Abstract

Chronic liver disease (CLD) and cirrhosis accounts for approximately 2 million deaths annually worldwide. CLD and cirrhosis-related mortality has increased steadily in the United States.1,2 With the global pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), patients with CLD and cirrhosis represent a vulnerable population at higher risk for complications and mortality.3,4 Although high mortality from COVID-19 among patients with CLD and cirrhosis have been reported,5 national trends in mortality related to CLD and cirrhosis before and during the COVID-19 pandemic have not been assessed. This study estimated the temporal quarterly trends in CLD and cirrhosis-related mortality in the United States from 2017 Q1 to 2020 Q3 using provisional data releases from the National Vital Statistics System.6,7

Chronic liver disease (CLD) and cirrhosis accounts for approximately 2 million deaths annually worldwide. CLD and cirrhosis-related mortality has increased steadily in the United States.1 , 2 With the global pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), patients with CLD and cirrhosis represent a vulnerable population at higher risk for complications and mortality.3 , 4 Although high mortality from COVID-19 among patients with CLD and cirrhosis have been reported,5 national trends in mortality related to CLD and cirrhosis before and during the COVID-19 pandemic have not been assessed. This study estimated the temporal quarterly trends in CLD and cirrhosis-related mortality in the United States from 2017 Q1 to 2020 Q3 using provisional data releases from the National Vital Statistics System.6 , 7

Methods

The methods used for this study have been described in detail elsewhere.1 , 2 The National Vital Statistics System recently released quarterly provisional estimates to provide high-quality, near real-time US mortality data during the COVID-19 pandemic.7 CLD and cirrhosis were identified and provided through quarterly provision mortality data using the underlying cause-of-death codes of K70 and K73-K74 in the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision.6

Provisional mortality data provided 2 mortality definitions.6 First, the quarterly (3-month period) mortality annualized to present deaths per year that would be expected if the quarter-specific rate prevailed for 12 months.6 Second, the mortality for “12 months ending with quarter” (also called moving average rate) are the average rates for the 12 months that end with the quarter.6 Estimates for the 12-month period ending with a specific quarter include all seasons of the year and, thus, are insensitive to seasonality.6 Age-adjusted mortality was computed according to the age distribution of 2000 US standard population by the direct method. We examined changes in temporal trends over time using the National Cancer Institute’s joinpoint regression program version 4.9.0.0. This joinpoint regression determines whether single or multiple trend segments explain age-adjusted quarterly mortality over time by fitting joined straight lines to trend data.8 For each trend segment, we reported the quarterly percentage change (QPC) and the average QPC, a summary measure of trend accounting for transitions within each trend segment.8 Joinpoint regression analyzed a set of the time points at which the change in the trend of the mortality is statistically significant and calculates the quarter-to-quarter percentage change in quarterly age-adjusted mortality and the 95% confidence interval (CI).8

