Abstract

Moral injury (MI), originally discussed in relationship to transgressing moral beliefs and values during wartime among military personnel, has expanded beyond this context to include similar emotions experienced by healthcare professionals, first responders, and others experiencing moral emotions resulting from actions taken or observations made during traumatic events or circumstances. In this article, we review the history, definition, measurement, prevalence, distinctiveness, psychological consequences, manifestations (in and outside of military settings), and correlates of MI in different settings. We also review secular psychological treatments, spiritually integrated therapies, and pastoral care approaches (specific for clergy and chaplains) used to treat MI and the evidence documenting their efficacy. Finally, we examine directions for future research needed to fill the many gaps in our knowledge about MI, how it develops, and how to help those suffering from it.

Keyword: Moral injury, PTSD, Military, Non-military, Religiosity, Religious struggles, Measurement, Treatment, Chaplains

Brief History

The concept of “moral injury” (MI), most recently, dates back to the work of military psychiatrist Shay (1994) when he described a syndrome in Vietnam war Veterans. However, the concept dates much further back than that, at least to the writings of Euripides (416 BCE). Euripides had originally described the syndrome using the term “miasma,” signifying the ancient Greek concept of moral defilement or pollution, often resulting from unjust killing, but applicable to any transgression of moral values, whether applied to the perpetrator, the victim, or even the observer. In the Athenian tragedy Herakles (a theater play) authored by Euripides, Herakles describes the feeling of miasma as follows:

What can I do? Where can I hide from all this and not be found? What wings would take me high enough? How deep a hole would I have to dig? My shame for the evil I have done consumes me… I am soaked in blood-guilt, polluted, contagious… I am a pollutant, an offense to gods above. (Euripides, 416 BCE)

It was not until Veterans Administration (VA) psychologist Litz et al., (2009) published a paper on MI in war Veterans, however, that the topic began to receive more widespread attention in the clinical and academic psychology world.

Definition

In that seminal paper by Litz et al., (2009), they defined MI as resulting from “an act of transgression that creates dissonance and conflict because it violates assumptions and beliefs about right and wrong and personal goodness…”. Following up on that, Brock and Letitini (2012) described MI as “a deep sense of transgression including feelings of shame, grief, meaninglessness, and remorse from having violated core moral beliefs” (p xiv). Transgressive and betrayal-based MI as described above is closely related to the term “moral distress”; MI occurs when moral distress is experienced repeatedly and the effects are long-lasting. More recently, Jinkerson (2016) updated the definition to emphasize the empirically and theoretically recognized symptoms of guilt, shame, spiritual/existential conflict, and loss of trust, with secondary symptoms of depression, anxiety, anger, self-harm, and social problems resulting from it. However, there remains considerable disagreement and lack of consensus regarding what falls under the category of “moral injury” (Hodgson & Carey, 2017). For example, some experts have included spiritual symptoms as a core dimension of MI (Drescher et al., 2011; Carey et al., 2016; Jinkerson, 2016; Kopacz et al., 2016; Frankfurt & Frazier, 2016; Hodgson & Carey, 2017), arguing that chaplains/clergy may be ideally positioned to address these issues, whereas other experts have largely minimized the spiritual, at least in terms of measurement [which reflects these researchers' definition of moral injury] (Currier et al., 2015a, 2015b; Litz et al., 2009; Nash et al., 2013).

Measurement

Once researchers defined the syndrome (albeit idiosyncratically), they began to focus on ways to identify MI. The first of these efforts was the work of military psychiatrist William Nash and colleagues who developed the Moral Injury Events Scale (MIES) based on work in active duty US Marines (Nash et al., 2013). This was followed by Joseph Currier and colleagues in their studies of US Veterans, developing the Moral Injury Questionnaire-Military version (MIQ-M) (Currier et al., 2015a, 2015b). These scales assessed both MI symptoms and events, which while useful in identifying those with MI, were less helpful in determining severity of symptoms and tracking change in symptoms over time in response to treatment. Since morally injurious events were in the past and could not be altered, including them together with symptoms reduced the sensitivity of these scales (see Koenig et al., 2019a). These scales were then followed by the development of “pure” MI symptom measures to assess the severity of symptoms and to track their change in response to treatment. Initially published online in the Journal of Religion and Health in December of 2017, the first such scale was the 45-item Moral Injury Symptom Scale-Military Version-Long Form (MISS-M-LF) (Koenig et al., 2018a). This was quickly followed by publication of the 17-item Expressions of Moral Injury Scale-Military Version (EMIS-M) (Currier et al., 2018), the 10-item Moral Injury Symptom Scale-Military Version-Short Form (MISS-M-SF; Table 1) (Koenig et al., 2018b), and the 4-item version of the EMIS-M (Currier et al., 2020). These scales typically assessed self-directed symptoms of MI (guilt, shame, self-condemnation) and “other-directed” symptoms (anger toward others, feelings of betrayal). Unique among the scales above, however, was the MISS-M-LF and MISS-M-SF, which included assessment of religious symptoms of MI such as religious struggles and loss of religious faith. (None of the other scales noted above contain religious or spiritual items.)

Table 1.

Moral injury symptom scale-military version-short form (MISS-M-SF)

| 1. I feel betrayed by leaders who I once trusted | |||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| Strongly disagree | Mildly disagree | Neutral | Mildly agree | Strongly agree | |||||

| 2. I feel guilt over failing to save the life of someone in war | |||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| Strongly disagree | Mildly disagree | Neutral | Mildly agree | Strongly agree | |||||

| 3. I feel ashamed about what I did or did not do during this time | |||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| Strongly disagree | Mildly disagree | Neutral | Mildly agree | Strongly agree | |||||

| 4. I am troubled by having acted in ways that violated my own morals or values | |||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| Strongly disagree | Mildly disagree | Neutral | Mildly agree | Strongly agree | |||||

| 5. Most people are trustworthy | |||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| Strongly disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly agree | |||||

| 6. I have a good sense of what makes my life meaningful | |||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| Absolutely untrue | Mostly untrue | Somewhat untrue | Can’t say true or false true | Somewhat true | Mostly true | Absolutely true | |||

| 7. I have forgiven myself for what happened to me or others during combat | |||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| Strongly disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly agree | |||||

| 8. All in all, I am inclined to feel that I am a failure | |||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| Strongly disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly agree | |||||

| 9. I wondered what I did for God to punish me | |||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| A great deal | Quite a bit | Somewhat | Not at all | ||||||

| (very true) | (very untrue) | ||||||||

| 10. Compared to when you first went into the military has your religious faith since then… | |||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| Weakened a lot | Weakened a little | Strengthened a little | Strengthened a lot | ||||||

| 11. Do the feelings you indicated above cause you significant distress or impair your ability to function in relationships, at work, or other areas of life important to you? In other words, if you indicated any problems above, how difficult have these problems made it for you to do your work, take care of things at home, or get along with other people? | |||||||||

| □ Not at all | □ Mild | □ Moderate | □ Very Much | □ Extremely | |||||

Psychometric properties reported in Koenig et al., 2018b, Military Medicine, 183(11–12), e659–e665

Prevalence

Using the MISS-M-LF, we have documented the prevalence of MI in 476 U.S. Veterans and active duty military found that over 90% of 373 Veterans reported high levels (9 or 10 on a 1–10 severity scale) of at least one MI symptom and 59% reporting five symptoms or more at this severity level (Koenig et al., 2018c). Likewise, in a study of 103 active duty military with PTSD symptoms, we found that over 80% had at least one symptom of MI of high severity (i.e., rated a 9 or 10 on a severity scale from 1 to 10) and 52% had four or more such symptoms (Volk & Koenig, 2019).

