQ scores below borderline range for conduct and hyperactivity-inattention, child and one parent willing to participant |

Self report NA |

Children in intervention group displayed significantly less reticent-wary behaviours during free-play, compared to waitlist |

|

Quality Strong 86% (24/28) |

Intervention:

N = 11 Age: Not reported Gender: 7 M, 4 F Diagnosis: Typically developing |

Exclusion: None reported |

Parent report ● BIQ ● SDQ |

Children in intervention group displayed significantly more socially competent behaviours during free-play, compared to waitlist | ||

|

Waitlist Control:

N = 11 Age: Not reported Gender: 4 M, 7 F Diagnosis: Typically developing |

Definition: behavioural inhibition, wary and reticent behaviours during novel settings with unfamiliar adults or peers |

Teacher report ● CBS |

No significant effect of teacher-rated anxious behaviours or prosocial behaviours |

|||

|

Clinician rating NA |

||||||

|

Observations ● Behaviours during free-play+ |

||||||

| Emotion regulation and awareness, psychosomatic complaints | Fiat, Cook [34], USA |

NHMRC Level III-2 |

Total sample:

N = 6 Age: 8.9, 7–10 years Gender: 3 M, 3 F Diagnosis (%): Specific learning disability (33) |

Inclusion: SIBS score > 8, < 15; SUD ratings > 6 across two consecutive days |

Self report ● SUD ● CIRP |

All but one participant showed reduction in subjective distress |

|

Quality Strong 86% (19/22) |

Exclusion: None reported |

Parent report NA |

Mean changes observed across SIBS, SUD and TRF measures | |||

|

Definition: Internalising problems, withdrawal behaviours |

Teacher report ● Direct behaviour Rating Single-Item Scale ● SIBS ● TRF; Internalising Scale+ |

Three participants no longer met established risk score |

||||

|

Clinician rating NA |

Evidence of functional relationship between intervention and internalising behaviours for all participants | |||||

|

Observations NA |

Increase in participation ratings for all participants | |||||

|

Resilient Peer Treatment Positive play skills, routine |

Fantuzzo, Manz [36], USA |

NHMRC Level III-1 |

Total Sample:

N = 82 Age: 4.35 ± 0.47 Gender: 50% M, 50% F Diagnosis: Not reported |

Inclusion: most socially withdrawn children across classrooms |

Self report NA |

Significant main effect for treatment for children in intervention group for collaborative play |

|

Quality Strong 93% (26/28) |

Intervention:

N = 38 Age: Not reported Gender: Not reported Diagnosis: Not reported |

Exclusion: None reported |

Parent report NA |

Significant main effect for treatment for intervention group for solitary play; intervention group showed less solitary play | ||

|

Control:

N = 44 Age: Not reported Gender: Not reported Diagnosis: Not reported |

Definition: socially withdrawn |

Teacher report ● Penn Interactive Peer Play Scale ● Social Skills Rating System |

No significant effects for associative or social attention play | |||

|

Clinician rating NA |

Higher levels of interaction play for intervention group compared to control | |||||

|

Observations ● Interactive Peer Pay Observational Coding System+ |

Intervention group rated significantly higher than control on play interaction and significantly lower on play disruption teacher rating scales | |||||

| Intervention group rated significantly higher than control on self-control and interpersonal skills on teacher rating scales | ||||||

| Intervention group displayed lower levels of internalising, externalising and behaviour problems than control | ||||||

|

Social Effectiveness Therapy for Adolescents- Spanish version (SET-Asv) Social skills, anxiety, fear, interpersonal functioning, participation in social activities |

Garcia-Lopez, Olivares [37], Not reported |

NHMRC Level III-2 |

Total Sample:

N = 25 Age: 20.83±0.79 Gender: 7M, 17 F Diagnosis (%): social phobia (100), avoidant personality (N.R.), selective mutism (10) |

Inclusion: Generalised social anxiety |

Self report ● SPAI; Social Phobia scale and Agoraphobia scale+ ● SAS-A; New Social Situations scale and Generalised Social Inhibition scale |

Improvement between pre and post-test, maintained at 1and 5-year follow-up |

|

Cognitive-Behavioural Group Therapy for Adolescents (CBGT-A) Social skills, problem-solving, cognitive restructuring |

Quality Strong 82% (18/22) |

CBGT-A:

N = 8 Age: Not reported Gender: Not reported Diagnosis (%): social phobia (100) |

Exclusion: None reported |

Parent report NA |

Social anxiety symptoms evident at 5-year follow-up, despite improvements | |

|

Therapy for Adolescents with Generalised Social Phobia (IAFS) Social skills, public speaking, initiate/maintain conversations |

SET-Asv: N = 7 Age: Not reported Gender: Not reported Diagnosis (%): social phobia (100) |

Definition: Social phobia, social anxiety disorder |

Teacher report NA |

At 5-year follow-up, SET-Asv and IAFS groups obtained lowest scores on all anxiety measures | ||

|

IAFS:

N = 8 Age: Not reported Gender: Not reported Diagnosis: social phobia (100) |

Clinician rating ● ADIS-C; Social Phobia Section |

No significant differences between interventions in social anxiety scores at 5-year follow-up | ||||

|

Observations NA |

High effect sizes for all interventions | |||||

| 43% of SET-Asv group no longer met DSM-IV criteria for social phobia at any follow-up period; 29% relapsed at 5-year follow-up | ||||||

| 12.5% of CBGT-A group no longer met DSM-IV criteria for social phobia at any follow-up period; 17.5% relapsed at 5-year follow-up | ||||||

| 25% of IAFS group no longer met DSM-IV criteria for social phobia at any follow-up period; 50% relapsed at 5-year follow-up | ||||||

|

Buddy Bench Social involvement |

Griffin, Caldarella [28], USA |

NHMRC Level III-2 |

Total Sample:

N = 388 Age: Grades 1 to 6 Gender: Not reported Diagnosis: Typically developing |

Inclusion: Any child between Grades 1 to 6 at particular elementary school is Utah, USA |

Self report NA |

Students in 1st to 3rd grade playground extended 130 invitations to students on the bench 76 (58%) were accepted and led to play activities |

|

Quality Strong 86% (19/22) |

Teachers:

N = 21 Age: Not reported Gender: 1 M, 20 F Diagnosis: Typically developing |

Exclusion: Kindergarten children at same school |

Parent report NA |

Average 1.03 students using the bench at any given time | ||

| Definition: Solitary behaviour, not being engaged with other students or engaging in behaviour alone with no other students within five feet |