Results

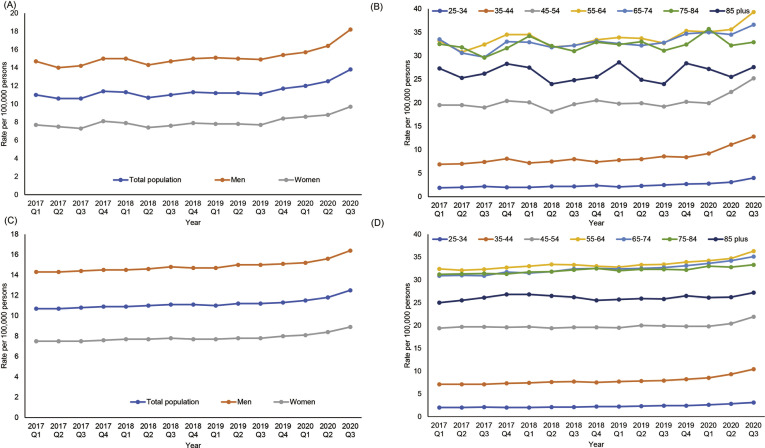

As indicated in Table 1 and Supplementary Figure 1 A, age-adjusted quarterly (3-month period) mortality caused by CLD and cirrhosis steadily increased from 11.0 per 100,000 persons in 2017 Q1 to 13.8 per 100,000 persons in 2020 Q3 with a statistically significant average QPC increase of 1.6% (95% CI, 0.8%–2.5%). However, the increase in mortality was markedly higher during the COVID-19 pandemic (6.1%; 95% CI, 2.1%–10.3%) compared with the early period (0.5%; 95% CI, -0.1% to 1.0%). When we analyzed mortality by sex, mortality in men was higher than in women. Increasing trends in mortality during the COVID-19 pandemic were consistently noted regardless of men (QPC, 8.4%; 95% CI, 1.2%–16.1%) and women (QPC, 5.1%; 95% CI, 1.8%–8.5%). Although mortality in the older (≥55 years) population was higher than in the younger (<55 years) population, only the younger population showed increasing trends in mortality during the COVID-19 pandemic (Table 1, Supplementary Figure 1 B). The mortality for the most recent quarter (2020 Q3) was significantly higher than from the same quarter of the previous year (2019 Q3) in the total population and across sex and age groups (Table 1, Supplementary Table 1; P < .05). When we defined mortality as the mortality for “12 months ending with quarter” (Supplementary Table 1, Supplementary Figure 1 C and D), a sharp increase was observed during COVID-19 pandemics with a QPC of 4.6% (95% CI, 3.0%–6.3%) with a narrow CI compared with quarterly (3-month period) mortality. The results remained essentially identical stratified by sex. Consistent with previous analyses using quarterly (3-month period) mortality, mortality increased with statistically significant average QPCs ranged from 0.4 to 1.8 before the COVID-19 pandemic and then increased rapidly during the COVID-19 pandemic across the age group 25–74 with narrower CI compared with quarterly mortality.

Table 1.

Age-Adjusted Chronic Liver Disease and Cirrhosis-Related Mortality and QPC Between 2017 Quarter 1 and 2020 Quarter 3 Using the Quarterly (3-Month Period) Mortality

| Age-adjusted mortality (per 100,000 persons) |

Average QPC (95% CI) |

Trend segment 1 |

Trend segment 2 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 Q1 | 2019 Q3 | 2020 Q3 | 2017 1Q to 2020 3Q | Year | QPC (95% CI) | Year | QPC (95% CI) | |

| Total population | 11.0 | 11.1 | 13.8a | 1.6 (0.8 to 2.5)b | 2017 Q1 to 2019 Q4 | 0.5 (-0.1 to 1.0) | 2019 Q4 to 2020 Q3 | 6.1 (2.1 to 10.3)b |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Men | 14.7 | 14.9 | 18.2a | 1.7 (0.7 to 2.6)b | 2017 Q1 to 2020 Q1 | 0.6 (0.2 to 1.0)b | 2020 Q1 to 2020 Q3 | 8.4 (1.2 to 16.1)b |

| Women | 7.7 | 7.7 | 9.7a | 1.6 (0.7 to 2.6)b | 2017 Q1 to 2019 Q3 | 0.3 (-0.5 to 1.1) | 2019 Q3 to 2020 Q3 | 5.1 (1.8 to 8.5)b |

| Age | ||||||||

| 25 to 34 | 1.9 | 2.5 | 4.0a | 4.7 (2.9 to 6.5)b | 2017 Q1 to 2019 Q3 | 1.9 (0.4 to 3.4)b | 2019 Q3 to 2020 Q3 | 11.9 (5.5 to 18.8)b |

| 35 to 44 | 6.9 | 8.6 | 12.8a | 4.3 (2.8 to 5.8)b | 2017 Q1 to 2019 Q4 | 1.5 (0.6 to 2.5)b | 2019 Q4 to 2020 Q3 | 15.2 (7.4 to 23.4)b |

| 45 to 54 | 19.5 | 19.2 | 25.2a | 1.9 (0.3 to 3.4)b | 2017 Q1 to 2020 Q1 | 0.2 (-0.5 to 0.9) | 2020 Q1 to 2020 Q3 | 12.5 (0.5 to 25.8)b |