Research indicates that MI is also common among the active duty armed forces of other countries as well (Battaglia et al., 2019; Ferrajão & Aragão Oliveira, 2016; Levi-Belz et al., 2020; Williamson et al., 2021). For example, Hodgson et al. (2021) note the high prevalence of potentially morally injurious events (PMIEs) in a qualitative study of ten Australian Veterans, identifying seven common themes giving rise to MI symptoms: immoral acts (witnessed and perpetrated), death and injury (witnessed and perpetrated), betrayal (by others and self), ethical dilemmas (humanization/dehumanization and decision-making), disproportionate violence, retribution, and religious/spiritual issues. Given the nature of these PMIEs, the investigators underscore the role of Australian military chaplains in identifying and addressing these experiences that often underlie MI symptoms.

Distinction from PTSD

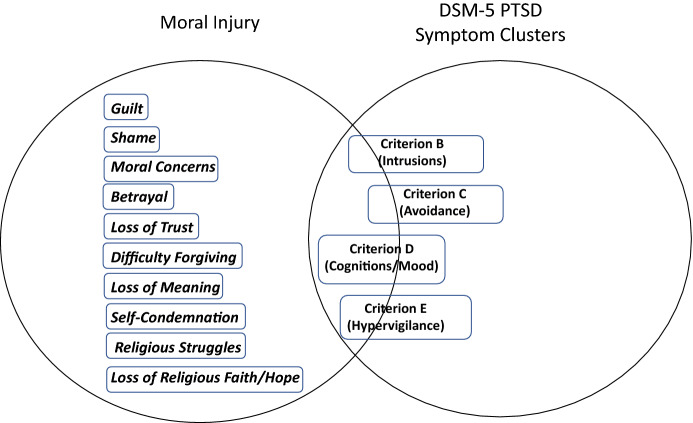

Although MI often occurs in the setting of severe trauma, it can be distinguished from PTSD (Brock & Lettini, 2012; Litz et al., 2009; Shay, 2014). MI is considered a separate syndrome from PTSD, but with some definitional overlap (Fig. 1). This overlap is largely limited to the affective domain (cluster D of the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for PTSD; American Psychological Association, 2013). MI may occur either in the presence of PTSD or in its absence. PTSD is diagnosed when a severe traumatic stressor is present (Criterion A; exposure to death, threatened death, actual or threatened serious injury, actual or threatened sexual violence) along with four major fear and trauma-based symptom clusters that adversely affect functioning in daily life: intrusive nightmares and flashbacks (Criterion B), avoidance (Criterion C), emotional negativity and numbing (Criterion D), and hyperarousal and irritability (Criterion E). MI, in contrast, develops when transgressions of moral beliefs or values are committed, observed, or learned about (Litz et al., 2009), with consequent feelings of guilt, shame, feelings of betrayal, moral concerns, difficulty forgiving, loss of meaning, loss of trust, self-condemnation, spiritual struggles, and loss of religious faith as a result of those moral transgressions (Koenig et al., 2018a). For some, transgressing moral beliefs or values in high stakes situations may be severely distressing affecting the ability to function in daily life, whereas for others, these events may be disturbing yet do not disrupt functioning.

Fig. 1.

Symptom overlap between moral injury and PTSD (from Koenig et al., 2020; used with permission). Criterion B cluster symptoms include intrusive unwanted upsetting memories, nightmares, flashbacks, emotional distress after exposure to traumatic reminders, and physical reactivity after exposure to traumatic reminders; Criterion C symptoms include avoidance of trauma-related thoughts, feelings, or external reminders of the trauma; Criterion D symptoms include negative thoughts or feelings related to the trauma, such as being unable to recall key features of the trauma, having overly negative thoughts and assumptions about oneself or the world, engaging in exaggerated blame of self or others, negative affect, difficulty experiencing positive affect, decreased interest in activities, and feeling isolated; and, finally, Criterion E symptoms include those of increased arousal or reactivity, such as feeling irritable or aggressive, engagement in risky or destructive behavior, hypervigilance, heightened startle reaction, difficulty concentrating, and difficulty sleeping

One might expect that regions of the brain that control moral processing would be more active among those with MI compared to those without, although this remains largely speculative at this time. Fear-based neural networks involved in PTSD, however, appear to be located in different areas of the brain than those involved with moral processing. Research suggests that MI and PTSD, while frequently co-occurring, are mechanistically different in terms of their neurophysiological basis (Barnes et al., 2019). There is evidence that resting-state brain fluctuation and functional conductivity are distinct in those with MI compared to those with PTSD, again providing support for the hypothesis that MI and PTSD are two different syndromes, each having dissociable neural underpinnings (Sun et al., 2019). Recent attempts using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) have been made to identify the neural correlates of recalling a morally injurious event among those with military or safety-related (first-responder) PTSD compared to civilian MI-exposed controls (Lloyd et al., 2021). These researchers found increased activation of brain areas involved in viscero-sensory processing and hyperarousal, brain regions involved in defensive responding and in top-down cognitive control of emotions. These findings suggest that MI event processing is altered in those with PTSD, compared to MI-exposed civilian controls without PTSD.

Psychological Consequences

Research indicates that MI is not a benign syndrome. MI in Veterans and active duty military has been associated with numerous adverse mental health outcomes, including greater severity of PTSD (Bryan et al., 2016; Koenig et al., 2018a; Nash et al., 2013), depression and anxiety (Currier et al., 2018; Evans et al., 2018; Koenig et al., 2018a, 2018b; Volk & Koenig, 2019) and increased risk of suicide (Ames et al., 2019; Bryan et al., 2013, 2014, 2015; Nieuwsma et al., 2021). Even after controlling for PTSD symptom severity, the presence of MI remains a significant risk factor for depression, anxiety, and suicide (Bryan et al., 2013, 2014, 2015; Nash et al., 2010, 2013), further justifying the claim that this condition is a distinct syndrome separate from PTSD. Veterans who utilize negative forms of religious coping (spiritual struggles) may be at particular risk for suicide (Currier et al., 2017).

Moral Injury Outside of Military Settings

Symptoms of MI may also be experienced by those outside of the military. The perceived transgression of moral values is common in healthcare professionals and first responders (police, firemen, emergency medical personnel) exposed to severe trauma, as well as among individuals experiencing any type of physical or severe emotional/physical trauma (rape, abortion, automobile accidents, other accidents, etc.). Such traumatized individuals often obsess about what they might have done differently to avoid the negative experience, and believe they carry personal responsibility for the event (because they did not do something to prevent it). Indeed, transgression of moral values is widespread among humans in general. The Christian scriptures say: “For all have sinned, and come short of the glory of God” (Roman 3:23, KJV), while later affirming that “if thou shalt confess with thy mouth the Lord Jesus, and shalt believe in thine heart that God hath raised Him from the dead, thou shalt be saved” (Romans 10:9, KJV). The Qur’an states: “But if you avoid the great sins you have been forbidden, We shall wipe out your minor misdeeds and let you in through the entrance of honor [into Paradise]” (Qur’an 4:31), implying that all persons transgress their moral code at some time or another. We now examine MI as it may occur in healthcare professionals, first responders, and civilians in high-stress circumstances.