Teacher report ● Treatment fidelity ratings; Reported they had taught students to use buddy bench, school-wide announcements, posted rules in classroom |

Students on 4th to 6th grade playground extended 75 invitations to students using the bench 47 (63%) were accepted and led to play activities |

||||

|

Clinician rating NA |

Average 0.8 students using the bench at any given time | |||||

|

Observations ● Number of students using bench ● Number of play invitations extended to students using bench ● Number of play invitations accepted by students using bench ● Successful teach-directed prompts to use bench ● Number of students engaged in solitary behaviour+ |

24% reduction in solitary behaviour from baseline for 1st to 3rd grade playground, statistically significant | |||||

| 19% reduction in solitary behaviour from baseline for 4th to 6th grade playground, statistically significant | ||||||

| When bench removed, solitary behaviour gradually returned to near baseline (13% increase from intervention phase) | ||||||

| When bench re-introduced, solitary behaviour immediately decreased to near intervention levels (13% decrease) | ||||||

|

The Coping Bear Program Relaxation techniques, cognitive restructuring |

Hum, Manassis [38], Canada |

NHMRC Level III-2 |

Total Sample:

N = 88 Age: Not reported Gender: Not reported Diagnosis: Not reported |

Inclusion for clinical group: rated within clinical range on Child Behaviour Checklist Internalising scale; attended more than 75% of therapy sessions; returned to the lab for post-treatment assessment |

Self report ● MASC ● STAIC-S |

Significant pre-post differences in CBL between comparison, improver and non-improver groups |

|

Quality Strong 95% (21/22) |

Clinical group:

N = 47 Age: Not reported Gender: Not reported Diagnosis: generalised anxiety, social anxiety or separation disorder |

Inclusion for control group: rating within normal range on Child Behaviour Checklist internalising scale |

Parent report ● CBCL; Internalising scale+ |

At post-test, improver and non-improver groups differ significantly in CBL scores | ||

|

Control:

N = 41 Age: Not reported Gender: Not reported Diagnosis: Typically developing |

Exclusion: None reported |

Teacher report NA |

Significant decrease in CBL scores pre-post for improver group | |||

|

Treatment Improvers:

N = 11 Age: 10.58±1.19 Gender: 3M, 8 F Diagnosis (N): GAD (8), GAD and SOC (2), ADHD (2) |

Definition: anxiety disorder, anxiety behaviour |

Clinician rating NA |

At both pre and post-test, comparison group differed from improvers and non-improvers on MASC scores | |||

|

Treatment Non-improvers:

N = 13 Age: 10.46±1.29 Gender: 5 M, 8 F Diagnosis (N): generalised anxiety only (5), SOC only (2), separation anxiety only (1), SOC and separation anxiety (1), generalised anxiety and SOC (2), generalised anxiety and separation anxiety (1), generalised anxiety, SOC and separation anxiety (1) |

Observations NA |

At post-test, comparison group differed significantly from improvers on STAIC-S scores | ||||

|

EEG Task ● Go/No Go tasks; Posterior P1 and frontal N2 components evaluated for correct No-go trials |

No significant differences between groups of Go/NO Go accuracy, response duration, time allotment, Go response times and error No-go response times | |||||

| Greater P1 amplitudes for non-improvers compared to improvers or comparison | ||||||

| Significant increase in N2 amplitude for improvers; decrease for non-improvers | ||||||

|

Cool Kids Program- For Parents Psychoeducation, management strategies, cognitive restructuring, coping |

Kennedy, Rapee [39], Australia |

NHMRC Level III-2 |

Total Sample:

N = 71 Age: 47.07 ± 7.05 months Gender: Not reported Diagnosis (N): social phobia (70), generalised anxiety (1), specific phobia (37), separation anxiety (27), OCD (5), selective mutism (3), ODD (6), ADHD (3) |

Inclusion: High score on laboratory measure of behavioural inhibition, one parent who met criteria for DSM-IV diagnosis of anxiety disorder |

Parent self-report ● Depression Anxiety Stress Scale |

Significant Time x Group interaction for BIQ inhibition, both maternal and paternal rating |

|

Quality Good 64% (18/28) |

Intervention:

N = 35 Age: 48.4±7.1 months Gender: 42% M, 58% F Diagnosis: Not reported |

Exclusion: None reported |

Mother report ● STSC; Approach subscale |

Significant Time x Group interaction for Behaviour Inhibition Composite | ||

|

Waitlist Control:

N = 36 Age: 45.8±6.9 months Gender: 49% M, 51% F Diagnosis: Not reported |

Definition: Behavioural inhibition |

Parent report ● BIQ ● PAS ● Child Anxiety Life Interference Scale-Preschool Version |

Significant reduction in Global Inhibition, with significant Time x Group interaction | |||

|

Teacher report NA |

46.7% of children in intervention group no longer had anxiety disorder, compared to 6.7% of control, significant difference | |||||

|

Clinician rating of parent ● ADIS-C; Parent Version |

Significant reduction in clinical severity ratings, Group x Time interaction | |||||

|

Observations ● Behavioural inhibition across a number of activities with unfamiliar female assessor; Inhibition composite and Global Inhibition rating+ |

Significant main effect for time on maternal and paternal PAS-R ratings | |||||

| Significant Group x Time interaction for maternal and paternal ratings of life interference | ||||||

| Maternal and paternal report of own anxiety did not show significant change over time or by group | ||||||

|

Cognitive bias modification training Interpretation bias |

Klein, Rapee [40], Australia |

NHMRC Level III-2 |

Total sample:

N = 83 Age: 9.2±1.5 Gender: 43 M, 40 F Diagnosis (%): generalised anxiety (89.2), social phobia (68.7), separation anxiety (44.6), other anxiety disorders (n = 55), mood disorder (n = 12), behaviour disorder (n = 17) |

Inclusion: Primary anxiety disorder, aged 7–12 years. |

Self-report ● Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale- Child Version |

No main effects or interactions for social threat or general threat scenarios |

|

Quality Strong 82% (23/28) |

Positive training:

N = 40 Age: 9.1±1.6 Gender: 22 M, 18 F Diagnosis: Not reported |

Exclusion: Life threatening suicidal ideation, in physically or sexually abusive environments, under current psychological treatment, significantly intellectually impaired, had unmanaged psychotic symptoms |

Parent report ● Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale- Parent Version |

Significant Time x Set interaction for non-threat scenarios; children had difference scores over time depending on the scenario set of interpretation task | ||

|

Neutral training:

N = 43 Age: 9.4±1.4 Gender: 21 M, 22 F Diagnosis: Not reported |

Definition: Clinically anxious, anxiety disorder |

Teacher report NA |

Significant reduction in interpretation biases for social threat scenarios in positive group No significant reduction for neutral group |

|||

|

Clinician rating ● ADIS-C; Parents and child version |

No significant effect of positive training on children’s self-reported social, generalised or separation anxiety | |||||

|

Performance ● Interpretation task; Asked to read aloud 3 sets of 15 scenarios presented on a computer screen and choose the ending they thought would best fit; Non-threat, social threat and physical threat scenarios+ |

Significant reduction in social anxiety in mother and father-reports | |||||

|

UTalk- Interpersonal Psychotherapy Adolescent Skills Training Social anxiety, depression, peer relationships, approaching other peers, coping with peer victimisation |

La Greca, Ehrenreich-May [41], USA |

NHMRC Level IV |

Total sample:

N = 14 Age: 15.64±1.28 Gender: 21.4% M, 78.6% F Diagnosis (%): social anxiety (71) |

Inclusion: Elevated levels of symptoms of social anxiety of depression, elevated levels of relational or reputational peer victimisation on screening measures |

Self report ● Revised Peer Experiences Questionnaire ● SAS-A+ ● Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale ● Youth Self Report; Aggression subscale ● Cyber-Peer Experiences ● Perceived Social Support Scale |

Significant decrease from baseline to post-intervention for clinician ratings of severity of ADIS-C and CGI |

|

Quality Good 77% (17/22) |

Exclusion: Aggressive behaviour, overt victimisation |

Parent report NA |

Significant decrease in relational and reputational peer victimisation | |||

| Definition: Social anxiety |

Teacher report NA |

Significant decrease in report of cyber peer victimisation | ||||

|

Clinician rating ● ADIS-C ● CGI ● Columbia-Suicide Severity Scale |

Significant decrease in social anxiety and depression symptoms | |||||

|

Observations NA |

Increases in perceived social support from friends | |||||

|

Second Life Self-expression |

Lee [42], South Korea |

NHMRC Level III-3 |

Total sample:

N = 60 Age: 5th Grade Gender: 34 M, 26 F Diagnosis: Typically developing |

Inclusion: 5th grade elementary class in participating school; group membership determined by scores on shyness scale |

Self report ● Revised Cheek and Buss Shyness and Sociability Scale+ ● Self-Administered Assertiveness scale |

High shyness group had a lower baseline level of self-expression than low shyness group |

|

Quality Good 77% (17/22) |

High shyness:

N = 30 Age: Not reported Gender: 16 M, 14 F Diagnosis: Typically developing |

Exclusion: None reported |

Parent report NA |

High shyness group showed an average increase in self-expression of 3.14 | ||

|

Low shyness:

N = 30 Age: Not reported Gender: 18 M, 12 F Diagnosis: Typically developing |

Definition: Feeling of apprehension, discomfort of awkwardness in unfamiliar situations/with unfamiliar people |

Teacher report NA |

Low shyness group showed an average increase in self-expression of 1 | |||

|

Clinician rating NA |

High shyness group had significantly greater improvements, compared to low shyness group | |||||

|

Observations NA |

||||||

|

Social Skills Training Facilitated Play (SST-FP) |

Li, Coplan [43], China |

NHMRC Level III-2 |

Total sample:

N = 16 Age: 4.68±0.28 Gender: 8 M, 8 F Diagnosis: Typically developing |

Inclusion: Aged 4–5 years, parent-rated shyness below top 25% of CBQ, nominated by teacher as top 5 shy children, no known developmental/psychiatric disorder |

Self report NA |

Main effect of Time for peer interaction during free play |

| Initiating/maintaining conversions, understanding/expressing feelings, emotion regulation, peer interaction |

Quality Strong 96% (27/28) |

Intervention:

N = 8 Age: Not reported Gender: 4 M, 4 F Diagnosis: Typically developing |

Exclusion: Known psychiatric or developmental disorder |

Parent report ● CBQ |

Intervention group engaged in significantly more peer interaction than control, immediately following intervention | |

|

Comparison:

N = 8 Age: Not reported Gender: 4 M, 4 F Diagnosis: Typically developing |

Definition: Excessive wariness and unease in social novelty and perceived social evaluation |

Teacher report NA |

Difference maintained at 2-month follow-up | |||

|

Clinician rating NA |

Main effect of Time for frequency of prosocial behaviours | |||||

|

Observations ● Adapted Play Observation Scale; Time spent in peer interaction, frequency of prosocial behaviours+ ● Observation during self-presentation speech sessions; Amount of eye contact, nervous affect, positive body posture |

Intervention group engaged in significantly more prosocial behaviours than control, immediately following intervention | |||||

| Difference maintained at 2 month follow-up | ||||||

| Main effect of Time for speech performance | ||||||

| Intervention group performed significantly better during speeches than control, immediately following intervention | ||||||

| Implosive, Counselling and Conditioning Approach | Lowenstein [44], England |

NHMRC Level III-2 |

Total sample:

N = 22 Age: 9–16 years Gender: 6 M, 16 F Diagnosis: Not reported |

Inclusion: Known to teachers as timid, totally or virtually eschewed social contact, scores below 8 on MPI Extroversion scale |

Self report NA |

Children in intervention group showed significantly lower timidity ratings post-intervention, compared to control |

| Eye contact, interest in communication with others, mixing socially, assertiveness |

Quality Good 64% (18/28) |

Intervention:

N = 11 Age:9–16 years Gender: Not reported Diagnosis: Not reported |

Exclusion: Score above 5 on MPI Psychoticism scale |

Parent report NA |

Significant increase in extroversion for intervention group, compared to control | |

|

Control:

N = 11 Age:9–16 years Gender: Not reported Diagnosis: Not reported |

Definition: Easily frightened, timid, bashful, shrinking from approach or familiarity |

Teacher report ● MPI ● Timidity rating+ |

||||

|

Clinician rating NA |

||||||

|

Observations NA |

||||||

|

Cool Little Kids |

Luke, Chan [45], Hong Kong |

NHMRC Level III-2 |

Total sample:

N

= 57 Age: 3.91±0.60 Gender: 35 M, 22 F Diagnosis: Typically developing |

Inclusion: Level of behavioural inhibition, attending a local kindergarten, no known childhood developmental disorder, not receiving services for learning disabilities |