| 55 to 64 | 33.2 | 32.7 | 39.3a | 0.9 (0.4 to 1.5)b | 2017 Q1 to 2020 Q3 | 0.9 (0.4 to 1.5)b | ||

| 65 to 74 | 33.5 | 32.8 | 36.6a | 0.9 (0.4 to 1.3)b | 2017 Q1 to 2020 Q3 | 0.9 (0.4 to 1.3)b | ||

| 75 to 84 | 32.5 | 31.1 | 32.9a | 0.4 (-0.2 to 0.9) | 2017 Q1 to 2020 Q3 | 0.4 (-0.2 to 0.9) | ||

| ≥85 | 27.3 | 24.0 | 27.6a | 0.0 (-0.8 to 0.9) | 2017 Q1 to 2020 Q3 | 0.0 (-0.8 to 0.9) | ||

NOTE. The quarterly (3-month period) mortality annualized to present deaths per year would be expected if the quarter-specific rate prevailed for 12 months.

CI, confidence interval; Q, quarter; QPC, quarterly percentage change.

P < .05 comparison between estimates for the most recent quarter (2020 Q3) versus the same quarter of the previous year (2019 Q3).

P < .05.

Supplementary Figure 1.

Quarterly age-adjusted mortality for chronic liver disease and cirrhosis in the United States between 2017 Quarter 1 and 2020 Quarter 3. (A) Total population and stratified by sex using the quarterly (3-month period) mortality. (B) Stratified by age using the quarterly (3-month period) mortality. (C) Total population and stratified by sex using mortality for 12 months ending with quarter. (D) Stratified by age using mortality for 12 months ending with quarter.

Discussion

This nationally representative population-based study found an increase in CLD and cirrhosis-related mortality from 2017 Q1 through 2020 Q3. However, there was a significant increase in national CLD and cirrhosis-related mortality during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. We found increasing trends in mortality during the COVID-19 pandemic across the sex and younger population. Acute-on-chronic liver failure or acute decompensation could occur in compensated cirrhosis with concomitant COVID-19, which strongly correlated with the risk of liver-related death.5 Also, it may be challenging to provide timely care to patients with CLD and cirrhosis during the COVID-19 pandemic.5 Provisional mortality data only provided 15 leading underlying causes of death. COVID-19 was the third leading underlying cause of death in 2020.6 Because we used the definition of “CLD and cirrhosis”-related underlying cause of death, we think this analysis was limited to only liver-related mortality, not COVID-19-related mortality as the underlying cause of death. Stable trends in liver-related mortality in the older population may be explained by deaths caused by COVID-19 as the underlying cause and “CLD and cirrhosis” as contributing causes of death. We were unable to access contributing causes of death because provisional mortality data did not provide this information. The strength of our study includes an up-to-date description of the national mortality trends caused by CLD and cirrhosis before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Our study has several limitations. First, provisional estimates are provided for 15 leading causes of death and COVID-19 as the underlying cause of death. Therefore, we were unable to assess etiology and other liver diseases, such as hepatocellular carcinoma, as underlying causes of death. Also, we were unable to examine COVID-19-related death among patients with CLD and cirrhosis. Second, data are provisional, and numbers of death and mortality may change as additional information is received.6

In conclusion, although CLD and cirrhosis-related mortality continue to increase during the recent 4-year period, mortality increased markedly during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States.

Acknowledgments

The National Vital Statistics System Quarterly Provisional Estimate for mortality dataset are publicly available at the National Center for Health Statistics of the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr.htm).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest The authors disclose no conflicts.

Note: To access the supplementary material accompanying this article, visit the online version of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology at www.cghjournal.org, and at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2021.07.009.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table 1.