Healthcare Professionals

Much of the recent work on MI in healthcare professionals (HCPs) has been done by a research group at Duke University and by work done with collaborators in China. Healthcare professionals often find themselves in situations (particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic) where they must make medical decisions that determine whether a person lives or dies, often in high-stress situations (e.g., placing a patient on a ventilator, when ventilators are in short supply; writing a do not resuscitate [DNR] order or equivalent; allowing for a natural death; and so forth). There are times when decisions must be made (or errors in judgment) that may lead to loss of life and legal ramifications over which there can be much remorse. Researchers at Duke University have adapted the ten-item MISS-M-SF for HCPs, specifically physicians and nurses, and psychometrically validated the measure in this population (Mantri et al., 2020). That measure has also been translated into Chinese and psychometrically validated in a large sample of physicians and nurses in China (Wang et al., 2020). When HCPs experience “burnout,” as is so common today, MI may be the actual underlying cause (Kopacz et al., 2019; Talbot & Dean, 2018). Furthermore, MI has been associated with increased medical errors among HCPs during the COVID-19 pandemic (Mantri et al., 2021a; Wang et al., 2021). It may be difficult, however, to determine whether such medical errors are the result of MI or its cause (Curlin 2005; Stovall et al., 2020).

First Responders

Research indicates that police (Papazoglou & Chopko, 2017; Papazoglou et al., 2020), paramedics and emergency medical technicians (Murray, 2019), firemen and other first responders (Joannou et al., 2017; Lentz et al., 2021) are at increased risk of MI because of their repeated exposure to violence, trauma, and severe injuries as part of their daily work. There are times when decision must be made (or errors in judgment) that may lead to loss of life, over which there is much remorse.

Civilians

Likewise, refugees (Nickerson et al., 2015), news journalists covering the refugee and migration crisis in Europe (Feinstein et al., 2018), and even teachers in public schools may experience MI (Currier et al., 2015b; Sugrue, 2020). Civilians experiencing the trauma of rape (Miller, 2009), abortion (Bernstein & Manata, 2019), physical assault or severe automobile accidents (where they may have been at fault or at least perceive they were) (Haight et al., 2016, 2020), or exposure to such accidents (Hoffman & Nickerson, 2021), all are at risk for MI. Even clergy, particularly during the recent COVID-19 pandemic, have not been immune to MI (Greene et al., 2020). One thing is clear. MI is not limited to those experiencing wartime trauma, since “combat” comes in many different forms—from efforts to provide healthcare, to providing help during emergency situations, to news reporters covering those severely traumatized, to educators in high-stress environments, to those experiencing the “slings and arrows of outrageous fortune” as part of routine (and sometimes not so routine) life. A ten-item measure of MI has been developed for use in civilians populations, again based on the MISS-M-SF (Koenig et al., 2019b, pp. 313–315).

Correlates, Predictors, and Moderators

A number of personal, behavioral, and situational characteristics may increase the risk of experiencing MI, depending on the particular situation in which a traumatic experience and/or moral transgression occurs. Some of these characteristics may (a) simply be correlated with MI, (b) lie along the pathway that leads to MI, (c) serve to maintain MI, or (d) moderate its severity. Unfortunately, there are few if any prospective studies or randomized controlled trials conducted to date that may help to establish causality among correlates of MI, as almost all research thus far has been cross-sectional in design.

War and Combat

The following have been found to be associated with MI in current or former members of the military: younger age (Koenig et al., 2018c; Volk & Koenig, 2019), white race (Koenig et al., 2018c; Wisco et al., 2017), lower education (Volk & Koenig, 2019; Wisco et al., 2017), less income/unemployed (Wisco et al., 2017), low social support or poor quality of relationships (Koenig et al., 2018c; Nash et al., 2013; Volk & Koenig, 2019), lower religiosity (particularly among those with more severe PTSD; Koenig et al., 2018c), greater combat exposure or aftermath violence (Currier et al., 2018; Wisco et al., 2017), multiple deployments (Wisco et al., 2017), greater physical disability or chronic pain (Koenig et al., 2018a), alcohol and drug abuse (Nieuwsma et al., 2021), and service branch (Army; Wisco et al., 2017). As noted above, depression and anxiety are strongly correlated with MI in almost all of these studies.

Healthcare Settings

There are also several personal, behavioral, and situational factors that characterize the presence of MI in healthcare professionals. These include younger age (Mantri et al., 2021b; Wang et al., 2021), female gender (Wang et al., 2021), the unmarried (Wang et al., 2021), the divorced (Mantri et al., 2021b), those with lower religiosity (Mantri et al., 2021a, 2021b), Buddhist or Taoist religion (vs. no religion) (Wang et al., 2021), involvement in the care of COVID-19 patients (Mantri et al., 2021b; Wang et al., 2021), nurses (vs. physicians) (Mantri et al., 2021b), higher levels of burnout or emotional exhaustion (Mantri et al., 2021a, 2021b; Wang et al., 2020, 2021), and exposure to workplace violence (Wang et al., 2020, 2021). As in studies of military personnel, depression and anxiety symptoms have been significantly correlated with MI in each of the studies above (except when controlling for HCP burnout).

Other Settings

Little is known about the predictors and correlates of MI experienced in settings other than war/combat and healthcare, including among religious persons with high moral standards that they may frequently find themselves transgressing (or observe close friends or family members transgressing). This is due at least in part to the lack of psychometrically valid measures to assess MI symptoms in civilian settings. This is clearly an area were further research is needed in order to fill this research gap.

Personality, Prior Trauma, and Culture

There is little doubt that personality, temperament (based on genetic influences), and developmental experiences play important roles in predisposing individuals to MI, although little if any research has been done to document this. For example, the emotionally and morally sensitive individual is probably more likely to experience MI than the individual with an antisocial personality disorder or with psychopathy. For example, the psychopath whose moral compass is altered, may feel no remorse after harmful actions toward others that would cause extreme guilt or shame in most individuals. Likewise, prior life trauma—particularly adverse childhood experiences—almost certainly play a role in the development and maintenance of MI, as such experiences alter the stress response system (Battaglia et al., 2019). Cultural factors also play a role (e.g., the propensity to experience shame in Asian countries), although these are likewise understudied and poorly understood.

Treatments for Moral Injury

Both secular and spiritual/religious interventions have been described for the treatment of MI (Table 2). Some of these interventions have been examined for efficacy in randomized controlled trials (RCTs), are currently being examined in RCTs, or there are plans in place to do so. Other interventions have had their efficacy described in qualitative or case studies.

Table 2.

Examples of treatment types for moral injury

| Secular | Spiritual/religious | Pastoral care |

|---|---|---|

| Adaptive disclosure therapy (ADT) (Litz et al., 2017) | Building spiritual strength (BSS) (Harris et al., 2011, 2018) | Healing through forgiveness (Grimsley & Grimsley, 2017) |

| Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) (e.g., Hayes et al., 2011; Kopacz et al., 2016; Nieuwsma et al., 2015; Evans et al., 2020) | Spiritually integrated cognitive processing therapy (SICPT) (Koenig et al., 2017; Pearce et al., 2018) | Structured pastoral care (SPC) (Ames et al., 2018b) |

| Cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) (e.g., Maguen & Burkman, 2013; Maguen et al., 2017; Purcell et al., 2018) | Religiously integrated cognitive behavior therapy (RCBT) (Koenig et al., 2015)a | Pastoral narrative disclosure (PND) (Carey & Hodgson, 2018) |

| Cognitive processing therapy (CPT) (Hoge & Chard, 2018) | Moral injury reconciliation therapy (MIR) (Lee, 2018) | |

| Prolonged exposure (PE) (e.g., Held et al., 2018; Paul et al., 2014) | Moral injury group (MIG) (Cenkner et al., 2021) | |

| Alternate therapies (e.g., eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) Shapiro & Laliotis, 2015; Hurley, 2018) |

aRCBT specifically focuses on depression

Secular Treatments

These include adaptive disclosure therapy, acceptance and commitment therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, cognitive processing therapy, prolonged exposure, and healing through forgiveness. Although largely secular in approach, some of these may have spiritual components. Many were originally developed for the treatment of PTSD.