Self report NA |

Significant main effect of Time on anxious shyness |

| Parental overprotection, avoidance |

Quality Strong 86% (24/28) |

Intervention:

N = 25 Age: 3.84 Gender: 11 M, 14 F Diagnosis: Typically developing |

Exclusion: Known childhood developmental disorder, receiving services for learning disabilities |

Parent report ● BIQ |

Significant Time x Group interaction on anxious shyness | |

|

Control:

N = 20 Age: 3.98 Gender: 16 M, 4 F Diagnosis: Typically developing |

Definition: Behavioural inhibition |

Teacher report ● BIQ ● Chinese Shyness Scale+ ● Social Competence Inventory ● CBS |

Intervention group showed significant decrease in anxious shyness, compared to control | |||

|

Clinician rating NA |

Significant main effect of Time on social initiative | |||||

|

Observations NA |

Significant main effect of Time on internalising problems | |||||

|

Pyramid Program Problem-solving, assertive communication, relaxation, emotional expression |

McKenna, Cassidy [46], Northern Ireland |

NHMRC Level III-2 |

Total sample:

N = 82 Age: 7–8 years Gender: Not reported Diagnosis: Not reported |

Inclusion: SDQ scores in normal range, displaying subtle changes in withdrawal, known to be experiencing difficulty at home OR scored in borderline or abnormal range for SDQ Emotional or Peer Problems, but no comorbid externalising problems |

Self report NA |

Changes in emotional symptoms and peer problems dependent on group membership |

|

Quality Strong 91% (20/22) |

Intervention:

N = 57 Age: 7–8 years Gender: 41.7% M, 48.3% F Diagnosis: Not reported |

Exclusion: Those not meeting above criteria were included in control group |

Parent report NA |

No significant interaction for prosocial skills | ||

|

Control:

N = 31 Age: 7–8 years Gender: 50.6% M, 49.4% F Diagnosis: Not reported |

Definition: Behavioural withdrawal, wariness in the face of novelty and social evaluation |

Teacher rating ● SDQ; Emotional, Peer Problems and Pro-social subscales+ |

33.3% of Intervention group in abnormal range for emotional symptoms at baseline; decreased to 6.3% post-intervention; increased to 10% at 12-week follow-up | |||

|

Clinician rating NA |

22.8% of Intervention group in abnormal or borderline range for peer problems at baseline; decreased to 3.2 post-intervention; increased to 5.8% at 12-week follow-up | |||||

|

Observations NA |

35.6% of Intervention group experiencing peer exclusion at baseline; decreased to 13.7% post-intervention; increased to 24.3% at 12-week follow-up | |||||

|

INSIGHTS Academic development, critical thinking, math, language, empathy, problem solving |

O’Connor, Cappella [47], USA |

NHMRC Level III-2 |

Total sample:

N = 345 Age: 5.38±0.61 Gender: 50% M, 50% F Diagnosis: Typically developing |

Inclusion: Enrolled in kindergarten at participating school, first 10 to sign up |

Self report NA |

No significant main effect for treatment |

|

Quality Strong 86% (24/28) |

Intervention:

N = 183 Age: Not reported Gender: Not reported Diagnosis: Typically developing |

Exclusion: None reported |

Parent report ● School-Aged Temperament Inventory |

Children with shyer temperaments showed lower scores on critical thinking, language and math | ||

|

Control:

N = 162 Age: Not reported Gender: Not reported Diagnosis: Typically developing |

Definition: fearful, anxious, wary, and reluctant to take part in interactions with others in situations that involve novelty or actual/perceived judgement |

Teacher report ● Academic Competence Evaluation Scale; Critical thinking, reading/writing, mathematics subscales |

Significant Treatment x Time x Shy effect for critical thinking and math | |||

|

Clinician rating NA |

Shy children in treatment group experienced stable math skills, compared to a decrease in control group | |||||

|

Observations ● Behavioural Observation of Students in Schools; Frequency of engagement in academic activities+ |

Shy children in treatment group increased critical thinking skills, compared to decrease in control group | |||||

| Improvement in behavioural engagement partially mediated relationship between treatment and critical thinking, and math | ||||||

|

Parent education program Child temperament |

Rapee and Jacobs [48], Australia |

NHMRC Level IV |

Total sample:

N = 7 Age: 56.3±4.1 months Gender: 7 M Diagnosis: Typically developing |

Inclusion: Top 25% on Childhood Temperament Questionnaire-Approach scale |

Self report NA |

Significant effect of Time on CTQ across pre-, post-intervention and 6-month follow-up |

|

Quality Strong 85% (17/20) |

Exclusion: Already receiving therapy |

Parent report ● Childhood Temperament Questionnaire- Australian Adaptation ● Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale-Modified + |

Change from pre- to post-intervention not significant | |||

| Definition: socially withdrawn |

Teacher report NA |

Change from pre-intervention to follow-up significant | ||||

|

Clinician rating NA |

Significant effect of Time on anxiety across pre-, post-intervention and 6 month follow-up | |||||

|

Observation NA |

Significant changes pre- to post-intervention, and pre-intervention to follow-up | |||||

| Rapee, Kennedy [49], Australia |

NHMRC Level III-2 |

Total sample:

N = 146 Age: 46.8 months Gender: Not reported Diagnosis: Typically developing |

Inclusion: Score above 30 on STSC Approach scale, above cut-off on 3 behaviours on behavioural observation |

Self report NA |

Significant reduction in anxiety disorders at 12-month follow-up for Intervention group | |

|

Quality Good 75% (21/28) |

Intervention:

N = 73 Age: 47.3±5.1 months Gender: 40% M, 60% F Diagnosis: Typically developing |

Exclusion: None reported |

Parent report ● STSC ● Temperament Assessment Battery for Children-Revised ● ADIS-C; Parent Version+ |

Inhibition at 12 months was not influenced by group membership | ||

|

Control:

N = 73 Age: 46.1±4.4 months Gender: 51% M, 49% F Diagnosis: Typically developing |

Definition: Inhibited or withdrawn temperament |

Teacher report NA |

||||

|

Clinician rating NA |

||||||

|

Observations ● Behavioural inhibition: Total amount talking, total time near mother, duration of staring at peers, frequency of approach to strangers and peers |

||||||

|

Cognitive-behavioural approach-based social skills training Internalising behaviours |

Sang and Tan [50], China |

NHMRC Level III-2 |

Total sample:

N = 29 Age: 9–12 Gender: Not reported Diagnosis: Typically developing |

Inclusion: Suspected of internalising disorder, aged between 9 and 12, speaking Chinese, basic reading/writing skills |