Age-Adjusted Chronic Liver Disease and Cirrhosis-Related Mortality and QPC Between 2017 Q1 and 2020 Q3 Using Mortality for 12 Months Ending With Quarter

| Age-adjusted mortality (per 100,000 persons) |

Average QPC (95% CI) |

Trend segment 1 |

Trend segment 2 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 Q1 | 2019 Q3 | 2020 Q3 | 2017 Q1 to 2020 Q3 | Year | QPC (95% CI) | Year | QPC (95% CI) | |

| Total population | 10.7 | 11.2 | 12.5a | 1.1 (0.9 to 1.3)b | 2017 Q1 to 2020 Q1 | 0.5 (0.4 to 0.6)b | 2020 Q1 to 2020 Q3 | 4.6 (3.0 to 6.3)b |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Men | 14.3 | 15.0 | 16.4a | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.2)b | 2017 Q1 to 2020 Q1 | 0.5 (0.4 to 0.6)b | 2020 Q1 to 2020 Q3 | 3.9 (2.3 to 5.4)b |

| Women | 7.5 | 7.8 | 8.9a | 1.3 (0.9 to 1.6)b | 2017 Q1 to 2020 Q1 | 0.6 (0.4 to 0.7)b | 2020 Q1 to 2020 Q3 | 5.5 (2.8 to 8.3)b |

| Age | ||||||||

| 25 to 34 | 2.0 | 2.4 | 3.1a | 3.4 (2.4 to 4.3)b | 2017 Q1 to 2019 Q4 | 1.8 (1.2 to 2.4)b | 2019 Q4 to 2020 Q3 | 9.3 (4.7 to 14.2)b |

| 35 to 44 | 7.1 | 7.9 | 10.4a | 2.7 (2.3 to 3.1)b | 2017 Q1 to 2019 Q4 | 1.2 (0.9 to 1.4)b | 2019 Q4 to 2020 Q3 | 8.5 (6.5 to 10.6)b |

| 45 to 54 | 19.4 | 19.9 | 21.9a | 0.8 (0.4 to 1.1)b | 2017 Q1 to 2020 Q1 | 0.1 (-0.0 to 0.3) | 2020 Q1 to 2020 Q3 | 4.8 (2.1 to 7.6)b |

| 55 to 64 | 32.4 | 33.4 | 36.3a | 0.8 (0.4 to 1.2)b | 2017 Q1 to 2020 Q1 | 0.4 (0.2 to 0.6)b | 2020 Q1 to 2020 Q3 | 3.3 (0.5 to 6.3)b |

| 65 to 74 | 30.9 | 32.7 | 35.1a | 0.9 (0.7 to 1.1)b | 2017 Q1 to 2019 Q4 | 0.6 (0.5 to 0.8)b | 2019 Q4 to 2020 Q3 | 1.9 (0.8 to 3.0)b |

| 75 to 84 | 31.2 | 32.3 | 33.3 | 0.4 (0.3 to 0.5)b | 2017 Q1 to 2020 Q3 | 0.4 (0.3 to 0.5)b | ||

| 85- | 25.0 | 26.5 | 27.2 | 0.2 (-0.1 to 0.5) | 2017 Q2 to 2020 Q3 | 0.2 (-0.1 to 0.5) | ||

NOTE. The mortality for “12 months ending with quarter” (also called moving average rate) is the average rates for the 12 months that end with the quarter. Estimates for the 12-month period ending with a specific quarter include all seasons of the year and, thus, are insensitive to seasonality.

CI, confidence interval; Q, quarter; QPC, quarterly percentage change.

P < .05 comparison between estimates for the most recent quarter (2020 Q3) versus the same quarter of the previous year (2019 Q3).

P < .05.

References

- 1.Kim D., et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;159:1558–1560. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim D., et al. Gastroenterology. 2019;157:1055–1066. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim D., et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19:1469–1479.e19. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.09.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh S., et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;159:768–771. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.04.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mohammed A., et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2021;55:187–194. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ahmad FB, et al. Quarterly provisional estimates for selected indicators of mortality, 2018-Quarter 4, 2020. National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Vital Statistics Rapid Release Program. 2021.

- 7.Ahmad F.B., et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:519–522. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7014e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim H.J., et al. Stat Med. 2000;19:335–351. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(20000215)19:3<335::aid-sim336>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]