Adaptive Disclosure Therapy (ADT) is a manualized therapy designed to help Veterans and active duty military to integrate and resolve moral injuries experienced during wartime using emotion-focused cognitive behavioral strategies (Litz et al., 2017). This method involves discussing and processing of wartime memories and experiences, while at the same time challenging dysfunctional cognitions related memories of the trauma and moral transgressions. The treatment consists of six 90-min one-on-one treatment sessions.

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) is a largely secular approach to MI that focuses on improving adaptation and quality of life in those suffering from moral transgressions. There is a strong emphasis in ACT on mindfulness, a core principle in Buddhism, which is the seventh step in the eightfold path. Thus, this treatment could be described as a secular technique with a spiritual component. ACT can be administered in one-on-one individual sessions or in a group therapy format. There is no set number of therapy sessions; rather, this is dependent on the needs of the individual. The basis for this approach is the notion that psychological rigidity is the primary cause for many emotional problems, including MI. ACT is thought to reduce MI symptoms by increasing flexibility and adaptive behaviors as they apply to moral concerns. There are six core therapeutic processes involved in ACT: clarification, committed action, acceptance, defusion, present moment, and self-as-context. The goal is to help the individual live an increasingly mindful and value-based life (see Hayes et al., 2011, for an in-depth description of each process). Nieuwsma et al., (2015) and Kopacz et al., (2016) have emphasized the usefulness of ACT in helping individuals to accept difficult emotional experiences and to lead a mindful life committed to action in light of one’s values.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) Cognitive behavioral strategies are frequently utilized in therapies for treating MI and the PTSD that often accompanies it. ADT (and ACT to some extent) is based on CBT principles. Another CBT approach to MI is based on “mode” theory, a model that organizes and conceptualizes risk and protective factors for MI (Rozek & Bryan, 2021). Mode theory emphasizes predispositions, activating events, and acute modes that influence the development and maintenance of MI, utilizing a cognitive behavioral framework to understand MI, its causes, and treatment. Impact of killing (IOK) in war is another one-on-one cognitive behavioral approach to relieving the guilt and shame that current and former military personnel experience from killing others or from feeling responsible for the deaths of others during war (Maguen & Burkman, 2013; Maguen et al., 2017; Purcell et al., 2018). The goals of IOK are to help individuals forgive themselves and make amends for their actions. Cognitive restructuring is used to identify and challenge dysfunctional beliefs caused by feeling responsible for the death of others. Acceptance and grief work are other components of this therapy. While primarily a secular form of therapy, IOK includes a spiritual component as well, in that it addresses the spiritual concerns about killing and seeks to resolve these by reconnecting to a spiritual community and making amends in that setting.

Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT) CPT evolved out of cognitive behavioral therapy in order to address the particular psychological conflicts involved in PTSD. CPT is one of the two most widely used therapies for PTSD in military settings, together with prolonged exposure (PE) (VA/DoD, 2017; Hoge & Chard, 2018). CPT involves a combination of PE and CBT that focuses on processing negative thoughts related to the trauma or moral transgression by identifying and challenging those thoughts in order to achieve more adaptive thinking and accompanying behavior (Resick et al., 2017). CPT seeks to identify “stuck points” that prevent individuals from moving beyond obsessing about moral transgressions/traumatic memories by emotionally processing those stuck points. In the latest version of CPT, attention is paid to addressing the symptoms of MI including guilt over transgressions, difficulty forgiving self and others, condemning self, and resolving religious struggles (Resick et al., 2017, pp 285–287.

Prolonged Exposure (PE) PE has also been used to treat MI (Paul et al., 2014). Initially developed as a treatment for PTSD, PE involves repeatedly exposing the person to their traumatic memories through imagining the trauma or to real-life situations similar to the trauma (in vivo exposure). Repeated exposure of this type is conducted until habituation develops and the event no longer elicits distress. This can also be done for morally compromising situations that cause symptoms of MI. PE for MI typically consists of nine 45-min weekly one-on-one sessions that focus on this imaginal or in vivo exposure. To our knowledge, only a few case reports have been published to support the efficacy of PE for MI, although the effectiveness of this approach makes sense (Held et al., 2018; Paul et al., 2014).

Healing through Forgiveness (HTF) HTF is a 12-session 12-week program that largely utilizes CBT and PE strategies to not only focus upon the Veterans but actively includes family members (mostly the spouse) throughout most sessions (Grimsley & Grimsley, 2017). While largely secular in nature, HTF has a spiritual component. The sessions include (1) introduction and overview including pre-test MIQ-M assessment (veteran only), (2) remembering how to remember, (3) the conscious/unconscious PTSD and MI, (4) dealing with guilt, (5) dealing with shame, (6) MI and the subconscious, (7) forgiveness and fear as trigger for anger and PTSD, (8) integration of spouses and significant others, (9) the family and PTSD, (10) lessons for living life together, (11) summarizing PTSD and traumatization exercises, and (12) spiritual disciplines of forgiveness. There is a six-month follow-up and post-session questionnaire. HTF does not exclusively focus upon MI but co-jointly considers PTSD as well.

Other Therapies Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) has also been used with at least some level of success in Veterans struggling with the combination of MI and PTSD symptoms, (Hurley, 2018; Shapiro & Laliotis, 2015).

Spiritual/Religious Treatments

Since all major religious traditions have dealt with issues related to MI for centuries, if not millennia (where transgressions of moral values have been called “sin” or “missing the mark”), it should not be surprising that spiritual/religious approaches to MI have been proposed (Koenig et al., 2019b, pp. 82–109). Indeed, the moral values that have been transgressed in MI are frequently based on the religious beliefs of the individual or the cultural environment in which those individuals were raised. Some of these approaches have been tested for efficacy in RCTs, whereas others are in the midst of such clinical trials. These include building spiritual strengths (Harris et al., 2011, 2018), and spiritually integrated cognitive processing therapy (SICPT) (Koenig et al., 2017; Pearce et al., 2018; Wade, 2016).

Building Spiritual Strengths (BSS) The efficacy of BSS has now been demonstrated in two RCTs (Harris et al., 2011, 2018). This is a manual-based group therapy that is intended to be delivered in faith community settings. BSS was designed to relieve the MI/spiritual distress associated with PTSD. The intervention is administered by either a mental health provider (counselor, psychologist, or social worker) with training in spiritually integrated care, or by a chaplain/clergyperson with mental health training or clinical pastoral education (CPE). The BSS manual may be obtained by contacting J. Irene Harris, Ph.D. (jeanette.harris2@va.gov).

Spiritually integrated CPT (SICPT) SICPT, which is typically administered by a licensed professional counselor or psychologist, is a spiritually/religiously integrated treatment for MI in the setting of PTSD. This is a manualized, structured, one-on-one intervention that is delivered in twelve 50-min sessions once or twice per week over 6–12 weeks (Koenig et al., 2017; Pearce et al., 2017, 2018). Based on a cognitive processing therapy (CPT) framework, SICPT uses the patient’s spiritual/religious beliefs to process traumatic events and dysfunctional cognitions. SICPT is now being tested in an RCT being conducted at the Greater Los Angeles VA Health System, where it is being compared to standard CPT and a structured pastoral care intervention (see below) in a 3-arm trial (Ames et al., 2018a). SICPT is also now being examined for efficacy in a single-group experimental study at Duke University Health System, with initial results that are quite promising (O’Garo & Koenig, 2018). The therapist manual, materials manual, and religion-specific appendices (Christian, Jewish, Muslim, Buddhist, and Hindu) are available on request (Michelle.Pearce@umaryland.edu or Harold.Koenig@duke.edu).