Self report NA |

Significant decrease in anxiety for Intervention group at post-intervention and 2 month follow-up |

|

Quality Good 71% (20/28) |

Intervention:

N = 16 Age: 9–12 Gender: Not reported Diagnosis: Typically developing |

Exclusion: None reported |

Parent report ● CBCL Internalising scale + ● Social Competence Scale |

Significant increase in anxiety for Control at post intervention and 2 month follow-up | ||

|

Control:

N = 13 Age: 9–12 Gender: Not reported Diagnosis: Typically developing |

Definition: Internalising disorder |

Teacher report NA |

Significant decrease in depression for Intervention group at post-intervention and 2 month follow-up | |||

|

Clinician rating NA |

Significant increase in depression for Control at post intervention and 2 month follow-up | |||||

|

Observations NA |

Significant decrease in withdrawal for Intervention group at post-intervention and 2 month follow-up | |||||

| Significant increase in withdrawal for Control at post intervention and 2 month follow-up | ||||||

|

Group cognitive behavioural therapy Relaxation, social skills, overall shyness |

Umeh [51], Lagos |

NHMRC Level III-2 |

Total sample:

N = 36 Age: 14.63±2.47 Gender: Not reported Diagnosis: Typically developing |

Inclusion: highest 36 scores on SS-34 |

Self-report ● Shyness Scale 34+ |

Significant effect of between-subject factor groups |

|

Quality Good 79% (22/28) |

Intervention:

N = 18 Age: 10–19 Gender: Not reported Diagnosis: Typically developing |

Exclusion: None reported |

Parent report NA |

59% of overall variance accounted for by treatment | ||

|

Control:

N = 18 Age: 10–19 Gender: Not reported Diagnosis: Typically developing |

Definition: Discomfort in social situations |

Teacher report NA |

Intervention group showed reduction in shyness levels, compared to Control | |||

|

Clinician rating NA |

||||||

|

Observations NA |

||||||

|

Emotion recognition training program Emotion recognition, perception of happiness in others |

Rawdon, Murphy [52], UK/Ireland |

NHMRC Level II |

Total sample:

N = 92 Age: 15.77±0.66 Gender: 33 M, 59 F Diagnosis: Typically developing |

Inclusion: Score above 21 on SPAIC-C |

Self-report ● SPAI-C+ ● BFNE-R ● SCARED ● RCADS-MDD ● Emotion recognition balance point |

Significant main effect of Time of SPAI-C total score |

|

Quality Strong 96% (27/28) |

Intervention:

N = 49 Age:15.71±0.68 Gender: 17 M, 32 F Diagnosis: Typically developing |

Exclusion: Score below 21 on SPAI-C; parent reported diagnosed mental health disorder and/or attending mental health professional |

Parent report NA |

Significant decrease in SPAI-C scores from pre-intervention to 2-week follow-up | ||

|

Control:

N = 43 Age:15.84±0.65 Gender: 16 M, 27 F Diagnosis: Typically developing |

Definition: Social anxiety |

Teacher report NA |

Significant decrease in SPAI-C scores from post-intervention to follow-up | |||

|

Clinician rating NA |

No different in SPAI-C scores from pre- to post-intervention | |||||

|

Observations NA |

No main effect of Training or Time x Training interaction | |||||

| Time x Training interaction of balance point scores; significant effect of Time on intervention group, but not control group, for balance point scores | ||||||

| Main effect of Time of SCARED total scores | ||||||

| Time x Training interaction on RCADS-MDD; significant effect of Time on intervention group but not control |

Notes

1 NHRMC hierarchy: Level 1 Systematic reviews; Level II Randomized control trials; Level III–1 Pseudo-randomized control trials; Level III–2 Comparative studies with concurrent controls and allocation not randomized (cohort studies), case control studies, or interrupted time series with a control group; Level III–3 Comparative studies with historical control, 2 or more single-arm studies, or interrupted time series without a control group; Level IV Case series.

2 Methodological quality: Strong > 80%; good 60–79%; adequate 50–59%; poor < 50%.

ADHD = Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder; BFNE-R = Brief Fear of Negative Evaluation- Revised; BIQ = Behavioural Inhibition Questionnaire; CBCL = Child Behaviour Checklist; CBS = Child Behaviour Scale; CGI = Clinical Global Impressions; CIRP = Children’s Intervention Rating Profile; DSM-IV = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; GAD = Generalised Anxiety Disorder; K-GAS = Children’s Global Assessment Scale; MASC = Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children; MPI = Maudsley Personality Inventory; NOS = Not Otherwise Specified; OCD = Obsessive Compulsive Disorder; ODD = Oppositional Defiance Disorder; PAS = Preschool Anxiety Scale; RCADS-MDD = Revised Child Anxiety and Depression Scale–Major Depressive Disorder; SAS = School Anxiety Scale; SAS-A = Social Anxiety Scale for Adolescents; SCARED = Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders; SDQ = Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire; SIBS = Student Internalising Behaviour Screening; SOC = Sense of coherence; SPAI = Social Phobia and Anxiety Inventory; SPAI-C = Social Phobia and Anxiety Inventory for Children; STAI-C = State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children; STSC = Short Temperament Scale for Children; SUD = Subjective units of distress; TRF = Teacher Report Form; + main shyness outcome measure extracted for meta-analysis.

Data items, risk of bias and synthesis of results

Risk of bias in the included studies was assessed at an individual study level using the Kmet appraisal checklist [26]. Risk of bias was minimised in this process by having a full overlap between independent abstract and article reviewers, and by two independent assessors independently scoring 100% of the methodological quality of included studies. Final study selection and quality assessment were the result of consensus-based ratings. Discrepancies were resolved by involving a third reviewer. No author of this review was affiliated with any of the included studies. Extracted data were synthesised in relation to the methodological characteristics of each included study and the findings of individual studies with regards to the treatment outcomes of shyness interventions.