Religiously Integrated Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (RCBT) Although RCBT does not specifically address MI or PTSD, it does focus on depression, which is often comorbid with MI. This treatment addresses the dysfunctional cognitions, maladaptive assumptions, and negative behaviors that often drive depression. RCBT has been tested in a randomized controlled trial against conventional CBT (CCBT), and found to be similarly effective, with both treatments producing a large effect size (Cohen’s d = − 3.02 for RCBT; d = − 2.39 for CCBT) (Koenig et al., 2015; Pearce et al., 2015). Similar to SICPT, RCBT is available in Jewish, Christian, Muslim, Hindu, and Buddhist versions, and both therapist manuals and patient workbooks are available for download without cost at Duke University’s Center for Spirituality, Theology and Health website (CSTH, 2021).

Pastoral Care Interventions

Clergy with mental health training and chaplains are ideally positioned to address concerns about moral transgressions and help individuals to resolve symptoms of MI. Chaplains serve many roles including counseling, providing support, education, and performing sacraments and rituals, all of which may be relevant in the treatment of MI and in the rehabilitation of individuals with it (Carey et al., 2016). Several treatment approaches/therapies have been developed specifically for use by religious professionals.

Pastoral Narrative Disclosure (PND) Carey and Hodgson (2018) argue that the sacrament of penance has long been utilized within religious traditions to acknowledge the moral pain that military personnel experience after returning from combat, thereby allowing for absolution, forgiveness, and cleansing. Because of their role and authority with regard to carrying out the sacrament of penance, clergy/chaplains play a unique role in bringing about the healing of MI through this sacrament. Bearing this in mind, Carey and Hodgson (2018) have developed a one-on-one intervention called pastoral narrative disclosure (PND). PND was designed for use by mental health-trained clergy, CPE trained health care chaplains and/or military trained chaplains and is based on the liturgical confessional model for the moral treatment of warriors returning from battle (Verkamp, 2006). Each word in the title of this intervention represents a key component of the treatment: “pastoral” signifies the embracing of the individual holistically; “narrative” emphasizes the individual’s story as a unique experience; and “disclosure” reflects the modern terminology for confession (which might also involve the atonement for sins committed, whether real or perceived). Atonement appears to be absolutely essential for complete healing in those experiencing MI from having hurt others by transgressing moral boundaries. The eight steps of PND, which is characterized as a spiritual counseling, guidance and educational intervention, are rapport, reflection, review, reconstruction, restoration, ritual, renewal, and reconnection (see Carey & Hodgson, 2018, for a detailed description of each step). PND is not a stand-alone treatment, but rather is viewed as part of a multi-disciplinary approach to MI rehabilitation. PND is a pastoral modification of adaptive disclosure and the sacrament of penance, but which has neutralized the confessional terminology by using secular locutions, “enabling it to be more suitable for those of all faiths and none.”

Moral Injury Reconciliation Therapy (MIRT) Similar to Carey and Hodgson’s PND model, MIRT consists of five sessions: (1) recognition/awareness of moral injury/trauma, (2) reply/lament and confession, (3) response through one’s own meaning making system, (4) remedy/forgiveness, grief facilitation, identity and humanity considerations, and (5) reconciliation involving the development of spiritual discipline/habit training (Lee, 2018). While it is not as in-depth as PND (which considers acts of restoration and community reconnection), MIRT also takes into account PTSD and sexual trauma.

Moral Injury Group (MIG) MIG is a 12-week 90-min group intervention that utilizes a psychologist and a chaplain to address the psychological, moral, and spiritual distress associated with MI as a result of transgressions occurring during military service (Cenkner et al., 2021). The weekly group sessions provide information about MI; explore related topics such as moral emotions, moral values, moral dilemmas in moral disengagement (including spiritual struggles) and provide an opportunity for participants to explore spiritual disciplines and reflect on the religious/spiritual dimensions of their military experiences. The objective is to normalize moral pain from combat and to help participants recognize that the onus of warfare does not lie entirely with the Veteran but also with the community, those whom the Veteran has been defending. The intervention ends a community healing ceremony held at a VA chapel that is attended by family, friends, and members of the public. In a small pilot trial (n = 32), this treatment was shown to result in small to medium reductions in psychological symptoms and spiritual struggles (Cenkner et al., 2021). There is at least one other structured group intervention for MI that involves the teaming up of a chaplain and a psychologist developed at the San Antonio VA (Pernicano & Haynes, 2021).

Structured Pastoral Care (SPC) SPC is a structured, manualized chaplain intervention designed for the treatment of MI among Veterans with significant PTSD symptoms (Ames et al., 2018b). This one-on-one treatment is administered in twelve 50-min sessions delivered once or twice per week over 6–12 weeks. SPC is a religion-specific intervention with Christian, Jewish, Muslim, Buddhist, and Hindu versions now available. The intervention relies on the original scriptures in each of these five major religious traditions to address each of the ten major symptoms of MI (guilt, shame, moral concerns, feelings of betrayal, lack of trust, lack of meaning, difficulty forgiving, self-condemnation, religious struggles, and loss of religious faith). Beginning with the MI symptom that is least distressing to the individual, the chaplain addresses each of symptom using the following eight treatment modules: conviction, lamentation, repentance, confession, forgiveness, reconciliation, atonement, recovery and resiliency (with an additional anger module if needed). A small pilot study involving two case reports has found that SPC delivered by chaplains is effective not only in reducing MI symptoms but also improving PTSD symptoms as well (Ames et al., 2021).

Future Directions

Most of the research on MI has taken place in the USA or other Western countries. To our knowledge, no studies of MI have been conducted among those in military or non-military settings in the Middle East; North, Central, South, or Far East Asia; or Central or South America. This represents a huge research gap, as almost nothing is known about the prevalence or correlates of MI among current or former members of the military in these countries, or among healthcare professionals (other than in China) or first responders, or among civilians experiencing trauma from exposure to assault, robbery, accidents, or rape. Even in Western countries, there has been little systematic research on MI in non-military or non-healthcare settings.

Furthermore, almost all studies done thus far have been cross-sectional in nature, making it difficult to determine individual characteristics that may affect the development or course of MI. As a result, prospective studies are needed that follow individuals prior to the development of MI and for extended periods afterward to determine factors related to the development and time course of MI symptoms, with or without treatment. In terms of establishing causality, for both practical and ethical reasons, it is unlikely that RCTs will be able to randomize individuals to either morally injurious events or to a control group. This consideration further underscores the importance of well-designed prospective studies that will be able to contribute to causal inference.

In terms of treatment, more research is needed that systematically examines efficacy of spiritually integrated psychological interventions and pastoral care interventions in RCTs, comparing these to standard secular treatments for MI. There are also a number of community-church programs, e.g., Rita Brock’s ecclesiastical work on MI in the USA, but also local church and community-based programs of this type in other countries as well, such as the Warrior Welcome Home program at Christ Church Cathedral, Darwin, in Australia (West, 2017). Future research efforts should test the efficacy of such programs, comparing them to other spiritual/religious, pastoral care, and secular treatments.