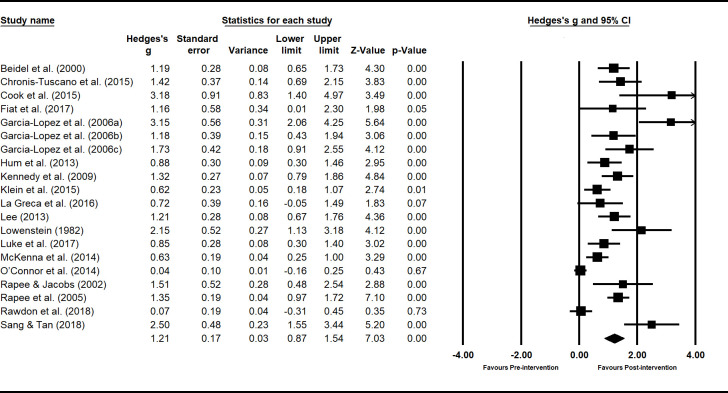

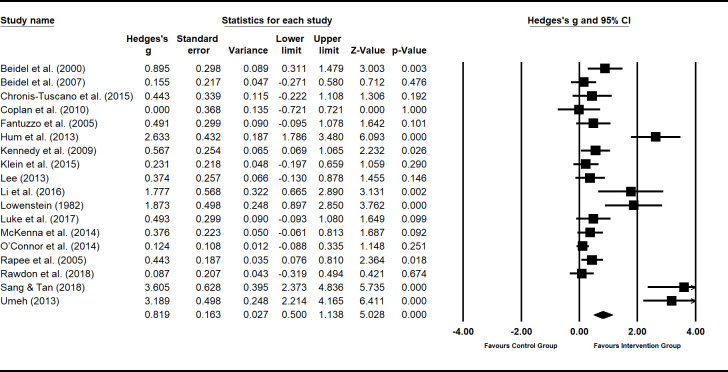

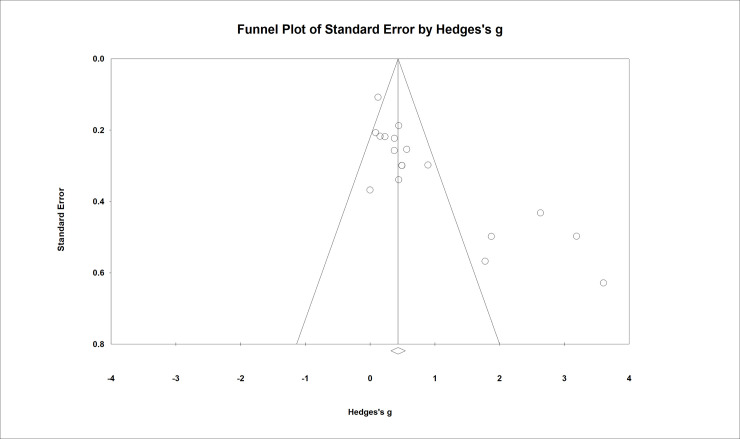

Meta-analysis

Using the extracted data from the main outcome measure related to shyness, estimates were calculated of pooled effect sizes weighted by sample size using random-effects models for summary statistics. To determine potentially confounding variables, effect sizes of shyness interventions were grouped by setting (school, clinic and/or home), focus (child and/or parents), mode of delivery (individual and/or group sessions), and rater of outcome measures (child, parents, clinician and/or teacher). The Hedges-g formula for standardized mean difference (SMD) with a 95% confidence interval (95% CI) was used to report effect sizes. A test for overall effect for each intervention setting, mode, focus and outcome rater produced a weighted effect size (z). Tests for heterogeneity were conducted to identify inconsistency in treatment effects, included I2 and chi-square (Q). All statistical analyses were performed using software package Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Version 3.3.070 (Biostat; Englewood, NJ, USA).

Within-groups effects were examined by analysing the pre-post data for studies both with and without control groups. The benefit of within-groups analyses is that it allows the examination of the effect of an intervention in and of itself, without controls. Between-groups analyses (comparing results of control group to that of intervention group) were also conducted. This allows comparison of different forms of interventions against each other.

Results

Systematic review

Study selection

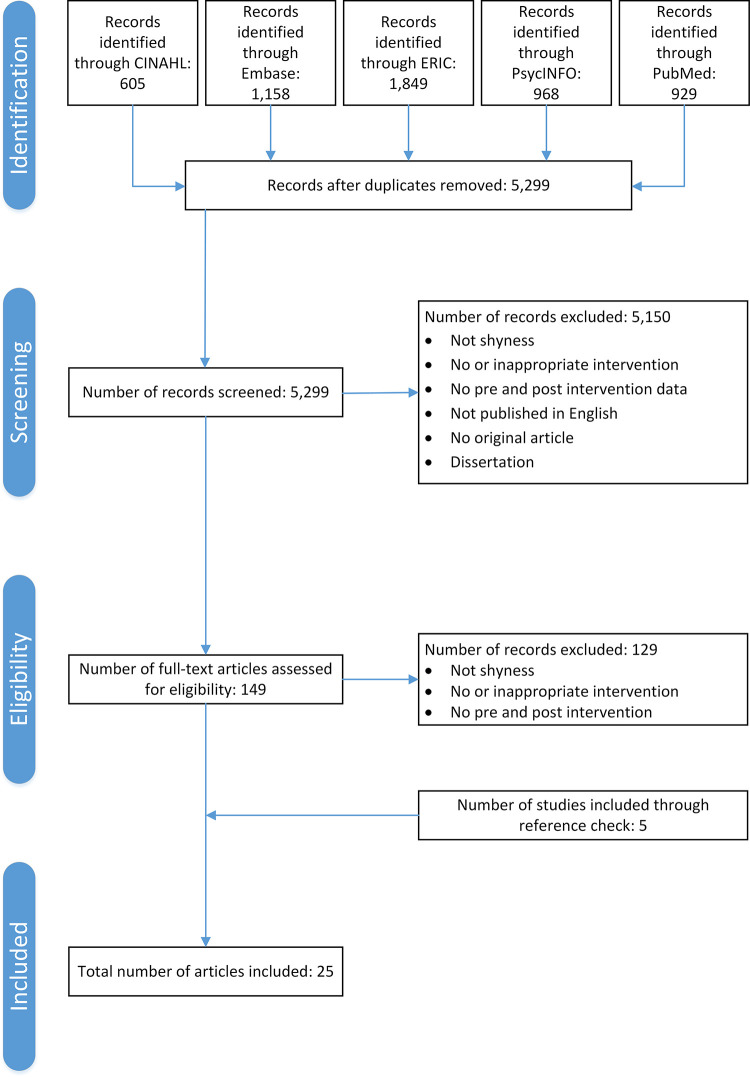

A total of 4,864 articles were identified (CINAHL: n = 605, Embase: n = 1158, ERIC: n = 1849, PsycINFO: n = 968 and PubMed: n = 929). After the removal of duplicate articles, 5299 abstracts were screened. A total of 149 studies were assessed at a full text level for eligibility. Of these, 129 were excluded and 20 were included (see Fig 1). No studies were excluded due to poor quality. An additional five studies were included through searching the reference lists of the 20 studies that met the inclusion criteria. This resulted in a total of 25 included studies.