Finally, given the psychological comorbidity that is often present in those with MI (e.g., depression, anxiety, substance use disorders), research is needed to determine whether pharmacological treatments may be helpful in relieving MI symptoms and/or associated comorbidity. Likewise, research is needed on the efficacy of combining medications with psychological, spiritual, or pastoral care interventions for MI.

Conclusions

MI is a recently acknowledged syndrome within psychology, but in reality, is a very old syndrome that has existed as long as humans have had moral and ethical beliefs and values that can be transgressed. These moral concerns following war or other forms of severe trauma have historically been addressed and treated by various rituals and other religious/spiritual approaches, often administered by clergy. We review here the challenges in terms of establishing a consensus on definition, the measurement, prevalence, correlates, and consequences of MI. We have focused here on the research conducted among current or former members of the military and in healthcare professionals facing moral dilemmas during the COVID-19 pandemic. We have also noted that MI occurs in first responders and others exposed to severe trauma that may have involved actions that transgressed moral beliefs or values, although regrettably, little research has been done in this regard. We also explored secular, spiritually integrated psychological, and pastoral care interventions for the treatment of MI, and discussed directions for future research needed to fill many gaps in knowledge about this syndrome. We conclude that MI is a common and potentially devastating emotional/behavioral condition that often develops in those experiencing severe trauma, one that is often ignored by clinicians. This article provides an update on what is known about MI and what needs to be known to expand our understanding of this common syndrome that causes lifelong suffering for many, as well as disconnects individuals from themselves, loved ones, and even from their God.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

None. The authors have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®) American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ames, D., Erickson, Z., Geise, C., Tiwari, S., Sakhno, S., Sones, A., & Koenig, H. G. (2018a). Spiritually-integrated cognitive processing therapy (SICPT) for the treatment of moral injury in U.S. Veterans with PTSD: 3-arm randomized controlled trial. Los Angeles, CA: Greater Los Angeles VA Health System, IRB approval # PCC 2018–050499 (VA Project #0059).

- Ames D, Erickson Z, Geise C, Tiwari S, Sakhno S, Sones A, Tyrrell CG, Mackay CRB, Steele CW, Van Hoof T, Koenig HG. Treatment of moral injury in U.S. Veterans with PTSD utilizing a structured chaplain intervention. Journal of Religion and Health. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s10943-021-01312-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ames D, Erickson Z, Youssef NA, Arnold I, Adamson CS, Sones AC, Yin J, Haynes K, Volk F, Teng EJ, Oliver JP. Moral injury, religiosity, and suicide risk in US veterans and active duty military with PTSD symptoms. Military Medicine. 2019;184(3–4):e271–e278. doi: 10.1093/milmed/usy148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ames, D., Haynes, K., Adamson, S.F., Bruce, L.E., Chacko, B.K., Button, L., & Koenig, H. G. (2018b). A structured chaplain intervention for Veterans with moral injury in the setting of PTSD. Durham, NC: Duke University Center for Spirituality, Theology and Health (Christian, Buddhist, Hindu, Jewish, and Muslim versions available; contact Harold.Koenig@duke.edu)

- Barnes HA, Hurley RA, Taber KH. Moral injury and PTSD: Often co-occurring yet mechanistically different. Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 2019;31(2):A4–103. doi: 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.19020036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battaglia AM, Protopopescu A, Boyd JE, Lloyd C, Jetly R, O'Connor C, Hood HK, Nazarov A, Rhind SG, Lanius RA, McKinnon MC. The relation between adverse childhood experiences and moral injury in the Canadian Armed Forces. European Journal of Psychotraumatology. 2019 doi: 10.1080/20008198.2018.1546084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein CZ, Manata P. Moral responsibility and the wrongness of abortion. Journal of Medicine and Philosophy. 2019;44(2):243–262. doi: 10.1093/jmp/jhy039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brock RN, Lettini G. Soul repair: Recovering from moral injury after war. Beacon Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bryan AO, Bryan CJ, Morrow CE, Etienne N, Ray-Sannerud B. Moral injury, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts in a military sample. Traumatology. 2014;20(3):154. doi: 10.1037/h0099852. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan AO, Theriault JL, Bryan CJ. Self-forgiveness, posttraumatic stress, and suicide attempts among military personnel and veterans. Traumatology. 2015;21(1):40. doi: 10.1037/trm0000017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan CJ, Bryan AO, Anestis MD, Anestis JC, Green BA, Etienne N, Morrow CE, Ray-Sannerud B. Measuring moral injury: Psychometric properties of the moral injury events scale in two military samples. Assessment. 2016;23(5):557–570. doi: 10.1177/1073191115590855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan CJ, Morrow CE, Etienne N, Ray-Sannerud B. Guilt, shame, and suicidal ideation in a military outpatient clinical sample. Depression and Anxiety. 2013;30(1):55–60. doi: 10.1002/da.22002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey LB, Hodgson TJ. Chaplaincy, spiritual care and moral injury: Considerations regarding screening and treatment. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2018;9:619. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey LB, Hodgson TJ, Krikheli L, Soh RY, Armour AR, Singh TK, Impiombato CG. Moral injury, spiritual care and the role of chaplains: An exploratory scoping review of literature and resources. Journal of Religion and Health. 2016;55(4):1218–1245. doi: 10.1007/s10943-016-0231-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cenkner DP, Yeomans PD, Antal CJ, Scott JC. A pilot study of a moral injury group intervention co-facilitated by a chaplain and psychologist. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2021;34(2):367–374. doi: 10.1002/jts.22642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CSTH. (2021). Religiously-integrated CBT manuals and workbooks for depression. Durham, NC: Duke University Center for Spirituality, Theology, and Health. Retrieved June 7, 2021, from https://spiritualityandhealth.duke.edu/index.php/religious-cbt-study/therapy-manuals

- Curlin, F. A. (2005). After harm: Medical error and the ethics of forgiveness. British Medical Journal, 331(7528), 1343. 10.1136/bmj.331.7528.1343