Fig 1. Flow diagram of the review process according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA).

Adapted from Moher et al.

Participants of studies included in the systematic review

The total number of participants across the 25 included studies was 1,895, with the average participants across studies 75.8. Griffin, Caldarella [28] had the largest sample of 388 participants and Cook, Xie [29] the smallest sample of 5 participants. The average age of total participants across the studies was 9.1 years (SD = 5.4), with the average age of the total sample not reported in nine studies. Of the 25 studies, only five had more male than female participants, with four studies not reporting the gender of the total or sub-samples. While a range of diagnoses were reported across some studies, 13 studies reported the sample to be typically-developing and five studies did not report diagnosis. Studies were conducted across nine countries, with the highest number conducted in the USA (n = 10), followed by Australia (n = 4). Additional details on participant characteristics are reported in Table 2.

Study design, methodological quality and risk of bias of studies included in the systematic review

Most studies were randomised or pseudo-randomised control trials, with only three employing a multiple baseline design (see Table 2). The methodological quality for each study according to Kmet criteria is reported in Table 2. The average methodological quality rating across all studies was 83.4% (SD: ±8.7, range: 64–96%), indicating “strong” methodological quality. Of the studies, 17 were rated as “strong”, with all others rated to have “good” methodological quality. No study was rated to have adequate or poor methodological quality.

Shyness outcome measures

While studies reported several outcome measures, only those relevant to shyness and/or social anxiety were the focus of this review. Across categories of self-report, parent-report, teacher-report, clinician-rating and observation measures of shyness, self- reported (n = 13) and parent-reported (n = 13) shyness outcome measures were most frequently used and clinician-rating was used least across studies (n = 7; see Table 2). Using the categories of outcome measures above, nine studies used two different types of outcome measures, seven studies used only one type of outcome measure, and nine studies used three or more types out outcome measures.

Interventions

The majority of studies included an intervention that was delivered weekly (n = 15), in a child group format (n = 14), in the school setting (n = 10). Only four studies reported session durations of 40 minutes, with 14 reporting sessions for 60 minutes or longer. Intervention delivery was reported to be at least 7 weeks in 17 studies (see Table 3).

Table 3. Characteristics of interventions.

| Intervention/Target Skills | Procedure | Interventionists | Duration/Setting/Mode of Delivery | Tailoring/Modifications | Active Ingredients |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Social Effectiveness Training for Children (SET-C) Social anxiety and fear, social skill, interpersonal functioning, participation in social activities |

Stand-alone educational session was held for parents and children about social phobia. Treatment sessions consisted of 4–6 children with a social skills training component. One social skill was taught each week using instruction, modelling, rehearsal and corrective feedback. Followed by 90 min of peer-generalisation with non-anxious peers. Different peers were used each week. Children were assigned homework on each week’s content. Once a week, in vivo exposure sessions were conducted of anxiety-inducing scenarios until anxiety dissipates (45–75 min). |

Therapist Qualifications: Not reported Relationship: Not reported |

Dosage 36 hours Individual sessions: 1 x 60–90 minutes weekly sessions, for 12 weeks Group sessions: 1 x 60–90 minutes weekly sessions, for 12 weeks |

None reported | ● Psychoeducation ● Social skills training ● Therapist modelling ● In vivo exposure ● Behaviour modification |

| Beidel, Turner [30], Beidel, Turner [31] |

Mode Child individual Child group |

||||

|

Setting Not reported |

|||||

|

Problem-solving and conversational skills training Recognising a problem, defining a problem, generating solutions, evaluating consequences, determining best solution, implementing a solution, listening, talking about oneself, initiating conversations, making requests of others |

Four problem-solving skills training sessions. In the first session, therapists provide a rationale for learning skills, remaining sessions involve applying skills to interpersonal problems. Students complete a worksheet and discuss in subsequent session. Social skills training is conducted for next four sessions. Each session focused on a different topic, discussed and modelled by therapist and rehearsed by participants. Participants role-play skills with one another and are given feedback by therapists. Participants are assigned homework to practice skills at home. |

Therapist Qualifications: Clinical psychology interns Relationship: Not reported |

Dosage 7 hours Group sessions: 1 x 40-minute group sessions weekly, for 8 weeks (4 x problem solving skills sessions, 4 x conversational skills training sessions) |

None reported | ● Therapist modelling ● Social skills training |

| Christoff, Scott [32] |

Mode Child group |

||||

|

Setting School |

|||||

|

Turtle Program Social skill, introducing self, eye contact, communication, relaxation, expressing emotions, working together, exposure to fear |

Parent component: Parents attended 8 sessions. Sessions included psychoeducation and teaching and coaching of each Child-Direction Interaction, Bravery-Directed Interaction and Parent-Direction Interaction. Parents learn to adopt a “step behind” approach, provide praise for their child’s behaviours, apply skills in anxiety-provoking social situations for their child, and distinguish between anxiety and oppositional behaviours. Coaching sessions involved dyadic parent-child coaching. Parents received instructions for out of session exposures. The final session was a “graduation party” were parents were coached to use their skills |

Therapist Qualifications: Not reported Relationship: Not reported |

Dosage Parents: 12 hours Parent sessions: 1 x 90-minute sessions weekly, for 8 weeks Child: 12 hours Child group sessions: 1 x 90-minute sessions weekly, for 8 weeks |

None reported | ● Social skills training ● Psychoeducation ● Therapist modelling ● Behaviour modification ● In vivo exposure |

| Chronis-Tuscano, Rubin [33] | Child component: Adapted from Social Skills Facilitated Play. Children attended 8 group sessions. Session topics included learning to introduce yourself, making eye contact, relaxation, communicating to keep friends, facing your fears, expression emotions, working together and group activities. Skills were taught using puppets and games. After teaching portion, children engaged in free play and group activities, using modelling, guided participation and reinforcement of social skills by therapists. Activities, such as Show and Tell, were incorporated to allow for exposure to feared situations. |