- Currier JM, Farnsworth JK, Drescher KD, McDermott RC, Sims BM, Albright DL. Development and evaluation of the Expressions of Moral Injury Scale—Military Version. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy. 2018;25(3):474–488. doi: 10.1002/cpp.2407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currier JM, Holland JM, Drescher K, Foy D. Initial psychometric evaluation of the Moral Injury Questionnaire—Military version. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy. 2015;22(1):54–63. doi: 10.1002/cpp.1866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currier JM, Holland JM, Rojas-Flores L, Herrera S, Foy D. Morally injurious experiences and meaning in Salvadorian teachers exposed to violence. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2015;7(1):24. doi: 10.1037/a0034092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currier JM, Isaak SL, McDermott RC. Validation of the expressions of moral injury scale-military version-short form. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy. 2020;27(1):61–68. doi: 10.1002/cpp.2407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currier JM, Smith PN, Kuhlman S. Assessing the unique role of religious coping in suicidal behavior among US Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. 2017;9(1):118. doi: 10.1037/rel0000055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drescher KD, Foy DW, Kelly C, Leshner A, Schutz K, Litz B. An exploration of the viability and usefulness of the construct of moral injury in war veterans. Traumatology. 2011;17(1):8–13. doi: 10.1177/1534765610395615. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Euripides (416 BCE; translated by Thomas Sleigh). Euripides’ Herakles. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Evans WR, Stanley MA, Barrera TL, Exline JJ, Pargament KI, Teng EJ. Morally injurious events and psychological distress among veterans: Examining the mediating role of religious and spiritual struggles. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2018;10(3):360. doi: 10.1037/tra0000347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans WR, Walser RD, Drescher KD, Farnsworth JK. The moral injury workbook: Acceptance and commitment therapy skills for moving beyond shame, anger, and trauma to reclaim your values. New Harbinger Publications; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Feinstein A, Pavisian B, Storm H. Journalists covering the refugee and migration crisis are affected by moral injury not PTSD. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine Open. 2018;9(3):1–7. doi: 10.1177/2054270418759010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrajão PC, Aragão Oliveira R. Portuguese war veterans: Moral injury and factors related to recovery from PTSD. Qualitative Health Research. 2016;26(2):204–214. doi: 10.1177/1049732315573012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankfurt S, Frazier P. A review of research on moral injury in combat veterans. Military Psychology. 2016;28(5):318–330. doi: 10.1037/mil0000132. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greene T, Bloomfield MA, Billings J. Psychological trauma and moral injury in religious leaders during COVID-19. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2020;12(S1):S143–S145. doi: 10.1037/tra0000641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimsley CW, Grimsley G. PTSD & moral injury: The journey to healing through forgiveness. Exulon Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Haight W, Korang-Okrah R, Black JE, Gibson P, Nashandi NJ. Moral injury among Akan women: Lessons for culturally sensitive child welfare interventions. Children and Youth Services Review. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.104768. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haight W, Sugrue E, Calhoun M, Black J. A scoping study of moral injury: Identifying directions for social work research. Children and Youth Services Review. 2016;70:190–200. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.09.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harris JI, Erbes CR, Engdahl BE, Thuras P, Murray-Swank N, Grace D, Ogden H, Olson RH, Winskowski AM, Bacon R, Malec C. The effectiveness of a trauma focused spiritually integrated intervention for veterans exposed to trauma. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2011;67(4):425–438. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris JI, Usset T, Voecks C, Thuras P, Currier J, Erbes C. Spiritually integrated care for PTSD: A randomized controlled trial of “Building Spiritual Strength”. Psychiatry Research. 2018;267:420–428. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.06.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K. D., & Wilson, K. G. (2011). Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: The Process and Practice of Mindful Change. NY, NY: Guilford Press

- Held P, Klassen BJ, Brennan MB, Zalta AK. Using prolonged exposure and cognitive processing therapy to treat veterans with moral injury-based PTSD: Two case examples. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2018;25(3):377–390. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2017.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgson TJ, Carey LB. Moral injury and definitional clarity: Betrayal, spirituality and the role of chaplains. Journal of Religion and Health. 2017;56(4):1212–1228. doi: 10.1007/s10943-017-0407-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgson, T. J., Carey, L. B., & Koenig, H. G. (2021). Moral injury, Australian veterans and the role of chaplains: An exploratory qualitative study. (forthcoming). [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hoffman J, Nickerson A. The impact of moral-based appraisals on psychological outcomes in response to analogue trauma: An experimental paradigm of moral injury. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2021;45:494–507. doi: 10.1007/s10608-020-10172-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoge CW, Chard KM. A window into the evolution of trauma focused psychotherapies for posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2018;319(4):343–345. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.21880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley EC. Effective treatment of veterans with PTSD: Comparison between intensive daily and weekly EMDR approaches. Frontiers in Psychology. 2018;9:1458. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jinkerson, J. D. (2016). Defining and assessing moral injury: A syndrome perspective. Traumatology, 22(2), 122–130. 10.1037/trm0000069

- Joannou M, Besemann M, Kriellaars D. Project trauma support: Addressing moral injury in first responders. Mental Health in Family Medicine. 2017;13:418–422. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig H, Ames D, Pearce M. Religion and recovery from PTSD. Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG, Ames D, Youssef NA, Oliver JP, Volk F, Teng EJ, Haynes K, Erickson ZD, Arnold I, O’Garo K, Pearce M. The moral injury symptom scale-military version. Journal of Religion and Health. 2018;57(1):249–265. doi: 10.1007/s10943-017-0531-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG, Ames D, Youssef NA, Oliver JP, Volk F, Teng EJ, Haynes K, Erickson ZD, Arnold I, O’Garo K, Pearce M. Screening for moral injury: the moral injury symptom scale–military version short form. Military Medicine. 2018;183(11–12):e659–e665. doi: 10.1093/milmed/usy017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG, Boucher NA, Oliver RJP, Youssef N, Mooney SR, Currier JM, Pearce M. Rationale for spiritually oriented cognitive processing therapy for moral injury in active duty military and veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2017;205(2):147–153. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG, Pearce MJ, Nelson B, Shaw SF, Robins CJ, Daher NS, Cohen HJ, Berk LS, Bellinger DL, Pargament KI, King MB. Religious vs. conventional cognitive behavioral therapy for major depression in persons with chronic medical illness: A pilot randomized trial. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2015;203(4):243–251. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG, Youssef NA, Ames D, Oliver JP, Teng EJ, Haynes K, Erickson ZD, Arnold I, Currier JM, O'Garo K, Pearce M. Moral injury and religiosity in US veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2018;206(5):325–331. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG, Youssef NA, Ames D, Teng EJ, Hill TD. Examining the overlap between moral injury and PTSD in US veterans and active duty military. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2020;208(1):7–12. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000001077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG, Youssef NA, Pearce M. Assessment of moral injury in veterans and active duty military personnel with PTSD: A review. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2019;10:443. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopacz MS, Ames D, Koenig HG. It's time to talk about physician burnout and moral injury. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6(11):e28. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30385-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopacz MS, Connery AL, Bishop TM, Bryan CJ, Drescher KD, Currier JM, Pigeon WR. Moral injury: A new challenge for complementary and alternative medicine. Complementary Therapies in Medicine. 2016;24:29–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2015.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee LJ. Moral injury reconciliation. A practitioner's guide for treating moral injury, PTSD, grief and military sexual trauma through spiritual formation. Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lentz LM, Smith-MacDonald L, Malloy D, Carleton RN, Brémault-Phillips S. Compromised conscience: A scoping review of moral injury among firefighters, paramedics, and police officers. Frontiers in Psychology. 2021;12:681. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.639781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi-Belz Y, Greene T, Zerach G. Associations between moral injury, PTSD clusters, and depression among Israeli veterans: A network approach. European Journal of Psychotraumatology. 2020;11(1):1–13. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2020.1736411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litz BT, Lebowitz L, Gray MJ, Nash WP. Adaptive disclosure: A new treatment for military trauma, loss, and moral injury. Guilford Publications; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Litz BT, Stein N, Delaney E, Lebowitz L, Nash WP, Silva C, Maguen S. Moral injury and moral repair in war veterans: A preliminary model and intervention strategy. Clinical Psychology Review. 2009;29(8):695–706. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd CS, Nicholson AA, Densmore M, Théberge J, Neufeld RW, Jetly R, McKinnon MC, Lanius RA. Shame on the brain: Neural correlates of moral injury event recall in posttraumatic stress disorder. Depression and Anxiety. 2021;38:596–605. doi: 10.1002/da.23128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguen S, Burkman K. Combat-related killing: Expanding evidence-based treatments for PTSD. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2013;20(4):476–479. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2013.05.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maguen S, Burkman K, Madden E, Dinh J, Bosch J, Keyser J, Schmitz M, Neylan TC. Impact of killing in war: A randomized, controlled pilot trial. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2017;73(9):997–1012. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantri S, Lawson JM, Wang Z, Koenig HG. Identifying moral injury in healthcare professionals: The Moral Injury Symptom Scale-HP. Journal of Religion and Health. 2020;59(5):2323–2340. doi: 10.1007/s10943-020-01065-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantri S, Lawson JM, Wang Z, Koenig HG. Prevalence and predictors of moral injury symptoms in health care professionals. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2021;209(3):174–180. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000001277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantri S, Song YK, Lawson JM, Berger EJ, Koenig HG. Moral injury and burnout in health care professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2021 doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000001367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller SC. Moral injury and relational harm: Analyzing rape in Darfur. Journal of Social Philosophy. 2009;40(4):504–523. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9833.2009.01468.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murray E. Moral injury and paramedic practice. Journal of Paramedic Practice. 2019;11(10):424–425. doi: 10.12968/jpar.2019.11.10.424. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nash WP, Marino Carper TL, Mills MA, Au T, Goldsmith A, Litz BT. Psychometric evaluation of the moral injury events scale. Military Medicine. 2013;178(6):646–652. doi: 10.7205/MILMED-D-13-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nash WP, Vasterling J, Ewing-Cobbs L, Horn S, Gaskin T, Golden J, Riley WT, Bowles SV, Favret J, Lester P, Koffman R. Consensus recommendations for common data elements for operational stress research and surveillance: Report of a federal interagency working group. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2010;91(11):1673–1683. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickerson A, Schnyder U, Bryant RA, Schick M, Mueller J, Morina N. Moral injury in traumatized refugees. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics. 2015;84(2):122–123. doi: 10.1159/000369353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwsma JA, Brancu M, Wortmann J, Smigelsky MA, King HA, VISN 6 MIRECC Workgroup. Meador KG. Screening for moral injury and comparatively evaluating moral injury measures in relation to mental illness symptomatology and diagnosis. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy. 2021;28(1):239–250. doi: 10.1002/cpp.2503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwsma J, Walser RD, Farnsworth JK, Drescher KD, Meador KG, Nash W. Possibilities within acceptance and commitment therapy for approaching moral injury. Current Psychiatry Reviews. 2015;11(3):193–206. doi: 10.2174/1573400511666150629105234. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Garo, K. G., & Koenig, H. G. (2018). A pilot study of Spiritually Integrated Cognitive Processing Therapy (SICPT) in the treatment of moral injury in clients with PTSD. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Center for Spirituality Theology and Health (IRB # Pro00084666).

- Papazoglou K, Blumberg DM, Chiongbian VB, Tuttle BM, Kamkar K, Chopko B, Milliard B, Aukhojee P, Koskelainen M. The role of moral injury in PTSD among law enforcement officers: A brief report. Frontiers in Psychology. 2020;11:310. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papazoglou K, Chopko B. The role of moral suffering (moral distress and moral injury) in police compassion fatigue and PTSD: An unexplored topic. Frontiers in Psychology. 2017;8:1999. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul LA, Gros DF, Strachan M, Worsham G, Foa EB, Acierno R. Prolonged exposure for guilt and shame in a veteran of Operation Iraqi Freedom. American Journal of Psychotherapy. 2014;68(3):277–286. doi: 10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.2014.68.3.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce MJ, Haynes KN, Currier JM, O’Garo KG, Koenig HG. Spiritually-integrated cognitive processing therapy veteran/military version: Therapist’s manual (with religion-specific appendices) Duke University Center for Spirituality, Theology and Health; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce MJ, Haynes K, Rivera NR, Koenig HG. Spiritually-integrated cognitive processing therapy: A new treatment for PTSD and moral injury. Global Advances in Health and Medicine. 2018;7:1–7. doi: 10.1177/2164956118759939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce MJ, Koenig HG, Robins CJ, Nelson B, Shaw SF, Cohen HJ, King MB. Religiously integrated cognitive behavioral therapy: A new method of treatment for major depression in patients with chronic medical illness. Psychotherapy. 2015;52(1):56–66. doi: 10.1037/a0036448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pernicano, P., & Haynes, K. (2021). Moral injury psychoeducation group facilitator guide: Introduction to acceptance and forgiveness. San Antonio, TX: San Antonio VA MIRECC (contact chaplain Kerry Haynes [Kerry.Haynes@va.gov] for more information).

- Purcell N, Burkman K, Keyser J, Fucella P, Maguen S. Healing from moral injury: A qualitative evaluation of the impact of killing treatment for combat veterans. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma. 2018;27(6):645–673. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2018.1463582. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Resick, P. A., Monson, C. M., & Chard, K. M. (2017). Religion and morality (pp 285–287). In Cognitive processing therapy for PTSD. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Rozek DC, Bryan CJ. A cognitive behavioral model of moral injury. In: Currier JM, Drescher KD, Nieuwsma J, editors. Addressing moral injury in clinical practice. American Psychological Association; 2021. pp. 19–33. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro F, Laliotis D. EMDR therapy for trauma-related disorders. In: Schnyder U, Cloitre M, editors. Evidence based treatments for trauma-related psychological disorders. Springer; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Shay J. Achilles in Vietnam: Combat trauma and the undoing of character. Scribner; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Shay J. Moral injury. Psychoanalytic Psychology. 2014;31(2):182–191. doi: 10.1037/a0036090. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stovall M, Hansen L, van Ryn M. A critical review: Moral injury in nurses in the aftermath of a patient safety incident. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2020;52(3):320–328. doi: 10.1111/jnu.12551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugrue EP. Moral injury among professionals in K–12 education. American Educational Research Journal. 2020;57(1):43–68. doi: 10.3102/0002831219848690. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun D, Phillips RD, Mulready HL, Zablonski ST, Turner JA, Turner MD, McClymond K, Nieuwsma JA, Morey RA. Resting-state brain fluctuation and functional connectivity dissociate moral injury from posttraumatic stress disorder. Depression and Anxiety. 2019;36(5):442–452. doi: 10.1002/da.22883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talbot SG, Dean W. Physicians aren’t ‘burning out.’ They’re suffering from moral injury. Stat. 2018;7(26):18. [Google Scholar]

- VA/DoD. (2017). VA/DoD clinical practice guidelines for the management of posttraumatic stress disorder and acute stress disorder, version 3.0. Retrieved July 6, 2021, from https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/ptsd/VADoDPTSDCPGFinal.pdf.

- Verkamp B. The moral treatment of returning warriors in early medieval and modern times. University of Scranton Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Volk F, Koenig HG. Moral injury and religiosity in active duty US Military with PTSD symptoms. Military Behavioral Health. 2019;7(1):64–72. doi: 10.1080/21635781.2018.1436102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wade NR. Integrating cognitive processing therapy and spirituality for the treatment of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in the military. Social Work & Christianity. 2016;43(3):59–72. [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Harold KG, Tong Y, Wen J, Sui M, Liu H, Zaben FA, Liu G. Moral injury in Chinese health professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2021 doi: 10.1037/tra0001026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang ZZ, Koenig HG, Tong Y, Wen J, Sui M, Liu H, Liu G. Psychometric properties of the Moral Injury Symptoms Scale among Chinese health professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20:556. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-02954-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West, C. (2017). Warrior Welcome Home. Retrieved June 7, 2021, from http://christchurchcathedral.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/WWH-NTParticipant-Invitation.docx

- Williamson V, Greenberg N, Murphy D. Predictors of moral injury in UK treatment seeking veterans. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisco BE, Marx BP, May CL, Martini B, Krystal JH, Southwick SM, Pietrzak RH. Moral injury in US combat veterans: Results from the national health and resilience in veterans study. Depression and Anxiety. 2017;34(4):340–347. doi: 10.1002/da.22614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]