Parent Qualifications: NA Relationship: Parent of participating child |

Mode Child group Parent group |

||

|

Setting Clinic | |||||

|

The Courage and Confidence Mentor Program Internalising problems |

Mentors were any educational professional at the student’s school that participated in a 60 min training session. Prior to intervention, mentors held 2 x 40 min sessions. The first session was to build rapport and present life bus metaphor, used to normalise emotion and provide language to talk about emotions. The second session comprised a brief review of content and “courage tools”. The intervention consisted 0f a) assignment of a mentor with unconditional positive regard; b) morning meetings for positive interaction, words of encouragement and pre-correction of problems; c) daily mentoring of performance and d) afternoon meetings for positive interaction and performance-based feedback. During meetings, students would provide daily ratings of distress. | Mentor: School psychologist and special education resource teacher; 60-min show and tell training, provided materials to support implementation |

Dosage 6 hours Individual content sessions:2 x 40 min content sessions at beginning of intervention Individual mentor sessions: 2 x 5–10 minute sessions daily, for 3 weeks |

Altering nature of communication between mentor and student | |

| Cook, Xie [29], Fiat, Cook [34] |

Mode Child individual |

For older students, used toy bus and figures to represent students themselves, to make metaphor more concrete | |||

|

Setting School | |||||

|

Play Skills for Shy Children Social skills, initiating and maintaining interactions, expressing and understand emotions, relaxation techniques |

Each session involved a 5-minute free play period, followed by circle time sessions to provide didactic content. Leaders focused on specific set of skills each week, using songs, games and puppets to teach content. The first three sessions focused on initiating and maintaining peer interactions. The next three focused on understanding and expressing feelings. Sessions then comprised of leader-facilitated free play, where leaders prompted, modelled and reinforced skills discussed in circle time. Each session ended with a structured positive social activity. |

Therapist Qualifications: Female leaders with previous early childhood education experience, trained by senior authors Relationship: Not reported |

Dosage 8 hours Group sessions: 1 x 1-hour sessions a week for 7 weeks Booster session: 1x 1-hour booster session, approx. 1 month after completion |

None reported | ● Behaviour modification |

| Coplan, Schneider [35] |

Mode Child group |

||||

|

Setting Community centre |

|||||

|

Resilient Peer Treatment Positive play skills, routine Fantuzzo, Manz [36] |

Play Supporter arranges play corner, a designated area for Play Partner (participant) and Play Buddy to use for play. Play Supporter then spends a few minutes one-on-one with Play Buddy identify what behaviours resulted in positive interactions with Partner. During play sessions, Supporters observes session and makes supportive comments to Partner and Buddy about their interactive play at end of session. |

Parent Play Supporters Qualifications: NA Relationship: Family volunteers with high levels of supportive and nurturing actions with children Peer Play Buddy Qualifications: NA Relationship: School peers with highest levels of prosocial peer play interactions |

Dosage Total hours not reported One on one play sessions: 15 x play sessions; 3 sessions per week for 5 weeks |

None reported | ● Therapist modelling ● Behaviour modification ● Social skills training ● Peer mediation ● Behavioural modification |

|

Mode Child group | |||||

|

Setting School | |||||

|

Mode Child group |

|||||

| Social Effectiveness Therapy for Adolescents- Spanish version (SET-Asv) | Participants first attend a group education session. Social skills training and exposure components are conducted during the first 13 weeks. Social skills training sessions involve 60-minute group sessions, learning to maintain conversation, give and receive compliments, establish and maintain friendships. Exposure sessions are conducted concurrently, in an individual format. Programmed practice sessions are completed once social skills training and exposure sessions are finished, aiming to maximise generalisation to natural environment |

Therapist Qualifications: Not reported Relationship: Not reported |

Dosage: 24.5 hours Individual group sessions: once off session, 60 minutes Group sessions: 1 x 60 min group sessions a week for 13 weeks Individual exposure sessions: 1 x 30 min individual sessions a week Individual programmed practice: 4 x 60 min sessions |

Spanish language Adapted for adults |

● Psychoeducation ● Social skills training ● In vivo exposure |

| Garcia-Lopez, Olivares [37] |

Mode Child group Child individual |

||||

|

Setting Not reported |

|||||

| Cognitive-Behavioural Group Therapy for Adolescents (CBGT-A) | Involves two phases with eight sessions each: 1) Educative and skills building and 2) Exposure. In first phase, therapist provides information about the program and delivers presentation on social phobia. The skills building unit involves teaching social skills, problem solving and cognitive restructuring. The second phase involves behaviour rehearsals and in vivo exposures within the session and as homework. |

Therapist Qualifications: Not reported Relationship: Not reported |

Dosage 24 hours Group sessions: 16 x 90-minute group treatment sessions over 14 weeks. First 4 sessions conducted within 2 weeks; remaining sessions happen weekly |

None reported | ● Psychoeducation ● Social skills training ● In vivo exposure ● Cognitive restructuring |

| Garcia-Lopez, Olivares [37] |

Mode Child group |

||||

|

Setting Not reported |

|||||

| Therapy for Adolescents with Generalised Social Phobia (IAFS) | Sessions included social skills training, exposure and cognitive restructuring techniques. Exposure to social stations used peer assistants to initiate/maintain conversations or public speaking in front of group mates and therapist for 5–10 mins. Exposure tasks are recorded and used as feedback. The last session focuses on relapse prevention. Weekly individual counselling sessions scheduled as needed. |

Therapist Qualifications: Not reported Relationship: Not reported Peer Qualifications: NA Relationship: Unknown to the participant |

Dosage 18 hours Group sessions: 1 x 90 min group sessions, for 12 weeks Optional individual sessions: weekly, as needed |

Optional individual counselling or telephone consultation with therapist | ● Social skills training In vivo exposure ● Cognitive restructuring ● Video modelling |

| Garcia-Lopez, Olivares [37] |

Mode Child group Child individual |

||||

|

Setting Not reported |

|||||

|

Buddy Bench Social involvement |

Observers, teacher and principal were trained in the intervention by principal investigator. Two specially decorated benches are placed in two playgrounds in the school. Teachers instructed students on how to use the bench, posted rules in every classroom and issues a daily school-wide announcement reminding students the use the bench. Students were instructed, if they felt alone, to sit at the bench. If someone invites them to play, say “yes” or “no thank-you”. If they saw a student at the bench, students were instructed to invite them to play. |

Teacher: Qualifications: 21 years experience as educator Relationships: Teachers of participant students Peer Qualifications: NA Relationship: Grades 1 to 6 classmates |

Dosage 10 weeks School-wide intervention: benches were placed in playgrounds for 10 weeks Mode School-wide |

None reported. | ● Peer mediation |

| Griffin, Caldarella [28] |

Therapist Qualifications: Not reported Relationship: Not reported |

Setting School |

|||

|

The Coping Bear Program Relaxation techniques, cognitive restructuring |